Abstract

Background

The combination of steroid and anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) intravitreal therapeutic agents could potentially have synergistic effects for treating diabetic macular oedema (DMO). On the one hand, if combined treatment is more effective than monotherapy, there would be significant implications for improving patient outcomes. Conversely, if there is no added benefit of combination therapy, then people could be potentially exposed to unnecessary local or systemic side effects.

Objectives

To assess the effects of intravitreal agents that block vascular endothelial growth factor activity (anti‐VEGF agents) plus intravitreal steroids versus monotherapy with macular laser, intravitreal steroids or intravitreal anti‐VEGF agents for managing DMO.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) (2018, Issue 1); Ovid MEDLINE; Ovid Embase; LILACS; the ISRCTN registry; ClinicalTrials.gov and the ICTRP. The date of the search was 21 February 2018.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of intravitreal anti‐VEGF combined with intravitreal steroids versus intravitreal anti‐VEGF alone, intravitreal steroids alone or macular laser alone for managing DMO. We included people with DMO of all ages and both sexes. We also included trials where both eyes from one participant received different treatments.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures recommended by Cochrane.Two authors independently reviewed all the titles and abstracts identified from the electronic and manual searches against the inclusion criteria. Our primary outcome was change in best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) between baseline and one year. Secondary outcomes included change in central macular thickness (CMT), economic data and quality of life. We considered adverse effects including intraocular inflammation, raised intraocular pressure (IOP) and development of cataract.

Main results

There were eight RCTs (703 participants, 817 eyes) that met our inclusion criteria with only three studies reporting outcomes at one year. The studies took place in Iran (3), USA (2), Brazil (1), Czech Republic (1) and South Korea (1). Seven studies used the unlicensed anti‐VEGF agent bevacizumab and one study used licensed ranibizumab. The study that used licensed ranibizumab had a unique design compared with the other studies in that included eyes had persisting DMO after anti‐VEGF monotherapy and received three monthly doses of ranibizumab prior to allocation. The anti‐VEGF agent was combined with intravitreal triamcinolone in six studies and with an intravitreal dexamethasone implant in two studies. The comparator group was anti‐VEGF alone in all studies; two studies had an additional steroid monotherapy arm, another study had an additional macular laser photocoagulation arm. Whilst we judged these studies to be at low risk of bias for most domains, at least one domain was at unclear risk in all studies.

When comparing anti‐VEGF/steroid with anti‐VEGF monotherapy as primary therapy for DMO, we found no meaningful clinical difference in change in BCVA (mean difference (MD) −2.29 visual acuity (VA) letters, 95% confidence interval (CI) −6.03 to 1.45; 3 RCTs; 188 eyes; low‐certainty evidence) or change in CMT (MD 0.20 μm, 95% CI −37.14 to 37.53; 3 RCTs; 188 eyes; low‐certainty evidence) at one year. There was very low‐certainty evidence on intraocular inflammation from 8 studies, with one event in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group (313 eyes) and two events in the anti‐VEGF group (322 eyes). There was a greater risk of raised IOP (Peto odds ratio (OR) 8.13, 95% CI 4.67 to 14.16; 635 eyes; 8 RCTs; moderate‐certainty evidence) and development of cataract (Peto OR 7.49, 95% CI 2.87 to 19.60; 635 eyes; 8 RCTs; moderate‐certainty evidence) in eyes receiving anti‐VEGF/steroid compared with anti‐VEGF monotherapy. There was low‐certainty evidence from one study of an increased risk of systemic adverse events in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group compared with the anti‐VEGF alone group (Peto OR 1.32, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.86; 103 eyes).

One study compared anti‐VEGF/steroid versus macular laser therapy. At one year investigators did not report a meaningful difference between the groups in change in BCVA (MD 4.00 VA letters 95% CI −2.70 to 10.70; 80 eyes; low‐certainty evidence) or change in CMT (MD −16.00 μm, 95% CI −68.93 to 36.93; 80 eyes; low‐certainty evidence). There was very low‐certainty evidence suggesting an increased risk of cataract in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group compared with the macular laser group (Peto OR 4.58, 95% 0.99 to 21.10, 100 eyes) and an increased risk of elevated IOP in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group compared with the macular laser group (Peto OR 9.49, 95% CI 2.86 to 31.51; 100 eyes).

One study provided very low‐certainty evidence comparing anti‐VEGF/steroid versus steroid monotherapy at one year. There was no evidence of a meaningful difference in BCVA between treatments at one year (MD 0 VA letters, 95% CI ‐6.1 to 6.1, low‐certainty evidence). Likewise, there was no meaningful difference in the mean CMT at one year (MD ‐ 9 μm, 95% CI ‐39.87μm to 21.87μm between the anti‐VEGF/steroid group and the steroid group. There was very low‐certainty evidence on raised IOP at one year comparing the anti‐VEGF/steroid versus steroid groups (Peto OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.16 to 3.55).

No included study reported impact of treatment on patients' quality of life or economic data. None of the studies reported any cases of endophthalmitis.

Authors' conclusions

Combination of intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus intravitreal steroids does not appear to offer additional visual benefit compared with monotherapy for DMO; at present the evidence for this is of low‐certainty. There was an increased rate of cataract development and raised intraocular pressure in eyes treated with anti‐VEGF plus steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone. Patients were exposed to potential side effects of both these agents without reported additional benefit. The majority of the evidence comes from studies of bevacizumab and triamcinolone used as primary therapy for DMO. There is limited evidence from studies using licensed intravitreal anti‐VEGF agents plus licensed intravitreal steroid implants with at least one year follow‐up. It is not known whether treatment response is different in eyes that are phakic and pseudophakic at baseline.

Plain language summary

Anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (anti‐VEGF) plus intravitreal steroids for diabetic macular oedema

What is the aim of this review? The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out whether injecting two drugs in combination (inhibitors of VEGF and steroids) into the vitreous jelly of eyes with macular oedema (swelling at the centre of the retina) due to diabetes works better than treatment with one drug alone.

Key messages There is insufficient evidence to suggest that the two drugs in combination are better than treatment with one drug alone.

What was studied in the review? Diabetic macular oedema is swelling at the back of the eye (retina) in people with diabetes. It is the most common cause of aquired visual loss in the mainly working‐age population.

Both steroids and anti‐VEGF agents, injected into the vitreous jelly of the eye (intravitreal), improve vision and reduce the amount of fluid accumulating in the central retina. The drugs have different mechanisms of action and may work well in combination, with significant implications for improving patient outcomes. However, if there is no added benefit of combination therapy, then people could be potentially exposed to unnecessary side effects such as cataract, glaucoma, stroke and heart attack.

What are the main results of the review? The Cochrane Review authors found eight relevant studies. Three studies were from Iran, two from USA and one each from Brazil, Czech Republic and South Korea. These studies compared an anti‐VEGF (in most studies an unlicensed version called bevacizumab) plus intravitreal steroid agents versus anti‐VEGF alone, an intravitreal steroid alone or macular laser alone.

We found insufficient evidence to suggest that the two drugs classes in combination are better than treatment with one drug class alone as the initial treatment for diabetic macula oedema. Moreover, there was a greater risk of raised intraocular pressure and cataract in people receiving anti‐VEGF plus steroids compared with anti‐VEGF alone.

How up‐to‐date is this review? Cochrane Review authors searched for studies that had been published up to 21 February 2018.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The worldwide prevalence of diabetes mellitus was estimated at 366 million in 2011, with projections that by 2030 the prevalence will reach 552 million people (International Diabetes Federation 2011). Diabetic macular oedema (DMO) is the most common cause of acquired visual loss in this population, affecting approximately 6.8% of all people with diabetes (Antonetti 2012; Bunce 2008; Moss 1998; Yau 2012).

Description of the intervention

Systemic therapies aim to prevent or reduce DMO by targeting key modifiable risk factors. However, intensive control of glucose and blood pressure in clinical trials has achieved only limited success in preventing diabetic retinopathy (Liew 2008). There may also be a role for modification of the renin‐angiotensin system and for lipid‐lowering agents in the management of DMO (Kiire 2013). Fenofibrate may have a beneficial effect, although its mechanism of action appears to be independent of serum lipid concentration (Keech 2007; Liew 2008; Scheen 2010).

Up until the introduction of intravitreal pharmacotherapies, the standard of care for DMO was focal or grid laser photocoagulation. The Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS), which was undertaken in the 1980s, showed benefit of laser for DMO compared with no intervention (ETDRS 1991). In this trial the three‐year risk of moderate visual loss, defined as a loss of 15 letters or 3 lines of LogMAR visual acuity, decreased by 50% in laser‐treated eyes. Nonetheless, in most people with DMO, laser does not improve vision. Thus there was a major unmet need in terms of better treatments for DMO.

A systematic review found little evidence to support vitrectomy as an intervention for DMO in the absence of epiretinal membrane or vitreomacular traction (Simunovic 2014).

Some authors have proposed intravitreal steroid formulations such as triamcinolone acetate injections (IVTA), slow‐release dexamethasone implants and sustained‐release fluocinolone acetonide implants to treat clinically significant DMO (Boyer 2011; Campochiaro 2012; Gillies 2009). A Cochrane Review of intravitreal steroids in DMO concluded that steroids placed inside the eye by either intravitreal injection or surgical implantation may improve visual outcomes in eyes with persistent or refractory DMO; however, eyes treated with these formulations also frequently experience elevation of intraocular pressure and cataract progression (Grover 2008).

A Cochrane Review of antiangiogenic therapy in DMO identified strong evidence of a clinical benefit in maintaining and improving vision using anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (anti‐VEGF) drugs versus laser photocoagulation (Virgili 2014). The systematic review reported that further data are needed to assess effectiveness under real‐world monitoring and treatment conditions as well as safety (particularly regarding cardiovascular risk) in high‐risk populations excluded from clinical trials (Virgili 2014; Virgili 2017; Wong 2008).

Combinations of the above intravitreal anti‐VEGF and steroid formulations are the subject of this review.

How the intervention might work

Diabetic macular oedema is multifactorial, with significantly elevated levels of VEGF, interleukin‐6, and intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 in people with extensive DMO leakage versus those with minimal leakage (Funatsu 2003; Funatsu 2005). Post hoc analyses of head‐to‐head clinical trial data have reported differences between the effects of intravitreal anti‐VEGF and intravitreal steroids on surrogate endpoints of hard exudate resolution and vessel calibre diameter, suggesting different mechanisms of action in resolving DMO (Mehta 2016; Wickremasinghe 2017). Steroid therapy has anti‐inflammatory, anti‐permeability and angiostatic effects in treating DMO (Wang 2008). Anti‐VEGF agents, by inhibition of VEGF angiogenic activity on endothelial tight junctions, reduce retinal vascular permeability (Aiello 2005). The combination of steroid and anti‐VEGF intravitreal therapeutic agents could potentially have synergistic effects for treating DMO (Amoaku 2015).

Why it is important to do this review

This systematic review will assess the effects of combining intravitreal anti‐VEGF and steroid agents for managing DMO. We will assess the evidence base as to whether combining the intravitreal therapies has any advantage over monotherapy with macular laser, intravitreal steroids or intravitreal anti‐VEGF agents in terms of functional (visual acuity) and anatomical (central macular thickness) outcomes. We will also address how the safety profile of the combined treatment compares to monotherapy. On the one hand, if combined treatment is more effective than monotherapy, there would be significant implications for improving patient outcomes worldwide. On the other hand, if there is no added benefit of combination therapy, then people could be potentially exposed to unnecessary local or systemic side effects.

Objectives

To assess the effects of intravitreal agents that block vascular endothelial growth factor activity (anti‐VEGF agents) plus intravitreal steroids versus monotherapy with macular laser, intravitreal steroids or intravitreal anti‐VEGF agents for managing diabetic macular oedema.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

We included people with diabetic macular oedema (DMO) of all ages and both sexes as diagnosed in the included studies. We included trials where the eyes from one participant had received different treatments.

Types of interventions

We included RCTs comparing intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus intravitreal steroids versus intravitreal anti‐VEGF alone, intravitreal steroids alone or macular laser alone for managing DMO.

Types of outcome measures

We excluded studies with follow‐up of less than six months.

Primary outcomes

Visual acuity

The primary outcome for this review was mean change in best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) from baseline in the treated eye. We also assessed the proportion of eyes with at least 10 ETDRS letters' (equivalent to 2 ETDRS lines') change (Bailey 1976). Our primary analysis was at one year after randomisation.

Secondary outcomes

Visual acuity

We also assessed the above visual acuity outcomes at six months and at two years.

Anatomical outcomes

Mean change in central macular thickness (μm) as measured by optical coherence tomography (OCT) at six months, one year and two years.

Safety

We reported the frequency and severity of ocular or systemic adverse outcomes in the studies. In particular, we identified the following ocular adverse events reported in included randomised clinical trials: endophthalmitis, retinal tears or detachment, intraocular inflammation, development of cataract, raised intraocular pressure and need for glaucoma drainage surgery. We also recorded systemic side effects including thromboembolic events (as defined by the Antiplatelet Trialists' Collaboration), non‐ocular haemorrhage and hypertension (APTC 1994; Boyer 2009).

Economic data

We reported any cost benefit data in the included studies.

Quality of life data

We reported any quality of life data in the included studies.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for RCTs and controlled clinical trials. There were no language or publication year restrictions. The date of the search was 21 February 2018.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 1) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) in the Cochrane Library (searched 21 February 2018) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 21 February 2018) (Appendix 2);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 21 February 2018) (Appendix 3);

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database (1982 to 21 February 2018) (Appendix 4);

ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch; searched 21 February 2018) (Appendix 5);

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 21 February 2018) (Appendix 6);

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp; searched 21 February 2018) (Appendix 7).

Searching other resources

We handsearched the reference lists of the included trials to try to identify other relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Selection of studies

Two authors independently reviewed all the titles and abstracts identified from the electronic and manual searches against the inclusion criteria. We obtained full‐text copies of all potentially or definitely relevant articles. We contacted trial investigators for further information if required. We resolved discrepancies between authors as to whether or not studies met inclusion criteria by discussion. We documented the excluded studies and reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

We extracted the following participant and trial characteristics and reported them in a table format (Appendix 8).

Participant characteristics (age, sex, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), diagnostic criteria used for DMO, baseline visual acuity, OCT‐determined central macular thickness, and fluorescein angiography assessment of macular ischaemia).

Intervention (agent, dose, timing of first dose in relation to diagnosis, delivery route, frequency, treatment length).

Methodology (group size, randomisation, masking).

Results (visual acuity, central macular thickness, and adverse events).

Additional data (economic data, quality‐of‐life data).

Treatment compliance and losses to follow‐up.

We contacted trial investigators for key unpublished information that was missing from the reports of the included studies. Two review authors independently extracted the data and recorded it on paper data extraction forms developed by Cochrane Eyes and Vision. We resolved discrepancies by discussion. One review author entered all data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (Review Manager 2014), and a second author checked that the data entered were correct.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias of the selected trials according to Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We considered the following main criteria.

• Selection bias: random sequence generation, allocation concealment. • Performance bias: masking of participants, researchers and outcome assessors. • Attrition bias: loss to follow‐up, rates of compliance. • Reporting bias: selective outcome reporting.

We reported each parameter as being at high risk of bias, low risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias. We resolved discrepancies between the authors by discussion. We contacted study authors to clarify details for any studies at unclear risk of bias. If there was no response from the authors, we classified the trial based on available information.

For multi‐arm studies, we analysed multiple intervention groups in an appropriate way that avoided arbitrary omission of relevant groups and prevented double counting of participants.

Measures of treatment effect

We measured treatment effects according to the data types described in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011).

Dichotomous data

Variables in this group include the primary outcome and the proportion of participants experiencing an adverse event during follow‐up. We reported dichotomous variables as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Continuous data

These variables include mean change in visual acuity and central macular thickness. We reported continuous variables as mean difference with 95% CI (if normally distributed) or median and interquartile range (if not normally distributed).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis for efficacy of treatment and ocular safety was the eye for which the data had been reported on.

Trials could randomise one or both eyes to the intervention or comparator. If people were randomly allocated to treatment but the trial included only one eye per person, then there was no unit of analysis issue. In these cases, we documented how investigators selected the included eye. If people were randomly allocated to treatment but trials included and reported on both eyes, we adjusted for within‐person correlation by analysing as 'clustered data'. If the study was a within‐person study, i.e. one eye was randomly allocated to intervention and the other eye received the comparator, then we analysed the results as paired data. If required, we contacted the trial investigators for further information to carry out these analyses.

The unit of analysis for systemic safety, economic and quality of life measures was the individual, with inferences as to effect of a treatment at the person level based on unpaired data only.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to identify key unpublished information that was missing from reports of included studies by contacting study authors. If the authors did not respond within four weeks or were not able to provide additional data, we conducted a primary analysis based on participants with complete data (available case analysis). We made a judgement as to the risk of bias based on the amount and distribution of missing data in the study arms. Missing standard deviations were imputed using the largest reported standard deviation from the remaining included studies. We conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding studies with missing standard deviations.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered sources of heterogeneity related to study design (such as paired studies versus studies including only one eye of each participant) and baseline characteristics. We used I² value to determine the proportion of the variation that reflects variation in true effects (Higgins 2011). We considered I² values of greater than 50% to represent substantial heterogeneity not attributed to random error.

Data synthesis

If there was no substantial clinical or statistical heterogeneity between the trials, we combined the results in a meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model. We used a fixed‐effect model if there were three or fewer trials. We also used this model if there were forest plots with few events, in which case we expressed effect measures as Peto odds ratios (ORs). In case of substantial clinical or statistical heterogeneity, we did not combine study results but presented a narrative or tabulated summary. An exception where pooling of data would still occur even in the presence of substantial statistical heterogeneity would be where examination of the forest plot indicated the individual trial results were all consistent in their direction of effect (i.e. the risk ratio and confidence intervals largely fall on one side of the line of null effect).

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analyses on the primary review outcome to determine the impact of excluding studies with missing data such as standard deviations, lower methodological quality (defined as high risk of bias in one or more domains),.

Summary of findings table

A 'Summary of findings' table provides key information concerning the certainty of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all specified review primary and secondary outcomes for a given comparison. Two review authors independently used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence for each outcome as described in the standard methods of Chapters 11 and 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011a; Schünemann 2011b). We resolved discrepancies by discussion.

Results

Description of studies

There was not sufficient data at participant level in the included studies to assess for clustered data in trials with a paired design. We considered paired versus studies with only one eye per participant as a source of heterogeneity but all included studies reporting the primary outcome at one year had the possibility of both eyes being enrolled.

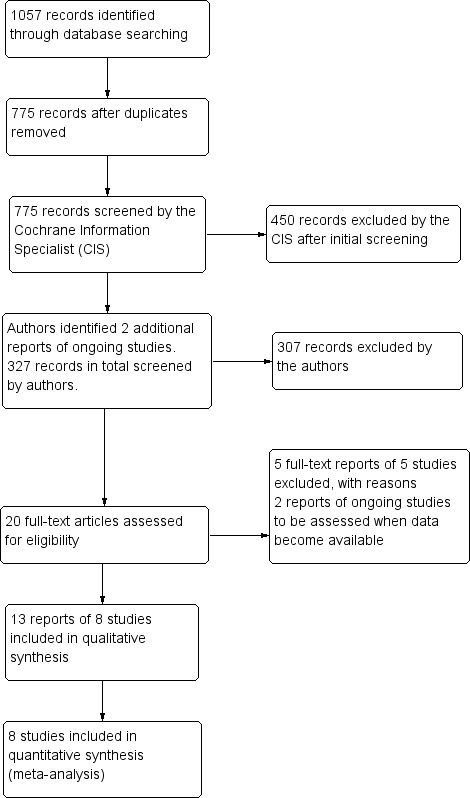

Results of the search

The electronic searches yielded a total of 1057 records (Figure 1). After removing 282 duplicates, the Cochrane Information Specialist screened the remaining 775 records and removed 450 references that were not relevant to the review. We made additional searches of the ongoing trials registers and identified a further two studies for assessment. We screened 327 references and obtained 20 full‐text reports for further assessment. We included 13 reports of eight studies (see Characteristics of included studies ), and excluded five studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies). We identified two ongoing studies (NCT03126786; UMIN000021630) and will assess these for potential inclusion in the review when data becomes available.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 13 publications of eight RCTs in this review (DRCRnet U 2018; Lim 2012; Maturi 2015; Neto 2017; Riazi‐Esfahani 2017; Shoeibi 2013; Soheilian 2012; Synek 2011). Most studies used the unlicensed anti‐VEGF agent bevacizumab and one study used ranibizumab (DRCRnet U 2018). Regarding the use of intravitreal steroid, six studies used intravitreal triamcinolone, whilst two studies used the intravitreal dexamethasone implant (DRCRnet U 2018; Maturi 2015). Two of the RCTs (Shoeibi 2013; Soheilian 2012) had used selected population subgroups referencing participants from previous trials (Ahmadieh 2008; Soheilian 2009;Yaseri 2014). One study (DRCRnet U 2018) had a unique design compared with the other studies in that included eyes had persisting DMO after anti‐VEGF monotherapy and received three monthly doses of ranibizumab prior to allocation.Three studies were from Iran and one each from the Republic of Korea, the USA and the Czech Republic. We have documented the number of participants and eyes in each study and a summary of the characteristics of the study populations and settings, interventions, comparators and funding sources in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Excluded studies

We excluded five studies because of insufficient length of follow‐up (Faghihi 2008; Sheth 2011; Soheilian 2007; Wang 2011; Yu 2018). See the Characteristics of excluded studies table for further information.

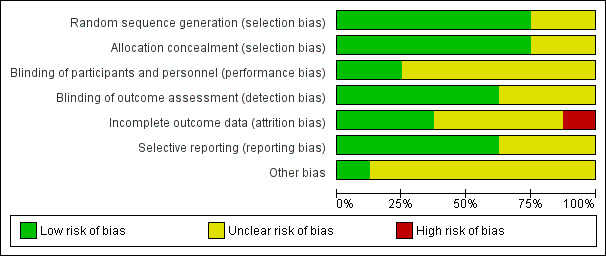

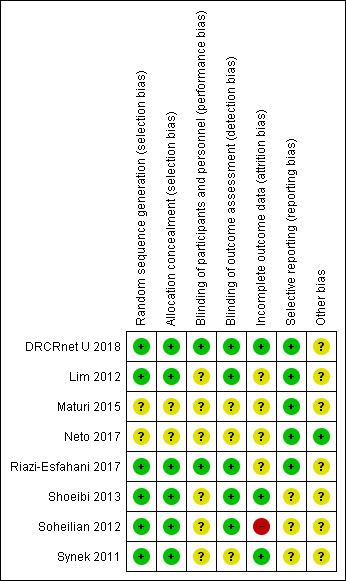

Risk of bias in included studies

All included studies were at unclear risk of bias in one or more domains (see Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We judged the risk of selection bias to be low in most studies. In Maturi 2015 and Neto 2017 the methods of generating and concealing the allocation sequence were not reported in enough detail to make a judgement.

Blinding

In five studies, authors stated that participants were masked to treatment allocation (Maturi 2015; Riazi‐Esfahani 2017; Shoeibi 2013; Soheilian 2012; Synek 2011), but only two trials also masked the investigators delivering treatment (DRCRnet U 2018; Riazi‐Esfahani 2017). Five trials specified that masked investigators assessed outcome measures (DRCRnet U 2018; Lim 2012; Riazi‐Esfahani 2017; Shoeibi 2013; Soheilian 2012), but this was not reported in the other three studies (Maturi 2015; Neto 2017; Synek 2011).

Incomplete outcome data

Three studies were judged to be at low risk of attrition bias as follow‐up was high (DRCRnet U 2018; Shoeibi 2013; Synek 2011). Soheilian 2012 was judged to be at high risk of attrition bias because of unequal loss to follow‐up in the groups, possibly attributable to adverse events. For the other studies, follow‐up was not reported in enough detail to make a judgement.

Selective reporting

Visual acuity and central macular thickness (CMT) data were in general well recorded. Authors did not always include safety data, particularly relating to systemic safety. The included RCTs were not powered to identify small increases in ocular or systemic harm.

Other potential sources of bias

Most studies enrolled a small proportion of participants with both eyes affected. Both eyes being eligible for allocation in a single individual poses the theoretical potential to influence outcomes in the fellow eye via systemic absorption.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings: intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus intravitreal steroid versus intravitreal anti‐VEGF for diabetic macular oedema.

| Intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus intravitreal steroid versus intravitreal anti‐VEGF for diabetic macular oedema | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with centre‐involving diabetic macular oedema Settings: eye care clinic Intervention: intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus intravitreal steroid (anti‐VEGF/steroid) Comparison: intravitreal anti‐VEGF | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of eyes (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Anti‐VEGF alone | Anti‐VEGF/steroid | |||||

|

Mean change in visual acuity at 1 year (number of letters read on logMAR chart) |

The mean visual acuity gain at 1 year ranged from 4.9 to 10.5 letters in the anti‐VEGF alone groups | The mean number of letters read was on average 2.29 fewer in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group (95% CI −6.03 to 1.45) | — | 188 (3) |

Lowa | — |

| Mean change in central macular thickness at 1 year | The mean reduction in central macular thickness at 1 year ranged from −30 μm to −179 μm in the anti‐VEGF alone groups | The mean reduction in central macular thickness was on average 0.20 μm greater in the anti‐VEGF/steroid groups (95% CI −37.14 to 37.53) | — | 188 (3) |

Lowa | — |

| Significant intraocular inflammation at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | 6 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (0 to 30 per 1000) |

Peto OR 0.53 (0.05 to 5.08) | 635 (8) |

Very lowb | Only 3 events |

| Development of cataract at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | 3 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (9 to 56 per 1000) |

Peto OR 7.49 (2.87 to 19.60) | 635 (8) |

Moderatec | NB: significant cataract progression may occur in the second year of intravitreal steroid use. |

| Raised intraocular pressure at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | 6 per 1000 | 47 per 1000 (27 to 79 per 1000) |

Peto OR 8.13 (4.67 to 14.16) | 635 (8) |

Moderatec | 1 participant needed glaucoma surgery in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group.This outcome occurred only in 1 study. The threshold for glaucoma drainage surgery was not specified. |

| Systemic adverse events at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | 400 per 1000 | 468 per 1000 (289 to 1000) |

Peto OR 1.32 (95% CI 0.61 to 2.86) |

103 (1) |

Lowd | |

| Quality of life at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | Not reported | |||||

| *The assumed risk is the control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention. CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; MD: mean difference; SD: standard deviation. | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level because of risk of bias and by one level because of imprecision. bDowngraded one level because of risk of bias, and two levels for imprecision as there were very few events.

cDowngraded one level because of risk of bias

dDowngraded two levels for imprecision

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings: intravitreal bevacizumab plus intravitreal steroid versus macular laser for diabetic macular oedema.

| Intravitreal bevacizumab plus intravitreal steroid versus macular laser for diabetic macular oedema | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with centre‐involving diabetic macular oedema Setting: eye care clinic Intervention: intravitreal bevacizumab plus intravitreal steroid (anti‐VEGF/steroid) Comparison: macular laser | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of eyes (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Macular laser | Anti‐VEGF/steroid | |||||

|

Mean change in visual acuity at 1 year (number of letters read on logMAR chart) |

The mean visual acuity gain at 1 year was 1 letter with a standard deviation of 17 letters in the laser comparator group | The mean number of letters read was 4.00 more in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group (95% CI −2.70 to 10.70) | — | 80 (1) | Lowa | |

| Gain or loss of 10 or more letters visual acuity at 1 year | Not reported | |||||

| Mean change in central macular thickness at 1 year | The mean change in central macular thickness at 1 year was an increase of 6 μm with a standard deviation of 36 microns in the laser comparator group | The mean reduction in central macular thickness was on average 16 μm greater in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group (95% CI −68.93 to 36.93) | — | 80 (1) | Lowa | |

| Significant intraocular inflammation at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | Not reported | |||||

| Development of cataract at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | 20 per 1000 | 85 per 1000 (20 to 301 per 1000) |

Peto OR 4.58 (0.99 to 21.10) | 100 (1) | Very lowb | |

| Raised Intraocular Pressure at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | 1 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (3 to 31 per 1000) |

Peto OR 9.49 (2.86 to 31.51) | 100 (1) | Very lowb | There was 1 participant who needed glaucoma drainage surgery in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group. Threshold for glaucoma drainage surgery not specified in the included study. |

| Systemic adverse events at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | Not reported | |||||

| Quality of life at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | Not reported | |||||

| *The assumed risk is the control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention. CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; MD: mean difference; SD: standard deviation. | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level because of risk of bias and by one level due to imprecision.

bDowngraded one level because of risk of bias and by two levels due to imprecision (only 1 event in the comparator group).

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings: intravitreal bevacizumab plus intravitreal steroid versus intravitreal steroid for diabetic macular oedema.

| Intravitreal bevacizumab plus intravitreal steroid compared with intravitreal steroid for diabetic macular oedema | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with centre‐involving diabetic macular oedema Setting: eye care clinic Intervention: intravitreal bevacizumab plus intravitreal steroid (anti‐VEGF/steroid) Comparison: intravitreal steroid (IVS) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of eyes (studies) | Certainity of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| IVS | Anti‐VEGF/steroid | |||||

|

Mean change in visual acuity at 1 year (number of letters read on logMAR chart) |

The mean visual acuity at 1 year was 24.5 letters in the IVS comparator group | The mean number of letters read was on average 0 letters higher (i.e same) in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group (95% CI ‐6.1 to 6.1) | ‐ | 73 (1) |

Lowa | SD not reported for change in visual acuity so difference in visual acuity at 1 year reported |

| Gain or loss of 10 or more letters visual acuity at 1 year | Not reported | |||||

| Mean change in central macular thickness at 1 year | The mean central macular thickness was 249 μm in the IVS comparator group at 1 year | The mean central macular thickness was 9 μm less in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group (‐39.87μm less to 21.87μm more) | Not estimable | 73 (1) |

Lowa | SD not reported for change so difference in final value reported |

| Significant intraocular inflammation at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | Not reported | |||||

| Development of cataract at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | Not reported | |||||

| Raised intraocular pressure at 1 year at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | 108 per 1000 | 83 per 1000 (19 to 301 per 1000) |

Peto OR 0.75 (0.16 to 3.55) | 73 (1) |

Very Lowb | — |

| Systemic adverse events at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | Not reported | |||||

| Quality of life at follow‐up (from 6 months onwards) | Not reported | |||||

| The assumed risk is the control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention. CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; MD: mean difference; SD: standard deviation. | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level because of risk of bias and by one level for imprecision.

bDowngraded one level because of risk of bias and by two levels for imprecision (very few events).

See: Table 1 (anti‐VEGF/steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone); Table 2 (anti‐VEGF/steroid versus macular laser); Table 3 (anti‐VEGF/steroid versus steroid).

We could not perform meta‐analyses when comparing anti‐VEGF/steroid versus steroid monotherapy or macular laser monotherapy due to there only being one included studies reporting each comparison at 12 month. There was no evidence that BCVA and CMT data were skewed in included studies. There were no reported cases of endophthalmitis in included studies. Systemic side‐effects were not fully reported. We did not identify any relevant studies reporting cost benefit or quality of life outcomes. Therefore, we were unable to comment on these secondary outcomes.

Intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone

Visual outcome

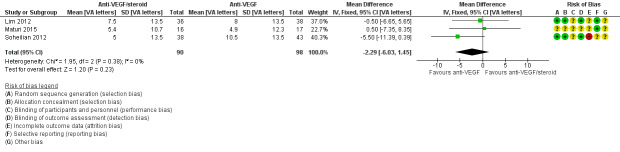

Eyes that received intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus steroid could read fewer average letters at one year compared with those receiving anti‐VEGF alone. The difference was small, and the confidence intervals (CIs) corresponded to either fewer or more letters being read (mean difference (MD) −2.29 visual acuity (VA) letters, 95% confidence interval (CI) −6.03 to 1.45, P = 0.23; 188 eyes; 3 studies, Figure 4). The same pattern was apparent at six months (MD ‐0.88 VA letters, 95% CI ‐2.56 to 0.80; 618 eyes; 8 studies, Analysis 1.1) and at two years (MD −0.50 VA letters, 95% CI −8.42 to 7.42; 75 eyes, 1 study, Analysis 1.3). One study (DRCRnet U 2018) reported 10 letter gain and loss of vision at 6 months. An improvement of 10 letters or more was observed in 14 of the 63 eyes (22%) in the anti‐VEGF plus steroid group and 9 of the 64 eyes (14%) in the anti‐VEGF group (adjusted difference, 6%; 95 CI −6% to 18%; P = 0.34). In the anti‐VEGF plus steroid group, 8 eyes (13%) lost 10 letters or more compared with 4 (6%) for anti‐VEGF group (adjusted difference, 7%; 95% CI, −1% to 16%; P = 0.09); We judged the certainty of the visual acuity evidence described above to be low, downgrading for risk of bias in the included trials and imprecision (confidence intervals include both no effect and clinically important differences).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone, outcome: 1.2 Mean change in visual acuity at 1 year [VA letters].

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone, Outcome 1 Mean change in visual acuity at 6 months.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone, Outcome 3 Mean change in visual acuity at 2 years.

Central macular thickness

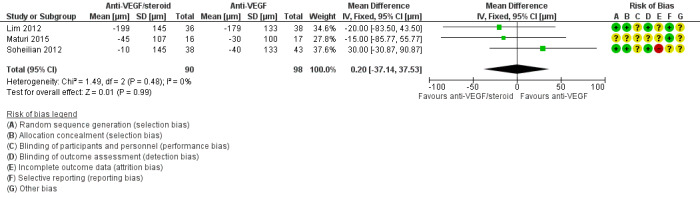

Eyes that received intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus steroid had reduced CMT at one year compared with those receiving anti‐VEGF alone. The difference was negligible, and the confidence intervals corresponded to either increased or decreased CMT (MD −0.20 μm, 95% CI −37.14 to 37.53, P = 0.99; 188 eyes; 3 studies; Figure 5). There were similar results at six months (MD ‐19.73 μm, 95% CI ‐40.47 to 1.01; 617 eyes; 8 studies, Analysis 1.4) and at two years (MD 22.00 μm, 95% CI −45.93 to 89.93; 75 eyes, 1 study, Analysis 1.6).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 anti‐VEGF/steroid versus anti‐VEGF, outcome: 1.5 Mean change in central macular thickness at 1 year [μm].

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone, Outcome 4 Mean change in central macular thickness at 6 months.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone, Outcome 6 Mean change in central macular thickness at 2 years.

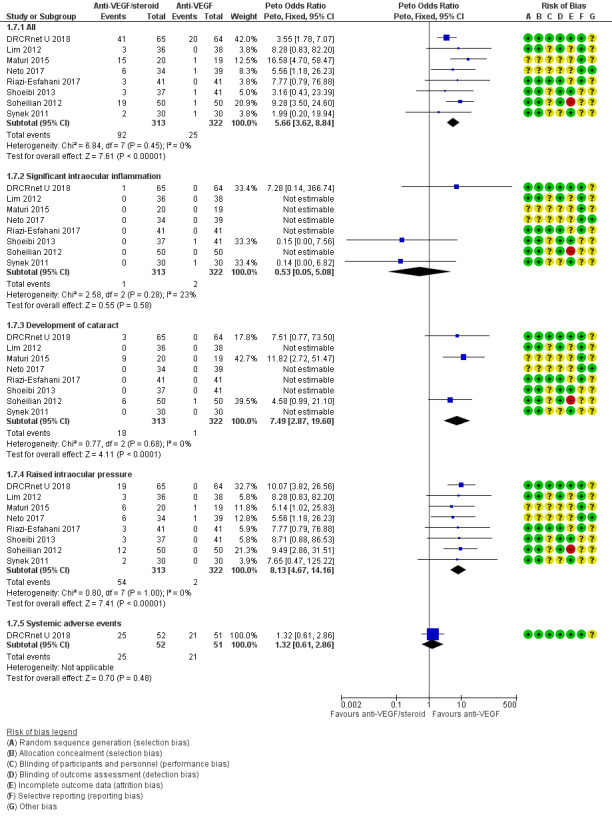

Adverse effects

Table 4 and Figure 6 summarises the adverse events. There were 92 reported adverse events in eyes receiving intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus steroids compared with 25 adverse events in those receiving intravitreal anti‐VEGF alone (Peto OR 5.66, 95% CI 3.62 to 8.84; 635 eyes; 8 studies). There was less significant intraocular inflammation in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group (Peto OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.05 to 5.08; 635 eyes; 8 studies) however, evidence was of very low‐certainty with 1 event in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group (313 eyes) and 2 events in the anti_VEGF group (322 eyes), Development of cataract was more frequent in eyes receiving anti‐VEGF/steroid compared with IVB (Peto OR 7.49, 95% CI 2.87 to 19.60; 635 eyes; 8 studies) however, evidence was of very low‐certainty, with 18 events in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group (313 eyes) and 1 event in the anti‐VEGF group (322 eyes). Readers should note that cataract development due to intravitreal steroid often occurs after the first year of treatment. There was a substantially greater risk of raised intraocular pressure in eyes receiving anti‐VEGF/steroid compared with anti‐VEGF alone (Peto OR 8.13, 95% CI 4.67 to 14.16; 635 eyes; 8 studies).

1. Adverse events.

| Significant ocular inflammation | Development of cataract | Raised intraocular Pressure | Need for glaucoma drainage surgery | Sample size | |

| Intravitreal anti‐VEGF + steroid | |||||

| Lim 2012 | — | 0 | 3 | 0 | 36 |

| Maturi 2015 | — | 9 | 6 | 0 | 20 |

| DRCRnet U 2018 | 1 | 3 | 19 | 0 | 65 |

| Neto 2017 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 34 |

| Riazi‐Esfahani 2017 | — | — | 3 | — | 41 |

| Shoeibi 2013 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 37 |

| Soheilian 2012 | — | 6 | 12 | 1 | 50 |

| Synek 2011 | — | 0 | 2 | 0 | 30 |

| Total | 1 | 18 | 54 | 1 | 313 |

| Intravitreal anti‐VEGF | |||||

| Lim 2012 | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 |

| Maturi 2015 | — | 0 | 1 | 0 | 19 |

| DRCRnet U 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 64 |

| Neto 2017 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 39 |

| Riazi‐Esfahani 2017 | — | 0 | — | — | 41 |

| Shoeibi 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 41 |

| Soheilian 2012 | — | 1 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| Synek 2011 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| Total | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 322 |

| Intravitreal steroid | |||||

| Lim 2012 | — | 0 | 4 | 0 | 37 |

| Maturi 2015 | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| DRCRnet U 2018 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Neto 2017 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 38 |

| Riazi‐Esfahani 2017 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Shoeibi 2013 | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| Soheilian 2012 | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| Synek 2011 | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| Total | — | 0 | 10 | 0 | 75 |

| Macular laser | |||||

| Lim 2012 | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| Maturi 2015 | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| DRCRnet U 2018 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Neto 2017 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Riazi‐Esfahani 2017 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Shoeibi 2013 | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| Soheilian 2012 | — | 1 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| Synek 2011 | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| Total | — | 1 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone, outcome: 1.7 Adverse events.

One study (DRCRnet U 2018) with six month follow‐up reported systemic adverse events. The study defined a systemic adverse event as: resulted in death, was life threatening, required hospitalisation or prolongation of an existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability /incapacity; was a congenital anomaly/birth defect. The difference was small, and the confidence intervals corresponded to either fewer or more events occurring. There were more systemic adverse events in the the anti‐VEGF/steroid group (Peto OR 1.32, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.86; 103 eyes; 1 study) with 25 events in the anti‐VEGF plus steroid group (52 eyes) and 21 events in the anti‐VEGF group (51 eyes).

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted three sensitivity analyses on the one year data. One analysis excluded Lim 2012 because the study did not report standard deviations for change in visual loss or CMT and had a high risk of selection bias. Another excluded Maturi 2015 because the study received funding from industry and also had a high risk of selection bias. The third analysis excluded Soheilian because the study had a high risk of attrition bias.The results were reasonably robust.

| Analysis | Change in visual acuity (VA) at one year Mean difference (95% CI) |

Change in central macular thickness at one year Mean difference (95% CI) |

| All 3 studies (Lim 2012; Maturi 2015; Soheilian 2007) | ‐2.29 VA letters (‐6.03 to 1.45) | 0.20 μm (‐37.14 to 37.53) |

| Excluding Lim 2012 | ‐3.34 VA letters (‐8.05 to 1.37) | 10.86 μm (‐35.29 to 57.01) |

| Excluding Maturi 2015 | ‐3.11 VA letters (‐7.36 to 1.15) | 6.05 μm (‐37.89 to 50.00) |

| Excluding Soheilian 2012 | ‐0.12 VA letters (‐4.96 to 4.72) | ‐17.77μm (‐65.03 to 29.49) |

Intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus steroid compared to macular laser

Visual outcomes

See Analysis 2.1.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus macular laser, Outcome 1 Mean change in visual acuity.

Eyes that received intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus steroid could, on average, read more letters at one year than those receiving macular laser. The difference was small, and the confidence interval corresponded to either fewer or more letters being read (MD 4.00 VA letters, 95% CI −2.70 to 10.70; 80 eyes; 1 study). The study reported the same pattern at 6 months (MD 6.00 VA letters, 95% CI −0.46 to 12.46; 86 eyes; 1 study) and at two years (MD 3.00 VA letters, 95% CI −4.52 to 10.52; 74 eyes; 1 study). However, participants in this trial received intravitreal anti‐VEGF no more frequently than once every 12 weeks, which is considerably less than more recent trials.

Central macular thickness

See Analysis 2.2

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus macular laser, Outcome 2 Mean change in central macular thickness.

Eyes that received intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus steroids had more reduction in CMT at one year compared with those receiving macular laser. The difference was small, and the confidence interval corresponded to either increased or decreased CMT (MD 16.00 μm, 95% CI −68.93 to 36.93; 80 eyes; 1 study).

Adverse effects

See Analysis 2.3

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus macular laser, Outcome 3 Adverse events.

There were 19 adverse events in eyes receiving intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus steroids compared with 1 adverse event in eyes receiving macular laser (Peto OR 9.28, 95% CI 3.50 to 24.60; 100 eyes; 1 study). There was an increased risk of cataract in the anti‐VEGF and steroids group compared with macular laser (Peto OR 4.58, 95% CI 0.99 to 21.10; 100 eyes; 1 study). Risk of raised intraocular pressure was higher in eyes receiving anti‐VEGF plus steroids compared with macular laser (Peto OR 9.49, 95% CI 2.86 to 31.51; 100 eyes; 1 study).

Intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus steroid compared with steroid alone

Two studies compared anti‐VEGF/steroid versus IVS (Lim 2012; Neto 2017) with only one study having 1 year outcomes (Lim 2012). The steroid used was intravitreal triamcinolone in both trials. Lim 2012 did not report data on standard deviations for change in BCVA so we have included data on final value in the plot (Analysis 3.1). We judged the certainty of the VA and CMT evidence for this comparison to be low, downgrading for risk of bias in the included trials and imprecision (confidence intervals include both no effect and clinically important differences).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus steroid alone, Outcome 1 Mean change in visual acuity.

Visual outcomes

The mean change in BCVA at one year was 7.5 letters for eyes receiving anti‐VEGF/steroid therapy (36 eyes) compared with 8 letters in the steroid alone arm (37 eyes). The trial authors reported the standard deviation for final value only, not change. The mean difference in final value was 4 letters (95% CI ‐2.6 to 10.6) at six months and 0 letters (95% CI ‐6.1 to 6.1) at one year (Analysis 3.1).

Central macular thickness

The mean change in CMT at one year was −199 μm for eyes receiving anti‐VEGF/steroid therapy (36 eyes) compared with −200 μm in the steroid arm (37 eyes). The trial authors reported the standard deviation for final value only, not change. The mean difference in final value was 1.00 µm (95% CI ‐41.92 to 43.92) at six months and ‐9.00 µm (95% CI ‐39.87 to 21.87) at one year (Analysis 3.1).

Adverse effects

Raised intraocular pressure occurred at similar rates for eyes receiving intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus steroids versus steroid alone (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.19 to 3.20, 37 eyes; 1 study). There was a very low‐certainty of evidence with 3 events in the anti‐VEGF/steroid group (36 eyes) and 4 events in the steroid group (37 eyes).

Discussion

Summary of main results

There were eight included studies, all at unclear risk of bias in at least one domain. Eyes treated with a combination of inhibitors of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and steroid therapy achieved similar visual acuity and central macular thickness outcomes as those receiving monotherapy at one year. There was a greater risk of raised intraocular pressure in people receiving intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus steroids compared with anti‐VEGF monotherapy.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The included studies assessed the combination of intravitreal bevacizumab (off‐label) or ranibizumab and either intravitreal triamcinolone (off‐label) or dexamethasone implants for the management of diabetic macular oedema (DMO). There were no published randomised clinical trial results on the combination of licensed VEGF inhibitors with intravitreal steroid agents. Intravitreal bevacizumab was often given at lower frequency in the included studies than is generally recommended. Additionally, in the BEVORDEX randomised clinical trial, intravitreal dexamethasone implants given more frequently, with a minimum interval of 16 weeks, may have better results than the studies included in this review (BEVORDEX 2014, BEVORDEX 2016). Licenced intravitreal anti‐VEGF agents (e.g. aflibercept) may have greater efficacy than the unlicensed intravitreal bevacizumab used in most of the included studies (Virgili 2017).

Quality of the evidence

Many studies did not have sufficient length of follow‐up or were under‐powered to identify significant local (e.g. cataract or glaucoma) or systemic adverse events (e.g. stroke or heart attack). Typically, cataract develops in the second year of treatment. Ideally, trials that involve intravitreal steroid therapy should run for three years to allow sufficient time for cataract to develop, for cataract surgery to be undertaken, and for the study eye to stabilise following surgery. All included studies had unclear risk of bias in one or more domains and three studies (Lim 2012; Maturi 2015; Riazi‐Esfahani 2017) had a high risk of selection bias. Many included studies had a paired design for treatments, which have a theoretical potential to influence outcomes in the fellow eye via systemic absorption. Additionally the disease may not be symmetrical and the paired design may preclude pragmatic trials with economic and quality of life outcomes. Clustering risks could potentially be addressed with statistical methods such as generalised estimated equations, however this was not possible in this review due to absence of available individual patient level data in included studies. The GRADE scores of certainty of evidence from the included studies ranged from very low to moderate.

Potential biases in the review process

We used standard methodological procedures as recommended by Cochrane. As we found fewer than 10 studies, we were unable to use a funnel plot to identify possible publication bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of randomised clinical trials assessing inhibitors of VEGF plus intravitreal steroids for DMO.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Combination of intravitreal anti‐VEGF plus intravitreal steroids does not appear to offer additional visual benefit compared with monotherapy for DMO; at present the evidence for this is of low‐certainty. There was an increased rate of cataract development and raised intraocular pressure in eyes treated with anti‐VEGF plus steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone. Patients were exposed to potential side effects of both these agents without reported additional benefit. The majority of the evidence comes from studies of bevacizumab and triamcinolone used as primary therapy for DMO.

Implications for research.

Agreed standardised ocular (e.g. intraocular pressure rise) and systemic (e.g. cardiovascular events) safety outcome measures would allow easier comparison of results. Quality of life and cost benefit indices should also be reported in future clinical trials. Evaluating differences in the relative effect of inhibitors of VEGF and intravitreal steroids on proliferative diabetic retinopathy and foveal threatening hard exudates would help clinicians understand whether these agents can be used in combination to target different aspects of diabetic retinopathy. There is limited evidence from studies using licensed intravitreal anti‐VEGF agents plus licensed intravitreal steroid implants with at least one year follow‐up. It is not known whether treatment response is different in eyes that are phakic and pseudophakic at baseline. The role of combined inhibitors of VEGF and steroid implants for DMO specifically at the time of cataract surgery has not been addressed in the included randomised clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

Cochrane Eyes and Vision (CEV) created and executed the electronic search strategies and undertook data extraction for two studies (DRCRnet U 2018; Neto 2017). We thank Ms Anupa Shah, Mr Richard Wormald and Prof Gianni Virgili at the CEV UK editorial base for their assistance with this review. We are grateful to the peer reviewers, Dr Jennifer Evans, Dr Catey Bunce, Mr Ranjan Rajendram and Dr Mariachristina Parravano for their constructive comments in the development of this review. We thank Dora Newsom and Fang Fang at Sydney Eye Hospital Medical Library for assistance retrieving full‐text copies of relevant papers.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Macular Edema] explode all trees #2 macula* near/3 oedema #3 macula* near/3 edema #4 maculopath* #5 CME or CSME or CMO or CSMO #6 DMO or DME #7 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 #8 MeSH descriptor: [Diabetes Mellitus] explode all trees #9 MeSH descriptor: [Diabetic Retinopathy] this term only #10 MeSH descriptor: [Diabetes Complications] this term only #11 diabet* #12 retinopath* #13 #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 #14 #7 and #13 #15 MeSH descriptor: [Steroids] explode all trees #16 triamcin* #17 dexamethasone* #18 fluocinolone* #19 steroid* or glucocorticoid* #20 #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 #21 MeSH descriptor: [Angiogenesis Inhibitors] explode all trees #22 MeSH descriptor: [Angiogenesis Inducing Agents] explode all trees #23 MeSH descriptor: [Endothelial Growth Factors] explode all trees #24 anti near/2 VEGF* #25 endothelial near/2 growth near/2 factor* #26 anti next angiogen* #27 macugen* or pegaptanib* or lucentis* or rhufab* or ranibizumab* or bevacizumab* or avastin* or aflibercept* #28 VEGF TRAP* #29 #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 or #28 #30 #14 and #20 and #29

Appendix 2. MEDLINE Ovid search strategy

1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. (randomized or randomized).ab,ti. 3. placebo.ab,ti. 4. dt.fs. 5. randomly.ab,ti. 6. trial.ab,ti. 7. groups.ab,ti. 8. or/1‐7 9. exp animals/ 10. exp humans/ 11. 9 not (9 and 10) 12. 8 not 11 13. exp macular edema/ 14. (macula$ adj3 oedema).tw. 15. (macula$ adj3 edema).tw. 16. maculopath$.tw. 17. (CME or CSME or CMO or CSMO).tw. 18. (DMO or DME).tw. 19. or/13‐18 20. exp diabetes mellitus/ 21. diabetic retinopathy/ 22. diabetes complications/ 23. diabet$.tw. 24. retinopath$.tw. 25. or/20‐24 26. 19 and 25 27. exp steroids/ 28. triamcin$.tw. 29. dexamethasone$.tw. 30. fluocinolone.tw. 31. (steroid$ or glucocorticoid$).tw. 32. or/27‐31 33. exp angiogenesis inhibitors/ 34. exp angiogenesis inducing agents/ 35. exp endothelial growth factors/ 36. (anti adj2 VEGF$).tw. 37. (endothelial adj2 growth adj2 factor$).tw. 38. (anti adj1 angiogen$).tw. 39. (macugen$ or pegaptanib$ or lucentis$ or rhufab$ or ranibizumab$ or bevacizumab$ or avastin or aflibercept$).tw. 40. VEGF TRAP$.tw. 41. or/33‐40 42. 26 and 32 and 41 43. 12 and 42

The search filter for trials at the beginning of the MEDLINE strategy is from the published paper by Glanville 2006.

Appendix 3. Embase Ovid search strategy

1. exp randomized controlled trial/ 2. exp randomization/ 3. exp double blind procedure/ 4. exp single blind procedure/ 5. random$.tw. 6. or/1‐5 7. (animal or animal experiment).sh. 8. human.sh. 9. 7 and 8 10. 7 not 9 11. 6 not 10 12. exp clinical trial/ 13. (clin$ adj3 trial$).tw. 14. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj3 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 15. exp placebo/ 16. placebo$.tw. 17. random$.tw. 18. exp experimental design/ 19. exp crossover procedure/ 20. exp control group/ 21. exp latin square design/ 22. or/12‐21 23. 22 not 10 24. 23 not 11 25. exp comparative study/ 26. exp evaluation/ 27. exp prospective study/ 28. (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).tw. 29. or/25‐28 30. 29 not 10 31. 30 not (11 or 23) 32. 11 or 24 or 31 33. exp retina macula edema/ 34. (macula$ adj3 oedema).tw. 35. (macula$ adj3 edema).tw. 36. maculopath$.tw. 37. (CME or CSME or CMO or CSMO).tw. 38. (DMO or DME).tw. 39. or/33‐38 40. exp diabetes mellitus/ 41. diabetic retinopathy/ 42. diabet$.tw. 43. retinopath$.tw. 44. or/40‐43 45. 39 and 44 46. exp steroid/ 47. triamcin$.tw. 48. dexamethasone$.tw. 49. fluocinolone.tw. 50. (steroid$ or glucocorticoid$).tw. 51. or/46‐50 52. angiogenesis/ 53. angiogenesis inhibitors/ 54. angiogenesis factor/ 55. monoclonal antibody/ 56. exp endothelial cell growth factor/ 57. vasculotropin/ 58. (anti adj2 VEGF$).tw. 59. (endothelial adj2 growth adj2 factor$).tw. 60. (anti adj1 angiogen$).tw. 61. (macugen$ or pegaptanib$ or lucentis$ or rhufab$ or ranibizumab$ or bevacizumab$ or avastin or aflibercept$).tw. 62. VEGF TRAP$.tw. 63. or/52‐62 64. 45 and 51 and 63 65. 32 and 64

Appendix 4. LILACS search strategy

macula$ edema or macula$ oedema or DMO or DME or CMO or CME or CSMO and steroid$ or triamcin$ or dexamethasone$ or fluocinolone$ and angiogenesis or endothelial growth factor or macugen$ or pegaptanib$ or lucentis$ or rhufab$ or ranibizumab$ or bevacizumab$ or avastin$ or aflibercept$

Appendix 5. ISRCTN search strategy

"(diabetic macular edema OR DMO OR DME) AND (endothelial growth factor OR anti VEGF OR macugen OR pegaptanib OR lucentis OR rhufab OR ranibizumab OR bevacizumab OR avastin OR aflibercept) AND (steroid OR triamcinolone OR dexamethasone OR fluocinolone)"

Appendix 6. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

(diabetic macular edema OR DMO OR DME) AND (endothelial growth factor OR anti VEGF OR macugen OR pegaptanib OR lucentis OR rhufab OR ranibizumab OR bevacizumab OR avastin OR aflibercept) AND (steroid OR triamcinolone OR dexamethasone OR fluocinolone)

Appendix 7. WHO ICTRP search strategy

steroid OR triamcinolone OR dexamethasone OR fluocinolone = Title AND diabetic macular edema OR DMO OR DME = Condition AND endothelial growth factor OR anti VEGF OR macugen OR pegaptanib OR lucentis OR rhufab OR ranibizumab OR bevacizumab OR avastin OR aflibercept = Intervention

Appendix 8. Data on study characteristics

| Mandatory items | Optional items | |

| Methods | ||

| Study design |

|

Exclusions after randomization Losses to follow up Number randomized/analysed How were missing data handled? e.g. available case analysis, imputation methods Reported power calculation (Y/N), if yes, sample size and power Unusual study design/issues |

| Eyes or Unit of randomization/unit of analysis |

|

|

| Participants | ||

| Country(s) | Setting Ethnic group Equivalence of baseline characteristics (Y/N) |

|

| Total number of participants | This information should be collected for total study population recruited into the study. If these data are only reported for the people who were followed up only, please indicate. | |

| Number (%) of men and women | ||

| Average age and age range | ||

| Inclusion criteria | ||

| Exclusion criteria | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Intervention (n) Comparator (n) See MECIR 65 and 70 |

|

— |

| Outcomes | ||

| Primary and secondary outcomes as defined in study reports See MECIR R70 |

|

Planned/actual length of follow‐up |

| Notes | ||

| Date conducted | Specify dates of recruitment of participants month/year to month/year | Full study name: (if applicable) Reported subgroup analyses (Y/N) Were trial investigators contacted? |

| Sources of funding | ||

| Declaration of interest See MECIR 69 | ||

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mean change in visual acuity at 6 months | 8 | 618 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.88 [‐2.56, 0.80] |

| 2 Mean change in visual acuity at 1 year | 3 | 188 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.29 [‐6.03, 1.45] |

| 3 Mean change in visual acuity at 2 years | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Mean change in central macular thickness at 6 months | 8 | 617 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐19.73 [‐40.47, 1.01] |

| 5 Mean change in central macular thickness at 1 year | 3 | 188 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [‐37.14, 37.53] |

| 6 Mean change in central macular thickness at 2 years | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7 Adverse events | 8 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 All | 8 | 635 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.66 [3.62, 8.84] |

| 7.2 Significant intraocular inflammation | 8 | 635 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.05, 5.08] |

| 7.3 Development of cataract | 8 | 635 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.49 [2.87, 19.60] |

| 7.4 Raised intraocular pressure | 8 | 635 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.13 [4.67, 14.16] |

| 7.5 Systemic adverse events | 1 | 103 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.61, 2.86] |

| 8 Need for glaucoma drainage surgery | 8 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone, Outcome 2 Mean change in visual acuity at 1 year.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone, Outcome 5 Mean change in central macular thickness at 1 year.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone, Outcome 7 Adverse events.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus anti‐VEGF alone, Outcome 8 Need for glaucoma drainage surgery.

Comparison 2. Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus macular laser.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mean change in visual acuity | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 6 months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 1 year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 2 years | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Mean change in central macular thickness | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 6 months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 1 year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 2 years | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Adverse events | 1 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 All | 1 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Development of cataract | 1 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Raised intraocular pressure | 1 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 3. Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus steroid alone.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mean change in visual acuity | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 6 months | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 1 year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Mean change in central macular thickness | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 6 months | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 1 year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Raised intraocular pressure | 2 | 145 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.11, 1.04] |

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus steroid alone, Outcome 2 Mean change in central macular thickness.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Anti‐VEGF and steroid versus steroid alone, Outcome 3 Raised intraocular pressure.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

DRCRnet U 2018.

| Methods |

Study design: parallel group RCT/within‐person study (40 clinical centres) Unit of randomisation:people and eyes if both eyes eligible Number randomised: 116 people, 129 eyes Unit of analysis: individual eyes Sample size: For a sample size of 70 study eyes per group (increased to 75 to account for approximately 5% loss to follow‐up), a 2‐sided 95% CI for the difference in the 2 means of visual acuity change from randomisation to 24 week visit will extend 2.3 visual acuity letter score in either direction from the observed difference in means, assuming that the common standard deviation is a letter score of 7, not adjusting for correlation between eyes in participants with 2 study eyes. |

|

| Participants |

Country: USA Mean age: 65 years Sex: 67 women; 62 men Underlying condition: persistent DMO Inclusion criteria: age ≥ 18 years; diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (type 1 or type 2); meets all of the following ocular criteria in at least the one eye: at least 3 injections of anti‐VEGF drug (ranibizumab, bevacizumab, or aflibercept) within the prior 20 weeks, visual acuity letter score in study eye ≤ 78 and ≥ 24 LogMAR letters (approximate Snellen equivalent 20/32 to 20/320), on clinical exam, definite retinal thickening due to DMO involving the centre of the macula, OCT CMT thickness greater than 300 μm before adjusting for sex and machine‐specific factors Exclusion criteria: chronic kidney disease, renal transplant; unstable medical status including blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and glycaemic control; participation in an investigational trial within 30 days of enrolment; systolic blood pressure > 180 mmHg; acute cardiovascular event within 1 month prior to enrolment; systemic steroid, anti‐VEGF or pro‐VEGF treatment within prior 4 months; pregnant; macular oedema is considered to be due to a cause other than DMO; an ocular condition is present (other than DMO) that, in the opinion of the investigator, might affect macular oedema or alter visual acuity during the course of the study; substantial posterior capsule opacity; history of intravitreal anti‐VEGF drug within 21 days prior to enrolment; history of intravitreal or peribulbar corticosteroids within 3 months prior to enrolment; history of macular laser photocoagulation within 4 months prior to enrolment; laser therapy within 4 previous months; any history of vitrectomy. |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention: intravitreal ranibizumab (0.3 mg) and dexamethasone implant (0.7g) Comparator:intravitreal ranibizumab (0.3 mg) and sham injection Dexamethasone: sustained dexamethasone drug delivery system. Retreatment: ranibizumab was administered if the visual acuity letter score was less than 84 (approximate Snellen equivalent of 20/25 or worse) or the OCT CST was at or above the pre‐defined cut‐points. At the 4‐week and 8‐week visits, only ranibizumab injections were permitted. At 12 weeks and continuing through 20 weeks, retreatment was according to allocation group. A maximum of 2 injections of either dexamethasone or sham treatment were given in each eye. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome measure:

Secondary outcome measures:

Length of follow‐up: 6 months (24 weeks) |

|

| Notes |

Trial registration: NCT01945866 Source of funding: EY14231 (other grant/funding number: National Eye Institute), EY23207 (other grant/funding number: National Eye Institute), EY18817 (other grant/funding number: National Eye Institute) Declaration of interest: Several of the authors report receiving consultancy fees from the manufacturer of the implant, for example, quote "Dr Maturi reported receiving consultancy fees, research grants, payment for manuscript preparation, and travel, accommodations, and meeting expenses from Allergan, Inc" Date study conducted: February 2014 to December 2016 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote "Randomization was performed on the study website (http://www.drcr.net) using a permuted‐block design." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote "Randomization was performed on the study website (http://www.drcr.net) using a permuted‐block design." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote "Study participants and the medical monitor, who reviewed all adverse events, were masked to treatment group assignments. Refractionists, visual acuity testers, and OCT technicians were masked at the 24‐week primary outcome visit. Investigators and study coordinators were not masked." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote "Study participants and the medical monitor, who reviewed all adverse events, were masked to treatment group assignments. Refractionists, visual acuity testers, and OCT technicians were masked at the 24‐week primary outcome visit. Investigators and study coordinators were not masked." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | High follow‐up (127/129, 98%) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Almost all outcomes on clinical trials registry were reported. The exception "Percent of eyes with worsening or improvement of diabetic retinopathy on clinical exam [ Time Frame: 24 weeks after randomization ]" was not an outcome of this review. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Both eyes being eligible to allocation in a single individual poses the theoretical potential to influence outcomes in the fellow eye via systemic absorption. |

Lim 2012.

| Methods |

Study design: parallel group RCT Unit of randomisation: participants were randomly allocated to treatment. For participants with both eyes eligible on entry, the allocated randomised treatment was applied to the right eye, whereas the left eye received the other treatment. Number randomised: Total: 120 eyes, 110 participants, 10 people had both eyes enrolled Unit of analysis: individual eyes Number analysed: Total: 111 eyes There were 6 study eyes lost to follow‐up and 3 eyes declined to continue intervention Intervention arms: 36 eyes anti‐VEGF/steroid, 38 eyes anti‐VEGF, 37 eyes IVS There were 36 eyes per group required for an 80% power to detect a significance level of 5% in a two‐sided test of the outcome measures. |

|

| Participants |

Country: South Korea Mean age: 60 years Sex: 55 women; 50 men Underlying condition: DMO Inclusion criteria: eyes with clinically significant DMO based on ETDRS criteria. Macular oedema with CMT of at least 300 µm by optical coherence tomography Exclusion criteria: unstable medical status, previous treatment for DMO, history of vitreoretinal surgery, uncontrolled glaucoma; proliferative diabetic retinopathy with active neovascularisation, previous panretinal photocoagulation, presence of vitreomacular traction, history of systemic corticosteroids use in last 6 months |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention: Intravitreal bevacizumab (1.25mg/0.05ml) and intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide (2mg/0.05ml) Comparator 1: Intravitreal bevacizumab (1.25mg/0.05ml) Comparator 2: intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide (2mg/0.05ml) Bevacizumab was given as 2 injections at 6‐week intervals. During follow‐up, all three groups received repeated bevacizumab injections when CMT was greater than 300 μm on OCT at 6 week intervals. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Secondary outcome

Length of follow‐up: 1 year |

|

| Notes |

Trial registration: NCT01342159 Source of funding: not reported Declaration of interest: Quote "No conflicting relationship exists for any author." Date study conducted: March 2008 to February 2010 (start date was March 2009 on clinical trials.gov) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote "Randomization was performed using a random block permutation method according to a computer‐generated randomization list. Block lengths varied randomly" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote "The random allocation sequence was performed by a biostatistician. Details of the series were unknown to the investigators." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Authors do not state whether investigators or participants were masked to treatment allocation. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote "Visual acuity assessment and OCT were performed by an optometrist who was blinded to the group status of the patients." |