Abstract

Background

Survivors of critical illness often experience a multitude of problems that begin in the intensive care unit (ICU) or present and continue after discharge. These can include muscle weakness, cognitive impairments, psychological difficulties, reduced physical function such as in activities of daily living (ADLs), and decreased quality of life. Early interventions such as mobilizations or active exercise, or both, may diminish the impact of the sequelae of critical illness.

Objectives

To assess the effects of early intervention (mobilization or active exercise), commenced in the ICU, provided to critically ill adults either during or after the mechanical ventilation period, compared with delayed exercise or usual care, on improving physical function or performance, muscle strength and health‐related quality of life.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL. We searched conference proceedings, reference lists of retrieved articles, databases of trial registries and contacted experts in the field on 31 August 2017. We did not impose restrictions on language or location of publications.

Selection criteria

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs that compared early intervention (mobilization or active exercise, or both), delivered in the ICU, with delayed exercise or usual care delivered to critically ill adults either during or after the mechanical ventilation period in the ICU.

Data collection and analysis

Two researchers independently screened titles and abstracts and assessed full‐text articles against the inclusion criteria of this review. We resolved any disagreement through discussion with a third review author as required. We presented data descriptively using mean differences or medians, risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals. A meta‐analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of the included studies. We assessed the quality of evidence with GRADE.

Main results

We included four RCTs (a total of 690 participants), in this review. Participants were adults who were mechanically ventilated in a general, medical or surgical ICU, with mean or median age in the studies ranging from 56 to 62 years. Admitting diagnoses in three of the four studies were indicative of critical illness, while participants in the fourth study had undergone cardiac surgery. Three studies included range‐of‐motion exercises, bed mobility activities, transfers and ambulation. The fourth study involved only upper limb exercises. Included studies were at high risk of performance bias, as they were not blinded to participants and personnel, and two of four did not blind outcome assessors. Three of four studies reported only on those participants who completed the study, with high rates of dropout. The description of intervention type, dose, intensity and frequency in the standard care control group was poor in two of four studies.

Three studies (a total of 454 participants) reported at least one measure of physical function. One study (104 participants) reported low‐quality evidence of beneficial effects in the intervention group on return to independent functional status at hospital discharge (59% versus 35%, risk ratio (RR) 1.71, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.11 to 2.64); the absolute effect is that 246 more people (95% CI 38 to 567) per 1000 would attain independent functional status when provided with early mobilization. The effects on physical functioning are uncertain for a range measures: Barthel Index scores (early mobilization: median 75 control: versus 55, low quality evidence), number of ADLs achieved at ICU (median of 3 versus 0, low quality evidence) or at hospital discharge (median of 6 versus 4, low quality evidence). The effects of early mobilization on physical function measured at ICU discharge are uncertain, as measured by the Acute Care Index of Function (ACIF) (early mobilization mean: 61.1 versus control: 55, mean difference (MD) 6.10, 95% CI ‐11.85 to 24.05, low quality evidence) and the Physical Function ICU Test (PFIT) score (5.6 versus 5.4, MD 0.20, 95% CI ‐0.98 to 1.38, low quality evidence). There is low quality evidence that early mobilization may have little or no effect on physical function measured by the Short Physical Performance Battery score at ICU discharge from one study of 184 participants (mean 1.6 in the intervention group versus 1.9 in usual care, MD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐1.10 to 0.50), or at hospital discharge (MD 0, 95% CI ‐1.00 to 0.90). The fourth study, which examined postoperative cardiac surgery patients did not measure physical function as an outcome.

Adverse effects were reported across the four studies but we could not combine the data. Our certainty in the risk of adverse events with either mobilization strategy is low due to the low rate of events. One study reported that in the intervention group one out of 49 participants (2%) experienced oxygen desaturation less than 80% and one of 49 (2%) had accidental dislodgement of the radial catheter. This study also found cessation of therapy due to participant instability occurred in 19 of 498 (4%) of the intervention sessions. In another study five of 101 (5%) participants in the intervention group and five of 109 (4.6%) participants in the control group had postoperative pulmonary complications deemed to be unrelated to intervention. A third study found one of 150 participants in the intervention group had an episode of asymptomatic bradycardia, but completed the exercise session. The fourth study reported no adverse events.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence on the effect of early mobilization of critically ill people in the ICU on physical function or performance, adverse events, muscle strength and health‐related quality of life at this time. The four studies awaiting classification, and the three ongoing studies may alter the conclusions of the review once these results are available. We assessed that there is currently low‐quality evidence for the effect of early mobilization of critically ill adults in the ICU due to small sample sizes, lack of blinding of participants and personnel, variation in the interventions and outcomes used to measure their effect and inadequate descriptions of the interventions delivered as usual care in the studies included in this Cochrane Review.

Plain language summary

Early intervention (movement or active exercise) for critically ill adults in the intensive care unit

Review question

Does helping critically ill adults to move or exercise early in their stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) improve their ability to perform everyday activities such as walking, and the ability to perform daily self care on discharge from hospital? We reviewed the evidence for this question, to see if there are benefits to early exercise, including the amount of time spent in the ICU or hospital, muscle strength, feelings of well‐being, and also to see if there are harms, such as the occurrence of falls. The movement or exercise could include things such as moving in, or sitting out of bed, practicing standing up, walking, arm exercises, and self‐care activities such as eating or brushing hair.

Background

Adults who are critically ill, and spend time in an ICU, can develop muscle weakness and other problems. This can occur because of the illness that led to their admission to the ICU, treatments associated with this illness, the impact of ongoing health conditions, and their lack of movement while in the ICU. They may also have ongoing problems when they leave ICU (or hospital) such as having trouble doing daily activities (for example dressing, bathing and mobility); feeling depressed or anxious and having difficulty returning to work.

We wanted to evaluate if assisting these people to move early in their ICU stay would allow them to be better able to look after themselves, be stronger and feel better about life.

Study characteristics

We found four studies that included a total of 690 adults who had been in the ICU. Patients were randomized to receive exercises and assistance to move early in their stay in the ICU or to usual care. All participants had been on a breathing machine at some point during their time in the ICU. Three studies included adults with critical illness involving severe disease of the lungs or severe body response to infection and one study involved adults who had undergone cardiac surgery.

Study funding sources

One study was funded by the Intensive Care Foundation, Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Australia and the investigator was supported by a Postgraduate Award from Singapore.

Key results

We were unable to determine whether early movement or exercise of critically ill people in the ICU improves their ability to do daily activities, muscle strength, or quality of life. There were mixed results on the effect of early movement or exercise on physical function. One study found that on some measures of physical function, participants who received the intervention could get out of bed earlier and walk greater distances. However, the same study found no differences in the number of daily activities they could do when leaving ICU. Early movement or exercise appears safe as the number of adverse events was very low. There was no difference between groups in time spent in hospital, muscle strength or death rates.

Quality of the evidence

Overall there was low‐quality evidence from these studies. The main reasons were that only a small number of studies have examined this intervention. Most studies included only a small number of participants, and participants and study staff were aware of group assignment. In addition, in two studies, staff assessing outcomes were aware of group assignment. There were also differences in participant diagnoses, interventions and the way that outcomes were measured. The four studies awaiting classification, and the three ongoing studies may alter the conclusions of the review once these results are available.

Currency of the evidence

Evidence in this review is current to August 2017.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Early intervention (mobilization or active exercise) versus usual care for critically ill adults.

| Early intervention (mobilization or active exercise) versus usual care for critically ill adults | ||||||

|

Patient or population: critically ill, mechanically ventilated adults

Settings: general, medical or surgical ICU in Australia/China/USA

Intervention: early intervention (mobilization or active exercise) Control: usual care (defined as no mobilization/active exercise while in ICU, or mobilization/active exercise given later than the intervention group) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Early intervention (mobilization or active exercise) | |||||

| Physical function ‐ return to independent functional status at hospital discharge Defined as ability to perform 6 ADLs (bathing, dressing, eating, grooming, transferring from bed to chair, using the toilet) and walk independently, measured with Functional Independence Measure | Study population | RR 1.71 (1.11 to 2.64) | 104 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 345 per 1000 | 591 per 1000 (383 to 912) | |||||

| Physical function ‐ independent ADLs total at ICU discharge Functional Independence Measure (0 ‐ 6) | Study population | 104 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |||

| Median 0 (IQR 0 to 5) | Median 3 (IQR 0 to 5) | |||||

| Physical function ‐ Independent ADL total at hospital discharge Functional Independence Measure (0 ‐ 6) | Study population | 104 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |||

| Median 4 (IQR 0 to 6) | Median 6 (IQR 0 to 6) | |||||

|

Physical function Barthel score (0 ‐ 100) |

Study population | 104 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |||

| Median 55 (IQR 0 to 85) | Median 75 (IQR 7.5 to 95) | |||||

| Physical performance Acute Care Index of Function score at ICU discharge (0 ‐ 100) | Study population | 42 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | |||

| Mean score 55.0 (45.0 to 65.0) | Mean score 61.1 (46.2 to 76.0) MD 6.10 (‐11.85 to 24.05) |

|||||

|

Physical performance Physical Function ICU Test score at ICU discharge |

Study population | 42 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | |||

| Mean score 5.4 (4.7 to 6.1) | Mean score 5.6 (4.7 to 6.5) MD 0.20 (‐0.98 to 1.38) |

|||||

|

Physical performance Short Physical Performance Battery score at ICU discharge |

Study population | 184 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | |||

| Mean score 1.9 (1.3 to 2.4) | Mean score 1.6 (1.0 to 2.2) MD ‐0.30 (‐1.10 to 0.50) |

|||||

|

Physical performance Short Physical Performance Battery score at hospital discharge |

Study population | 204 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | |||

| Mean score 4.7 (4.0 to 5.4) | Mean score 4.7 (4.0 to 5.4) MD 0 (‐1.00 to 0.90) |

|||||

|

Adverse events Proportion of participants with one or more events, or proportion of intervention sessions where an event occurred (falls, accidental dislodgement of attachments, haemodynamic instability, oxygen desaturation or any other adverse events defined by study authors) |

One study reported that in the intervention group 1/49 (2%) experienced oxygen desaturation < 80% and 1/49 (2%) had accidental dislodgement of the radial catheter. This study also found cessation of therapy due to patient instability occurred in 19/498 (4%) of the intervention sessions. In another study 5/101 (5%) of the intervention group and 5/109 (4.6%) of the control group had postoperative pulmonary complications. These were deemed to be unrelated to intervention. A third study found 1/150 in the intervention group had an episode of asymptomatic bradycardia, but completed the exercise session. The fourth study reported no adverse events. | 690 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ADLs: activities of daily living; CI: confidence interval; ICU: intensive care unit; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Downgraded one point for high risk of bias. Risk of bias was high for blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias). 2Downgraded for imprecision (only one small study). 3Downgraded one point for high risk of bias. Risk of bias was high for blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) and incomplete outcome data (attrition bias; for all outcomes except mortality). 4Downgraded for imprecision, as there were very few adverse events of each type.

Background

Description of the condition

Critically ill patients are admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) so that physiological responses to illness and injury can be monitored and stabilised in a sophisticated manner, and respiration can be assisted with mechanical ventilation if needed. Multiple factors, including haemodynamic instability, altered sleep patterns, the presence of vascular attachments and sedation to improve patient comfort during mechanical ventilation, can limit mobilization of these patients (Adler 2012).

Intensive care unit‐acquired weakness (ICUAW) may be described as clinically identified weakness that develops during an ICU admission with no other known cause except the acute illness or its treatment (Hermans 2015). ICUAW is a common complication for critically ill patients and is associated with extended duration of mechanical ventilation (DeJonghe 2002), sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, multi‐organ failure and hyperglycaemia (Desai 2011). Incidence of ICUAW in this patient population has been found to be as high as 46% (95% CI 43% to 49%) (Stevens 2007). Critically ill patients can sustain loss of muscle mass within the first week of admission to the ICU (Parry 2015a; Puthucheary 2013). ICUAW has also been associated with worse acute outcomes, higher healthcare‐related costs, and the persistence of weakness is associated with a higher mortality one year after ICU admission (Hermans 2014a). The long‐term weakness appears to result from heterogeneous muscle pathophysiology, with both muscle atrophy and decreased contractile capacity involved (Dos Santos 2016).

Among critically ill patients in ICU, some may have or develop acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome (Herridge 2005). Patients with acute lung injury demonstrate rapid onset of infiltrates in bilateral lungs and mild to moderate hypoxaemia of noncardiac origin (Herridge 2005). In a two‐year follow‐up on people with this condition, the presence of ICUAW was associated with impairments in physical function; six‐minute walk distance (Crapo 2002), and the physical function subscale scores of the Short F‐36 survey (Ware 1992), were significantly lower (52% to 69% of predicted value) at six, 12 and 24 months' follow‐up (Fan 2014). ICUAW has also been related to a higher incidence of hospital mortality (Ali 2008), and the persistence of weakness is associated with a higher mortality one year after ICU admission (Hermans 2014a).

The term 'post‐intensive care syndrome' was developed to describe new or residual problems that are often experienced by survivors of critical illness. These include cognitive impairments (such as altered memory, attention and executive functioning); psychological difficulties (such as depression, anxiety and post‐traumatic stress disorder) and physical impairments in pulmonary, neuromuscular and physical function (Needham 2012). These problems can affect the performance of activities of daily living (ADLs) and lead to decreased quality of life for these people. In addition, similar psychological difficulties may occur in families of people with critical illness (Needham 2012).

In an attempt to improve outcomes for the survivors of critical illness, there have been efforts to interrupt sedation (Kress 2000), to allow patients to choose their own level of sedation (Chlan 2010), and to cease sedation (Strøm 2011), for patients who are mechanically ventilated. As patients become increasingly responsive, they are better able to participate in active exercise and to mobilize outside of bed, even when mechanically ventilated. Bailey 2007, demonstrated infrequent adverse events in participants who mobilized while mechanically ventilated and concluded that early mobility of patients in the ICU is feasible and safe. To assist in the assessment of patient readiness and appropriateness to commence early mobility in the ICU, a panel of multidisciplinary experts reached consensus on safety recommendations concerning respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological, medical or surgical and other factors (Hodgson 2014).

Description of the intervention

We considered interventions that commenced earlier than the intervention received by the control group while the patient was in the ICU and may have included any of the following activities.

Cycle ergometer: (a stationary cycle where work intensity can be adjusted by varying pedal resistance and cycling rate)

Active‐assisted exercises (exercises performed by the participant with manual assistance of another person)

Active range‐of‐motion exercises (exercises moving a joint(s) through its range of motion, that are performed independently by the participant)

Bed mobility activities (activities including rolling, bridging and transfer to upright sitting)

ADLs (self‐care tasks such as eating, bathing, dressing and toileting)

Transfer training (repetition of transfers such as sitting to standing and bed to chair or commode)

Pre‐gait exercises (improving postural stability, static and dynamic balance and marching on the spot)

Ambulation (gait training and walking with or without mobility aids).

(See Types of interventions for additional details.)

Characteristics of the intervention such as type, provider skills and training, timing of delivery, dose/duration, tailoring and progression of intervention, and resources used in the delivery can greatly influence an intervention's efficacy as well as the heterogeneity of the population receiving the intervention. Evaluation of the impact of the intervention across studies is dependent on adequate reporting in the included studies so that variations in its delivery may be identified and analysed. To facilitate understanding of the components of the interventions across studies, we used the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist to report intervention details (see Table 2).

1. Characteristics of each intervention ‐ summarized using TIDieR criteria*.

| Item | Morris 2016 | Kayambu 2015 | Patman 2001 | Schweickert 2009 |

| Brief name | Standardized rehabilitation therapy | Early physical rehabilitation in ICU | Physiotherapy | Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients |

|

What

(Materials and Procedures) |

3 exercise types:

Both the physiotherapy and resistance training targeted lower extremity functional tasks and ADLs. See trial protocol (supplement to article) for more details. |

Specific equipment not reported. Procedures mentioned include: arm or leg ergometry; passive, active and resisted ROM exercises; bed mobility activities; sitting and standing balance exercises; transfer training; pre‐gait exercises; ambulation with assistance; electrical muscle stimulation; and Tilt table |

Specific equipment was not reported. Procedures mentioned include: positioning; manual hyperinflation; endotracheal suctioning; thoracic expansion exercises; and upper limb exercises |

Specific equipment was not reported. Procedures mentioned included: passive, active‐assisted and active ROM exercises; bed mobility activities; sitting balance exercises; ADL exercises to promote increased independence with functional tasks; transfer training; pre‐gait exercises; and ambulation |

| Who provided | Physiotherapist, ICU nurse, and nursing assistant | ICU research physiotherapist | Team of physiotherapists under the guidance of the principal investigator | An occupational therapist and a physical therapist |

| Where | One medical ICU, Medical Centre, North Carolina, USA | Quaternary‐level general ICU, Australia | Surgical ICU, Perth, Australia |

Two medical ICUs: Chicago, USA and Iowa City, USA |

| When and how much | 3 separate sessions every day of hospitalization for 7 days per week, from enrolment through to hospital discharge | 30 min 1‐2 times/day within 48 h of diagnosis of sepsis until discharge from the ICU |

1‐2 interventions during the first 24 h of mechanical ventilation |

Interventions were synchronized with daily interruption of sedation. Each morning within 48‐72 h of intubation until return to previous level of function or discharge from the ICU |

| Tailoring and progression | The participant's level of consciousness determined whether they were considered suitable to receive the physiotherapy or progressive resistance exercise, as did their ability to complete the exercises. When participants were unconscious, the 3 sessions consisted of passive ROM. As consciousness was gained, physiotherapy and progressive resistance exercise was commenced. Participants did not need to be free of mechanical ventilation to begin any of the exercise sessions | Interventions were tailored, planned, administered and progressed at the discretion of the physiotherapist, participant acuity of illness and level of co‐operation |

Not reported | Progression of interventions depended on participant tolerance and stability. |

|

Modification of intervention throughout trial |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

|

Fidelity (strategies to improve) |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

|

Fidelity (extent) |

The mean percentage of study days that participants received therapy was 87.1% (SD 18.4%) for passive ROM; 54.6% (SD 27.2%) for physiotherapy; and 35.7% (SD 23%) for progressive resistive exercise. The median days of delivery of therapy per participant was 8.0 (IQR, 5.0‐14.0) for passive ROM, 5.0 (IQR, 3.0‐8.0) for physiotherapy, and 3.0 (IQR, 1.0‐5.0) for progressive resistance exercise | All participants adhered and remained enrolled for an average of 11.4 days. No further details. |

Not reported | Therapy occurred on 87% of the days on the study for all participants in the intervention group and on 95% of the days on the study for 22/55 (40%) of participants in the control group |

*See Hoffmann 2014 for TIDieR criteria

ADLs: activities of daily living; ICU: intensive care unit; ROM: range of motion

How the intervention might work

The consequences of bed rest are well documented and include adverse effects on the cardiovascular system (through decreased functional capacity), the respiratory system (through difficulty weaning from mechanical ventilation) and the neuromuscular system (through ICUAW) (Koo 2011). Beneficial effects of exercise training are widespread and can include improvements in skeletal muscle function, respiration (increased tidal volume and oxygen transport capacity) and cardiovascular function (including prevention of age‐related diastolic dysfunction and decreased oxidative stress) (Gielen 2010). Prolonged immobilization is one of the risk factors for ICUAW (Hermans 2015), and hence reducing the duration of immobilization has been suggested as one of the actions that can be taken to prevent it (Hermans 2015). It has been suggested that early mobilization might reduce muscle injury through its effect on muscle unloading (Hermans 2015), but the pathophysiological mechanisms through which this intervention might work are complex and not clearly understood. As the recovery from ICUAW can take weeks or months, its impact on function and quality of life can last for years. In a five‐year follow‐up study of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome, generalized weakness and fatigue were chief complaints and still present in many survivors at this time (Herridge 2011). Hence preventing or lessening the impact of ICUAW may have consequent effects on patients’ function and quality of life in the weeks, months, and years following an ICU admission.

Why it is important to do this review

A Cochrane protocol for a systematic review (Greve 2012), and one Cochrane systematic review (Connolly 2015), relevant to the impact of mobilization of critically ill patients have been published. Greve 2012, has a focus on preventing ICU delirium and will assess the impact of any multicomponent (behavioural, cognitive, psychological, physical training) or pharmacological interventions, or both. Connolly 2015, evaluated the efficacy of exercise rehabilitation or training for functional exercise capacity and health‐related quality of life in adult ICU survivors who had been mechanically ventilated longer than 24 hours. However, neither of these reviews plans to examine or has investigated mobilization delivered early in the participants' admission to ICU. The protocol (Greve 2012), has not specified the timing of the intervention while the systematic review (Connolly 2015), investigated the impact of exercise rehabilitation once participants had been discharged from the ICU.

Early mobilization and active exercise of critically ill patients are increasingly being provided in some ICUs. However, the effectiveness of early interventions that are being used is not clear. This review aims to guide clinicians and intensive care unit policy makers regarding the timing of mobilization and active exercise for critically ill patients.

Objectives

To assess the effects of early intervention (mobilization or active exercise), commenced in the ICU, provided to critically ill adults either during or after the mechanical ventilation period, compared with delayed exercise or usual care, on improving physical function and performance, muscle strength and health‐related quality of life.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs that compared early intervention (mobilization or active exercise) of critically ill participants either during or after the mechanical ventilation period in the ICU with delayed exercise or usual care (see Types of interventions).

Types of participants

We included adults who had been admitted to an ICU and were mechanically ventilated. We excluded studies with participants who had pre‐existing or rapidly developing neuromuscular disease, spinal cord injury, cardiopulmonary arrest, raised intracranial pressure, advanced dementia or irreversible disorders with expected six‐month mortality.

Types of interventions

Interventions

The intervention must have been conducted within the ICU and must have consisted of mobilization or active exercise, or both, that was designed to commence earlier than the care received by the control group.

We considered any combination of one or more of the following types of exercise modalities.

Cycle ergometer

Active‐assisted exercises

Active range‐of‐motion (ROM) exercises

Bed mobility activities (e.g. bridging, rolling, lying to sitting)

ADLs or exercises related to increasing independence with functional tasks

Transfer training

Pre‐gait exercises (including marching on the spot)

Ambulation

Any other type of active exercise modality that commenced while the participant was in the ICU

Comparators

The comparator may have consisted of:

delayed intervention (mobilization/active exercise the same as the intervention group, but given later, either in the ICU, or after the participant left the ICU);

usual care (no mobilization/active exercise while in ICU);

inspiratory/respiratory muscle training only.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Physical function (the ability to perform everyday activities such as basic ADLs) as measured by a validated scale (e.g. Barthel Index, Functional Independence Measure (FIM)) or physical performance tasks (as measured by a scale such as the Physical Function ICU Test (PFIT), Acute Care Index of Functional Status (ACIF), Short Physical Performance Battery, walking tests)

Adverse events (falls, accidental dislodgement of attachments, haemodynamic instability, oxygen desaturation or any other adverse events defined by study authors)

Secondary outcomes

Length of stay (ICU and hospital)

Muscle strength (e.g. Medical Research Council (MRC) score (Medical Research Council 1942), cross‐sectional diameter, handgrip strength)

Health‐related quality of life or well‐being (e.g. The Medical Outcome Study (MOS) 36‐item Short‐Form Health Survey (SF‐36) questionnaire (Ware 1992)

Delirium

Death from any cause at any measured time point

Hospital costs

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 8) via the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (Ovid SP) (1946 to August week 4, 2017), Embase (Elsevier) (2010 to August 2017) and CINAHL (1981 to August 2017).

We used the search strategy described in Appendix 1 to search CENTRAL and Appendix 2 to search MEDLINE. We combined the MEDLINE search terms with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐and precision‐maximizing version (2008 revision); Ovid format (Lefebvre 2011). We adapted the search strategy to search Embase (see Appendix 3), and CINAHL (see Appendix 4).

We did not impose a language restriction.

Searching other resources

We searched the Controlled Trials registry www.controlled‐trials.com/ (August 2017) (see Appendix 5 for detailed search strategy), ClinicalTrials.gov registry clinicaltrials.gov/ (August 2017) (see Appendix 6), and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform www.who.int/ictrp/en/ (August 2017) (see Appendix 7), for studies that may have been missed or unpublished and reviewed relevant conference proceedings and abstract presentations of important symposia.

We corresponded with authors of studies that had been completed but not published and with content experts to identify unpublished research and trials still under way.

We did not impose a language restriction.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two researchers (review author, KAD and a research assistant) independently screened titles and abstracts and assessed full‐text articles that were identified from the search. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or consultation with a third review author (TCH or EMB, or both) as required.

Data extraction and management

Two researchers (KAD, and a research assistant) independently used the data collection form shown in our protocol (Doiron 2013), to extract data from all included studies. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or consultation with a third review author (EMB or TCH, or both) as required.

We examined trials that met the inclusion criteria and recorded the following information.

Methods: a description of study design, randomization and treatment setting

Participants: number of participants, age, gender, race/ethnicity, body mass index, inclusion and exclusion criteria, ICU days before inclusion, primary presenting diagnosis, biochemical data, health and well‐being status scores and functional scale scores

Interventions: description of experimental and comparator interventions and relevant co‐interventions (e.g. medications)

Outcomes: baseline and end of study measurement of functional status (e.g. functional independence measure (FIM) (Keith 1987), Barthel Index (Mahoney 1965)), health‐related quality of life or well‐being (the MOS 36‐item Short‐Form Health Survey (SF‐36) questionnaire (Ware 1992)), and muscle strength, as well as adverse events, length of stay (ICU and hospital), delirium, death from any cause and hospital costs

Notes: language of the study and any other information relevant to this review

We commented briefly about the reasons for exclusion of studies identified in the search strategy but not subsequently included.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (EMB and KAD) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third review author (TCH). We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains.

Allocation sequence generation

Concealment of allocation

Blinding of study participants and personnel

Incomplete outcomes data

Selective outcomes reporting

Other biases

We graded each potential source of bias as yes, no or unclear according to whether the potential for bias was high, low or unknown.

We considered a trial as having a high risk of bias if we assessed either of the domains of concealment of allocation or blinding of study participants and personnel as inadequate or unclear.

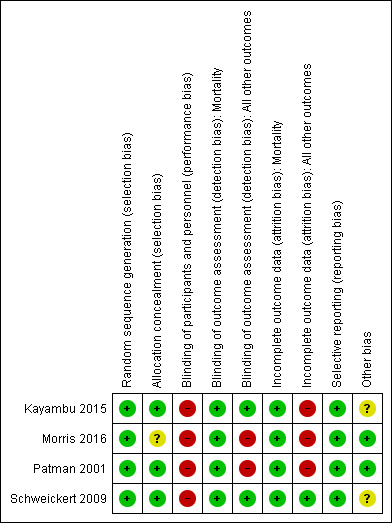

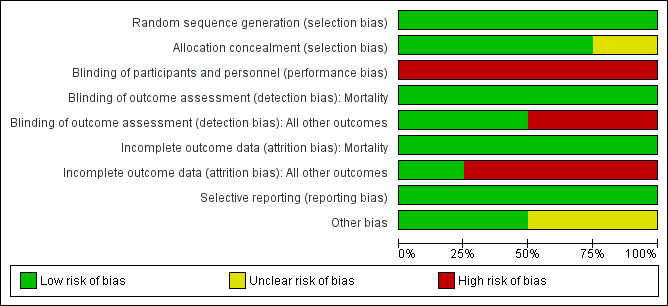

We included a 'Risk of bias' summary (see Figure 1), and a 'Risk of bias' graph (see Figure 2), as part of the Characteristics of included studies table, which detailed all of the judgements made for all included studies in the review.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Measures of treatment effect

Primary outcomes

Functional status

Where studies reported this as a dichotomous outcome (e.g. return to independent functional status at hospital discharge), we used a risk ratio to compare the intervention group with the control group. Where studies reported ADL composite measures and functional component measures using continuous scales (e.g. Barthel Index (Mahoney 1965)), we reported results using means (standard deviations (SDs)) or medians (interquartile range).

Adverse events

We reported the proportion of participants who experienced any adverse event that was reported by the study authors. We also descriptively reported the numbers of particular types of adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

Length of stay

This was reported in days, and we therefore reported the mean difference (MD) where possible, or the median (interquartile range) in each group.

Muscle strength, health‐related quality of life

These outcomes were measured using continuous scales and we reported the MD where possible, or the median (interquartile range) in each group.

Delirium

This was reported as days with delirium in the ICU and in hospital. We reported the median (interquartile range) scores in each group.

Death from any cause

This was reported as the percentage of participants in each group who died and reported as risk ratio to compare groups.

Hospital costs

None of the included studies reported this outcome. If they had done so, we planned to report the MD in costs between intervention and control groups.

Unit of analysis issues

Individual participants were the unit of analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We wrote to investigators to verify key study characteristics and details of the outcomes data as needed. We contacted a study author in Patman 2001, to identify group allocation for participants who died. We subsequently reported this information in Effects of interventions (death from any cause) and Table 3. We corresponded with authors in one study to identify the timing of the interventions received by the intervention and control groups (Kayambu 2015). We reported this information in Included studies (comparators). We also requested clarification on the methods used to calculate results from this study. We intended to conduct intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis and to impute missing standard deviations but this was not required.

2. Death/Survival.

| n (%) in intervention group | n (%) in control group | Risk ratio (95% CI) | P value | Reference of studies | |

| ICU mortality | 3/26 (12%) | 1/24 (4%) | RR 2.77 (0.31 to 24.85) |

0.36 | Kayambu 2015 |

| ICU mortality | 0/101 (0%) | 3/109 (2.8%) | RR 0.16 (0.008 to 3.03) |

0.22 | Patman 2001 |

| Hospital mortality | 9/49 (18%) | 14/55 (25%) | RR 0.72 (0.34 to 1.52) |

0.53 | Schweickert 2009 |

| 90‐day mortality | 8/26 (31%) | 2/24 (8%) | RR 3.69 (0.87 to 15.69) |

0.08 | Kayambu 2015 |

|

6‐month hospital‐free survival |

73/150 (48.7%) | 67/150 (44.7%) | RR 1.09 (0.86 to 1.39) |

0.69 | Morris 2016 |

CI: confidence interval; ICU: intensive care unit; n: number; RR: risk ratio

Assessment of heterogeneity

We noted clinical heterogeneity in studies relating to the participants, interventions, and outcome measures. We did not measure statistical heterogeneity as we did not perform a meta‐analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not create a funnel plot to investigate potential publication bias as only four studies were included in this review.

Data synthesis

If sufficient studies for meta‐analysis had been found, we planned to use a random‐effects model because of the varying nature of potential interventions in this review. However, as there were insufficient studies to perform a meta‐analysis, we descriptively reported the results of included studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If heterogeneity of studies had been observed, we planned to investigate possible sources of heterogeneity such as age group, cause of ICU stay, length of mechanical ventilation, comorbidities such as diabetes and use of corticosteroids using subgroup analyses. However, as there were insufficient studies identified, we reported these factors descriptively.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis by omitting the studies judged at high risk of bias, defined as lack of concealment of allocation and blinding of study participants and personnel. However we were unable to do this as no meta‐analysis was performed.

'Summary of findings' table and GRADE

We used the principles of the GRADE system (Guyatt 2008), to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with specific outcomes (functional status and adverse events) in our review and constructed Table 1 using the GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT 2015). The GRADE approach appraises the quality of a body of evidence based on the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. The quality of a body of evidence considers within‐study risk of bias (methodological quality), the directness of the evidence, the heterogeneity of the data, the precision of effect estimates and the risk of publication bias.

Two review authors (KAD and EMB) independently performed the GRADE assessment of quality of the evidence. We resolved disagreements by consensus. We planned to consult the third review author if we had been unable to resolve disagreements. We rated the quality of the evidence for each outcome as high, moderate, low or very low.

Results

Description of studies

We included RCTs that compared early intervention (mobilization or active exercise) commenced in the ICU (either during or after the mechanical ventilation period) with delayed exercise or usual care for critically ill adults.

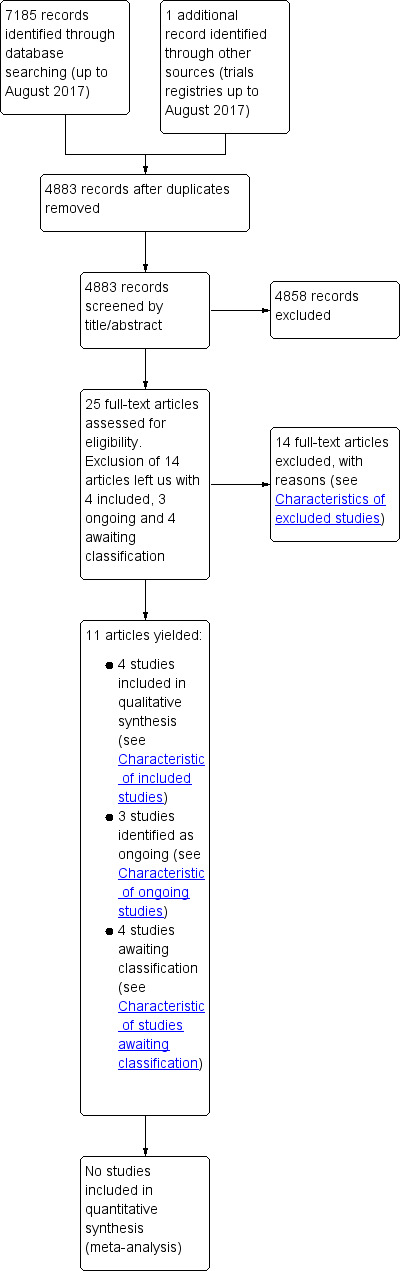

Results of the search

We identified a total of 7185 references from our searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE (Ovid SP), Embase (Ovid SP) and CINAHL, and one reference after searching trials registries (to August 2017). We identified 2303 duplicates and excluded 4858 further references as they were not eligible for this review. We examined 25 full‐text articles, and identified four studies that fulfilled our inclusion criteria (Kayambu 2015; Morris 2016; Patman 2001; Schweickert 2009). See Figure 3 for further information.

3.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

We included four RCTs in this review (Kayambu 2015; Morris 2016; Patman 2001; Schweickert 2009).

Participants

We report participant details in the Characteristics of included studies section. The total number of participants enrolled in all four trials was 690. All were aged over 18 years; the mean or median age of participants ranged from 56 to 62 years. Sample size varied across studies; Kayambu 2015 (50 participants), Morris 2016 (300 participants), Patman 2001 (236 participants), and Schweickert 2009 (104 participants).

One study reported that all participants in the intervention group were mechanically ventilated for the duration of the intervention (Patman 2001), while the remaining three studies did not report the percentages of those who were intubated during the intervention period (Kayambu 2015; Morris 2016; Schweickert 2009).

The most common reason for ICU admission varied across the studies. In Kayambu 2015, 19 of 26 (73%) participants in the intervention group and 17 of 24 (71%) in the control group were admitted with septic shock; in Morris 2016 68% had acute respiratory failure without chronic lung disease, 31% had acute respiratory failure with chronic lung disease and 2% had an ICU diagnosis of coma; in Patman 2001, 71 of 108 (66%) participants in the intervention group and 68 of 109 (62%) of those in the control group had undergone coronary artery surgery; and in Schweickert 2009 27 of 49 (55%) participants in the intervention group and 31 of 55 (56%) in the control group were admitted with acute lung injury.

Two studies were conducted in a single ICU (Kayambu 2015; Morris 2016), one study in a surgical ICU (Patman 2001), and one study in medical ICUs at two sites (Schweickert 2009).

Please refer to the Characteristics of included studies for more detail.

Interventions

There was variation in most aspects of the interventions between the four studies: electrical muscle stimulation (EMS), tilt table therapy, arm or leg ergometry and activities ranging from passive to active to resisted range‐of‐motion exercises, transfers, balance training (sitting and standing) through to ambulation with assistance were part of the intervention in Kayambu 2015; passive range‐of‐motion, physical therapy including bed mobility, transfer training and balance training, and progressive resistance exercise using elastic resistance bands were used in Morris 2016; upper limb exercises were performed with the intervention group in the trial by Patman 2001; and activities ranging from passive to active‐assisted exercises through to transfer training, ADL tasks and ambulation were implemented in Schweickert 2009.

The time to commencement of the intervention was variable across studies. in Kayambu 2015 the intervention group commenced therapy within 48 hours of admission to ICU and in Morris 2016 a median of 1 day after admission to ICU. In Patman 2001 the intervention group commenced therapy during the first 24 hours of intubation and in Schweickert 2009 at a median of 1.5 days, interquartile range (IQR) (1.0 to 2.1) after intubation had commenced.

Frequency and duration of the delivery of the intervention also varied across studies. Kayambu 2015 reported that the intervention was delivered for 30 minutes, once or twice per day until the participant was discharged from the ICU and that participants remained in the study for a mean of 11.4 days. In Morris 2016, the intervention sessions were given three times per day, with a goal of achievement of repetitions, rather than a specified time for each session. The intervention was continued until discharge from hospital. In the study by Patman 2001, the intervention was delivered as required during the intubated phase, which lasted 24 hours (participants were withdrawn from the study if mechanical ventilation was required for more than 24 hours). No further details regarding the frequency and duration of the intervention were provided. Schweickert 2009 reported that the intervention was delivered every morning until participants returned to their previous level of function or were discharged. Information on the discharge location (ICU or hospital) was not stated. Study authors reported that the median duration of therapy for the intervention group during mechanical ventilation was 0.32 hours per day, IQR (0.17 to 0.48) and a median of 0.21 hours per day IQR (0.08 to 0.33) while not being ventilated.

The intervention was provided by physiotherapists in Kayambu 2015, Morris 2016 and Patman 2001; and by a physiotherapist and an occupational therapist in Schweickert 2009. (Refer to the Characteristics of included studies for more detail.) Key characteristics of the interventions in each trial are listed in Table 2, according to the TIDieR components (Hoffmann 2014).

Comparators

Information about the timing of treatment in the control group was reported in three studies (Morris 2016, Patman 2001; Schweickert 2009). In Morris 2016, the usual care group participants could receive weekday physical therapy if it was ordered by the clinical team. This started a median of seven days after admission, compared with one day in the intervention group. The control group received physical therapy on a mean 11.7% of study days, compared with 87.1% in the intervention group. In Patman 2001, participants received the same intervention as those in the intervention group but 24 hours later (after they were extubated from mechanical ventilation). In Schweickert 2009, participants in the control group received physical and occupational therapy as ordered by the primary care team and active physiotherapy treatment occurred only after they had been mechanically ventilated for two weeks. Study authors reported that the control group received an intervention a median of 7.4 days after intubation. After correspondence with study authors, Kayambu 2015 reported that 10 of 24 (42%) participants in the control group received the same intervention as those in the intervention group (with the exception of EMS, tilt table therapy and arm or leg ergometry) at the same time as those in the intervention group (within 48 hours of admission) while 14 out of 24 (58%) of the participants in this group received it later (after 48 hours of admission).

Refer to the Characteristics of included studies for more detail.

Primary outcomes

Physical function and performance

Three studies measured physical function or performance, and each used different measures (Kayambu 2015; Morris 2016; Schweickert 2009). Kayambu 2015, used the acute care index of function (ACIF) (Van Dillen 1988), and the physical function ICU test (PFIT) (Skinner 2009), and Morris 2016 used the Short Physical Performance Battery score (SPPB). Schweickert 2009 reported the percentage of participants returning to independent functional status at discharge, the number of independent ADLs achieved at ICU and hospital discharge, the time from intubation to out of bed, standing, marching in place, transferring to a chair, and walking, and the Barthel Index. These study authors used the functional independence measure (FIM) (Keith 1987), to measure return to independent functional status and ADLs. Schweickert 2009 also measured time to achieve milestones (e.g. time from intubation to marching in place) and walking distance achieved at hospital discharge.

Adverse events

All studies reported adverse events but only two studies defined this outcome (Patman 2001; Schweickert 2009). Patman 2001 used the presence of four or more of the following criteria to identify the incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications: oral temperature greater than 38˚C, hypoxia (oxygen saturation < 92% on room air), abnormal findings on chest X‐ray reported by blinded experienced senior radiologists, abnormal white cell count (< 2 or > 10 x 109 cells per litre) and positive sputum culture on microscopy. Schweickert 2009 described adverse events as a fall to knees, endotracheal tube removal, systolic blood pressure more than 200 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg, and desaturation to less than 80% . In the protocol for their study, Kayambu 2015 reported that an adverse event checklist would be used to assist in clinical decisions regarding cessation or modification of the intervention but did not provide further details. Morris 2016 collected adverse events of any kind, and classified them by severity and likelihood of being related to the intervention sessions.

Secondary outcomes

Length of stay (LOS) ICU or hospital

This outcome was reported by all four included studies.

Muscle strength

Three studies reported muscle strength (Kayambu 2015; Morris 2016; Schweickert 2009). Kayambu 2015 at ICU discharge, Morris 2016 at ICU discharge, hospital discharge and at follow‐up visits, and Schweickert 2009 at hospital discharge. Kayambu 2015 and Schweickert 2009 used the Medical Research Council score (Medical Research Council 1942), to measure this outcome. Morris 2016 used dynamometer and hand grip strength; Schweickert 2009 measured hand‐grip strength and reported the incidence of ICUAW at hospital discharge.

Health‐related quality of life

THis outcome was reported by two studies. Kayambu 2015 used the 36‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36) questionnaire (Ware 1992), for 11 of 26 (42%) of the participants in the intervention group and 19 of 24 (79%) of the participants in the control group to measure physical function, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional and mental health at six months post‐hospital discharge. Morris 2016 used the SF‐36 physical health summary score and mental health summary scores at hospital discharge and follow‐up visits.

Delirium

Two studies reported the number of ICU days and the number of hospital days with delirium (Morris 2016; Schweickert 2009).

Death from any cause

All four included studies reported death from any cause using the percentage in the intervention group compared with the percentage in the control group. Kayambu 2015 and Patman 2001 reported ICU mortality, and Schweickert 2009 reported hospital mortality. Morris 2016 reported six‐month mortality and Kayambu 2015 reported 90‐day mortality.

Hospital costs

None of the included studies reported costs.

Funding

One study was funded by the Intensive Care Foundation and the principal investigator was supported by a postgraduate award from Singapore (Kayambu 2015); two studies did not report funding (Morris 2016; Patman 2001) and one study author declared that no funding was received (Schweickert 2009).

For further descriptive information, see Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded 14 studies for the reasons identified in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. These included study design, comparators and timing of the intervention between groups. One study was not a RCT (Morris 2008), one study was conducted in a respiratory care centre (not the ICU) (Chen 2012); four studies used comparators that did not match those in this review; active or passive ROM, or both (Burtin 2009); passive chair transfer (Collings 2015); active and passive mobilization (Médrinal 2013), and active intervention once versus twice per day (Yosef‐Brauner 2015). Seven studies did not compare early versus later interventions (Brummel 2014; Chiang 2006; Denehy 2013; ISRCTN20436833; Moss 2016; Nava 1998; NCT01058421; Porta 2005).

Awaiting classification

We identified four studies that are awaiting classification (Dong 2014; Files 2013; Malicdem 2010; Susa 2004). The reasons we placed these studies in this category varied. The contact author in one study declined to clarify methods and eligibility criteria as they expected to publish their results (Files 2013), and we have not received a response to our correspondence regarding eligibility criteria or timing of intervention from authors in the remaining three studies (Dong 2014; Malicdem 2010; Susa 2004). See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for further information.

Ongoing studies

We identified three ongoing studies in trial registries (NCT01927510; NCT01960868; RBR‐6sz5dj). One study has been completed but not yet published (NCT01927510), and we were unable to identify publications for the remaining two studies (NCT01960868; RBR‐6sz5dj). In addition, study authors did not respond to our correspondence regarding the status of their trials. See Characteristics of ongoing studies for further information.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 1 for 'Risk of bias summary' and Figure 2 for 'Risk of bias' graph for the studies included in this review.

Allocation

All four studies demonstrated adequate random sequence generation and allocation concealment except Morris 2016, which was unclear for allocation concealment, and therefore we considered them at low risk of selection bias.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel

Although (Kayambu 2015), stated that they blinded participants, we considered all studies to be at high risk of performance bias as these interventions could not have been blinded for either participants or trial personnel in the ICU.

Blinding of outcome assessment

Two studies (Morris 2016; Patman 2001), demonstrated a high risk of detection bias for all outcomes except mortality; both reported that the outcome assessor was aware of group allocation. Kayambu 2015 and Schweickert 2009 blinded outcome assessors; therefore we considered these studies to be at low risk of detection bias. As the event of mortality would have been evaluated by personnel outside all of the studies, we considered them all to be at low risk of detection bias for this outcome.

Incomplete outcome data

Three studies demonstrated a high risk of attrition bias for all outcomes except mortality (Kayambu 2015; Morris 2016; Patman 2001). These studies reported results only for participants who completed the study, rather than for all randomized participants. Morris 2016 achieved outcome measurement in approximately 67% of those randomized. In addition, we noted a high dropout rate for the intervention group in the study conducted by Kayambu 2015. Only one study demonstrated a low risk of attrition bias (Schweickert 2009), as study authors presented outcome data for all outcomes including mortality for all enrolled participants.

Selective reporting

We considered all included studies to have a low risk of bias for selective reporting.

Kayambu 2015 and Morris 2016 reported all outcomes specified in the protocols for their study, and the remaining two studies reported all outcomes specified in the methods section of the text (Patman 2001; Schweickert 2009).

Other potential sources of bias

Two studies demonstrated an unclear risk of bias associated with the reporting of standard care as the control condition was not well described (Kayambu 2015; Schweickert 2009). These studies compared the intervention with standard care and the components of care delivered to the control group was not discussed in Schweickert 2009. Therefore we feel that elements of the intervention may have been delivered to the control groups. Although Kayambu 2015 described the components of the intervention delivered to standard care, the frequency and duration of the exercise strategy were not well explained and the dosage and intensity were not reported.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

1. Physical function and performance (the ability to perform everyday activities such as basic ADLs, and physical performance tasks)

Three studies, involving a total of 454 participants, reported aspects of physical functional status (Kayambu 2015; Morris 2016; Schweickert 2009).

Kayambu 2015, reported results for 42 of 50 (84%) of the participants for the acute care index of function (ACIF) and the physical function ICU test (PFIT) at discharge from ICU, and there was no clear difference between groups. However the evidence is of low quality, due to high risk of performance and attrition biases and imprecision (one small study); ACIF: (61.1 versus 55, MD 6.10, 95% CI ‐11.85 to 24.05; P = 0.45), and PFIT (5.6 versus 5.4, MD 0.20, 95% CI ‐0.98 to 1.38; P = 0.61).

Morris 2016 reported SPPB score as a measure of physical performance, with a mean score of 1.6 in the intervention group and 1.9 in the control group (MD ‐0.3, 95% CI ‐1.1 to 0.5; P = 0.46) at ICU discharge, and a MD of 0 (95% CI ‐1.0 to 0.9) at hospital discharge.

The study by Schweickert 2009, reported a number of outcomes associated with functional status for all of the 104 participants in this study. More of those in the intervention group returned to independent functional status at hospital discharge (59% versus 35%, RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.11 to 2.64; P = 0.01). Participants in the intervention group achieved a greater number of independently performed ADL on discharge from the ICU (median of 3 versus 0; P = 0.15) and hospital (median of 6 versus 4; P = 0.06), but these results were not statistically significantly different. There was no clear difference between the intervention and control groups for the Barthel Index score at hospital discharge (median score of 75 versus 55; P = 0.05). Schweickert 2009, reported other outcomes related to physical performance, with results favouring the intervention group for time from intubation to out of bed (median of 1.7 versus 6.6 days), standing (median of 3.2 versus 6 days), marching in place (median of 3.3 versus 6.2 days), transferring to a chair (median of 3.1 versus 6.2 days) and walking (median of 3.8 versus 7.3 days). Results for each of these outcomes were clinical important in size. Study authors also reported a difference favouring the intervention group for the greatest walking distance at hospital discharge (median of 33.4 versus 0 metres; P = 0.004).

Study samples were generally small, there was no blinding of participants or personnel, there was heterogeneity in the interventions and the outcomes used to measure their effect and inadequate descriptions of the interventions delivered as standard care for this outcome. Therefore we downgraded evidence to low. See Table 4 for further information about physical function and performance outcomes.

3. Functional status measures.

| Outcome measure | Intervention group | Control group | Effect size (95% CI) where possible | P value | Reference of studies |

| Return to independent functional status at hospital discharge ‐ n (%) in each group | 29/49 (59%) | 19/55 (35%) | RR 1.71 (1.11 to 2.64) | 0.01 | Schweickert 2009 |

| Independent ADL total at ICU discharge ‐ median (IQR) | 3 (0‐5) | 0 (0‐5) | 0.15 | Schweickert 2009 | |

| Independent ADL total at hospital discharge ‐ median (IQR) | 6 (0‐6) | 4 (0‐6) | 0.06 | Schweickert 2009 | |

| Acute Care Index of Function (ACIF) at ICU discharge ‐ mean (SD) | 61.1 (33.1) | 55 (24.4) | MD 6.10 (‐11.85 to 24.05) | 0.45 | Kayambu 2015 |

| Physical Function ICU Test (PFIT) at ICU discharge ‐ mean (SD) | 5.6 (2.1) | 5.4 (1.7) | MD 0.20 (‐0.98 to 1.38) | 0.61 | Kayambu 2015 |

| Short Physical Performance Battery at ICU discharge ‐ mean (SD) | 1.6 (3.1) | 1.9 (2.8) | MD ‐0.3 (‐1.1 to 0.5) | 0.46 | Morris 2016 |

| Time from intubation to out of bed (days) ‐ median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.1 to 3.0) |

6.6 (4.2‐8.3) |

< 0.0001 | Schweickert 2009 | |

| Time from intubation to standing (days) ‐ median (IQR) | 3.2 (1.5 to 5.6) |

6.0 (4.5‐8.9) |

< 0.0001 | Schweickert 2009 | |

| Time from intubation to marching in place (days) ‐ median (IQR) | 3.3 (1.6 to 5.8) |

6.2 (4.6‐9.6) |

< 0.0001 | Schweickert 2009 | |

| Time from intubation to transferring to a chair (days) ‐ median (IQR) | 3.1 1.8 to 4.5) |

6.2 (4.5‐8.4) |

< 0.0001 | Schweickert 2009 | |

| Time from intubation to walking (days) ‐ median (IQR) | 3.8 (1.9 to 5.8) |

7.3 (4.9‐9.6) |

< 0.0001 | Schweickert 2009 | |

| Barthel Index score at hospital discharge (score 0‐100) ‐ median (IQR) | 75 (7.5 to 95) | 55 (0‐85) | 0.05 | Schweickert 2009 | |

| Greatest walking distance (metres) at hospital discharge ‐ median (IQR) (metres) | 33.4 (0 to 91.4) | 0 (0‐30.4) | 0.004 | Schweickert 2009 |

ADL: activities of daily living; CI: confidence interval; ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range; MD: mean difference; n: number; RR: risk ratio; SD: standard deviation

2. Adverse events (falls, accidental dislodgement of attachments, haemodynamic instability, oxygen desaturation or any other adverse events stated by trial authors)

All studies reported adverse events for a total of 690 participants and the incidence was low.

Kayambu 2015, reported that no adverse events occurred during exercise sessions.

Morris 2016, reported no adverse events specific to physical therapy (e.g. endotracheal removal, vascular access device removal, fall, cardiac arrest). There were four events in the intervention group and three in the control group considered severe, and one life‐threatening event in the intervention group. All were deemed unrelated to physical therapy. There was also an episode of asymptomatic bradycardia lasting less than one minute, with the participant completing the exercise session afterwards.

Schweickert 2009, reported the following serious adverse events for the intervention group: accidental dislodgement of the radial arterial catheter in one of 49 (2%) participants, and one of 49 (2%) participants experienced oxygen desaturation less than 80%. This study also reported cessation of therapy due to patient instability in 19 of 498 (4%) of the intervention sessions.

Patman 2001, reported 10 serious adverse events in that five of 101 (5%) participants in the intervention group compared to five of 109 (4.6%) participants in the control group met the criteria for postoperative pulmonary complications, however these were deemed unrelated to intervention.

As there was no blinding of participants and personnel, and heterogeneity in the interventions, small numbers of participants and inadequate descriptions of the interventions delivered as standard care, there was low‐quality evidence for this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

1a Length of stay (ICU)

All studies involving a total of 690 participants reported length of stay in the ICU.

Schweickert 2009 (104 participants), reported that those in the intervention group stayed a shorter time in the ICU (median of 5.9 versus 7.9 days; P = 0.08). Morris 2016, reported similar times in ICU for the two groups (7.5 versus 8.0, median difference 0, 95% CI ‐2.5 to 2.0; P = 0.68). In contrast, two studies involving a total of 260 participants reported that those in the intervention group stayed longer in the ICU: Patman 2001; (42.7 versus 36.7 days, MD 6, 95% CI ‐3.58 to 15.58; P = 0.56), and Kayambu 2015; (median of 12 versus 8.5 days; P = 0.43).

As there was no blinding of participants and personnel, heterogeneity in the interventions, small numbers of participants and inadequate descriptions of the interventions delivered as standard care, there was low‐quality evidence for this outcome.

1b Length of stay (hospital)

All four included studies reported length of stay in the hospital. Participants in the intervention group spent less time in hospital in two studies involving a total of 260 participants but the evidence was of low quality so we cannot be sure of this result: Patman 2001 (9.2 versus 9.6 days, MD ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐1.97 to 1.17; P = 0.25) and Kayambu 2015 (median of 41 versus 45 days; P = 0.80). Morris 2016 found that both groups spent similar time in hospital (10.0 days, median difference 0, 95% CI ‐1.5 to 3.0; P = 0.41. Schweickert 2009 reported on 104 participants and found no clear difference between groups (median of 13.5 versus 12.9 days; P = 0.93).

As there was no blinding of participants and personnel, heterogeneity in the interventions and the outcomes used to measure their effect, small numbers of participants and inadequate descriptions of the interventions delivered as standard care, there was low‐quality evidence for this outcome.

See Table 5 for further information for length of stay in the ICU and hospital.

4. Length of stay (ICU and hospital).

| Outcome measure | Intervention group | Control group | Mean difference (95% CI) where possible | P value | Reference of studies |

| Mean (SD) LOS (h) in ICU ‐ mean (SD) | 42.7 (42.4) | 36.7 (26.8) | 6.00 (‐3.58 to 15.58) | 0.56 | Patman 2001 |

| Median (IQR) LOS (days) in ICU ‐ median (IQR) | 12.0 (4‐45) | 8.5 (3‐36) | 0.43 | Kayambu 2015 | |

| 7.5 (4‐14) | 8.0 (4‐13) | 0.68 | Morris 2016 | ||

| 5.9 (4.5‐13.2) | 7.9 (6.1‐12.9) | 0.08 | Schweickert 2009 | ||

| Mean (SD) LOS (days) in hospital ‐ mean (SD) | 9.2 (4.5) | 9.6 (6.7) | ‐0.40 (‐1.97 to 1.17) | 0.25 | Patman 2001 |

| Median (IQR) LOS (days)in hospital ‐ median (IQR) | 41 (9‐158) | 45 (14‐308) | 0.80 | Kayambu 2015 | |

| 10.0 (6‐17) | 10.0 (7‐16) | 0.41 | Morris 2016 | ||

| 13.5 (8.0‐23.1) | 12.9 (8.9‐19.8) | 0.93 | Schweickert 2009 |

CI: confidence interval; ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range; LOS: length of stay; SD: standard deviation

2. Muscle strength (Medical Research Council (MRC) score, cross‐sectional diameter)

Two studies involving a total of 146 participants used the MRC sum score to measure muscle strength (Kayambu 2015; Schweickert 2009). Kayambu 2015 reported results for 42 of 50 (84%) participants and found that those in the intervention group attained slightly higher MRC scores at ICU discharge (51.9 versus 47.3, MD 4.60, 95% CI ‐3.11 to 12.31; P = 0.24) but with a confidence interval that suggests the effect could favour either intervention or control. The study by Schweickert 2009 involved 104 participants and the intervention group scored higher in this outcome (median of 52 versus 48; P = 0.38) but not statistically significantly so. Two studies involving 404 participants measured hand grip strength using dynamometry (Morris 2016; Schweickert 2009). There were no clear differences between groups for this outcome. Schweickert 2009 reported that the percentage of participants who had ICU‐acquired paresis at hospital discharge was lower in the intervention group but we cannot be sure of this effect, due to small numbers of participants; (15/49 (31%) versus 27/55 (49%), RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.03; P = 0.09).

As there was no blinding of participants and personnel, heterogeneity in the interventions and the outcomes used to measure their effect, small numbers of participants and inadequate descriptions of the interventions delivered as standard care, there was low‐quality evidence for this outcome.

See Table 6 for further information on muscle strength.

5. Muscle strength.

| Intervention group | Control group | Effect size (95% CI) where possible | P value | Reference of studies | |

| Muscle strength (MRC score, 0‐60) at ICU discharge ‐ mean (SD) | 51.9 (10.5) | 47.3 (13.6) | MD 4.60 (‐3.11 to 12.31) | 0.24 | Kayambu 2015 |

| Hand‐grip strength (kg) at ICU discharge ‐ mean (SD) | 20.0 | 20.9 | MD ‐0.8 (‐4.0 to 2.3) | 0.60 | Morris 2016 |

| Muscle strength (MRC score, 0‐60) at hospital discharge ‐ median (IQR) | 52 (25‐58) | 48 (0‐58) | 0.38 | Schweickert 2009 | |

| Hand‐grip strength (kg) at hospital discharge ‐ median (IQR) | 39 (10‐58) | 35 (0‐57) | 0.67 | Schweickert 2009 | |

| Hand‐grip strength (kg) at hospital discharge ‐ mean (SD) | 22.6 (10.4) | 24.3 (16.3) | MD ‐1.7 (‐4.6 to 1.2) | 0.25 | Morris 2016 |

| ICU‐acquired paresis at hospital discharge ‐ n (%) | 15/49 (31%) | 27/55 (49%) | RR 0.62 (0.38 to 1.03) | 0.09 | Schweickert 2009 |

CI: confidence interval; ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range; MD: mean difference; MRC: medical research council; SD: standard deviation

3. Health‐related quality of life or well‐being (e.g. MOS 36‐item Short‐Form Health Survey (SF‐36) questionnaire)

Two studies involving 350 participants reported this outcome. Kayambu 2015 reported results for eight subsets of the SF‐36 questionnaire at six months post‐hospital discharge for 30 of 50 (60%) participants. Participants in the intervention group achieved clinically meaningfully higher scores in physical function; (81.8 versus 60, MD 21.8, 95% CI 0.81 to 42.79; P = 0.04); and role physical; (61.4 versus 17.1, MD 44.3, 95% CI 14.79 to 73.81; P = 0.005). There were no important between‐group differences for the remaining six domains of the SF‐36 in this study. Morris 2016 reported results for the physical function summary score and the mental health summary score of the SF‐36 at hospital discharge and at follow‐up visits. There were no clinically meaningful differences between groups at any time point except at six months, where the intervention group had significantly higher scores. However, no mention was made of adjusting for repeated testing on this measure. The MD in physical function score at six months was 12.2 units, a clinically important difference.

As there was no blinding of participants and personnel, heterogeneity in the interventions small numbers of participants and inadequate descriptions of the interventions delivered as standard care, there was low‐quality evidence for this outcome.

See Table 7 for further information for health‐related quality of life outcomes at 6 months.

6. Health‐related quality of life.

| Outcome measure at 6 months' follow‐up | Mean (SD) of intervention group | Mean (SD) of control group | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | Reference of studies |

| SF‐36 physical function | 81.8 (22.2) | 60.0 (29.4) | 21.8 (0.81 to 42.79) | 0.04 | Kayambu 2015 |

| 55.9 (27.3) | 43.6 (27.7) | 12.2 (3.9 to 20.7) | 0.001 | Morris 2016 | |

| SF‐36 role physical | 61.4 (43.8) | 17.1 (34.4) | 44.3 (14.79 to 73.81) | 0.005 | Kayambu 2015 |

| SF‐36 bodily pain | 70.9 (20.7) | 64.7 (22.5) | 6.20 (‐10.78 to 23.18) | 0.46 | Kayambu 2015 |

| SF‐36 general health | 50.5 (11.9) | 41.8 (11.3) | 8.70 (‐0.24 to 17.64) | 0.06 | Kayambu 2015 |

| SF‐36 vitality | 45.9 (12.0) | 39.2 (7.7) | 6.70 (‐0.22 to 13.62) | 0.07 | Kayambu 2015 |

| SF‐36 social functioning | 71.6 (37.1) | 73.7 (37.2) | ‐2.10 (‐30.94 to 26.74) | 0.88 | Kayambu 2015 |

| SF‐36 role emotional | 63.6 (40.7) | 33.3 (45.8) | 30.30 (‐3.88 to 64.48) | 0.08 | Kayambu 2015 |

| SF‐36 mental health | 38.6 (11.5) | 37.3 (7.4) | 1.30 (‐5.75 to 8.35) | 0.71 | Kayambu 2015 |

| 48.8 | 46.4 | 2.4 (‐1.2 to 6.0) | 0.19 | Morris 2016 |

CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation; SF‐36: Short Form 36

4. Delirium

Two studies involving 404 participants (Morris 2016; Schweickert 2009), reported this outcome in the ICU, and one study reported this outcome for the entire hospital stay (Schweickert 2009). Schweickert 2009 found that those in the intervention group spent a lower number of days with delirium while in ICU; (median of 2 versus 4 days; P = 0.03) and in hospital; (median of 2 versus 4 days; P = 0.02). However, Morris 2016 found no difference between groups (median of 0 versus 0 days; P = 0.71).

As there was no blinding of participants and personnel, heterogeneity in the interventions, small numbers of participants and inadequate descriptions of the interventions delivered as standard care, there was low‐quality evidence for this outcome.

See Table 8 for further information about delirium.

7. Delirium.

| Intervention group | Control group | P value | Reference of studies | |

| ICU (days) with delirium ‐ median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0‐6.0) | 4.0 (2.0‐7.0) | 0.03 | Schweickert 2009 |

| 0 (0 ‐12.5) | 0 (0‐9.1) | 0.71 | Morris 2016 | |

| Hospital (days) with delirium ‐ median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0‐6.0) | 4.0 (2.0‐8.0) | 0.02 | Schweickert 2009 |

ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range

5. Death from any cause

Two studies involving a total of 260 participants measured the percentage of participants who died in the ICU, but the numbers were too small to be confident in this result (Kayambu 2015 3/26 (12%) versus 1/24 (4%), RR 2.77, 95% CI 0.31 to 24.85; P = 0.36, and Patman 2001 (0/101 (0%) versus 3/109 (2.8%), RR 0.16, 95% CI 0.008 to 3.03; P = 0.22). One study involving a total of 104 participants measured mortality while participants were in the hospital (Schweickert 2009). There was no clear difference between groups, but again the numbers are too small to be confident of this result (9/49 (18%) versus 14/55 (25%), RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.52; P = 0.53). One study involving 50 participants measured 90‐day mortality (Kayambu 2015), and reported that the percentage of those in the intervention group who died within 90 days of admission to this study was 8/26 (31%) versus 2/24 (8%) in the control group (RR 3.69, 95% CI 0.87 to 15.69; P = 0.08). Morris 2016 reported only on the proportion alive and hospital‐readmission‐free at six months (48.7% versus 44.7%, RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.39; P = 0.69). As there was heterogeneity in the interventions, small numbers of participants and inadequate descriptions of the interventions delivered as standard care, there was low‐quality evidence for this outcome.

See Table 3 for further information about this outcome.

6. Hospital costs

No studies measured this outcome.

7. Other outcomes not pre‐specified in this review ‐ Duration of intubation/mechanical ventilation

Three studies, including a total of 390 participants, reported duration of mechanical ventilation. Schweickert 2009 found that those in the intervention group spent less time on mechanical ventilation and this difference was of clinically important size (median of 3.4 versus 6.1 days; P = 0.02). Two studies reported that those in the intervention group spent a longer time intubated but there were no clear differences between groups (Kayambu 2015; Patman 2001). Patman 2001 reported results for 210 of 236 (89%) participants; (13 versus 12.7 hours, MD 0.20, 95% CI ‐1.1 to 1.65; P = 0.85) and Kayambu 2015 on 50 participants; (median of 8 versus 7 days; P = 0.22).

As there was no blinding of participants and personnel, heterogeneity in the interventions, small numbers of participants and inadequate descriptions of the interventions delivered as standard care, there was low‐quality evidence for this outcome.

See Table 9 for further information about this outcome.

8. Other outcomes not specified in this review.

| Intervention group | Control group | Mean difference (95% CI) where possible | P value | Reference of studies | |

| Duration (h) of mechanical ventilation ‐ mean (SD) | 13 (4.8) | 12.7 (4.7) | 0.20 (‐1.1 to 1.65) | 0.85 | Patman 2001 |

| Duration (days) of mechanical ventilation ‐ median (IQR) | 8.0 (4‐64) | 7.0 (2‐30) | 0.22 | Kayambu 2015 | |

| 3.4 (2.3‐7.3) | 6.1 (4.0‐9.6) | 0.02 | Schweickert 2009 |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval. IQR: interquartile range. SD: standard deviation.

As this outcome was not listed in the protocol for this review (Doiron 2013), we have indicated this change in the section Differences between protocol and review.

Discussion