Abstract

For almost three decades ambroxol has been used in the therapy of airway diseases. In 2002, ambroxol lozenges were marketed for the treatment of sore throat making use of its local anesthetic effect. Detailed investigations of ambroxol with modern pharmacological methods yielded additional interesting results: ambroxol has been found to have profound effects on neuronal voltage‐gated Na+, as well as Ca2+ channels, and to effectively reduce chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain in rodents. The question was raised whether ambroxol affects the central nervous system (CNS) directly, or whether its effects can be explained solely by a peripheral action. This issue was addressed by reexamining pharmacokinetics, as well as toxicology of ambroxol. It has been concluded that even at the highest clinically used doses ambroxol does not have significant direct effects on the CNS. At clinically relevant plasma concentrations ambroxol either does not penetrate blood‐brain barrier, or its brain levels are too low to cause relevant effects. The analgesic effects of ambroxol by either systemic administration to animals, or by topical application in humans can be explained by ambroxol‐induced blockade of ion channels in peripheral neurons.

Keywords: Ambroxol, Lidocaine, Mexiletine, Benzocaine, Local Anesthetics, Inflammation, Analgesics, Na+ channels, Ca2+ channels

Introduction

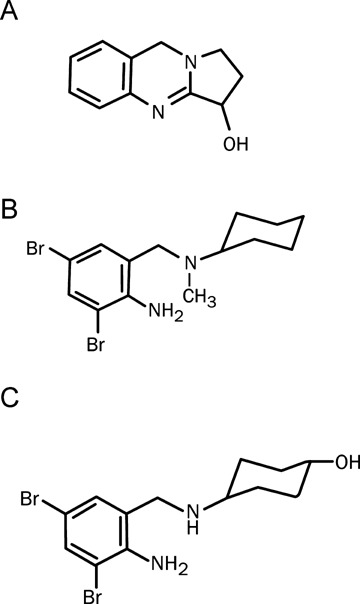

Ambroxol has been used in the therapy of airway diseases since late 1970s. Its history can be traced, however, to ayurvedic medicine in ancient India. The plant Adhatoda vasica has been used in India for similar indications for centuries. In Germany this plant is still called ‘Indisches Lungenkraut’ (Indian lung weed). The likely active substance in the plant is the alkaloid, vasicine. A chemically related drug, bromhexine, was introduced in 1965 to treat mild respiratory disorders. Ambroxol, the active metabolite of bromexine, has been found to be responsible for the therapeutic effect; and found to be superior to bromhexine in its pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and side effect profile. The chemical structures of vasicine, bromhexine, and ambroxol are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of (A) vasicine, (B) bromhexine, and (C) ambroxol.

There are several reasons for reanalysis of the properties of an old compound. First, old compounds have been often developed without knowledge of their molecular mechanism(s) of action; they were optimized for the desired pharmacologic effect. The elucidation of their mechanism of action with the state‐of‐the‐art methodology is likely to explain why the old compound was effective. Second, as drug development has been less mechanism‐oriented, old compounds were broadly characterized in preclinical in vivo experiments. Thus, the reanalysis of the available in vivo data, may help to better understand drug's properties. Third, the older a drug, the more data are available to analyze its profile, including not only preclinical, but, more importantly, clinical pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic, as well as safety data.

Recent studies discovered some molecular effects of ambroxol, which might be relevant to the therapy of central nervous system (CNS) disorders. These findings justify asking whether ambroxol has a direct effect on the CNS. The following sections briefly describe molecular and biological mechanisms of ambroxol's action, with an emphasis on the effects possibly involving CNS.

Pharmacology

Effects on Respiratory Function/Airway Parameters

By oral (p.o.) administration to animals ambroxol has expectorant effects. At 1 to 8 mg/kg in rabbits and at 4 to 16 mg/kg in guinea pigs it increased dose‐dependently bronchial secretion (Püschmann and Engelhorn 1978). In rats ambroxol suppressed citric‐acid induced cough with an ID50 of 105 mg/kg p.o. and at 60 mg/kg/day for 7 days it increased surfactant production. More recent studies found that at 2 × 75 mg/kg ambroxol affects the synthesis of surfactant proteins (Seifart et al. 2005). In vitro at one μmol/L ambroxol inhibited sodium absorption in canine airway epithelial cells. This effect should lead to an increase in the water content (and thereby reduce the viscosity) of airway mucus in vivo (Tamaoki et al. 1991). The beneficial effects of ambroxol on airway function have been demonstrated clinically in several investigations (at 45 mg/day, Nobata et al. 2006; 75 mg/day, Cegla 1988; 60 to 120 mg/day, Dirksen et al. 1987, Salerni and Passali 2003; or 3000 mg/day, Schillings and Probst 1992). As interesting as these findings may be, they are of minor importance for possible CNS effects of ambroxol.

Antiinflammatory and Antioxidant Effects

Several CNS disorders are associated with or influenced by inflammatory processes. These disorders include stroke, Alzheimer's, and Parkinson's diseases as well as multiple sclerosis. In some of these disorders antiinflammatory drugs are used as standard therapy (for review, see Zipp and Aktas 2006; Lucas et al. 2006).

In various models ambroxol had pronounced effects on inflammatory parameters or pathways. Antioxidant effect of ambroxol has been demonstrated in cell‐free systems (e.g., degradation of superoxide radicals at 10–100 μmol/L, Felix et al. 1996; or suppression of hyaluronic acid degradation induced by hydroxy radicals at 1–1000 μmol/L, Stetinová et al. 2004). In cultured zymosan‐activated mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells, ambroxol, at 1 to 1000 μmol/L reduced the release of reactive oxygen species (Gillissen et al. 1997). At 10 to 100 μmol/L it inhibited erdosteine‐induced production of superoxide anions by alveolar macrophages (Jang et al. 2003). At concentrations ranging from 10 to 1000 μmol/L ambroxol reduced the release of cytokines from human leukocytes as well as the function of silica‐activated macrophages; it also suppressed neutrophil histotoxicity (Gibbs et al. 1999; Kim et al. 2002; Ottonello et al. 2003). At doses ranging from 10 to 90 mg/kg the antioxidant and antiinflammatory effects of ambroxol have been demonstrated in vivo (Stetinová et al. 2004; Su et al. 2004). The models used in these studies, focused, however, on peripheral organs, for example, lungs and no data are available on ambroxol's effects on brain inflammation. Because stroke, multiple sclerosis, or meningitis (Zipp and Aktas 2006) are known to be associated with leukocyte invasion of CNS, one could hypothesize that ambroxol, if it enters CNS, could have beneficial effects in these disorders.

Effects on Neuronal Function

Ambroxol's efficacy as a local anesthetic has been described in the first publication on its pharmacology: a solution containing 1% ambroxol suppressed the corneal reflex in the rabbit's eye more potently than procaine, but with a shorter duration of action (Püschmann and Engelhorn 1978). Looking for short‐acting local anesthetics for ophthalmic use in humans, Klier and Papendick (1977) tested ambroxol eye drops clinically. They confirmed that ambroxol has a local anesthetic effect of short duration. Some individuals reported, however, itching sensation during the first seconds after administration; this unwanted effect prevented further development of ambroxol eye drops. The local anesthetic effect of ambroxol was, however, rediscovered two decades later, and lozenges containing 20 mg ambroxol were marketed for the treatment of sore throat (Fischer et al. 2002; Schutz et al. 2002). In other studies molecular mechanisms of ambroxol action were investigated with modern methods. The investigations yielded highly interesting results, including the discovery of ambroxol's effect on neuronal signal transduction; these findings are discussed below.

Effects on Na+ Channels

Because ambroxol has a local anesthetic effect, it was not surprising that it was found to block neuronal voltage‐gated Na+ channels. This inhibitory effect had, however, two remarkable properties. First, ambroxol had the unique feature of blocking tetrodototoxin (TTX)‐resistant Na+ channels (Nav1.8) in small (pain‐sensing) dorsal root ganglion neurons more potently than TTX‐sensitive channels. The IC50 values for the blockade of resting channels were 35 and 100 μmol/L, respectively. Recombinantly expressed Na+ channels (rat Nav1.2), which are found in central neurons in vivo, were half‐maximally blocked by ambroxol at 111 μmol/L. Na+ currents in primary cultured rat spinal cord neurons were suppressed by ambroxol at similar concentration. At 10 to 100 μmol/L ambroxol altered action potential properties (e.g., slope and amplitude) in primary cultured rat cortical neurons, which further supports the physiological relevance of these findings (Weiser 2000; Weiser and Wilson 2002; and unpublished results).

The suppression of Nav1.8 channel function by pharmacological blockade or reduction of channel protein levels effectively reduced pain‐related behavior in animal models of inflammatory, vascular, or neuropathic pain (Yoshimura et al. 2001; Lai et al. 2002; Ekberg et al. 2006; Jarvis et al. 2007). The potency of ambroxol as a Na+ channel antagonist is rather high, compared with other channel blockers. As a blocker of resting channels ambroxol is 55, 39, and 13 times more potent, than benzocaine, lidocaine, or mexiletine, respectively (Weiser 2006; Table 1).

Table 1.

The effects of local anesthetics on Na+ and Ca2+ currents IC50 values in μM ± SEM for resting channels

| Channels | Lidocaine | Mexiletine | Benzocaine | Ambroxol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nav1.8 | 1345 + 266c | 445 + 17.2c | 1901 + 240c | 34.3 + 1.9c |

| Nav1.2 | 1105 + 45c | 305 + 36a | 814 + 85c | 110 + 8.3b |

| Ca2+ channels | 3134 ± 145 | 510.3 ± 16.1 | 2605 ± 178 | 140.4 ± 7.8 |

Inhibition of Nav1.2 (recombinantly expressed in a mammalian cell system), Nav1.8, and Ca2+ channels (native channels in rat sensory neurons) by the four test compounds. The concentrations for half‐maximum inhibition of resting channels were obtained by applying voltage jumps to 0 mV from a holding potential of −100 mV (Na+ channels) and −80 mV (Ca2+ channels), respectively, in the absence and presence of various concentrations of the test compounds.

aData from Weiser et al. 1999b.

bData from Weiser and Wilson 2002.

cData from Weiser 2006.

Calcium channel data are from own unpublished experiments.

Lidocaine and mexiletine were shown to suppress neuropathic pain in humans, and their clinically achievable plasma levels are about 16 and 11 μmol/L, respectively (Ferrante et al. 1996; Jarvis and Coukell 1998). In the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome, ambroxol is administered at doses resulting in peak plasma levels of about 5.8 μmol/L (Mezzetti et al. 1990). Together with the reported IC50 values for Na+ channel blockade (Weiser 2006; Table 1) these data can be used for estimation of clinically relevant plasma concentrations of these drugs required for inhibition of TTX‐resistant and TTX‐sensitive Na+ channels (assuming that the pharmacokinetic properties of these drugs are similar).

This simplistic model suggests that ambroxol can be expected to inhibit TTX‐resistant Na+ channels in vivo more effectively than TTX‐sensitive channels. In this respect ambroxol can be expected to be more potent than either lidocaine or mexiletine. Tonic block of TTX‐sensitive channels could be expected to be around 1% for each of the three compounds. The same amount of inhibition of TTX‐resistant channels would be observed for lidocaine and mexiletine, whereas block by ambroxol would be around 12%. Qualitatively comparable results were obtained when the data for phasic block (with 5 Hz stimulation frequency) were analyzed (for details: see Weiser 2006). As simplistic as this model might be, it shows that even moderate selectivity could account for relevantly different effects on Na+ channel subtypes in vivo.

Effects on Ca2+ Channels

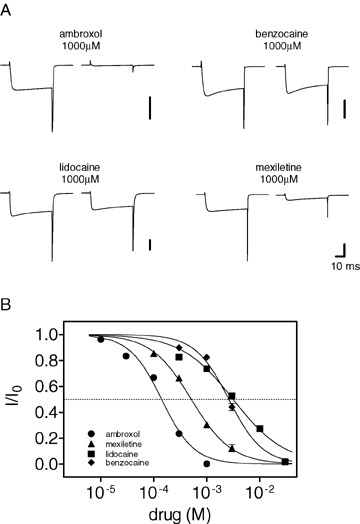

Voltage‐gated Na+ and Ca2+ channels are structurally related, and Ca2+ channel blockade has been demonstrated for some Na+ channel blockers. To test whether this was also true for ambroxol, its effects on Ca2+ channels in rat sensory neurons were investigated in a head‐to‐head comparison with lidocaine, mexiletine, and benzocaine. It turned out that all four compounds inhibited Ca2+ channel function, and that ambroxol had the highest potency (Table 1; Fig. 2). Sensory neurons express various Ca2+ channels (Scroggs and Fox 1992; Catterall et al. 2005; Hogan 2007). The small diameter sensory neurons investigated here mainly express L‐ and N‐type Ca2+ channels, which contribute to approximately 80% of their total Ca2+ currents (Scroggs and Fox 1992). Ambroxol blocked total Ca2+ current with an IC50 value of 140 μmol/L (Table 1). When N‐type channels were blocked by 2 μmol/L omega‐conotoxin GVIA, ambroxol's IC50 for the block of the remaining (non N‐type) channels was comparable (119 μmol/L). Similar values for the blockade of native Ca2+ channels were reported by Jiang et al. (2006). Ambroxol blocked P/Q‐, N‐, and R‐type channels (Cav2.1, Cav2.2, and Cav2.3, respectively) in a recombinant system with comparable potency (IC50 values around 100 μmol/L) and showed no preference for certain channel subtypes. Thus, ambroxol appears to be rather nonselective in respect to the blockade of neuronal Ca2+ channels.

Figure 2.

Ca2+ channel block in small diameter rat sensory neurons by Na+ channel blockers. The whole‐cell, voltage‐clamp mode of the patch‐clamp technique was used, 5 mM Ba2+ in the extracellular medium was used as charge carrier. All other ion channels were blocked by pharmacological or biophysical means. Currents were elicited by voltage changes from −80 to 0 mV in the absence or presence of the drugs. (A) Typical current traces recorded for the four compounds. The drugs produced different amounts of blockade at the applied concentration of 1000 μM. The vertical bar represents 5 nA. (B) Concentration‐response relationships for the blockade of Ca2+ channels. Each concentration was tested with at least five cells, and the data points were fitted by logistic equations, giving the IC50 values for each drug (see Table 1). Data are shown as mean values ± SEM.

Cav2.2 channel blockers (e.g., ziconotide) are proposed as treatment options for severe pain. The incidence of ziconitide side effects (dizziness, nausea, and asthenia) is high (between about 20 and 50% in studies summarized by Wallace 2006). Similar side effects should also be expected with ambroxol, if it entered the CNS.

Effects at Glutamate Receptors

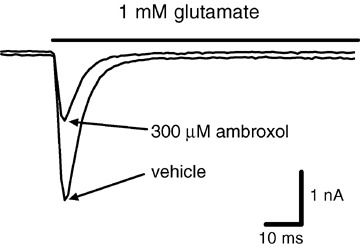

Ionotropic human GluR1/2 receptors belong to the class of μα ‐amino‐3‐hydroxy‐5‐methyl‐4‐isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors (Fig. 3). They are crucial for fast excitatory neurotransmission in the CNS, and blockers of these channels are neuroprotective in animal models of ischemic stroke and suppress convulsions in models of epilepsy (Weiser et al. 1999a; Wienrich et al. 2001). Ambroxol's effects on human AMPA receptors were tested in mammalian (HEK) cells stably transfected with GluR1/GluR2 heteromers. Patch‐clamp technique in the voltage‐clamp mode at a holding potential of –80 mV was used. Glutamate, 1 mmol/L, was applied to the cells in either the absence or presence of various concentrations of ambroxol. Ambroxol blocked glutamate‐induced currents, but with relatively low potency (IC50= 354 μM; its effects on other glutamate receptor subtypes were not tested). It could have been suspected that ambroxol is a general ion channel blocker. This turned out not to be the case, because at concentrations up to 1 mM ambroxol did not inhibit glycine‐, or GABA‐activated chloride currents in rat spinal cord neurons, and had no effect on heterologously expressed human TRPV1 receptors (data not shown). Thus, ambroxol is not a nonselective inhibitor of ion channels.

Figure 3.

Ambroxol blocks ionotropic glutamate receptors. Human heteromeric GluR1/2 receptors were stably expressed in HEK 293 cells and investigated in the whole‐cell, voltage‐clamp mode of the patch clamp technique (holding potential: −80 mV). Currents were elicited by application of 1 mM glutamate (indicated by the bar). Ambroxol suppressed glutamate‐induced membrane currents with an IC50 value of 354 ± 33 μM.

Effects in In vivo Pain Models

Considering the above‐mentioned effects of ambroxol on neuronal ion channels, it was reasonable to test ambroxol in animal pain models. The chosen doses of ambroxol were expected to produce plasma levels comparable to those achievable in the clinic. Gabapentin, a well‐known drug effective in the treatment of neuropathic and other types of severe pain in humans, was used in all investigations as a reference compound.

Neither ambroxol, at doses from 30 to 1000 mg/kg p.o., nor gabapentin, at doses up to 100 mg/kg p.o., were effective in models of acute pain (hot plate and tail‐flick assays in rats). However, in all models of persistent, inflammatory, or neuropathic pain, ambroxol was at least as effective as gabapentin. At doses used the plasma levels of gabapentin exceeded clinically achievable levels (Table 2, Gaida et al. 2005). Ambroxol had a rather steep dose‐effect relationship. In most models significant effects were observed with ambroxol at doses equal to or greater than 300 mg/kg.

Table 2.

Analgesic effects of ambroxol (1000 mg/kg) and gabapentin (100 mg/kg) in various rat models of acute, chronic, neuropathic, and inflammatory pain. The effects are expressed as mean percent reduction in pain

| Ambroxol | Gabapentin | |

|---|---|---|

| Hot plate assay | 8 | 25 |

| Tailflick assay | 10 | 5 |

| Formalin paw model | 97* | 70* |

| CCI thermal hyperalgesia | 100* | 67* |

| CCI cold allodynia | 74* | 77* |

| CCI mechano hyperalgesia | 76* | 46 |

| PNL mechano allodynia | 100* | 72* |

| CFA mechano allodynia | 43* | 45* |

Ambroxol and gabapentin were administered p.o. in rat models of acute (hotplate, tailflick), chronic (formalin paw), neuropathic (chronic constriction injury (CCI), partial nerve ligation (PNL)), and arthritis (complete Freund's adjuvant administration (CFA)) pain.

*indicates statistical significance compared to the appropriate vehicle group. Significance of differences between the drugs effects was not assessed. Usually, 8–10 animals per group were used. Data from Gaida et al. 2005.

Similar steep dose‐response relationship was observed in a clinical study of the analgesic effect of intravenously infused lidocaine in neuropathic pain (Ferrante et al. 1996). Thus, the steep dose‐response relationship might be typical for the analgesic activity of systemic Na+ channel blockers.

Other physiological functions mediated by C‐fibers include micturition, and there is a therapeutic need for new approaches to the treatment of stress incontinence. In an animal model of this disorder (acetic‐acid infusion induced bladder hyperactivity), ambroxol, at 30 to 300 mg/kg p.o. effectively and dose‐dependently reversed the effect of the noxious stimulus (Burgard et al. 2004).

Take together, these findings indicate that ambroxol affects neuronal signal transduction and has analgesic activity, probably mediated by suppression of C‐fiber function and perhaps other mechanisms. Cough reflex is also a complex phenomenon that involves C‐fibers (Canning et al. 2004; Mazzone et al. 2005; Widdicombe 2006). Thus, it is conceivable that some of ambroxol's effects on cough and other symptoms associated with diseases of the airways are related to its C‐fiber blocking properties.

In CNS neurons Nav1.8 channels are not expressed. On the other hand, ambroxol was shown to potently affect other ion channels (including TTX‐sensitive Na+ channels, like Nav1.2), which are present in central neurons. If one assumes that ambroxol passes blood‐brain barrier, the drug would be expected to have CNS effects. This issue will be further addressed in the next sections, which will highlight pharmacokinetic and toxicologic properties of ambroxol in animals and humans.

Pharmacokinetics

In animals (e.g., mouse, rat, rabbit), as well as in humans, ambroxol is well absorbed after oral administration (Hammer et al. 1978). Its oral availability in humans is about 80% (Vergin et al. 1985). Unfortunately, only limited information on the tissue distribution of ambroxol is available. In a study performed by Kubo et al. (1981), 14C‐labeled ambroxol was administered to rats, and the tissue distribution of radioactivity was assessed. At 3 h after oral administration of [14C]ambroxol, radioactivity was found mainly in intestines, liver, kidneys, and lungs. Plasma half‐life of radioactivity was 13 h in this study. A more recent publication reported peak plasma levels of ambroxol at 0.5 h after oral administration to rats, and a mean residence time of 2 h (Miyazaki et al. 2005).

In humans, maximal plasma levels of ambroxol were observed at 2 h after oral administration of the drug, and its mean residence time was 6.8 h (Vergin et al. 1985). Ambroxol was shown to accumulate in human lung tissue. Its levels in lungs were 20 times higher than those in plasma (Mezzetti et al. 1990).

Metabolism and excretion of ambroxol vary among species. Its plasma levels in rats and humans were compared by Gaida et al. (2005). Plasma levels in either species increased linearly with the dose. To obtain the same plasma levels much higher doses of ambroxol had to be administered to rats, compared to humans. The highest recommended clinical dose of ambroxol is 1000 mg per patient (i.e., approximately 15 to 20 mg/kg body weight by intravenous infusion). In rats, however, 1000 mg/kg had to be administered to obtain comparable plasma levels. After oral administration of ambroxol at doses of 30 to 1000 mg/kg to rats, plasma levels ranged from 0.13 to 3.2 mg/L. In humans, total doses of 30 to 1000 mg of the drug produced plasma levels of 0.11 to 2.1 mg/L. These findings explain why relatively high doses of ambroxol had to be used in rodent studies to observe the beneficial effects of the drug (Burgard et al. 2004; Gaida et al. 2005).

Because the available pharmacokinetic data do not permit a conclusion that ambroxol passes blood‐brain barrier, we compared below its side effects with those of other Na+ channel blockers.

Toxicology

The toxicology of ambroxol was thoroughly investigated in rats, mice, and rabbits. The acute oral toxicity of ambroxol was low: LD50 values after acute administration were about 10 g/kg in rats, and 3 g/kg in mice or rabbits. In general, all species suffered from accelerated breathing and convulsions as signs of acute toxicity, and these symptoms were mostly independent of the route of administration. In dogs, by oral administration, ambroxol induced ataxia and convulsions at doses between 500 and 2000 mg/kg (Püschmann and Engelhorn 1978; Tsunenari et al. 1981).

Convulsions are generally regarded as indicators of CNS toxicity. Animal experiments investigating the toxicity of systemically administered local anesthetics demonstrated that tremors and convulsions were typical symptoms of intoxication, they preceded generalized CNS depression, which resulted in hypoventilation and respiratory arrest (Groban 2003; Liu et al. 1983).

Thus, it can be concluded that ambroxol—at least in laboratory animals, and at very high doses—can enter the CNS. To test whether ambroxol affects CNS functions in rats the drug was administered orally, at analgesic doses of 300, or 1000 mg/kg, as well as placebo, to instrumented animals, and their nocturnal locomotor activity was studied by telemetry. It was found that even at the highest administered dose ambroxol did not affect locomotion, suggesting that at analgesic doses the drug does not cause central effects (unpublished results).

Clinical Experience

Ambroxol has been first marketed in 1979, and is currently available in many countries. Ambroxol lozenges for the treatment of sore throat are available since 2002. For the treatment of mild diseases of the respiratory tract single doses of 20 to 75 mg are used. In addition to these indications ambroxol is used in the treatment of infant respiratory dystress syndrome where it is administered prenatally, and in the treatment of acute respiratory dystress syndrome as intravenous infusion (1 g per day, infused over 4 h, usually for 5 days). Due to its good safety profile, ambroxol has been administered at doses up to 3 g per day for 53 days or used at oral doses of 1.3 g per day for 33 days (Chiara et al. 1983; Kimya et al. 1995; Luerti et al. 1987; Schillings and Probst 1992).

Up to now, however, convulsions as consequence of ambroxol treatment have not been reported in humans, although at a high dose ambroxol has been administered for over 3000 patient‐years (unpublished data, on file at Boehringer‐Ingelheim). In contrast to other Na+ channel blockers, like mexiletine or bupivacaine, no drug‐induced fatalities have been observed with ambroxol (although its potency for Na+ channel block, as well as the intravenously administered doses are high, compared to other Na+ channel blockers). As shown above, ambroxol also potently inhibits Ca2+ channels without causing typical CNS‐related effects reported for a blocker of central N‐type (Cav2.2) Ca2+ channels. This suggests that ambroxol does not enter CNS at clinically relevant concentrations, or that its brain levels are too low to cause relevant centrally mediated effects.

Conclusions

In addition to its effects on airways, ambroxol is a potent blocker of neuronal Na+ and Ca2+ channels, and blocks AMPA type glutamate receptors. In animal models, ambroxol effectively suppresses symptoms of chronic, inflammatory, and neuropathic pain. Toxicological experiments showed that ambroxol can cause CNS effects, but only at very high doses; such effects have not been observed in clinical praxis. Its effects on peripheral, pain‐sensing nerve fibers are sufficient to explain its analgesic effects upon local or systemic administration. Based on the currently available information, ambroxol is not expected to have CNS effects in humans at the clinically used doses, and should not be viewed as a CNS drug.

Conflict of Interest

The author is employed by Boehringer Ingelheim Corporation. Ambroxol was discovered at and has been manufactured by Dr. Karl Thomae GmbH, a division of Boehringer Ingelheim. The ambroxol patent is expired and the drug is available as a generic product from many different companies. The author has no financial interest in the production or distribution of ambroxol.

Acknowledgments

The skilful technical assistance by Rosi Ewen, Stephan Kurtze, and Amelia Staniland is gratefully acknowledged.

The author is employed by Boehringer Ingelheim Corporation. Ambroxol was discovered at and has been manufactured by Dr. Karl Thomae GmbH, a division of Boehringer Ingelheim. The ambroxol patent is expired and the drug is available as a generic product from many different companies. The author has no financial interest in the production or distribution of ambroxol.

References

- Burgard EC, Thor KB, Fraser MO (2004) Methods of treating lower urinary tract disorders using sodium channel modulators. US patent US 2004/0209960A1 .

- Canning BJ, Mazzone SB, Meeker SN, Mori N, Reynolds SM, Undem BJ (2004) Identification of the tracheal and laryngeal afferent neurones mediating cough in anaesthetized guinea‐pigs. Physiology 557: 543–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Perez‐Reyes E, Snutch TP, Striessnig J (2005) International Union of Pharmacology. XLVIII. Nomenclature and structure‐function relationships of voltage‐gated calcium channels. Pharmacol Rev 57: 411–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cegla UH (1988) Long‐term therapy over 2 years with ambroxol (Mucosolvan) retard capsules in patients with chronic bronchitis. Results of a double‐blind study of 180 patients. Prax Klin Pneumol 42: 715–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara O, Bevilacqua G, Padalino P, Guadalupi P, Bigatello L, Nespoli A (1983) The prevention of postoperative ARDS. Double‐blind clinical testing about the effects of ambroxol on pulmonary gas exchange. Urg Chir Comment 6: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen H, Hermansen F, Groth S, Mølgaard F (1987) Mucociliary clearance in early simple chronic bronchitis. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl 153: 145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg J, Jayamanne A, Vaughan CW, Aslan S, Thomas L, Mould J, Drinkwater R, Baker MD, Abrahamsen B, Wood JN, et al. (2006) μO‐conotoxin MrVIB selectively blocks Nav1.8 sensory neuron specific sodium channels and chronic pain behavior without motor deficits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 17030–17035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix K, Pairet M, Zimmermann R (1996) The antioxidative activity of the mucoregulatory agents: Ambroxol, bromhexine and N‐acetyl‐L‐cysteine. A pulse radiolysis study. Life Sci 59: 1141–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante FM, Paggioli J, Cherukuri S, Arthur GR (1996) The analgesic response to intravenous lidocaine in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Anesth Analg 82: 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer J, Pschorn U, Vix JM, Peil H, Aicher B, Muller A, De Mey C (2002) Efficacy and tolerability of ambroxol hydrochloride lozenges in sore throat. Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials regarding the local anesthetic properties. Arzneimittelforschung (Drug Research) 52: 256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaida W, Klinder K, Arndt K, Weiser T (2005) Ambroxol, a Nav1.8‐preferring Na+ channel blocker, effectively suppresses pain symptoms in animal models of chronic, neuropathic and inflammatory pain. Neuropharmacology 49: 1220–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs BF, Schmutzler W, Vollrath IB, Brosthardt P, Braam U, Wolff HH, Zwadlo‐Klarwasser G (1999) Ambroxol inhibits the release of histamine, leukotrienes and cytokines from human leukocytes and mast cells. Inflamm Res 48: 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillissen A, Bartling A, Schoen S, Schultze‐Werninghaus G (1997) Antioxidant function of ambroxol in mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells in vitro. Lung 175: 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groban L (2003) Central nervous system and cardiac effects from long‐acting amide local anesthetic toxicity in the intact animal model. Reg Anesth Pain Med 28: 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer R, Bozler G, Jauch R, Koss FW, Hadamovsky H (1978) Ambroxol, comparative studies of pharmacokinetics and biotransformation in rat, rabbit, dog and man. Arzneimittelforschung (Drug Research) 28: 899–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan QH (2007) Role of decreased sensory neuron membrane calcium currents in the genesis of neuropathic pain. Croat Med J 48: 9–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis B, Coukell AJ (1998) Mexiletine. A review of its therapeutic use in painful diabetic neuropathy. Drugs 56: 691–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang YY, Song JH, Shin YK, Han ES, Lee CS (2003) Depressant effects of ambroxol and erdosteine on cytokine synthesis, granule enzyme release, and free radical production in rat alveolar macrophages activated by lipopolysaccharide. Pharmacol Toxicol 92: 173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MF, Honore P, Shieh CC, Chapman M, Joshi S, Zhang XF, Kort M, Carroll W, Marron B, Atkinson R, et al. (2007) A‐803467, a potent and selective Nav1.8 sodium channel blocker, attenuates neuropathic and inflammatory pain in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 8520–8525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Dong H, Lam JK, Giesz S, Janke D, Khawaja A, Mezeyova J, Parker DB, Arneric SP, Snutch TP, Belardetti F (2006) Ambroxol block of voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels. Soc Neurosci Abstr 333.16 .

- Kim YK, Jang YY, Han ES, Lee CS (2002) Depressant effect of ambroxol on stimulated functional responses and cell death in rat alveolar macrophages exposed to silica in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 300: 629–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimya Y, Kucukkomurcu S, Ozan H, Uncu G (1995) Antenatal ambroxol usage in the prevention of infant respiratory distress syndrome – beneficial and adverse effects. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 22: 204–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klier KF, Papendick U (1977) The local anesthetic effect of NA872‐containing eyedrops. Med Monatsschr 31: 575–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo J, Tanabe H, Yamamoto M, Yamagushi H, Hashimoto Y (1981) Metabolic fate on NA‐872. 2. distribution after single or repeated administration in the rat. Iyakuhin Kenkyu 12: 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Lai J, Gold MS, Kim CS, Bian D, Ossipov MH, Hunter JC, Porreca F (2002) Inhibition of neuropathic pain by decreased expression of the tetrodotoxin‐resistant sodium channel, Nav1.8. Pain 95: 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PL, Feldman HS, Giasi R, Patterson MK, Covino BG (1983) Comparative CNS toxicity of lidocaine, etidocaine, bupivacaine, and tetracaine in awake dogs following rapid intravenous administration. Anesth Analg 62: 375–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas SM, Rothwell NJ, Gibson RM (2006) The role of inflammation in CNS injury and disease. Br J Pharmacol 147 Suppl 1: S232–S240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luerti M, Lazzarin A, Corbella E, Zavattini G (1987) An alternative to steroids for prevention of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS): Multicenter controlled study to compare ambroxol and betamethasone. J Perinat Med 15: 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone SB, Mori N, Canning BJ (2005) Synergistic interactions between airway afferent nerve subtypes regulating the cough reflex in guinea‐pigs. J Physiol 569: 559–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzetti M, Colombo L, Marini MG, Crusi V, Pierfederici P, Mussini E (1990) A pharmacokinetic study on pulmonary tropism of ambroxol in patients under thoracic surgery. J Emerg Surg Intensive Care 13: 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S, Kubo W, Itoh K, Konno Y, Fujiwara M, Dairaku M, Togashi M, Mikami R, Attwood D (2005) The effect of taste masking agents on in situ gelling pectin formulations for oral sustained delivery of paracetamol and ambroxol. Int J Pharm 297: 38–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobata K, Fujimura M, Ishiura Y, Myou S, Nakao S (2006) Ambroxol for the prevention of acute upper respiratory disease. Clin Exp Med 6: 79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottonello L, Arduino N, Bertolotto M, Dapino P, Mancini M, Dallegri F (2003) In vitro inhibition of human neutrophil histotoxicity by ambroxol: Evidence for a multistep mechanism. Br J Pharmacol 140: 736–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Püschmann S, Engelhorn R (1978) Pharmacological study on the bromhexine metabolite ambroxol. Arzneimittelforschung (Drug Research) 28: 889–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerni L, Passali D (2003) Evaluation of efficacy of ambroxol effervescent tabs in the treatment of catarrhal diseases of upper respiratory tract: Controlled study vs N‐acetylcysteine. Riv Ital Otorinolaryngol Audiol Foniatr 23: 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Schillings GJ, Probst J (1992) Ambroxol in the treatment of ARDS in polytraumatised patients – A report. Klinikarzt 21: 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Schutz A, Gund HJ, Pschorn U, Aicher B, Peil H, Muller A, De Mey C, Gillissen A (2002) Local anesthetic properties of ambroxol hydrochloride lozenges in view of sore throat. Clinical proof of concept. Arzneimittelforschung (Drug Research) 52: 194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs RS, Fox AP (1992) Calcium current variation between acutely isolated adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons of different size. J Physiol 445: 639–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifart C, Clostermann U, Seifart U, Müller B, Vogelmeier C, Von Wichert P, Fehrenbach H (2005) Cell‐specific modulation of surfactant proteins by ambroxol treatment. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 203: 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetinová V, Herout V, Kvetina J (2004) In vitro and in vivo antioxidant activity of ambroxol. Clin Exp Med 4: 152–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X, Wang L, Song Y, Bai C (2004) Inhibition of inflammatory responses by ambroxol, a mucolytic agent, in a murine model of acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide. Intensive Care Med 30: 133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoki J, Chiyotani A, Yamauchi F, Takeuchi S, Takizawa T (1991) Ambroxol inhibits Na+ absorption by canine airway epithelial cells in culture. J Pharm Pharmacol 43: 841–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunenari Y, Kast A, Honma M, Nishikawa J, Shibata T (1981) Toxicity studies with ambroxol (Na 872) in rats, mice and rabbits. Pharmacometrics 21: 281–311. [Google Scholar]

- Vergin H, Bishop‐Freudling GB, Miczka M, Nitsche V, Strobel K, Matzkies F (1985) The pharmacokinetics and bioequivalence of various dosage forms of ambroxol. Arzneimittelforschung (Drug Research) 35: 1591–1595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace MS (2006) Ziconotide: A new nonopioid intrathecal analgesic for the treatment of chronic pain. Expert Rev Neurother 6: 1423–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser T (2000) The secretolytic ambroxol blocks neuronal Na+ channels. Soc Neurosci Abstr 454.14. [Google Scholar]

- Weiser T (2006) Comparison of the effects of four Na+ channel analgesics on TTX‐resistant Na+ currents in rat sensory neurons and recombinant Nav1.2 channels. Neurosci Lett 395: 179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser T, Brenner M, Palluk R, Bechtel WD, Ceci A, Brambilla A, Ensinger HA Sagrada A, Wienrich M (1999a) BIIR 561 CL: A novel combined antagonist of AMPA receptors and voltage‐dependent sodium channels with anticonvulsive and neuroprotective properties. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 289: 1343–1349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser T, Qu Y, Catterall WA, Scheuer T (1999b) Differential interaction of R‐mexiletine with the local anesthetic receptor site on brain and heart sodium channel alpha‐subunits. Mol Pharmacol 56: 1238–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser T, Wilson N (2002) Inhibition of tetrodotoxin (TTX)‐resistant and TTX‐sensitive neuronal Na(+) channels by the secretolytic ambroxol. Mol Pharmacol 62: 433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdicombe J (2006) Reflexes from the lungs and airways: Historical perspective. J Appl Physiol 101: 628–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienrich M, Palluk R, Brenner M, Walland A, Pieper M, Löscher W, Weiser T (2001) In vivo pharmacology of BIIR 561 CL, a novel combined antagonist of AMPA receptors and voltage‐dependent sodium channels. Br J Pharmacol 133: 789–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura N, Seki S, Novakovic SD, Tzoumaka E, Erickson VL, Erickson KA, Chancellor MB, De Groat WC (2001) The involvement of the tetrodotoxin‐resistant sodium channel Na(v)1.8 (PN3/SNS) in a rat model of visceral pain. J Neurosci 21: 8690–8696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipp F, Aktas O (2006) The brain as a target of inflammation: Common pathways link inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci 29: 518–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]