Abstract

In this issue, Griciuc et al investigate the Alzheimer’s disease risk gene, CD33. AD brains have increased CD33 and CD33-positive microglia. Mice lacking CD33 have less AD pathology suggesting a role of microglia for Aβ clearance and development of future therapies.

All symptomatic Alzheimer’s patients and one third of cognitively intact persons over age 65 have biomarker evidence of cerebral amyloidosis. One presumes, therefore, that stimulating amyloid clearance would help maximize the therapeutic reduction of neuropathology to prevent or arrest neurodegeneration and cognitive failure. Autosomal dominant familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD) is rare and is attributable to misprocessing of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) to generate excessive or mutant hyperaggregable Aβ42 which, in turn, serves as a “seed” for initiation of Aβ fibrillogenesis and oligomerization in the brain interstitium. Some Aβ assembly states are believed to be especially responsible for progression to neurofibrillary tangle formation and neurodegeneration. While research on potential AD treatments has focused on many important discoveries centered around mutations linked with FAD, in most people, no mutations exist that enable perfect prediction on an individual basis of those destined to develop more common sporadic forms of AD (for review, see Gandy and DeKosky, 2013).

Non-neuronal CNS cells such as microglia, the brain’s intrinsic phagocytes, are beginning to take center stage as we advance our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of common, late onset, “sporadic” AD. Several new papers, including one by Griciuc et al in this issue of Neuron, shift the focus of AD research to the (patho)physiological role of microglia in AD. Griciuc et al (2013) show that the microglial molecule CD33, an immunoglobulin-like cell surface protein, inhibits Aβ clearance in cell culture and in transgenic mouse brain. CD33 has been genetically linked to Alzheimer’s (Naj et al., 2011), instantly providing disease relevance to the molecule. Griciuc et al. (2013) also show that human AD brain tissue contains excess CD33, suggesting that dysregulation of CD33 plays a role in disease pathogenesis. This result may provide a molecular explanation for the Aβ-mediated dysfunction of microglia evidenced by the failure of microglia to reduce Aβ burden in a transgenic mouse model of AD (Krabbe et al, 2013), ultimately resulting in microglial senescence (Miller and Streit, 2007).

Wholesale ablation of microglia in AD transgenic mice (at least for a limited period of time) has no obvious effect on plaque burden, arguing against their critical importance in disease pathogenesis (Grathwohl et al, 2009). While this study was limited by the model-dependent inability to assess the consequences of microglia ablation on AD pathology for a prolonged period or to differentiate effects of various pathogenic Aβ species, Grathwohl et al. (2009) fuelled further investigations on the roles of microglia on AD pathology. Recent papers show that inhibition of interleukins 12 and 23 (vom Berg et al., 2012) or genetic deficiency of NALP3, a component of the inflammasome (Heneka et al., 2013) led to a substantial reduction of AD pathology illustrating how microglia take on multiple, distinct roles during the course of AD. Another recent discovery also links microglia to AD via the molecule CR1. Loss of CR1 modulates the impact of the apolipoprotein E ε4 (APOE ε4) allele on brain fibrillar amyloid burden and indicates that microglial dysfunction can be genetically linked to AD (Thambisetty et al., 2013). Surprisingly, those patients with a risky CR1 genotype and an APOE ε4 allele have an increased risk for Alzheimer’s, yet their fibrillar amyloid burden is reduced in comparison to the APOE ε4 subjects that lack the risky allele. Therefore, although the molecularexplanation for CR1-associated AD remains to be revealed, these studies suggest that microglia may be helpful or harmful, either alternately or even simultaneously. After migrating through the interstitial space of the brain to reach a nascent Aβ deposit, the balance between beneficial vs. harmful effects is unpredictable and may vary according to individual factors. The most straightforward model is that microglia are beneficial when they keep pace with Aβ aggregate accumulation. Once microglia are poisoned by Aβ, and/or once the Aβ deposit exceeds a size that would permit its engulfment by microglia, they may now facilitate or instigate neuronal dysfunction and disease progression, evolving from rescuer to murderer. This does not exclude the possibility that Aβ per se is also directly neurotoxic; the alternative pathways -- namely intrinsic Aβ neurotoxicity, indirect neurotoxicity of microglia in the presence of Aβ, and Aβ-driven microglial dysfunction -- are not mutually exclusive, but may rather act in concert to exacerbate AD pathology.

As a result of this revelation, it is clear that interference with microglial function could be beneficial, harmful, or both, depending on the timing and/or duration of intervention. Though inhibition or ablation of microglia at late stages of AD had no obvious effect on plaque burden (Grathwohl et al., 2009), the situation is quite different at early time points, when microglia appear to support both clearance of AD pathology and exacerbation of Aβ toxicity. This means that microglia-targeted therapies must be finely targeted, precisely timed, and carefully modulated at the molecular level. Existing drugs that could be aimed at increasing the phagocytic activity of microglia include the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) agonist pioglitazone and a novel selective PPARα/γ modulator, DSP-8658, (Yamanaka et al., 2012) as well as the mixed acetylcholinesterase inhibitor-nicotinic agonist galantamine (Takata et al. 2010), which is currently used in the symptomatic treatment of AD. Moreover, there is still much to learn about microglia when precisely assessing their roles during therapeutic manipulations such as Aβ immunotherapy. There will be equal interest in dissecting which effects are truly conferred by CNS resident microglia or by their myeloid counterparts entering the brain during the course of AD (an issue of intense debate in the field; e.g., Prinz et al., 2011). Considering the prospect of potential cell-based interventional approaches, these studies should result in exciting and crucial insights.

CD33 now joins this new class of microglia-related molecules for possible evaluation in human clinical trials. Griciuc et al. (2013) establish the benefit of genetic CD33 deficiency. The assessment of drugs that safely reduce CD33 levels (e.g., anti-CD33 antibodies) is the obvious next goal. Along this line, the success reported by vom Berg et al (2012) takes us beyond genetic deletion and on to a concrete example of immunotherapeutic inhibition of IL-12/23, providing proof-of-principle evidence that relevant microglial pathways can indeed be viable therapeutic targets.

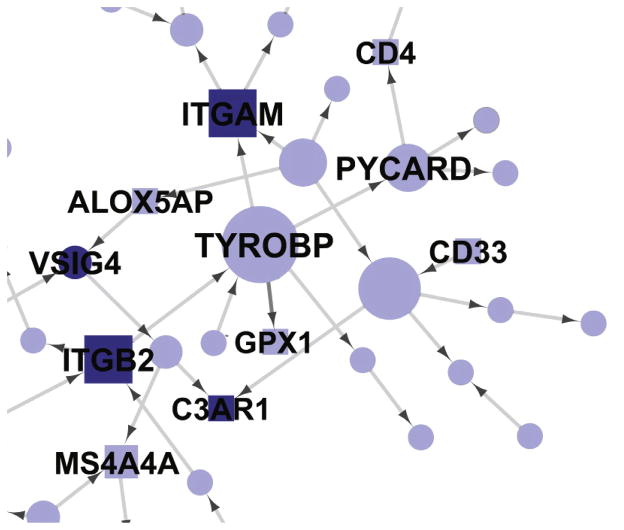

Two other recent papers link a known microglial Aβ clearing molecule, TREM2, to Alzheimer’s disease (Guerreiro et al., 2013; Jonsson et al., 2013). Rounding out this collection of new and emerging AD/microglia publications is a fascinating and unconventional “multiscale” genetics study that implicates an AD link for TYROBP, a microglial molecule linked to both TREM2 and CD33 (Zhang et al., 2013). Thus, the first Alzheimer’s network is born, and, unlike autosomal dominant FAD, the focus of this network is on microglia (Figure 1), not on Aβ speciation or generation.

Figure 1.

A Subnetwork of Complement System Molecules from a Bayesian Brain Immune and Microglia Module Contains CD33 and TYROBP. This module correlates with multiple late-onset AD clinical covariates and is enriched for immune functions and pathways related to microglia activity. The complement network is derived from multiscale analysis of genetic linkage information and AD brain gene expression information. The subnetwork shown here is derived from a subgroup of genes related to complement. MHC, Fc, cytokine, and toll-like receptor networks are also part of the module but are not shown. Core family members are shaded darkly, whereas square nodes denote literature-supported nodes (at least two PubMed abstracts implicating the gene or final protein complex in LOAD or a model of LOAD). Labeled nodes are either highly connected in the original network, literature-implicated LOAD genes, or core members of one of the five immune families. Node size is proportional to connectivity in the module (from Zhang et al., 2013, with permission).

The implications of this explosion of AD/microglia papers are profound. First, the longstanding questions about whether microglia are important in AD and in Aβ clearance would appear to be put to rest. Second, we have new potential therapeutic opportunities for small molecule discovery, among the first candidate targets for small molecules that might be employed to accelerate Aβ clearance. Third, these AD/microglia studies describe molecules that define a new Alzheimer’s network as well as the pathways that are contained therein. Zhang, Schadt, and their colleagues have suggested that such pathways and networks as linked entities might constitute complex drug “mega-targets” and that superior AD drugs might result from a search for drugs that correct entire networks or subnetworks by acting on their hubs or “drivers” (Zhang et al., 2013). Lastly, the novel multiscale analysis of Zhang et al. (2013), heretofore untested in AD, has been instantly validated by virtue of its inclusion of two microglial genes, CD33 and TREM2, linked to AD by more conventional genetic approaches. Undoubtedly, this eruption of AD/microglial genes will stimulate new interest in these cells and pathways. “The more, the merrier” always applies in the case of drug targets, and this CD33-TREM2-TYROBP network and its component pathways as well as IL-12/23 signaling molecules, represent true groundbreaking progress. The pathways defined by these molecules are the first clues based on human disease genetics since the cloning of presenilin 1 in 1995, and the first clues ever to emerge solely from studies of common forms of late onset, sporadic AD. The implication is that Zhang et al. (2013) may point the way to new drug discovery efforts in AD as has already been true in peripheral inflammatory diseases. A new iteration of multiscale analysis focusing on early stage AD is underway, as is whole exome sequencing of the DNA from 50 patients with common, late onset, sporadic AD. One would predict that, in both of these gene hunts, microglial molecules – mere bit players just 6 months ago – may emerge as marquee stars in the pathogenesis of AD wherein they serve as essential, dynamic, and Janus-like components of the amyloid hypothesis.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

SG is a member of a DMSB for a Pfizer/J&J Alzheimer Immunotherapy Alliance clinical trial and a member of the SAB of Cerora. Within the past 5 yrs, SG has held research grants from Amicus Therapeutics and from Baxter Pharmaceuticals. FLH has nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gandy S, DeKosky ST. Toward the treatment and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: rational strategies and recent progress. Annu Rev Med. 2013;64:367–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-092611-084441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grathwohl SA, Kälin RE, Bolmont T, Prokop S, Winkelmann G, Kaeser SA, Odenthal J, Radde R, Eldh T, Gandy S, et al. Formation and maintenance of Alzheimer’s disease beta-amyloid plaques in the absence of microglia. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1361–1363. doi: 10.1038/nn.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griciuc A, Serrano-Pozo A, Parrado AR, Lesinski AN, Asselin CN, Mullin K, Hooli B, Choi SH, Hyman BT, Tanzi RE. Alzheimer’s disease risk gene CD33 inhibits microglial uptake of amyloid beta. Neuron. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.014. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, Carrasquillo M, Rogaeva E, Majounie E, Cruchaga C, Sassi C, Kauwe JS, Younkin S, et al. Alzheimer Genetic Analysis Group. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:117–127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heneka MT, Kummer MP, Stutz A, Delekate A, Schwartz S, Vieira-Saecker A, Griep A, Axt D, Remus A, Tzeng TC, et al. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature. 2013;493:674–678. doi: 10.1038/nature11729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jonsson T, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, Jonsdottir I, Jonsson PV, Snaedal J, Bjornsson S, Huttenlocher J, Levey AI, Lah JJ, et al. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:107–116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krabbe G, Halle A, Matyash V, Rinnenthal JL, Eom GD, Bernhardt U, Miller KR, Prokop S, Kettenmann H, Heppner FL. Functional impairment of microglia coincides with beta-amyloid deposition in mice with Alzheimer-like pathology. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller KR, Streit WJ. The effects of aging, injury and disease on microglial function: a case for cellular senescence. Neuron Glia Biol. 2007;3:245–253. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X08000136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naj AC, Jun G, Beecham GW, Wang LS, Vardarajan BN, Buros J, Gallins PJ, Buxbaum JD, Jarvik GP, Crane PK, et al. Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:436–441. doi: 10.1038/ng.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prinz M, Priller J, Sisodia SS, Ransohoff RM. Heterogeneity of CNS myeloid cells and their roles in neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1227–1235. doi: 10.1038/nn.2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takata K, Kitamura Y, Saeki M, Terada M, Kagitani S, Kitamura R, Fujikawa Y, Maelicke A, Tomimoto H, Taniguchi T, et al. Galantamine-induced amyloid-{beta} clearance mediated via stimulation of microglial nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40180–40191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.142356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thambisetty M, An Y, Nalls M, Sojkova J, Swaminathan S, Zhou Y, Singleton AB, Wong DF, Ferrucci L, Saykin AJ, Resnick SM. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Effect of complement CR1 on brain amyloid burden during aging and its modification by APOE genotype. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.vom Berg J, Prokop S, Miller KR, Obst J, Kälin RE, Lopategui-Cabezas I, Wegner A, Mair F, Schipke CG, Peters O, et al. Inhibition of IL-12/IL-23 signaling reduces Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology and cognitive decline. Nat Med. 2012;18:1812–1819. doi: 10.1038/nm.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamanaka M, Ishikawa T, Griep A, Axt D, Kummer MP, Heneka MT. PPARγ/RXRα-induced and CD36-mediated microglial amyloid-β phagocytosis results in cognitive improvement in amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 mice. J Neurosci. 2012;32:17321–17331. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1569-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang B, Gaiteri C, Bodea LG, Wang Z, McElwee J, Podtelezhnikov AA, Zhang C, Xie T, Tran L, Dobrin R, et al. Integrated systems approach identifies genetic nodes and networks in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2013;153:707–720. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]