Abstract

Patients with metastatic or advanced cancer are likely to be particularly susceptible to financial hardship for reasons related both to the characteristics of metastatic disease and to the characteristics of the population living with metastatic disease. First, metastatic cancer is a resource-intensive condition with expensive treatment and consistent, high-intensity monitoring. Second, patients diagnosed with metastatic disease are disproportionately uninsured and low income and from racial or ethnic minority groups. These vulnerable subpopulations have higher cancer related financial burden even in earlier stages of illness, potentially resulting from fewer asset reserves, nonexisting or less generous health insurance benefits, and employment in jobs with less flexibility and fewer employment protections. This combination of high financial need and high financial vulnerability makes those with advanced cancer an important population for additional study. In this article, we summarize why financial toxicity is burdensome for patients with advanced disease; review prior work in the metastatic or advanced settings specifically; and close with implications and recommendations for research, practice, and policy.

INTRODUCTION

Financial toxicity, a term used to describe the high cost burden health care places on patients and their families, is a major and underappreciated drain on patients with cancer.1 It is estimated that at least 20% of all patients with cancer experience a significant financial hardship as a result of their cancer, including being unable to pay for care, going into debt, filing for bankruptcy, or making other major changes to household spending.2 How, and how much, patients pay for their care can cause extreme distress and lead to additional negative health behaviors.

Metastatic disease is an extraordinary burden on patients and their families. In addition to treatment intensity and complexity, patients often face substantial anxiety and depression, as well as social stigma associated with terminal illness.3,4 In addition, patients with advanced cancer may expect to shoulder large and persistent financial burden. Furthermore, metastatic disease is disproportionately diagnosed among underserved populations, including racial and ethnic minority and low-income populations. These underserved populations are at high risk of both poor cancer outcomes and financial shocks associated with metastatic cancer, making patients with metastatic cancer an important subpopulation in which to study financial toxicity. To be clear, a focus on metastatic disease is not meant to imply a greater need or importance compared with patients with earlier stage disease. Indeed, much of the literature on financial toxicity has shown that patients at early stages also experience financial hardship.5-7 Yet, we argue that patients with advanced cancer are understudied and potentially predisposed to high, frequent, and compressed burden that makes management unique.

The science on financial toxicity, to date, has focused primarily on the identification of the problem, leaning on convenience sample cohorts and descriptive studies. The stage is set for the next phase of research, including more rigorous population-based studies of risk factors and the testing of interventions that relieve cancer-related financial burden. In this article, we summarize why financial toxicity is burdensome for patients with advanced disease in ways that may differ from patients with earlier stage disease; review prior work in the metastatic and advanced disease settings specifically; and close with a focus on the research, practice, and policy implications for the future.

WHAT IS FINANCIAL TOXICITY?

The concept of financial burden as a source of harm to individual patients has been gaining momentum over the past 5 to 10 years.8-11 Across cancer sites and stages, high financial burden has been linked to lower quality of life,2,12-14 higher emotional distress,15 treatment delay or discontinuation,6 and even increased mortality.16

It is important, however, to distinguish between the following two interrelated but distinct concepts: high cancer related financial burden to individual patients and their families (related to the specific amount of out-of-pocket payments that patients are required to pay for health care services) and high societal costs of cancer care (the total cost of care to society, including payer and patient responsibility, as well as unrecovered provider expenses). The former may lead to individual financial distress caused by high cancer related financial burden, whereas the latter is of concern primarily at the policy level but may not be as relevant to individual patients and caregivers. Here, health insurance matters. Uninsured or self-pay individuals are generally responsible for the full cost of their care unless they are able to navigate the complex structure of safety net resources, including hospital charity care, entitlement programs, manufacturer assistance, and nonprofit organization aid.17,18 Yet the literature is clear; no group, regardless of insurance type or generosity, is fully immune from individual-level financial burden of cancer.2,12,19 It is also worth noting that cancer treatment may not follow standard economic models of choice. The reasons are many (including cost asymmetry of information, imperfect patient-physician agent relationships, high valuation for end-of-life care, and high time-varying individual discount rates) and have been previously explored in the literature.20-24 Regardless of the mechanisms driving this phenomenon, there is strong evidence to suggest that high financial burden is a feature of treatment that many patients with cancer are completely underprepared for and, therefore, is worth studying to improve.

A review of financial hardship in cancer by Altice et al25 developed a typology to further conceptualize the burden associated with cancer care costs as belonging to the following three domains: material hardship, including high out-of-pocket expenses and lost wages; psychological burden from distress and anxiety caused by high cancer costs and lost wages; and cost-related behavioral changes resulting from high cancer care costs, including changes in both medical (including delaying or declining care) and nonmedical spending (including taking money from savings or skipping nonmedical bills). We use this framework to evaluate what is currently known in the metastatic setting and to highlight where patients with metastatic disease may be at increased risk.

WHY IS METASTATIC DISEASE DIFFERENT?

Patients with metastatic or advanced cancer are likely to be susceptible to financial hardship for reasons related to both the characteristics of metastatic disease and the characteristics of the population living with metastatic disease. First, metastatic or advanced cancer is a highly resource-intensive condition. Patients are often very sick and receive advanced (and expensive) treatments, and generally, they spend more time in various care settings, including inpatient care, long-term care, and hospice, than the average patient with cancer.26,27 Many researchers have described a traditional U-shaped curve in cancer care costs,28 one where costs are high at diagnosis, recede during continuing care or remission phases, and increase again at the next line of treatment or toward the end of life. In the metastatic setting, this cycle is compressed, often with multiple courses or lines of treatment in a single year.

Second, patients diagnosed with advanced disease are disproportionately uninsured and low income and from racial or ethnic minority backgrounds, which are well-defined vulnerable populations in health care.29-31 Although it is important to recognize how financial burden can and does affect patients with cancer at all levels of socioeconomic status, low-income and minority patients with cancer have been shown to have higher financial burden, even in earlier stages of illness, potentially as a result of having fewer asset reserves and working in jobs with less flexibility and employment protections and fewer or less generous health care benefits.5,32 This combination of high financial need and high financial vulnerability makes those with advanced cancer an important population for additional study.

As we emphasize the importance of studying cancer care costs in metastatic settings specifically, we acknowledge the many challenges to researching financial toxicity in this population. The personal and emotional hardship associated with any cancer diagnosis, particularly one in the metastatic setting, is well documented.3,33 It is challenging to separate the emotional and psychological response associated with disease itself from that which is incremental as a result of high cost burden. For researchers, the current health care system is a web of dependencies and selection biases that make empirical comparisons difficult. Patients themselves may have difficulty separating distress associated with their disease from distress associated with the cost of their disease and may not be willing to do so, especially during times of severely poor functional status and poor prognosis.

Metastatic disease is notably different from earlier stage disease in its goals for treatment. In the vast majority of patients, treatment in the metastatic setting helps to slow progression, not to eliminate disease completely. Patients and providers may be more willing to discuss financial toxicity in settings where multiple viable curative treatment options allow for straightforward consideration of trade-offs (noting that patients rarely trade-off between curative and noncurative options). Talks of value can often be an unwelcome consideration, in any cancer setting, both at the patient and population levels, but may be even more difficult as prognosis declines. Even where treatment has shown to be low value, which is not uncommon for treatments used in advanced cancer, cultural and political taboo can prevent constructive conversations around cost.1,11,34 Some patients with advanced-stage cancer may overvalue treatment, not understanding that it is unlikely to be curative.35 Empirical estimates from the economic evaluation literature, as well as regulatory approval decisions, place advanced cancer among the conditions with the highest societal willingness to pay globally. To date, most financial toxicity studies have avoided clashing with tough questions around value-based care, preferring correctly to focus on the needs of the individual patient. However, eventually these conversations will converge, and policy-based solutions will require patient input.

Finally, studies of financial toxicity in patients with metastatic disease are constrained by structural and logistical challenges. Practically, there are few patients available and willing to undergo study. Patients with metastatic cancer represent the minority of patients with cancer. Metastatic cancer treatment guidelines are also complex and largely unstructured, rendering robust studies of cost-benefit trade-offs and patient treatment preferences often infeasible. Ramsey and Shankaran36 present a case study of colorectal cancer demonstrating the litany of treatment options, with ranges of total costs and a distinct lack of specific clinical guidance, leaving patients and providers with uncertainty about treatment choice. This uncertainty makes each metastatic case unique and limits the generalizability and transportability of research about financial burden across settings.

Each of the challenges highlighted previously contributes to the general lack of evidence surrounding financial toxicity in the metastatic or advanced cancer setting. Next, we briefly summarize what has been studied in this regard and then comment on areas for future research innovation.

WHAT HAS BEEN SHOWN FOR PATIENTS WITH ADVANCED DISEASE?

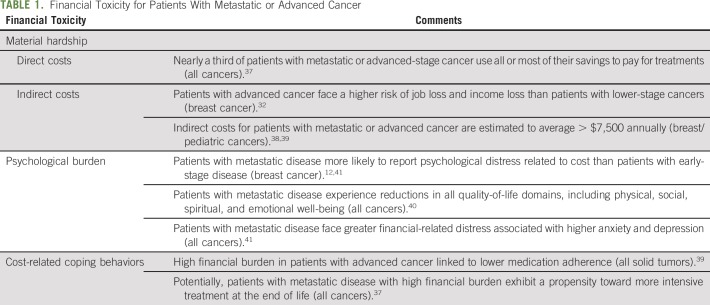

For patients with metastatic or advanced disease, the evidence base is limited, but it is clear that several aspects of cancer related financial burden are exacerbated in this population (Table 1). Overall, literature comparing the magnitude of financial toxicity in advanced versus early-stage disease is somewhat limited. Using the financial burden typology of Altice et al,25 there is evidence of considerable material hardship for patients with metastatic disease, likely as a result of both the complexity of treatment and the vulnerability of this population. One prospective study of patients with advanced cancer found that nearly a third reported using all or most of their savings to pay for cancer care.37 Another found that the risk of any negative financial impact was 14 percentage points higher for those with metastatic versus earlier stage breast cancer, with the majority of this difference resulting from increased rates of job loss or income loss.32

TABLE 1.

Financial Toxicity for Patients With Metastatic or Advanced Cancer

The burden of indirect costs, including lost productivity, is a consistent theme among those with metastatic disease, with a 2013 study reporting an average of $1,584 in annual lost wages due to sick leave and $6,166 in annual lost wages from short-term disability.38 Family members of those with metastatic cancer also report high indirect costs in lost wages or employment as a result of caregiving responsibilities.38,39

Evidence also suggests that those with metastatic disease have higher psychological burden related to their costs than those with earlier stage disease.12 High out-of-pocket costs for patients with metastatic disease are associated with a reduction in all quality-of-life domains, including physical, social, spiritual, and emotional well-being.40 Patients with advanced cancer reporting high financial stress have significantly higher anxiety and depression and lower functional quality of life than patients with no financial-related distress.41 In a recent survey of women with metastatic breast cancer, 68% were worried about financial problems as a result of cancer, 44% reported high cost-related emotional stress, and 31% were worried about the financial stress on their families.43

Although a few studies show that material and psychological hardships are prevalent in this population, less is known about how financial burden affects behavior for patients with metastatic or advance disease. A study that included a majority of patients with advanced-stage disease found that those facing high financial burden had lower medication adherence.42 Surprisingly, patients with advanced cancer experiencing high financial burden have been shown to receive more intensive treatment toward the end of life.37 Many of the studies considering cancer cost–related behavior changes restrict their analyses to patients with early-stage disease or do not stratify by or have no information on cancer stage. The behavioral effects of cancer costs for the metastatic population, therefore, remain largely unstudied.

DISCUSSION: NEED FOR FUTURE RESEARCH, PRACTICE, AND POLICY INNOVATION

The science of financial toxicity (ie, what we understand about how patients respond to high cost burden and how it affects cancer health outcomes) is relatively new, with many unknowns. Such studies in the metastatic setting, especially those focusing on downstream cancer health outcomes, or investigations from larger population studies are relatively rare, which may be explained by a number of social, cultural, structural, and logistical challenges. One of the areas of greatest need is the need for large-scale, nationally representative studies of financial burden and its consequences for patients with metastatic cancer. Convenience sample studies have provided strong hypothesis generation, both in advanced and nonadvanced cancer settings. The current need is for confirmatory research in larger, more representative samples, specifically to inform large-scale policy making and intervention development and implementation. Large-scale observational studies can provide evidence when random assignment is difficult or unethical, but studying patient costs as an outcome in randomized trials should also be pursued.

Despite limited generalizable evidence across a full range of material, psychological, and behavioral outcomes in the metastatic setting, there is some evidence to suggest that financial toxicity can be exceedingly harmful to patients with advanced and nonadvanced disease, caregivers, and society, suggesting that targeted, multifaceted intervention strategies are needed to prevent and mitigate high financial burden. Moreover, strategies for patients with metastatic disease may look different than those for other patients as a result of the timing, intensity, or emotional burden of disease.

Future interventions that help to curb financial toxicity for patients with metastatic cancer should be informed by patient preferences and sensitive to both cultural and structural barriers. In light of the many challenges described earlier, interventions that fail to account for heterogeneity across patient care preferences will fail in their goal to improve quality of care and outcomes. Patient preference work in the metastatic setting is scattered and unfocused. Where applied, preference elicitation (the science of capturing stated consumer preferences) can help a range of stakeholders understand how and why patients make health care choices, aligning incentives to improve outcomes.44 Researchers have used these methods to create decision tools and compare care preferences from patients and providers,45,46 as well as to target or identify high-value care.47,48 Multistakeholder engagement is another rapidly growing solution that seeks to better align patient needs with policies and practice-based interventions designed to achieve desired outcomes.47,49-51 The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute has funded a number of studies that evaluate patient-centered approaches to oncology and survivorship care that offer strong models for multistakeholder engagement.52,53 Patient navigation offers an especially promising approach to help patients navigate the increasingly complex and patchwork resources that currently exist.18,54 Some preliminary work has been done to create setting-specific financial navigation resources; these have been shown to lower patient anxiety about costs and may offer a flexible, patient-centered solution,55,56 but expansion and larger scale evaluation of these programs in both patients with advanced and early-stage cancer are urgently needed.

Finally, we see an immediate need for a transparent and open discussion of value and equity at multiple levels. This includes direct communication between patients and providers about needs and preferences, a difficult but increasingly important discussion. Open discussions about value and equity require trust and meaningful engagement. Medically underserved populations are understandably distrustful of the medical system as a result of a significant history of marginalization. Overcoming an extensive historical and cultural barrier requires us to be more creative about engaging patients in decision making. For example, leveraging peer support and community-based health workers, as has been done successfully in cancer screening, may help to reach these populations more effectively and more meaningfully.57

At a policy level, the growing debate surrounding the cost of cancer care highlights the generalized problem of inequity that this country has yet been unwilling to discuss and address directly. To date, few have been willing to make serious proposals that meaningfully limit all forms of patients’ out-of-pocket cost responsibility. We advocate for a more specific discussion around what the larger patient community is willing to trade off to enact change in health care cost. Overall, our society’s inability to meaningfully address patients’ high costs and perspectives on value (in the metastatic cancer setting, especially) may exacerbate existing disparities between the haves and have-nots, while simultaneously leaving many patients with incurable disease in financial ruin.

Embracing value in cancer care has several key benefits, specifically for vulnerable populations. First, system resources are finite. Value-based approaches that curb inefficient spending necessarily create additional resources to distribute to those most in need. Second, the flexibility of prospective valuation allows for subgroup variation and differential efficiency estimates, for example, for specific racial or ethnic minorities whose risk and benefits may differ from the majority. Finally, value is color blind. Health care is full of anecdotal (and empirical) evidence of discriminatory care. When personalized value-driven care is delivered, we compare alternatives across an even plane.

There is nothing as simple, or uncontroversial, as issuing a call for national discussion. Yet, there are few actionable paths available universally. For a more nuanced discussion of physician-patient communication surrounding cost, we direct the reader to a few sources, including those by Ubel et al,11 Zafar et al,34 and Henrikson et al.58 Each has made similar calls to action, while providing clinical perspectives and personal experiences. However, the problem of cancer care costs extends beyond the clinical encounter to both spending trade-offs occurring in patients’ households as well as spending trade-offs occurring in boardrooms and policy arenas. Increased research in this area has the potential to improve the quality of cancer care but only if trade-offs are explicitly valued.

The financial burden of cancer treatment is a serious and growing problem. For patients with metastatic or advanced disease who are already coping with the physical and emotional demands of their disease, financial burden only adds greater hardship and increased complexity. It is important to improve our understanding of the material, psychological, and behavioral effects of high direct and indirect costs associated with metastatic disease and how this burden is differentially experienced by patients with metastatic disease, an already vulnerable population. It is also important to find ways to address financial needs through early communication, better cost transparency, and navigation to financial support resources. How physicians and researchers respond to the need for radical change in this setting will determine how future patients with advanced cancer view their cancer care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by the University of North Carolina’s National Cancer Institute–funded Cancer Care Quality Training Program (Grant No. R25 CA116339; PIs, Wheeler and Basch). Also supported, in part, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Special Interest Project titled “Economic Burden of Metastatic Breast Cancer Across the Life Course” (Grant No. 3-U48-DP005017-04S4; CDC-SIP 17-004; PIs, Wheeler and Trogdon) and by the Pfizer/National Comprehensive Cancer Network Independent Grant for Learning and Change award titled “Implementing and Evaluating Medication Assistance Programming in Metastatic Breast Cancer” (PIs, Wheeler and Rosenstein).

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Financial Toxicity in Advanced and Metastatic Cancer: Overburdened and Underprepared

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jop/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Jennifer C. Spencer

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Stephanie B. Wheeler

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pfizer

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zafar SY. Financial toxicity of cancer care: It’s time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108:djv370. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Jr, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: Findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:259–267. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willis K, Lewis S, Ng F, et al. The experience of living with metastatic breast cancer: A review of the literature. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36:514–542. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.896364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendriksen E, Williams E, Sporn N, et al. Worried together: A qualitative study of shared anxiety in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer and their family caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1035–1041. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagsi R, Pottow JAE, Griffith KA, et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: Experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1269–1276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaisaeng N, Harpe SE, Carroll NV. Out-of-pocket costs and oral cancer medication discontinuation in the elderly. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20:669–675. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.7.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narang AK, Nicholas LH. Out-of-pocket spending and financial burden among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:757–765. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Connor JM, Kircher SM, de Souza JA. Financial toxicity in cancer care. J Community Support Oncol. 2016;14:101–106. doi: 10.12788/jcso.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part I: A new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park) 2013;27:80–81, 149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part II: How can we help with the burden of treatment-related costs? Oncology (Williston Park) 2013;27:253–254, 256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure: Out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1484–1486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1306826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zafar SY, Mcneil RB, Thomas CM, et al. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: A prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:145–150. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, et al. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1732–1740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chongpison Y, Hornbrook MC, Harris RB, et al. Self-reported depression and perceived financial burden among long-term rectal cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2016;25:1350–1356. doi: 10.1002/pon.3957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:980–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell A, Muluneh B, Patel R, et al. Pharmaceutical assistance programs for cancer patients in the era of orally administered chemotherapeutics. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2018;24:424–432. doi: 10.1177/1078155217719585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spencer JC, Samuel CA, Rosenstein DL, et al. Oncology navigators’ perceptions of cancer-related financial burden and financial assistance resources. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:1315–1321. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3958-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shih YT, Xu Y, Liu L, et al. Rising prices of targeted oral anticancer medications and associated financial burden on Medicare beneficiaries. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2482–2489. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gafni A, Charles C, Whelan T. The physician-patient encounter: The physician as a perfect agent for the patient versus the informed treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:347–354. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuchs V.Time preference and health: An exploratory studyinEconomic Aspects of Health Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1982. pp93–120. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradford WD. The association between individual time preferences and health maintenance habits. Med Decis Making. 2010;30:99–112. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09342276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blomqvist A. The doctor as double agent: Information asymmetry, health insurance, and medical care. J Health Econ. 1991;10:411–432. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(91)90023-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, et al. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;109:djw205. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Accordino MK, Wright JD, Vasan S, et al. Use and costs of disease monitoring in women with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2820–2826. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chastek B, Kulakodlu M, Valluri S, et al. Impact of metastatic colorectal cancer stage and number of treatment courses on patient health care costs and utilization. Postgrad Med. 2013;125:73–82. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2013.03.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:630–641. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halpern MT, Bian J, Ward EM, et al. Insurance status and stage of cancer at diagnosis among women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:403–411. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reeder-Hayes KE, Wheeler SB, Mayer DK. Health disparities across the breast cancer continuum. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2015;31:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henley SJ, King JB, German RR, et al. Surveillance of screening-detected cancers (colon and rectum, breast, and cervix) - United States, 2004-2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010;59:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wheeler SB, Spencer JC, Pinheiro LC, et al. Financial impact of breast cancer in black versus white women. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1695–1701. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimmermann C, Burman D, Swami N, et al. Determinants of quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:621–629. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0866-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zafar SY, Newcomer LN, McCarthy J, et al. How should we intervene on the financial toxicity of cancer care? One shot, four perspectives. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:35–39. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_174893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramsey S, Shankaran V. Managing the financial impact of cancer treatment: The role of clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:1037–1042. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tucker-Seeley RD, Abel GA, Uno H, et al. Financial hardship and the intensity of medical care received near death. Psychooncology. 2015;24:572–578. doi: 10.1002/pon.3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wan Y, Gao X, Mehta S, et al. Indirect costs associated with metastatic breast cancer. J Med Econ. 2013;16:1169–1178. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.826228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bona K, Dussel V, Orellana L, et al. Economic impact of advanced pediatric cancer on families. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta D, Lis CG, Grutsch JF. Perceived cancer-related financial difficulty: Implications for patient satisfaction with quality of life in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:1051–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hlubocky FJ, Cella D, Sher TG, et al. Financial burdens (FB), quality of life, and psychological distress among advanced cancer patients (ACP) in phase I trials and their spousal caregivers (SC) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl 15; abstr 6117) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, et al. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:162–167. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wheeler SB, Spencer J, Manning ML, et al. Cancer-related financial burden among patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(suppl 30; abstr 32) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: A user’s guide. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:661–677. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mühlbacher AC, Nübling M. Analysis of physicians’ perspectives versus patients’ preferences: Direct assessment and discrete choice experiments in the therapy of multiple myeloma. Eur J Health Econ. 2011;12:193–203. doi: 10.1007/s10198-010-0218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson A, Thomson R. Variability in patient preferences for participating in medical decision making: Implication for the use of decision support tools. Qual Health Care. 2001;10(suppl 1):i34–i38. doi: 10.1136/qhc.0100034... [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: Current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2003;2:55–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shah KK, Tsuchiya A, Wailoo AJ. Valuing health at the end of life: A stated preference discrete choice experiment. Soc Sci Med. 2015;124:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, et al. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1692–1701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2878-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Concannon TW, Meissner P, Grunbaum JA, et al. A new taxonomy for stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:985–991. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2037-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clark MD, Determann D, Petrou S, et al. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: A review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32:883–902. doi: 10.1007/s40273-014-0170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mead H. Evaluating different types of cancer survivorship care. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-Mead158-English-Abstract.pdf

- 53.Scholle S. Evaluating a new patient-centered approach for cancer care in oncology offices. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-Scholle113-English-Abstract.pdf [PubMed]

- 54.Sherman DE. Transforming practices through the Oncology Care Model: Financial toxicity and counseling. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:519–522. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.023655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shankaran V, Leahy T, Steelquist J, et al. Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e122–e129. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.024927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shankaran V, Linden H, Steelquist J, et al. Development of a financial literacy course for patients with newly diagnosed cancer. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(suppl 3):S58–S64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feltner FJ, Ely GE, Whitler ET, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in providing outreach and education for colorectal cancer screening in Appalachian Kentucky. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51:430–440. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2012.657296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Henrikson NB, Tuzzio L, Loggers ET, et al. Patient and oncologist discussions about cancer care costs. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:961–967. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2050-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]