Abstract

Background

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a chronic progressive disease of the retinal microvasculature associated with prolonged hyperglycaemia. Proliferative DR (PDR) is a sight‐threatening complication of DR and is characterised by the development of abnormal new vessels in the retina, optic nerve head or anterior segment of the eye. Argon laser photocoagulation has been the gold standard for the treatment of PDR for many years, using regimens evaluated by the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS). Over the years, there have been modifications of the technique and introduction of new laser technologies.

Objectives

To assess the effects of different types of laser, other than argon laser, and different laser protocols, other than those established by the ETDRS, for the treatment of PDR. We compared different wavelengths; power and pulse duration; pattern, number and location of burns versus standard argon laser undertaken as specified by the ETDRS.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) (2017, Issue 5); Ovid MEDLINE; Ovid Embase; LILACS; the ISRCTN registry; ClinicalTrials.gov and the ICTRP. The date of the search was 8 June 2017.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of pan‐retinal photocoagulation (PRP) using standard argon laser for treatment of PDR compared with any other laser modality. We excluded studies of lasers that are not in common use, such as the xenon arc, ruby or Krypton laser.

Data collection and analysis

We followed Cochrane guidelines and graded the certainty of evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We identified 11 studies from Europe (6), the USA (2), the Middle East (1) and Asia (2). Five studies compared different types of laser to argon: Nd:YAG (2 studies) or diode (3 studies). Other studies compared modifications to the standard argon laser PRP technique. The studies were poorly reported and we judged all to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain. The sample size varied from 20 to 270 eyes but the majority included 50 participants or fewer.

Nd:YAG versus argon laser (2 studies): very low‐certainty evidence on vision loss, vision gain, progression and regression of PDR, pain during laser treatment and adverse effects.

Diode versus argon laser (3 studies): very‐low certainty evidence on vision loss, vision gain, progression and regression of PDR and adverse effects; moderate‐certainty evidence that diode laser was more painful (risk ratio (RR) troublesome pain during laser treatment (RR 3.12, 95% CI 2.16 to 4.51; eyes = 202; studies = 3; I2 = 0%).

0.5 second versus 0.1 second exposure (1 study): low‐certainty evidence of lower chance of vision loss with 0.5 second compared with 0.1 second exposure but estimates were imprecise and compatible with no difference or an increased chance of vision loss (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.08 to 2.04, 44 eyes, 1 RCT); low‐certainty evidence that people treated with 0.5 second exposure were more likely to gain vision (RR 2.22, 95% CI 0.68 to 7.28, 44 eyes, 1 RCT) but again the estimates were imprecise . People given 0.5 second exposure were more likely to have regression of PDR compared with 0.1 second laser PRP again with imprecise estimate (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.48, 32 eyes, 1 RCT). There was very low‐certainty evidence on progression of PDR and adverse effects.

'Light intensity' PRP versus classic PRP (1 study): vision loss or gain was not reported but the mean difference in logMAR acuity at 1 year was −0.09 logMAR (95% CI −0.22 to 0.04, 65 eyes, 1 RCT); and low‐certainty evidence that fewer patients had pain during light PRP compared with classic PRP with an imprecise estimate compatible with increased or decreased pain (RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.03 to 1.93, 65 eyes, 1 RCT).

'Mild scatter' (laser pattern limited to 400 to 600 laser burns in one sitting) PRP versus standard 'full' scatter PRP (1 study): very low‐certainty evidence on vision and visual field loss. No information on adverse effects.

'Central' (a more central PRP in addition to mid‐peripheral PRP) versus 'peripheral' standard PRP (1 study): low‐certainty evidence that people treated with central PRP were more likely to lose 15 or more letters of BCVA compared with peripheral laser PRP (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.67 to 13.46, 50 eyes, 1 RCT); and less likely to gain 15 or more letters (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.08) with imprecise estimates compatible with increased or decreased risk.

'Centre sparing' PRP (argon laser distribution limited to 3 disc diameters from the upper temporal and lower margin of the fovea) versus standard 'full scatter' PRP (1 study): low‐certainty evidence that people treated with 'centre sparing' PRP were less likely to lose 15 or more ETDRS letters of BCVA compared with 'full scatter' PRP (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.50, 53 eyes). Low‐certainty evidence of similar risk of regression of PDR between groups (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.27, 53 eyes). Adverse events were not reported.

'Extended targeted' PRP (to include the equator and any capillary non‐perfusion areas between the vascular arcades) versus standard PRP (1 study): low‐certainty evidence that people in the extended group had similar or slightly reduced chance of loss of 15 or more letters of BCVA compared with the standard PRP group (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.28, 270 eyes). Low‐certainty evidence that people in the extended group had a similar or slightly increased chance of regression of PDR compared with the standard PRP group (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.31, 270 eyes). Very low‐certainty information on adverse effects.

Authors' conclusions

Modern laser techniques and modalities have been developed to treat PDR. However there is limited evidence available with respect to the efficacy and safety of alternative laser systems or strategies compared with the standard argon laser as described in ETDRS

Plain language summary

Do newer laser treatments work better than standard laser treatments for proliferative diabetic retinopathy?

What was the aim of this review? The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out if new ways of doing laser treatment for proliferative diabetic retinopathy (explained under 'What was studied in the review?' below) work better than standard treatment. Cochrane researchers collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question and found 11 studies.

Key messages There is limited evidence on the benefits and harms of different laser systems or strategies compared with the standard treatment.

What was studied in the review? People with diabetes can have problems in the back of their eyes that may affect their sight. One of these problems is the growth of harmful new blood vessels in the retina (the layer that covers the back of the eye that allows people to see); this is called proliferative diabetic retinopathy, referred to as ‘PDR’. Sight loss can occur as a result of PDR. Argon laser has been used to treat PDR for many years. New types of laser and new ways of doing laser treatment have been developed to treat PDR. The aim of this review was to assess the evidence for the benefits and harms of these new treatments.

What are the main results of the review? The Cochrane researchers found 11 relevant studies. Four studies were done in Italy, two studies were done in the US, one in South Korea, one in Iran, one in Slovenia, one in Greece and one in India. All the people included in these studies had PDR due to type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Most of these studies were small and provide limited evidence on which to base treatment decisions.

How up to date is this review? Cochrane researchers searched for studies that had been published up to 8 June 2017.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a chronic, progressive, potentially sight‐threatening disease of the retinal microvasculature associated with prolonged hyperglycaemia. As the leading cause of blindness among working‐aged adults around the world, DR is a major public health problem (Klein 2007). Its incidence is rising dramatically along with the incidence of type 2 diabetes, driven by greater longevity combined with sedentary lifestyles and increasing levels of obesity (Geiss 2011). Globally, there are approximately 93 million people with DR, including 17 million with proliferative DR, 21 million with diabetic macular oedema (DMO), and 28 million with vision‐threatening diabetic retinopathy (VTDR) (Yau 2012). A pooled analysis from diabetic population‐based studies around the world found overall prevalence rates of 34.6% for any DR, 6.96% for PDR, 6.81% for DMO and 10.2% for VTDR. All DR prevalence endpoints increased with diabetes duration, haemoglobin A(1c), and blood pressure levels and were higher in people with type 1 compared with type 2 diabetes (Yau 2012). These data highlight the substantial worldwide public health burden of DR and the importance of tackling modifiable risk factors to reduce its occurrence. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) showed that intensive glycaemic control was effective in delaying the onset, as well as slowing the progression, of DR in patients with type 1 diabetes (DCCT Research Group 1993). The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) showed the risk of complications in type 2 diabetics was independently and additively correlated with hyperglycaemia and hypertension, with risk reductions of 21% per 1% decrease in HbA1c and 11% per 10 mmHg decrease in systolic blood pressure (Stratton 2006; UKPDS Group 1998). There are various classifications of DR, but all recognise the two basic mechanisms leading to loss of vision: retinopathy (risk of developing new vessels); and maculopathy (risk of damage to the central fovea). The differences between classifications relate mainly to levels of retinopathy and to terminology used. Severity is ranked into a stepwise scale from no retinopathy through various stages of non‐proliferative or pre‐proliferative disease to advanced proliferative disease (ETDRS Research Group 1991). This review is concerned with Vision Threatening Diabetic Retinopathy (VTDR) related to the development of PDR.

PDR is characterised by the development of new vessels and can be further defined by their location and severity. With regards to location, there may be: new vessels on the disc or within 1 disc diameter (DD) of the margin of the disc (NVD); elsewhere in the retina (NVE); on the iris (NVI); or anterior chamber angle (NVA). Classification of PDR severity includes: early PDR (NVD < 1/4 DD, NVE without haemorrhage); PDR with high risk characteristics such as NVD equal to or greater than 1/4 DD, any NVD‐ or NVE‐associated vitreous haemorrhage; florid (aggressive presentation) PDR; and gliotic (with the development of fibrotic tissue) PDR. 'Involutionary' PDR refers to new vessels that have regressed, usually in response to treatment but (rarely) spontaneously.

Description of the intervention

Laser photocoagulation reduces the oxygen demand of the outer layers of the retina and helps divert adequate oxygen and nutrients to the retina, favourably altering the haemodynamics (Stefánsson 2001). Laser photocoagulation appears also to act by reducing the expression of vasoactive factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and protein kinase C (PKC) in the retina (Ghosh 2005). Indeed, different landmark studies have supported the efficacy of laser PRP in preventing vision loss. The Diabetic Retinopathy Study (DRS) demonstrated that laser photocoagulation of the retina reduced severe visual loss (defined as visual acuity of 5/200 or less on two consecutive visits at least four months apart) (DRS Research Group 1978); and the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) addressed the question of the appropriate time for performing laser photocoagulation, showing that PRP was beneficial only in cases where proliferative changes were present and specifically when high‐risk characteristics PDR were present (ETDRS Research Group 1985). It also showed that focal or grid photocoagulation was beneficial in reducing visual loss due to macular oedema (ETDRS Research Group 1985). As PRP may be associated with morbidity, the risk‒benefit ratio of PRP in people at higher risk would favour the performance of PRP. The visual loss due to PRP is much less debilitating at this stage compared with the high risk of severe vision loss in the near future if the retinopathy were to remain untreated (Feman 2004). The ETDRS also showed that focal or grid photocoagulation was beneficial in reducing the risk of visual loss due to DMO (ETDRS Research Group 1985).

How the intervention might work

It is believed that in the majority of cases, PDR represents an angiogenic response of the retina to extensive capillary closure. New vessels grow at the interface of perfused and non‐perfused retina. Peripheral retinal ischaemia, in the absence of surrogate markers or capillary drop‐out (blot haemorrhage, venous beading, intraretinal microvascular anomalies), may not always be readily discernible clinically, and hence fluorescein angiography — especially wide field fluorescein angiography — is especially useful in detecting ischaemic changes.

The aim of laser PRP treatment is to destroy the areas where there is capillary non‐perfusion and retinal ischaemia as it is in these ischaemic areas where VEGF, a permeability and angiogenic factor, is produced. Lasers act by inducing thermal damage after absorption of energy by tissue pigments. If there is an inadequate response after a standard PRP is undertaken and full regression of new vessels is not achieved, clinicians often supplement the treatment by undertaking further laser in untreated areas.

Following the guidelines published by the DRS and ETDRS, argon laser photocoagulation has been the gold standard for the treatment of PDR. Level 1 evidence from the DRS recommended multisession scatter PRP laser (800 to 1600 spots in one or two sittings, and follow‐up treatment applied as needed at 4‐month intervals) extending to or beyond the vortex vein ampullae (midperipheral retina) (DRS Research Group 1981). Practitioners still widely follow this guideline as a frame of reference. In general, ophthalmologists administer laser covering 360° of the midperipheral retina, with adequate spacing between laser burns (˜ 1 burn apart) to avoid compromising peripheral vision. In clinical practice, the power of the laser selected is set for each individual patient to achieve an adequate burn in the retina and is dependent on variables such as media clarity, fundus pigmentation, and method of delivery. Avoiding very intense white spots is advised to reduce possible complications such as haemorrhage and breaks through Bruch’s membrane which could lead to choroidal neovascularisation.

It has been suggested also that laser strategies other than single pulse argon laser peripheral PRP used by the ETDRS may help reduce ocular side effects, such as laser burn scarring and visual field loss (Muqit 2010). The newer 'yellow' wavelength lasers have the highest combined absorption in the melanin‐oxyhaemoglobin layers of the RPE/choriocapillaris complex and are thought to induce less scatter with increased efficiency compared to green laser photocoagulators (Castillejos‐Rios 1992). Diode laser may produce energy in the 532 nm (green) band, the 577 nm (yellow) band, or in the invisible infrared band (810 nm). These laser treatment strategies can target threshold level, or subthreshold level depending on the power used. MicroPulse mode is available for the 810 nm infrared band wavelength.

Laser PRP can be delivered as a single spot but now multispot laser delivery systems allow a reduced pulse duration compared with conventional argon laser (100 ms to 200 ms) with the aim of a quicker and less painful experience. Additionally, the procedure can be semiautomated by delivering multiple laser burns to the retina with a single depression of the foot pedal.

Why it is important to do this review

Current guidelines for the management of PDR recommend that an ophthalmologist promptly perform PRP until regression of neovascularisation is achieved (Ghanchi 2013). However, most of the evidence relies on the previously described landmark trials, which used older lasers from the 1980s. It does not provide enough evidence to recommend newer laser protocols which may be equally effective but safer and less uncomfortable for patients. Thus a high‐quality review, comparing the standard ETDRS laser treatment for PDR with alternative laser strategies and including modern lasers, was necessary. This systematic review was designed to examine efficacy and safety of alternative types of laser in people with PDR when compared with standard argon laser. It assessed the evidence base for alternative laser treatment strategies such as ischaemia‐targeted laser to the peripheral retina as seen on fluorescein angiography compared with standard argon laser. This review followed on from the preliminary work carried out by Evans 2014 in a recent Cochrane Review assessing the effects of laser photocoagulation for DR compared to no treatment or deferred treatment. PRP has been the mainstay of treatment of PDR for many years, but reviews on variations in the laser treatment protocol were recommended. A NIHR‐HTA project (12/71/01) addressed a similar question but in different populations, with earlier disease than in our review (Royle 2015).

Objectives

To assess the effects of different types of laser, other than argon laser, and different laser protocols, other than those established by the ETDRS, for the treatment of PDR. We compared different wavelengths; power and pulse duration; pattern, number and location of burns versus standard argon laser undertaken as specified by the ETDRS.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in this review.

Types of participants

We included people with type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus of all ages and both sexes with PDR as defined in the included studies. We included a subgroup of trials where participants have received previous pharmacological treatments for diabetic eye disease. We did not exclude studies that enrolled participants with other associated retinal diseases such as retinal vein occlusion as long as the diabetic subgroup with PDR is clearly identified and the reason for laser is PDR.

Types of interventions

We included RCTs that consider laser pan‐retinal photocoagulation (PRP) for PDR but only those with a comparator group of standard argon laser PRP.

Interventions

We compared variations of the following parameters to the standard argon laser single spot treatment (comparator). We excluded studies that considered lasers that are not in common use, such as the xenon arc photocoagulation, ruby or Krypton laser.

Wavelength

Any ophthalmic laser type (wavelength) including but not limited to:

810 nm

577 nm

532 nm

Laser burn application

Any laser burn application method including but not limited to:

variations in total number of burns required to induce regression of neovascularisation, including number of laser sessions required;

use of multispot pattern laser delivery;

use of conventional slit lamp or the fundus camera‐navigated laser system.

Location of laser burns

Any laser burn target location including but not limited to ischaemia‐targeted retinal location.

Laser combined with other treatments

We included studies in which participants may have also received non‐laser based therapies for other indications such as diabetic macular oedema (DMO), for example anti‐VEGF, intraocular steroid implants or traditional Chinese medicine; however, we considered these as a separate subset.

We excluded studies that compare laser versus laser plus another non‐laser intervention for PDR, as this is covered in another Cochrane Review (Martinez‐Zapata 2014)

Comparator

The comparator was standard argon laser single spot treatment according to ETDRS guidelines. Specifically, the recommendations in the ETDRS are an initial treatment of midperipheral scatter laser consisting of 1200 to 1600 burns of moderate intensity, 200 μm to 500 μm spot size, with one‐half spot to one‐spot diameter spacing. Argon pulse duration is 100 ms to 200 ms with power titrated to produce moderate‐intensity burns but with full treatment divided over at least two sessions according to different clinical scenarios (ETDRS Research Group 1987).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was best‐corrected visual acuity (BCVA). Specifically we used the proportion of people who lost or gained at least 15 ETDRS letters (equivalent to 3 ETDRS lines) as measured on a LogMAR chart at the one‐ and five‐year time point.

Secondary outcomes

We considered the following secondary outcomes.

Change in mean BCVA (LogMAR) from baseline to 12 months and five years.

Change in mean best‐corrected near visual acuity (NVA) from baseline to 12 months and five years.

Progression of diabetic retinopathy and/or maculopathy from baseline to 12 months and five years as defined by trial investigators, including optical coherence tomography (OCT) mean central subfield thickness (CMT) where measured.

Visual field (VF) loss from baseline to 12 months and five years compared to baseline including mean deviation (MD).

Patient‐reported outcome measure (PROM) for pain associated with the treatment, vision‐related quality of life (QoL) measured using any validated questionnaire, or loss of driving licence at 12 months and five years.

Resource use and costs.

We recorded two additional outcomes (not planned at the protocol stage).

Regression of diabetic retinopathy.

Need for further laser treatment after 3 months.

The reason we recorded these additional two outcomes is because progression and regression of diabetic retinopathy, and also need for further laser PRP treatment, all represent the same domain, i.e. disease control. This is an important clinical outcome so we wanted to capture all possible data, and several trials do not report progression but report regression or need for further treatment.

Adverse events

Adverse events reported in the studies at any time including but not limited to: macular oedema, retinal detachment, vitreous haemorrhage, need for vitrectomy surgery, severe visual loss (BCVA < 6/60).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials. There were no language or publication year restrictions. The date of the search was 8 June 2017.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 5) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) in the Cochrane Library (searched 8 June 2017) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 8 June 2017) (Appendix 2);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 8 June 2017) (Appendix 3);

ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch; searched 8 June 2017) (Appendix 4);

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 8 June 2017) (Appendix 5);

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp; searched 8 June 2017) (Appendix 6).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of potentially includable studies to identify any additional trials. We did not handsearch conference proceedings for this review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts identified from the electronic and manual searches against the inclusion criteria using web‐based review management software (Covidence 2015). We obtained full‐text copies of all potentially or definitely relevant articles. We contacted trial investigators for further information if required. We resolved discrepancies between authors as to whether or not studies met inclusion criteria by discussion. We documented the excluded studies and the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

We extracted the following participant and trial characteristics and report them in a table format (Appendix 7).

Participant characteristics (age, sex, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), cholesterol, blood pressure, diagnostic criteria used for PDR, baseline visual acuity, OCT‐determined CMT, and areas of ischaemic retinal tissue according to fluorescein angiography).

Intervention (laser agent, laser settings, number of spots delivered, treatment interval and number, retinal target location).

Methodology (group size, randomisation, masking (blinding)).

Outcomes data as specified above.

We contacted trial investigators for key unpublished information that is missing from reports of included studies. Two review authors independently extracted the data, entering data into web‐based review management software (Covidence 2015), and using pre‐piloted data extraction templates. Covidence enabled us to compare discrepancies, which we resolved by discussion. We directly imported data from Covidence into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (Review Manager 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias of the included trials according to Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We considered the following main criteria.

Selection bias: random sequence generation, allocation concealment.

Performance bias: masking of participants, researchers and outcome assessors.

Attrition bias: loss to follow‐up, rates of adherence.

Reporting bias: selective outcome reporting. We reported each parameter as being at high, low, or unclear risk of bias, resolving any discrepancies between the authors by discussion. We contacted study authors to clarify study details relating to any unclear risk of bias. When there was no response from the authors, we classified the trial based on available information.

See Table 9 for additional information on assessment of risk of bias.

1. Risk of bias.

| Item | Low | Unclear | High |

| Sequence generation | Computer generated list, random table, other method of generating random list | Not reported how list was generated. Trial may be described as 'randomised' but with no further details | Alternate allocation, date of birth, records (review authors should exclude these RCTs) |

| Allocation concealment | Central centre (web/telephone access), sealed opaque envelopes | Not reported how allocation administered. Trial may be described as 'randomised' but with no further details | Investigator involved in treatment allocation or treatment allocation clearly not masked |

| Blinding (masking) of participants and personnel | Clearly stated that participants and personnel (apart from doctor) not aware of which lens received | Described as 'double‐masked' with no information on who was masked | No information on masking. As lenses different we will assume that in absence of reporting on this, participants and personnel were not masked |

| Blinding (masking) of outcome assessors | Clearly stated that outcome assessors were masked | Described as 'double‐masked' with no information on who was masked | No information on masking. As lenses different we will assume that in absence of reporting on this, outcome assessors were not masked |

| Incomplete outcome data* | Missing data less than 20% (i.e. more than 80% follow‐up) and equal follow‐up in both groups and no obvious reason why loss to follow‐up should be related to outcome | Follow‐up not reported or missing data > 20% (i.e. follow‐up < 80%) but follow‐up equal in both groups | Follow‐up different in each group and related to outcome |

| Selective outcome reporting | All outcomes in protocol, trials registry entry or both are reported | No access to protocol or trials registry entry | Outcomes in protocol or trials registry entry selectively reported |

We have specified a cut‐point of 20% loss to follow‐up to enable consistent assessment of studies. We considered loss to follow‐up of greater than this to represent a potential risk of attrition bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We measured treatment effect according to the data types described in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011). These include the following.

Dichotomous data

Variables in this group included the primary outcome and the proportion of participants experiencing an adverse event during follow‐up. We reported dichotomous variables as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Continuous data

We reported continuous variables including mean change in visual acuity as mean difference with 95% CIs (if normally distributed) or median and interquartile range (if not normally distributed).

Qualitative data

We reported the types of adverse event, resource use and quality of life data qualitatively as a narrative description of qualitative data.

Unit of analysis issues

Nine of the 10 studies included more than one eye per person. Han 1995 was the only study to include only one eye per person. None of the studies that included one or both eyes adjusted data analysis for within‐person correlation. We used the data as reported by the studies.

Dealing with missing data

We sought key unpublished information that was missing from reports of included studies by contacting study authors but this information was not usually available. We documented when loss to follow‐up was high (over 20%) or imbalanced between treatment groups as potential attrition bias.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity by inspection of the forest plots and by calculating the I² value to assess the proportion of the variance that reflects variation in true effects (Higgins 2003). We considered I² values of greater than 50% to represent substantial inconsistency but also considered the Chi² P value. As this may have low power when there are few studies, we considered P values less than 0.1 to indicate statistical significance of the Chi² test.

Assessment of reporting biases

We were unable to look at reporting biases because there were only 10 studies found and not more than two studies available for each comparison. We considered selective outcome reporting bias as part of the assessment of risk of bias in the individual studies (see Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section).

Data synthesis

Where appropriate, we pooled data using a fixed‐effect model. None of the comparisons and outcomes had more than two trials contributing data.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

We were unable to perform planned subgroup and sensitivity analysis as there was not enough information available. See Differences between protocol and review section for details of planned analyses.

'Summary of findings' table

We reported absolute risks and measures of effect in a 'Summary of findings' (SOF) table providing key information concerning the certainty of the evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all specified review primary and secondary outcomes for a given comparison. Data was not available in suitable format for adverse events, so we provided a narrative summary within the SOF table.

The 'Summary of findings' table included the following key outcomes.

Proportion of people who lose 15 or more ETDRS letters (equivalent to 3 ETDRS lines) as measured on a LogMAR chart from baseline at one and five years.

Proportion of people who gain 15 or more ETDRS letters (equivalent to 3 ETDRS lines) as measured on a LogMAR chart from baseline at one and five years.

Progression of PDR from baseline at one and five years as defined by trial investigators, including OCT mean central subfield thickness (CMT) where measured.

Regression of PDR from baseline at one and five years as defined by trial investigators (new outcome).

Adverse events at any time such as: macular oedema, retinal detachment, vitreous haemorrhage, need for vitrectomy surgery, severe visual loss (BCVA < 6/60).

PROM: significant pain during the laser procedure.

Vision‐related quality of life (QoL) measure using any validated questionnaire at one and five years compared to baseline.

Two review authors independently used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence in the included studies using GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro 2014). We resolved discrepancies by discussion.

We planned to calculate the assumed risk from the median risk in the comparator group of the included studies, but in the event there were not more than two or three studies per comparison so we used the pooled event risk in the comparator group.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

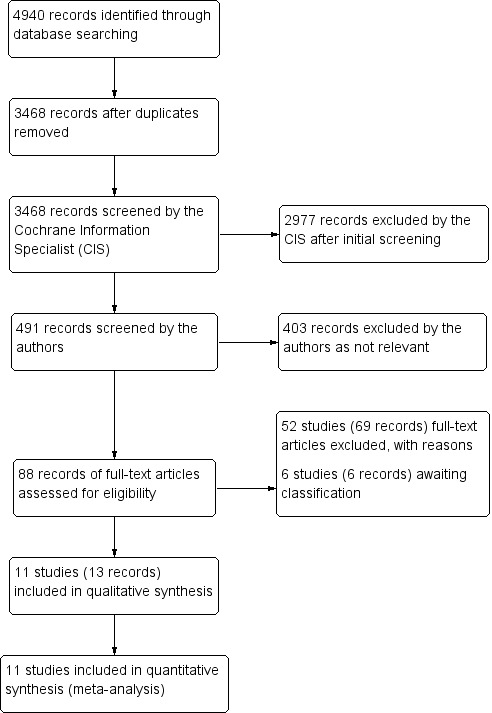

The electronic searches yielded a total of 4940 records (Figure 1). The Cochrane Information Specialist scanned the search results, removed 1472 duplicates and then removed 2977 references which were irrelevant to the scope of the review. We screened the remaining 491 reports and obtained 88 full‐text reports for further assessment. We included 13 reports of 11 studies (see Characteristics of included studies), and excluded 69 reports of 52 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies). We did not identify any ongoing studies from our searches of the clinical trials registries. We have 6 studies awaiting classification for which we were unable to identify a full text report (Chaine 1986, Kianersi 2016; Wroblewski 1991) or were unable to obtain a translation (Uehara 1993, Yang 2010) or for which the full text did not provide enough information to judge inclusion (Salman 2011).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Types of study

We included a total of 11 studies in the review, all of which were randomised controlled trials. These studies were conducted in the US (2), Italy (4), South Korea (1), India (1), Iran (1), Slovenia (1), and Greece (1). There was generally poor recording of the sponsorship source, but two studies declared public funding (Blankenship 1988; Wade 1990.)

Participants

All studies in the review included both male and female adult participants with a clinical diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus, between the ages of 18 to 79 years, although age range of participants was not always reported. One or both eyes of each participant were required to have high risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy based on the ETDRS definition, Han 1995 being the only study to include only one eye per person. None of the studies that included one or both eyes adjusted the data analysis for within‐person correlation. There was one within‐person study (Tewari 2000), again with no appropriate, matched, analysis. Across all included studies the baseline mean age ranged from 40 to 58 years, and baseline mean visual acuity ranged from 0.12 to 0.89 LogMAR acuity. The size of studies varied from 20 to 270 eyes.

Interventions

All participants included in the review were treated with an alternative laser PRP strategy compared with standard argon laser PRP (defined as midperipheral scatter, panretinal photocoagulation with 0.1 second pulse duration of moderate laser intensity). We included a variety of alternative laser PRP interventions which included: double‐frequency Nd:YAG laser (532 nm) (Bandello 1996)(Brancato 1991); diode laser (810 nm) (Bandello 1993; Han 1995; Tewari 2000); longer exposure time of 0.5 second argon laser burn (Wade 1990); 'light intensity' lower energy treatment with standard argon laser pulse (Bandello 2001); 'mild scatter' argon laser pattern limited to only 400 to 600 laser burns in one sitting (Pahor 1998); 'central PRP' which compared a more central (mean number of 437 laser burns placed more posteriorly with sparing of a 2 DD area centred on the fovea and papillomacular bundle) versus a more standard 'peripheral' PRP (mean number of 441 laser burns placed more peripherally, anterior to the equator extending to the ora serrata when possible) treatment in addition to mid‐peripheral PRP (Blankenship 1988); 'central sparing' argon laser PRP distribution which stopped 3 DD from the upper temporal and lower margin of the fovea (Theodossiadis 1990); and an 'extended targeted' argon laser PRP to include the entire retina anterior to the equator and any capillary non‐perfusion areas between the vascular arcades and equator, including 1 DD beyond the ischaemic areas (Nikkhah 2017). See more details in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Outcomes

All studies except two studies (Bandello 1993; Tewari 2000) measured and reported our primary outcome of loss or gain of at least 15 ETDRS letters (equivalent to 3 ETDRS lines) as measured on a LogMAR chart. If the follow‐up was not recorded at the one‐ and five‐year time point we used the final time point provided.

Approximately half of the studies provided some measure of regression or progression of PDR. Visual field loss was only reported in one study and pain during laser treatment was reported in five studies.

No study recorded near visual acuity, or patient‐relevant outcomes such as loss of driving licence or vision‐related quality of life. No study discussed resource use and costs. Follow‐up time ranged from one month to two years.

Excluded studies

Fifty‐two studies were excluded after full text screening. Reasons for exclusion were as follows: intervention, i.e. evaluating a laser that is not currently available (n = 16); comparator, i.e. not compared with standard argon laser PRP (n = 15); study design, i.e. not randomised controlled trial (n = 12); outcome, i.e. study did not measure relevant outcomes (n =3); patient population, i.e. patients did not have PDR (n = 3), comparisons not pre‐specified by this review (n = 3). See Characteristics of excluded studies table for the list of exclusions with reasons.

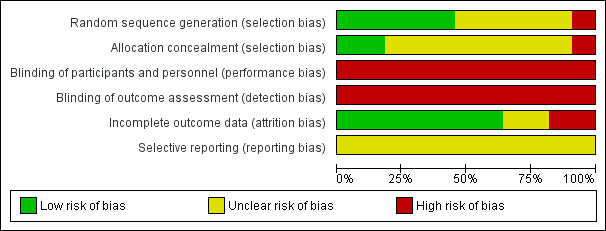

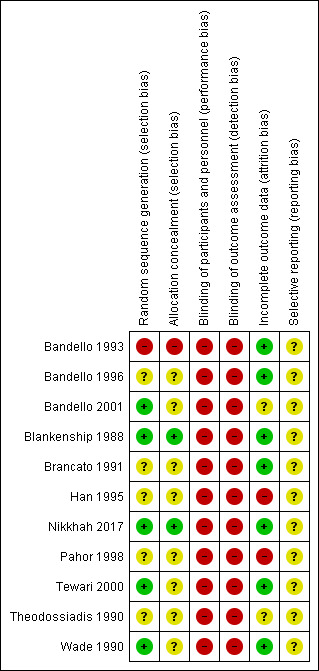

Risk of bias in included studies

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Five studies reported an adequate method of random sequence generation: Bandello 2001 and Nikkhah 2017 used computer‐generated random numbers; Blankenship 1988, Tewari 2000 and Wade 1990 flipped a coin. In the remaining studies it was not possible to judge whether random sequence generation had been done properly. Bandello 1993 may have used alternate allocation.

Two studies reported allocation concealment. In Blankenship 1988 allocation was done after the participants were recruited. Nikkhah 2017 reported that the allocation sequence was kept concealed from the investigators.

Blinding

None of the studies masked participants, personnel or outcomes assessors so they were judged at high risk of bias for these domains.

Incomplete outcome data

Most studies (n = 7) had low risk of attrition bias.

In Han 1995 the number of participants randomised matched the number of participants analysed but the loss to follow‐up was not clearly reported. In Han’s exclusion criteria there was indication that people with adverse events were excluded after treatment but it was not reported how many people were excluded in this way.

In Pahor 1998 attrition was high (38%) after a follow‐up of one month after treatment, and it was not reported to which groups the loss to follow‐up occurred.

In a further two studies, not enough information was given to judge this (Bandello 2001; Theodossiadis 1990).

Selective reporting

We did not have access to trial protocols as the studies were conducted so long ago (Nikkhah 2017 was the only study on a clinical trial registry) so we were unable to judge whether or not selective reporting was likely to be a problem.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Nd:YAG laser compared to argon‐green laser for proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

| Nd:YAG laser compared to argon‐green laser for proliferative diabetic retinopathy | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with proliferative diabetic retinopathy Setting: eye hospital Intervention: Nd:YAG laser Comparison: argon‐green laser | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with argon‐green laser | Risk with Nd:YAG laser | |||||

| BCVA: loss of 15 or more ETDRS letters follow‐up: 1 year | Study population | RR 0.80 (0.30 to 2.13) | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 400 per 1000 (150 to 1000) | |||||

| BCVA: gain of 15 or more ETDRS letters | Study population | RR 0.33 (0.02 to 7.32) | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | ||

| 100 per 1000 | 33 per 1000 (2 to 732) | |||||

| Progression of PDR follow‐up: 1 year | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.07 to 14.95) | 42 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 4 | ||

| 48 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (3 to 712) | |||||

| Regression of PDR follow‐up: 1 year | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.87 to 1.14) | 42 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 5 | ||

| 952 per 1000 | 952 per 1000 (829 to 1000) | |||||

| Pain during laser treatment | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.36 to 2.76) |

62 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 6 | ||

| 190 per 1000 | 190 per 1000 (69 to 524) | |||||

| Vision‐related QoL ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Adverse events | Vitreous haemorrhage, 13% of argon group, RR 1.22 (0.38 to 3.94); choroidal detachment, 19% of argon group, RR 0.23 (0.04 to 1.27); neurotrophic keratopathy, 10% of argon group, RR 1.29 (0.35 to 4.75). | 62 (2 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 7 | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded for risk of bias (−1): high risk of performance and detection bias.

2 Downgraded for imprecision (−1): small study, wide confidence intervals

3Downgraded for indirectness (−1): outcome was loss 2 or more lines of Snellen at 6 months

4 Downgraded for indirectness (−1): outcome was not clearly defined — "PDR worsened" — and was reported at 29 months

5 Downgraded for indirectness (−1): outcome was not clearly defined — "PDR improved" — and was reported at 29 months

6 Downgraded for imprecision (−2): small study, few events

7 Downgraded for inconsistency (−1): there was some inconsistency between studies

Summary of findings 2. Diode laser compared to argon laser for proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

| Diode laser compared to argon laser for proliferative diabetic retinopathy | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with proliferative diabetic retinopathy Setting: eye hospital Intervention: diode laser Comparison: argon laser | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with argon | Risk with Diode | |||||

| BCVA: loss of 15 or more ETDRS letters follow‐up: 1 year | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.66 to 1.36) |

134 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | ||

| 345 per 1000 | 379 per 1000 (231 to 628) | |||||

| BCVA: gain of 15 or more ETDRS letters follow‐up: 1 year | Study population | RR 0.60 (0.25 to 1.45) |

134 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | ||

| 190 per 1000 | 119 per 1000 (47 to 302) | |||||

| Progression of PDR follow‐up: 1 year | Study population | RR 0.90 (0.41 to 2.00) |

66 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 4 | ||

| 286 per 1000 | 257 per 1000 (117 to 571) | |||||

| Regression of PDR follow‐up: 1 year | Study population | RR 0.75 (0.35 to 1.60) | 66 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 4 | ||

| 343 per 1000 | 257 per 1000 (120 to 549) | |||||

| Pain during laser treatment | 211 per 1000 | 688 per 1000 (428 to 1000) |

RR 3.07 (2.15 to 4.39) | 228 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Vision‐related QoL ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Adverse events | Vitreous haemorrhage, 15% of argon group. inconsistent results between two studies, RR 0.50 (0.05, 4.86) and RR 1.82 (0.76, 4.35); choroidal detachment, 8% of argon group RR 4.00 (0.51, 31.13; neurotrophic keratopathy, 0% of argon group, RR 3.00 (0.13, 67.51), maculopathy, 14% of argon group, RR 1.30 (0.54, 3.13), cataract, 16% of argon group, RR 0.52 (0.17, 1.57), pre‐retinal membrane, 5% of argon group, RR 1.16 (0.24, 5.49). | 134 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 5 | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded for risk of bias (−1): high risk of performance, detection and attrition bias

2 Downgraded for indirectness (−1): outcome was not clearly defined — "worsened" visual acuity and "improved" visual acuity

3 Downgraded for imprecision (−1): wide confidence interval

4 Downgraded for indirectness (−1): outcome was not clearly defined — "worsened" or "improved" neovascularisation

5 Downgraded for imprecision (−2): very wide confidence interval

Summary of findings 3. 0.5 compared to 0.1 second exposure for proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

| 0.5 compared to 0.1 second exposure for proliferative diabetic retinopathy | ||||||

| Patient or population: proliferative diabetic retinopathy Setting: eye hospital Intervention: 0.5 second exposure Comparison: 0.1 second exposure | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with 0.1 second exposure | Risk with 0.5 second exposure | |||||

| BCVA: loss of 15 or more EDTRS letters ‐ 1 year | Study population | RR 0.42 (0.08 to 2.04 |

44 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 200 per 1000 | 84 per 1000 (16 to 408) | |||||

| BCVA: gain of 15 or more EDTRS letters ‐ 1 year | Study population | RR 2.22 (0.68 to 7.28) |

44 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 150 per 1000 | 333 per 1000 (102 to 1000) | |||||

| Progression of PDR ‐ 1 year | Study population | RR 0.33 (0.02 to 7.14) |

16 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 | ||

| 125 per 1000 | 41 per 1000 (3 to 893) | |||||

| Regression of PDR ‐ 1 year | Study population | RR 1.17 (0.92 to 1.48) | 32 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 857 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (789 to 1000) | |||||

| Pain during laser treatment ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Adverse events | Pre‐retinal or vitreous haemorrhage, 30% of 0.1 sec group, (RR 0.56 (0.18 to 1.70)); macular thickening, 2 cases in 0.1 sec group; combined rhegmatous and traction retinal detachment, 1 case in 0.5 sec group. | ‐ | 44 (1 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded for risk of bias (−1): high risk of performance and detection bias

2 Downgraded for Imprecision (−1): wide confidence interval

3Downgraded for Imprecision (−2): small study, very wide confidence interval

Summary of findings 4. Light PRP compared to classic PRP for proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

| Light PRP compared to classic PRP for proliferative diabetic retinopathy | ||||||

| Patient or population: proliferative diabetic retinopathy Setting: eye hospital Intervention: light PRP Comparison: classic PRP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with classic | Risk with Light | |||||

| BCVA: loss of 15 letters or more ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Mean difference in logMAR acuity at 1 year was −0.09, 95% CI −0.22 to 0.04; participants = 65; studies = 1. |

| BCVA: gain of 15 letters or more ‐ not reported | ||||||

| Progression of DR ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Regression of PDR ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Pain during laser treatment | Study population | RR 0.23 (0.03 to 1.93) | 65 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 129 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (4 to 249) | |||||

| Adverse events | Vitreous haemorrhage, 19% in classic group, RR 0.07 (0.00 to 1.20); choroidal detachment 3 cases in classic group; neurotrophic keratopathy, 2 cases in classic group; clinically significant macular oedema, 23% of classic group, RR 0.13 (0.02 to 1.00). | ‐ | 65 (1 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded for imprecision (−1): wide confidence interval

2 Downgraded for risk of bias (−1): high risk of performance and detection bias

3 Downgraded for imprecision (−2): few number of events

Summary of findings 5. Mild scatter PRP compared to full scatter PRP for proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

| Mild scatter PRP compared to full scatter PRP for proliferative diabetic retinopathy | ||||||

| Patient or population: proliferative diabetic retinopathy Setting: eye hospital Intervention: mild scatter PRP Comparison: full scatter PRP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Full scatter PRP | Risk with Mild scatter PRP | |||||

| BCVA: loss of 15 or more ETDRS letters ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Mean Snellen decimal acuity was similar in the two groups at 3 months. Mild scatter 0.93 (SD 0.11), full scatter 0.89 (SD 0.19). |

| BCVA: gain of 15 or more ETDRS letters ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Progression if PDR ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Regression of PDR ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Pain during laser treatment ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Vision‐related QoL ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Adverse events ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

Summary of findings 6. Central PRP compared to peripheral PRP for proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

| Central compared to peripheral for proliferative diabetic retinopathy | ||||||

| Patient or population: proliferative diabetic retinopathy Setting: eye hospital Intervention: central Comparison: peripheral | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with peripheral | Risk with Central | |||||

| BCVA: loss of 15 or more ETDRS letters ‐ 1 year | Study population | RR 3.00 (0.67 to 13.46) | 50 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 80 per 1000 | 240 per 1000 (54 to 1000) | |||||

| BCVA: gain of 15 or more ETDRS letters ‐ 1 year | Study population | RR 0.25 (0.03 to 2.08) | 50 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 160 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (5 to 333) | |||||

| Progression of DR ‐ not reported | ‐ | |||||

| Regression of PDR ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Pain during laser treatment ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Vision‐related QoL ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Adverse events | Vitreous haemorrhage requiring additional PRP, 1 case in each group; macular traction detachment requiring pars plana vitrectomy, 3 cases in central group, 1 case in peripheral group; macular thickening associated with loss of 2 or more lines of visual acuity, 2 cases in each group. | ‐ | 50 (1 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Dowgraded for risk of bias (−1): high risk of performance and detection bias

2 Downgraded for imprecision (−1): wide confidence interval

3 Downgraded for imprecision (−2): few number of events

Summary of findings 7. Centre sparing PRP compared to full scatter PRP for proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

| Centre sparing PRP compared to full scatter PRP for proliferative diabetic retinopathy | ||||||

| Patient or population: proliferative diabetic retinopathy Setting: eye hospital Intervention: centre sparing PRP Comparison: full scatter PRP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with full scatter PRP | Risk with Centre sparing | |||||

| BCVA: loss of 15 or more ETDRS letters follow‐up: 1 year | Study population | RR 0.67 (0.30 to 1.50) | 53 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 385 per 1000 | 258 per 1000 (115 to 577) | |||||

| BCVA: gain of 15 or more ETDRS letters follow‐up: 1 year ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Progression of DR ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Regression of PDR follow up: 1 year | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.73 to 1.27) | 53 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 808 per 1000 | 775 per 1000 (590 to 1000) | |||||

| Pain during laser treatment ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Vision‐related QoL ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Adverse events ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded for risk of bias (−1): high risk of performance and detection bias

2 Downgraded for imprecision (−1): wide confidence intervals

Summary of findings 8. Extended targeted PRP compared to standard PRP.

| Extended targeted PRP compared with standard PRP for proliferative diabetic retinopathy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with diabetic retinopathy Settings: eye hospital Intervention: extended targeted PRP Comparison: standard PRP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| standard PRP | extended targeted PRP | |||||

| BCVA: loss of 15 or more ETDRS letters: follow‐up 1 year | Study population | RR 0.94 (0.70 to 1.28) |

270 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1 2 | Mean difference in BCVA at 1 year was: 0.00 logMAR, (−0.05 to 0.05) | |

| 393 per 1000 | 369 per 1000 (275 to 503) | |||||

| BCVA: gain of 15 or more ETDRS letters: follow‐up 1 year, not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Progression of DR ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Regression of PDR follow‐up 1 year |

Study population | RR 1.11 (0.95 to 1.31) |

270 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1 2 | ||

| 644 per 1000 | 715 per 1000 (612 to 844) | |||||

| Pain during laser treatment ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Vision‐related QoL ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Adverse events | Quote: "None of the eyes developed tractional retinal detachment during the study. Additionally, no ocular or non‐ocular AEs related to the study intervention were detected by the investigators or reported by patients" | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3 | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; AE: adverse events | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded for risk of bias (−1): high risk of performance and detection bias

2 Downgraded for imprecision (−1): wide confidence intervals

3 Downgraded for imprecision (−3): study was underpowered to detect rare adverse effects.

Nd:YAG (532 nm) laser PRP versus argon (514 nm) laser PRP

Two studies investigated this comparison (Bandello 1996; Brancato 1991). Bandello 1996 enrolled 42 eyes (33 participants) with PDR and followed up for 29 months. Brancato 1991 enrolled 20 eyes with PDR (16 people with NVD/NVE > 1/2 DA or associated with haemorrhage) and followed up for 6 months.

There was very low‐certainty evidence for all outcomes (Table 1).

People treated with Nd:YAG laser PRP were less likely to lose 15 or more letters of BCVA compared with argon laser PRP (risk ratio (RR) 0.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.30 to 2.13; participants = 20; studies = 1) (Analysis 1.1).

People treated with Nd:YAG laser PRP were less likely to gain 15 or more letters BCVA compared with argon laser (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.02 to 7.32; participants = 20; studies = 1; I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.2).

Both studies reported change in BCVA as decimal Snellen acuity which meant that it was not possible to provide a pooled analysis. There was little evidence of any important difference between the two groups (Analysis 1.3).

There was a similar risk of progression and regression of PDR in the two groups (RR progression 1.00, 95% CI 0.07 to 14.95 (Analysis 1.4); and RR regression 1.00, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.14 (Analysis 1.5) respectively).

Similar proportions of people reported pain during laser treatment (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.36 to 2.76; participants = 62; studies = 2) (Analysis 1.6).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nd:YAG laser vs argon laser, Outcome 1 BCVA: loss of 15 or more ETDRS letters.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nd:YAG laser vs argon laser, Outcome 2 BCVA: gain of 15 or more ETDRS letters.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nd:YAG laser vs argon laser, Outcome 3 Change in BCVA.

| Change in BCVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Nd: YAG: mean decimal Snellen acuity at follow‐up (SD) | N | Argon: mean decimal Snellen acuity at follow‐up (SD) | N |

| Bandello 1996 | 0.5 (0.25) | 21 | 0.45 (0.27) | 21 |

| Brancato 1991 | 0.5 (0.25) | 10 | 0.5 (0.25) | 10 |

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nd:YAG laser vs argon laser, Outcome 4 Progression of PDR.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nd:YAG laser vs argon laser, Outcome 5 Regression of PDR.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nd:YAG laser vs argon laser, Outcome 6 Pain during laser treatment.

Other relevant outcomes such as NVA, VF loss, vision‐related QoL measure, details of any resource use and costs and need for further laser PRP treatment after three months were not reported.

Adverse events are set out in the following table. There were inconsistent results for vitreous haemorrhage and neurotrophic keratopathy. Choroidal detachment occurred less frequently in the YAG laser group but the estimates were imprecise and did not exclude no difference.

| Adverse event | Study | Nd:YAG n/N (%) |

Argon n/N (%) |

RR (95% CI) | Pooled RR (95% CI) |

| Vitreous haemorrhage | Bandello 1996 | 5/21 (24%) | 2/21 (10%) | 2.50 (0.54, 11.48) | 1.22 (0.38 to 3.94) I² = 57%) |

| Brancato 1991 | 0/10 (0%) | 2/10 (20%) | 0.20 (0.01, 3.70) | ||

| Choroidal detachment | Bandello 1996 | 1/21 (5%) | 5/21(24%) | 0.20 (0.03, 1.57) | 0.23 (0.04 to 1.27) I² = 0%) |

| Brancato 1991 | 0/10 (0%) | 1/10 (10%) | 0.33 (0.02, 7.32) | ||

| Neurotrophic keratopathy | Bandello 1996 | 3/21 (14%) | 3/21 (14%) | 1.00 (0.23, 4.40) | 1.29 (0.35 to 4.75) I² = 0%) |

| Brancato 1991 | 1/10 (10%) | 0/10 (0%) | 3.00 (0.14, 65.90) |

We graded the evidence for this comparison as very low‐certainty for all outcomes (Table 1). We downgraded 1 level for high risk of performance and detection bias as the studies were not masked; 1 level for imprecision as the studies were small and estimates of effect imprecise; and 1 level for indirectness as the outcomes were not reported at our pre‐specified time points and were not clearly defined.

Diode (810 nm) versus argon (514 nm) laser PRP

Three studies investigated this comparison (Bandello 1993; Han 1995; Tewari 2000). Han 1995 enrolled 108 eyes (108 people) with PDR and followed up for between 13 to 15 months. Bandello 1993 enrolled 34 people (44 eyes) with PDR and followed up for 2 years (on average). Tewari 2000 was a within‐person study of 22 people (44 eyes) with follow‐up of 6 months.

There was very low‐certainty evidence for the following outcomes (Table 2).

People treated with diode laser PRP had similar or slightly increased risk of "worsened" vision compared with argon green laser PRP (1.10, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.82; eyes = 108; studies = 1) (Analysis 2.1).

People treated with diode laser PRP were less likely to have "improved" vision compared with argon laser PRP (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.59; eyes = 108; studies = 1) (Analysis 2.2).

Mean Snellen acuity was similar in both groups (Analysis 2.3).

People treated with diode laser PRP had a similar or slightly lower risk of progression of PDR compared with argon laser PRP (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.41 to 2.00) (Analysis 2.4).

People treated with diode laser PRP were less likely to have regression of PDR compared with argon laser PRP (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.60) (Analysis 2.5).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Diode versus argon laser, Outcome 1 BCVA: loss of 15 or more ETDRS letters.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Diode versus argon laser, Outcome 2 BCVA: gain of 15 or more ETDRS letters.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Diode versus argon laser, Outcome 3 Change in BCVA.

| Change in BCVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Follow‐up | Diode: mean Snellen decimal acuity at follow‐up (SD) | N | Argon: mean Snellen decimal acuity at follow‐up (SD) | N |

| Bandello 1993 | Average of approximately 2 years (24 months) | 0.4 (0.3) | 22 | 0.4 (0.3) | 22 |

| Tewari 2000 | 6 months | 3,62 (2.12) reciprocal of Snellen decimal acuity | 25 | 4.76 (2.83) reciprocal of Snellen decimal acuity | 25 |

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Diode versus argon laser, Outcome 4 Progression of PDR.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Diode versus argon laser, Outcome 5 Regression of PDR.

There was moderate‐certainty evidence that diode laser was more painful (RR 3.12, 95% CI 2.16 to 4.51; participants = 202; studies = 3; I2 = 0%) Analysis 2.6.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Diode versus argon laser, Outcome 6 Pain during laser treatment.

In the Han 1995 paper only the number of people (%) with "improved", "unchanged" or "worsened" visual acuity were provided; but there is no numerical definition for each of these and it was unclear which charts were used for visual acuity measurement.

Other relevant outcomes such as NVA, VF loss, pain during laser treatment, vision‐related QoL measure, details of any resource use and costs, and need for further laser PRP treatment after three months were not reported.

Adverse events are summarised in the following table and Analysis 2.7.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Diode versus argon laser, Outcome 7 Adverse effects.

| Adverse event | Study | Diode n/N (%) |

Argon n/N (%) |

RR (95% CI) | Pooled RR (95% CI) |

| Vitreous haemorrhage | Bandello 1993 | 7/22 (32%) | 4/22 (18%) | 1.75 [0.60, 5.14] | 1.80 (0.91 to 3.53) |

| Han 1995 | 11/50 (22%) | 7/58 (12%) | 1.82 (0.76, 4.35) | ||

| Tewari 2000 | NR | NR | |||

| Choroidal detachment | Bandello 1993 | 4/22 (18%) | 1/22 (5%) | 4.00 [0.48, 33.00] | NA |

| Han 1995 | NR | NR | |||

| Tewari 2000 | NR | NR | |||

| Neurotrophic keratopathy | Bandello 1993 | 1/22 (5%) | 0/22 (0%) | 3.00 [0.13, 69.87] | NA |

| Han 1995 | NR | NR | |||

| Tewari 2000 | NR | NR | |||

| Maculopathy | Bandello 1993 | NR | NR | NA | |

| Brancato 1990 | NR | NR | |||

| Han 1995 | 9/50 (18%) | 8/58 (14%) | 1.30 (0.54, 3.13) | ||

| Tewari 2000 | NR | NR | |||

| Cataract | Bandello 1993 | NR | NR | NA | |

| Brancato 1990 | NR | NR | |||

| Han 1995 | 4/50 (8%) | 9/58 (16%) | 0.52 (0.17, 1.57) | ||

| Tewari 2000 | NR | NR | |||

| Pre‐retinal membrane | Bandello 1993 | NR | NR | NA | |

| Brancato 1990 | NR | NR | |||

| Han 1995 | 3/50 (6%) | 3/58 (5%) | 1.16 (0.24, 5.49) | ||

| Tewari 2000 | NR | NR |

NR = not reported; NA = not applicable.

We graded the evidence for this comparison as very low‐certainty for all outcomes (apart from pain) (Table 2). We downgraded all outcomes recorded in the studies by 1 level for high risk of performance and detection bias as it was unclear if the studies were masked and no details of randomisation were provided; and 1 level for imprecision due to wide confidence interval. The outcomes of BCVA and DR progression/regression were also downgraded by 1 level for indirectness as the outcomes were not clearly defined (both studies only stated "worsened" visual acuity, "worsened" or "improved" neovascularisation).

0.5‐second versus 0.1‐second duration of exposure of argon (514 nm) laser PRP

One study investigated this comparison (Wade 1990). Wade 1990 enrolled 50 eyes (41 participants) with high‐risk PDR (DRS Research Group 1978 criteria) and followed up for 6 months.

Low‐certainty and very low‐certainty evidence was available (Table 3).

Low‐certainty evidence that people treated with 0.5‐second laser PRP were less likely to have a loss of 15 or more letters of BVCA compared with 0.1‐second laser PRP. (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.08 to 2.04) (Analysis 3.1).

Low‐certainty evidence that people treated with 0.5‐second laser PRP were more likely to have a gain of 15 or more letters of BVCA compared with 0.1‐second laser PRP (RR 2.22, 95% CI 0.68 to 7.28) (Analysis 3.2).

Very low‐certainty evidence of progression of PDR between the 0.5‐second group compared with standard 0.1‐second laser spot duration (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.02 to 7.14) (Analysis 3.3).

Low‐certainty evidence that people treated with 0.5‐second laser PRP were less likely to have regression of PDR compared with 0.1‐second laser PRP (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.48) (Analysis 3.4).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 0.5 versus 0.1 second exposure, Outcome 1 BCVA: loss of 15 or more EDTRS letters.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 0.5 versus 0.1 second exposure, Outcome 2 BCVA: gain of 15 or more EDTRS letters.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 0.5 versus 0.1 second exposure, Outcome 3 Progression of PDR.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 0.5 versus 0.1 second exposure, Outcome 4 Regression of PDR.

Other relevant outcomes such as NVA, VF loss, pain during laser treatment, vision‐related QoL measure, details of any resource use and costs were not reported.

Adverse events are summarised in the following table.

| Adverse event | 0.5 sec n/N (%) |

0.1 sec n/N (%) |

RR (95% CI) |

| Pre‐retinal or vitreous haemorrhage | 4/24 (17%) | 6/20 (30%) | 0.56 (0.18 to 1.70) |

| Macular thickening | 0/24 (0%) | 2/20 (10%) | 0.17 (0.01 to 3.31) |

| Combined rhegmatous and traction retinal detachment requiring pars plana vitrectomy | 1/24 (4%) | 0/20 (0%) | 2.52 (0.11 to 58.67) |

We graded the evidence for this comparison as low‐certainty for the outcomes of 'BCVA: loss of 15 or more ETDR letters' and 'regression of PDR' Table 3. We downgraded 1 level for high risk of imprecision due to wide confidence intervals, and downgraded 1 level for high risk of performance and detection bias. For the outcome of 'Progression of PDR' we downgraded an additional 1 level due to the very wide confidence interval.

'Light laser' intensity PRP versus 'classic' argon (514 nm) laser PRP

One study investigated this comparison (Bandello 2001). Bandello 2001 enrolled 65 eyes (50 people) with high‐risk PDR (DRS Research Group 1978 criteria) and followed up for an average of 22 months. Treatment included 'light intensity' lower energy argon laser PRP treatment to achieve a very light grey biomicroscopic effect on the retina versus 'classic' argon laser PRP to achieve an opaque, dusky, grey‐white, off‐white standard burn.

There was no difference in the change in BCVA between the light laser PRP and the classic laser PRP group (MD −0.09, 95% CI −0.22 to 0.04) (Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Light versus classic, Outcome 1 Change in BCVA.

There was low‐certainty evidence that fewer people had pain during laser treatment in the light laser PRP compared with classic laser PRP group (RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.03 to 1.93) (Analysis 4.2) (Table 4).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Light versus classic, Outcome 2 Pain during laser treatment.

Other relevant outcomes such as BCVA loss or gain of 15 or more letters, NVA, VF loss, vision‐related QoL measure, details of any resource use and costs and need for further laser PRP treatment after 3 months were not reported.

| Adverse event | Light n/N (%) |

Classic n/N (%) |

RR (95% CI) |

| Vitreous haemorrhage | 0/34 (0%) | 6/31 (19%) | 0.07 (0.00 to 1.20) |

| Choroidal detachment | 0/34 (0%) | 3/31 (10%) | 0.13, (0.01 to 2.43) |

| Neurotrophic keratopathy | 0/34 (0%) | 2/31 (6%) | 0.18 (0.01 to 3.67) |

| Clinically significant macular oedema | 1/34 (3%) | 7/31 ( 23%) | 0.13 (0.02 to 1.00) |

We graded the evidence for this comparison as low‐certainty for the outcomes of 'pain during laser treatment' (Table 4). We downgraded 1 level for high risk of imprecision due to wide confidence intervals, and downgraded 1 level for high risk of performance and detection bias.

'Mild scatter' versus 'full scatter' argon (514 nm) laser PRP

One study investigated this comparison (Pahor 1998). Pahor 1998 enrolled 40 eyes (32 people) with early PDR and followed up for one month. Treatment included 'mild scatter' argon laser PRP with pattern limited to 400 to 600 laser burns (500 μm, 0.1 sec) over one session versus 'full scatter' argon laser PRP with 1200 to 1600 laser burns (500 μm, 0.1 sec) over two sessions, two weeks apart.

Results are as follows.

There was no difference in the change in BCVA between the 'full scatter' PRP compared with the 'mild scatter' PRP group (MD 0.04, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.14) (Analysis 5.1).

Very low‐certainty evidence that people treated with 'full scatter' PRP were more likely to have visual field loss compared with the 'mild scatter' PRP group (MD −2.50, 95% CI −4.22 to −0.78) (Analysis 5.2) (Table 5).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Mild scatter PRP vs full scatter PRP, Outcome 1 Change in BCVA.

| Change in BCVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Mild scatter: mean Snellen decimal acuity (SD) | N | Full scatter: mean Snellen decimal acuity (SD) | N |

| Pahor 1998 | 0.93 (0.11) | 19 | 0.89 (0.19) | 21 |

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Mild scatter PRP vs full scatter PRP, Outcome 2 Visual field (mean deviation).

Other relevant outcomes such as BCVA loss or gain of 15 or more letters, NVA, progression or regression of DR, pain during laser treatment, vision‐related QoL measure, details of any resource use and costs and need for further laser PRP treatment after three months were not reported.

The authors made no comment regarding adverse events in this study.

We graded the evidence for this comparison as low‐certainty for the outcomes of 'Visual field loss at 1‐year follow‐up' Table 5. We downgraded 1 level for high risk of imprecision due to small study size and upper confidence interval close to 0 (null effect); and downgraded 1 level for high risk of performance, detection and attrition bias.

'Central' PRP versus 'peripheral' argon (514 nm) laser PRP