SUMMARY

Aims: Cognitive impairment and dementia are common features of Parkinson's disease (PD). Patients with Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD) often have significant cholinergic defects, which may be treated with cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs). The objective of this review was to consider available efficacy, tolerability, and safety data from studies of ChEIs in PDD. Discussions: A literature search resulted in the identification of 20 relevant publications. Of these, the treatment of PD patients with rivastigmine, donepezil, or galantamine was the focus of six, eleven, and two studies respectively, while one study reported use of both tacrine and donepezil. The majority of studies were small (<40 patients), with the exception of two large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that are the main focus of this review. In the smaller studies, treatment benefits were reported on a range of outcome measures, though results were extremely variable. While the full results of a large RCT of donepezil in patients with PDD are not yet available, significant treatment differences were reported on the CIBIC‐plus at the highest treatment dose. A trend toward improvement was also observed in treated patients on the ADAS‐cog. The second large RCT found significant improvements in rivastigmine‐treated patients compared with placebo on both the ADAS‐cog (P < 0.001) and the ADCS‐CGIC (P < 0.007), as well as on all secondary efficacy outcomes. Consequently, rivastigmine is now widely approved for the symptomatic treatment of mild to moderate PDD. Conclusions: Taken together, these studies suggest that ChEIs are efficacious in the treatment of PDD.

Keywords: Cholinesterase inhibitors, Donepezil, Parkinson's disease dementia, Review, Rivastigmine

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a chronic degenerative neurological disease characterized by tremor, muscle rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability [1]. PD is one of the most common neurodegenerative disorders, with an estimated incidence of 14 per 100,000 [2]. In addition to the classical motor symptoms of PD, many patients with PD also suffer cognitive impairment and dementia [3], particularly older patients with more severe extrapyramidal signs [4]. The estimated point prevalence of dementia in patients with PD is 30%[5]. Furthermore, a 12‐year longitudinal cohort study suggests that the majority of patients with PD develop dementia within 12 years, meaning dementia is a relatively common feature of the disease [6]. The mean duration from the onset of PD to development of dementia is approximately 10 years [7]. Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD) usually manifests with impairment of executive function and attention, although other deficits, including memory and visuoconstruction impairment, usually develop during the course [8, 9]. Behavioral symptoms, including depression, anxiety, hallucinations, and apathy, also commonly occur [10, 11, 12, 13]. The emergence of visual hallucinations some time after the onset of Parkinsonian symptoms is highly predictive of PDD. In a cohort of 208 patients with PD, 48% of the patients with visual hallucinations at baseline developed PDD within 1 year [14]. Another study with longitudinal follow‐up to autopsy of 42 patients with PD also showed visual hallucinations to be a strong predictor for PDD (odds ratio 21.3) [3]. Where hallucinations are present during the initial onset of Parkinsonism they are more indicative of Lewy body dementia [15, 16]. Dementia in PD is associated with more rapid motor and functional decline [17] and increased mortality [18]. It is a great source of distress to patients with PD and their families [19, 20], and a more frequent cause of institutionalization in these patients than the motor symptoms of the disease [21].

The pathology of PD initially occurs in the brainstem. Hallmark features include Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites – proteinaceous inclusion bodies – in the neuronal soma and processes of the medulla oblongata [22, 23]. The disease progresses to involve other parts of the brain, following a characteristic ascending pathway that next affects the midbrain (most notably the substantia nigra pars compacta), then the mesocortex, and finally the neocortex [24]. In the pars compacta region of the substantia nigra, the formation of PD‐related inclusion bodies within dopaminergic neurones finally leads to cell death, and a subsequent deficit of dopamine that is associated with the characteristic motor symptoms of the disease [1, 25].

Although the depletion of dopamine is the main neurochemical impairment in PD, significant deficits in cholinergic transmission are also present, particularly in patients with PDD [26]. These deficits are largely localized to the cholinergic system of the basal forebrain and brainstem, in contrast to patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD), where cholinergic deficits are primarily seen in the hippocampus [27]. In patients with PDD, cholinergic deficits may be greater than in AD patients with similar levels of cognitive impairment [28]. Observations of substantial cortical cholinergic deficits in patients with PDD led to the suggestion that the impact of the disease on the cholinergic circuits might be effectively treated with cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs). This was first investigated in a small study by Hutchinson and Fazzini in 1996, in which seven patients with PDD treated for at least 2 months with up to 60 mg/day tacrine showed marked improvements in cognition [29]. The results of this study provided the rationale for large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of ChEIs in PDD. Two large RCTs (one in rivastigmine, the other in donepezil) have now been completed [30, 31], as well as several smaller RCTs and a number of open studies and case series.

The present objective is to review available efficacy, tolerability, and safety data from studies of ChEIs in PDD, and consider the value of these agents in the management of this condition. A 2004 review of ChEIs in the treatment of PDD and Lewy body dementia identified a number of publications reporting the use of ChEIs in patients with PD, mostly open studies or small case series [32]. A 2006 Cochrane review of efficacy, safety, tolerability, and health economic data relating to the use of ChEIs in PDD considered the large RCT of rivastigmine only [33]. All other studies were excluded due to being of open‐label design or the use of diagnostic criteria for PDD outside those specified by the review authors. This current review will consider all available data retrieved by a systematic literature search, and will focus predominantly on the large RCTs that have been published or presented since 2004.

Methods

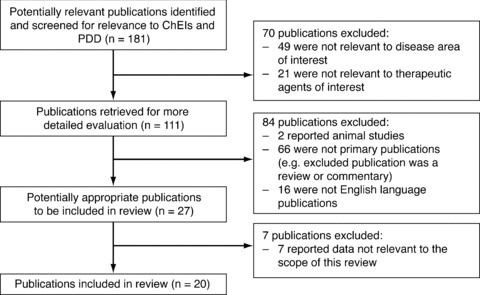

A systematic search of literature indexed by MEDLINE or PubMed during the past 10 years was carried out, using combinations of the following terms: ChEI, PD, dementia, cognitive impairment, PDD, rivastigmine, donepezil, galantamine. The bibliographies of included publications were used to supplement the search, as were listings of recent key congress presentations. Each publication or presentation yielded by this search was then assessed for relevance to the current review. Inclusion criteria were English language, human studies, and relevance to PDD and ChEIs. Any publications not reporting on a trial or study of ChEIs in patients with PD were excluded from the results. The literature search returned a total of 20 publications reporting on studies of ChEIs in patients with PD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of publication selection for review of ChEIs in PDD.

Results

Of the 20 publications returned by the literature search, the treatment of PD patients with rivastigmine was reported in 6 publications (Table 1), treatment with donepezil in 11 (Table 2), treatment with galantamine in 2 (Table 3), and treatment with both tacrine and donepezil (with pooled results) in 1 (Table 2). Eleven of the publications reported on open‐label studies, two described case series, five reported on RCTs (two of which were crossover studies [34, 35]), one described an active extension to one of the larger RCTs [36], and one reported the results of an add‐on study of a subgroup of patients from one of the large RCTs [37]. Most of the studies were small, with only two RCTs [30, 31] and active extension [36] including more than 40 patients.

Table 1.

Summary of studies of rivastigmine in patients with Parkinson's disease

| Study | Total patients | Patients completing study | Study design | Study duration (weeks) | Mean age (years) | Mean baseline MMSE | Outcome measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reading 2001 [41] | 15 | 12 | Open/washout | 14/3 | 71 | 20.4 | MMSE, NPI | Improvements on MMSEa (5 points) and NPIa (25 points) with deterioration after washout |

| Inclusion criteria: PD (UK Brain Bank) for ≥2 years; hallucinations for ≥3 months; stable medication regime not including neuroleptic/anticholinergic agents; caregiver | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: MMSE <10; significant urinary symptoms; history of cardiovascular disease or cardiac arrhythmia | ||||||||

| Giladi 2003 [53] | 28 | 20 | Open/washout | 26/8 | 75 | 20.5 | ADAS‐cog, UPDRS, CGI, MMSE | Improvements in mental subscale of UPDRSa (1.8 points), ADAS‐coga (7.3 points), and attention component of MMSEa; no significant change in motor subscale of UPDRS or total MMSE (improvement of 1.4 points) |

| Inclusion criteria: PD (UK Brain Bank) for ≥2 years; dementia due to PD (DSM‐IV) occurring ≥1 year after PD diagnosis; MMSE 12–26 | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: significant depression; active malignancy; uncontrolled heart disease; diabetes; hypertension; other psychiatric disorders; severe head trauma; stroke; significant brain lesions; anticholinergic drugs; or amantadine | ||||||||

| Bullock 2002 [38] | 5 | 5 | Case series | 20–52 | 75 | 20.6 | MMSE | Improvements in cognition (9 points on the MMSE in 1 patient after 5 months) and behavioral symptoms, particularly visual hallucinations |

| Inclusion criteria: diagnosis of PDD | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: lack of informed consent; safety concerns over concurrent diseases | ||||||||

| Dujardin 2006 [37] | 28 (16 randomized to active group) | 16 from active group | RCT | 24 | 73 | 21.5 | MDRS | Improvement in total MDRS scoreb (5.8 points) |

| Inclusion criteria: PD (UK Brain Bank); dementia (DSM‐IV); MMSE 10–24; onset of cognitive symptoms occurring ≥2 years after PD diagnosis | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: any other neurodegenerative disorder or other cause of dementia; major depression; active, uncontrolled seizure disorder; any disability or unstable disease unrelated to PD; known hypersensitivity to drugs similar to rivastigmine; use of cholinesterase inhibitors or anticholinergic drugs during the four weeks before randomization | ||||||||

| Emre 2004 [30] | 541 (362 randomized to active group) | 263 from active group | RCT | 24 | 73 | 19.4 | ADAS‐cog, ADCS‐CGIC, ADCS‐ADL, NPI, MMSE, CDR, D‐KEFS, Ten Point Clock‐Drawing test | Significant treatment differences on ADAS‐cog (2.1 points; treatment difference of 2.9 pointsc vs. placebo), ADCS‐CGIC (treatment difference of 0.5 points vs. placebo), ADCS‐ADL (1.1 points; treatment difference of 2.5 points vs.placebo), NPI (2 points; treatment difference of 2.15 pointsc vs. placebo), MMSE (0.8 points; treatment difference of 1.0 points vs. placebo), CDR (improvement of 31 msec; treatment difference of 294.84 msecondc vs. placebo), D‐KEFS (1.7 correct responses; treatment difference of 2.8 vs. placebo), and Ten Point Clock‐Drawing test (0.5 points; treatment difference of 1.1 points vs.placebo) (all b) |

| Inclusion criteria: PD (UK Brain Bank); dementia (DSM‐IV); MMSE 10–24; onset of cognitive symptoms occurring ≥2 years after PD diagnosis; caregiver | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: any other neurodegenerative disorder or other cause of dementia; major depression; active, uncontrolled seizure disorder; any disability or unstable disease unrelated to PD; known hypersensitivity to drugs similar to rivastigmine; use of cholinesterase inhibitors or anticholinergic drugs during the four weeks before randomization | ||||||||

| Poewe 2006 [36] | 334 | 273 | Active treatment extension to RCT [30] | 24 | 72 | 19.5 | ADAS‐cog, ADCS‐ADL, NPI, MMSE, D‐KEFS | Improvements on ADAS‐cog (2.0 points), NPI (2.4 points) and MMSE (1.4 points) (vs.baseline at start of RCT); no significant change in motor symptoms |

| Inclusion criteria: patients who completed the Emre 2004 double‐blind study, or who dropped out but returned for scheduled efficacy assessments and had no significant protocol violations | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: none stated | ||||||||

aSignificant versus baseline.

bSignificant versus placebo.

cDifference of least‐square means.

UK Brain Bank, criteria for diagnosis of PD as specified by the UK Parkinson's Society Brain Bank [54, 55].

DSM‐IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition [56]; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; ADAS‐cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; CGI, Clinical Global Impressions scale; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; ADCS‐CGIC, Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study‐Clinician's Global Impression of Change; ADCS‐ADL, Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study‐Activities of Daily Living; CDR, Cognitive Drug Research Power of Attention tests; D‐KEFS, verbal fluency test from the Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System test battery; MDRS, Mattis Dementia Rating Scale.

Table 2.

Summary of studies of donepezil in patients with Parkinson's disease

| Study | Total patients | Patients completing study | Study design | Study duration (weeks) | Mean age (years) | Mean baseline MMSE | Outcome measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bergman 2002 [50] | 6 | 6 | Open | 6 | 69 | 20.2 | MMSE, GDS, CGI, SAPS | Improvements on CGIa (3.7 points) and SAPSa (18.9 points); no change on MMSE (improvement of 0.5 points) or GDS (improvement of 0.1 points) |

| Inclusion criteria: PD (UPDRS); diagnosis of dementia based on MMSE and GDS | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: none stated | ||||||||

| Fabbrini 2002 [39] | 8 | 8 | Open | 8 | 74 | 25.2 | MMSE, PPRS | Improvement on PPRSa (3.9 points); no significant change on MMSE (deterioration of 0.3 points) |

| Inclusion criteria: nondemented PD patients experiencing hallucinations and/or delusions | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: use of antipsychotics | ||||||||

| Minett 2003 [47] | 15 | 11 | Open treat/withdraw/treat | 20/6/12 | Not reported | 17.5 | MMSE, NPI | Improvements after 20 weeks on MMSEa (3.8 points) and in behavior (particularly hallucinations) which were lost on withdrawal of treatment and restored on recommencement |

| Inclusion criteria: probable PDD (UK Brain Bank) | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: severe gastrointestinal, renal or liver disease; history of cardiac bradyarrhythmias, asthma or bladder outflow obstruction; recent history of cerebrovascular disease; use of cholinergic, anticholinergic, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication or neuroleptics | ||||||||

| Thomas 2005 [48] | 40 | 35 | Open | 20 | 71 | 18.3 | MMSE, NPI | Improvements on MMSEa (3.2 points) and NPIa (12 points); no significant change in motor symptoms |

| Inclusion criteria: PD (UK Brain Bank); dementia due to PD (DSM‐IV); MMSE <24; cognitive fluctuations and/or hallucinations; caregiver | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: use of cholinergic, anticholinergic, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or antipsychotics; severe gastrointestinal, renal or liver disease; history of bradyarrhythmia, asthma or bladder outflow obstruction; recent history of cerebrovascular disease | ||||||||

| Muller 2006 [49] | 24 | 14 | Open | 12 | 71 | 21.6 | MMSE, CGI | Improvement in MMSEa (3.1 points); no significant change on CGI or in motor symptoms |

| Inclusion criteria: PD (UK Brain Bank); dementia due to PD (DSM‐IV) occurring ≥2 years after PD diagnosis; MMSE 10–26; stable dopaminergic regime; caregiver | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: history of major depression; any other primary neurodegenerative disorders or other causes of dementia; seizures; prior long‐term intake of anticholinergics | ||||||||

| Rowan 2007 [64] | 23 | 23 | Open | 20 | Not reported (range 61–80) | 18 | CDR | Improvements on Power of Attentiona and Reaction Time Variabilitya components of the CDR; no significant improvements on Continuity of Attention or Cognitive Reaction Time components |

| Inclusion criteria: PD (UK Brain Bank); dementia due to PD (DSM‐IV); MMSE <24; cognitive fluctuations and/or hallucinations; caregiver | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: use of cholinergic, anticholinergic, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or antipsychotics; severe gastrointestinal, renal or liver disease; history of bradyarrhythmia, asthma or bladder outflow obstruction; recent history of cerebrovascular disease | ||||||||

| Kurita 2003 [40] | 3 | 2 | Case series | 2–56 | 70 | 22.6 | MMSE, HY | Improvement in hallucinations, some improvement in cognition (5 points on MMSE in 1 patient) |

| Inclusion criteria: PD of ≥6 years; visual hallucinations | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: none stated | ||||||||

| Aarsland 2002 [34] | 14 | 12 | RCT crossover | 20 (10 + 10) | 71 | 20.8 | MMSE, CIBIC‐plus | Improvement on MMSEb (2 points; 1.8 points treatment difference vs. placebo) and CIBIC‐plusb (treatment difference of 0.8 points vs. placebo) |

| Inclusion criteria: mild‐to‐severe Parkinsonism (HY <5); age 45–95 years; evidence of decline in memory and at least one other category of cognitive function, occurring ≥1 year after onset of Parkinsonism; MMSE 16–26; caregiver | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: brain disease other than PD or other severe medical disorders; use of anticholinergic drugs or psychotropic drugs with anticholinergic effects | ||||||||

| Leroi 2004 [46] | 16 (7 randomized to active group) | 2 from active group | RCT | 18 | 69 | 26.0 | MMSE, NPI, MDRS, BTA | Improvement on memory component of MDRSb (2.6 points; treatment difference of 5.32 points vs. placebo); no significant change in MMSE (deterioration of 0.67 points) or other outcome measures |

| Inclusion criteria: PD (UK Brain Bank) with dementia/cognitive impairment (DSM‐IV) | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: MMSE <10; nonambulatory; history of substance abuse or dependence; severe cardiac, vascular or renal disease; inability to tolerate donepezil | ||||||||

| Ravina 2005 [35] | 22 | 19 | RCT crossover with washout | 10/6/10 | 73 | 22.2 | ADAS‐cog, MMSE, MDRS, CGI, BPRS | Improvements on MMSEb (2.3 points; treatment difference of 2 points quoted vs. placebo) and CGIb (0.37 points treatment difference vs. placebo); no significant changes on ADAS‐cog, MDRS, or BPRS |

| Inclusion criteria: clinical diagnosis of idiopathic PD; >40 years of age; dementia (DSM‐IV) developing ≥1 year after the motor manifestations of PD; MMSE 17–26 | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: any other causes of dementia; pregnancy or lactation; use of cholinergic/anticholinergic agents except amantadine or tolterodine within the 2 weeks prior to screening; medical conditions or uncontrolled psychosis that might interfere with the safe conduct of the study | ||||||||

| Dubois 2007 [31] | 550 (195 to 5 mg/day, 182 to 10 mg/day) | Not reported | RCT | 24 | 72 | 21 | ADAS‐cog, CIBIC‐plus, DAD, NPI, MMSE, BTA, D‐KEFS | Improvements on MMSEb, BTAb, D‐KEFSb and CIBIC‐plus (numerical values not provided); no significant improvements on ADAS‐cog (treatment difference of 3.42 points vs. placebo for 10 mg/day group), DAD or NPI, and no significant change in motor symptoms |

| Inclusion criteria: PD (UK Brain Bank); ≥40 years of age; mild‐to‐moderate dementia (DSM‐IV) occurring >1 year after PD onset; MMSE 10–26 | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: none stated | ||||||||

| Other studies | ||||||||

| Werber 2001 [65] | 11 (7 on tacrine, 4 on donepezil; results pooled) | 11 | Open | 26 | 75 | 18.6 | MMSE, ADAS‐cog, GDS, SPES | Improvement on ADAS‐coga (3.2 points); no significant change on MMSE (improvement of 1.3 points), GDS (improvement of 0.2 points), or in motor function (SPES; improvement of 2.6 points) |

| Inclusion criteria: diagnosis of PD for several years prior to onset of dementia; PDD (DSM‐IV); MMSE ≤26; no history of other neurological or psychiatric disorders; no focal findings on CT or MRI; normal thyroid and liver function; normal transcobalamine level and negative for syphilis | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: none stated | ||||||||

aSignificant versus baseline.

bSignificant versus placebo.

UK Brain Bank, criteria for diagnosis of PD as specified by the UK Parkinson's Society Brain Bank [54, 55]; DSM‐IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition [56]; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; ADAS‐cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale; GDS, Global Deterioration Scale; SPES, Short Parkinson Evaluation Scale; CIBIC‐plus, Clinician's Interview‐Based Impression of Change plus caregiver input; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; SAPS, Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; CGI, Clinical Global Impressions scale; PPRS, Parkinson Psychosis Rating Scale; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; HY, Hoehn and Yahr disability classification; CDR, Cognitive Drug Research Power of Attention tests; D‐KEFS, verbal fluency test from the Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System test battery; MDRS, Mattis Dementia Rating Scale; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; DAD, Disability Assessment for Dementia scale; BTA, Brief Test of Attention.

Table 3.

Summary of studies of galantamine in patients with Parkinson's disease

| Study | Total patients | Patients completing study | Study design | Study duration (weeks) | Mean age (years) | Mean baseline MMSE | Outcome measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aarsland 2003 [51] | 16 | 13 | Open | 8 | 76 | 17.7 | MMSE, Ten Point Clock‐Drawing test, verbal fluency measure of MDRS, NPI | Improvements on Ten Point Clock‐Drawing testa and in hallucinations (improvements seen in 7 of 9 patients with hallucinations at baseline); no significant change in mean MMSE (improvement of 2.3 points) |

| Inclusion criteria: PD (UK Brain Bank); dementia due to PD (DSM‐IV) occurring ≥1 year after PD diagnosis; caregiver | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: severe disease other than PD; other conditions that could cause neuropsychiatric symptoms; use of anticholinergics, tricyclic antidepressants, or antipsychotic agents | ||||||||

| Litvinenko 2008 [52] | 21 | 21 | Open | 24 | 69 | 17.6 | MMSE, ADAS‐cog, Ten Point Clock‐Drawing test, FAB, NPI, DAD | Improvements on MMSEa (3.7 points), ADAS‐coga (3.3 points), Ten Point Clock‐Drawing testa (0.9 points), and FABa (2.5 points) |

| Inclusion criteria: PD (UK Brain Bank); dementia due to PD (ICD‐10) occurring ≥2 years after PD diagnosis; MMSE <25; ability to perform neuropsychiatric tests; caregiver | ||||||||

| Exclusion criteria: cardiovascular disease, bronchial obstruction, or hepatic/renal pathology; history of acute cerebrovascular episodes, depression, delusions, or other brain disease; use of cholinolytics, cholinesterase inhibitors, or nootropes | ||||||||

aSignificant versus baseline.

UK Brain Bank, criteria for diagnosis of PD as specified by the UK Parkinson's Society Brain Bank [54, 55]; DSM‐IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, American Psychiatric Association [56]; ICD‐10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision, World Health Organization; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; ADAS‐cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; FAB, Frontal Assessment Battery; MDRS, Mattis Dementia Rating Scale; DAD, Disability Assessment for Dementia scale.

The majority of the studies were restricted to PD patients with dementia, but some studies included nondemented patients with PD suffering from hallucinations and/or delusions [38, 39, 40, 41]. The most frequently used outcome measures were the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) [42], the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS‐cog) [43], and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) [44]. The motor subscale of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) was routinely used to assess any change in motor symptoms over the course of the studies [45].

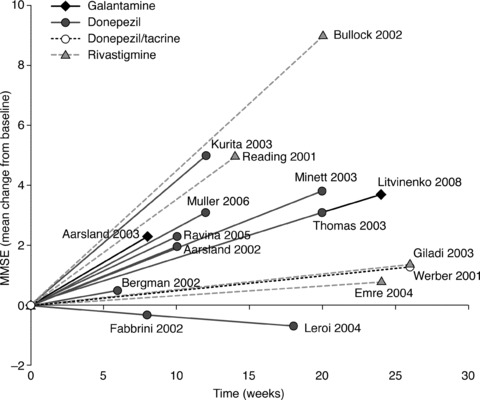

Each of the smaller studies (≤40 patients) reported some degree of improvement on at least one of the outcome measures assessed, though the outcome measures on which improvements were seen varied, and sometimes conflicted, between studies. Two small RCTs of donepezil in patients with PDD reported significant differences versus placebo on the MMSE and measures of global change [34, 35]. The third small RCT of donepezil demonstrated significant treatment differences versus placebo on the memory component of the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, a measure of global cognitive ability, but no significant differences on the MMSE or on any other outcome measure [46]. While some small open studies of donepezil in PDD reported significant improvements in MMSE versus baseline [47, 48, 49], others reported no significant changes on the MMSE, but did show significant improvements on other outcome measures [39, 50]. Figure 2 shows mean changes from baseline on the MMSE for all studies where these values were reported.

Figure 2.

Changes from baseline in mean MMSE score* in studies of galantamine [51, 52], donepezil [34, 35, 39, 40, 46, 48, 49, 50], donepezil or tacrine (with pooled results) [65], and rivastigmine [30, 38, 41, 53]. *Positive changes from baseline on the MMSE indicate improvement; negative values indicate deterioration.

Improvements in psychotic symptoms, particularly hallucinations, were observed in several studies [38, 39, 40, 47]. One case series of PD patients given rivastigmine reported that, of four patients with hallucinations at baseline, treatment with rivastigmine for between 5 and 13 months resolved hallucinations in two patients and improved them in the remaining two [38]. In an open study of eight PD patients with hallucinations or delusions given donepezil, the mean score on the hallucinations subitem of the Parkinson Psychosis Rating Scale was significantly improved from baseline after 2 months (P < 0.05) [39]. Similarly, an open study following 15 patients with PDD treated with donepezil reported significant improvements on the hallucinations domain of the NPI after 20 weeks (P= 0.029). These improvements were lost on withdrawal from treatment, but regained upon recommencement of therapy [47]. A case series of three PD patients treated with donepezil found hallucinations to be reduced in two patients after 3–4 months’ treatment, but the third patient experienced delusions that appeared to be linked to donepezil treatment, and discontinued treatment after 17 days [40]. Of the two studies on galantamine, one 8‐week study saw improvements in hallucinations, but no significant change on the MMSE [51], while a longer, 24‐week study found significant improvements (compared with baseline) on several outcome measures, including MMSE and ADAS‐cog [52]. Apart from isolated cases where motor symptoms worsened, the overall trend across all ChEIs was toward no significant change on the motor subscale of the UPDRS.

While these smaller studies of ChEI treatment in patients with PDD are interesting, the small sample sizes and the uncontrolled design involved in these studies make it difficult to draw valid conclusions about the results. However, two of the RCTs retrieved by the literature search were large, including more than 500 patients each [30, 31], providing a greater degree of statistical certainty when considering the findings.

Rivastigmine

The 24‐week, randomized, multicenter, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study of rivastigmine in PDD carried out by Emre and colleagues [30] included 541 patients with mild‐to‐moderate dementia, which developed at least 2 years after a clinical diagnosis of PD (to distinguish PDD from Lewy body dementia). The primary efficacy outcomes in this study were the ADAS‐cog and the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study‐Clinician's Global Impression of Change (ADCS‐CGIC) [57]. Secondary outcomes included the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study‐Activities of Daily Living (ADCS‐ADL) [58], the Cognitive Drug Research Power of Attention tests (CDR) [59], the verbal fluency test from the Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System test battery (D‐KEFS) [60], the Ten Point Clock‐Drawing test [61], MMSE, and NPI.

A total of 362 patients were randomized to rivastigmine, and 179 patients to placebo. Of the 362 patients given rivastigmine, 263 (73%) completed the study, compared with 147 patients (82%) given placebo [30]. Sixty‐two patients (17%) in the rivastigmine group discontinued due to adverse events, versus 14 patients (8%) in the placebo group. The most frequently occurring adverse events were nausea, which affected 29% of patients in the rivastigmine group and 11% of patients in the placebo group, and vomiting, reported by 17% of patients given rivastigmine and 2% of patients given placebo [30]. Emerging or worsening tremor was reported in 10% of patients in the rivastigmine group, compared with 4% in the placebo group, though this was mild and rarely led to discontinuation. A retrospective analysis of safety data from this trial reported that tremor was usually associated with dose titration and was generally transient, resolving with continued treatment [62]. There were 11 deaths in total, with significantly fewer deaths in the rivastigmine group (4 deaths) compared with the placebo group (7 deaths) (P < 0.05) [63].

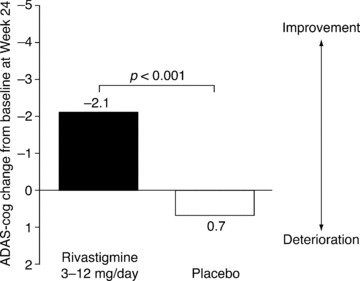

Statistically significant treatment differences in comparison with placebo were seen with rivastigmine on both primary efficacy variables [30]. On the ADAS‐cog, a significant treatment difference was seen in patients given rivastigmine compared with patients in the placebo group (P < 0.001) (Figure 3). Mean scores (±SD) indicated that patients in the rivastigmine group experienced an improvement in cognition of 2.1 points (±8.2) on the ADAS‐cog over 24 weeks, while patients on placebo deteriorated by 0.7 points (±7.5). If the deterioration on placebo seen here is typical of the rate of decline in the general PDD population, it suggests that treatment with rivastigmine can delay the worsening of PDD symptoms by an average of 1.5 years.

Figure 3.

Changes from baseline in ADAS‐cog scores at 24 weeks in patients with PDD in an RCT of rivastigmine (efficacy population*) [30]. *All randomized patients receiving at least one dose of study medication who were assessed at baseline and at least once after baseline.

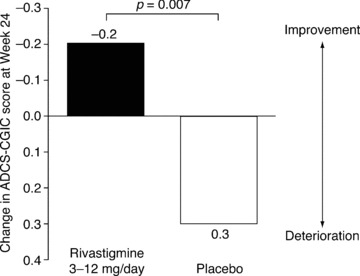

Likewise, on the ADCS‐CGIC, the mean change at Week 24 in the rivastigmine group indicated improvement, while that in the placebo group indicated deterioration (rivastigmine versus placebo, P= 0.007) (Figure 4) [30]. Analysis of outcomes in the seven response categories of the ADCS‐CGIC (marked, moderate, or minimal improvement; no change; marked, moderate, or minimal deterioration) showed that significantly more patients experienced improvement on rivastigmine than on placebo at Week 24 (40.8 vs. 29.7%, P= 0.02). Around a quarter of patients given rivastigmine experienced no change on the ADCS‐CGIC, and marked or moderate deterioration in symptoms was seen in 13.0% of patients given rivastigmine and 23.1% of patients given placebo. Significant benefits with rivastigmine versus placebo were also seen on all secondary efficacy outcomes: the ADCS‐ADL (P < 0.02), CDR (P= 0.009), D‐KEFS (P < 0.001), Ten Point Clock‐Drawing test (P= 0.02), MMSE (P < 0.03), and NPI (P < 0.02) [30].

Figure 4.

Changes at Week 24 in ADCS‐CGIC scores in patients with PDD in an RCT of rivastigmine (efficacy population*) [30]. *All randomized patients receiving at least one dose of study medication assessed at baseline and at least once after baseline.

Additional analyses showed that significant improvements with rivastigmine in comparison with placebo were present on all four composite measures of the CDR. These measures represent two domains that are characteristically impaired in other forms of dementia (Power of Attention, P < 0.01 vs. placebo at Week 24; and Continuity of Attention, P= 0.0001 vs. placebo at Week 24), and two domains that are specifically affected in PDD (Cognitive Reaction Time, P < 0.0001 vs. placebo at Week 24; and Reaction Time Variability, P < 0.001 vs. placebo at Week 24) [66].

A prospective additional analysis of the rivastigmine study data, described in the original study protocol, compared the subpopulations of PDD patients who reported suffering from hallucinations at baseline with those who reported no hallucinations at baseline and found that rivastigmine provided benefits in both groups of patients [67]. However, rivastigmine–placebo treatment differences tended to be larger in hallucinators than nonhallucinators, and patients with hallucinations tended to experience a more rapid decline on placebo in comparison with nonhallucinating patients [67].

Patients completing the 24‐week double‐blind rivastigmine study [30] were eligible to enter a 24‐week open‐label extension [36], in which all patients (irrespective of their double‐blind treatment) who chose to continue (n = 334) were given 3–12 mg/day rivastigmine. On switching to active treatment in the extension study, patients who had previously received placebo in the double‐blind phase experienced treatment benefits similar to those previously seen in the double‐blind rivastigmine group. The treatment effects seen in patients receiving rivastigmine, during the double‐blind study and open‐label extension, were largely maintained for the full 48‐week period. The profile of adverse events seen in the open‐label extension was similar to that of the original double‐blind trial.

Donepezil

While full publication of the results of the RCT of donepezil in patients with PDD by Dubois et al. is pending, preliminary findings were presented in 2007 at the Eighth International Conference on Alzheimer's and PDs in Salzburg, Austria [31]. Because of the clinical importance of this large RCT, the results as presented at this International Congress will be discussed here, although that poster was not subject to formal peer‐review. However, due to the nature of the poster presentation, the amount of information provided is limited, and a detailed review of the study is not possible until the results are published in a peer‐reviewed journal.

Like the rivastigmine study [30], the donepezil study was a 24‐week, randomized, multicenter, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial [31]. Primary efficacy outcomes were the ADAS‐cog and the Clinician's Interview‐Based Impression of Change plus caregiver input (CIBIC‐plus). Secondary efficacy outcomes included the MMSE, the Brief Test of Attention (BTA) [68], the D‐KEFS, the Disability Assessment for Dementia scale (DAD) [69], and the NPI.

A total of 550 patients with PDD were randomized to 5 mg donepezil (n = 195), 10 mg donepezil (n = 182), or placebo (n = 173). Mean age was 72 years, and mean baseline MMSE was 21/30. Sixty‐eight percent of the patients were male. The number of patients completing the full 24 weeks of the study was not provided, nor was the number of deaths occurring during the study. The most common adverse events were nausea (occurring in 21, 17, and 7% of patients given 10 mg donepezil, 5 mg donepezil, and placebo, respectively) and Parkinsonian side effects (10, 11, and 7%, respectively).

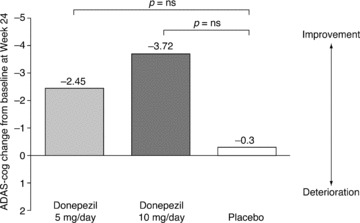

Results on the CIBIC‐plus for the group given 10 mg donepezil, but not the group given 5 mg donepezil, were reported to be statistically superior compared with placebo (P‐values not provided). However, while there was a trend toward improvement on the ADAS‐cog for both 5 mg and 10 mg donepezil at 24 weeks, the treatment difference versus placebo was not significant for either dose (Figure 5). Mean scores (±SD) indicated that patients in the 5 mg donepezil group experienced an improvement of 2.45 points (±5.28) on the ADAS‐cog over 24 weeks, while patients in the 10 mg donepezil group improved by 3.72 points (±7.05), and those on placebo improved by 0.3 points (±6.49). Significant treatment differences were seen on secondary measures including the MMSE (P < 0.001), BTA (P < 0.01), and D‐KEFS (P < 0.01). No significant differences were observed on measures of activities of daily living (DAD), or behavior (NPI).

Figure 5.

Changes from baseline in ADAS‐cog scores at 24 weeks in patients with PDD in an RCT of donepezil (ITT‐LOCF population) [31].

Discussion

The data reviewed here support the suggestion that ChEIs may be efficacious in the treatment of PDD. The collection of open studies and case series described in this review consistently observed discernable treatment benefits (albeit on varying outcome measures) relative to baseline values for all three ChEIs. These open studies do not make any attempt to control against placebo effects, but the observations they make are corroborated by the evidence provided from RCTs. However, as Figure 2 shows, the results of small RCTs, open studies, and case series are extremely variable, demonstrating the need for robust evidence‐based medicine in the form of large, randomized, placebo‐controlled trials.

The two large RCTs of rivastigmine and donepezil [30, 31] and the three small RCTs of donepezil [34, 35, 46] that have been carried out to date all report at least one outcome with a statistically significant treatment difference versus placebo, though not all donepezil studies reached primary endpoints. Rivastigmine is now widely approved by regulatory authorities for the symptomatic treatment of mild‐to‐moderate PDD, on the basis of the positive results observed in the RCT of this ChEI. Donepezil and galantamine are not approved for this indication. It should be noted that the primary endpoints in the large RCTs reviewed here are primarily indicated for research in AD, not PDD. However, although the ADAS‐cog – a primary endpoint in both the large RCTs of donepezil and rivastigmine – was originally designed for use in patients with AD, its validity and reliability in the assessment of patients with PD has been demonstrated [70].

Most recent American Academy of Neurology (AAN) guidelines on the treatment of depression, psychosis, and dementia in PD recommend that both rivastigmine and donepezil should be considered for the treatment of PDD [71]. This advice was based on a review of the results of the large RCT of rivastigmine by Emre [30] and two small RCTs of donepezil [34, 35], despite one of the latter studies failing to see a significant treatment difference on its primary outcome measure [35]. The larger RCT of donepezil was not available for the AAN panel's review at the time of developing their guidelines. If all currently available evidence is considered, including the recent large RCT of donepezil in PDD [31], the most robust demonstration of treatment benefits without the risk of worsening Parkinsonian symptoms is seen with rivastigmine.

A marked or moderate deterioration on the ADCS‐CGIC was reported in 13% of patients on the treatment arm in the large RCT of rivastigmine [30]. It is possible that some of the patients experiencing decline on rivastigmine were those who were unable to tolerate the recommended target dose of 6–12 mg/day. At 24 weeks, 23.5% of patients in the rivastigmine group were receiving less than the target dose, with 2 patients (0.6%) on less than 3 mg/day. A transdermal patch formulation of rivastigmine, now approved in many countries for the treatment of PDD, may make it easier for patients to titrate to higher doses due to its improved tolerability profile compared with capsules [72]. However, this formulation was not available at the time of the study.

There are several reasons why the large RCT of rivastigmine in PDD patients may have proved more successful in terms of meeting primary efficacy outcomes defined in its trial design, compared with the large RCT of donepezil. Firstly, differences in demographics between the patient populations included in these two trials may have affected the relative success of these studies. For example, the patients included in the RCT of donepezil had an average baseline MMSE two points higher than that of the patients in the rivastigmine RCT. Secondly, there may have been differences in trial design that affected statistical certainty. On the other hand, mean group differences in change on the ADAS‐cog were rather similar between the two large RCTs, and it is possible that the lack of statistical significance in the donepezil study is due to reduced statistical power since three groups were compared. However, it is difficult to consider such differences, due to the limited availability of information about the donepezil study, which has only been presented in poster format to date.

Differences between the therapeutic agents themselves may also have contributed to the outcomes of the studies. In PDD, the pathology of the disease predominantly affects frontal regions of the brain. Interestingly, butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) appears to be the predominant cholinesterase in many key regions affected in PDD, and it has been postulated that BuChE inhibition might be particularly important in this type of dementia [73]. It could be hypothesized that inhibitors of BuChE and acetylcholinesterase (AChE), such as rivastigmine, might have potential for added therapeutic effects, compared with AChE‐selective inhibitors.

Several studies provided evidence for a reduction in, or elimination of, hallucinations upon treatment with ChEIs. These observations add further weight to claims that ChEIs are more appropriate for the treatment of behavioral and psychotic symptoms in patients with PDD and other dementias than the atypical antipsychotics that are still commonly used. ChEI therapy may provide effective treatment of hallucinations in PDD, without the increased risks of extrapyramidal Parkinsonian features, stroke, and mortality associated with antipsychotic use in the elderly [74, 75]. However, there are no studies yet demonstrating that ChEIs can improve psychotic symptoms in PDD patients selected for having such symptoms at baseline. Hallucinations may also be a clinical marker for greater underlying cholinergic deficits [76], which may explain recent findings suggesting that PDD patients with hallucinations receive increased benefits from ChEI therapy on measures of cognition, activities of daily living, and behavior, in comparison with patients not suffering from hallucinations [67]. Patients with hallucinations at baseline tend to experience more rapid cognitive decline on placebo, leading to greater rivastigmine versus placebo treatment effects. In post hoc analyses, rivastigmine has also been associated with greater treatment benefits in other specific subgroups of patients with dementia. Such subgroups include PDD patients with elevated levels of plasma homocysteine in comparison with patients with normal or low levels [77], and female AD patients homozygous for the BuChE wild‐type genotype compared with males or females with the BuChE‐K variant allele and males homozygous for the BuChE wild type [78]. To our knowledge, no equivalent evidence has been published to date for donepezil or galantamine.

While this review focused on the efficacy of ChEIs in PDD, trial data with rivastigmine in PDD patients for up to 48 weeks suggest that this agent is well tolerated with a favorable safety profile [36]. No unexpected safety issues arose in this population. In fact, rivastigmine was associated with significantly fewer deaths than placebo in the RCT [30]. In summary, ChEIs have shown beneficial effects in the treatment of PDD. Both donepezil and rivastigmine have been evaluated in large RCTs, although full data are in the public domain for the rivastigmine study only. Regulatory approval of rivastigmine for PDD was based on those data. Until the full results of the donepezil study are published, the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of donepezil in patients with PDD remain to be confirmed.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to, reviewed, and approved this manuscript. The decision to submit this article to peer review, for publication, was reached by consensus among all of the authors.

Disclosures

TVL has received consultancy fees and speaker fees from Novartis. PPDD has no conflicts of interest to disclose. DA has received research support from H Lundbeck and Merck‐Serono, and honoraria from H Lundbeck, Novartis, and GE Healthcare. PB has received consultancy fees and speaker fees from Novartis. JEG has received research support from and had a license agreement with Novartis.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Alpha‐Plus Medical Communications Ltd (UK) provided editorial assistance with the production of the manuscript. This assistance was sponsored by Novartis Pharma AG.

References

- 1. Jankovic J. Parkinson's disease: Clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hirtz D, Thurman DJ, Gwinn‐Hardy K, Mohamed M, Chaudhuri AR, Zalutsky R. How common are the “common” neurologic disorders? Neurology 2007;68:326–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Galvin JE, Pollack J, Morris JC. Clinical phenotype of Parkinson disease dementia. Neurology 2006;67:1605–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levy G, Schupf N, Tang MX, et al Combined effect of age and severity on the risk of dementia in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol 2002;51:722–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aarsland D, Zaccai J, Brayne C. A systematic review of prevalence studies of dementia in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2005;20:1255–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buter TC, Van Den Hout A, Matthews FE, Larsen JP, Brayne C, Aarsland D. Dementia and survival in Parkinson disease: A 12‐year population study. Neurology 2008;70:1017–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aarsland D, Kurz MW. The epidemiology of dementia associated with Parkinson disease. J Neurol Sci 2009;289:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Emre M, Cummings JL, Lane RM. Rivastigmine in dementia associated with Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease: Similarities and differences. J Alzheimers Dis 2007;11:509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dubois B, Pillon B. Cognitive deficits in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol 1997;244:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aarsland D, Ballard CG, Halliday G. Are Parkinson's disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies the same entity? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2004;17:137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aarsland D, Ballard C, Larsen JP, McKeith I. A comparative study of psychiatric symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease with and without dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:528–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lauterbach EC. The neuropsychiatry of Parkinson's disease and related disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2004;27:801–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Galvin JE. Cognitive change in Parkinson disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2006;20:302–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kitayama M, Wada‐Isoe K, Nakaso K, Irizawa Y, Nakashima K. Clinical evaluation of Parkinson's disease dementia: Association with aging and visual hallucination. Acta Neurol Scand 2007;116:190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harding AJ, Broe GA, Halliday GM. Visual hallucinations in Lewy body disease relate to Lewy bodies in the temporal lobe. Brain 2002;125:391–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williams DR, Lees AJ. Visual hallucinations in the diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: A retrospective autopsy study. Lancet Neurol 2005;4:605–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huber SJ, Paulson GW, Shuttleworth EC. Relationship of motor symptoms, intellectual impairment, and depression in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51:855–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reid WG, Hely MA, Morris JG, Broe GA, Adena M, Sullivan DJ, Williamson PM. A longitudinal of Parkinson's disease: Clinical and neuropsychological correlates of dementia. J Clin Neurosci 1996;3:327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schrag A, Jahanshahi M, Quinn N. How does Parkinson's disease affect quality of life? A comparison with quality of life in the general population. Mov Disord 2000;15:1112–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aarsland D, Larsen JP, Karlsen K, Lim NG, Tandberg E. Mental symptoms in Parkinson's disease are important contributors to caregiver distress. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999;14:866–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aarsland D, Larsen JP, Tandberg E, Laake K. Predictors of nursing home placement in Parkinson's disease: A population‐based, prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:938–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Braak H, Griffing K, Braak E. Neuroanatomy of Alzheimer's disease. Alz Res 1997;3:235–247. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Forno LS. Neuropathology of Parkinson's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1996;55:259–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2003;24:197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hornykiewicz O. Basic research on dopamine in Parkinson's disease and the discovery of the nigrostriatal dopamine pathway: The view of an eyewitness. Neurodegener Dis 2008;5:114–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perry EK, Curtis M, Dick DJ, et al Cholinergic correlates of cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease: Comparisons with Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985;48:413–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Perry EK, Irving D, Kerwin JM, et al Cholinergic transmitter and neurotrophic activities in Lewy body dementia: Similarity to Parkinson's and distinction from Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1993;7:69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bohnen NI, Kaufer DI, Ivanco LS, et al Cortical cholinergic function is more severely affected in parkinsonian dementia than in Alzheimer disease: An in vivo positron emission tomographic study. Arch Neurol 2003;60:1745–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hutchinson M, Fazzini E. Cholinesterase inhibition in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;61:324–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Emre M, Aarsland D, Albanese A, et al Rivastigmine for dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2509–2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dubois B, Tolosa E, Kulisevsky J, et al Efficacy and safety of donepezil in the treatment of Parkinson's disease patients with dementia. Poster presented at 8th International Conference on Alzheimer's and Parkinson's Diseases, Salzburg, Austria, 2007.

- 32. Aarsland D, Mosimann UP, McKeith IG. Role of cholinesterase inhibitors in Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2004;17:164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maidment I, Fox C, Boustani M. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Parkinson's disease dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006.doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004747.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aarsland D, Laake K, Larsen JP, Janvin C. Donepezil for cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease: A randomised controlled study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;72:708–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ravina B, Putt M, Siderowf A, et al Donepezil for dementia in Parkinson's disease: A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, crossover study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:934–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Poewe W, Wolters E, Emre M, et al; EXPRESS Investigators. Long‐term benefits of rivastigmine in dementia associated with Parkinson's disease: An active treatment extension study. Mov Disord 2006;21:456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dujardin K, Devos D, Duhem S, et al Utility of the Mattis dementia rating scale to assess the efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol 2006;253:1154–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bullock R, Cameron A. Rivastigmine for the treatment of dementia and visual hallucinations associated with Parkinson's disease: A case series. Curr Med Res Opin 2002;18:258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fabbrini G, Barbanti P, Aurilia C, Pauletti C, Lenzi GL, Meco G. Donepezil in the treatment of hallucinations and delusions in Parkinson's disease. Neurol Sci 2002;23:41–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kurita A, Ochiai Y, Kono Y, Suzuki M, Inoue K. The beneficial effect of donepezil on visual hallucinations in three patients with Parkinson's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2003;16:184–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reading PJ, Luce AK, McKeith IG. Rivastigmine in the treatment of parkinsonian psychosis and cognitive impairment: Preliminary findings from an open trial. Mov Disord 2001;16:1171–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini‐mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1984;141:1356–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg‐Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994;44:2308–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fahn S, Elton R; Members of the UPDRS Development Committee . Unified Parkinson's disease rating scale In: Fahn S, Marsden C, Calne D, Goldstein M, editors. Recent developments in Parkinson's disease. Florham Park , NJ : MacMillan Healthcare Information, 1987;153–164. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Leroi I, Brandt J, Reich SG, Lyketsos CG, Grill S, Thompson R, Marsh L. Randomized placebo‐controlled trial of donepezil in cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;19:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Minett TS, Thomas A, Wilkinson LM, et al What happens when donepezil is suddenly withdrawn? An open label trial in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;18:988–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thomas AJ, Burn DJ, Rowan EN, et al A comparison of the efficacy of donepezil in Parkinson's disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:938–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Muller T, Welnic J, Fuchs G, Baas H, Ebersbach G, Reichmann H. The DONPAD‐study: Treatment of dementia in patients with Parkinson's disease with donepezil. J Neural Transm Suppl 2006;71:27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bergman J, Lerner V. Successful use of donepezil for the treatment of psychotic symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease. Clin Neuropharmacol 2002;25:107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Aarsland D, Hutchinson M, Larsen JP. Cognitive, psychiatric and motor response to galantamine in Parkinson's disease with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;18:937–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Litvinenko IV, Odinak MM, Mogil’naya VI, Emelin AY. Efficacy and safety of galantamine (reminyl) for dementia in patients with Parkinson's disease (an open controlled trial). Neurosci Behav Physiol 2008;38:937–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Giladi N, Shabtai H, Gurevich T, Benbunan B, Anca M, Korczyn AD. Rivastigmine (Exelon) for dementia in patients with Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 2003;108:368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gibb WR, Lees AJ. The relevance of the Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51:745–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Daniel SE, Lees AJ. Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank, London: Overview and research. J Neural Transm Suppl 1993;39:165–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders , 4th ed Washington , DC : American Psychiatric Association, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schneider LS, Olin JT, Doody RS, et al Validity and reliability of the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study‐Clinical Global Impression of Change. The Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997;11(Suppl 2):S22–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Galasko D, Bennett D, Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas R, Grundman M, Ferris S. An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease. The Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997;11(Suppl 2):S33–S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Simpson PM, Surmon DJ, Wesnes KA, Wilcock GK. The cognitive drug research computerized assessment system for demented patients: A validation study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1991;6:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Delis D, Kaplan E, Kramer J. Delis‐Kaplan executive function system. San Antonio , TX : Psychological Corporation, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Manos PJ, Wu R. The ten point clock test: A quick screen and grading method for cognitive impairment in medical and surgical patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 1994;24:229–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Oertel W, Poewe W, Wolters E, et al Effects of rivastigmine on tremor and other motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease dementia: A retrospective analysis of a double‐blind trial and an open‐label extension. Drug Saf 2008;31:79–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ballard C, Lane R, Barone P, Ferrara R, Tekin S. Cardiac safety of rivastigmine in Lewy body and Parkinson's disease dementias. Int J Clin Pract 2006;60:639–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rowan E, McKeith IG, Saxby BK, et al Effects of donepezil on central processing speed and attentional measures in Parkinson's disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2007;23:161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Werber EA, Rabey JM. The beneficial effect of cholinesterase inhibitors on patients suffering from Parkinson's disease and dementia. J Neural Transm 2001;108:1319–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wesnes KA, McKeith I, Edgar C, Emre M, Lane R. Benefits of rivastigmine on attention in dementia associated with Parkinson disease. Neurology 2005;65:1654–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Burn D, Emre M, McKeith I, De Deyn PP, Aarsland D, Hsu C, Lane R. Effects of rivastigmine in patients with and without visual hallucinations in dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2006;21:1899–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Schretlen D, Bobholz JH, Brandt J. Development and psychometric properties of the brief test of attention. Clin Neuropsychol 1996;10:80–89. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gelinas I, Gauthier L, McIntyre M, Gauthier S. Development of a functional measure for persons with Alzheimer's disease: The disability assessment for dementia. Am J Occup Ther 1999;53:471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Harvey PD, Ferris SH, Cummings JL, Wesnes KA, Hsu C, Lane RM, Tekin S. Evaluation of dementia rating scales in Parkinson's disease dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2010;25:142–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Miyasaki JM, Shannon K, Voon V, et al Practice parameter: Evaluation and treatment of depression, psychosis, and dementia in Parkinson disease (an evidence‐based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2006;66:996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Winblad B, Cummings J, Andreasen N, et al A six‐month double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled study of a transdermal patch in Alzheimer's disease: Rivastigmine patch versus capsule. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;22:456–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bullock R, Lane R. Executive dyscontrol in dementia, with emphasis on subcortical pathology and the role of butyrylcholinesterase. Curr Alzheimer Res 2007;4:277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Caligiuri MR, Jeste DV, Lacro JP. Antipsychotic‐induced movement disorders in the elderly: Epidemiology and treatment recommendations. Drugs Aging 2000;17:363–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bullock R. Treatment of behavioural and psychiatric symptoms in dementia: Implications of recent safety warnings. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Perry EK, Marshall E, Kerwin J, Smith CJ, Jabeen S, Cheng AV, Perry RH. Evidence of a monoaminergic‐cholinergic imbalance related to visual hallucinations in Lewy body dementia. J Neurochem 1990;55:1454–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Barone P, Burn DJ, van Laar T, Hsu C, Poewe W, Lane RM. Rivastigmine versus placebo in hyperhomo‐cysteinemic Parkinson's disease dementia patients. Mov Disord 2008;23:1532–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ferris S, Nordberg A, Soininen H, Darreh‐Shori T, Lane R. Progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease: Effects of sex, butyrylcholinesterase genotype, and rivastigmine treatment. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2009;19:635–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]