Abstract

Introduction: Rapid onset of symptomatic improvement is a desirable characteristic of new generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) treatments. A validated rating scale is needed to assess GAD symptoms during the first days of treatment.

Aims: To provide clinical data to support the validation of the Daily Assessment of Symptoms‐Anxiety (DAS‐A), a new instrument to assess onset of symptomatic improvement in GAD.

Methods: We assessed the ability of the DAS‐A to detect onset of symptomatic improvement during the first week of therapy in 169 GAD patients randomized to paroxetine 20 mg/day, lorazepam 4.5 mg/day, or placebo for 4 weeks.

Results: On the primary outcome measure, average change from baseline over the first 6 days of DAS‐A assessments, lorazepam (−14.5 ± 1.8 [LS mean, SE]; P= 0.006 vs. placebo) showed a significant improvement versus placebo (−7.85 ± 1.7), whereas paroxetine (−8.3 ± 1.7; P= 0.83 vs. placebo) did not. Lorazepam produced a significant treatment effect on the DAS‐A at 24 h (P= 0.0004), whereas paroxetine did not (P= 0.5666). Both active drugs produced statistically significant improvement versus placebo on the DAS‐A total change score (last‐observation carried forward method; LOCF, endpoint). On the DAS‐A total change score (observed cases analysis), lorazepam produced statistically significant improvement versus placebo at weeks 1, 2, and 4 (P < 0.05; no week 3 visit), whereas paroxetine, separated from placebo at weeks 2 and 4 (P < 0.05). Both active drugs produced results on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM‐A) at weeks 1 through 4 that were similar to those found on the DAS‐A.

Conclusions: These data indicate that the DAS‐A can detect symptomatic improvement in GAD patients treated with lorazepam during the first week of treatment, and, in a secondary analysis, as early as 24 h.

Keywords: Anxiety, Benzodiazepine, Clinical trial, Generalized anxiety disorder, Measurement, Onset

Introduction

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a common and disabling mental illness. Recent estimates of lifetime prevalence range from 3% to 6%[1, 2]. The disability associated with GAD has been described to be as impairing as that of depression and chronic somatic illnesses [3, 4, 5], associated with increased utilization of health‐care services [4, 6] and resulted in a reduced quality of life [1, 7].

Rapid onset of symptomatic improvement is a desirable characteristic of new treatments for GAD. Rapid symptom relief should more quickly relieve the suffering and distress associated with GAD symptoms and may lead to faster functional improvements, increased compliance, decreased health‐care utilization, and improved quality of life.

Benzodiazepines are known to be effective for the treatment of GAD, and have a rapid onset of action in treating anxiety, however, they also have an increased potential for abuse, physical dependence, psychomotor impairment, and risk of injury. Benzodiazepine treatment effects are evident after 1 week when measured by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM‐A) in GAD [8], and within hours when assessed by self‐report visual analog scales and other self‐report measures in models of anticipatory anxiety [9, 10] and in models of panic disorder [11]. Other pharmacotherapies, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as paroxetine and fluoxetine, the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors venlafaxine and duloxetine, and the 5HT1a partial agonist buspirone, are also effective for GAD. These agents, however, have a slower onset of activity, generally within 2–4 weeks [12, 13], depending upon how onset is defined and measured.

Most GAD studies use the HAM‐A [14] as the primary clinical efficacy endpoint. The HAM‐A has acceptable reliability and validity at 1 week, and is accepted by regulatory agencies as a method to assess GAD treatment response. The HAM‐A, however, has not been validated for use at less than 1 week, requires an office visit, and contains items that are no longer consistent with the current diagnostic definition of GAD. Given the practical limitations of the HAM‐A, we have developed a new patient self‐report instrument (the Daily Assessment of Symptoms‐Anxiety [DAS‐A]) [15] to allow for the daily assessment of the symptoms of GAD during the first week of therapy.

In this study, we tested the 15‐item DAS‐A for its ability to detect the early treatment effects of lorazepam (1.5 mg TID), a benzodiazepine, and the later treatment effects of paroxetine (20 mg QD), a SSRI, in improving the symptoms of GAD.

Methods

This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practices, and the standard quality assurance procedures used for Pfizer‐sponsored clinical trials. The protocol was approved for each site by an institutional review board. Each patient received an explanation of the study before signing an instrument of written informed consent. Consent was obtained prior to any study‐related activities.

DAS‐A

The development and initial validation of the DAS‐A followed rigorous and commonly accepted methods for the creation of patient‐reported instruments [16]. The items included in a preliminary version of the instrument were identified through a combination of literature review, interviews with clinical experts, consideration of the diagnostic coverage of GAD as defined by the DSM‐IV, and patient focus groups. After cognitive interviewing, which involved asking patients who had recently responded to an anxiolytic to comment on how they had interpreted items and chose responses as they completed a draft version of the DAS‐A, a set of 15 DAS‐A items were included in this clinical trial [15]. Items in the DAS‐A cover anxiety, worries, tension, irritability, as well as sleep and cognitive functioning (e.g., concentration, memory), corresponding to the symptoms that define GAD. Each item is scored on a 0–10 point scale and the DAS‐A total score is transformed to a 0–100 point scale where a higher total score indicates greater symptom severity. A copy of the DAS‐A used in this study is appended to this article (Fig. S1).

Study Design

The study was a double‐blind, randomized, multicenter, fixed‐dose, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group study using oral doses of lorazepam (1.5 mg TID), paroxetine (20 mg QD), and oral placebo. The study consisted of a 1‐week screening phase during which eligibility was determined, a 4‐week double‐blind treatment phase, and then a 5‐day double‐blind treatment phase, during which therapy was down‐titrated. The doses of paroxetine and lorazepam selected were standard doses for GAD, with lorazepam titrated (1 mg TID for the first 3 days) for tolerability. A placebo group was included in this study to test whether the DAS‐A was able to detect a treatment effect, and to allow for a comparison of the treatment effect seen on the DAS‐A with that detected by the HAM‐A.

Subjects Studied

The population was selected to be similar to that typically used in clinical trials intended to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of new GAD treatments in development. Males and females aged 18–65 with a DSM‐IV diagnosis of GAD (determined using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview [MINI] and confirmed by a psychiatrist) and no significant medical illness that would interfere with study participation were enrolled in the study. Subjects were also required to have a HAM‐A total score ≥20 at the screening and baseline visits, as well as a Raskin depression scale total score ≤7 and a Covi anxiety scale total score ≥9 at the screening visit in order to assure predominance of anxiety over depressive symptoms. Subjects were excluded from study participation if they had significant suicidal risk, had failed treatment with lorazepam or paroxetine in the past, required daily benzodiazepine use in the 3 months prior to study participation, or if they had most other concurrent DSM‐IV mental disorders, including major depressive disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, acute stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, dissociative disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, anorexia, bulimia, caffeine‐induced anxiety disorder, alcohol or substance abuse or dependence, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or antisocial or borderline personality disorder. Subjects with current or past diagnoses of schizophrenia, psychotic disorders, delerium, dementia, amnestic disorders, clinically significant cognitive disorders, bipolar or schizoaffective disorder, benzodiazepine abuse or dependence, or factitious disorder were also excluded. Subjects were required to have used no psychotropic medications for at least 2 weeks prior to the screening visit (4 weeks for fluoxetine). Concurrent use of other psychotropic medications during the study or psychotherapy (unless the psychotherapy was initiated at least 3 months prior to study participation and continued throughout the study) was not permitted.

Efficacy Measures

The mean change from baseline over the first 6 days of treatment assessment (study days 2 through 7) on the total score of the DAS‐A questionnaire was the primary efficacy parameter. Secondary efficacy outcomes included the following: mean change from baseline to end of treatment (week 4 of the double‐blind treatment phase) in the DAS‐A total score, the HAM‐A total score, the HAM‐A psychic and somatic subscales, and HAM‐A item 1 (anxiety item) using all available subjects and last observation carried forward for data missing at week 4; mean change from baseline to weeks 1, 2, 4 (end of treatment), and 5 (follow‐up visit) (using observed or available cases) in the HAM‐A total score and the DAS‐A total score; mean change from baseline to each daily time point (study days 2 through 7) on the DAS‐A total score. The HAM‐A was not measured at time points less than 1 week in this study because it has not been validated for a less than 1‐week lookback period. Other outcome measures included the Clinical Global Impression‐Change (CGIC) [17], the Clinical Global Impression‐Severity (CGIS) [17], the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (anxiety and depression subscales), the Quality of Life Employment Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q‐LES‐Q) [18], and the SF‐36 Health Survey, version 2 (SF‐36) [19].

Statistical Methods

For each of the continuous measures (DAS‐A, HAM‐A, HADS, Q‐LES‐Q, SF‐36, CGIS) endpoints were compared between drug and placebo treatment arms using an analysis of covariance model with treatment and center in the model as a fixed effect, and the corresponding score as baseline as covariate. All analyses were evaluated at α= 0.05 level (two‐sided) for each comparison, with no adjustments for multiple comparisons. It should be noted that because the many secondary analyses conducted in this study have not been corrected for multiple statistical comparisons, some of the statistically significant secondary results may represent Type I error (false positive) findings.

The intent‐to‐treat population, defined as all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study medication, was the primary population used in the efficacy analyses. For end of treatment (week 4) analyses, missing values were handled using the last‐observation carried forward method (LOCF). In the by‐week (observed cases) analyses, if a value was missing at the analyzed time point, data for that patient were excluded from the analysis of that time point. The observed cases analyses used all available subjects who had observable (nonmissing) responses on the outcome of interest at a particular time point, regardless of whether the subjects gave completed responses on that outcome at other time points.

The change scores presented in the article are least‐squares mean change from baseline (±standard errors [SE]) for the continuous variables, except for the primary DAS‐A analysis, which is given as least‐squares mean average change from baseline.

As categorical variables, the CGIC and the PGIC were analyzed using logistic regression, adjusting for center. Both the CGIC and the PGIC were scored from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse). In this study, responders on each were defined as subjects who scored 1 or 2 (much or very much improved) at end of treatment (week 4).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of the 237 subjects who were screened for the study, 169 were randomized to treatment and 115 (69%) completed the study, 39 (69%) of the placebo subjects, 41 (75%) of the paroxetine subjects, and 35 (64%) of the lorazepam subjects. The majority of the early terminations were due to lack of compliance (six subjects) in the parxetine group, adverse events (14 subjects) in the lorazepam group, and other unspecified causes (six subjects) in the placebo group. The majority of subjects enrolled were female (58%), Caucasian (73%), and 18–35 years old (57%; mean age = 36). The mean HAM‐A total score at randomization was approximately 24 (range 20–47), indicating moderate‐to‐severe anxiety symptoms. Demographic and clinical characteristics were well‐balanced across treatment groups, with the exception that there were slightly more females in the lorazepam group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Placebo N = 57 | Paroxetine N = 56 | Lorazepam N = 56 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male (n, %) | 26 (45.6) | 25 (44.6) | 20 (35.7) |

| Female (n, %) | 31 (54.4) | 31 (55.4) | 36 (64.3) |

| Race | |||

| White (n, %) | 42 (73.7) | 40 (71.4) | 41 (73.2) |

| Black (n, %) | 3 (5.3) | 3 (5.4) | 3 (5.4) |

| Hispanic (n, %) | 9 (15.8) | 6 (10.7) | 8 (14.3) |

| Other (n, %) | 3 (5.3) | 7 (12.5) | 4 (7.1) |

| Age in years (mean [SD]) | 35.0 (10.4) | 35.0 (12.7) | 38.3 (12.0) |

| DAS‐A score at baseline (mean [SD]) | 58.9 (13.1) | 56.6 (11.9) | 58.7 (12.3) |

| HAM‐A total score at baseline (mean [SD]) | 24.0 (4.9) | 23.5 (3.3) | 24.2 (3.6) |

| HAM‐A psychic subscale (mean [SD]) | 15.1 (2.0) | 14.6 (1.9) | 14.6 (1.8) |

| HAM‐A somatic subscale (mean [SD]) | 8.9 (4.0) | 9.0 (2.7) | 9.6 (3.0) |

| HADS‐A (mean [SD]) | 14.1 (3.1) | 13.2 (3.4) | 13.4 (2.6) |

| CGIS score at baseline (mean [SD]) | 4.25 (0.51) | 4.29 (0.50) | 4.29 (0.60) |

| HADS‐D (mean [SD]) | 9.7 (3.5) | 8.8 (3.6) | 9.5 (3.3) |

| QLES‐Q (mean [SD]) | 48.0 (10.0) | 47.9 (13.0) | 48.2 (14.9) |

| SF‐36‐MHS (mean [SD]) | 42.3 (15.4) | 45.1 (17.1) | 44.5 (14.4) |

Sensitivity of DAS‐A

For the primary outcome of mean change from baseline over the first 6 days of treatment assessments on the DAS‐A, lorazepam (−14.5 ± 1.8, LS mean average change from baseline ± SE; P= 0.006) showed significant improvement versus placebo (−7.8 ± 1.7), whereas paroxetine (−8.3 ± 1.7, P= 0.83) did not. Lorazepam (−12.7 ± 1.8, LS mean change from baseline ±SE; P= .0004) also showed a statistically significant difference from placebo (−3.8 ± 1.7) on the DAS‐A 24 h after the first dose of study medication, whereas paroxetine (−5.2 ± 1.8, P= 0.57) did not.

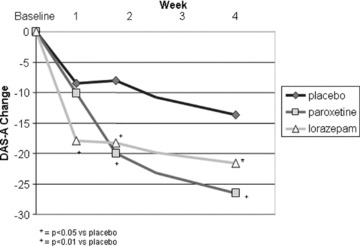

For the remainder of individual days during the first week of treatment, the DAS‐A showed a statistically significantly difference (P < 0.05) from placebo for lorazepam in change from baseline to days 3 (−15.0 ± 2.0, P= 0.0017) and 5 (−16.9 ± 2.3, P= 0.013) and trended towards significance at days 4 (−14.2 ± 2.1, P= 0.10), 6 (−15.0 ± 2.5, P= 0.12), and 7 (−15.2 ± 2.6, P= 0.099). In contrast, paroxetine was not significantly different from placebo on the DAS‐A on any of the individual days 3 through 7 (P values ranged from 0.58 to 0.82). Lorazepam (−20.7 ± 2.6, LS mean change from baseline, ± SE; P= 0.0032) and paroxetine (−22.1 ± 2.5, P= 0.0007) both showed a statistically significant difference from placebo at end of treatment on the DAS‐A. In the observed cases analyses, the DAS‐A detected significant improvement over placebo at weeks 1, 2, and 4 in the lorazepam group, and at weeks 2 and 4 in the paroxetine group (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

DAS‐A mean total score change from baseline, observed cases.

Standard Measures

Standard measures of treatment response were included in the study to assist in validating the initial version of the DAS‐A. In the LOCF analysis, the HAM‐A detected significant improvement in GAD symptoms in both the lorazepam (−11.95 ± 0.80, P < 0.0001; LS mean change from baseline to end of treatment ± SE) and paroxetine (−10.96 ± 0.78, P= 0.0009) groups relative to placebo (−7.42 ± 0.72). In the observed cases analysis, significant improvement versus placebo was evident on the HAM‐A for the lorazepam group at weeks 1, 2, and 4, and for the paroxetine group at weeks 2 and 4 (Fig. 2). Additional results for the HAM‐A and results for additional clinical measures are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2.

HAM‐A mean total score change from baseline, observed cases.

Table 2.

Treatment effects on secondary outcome measures (ITT, LOCF)1

| Measure/group | Placebo | Paroxetine | Lorazepam |

|---|---|---|---|

| HAM‐A psychic | −4.47 ± 0.48 | −6.91 ± 0.53** | −6.95 ± 0.54** |

| HAM‐A somatic | −2.98 ± 0.37 | −4.01 ± 0.40NS | −4.95 ± 0.42** |

| HAM‐A item 1 | −0.92 ± 0.11 | −1.50 ± 0.12** | −1.43 ± 0.12+ |

| HADS‐A | −3.39 ± 0.48 | −5.16 ± 0.52* | −4.58 ± 0.54NS |

| CGIC (# and % responders) | 11 (20.4%) | 21 (42.9%)+ | 26 (56.5%)++ |

| CGIS | −0.68 ± 0.12 | −1.25 ± 0.13** | −1.49 ± 0.13++ |

| PGIC (# and % responders) | 18 (33.3%) | 27 (56.3%)* | 23 (50.0%)NS |

| HADS‐D | −1.77 ± 0.47 | −2.60 ± 0.51NS | −2.27 ± 0.52NS |

| Q‐LES‐Q | 9.3 ± 2.2 | 16.5 ± 2.3* | 11.2 ± 2.4NS |

| SF‐36‐MHS | 10.9 ± 2.3 | 19.5 ± 2.5* | 13.5 ± 2.6NS |

1Mean change scores (SE) are results of an ANCOVA model (intention to treat and last observation carried forward), except where noted.

*P≤ 0.05; + P≤ 0.01; **P≤ 0.001; ++ P≤ 0.0001; NS, not significant (P > 0.05) for paroxetine or lorazepam vs. placebo.

Safety Outcomes

There were no unexpected or unusual adverse events or other safety results for lorazepam or paroxetine in this study. The most common adverse events in subjects in the lorazepam group were somnolence (55% of subjects), dizziness (23%), incoordination (13%), nausea (11%), and diarrhea (11%). The most common adverse events in subjects in the paroxetine group were somnolence (29%), nausea (18%), and dizziness (16%).

Discussion

The evaluation of new pharmacotherapies for GAD requires sensitive and clinically responsive measures of treatment outcome. This method's study was carried out to provide an initial clinical validation of a new GAD outcome instrument–the DAS‐A–intended to allow for daily assessment of GAD symptoms and to capture early symptom improvement.

In this study, symptomatic improvement in response to the rapidly acting benzodiazepine, lorazepam, was evident at the first assessment (week 1) in the observed cases analysis on the HAM‐A as well as at the subsequent clinic visits at weeks 2 and 4 and at end of treatment in the LOCF analysis. Symptomatic improvement in response to the more slowly acting SSRI, paroxetine, was evident only by week 2 in the observed cases analysis and at subsequent time points on the HAM‐A. These HAM‐A results, along with the results on the other standard measures including patient and clinician assessments of anxiety and quality of life, indicate that this study detected the expected signals for these anxiolytic pharmacotherapies. The HAM‐A results also provide a clinical context for understanding and evaluating the DAS‐A results.

The DAS‐A detected significant improvement in GAD symptoms in the lorazepam group over the first 6 days of treatment assessment, on study day 2 (24 h after first dose), at weeks 1, 2, and 4 in the observed cases analysis, and at end of treatment in the LOCF analysis. In contrast, improvement in GAD symptoms on the DAS‐A in the paroxetine group was seen only at weeks 2, 4 and end of treatment. These results indicate that the DAS‐A is capable of distinguishing the early treatment effects associated with lorazepam from the more slowly appearing treatment effects of paroxetine. This alignment of the DAS‐A clinical results with prior data and clinical expectations that indicate a more rapid onset of improvement in GAD symptoms for benzodiazepines than for SSRIs, as well as the similarity in DAS‐A and HAM‐A week 1 through 4 and end of treatment results, lends strength to the validity of the DAS‐A.

The definition of GAD has evolved substantially since the development of the HAM‐A in the late 1950s. This has created a mismatch between the HAM‐A and the current construct of GAD, which emphasizes worry, psychic anxiety, and tension. While several scales have recently been developed to address this issue, including the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Severity Scale (GADSS) [20], the DSM‐Based General Anxiety Disorder Symptom Severity Scale [21], and the GAD‐7 [22], the DAS‐A is the first to undergo evaluation as a daily assessment and as an assessment of onset of symptom improvement while addressing the DSM‐IV construct of GAD.

There are many methods, and little consensus, for defining the onset of symptomatic improvement for a psychotropic medication [23, 24]. In this study, we chose the average change from baseline over the first 6 days of treatment assessment as the primary measure because we anticipated that it would be more reliable and more highly powered than analyses conducted on individual days, and would answer the question of whether there were lorazepam, but not paroxetine, treatment effects occurring within the first week. Given the lack of consensus on how to assess onset and our desire to have a daily assessment instrument, we included analyses of data from individual days during the first week of therapy. Results on the direction of benefit from these analyses of individual days were all consistent with the average over the first 6 days.

While the DAS‐A was able to detect improvement on lorazepam over the first 6 days of treatment assessment, and over the first 24 h of treatment, the DAS‐A did not detect significant improvement on all of the individual days during the first week of therapy. For those individual days during the first week where a significant effect was not detected, the P values are nearly significant (P values close to 0.1) for lorazepam, suggesting that with a larger sample size, significant effects might have been detected for lorazepam on those days. The DAS‐A has been subjected to further psychometric analysis [15], including standard assessments of reliability and validity. An eight‐item version, which has deleted the less effective and redundant items, has been suggested to provide a final instrument that is more sensitive to treatment effects while maintaining full coverage of GAD symptoms.

With further refinement and item reduction, the DAS‐A is expected to be a useful tool for research studies in GAD, providing a simple means of identifying novel and rapidly acting anxiolytics. The DAS‐A may be particularly useful for evaluating day‐to‐day fluctuations in GAD severity and for evaluating the psychosocial and other factors that influence symptom severity. The DAS‐A may also be useful for practicing clinicians, as it can be easily completed by patients on a daily or weekly basis and does not require an office visit.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Feltner, Dr. Capelleri, Dr. Morlock, Ms. Harness, and Ms. Brock were Pfizer employees at the time this work was done. Dr. Sambunaris has received research funding from Pfizer.

Supporting information

Supporting info item

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the investigators who contributed to the conduct of this study and without whose help this work would not have been possible. The investigators were: Dr. Mohammed Bari (San Diego, CA), Dr. Jesse Carr (Glendale, CA), Dr. Glenn Dempsey (Albuquerque, NM), Dr. Richard Saini (Orlando, FL), Dr. Angelo Sambunaris (Atlanta, GA and Marietta, GA), Dr. Thomas Shiovitz (Sherman Oaks, CA and Northridge, CA), Dr. Bradley Vince (Overland Park, KS), Dr. Lawson Wulsin (Cincinnati, OH), and Dr. Dan Zimbroff (Orange, CA). This study was conducted in the United States and complied with all U.S. laws.

This study was funded by Pfizer, Inc.

References

- 1. ESEMeD/MHEDEA, 2000 Investigators ESotEoMD, (ESEMeD) Project ; Alonso JAM, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, Bryson H, De Girolamo GGR, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, Haro JM, Katz SJ, et al Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: Results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2004;420: 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kessler RCDO, Frank RG, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Walters EE, Wang P, Wells KBZA. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2515–2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kessler RCDR, Berglund P, Wittchen HU. Impairment in pure and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and major depression at 12 months in two national surveys. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1915–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lieb RBE, Altamura C. The epidemiology of generalized anxiety disorder in Europe. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2005;14:445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Olfson MSS, Feder A, Fuentes M, Nomura Y, Gameroff M, Weissman MM. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders in an urban general medicine practice. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:876–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maier WGM, Freyberger HJ, Linz M, Heun R, Lecrubier Y. Generalized anxiety disorder (ICD‐10) in primary care from a cross‐cultural perspective: A valid diagnostic entity? Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;101:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wittchen HUCR, Pfister H, Montgomery SA, Kessler RC. Disabilities and quality of life in pure and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and major depression in a national survey. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;15:319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pande ACCJ, Feltner DE, Janney CA, Smith WT, Weisler R, Londborg PD, Bielski RJZD, Davidson JR, Liu‐Dumaw M. Pregabalin in generalized anxiety disorder: A placebo‐controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Graham SJ, Scaife JC, Langley RW, Bradshaw CM, Szabadi E, Xi L, Crumley T, Calder N, Gottesdiener K, Wagner JA. Effects of lorazepam on fear‐potentiated startle responses in man. J Psychopharmacol 2005;19:249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolf DL, Desjardins PJ, Black PM, Francom SR, Mohanlal RW, Fleishaker JC. Anticipatory anxiety in moderately to highly‐anxious oral surgery patients as a screening model for anxiolytics: Evaluation of alprazolam. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nardi AE, Valenca AM, Nascimento I, Mezzasalma MA, Zin WA. Double‐blind acute clonazepam vs. placebo in carbon dioxide‐induced panic attacks. Psychiatry Res 2000;94:179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Allgulander C, Dahl AA, Austin C, Morris PL, Sogaard JA, Fayyad R, Kutcher SP, Clary CM. Efficacy of sertraline in a 12‐week trial for generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1642–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pollack MH, Zaninelli R, Goddard A, McCafferty JP, Bellew KM, Burnham DB, Iyengar MK. Paroxetine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: Results of a placebo‐controlled, flexible‐dosage trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959;32:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morlock RFD, Fehnel S, Williams V, Cappelleri J, Harness J, Kavoussi R, Endicott J. Development and Evaluation of the Daily Assessment of Symptoms ‐ Anxiety (DAS‐A) Scale to evaluate onset of symptom relief in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J. Psychiatric Res 2008;42:1024–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Devellis R. Scale development: Theory and applications. Thousand Oaks , CA : Sage Publications, Inc., 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guy W. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology (US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Publication No. 76‐338). Rockville , MD : National Institute of Mental Health, 1976; pp. 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Endicott JNJ, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: A new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993;29:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ware JESC Jr. The MOS 36‐item short‐form health survey (SF‐36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shear K, Belnap BH, Mazumdar S, Houck P, Rollman BL. Generalized anxiety disorder severity scale (GADSS): A preliminary validation study. Depress Anxiety 2006;23:77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stein DJ. Generalized anxiety disorder: Rethinking diagnosis and rating. CNS Spectr 2005;10:930–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD‐7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leon AC. Measuring onset of antidepressant action in clinical trials: An overview of definitions and methodology. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(Suppl 4):12–16; discussion 37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Montgomery SA, Bech P, Blier P, Moller HJ, Nierenberg AA, Pinder RM, Quitkin FM, Reimitz PE, Rosenbaum JF, Rush AJ, et al Selecting methodologies for the evaluation of differences in time to response between antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting info item