Abstract

An important goal in biology is to predict from sequence data the high-resolution structures of proteins and the interactions that occur between them. In this paper, we describe a computational approach that can make these types of predictions for a series of coiled-coil dimers. Our method comprises a dual strategy that augments extensive conformational sampling with molecular mechanics minimization. To test the performance of the method, we designed six heterodimeric coiled coils with a range of stabilities and solved x-ray crystal structures for three of them. The stabilities and structures predicted by the calculations agree very well with experimental data: the average error in unfolding free energies is <1 kcal/mol, and nonhydrogen atoms in the predicted structures superimpose onto the experimental structures with rms deviations <0.7 Å. We have also tested the method on a series of homodimers derived from vitellogenin-binding protein. The predicted relative stabilities of the homodimers show excellent agreement with previously published experimental measurements. A critical step in our procedure is to use energy minimization to relax side-chain geometries initially selected from a rotamer library. Our results show that computational methods can predict interaction specificities that are in good agreement with experimental data.

The goal of predicting protein interactions is a challenging task, even in cases where high-quality structural data are available. Making such predictions from sequence alone is beyond the reach of existing computational methods. We approach this problem by studying protein–protein interactions in a simple motif: the coiled coil. Here we describe our work predicting the structure and stability of a series of coiled-coil peptides by using a computational method that combines a fast conformational search procedure with molecular mechanics minimization.

The coiled coil is among the most common of all protein–protein interaction motifs. Computational analysis suggests that it is found in ≈5% of proteins in eukaryotic genomes (1). Many biological roles have been identified for coiled coils in diverse processes, such as transcription, membrane fusion, and chromosome segregation (see, for example, refs. 1–4). In most known examples, the coiled coil is involved in protein–protein interactions.

Coiled coils consist of two or more α helices that wrap around each other with a slight superhelical twist. Their regular structure results from a characteristic repeating heptad of amino acids, denoted (abcdefg)n, in which the a and d positions are predominantly hydrophobic, and the e and g positions are typically charged or polar. The a and d positions make up the core of the coiled-coil interface, whereas the e and g positions occupy the region between the core and the solvent. The repeating heptad allows the motif to be predicted accurately from sequence data (5, 6). The structural regularity also provides a benefit in molecular modeling. With these advantages, coiled coils offer an opportunity to test methods for predicting interaction specificities and to analyze the computational challenges that confront such a task.

Several different types of interactions that influence partner selection among coiled coils have previously been exploited for prediction or design. Simple scoring rules based on counting the number of putative attractions and repulsions between charged g- and e-position residues have some predictive value (7–9). Singh and Kim recently introduced a new computational framework for addressing the partnering problem in coiled coils that includes interactions at additional positions (10). In this paper, we address the role of hydrophobic residues at the a and d positions in determining interaction specificity. We show that computational modeling of coiled-coil structures can be used to predict interaction energy differences that agree quantitatively with experimental results.

There are several obstacles to predicting protein structure accurately enough to describe interactions. The conformational space accessible to even a small protein is large and impossible to sample exhaustively. Further, protein structures are very plastic. Even when an approximate structure is known, small sequence-specific adjustments in side-chain and backbone conformation are difficult to incorporate into models. In our work on coiled coils, we address these issues by using three strategies. First, following Harbury et al. (11, 12), we use Crick's parameterization of the coiled coil to limit the conformational space accessible to the protein backbone (13). Second, we use an efficient search algorithm to sample the large side-chain conformational space of coiled-coil heterodimers. Third, we introduce a final minimization step to fine-tune the backbone and side-chain geometry of our predicted structure. The first two strategies address the problem of a large search space, whereas the third is critical for achieving quantitative estimates of interaction energies.

Materials and Methods

Peptide Synthesis and Characterization.

Six peptides with sequences given in Fig. 1 were synthesized and purified by reverse-phase HPLC, as previously described (14). Purity was >95%, and masses were verified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA).

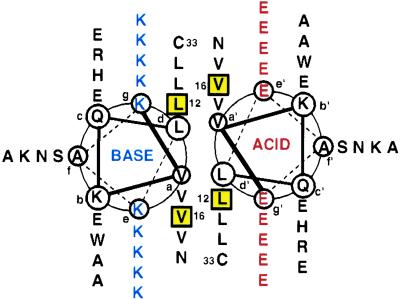

Figure 1.

Helical wheel diagram of the heterodimeric coiled coil GABH. Substitutions of Val, Ile, and Leu were made at positions d12 and a16 (yellow boxes) to give six peptides: ALIBLL, ALLBLL, AIVBLL, ALLBIV, ALIBIV, and AIVBIV (notation: Acidd12a16Based12a16). The linear sequence is: Ac-(E/K)VKQL(E/K)A(E/K)VEEd12(E/K)S(E/K)a16WHL(E/K)N(E/K)VARL(E/K)K(E/K)NAEC(E/K)A-NH2; the ACID peptide has E and the BASE peptide has K at positions in parentheses.

Circular Dichroism (CD).

CD spectra were collected at 25°C in PBS (50 mM sodium phosphate/150 mM sodium chloride) at pH 7.0 by using an Aviv (Lakewood, NJ) 62A/DS CD spectrometer. Denaturation of peptides by guanidinium chloride (Gdm⋅HCl) was monitored at 222 nm. Concentrations were determined by the method of Edelhoch (15). Unfolding curves were fit, assuming a two-state transition, to give Gdm⋅HCl concentrations at half-denaturation ([Gdm⋅HCl]1/2), m values (the dependence of ΔG on [Gdm⋅HCl]), and free energies of unfolding in the absence of Gdm⋅HCl (ΔGu) (Table 1). Because upper baselines were not always well defined, these were assigned a slope of zero; the average deviation for fits performed with and without this constraint was 0.16 kcal/mol.

Table 1.

Relative unfolding free energies in the absence of Gdm⋅HCl (ΔGu, kcal/mol), the dependence of ΔGu on [Gdm⋅HCl] (m, kcal/mol⋅M) and the concentration of Gdm⋅HCl where the peptide is half unfolded ([Gdm⋅HCl]1/2, M) for all GABH peptides

| Peptide | ΔGu | m | [Gdm⋅HCl]1/2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALIBLL | 11.3 (0.4) | 1.9 | 5.8 |

| ALLBLL | 9.8 (0.3) | 1.8 | 5.4 |

| AIVBLL | 7.4 (0.2) | 1.7 | 4.5 |

| ALLBIV | 7.0 (0.1) | 1.6 | 4.3 |

| ALIBIV | 6.1 (0.1) | 1.6 | 3.9 |

| AIVBIV | 4.4 (0.1) | 1.5 | 2.8 |

Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Sedimentation Equilibrium.

Sedimentation equilibrium experiments at 5, 10, and 25 μM were performed after dialyzing against PBS (pH 7.0) using a Beckman XLA-90 analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter). Data were collected after equilibration was verified (18–24 h) at 25,000, 30,000, and 35,000 rpm at 25°C. Data were fit to a single ideal species. Partial specific volumes and solvent density were calculated from the amino acid sequence and solvent composition, respectively (16).

Crystallography.

Initial crystallization conditions for peptides AIVBLL, ALIBLL, and ALLBLL were identified by using Crystal Kits I and II (Hampton Research, Riverside, CA). Protein stocks at 10 mg/ml in water were mixed 1 μl:1 μl with buffer and equilibrated against the well reservoir using the hanging drop method. For all three peptides, crystals could be grown from 18–20% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 4000/0.1 M Na Hepes (pH 7.7)/10% 2-propanol. Crystals were flash-frozen in a nitrogen stream after soaking briefly in a cryoprotectant solution of the well buffer plus 15% PEG 400. All three peptides crystallized with the same packing in the space group P41212.

Diffraction data were collected at beamline X4A at the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY) with a Quantum IV detector (Area Detector Systems Corporation, Poway, CA). Data were integrated and scaled with the programs denzo and scalepack (17); statistics of the data collection and refinement are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Peptide | λ, Å | Completeness, % | Rmerge,* % | Data resolution, Å | Refinement resolution, Å | Nonhydrogen atoms | Waters | Reflections | Rcryst/Rfree,† % | rms deviations (bonds, Å/angles, °) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIVBLL | 0.9763 | 98.9 | 6.0 | 35–1.85 | 30–1.9 | 1,705 | 288 | 23,529 | 23.2/27.6 | 0.018/0.99 |

| ALLBLL | 0.9763 | 98.3 | 4.0 | 35–2.00 | 10–2.1 | 1,650 | 174 | 17,771 | 24.2/29.6 | 0.013/1.40 |

| ALIBLL | 1.0093 | 97.5 | 6.0 | 35–2.05 | 20–2.14 | 1,595 | 113 | 16,580 | 25.2/30.2 | 0.004/0.83 |

Rmerge = ∑∑j|Ij(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/∑∑j|Ij(hkl)|, where I is intensity.

Rcryst (Rfree) = ∑∥Fobs(hkl)| − |Fcalc(hkl)∥/∑|Fobs(hkl)|, where Fobs and Fcalc are observed and calculated structure factors. Ten percent of reflections were excluded to compute Rfree.

Initial phases were determined by using the program amore (18). The model for the molecular replacement procedure was generated by using Stage 1 of our computational procedure (see below). Models constructed from 12 different backbones and various side-chain rotamer possibilities were tested (the a- and d-position residues of peptide ALIBLL were used for all data sets), which yielded initial phases for peptides AIVBLL and ALLBLL. Peptide ALIBLL was refined with initial phases from AIVBLL. Model building was done with the program o (19), and refinement calculations were done with the program cns (20).

We took precautions to eliminate phase bias from the refinement procedure: all initial models were subjected to high-temperature (5,000 K) simulated annealing, all model building was done against composite omit maps, and side-chains at positions d12 and a16 were initially refined as Ala and rebuilt only when their density was clear in the maps.

Computation of Structure and Energies for Coiled Coils.

To facilitate modeling of the peptides in Fig. 1, we represented each of them as an infinitely repeating segment consisting of residues g8–f28. The difference between the actual structure and the assumption of an infinite coil is minimal at positions d12 and a16. For calculations on vitellogenin-binding protein (VBP), the coiled coil was represented by a sequence consisting of residues 71–94 of the 96-residue constructs in ref. 21. Residue 72 (an a-position Val) was constrained to have the gauche (−) rotamer, which is favored in this position in coiled coils, to provide a boundary condition.

To address the difficulty of modeling solvent-exposed charged residues, we truncated the e and g residues beyond Cδ, substituting these residues with aminopentanoic acid (here denoted Apa). All b, c, and f positions were Ala in the calculations. Apa residues in the e and g positions were assigned conformations consistent with the formation of salt bridges, where these sites comprised Lys/Glu or Arg/Glu pairs. The only other inputs to the calculation were the sequence, oligomerization state and register assignment of the coiled coil of interest. This type of information is available from coiled-coil prediction programs such as multicoil (6).

Stage 1 = Discrete Search by Using Dead-End Elimination (DEE)/A* (NOMIN).

For each backbone in a predetermined library, low-energy side-chain configurations were identified by using a combination of DEE (22, 23) and an A* search algorithm (24). The standard DEE elimination criterion was modified by introducing a cut-off energy of 30 kcal/mol. This guaranteed that all solutions within this energy of the global minimum were retained in the search. The A* search procedure was used to sort solutions that survived DEE and return up to 10,000 of them per backbone in order of increasing energy. We implemented the A* search with bounds as described in ref. 24. Details are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org.

Side-Chain and Backbone Libraries.

Default bond lengths and angles from the CHARMM PARAM19 parameter set were used for all rotamers (25). Side-chain torsion values were taken from Dunbrack's August 1999 library for backbones with φ = −60 and ψ = −50 (26). The rotamers used are given in the supporting information on the PNAS web site. The number of rotamers per residue was six (Leu), six (Ile), three (Val), and six (Apa). Apa was assigned one of two rotamers (χ1 = −70, χ2 = 180; χ1=180, χ2 = 180) when assumed to be in a salt-bridging geometry. Subrotamers were constructed for all residues by including +/−10° from the parent χ1 and χ2.

A library of 48 idealized coiled-coil backbones described by the parameters R0 = {4.8, 4.9, 5.0 Å}, ω0 = {0.055, 0.06, 0.065, 0.07 radians/residue}, and φ = {0.3, 0.35, 0.4 radians} was generated as previously described (11). These values bracket those that describe the GCN4-p1 dimer structure.

Side-Chain Rotamer Energy Terms for DEE/A* Calculations.

Interaction energies between side chains and the template (backbone plus b-, c-, and f-position Ala) and among side chains were calculated by using the subrotamer method of Mendes et al. (27), which replaces the energy between rotamers with a weighted average of the energies between a set of subrotamers. The equations used are given in the supporting information on the PNAS web site. This procedure compensates for the inflexibility of library rotamers. Side-chain subrotamer energies were computed by using the program charmm and the PARAM19 force field (25) with 90% van der Waals radii. No electrostatic terms were included. Energies between side chains on residues with >10-Å separation between Cβ atoms were set to 0.0 kcal/mol, and pairwise energies between subrotamers >100 kcal/mol were set to a uniform large value (106 kcal/mol).

Stage 2 = Fixed Backbone Side-Chain Minimization (MIN-SC) or Full Backbone Minimization (MIN-FULL): Geometry Minimization.

Up to 3,500 unique side-chain configurations identified by the A* search were minimized using the PARAM19 potential with 100% van der Waals radii, no electrostatics, and the addition of an explicit hydrogen-bonding term, as described in refs. 11 and 28 and in the supporting information on the PNAS web site. Minimization allowing compensating changes in side-chain and backbone geometry was carried out as described refs. 11 and 12.

Energy Corrections.

Stages 1 and 2 were carried out in the gas phase. To estimate energies in aqueous solution, an empirical solvation correction was applied. We used the solvation parameters of Wesson and Eisenberg (29); however, we chose an atomic solvation coefficient of zero for Met sulfur. Solvent accessible surface areas were computed with charmm by using the method of Lee and Richards and a probe radius of 1.4 Å (30).

Molecular mechanics energies calculated for different sequences and structures were converted to relative unfolding free energies by using the thermodynamic cycle of Harbury et al. (12), with experimental helix propensities taken from ref. 31. This is described in more detail in the supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Results

Design of a Model Heterodimeric Coiled Coil.

Our computational method was designed to predict structures and relative unfolding free energies for parallel two-stranded coiled coils with different core sequences. Experimental testing of the calculations required a series of peptides that (i) span a range of stabilities and (ii) remain dimeric and parallel across this range. We chose to study a set of heterodimeric complexes to address factors that influence coiled-coil partner selection.

To meet these criteria, we designed a series of heterodimeric coiled coils that we denote GABH, for GCN4 Acid/Base Heterodimer (Fig. 1). The stability of members of the family can be modulated through the substitution of different hydrophobic residues (Leu, Ile, Val) at positions d12 and a16. Heterodimerization is enforced by oppositely charged residues in the e and g positions of partnering strands (14). With this design, three ACID peptides with Glu at all e and g positions (ALL, AIV, ALI) and two BASE peptides with Lys at all e and g positions (BLL and BIV) can be combined to generate six different heterodimers.

Ensuring the specific formation of dimers, rather than of trimers or tetramers, presents a special challenge in designed coiled coils. Destabilizing mutations in the core of coiled coils frequently lead to a change in oligomerization state (32). The GABH peptides contain several features that promote dimer specificity. First, the opposite charges on the ACID and BASE strands favor heterodimers over homo- and heterotrimers, in which similar-charged residues would be opposed at a minimum of one interface. Second, Asn is included at position a30 and Cys [which can form a disulfide bond with favorable geometry in a dimer (33)] at position d33 to promote dimer specificity (34). When oxidized, Cys at d33 also enforces a parallel orientation of the two strands and allows easy purification of covalently linked heterodimers.

The b, c, and f positions of GABH were taken from the sequence of GCN4-p1, with the exception of position b17, which was changed from Tyr to Trp. Many peptides incorporating surface residues from GCN4-p1 crystallize readily (see ref. 35 and refs. therein).

Characterization of Heterodimer Variants.

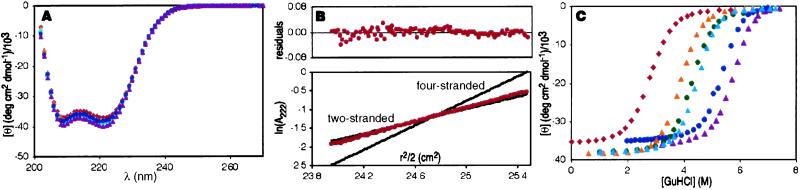

The six GABH heterodimers are ≈100% helical and have CD spectra characteristic of coiled coils (Fig. 2A). Analytical ultracentrifugation data for all six peptides fit well to equations describing a single molecular species in solution (Fig. 2B). The observed molecular weights are in good agreement with those expected for the disulfide-linked dimer (for each peptide, the average mass ratio observed/calculated = 1.1/1). The relative stabilities of the six two-stranded coiled coils were determined by chemically induced unfolding with Gdm⋅HCl (Fig. 2C). Unfolding was fully reversible. The heterodimer stabilities span a range of 6.6 kcal/mol (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Characterization of GABH peptides. (A) CD spectra for the six peptides show that all are highly helical and exhibit minima of similar magnitude at 208 and 222 nm, which is characteristic of coiled coils. (B) Analytical ultracentrifugation data for the least stable peptide, AIVBIV at 25 μM and 25°C. The data for all six peptides can be fit to give the expected mass for a two-stranded species, with random residuals. (C) The [Gdm⋅HCl] dependence of the CD signal at 222 nm for peptides at 10 μM and 25°C. AIVBIV = red, ALIBIV = orange, ALLBIV = green, AIVBLL = light blue, ALLBLL = dark blue, ALIBLL = purple.

Crystallography.

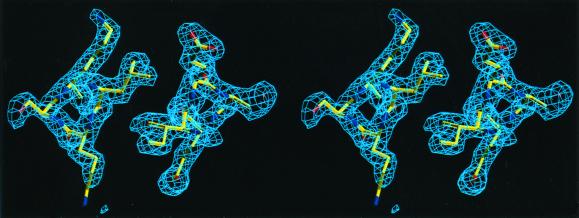

We solved the crystal structures of ALLBLL, ALIBLL, and AIVBLL. All three peptides crystallized under similar conditions with the same packing of three copies of the dimer per asymmetric unit. The AIVBLL structure is of excellent quality (Table 2). The ALLBLL and ALIBLL structures have significantly higher average B factors (45 Å2 for ALLBLL and 43 Å2 for ALIBLL, compared with 28 Å2 for AIVBLL), and poorer refinement statistics.

The peptides all adopt the expected structure of a two-stranded parallel heterodimeric coiled coil. The C terminus is ordered in some copies of the structures and shows how a disulfide bond can be accommodated at the d position of a coiled coil with both Cys residues occupying a χ1=180° rotamer. Most, although not all, of the e- and g-position residues form salt-bridging interactions across the hydrophobic interface, as anticipated in the design. In several cases, the density for these side chains is missing, consistent with a dynamic structure observed by NMR for e- and g-position residues in a similar peptide (36). For AIVBLL and ALLBLL, variations in core packing are found among the three copies of the dimer in the asymmetric unit (Table 3). Fig. 3B shows one arrangement of residues found at position d12 in the core of AIVBLL. In ALIBLL and ALLBLL a few core sites have high B factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rotamer combinations observed in the crystal structures and how they were ranked by different calculations

| Peptide | X-ray

|

Computation

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copy no. in asymmetric unit | Rotamer*

|

Method | Relative energy | Rank | ||||

| Ad12 | Bd12 | Aa12 | Ba16 | |||||

| AIV/BLL | 1, 2 | I1 | L2 | V1 | L1 | MIN-FULL | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | I1 | L2 | V1 | L2 | 0.3 | 5 | ||

| 1, 2 | I1 | L2 | V1 | L1 | MIN-SC | 1.6 | 3 | |

| 3 | I1 | L2 | V1 | L2 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 1, 2 | I1 | L2 | V1 | L1 | NOMIN | 50.4 | 488 | |

| 3 | I1 | L2 | V1 | L2 | 0 | 1 | ||

| ALL/BLL | 1 | L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 | MIN-FULL | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | L2 | L2 | L1 | L2† | 0.9 | 2 | ||

| 3 | L2 | L2 | L1‡ | L1‡ | 2.5 | 38 | ||

| 1 | L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 | MIN-SC | 8.9 | 142 | |

| 2 | L2 | L2 | L1 | L2† | 2.7 | 5 | ||

| 3 | L2 | L2 | L1‡ | L1‡ | 10.2 | 180 | ||

| 1 | L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 | NOMIN | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | L2 | L2 | L1 | L2† | 23.6 | 54 | ||

| 3 | L2 | L2 | L1‡ | L1‡ | 57.7 | 284 | ||

| ALI/BLL | 1, 2, 3 | L2 | L2 | I1 | L1 | MIN-FULL | 0.5 | 3 |

| 1, 2, 3 | L2 | L2 | I1 | L1 | MIN-SC | 3.0 | 5 | |

| 1, 2, 3 | L2 | L2 | I1 | L1 | NOMIN | 30.0 | 156 | |

The three copies of the dimer in the asymmetric unit are numbered 1–3. Calculated energies (kcal/mol) and ranks are given relative to the lowest energy predicted structure.

The rotamer notation is Residue# = (χ1, χ2) with I1 = (−, trans); L1 = (trans, +); L2 = (−, trans); V1 = (trans).

B factor >65 Å2 for one Cδ.

Distorted χ1 angles at these sites: χ1 = −142°, −158° were assigned as trans.

Figure 3.

Stereo view of a composite omit map for AIVBLL showing the packing of Ile d12 against Leu d12 in the core (at 1.6σ). The view is from the N terminus and includes residues 12–15.

Comparison of Computed and Experimental Structures and Energies.

Computational predictions of the structure and unfolding energy (relative to that of ALIBLL) were carried out for each of the experimentally characterized peptides. In addition, we performed calculations on a series of homodimeric coiled coils derived from VBP that have been characterized by Moitra et al. (21).

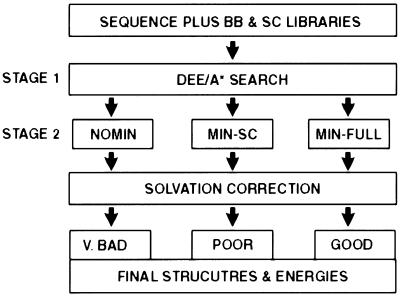

The calculations consist of two stages designed first to limit and subsequently to refine the protein conformational space (Fig. 4). Stage 1 (NOMIN) involves an intensive search through a discrete space comprising idealized two-stranded coiled-coil backbones and canonical side-chain rotamers (26). The DEE and A* algorithms are used to reduce the set of 5 × 109 possible conformations that can be constructed from these choices to a subset of up to 3,500 candidates to be further evaluated (24). In Stage 2, a molecular mechanics minimization procedure is added to refine the Stage 1 candidate structures. We tested two different approaches. In the first, only the side chains are minimized on a fixed backbone (MIN-SC). In the second, flexibility is introduced for both the side-chain and backbone atoms (MIN-FULL) (11).

Figure 4.

Flow chart describing the computational methods. BB, backbone; SC, side chain.

As described below, structures and relative stabilities predicted by using the NOMIN or MIN-SC methods differ significantly from experimental data. The MIN-FULL calculation, however, yields relative stabilities that agree very well with experiment and structures that superimpose on the x-ray structures to within 0.7 Å.

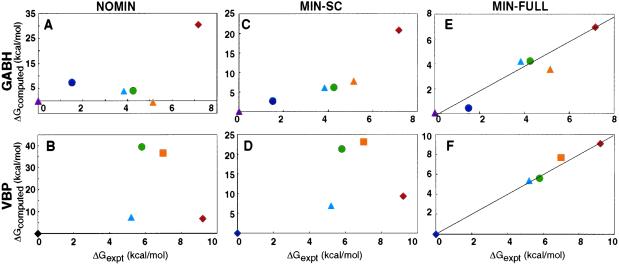

Fig. 5 shows predicted relative stabilities of the different GABH and VBP structures and compares these with experimental values. In Fig. 5 A and B, the NOMIN energies do not agree with experiment—the stability of AIVBIV is greatly underestimated, and that of ALIBIV overestimated. The stability of the d = Ile and d = Val mutants of VBP are also significantly underestimated. MIN-SC improves the agreement of computed and measured stabilities, particularly for the GABH peptides. In Fig. 5C, the overall ordering of stabilities is now correct, although that of AIVBIV is still underestimated by more than 13 kcal/mol. The VBP energies in Fig. 5D are not correctly ordered and show large errors.

Figure 5.

Comparison of experimental and calculated relative free energies of unfolding. All data are reported in kcal/mol relative to the most stable peptide. Note the different scales for different plots. A, C, and E give results for GABH peptides, and B, D, and F give results for VBP derivatives: (A and B) NOMIN calculations followed by a solvation correction; (C and D) MIN-SC calculations plus a solvation correction; (E and F) MIN-FULL calculation. Colors are as in Fig. 2 for GABH. For VBP d position mutants, L = dark blue, M = light blue, I = green, V = orange, A = red.

Our best predictions come from calculations that use full-backbone and side-chain minimization (MIN-FULL). The predicted unfolding free energy differences for MIN-FULL calculations are compared with experiment in Fig. 5 E and F. Quantitative agreement is excellent, with an average error of less than 0.7 kcal/mol for the GABH series and 0.5 kcal/mol for the VBP mutants.

Side-chain rotamers observed in the crystal structures of ALIBLL, ALLBLL, and AIVBLL are compared with rotamers predicted by each type of calculation in Table 3. The NOMIN calculation ranks many of the experimentally observed conformations poorly (see the last column of Table 3), and predicts them to be high in energy relative to other structures (second to last column). The MIN-SC calculation performs better, ranking some of the experimentally observed rotamer choices among the top five predictions. The energy gaps between the best predicted structures and several of the experimentally observed rotamer choices are a few kcal/mol using the MIN-SC method. The MIN-FULL calculation shows the best performance. This method ranks all but one of the experimentally observed rotamer combinations within the top five structures predicted by the calculation. The one exception is the third copy of ALLBLL, which adopts a strained conformation for χ1 of position d12 and is ranked poorly in all calculations (see Table 3). The energy differences between the rest of the experimentally observed conformations and the best structure predicted by MIN-FULL are less than 1 kcal/mol.

Thus, within a 0.5–1.0 kcal/mol error, the MIN-FULL calculation identifies the correct rotamers. Furthermore, the calculations suggest there are multiple low-energy packing states for some of these peptides, which is confirmed by the observation of alternate packing arrangements in different copies of the experimental structures.

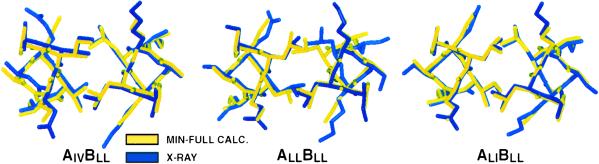

Fig. 6 shows structures from the MIN-FULL calculation superimposed with experimental structures for ALLBLL, AIVBLL, and ALIBLL. The most frequently observed or best-defined rotamer configuration from the crystal structure is shown, along with the calculated structure that matches it (see Table 3). The agreement is very good for all peptides —the average rms deviation for all nonhydrogen atoms included in the model is <0.7 Å.

Figure 6.

Superposition of the x-ray and MIN-FULL-calculated structures. The structures shown correspond to the first entries in Table 3 for each peptide. The view is from the C terminus of the peptide and includes positions a16 and d12.

Discussion

The coiled coil is a common and important protein interaction motif that is involved in a wide variety of biological processes. As a step toward our goal of predicting coiled-coil interactions from sequence data, we have developed a computational method that can predict the influence of hydrophobic core mutations on interaction selectivity. As seen in Fig. 5 E and F, our computational method makes quantitatively correct predictions about the relative stabilities of different coiled-coil sequences. This is accomplished with a simple energy function that considers only strain energy, van der Waals packing energy, a solvation term, and amino acid helix propensities.

The calculations can be used to predict coiled-coil partnering preferences that arise from core packing. Among the GABH peptides, for example, the interaction of BLL with ALI is predicted to be ≈4 kcal/mol more favorable than the interaction with AIV, and the interaction of BIV with ALL is predicted to be ≈3 kcal/mol more favorable than the interaction with AIV, consistent with experimental measurements. Residues that are known to favor trimer or tetramer formation over dimerization (such as Ile or Val at the d position) are found, as anticipated, to destabilize the heterodimers studied here (32).

The calculated stability of ALIBIV, which is 1.5 kcal/mol greater than that observed experimentally, stands out as the largest error in the MIN-FULL calculations. We were unable to crystallize ALIBIV for comparison with the computed structure. However, the predicted choice of rotamers includes the selection of a statistically rare conformation for Ile at position a16 (χ1 = +; χ2 = trans) (26). For calculations modeling an isolated Ile on the surface of a coiled coil, this rare rotamer is predicted to be more favorable (by 0.9 kcal/mol) than the most common Ile rotamer. Interestingly, the relative stability of the best predicted structure that does not contain this rare rotamer agrees very well with experiment (error = 0.6 kcal/mol). It is possible that the stability of the χ1 = +; χ2 = trans rotamer is overestimated by the CHARMM PARAM19 force field.

In conclusion, we consider some differences between protein structure prediction and protein design. In their protein design work, Dahiyat and Mayo have shown a good correlation of predicted stability with experimental melting temperature for variants of the coiled coil GCN4-p1, without using any minimization (37). For the GABH and VBP proteins, however, we find that minimization is essential to good performance. The two results differ because the Dahiyat side-chain identities and conformations were selected to be compatible with the GCN4-p1 backbone structure in the design process. Consequently, the side-chain and backbone geometries are unlikely to be severely strained, and relaxation is expected to be much less important. Many of the amino acid substitutions modeled in this work are not easily accommodated in a fixed-backbone framework, and relaxation is critical. The need to accommodate strain in structure prediction underscores a major difference between prediction and design.

Predicting experimental energy differences to high resolution remains a daunting challenge. Our work on coiled coils demonstrates the importance of including conformational flexibility, here introduced via minimization, in models constructed for this purpose. Future work will have to extend specialized methods for addressing backbone flexibility in coiled coils to other more general protein folds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Burgess and James Pang (Whitehead Institute) for peptide syntheses, Justin Caravella and Ian Chan (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for programming contributions, Leslie Gaffney for help with the manuscript, and Craig Ogata and the staff at beamline X4A at the National Synchrotron Light Source for their assistance. We thank members of the Kim and Tidor labs, especially Justin Caravella, Mona Singh, David Akey, Sam Sia, and John Newman, for scientific input at many levels. This work used the W. M. Keck Foundation X-Ray Crystallography Suite at the Whitehead Institute and was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant GM 44162. A.E.K. was supported by the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation and by a fellowship from the Merck/Massachusetts Institute of Technology collaboration program.

Abbreviations

- VBP

vitellogenin-binding protein

- DEE

Dead End Elimination

- CD

circular dichroism

- Gdm⋅HCl

guanidinium chloride

- Apa

aminopentanoic acid

- MIN-SC

fixed backbone side-chain minimization

- MIN-FULL

full backbone minimization

- GABH

GCN4 Acid/Base Heterodimer

Footnotes

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID codes 1KD8, 1KD9, and 1KDD).

References

- 1.Newman J R, Wolf E, Kim P S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13203–13208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burkhard P, Strelkov S V, Stetefeld J. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:82–88. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01898-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurst H C. Protein Profile. 1995;2:101–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckert D M, Kim P S. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:777–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger B, Wilson D B, Wolf E, Tonchev T, Milla M, Kim P S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8259–8263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf E, Kim P S, Berger B. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1179–1189. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck K, Dixon T W, Engel J, Parry D A. J Mol Biol. 1993;231:311–323. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vinson C R, Hai T, Boyd S M. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1047–1058. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.6.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moll J R, Olive M, Vinson C. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34826–34832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh M, Kim P S. 5th Annual International Conference on Computational Molecular Biology. Montreal: Association for Computing Machinery; 2001. pp. 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harbury P B, Tidor B, Kim P S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8408–8412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harbury P B, Plecs J J, Tidor B, Alber T, Kim P S. Science. 1998;282:1462–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crick F H. Acta Crystallogr. 1953;6:685–689. [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Shea E K, Lumb K J, Kim P S. Curr Biol. 1993;3:658–667. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90063-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edelhoch H. Biochemistry. 1967;6:1948–1954. doi: 10.1021/bi00859a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laue T M, Shah B D, Ridgeway T M, Pelletier S L. Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Science. Cambridge, U.K.: R. Soc. Chem.; 1992. pp. 90–125. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otwinowski Z. In: Data Collection and Processing. Sawer L, Isaacs N, Bailey S, editors. Warrington, U.K.: Science and Engineering Research Council, Daresbury Laboratory; 1993. pp. 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collaborative Computational Project, no. 4. Acta Crysttallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones T A, Zou J W, Cowan S, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunger A T, Adams P D, Clore G M, De L W L, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R W, Jiang J S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu N S, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moitra J, Szilak L, Krylov D, Vinson C. Biochemistry. 1997;36:12567–12573. doi: 10.1021/bi971424h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desmet J, De Maeyer M, Hazes B, Lasters I. Nature (London) 1992;356:539–542. doi: 10.1038/356539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein R F. Biophys J. 1994;66:1335–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80923-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leach A R, Lemon A P. Proteins. 1998;33:227–239. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19981101)33:2<227::aid-prot7>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brooks B R, Bruccoleri R E, Olafson B D, States D J, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. J Comp Chem. 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunbrack R L, Jr, Karplus M. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:543–574. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendes J, Baptista A M, Carrondo M A, Soares C M. Proteins. 1999;37:530–543. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19991201)37:4<530::aid-prot4>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nilsson L, Karplus M. J Comput Chem. 1986;7:591–616. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wesson L, Eisenberg D. Protein Sci. 1992;1:227–235. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560010204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee B, Richards F M. J Mol Biol. 1971;55:379–400. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Neil K T, DeGrado W F. Science. 1990;250:646–651. doi: 10.1126/science.2237415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harbury P B, Zhang T, Kim P S, Alber T. Science. 1993;262:1401–1407. doi: 10.1126/science.8248779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou N E, Kay C M, Hodges R S. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3178–3187. doi: 10.1021/bi00063a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lumb K J, Kim P S. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8642–8648. doi: 10.1021/bi00027a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akey D L, Malashkevich V N, Kim P. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6352–6360. doi: 10.1021/bi002829w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marti D N, Jelesarov I, Bosshard H R. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12804–12818. doi: 10.1021/bi001242e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dahiyat B I, Mayo S L. Protein Sci. 1996;5:895–903. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.