Abstract

Background

Chronic peripheral joint pain due to osteoarthritis (OA) is extremely prevalent and a major cause of physical dysfunction and psychosocial distress. Exercise is recommended to reduce joint pain and improve physical function, but the effect of exercise on psychosocial function (health beliefs, depression, anxiety and quality of life) in this population is unknown.

Objectives

To improve our understanding of the complex inter‐relationship between pain, psychosocial effects, physical function and exercise.

Search methods

Review authors searched 23 clinical, public health, psychology and social care databases and 25 other relevant resources including trials registers up to March 2016. We checked reference lists of included studies for relevant studies. We contacted key experts about unpublished studies.

Selection criteria

To be included in the quantitative synthesis, studies had to be randomised controlled trials of land‐ or water‐based exercise programmes compared with a control group consisting of no treatment or non‐exercise intervention (such as medication, patient education) that measured either pain or function and at least one psychosocial outcome (self‐efficacy, depression, anxiety, quality of life). Participants had to be aged 45 years or older, with a clinical diagnosis of OA (as defined by the study) or self‐reported chronic hip or knee (or both) pain (defined as more than six months' duration).

To be included in the qualitative synthesis, studies had to have reported people's opinions and experiences of exercise‐based programmes (e.g. their views, understanding, experiences and beliefs about the utility of exercise in the management of chronic pain/OA).

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodology recommended by Cochrane for the quantitative analysis. For the qualitative analysis, we extracted verbatim quotes from study participants and synthesised studies of patients' views using framework synthesis. We then conducted an integrative review, synthesising the quantitative and qualitative data together.

Main results

Twenty‐one trials (2372 participants) met the inclusion criteria for quantitative synthesis. There were large variations in the exercise programme's content, mode of delivery, frequency and duration, participant's symptoms, duration of symptoms, outcomes measured, methodological quality and reporting. Comparator groups were varied and included normal care; education; and attention controls such as home visits, sham gel and wait list controls. Risk of bias was high in one and unclear risk in five studies regarding the randomisation process, high for 11 studies regarding allocation concealment, high for all 21 studies regarding blinding, and high for three studies and unclear for five studies regarding attrition. Studies did not provide information on adverse effects.

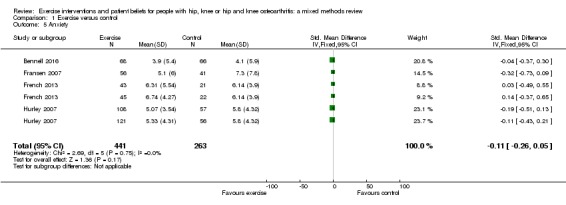

There was moderate quality evidence that exercise reduced pain by an absolute percent reduction of 6% (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐9% to ‐4%, (9 studies, 1058 participants), equivalent to reducing (improving) pain by 1.25 points from 6.5 to 5.3 on a 0 to 20 scale and moderate quality evidence that exercise improved physical function by an absolute percent of 5.6% (95% CI ‐7.6% to 2.0%; standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.27, 95% CI ‐0.37 to ‐0.17, equivalent to reducing (improving) WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) function on a 0 to 100 scale from 49.9 to 44.3) (13 studies, 1599 participants)). Self‐efficacy was increased by an absolute percent of 1.66% (95% CI 1.08% to 2.20%), although evidence was low quality (SMD 0.46, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.58, equivalent to improving the ExBeliefs score on a 17 to 85 scale from 64.3 to 65.4), with small benefits for depression from moderate quality evidence indicating an absolute percent reduction of 2.4% (95% CI ‐0.47% to 0.5%) (SMD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.29 to ‐0.02, equivalent to improving depression measured using HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) on a 0 to 21 scale from 3.5 to 3.0) but no clinically or statistically significant effect on anxiety (SMD ‐0.11, 95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.05, 2% absolute improvement, 95% CI ‐5% to 1% equivalent to improving HADS anxiety on a 0 to 21 scale from 5.8 to 5.4; moderate quality evidence). Five studies measured the effect of exercise on health‐related quality of life using the 36‐item Short Form (SF‐36) with statistically significant benefits for social function, increasing it by an absolute percent of 7.9% (95% CI 4.1% to 11.6%), equivalent to increasing SF‐36 social function on a 0 to 100 scale from 73.6 to 81.5, although the evidence was low quality. Evidence was downgraded due to heterogeneity of measures, limitations with blinding and lack of detail regarding interventions. For 20/21 studies, there was a high risk of bias with blinding as participants self‐reported and were not blinded to their participation in an exercise intervention.

Twelve studies (with 6 to 29 participants) met inclusion criteria for qualitative synthesis. Their methodological rigour and quality was generally good. From the patients' perspectives, ways to improve the delivery of exercise interventions included: provide better information and advice about the safety and value of exercise; provide exercise tailored to individual's preferences, abilities and needs; challenge inappropriate health beliefs and provide better support.

An integrative review, which compared the findings from quantitative trials with low risk of bias and the implications derived from the high‐quality studies in the qualitative synthesis, confirmed the importance of these implications.

Authors' conclusions

Chronic hip and knee pain affects all domains of people's lives. People's beliefs about chronic pain shape their attitudes and behaviours about how to manage their pain. People are confused about the cause of their pain, and bewildered by its variability and randomness. Without adequate information and advice from healthcare professionals, people do not know what they should and should not do, and, as a consequence, avoid activity for fear of causing harm. Participation in exercise programmes may slightly improve physical function, depression and pain. It may slightly improve self‐efficacy and social function, although there is probably little or no difference in anxiety. Providing reassurance and clear advice about the value of exercise in controlling symptoms, and opportunities to participate in exercise programmes that people regard as enjoyable and relevant, may encourage greater exercise participation, which brings a range of health benefits to a large population of people.

Keywords: Humans; Middle Aged; Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice; Anxiety; Anxiety/rehabilitation; Arthralgia; Arthralgia/rehabilitation; Chronic Pain; Chronic Pain/psychology; Chronic Pain/rehabilitation; Depression; Depression/rehabilitation; Exercise Therapy; Exercise Therapy/psychology; Osteoarthritis, Hip; Osteoarthritis, Hip/psychology; Osteoarthritis, Hip/rehabilitation; Osteoarthritis, Knee; Osteoarthritis, Knee/psychology; Osteoarthritis, Knee/rehabilitation; Qualitative Research; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Self Efficacy; Social Participation; Symptom Assessment

The health benefits of exercise for people with chronic hip and knee pain from osteoarthritis

Researchers conducted a review of the effect of exercise on physical, emotional and mental health for people with long lasting (chronic) knee or hip joint pain from osteoarthritis. The studies examined were from Europe, North America, Asia and Australasia, and included clinical settings, home exercise and sessions at leisure facilities. Studies included men and woman aged 45 years and over.

What is chronic joint pain and what is exercise?

Chronic knee and hip pain from osteoarthritis (breakdown of the bone and cartilage, causing pain and stiffness) is a common cause of physical disability, anxiety, depression, poor quality of life and social problems (such as feeling a burden). Exercise is recommended to reduce pain and disability, and improves people's health beliefs, depression, anxiety and quality of life. We wanted to improve understanding of the relationships between pain, movement ability, psychological issues such as depression and anxiety, how chronic pain affects social relationships, and exercise.

What happens to people with chronic knee or hip pain who take part in exercise programmes?

A search of medical databases up to March 2016 found 21 studies with 2372 people which considered pain, movement or both alongside psychological and social outcomes when people with pain and stiffness in their knee, hip, or both took part in exercise. Participation in exercise programmes probably slightly improves pain, physical function, depression, and ability to connect with others, and little or no difference in anxiety. It may improve belief in one's own abilities, and social function.

The studies confirmed that:

‐ people who exercised rated their pain to be 1.2 points lower on a scale of 0 to 20 after about 45 weeks (score: 5.3 with exercise compared with 6.5 with no exercise (control), an improvement of 6%).

‐ physical function improved by about 5% over 41 weeks (exercise group improved by 5.6 points on a scale of 0 to 100 (44.3 with exercise compared with 49.9 with control)).

‐ people's confidence in what they could do increased by 2% after 35 weeks (exercise group improved by 1.1 points on a scale of 17 to 85 (65.4 with exercise compared with 64.3 with control)).

‐ people who exercised were 2% less depressed, or half a point on a scale of 0 to 21, after 35 weeks (3.0 points with exercise compared with 3.5 with control).

‐ exercise made people feel less anxious about themselves by 2%, a 0.4 drop on a 0 to 21 scale, after 24 weeks (5.4 points with exercise compared with 5.8 with control).

‐ exercise resulted in social interaction improving by 7.9 points over 36 weeks on a scale of 0 to 100, giving a change of 8% (81.5 with exercise compared with 73.6 with control).

The quality of the evidence was generally moderate, but low for confidence in ability, mental health and social function. This is mainly due to varied measures, making comparison more difficult, and because people taking part knew they were exercising so may have been influenced by expectations of improvement. The studies did not report side effects. Studies lasted for different durations, so we do not know if changes occurred quickly and were maintained, or whether improvements were gradual throughout the studies. Some studies took measurements later after the programme than others.

Additionally, 12 studies investigated people's opinions, beliefs and experiences of exercise, and whether exercise changed these. The quality of evidence was high overall. Initially people were confused about the characteristics of their pain, which shaped their feelings, behaviours and decisions about relieving pain. People thought movement and exercise was good for joints, but movement caused pain and they worried this might cause them harm. Lack of information from medical professionals meant people avoided physical activity and exercise for fear of causing damage.

Overall, people who had taken part in exercise programmes had positive experiences, helping increase their beliefs that exercise could improve pain, physical and mental health, and general quality of life.

Providing reassurance and exercise advice, challenging poor health beliefs, and providing enjoyable exercise programmes may encourage participation and benefit the health of many people.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Physical and psychosocial outcomes in people with hip, knee or hip and knee osteoarthritis

| Physical and psychosocial outcomes in people with hip, knee or hip and knee osteoarthritis | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with chronic hip, knee or hip and knee osteoarthritis Settings: outpatient and community Intervention: exercise Comparison: varied: included normal care, education, attention controls such as home visits, sham gel and wait list controls | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Exercise | |||||

| Pain. WOMAC normalised to 0‐20 pain scale based on largest study reporting the 0‐20 scale (Hurley 2007). Lower score indicated less pain. Mean duration of follow‐up: 45 weeks (range: 12 weeks to 30 months). | The mean WOMAC pain score was 6.5. | The mean pain in the intervention groups was 1.25 points lower (1.8 to 0.8 lower) | ‐ | 1058 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | 6% absolute pain reduction (95% CI ‐9% to ‐4%). 19% relative pain reduction (95% CI ‐27% to ‐11%). SMD ‐0.33 (95% CI ‐0.46 to ‐0.21). |

| Physical function. WOMAC function scales normalised to 0‐100. Lower score indicated improved physical function. Mean duration of follow‐up: 41 weeks (range: 9 weeks to 30 months). | The mean WOMAC function was 49.9. | The mean function in the intervention groups was 5.6 points lower (7.6 to 2.0 lower) | ‐ | 1599 (13 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 |

5.6% absolute function improvement (95% CI ‐7.6% to 2%). 11.2% relative function improvement (95% CI ‐15.2% to ‐4%). SMD ‐0.27 (95% CI ‐0.37 to ‐0.17). |

| Self‐efficacy. Self‐efficacy scores transformed to exercise beliefs score with score range from 17 to 85. Higher score indicated greater self‐efficacy. Mean duration of follow‐up: 35 weeks (range: 12 weeks to 18 months). | The mean self‐efficacy was 64.3. | The mean self‐efficacy in the intervention groups was 1.13 points higher (0.74 to 1.51 higher) | ‐ | 1138 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low3 | 1.66% absolute increase in self‐efficacy (95% CI 1.08% to 2.20%). 1.76% relative increase (95% CI 1.14% to 2.23%). SMD 0.46 (95% CI 0.34 to 0.58). |

| Depression. Depression scores were transformed to the HADS depression scale with score range of 0‐21. Lower score indicated less depression. Mean duration of follow‐up: 35 weeks (range: 8 weeks to 30 months). | The mean depression was 3.5. | The mean depression in the intervention groups was 0.5 points lower (1.0 to 0.1 lower). | ‐ | 919 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate4 | 2.4% absolute reduction in depression (95% CI ‐4.7% to ‐0.5%). The relative reduction was 14.3% (95% CI ‐2.8% to ‐28%). SMD ‐0.16 (95% CI‐0.29 to ‐0.02). |

| Anxiety. HADS scale of 0‐21. Lower score indicated lower anxiety levels. Mean duration of follow‐up: 24 weeks (range: 9 weeks to 12 months). | The mean anxiety was 5.8. | The mean anxiety in the intervention groups was 0.4 points lower (1.0 lower to 0.2 higher). | ‐ | 704 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate5 | 2% absolute improvement in anxiety (95% CI ‐5% to 1%). The relative change was 6.9% (95% CI ‐17.2% to 3.4%). SMD ‐0.11 (95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.05). |

| SF‐36 social function. Domain of SF‐36 considered representative of quality of life: mental health domain largely covered by depression and anxiety above: scale of 0‐100. Higher score indicated improved social function. Mean duration of follow‐up: 36 weeks (range: 8 weeks to 18 months). | The mean social function was 73.6. | The mean SF‐36 social function in the intervention groups was 7.9 (4.1 to 11.6 higher). | ‐ | 576 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low6 | 7.9% absolute improvement in social function (95% CI 4.1% to 11.6%). The relative improvement was 8.8% (95% CI 2.7% to 13.9%). |

| Adverse effects of treatment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Studies did not provide information on adverse events. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SF‐36: 36‐item Short Form Survey; SMD: standardised mean difference; WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Pain downgraded one level due to high risk of bias for blinding of participants.

2Function downgraded one level due to high risk of bias for blinding of participants.

3Self‐efficacy downgraded two levels; one level due to moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 47%) probably due to different measures of self‐efficacy being used in each study, and one level due to high risk of blinding bias.

4Depression downgraded one level due to high risk of blinding bias.

5Anxiety downgraded one level due to high risk of blinding bias. 6SF‐36 social domain downgraded two levels due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 75%) and reduced confidence in the estimate of effect when the outlier Aglamis 2008 was included, and high risk of blinding bias.

Background

Description of the condition

Severe peripheral joint pain, often labelled as osteoarthritis (OA), is extremely prevalent worldwide (Bedson 2004; Woolf 2003), and a major cause of disability and healthcare expenditure (Gupta 2005; Leardini 2004; March 1997; Vos 2012). In the UK, nearly 20% of people aged over 50 years have severe disabling knee or hip pain (Jinks 2004; Peat 2001), also labelled as OA (Bedson 2004), which slowly worsens over time, compromising quality of life and independence (Dawson 2005). The economic burden of joint pain/OA is significant (Gupta 2005). Annually 15% of people aged over 50 years consult their general practitioners (GP) for knee pain (Jinks 2004). Estimated figures for 2010 indicated that OA totalled GBP16.8 billion in direct (formal medical care) and indirect (lost working days, informal care) costs (Arthritis Research UK 2017). The personal experiencing and psycho‐socioeconomic consequences of chronic joint pain will increase as people live longer, adopt sedentary lifestyles and obesity rises (Underwood 2004). By 2020, OA is projected to be the fourth leading cause of disability across the world (Woolf 2003).

Description of the intervention

Exercise is recommended to reduce joint pain and improve physical function (Fransen 2015; NICE 2008; Zhang 2008). In addition, successful completion of a challenging exercise programme can highlight to people their capabilities; challenge inappropriate health beliefs; disrupt detrimental behaviour (fear‐avoidance); and teach people that exercise is a safe, beneficial, and active coping strategy they can use to improve self‐efficacy (confidence in one's ability to perform a specific health behaviour or task) and self‐reliance, and reduce helplessness and disability (Hurley 2010; Keefe 1996a; Penninx 2002). Unfortunately, as there is no summary of the evidence describing the reciprocity between pain, physical and psychosocial function and the utility of exercise on addressing these problems, the importance of these inter‐relationships remains underappreciated, and potential treatment options underutilised.

Information and advice about the role of exercise in the management of joint pain form part of most self‐management (Miles 2011; Newman 2004) and physiotherapy programmes (Walsh 2009). The aim is to effect behavioural change, that is, encourage people to exercise regularly, but the most effective way to deliver exercise advice that will bring about this behavioural change and get people exercising regularly is unclear (Hurley 2009). Didactic programmes, explaining the benefits of exercise for joint pain management using verbal or written information, may enlighten people, but they do not detail how to start exercising, what (not) to do, when, how or how much, and fail to convince people who have experienced many years of activity‐related pain that moderate‐intensity exercise will not aggravate their condition (Larmer 2014a). Consequently, didactic programmes may have limited ability to improve health beliefs, self‐confidence, self‐efficacy, coping and affect behavioural change. To people with joint pain, exercise remains a burdensome, time‐consuming, effortful concept that causes pain.

Programmes that include a participatory exercise component may encourage regular exercise more effectively (Griffiths 2007). On these programmes, participants gain first‐hand experience of what exercises to do; how to do them; that exercise is not harmful; and how exercise can be used to reduce pain; and this improves their physical function, health beliefs, anxiety, depression and potentially their general quality of life (Hurley 2007; Hurley 2010). Again, without a systematic review of the evidence on the effectiveness of exercise education delivery, the best way to bring about participation in regular exercise is unclear; wasting time, effort and resources, and potentially missing effective treatment options.

It is important to consider a range of different exercise interventions: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend muscle strengthening in the area affected, and aerobic exercise, with stretching and manipulation, is also advocated, particularly for hip OA (NICE 2014). Interventions to consider might therefore be land‐based or water‐based, and may focus on a single aspect of fitness such as strength training, aerobic exercise or balance, for example, or a combination of these. A programme may be delivered to groups or one‐to‐one, and may be carried out at a specialised facility or at home, in classes or individually, and frequency and intensity demanded may vary from one study to another.

How the intervention might work

Conceptual framework

Relationship between chronic pain, physical function and psychosocial function

Chronic joint pain and disability are the most common symptoms of OA, and attract the most attention. Because OA and joint pain are often regarded as the benign, untreatable, inevitable consequences of ageing, the psychosocial sequelae (anxiety, depression, health beliefs, behaviours, quality of life, participation and dependency) are often underestimated by healthcare professionals and lay people. However, this overlooks the complex, reciprocal relationship between pain, physical functioning and psychosocial functioning where each affects and is affected by the others (Hurley 2003; Figure 1). For example, chronic joint pain is bewildering and distressing because it has no obvious cause, increases insidiously and is unaccountably episodic. People's reactions to pain are highly variable and influenced by the beliefs, meanings and explanations they attach to it.

Figure 1.

Complex reciprocal inter‐relationship between pain, physical and psychosocial function and exercise (Hurley 2003: permission for reproduction provided by the publishers, Wolters Kluwer).

Relationship between health beliefs and psychosocial outcomes

Beliefs about the cause, prognosis and effectiveness of treatment are key determinants of illness behaviour and response to treatment (Main 2002; Turk 1996). People commonly believe joint pain is the inevitable, incurable consequence of ageing, caused or exacerbated by activity, evoking feelings of helplessness, anxiety, depression and "fear‐avoidance" behaviour (Figure 2), when people avoid physical activity for fear of causing additional pain and damage (Keefe 1996a). However, avoiding activity results in greater muscle weakness, joint instability and stiffness, exacerbated pain, disability and dependency (Dekker 1992). Challenging these erroneous health beliefs is vital for successful pain management. Inappropriate health beliefs and behaviours can be altered by positive experiences that show people how active coping strategies such as exercise can reduce pain and improve physical functioning, self‐efficacy, anxiety, helplessness, catastrophising and depression (Keefe 1996b; Main 2002; Turk 1996). Appreciating the complex inter‐relationship between clinical symptoms and psychosocial effects of joint pain could provide additional strategies for better joint pain management.

Figure 2.

Effect of erroneous health beliefs (Hurley 2003: permission for reproduction provided by the publishers, Wolters Kluwer).

Better appreciation of the complex reciprocal relationship between pain, psychosocial effects and physical functioning would help us understand better the consequences of joint pain, identify the most effective ways of teaching the value of exercise, and develop more efficient models of care for people experiencing chronic joint pain. This is best achieved by a systematic review of the relevant literature to establish what interventions are most effective, and to quantify the size of the treatment effect produced. However, the complex reciprocity between joint pain, psychosocial impact, physical functioning and exercise will be influenced by many factors that are difficult to measure as they depend on nebulous, labile, personal beliefs, experiences, emotions, preferences and prejudices. A systematic review asking questions on effectiveness and synthesising outcome evaluations only would miss important facets and cannot accommodate information from qualitative studies better placed to assess pain, the psychosocial effects of pain and the benefits of exercise. These are best captured using methods that synthesise quantitative (systematic reviews) with qualitative studies of people's views and experiences (Lorenc 2008; Oliver 2008; Rees 2006; Thomas 2004). Appreciating the views, beliefs, experiences and preferences of target populations for an intervention provides greater insight into how an intervention achieves its effects, why it may not be as effective as anticipated and may expose gaps in our understanding. This enables us to adapt existing, or develop new, healthcare interventions that best address people's needs (Harden 2004; Oliver 2008; Rees 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

This review focused on exercise‐based rehabilitation programmes, defined as programmes that had an active participatory exercise component (for management of OA and the psychosocial variables affected by the condition). Establishing the effect of exercise‐based rehabilitation programmes on the psychosocial impact of chronic joint pain will increase our understanding about how and why these interventions are effective and identify the effective elements of exercise programmes.

To meet the aims, the review will answer the following questions.

What are the effects of exercise‐based rehabilitation programmes on physical and psychosocial functioning for people with chronic knee or hip (or both) pain?

What are people's experiences, opinions and preferences regarding exercise‐based rehabilitation programmes and the advice they receive about exercise?

What implications can be drawn from the qualitative synthesis of people's views to inform the appropriateness and acceptability of exercise‐based rehabilitation programmes for people living with OA?

Objectives

Overarching objective

To improve our understanding of the complex inter‐relationship between pain, psychosocial effects, physical function and exercise.

Specific aims and objectives

To systematically review the evidence on the impact of physical exercise on people's pain, physical and psychosocial functioning including:

identifying the most effective formats for delivering exercise advice;

explaining why some exercise interventions may be more effective than others;

recommending exercise formats and content by constructing a "toolbox" that describes the most effective exercise interventions for healthcare providers and patients to use.

These was achieved by conducting:

a synthesis of quantitative data on the benefits and harm of exercise interventions for improving pain, physical functioning and psychosocial functioning;

a synthesis of qualitative data on participant's experiences, opinions and preferences of physical exercise;

a synthesis integrating the quantitative and qualitative data (an integrative review) to assess the extent to which existing evaluated interventions address the needs and concerns of people living with OA.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

To be included in the review, quantitative clinical trials of exercise programmes had to have used individual or cluster randomised allocation. Qualitative studies reporting the views and opinions of participants of exercise‐based programmes had to have reported methods of data collection and data analysis, and people's perspectives, beliefs, feelings, understanding, experiences or behaviour about exercise or advice on exercise that were presented as data (e.g. direct quotes from participants or description of findings). There were no limits on location or language; however, quantitative clinical trials or qualitative studies had to be published after 1985 because of the paucity of well‐designed and well‐reported relevant studies prior to 1985.

Types of participants

We included studies with men, women, or both, aged 45 years or older, with a clinical diagnosis of OA (as defined by the study) or self‐reported chronic hip or knee (or both) pain (defined as more than six months' duration).

Types of interventions

Exercise‐based rehabilitation programmes could consist of any type of land‐based or aquatic‐based exercise programme aiming to improve OA symptoms delivered in hospitals or the community. Programmes could vary in content (e.g. range of motion, aerobics, Tai Chi) and their delivery mode (classes or individual therapy), length, frequency or intensity. The comparator (control group) could consist of no treatment, waiting list group or any non‐exercise intervention (e.g. medication, lifestyle/diet changes, information on OA).

Types of outcome measures

The major outcomes of interest were pain, physical function, self‐efficacy, depression, anxiety, quality of life and adverse effects of exercise.

For quantitative synthesis, randomised controlled trials (RCT) had to have measured either pain or function and at least one psychosocial outcome (self‐efficacy, depression, anxiety, quality of life). Quality of life related to a range of factors, which the World Health Organization (WHO) identifies as "physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal belief and their relationship to salient features of their environment" (WHO 1997).

The qualitative synthesis studies had to have reported people's opinions and experiences of exercise (e.g. their views and beliefs about the utility of exercise in the management of chronic pain, or barriers to adherence to exercise advice).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

In July 2012, we searched electronic databases using comprehensive strings of thesaurus and free‐text terms for the key features:

condition: chronic knee and hip pain (e.g. 'osteoarthritis/chronic joint pain');

intervention: 'exercise,' physical activity, aerobic, walking, Tai Chi, physiotherapy.

The two strings were combined to identify reports that contained terms for both features (population AND topic). An example of the thesaurus and free‐text strings applied to PubMed is provided in Appendix 1.

These search strategies were applied to 23 clinical, public health, psychology and social care databases (Appendix 2), 25 other resources by handsearching (Appendix 2), and references of included studies. We contacted key experts/authors to identify any other potentially relevant studies.

We conducted follow‐up searches in March 2014 and March 2016 to ensure any further trials that had been published and which met criteria could be included in the review.

Searching other resources

We checked references of included studies by:

checking where included studies had been cited, using Google Scholar;

checking references of selected reviews in the topic area that the research team were aware of from a systematic review of reviews on adult social care; outcomes concurrently being undertaken at the EPPI‐Centre;

asking key experts/authors of included studies.

We engaged with experts from the research, advocacy and policy sectors in the field of OA rehabilitation. They informed key stages in the review including: advising on the scope, informing the search strategy, reviewing the final report and disseminating the research findings.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Review authors applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to titles and abstracts. We obtained full‐text reports for studies that appeared to meet the criteria. We extracted data and information from these studies and entered them into a database and reapplied the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We included studies that met the inclusion criteria in the review. All review authors involved in study screening (KD, HH, MH, NW) took part in a moderation exercise where results were discussed to ensure consistency in applying the review inclusion/exclusion criteria. For the initial title and abstract screening, we carried out a "double screening" of 200 papers before continuing with independent screening. For the screening of full reports, a second review author independently applied the criteria on 10% of the reports. A 90% agreement rate was required before proceeding to independent screening. Review authors (KD, HH, MH, NW) independently screened the remaining sample of potential studies. Where a review author (e.g. HH) was unable to reach a decision, consensus was reached through discussion with a second review author (e.g. KD) or, if required, a third review author (MH or NW). In two cases where there was doubt over whether a study should be included (Jenkinson 2009; Thomas 2002), we contacted authors but received no reply and the studies unfortunately had to be excluded as a result.

Data extraction and management

We used EPPI‐Reviewer software to manage the review (Thomas 2002). Four review authors (KD, HH, MH, NW) extracted descriptive details from the full reports using a prepiloted data collection form. If a review author was an author of one of the included studies, they were not involved in any decisions regarding data extraction from that study.

We extracted the following information from all studies:

aims and focus of the research;

study design;

-

details about the intervention including:

format: written, didactic, non‐participatory/participatory, lay/professional led, individual/group therapy, etc.;

content: type, frequency, intensity, etc.;

setting: hospital/outpatient/community/home‐based, etc.;

-

details about the study populations and settings as per the PROGRESS‐Plus framework (Kavanagh 2008):

broad social determinants of health and well‐being (e.g. ethnicity, occupation, gender, education, socioeconomic status);

characteristics that impinge on health and well‐being by attracting discrimination, such as age;

other contextual features pertinent to the experiences of living with knee and hip pain, such as housing.

Quantitative outcome data

For quantitative outcome measurements, whenever possible, we extracted raw scores. Where trials reported pain or function using more than one outcome measure tool, we extracted data according to the following hierarchy: Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale (AIMS), visual analogue scale (VAS) and other. Similarly, preference was given to standardised psychosocial outcomes. A summary of data collected for included studies is reported in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Qualitative "views" data

For qualitative studies that include "views" data, whenever possible, we extracted participant's quotes first, followed by and distinguished from authors' descriptions and analysis of participants' views. We followed the conceptual framework to support the identification of factors potentially impacting on participation in and experiences of exercise (Figure 2). A summary of data collected for included qualitative studies is reported in Appendix 3.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

In pairs, four review authors (HH, KD, MH, NW) independently assessed the risk of bias for all included studies using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias addressing the following criteria (Higgins 2011a).

Sequence generation

The methods used to generate the allocation sequence were categorised as:

low risk of bias (risk of bias avoided or addressed (or both)) if a random component in the sequence generation process was described (e.g. referring to a random number table);

high risk of bias (risk of bias not adequately addressed) if the authors described a non‐random component in the sequence generation process (e.g. sequence was generated by hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias (uncertain risk) if the sequence generation process was not specified.

Allocation sequence concealment

The method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment, or changed after assignment, categorised as:

low risk of bias if an appropriate method was used to conceal allocation (e.g. central allocation including telephone, web‐based and pharmacy‐controlled randomisation; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes) from personnel enrolling participants;

high risk of bias if appropriate method to conceal allocation was not guaranteed;

unclear risk of bias if methods used to conceal allocation were not specified.

Blinding

As it is very difficult to blind providers and recipients to exercise programmes. We assessed the methods used to blind study participants and researchers to the intervention that participants received.

Blinding ofparticipants as:

low risk of bias if the authors described methods taken to blind study participants to the intervention;

high risk of bias if there were no attempts to blind study participants to the intervention;

unclear risk of bias if methods taken to blind study participants were not specified.

Blinding of outcome assessment as:

low risk of bias if the authors stated explicitly that the primary outcome variables were assessed blindly;

high risk of bias if the outcomes were not assessed blindly and this was likely to affect results;

unclear risk of bias if not specified in the paper.

Completeness of outcome data

The individual attrition rate for intervention and control groups, whether exclusions were reported and whether the authors conducted an in intention‐to‐treat analysis were categorised as:

low risk of bias if there were no missing data or missing outcome data were balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for those missing data and unlikely to alter the results of the study;

high risk of bias if missing outcome data were likely to bias the results;

unclear risk of bias if not specified in the paper.

Reporting bias

Outcome reporting was categorised as:

low risk of bias if evidence outcomes were selectively reported (e.g. all relevant outcomes in the methods section were reported in the results section);

high risk of bias if some important outcomes were omitted;

unclear risk of bias if not specified in the paper.

Other bias

Other potential sources of bias were categorised as:

low risk of bias if there was no evidence of other risk of biases, and

high risk of bias if there were concerns of other sources of bias affecting the results.

Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, by consulting a fifth review author.

Assessment of rigour in qualitative studies

We assessed the quality and methodological rigour of "views studies" using a tool developed at the EPPI‐Centre (Harden 2004), which considers whether the findings were grounded in the data and reflected people's views. The development of the criteria was informed by those engaged in ensuring increased transparency and explicit methods for assessing the quality of qualitative research (Boulton 1996; Cobb 1987; Mays 1995; Popay 1998), and was adapted in accordance with the Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group guidance on adopting a quality appraisal framework (Hannes 2011).

We assessed each study according to the extent to which they provide explicit description of:

aims and objectives;

methodology, including systematic data collection methods;

participants;

context, detailing factors important for interpreting the results;

data analysis to establish dependability and validity.

Two review authors (KD, HH) judged the quality of studies containing people's views based upon judgements about the 'dependability' and ‘credibility' of the study's findings. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, by consulting a third review author.

Dependability

The sampling frame, methods of data collection and analysis were categorised as:

high quality (low risk of bias/error) if thorough attempts were made to increase rigour in the sampling, data collection and analysis;

medium quality if some steps were taken to increase rigour in the sampling, data collection and analysis;

low quality if minimal steps were taken or it was unclear what attempts study authors made to avoid methodological bias and error in conducting the study.

Credibility

Credibility was categorised as:

high quality (low risk of bias/error) if the findings were well grounded/supported by the data, contributed either depth or breadth of findings (in relation to their ability to answer the review question) and privileged the perspectives and experiences of people living with OA;

medium quality if studies met the same criteria as high‐quality studies, but were only fairly well grounded in the data;

low quality if studies were 'limited' on any of the above criteria.

Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and by consulting with a third review author (SO).

As one of the aims of the review was to synthesise people's experiences and preferences in relation to exercise to better understand the factors that might contribute to the success of exercise‐rehabilitation programmes, we did not exclude studies failing to meet a minimum quality threshold (i.e. those scoring low for both dependability and credibility). Instead, we used the quality assessment to assess the contribution of each study to the development of explanations and relationships.

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous data

For continuous data measured by the same scale or unit, we calculated mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For similar outcomes measured by a different scale or units, we used standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% CIs.

We presented highly skewed continuous data in tables.

Where standard errors (SE) were reported instead of standard deviations (SD), we used Review Manager 5 to calculate the effect size estimate (RevMan 2014). In one study, the SD was calculated from the SE. Where there were no SDs or SEs reported, we estimated the mean SD from available studies, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b).

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous (binary) data, we calculated risk ratios (RR) with 95% CIs, or converted odds ratios (OR) to SMDs, using the Cox‐Snell formula, and where appropriate we combined results from different trials.

Unit of analysis issues

We identified the level at which randomisation occurred (e.g. individual participants, cluster‐randomised trials, repeated measures) at the data extraction stage and addressed the following issues if they arose:

cluster‐randomised trials: using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) estimates the design effect was calculated and the variance inflated accordingly;

multiple interventions per participant: we analysed studies that compared the effect of two or more types exercise‐based rehabilitation programmes with a control condition;

multiple follow‐up: for trials that measured outcomes at multiple time points, we selected the longest follow‐up.

Dealing with missing data

We recorded the amount of missing data, reasons, pattern (missing completely at random, missing at random, missing not at random) and how the missing data were handled (ignored, last observation carried forward, statistical modelling, etc.) (Carpenter 2008). We performed sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of the missing data on study findings and considered the implications to the review in the Discussion.

Assessment of heterogeneity

All pooled analyses used the I2 statistic to assess the percentage of total variation caused by heterogeneity of the trials (Higgins 2003). We assessed statistical heterogeneity across studies by visual inspection of the forest plot and using the Chi2 test with a significance level of P less than 0.10, and the I2 test and tentatively assign I2 statistic value of:

low heterogeneity: less than 49%;

moderate heterogeneity: 50% to 74%;

high heterogeneity: 75% to 100% (Higgins 2003).

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by analysing subgroups by type of OA (knee, hip, or a combination; age; gender and severity of symptoms; see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

When there was moderate heterogeneity (Chi2 P less than 0.10 and I2 value 50% to 74%), we used a random‐effects model. When there was no clinical and no important statistical heterogeneity (I2 less than 49%), we combined results using a fixed‐effect model. We considered the potential cause of heterogeneity by conducting subgroup and sensitivity analyses as described below.

In the qualitative studies, differences in study setting and sample (e.g. gender, age, type and severity of OA/chronic pain) informed the qualitative synthesis and were used to explain variation in the study's findings.

Assessment of reporting biases

We constructed funnel plots (effect size versus SE) to assess publication bias, if a sufficient number of trials was found (about 10: Sterne 2004). Where possible, we compared the outcomes and comparisons reported in the papers against trial protocols to detect unreported results that may indicate reporting bias.

Assessment of reporting biases were not applied to qualitative studies.

Data synthesis

The methods used to synthesise data were driven by the research question, types of studies/data included, the detail and quality of reporting in these studies and their heterogeneity. The synthesis of study findings was informed by the conceptual framework and the type of interventions identified. If there was a wide variety of approaches and patient populations, we used a random‐effects model in the meta‐analyses.

Quantitative synthesis

Where possible, we used standard methods for statistical meta‐analysis to synthesise data using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014). We used an SMD approach, which scales each outcome at endpoint by its SD, due to the diversity of psychosocial measures. We conducted a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume studies had estimated the same underlying treatment effect (i.e. in trials examining the same intervention, and the trials' populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar). If there was substantial statistical heterogeneity, we used random‐effects models, presented as mean treatment effect with 95% CIs.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We investigated whether subpopulations responded differently to an exercise‐based rehabilitation programme by comparing the responses of different subgroups to the exercise programme. Theoretically, participants who only experience chronic hip pain may respond differently to exercise programmes than people who only experience knee pain, and both respond differently to people with hip and knee pain. Other a priori planned subgroup analyses included age, gender and severity of symptoms as defined by the studies included in the review.

For trials, we tested for heterogeneity across subgroup results and computed an I2 statistic. We used random‐effects models to analyse variation in the mean effects in the different subgroups using meta‐regression techniques to reduce false‐positive results when comparing subgroups in a fixed‐effect model (Higgins 2011b). Post‐hoc subgroups analyses were considered to be exploratory analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

If aspects of a trial (e.g. atypical intervention, methodology, missing information) appeared to unduly influence the review's findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the influence of that study and reported them in a summary table.

For qualitative studies, we considered whether individual and contextual factors explained variation in the type of views identified.

Qualitative synthesis

We synthesised studies of people's views using the framework synthesis used in previous EPPI‐Centre reviews (Lorenc 2008; Oliver 2008). A framework synthesis accommodates a range of different types of studies and can be conducted relatively quickly by a team of review authors.

We extracted verbatim quotes from study participants and author description of findings from the result sections of included studies. We read the text reported in the discussions and conclusions during this data extraction process; however, these sections contained author's conclusions and implications but did not present any new data and, therefore, were not used to inform the synthesis.

Two review authors (KD, HH) independently read through reports and extracted data from the studies. Data were matched against the conceptual framework. As these were broad themes (Figure 1), we used a thematic analysis to identify subthemes. This enabled the existing conceptual framework to be used as the basis for the synthesis, which was then developed further by the introduction of themes from the studies (Figure 3). The themes' codes acted as an index to navigate the data and allowed the literature to be subdivided into manageable sections ready for indepth analysis. Each element of the framework was individually interrogated in turn, tabulating the data under key themes to present distilled summaries.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Both review authors then compared their individual coding. They considered the extent to which each subtheme was mutually exclusive and how they understood the data in relation to their individual coding, reflecting on the review questions' emphasis on participants' meanings and experiences ensuring that the coding did not go beyond the original context of the study. In some cases, both review authors went back to the original studies to check their understanding. Similar themes were then grouped and condensed until a smaller number of subthemes emerged. In some cases, themes originally coded under one broad theme (e.g. environmental factors) had a better fit with another broad theme (e.g. psychological factors). The discussion continued until a consensus was reached on which a priori themes were supported by the data, and whether new themes identified by the review authors did actually map to the pre‐existing broad theme. The result was a finalised list of themes. A diagram of these themes was generated to provide an illustration of the themes and subthemes in the synthesis (Figure 3). Overall drawing together what can be learnt from the tables and summaries and finding associations between themes and providing explanations for those findings across the included studies supported us to illuminate people's responses to aspects of arthritis and approaches to self‐management. This approach has provided a clear path from the original research data, to individual study authors' descriptions and analyses to the findings of the qualitative review synthesis (Appendix 4).

Synthesis integrating quantitative and qualitative findings (integrative review)

Two review authors (SO, KD) reread the qualitative synthesis and generated implications from people's views on what they considered important in supporting their engagement in exercise. After consulting with other review authors (MH, NW), we made refinements until consensus was reached on an agreed set of implications. The implications were generated into a coding tool and two review authors (KD, HH) critically re‐examined the intervention descriptions as reported in the 21 RCTs included in the quantitative synthesis to identify whether they addressed each of the implications.

Having identified which components were contained within each intervention, we aimed to assess the extent to which each component was present in the intervention by answering: 'yes,' 'no/not stated' or 'partially.' Two review authors independently conducted this assessment and then paired up to compare findings and check accuracy of extracted data. Decisions about the extent of a component's presence were based on the trial authors' descriptions and reporting. Detailed information to support 'yes' or 'partially' was required and decisions were recorded on EPPI‐Reviewer. Disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached with the option of referring to a third review author (SO) for resolution if agreement could not be made.

After coding agreements were finalised, the findings were mapped onto a matrix, as previously used in EPPI‐Centre systematic reviews, enabling the integration of controlled trials and view studies to be 'juxtaposed' (Candy 2011). The matrices in the integrative synthesis map the presence of components within the RCTs with the studies' effect sizes and contextual detail on recruitment and intervention description previously extracted as part of the quantitative synthesis. This enabled us to visibly illustrate and interrogate patterns in the findings, supporting the generation of a comparative descriptive narrative addressing the following questions.

Which components of (in)effective interventions correspond with views expressed by participants?

Does this match suggest why or how the intervention (does not) work?

What components appear in effective interventions but not in ineffective interventions?

Does the 'views' synthesis suggest these components are significant from a participant perspective?

Does addressing the psychosocial effects of joint pain improve pain and physical functioning?

Clinical relevance

The social science review authors (KD, HH, SO) conducted the synthesis of qualitative studies and drew implications from that for interventions and the final synthesis across the statistical meta‐analysis and qualitative study synthesis. In each case coreview authors, including two who were both clinicians and coauthors of a trial and two qualitative studies (MH, NW), checked the coherence of the emerging findings. Their responses prompted a reinspection of themes in terms of their roots in the primary studies, their language, their relationship to each other and to the conceptual framework, and the quotes chosen to support the themes. Inaccuracies were corrected, and language and interpretations refined.

Summary of evidence

We prepared a 'Summary of findings' table for the quantitative and qualitative syntheses. For quantitative trials, we used the methods and recommendations described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011), using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro 2008). Similarly, we created a 'Summary of qualitative evidence' to summarise the key findings and be informed by the assessment of rigour, detailing the extent to which the findings are trustworthy, based on their dependability and credibility, in answering the review question.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

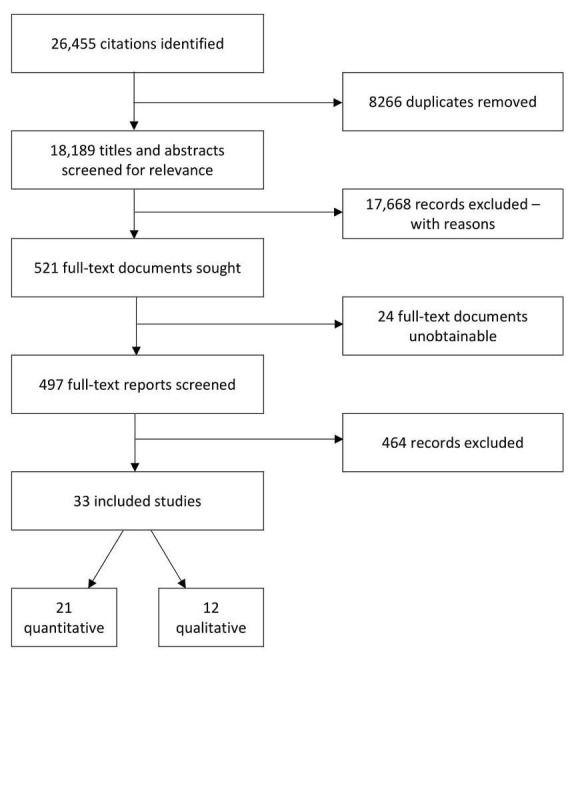

Searches of bibliographic databases and websites, including the update searches to March 2016, yielded 26,455 potentially relevant citations. Figure 4 describes the flow of these records through the screening process. After removing 8266 duplicates, we screened 18,189 titles and abstracts using prespecified eligibility criteria of which 17,668 were excluded. Of the 521 potential reports, 24 were unobtainable and we obtained 497 for full‐text screening. Applying the same criteria used at the title and abstract screening stage, we excluded a further 464 studies. We included 33 studies in the data and analyses consisting of 21 in the quantitative synthesis and 12 in the qualitative synthesis.

Figure 4.

Flow chart of search and screening process.

Included studies

Twenty‐one trials (2372 participants) met the criteria for inclusion in the quantitative synthesis and 12 studies met the criteria for inclusion in the qualitative synthesis. Of the 21 studies identified for the quantitative synthesis, four had three treatment arms and so were split in the meta‐analyses (French 2013; Focht 2005; Hurley 2007; Keefe 2004), and were treated as 25 'comparisons' as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). The three‐arm studies had two entries for some outcomes in the Data and analyses table. Where this was the case, the first arm referred to intervention group and the second arm to intervention group, as outlined in the Characteristics of included studies table. Further details are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Twelve qualitative studies of people's views, opinions and experiences were included (Appendix 3).

Setting

Studies were published between 1998 and 2016. All studies were conducted in high‐income countries. This included nine trials based in the US (Baker 2001; Cheung 2014; Focht 2005; Keefe 2004; Mikesky 2006; Park 2014; Schlenk 2011; Sullivan 1998; Wang 2009); three in Australia (Bennell 2014; Bennell 2016; Fransen 2007); and one each in Ireland (French 2013), the UK (Hurley 2007), the Netherlands (Hopman‐Rock 2000); South Korea (Kim 2012), Turkey (Aglamis 2008), Canada (Péloquin 1999), Taiwan (Kao 2012), Norway (Fernandes 2010), and Hong Kong (Yip 2007).

All the studies providing qualitative data were published from 2005 onwards. This date reflected the development of qualitative methodology and its widening uptake being relatively recent developments, and earlier studies found through the search were of insufficient quality to include. Four studies were based in the UK (Campbell 2001; Hendry 2006; Hurley 2010; Morden 2011), three in New Zealand (Fisken 2016; Larmer 2014b; Moody 2012); and one each in Australia (Hinman 2016), Canada (Stone 2015), Sweden (Thorstensson 2006), Iceland (Petursdottir 2010), and the Netherlands (Veenhof 2006).

All included papers were written in English.

Design

Twenty studies evaluating the effectiveness of exercise programmes used individual participant randomised controlled designs and one study used a cluster randomised control design (Hurley 2007). Seventeen trials had two arms (Aglamis 2008; Baker 2001; Bennell 2014; Bennell 2016; Cheung 2014; Fernandes 2010; Fransen 2007; Hopman‐Rock 2000; Kao 2012; Kim 2012; Mikesky 2006; Park 2014; Péloquin 1999; Schlenk 2011; Sullivan 1998; Wang 2009; Yip 2007), and four studies had three arms (Focht 2005; French 2013; Hurley 2007; Keefe 2004). Seven studies compared exercise with a usual care control arm (Hurley 2007; Kao 2012; Keefe 2004; Kim 2012; Péloquin 1999; Schlenk 2011; Yip 2007), nine trials with an attention control (Baker 2001; Bennell 2014; Bennell 2016; Fernandes 2010; Focht 2005; Mikesky 2006; Park 2014; Sullivan 1998; Wang 2009), and five studies with a 'wait list' control (Aglamis 2008; Cheung 2014; Fransen 2007; French 2013; Hopman‐Rock 2000).

All the studies included in the qualitative synthesis sought the views of people living with OA on aspects ranging from health beliefs to their experiences of exercise. Seven studies aimed to examine factors associated with exercise adherence, compliance and take up through the concepts of motivation and facilitators and barriers to participation in exercise (Campbell 2001; Fisken 2016; Hendry 2006; Petursdottir 2010; Stone 2015; Thorstensson 2006; Veenhof 2006). In the remaining five studies, the aims were to explore people's views of arthritis and exercise as a treatment (Hurley 2010), models of lay management (Morden 2011), and perceptions of an exercise intervention (Hinman 2016; Larmer 2014b; Moody 2012). Six studies included participants who had taken part in a formal evaluation of an exercise intervention, from which participants were drawn for indepth interviews; these participants were actively engaged in exercise (Campbell 2001; Hinman 2016; Hurley 2010; Moody 2012; Thorstensson 2006; Veenhof 2006). In the remaining six studies with no exercise intervention, participants' engagement in exercise ranged from sedentary to actively engaged in exercise and everyday activities (Fisken 2016; Hendry 2006; Larmer 2014b; Morden 2011; Petursdottir 2010; Stone 2015).

Study size

The sample size of studies varied; the largest study randomly assigned 418 people (Hurley 2007), while the smallest randomly assigned only 21 people (Schlenk 2011). Overall, 11 studies had a sample size of fewer than 100 participants (Aglamis 2008; Baker 2001; Cheung 2014; Fransen 2007; Hopman‐Rock 2000; Keefe 2004; Kim 2012; Park 2014; Schlenk 2011; Sullivan 1998; Wang 2009), and 10 studies had sample size between 102 and 418 participants (Bennell 2014; Bennell 2016; Fernandes 2010; Focht 2005; French 2013; Hurley 2007; Kao 2012; Mikesky 2006; Péloquin 1999; Yip 2007).

The largest qualitative views study had a sample size of 29 participants (Hurley 2010), and the smallest contained six participants (Hinman 2016), with remaining sample sizes ranging from 12 to 22 participants (Campbell 2001; Fisken 2016; Hendry 2006; Larmer 2014b; Moody 2012; Morden 2011; Petursdottir 2010; Stone 2015; Thorstensson 2006; Veenhof 2006).

Outcomes

Pain

Of the 21 studies included in the review, only one did not measure pain (Schlenk 2011): it was still included because of its measurement of function. Nine studies used the WOMAC (Aglamis 2008; Baker 2001; Cheung 2014; Fernandes 2010; Focht 2005; Fransen 2007; Hurley 2007; Mikesky 2006; Wang 2009), five studies used the VAS Pain (Bennell 2014; Bennell 2016; Hopman‐Rock 2000; Kim 2012; Yip 2007), and two studies used the AIMS (Keefe 2004; Sullivan 1998). The study by French 2013 used a 'numerical rating scale' to measure pain severity during daytime activities and at night. In addition, Park 2014 used the McGill Pain Questionnaire, Péloquin 1999 used the Doyle's Joint Index and Kao 2012 used a health‐related quality of life measure for body pain.

Physical function

Eighteen studies measured function. Thirteen studies used the WOMAC (Aglamis 2008; Baker 2001; Bennell 2014; Bennell 2016; Cheung 2014; Fernandes 2010; Focht 2005; Fransen 2007; French 2013; Hurley 2007; Mikesky 2006; Schlenk 2011; Wang 2009); two used AIMS subscales (Péloquin 1999; Sullivan 1998); one used a health‐related quality of life measure (Kao 2012); one used gait speed tests, the six‐minute walk test and Berg Balance Scale (Park 2014); and one used a modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) (Yip 2007).

Self‐efficacy

Eleven studies measured self‐efficacy (Bennell 2014; Bennell 2016; Focht 2005; Hopman‐Rock 2000; Hurley 2007; Keefe 2004; Kim 2012; Schlenk 2011; Sullivan 1998; Yip 2007; Wang 2009). Measures included those designed specifically for people living with OA (e.g. the Arthritis Self‐Efficacy Scale), or focused on beliefs about ability to exercise.

Depression and anxiety

Three studies measured anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Fransen 2007; French 2013; Hurley 2007). Two studies measured depression, anxiety and stress using the 21‐item Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales (Bennell 2014; Bennell 2016). Three studies measured depression only, two used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D) (Mikesky 2006; Wang 2009), and one study translated a "depression self‐rated measure for use in Korean" (Kim 2012).

Health‐related quality of life

Five studies used the 36‐item Short Form (SF‐36) measure of health‐related quality of life providing individual scores for four mental health‐related subscales (e.g. emotional role, vitality, social functioning and mental health) (Aglamis 2008; Baker 2001; Fernandes 2010; Focht 2005; Kao 2012).

Sleep quality

One study measured sleep quality using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (Cheung 2014).

Population characteristics

Symptoms

Fourteen studies recruited participants with knee OA only (Aglamis 2008; Baker 2001; Bennell 2016; Cheung 2014; Focht 2005; Hurley 2007; Kao 2012; Keefe 2004; Mikesky 2006; Péloquin 1999; Schlenk 2011; Sullivan 1998; Wang 2009; Yip 2007), three studies recruited participants with hip OA only (Bennell 2014; Fernandes 2010; French 2013), and four studies included participants with hip OA or knee OA (or both) (Fransen 2007; Hopman‐Rock 2000; Kim 2012; Park 2014).

Participants in six of the studies reporting people's views had a diagnosis or experienced chronic pain in the knee only (Campbell 2001; Hendry 2006; Hinman 2016; Hurley 2010; Morden 2011; Thorstensson 2006), and six studies recruited participants living with OA of the lower limbs (Fisken 2016; Larmer 2014b; Moody 2012; Petursdottir 2010; Stone 2015; Veenhof 2006).

Gender

Three trials recruited only women (Aglamis 2008; Cheung 2014; Kim 2012), while the remaining were mixed samples.

In the qualitative studies, one study recruited only women (Fisken 2016). Eleven studies enrolled both men and women with women outnumbering men in all but two of the studies (Hinman 2016; Thorstensson 2006).

Ethnicity

Only one trial, conducted in the US, reported the ethnicity of participants (eight African‐American, three Hispanic/Latino and 91 Anglo‐American; Sullivan 1998). Cheung 2014 reported that 86% of participants were white and Park 2014 reported that 61.8% of participants were non‐Hispanic white, but neither study provided details of ethnicity of the remainders of their samples.

The majority of the qualitative studies did not explicitly state the ethnicity of participants. Of the three studies that reported ethnicity, participants were of black African, black Caribbean, Maori, Samoan, Indian or white ethnic backgrounds (Fisken 2016: six New Zealand European, two Maori, three others; Hurley 2010: three black African, five black Caribbean, one Indian and 20 Caucasian; Larmer 2014b: 14 New Zealand European, one Samoan).

Description of intervention

Types of exercise programmes

Of the 20 studies evaluating land‐based exercise programmes, seven studies combined strength training with different forms of aerobic exercise (Aglamis 2008; Focht 2005; Hurley 2007; Keefe 2004; Péloquin 1999; Schlenk 2011; Sullivan 1998), eight delivered strength‐based resistance training programmes (Baker 2001; Bennell 2014; Bennell 2016; Fernandes 2010; French 2013; Hopman‐Rock 2000; Kao 2012; Mikesky 2006), three provided Tai Chi (Fransen 2007; Wang 2009; Yip 2007), and two provided yoga (Cheung 2014; Park 2014). One study provided water‐based exercise (Kim 2012).

Thirteen studies had interventions with an educational component. Seven studies delivered educational interventions aimed at enhancing coping strategies and self‐efficacy (Bennell 2016; Fernandes 2010; Hurley 2007; Keefe 2004; Park 2014; Schlenk 2011; Yip 2007); five studies provided one‐off sessions on a range of topics such as types of OA, risk factors, pain management of OA, problem solving and self‐efficacy (Aglamis 2008; Hopman‐Rock 2000; Kao 2012; Kim 2012; Sullivan 1998); and one study provided patient information leaflets about OA (French 2013).

Activities carried out within the exercise programmes varied across the studies. More common interventions included walking or cycling (or both) for aerobic exercise, and isotonic exercises (i.e. incorporating movement) such as knee extensions and step‐ups for strength training. Combinations of different exercise protocols were widely utilised, and the attributes of these (exercises, sets and repetitions, location and frequency of exercise sessions) varied from study to study.

Format and setting

Twelve studies delivered exercise interventions in a group format (Cheung 2014; Fransen 2007; Hopman‐Rock 2000; Hurley 2007; Kao 2012; Keefe 2004; Kim 2012; Mikesky 2006; Park 2014; Sullivan 1998; Wang 2009; Yip 2007). Seven studies delivered exercise as one‐to‐one sessions either at home or at a facility (Baker 2001; Bennell 2014; Bennell 2016; Focht 2005; French 2013; Péloquin 1999; Schlenk 2011). Two studies comprised of group‐based sessions and an individual physical therapy (Fernandes 2010; Hurley 2007). It was unclear in one study in which format the exercise was delivered (Aglamis 2008). In six studies, the interventions contained elements of behaviour‐graded exercise with an individualised exercise programme for each participant (Aglamis 2008; Baker 2001; Fernandes 2010; French 2013; Hurley 2007; Kao 2012).

Only two of the qualitative studies involved a water‐based exercise intervention (Moody 2012; Larmer 2014b), four studies were land‐based exercise interventions (Campbell 2001; Hinman 2016; Hurley 2010; Veenhof 2006), two studies were home‐based (Campbell 2001; Hinman 2016), and two studies were in primary care/community settings (Hurley 2010; Veenhof 2006).

Intervention providers

Fifteen studies delivered the exercise interventions by trained professionals who were fitness/exercise instructors or physiotherapists (Aglamis 2008; Bennell 2014; Bennell 2016; Cheung 2014; Fernandes 2010; French 2013; Hopman‐Rock 2000; Hurley 2007; Kao 2012; Keefe 2004; Kim 2012; Mikesky 2006; Park 2014; Schlenk 2011; Sullivan 1998). In two studies involving Tai Chi used instructors who were qualified Tai Chi Masters (Fransen 2007; Wang 2009), and one study used a nurse specially trained to deliver Tai Chi (Yip 2007). The remaining three studies did not state who delivered the interventions (Baker 2001; Focht 2005; Péloquin 1999).

Excluded studies

A total of 395 studies did not meet the eligibility criteria and were excluded from the review. For brevity, a sample of 62 excluded studies and their reasons are shown in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias is summarised in Table 3 and also shown in the 'Risk of bias' graph in Figure 3 and the 'Risk of bias' summary in Figure 5.

Table 1.

Quality of evidence ‐ dependability and credibility ‐ of the qualitative studies

| No | Study | Quality of evidence | |||||

| Dependabilityof findings | Credibilityof findings | ||||||

| Author | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | |

| 1 | Campbell 2001 | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ |

| 2 | Fisken 2016 | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ |

| 3 | Hendry 2006 | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ |

| 4 | Hinman 2016 | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ |

| 5 | Hurley 2010 | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ |

| 6 | Larmer 2014b | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ |

| 7 | Moody 2012 | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ |

| 8 | Morden 2011 | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ | ✔ | |

| 9 | Petursdottir 2010 | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ |

| 10 | Stone 2015 | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ |

| 11 | Thorstensson 2006 | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ |

| 12 | Veenhof 2006 | ‐ | ✔ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ✔ |

Figure 5.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

The assessment of the quality of the design and risk of bias of the quantitative studies included in this review are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table and Table 3.

Allocation

Six studies had a high or unclear level of allocation bias. The methods used to generate the randomisation were unclear and therefore introduced a risk of bias in five of the 21 studies (Hopman‐Rock 2000; Kao 2012; Keefe 2004; Kim 2012; Schlenk 2011). Allocation in one study was partly based on people with more severe Alzheimer's being unsuited to the intervention thus introduced bias, and the procedure for allocation may have given some participants an increased chance of choosing a particular condition, creating high risk of bias (Park 2014).

Allocation concealment was poorly described, giving a high risk of bias in 11 studies (Focht 2005; Hopman‐Rock 2000; Kao 2012; Keefe 2004; Kim 2012; Mikesky 2006; Park 2014; Péloquin 1999; Schlenk 2011; Sullivan 1998; Yip 2007). The remaining studies were at low risk of allocation concealment.

Blinding

Twenty of the studies did not conduct blinding of participants due to the difficult nature of blinding to exercise interventions. However, one study used an innovative sham treatment design, with participants not identifying beyond numbers expected by chance whether their treatment was sham or genuine (James test), thus reducing risk of bias for participants (Bennell 2014), although exercise participants were not blinded to their intervention. Eight of the studies did not blind the outcome assessors and so had a high risk of bias (Baker 2001; French 2013; Kao 2012; Keefe 2004; Kim 2012; Schlenk 2011; Sullivan 1998; Yip 2007). All studies utilised participant self‐report scales, and since there were no attempts to blind participants in 20 of the 21 studies, this may have led to reporting bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Three studies had a high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data (Kao 2012; Park 2014; Yip 2007). Five studies were at unclear risk of bias (Aglamis 2008; Kim 2012; Mikesky 2006; Péloquin 1999; Sullivan 1998). The remaining studies were at low risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

All the studies reported all the outcomes mentioned in their methods sections giving them all a low risk of bias in selective reporting.

Other bias

One study was at unclear risk of other bias as the authors reported no statistically significant baseline differences between groups but did not report the values (Schlenk 2011). The remaining studies were at low risk of other bias.

Threats to rigour of qualitative studies

Rigour of qualitative studies

Table 2.

Quality appraisal of qualitative studies

| Quality appraisal question | Answer options | |||

| Not at all/not stated | Few steps | Several steps | A thorough attempt | |

| 1. Were steps taken to increase rigour in sampling? | 0 studies | 1 study Thorstensson 2006 |

7 studies Fisken 2016; Hurley 2010; Larmer 2014b; Moody 2012; Morden 2011; Petursdottir 2010; Stone 2015 |

4 studies Campbell 2001; Hendry 2006; Hinman 2016; Veenhof 2006 |

| 2. Were steps taken to increase rigour in data collection? | 0 studies | 0 studies | 7 studies Campbell 2001; Fisken 2016; Hinman 2016; Hurley 2010; Larmer 2014b; Moody 2012; Veenhof 2006 |

5 studies Hendry 2006; Morden 2011; Petursdottir 2010; Stone 2015; Thorstensson 2006 |

| 3. Were steps taken to increase rigour in data analysis? | 0 studies | 0 studies | 6 studies Campbell 2001; Fisken 2016; Hurley 2010; Larmer 2014b; Moody 2012; Stone 2015 |

6 studies Hendry 2006; Hinman 2016; Morden 2011; Petursdottir 2010; Thorstensson 2006; Veenhof 2006 |

| Quality appraisal question | No grounding | Limited grounding/support | Fairly well grounded | Well grounded/supported |

| 4. Were the findings of the study grounded in/supported by data? | 0 studies | 0 studies | 4 studies Campbell 2001; Fisken 2016; Moody 2012; Veenhof 2006 |

8 studies Hendry 2006; Hinman 2016; Hurley 2010; Larmer 2014b; Morden 2011; Petursdottir 2010; Stone 2015; Thorstensson 2006 |

| Quality appraisal question | Limited breadth and depth | Good/fair breadth, limited depth | Good/fair depth, limited breadth | Good/fair breadth and depth |

| 5. Breadth and depth of findings? | 0 studies | 3 studies Fisken 2016; Larmer 2014b; Petursdottir 2010 |

3 studies Moody 2012; Morden 2011; Veenhof 2006 |

6 studies Campbell 2001; Hendry 2006; Hinman 2016; Hurley 2010; Stone 2015; Thorstensson 2006 |

| Quality appraisal question | Not at all | A little | Somewhat | A lot |

| 6. To what extent did the study privilege the perspectives and experiences | 0 studies | 0 studies | 6 studies Fisken 2016; Hurley 2010; Moody 2012; Morden 2011; Thorstensson 2006; Veenhof 2006 |

6 studies Campbell 2001; Hendry 2006; Hinman 2016; Larmer 2014b; Petursdottir 2010; Stone 2015 |

Dependability of qualitative studies

See Table 3.

Sampling

Eleven of the 12 studies were judged to have made a thorough attempt (Campbell 2001; Hendry 2006; Hinman 2016; Veenhof 2006) or took several steps (Fisken 2016; Hurley 2010; Larmer 2014b; Moody 2012; Morden 2011; Petursdottir 2010; Stone 2015), to increase rigour in the sampling process (Table 4). Studies attempted to sample a diverse range of participants to represent geographic or socioeconomic diversity, or both. Participant recruitment strategies included sampling from the wider community, two or more GP surgeries or through existing evaluations of exercise programmes. Only one study was judged as making a 'few steps' because of lack of detail in their reporting (Thorstensson 2006).

Data collection