Abstract

PURPOSE:

IBM Watson for Oncology trained by Memorial Sloan Kettering (WFO) is a clinical decision support tool designed to assist physicians in choosing therapies for patients with cancer. Although substantial technical and clinical expertise has guided the development of WFO, patients’ perspectives of this technology have not been examined. To facilitate the optimal delivery and implementation of this tool, we solicited patients’ perceptions and preferences about WFO.

METHODS:

We conducted nine focus groups with 46 patients with breast, lung, or colorectal cancer with various treatment experiences: neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy, chemotherapy for metastatic disease, or systemic therapy through a clinical trial. In-depth qualitative and quantitative data were collected and analyzed to describe patients’ attitudes and perspectives concerning WFO and how it may be used in clinical care.

RESULTS:

Analysis of the qualitative data identified three main themes: patient acceptance of WFO, physician competence and the physician-patient relationship, and practical and logistic aspects of WFO. Overall, participant feedback suggested high levels of patient interest, perceived value, and acceptance of WFO, as long as it was used as a supplementary tool to inform their physicians’ decision making. Participants also described important concerns, including the need for strict processes to guarantee the integrity and completeness of the data presented and the possibility of physician overreliance on WFO.

CONCLUSION:

Participants generally reacted favorably to the prospect of WFO being integrated into the cancer treatment decision-making process, but with caveats regarding the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the data powering the system and the potential for giving WFO excessive emphasis in the decision-making process. Addressing patients’ perspectives will be critical to ensuring the smooth integration of WFO into cancer care.

INTRODUCTION

IBM Watson for Oncology trained by Memorial Sloan Kettering (WFO; MSK) is a clinical decision support tool developed in collaboration between IBM and MSK to harness the power of cognitive technology to provide clinicians with informed treatment recommendations for patients with cancer.1 WFO has been trained by MSK clinicians, using their experience delivering evidence-based cancer care, to determine patient factors relevant for decision making and generate personalized treatment recommendations. The goal for WFO is to help physicians decide upon the best ways to treat each patient.

Clinical decision support tools such as WFO hold promise for improving the value of cancer care delivery. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has recognized the important role decision support tools can play in establishing a value-driven health care environment. For example, ASCO has incorporated oncology clinical pathways (OCPs), therapeutic decision support tools developed by both payers and providers with the goal of delivering the right treatment to the right patient at the right time, as a key feature in its Patient-Centered Oncology Payment Program.2 Multiple studies have demonstrated that the use of OCP decision support improves value by lowering costs while maintaining or improving outcomes.3-5

Although substantial technical and clinical expertise guided the development of WFO, patients’ perspectives of this technology have not been examined. Patients are important stakeholders because their clinical encounters and treatment may be influenced by WFO. Patients’ values, preferences, and expressed needs are critical components of patient centeredness, a fundamental characteristic of quality health care.6,7 Furthermore, past research suggests that patients can have serious concerns about clinical decision support tools. People view physicians who use a decision support tool as having less diagnostic ability than physicians who do not8,9 and have particularly unfavorable impressions of physicians who rely exclusively on such tools.10 Some evidence also suggests that patients believe these tools interfere with patient-physician communication.11 However, when a physician’s decision leads to a negative outcome, people may view a physician who used a decision support tool as less negligent than one who did not.12 In addition, many patients react favorably toward the use of computerized clinical decision support tools in their care, perceiving that such tools provide physicians with valuable information.13,14

Clarifying and addressing patients’ perspectives about WFO are critical for the optimal delivery and implementation of this technology. Patients’ responses to WFO will directly affect the extent to which it is successfully integrated into routine cancer care. Patients’ dissatisfaction or discomfort with WFO could hinder its adoption by physicians; physicians may be less willing to use a decision support tool when they believe that it will harm the physician-patient relationship.15 Therefore, our objective was to assess the attitudes and perspectives of patients with cancer concerning WFO and how it may be used in clinical care. We focused on the use of WFO to make chemotherapy recommendations, the most advanced component of WFO at the time the study began and a clinical situation commonly encountered by patients with cancer.16

METHODS

Guidelines from a qualitative research tradition informed the study sampling plan and size.17-19 Our approach used focus groups, rather than individual interviews, because the former are better suited to understanding levels of agreement and disagreement in patient perspectives on WFO.20 Focus groups were stratified on the basis of diagnosis (breast, lung, or colorectal cancer) and treatment setting (neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage disease, chemotherapy for metastatic disease, or systemic therapy [chemotherapy or immunotherapy after prior chemotherapy] administered in a clinical trial for disease at any stage); thus, participants were recruited to participate in one of nine separate focus groups conducted between May 2016 and August 2017 (Table 1). Eligible patients were age ≥ 18 years, were fluent in English, had been diagnosed with one of the target cancers, and had started chemotherapy at MSK within 8 months (neoadjuvant/adjuvant and metastatic focus groups) or 1 year (clinical trial focus groups) of study enrollment. The MSK Institutional Review Board approved this study.

TABLE 1.

Participant Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (N = 46)

Eligible patients were sent an introductory letter and telephoned by research staff; interested participants provided informed consent. Participants chose to attend a focus group either in person or virtually through a videoconference call. During the focus group, participants viewed a brief narrated slideshow developed by the research team, which featured diverse actors depicting patients and physicians involved in a treatment decision-making process with WFO. The slideshow described the functionality of WFO, how information is curated for WFO, and the WFO interface. After the slideshow, participants completed a questionnaire with 14 items assessing their initial impressions of WFO and one item (the Decision Control Preferences Scale21) assessing their preferences for decisional control when making treatment decisions with physicians. This questionnaire was administered immediately after the slideshow to ensure that participants’ responses were not influenced by discussion with other study participants. Then, a trained qualitative methods specialist used a focus group guide (open-ended questions and prompts developed by the research team and informed by past studies on patient acceptability of clinical decision support tools) to moderate a semistructured discussion with participants about the acceptability of WFO, perceived competence of physicians who would use WFO, how WFO might affect the physician-patient relationship, preferences for use of WFO in clinical consultations, and patient values relevant to treatment decisions. After the discussion, participants completed a brief questionnaire assessing demographic characteristics and health literacy (measured with the Single Item Literacy Screener22 rated on a 1 to 5 scale; scores > 2 indicate limited literacy). Focus groups lasted 60 to 90 minutes. Participants received $25 for their contribution.

A member of the research team took notes during each focus group, and all groups were audio recorded and transcribed. Participants’ narrative comments were reviewed using deductive thematic text analysis.23-28 At least four team members initially read each transcript, highlighting important content and recording reflections on the transcript via margin coding,29 before completing a written analysis template with supporting participant quotations. Although the analysis template was structured around the primary topics addressed in the focus group guide, team members inductively identified novel subthemes on the basis of the narrative content. The team met to generate collective findings for each transcript by consensus and met again to identify higher-order descriptive and interpretive thematic similarities and differences among the nine focus groups according to treatment setting (no differences were observed on the basis of diagnosis). Descriptive statistics were computed to summarize questionnaire data.

RESULTS

Forty-six individuals participated in the focus groups (Table 1). Most participants were female (63%), were white (59%), had a college degree (70%), and had a household income > $100,000 (61%).

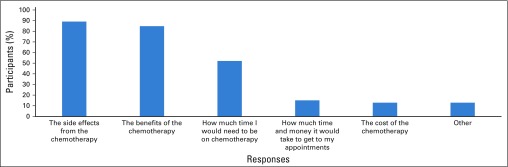

Analysis of the qualitative data identified three main themes: patient acceptance of WFO, physician competence and the physician-patient relationship, and practical and logistic aspects of WFO. These main themes and relevant subthemes are described here and indicated by italicized text; illustrative participant quotations are listed in Table 2. Quantitative data from the questionnaire administered immediately after the slideshow reflecting the main themes appear in Figure 1 and Appendix Fig A1 (online only).

TABLE 2.

Patient Perspectives About WFO and Illustrative Participant Quotes

Fig 1.

Participant responses to the study questionnaire regarding perceptions of a physician who used IBM Watson for Oncology trained by Memorial Sloan Kettering (WFO). Participants responded to each item after being instructed to “Imagine a doctor used IBM Watson for Oncology to decide which chemotherapy to use to treat your cancer.” The first two items reflect the main theme of patient acceptance of WFO. All remaining items reflect the main theme of physician competence and the physician-patient relationship.

Patient Acceptance of WFO

With the questionnaire, participants were asked to imagine that a “doctor used WFO to decide which chemotherapy to use” to treat their cancer. Participants’ responses suggested some ambivalence about the acceptability of this practice (Fig 1). Although a majority (63%) agreed that WFO would help their physician identify the best chemotherapy, many (35%) were unsure. Similarly, most participants (63%) agreed that they would be glad that their physician had used WFO, but others (35%) were not sure that they would be glad.

Qualitative data derived from the discussions clarified these beliefs. A prominent subtheme expressed in all focus groups was that if WFO were used appropriately, it would be seen as a valuable tool. Appropriate use would entail having WFO serve as simply another resource for their physician; in this way, participants described WFO as a potentially invaluable resource that oncologists could integrate with their traditional resources (eg, colleagues, scientific journals) to choose the most effective chemotherapy options for their patients. Participants described the ability of WFO to provide oncologists with access to a wealth of medical knowledge and cutting-edge research as an important advantage. As long as oncologists used WFO as “a tool, not a crutch,” participants believed it would be an acceptable resource. A perspective uniquely described by some of the metastatic groups was an expectation that WFO would help patients gain faster access to more precise and effective treatments, thereby improving their care and outcomes.

While acknowledging that WFO could be a helpful tool, all groups raised concerns. Most concerns stemmed from the prospect of physician overreliance on WFO. Participants worried that oncologists would take the advice of WFO over their own expertise or clinical judgment, which would be unacceptable because they want their oncologists to ultimately decide upon the best treatment. Nearly every group also described concerns about the quality of data being curated for and entered into WFO. Specifically, participants wanted to know more about the source of information for WFO: who is entering data, whether potential exists for human error in data entry, whether information is from MSK only or other medical centers, and whether WFO is updated in real time. If the data were of poor quality, this would undermine acceptance of WFO.

For some of the clinical trial focus groups, acceptance of WFO would be influenced by their concerns about transparency. These participants wanted their oncologists to be transparent about their use of WFO in the clinical setting, including whether there was a financial cost for using WFO, whether oncologists were required to use WFO, and whether they could opt out of using it. Several additional important concerns were raised infrequently. A few participants expressed concern about unacceptable uses of patient data, questioning the privacy of information in WFO and the prospect of insurance companies using WFO to limit physicians’ ability to make autonomous decisions regarding the best care for a patient. Others were concerned that WFO could be used as a scapegoat if a treatment did not go as planned or if a patient experienced a poor outcome. Although this perspective was not described by many, it was a genuine concern for a small number of participants.

Physician Competence and the Physician-Patient Relationship

Questionnaire responses indicated generally positive perceptions of a physician who used WFO (Fig 1). A majority agreed that they would believe the physician was being careful (82%), trust the physician’s decision (78%), believe he or she was a good physician (73%), and believe he or she was an expert (65%). Few participants endorsed statements indicating the belief that a physician who used WFO did not know as much about cancer as he or she should or did not care about them, and few would have doubts about a physician in this scenario (≤ 20% agreed). Finally, when asked to rate such a physician’s knowledge and experience with their illness, 38% rated the physician as excellent, 13% as very good, 31% as good, 16% as fair, and 2% as poor.

Throughout the discussions, participants conveyed a perception of and a desire to see physicians as the main driver of personalized cancer care. Participants stated that their physicians bring an important human element to care, including the ability to truly know the patient, empathize, and visually evaluate the patient’s health. This allows for a personalization of care that participants believed a computerized tool like WFO could not replicate.

Across groups, participants explained that WFO would have little to no influence on their perceptions of a physician’s competence, provided that the physician remained the primary or final decision maker and continued to be guided by his or her experience and expertise. Furthermore, some would perceive their physicians as more capable if they used WFO because it would mean they were using the most current technology, and a few metastatic groups believed a physician using WFO would seem technologically savvy. Nonetheless, participants frequently described how overreliance on WFO would negatively influence perceptions of a physician’s competence. Overreliance on WFO could, in participants’ minds, lead to laziness on the part of physicians. Participants identified overreliance as a particular risk for young physicians, given their lack of clinical experience. Participants’ comments across groups suggested that their trust strongly influenced their confidence in how physicians would use WFO. For example, some explained that they had great trust in their oncologist and in the reputation of MSK, and therefore, appropriate use of WFO would not be reflective of competence. Participants noted that they may have different concerns about the competence of a physician using WFO in another context (eg, greater concern because the physician may lack expertise to evaluate WFO recommendations or less concern because WFO would supplement a physician’s limited knowledge or experience).

Participants across groups described how WFO may enhance the patient-physician relationship through improved communication. Participants expected that their oncologist would use WFO to openly discuss the treatment decision-making process. Although many participants reported that they did not currently understand the process their oncologists went through to choose a chemotherapy, they deeply valued the idea of shared decision making or gaining clarity about the rationale for their oncologist’s recommendations and believed WFO could facilitate such interactions. Conversely, some neoadjuvant/adjuvant groups expressed concerns about WFO interfering with communication, making care more automated and less interactive, thereby interfering with collaboration between the patient and physician.

Practical and Logistic Aspects of WFO

Questionnaire data indicated factors that participants wanted WFO to consider when making treatment recommendations (Appendix Fig A1). Discussions confirmed that participants wanted WFO to consider multiple factors for its recommendations, including medical (eg, age, race, past treatment responses, and side effects) and behavioral information (eg, exercise, smoking, environmental exposures, and use of alternative medicines). Participants expressed the general belief that the more information WFO had about them, the more accurate its treatment recommendations would be. Participants also expected that WFO would be kept up to date with a patient’s information as it changed across the treatment trajectory to ensure the best recommendations. Some noted that such real-time data collection may allow WFO to collate information, such as data about patient side effects, thereby providing novel scientific knowledge.

Across groups, participants generally agreed that treatment cost should not determine WFO recommendations. Many acknowledged cost as a complex issue and were uncomfortable discussing the possibility of WFO considering patients’ financial limitations when making recommendations. Participants also expressed a strong preference for WFO to provide information about treatment side effects. Specifically, participants wanted to be informed about potential side effects rather than have WFO include this factor in its treatment algorithm. Many noted that side effect information would not likely change their treatment choices but may allow them to prepare for future experiences.

Regarding use of WFO in the clinical setting, participants generally expressed a preference for physicians to use WFO before the consultation and then review their decision-making process. Participants felt that by using WFO before the consultation, a physician would be better prepared for the visit (ie, “doing their homework”) and could then use WFO to discuss the treatment decision and gather additional information from the patient to potentially inform or revise the recommendation. Across groups, participants expressed broad interest in a printout of WFO treatment recommendations. Common suggestions for information to include within this printout were treatment options including clinical trials, expected benefits and side effects of treatment options, and rationales for the recommendations. Access to this information (as a hard copy or through a patient portal) would help participants feel part of a shared decision-making process. This information would be used for personal research, future reference, and sharing with family, other patients with cancer, and other physicians when seeking a second opinion.

DISCUSSION

We examined patient perspectives about WFO, a decision support tool to provide physicians with personalized cancer treatment recommendations. Patient perspectives are critical to the development of WFO, any educational materials it generates, and its integration into clinic workflow. High patient acceptance of WFO will also contribute to its uptake by physicians. Importantly, in this study, we observed high levels of patient interest, perceived value, and acceptance of WFO, although with caveats that will be critical to address as WFO expands in its scope and dissemination.

Participants expressed broad agreement that WFO could help identify treatment options and outcomes and foster trust in their physician if he or she used WFO in conjunction with other information sources. Participants also agreed that use of WFO could enhance the relationship with their physician, because it would integrate all their important medical information and ideally prompt their physician to be more transparent about the treatment decision-making process. However, expectations regarding the specific role of WFO in decision making varied; some believed that the decision should ultimately be driven by the physician, with WFO as a resource, and others believed that WFO should be used to help the physician convey multiple plausible options to the patient, with the decisional choice ultimately shared between patient and physician or even by the patient alone. It will be important to explore patient perceptions and expectations when WFO is implemented in routine practice, because they could influence the treatment decision-making process in variable and unanticipated ways.

Despite most participants’ optimistic views of WFO, valuable caveats and concerns were raised across all focus groups. Importantly, participants raised the concern that physicians could become overly dependent on WFO. Indeed, the potential harms of overreliance on computers, including concerns regarding data quality and maintenance, privacy, and loss of the human touch in cancer care that physicians uniquely provide by their support and personalization of treatment over time, were emphasized. Apprehension about technology encroaching upon medical encounters is topical,30 and such concerns may be amplified and informed by the current environment, with mainstream media frequently reporting on potential harms and limitations of artificial intelligence, as well as widespread electronic breaches of consumer privacy.31,32 Many of these concerns have also been raised with OCPs, including data quality and maintenance, loss of physician autonomy, and erosion of the physician-patient relationship.33,34 ASCO has addressed these concerns by developing criteria for high-quality OCPs centered on development, implementation and use, and analytics and has evaluated vendors against those criteria.35 Although there are differences between WFO and OCPs, both are used at the point of care to provide patients with optimal treatment. Therefore, as with OCPs, patients and payers might require WFO to address these considerations to support widespread uptake and dissemination of this tool.

There are important limitations to this research. Focus groups were conducted with patients who were health literate, relatively homogeneous socioeconomically, and treated at one tertiary cancer center. Patients seen in community-based oncology practices and from more diverse backgrounds might have different perspectives and concerns; therefore, it will be important to assess the perspectives regarding WFO of more diverse patients treated in varying care settings. Nonetheless, this study was strengthened by our ability to recruit patients with a variety of common cancer diagnoses who had all confronted treatment decisions like those that WFO is expected to address. This is an important advance over past studies of clinical decision support tools that have relied on undergraduates, medical students, or standardized patients.8,9,11,12 Although this required flexibility in the research approach (focus groups conducted both in person and by videoconference), we ultimately recruited a sample size consistent with accepted standards in qualitative methodology,17 which yielded saturation in the perspectives expressed by participants. Furthermore, because WFO is not yet routinely used in practice at the institution where these patients were treated, the slideshow and facilitated discussions were hypothetical. Future studies should confirm and expand on these findings with patients, as well as physicians, using WFO in actual treatment decisions.

As health care shifts from volume-based to value-based reimbursement,2 the importance of decision support tools that aid clinicians in delivering the right treatment to the right patient will increase. These results clarify patient attitudes, preferences, and concerns about WFO, a tool with potential to improve oncology practice. Addressing these perspectives will facilitate the use of WFO, and other decision support tools, to help us realize the promise of precision medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by National Cancer Institute Grant No. P30 CA008748. Presented in part at the 2017 Society of Behavioral Medicine Annual Meeting and Scientific Sessions, San Diego, CA, March 29-April 1, 2017. We thank Jeffrey Keesing, Jennifer Wang, Rachel S. Werk, Erva Kahn, and Val Pocus for assistance with this research. We also thank all participating patients.

Appendix

Fig A1.

Participant responses to the study questionnaire regarding IBM Watson for Oncology trained by Memorial Sloan Kettering. Participants responded to the item: “What would you want IBM Watson for Oncology to consider when it makes a recommendation about your chemotherapy?” Participants could select multiple responses. Participants who selected “other” clarified their responses as: “survival rates from different chemo treatments,” “benefit vs other treatments (endocrine vs radiation vs chemo),” “all scientific resources,” “experience and side effects from previous chemotherapy with overlapping drugs,” “% potential of outcome,” and “other options.”

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Jada G. Hamilton, Margaux Genoff Garzon, Elyse Shuk, Jennifer L. Hay, Chasity Walters, Elena Elkin, Ayca Gucalp, Andrew D. Seidman, Marjorie G. Zauderer, Mark G. Kris

Financial support: Mark G. Kris

Administrative support: Jennifer L. Hay

Provision of study material or patients: Jennifer L. Hay, Andrew S. Epstein, Mark G. Kris

Collection and assembly of data: Jada G. Hamilton, Margaux Genoff Garzon, Joy S. Westerman, Elyse Shuk, Jennifer L. Hay, Chasity Walters, Ayca Gucalp, Marjorie G. Zauderer, Mark G. Kris

Data analysis and interpretation: Jada G. Hamilton, Margaux Genoff Garzon, Joy S. Westerman, Elyse Shuk, Jennifer L. Hay, Chasity Walters, Elena Elkin, Corinna Bertelsen, Jessica Cho, Bobby Daly, Andrew D. Seidman, Andrew S. Epstein

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

“A Tool, Not a Crutch”: Patient Perspectives About IBM Watson for Oncology Trained by Memorial Sloan Kettering

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jop/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Bobby Daly

Leadership: Quadrant Holdings

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Quadrant Holdings (I), CVS Health, Johnson & Johnson, McKesson, Walgreens Boots Alliance, Eli Lilly (I), Walgreens Boots Alliance (I), IBM

Ayca Gucalp

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Innocrin Pharma

Research Funding: Pfizer, Innocrin Pharma, Merck, Novartis

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Innocrin Pharma

Andrew D. Seidman

Honoraria: Genomic Health, Eisai, Genentech/Roche, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Novartis/Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech/Roche, Pfizer, Celgene, Eisai, Novartis

Speakers’ Bureau: Genomic Health, Eisai, Genentech/Roche, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Novartis/Pfizer

Research Funding: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Odonate Therapeutics (Inst), Nektar (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genomic Health, Genentech/Roche, Eisai, Celgene

Marjorie G. Zauderer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Epizyme

Research Funding: MedImmune (Inst), Epizyme (Inst), Polaris (Inst), Sellas Life Sciences (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Mesothelioma Applied Research Foundation

Andrew S. Epstein

Other Relationship: UpToDate

Mark G. Kris

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Regeneron, Pfizer

All Authors

All coauthors are currently employed and compensated by entities having a development and financial interest in the subject matter discussed in this manuscript.

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cavallo J: How Watson for Oncology is advancing personalized patient care. http://www.ascopost.com/issues/june-25-2017/how-watson-for-oncology-is-advancing-personalized-patient-care/

- 2.American Society of Clinical Oncology : The state of cancer care in America, 2017: A report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract 13:e353-e394, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neubauer MA, Hoverman JR, Kolodziej M, et al. : Cost effectiveness of evidence-based treatment guidelines for the treatment of non–small-cell lung cancer in the community setting. J Oncol Pract 6:12-18, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackman DM, Zhang Y, Dalby C, et al. : Cost and survival analysis before and after implementation of Dana-Farber clinical pathways for patients with stage IV non–small-cell lung cancer. J Oncol Pract 13:e346-e352, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoverman JR, Cartwright TH, Patt DA, et al. : Pathways, outcomes, and costs in colon cancer: Retrospective evaluations in two distinct databases. J Oncol Pract 7:52s-59s, 2011. (suppl) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paget L, Han P, Nedza S, et al: Patient-clinician communication: Basic principles and expectations. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/VSRT-Patient-Clinician.pdf.

- 7.Institute of Medicine : Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arkes HR, Shaffer VA, Medow MA: Patients derogate physicians who use a computer-assisted diagnostic aid. Med Decis Making 27:189-202, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaffer VA, Probst CA, Merkle EC, et al. : Why do patients derogate physicians who use a computer-based diagnostic support system? Med Decis Making 33:108-118, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmeira M, Spassova G: Consumer reactions to professionals who use decision aids. Eur J Mark 49:302-326, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porat T, Delaney B, Kostopoulou O: The impact of a diagnostic decision support system on the consultation: perceptions of GPs and patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 17:79, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pezzo MV, Pezzo SP: Physician evaluation after medical errors: Does having a computer decision aid help or hurt in hindsight? Med Decis Making 26:48-56, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel R, Green W, Shahzad MW, et al. : Use of mobile clinical decision support software by junior doctors at a UK teaching hospital: Identification and evaluation of barriers to engagement. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 3:e80, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajizadeh N, Perez Figueroa RE, Uhler LM, et al. : Identifying design considerations for a shared decision aid for use at the point of outpatient clinical care: An ethnographic study at an inner city clinic. J Particip Med 5:e12, 2013 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilsdonk E, Peute LW, Knijnenburg SL, et al. : Factors known to influence acceptance of clinical decision support systems. Stud Health Technol Inform 169:150-154, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolodziej M, Hoverman JR, Garey JS, et al. : Benchmarks for value in cancer care: An analysis of a large commercial population. J Oncol Pract 7:301-306, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krueger RA, Casey MA: Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research (ed 5). Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan DL: Focus Groups As Qualitative Research (ed 2). Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan DL: Focus groups. Annu Rev Sociol 22:129-152, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seal DW, Bogart LM, Ehrhardt AA: Small group dynamics: The utility of focus group discussions as a research method. Group Dyn 2:253-266, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P: The control preferences scale. Can J Nurs Res 29:21-43, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, et al. : The Single Item Literacy Screener: Evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC Fam Pract 7:21, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernard HR: Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Lanham, MD, AltaMira Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyatzis RE: Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green J, Thorogood N: Qualitative Methods for Health Research. London, United Kingdom, Sage Publications, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton MQ: Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res 34:1189-1208, 1999 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creswell JW: Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, et al. : Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 1:1-19, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J: Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haider A, Tanco K, Epner M, et al. : Physicians’ compassion, communication skills, and professionalism with and without physicians’ use of an examination room computer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 4:879-881, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon WJ, Fairhall A, Landman A: Threats to information security: Public health implications. N Engl J Med 377:707-709, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weintraub A: Artificial intelligence is infiltrating medicine: But is it ethical? https://www.forbes.com/sites/arleneweintraub/2018/03/16/artificial-intelligence-is-infiltrating-medicine-but-is-it-ethical/#2126bfad3a24.

- 33.Zon RT, Frame JN, Neuss MN, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement on clinical pathways in oncology. J Oncol Pract 12:261-266, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daly B, Bach PB, Page RD: Financial conflicts of interest among oncology clinical pathway vendors. JAMA Oncol 4:255-257, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zon RT, Edge SB, Page RD, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology criteria for high-quality clinical pathways in oncology. J Oncol Pract 13:207-210, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]