Abstract

High dose cyclophosphamide (HDC) has been successfully used for the treatment of a variety of autoimmune diseases. In this study, we sought to determine whether the use of high dose cyclophosphamide provided stabilization of relapsing remitting MS (RRMS), secondary progressive MS (SPMS), or primary progressive MS (PPMS). The parameters evaluated were EDSS scores, lesion load and brain volumes by MRI and frequency of relapses. Twenty‐three patients underwent immunoablative therapy with HDC and were followed for 3.5 years. Nine were relapsing remitting (RRMS), 11 secondary progressive (SPMS), and 3 primary progressive (PPMS). Four of 9 RRMS have had no clinical progression up to 3.5 years following treatment. Three of 9 patients maintained a normal neurologic examination with improved EDSS scores. Seven of the nine RRMS patients had reduction in flare frequency which was maintained for 3.5 years following treatment or no immunomodulating agents. Subgroup analysis in the RRMS patients of lesion load and brain parenchymal volume revealed a favorable trend in these parameters which did not reach statistical significance. The treatment was generally ineffective for SPMS and failed in the 2 PPMS patients. HDC was well tolerated, demonstrated a good safety profile and had minimal adverse effects. These results along with previous reports suggest that early use of HDC therapy in RRMS is promising.

Introduction

Experimental and clinical evidence supports a role for aberrant humoral and cellular mediated immunity in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis [1, 2, 3, 4]. Once initiated, the process generally evolves to the point that 80% of patients with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) develop secondary progression within 20 years of onset [5, 6]. Age may be a key risk factor for progression [7, 8, 9]. Neuropathological, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and clinical evidence suggests that in some patients inflammatory cytokines produced from microglia early in the disease and later from astrocytes may play a role in disease progression [10, 11] and that early immunomodulatory treatment may be beneficial in decreasing chronic glial activation and its subsequent proinflammatory effects [11, 12, 13, 14].

Immunomodulators are used in the treatment of multiple sclerosis to decrease entry of immune cells through the blood brain barrier, alter T cell reactivity, and down regulate inflammatory cytokine expression [15, 16, 17]. Although the exact mode of action of these drugs is not clearly established, the subsequent effect of this immune modulation is a significant reduction in the frequency of relapses and possibly a delay in disease progression [16, 18]. Three interferon (IFN) beta formulations are currently used in the treatment of MS. The drugs have been shown to disrupt T cell activation and alter the inflammatory cytokine profile [19, 20]. Glatiramer acetate simulates myelin basic protein and has been shown to shift the T lymphocyte profile from helper to suppressor phenotypes, as well as promote the expression of neurotrophic factors for neuroprotection [19, 21]. Various antineoplastic agents are currently under investigation for MS treatment. Mitoxantrone is a synthetic antineoplastic agent that can cross the blood brain barrier and is believed to act through various mechanisms including: (1) induction of macrophage apoptosis, therefore inhibiting demyelination and axonal loss; (2) down regulation of inflammatory cytokines; and (3) decreasing lymphocyte replication [22, 23]. Both methotrexate and cladribine show promising effects in reducing lesion load, but have not altered the EDSS [24, 25]. Monoclonal antibodies (Mabs) are currently used and are being investigated in the treatment of MS. Safety concerns have halted the use of some Mabs (TGN1412); however, natalizumab has returned to the market and is approved for first line treatment in MS [26]. Recent studies have shown excellent clinical and MRI results [27, 28].

These drugs have been shown to reduce frequency of relapses in clinical trials or stabilize lesion load in RRMS, but it has been difficult to demonstrate that they alter the course of the disease. There is evidence that decreasing the number of attacks alters the time to progressive disability [29].

Cyclophosphamide is a prodrug alkylating agent that is metabolized by hepatic cytochrome P450‐catalyzed 4‐hydroxylation, yielding cytotoxic metabolites [30, 31]. It can be used to destroy the circulating immune system, which can then be reconstituted from surviving pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells by granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor [30]. High‐dose cyclophosphamide (HDC) has been used for the treatment of a variety of autoimmune disorders including aplastic anemia, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), myasthenia gravis, and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) [32, 33, 34]. A possible mechanism for its effectiveness, suggested by Drachman, is that the immune system is “rebooted” and does not respond to the original antigenic stimulus [35]. HDC with stem cell transplantation has also been used in the treatment of MS in a variety of studies with varying results [36, 37]. In this study, we sought to determine whether the use of high‐dose cyclophosphamide provided stabilization of relapsing remitting MS (RRMS), secondary progressive MS (SPMS), or primary progressive MS (PPMS) by analyzing EDSS scores, lesion load by MRI and frequency of relapses.

Subjects and Methods

A total of 23 patients underwent high dose cyclophosphamide immunoablative treatment beginning September 2003 to April 2006. Inclusion criteria were: (1) a diagnosis of RRMS, SPMS, or PPMS; (2) age between 18 and 75; (3) an EDSS of 3–8; (4) had been on one of the IFN beta preparations or Copaxone for at least 1 year; (5) had an ejection fraction of >45%; and (6) had serum creatinine of <3mg/dL. Exclusion criteria were: (1) active malignancies; (2) chromosomal abnormalities suggestive of a myelodysplastic process; (3) active infections requiring antibiotics; (4) pregnancy; (5) known intolerance to granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor; and (6) presence of implantable devices that prohibited the use of MRI. This study was approved by the Drexel University College of Medicine Institutional Review Board (Philadelphia, PA, USA).

Prior to treatment, patients underwent baseline neurologic examination to determine EDSS, cardiac evaluation, and had baseline blood work and MRIs of the brain and spinal cord. Patients were subsequently admitted to the hospital's bone marrow transplant unit and had a Hickman catheter placed. They were premedicated with intravenous fluids, sodium bicarbonate, allopurinol, and mesna. Subsequently, a total dose of cyclophosphamide of 200 mg/kg was administered, which was divided into four daily doses of 50 mg/kg. Patients were also given lasix, diamox, and antiemetics. Granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor was administered on day 11 or 12 when the white blood cell count was zero. Prophylactic antibiotics were administered during the next 2–3 days for low‐grade temperature.

After treatment, all RRMS patients underwent follow‐up neurology examination every 3 months by the same examiner (RJS) to determine EDSS. Follow‐up MRIs were obtained every 6 months. Patient charts were reviewed and EDSS was calculated based on the neurological examination. Details on flare frequency were also obtained from the records, beginning with the first visit to the office. If the patient was referred to the center for the trial, prior records were reviewed to obtain flare frequency. The primary endpoint was a sustained decrease in EDSS of one point or more for 6 months or longer. The secondary endpoint evaluated length of time to EDSS progression. The tertiary endpoint was a reduction in flare frequency. Analysis of flare frequency before and after treatment was calculated. The number of flares per year for the 4 years prior to treatment was compared to the number of flares per year after treatment. The maximal length of time post treatment was 3.5 years.

All MRIs of the brain were obtained on 1.5 T scanners. Axial fast fluid‐attenuated inversion‐recovery (FLAIR) images were used to calculate lesion volume, and T2‐weighted axial images were used to calculate the brain parenchymal fraction (BPF), an assessment of brain volume. Images were obtained from numerous institutions that utilized different instrumentation and varying protocols. However, the acquisition parameters were sufficiently similar for calculation comparison in all relapsing remitting patients. All image analysis was quantitatively performed by one trained technician who was blinded to the treatment date and clinical data. All MRI images were analyzed using image J software (National Institutes of Health, http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij), while BPF calculations were performed with a computing routine written in Java. Sequences containing poor image quality or motion artifacts were excluded from the analysis.

Analysis of the lesion load was performed using semiautomated edge‐finding and local image segmentation techniques. Total lesion area was determined automatically by the software program as the sum of the area of all lesions. This value was then multiplied by the slice thickness to obtain the total lesion volume.

The ratio of brain parenchymal volume to total tissue volume within the surface contour (BPF) was evaluated using semiautomated analysis and calculated using an in‐house Java program. Initially the outer contour of the brain was defined and then separated from the skull and other tissues. Using histograms and thresholding techniques, intensity values were assigned to the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) and background noise. Pixels located between these values were considered parenchymal tissue.

Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life questionnaires (MSQOL‐54) were completed by patients to evaluate functional status before and after treatment.

Statistical analysis of MS flares, lesion load, brain parenchymal fraction, and quality of life scores before and after treatment was performed using pair t‐test utilizing SYSTAT 10.2 statistical software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Results

A total of 23 MS patients underwent treatment with HDC beginning September 2003 to April 2006 (Table 1). Nine patients (eight female and one male) had relapsing remitting MS. Their average age was 45.2 years (range 31–52 years). Eleven patients (nine female and two male) had secondary progressive disease, with an average age of 47.7 years (31–64 years). Three patients (two female and one male), whose average age was 51.3 years (range 38–67 years), had primary progressive disease. Three patients were lost during follow‐up. Of those patients, one had primary progressive disease and the others had secondary progressive disease.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| MS Type | Age | Sex | Sp Cord | DOTa | TTTxb | Prior therapy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt 1 | RR | 46 | F | Jan‐04 | 9 years and 6 months | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1b SC, monthly Cytoxan, Cosyntropin | |

| Pt 2 | RR | 48 | F | yes | Dec‐03 | 5 years and 8 months | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1a SC |

| Pt 3 | RR | 43 | F | yes | Dec‐03 | 8 years and 1 months | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1b SC, Cosyntropin |

| Pt 4 | RR‐Devic's | 31 | F | yes | Jan‐04 | 6 years | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1b SC |

| Pt 5 | RR | 46 | F | Sep‐04 | 9 years and 2 months | Interferon‐β1b SC, Glatiramer acetate SC | |

| Pt 6 | RR | 41 | M | yes | Apr‐04 | 3 years and 3 months | Interferon‐β1a IM, Glatiramer acetate SC |

| Pt 7 | RR | 52 | F | Mar‐04 | 3 years and 10 months | Interferon‐β1a IM, Cosyntropin | |

| Pt 8 | RR | 51 | F | yes | Sep‐04 | 12 years and 5 months | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1b SC, Glatiramer acetate SC, Cosyntropin |

| Pt 9 | RR | 49 | F | Jan‐04 | 8 months | Interferon‐β1a IM, Glatiramer acetate SC | |

| Pt 10 | SP | 54 | F | yes | Aug‐04 | 12 years and 9 months | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1b SC, Glatiramer acetate SC |

| Pt 11 | SP | 31 | F | Aug‐04 | 5 years | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1b SC, Glatiramer acetate SC, Mitoxantrone | |

| Pt 12 | SP | 44 | F | yes | Jul‐04 | 9 years and 6 months | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1a SC, Glatiramer acetate SC |

| Pt 13 | SPc | 46 | M | Dec‐04 | 8 years | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1a SC, Glatiramer acetate SC | |

| Pt 14 | SPc | 55 | F | Aug‐04 | 16 years | Interferon‐β1a IM, monthly Cytoxan, Methotrexate | |

| Pt 15 | SP | 64 | F | Jul‐04 | 23 years | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1b SC, | |

| Pt 16 | SP | 47 | F | Jul‐05 | 24 years | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1b SC, Glatiramer acetate SC, Mitoxantrone, monthly cytoxan | |

| Pt 17 | SP | 43 | F | Apr‐04 | 9 years | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1b SC | |

| Pt 18 | SP | 49 | F | Dec‐04 | 24 years | Interferon‐β1a IM, Glatiramer acetate SC | |

| Pt 19 | SP | 56 | M | Oct‐04 | 15 years and 8 months | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1b SC, Glatiramer acetate SC, | |

| Pt 20 | SP | 36 | F | yes | Nov‐04 | 18 years | Interferon‐β1a IM, Interferon‐β1b SC, Glatiramer acetate SC, Azathioprine |

| Pt 21 | PP | 38 | F | yes | Aug‐05 | 5 years | Interferon‐β1a IM, Mitoxantrone |

| Pt 22 | PPc | 67 | M | Nov‐04 | 8 years | Interferon‐β1a IM | |

| Pt 23 | PP | 49 | F | Apr‐06 | 24 years | Interferon‐β1b SC, Glatiramer acetate SC |

Sp Cord = patients with documented spinal cord lesions.

aDOT = date of treatment.

bTTTx = time to treatment after the diagnosis of MS was established.

clost to follow up.

The primary endpoint was a decrease in EDSS of one or more points for 6 months or more (Table 2). A total of nine patients with RRMS and SPMS reached the primary endpoint (39%). Seven of nine patients (78%) with RRMS met the primary endpoint. One of the two RRMS patients who did not meet the endpoint had a sustained decrease in EDSS of 0.5 points, which has been maintained for 1.5 years after treatment. The other patient had an increase in EDSS. No patients in the primary progressive group met the primary endpoint. Two of the eleven patients (18%) with secondary progressive disease met the primary endpoint.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary endpoints

| Patient | MS Type | Age | Sex | Primary end point | Secondary end point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RR | 46 | F | yes | 8 months |

| 2 | RR | 48 | F | yes | 3 years, (inc 0.5 pt) |

| 3 | RR | 43 | F | yes | none |

| 4 | RR | 31 | F | yesa | 1.5 years |

| 5 | RR | 46 | F | no (0.5 pt) | none |

| 6 | RR | 41 | M | yes | none |

| 7 | RR | 52 | F | yesb | 6 months |

| 8 | RR | 51 | F | no | 5 months |

| 9 | RR | 49 | F | yes | none |

| 10 | SP | 54 | F | no (0.5 pt) | none |

| 11 | SP | 31 | F | yes | 13 months |

| 12 | SP | 44 | F | no | none |

| 13 | SP | 46 | M | lost to follow up | |

| 14 | SP | 55 | F | lost to follow up | |

| 15 | SP | 64 | F | no | none |

| 16 | SP | 47 | F | yes | 8 months |

| 17 | SP | 43 | F | no | none |

| 18 | SP | 49 | F | no | 6–9 months |

| 19 | SP | 56 | M | no | none |

| 20 | SP | 36 | F | no | < 6 months |

| 21 | PP | 38 | F | no | none |

| 22 | PP | 67 | M | lost to follow up | |

| 23 | PP | 49 | F | no | none |

aEDSS decreased 0.5 pt 6 months after treatment, decreased 1 pt 1 year after treatment, decreased 2 pt 2 years after treatment.

bnot immediately post treatment, EDSS decreased 1 year after treatment for 2 years.

The secondary endpoint was time to EDSS progression. Four out of nine patients (44%) have had no progression to date. Of those in the RRMS group who met the primary endpoint, three patients (Patients 3, 6, and 9) have had no progression to date, and two of these patients are now normal (EDSS = 0). Patient 2 did progress 0.5 points at 3 years, which was due to development of fatigue and a subsequent flare, however, and is now normal (EDSS = 0). Patient 4 did progress after 1.5 years due to a flare, however, overall had a sustained decrease in EDSS of 1 point 1 year after treatment and 2 points 2 years after treatment. Patient 8 progressed 6 months after treatment due to a flare, however, had a sustained decrease in EDSS 1 year after treatment that has been maintained for 2 years. Patient 1 progressed at 8 months due to a flare and did not return to pretreatment baseline. Patient 5 did not meet the primary endpoint, but has had a sustained decrease in EDSS of 0.5 points that has been maintained for 2 years after treatment. Of the two patients who met the primary endpoint in the secondary progressive group (Patients 11 and 16), both patients progressed at 13 months and 8 months, respectively. There were several patients in the primary and secondary progressive subgroups (Patients 10, 12, 15, 17, 18, 19, 21, and 23) who did not meet the primary endpoint and who did not have progression of EDSS after treatment.

The tertiary endpoint evaluated flare frequency (Table 3). Seven of the nine relapsing remitting patients (78%) had reductions in flares. For statistical analysis, the flare frequency over 4 years prior to treatment was compared with the frequency post treatment (up to 3.5 years). Flare data on Patient 5 was incomplete and was not included in the statistical analysis. The overall reduction in the number of flares is statistically significant (P < 0.014, CI 0.32–1.99). Three of these patients (33%) have had no flares since the treatment. One patient (11%) had no change in the average number of flares, and one patient had an increase in the number of flares. There were two RRMS and two SPMS patients who had flares immediately after treatment. Both relapsing remitting patients had no flares for 3 years following that event, and one patient has had none since.

Table 3.

Flare frequency: average number of flares per year in RRMS patients (tertiary endpoint)

| Patient | Pre HDC | Post HDC |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0.75 |

| 2 | 1.75 | 0.5a |

| 3 | 2 | 0 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 1b | 0 |

| 6 | 2.29 | 0.4a |

| 7 | 1.5 | 1.75 |

| 8 | 2.4 | 0.3 |

| 9 | 2 | 0 |

aone flare immediately after treatment.

bexact number unknown, but more than 1 per year.

Overall pre‐HDC = 1.74 and post‐HDC = 0.59.

P‐value < 0.014.

95% CI 0.32–1.99.

Analyses of lesion load and BPF are shown in Table 4. The data for all relapsing remitting patients are included. Only complete pre‐ and post‐treatment data for primary and secondary progressive patients are included, therefore only four secondary progressive patients are listed. The reasons for not including a great deal of the SP and PP imaging data for quantitative analysis were: (1) acquisition parameters and MRI units were too disparate; (2) insufficient image acquisition for each study; (3) scheduled MRIs were not obtained; and (4) patients that did not improve, did not want further studies. A favorable trend is seen in the relapsing remitting patients with regards to preservation of BPF and a reduction in lesion load, which did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05). No trends could be observed in either the primary or secondary progressive groups.

Table 4.

MRI analysis

| Relapsing remitting | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion load (cm3) | BPF | |||||

| 1+ year pretreatmenta | < 3 months posttreatmenta | 1+ year posttreatmenta | 1+ year pretreatmenta | < 3 months posttreatmenta | 1+ year posttreatmenta | |

| Pt 1 | 95.9 | 207.1 | 87.0 | 0.849 | 0.926 | 0.797 |

| Pt 2 | 15.3 | 8.6 | 6.2 | 0.956 | 0.921 | 0.898 |

| Pt 3 | 148.4 | 206.3 | NA | 0.841 | 0.827 | NA |

| Pt 4 | 29.0 | 24.8 | 29.3 | 0.894 | 0.817 | 0.901 |

| Pt 5 | 25.9 | NA | 11.4 | 0.834 | NA | 0.930 |

| Pt 6 | 8.6 | 9.5 | 7.1 | 0.946 | 0.954 | 0.944 |

| Pt 7 | 16.2 | 15.5 | 17.2 | 0.881 | 0.903 | 0.933 |

| Pt 8 | 131.7 | NA | 134.9 | 0.904 | NA | 0.922 |

| Pt 9 | NA | NA | 26.8 | NA | NA | 0.926 |

| Overall | 46.1 | 41.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | ||

| P value | 0.142 | 0.69 | ||||

| Secondary progressive | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion load (cm3) | BPF | |||||

| 1+ year pretreatmenta | < 3 months posttreatmenta | 1+ year posttreatmenta | 1+ year pretreatmenta | < 3 months posttreatmenta | 1+ year posttreatmenta | |

| Pt 10 | 48.1 | 41.0 | NA | 0.948 | 0.882 | NA |

| Pt 11 | 404.4 | 315.9 | 494.3 | 0.874 | 0.809 | 0.799 |

| Pt 17 | 235.9 | 260.2 | 243.4 | 0.808 | 0.755 | 0.807 |

| Pt 19 | 88.6 | 155.3 | 191.0 | 0.884 | 0.803 | 0.776 |

aAverage results; NA = no data available.

Subgroup analysis in relapsing remitting patients of lesion load, BPF, and flare frequency showed no correlation between flare frequency and improvements in lesion load or stabilization of brain volume. Analysis of relapsing remitting patients who met the primary endpoint with their lesion load was performed and revealed no trend in reduction of lesion load with EDSS improvement. No correlation could be found between those who met the primary and secondary endpoints and stabilization of brain volume.

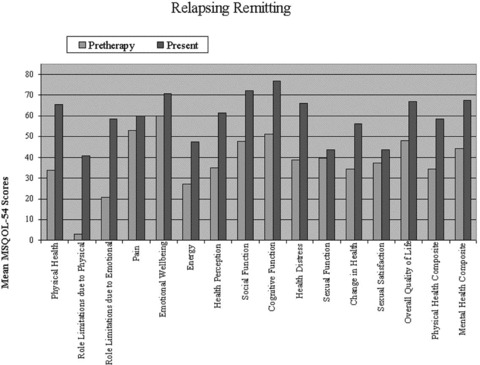

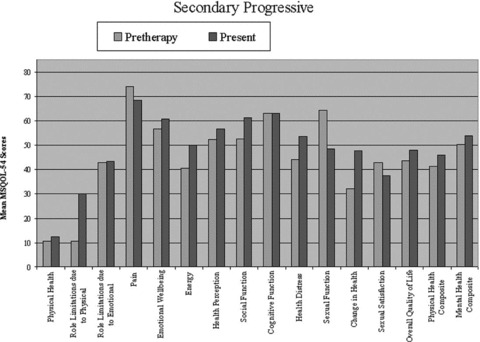

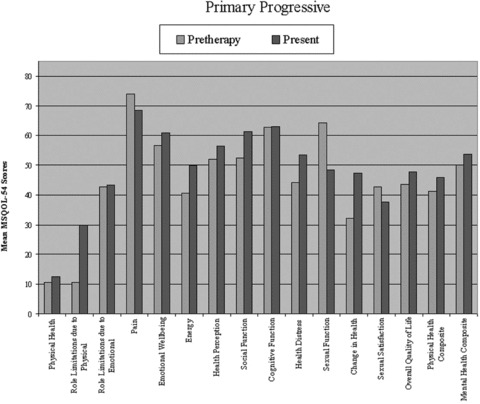

Analyses of quality of life scores using the MS‐QOL 54 survey are presented in 1, 2, 3. A total of 16 patients filled out both pre‐ and posttreatment questionnaires. The patients who only completed either pre‐ or postquestionnaires were not included in the composite analysis. In all subgroups, an improvement was seen in the mean physical and mental health composite scores and overall quality of life; however, this did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05). Analysis of the physical health, emotional well‐being, and social functioning subsets in the relapsing remitting group did reach statistical significance (P < 0.05). Due to limited subgroup size, statistical analysis could not be performed for those with primary progressive disease.

Figure 1.

Quality of life scores using the MS‐QOL54 survey pre‐ and post high‐dose cyclophosphamide treatment in relapsing remitting MS patients.

Figure 2.

Quality of life scores using the MS‐QOL54 survey pre‐ and post high‐dose cyclophosphamide treatment in secondary progressive MS patients.

Figure 3.

Quality of life scores using the MS‐QOL54 survey pre‐ and post high‐dose cyclophosphamide treatment in primary progressive MS patients.

Adverse Events

Adverse reactions were few (Table 5). Serious complications included reactivation of CMV in the liver in one patient that required treatment. Also, two patients developed pleural and pericardial effusions that required thoracentesis. Cultures of the fluid were negative. Otherwise, complications were few and included neutropenic fever, nausea and vomiting, alopecia, and cellulitis that responded to antibiotics.

Table 5.

Adverse reactions

| Adverse Reactions | No. of pts |

|---|---|

| GI toxicity—nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | 3 |

| Neutropenic fever | 13 |

| Rash—noninfectious | 1 |

| Pleural/pericardial effusion | 2 |

| Infection | |

| C Diff | 2 |

| Pneumonia | 3 |

| Bacteremia | 3 |

| UTI | 2 |

| Folliculitis | 1 |

| Cellulitis | 4 |

| Reactivation of herpes | 1 |

| Reactivation of CMV hepatitis | 1 |

| Mucositis | 1 |

| Other—cardiovascular | |

| SVT | 1 |

| Hypotension | 1 |

Discussion

The results of this trial show that the use of high dose cyclophosphamide in the treatment of the relapsing remitting form of MS may be promising. Four patients have had no progression to date (up to 3.5 years following treatment), three patients returned to normal, and most had reductions in EDSS that have led to improvements in quality of life. Seven of nine patients had reductions in flare frequency for up to 3.5 years following treatment. This suggests that the underlying pathophysiology of relapsing remitting disease may be different from secondary and primary progressive forms, and supports recent evidence that different immune mechanisms may initiate and sustain disease in the different subtypes of multiple sclerosis [38, 39]. The recent article by Lublin linking relapses and progression of disability would suggest that agents that modify relapses may affect disease progression [29, 40]. If so, the improvement in flare frequency by HDC, in addition to the improvement in EDSS suggests that HDC may be a useful agent in modifying progression, particularly in relapsing remitting disease. Also the three patients whose EDSS is now zero were treated early in the course of their disease. Those with SPMS and PPMS did not show substantial improvement in either EDSS or MRI analysis, which suggests that HDC may alter the course of the disease early in its inflammatory phase. This supports recent studies suggesting early immunomodulatory therapy may be useful in preventing progression in MS [29, 40, 41]. There were several patients with SPMS and PPMS, however, whose EDSS did not progress following treatment with HDC. It is difficult to predict the natural course of MS in individual patients and it is unknown at this time, whether or not the stabilization of EDSS after treatment constitutes treatment response. However, a prior study has indicated that HDC is effective in stabilizing rapidly deteriorating secondary progressive disease [37].

Our results are similar to the findings reported from the Krishnan study in regard to relapsing remitting patients [42]. It also confirmed results of Gladstone's trial, but with longer patient follow‐ups we are able to demonstrate a prolonged response to treatment [43]. HDC is well tolerated, has a good safety profile, and a long history of beneficial use [32, 33, 34, 44]. Adverse effects of treatment were minimal in these studies.

This study, along with that of Gladstone and Krishnan, supports the safety and tolerability of immunoablative therapy of high dose Cytoxan in the treatment of relapsing remitting MS. The number of patients in each group was too small to make any definitive statement with regard to effectiveness of treatment but as noted in the two prior studies, it is suggestive that this protocol is partially effective in those patients with RRMS that have failed conventional therapy and that would be expected to have a highly aggressive inflammatory component to their illness [45].

Earlier studies utilizing various protocols with intermittent but nonablative doses of cyclophosphamide demonstrated reduced relapse rate and decreased progression of disability [46, 47]. The use of pulsed therapies and combinations of cyclophosphamide and ACTH or methylprednisolone as well as pulsed mitoxantrone are partially effective in RRMS [46, 48].

A possible advantage of HiCy treatment is the ablation of the entire mature immune system, particularly its autoimmune component. When reconstituted from the stem cell population that has not been damaged there may be immune tolerance of the inciting causative antigen that initiated MS [49]. These results along with previous reports suggest early use of ablative HiCy therapy in patients with RRMS who have failed standard therapies (induction), followed by immunomodulating therapy may maintain clinical benefit.

The limitations of the study are: (1) its open label nonrandomized design; (2) lack of specific quantitative measurement of motor improvement such as gait, finger tapping speed, and agility assessments; (3) lack of uniformity of MRI acquisition parameters; (4) lack of controls and; (5) small size. The strengths of this study are the length of observation of some patients (up to 3.5 years after treatment) and the assessment by the same observer in the RRMS group.

All human studies have been reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at Drexel University College of Medicine. All persons that participated in this study gave their informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Holmoy T. Immunopathogenesis of multiple sclerosis: Concepts and controversies. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 2007;187:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mancardi G, Hart BA, Capello E, et al Restricted immune responses lead to CNS demyelination and axonal damage. J Neuroimmunol 2000;107:178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Racke MK, Ratts RB, Arredondo L, Perrin PJ, Lovett‐Racke A. The role of costimulation in autoimmune demyelination. J Neuroimmunol 2000;107:205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ziemssen T, Ziemssen . The role of the humoral immune system in multiple sclerosis (MS) and its animal model experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). Autoimmun Rev 2005;4:460–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bongioanni P, Mosti S, Romano MR, Lombardo F, Moscato G, Meucci G. Increased T‐lymphocyte interleukin‐6 binding in patients with multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2000;7:291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Montalban X. The importance of long‐term data in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2006;253(Suppl. 6):vi9–vi15. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koch M, Mostert J, Heersema D, De Keyser J. Progression in multiple sclerosis: Further evidence of an age dependent process. J Neurol Sci 2007;255:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stankoff B, Mrejen S, Tourbah A, Fontaine B, Lyon‐Caen O, Lubetzki C, Rosenheim M. Age at onset determines the occurrence of the progressive phase of multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2007;68:779–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vukusic S, Confavreux C. Natural history of multiple sclerosis: Risk factors and prognostic indicators. Curr Opin Neurol 2007;20:269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bruck W. The pathology of multiple sclerosis is the result of focal inflammatory demyelination with axonal damage. J Neurol 2005; 252(Suppl. 5):v3–v9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Petzold A, Eikelenboom MJ, Gveric D, et al Markers for different glial cell responses in multiple sclerosis: Clinical and pathological correlations. Brain 2002;125:1462–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Drew PD, Xu J, Storer PD, Chavis JA, Racke MK. Peroxisome proliferators‐activated receptor agonist regulation of glial activation: Relevance to CNS inflammatory disorders. Neurochem Int 2006;49:183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kieseier BC. Assessing long‐term effects of disease‐modifying drugs. J Neurol 2006;253(Suppl. 6):vi23–vi30. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rovaris M, Gambini A, Gallo A, et al Axonal injury in early multiple sclerosis is irreversible and independent of the short‐term disease evolution. Neurology 2005;65:1626–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chofflon M. Mechanisms of action for treatments in multiple sclerosis: Does a heterogeneous disease demand a multi‐targeted therapeutic approach? BioDrugs 2005;19:299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang WX, Huang P, Hillert J. Systemic upregulation of CD40 and CD40 ligand mRNA expression in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2000;6:61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kieseier BC, Hemmer B, Hartung HP. Multiple sclerosis: Novel insights and new therapeutic strategies. Curr Opin Neurol 2005;18:211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carra A, Onaha P, Sinay V, et al A retrospective, observational study comparing the four available immunomodulatory treatments for relapsing‐remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2003;10:671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clerico M, Contessa G, Durelli L. Interferon‐beta1a for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2007;7:535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang J, Hutton G, Zang Y. A comparison of the mechanisms of action of interferon beta and glatiramer acetate in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Clin Ther 2002;24:1998–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wolinsky JS. Glatiramer acetate for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2004;5:875–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cohen BA, Mikol DD. Mitoxantrone treatment in multiple sclerosis: Safety considerations. Neurology 2004;63:S28–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scott LJ, Figgit DP. Mitoxantrone: A review of its use in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2004;18:379–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brousil JA, Roberts RJ, Schlein AL. Cladribine: An investigational immunomodulatory agent for multiple sclerosis. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:1814–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gray OM, McDonnell GV, Forbes RB. A systematic review of oral methotrexate for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2006;12:507–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cree B. Emerging monoclonal antibody therapies for multiple sclerosis. Neurologist 2006;12:171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dalton CM, Miszkiel KA, Barker GJ, et al Effect of natalizumab on conversion of gadolinium enhancing lesions to T1 hypointense lesions in relapsing multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2004;251:407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miller DH, Soon D, Fernando KT, et al MRI outcomes in a placebo‐controlled trial of natalizumab in relapsing MS. Neurology 2007;68:1390–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lublin F. The incomplete nature of multiple sclerosis relapse resolution. J Neuro Sci 2007;256(Suppl. 1):S14–S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cohen Y, Polliack A, Nagler A. Treatment of refractory autoimmune diseases with ablative immunotherapy using monoclonal antibodies and/or high‐dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell support. Curr Pharm Des 2003;9:279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang J, Tian Q, Yung Chan S, et al Metabolism and transport of oxazaphosphorines and clinical implications. Drug Metab Rev 2005;37:611–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brodsky RA, Sensenbrenner LL, Smith BD, et al Durable treatment free remission after high‐dose cyclophosphamide therapy for previously untreated severe aplastic anemia. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Drachman DB, Brodsky RA. High‐dose therapy for autoimmune neurologic disorders. Curr Opin Oncol 2005;17:83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gladstone DE, Brannagan TH, Schwartzman RJ, Prestrud AA, Brodsky I. High‐dose Cyclophosphamide for severe refractory myasthenia gravis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:789–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Drachman DB, Jones RJ, Brodsky RA. Treatment of refractory myasthenia: “Rebooting” with high dose Cyclophosphamide. Ann Neurol 2003;53:7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Capello E, Saccardi R, Murialdo A, et al Intense immunosuppresion followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in severe multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci 2005;26(Suppl. 4):S200–S203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Perini P, Gallo P. Cyclophosphamide is effective in stabilizing rapidly deteriorating secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2003;250:834–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boylan MT, Crockard AD, McDonnell GV, Armstrong MA, Hawkins SA. CD80 (B7‐1) and CD86 (B7‐2) expression in multiple sclerosis patients: Clinical subtype specific variation in peripheral monocytes and B cells and lack of modulation by high‐dose methylprednisolone. J Neurol Sci 1999;167:79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Filion LG, Matusevicius D, Graziani‐Bowering GM, Kumar A, Freedman MS. Monocyte‐derived IL12, CD86 (B7‐2) and CD40L expression in relapsing and progressive multiple sclerosis. Clin Immunol 2003;106:127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gilbert ME, Sergott RC. New directions in optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2007;7:259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gonsette RE. Compared benefit of approved and experimental immunosuppressive therapeutic approaches in multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2007;8:1103–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Krishnan C, Kaplin AI, Brodsky RA, et al Reduction of disease activity and disability with high‐dose cyclophosphamide in patients with aggressive multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2008;65:1044–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gladstone DE, Zamkoff KW, Krupp L, et al High‐dose Cyclophosphamide for moderate to severe refractory multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2006;63:1388–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brannagan TH 3rd, Pradhan A, Heiman‐Patterson T, et al High dose Cyclophosphamide without stem cell rescue for refractory CIDP. Neurology 2002;58:1856–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jeffery DR. The argument against the use of cyclophosphamide and mitoxantrone in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2004;223:41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carter JL, Hafler DA, Dawson DM, Orav J, Weiner HL. Immunosuppression with high‐dose i.v. cyclophosphamide and ACTH in progressive multiple sclerosis: Cumulative 6‐year experience in 164 patients. Neurology 1981;38:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hommes OR, Prick JJ, Lamers KJ. Treatment of the chronic progressive form of multiple sclerosis with a combination of cyclophosphamide and prednisone. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1975;78:59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Delmont E, Chanalet S, Bourg V, Soriani MH, Chatel M, Lebrun C. [Treatment of progressive multiple sclerosis with monthly pulsed cyclophosphamide‐ methylprednisolone: Predictive factors of treatment response]. Rev Neurol Paris 2004;160:659–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mayumi H, Umesue M, Nomoto K. Cyclophosphamide‐induced immunological tolerance: An overview. Immunobiology 1996;195:129–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]