Abstract

Background

The effects of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and thyroid hormones on the development of human papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) remain poorly understood.

Methods

The study population consisted of 741 (341 women, 300 men) histologically confirmed PTC cases and 741 matched controls with pre-diagnostic serum samples stored in the Department of Defense Serum Repository. Concentrations of TSH, total T3 (TT3), total T4 (TT4), and free T4 (FT4) were measured in serum samples. Conditional logistic regression models were used to calculate ORs and 95% CIs.

Results

The median time between blood draw and PTC diagnosis was 1,454 days. Compared to the middle tertile of TSH levels within the normal range, serum TSH levels below the normal range were associated with an elevated risk of PTC among women (OR=3.74, 95% CI: 1.53, 9.19) but not men. TSH levels above the normal range were associated with an increased risk of PTC among men (OR=1.96, 95% CI: 1.04, 3.66) but not women. The risk of PTC decreased with increasing TSH levels within the normal range among both men and women (Ptrend=0.0005 and 0.041, respectively).

Conclusions

We found a significantly increased risk of PTC associated with TSH levels below the normal range among women and with TSH levels above the normal range among men. An inverse association between PTC and TSH levels within the normal range was observed among both men and women.

Impact

These results could have significant clinical implications for physicians who are managing patients with abnormal thyroid functions and those with thyroidectomy.

Keywords: thyroid-stimulating hormone, TSH, thyroid hormone, papillary thyroid cancer

Introduction

Thyroid cancer has the highest prevalence of all endocrine malignancies, and its incidence is rising faster than any other malignancy in both men and women (1). In the United States, thyroid cancer is the 9th most common cancer, accounting for 3.8% of all malignancies and 0.3% of all deaths from cancer (2). The most common histological type of thyroid cancer is papillary thyroid cancer (PTC), which accounts for more than 80% of all thyroid carcinomas (3). The causal factors underlying thyroid cancer are poorly understood. The most well-established risk factors for thyroid cancer include increased age, female gender, exposure to ionizing radiation, history of benign thyroid disease, and a family history of thyroid cancer (4–7). Recent studies have identified higher body weight and height as risk factors for thyroid cancer (8, 9).

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is the major growth factor for thyroid cells and regulator of thyroid functions. It controls the processes that lead to increased thyroid hormone production and secretion (10). Blood concentrations of thyroid hormones (i.e., triiodothyronine [T3] and its prohormone thyroxine [T4]) inversely regulate the release of TSH through a negative feedback loop at the pituitary levels. High TSH levels have been associated with PTC pathogenesis in a mouse model (11). Suppression of TSH is currently recommended to manage differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) patients, which has shown benefits to patient survival (12). Thyroid hormones have also been suggested to have a tumor promoting effect on several cancers, including pancreatic, breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer (13). However, findings of epidemiological studies linking TSH and thyroid hormones to the risk of thyroid cancer have been inconsistent (14–40).

The majority of early studies reported an increased risk of thyroid cancer associated with elevated TSH levels (14–30), several studies found no significant association (31–39), and one reported a reduced risk (40). All studies that reported a positive association between TSH and thyroid cancer were cross-sectional (14–29) or case-control studies (30). Therefore, the possibility of reverse causation or treatment effect could be of potential concern because the TSH levels were measured after diagnosis. There are only three previous prospective cohort studies. One reported a significantly reduced risk of thyroid cancer associated with elevated TSH levels (40). Two smaller studies reported lower, but not significant TSH levels in thyroid cancer cases than in controls (38, 39). The relationship between thyroid hormones and risk of thyroid cancer has also been inconclusive (14–17, 37, 38, 40). Two studies found lower thyroid hormone levels were associated with a higher risk of thyroid cancer (16, 17), while the remaining five reported no association (14, 15, 37, 38, 40).

In light of the inconclusive associations between TSH, thyroid hormones, and thyroid cancer, we conducted a nested case-control study using data from the Department of Defense (DoD) Automated Central Tumor Registry (ACTUR) and the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), with pre-diagnostic serum samples from the Department of Defense Serum Repository (DoDSR) to investigate the associations of PTC with TSH and thyroid hormones (total T3 [TT3], total T4 [TT4], and free T4 [FT4]).

Materials and Methods

Study population

Our study population was US military personnel who had serum samples stored in the DoDSR (41). These stored samples were leftover sera collected for the routine HIV test of military personnel. The DoDSR is maintained by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, US Army Public Health Command. As of August 2013, the repository stored more than 55 million serum samples from over 10 million individuals, most of whom were active-duty and reserve personnel. Serum samples on all military members were typically drawn at the time of service entry and, on average, every 2 years thereafter for mandatory HIV testing (42, 43).

We designed an individually matched nested case-control study. Cases were identified by linkage of the ACTUR with the DoDSR database. The ACTUR was established in 1986 and is the data collection and clinical tracking system for cancer cases diagnosed and treated at military treatment facilities among DoD beneficiaries, including active-duty military personnel, retired military personnel, and their dependents. The registry includes information on demographic variables, diagnostic factors, and tumor characteristics (44). Cases met the following criteria: 1) histologically confirmed with International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3 for thyroid gland: C739) histology codes 8021, 8050, 8052, 8130, 8260, 8290, 8330–8332, 8335, 8340–8346, 8450, 8452, and 8510; 2) at least 1.5ml pre-diagnostic and 0.5ml post-diagnostic serum samples stored in the DoDSR; 3) diagnosis between 2000 and 2013; and 4) aged 21 years or older at diagnosis. Cases with any prior cancers (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) recorded in the ACTUR at the date of diagnosis of thyroid cancer were excluded from the study. A total of 800 eligible cases were identified. The histology of all reported thyroid cancer cases was abstracted from ACTUR. Of these eligible cases, 742 (92.8%) were PTC (ICD-O-3: 8050, 8260, and 8340–8343). IDs for all cases were sent from ACTUR to Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center via encrypted methods. Those IDs were excluded from the eligible pool of controls. Controls’ eligibility criteria were: having at least four serum samples in DoDSR, and according to the matching criteria, the midpoint of those four samples within one year of the control’s matched case’s midpoint of their four samples. Controls were randomly selected with replacement from the cohort of service members who were not diagnosed with any cancer (with the exception of non-melanoma skin cancer), as per query of the ACTUR. Controls were matched one-to-one to cases by date of birth (±1 year), gender, race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic, and other), average date of the selected four samples drawn (±1 year), and component at diagnosis/matching. Demographic and military characteristics for all cases and controls were abstracted from DMSS. The DMSS now serves as the central repository of medical surveillance data for the US armed forces and contains longitudinal records which have been continuously updated since 1990. The system includes demographic and military characteristics as well as military and medical experiences of service members throughout their military careers (41). All study procedures were approved by the Uniformed Services University Institutional Review Board, the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, the DoD Joint Pathology Center, and The Human Investigation Committee of Yale University.

Measurement of TSH and thyroid hormones

A calibrated Roche Cobas e601 analyzer was used to measure the serum concentrations of TSH and thyroid hormones using the manufacturer’s reagents and calibrators. TSH was captured between two monoclonal antibodies (one was biotinylated, the other labeled with a ruthenium complex) which specific for sterically non-interfering epitopes of human TSH. TT3 and TT4 were dissociated from binding proteins using 8-anilino-1-naphthalene sulfonic acid (ANS) and competed with the exogenous biotinylated-T3 or -T4 for binding to a T3- or T4-specific antibody labeled with a ruthenium complex. FT4 directly competed with the exogenous biotinylated-T4 for binding to a T4-specific antibody labeled with a ruthenium complex. All the antibodies were captured by streptavidin-coated magnetic microparticles, which were then magnetically captured by an electrode and the application of voltage induced emission of photons by the ruthenium complex. The intensities of the luminescence were inversely proportional to the serum concentrations of TSH and thyroid hormones. The normal ranges for serum concentrations of TSH, TT3, TT4, and FT4 were 0.3–4.2 μU/ml, 79–149 ng/dl, 5.0–10.6 μg/dl, and 0.80–1.80 ng/dl, respectively. All control samples were tested in the same batch as their matched case samples. Based on results obtained from quality-control samples (5%), intra-batch coefficient of variation ranged from 3.9% to 7.7%.

Statistical analyses

Measurements of TSH and thyroid hormones failed in one serum sample, leaving 741 pairs of PTC cases and matched controls included in the final analysis. The distributions of demographic and military characteristics between cases and controls were compared by chi-square tests. The correlations between TSH, TT3, TT4, and FT4 were estimated using the Pearson correlation coefficients. Given the individual-matched case-control design, conditional logistic regression analyses were employed to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the association between TSH, thyroid hormones and PTC. Serum concentrations of TSH, TT3, TT4, and FT4 were divided into three categories based on the normal range (below, within, and above the normal range). The normal range group was further categorized into tertiles based on the distributions of serum concentrations among controls. Thus, there were five categories for each hormone: below the normal range, lower, medium, and higher levels within the normal range, and above the normal range. The middle tertile within the normal range was used as reference category for all analyses. All the conditional logistic regression models were adjusted for body mass index (BMI) (<18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25–29.9, and ≥30 kg/m2) and branch of military service (army, air force, marines and coast guard, and navy). TT3, TT4, and FT4 models were also adjusted for serum concentrations of TSH. However, additional adjustment for serum concentrations of TT3, TT4, and FT4 in TSH models did not result in material changes in the observed associations and thus were not included in the final models. Dose-response relationship was further investigated using P for trend, estimated by treating serum concentrations of TSH and thyroid hormones as continuous variables. Stratified analyses were performed by gender, histological subtype (classical PTC [ICD-O-3: 8050, 8260, 8341–8343] and follicular variant of PTC [ICD-O-3: 8340]), tumor size (≤10 and >10 mm), and years between serum samples drawn and PTC diagnosis (<3 years, 3–6 years, and >6 years, based on sample size). Sensitivity analysis was also conducted among women aged <50 years old to see if estrogen impacts the associations among premenopausal women. All tests were two-sided with α=0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

PTC cases were more likely to have served in the Army or Air Force at time of diagnosis, while controls were more likely to have served in the Navy, Marines, or Coast Guard (Table 1). Cases had a slightly larger BMI compared to controls, but the difference was not statistically significant. Since the cases were individually matched to controls based on age, gender, and race/ethnicity, the distributions of these variables were similar between cases and controls.

Table 1.

Distributions of selected characteristics among PTC cases and matched controls.

| Cases (n=741) |

Controls (n=741) |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | ||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||||

| <30 | 210 | 28.3 | 203 | 27.4 | |

| 30–39 | 309 | 41.7 | 322 | 43.5 | |

| 40–49 | 185 | 25.0 | 179 | 24.2 | |

| ⩾50 | 37 | 5.0 | 37 | 5.0 | 0.92 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 400 | 54.0 | 400 | 54.0 | |

| Female | 341 | 46.0 | 341 | 46.0 | 1.00 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 467 | 63.0 | 466 | 62.9 | |

| Black | 131 | 17.7 | 132 | 17.8 | |

| Hispanic | 68 | 9.2 | 68 | 9.2 | |

| Other | 55 | 7.4 | 55 | 7.4 | |

| Unknown | 20 | 2.7 | 20 | 2.7 | 1.00 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| <25 | 256 | 34.6 | 285 | 38.5 | |

| 25–29.9 | 148 | 20.0 | 129 | 17.4 | |

| ⩾30 | 16 | 2.2 | 10 | 1.4 | |

| Missing | 321 | 43.3 | 317 | 42.8 | 0.23 |

| Service | |||||

| Army | 299 | 40.4 | 253 | 34.1 | |

| Air Force | 193 | 26.1 | 150 | 20.2 | |

| Marines and Coast Guard combined | 64 | 8.6 | 91 | 12.3 | |

| Navy | 185 | 25.0 | 247 | 33.3 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviation: PTC, Papillary Thyroid Cancer; BMI, Body Mass Index.

All serum samples were drawn between 83 and 4,232 days before the cases were diagnosed with PTC. As anticipated, there were statistically significant strong positive correlations between TT3, TT4, and FT4 (r=0.68 for TT3 and TT4, p<0.0001; r=0.40 for TT3 and FT4, p<0.0001; and r=0.52 for TT4 and FT4, p<0.0001, respectively). TSH was weakly, but statistically significantly correlated with TT3, TT4, and FT4 (r=−0.06 for TSH and TT3, p=0.022; r=−0.17 for TSH and TT4, p<0.0001; and r=−0.19 for TSH and FT4, p<0.0001, respectively). Female cases had lower mean TSH levels as compared to their matched controls, while male cases had higher mean TSH levels as compared to their matched controls. None of these differences were statistically significant. We also observed non-significantly higher mean levels of thyroid hormones among female cases as compared to female controls, but thyroid hormone levels were similar between cases and controls among men.

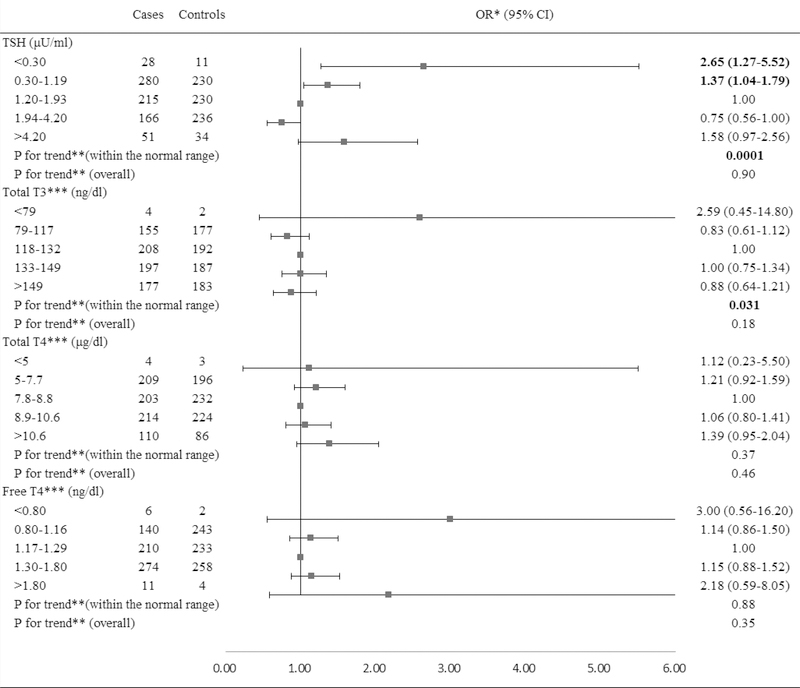

In the overall population, serum TSH levels below the normal range were associated with a significantly increased risk of PTC (OR=2.65, 95% CI: 1.27, 5.52, Figure 1) compared to the middle tertile of the normal range. Paradoxically, TSH levels above the normal range were also associated with an increased risk of PTC (OR=1.58, 95% CI: 0.97, 2.56) with borderline significance. Serum concentrations of TT3, TT4, and FT4 below or above the normal range were not significantly related to an elevated risk of PTC. Within the normal ranges, the risk of PTC decreased with increasing TSH levels (Ptrend=0.0001) and with decreasing TT3 levels (Ptrend=0.031), but no dose-response relationships were observed for TT4 and FT4.

Figure 1.

Risk of PTC associated with serum concentrations of TSH and thyroid hormones.

Abbreviation: PTC: Papillary Thyroid Cancer; TSH: Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone; BMI: Body Mass Index.

*Conditional logistic regression, adjusted for BMI and branch of military service.

**Estimated by continuous variables.

***Additionally adjusted for serum concentration of TSH.

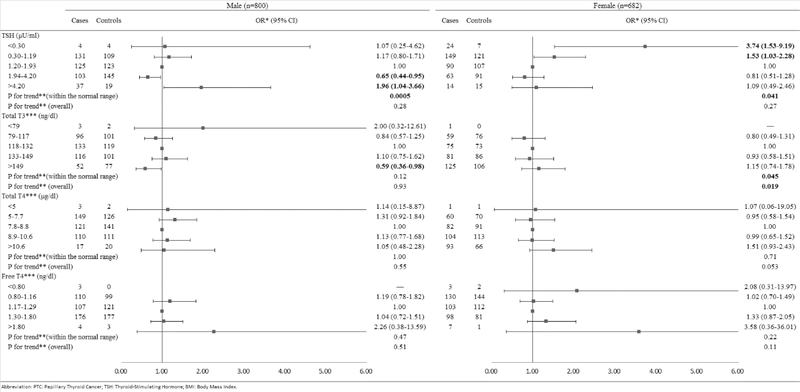

TSH levels below the normal range were associated with increased risk of PTC among women (OR=3.74, 95% CI: 1.53, 9.19) but not among men (OR=1.07, 95% CI: 0.25, 4.62, Figure 2) compared to the middle tertile of the normal range. Additionally, an increased risk of PTC in relation to TSH levels above the normal range was observed only among men (OR=1.96, 95% CI: 1.04, 3.66) but not among women (OR=1.09, 95% CI: 0.49, 2.46). The risk of PTC decreased with increasing TSH levels within the normal range among both men and women (Ptrend=0.0005 and 0.041, respectively). However, lower TSH levels within the normal range were associated with an increased risk of PTC and the association was stronger in women (OR=1.53, 95% CI: 1.03, 2.28) than in men (OR=1.17, 95% CI: 0.80, 1.71). In contrast, higher TSH levels within the normal range were associated with a reduced risk of PTC among men (OR=0.65, 95% CI: 0.44, 0.95). An inverse association between TT3 levels above the normal range and risk of PTC was observed only among men (OR=0.59, 95% CI: 0.36, 0.98); while the risk of PTC increased with increasing serum concentrations of TT3 among women (overall Ptrend=0.019). No significant associations with TT4 and FT4 were observed.

Figure 2.

Risk of PTC associated with serum concentrations of TSH and thyroid hormones, stratified by gender.

Abbreviation: PTC: Papillary Thyroid Cancer; TSH: Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone; BMI: Body Mass Index.

*Conditional logistic regression, adjusted for BMI and branch of military service.

**Estimated by continuous variables.

***Additionally adjusted for serum concentration of TSH.

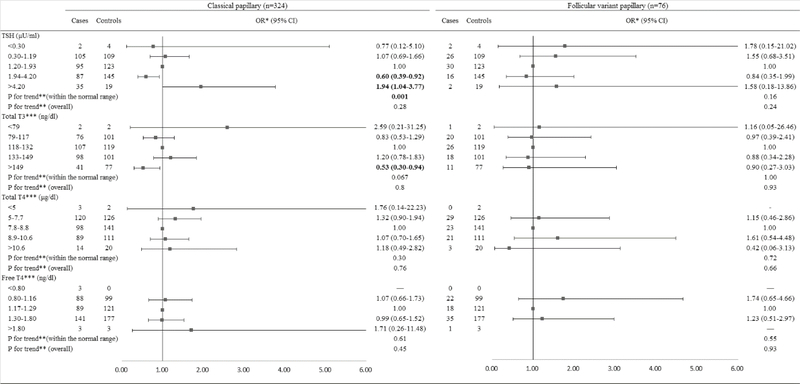

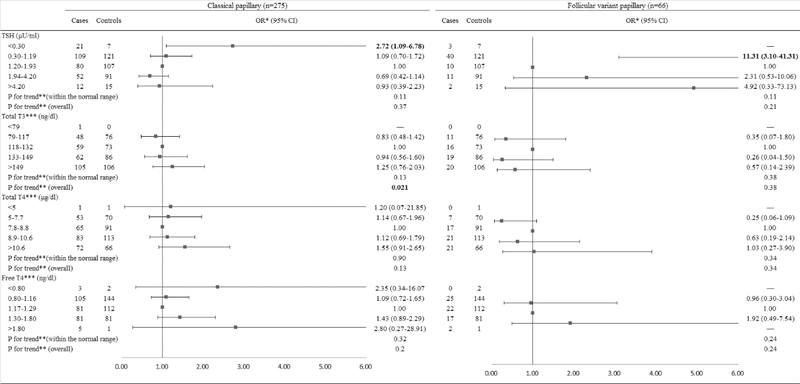

When the analyses were stratified by histological subtype among men (Figure 3), TSH levels above the normal range were borderline significantly associated with an increased risk of classical PTC (OR=1.94, 95% CI: 1.00, 3.77). A significantly inverse dose-response relationship was observed between TSH levels within the normal range and risk of classical PTC (Ptrend=0.0010) but not follicular variant PTC (Ptrend=0.16). TT3 levels above the normal range were significantly associated with a decreased risk of classical PTC (OR=0.53, 95% CI: 0.30, 0.94). When the analyses were stratified by histological subtype among women (Figure 4), TSH levels below the normal range were associated with a significantly increased risk of classical PTC (OR=2.72, 95% CI: 1.09, 6.78). The lower TSH levels within the normal range were associated with an elevated risk of follicular variant of PTC (OR=11.31, 95% CI: 3.10, 41.31). There was an increasing trend in risk of classical PTC with increasing TT3 levels (Ptrend=0.021), but no statistically significant association between TT3 levels and risk of follicular variant of PTC was observed.

Figure 3.

Risk of PTC associated with serum concentrations of TSH and thyroid hormones among males, stratified by histological subtypes.

Abbreviation: PTC: Papillary Thyroid Cancer; TSH: Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone; BMI: Body Mass Index.

*Conditional logistic regression, adjusted for BMI and branch of military service.

**Estimated by continuous variables.

***Additionally adjusted for serum concentration of TSH.

Figure 4.

Risk of PTC associated with serum concentrations of TSH and thyroid hormones among females, stratified by histological subtypes.

Abbreviation: PTC: Papillary Thyroid Cancer; TSH: Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone; BMI: Body Mass Index.

*Conditional logistic regression, adjusted for BMI and branch of military service.

**Estimated by continuous variables.

***Additionally adjusted for serum concentration of TSH.

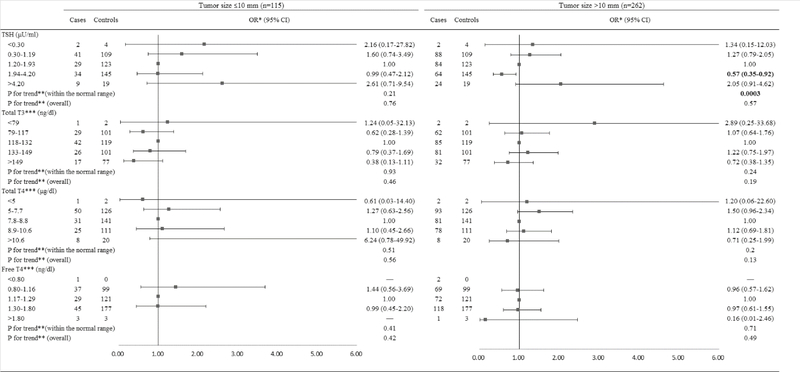

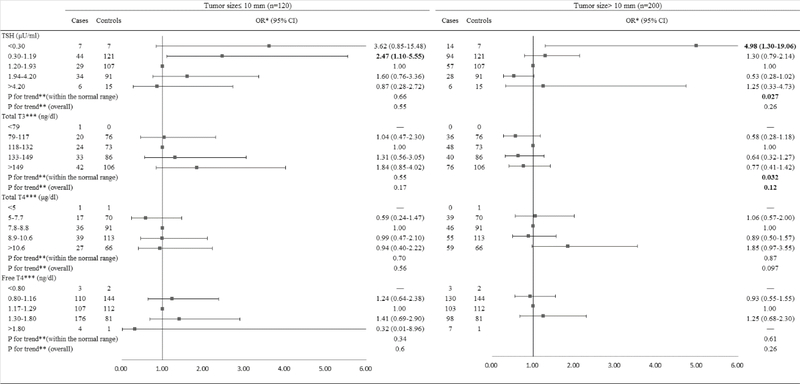

When the analyses were stratified by tumor size among men (Figure 5), the higher TSH levels within the normal range were associated with a reduced risk of PTC with tumor size greater than 10 mm (OR=0.57, 95% CI: 0.35, 0.92) but not PTC microcarcinoma (≤10 mm) (OR=0.99, 95% CI: 0.47, 2.12). TSH levels within the normal range were inversely associated with PTC >10 mm (Ptrend=0.0003), whereas, there was no trend for PTC microcarcinoma (Ptrend=0.21). When the analyses were stratified by tumor size among women (Figure 6), TSH levels below the normal range were associated with a significantly increased risk of PTC >10 mm (OR=4.98, 95% CI: 1.30, 19.06) and a non-significantly elevated risk of PTC microcarcinoma (OR=3.62, 95% CI: 0.85, 15.48). The lower TSH levels within the normal range were associated with an elevated risk of PTC microcarcinoma (OR=2.47, 95% CI: 1.10, 5.55) but not PTC >10 mm (OR=1.30, 95% CI: 0.79, 2.14). TSH levels within the normal range were inversely associated with PTC >10 mm (Ptrend=0.027). No significant associations were found for TT3, TT4, and FT4 for both PTC microcarcinoma and PTC >10 mm among men and women.

Figure 5.

Risk of PTC associated with serum concentrations of TSH and thyroid hormones among males, stratified by tumor size.

Abbreviation: PTC: Papillary Thyroid Cancer; TSH: Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone; BMI: Body Mass Index.

*Conditional logistic regression, adjusted for BMI and branch of military service.

**Estimated by continuous variables.

***Additionally adjusted for serum concentration of TSH.

Figure 6.

Risk of PTC associated with serum concentrations of TSH and thyroid hormones among females, stratified by tumor size.

Abbreviation: PTC: Papillary Thyroid Cancer; TSH: Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone; BMI: Body Mass Index.

*Conditional logistic regression, adjusted for BMI and branch of military service.

**Estimated by continuous variables.

***Additionally adjusted for serum concentration of TSH.

Further stratified analyses were conducted by the years between serum samples drawn and PTC diagnosis (Supplementary Table 1). No clear pattern was observed with timing of the serum samples drawn, though numbers of cases were small after stratification.

Sensitivity analyses showed that the associations between risk of PTC and serum concentrations of TSH, TT3, TT4, and FT4 did not change materially after restricting the analyses to women aged <50 years old.

Discussion

In this large case-control study based on pre-diagnostic serum measures and with sufficient power to stratify by gender, we found that serum TSH levels below the normal range were associated with an elevated risk of PTC among women but not men. TSH levels above the normal range were only associated with an increased risk of PTC among men. There was an inverse association between PTC and TSH levels within the normal range among both men and women. The observed associations varied somewhat by histological subtypes (classical vs. follicular variant PTCs) and by tumor size (≤10mm vs. >10mm) among men and women. The gender effect on the association between TSH and PTC was only observed among classical PTC cases. TSH levels showed a stronger association with PTC with larger tumor size. A suggestive inverse association between higher TT3 levels and risk of PTC was observed among men.

The inverse trends between TSH levels and risk of PTC observed in the present study was in accordance with results from a nested case-control study within a large population-based prospective cohort in Europe (40). The cohort consisted of approximately 520,000 healthy individuals aged 35 to 69 years when recruited between 1992 and 1998 in 10 European countries. A total of 357 incident thyroid cancer cases (57 men and 300 women) diagnosed during 1992 to 2009 and 767 matched controls were included in the analyses. Blood samples were collected at enrollment. This European study found an inverse dose-response relationship between overall TSH levels and risk of differentiated thyroid cancer. The years between sample collection and thyroid cancer diagnosis were similar between the European study and our study. However, as compared to the European study, our population was younger and healthier (45), with participants aged 17 to 56 years at blood samples collection. Additionally, our study had a larger number of the male cases than the European study, which provides sufficient power to examine the associations among men. The present study observed inconsistent associations between TSH levels and risk of PTC among women as compared to men, while the European study reported similar associations among men and women. There were another two prospective studies with smaller sample size that investigated the association between TSH and risk of thyroid cancer (38, 39). Although no significantly inverse association was observed in these studies, both reported lower TSH levels among thyroid cancer cases as compared to controls.

A previous meta-analysis showed that higher TSH levels were associated with an increased thyroid cancer risk (46). However, all 22 studies included in the meta-analysis were cross-sectional studies and measured TSH levels after treatment of thyroid cancer began. The cross-sectional design could not clarify whether elevated TSH levels preceded thyroid cancer diagnosis or were effects of treatment. The low levels of thyroid hormones due to dysfunction of the thyroid gland among thyroid cancer patients could cause the pituitary gland to release more TSH. Additionally, higher TSH levels may promote the growth of already initiated thyroid cancer, making the cancer larger and more easily diagnosed. Therefore, the positive association seen in the cross-sectional studies could be due to ascertainment bias (10). On the other hand, controls in these studies were always patients with thyroid nodules or patients undergoing surgical treatment for a suspicious thyroid tumor. Some nodules can produce high levels of thyroid hormones, thus lowering TSH levels (40). Many thyroid cancer patients also had additional benign thyroid nodules, and the mutual influence between those nodules and TSH concentrations has not yet been determined (18).

TSH plays an important role in regulating thyroid function, including increasing number, size, and secretory activity of thyrocytes, increasing thyroid blood flow, and increasing thyroid hormone production and secretion from follicular thyroid cells (10). Classical TSH actions are mainly mediated through the Gαs-adenylyl cyclase-protein kinase A-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) pathway, which is associated with production of thyroid hormones and proliferation of thyroid epithelial cells (47). However, somatic mutations in thyroid epithelial cell can also activate the cAMP pathway, which facilitate the cell growth and clonal expansion, leading to the formation of an autonomously functioning thyroid adenoma. The adenoma can synthesize and secrete thyroid hormones autonomously, thereby suppressing TSH secretion (48). Therefore, constitutive activation of the cAMP pathway could be associated with an increased carcinogenic potential and a decreased TSH level. Due to the deprivation of TSH stimulation, the extra-nodular tissue would become quiescent. Depending on the iodine intake, growth potential, and other factors, it may take months to a decade or longer for an adenoma to grow large enough to cause hyperthyroidism (49).

While the underlying mechanism of lower TSH levels increasing the risk of PTC is currently unclear, two genome-wide association studies have found that five common variants (rs965513[A] on 9q22.23, rs944289[T] and rs116909374[T] on 14q13.3, rs966423[C] on 2q35, and rs2439302[G] on 8p12) were associated with both an increased risk of thyroid cancer and low TSH level (50, 51). According to Gudmundsson et al., the five variants could refer to genes FOXE1, NKX2–1, DIRC3, and NRG1. The FOXE1 gene can regulate the transcription of thyroglobulin and thyroperoxidase genes, and together with the NKX2–1 gene, plays an essential role in thyroid gland formation, differentiation, and function (52). Although the function of the DIRC3 gene is unknown, it is presumed to have tumor suppressor activity (53). The gene NRG1 encodes a signaling protein which mediates cell-cell interactions and plays a critical role in the growth and development of thyroid gland. The carriers of these five variants may be characterized by lower concentrations of TSH. The consequence of the lower TSH levels may be result in less differentiation of the thyroid epithelium, causing a higher predisposition to malignant cell transformation (51).

The present study observed positive associations in a dose-response manner between serum concentrations of TT3 and risk of PTC only among women. The observed inverse association between TSH levels and risk of PTC among women still held after excluding those ≥50 years old. These findings suggest that women may be more sensitive to the effect of TSH and thyroid hormones as compared to men. Possible explanations including effect modification of estrogen and different exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals (e.g., birth control pills and personal care products) by gender that need to be explored in future studies.

The present study also noted different associations of TSH and thyroid hormones on risk of PTC by histological subtype and tumor size. Lower TSH levels showed an association with increasing risk of the follicular variant of PTC and PTC >10mm, while higher TSH levels were associated with a decreased risk of classical PTC and PTC microcarcinoma. These associations may support the hypothesis that follicular variant of PTC and papillary microcarcinoma are unique clinical entities with different etiologic profiles (54, 55).

Additionally, the present study failed to find a clear pattern between TSH levels and risk of PTC with timing of the serum samples drawn. The relevant time window in which TSH exerts influence on development of thyroid cancer needs to be further studied.

The present study has several strengths. It included a relatively large number of male cases, providing sufficient statistical power to investigate and compare the associations by gender, which is important because women are much more likely to develop thyroid cancer than men. The study population was comprised entirely of US active duty military personnel, minimizing the potential differences in effects of TSH and thyroid hormones among healthy people and people with high risk of thyroid cancer. Potential selection bias from difference in access to medical care was also minimized for our study population. The serum concentrations of TSH and thyroid hormones were prospectively assessed and were not influenced by the disease process or treatment, which provided an opportunity to estimate potentially causal relationships between TSH, thyroid hormones, and thyroid cancer. A limitation of this study is that there was a lack of information on several potential confounding factors, such as ionizing radiation exposure, history of benign thyroid disease, family history of thyroid cancer, and smoking status. There were also a high percentage of participants with missing BMI data, which may have led to insufficient adjustment for BMI. The lack of data on medication use preclude us from carrying out sensitivity analyses excluding people who were taking thyroid hormones. Furthermore, the subgroup analyses, which were stratified by years between samples collection and diagnosis, histological subtype, and tumor size, may have yielded unstable results due to the small subgroup counts.

In conclusion, the present study showed a significantly increased risk of PTC associated with TSH levels lower than the normal range among women and higher than the normal range among men. The observed associations varied by histological subtype and tumor size. These results could have significant clinical implications for physicians who are managing patients with abnormal thyroid functions and those with thyroidectomy. Future studies are warranted to further understand these associations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the authors(s) and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences or the Department of Defense.

Source of funding: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01ES020361 (Y. Zhang and J. Rusiecki) and American Cancer Society (ACS) grant RSGM-10-038-01-CCE (Y. Zhang).

Abbreviations list

- TSH

thyroid-stimulating hormone

- PTC

papillary thyroid cancer

- TT3

total T3

- TT4

total T4

- FT4

free T4

- DTC

differentiated thyroid cancer

- DoD

Department of Defense

- ACTUR

Automated Central Tumor Registry

- DMSS

Defense Medical Surveillance System

- DoDSR

Department of Defense Serum Repository

- ICD-O

International Classification of Diseases for Oncology

- ANS

8-anilino-1-naphthalene sulfonic acid

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

References

- 1.Chen AY, Jemal A, Ward EM. Increasing incidence of differentiated thyroid cancer in the United States, 1988–2005. Cancer. 2009;115(16):3801–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2011, National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meza R, Chang JT. Multistage carcinogenesis and the incidence of thyroid cancer in the US by sex, race, stage and histology. BMC public health. 2015;15(1):789. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2108-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wartofsky L Increasing world incidence of thyroid cancer: increased detection or higher radiation exposure? Hormones (Athens). 2010;9(2):103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imaizumi M, Usa T, Tominaga T, et al. Radiation dose-response relationships for thyroid nodules and autoimmune thyroid diseases in Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb survivors 55–58 years after radiation exposure. Jama. 2006;295(9):1011–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preston-Martin S, Franceschi S, Ron E, Negri E. Thyroid cancer pooled analysis from 14 case-control studies: what have we learned? Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2003;14(8):787–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iribarren C, Haselkorn T, Tekawa IS, Friedman GD. Cohort study of thyroid cancer in a San Francisco Bay area population. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2001;93(5):745–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitahara CM, Platz EA, Freeman LEB, et al. Obesity and Thyroid Cancer Risk among US Men and Women: A Pooled Analysis of Five Prospective Studies. Cancer Epidem Biomar. 2011;20(3):464–72. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rinaldi S, Lise M, Clavel-Chapelon F, et al. Body size and risk of differentiated thyroid carcinomas: findings from the EPIC study. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2012;131(6):E1004–14. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLeod DS. Thyrotropin in the development and management of differentiated thyroid cancer. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America. 2014;43(2):367–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2014.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franco AT, Malaguarnera R, Refetoff S, et al. Thyrotrophin receptor signaling dependence of Braf-induced thyroid tumor initiation in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(4):1615–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015557108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonklaas J, Sarlis NJ, Litofsky D, et al. Outcomes of patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma following initial therapy. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2006;16(12):1229–42. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moeller LC, Fuhrer D. Thyroid hormone, thyroid hormone receptors, and cancer: a clinical perspective. Endocr-Relat Cancer. 2013;20(2):R19–R29. doi: 10.1530/Erc-12-0219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye ZQ, Gu DN, Hu HY, Zhou YL, Hu XQ, Zhang XH. Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, microcalcification and raised thyrotropin levels within normal range are associated with thyroid cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11. doi:Artn 56 10.1186/1477-7819-11-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon SS, Lee YS, Lee IK, Kim JG. Serum thyrotropin as a risk factor for thyroid malignancy in euthyroid subjects with thyroid micronodule. Head Neck-J Sci Spec. 2012;34(7):949–52. doi: 10.1002/hed.21828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gul K, Ozdemir D, Dirikoc A, et al. Are endogenously lower serum thyroid hormones new predictors for thyroid malignancy in addition to higher serum thyrotropin? Endocrine. 2010;37(2):253–60. doi: 10.1007/s12020-010-9316-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jonklaas J, Nsouli-Maktabi H, Soldin SJ. Endogenous thyrotropin and triiodothyronine concentrations in individuals with thyroid cancer. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2008;18(9):943–52. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zafon C, Obiols G, Mesa J. Preoperative TSH level and risk of thyroid cancer in patients with nodular thyroid disease: nodule size contribution. Endocrinologia y nutricion : organo de la Sociedad Espanola de Endocrinologia y Nutricion. 2015;62(1):24–8. doi: 10.1016/j.endonu.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimny M, Selkinski I, Blasius S, Rink T, Schroth HJ, Grunwald F. Risk of malignancy in follicular thyroid neoplasm: predictive value of thyrotropin. Nuklearmedizin. Nuclear medicine. 2012;51(4):119–24. doi: 10.3413/Nukmed-0456-12-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiu HK, Sanda S, Fechner PY, Pihoker C. Correlation of TSH with the risk of paediatric thyroid carcinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77(2):316–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04383.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorange A, Triau S, Mucci-Hennekinne S, et al. An elevated level of TSH might be predictive of differentiated thyroid cancer. Ann Endocrinol-Paris. 2011;72(6):513–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2011.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haymart MR, Repplinger DJ, Leverson GE, et al. Higher serum thyroid stimulating hormone level in thyroid nodule patients is associated with greater risks of differentiated thyroid cancer and advanced tumor stage. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2008;93(3):809–14. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiore E, Rago T, Provenzale MA, et al. L-thyroxine-treated patients with nodular goiter have lower serum TSH and lower frequency of papillary thyroid cancer: results of a cross-sectional study on 27 914 patients. Endocr-Relat Cancer. 2010;17(1):231–9. doi: 10.1677/Erc-09-0251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zafon C, Obiols G, Baena JA, Castellvi J, Dalama B, Mesa J. Preoperative thyrotropin serum concentrations gradually increase from benign thyroid nodules to papillary thyroid microcarcinomas then to papillary thyroid cancers of larger size. Journal of thyroid research. 2012;2012:530721. doi: 10.1155/2012/530721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi L, Li Y, Guan H, Li C, Shan Z, Teng W. Usefulness of serum thyrotropin for risk prediction of differentiated thyroid cancers does not apply to microcarcinomas: results of 1,870 Chinese patients with thyroid nodules. Endocrine journal. 2012;59(11):973–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin J, Machekano R, McHenry CR. The utility of preoperative serum thyroid-stimulating hormone level for predicting malignant nodular thyroid disease. Am J Surg. 2010;199(3):294–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim ES, Lim DJ, Baek KH, et al. Thyroglobulin Antibody Is Associated with Increased Cancer Risk in Thyroid Nodules. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2010;20(8):885–91. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nixon IJ, Ganly I, Hann LE, et al. Nomogram for predicting malignancy in thyroid nodules using clinical, biochemical, ultrasonographic, and cytologic features. Surgery. 2010;148(6):1120–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boelaert K, Horacek J, Holder RL, Watkinson JC, Sheppard MC, Franklyn JA. Serum thyrotropin concentration as a novel predictor of malignancy in thyroid nodules investigated by fine-needle aspiration. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2006;91(11):4295–301. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim HK, Yoon JH, Kim SJ, Cho JS, Kweon SS, Kang HC. Higher TSH level is a risk factor for differentiated thyroid cancer. Clin Endocrinol. 2013;78(3):472–7. doi: 10.1111/cen.12027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerschpacher M, Gobl C, Anderwald C, Gessl A, Krebs M. Thyrotropin Serum Concentrations in Patients with Papillary Thyroid Microcancers. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2010;20(4):389–92. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim KW, Park YJ, Kim EH, et al. Elevated Risk of Papillary Thyroid Cancer in Korean Patients with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. Head Neck-J Sci Spec. 2011;33(5):691–5. doi: 10.1002/hed.21518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petric R, Perhavec A, Gazic B, Besic N. Preoperative serum thyroglobulin concentration is an independent predictive factor of malignancy in follicular neoplasms of the thyroid gland. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105(4):351–6. doi: 10.1002/jso.22030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polyzos SA, Kita M, Efstathiadou Z, et al. Serum thyrotropin concentration as a biochemical predictor of thyroid malignancy in patients presenting with thyroid nodules. J Cancer Res Clin. 2008;134(9):953–60. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0373-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azizi G, Malchoff CD. Autoimmune Thyroid Disease: A Risk Factor for Thyroid Cancer. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(2):201–9. doi: 10.4158/Ep10123.Or [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castro MR, Espiritu RP, Bahn RS, et al. Predictors of Malignancy in Patients with Cytologically Suspicious Thyroid Nodules. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2011;21(11):1191–8. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maia FFR, Matos PS, Silva BP, et al. Role of ultrasound, clinical and scintigraphyc parameters to predict malignancy in thyroid nodule. Head Neck Oncol. 2011;3. doi:Artn 17 10.1186/1758-3284-3-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hrafnkelsson J, Tulinius H, Kjeld M, Sigvaldason H, Jonasson JG. Serum thyroglobulin as a risk factor for thyroid carcinoma. Acta Oncol. 2000;39(8):973–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thoresen SO, Myking O, Glattre E, Rootwelt K, Andersen A, Foss OP. Serum Thyroglobulin as a Preclinical Tumor-Marker in Subgroups of Thyroid-Cancer. Brit J Cancer. 1988;57(1):105–8. doi:Doi 10.1038/Bjc.1988.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rinaldi S, Plummer M, Biessy C, et al. Thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroglobulin, and thyroid hormones and risk of differentiated thyroid carcinoma: the EPIC study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2014;106(6):dju097. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubertone MV, Brundage JF. The Defense Medical Surveillance System and the Department of Defense serum repository: Glimpses of the future of public health surveillance. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(12):1900–4. doi:Doi 10.2105/Ajph.92.12.1900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGlynn KA, Quraishi SM, Graubard BI, Weber JP, Rubertone MV, Erickson RL. Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Risk of Testicular Germ Cell Tumors. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):1901–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perdue CL, Cost AA, Rubertone MV, Lindler LE, Ludwig SL. Description and utilization of the United States department of defense serum repository: a review of published studies, 1985–2012. PloS one. 2015;10(2):e0114857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enewold L, Zhou J, McGlynn KA, et al. Racial Variation in Tumor Stage at Diagnosis Among Department of Defense Beneficiaries. Cancer. 2012;118(5):1397–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bollinger MJ, Schmidt S, Pugh JA, Parsons HM, Copeland LA, Pugh MJ. Erosion of the healthy soldier effect in veterans of US military service in Iraq and Afghanistan. Population health metrics. 2015;13:8. doi: 10.1186/s12963-015-0040-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLeod DSA, Watters KF, Carpenter AD, Ladenson PW, Cooper DS, Ding EL. Thyrotropin and Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2012;97(8):2682–92. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kimura T, Van Keymeulen A, Golstein J, Fusco A, Dumont JE, Roger PP. Regulation of thyroid cell proliferation by TSH and other factors: A critical evaluation of in vitro models. Endocr Rev. 2001;22(5):631–56. doi:Doi 10.1210/Er.22.5.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paschke R, Ludgate M. The thyrotropin receptor in thyroid diseases. The New England journal of medicine. 1997;337(23):1675–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712043372307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sandrock D, Olbricht T, Emrich D, Benker G, Reinwein D. Long-term follow-up in patients with autonomous thyroid adenoma. Acta endocrinologica. 1993;128(1):51–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Gudbjartsson DF, et al. Common variants on 9q22.33 and 14q13.3 predispose to thyroid cancer in European populations. Nat Genet. 2009;41(4):460–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Gudbjartsson DF, et al. Discovery of common variants associated with low TSH levels and thyroid cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2012;44(3):319–U126. doi: 10.1038/ng.1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhuang Y, Wu W, Liu H, Shen W. Common genetic variants on FOXE1 contributes to thyroid cancer susceptibility: evidence based on 16 studies. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2014;35(6):6159–66. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1896-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kohler A, Chen B, Gemignani F, et al. Genome-wide association study on differentiated thyroid cancer. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98(10):E1674–81. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu XM, Schneider DF, Leverson G, Chen H, Sippel RS. Follicular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma is a Unique Clinical Entity: A Population-Based Study of 10,740 Cases. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2013;23(10):1263–8. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Y, Chen Y, Huang H, et al. Diagnostic radiography exposure increases the risk for thyroid microcarcinoma: a population-based case-control study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24(5):439–46. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.