Abstract

Background

Femoral osteotomies have been widely used to treat a wide range of developmental and degenerative hip diseases. For this purpose, different types of proximal femur osteotomies were developed: at the neck as well as at the trochanteric, intertrochanteric, or subtrochanteric levels. Few studies have evaluated the impact of a previous femoral osteotomy on a THA; thus, whether and how a previous femoral osteotomy affects the outcome of THA remains controversial.

Questions/purposes

In this systematic review, we asked: (1) What are the most common complications after THA in patients who have undergone femoral osteotomy, and how frequently do those complications occur? (2) What is the survival of THA after previous femoral osteotomy? (3) Is the timing of hardware removal associated with THA complications and survivorship?

Methods

A systematic review was carried out on PubMed, the Cochrane Systematic Reviews Database, Scopus, and Embase databases with the following keywords: “THA”, “total hip arthroplasty”, and “total hip replacement” combined with at least one of “femoral osteotomy” or “intertrochanteric osteotomy” to achieve the maximum sensitivity of the search strategy. Identified studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) reported data on THAs performed after femoral osteotomy; (2) recorded THA followup; (3) patients who underwent THA after femoral osteotomy constituted either the experimental group or a control group; (4) described the surgical and clinical complications and survivorship of the THA. The database search retrieved 383 studies, on which we performed a primary evaluation. After removing duplicates and completing a full-text evaluation for the inclusion criteria, 15 studies (seven historically controlled, eight case series) were included in the final review. Specific information was retrieved from each study included in the final analysis. The quality of each study was evaluated with the Methodological Index for Non-randomized Studies (MINORS) questionnaire. The mean MINORS score for the historically controlled studies was 14 of 24 (range, 10–17), whereas for the case series, it was 8.1 of 16 (range, 5–10).

Results

The proportion of patients who experienced intraoperative complications during THA ranged from 0% to 17%. The most common intraoperative complication was femoral fracture; other intraoperative complications were difficulties in hardware removal and nerve palsy; 15 studies reported on complications. The survivorship of THA after femoral osteotomy in the 13 studies that answered this question ranged from 43.7% to 100% in studies that had a range of followup from 2 to 20 years. The timing of hardware removal was described in five studies, three of which detailed more complications with hardware removal at the time of THA.

Conclusions

This systematic review demonstrated that THA after femoral osteotomy is technically more demanding and may carry a higher risk of complications than one might expect after straightforward THA. Staged hardware removal may reduce the higher risk of intraoperative fracture and infection, but there is no clear evidence in support of this contention. Although survivorship of THA after femoral osteotomy was generally high, the studies that evaluated it were generally retrospective case series, with substantial biases, including selection bias and transfer bias (loss to followup), and so it is possible that survivorship of THA in the setting of prior femoral osteotomy may be lower than reported.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Both femoral and acetabular osteotomies have been extensively used for the treatment of a wide range of developmental and degenerative hip diseases, such as developmental dysplasia of the hip, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease and even primary and secondary osteoarthritis (OA) [15, 17, 30]. In general, femoral osteotomies seek to restore, or at least improve, hip biomechanics and to increase femoral head coverage and congruency [6]. To achieve the different purposes required, numerous types of osteotomies of the proximal femur have been developed, including osteotomies at the level of the femoral neck as well as at the trochanteric, intertrochanteric, or subtrochanteric levels.

Despite the fact that femoral osteotomies are not performed as frequently as they once were, THA in the setting of a previous femoral osteotomy remains a clinical challenge, and so the topic is worthy of study for several reasons. First, the fact that the number of femoral osteotomies has decreased, we believe this may soon change (especially in adults) in light of newer hip-preserving techniques that have become available as knowledge of the vascularization and pathophysiology of the proximal femur has improved; this may expand what had been the indications for femoral osteotomies [12, 13, 24]. Second, although femoral osteotomies are less common in adults, they still are performed fairly frequently in children and teens. Third, despite several studies reporting durability and good pain relief after femoral osteotomies [2, 7, 9, 10, 20], many patients experience OA progression after the osteotomy. This may result in a large number of patients who received these osteotomies presenting for THA in the years to come, particularly in referral centers where more complex THAs are performed. Few studies have evaluated the impact of a previous femoral osteotomy on a THA [1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 11, 18, 19, 21-23, 25, 27–29], and most of these studies are retrospective case series or historically controlled studies. In this context, clinical decision-making is often based on anecdotal information rather than scientific evidence. Therefore, a systematic review that synthesizes the available information could be helpful to surgeons who treat these patients and to provide references for evidence-based decision-making.

Specifically, in this systematic review, we asked: (1) What are the most common complications after THA in patients who have undergone femoral osteotomy, and how frequently do those complications occur? (2) What is the survival of THA after previous femoral osteotomy? (3) Is the timing of hardware removal associated with THA complications and survivorship?

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Criteria

We carried out a systematic review according to the Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement for Individual Patient Data (PRISMA-IPD) [16]. In May 2018, two of the authors (EG, IM) searched PubMed, the Cochrane Systematic Reviews Database as well as the Scopus and Embase databases using the following keywords: “THA”, “total hip arthroplasty”, and “total hip replacement” combined with at least one of the following: “femoral osteotomy” or “intertrochanteric osteotomy” to achieve maximum sensitivity of the search strategy. Unpublished data and conference proceedings were excluded from this systematic review. The reference lists of all retrieved articles were reviewed for further identification of potentially relevant studies. We hand-screened reference lists of identified studies to find other studies. Each identified study was assessed using the inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine the final list of studies that we analyzed in detail.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

For this review, we defined femoral osteotomy as any proximal femur osteotomy used to treat primary or secondary OA or to correct a congenital or developmental hip deformity. Thus, all types of neck, trochanteric, intertrochanteric, or subtrochanteric osteotomies (varus, valgus, rotational, flection, extension, reposition, or combined) were included.

Original articles written in English were considered for analysis. Identified studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) reported data on THA performed after a previous femoral osteotomy; (2) described THA followup; thus, if a paper reported the followup of femoral osteotomies and stated only the number of conversion to THA, we excluded it from the review; (3) studies in which patients who underwent THA after femoral osteotomy constituted either the experimental group or a control group; (4) detailed surgical and clinical THA complications and survivorship. To include most of the available data, we did not set a limitation concerning the length of followup.

We excluded studies that reported the results of THA combined with femoral osteotomy in the same surgery and not after previous femoral osteotomy as well as narrative reviews, letters, comments, and technical notes. We excluded studies in which patients who underwent THA after a femoral osteotomy constituted a subgroup and from which specific information could not be retrieved. Finally, when more studies described the results on the same patient population, only the most recent was included.

Given the absence of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on this topic, we set no limit concerning the level of evidence: studies with level of evidence from I to IV were allowable. After excluding duplicates, papers were screened for inclusion after abstract review. Disagreements between the two reviewers were solved by discussion after evaluation of the full text of the article.

Search Results

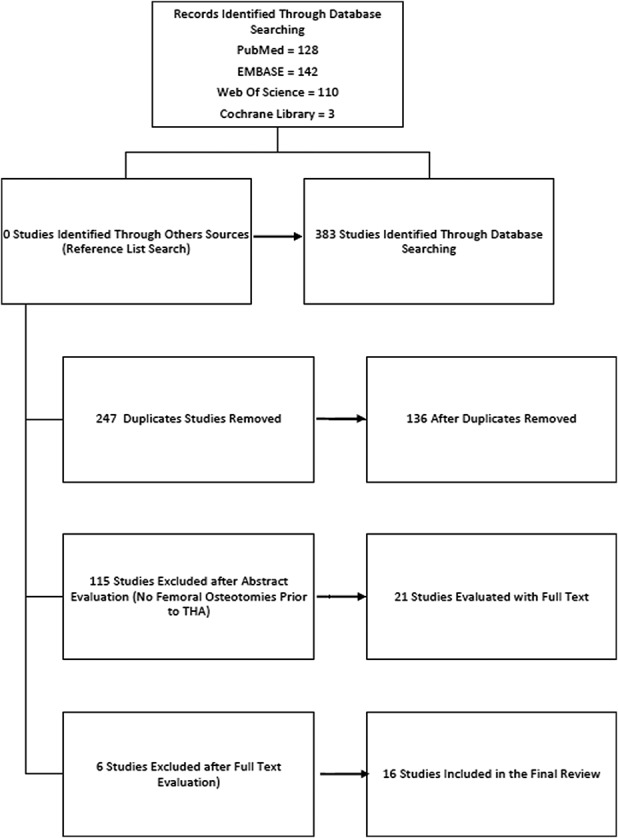

Our database search retrieved 383 studies, which underwent preliminary evaluation (Fig. 1). After removing duplicate studies, 136 original articles were identified, and the abstract of each was reviewed by two authors (EG, IM). After abstract evaluation, 115 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Therefore, we examined 21 full-text studies. After full-text evaluation, another six studies were excluded from the final analysis. In total, 15 studies were included in the final analysis and underwent quality assessment. Overall, mean followup of the included study was 9 years (range, 2-20 years).

Fig. 1.

The flowchart shows the search strategy and the number of identified studies on THA after femoral osteotomies, following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis)guidelines .

Concerning the first research question, all 15 studies had data on intra- and perioperative complications as well as dislocation frequency and the need for further osteotomies during THA. However, no studies directly compared different types of femoral osteotomies in terms of the frequency of complications after THA.

Concerning the second research question, two studies [1, 21], both retrospective case series, did not detail the survivorship of the implants; 13 others did, including one that directly compared the outcomes in cemented versus cementless stems [11].

Concerning the third research question, timing of hardware removal was described in five studies [1, 5, 8, 23, 27], three historically controlled and two case series. Two studies (Nagi et al. [19] and Iwase et al. [11]) reported difficulties with hardware removal without specifying its timing; the other nine studies included in our systematic review could not be used to answer the third research question because they were silent on the issue of timing or difficulties associated with hardware removal.

Assessment of Study Quality

Two reviewers (EG, IM) independently reviewed each included study for quality. The Methodological Index for Non-randomized Studies (MINORS) scoring system for nonrandomized studies was used on each study included in this review [26]. Concerning the adequacy of followup, 1 point was assigned for followup of < 10 years, whereas 2 points were assigned for followup of > 10 years.

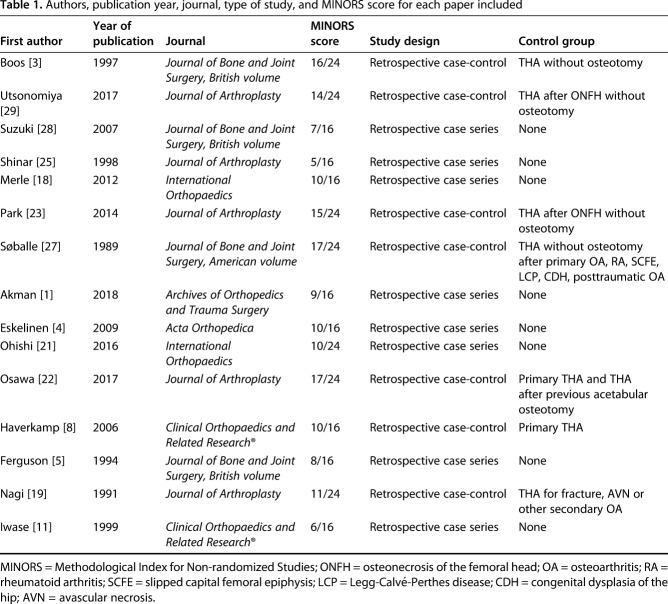

No RCTs or prospective studies were found. We included seven retrospective, historically controlled studies and eight retrospective case series (Table 1). For our first research question, the mean MINORS score for the historically controlled studies was 14 of 24 (range, 10–17), whereas for the case series, it was 8 of 16 (range, 5–10). Among the 13 studies that answered the second research question, the mean MINORS score was 8 for the case series and 15 for the historically controlled studies, whereas for the five studies that answered our third research question, the mean MINORS score was 9 for the case series and 16 for the historically controlled studies.

Table 1.

Authors, publication year, journal, type of study, and MINORS score for each paper included

The most common study quality deficiencies in these studies were the lack of prospective calculation of study size, which was lacking in all the studies included; the inadequacy of the followup was shorter than 10 years in 10 studies and loss of followup of > 5% of patients occurred in five studies.

Data Collection and Outcome Measures

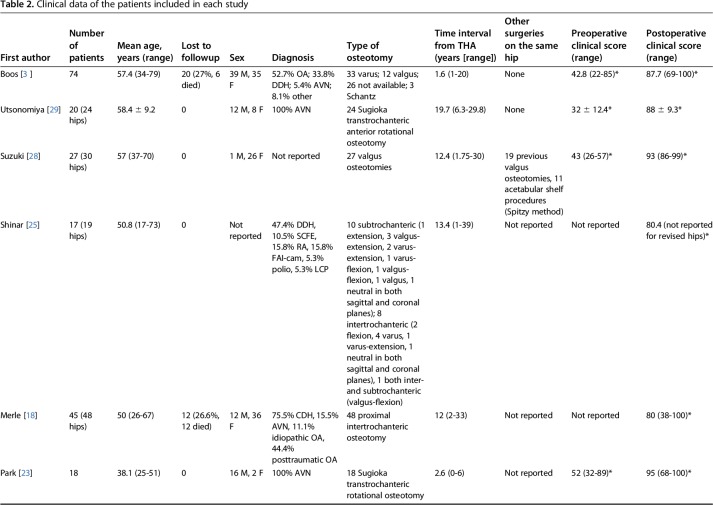

Specific information was retrieved from each study included in the final analysis, such as patient demographics (sex, age), osteotomy indication, osteotomy type, time interval from the THA and other hip procedures, surgical approach, type of stem and cup implanted, and timing of hardware removal (Table 2). Three studies did not report the time interval between the femoral osteotomy and the THA. We evaluated the technical difficulty of the THA by assessing the use of further femoral osteotomies at the time of the arthroplasty and the proportion of intraoperative complications such as femoral fractures or implant malpositioning. For this review, we used the definition of intraoperative complications that each study provided. If a study did not specifically define the intraoperative complications, we considered intraoperative fractures and nerve palsies or nerve lesions as complications. We retrieved long-term survival data from each study when it was available.

Table 2.

Clinical data of the patients included in each study

Results

Complications

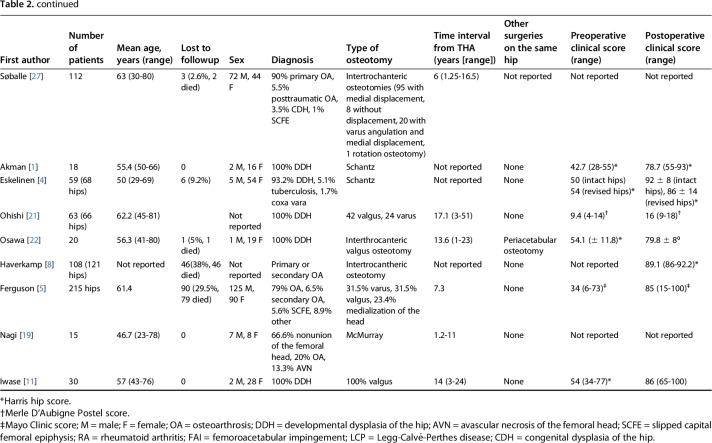

The most common intraoperative complications were femoral fractures, which typically were fixed with either screws or wiring except for two hips reported by Merle et al. [18] and four of five hips in the study by Søballe [27], which were left untreated. Other intraoperative complications were difficulties in hardware removal and nerve palsy: five studies reported the occurrence of nerve palsy, whereas in the other 10 no nerve palsies occurred. All these cases eventually resolved. Timing of palsy resolution was described in only one paper [1], where the patients healed 7 months after surgery. Overall, the proportion of hips with intraoperative complications ranged from 0% to 16.7% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Intra- and perioperative adverse events for each included study

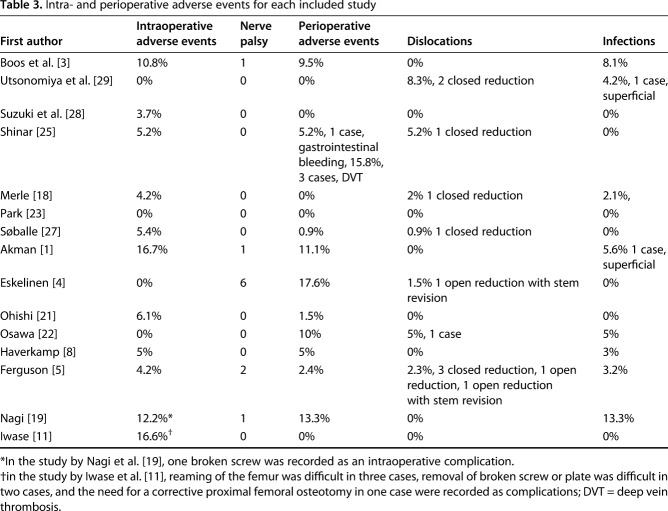

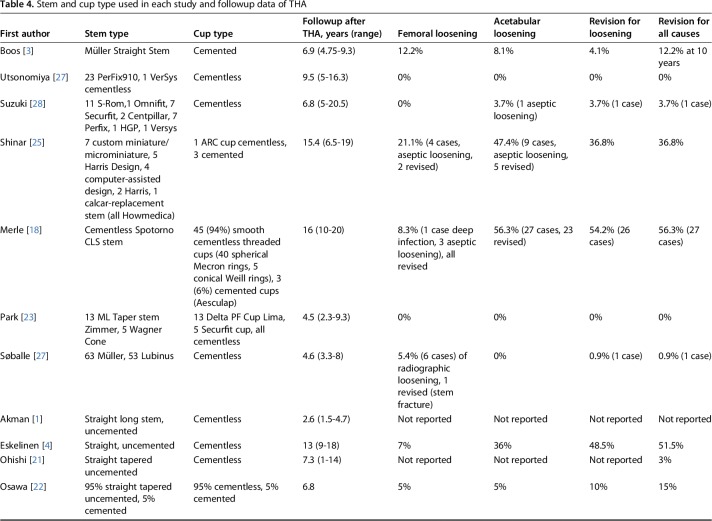

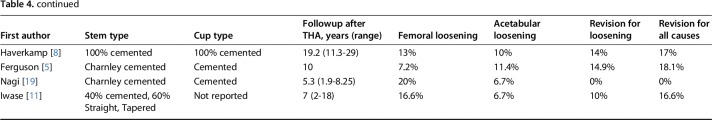

Survival of THA After Previous Femoral Osteotomy

The survivorship of THA after femoral osteotomy in the 13 studies that answered this question ranged from 43.7% to 100% in studies that had a range of followup from 2 to 20 years. A high variability in survival rates can be observed across the studies included (Table 4). In particular, three studies had a very low overall survivorship, mainly as a result of a high proportion of cup loosening [4, 18, 25]. Eskelinen et al. [4] had a 36% cup loosening rate at 13 years followup as a result of the loosening of 16 of 18 threaded cups. Merle at al. [18] described a cup loosening rate of 56.3% at a mean followup of 16 years, and Shinar et al. [25] had a cup loosening rate of 47.4% at a mean followup of 15.4 years. When evaluating stem loosening, it ranged from 0% to 21.1% at a mean followup of 9 years (range, 2–20 years) in the 13 studies that had this outcome. Six studies [19, 21, 23, 27–29] yielded good-to-excellent results (overall survival rate 96.3%–100%) at a midterm followup (mean followup, 6.3 years; range, 4.5–9.8 years). Five studies [4, 5, 8, 18, 25] reported survival at long-term followup (> 10 years); among those, stem survival ranged from 78.9% to 93%.

Table 4.

Stem and cup type used in each study and followup data of THA

Seven studies were designed as historically controlled studies, in which patients who underwent THA after previous femoral osteotomy were compared with a control group of patients who underwent primary THA [3, 8, 19, 22, 23, 27, 29]. Among those, six studies [8, 19, 22, 23, 27, 29] had no differences in survival among the two groups. Boos et al. [3] described a better overall survival rate in the control group (81.9% versus 89.9% at 6.9 years followup); this difference was driven by an increased risk of infection in the osteotomy group (8.1% versus 2.7%).

Timing of Hardware Removal and THA Complications and Survivorship

Haverkamp et al. [8] had no complications with hardware routinely removed 1 to 2 years after the femoral osteotomy. Two studies (Nagi et al. [19] and Iwase et al. [11]) reported difficulties with hardware removal (screw and plate breakage) at the time of THA without specifying the timing of removal. Three historically controlled studies described complications with hardware removal at the time of THA: Ferguson et al. [5] had difficult removal in 24.3% of patients and hardware breakage in 20.7%. Moreover, in 28 (13%) cases of hardware removed before THA, positive intraoperative cultures were found. Søballe et al. [27] reported hardware breakage in 9.4% of patients. Park et al. [23] described an increase in mean operative time (96 minutes versus 88 minutes) and mean blood loss (550 mL versus 450 mL) associated with hardware removal compared with the control group of primary THA. Akman et al. [1] did not report any complications in a subgroup of 11 patients from whom hardware was removed during THA. None of these studies directly recorded an impact on long-term survival based on the timing of hardware removal.

Discussion

Although femoral osteotomies were widely used in the past, improvements in screening and early treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants, together with improved long-term survival and functional outcome of THAs [14], have reduced the frequency with which osteotomies are performed [13]. In the last two decades, new insights about the anatomy (in particular the vascular supply) of the proximal femur and biomechanics (including pathophysiology) of hip OA [12, 24] have renewed interest in hip-sparing procedures. In addition, in parts of the world (including parts of Europe and Japan), femoral osteotomies remain commonly used; some of these patients may subsequently undergo THA, making assessment of this topic worthy of attention. Studies disagree about the efficacy of femoral osteotomy [19, 21, 23, 27–29] with some reporting few complications and good durability, and others raising concerns about poor survivorship and many complications [4, 5, 8, 18, 25]. Therefore, we performed a systematic review and found that complications occur frequently in patients undergoing THA after a femoral osteotomy, the most common of which were femoral fractures and transient nerve palsies. We also learned that although midterm survival of THA seems comparable to the survival of primary THA, long-term survival seems to be worse. Finally, it appears that hardware removal at the time of THA can be difficult and may be associated with plate and screw breakage, longer operating times and higher blood loss, and a possible increase in infection risk. Based on this, we believe that staged removal should be considered.

This study had a number of limitations. First, the absence of RCTs on this topic precludes formal data pooling and meta-analysis. Second, the level of evidence is generally poor as a function of the lack of RCTs and prospective studies, although in fairness, RCTs are unrealistic for such a rare diagnosis. Even so, we urge the reader to recognize that the retrospective study designs available for inclusion here are associated with several important kinds of bias, all of which tend to overestimate the benefits of treatment, minimize the frequency of complications, and provide overly optimistic survival estimates. That being so, we consider the findings here to be best-case analyses, and we caution readers that complications may indeed be more common and survivorship poorer than estimated by the population of studies we evaluated. In addition, although a large number of studies included in this review were conducted > 20 years ago, the reported results on complications and survivorship seemed consistent to us with the more recent studies included, although we conducted no formal analysis on this point. We note that two clinically relevant questions could not be answered in this review because of a lack of evidence: whether the type of osteotomy and the type of stem used influence the mid- and long-term survival of THA. No study was designed to compare the results in case of different types of previous femoral osteotomy; therefore, conclusions cannot be drawn. In general, subtrochanteric osteotomies are associated with more deformities of the proximal femoral canal that may render canal preparation more technically difficult and more at risk of complications. Good results are reported with both cemented [8, 27] and cementless stems [18, 21, 23, 28]. Because only one study directly compared the results of cemented versus conventional cementless stems after failed valgus osteotomy, we could draw no conclusions on this topic [11].

THA after femoral osteotomy is technically demanding. Two historically controlled studies [8, 27] described a higher proportion of femoral fractures in the group that had a previous femoral osteotomy than primary THA. Moreover, longer operating times and a higher proportion of need of trochanteric osteotomies (88% versus 14%) in the osteotomy group were found in historically controlled studies [3, 19]. In the analyzed studies, the proportion of adverse events and complications ranged from 0% [22, 29] to 16.7% [1]. The most common intraoperative complications were the occurrence of intraoperative fracture. The most common postoperative complications were nerve palsies [1, 3-5, 19], perhaps resulting from scar tissue and lengthening. We found similar results regarding dislocation risk: although eight papers had no dislocations, the other seven reported a dislocation proportion of up to 8.3% [29]. In that respect, we believe the potential for major adverse events such as nerve injury and/or dislocations makes THA after osteotomy more like revision THA in terms of the risk of complications. Other papers indicated there was no difference in the number of perioperative complications in series of THA with or without osteotomy [3, 23, 29]. Although from these data no particular type of osteotomy can be linked to an increase in complications, it is interesting to note that two of the studies that reported no intraoperative complications [22, 29] analyzed the Sugioka osteotomy, which is not very commonly used in Western countries. By contrast, the overall distribution of complications across the other studies seemed relatively consistent with two outliers being papers that considered difficulty in broaching as a complication during intertrochanteric valgus osteotomy [12, 19]. We suspect, although there are no direct data on this, that the altered intertrochanteric anatomy after femoral osteotomy is a key cause of intraoperative complications. Finding the true femoral canal can be especially challenging, and struggling to do so can cause fractures or femoral perforation, greater trochanter fractures, and stem malalignment.

Survivorship of THA after femoral osteotomy was described in 13 papers and overall ranged from 43.7% to 100% at a mean followup of 9 years (range, 2-20 years). Three studies [4, 18, 25] had a very low overall survival of the implant as a result of an out-of-proportion risk of loosening for acetabular components; this seems to be an implant design problem rather than anything related to the previous osteotomy. In this context, because the osteotomy alters femoral anatomy, it should have a bigger impact on stem survival; therefore, an analysis of survival of the stem seems important to better understand this issue. Six studies [19, 21, 23, 27-29] reported good-to-excellent results (overall stem survival rate 96.3%-100%) at midterm followup (mean followup, 6.3 years; range, 4.5-9.8 years). Only one study [3] had a low stem survival at midterm followup, but these data were driven mainly by an increase in infection rather than aseptic loosening. On the other hand, in the five studies [4, 5, 8, 18, 25] that described stem survival at long-term followup (> 10 years), the survivorship is poorer, ranging from 78.9% to 93%. Interestingly, the only historically controlled study [8] that compared long-term survival of primary THA versus THA after femoral osteotomy reported no difference, although we speculate that this was a function of insufficient statistical power. We remain concerned that over time, survivorship in THAs after femoral osteotomy may deteriorate, although more research is needed.

Complications associated with hardware removal were common. A particular point of concern regarding the timing of hardware removal was raised by Ferguson et al. [5], who found that 13% of hips developed positive cultures after hardware removal. However, the clinical relevance of this finding is still debatable as only one patient developed an early deep infection. Because of the concern, though, the authors recommended that screws and plates should be routinely removed soon after union of the osteotomy [5]. Indeed, Haverkamp et al. [8] had no complications with hardware removal routinely performed 1 to 2 years after the osteotomy. It should be noted, however, that Akman et al. [1] did not observe an increase in complications in the subgroup of 11 patients from whom hardware was removed at the time of THA [1]. Taken together, these results seem to suggest that staged hardware removal could be advantageous; moreover, conceptually, removal of screws and plates after healing of the osteotomy could be helpful in promoting bone healing in the weak points resulting from screw holes. Healing may reduce the risk of stress risers and fractures around the holes and may prevent extraarticular cement escaping from empty screw holes if a cemented component is used. On this theme, we note that Søballe et al. [27] associated the increase in femoral fractures in the THA after osteotomy group with the presence of weakened cortical bone resulting from screw holes, and Ferguson et al. [5] described a pattern of postoperative periprosthetic fractures and loosening starting from screw holes. On balance, we believe these results support staged removal of hardware, preferably a few years after the osteotomy, as the preferred solution.

In conclusion, we found that THA after femoral osteotomy is technically more demanding and may be associated with a higher risk of complications than primary THA. Staged hardware removal should be considered because it may mitigate the higher risk of intraoperative fracture and infection, but there is no definitive evidence on this point. Midterm survival seems similar to primary THA, but we are concerned about a possible deterioration of survivorship over the longer term. We note that the evidence base on this topic is thin, and given the clinical importance of this issue, we believe it is important that it receive more focused attention in the future. Because even busy referral centers will only treat a few patients with previous femoral osteotomies each year, we suggest that registry studies or multicenter efforts focus on longer term durability of THAs performed in patients who previously have undergone femoral osteotomies. In particular, studies might focus on the most suitable implants for this indication in the hopes of minimizing intra- and postoperative fractures and improving long-term THA survival.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that neither he or she, nor any member of his or her immediate family, has funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the reporting of this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the IRCCS Istituto Ortopedico Galeazzi, Milano, Italy.

References

- 1.Akman YE, Yavuz U, Cetinkaya E, Gur V, Gul M, Demir B. Cementless total hip arthroplasty for severely dislocated hips previously treated with Schanz osteotomy of the proximal femur. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg . 2018;138:427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beer Y, Smorgick Y, Oron A, Mirovsky Y, Weigl D, Agar G, Shitrit R, Copeliovitch L. Long-term results of proximal femoral osteotomy in Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop . 2008;28:819–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boos N, Krushell R, Ganz R, Muller ME. Total hip arthroplasty after previous proximal femoral osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br . 1997;79:247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eskelinen A, Remes V, Ylinen P, Helenius I, Tallroth K, Paavilainen T. Cementless total hip arthroplasty in patients with severely dysplastic hips and a previous Schanz osteotomy of the femur: techniques, pitfalls, and long-term outcome. Acta Orthop . 2009;80:263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferguson GM, Cabanela ME, Ilstrup DM. Total hip arthroplasty after failed intertrochanteric osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br . 1994;76:252–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganz R, Leunig M, Leunig-Ganz K, Harris WH. The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip: an integrated mechanical concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res . 2008;466:264–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grigoris P, Safran M, Brown I, Amstutz HC. Long-term results of transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy for femoral head osteonecrosis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg . 1996;115:127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haverkamp D, de Jong PT, Marti RK. Intertrochanteric osteotomies do not impair long-term outcome of subsequent cemented total hip arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res . 2006;444:154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haverkamp D, Marti RK. Intertrochanteric osteotomy combined with acetabular shelfplasty in young patients with severe deformity of the femoral head and secondary osteoarthritis. A long-term follow-up study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2005;87:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito H, Tanino H, Yamanaka Y, Nakamura T, Takahashi D, Minami A, Matsuno T. Long-term results of conventional varus half-wedge proximal femoral osteotomy for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Br . 2012;94:308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwase T, Hasegawa Y, Iwasada S, Kitamura S, Iwata H. Total hip arthroplasty after failed intertrochanteric valgus osteotomy for advanced osteoarthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res . 1999:175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalhor M, Horowitz K, Gharehdaghi J, Beck M, Ganz R. Anatomic variations in femoral head circulation. Hip Int . 2012;22:307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y-J, Ganz R, Murphy SB, Buly RL, Millis MB. Hip joint-preserving surgery: beyond the classic osteotomy. Instr Course Lect . 2006;55:145–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Learmonth ID, Young C, Rorabeck C. The operation of the century: total hip replacement. Lancet (London, England). 2007;370:1508–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leunig M, Ganz R. The evolution and concepts of joint-preserving surgery of the hip. Bone Joint J . 2014;96–B:5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med . 2009;151:W65-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louahem M’sabah D, Assi C, Cottalorda J. Proximal femoral osteotomies in children. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res . 2013;99:S171-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merle C, Streit MR, Innmann M, Gotterbarm T, Aldinger PR. Long-term results of cementless femoral reconstruction following intertrochanteric osteotomy. Int Orthop . 2012;36:1123–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagi ON, Dhillon MS. Total hip arthroplasty after McMurray’s osteotomy. J Arthroplasty. 1991;(6 Suppl):S17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura M, Matsunaga S, Yoshino S, Ohnishi T, Higo M, Sakou T, Komiya S. Long-term result of combination of open reduction and femoral derotation varus osteotomy with shortening for developmental dislocation of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2004;13:248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohishi M, Nakashima Y, Yamamoto T, Motomura G, Fukushi J-I, Hamai S, Kohno Y, Iwamoto Y. Cementless total hip arthroplasty for patients previously treated with femoral osteotomy for hip dysplasia: the incidence of periprosthetic fracture. Int Orthop . 2016;40:1601–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osawa Y, Hasegawa Y, Okura T, Morita D, Ishiguro N. Total hip arthroplasty after periacetabular and intertrochanteric valgus osteotomy. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:857–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park K-S, Tumin M, Peni I, Yoon T-R. Conversion total hip arthroplasty after previous transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:813–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sculco PK, Lazaro LE, Su EP, Klinger CE, Dyke JP, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. A vessel-preserving surgical hip dislocation through a modified posterior approach: assessment of femoral head vascularity using gadolinium-enhanced MRI. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2016;98:475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinar AA, Harris WH. Cemented total hip arthroplasty following previous femoral osteotomy: an average 16-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:243–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg . 2003;73:712–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Søballe K, Boll KL, Kofod S, Severinsen B, Kristensen SS. Total hip replacement after medial-displacement osteotomy of the proximal part of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 1989;71:692–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki K, Kawachi S, Matsubara M, Morita S, Jinno T, Shinomiya K. Cementless total hip replacement after previous intertrochanteric valgus osteotomy for advanced osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br . 2007;89:1155–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Utsunomiya T, Motomura G, Ikemura S, Hamai S, Fukushi J-I, Nakashima Y. The results of total hip arthroplasty after Sugioka transtrochanteric anterior rotational osteotomy for osteonecrosis. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:2768–2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zweifel J, Honle W, Schuh A. Long-term results of intertrochanteric varus osteotomy for dysplastic osteoarthritis of the hip. Int Orthop . 2011;35:9–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]