Abstract

Problem/Condition

Since the first U.S. infant conceived with assisted reproductive technology (ART) was born in 1981, both the use of ART and the number of fertility clinics providing ART services have increased steadily in the United States. ART includes fertility treatments in which eggs or embryos are handled in the laboratory (i.e., in vitro fertilization [IVF] and related procedures). Although the majority of infants conceived through ART are singletons, women who undergo ART procedures are more likely than women who conceive naturally to deliver multiple-birth infants. Multiple births pose substantial risks for both mothers and infants, including obstetric complications, preterm delivery (<37 weeks), and low birthweight (<2,500 g). This report provides state-specific information for the United States (including the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) on ART procedures performed in 2016 and compares birth outcomes that occurred in 2016 (resulting from ART procedures performed in 2015 and 2016) with outcomes for all infants born in the United States in 2016.

Period Covered

2016.

Description of System

In 1995, CDC began collecting data on ART procedures performed in fertility clinics in the United States as mandated by the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act of 1992 (FCSRCA) (Public Law 102–493 [October 24, 1992]). Data are collected through the National ART Surveillance System (NASS), a web-based data collection system developed by CDC. This report includes data from 52 reporting areas (the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico).

Results

In 2016, a total of 197,706 ART procedures (range: 162 in Wyoming to 24,030 in California) with the intent to transfer at least one embryo were performed in 463 U.S. fertility clinics and reported to CDC. These procedures resulted in 65,964 live-birth deliveries (range: 57 in Puerto Rico to 8,638 in California) and 76,892 infants born (range: 74 in Alaska to 9,885 in California). Nationally, the number of ART procedures performed per 1 million women of reproductive age (15–44 years), a proxy measure of the ART use rate, was 3,075. ART use rates exceeded the national rate in 14 reporting areas (Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Utah, and Virginia). ART use exceeded 1.5 times the national rate in nine states, including three (Illinois, Massachusetts, and New Jersey) that also had comprehensive mandated health insurance coverage for ART procedures (i.e., coverage for at least four oocyte retrievals).

Nationally, among ART transfer procedures for patients using fresh embryos from their own eggs, the average number of embryos transferred increased with increasing age (1.5 among women aged <35 years, 1.7 among women aged 35–37 years, and 2.2 among women aged >37 years). Among women aged <35 years, the national elective single-embryo transfer (eSET) rate was 42.7% (range: 8.3% in North Dakota to 83.9% in Delaware).

In 2016, ART contributed to 1.8% of all infants born in the United States (range: 0.3% in Puerto Rico to 4.7% in Massachusetts). ART also contributed to 16.4% of all multiple-birth infants, including 16.2% of all twin infants and 19.4% of all triplets and higher-order infants. ART-conceived twins accounted for approximately 96.5% (21,455 of 22,233) of all ART-conceived infants born in multiple deliveries. The percentage of multiple-birth infants was higher among infants conceived with ART (31.5%) than among all infants born in the total birth population (3.4%). Approximately 30.4% of ART-conceived infants were twins and 1.1% were triplets and higher-order infants.

Nationally, infants conceived with ART contributed to 5.0% of all low birthweight (<2,500 g) infants. Among ART-conceived infants, 23.6% had low birthweight compared with 8.2% among all infants. ART-conceived infants contributed to 5.3% of all preterm (gestational age <37 weeks) infants. The percentage of preterm births was higher among infants conceived with ART (29.9%) than among all infants born in the total birth population (9.9%).

The percentage of ART-conceived infants who had low birthweight was 8.7% among singletons, 54.9% among twins, and 94.9% among triplets and higher-order multiples; the corresponding percentages among all infants born were 6.2% among singletons, 55.4% among twins, and 94.6% among triplets and higher-order multiples. The percentage of ART-conceived infants who were born preterm was 13.7% among singletons, 64.2% among twins, and 97.0% among triplets and higher-order infants; the corresponding percentages among all infants were 7.8% for singletons, 59.9% for twins, and 97.7% for triplets and higher-order infants.

Interpretation

Multiple births from ART contributed to a substantial proportion of all twins, triplets, and higher-order infants born in the United States. For women aged <35 years, who typically are considered good candidates for eSET, on average, 1.5 embryos were transferred per ART procedure, resulting in higher multiple birth rates than could be achieved with single-embryo transfers. Of the four states (Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island) with comprehensive mandated health insurance coverage, three (Illinois, Massachusetts, and New Jersey) had rates of ART use >1.5 times the national average. Although other factors might influence ART use, insurance coverage for infertility treatments accounts for some of the difference in per capita ART use observed among states because most states do not mandate any coverage for ART treatment.

Public Health Action

Twins account for almost all of ART-conceived multiple births born in multiple deliveries. Reducing the number of embryos transferred and increasing use of eSET, when clinically appropriate, could help reduce multiple births and related adverse health consequences for both mothers and infants. Because multiple-birth infants are at increased risk for numerous adverse sequelae that cannot be ascertained from the data collected through NASS alone, long-term follow-up of ART infants through integration of existing maternal and infant health surveillance systems and registries with data available from NASS might be useful for monitoring adverse outcomes.

Introduction

Since the birth of the first U.S. infant conceived with assisted reproductive technology (ART) in 1981, use of advanced technologies to overcome infertility has increased, as has the number of fertility clinics providing ART services and procedures in the United States (1). In 1992, Congress passed the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act (FCSRCA) (Public Law 102–493 [October 24, 1992]), which requires that all U.S. fertility clinics performing ART procedures report data to CDC annually on every ART procedure performed. CDC initiated data collection in 1995 and in 1997 published the first annual ART Fertility Clinic Success Rates Report (2). Two reports are produced annually (ART Fertility Clinic Success Rates Report and ART National Summary Report) (1,3). These reports present multiple measures of success for ART, including the percentage of ART procedures and transfers that result in pregnancies, live-birth deliveries, singleton live-birth deliveries, and multiple live-birth deliveries.

Although ART helps millions of persons achieve pregnancy, ART is associated with potential health risks for both mothers and infants. Because multiple embryos are transferred in most ART procedures, ART often results in multiple-gestation pregnancies and multiple births (4–11). Risks to the mother from a multiple-birth pregnancy include higher rates of caesarean delivery, maternal hemorrhage, pregnancy-related hypertension, and gestational diabetes (12,13). Risks to the infant include preterm birth, low birthweight, death, and greater risk for birth defects and developmental disability (4–16). Further, singleton infants conceived with ART might have higher risk for low birthweight and prematurity than singletons not conceived with ART (17). However, recent research suggests that this higher risk might be associated with multiple embryo transfers resulting in singleton births because the higher risk was observed among patients administered ART who were not good candidates for elective single-embryo transfer (eSET) and had multiple embryos transferred (18).

This report was compiled from data about ART procedures performed in 2016 and reported to CDC’s Division of Reproductive Health. Data on the use of ART are presented for residents of each U.S. state, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. Data also are reported on outcomes for infants born in 2016 resulting from ART procedures performed in 2015 and 2016. The report also examines the contribution of ART to selected outcomes (e.g., multiple-birth infants, low birthweight infants, preterm infants, and small for gestational age infants) and compares outcomes among ART-conceived infants with outcomes among all infants born in the United States in 2016.

Methods

National ART Surveillance System

In 1995, CDC initiated data collection of ART procedures performed in the United States. ART data are obtained from all fertility clinics in the United States through the National ART Surveillance System (NASS), a web-based data collection system developed by CDC (https://www.cdc.gov/art/nass/index.html). Clinics that are members of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) can report their data to NASS through SART and enter their data directly into NASS. Clinics that are not members of SART can enter their data directly into NASS. All clinics must verify the accuracy of the data they reported in the clinic table in the annual ART Fertility Clinic Success Rates Report before finalizing submission to NASS. The data then are compiled by CDC contractor Westat Inc., a statistical survey research organization, and reviewed for accuracy by both CDC and Westat. In 2016, a small proportion of clinics (8%) did not report their data to CDC and are listed as nonreporting clinics in the 2016 ART Fertility Clinic Success Rates Report, as required by FCSRCA. Because nonreporting clinics tend to be smaller on average than reporting clinics, NASS is estimated to contain information on 97% of all ART procedures in the United States (1).

Data collected include patient demographics, medical history, and infertility diagnoses; clinical information pertaining to the ART procedure type; and information regarding resultant pregnancies and births. The data file contains one record per ART procedure (or cycle of treatment) performed. Because ART providers typically do not provide continued prenatal care after a pregnancy is established, ART clinics collect information on live births for all procedures from patients and physicians.

ART Procedures

ART includes fertility treatments in which eggs or embryos are handled in a laboratory (i.e., in vitro fertilization [IVF], gamete intrafallopian transfer, and zygote intrafallopian transfer). More than 99% of ART procedures performed are IVF. Because an ART procedure consists of multiple steps over an interval of approximately 2 weeks, a procedure often is referred to as a cycle of treatment. An ART cycle usually begins with drug-induced ovarian stimulation. If eggs are produced, the cycle progresses to the egg-retrieval stage, which involves surgical removal of the eggs from the ovaries. After the eggs are retrieved, they are combined with sperm in a laboratory during the IVF procedure. For certain IVF procedures (66.0% in 2016) (1), a specialized technique (intracytoplasmic sperm injection) is used where a single sperm is injected directly into the egg. If successful fertilization occurs, the most viable embryos (i.e., those that appear morphologically most likely to develop and implant) are selected for transfer back into the uterus. If an embryo implants in the uterus, a clinical pregnancy is diagnosed by the presence of a gestational sac detectable by ultrasound. Most pregnancies will progress to a live-birth delivery, defined as the delivery of one or more live-born infants; however, some result in pregnancy loss (19,20). ART does not include treatments in which only sperm are handled (i.e., intrauterine insemination) or procedures in which a woman is administered drugs to stimulate egg production without the intention of having eggs retrieved.

ART procedures are classified on the basis of the source of the egg (patient or donor) and the status of the eggs and embryos. Both fresh and thawed embryos can be derived from fresh or frozen eggs of the patient or donor. Patient and donor embryos can be created using sperm from a partner or donor. ART procedures involving fresh eggs and embryos include an egg-retrieval stage. ART procedures that use thawed eggs or embryos do not include egg retrieval because the eggs were retrieved during a previous ART procedure and either the eggs were frozen or fertilized and the resultant embryos were frozen until the current ART procedure. An ART cycle can be discontinued at any step for medical reasons or by patient choice.

Birth Data for United States

Data on the total number of live-birth and multiple-birth infants in each reporting area in 2016 were obtained from U.S. natality files (21–23). The natality online databases report counts of live births and multiple births occurring within the United States to residents and nonresidents. The data are derived from birth certificates.

Variables and Definitions

Data on ART outcomes and ART procedures are presented by patient’s residence (i.e., reporting area) at the time of treatment, which might not be the same as the location where the procedure was performed. If information on patient’s residence was missing, residence was assigned as the location where the procedure was performed (0.4% of procedures performed in 2016 and 0.2% of live-birth deliveries occurring in 2016). ART procedures performed in the United States among nonresidents who are non-U.S. citizens are included in NASS data (24); however, they are excluded from certain calculations because residency status is unknown. To protect confidentiality, table cells with values of 1–4 for ART-conceived infants and 0–9 for all infants are suppressed. Because of limited numbers, ART data from U.S. territories (with the exception of Puerto Rico) are not included in this report. In addition, estimates derived from cell values <20 in the denominator have been suppressed because they are unstable and estimates could not be calculated when the denominator was zero (e.g., preterm birth among triplets in reporting areas with no triplet births).

This report presents data on all procedures initiated with the intent to transfer at least one embryo, including procedures that used thawed frozen eggs for transfer. Cycles with the intent to freeze all eggs or embryos for future ART cycles were excluded. The number of ART procedures performed per 1 million women of reproductive age (15–44 years) was calculated (25). Data regarding population size were compiled on the basis of July 1, 2016, estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. The resulting rate approximates the proportion of women of reproductive age who used ART in each reporting area. This proxy measure of ART use is only an approximation because certain women who use ART fall outside the age range of 15–44 years (approximately 9% of cycles performed in 2016) and certain women might have had more than one procedure during the reporting period.

A live-birth delivery was defined as a birth of one or more live-born infants. A singleton live-birth delivery was defined as a birth of only one infant who was born live. A multiple live-birth delivery was defined as a birth of two or more infants, at least one of whom was born live. Low birthweight was defined as <2,500 g, moderate low birthweight as 1,500–2,499 g, and very low birthweight as <1,500 g. Gestational age for births among women who did not undergo ART procedures was calculated using obstetric estimate of gestation at delivery (26). For births to women who underwent fresh ART procedures, gestational age was calculated by subtracting the date of egg retrieval from the birth date and adding 14 days. For births to women who underwent frozen embryo cycles or fresh ART procedures for which the date of retrieval was not available, gestational age was calculated by subtracting the date of embryo transfer from the birth date and adding 17 days (to account for an average of 3 days in embryo culture). Preterm delivery was defined as gestational age <37 weeks, late preterm 34–36 weeks, early preterm <34 weeks, and very preterm <32 weeks (20).

Elective single-embryo transfer is a procedure in which one embryo, selected from more than one available embryo, is placed in the uterus with one or more embryos cryopreserved. Fresh transfer procedures in which only one embryo was available for transfer and no embryos were cryopreserved are considered single-embryo transfer but not considered eSET. The rate of eSET was calculated by dividing the total number of eSET procedures by the sum of the total number of eSET procedures plus the total number of transfer procedures in which more than one embryo was transferred. The average number of embryos transferred by age group (<35 years, 35–37 years, and >37 years) was calculated by dividing the total number of embryos transferred by the total number of embryo-transfer procedures performed among that age group. In this report, the percentage of eSET procedures and the average number of embryos transferred were calculated only for patients who used fresh embryos from their own fresh eggs, in which at least one embryo was transferred.

The contribution of ART to all infants born in a particular reporting area was used as a second measure of ART use. The contribution of ART to adverse birth outcomes (e.g., preterm, low birthweight, or small for gestational age [SGA] infants) was calculated by dividing the total number of outcomes among ART-conceived infants by the total number of outcomes among all infants born.

The percentage of infants (ART conceived and all infants) born in a reporting area for each plurality group (singleton, multiple, twin, and triplet and higher-order birth) was calculated by dividing the number of infants (ART conceived and all infants) in each plurality group by the total number of infants born (ART conceived and all infants). The percentage of infants with low birthweight and preterm delivery also was calculated for each plurality group (singleton, twin, and triplet and higher-order births) for both ART-conceived infants and all infants by dividing the number of low birthweight or preterm infants in each plurality group by the total number of infants in that plurality group.

In addition, new in 2016, the proportion of infants who were small for gestational age (i.e., born at <10th percentile of birthweight for gestational age) was calculated using gestational age and birthweight information (27). The percentage of SGA infants was calculated for births that occurred at <37 weeks (preterm), 37–41 weeks (full term), and 22–44 weeks (all births) by dividing the number of SGA infants in each gestational age category by the total number of singleton infants in that gestational age category for ART-conceived and all infants, respectively.

Infants born in a reporting area during any given year include those who were conceived naturally and those who resulted from ART and other infertility treatments. To assess the proportion of ART births among overall U.S. births in 2016, ART births were aggregated from two reporting years: 1) infants conceived with ART procedures performed in 2015 and born in 2016 (59.9% of the live-birth deliveries reported to NASS for 2016) and 2) infants conceived with ART procedures performed in 2016 and born in 2016 (40.1% of the live-birth deliveries reported to NASS for 2016).

Results

Overview of Fertility Clinics

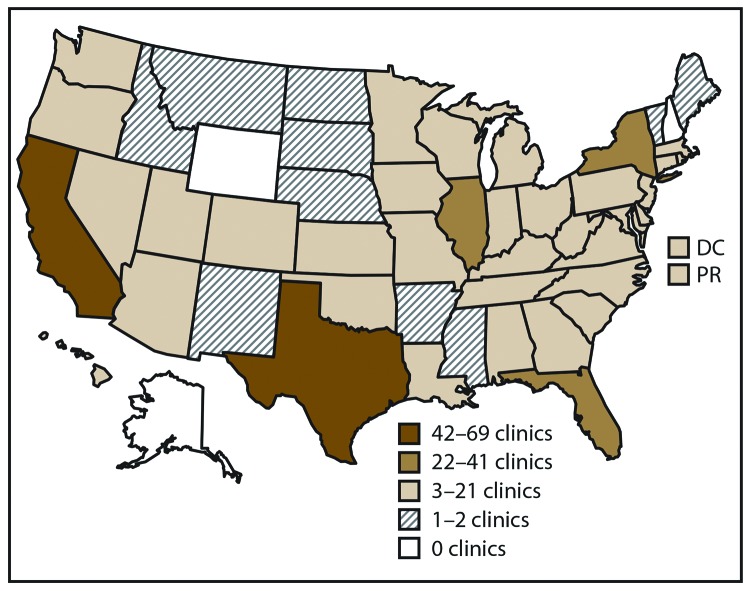

In 2016, a total of 502 fertility clinics in the United States performed ART procedures and 463 (92.2%) provided data to CDC, with the majority located in or near major cities (1) (Figure 1). The number of fertility clinics performing ART procedures varied by reporting area. The reporting areas with the largest numbers of fertility clinics providing data were California (69), Texas (43), and New York (37).

FIGURE 1.

Location and number* of assisted reproductive technology clinics, distributed by quartiles — United States and Puerto Rico, 2016

Abbreviations: DC = District of Columbia; PR = Puerto Rico.

* In 2016, of the 502 clinics in the United States, 463 (92.2%) submitted data.

Number and Type of ART Procedures

The number, type, and outcome of ART procedures performed are provided according to patient’s residence for all 52 reporting areas (Table 1). Residency data were missing for approximately 0.4% of procedures performed and in this case, the patient’s residence was assigned as the location where the ART procedure was performed. In addition, residency data also were missing for 0.2% of live-birth deliveries; however, these ART procedures were included in the totals. In 2016, approximately 16.6% of ART procedures were conducted in reporting areas other than the patient’s state of residence. Non-U.S. residents accounted for approximately 3.0% of ART procedures, 3.5% of ART live-birth deliveries, and 3.6% of ART-conceived infants born.

TABLE 1. Number* and outcomes of assisted reproductive technology procedures with the intent to transfer at least one embryo, by female patient’s reporting area of residence† at time of treatment — United States and Puerto Rico, 2016.

| Patient’s reporting area of residence | No. of ART clinics§ | No. of ART procedures performed | No. of ART embryo-transfer procedures¶ | No. of ART pregnancies | No. of ART live-birth deliveries | No. of ART singleton live-birth deliveries | No. of ART multiple live-birth deliveries | No. of ART live-born infants | ART procedures per 1 million women aged 15–44 yrs** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama |

5 |

1,002 |

756 |

364 |

304 |

241 |

63 |

370 |

1,051.6 |

| Alaska |

0 |

198 |

156 |

77 |

66 |

57 |

9 |

74 |

1,343.5 |

| Arizona |

15 |

3,047 |

2,487 |

1,384 |

1,140 |

859 |

281 |

1,425 |

2,290.3 |

| Arkansas |

1 |

577 |

453 |

233 |

190 |

150 |

40 |

231 |

1,000.4 |

| California |

69 |

24,030 |

18,971 |

10,561 |

8,638 |

7,407 |

1,231 |

9,885 |

2,980.5 |

| Colorado |

8 |

2,346 |

2,044 |

1,331 |

1,123 |

947 |

176 |

1,304 |

2,088.8 |

| Connecticut |

8 |

3,617 |

2,728 |

1,511 |

1,248 |

1,027 |

221 |

1,474 |

5,364.6 |

| Delaware |

2 |

770 |

565 |

299 |

223 |

210 |

13 |

236 |

4,284.5 |

| District of Columbia |

3 |

1,352 |

1,006 |

475 |

382 |

360 |

22 |

405 |

7,371.3 |

| Florida |

27 |

8,714 |

6,580 |

3,300 |

2,695 |

2,180 |

515 |

3,213 |

2,310.6 |

| Georgia |

8 |

4,270 |

3,528 |

1,934 |

1,537 |

1,299 |

238 |

1,780 |

2,005.9 |

| Hawaii |

5 |

1,160 |

807 |

444 |

344 |

260 |

84 |

432 |

4,341.2 |

| Idaho |

1 |

576 |

470 |

280 |

222 |

161 |

61 |

284 |

1,788.3 |

| Illinois†† |

27 |

12,816 |

9,842 |

4,841 |

3,887 |

3,286 |

601 |

4,496 |

5,026.6 |

| Indiana |

9 |

2,282 |

1,779 |

859 |

715 |

568 |

147 |

864 |

1,764.6 |

| Iowa |

2 |

1,362 |

1,104 |

693 |

587 |

509 |

78 |

666 |

2,311.1 |

| Kansas |

4 |

1,056 |

806 |

476 |

386 |

318 |

68 |

454 |

1,890.3 |

| Kentucky |

6 |

1,374 |

1,153 |

570 |

470 |

372 |

98 |

570 |

1,619.4 |

| Louisiana |

6 |

1,724 |

1,150 |

630 |

511 |

390 |

121 |

635 |

1,833.1 |

| Maine |

1 |

491 |

422 |

220 |

177 |

146 |

31 |

208 |

2,122.4 |

| Maryland |

7 |

6,545 |

5,127 |

2,494 |

1,929 |

1,734 |

195 |

2,129 |

5,484.2 |

| Massachusetts†† |

8 |

10,095 |

8,283 |

3,921 |

3,220 |

2,908 |

312 |

3,537 |

7,352.1 |

| Michigan |

13 |

4,213 |

3,349 |

1,773 |

1,439 |

1,066 |

373 |

1,816 |

2,248.2 |

| Minnesota |

5 |

2,919 |

2,506 |

1,445 |

1,190 |

964 |

226 |

1,419 |

2,767.6 |

| Mississippi |

2 |

569 |

457 |

244 |

205 |

169 |

36 |

243 |

955.4 |

| Missouri |

9 |

2,523 |

2,070 |

1,065 |

906 |

701 |

205 |

1,117 |

2,154.0 |

| Montana |

1 |

335 |

262 |

145 |

123 |

94 |

29 |

152 |

1,782.1 |

| Nebraska |

2 |

811 |

620 |

345 |

295 |

235 |

60 |

356 |

2,202.8 |

| Nevada |

5 |

1,321 |

1,084 |

654 |

524 |

420 |

104 |

627 |

2,279.0 |

| New Hampshire |

0 |

819 |

674 |

304 |

253 |

223 |

30 |

285 |

3,400.1 |

| New Jersey†† |

20 |

11,704 |

8,369 |

4,643 |

3,827 |

3,356 |

471 |

4,305 |

6,855.4 |

| New Mexico |

2 |

291 |

274 |

138 |

106 |

84 |

22 |

130 |

738.6 |

| New York |

37 |

23,665 |

17,935 |

8,236 |

6,448 |

5,547 |

901 |

7,367 |

5,914.7 |

| North Carolina |

11 |

4,307 |

3,331 |

1,888 |

1,537 |

1,230 |

307 |

1,849 |

2,150.7 |

| North Dakota |

1 |

310 |

253 |

129 |

110 |

79 |

31 |

142 |

2,104.2 |

| Ohio |

13 |

4,538 |

3,646 |

1,907 |

1,586 |

1,245 |

341 |

1,932 |

2,065.2 |

| Oklahoma |

3 |

984 |

796 |

399 |

338 |

261 |

77 |

416 |

1,280.5 |

| Oregon |

3 |

1,314 |

1,112 |

698 |

593 |

453 |

140 |

738 |

1,645.8 |

| Pennsylvania |

16 |

7,635 |

5,796 |

2,761 |

2,266 |

1,958 |

308 |

2,580 |

3,203.3 |

| Puerto Rico |

3 |

261 |

228 |

103 |

57 |

42 |

15 |

74 |

385.2 |

| Rhode Island†† |

1 |

815 |

697 |

297 |

234 |

194 |

40 |

274 |

3,908.7 |

| South Carolina |

4 |

1,748 |

1,329 |

753 |

594 |

475 |

119 |

715 |

1,825.0 |

| South Dakota |

1 |

288 |

235 |

119 |

106 |

88 |

18 |

125 |

1,821.9 |

| Tennessee |

10 |

1,760 |

1,398 |

766 |

643 |

537 |

106 |

753 |

1,350.8 |

| Texas |

43 |

14,362 |

11,383 |

6,302 |

5,178 |

4,193 |

985 |

6,178 |

2,473.4 |

| Utah |

3 |

2,073 |

1,766 |

1,011 |

829 |

665 |

164 |

997 |

3,128.2 |

| Vermont |

2 |

317 |

241 |

115 |

100 |

82 |

18 |

117 |

2,771.2 |

| Virginia |

9 |

5,668 |

4,488 |

2,269 |

1,807 |

1,601 |

206 |

2,015 |

3,381.5 |

| Washington |

12 |

4,129 |

3,166 |

1,724 |

1,437 |

1,260 |

177 |

1,621 |

2,872.4 |

| West Virginia |

3 |

357 |

307 |

147 |

122 |

101 |

21 |

144 |

1,089.3 |

| Wisconsin |

7 |

2,093 |

1,713 |

904 |

762 |

609 |

153 |

917 |

1,935.1 |

| Wyoming |

0 |

162 |

137 |

80 |

64 |

51 |

13 |

76 |

1,472.9 |

| Nonresident |

— |

6,011 |

4,600 |

2,710 |

2,291 |

1,846 |

445 |

2,740 |

—§§ |

| Total | 463 | 197,706 | 154,439 | 80,971 | 65,964 | 55,218 | 10,746 | 76,892 | 3,075.2 |

Abbreviation: ART = assisted reproductive technology.

* Excludes 65,840 cycles with the intent to freeze all eggs or embryos and 31 procedures performed in territories not included in this report.

† In cases of missing residency data (0.4%), the patient’s residence was assigned as the location where the ART procedure was performed.

§ The ART procedures and outcomes by patient’s reporting area of residence do not necessarily reflect the procedures and outcomes of the ART clinics within the reporting area because some patients seek treatment at a clinic in a location other than their area of residence.

¶ Embryo-transfer procedures include all procedures performed in which an attempt was made to transfer at least one embryo.

** On the basis of U.S. Census Bureau estimates. Source: US Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population for selected age groups by sex for the United States, states, counties, and Puerto Rico Commonwealth and municipios: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau, Population Division; 2016. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=PEP_2016_PEPAGESEX&prodType=table.

†† State with comprehensive insurance mandate requiring insurers to cover the costs associated with diagnosis and treatment of infertility inclusive of ART services for at least four oocyte retrievals.

§§ Non-U.S. residents were excluded from rate because the appropriate denominators were not available.

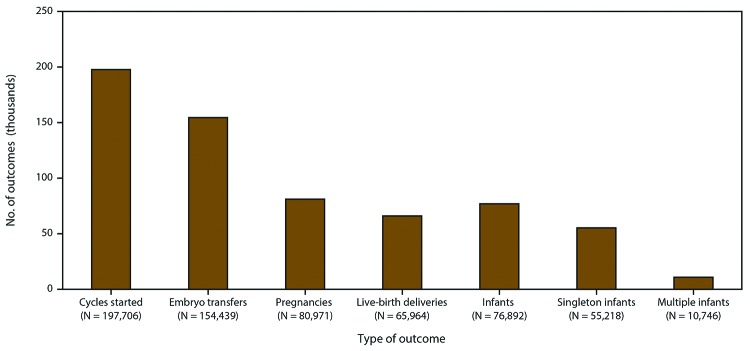

In 2016, a total of 263,577 ART procedures were reported to CDC (1). Included in this report are data for 197,706 ART procedures performed (range: 162 in Wyoming to 24,030 in California) in the United States (including Puerto Rico) with the intent to transfer at least one embryo (Table 1) (Figure 2). Excluded are 65,840 egg or embryo-freezing and embryo-banking procedures that did not result in an embryo transfer as well as 31 procedures that were performed in territories not included in this report. Of 197,706 procedures performed in the reporting areas, 154,439 (78.1%) progressed to embryo transfer. Of 154,439 ART procedures that progressed to the embryo-transfer stage, 80,971 (52.4%) resulted in a pregnancy and 65,964 (42.7%) in a live-birth delivery (range: 57 in Puerto Rico to 8,638 in California). The 65,964 live-birth deliveries included 55,218 singleton live-birth deliveries (83.7%) and 10,746 multiple live-birth deliveries (16.3%) and resulted in 76,892 live-born infants (range: 74 in Alaska to 9,885 in California).

FIGURE 2.

Number of outcomes of assisted reproductive technology procedures* with the intent to transfer at least one embryo, by type of outcome — United States and Puerto Rico, 2016

* A total of 263,577 assisted reproductive technology procedures were reported to CDC.

Six reporting areas with the largest numbers of ART procedures (California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Texas) accounted for approximately half (48.9%; 96,672 of 197,706) of all ART procedures, 48.4% (74,783 of 154,439) of all embryo-transfer procedures, 46.5% (35,768 of 76,892) of all ART-conceived infants born, and 41.9% (4,501 of 10,746) of all ART-conceived multiple live-birth deliveries in the United States (Table 1). However, these six reporting areas accounted for only 36.5% of all U.S. births (24).

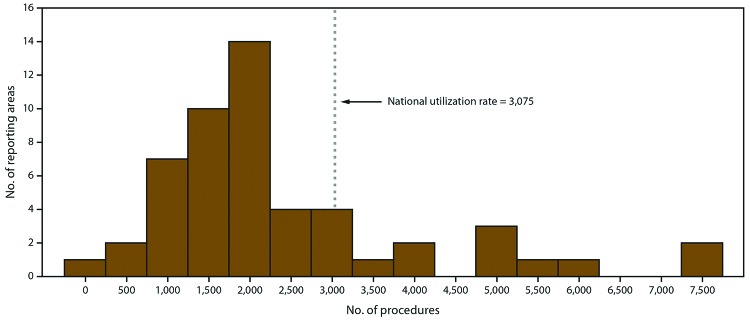

The number of ART procedures per 1 million women of reproductive age (15–44 years) ranged from 385 in Puerto Rico to 7,371 in the District of Columbia, with an overall national rate of 3,075 (Table 1) (Figure 3). Fourteen reporting areas (Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Utah, Virginia, and the District of Columbia) had ART use rates higher than the national rate. Of these reporting areas, the District of Columbia (7,371), Massachusetts (7,352), and New Jersey 6,855) had rates exceeding twice the national rate, whereas Connecticut (5,365), Delaware (4,285), Hawaii (4,341), Illinois (5,027), Maryland (5,484), and New York (5,915) had rates exceeding 1.5 times the national rate. The three reporting areas with the lowest ART use rates were Puerto Rico (385), New Mexico (739), and Mississippi (955).

FIGURE 3.

Number of reporting areas,* by number of assisted reproductive technology procedures performed† with the intent to transfer at least one embryo among women of reproductive age (15–44 years)§ — United States and Puerto Rico, 2016

* Total number of reporting areas: 52.

† Total number of procedures: 197,706.

§ Per 1 million women aged 15–44 years.

Number of Embryos Transferred

The number of embryo-transfer procedures performed, the average number of embryos transferred per procedure, and the percentage of eSET procedures performed among women who used fresh embryos from their own fresh eggs are provided by reporting area and age group (Table 2). Overall, 24,876 embryo-transfer procedures were performed among women aged <35 years, 11,688 among women aged 35–37 years, and 16,131 among women aged >37 years. Nationally, on average, 1.5 embryos were transferred per procedure among women aged <35 years, 1.7 embryos among women aged 35–37 years, and 2.2 embryos among women aged >37 years. The national eSET rate was 42.7% among women aged <35 years (range: 8.3% in North Dakota to 83.9% in Delaware), 25.2% among women aged 35–37 years (range: 2.6% in Puerto Rico to 50.6% in Massachusetts), and 6.7% among women aged >37 years (range: 0% in multiple reporting areas to 31.3% in Delaware).

TABLE 2. Number of assisted reproductive technology embryo-transfer procedures with the intent to transfer at least one embryo* among patients who used fresh embryos from their own fresh eggs, by female patient’s age group and reporting area of residence† at time of treatment — United States and Puerto Rico, 2016.

| Patient’s reporting area of residence | <35 yrs |

35–37 yrs |

>37 yrs |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of embryo-transfer procedures | Average no. of embryos transferred | eSET§ (%) | No. of embryo-transfer procedures | Average no. of embryos transferred | eSET (%) | No. of embryo-transfer procedures | Average no. of embryos transferred | eSET (%) | |

| Alabama |

176 |

1.7 |

26.9 |

48 |

1.8 |

7.7 |

51 |

2.2 |

0.0 |

| Alaska |

30 |

1.6 |

37.0 |

18 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

11 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

| Arizona |

268 |

1.6 |

33.7 |

141 |

1.9 |

15.8 |

133 |

2.4 |

0.9 |

| Arkansas |

126 |

1.7 |

23.4 |

43 |

1.9 |

8.8 |

22 |

2.0 |

5.9 |

| California |

1,923 |

1.5 |

42.8 |

1,246 |

1.7 |

31.1 |

1,949 |

2.3 |

7.9 |

| Colorado |

131 |

1.7 |

27.5 |

61 |

1.8 |

11.5 |

32 |

1.9 |

8.0 |

| Connecticut |

562 |

1.4 |

52.1 |

282 |

1.7 |

26.6 |

370 |

2.1 |

8.6 |

| Delaware |

33 |

1.2 |

83.9 |

19 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

22 |

1.7 |

31.3 |

| District of Columbia |

110 |

1.3 |

65.4 |

81 |

1.4 |

48.2 |

198 |

1.8 |

9.7 |

| Florida |

939 |

1.6 |

37.9 |

463 |

1.8 |

16.5 |

680 |

2.2 |

3.0 |

| Georgia |

567 |

1.5 |

48.1 |

224 |

1.7 |

19.8 |

285 |

2.2 |

6.7 |

| Hawaii |

69 |

1.8 |

20.6 |

37 |

2.2 |

2.9 |

89 |

2.5 |

2.7 |

| Idaho |

104 |

1.6 |

34.4 |

33 |

1.8 |

14.3 |

17 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

| Illinois** |

1,957 |

1.6 |

39.1 |

954 |

1.7 |

22.2 |

1,304 |

2.1 |

4.8 |

| Indiana |

478 |

1.7 |

18.3 |

142 |

1.9 |

7.6 |

172 |

2.2 |

4.3 |

| Iowa |

266 |

1.3 |

62.7 |

80 |

1.5 |

49.3 |

72 |

1.6 |

23.5 |

| Kansas |

120 |

1.5 |

43.4 |

39 |

1.8 |

11.4 |

27 |

2.1 |

4.8 |

| Kentucky |

342 |

1.6 |

35.7 |

138 |

1.9 |

7.0 |

88 |

2.4 |

0.0 |

| Louisiana |

164 |

1.7 |

32.4 |

58 |

1.7 |

11.4 |

41 |

2.2 |

3.1 |

| Maine |

99 |

1.3 |

70.6 |

41 |

1.5 |

41.2 |

64 |

2.1 |

7.4 |

| Maryland |

1,041 |

1.3 |

64.1 |

526 |

1.5 |

43.7 |

782 |

2.0 |

9.4 |

| Massachusetts** |

1,545 |

1.2 |

73.4 |

863 |

1.4 |

50.6 |

1,382 |

2.2 |

10.6 |

| Michigan |

831 |

1.7 |

22.1 |

289 |

1.9 |

6.9 |

349 |

2.1 |

3.7 |

| Minnesota |

628 |

1.5 |

45.6 |

241 |

1.7 |

22.9 |

192 |

2.1 |

8.2 |

| Mississippi |

60 |

1.4 |

52.1 |

29 |

1.9 |

15.4 |

33 |

2.1 |

3.8 |

| Missouri |

426 |

1.7 |

22.2 |

174 |

1.8 |

14.0 |

133 |

2.3 |

1.8 |

| Montana |

44 |

1.4 |

53.7 |

16 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

28 |

2.2 |

0.0 |

| Nebraska |

141 |

1.5 |

35.4 |

30 |

1.9 |

4.0 |

27 |

2.3 |

0.0 |

| Nevada |

149 |

1.7 |

23.1 |

37 |

1.8 |

17.1 |

49 |

1.6 |

21.2 |

| New Hampshire |

164 |

1.3 |

63.3 |

65 |

1.5 |

39.2 |

77 |

2.1 |

4.9 |

| New Jersey** |

1,012 |

1.4 |

50.0 |

550 |

1.7 |

24.3 |

857 |

2.0 |

7.6 |

| New Mexico |

33 |

1.8 |

10.0 |

15 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

12 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

| New York |

2,544 |

1.6 |

40.9 |

1,393 |

1.8 |

23.7 |

2,884 |

2.3 |

5.3 |

| North Carolina |

564 |

1.5 |

46.9 |

258 |

1.8 |

15.2 |

259 |

2.2 |

2.8 |

| North Dakota |

58 |

1.8 |

8.3 |

18 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

22 |

2.0 |

5.3 |

| Ohio |

982 |

1.6 |

34.0 |

349 |

1.8 |

14.0 |

298 |

2.3 |

2.7 |

| Oklahoma |

262 |

1.7 |

21.8 |

79 |

2.0 |

7.1 |

61 |

2.1 |

1.9 |

| Oregon |

148 |

1.7 |

21.1 |

60 |

1.7 |

19.1 |

65 |

1.9 |

4.1 |

| Pennsylvania |

1,111 |

1.5 |

47.8 |

468 |

1.7 |

29.1 |

532 |

2.1 |

8.2 |

| Puerto Rico |

66 |

1.9 |

10.0 |

40 |

2.3 |

2.6 |

64 |

2.2 |

0.0 |

| Rhode Island** |

167 |

1.4 |

60.0 |

85 |

1.7 |

32.9 |

139 |

2.5 |

3.2 |

| South Carolina |

213 |

1.7 |

26.4 |

83 |

2.0 |

6.4 |

77 |

2.1 |

7.4 |

| South Dakota |

74 |

1.8 |

20.6 |

19 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

7 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

| Tennessee |

197 |

1.6 |

36.9 |

75 |

1.8 |

13.6 |

77 |

2.3 |

3.1 |

| Texas |

1,466 |

1.6 |

33.5 |

663 |

1.8 |

14.0 |

781 |

2.0 |

3.1 |

| Utah |

524 |

1.5 |

41.8 |

148 |

1.7 |

23.3 |

90 |

2.0 |

5.3 |

| Vermont |

60 |

1.5 |

34.1 |

37 |

1.8 |

14.3 |

52 |

1.8 |

16.7 |

| Virginia |

732 |

1.3 |

59.4 |

377 |

1.4 |

45.2 |

568 |

1.8 |

13.7 |

| Washington |

453 |

1.5 |

50.6 |

233 |

1.7 |

27.6 |

270 |

1.9 |

7.2 |

| West Virginia |

87 |

1.7 |

24.4 |

31 |

1.9 |

11.5 |

18 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

| Wisconsin |

334 |

1.6 |

38.1 |

111 |

1.7 |

27.4 |

96 |

2.1 |

3.8 |

| Wyoming |

29 |

1.6 |

37.9 |

12 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

7 |

—¶ |

—¶ |

| Nonresident |

267 |

1.6 |

34.3 |

146 |

1.7 |

26.3 |

216 |

2.0 |

11.4 |

| Total | 24,876 | 1.5 | 42.7 | 11,668 | 1.7 | 25.2 | 16,131 | 2.2 | 6.7 |

Abbreviation: eSET = elective single-embryo transfer.

* Includes all procedures in which at least one embryo was transferred.

† In cases of missing residency data (0.4%), the patient’s residence was assigned as the location where the assisted reproductive technology procedure was performed.

§ A procedure in which one embryo, selected from a larger number of available embryos, is placed in the uterus. A cycle in which only one embryo is available is not defined as eSET.

¶ Estimates on the basis of N = <20 in the denominator have been suppressed because such rates are considered unstable.

** State with comprehensive insurance mandate requiring insurers to cover the costs associated with diagnosis and treatment of infertility inclusive of ART services for at least four oocyte retrievals.

Singleton and Multiple-Birth Infants

In 2016, among 3,974,132 infants born in the United States and Puerto Rico (21), 70,600 (1.8%) were conceived with ART procedures performed in 2015 and 2016 (Table 3). California, Texas, and New York had the highest total numbers of all infants born (488,827, 398,047, and 234,283, respectively) and ART-conceived infants born (9,305, 6,113, and 6,981, respectively). The percentage of ART-conceived infants born among all infants born was highest in Massachusetts (4.7%) followed by Connecticut and New Jersey (3.9% each).

TABLE 3. Number, proportion, and percentage of infants born with use of assisted reproductive technology, by female patient’s reporting area of residence* at time of treatment — United States and Puerto Rico, 2016†.

| Patient’s reporting area of residence | Total no. of infants born§,¶ | No. of ART infants born | Proportion of ART infants among all infants (%) | Singleton infants among ART infants |

Singleton infants among all infants¶ |

Proportion of ART singleton infants among all singleton infants (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |||||

| Alabama |

59,151 |

445 |

0.8 |

256 (57.5) |

56,878 (96.2) |

0.5 |

| Alaska |

11,209 |

83 |

0.7 |

46 (55.4) |

10,832 (96.6) |

0.4 |

| Arizona |

84,520 |

1,154 |

1.4 |

697 (60.4) |

81,864 (96.9) |

0.9 |

| Arkansas |

38,274 |

220 |

0.6 |

134 (60.9) |

37,154 (97.1) |

0.4 |

| California |

488,827 |

9,305 |

1.9 |

6,685 (71.8) |

473,330 (96.8) |

1.4 |

| Colorado |

66,613 |

1,229 |

1.8 |

835 (67.9) |

64,499 (96.8) |

1.3 |

| Connecticut |

36,015 |

1,392 |

3.9 |

906 (65.1) |

34,453 (95.7) |

2.6 |

| Delaware |

10,992 |

273 |

2.5 |

235 (86.1) |

10,667 (97.0) |

2.2 |

| District of Columbia |

9,858 |

350 |

3.6 |

293 (83.7) |

9,470 (96.1) |

3.1 |

| Florida |

225,022 |

3,065 |

1.4 |

2,008 (65.5) |

217,688 (96.7) |

0.9 |

| Georgia |

130,042 |

1,569 |

1.2 |

1,153 (73.5) |

125,619 (96.6) |

0.9 |

| Hawaii |

18,059 |

407 |

2.3 |

243 (59.7) |

17,435 (96.5) |

1.4 |

| Idaho |

22,482 |

291 |

1.3 |

172 (59.1) |

21,739 (96.7) |

0.8 |

| Illinois** |

154,445 |

4,454 |

2.9 |

3,048 (68.4) |

148,504 (96.2) |

2.1 |

| Indiana |

83,091 |

862 |

1.0 |

543 (63.0) |

80,234 (96.6) |

0.7 |

| Iowa |

39,403 |

711 |

1.8 |

498 (70.0) |

38,044 (96.6) |

1.3 |

| Kansas |

38,053 |

438 |

1.2 |

307 (70.1) |

36,905 (97.0) |

0.8 |

| Kentucky |

55,449 |

536 |

1.0 |

351 (65.5) |

53,436 (96.4) |

0.7 |

| Louisiana |

63,178 |

538 |

0.9 |

342 (63.6) |

60,929 (96.4) |

0.6 |

| Maine |

12,705 |

194 |

1.5 |

149 (76.8) |

12,306 (96.9) |

1.2 |

| Maryland |

73,136 |

2,036 |

2.8 |

1,605 (78.8) |

70,585 (96.5) |

2.3 |

| Massachusetts** |

71,317 |

3,356 |

4.7 |

2,659 (79.2) |

68,656 (96.3) |

3.9 |

| Michigan |

113,315 |

1,781 |

1.6 |

964 (54.1) |

108,940 (96.1) |

0.9 |

| Minnesota |

69,749 |

1,239 |

1.8 |

776 (62.6) |

67,296 (96.5) |

1.2 |

| Mississippi |

37,928 |

234 |

0.6 |

160 (68.4) |

36,661 (96.7) |

0.4 |

| Missouri |

74,705 |

1,027 |

1.4 |

634 (61.7) |

72,018 (96.4) |

0.9 |

| Montana |

12,282 |

146 |

1.2 |

80 (54.8) |

11,897 (96.9) |

0.7 |

| Nebraska |

26,589 |

319 |

1.2 |

207 (64.9) |

25,643 (96.4) |

0.8 |

| Nevada |

36,260 |

603 |

1.7 |

403 (66.8) |

35,123 (96.9) |

1.1 |

| New Hampshire |

12,267 |

270 |

2.2 |

205 (75.9) |

11,895 (97.0) |

1.7 |

| New Jersey** |

102,647 |

4,002 |

3.9 |

2,961 (74.0) |

98,641 (96.1) |

3.0 |

| New Mexico |

24,692 |

98 |

0.4 |

59 (60.2) |

24,035 (97.3) |

0.2 |

| New York |

234,283 |

6,981 |

3.0 |

4,991 (71.5) |

225,522 (96.3) |

2.2 |

| North Carolina |

120,779 |

1,682 |

1.4 |

1,079 (64.1) |

116,530 (96.5) |

0.9 |

| North Dakota |

11,383 |

140 |

1.2 |

63 (45.0) |

11,004 (96.7) |

0.6 |

| Ohio |

138,085 |

1,962 |

1.4 |

1,167 (59.5) |

132,936 (96.3) |

0.9 |

| Oklahoma |

52,592 |

398 |

0.8 |

230 (57.8) |

50,914 (96.8) |

0.5 |

| Oregon |

45,535 |

644 |

1.4 |

395 (61.3) |

43,986 (96.6) |

0.9 |

| Pennsylvania |

139,409 |

2,373 |

1.7 |

1,747 (73.6) |

134,533 (96.5) |

1.3 |

| Puerto Rico |

28,257 |

81 |

0.3 |

46 (56.8) |

27,687 (98.0) |

0.2 |

| Rhode Island** |

10,798 |

229 |

2.1 |

160 (69.9) |

10,389 (96.2) |

1.5 |

| South Carolina |

57,342 |

729 |

1.3 |

415 (56.9) |

55,202 (96.3) |

0.8 |

| South Dakota |

12,275 |

147 |

1.2 |

73 (49.7) |

11,825 (96.3) |

0.6 |

| Tennessee |

80,807 |

707 |

0.9 |

457 (64.6) |

78,075 (96.6) |

0.6 |

| Texas |

398,047 |

6,113 |

1.5 |

3,938 (64.4) |

385,145 (96.8) |

1.0 |

| Utah |

50,464 |

1,021 |

2.0 |

609 (59.6) |

48,547 (96.2) |

1.3 |

| Vermont |

5,756 |

106 |

1.8 |

72 (67.9) |

5,568 (96.7) |

1.3 |

| Virginia |

102,460 |

2,097 |

2.0 |

1,529 (72.9) |

98,834 (96.5) |

1.5 |

| Washington |

90,505 |

1,511 |

1.7 |

1,115 (73.8) |

87,792 (97.0) |

1.3 |

| West Virginia |

19,079 |

130 |

0.7 |

81 (62.3) |

18,491 (96.9) |

0.4 |

| Wisconsin |

66,615 |

862 |

1.3 |

545 (63.2) |

64,318 (96.6) |

0.8 |

| Wyoming |

7,386 |

60 |

0.8 |

41 (68.3) |

7,162 (97.0) |

0.6 |

| Total | 3,974,132 | 70,600 | 1.8 | 48,367 (68.5) | 3,837,836 (96.6) | 1.3 |

Abbreviation: ART = assisted reproductive technology.

* In cases of missing residency data (0.4%), the patient’s residence was assigned as the location where the ART procedure was performed.

† Includes infants conceived from ART procedures performed in 2015 and born in 2016 and infants conceived from ART procedures performed in 2016 and born in 2016. Total ART births exclude births to nonresidents.

§ U.S. births include births to nonresidents. Source: Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Driscoll AK, Mathews TJ. Births: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2018;67:1–55.

¶ U.S. births include births to nonresidents. Source: CDC Wonder [Internet]. Natality public use data 2007–2016. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2018.

** State with comprehensive insurance mandate requiring insurers to cover the costs associated with diagnosis and treatment of infertility inclusive of ART services for at least four oocyte retrievals.

Nationally, 31.5% of ART-conceived infants were born in multiple-birth deliveries (range: 13.9% in Delaware to 55.0% in North Dakota), compared with 3.4% of all infants (range: 2.0% in Puerto Rico to 4.3% in Connecticut) (Table 4). ART-conceived twins accounted for approximately 96.5% (21,455 of 22,233) of all ART-conceived infants born in multiple deliveries. ART-conceived multiple-birth infants contributed to 16.4% of all multiple-birth infants (range: 5.8% in Mississippi to 31.1% in Connecticut). Approximately 30.4% of all ART-conceived infants were twins compared with 3.3% of all infants. ART-conceived twins contributed to 16.2% of all twins. Of ART-conceived infants, 1.1% were triplets and higher-order multiples compared with 0.1% among all infants. ART-conceived triplets and higher-order infants contributed to 19.4% of all triplets and higher-order infants.

TABLE 4. Number, percentage, and proportion of multiple-birth infants, twins, and triplets and higher-order infants born with use of assisted reproductive technology procedures, by female patient’s reporting area of residence* at time of treatment — United States and Puerto Rico, 2016†.

| Patient’s reporting area of residence | Multiple-birth infants among ART infants§ |

Multiple-birth infants among all infants¶ |

Proportion of ART multiple-birth infants among all multiple-birth infants (%) | Twin infants among ART infants§ |

Twin infants among all infants¶ |

Proportion of ART twin infants among all twin infants (%) | Triplets and higher-order infants among ART infants§ |

Triplets and higher-order infants among all infants¶ |

Proportion of ART triplets and higher-order infants among all triplets and higher-order infants (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | ||||

| Alabama |

189 (42.5) |

2,273 (3.8) |

8.3 |

174 (39.1) |

2,182 (3.7) |

8.0 |

15 (3.4) |

91 (0.2) |

16.5 |

| Alaska |

37 (44.6) |

— (—)** |

—** |

37 (44.6) |

374 (3.3) |

9.9 |

0 (0.0) |

— (—)** |

—** |

| Arizona |

457 (39.6) |

2,656 (3.1) |

17.2 |

429 (37.2) |

2,583 (3.1) |

16.6 |

28 (2.4) |

73 (0.1) |

38.4 |

| Arkansas |

86 (39.1) |

1,120 (2.9) |

7.7 |

86 (39.1) |

1,093 (2.9) |

7.9 |

0 (0.0) |

27 (0.1) |

0.0 |

| California |

2,620 (28.2) |

15,497 (3.2) |

16.9 |

2,535 (27.2) |

15,068 (3.1) |

16.8 |

85 (0.9) |

429 (0.1) |

19.8 |

| Colorado |

394 (32.1) |

2,114 (3.2) |

18.6 |

381 (31.0) |

2,046 (3.1) |

18.6 |

13 (1.1) |

68 (0.1) |

19.1 |

| Connecticut |

486 (34.9) |

1,562 (4.3) |

31.1 |

462 (33.2) |

1,511 (4.2) |

30.6 |

24 (1.7) |

51 (0.1) |

47.1 |

| Delaware |

38 (13.9) |

— (—)** |

—** |

38 (13.9) |

325 (3.0) |

11.7 |

0 (0.0) |

— (—)** |

—**,†† |

| District of Columbia |

57 (16.3) |

— (—)** |

—** |

— (—)** |

388 (3.9) |

—** |

— (—)** |

— (—)** |

—**,†† |

| Florida |

1,057 (34.5) |

7,334 (3.3) |

14.4 |

1,015 (33.1) |

7,162 (3.2) |

14.2 |

42 (1.4) |

172 (0.1) |

24.4 |

| Georgia |

416 (26.5) |

4,423 (3.4) |

9.4 |

404 (25.7) |

4,271 (3.3) |

9.5 |

12 (0.8) |

152 (0.1) |

7.9 |

| Hawaii |

164 (40.3) |

624 (3.5) |

26.3 |

155 (38.1) |

590 (3.3) |

26.3 |

9 (2.2) |

34 (0.2) |

26.5 |

| Idaho |

119 (40.9) |

743 (3.3) |

16.0 |

113 (38.8) |

715 (3.2) |

15.8 |

6 (2.1) |

28 (0.1) |

21.4 |

| Illinois |

1,406 (31.6) |

5,941 (3.8) |

23.7 |

1,357 (30.5) |

5,772 (3.7) |

23.5 |

49 (1.1) |

169 (0.1) |

29.0 |

| Indiana |

319 (37.0) |

2,857 (3.4) |

11.2 |

304 (35.3) |

2,744 (3.3) |

11.1 |

15 (1.7) |

113 (0.1) |

13.3 |

| Iowa |

213 (30.0) |

1,359 (3.4) |

15.7 |

204 (28.7) |

1,310 (3.3) |

15.6 |

9 (1.3) |

49 (0.1) |

18.4 |

| Kansas |

131 (29.9) |

1,148 (3.0) |

11.4 |

125 (28.5) |

1,111 (2.9) |

11.3 |

6 (1.4) |

37 (0.1) |

16.2 |

| Kentucky |

185 (34.5) |

2,013 (3.6) |

9.2 |

170 (31.7) |

1,938 (3.5) |

8.8 |

15 (2.8) |

75 (0.1) |

20.0 |

| Louisiana |

196 (36.4) |

2,249 (3.6) |

8.7 |

190 (35.3) |

2,157 (3.4) |

8.8 |

6 (1.1) |

92 (0.1) |

6.5 |

| Maine |

45 (23.2) |

399 (3.1) |

11.3 |

— (—)** |

384 (3.0) |

—** |

— (—)** |

15 (0.1) |

—**,†† |

| Maryland |

431 (21.2) |

2,551 (3.5) |

16.9 |

414 (20.3) |

2,475 (3.4) |

16.7 |

17 (0.8) |

76 (0.1) |

22.4 |

| Massachusetts |

697 (20.8) |

2,661 (3.7) |

26.2 |

685 (20.4) |

2,571 (3.6) |

26.6 |

12 (0.4) |

90 (0.1) |

13.3 |

| Michigan |

817 (45.9) |

4,375 (3.9) |

18.7 |

790 (44.4) |

4,239 (3.7) |

18.6 |

27 (1.5) |

136 (0.1) |

19.9 |

| Minnesota |

463 (37.4) |

2,453 (3.5) |

18.9 |

454 (36.6) |

2,401 (3.4) |

18.9 |

9 (0.7) |

52 (0.1) |

17.3 |

| Mississippi |

74 (31.6) |

1,267 (3.3) |

5.8 |

— (—)** |

1,231 (3.2) |

—** |

— (—)** |

36 (0.1) |

—** |

| Missouri |

393 (38.3) |

2,687 (3.6) |

14.6 |

375 (36.5) |

2,594 (3.5) |

14.5 |

18 (1.8) |

93 (0.1) |

19.4 |

| Montana |

66 (45.2) |

— (—)** |

—** |

66 (45.2) |

379 (3.1) |

17.4 |

0 (0.0) |

— (—)** |

—**,†† |

| Nebraska |

112 (35.1) |

946 (3.6) |

11.8 |

112 (35.1) |

898 (3.4) |

12.5 |

0 (0.0) |

48 (0.2) |

0.0 |

| Nevada |

200 (33.2) |

1,137 (3.1) |

17.6 |

— (—)** |

1,115 (3.1) |

—** |

— (—)** |

22 (0.1) |

—** |

| New Hampshire |

65 (24.1) |

372 (3.0) |

17.5 |

— (—)** |

351 (2.9) |

—** |

— (—)** |

21 (0.2) |

—** |

| New Jersey |

1,041 (26.0) |

4,006 (3.9) |

26.0 |

1,018 (25.4) |

3,900 (3.8) |

26.1 |

23 (0.6) |

106 (0.1) |

21.7 |

| New Mexico |

39 (39.8) |

657 (2.7) |

5.9 |

— (—)** |

642 (2.6) |

—** |

— (—)** |

15 (0.1) |

—**,†† |

| New York |

1,990 (28.5) |

8,761 (3.7) |

22.7 |

1,927 (27.6) |

8,539 (3.6) |

22.6 |

63 (0.9) |

222 (0.1) |

28.4 |

| North Carolina |

603 (35.9) |

4,249 (3.5) |

14.2 |

576 (34.2) |

4,126 (3.4) |

14.0 |

27 (1.6) |

123 (0.1) |

22.0 |

| North Dakota |

77 (55.0) |

379 (3.3) |

20.3 |

— (—)** |

364 (3.2) |

—** |

— (—)** |

15 (0.1) |

—**,†† |

| Ohio |

795 (40.5) |

5,149 (3.7) |

15.4 |

756 (38.5) |

4,975 (3.6) |

15.2 |

39 (2.0) |

174 (0.1) |

22.4 |

| Oklahoma |

168 (42.2) |

1,678 (3.2) |

10.0 |

159 (39.9) |

1,641 (3.1) |

9.7 |

9 (2.3) |

37 (0.1) |

24.3 |

| Oregon |

249 (38.7) |

1,549 (3.4) |

16.1 |

240 (37.3) |

1,501 (3.3) |

16.0 |

9 (1.4) |

48 (0.1) |

18.8 |

| Pennsylvania |

626 (26.4) |

4,876 (3.5) |

12.8 |

611 (25.7) |

4,766 (3.4) |

12.8 |

15 (0.6) |

110 (0.1) |

13.6 |

| Puerto Rico |

35 (43.2) |

570 (2.0) |

6.1 |

35 (43.2) |

556 (2.0) |

6.3 |

0 (0.0) |

14 (0.0) |

—†† |

| Rhode Island |

69 (30.1) |

409 (3.8) |

16.9 |

— (—)** |

393 (3.6) |

—** |

— (—)** |

16 (0.1) |

—**,†† |

| South Carolina |

314 (43.1) |

2,140 (3.7) |

14.7 |

288 (39.5) |

2,063 (3.6) |

14.0 |

26 (3.6) |

77 (0.1) |

33.8 |

| South Dakota |

74 (50.3) |

450 (3.7) |

16.4 |

62 (42.2) |

429 (3.5) |

14.5 |

12 (8.2) |

21 (0.2) |

57.1 |

| Tennessee |

250 (35.4) |

2,732 (3.4) |

9.2 |

235 (33.2) |

2,641 (3.3) |

8.9 |

15 (2.1) |

91 (0.1) |

16.5 |

| Texas |

2,175 (35.6) |

12,902 (3.2) |

16.9 |

2,124 (34.7) |

12,505 (3.1) |

17.0 |

51 (0.8) |

397 (0.1) |

12.8 |

| Utah |

412 (40.4) |

1,917 (3.8) |

21.5 |

403 (39.5) |

1,863 (3.7) |

21.6 |

9 (0.9) |

54 (0.1) |

16.7 |

| Vermont |

34 (32.1) |

— (—)** |

—** |

— (—)** |

185 (3.2) |

—** |

— (—)** |

— (—)** |

—**,†† |

| Virginia |

568 (27.1) |

3,626 (3.5) |

15.7 |

559 (26.7) |

3,534 (3.4) |

15.8 |

9 (0.4) |

92 (0.1) |

9.8 |

| Washington |

396 (26.2) |

2,713 (3.0) |

14.6 |

375 (24.8) |

2,649 (2.9) |

14.2 |

21 (1.4) |

64 (0.1) |

32.8 |

| West Virginia |

49 (37.7) |

588 (3.1) |

8.3 |

— (—)** |

565 (3.0) |

—** |

— (—)** |

23 (0.1) |

—** |

| Wisconsin |

317 (36.8) |

2,297 (3.4) |

13.8 |

— (—)** |

2,243 (3.4) |

—** |

— (—)** |

54 (0.1) |

—** |

| Wyoming |

19 (31.7) |

— (—)** |

—** |

19 (31.7) |

221 (3.0) |

8.6 |

0 (0.0) |

— (—)** |

—**,†† |

| Total | 22,233 (31.5) | 135,740 (3.4) | 16.4 | 21,455 (30.4) | 132,279 (3.3) | 16.2 | 778 (1.1) | 4,017 (0.1) | 19.4 |

Abbreviation: ART = assisted reproductive technology.

* In cases of missing residency data (0.4%), the patient’s residence was assigned as the location where the ART procedure was performed.

† ART totals include infants conceived from ART procedures performed in 2015 and born in 2016 and infants conceived from ART procedures performed in 2016 and born in 2016. Total ART births exclude births to nonresidents.

§ Includes only the number of infants live born in a multiple-birth delivery. For example, if three infants were born in a live-birth delivery and one of the three infants was stillborn, the total number of live-born infants would be two. However, the two infants still would be counted as triplets.

¶ U.S. births include births to nonresidents. Source: CDC Wonder [Internet]. Natality public use data 2007–2016. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2018.

** To protect confidentiality, cells with values of 1–4 for ART infants and cells with values of 0–9 for all infants are suppressed. Also suppressed are data that can be used to derive suppressed cell values. These values are included in the totals.

†† Estimates on the basis of N = <20 in the denominator have been suppressed because such rates are considered unstable.

Adverse Perinatal Outcomes

Nationally, ART-conceived infants contributed to approximately 5.0% of all infants with low birthweight, 5.1% of all infants with moderate low birthweight, and 5.0% of all infants with very low birthweight (Table 5). In three reporting areas (Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Jersey), >10% of all infants with low birthweight were conceived with ART. Among ART-conceived infants, 23.6% had low birthweight compared with 8.2% among all infants. Approximately 4.0% of ART-conceived infants had very low birthweight compared with 1.4% among all infants.

TABLE 5. Number, percentage, and proportion of infants born with use of assisted reproductive technology,* by low birthweight category and female patient’s reporting area of residence† at time of treatment — United States and Puerto Rico, 2016.

| Patient’s reporting area of residence | <1,500 g (VLBW) |

Proportion of ART VLBW infants among all VLBW infants (%) | 1,500–2,499 g (MLBW) |

<2,500 g (LBW) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ART infants |

All infants§ |

ART infants |

All infants§ |

Proportion of ART MLBW infants among all MLBW infants (%) | ART infants |

All infants§ |

Proportion of ART LBW infants among all LBW infants (%) | ||

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | ||||

| Alabama |

21 (4.7) |

1,165 (2.0) |

1.8 |

129 (29.1) |

4,931 (8.3) |

2.6 |

150 (33.9) |

6,096 (10.3) |

2.5 |

| Alaska |

6 (7.4) |

109 (1.0) |

5.5 |

21 (25.9) |

552 (4.9) |

3.8 |

27 (33.3) |

661 (5.9) |

4.1 |

| Arizona |

58 (5.1) |

991 (1.2) |

5.9 |

264 (23.0) |

5,186 (6.1) |

5.1 |

322 (28.1) |

6,177 (7.3) |

5.2 |

| Arkansas |

14 (6.4) |

597 (1.6) |

2.3 |

47 (21.4) |

2,764 (7.2) |

1.7 |

61 (27.7) |

3,361 (8.8) |

1.8 |

| California |

302 (3.3) |

5,384 (1.1) |

5.6 |

1624 (17.9) |

28,092 (5.7) |

5.8 |

1,926 (21.2) |

33,476 (6.8) |

5.8 |

| Colorado |

45 (3.8) |

768 (1.2) |

5.9 |

292 (24.5) |

5,193 (7.8) |

5.6 |

337 (28.3) |

5,961 (8.9) |

5.7 |

| Connecticut |

46 (3.3) |

508 (1.4) |

9.1 |

271 (19.6) |

2,305 (6.4) |

11.8 |

317 (22.9) |

2,813 (7.8) |

11.3 |

| Delaware |

10 (3.7) |

196 (1.8) |

5.1 |

29 (10.7) |

786 (7.2) |

3.7 |

39 (14.4) |

982 (8.9) |

4.0 |

| District of Columbia |

— (—)¶ |

187 (1.9) |

—¶ |

— (—)¶ |

811 (8.2) |

—¶ |

59 (17.0) |

998 (10.1) |

5.9 |

| Florida |

113 (3.8) |

3,405 (1.5) |

3.3 |

628 (20.9) |

16,184 (7.2) |

3.9 |

741 (24.7) |

19,589 (8.7) |

3.8 |

| Georgia |

57 (3.7) |

2,387 (1.8) |

2.4 |

308 (19.9) |

10,317 (7.9) |

3.0 |

365 (23.5) |

12,704 (9.8) |

2.9 |

| Hawaii |

23 (5.9) |

265 (1.5) |

8.7 |

100 (25.8) |

1,272 (7.0) |

7.9 |

123 (31.7) |

1,537 (8.5) |

8.0 |

| Idaho |

10 (3.4) |

243 (1.1) |

4.1 |

65 (22.3) |

1,320 (5.9) |

4.9 |

75 (25.8) |

1,563 (7.0) |

4.8 |

| Illinois |

199 (4.5) |

2,369 (1.5) |

8.4 |

822 (18.7) |

10,618 (6.9) |

7.7 |

1,021 (23.2) |

12,987 (8.4) |

7.9 |

| Indiana |

26 (3.0) |

1,219 (1.5) |

2.1 |

181 (21.2) |

5,583 (6.7) |

3.2 |

207 (24.2) |

6,802 (8.2) |

3.0 |

| Iowa |

13 (1.8) |

469 (1.2) |

2.8 |

113 (16.0) |

2,192 (5.6) |

5.2 |

126 (17.9) |

2,661 (6.8) |

4.7 |

| Kansas |

16 (3.7) |

423 (1.1) |

3.8 |

78 (18.1) |

2,222 (5.8) |

3.5 |

94 (21.8) |

2,645 (7.0) |

3.6 |

| Kentucky |

25 (4.8) |

886 (1.6) |

2.8 |

102 (19.5) |

4,156 (7.5) |

2.5 |

127 (24.3) |

5,042 (9.1) |

2.5 |

| Louisiana |

32 (6.0) |

1,208 (1.9) |

2.6 |

107 (20.2) |

5,512 (8.7) |

1.9 |

139 (26.3) |

6,720 (10.6) |

2.1 |

| Maine |

— (—)¶ |

127 (1.0) |

—¶ |

— (—)¶ |

770 (6.1) |

—¶ |

29 (15.6) |

897 (7.1) |

3.2 |

| Maryland |

80 (3.9) |

1,201 (1.6) |

6.7 |

317 (15.6) |

5,047 (6.9) |

6.3 |

397 (19.6) |

6,248 (8.5) |

6.4 |

| Massachusetts |

94 (2.9) |

833 (1.2) |

11.3 |

491 15.0) |

4,497 (6.3) |

10.9 |

585 (17.9) |

5,330 (7.5) |

11.0 |

| Michigan |

86 (4.9) |

1,647 (1.5) |

5.2 |

465 (26.5) |

8,007 (7.1) |

5.8 |

551 (31.3) |

9,654 (8.5) |

5.7 |

| Minnesota |

32 (2.6) |

784 (1.1) |

4.1 |

258 (20.9) |

3,786 (5.4) |

6.8 |

290 (23.5) |

4,570 (6.6) |

6.3 |

| Mississippi |

7 (3.0) |

803 (2.1) |

0.9 |

55 (23.5) |

3,542 (9.3) |

1.6 |

62 (26.5) |

4,345 (11.5) |

1.4 |

| Missouri |

43 (4.4) |

1,072 (1.4) |

4.0 |

233 (23.7) |

5,401 (7.2) |

4.3 |

276 (28.1) |

6,473 (8.7) |

4.3 |

| Montana |

12 (8.2) |

136 (1.1) |

8.8 |

37 (25.3) |

830 (6.8) |

4.5 |

49 (33.6) |

966 (7.9) |

5.1 |

| Nebraska |

11 (3.5) |

332 (1.2) |

3.3 |

64 (20.2) |

1,537 (5.8) |

4.2 |

75 (23.7) |

1,869 (7.0) |

4.0 |

| Nevada |

22 (3.8) |

463 (1.3) |

4.8 |

135 (23.6) |

2,602 (7.2) |

5.2 |

157 (27.4) |

3,065 (8.5) |

5.1 |

| New Hampshire |

8 (3.0) |

121 (1.0) |

6.6 |

40 (14.9) |

668 (5.4) |

6.0 |

48 (17.9) |

789 (6.4) |

6.1 |

| New Jersey |

155 (3.9) |

1,425 (1.4) |

10.9 |

740 (18.7) |

6,847 (6.7) |

10.8 |

895 (22.7) |

8,272 (8.1) |

10.8 |

| New Mexico |

— (—)¶ |

365 (1.5) |

—¶ |

— (—)¶ |

1,862 (7.5) |

—¶ |

38 (39.6) |

2,227 (9.0) |

1.7 |

| New York |

228 (3.4) |

3,120 (1.3) |

7.3 |

1206 (17.9) |

15,453 (6.6) |

7.8 |

1,434 (21.3) |

18,573 (7.9) |

7.7 |

| North Carolina |

75 (4.5) |

1,976 (1.6) |

3.8 |

350 (21.2) |

9,151 (7.6) |

3.8 |

425 (25.7) |

11,127 (9.2) |

3.8 |

| North Dakota |

16 (11.4) |

141 (1.2) |

11.3 |

40 (28.6) |

611 (5.4) |

6.5 |

56 (40.0) |

752 (6.6) |

7.4 |

| Ohio |

112 (5.8) |

2,146 (1.6) |

5.2 |

423 (21.8) |

9,835 (7.1) |

4.3 |

535 (27.6) |

11,981 (8.7) |

4.5 |

| Oklahoma |

20 (5.1) |

700 (1.3) |

2.9 |

105 (26.6) |

3,410 (6.5) |

3.1 |

125 (31.6) |

4,110 (7.8) |

3.0 |

| Oregon |

8 (1.3) |

434 (1.0) |

1.8 |

138 (21.9) |

2,540 (5.6) |

5.4 |

146 (23.2) |

2,974 (6.5) |

4.9 |

| Pennsylvania |

70 (3.0) |

1,963 (1.4) |

3.6 |

390 (16.8) |

9,368 (6.7) |

4.2 |

460 (19.8) |

11,331 (8.1) |

4.1 |

| Puerto Rico |

— (—)¶ |

376 (1.3) |

—¶ |

— (—)¶ |

2,509 (8.9) |

—¶ |

30 (37.5) |

2,885 (10.2) |

1.0 |

| Rhode Island |

9 (4.0) |

157 (1.5) |

5.7 |

41 (18.2) |

701 (6.5) |

5.8 |

50 (22.2) |

858 (7.9) |

5.8 |

| South Carolina |

41 (5.7) |

1,029 (1.8) |

4.0 |

163 (22.8) |

4,459 (7.8) |

3.7 |

204 (28.5) |

5,488 (9.6) |

3.7 |

| South Dakota |

6 (4.1) |

121 (1.0) |

5.0 |

34 (23.3) |

709 (5.8) |

4.8 |

40 (27.4) |

830 (6.8) |

4.8 |

| Tennessee |

42 (6.0) |

1,290 (1.6) |

3.3 |

160 (22.9) |

6,141 (7.6) |

2.6 |

202 (28.9) |

7,431 (9.2) |

2.7 |

| Texas |

308 (5.1) |

5,714 (1.4) |

5.4 |

1353 (22.4) |

27,731 (7.0) |

4.9 |

1,661 (27.5) |

33,445 (8.4) |

5.0 |

| Utah |

58 (5.7) |

562 (1.1) |

10.3 |

249 (24.7) |

3,060 (6.1) |

8.1 |

307 (30.4) |

3,622 (7.2) |

8.5 |

| Vermont |

5 (4.7) |

72 (1.3) |

6.9 |

27 (25.5) |

322 (5.6) |

8.4 |

32 (30.2) |

394 (6.8) |

8.1 |

| Virginia |

87 (4.2) |

1,513 (1.5) |

5.8 |

335 (16.3) |

6,750 (6.6) |

5.0 |

422 (20.5) |

8,263 (8.1) |

5.1 |

| Washington |

70 (4.7) |

880 (1.0) |

8.0 |

247 (16.4) |

4,912 (5.4) |

5.0 |

317 (21.1) |

5,792 (6.4) |

5.5 |

| West Virginia |

— (—)¶ |

270 (1.4) |

—¶ |

— (—)¶ |

1,565 (8.2) |

—¶ |

31 (24.6) |

1,835 (9.6) |

1.7 |

| Wisconsin |

28 (3.3) |

832 (1.2) |

3.4 |

154 (18.0) |

4,093 (6.1) |

3.8 |

182 (21.3) |

4,925 (7.4) |

3.7 |

| Wyoming |

— (—)¶ |

102 (1.4) |

—¶ |

— (—)¶ |

526 (7.1) |

—¶ |

9 (15.3) |

628 (8.5) |

1.4 |

| Total | 2,762 (4.0) | 55,486 (1.4) | 5.0 | 13,614 (19.6) | 269,238 (6.8) | 5.1 | 16,376 (23.6) | 324,724 (8.2) | 5.0 |

Abbreviations: ART = assisted reproductive technology; LBW = low birthweight; MLBW = moderate low birthweight; VLBW = very low birthweight.

* ART totals include infants conceived from ART procedures performed in 2015 and born in 2016 and infants conceived from ART procedures performed in 2016 and born in 2016. Total ART infants exclude births to nonresidents and include only infants with birthweight data available.

† In cases of missing residency data (0.4%), the patient’s residence was assigned as the location where the ART procedure was performed.

§ U.S. births include births to nonresidents. Source: CDC Wonder [Internet]. Natality public use data 2007–2016. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2018.

¶ To protect confidentiality, cells with values of 1–4 for ART infants and cells with values of 0–9 for all infants are suppressed. Also suppressed are data that can be used to derive suppressed cell values. These values are included in the totals.

Nationally, ART contributed to approximately 5.5% of all infants born very preterm, 6.0% early preterm, 5.1% late preterm, and 5.3% preterm (Table 6). In Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Jersey, the contribution of ART to preterm infants exceeded >10% in all categories of preterm birth. Among ART-conceived infants, rates for preterm birth were 5% very preterm, 9.5% early preterm, 20.4% late preterm, and 29.9% preterm. Corresponding rates of preterm birth among all infants born were 1.6% (<32 weeks), 2.8% (<34 weeks), 7.1% (34–36 weeks), and 9.9% (<37 weeks). Infants born at gestational weeks 34–36 (late preterm births) accounted for the majority of preterm infants among both ART-conceived infants and all births (68% and 72%, respectively).

TABLE 6. Number, percentage, and proportion of infants born with use of assisted reproductive technology,* by preterm gestational age category and female patient’s reporting area of residence† at time of treatment — United States and Puerto Rico, 2016.

| Patient’s reporting area of residence | VPTB < 32 weeks |

Proportion of ART VPTB infants among all VPTB infants (%) | Early PTB <34 weeks |

Late PTB 34–36 weeks |

PTB <37 weeks |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ART infants |

All infants§ |

ART infants |

All infants |

Proportion of ART early PTB infants among all early PTB infants (%) | ART infants |

All infants |

Proportion of ART late PTB infants among all late PTB infants (%) | ART infants |

All infants§ |

Proportion of ART PTB infants among all PTB infants (%) | ||

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |||||

| Alabama |

35 (7.9) |

1,276 (2.2) |

2.7 |

63 (14.2) |

2,100 (3.6) |

3 |

123 (27.8) |

4,983 (8.4) |

2.5 |

186 (42.0) |

7,083 (12.0) |

2.6 |

| Alaska |

7 (8.5) |

127 (1.1) |

5.5 |

7 (8.5) |

240 (2.1) |

2.9 |

19 (23.2) |

759 (6.8) |

2.5 |

26 (31.7) |

999 (8.9) |

2.6 |

| Arizona |

78 (6.9) |

1,119 (1.3) |

7.0 |

146 (13.0) |

1,969 (2.3) |

7.4 |

244 (21.7) |

5,685 (6.7) |

4.3 |

390 (34.7) |

7,654 (9.1) |

5.1 |

| Arkansas |

16 (7.4) |

707 (1.8) |

2.3 |

30 (13.9) |

1,166 (3.0) |

2.6 |

51 (23.6) |

2,991 (7.8) |

1.7 |

81 (37.5) |

4,157 (10.9) |

1.9 |

| California |

389 (4.2) |

6,203 (1.3) |

6.3 |

774 (8.4) |

11,227 (2.3) |

6.9 |

1,656 (18.0) |

30,847 (6.3) |

5.4 |

2,430 (26.4) |

42,074 (8.6) |

5.8 |

| Colorado |

49 (4.0) |

830 (1.2) |

5.9 |

126 (10.3) |

1,612 (2.4) |

7.8 |

282 (23.1) |

4,286 (6.4) |

6.6 |

408 (33.4) |

5,898 (8.9) |