New and efficient sequencing technologies are constantly identifying novel gene variants in patients that may be the genetic cause of renal diseases. Recent studies show that, even for adult patients with CKD, monogenic causes can be detected in around 10% of patients.1 Novel causative genes and their mutations can, on one hand, provide a diagnosis for patients with renal diseases of unknown etiology and, on the other hand, provide new angles in the understanding of renal disease pathogenesis. Given the wealth of neutral polymorphisms in our genome, one of the main challenges is to evaluate pathogenicity of the identified genetic variants. In many cases, functional validation by experimental studies is indispensable, but because the kidney is a very complex organ, this is not a trivial task. Although the use of mice is not always justified as the experimental model, in particular because it can be quite slow and expensive, cell culture models lack their native environments. Some cell types, such as podocytes, for example, cannot maintain their complex cytoarchitecture, including slit diaphragms, in cell culture. Thus, there is a clear need for alternative in vivo models to functionally validate candidate genes arising from human genetic studies.

In this issue of the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, Zhao et al.2 use Drosophila nephrocytes to study two novel mutations in the gene NUP160. NUP160 encodes for nucleoprotein 160 kDa, which is required within the Nup107–160 complex in early stages of nuclear pore complex assembly. Like in other nucleoprotein-encoding genes (e.g., NUP93, NUP107, and NUP205), mutations in NUP160 have recently been shown to cause steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS).3 SRNS is characterized by the disruption of the glomerular filtration barrier, leading to massive proteinuria and hypoalbuminemia. So far, >50 genes have been identified with mutations that cause SRNS, many of which are required for podocyte-specific functions. In several instances, Drosophila nephrocytes have been used for functional validation of candidate genes.4–6

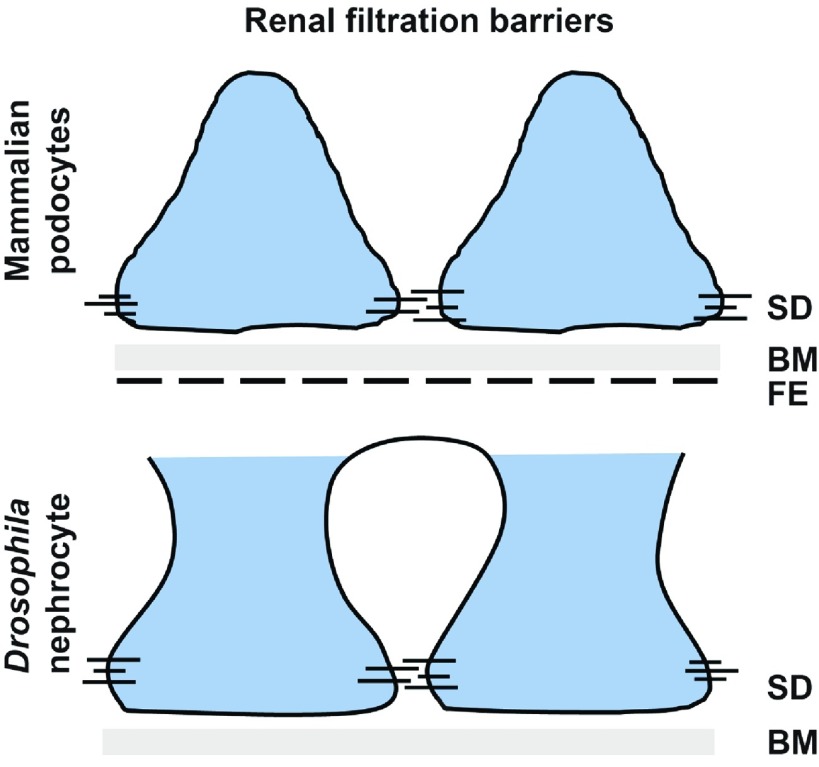

What are Drosophila nephrocytes exactly, and why can they be useful for functional validation? Similar to vertebrates, the fly kidney consists of a proximal part and a distal part. The proximal part is represented by the nephrocytes that perform glomerulus-like filtration of the surrounding hemolymph and proximal tubule–like endocytosis of the filtrated substances. The distal tubule function, however, is handled by the Malpighian tubules, which are transporting water, ions, and solutes for osmoregulation and ion homeostasis. There are two populations of nephrocytes: garland and pericardial nephrocytes. The former surround the esophagus close to the proventriculus, like a necklace, whereas the latter are arranged in rows of cells on both sides of the heart tube. For their differentiation, the transcription factor Klf15 is involved,7 which is also required for podocyte differentiation. For the filtration process, nephrocytes also show important similarities with the mammalian glomerular filtration barrier8: although the fenestrated endothelium is lacking, the first barrier is the basement membrane, which mainly consists of collagen IV9; the second barrier is the nephrocyte slit diaphragm (Figure 1). Here, Kirre and Sns (the orthologs of Neph1 and Nephrin) interact in an heterophilic manner to provide stability and function as a size-dependent filter, similar to the mammalian slit diaphragm.10 Upon filtration, the filtrate will enter labyrinthine channels that are formed by plasma membrane invaginations sealed by the slit diaphragms. Analogous to the mammalian proximal tubules, receptors, such as cubilin and amnionless, are responsible for protein uptake from the invagination membrane.11,12

Figure 1.

Comparison of mammalian and Drosophila renal filtration barriers. The scheme illustrates the similarities and differences between mammalian podocytes and Drosophila nephrocytes. Both systems possess the basement membrane (BM) and the slit diaphragm (SD), whereas the fenestrated endothelium (FE) is absent in nephrocytes.

One big advantage of using nephrocytes in kidney research is that they can easily be dissected without disturbing the slit diaphragm integrity. Isolated nephrocytes can be subjected to filtration and uptake studies using fluorescently-tagged tracer or subjected to ultrastructural analyses. Flies can also be fed with chemical compounds before dissection to test therapeutic strategies. This can be combined with sophisticated genetic manipulation, for which Drosophila is famous. Especially in recent years, the fly community has witnessed an enormous growth in resources, including several stock center collections of transgenic and mutant flies. With the help of such publicly available fly stocks, it was recently shown that silencing of one half of the known SRNS genes produced nephrocyte phenotypes.9 As shown by Zhao et al.,2 flies can also be humanized by knocking down the fly gene and then reintroducing the human gene using the cell-specific UAS-GAL4 system. For more physiologic settings, the endogenous promoter of the gene of interest can also be exploited, or the entire fly gene can be replaced by the human gene using CRISPR/Cas9-guided homologous recombination.

Apart from these benefits, there are also some differences that should be taken into account. The main difference to the mammalian proximal nephron is that there is no filtrate that is passed on to more downstream tubular segments for additional modification and final excretion out of the body. Instead, the nephrocytes store or metabolize the hemolymph waste and are not physically connected to the Malpighian tubules. Therefore, nephrocytes are considered as a storage kidney and not as an excretory organ. Whether the nephrocytes can also secrete back into the hemolymph (for example, after metabolization) remains to be investigated. Other obvious differences to podocytes are that nephrocytes are unipolar single cells that form intracellular and not intercellular slit diaphragms. Moreover, filtration is most likely facilitated by oscillating fluctuations caused by the contracting heart (for pericardial nephrocytes) and the peristaltic proventriculus (for garland nephrocytes) and not facilitated by a high-BP system, like in the glomerulus.

The demand is increasing for rapid functional validation of genes variants derived from the sequencing outputs for renal genetic diseases. Drosophila nephrocytes have proven to be an easy to use alternative for such efforts. As with any other existing model system, nephrocytes do not provide a complete solution. Yet, the effortless ex vivo analysis of nephrocytes and the structural and functional similarity to podocytes and proximal tubular cells as well as the plethora of powerful genetic tools from the Drosophila community can offer an intermediate platform that bridges the experimental gaps to other experimental models.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Work in the Simons lab is supported by the ATIP-Avenir program as well as funding by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) under the “Investissements d'avenir” program (ANR-10-IAHU-01) and the NEPHROFLY (ANR-14-ACHN-0013) grant.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related article, “Mutations in NUP160 Are Implicated in Steroid-Resistant Nephrotic Syndrome,” on pages 840–853.

References

- 1.Groopman EE, Marasa M, Cameron-Christie S, Petrovski S, Aggarwal VS, Milo-Rasouly H, et al. : Diagnostic utility of exome sequencing for kidney disease. N Engl J Med 380: 142–151, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao F, Zhu J-Y, Richman A, Fu Y, Huang W, Chen N, et al. : J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 840–853, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun DA, Lovric S, Schapiro D, Schneider R, Marquez J, Asif M, et al. : Mutations in multiple components of the nuclear pore complex cause nephrotic syndrome. J Clin Invest 128: 4313–4328, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermle T, Schneider R, Schapiro D, Braun DA, van der Ven AT, Warejko JK, et al. : GAPVD1 and ANKFY1 mutations implicate RAB5 regulation in nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2123–2138, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lovric S, Goncalves S, Gee HY, Oskouian B, Srinivas H, Choi WI, et al. : Mutations in sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase cause nephrosis with ichthyosis and adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Invest 127: 912–928, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonçalves S, Patat J, Guida MC, Lachaussée N, Arrondel C, Helmstädter M, et al. : A homozygous KAT2B variant modulates the clinical phenotype of ADD3 deficiency in humans and flies. PLoS Genet 14: e1007386, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivy JR, Drechsler M, Catterson JH, Bodmer R, Ocorr K, Paululat A, et al. : Klf15 is critical for the development and differentiation of Drosophila nephrocytes. PLoS One 10: e0134620, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weavers H, Prieto-Sánchez S, Grawe F, Garcia-López A, Artero R, Wilsch-Bräuninger M, et al. : The insect nephrocyte is a podocyte-like cell with a filtration slit diaphragm. Nature 457: 322–326, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermle T, Braun DA, Helmstädter M, Huber TB, Hildebrandt F: Modeling monogenic human nephrotic syndrome in the Drosophila garland cell nephrocyte. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1521–1533, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helmstädter M, Simons M: Using Drosophila nephrocytes in genetic kidney disease. Cell Tissue Res 369: 119–126, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang F, Zhao Y, Chao Y, Muir K, Han Z: Cubilin and amnionless mediate protein reabsorption in Drosophila nephrocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 209–216, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gleixner EM, Canaud G, Hermle T, Guida MC, Kretz O, Helmstädter M, et al. : V-ATPase/mTOR signaling regulates megalin-mediated apical endocytosis. Cell Rep 8: 10–19, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]