Abstract

Background

Edentulism is relatively common and is often treated with the provision of complete or partial removable dentures. Clinicians make final impressions of complete dentures (CD) and removable partial dentures (RPD) using different techniques and materials. Applying the correct impression technique and material, based on an individual's oral condition, improves the quality of the prosthesis, which may improve quality of life.

Objectives

To assess the effects of different final‐impression techniques and materials used to make complete dentures, for retention, stability, comfort, and quality of life in completely edentulous people.

To assess the effects of different final‐impression techniques and materials used to make removable partial dentures, for stability, comfort, overextension, and quality of life in partially edentulous people.

Search methods

Cochrane Oral Health’s Information Specialist searched the following databases: Cochrane Oral Health’s Trials Register (to 22 November 2017), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Cochrane Register of Studies, to 22 November 2017), MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 22 November 2017), and Embase Ovid (21 December 2015 to 22 November 2017). The US National Institutes of Health Trials Registry (ClinicalTrials.gov) and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform were searched for ongoing trials. No restrictions were placed on language or publication status when searching the electronic databases, however the search of Embase was restricted by date due to the Cochrane Centralised Search Project to identify all clinical trials and add them to CENTRAL.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing different final‐impression techniques and materials for treating people with complete dentures (CD) and removable partial dentures (RPD). For CD, we included trials that compared different materials or different techniques or both. In RPD for tooth‐supported conditions, we included trials comparing the same material and different techniques, or different materials and the same technique. In tooth‐ and tissue‐supported RPD, we included trials comparing the same material and different dual‐impression techniques, and different materials with different dual‐impression techniques.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently, and in duplicate, screened studies for eligibility, extracted data, and assessed the risk of bias for each included trial. We expressed results as risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous outcomes, and as mean differences (MD) or standardised mean differences (SMD) for continuous outcomes, with 95% confidence intervals (CI), using the random‐effects model. We constructed 'Summary of findings' tables for the main comparisons and outcomes (participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life, quality of the denture, and denture border adjustments).

Main results

We included nine studies in this review. Eight studies involved 485 participants with CD. We assessed six of the studies to be at high risk of bias, and two to be at low risk of bias. We judged one study on RPD with 72 randomised participants to be at high risk of bias.

Overall, the quality of the evidence for each comparison and outcome was either low or very low, therefore, results should be interpreted with caution, as future research is likely to change the findings.

Complete dentures

Two studies compared the same material and different techniques (one study contributed data to a secondary outcome only); two studies compared the same technique and different materials; and four studies compared different materials and techniques.

One study (10 participants) evaluated two stage–two step, Biofunctional Prosthetic system (BPS) using additional silicone elastomer compared to conventional methods, and found no evidence of a clear difference for oral health‐related quality of life, or quality of the dentures (denture satisfaction). The study reported that BPS required fewer adjustments. We assessed the quality of the evidence as very low.

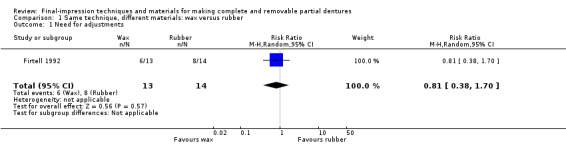

One study (27 participants) compared selective pressure final‐impression technique using wax versus polysulfide elastomeric (rubber) material. The study did not measure quality of life or dentures, and found no evidence of a clear difference between interventions in the need for adjustments (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.70). We assessed the quality of the evidence as very low.

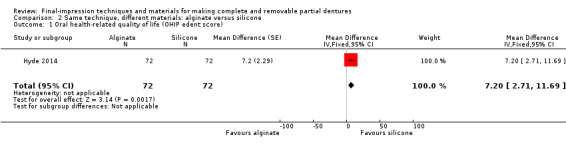

One study compared two stage–two step final impression with alginate versus silicone elastomer. Oral health‐related quality of life measured by the OHIP‐EDENT seemed to be better with silicone (MD 7.20, 95% CI 2.71 to 11.69; 144 participants). The study found no clear differences in participant‐reported quality of the denture (comfort) after a two‐week 'confirmation' period, but reported that silicone was better for stability and chewing efficiency. We assessed the quality of the evidence as low.

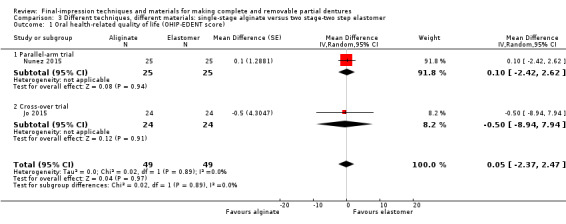

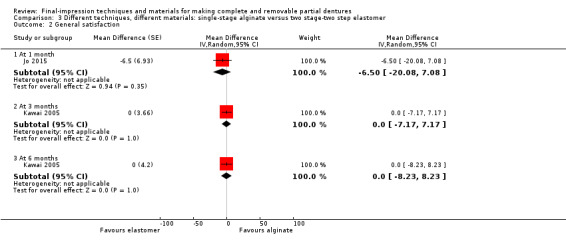

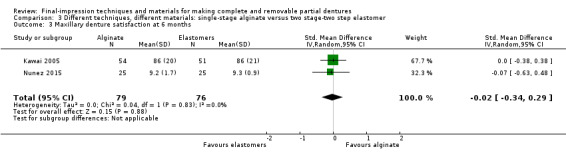

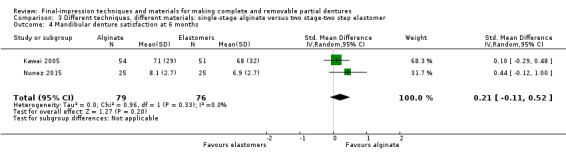

Three studies compared single‐stage impressions with alginate versus two stage‐two step with elastomer (silicone, polysulfide, or polyether) impressions. There was no evidence of a clear difference in the OHIP‐EDENT at one month (MD 0.05, 95% CI ‐2.37 to 2.47; two studies, 98 participants). There was no evidence of a clear difference in participant‐rated general satisfaction with dentures at six months (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐8.23 to 8.23; one study, 105 participants). We assessed the quality of the evidence as very low.

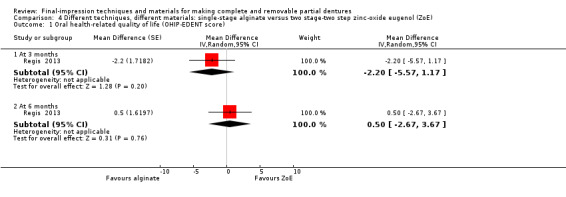

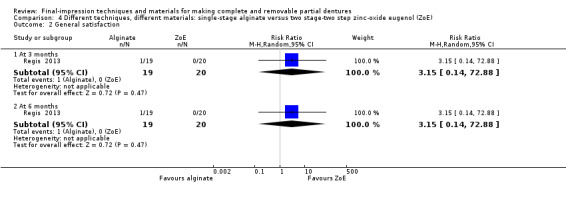

One study compared single‐stage alginate versus two stage‐two step using zinc‐oxide eugenol, and found no evidence of a clear difference in OHIP‐EDENT (MD 0.50, 95% CI ‐2.67 to 3.67; 39 participants), or general satisfaction (RR 3.15, 95% CI 0.14 to 72.88; 39 participants) at six months. We assessed the quality of the evidence as very low.

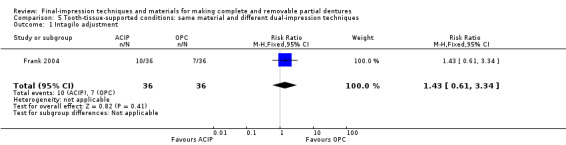

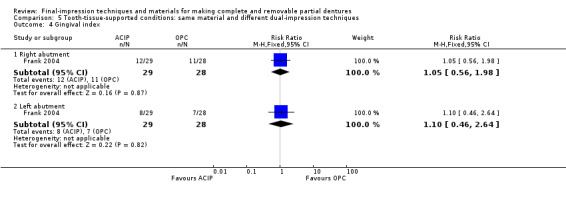

Removable partial dentures

One study randomised 72 participants and compared altered‐cast technique versus one‐piece cast technique. The study did not measure quality of life, but reported that most participants were satisfied with the dentures and there was no evidence of any clear difference between groups for general satisfaction at one‐year follow‐up (low‐quality evidence). There was no evidence of a clear difference in number of intaglio adjustments at one year (RR 1.43, 95% CI 0.61 to 3.34) (very low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

We conclude that there is no clear evidence that one technique or material has a substantial advantage over another for making complete dentures and removable partial dentures. Available evidence for the relative benefits of different denture fabrication techniques and final‐impression materials is limited and is of low or very low quality. More high‐quality RCTs are required.

Keywords: Humans; Dental Impression Materials; Dental Impression Technique; Denture, Partial, Removable; Dentures; Denture Design; Denture Design/methods; Denture Retention; Denture Retention/methods; Mouth, Edentulous; Mouth, Edentulous/rehabilitation; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Techniques and materials for final impressions when making complete and partial removable dentures

Review question

In this review, conducted through Cochrane Oral Health, our aim was to evaluate which technique and material should be used for the final impression when making complete and partial removable dentures, to increase the quality of the denture, and improve oral health‐related quality of life for the individual.

Background

It is common for elderly people to have lost some, or all of their teeth (edentulism). This has a significant impact on their quality of life. There are several steps to making complete and removable partial dentures. The final impression is a very important step for ensuring the quality of the denture in terms of satisfaction, comfort, stability of the denture, and chewing ability. There are a number of different techniques and materials used for making the final impression for complete dentures or removable partial dentures. There is no consensus on which are the best.

Study characteristics

The evidence in this review is current to 22 November 2017. We found eight studies with a total of 485 participants for complete dentures, and one study with 72 participants for removable partial dentures. The participants ranged from 45 to 75 years old, and had been without their teeth for 10 to 35 years. The studies compared different materials used to make the final impression for dentures (alginate, zinc‐oxide eugenol, wax, and addtional silicone, polysulfide or polyether) and different techniques for making the final impression (open‐mouth versus closed‐mouth, single‐stage versus two stage‐two step), or both.

Key results

For most comparisons and outcomes, there was no evidence of a clear difference between the techniques or materials compared.

Very low quality‐evidence from one study (10 participants) suggested that making dentures with an additional silicone elastomer biofunctional prosthetic required fewer adjustments than conventional methods.

Low‐quality evidence from another study (144 participants) suggested that complete dentures made with silicone elastomer in a two stage–two step final impression, may be better than those made with alginate, in terms of oral health‐related quality of life, stability of the denture, and chewing efficiency.

With the limited evidence available, we are unable to draw any conclusions about the best impression techniques and materials for complete and partial removable dentures. There is a need for further research in this area.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence base overall is low to very low. Only one or two studies assessed each intervention and comparison, and most of the studies were at high risk of bias. Many of the studies did not measure our key outcomes. For both complete and partial removable dentures, we conclude that we have no reliable findings.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Complete dentures: same materials, different final‐impression techniques.

| BPS versus CCD techniques for making dentures for completely edentulous people | ||||||

|

Population: completely edentulous people Setting: university department of prosthodontics Intervention: biofunctional prosthetic system (Accu‐dent System) Comparison: traditional technique | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number pf participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with selective pressure | |||||

| Participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life (OHIP‐EDENT) Follow‐up: 3 months |

10 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | OHIP‐EDENT median scores: BPS 34.5; CCD 35.8. No clear difference between groups2 | |||

| Participant‐reported quality of the denture ‐ denture satisfaction Follow‐up: 3 months |

10 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | VAS median scores: BPS 86.5; CCD 88. No clear difference between groups2 | |||

| Number of border adjustments and sore spots after insertion of denture Follow‐up: 3 months |

10 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | Median number of denture adjustments: BPS 3.5; CCD 4.5. BPS required fewer adjustments2 | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio; BPS: closed mouth two stage‐two step with addition silicone elastomer (Biofunctional Prosthetic System); CCD: open mouth two stage‐two step conventional technique using elastomer; VAS: visual analogue scale | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded the quality of the evidence by one level for high risk of bias and two levels for sparse data

2 Data were taken directly from the published study report

Summary of findings 2. Complete dentures: same technique, different final‐impression materials.

| Wax versus polysulfide rubber for making dentures for completely edentulous people | ||||||

|

Population: completely edentulous people Setting: university dental clinic Intervention: wax Comparison: polysulfide rubber | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with rubber | Risk with wax | |||||

| Participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life (OHIP‐EDENT) | Not measured | |||||

| Participant‐reported quality of the denture | Not measured | |||||

| Number of border adjustments and sore spots after insertion of denture Follow‐up: one year |

571 per 1000 | 463 per 1000 (217 to 971) | RR 0.81 (0.38 to 1.70) | 27 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 2 3 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded for risk of bias due to the single study contributing data for this outcome being at unclear risk of bias in many domains

2 Downgraded for imprecision due to the wide 95% CI starting from 0.38 highly beneficial to 1.70 no benefit.

3 Downgraded for indirectness due to the single study with only 27 participants. Hence generalisation becomes difficult.

Summary of findings 3. Complete dentures: same technique, different final‐impression materials.

| Alginate versus silicone for making dentures for completely edentulous people | ||||||

|

Population: completely edentulous people Setting: university dental clinic Intervention: alginate Comparison: silicone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with silicone | Risk with alginate | |||||

| Participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life (OHIP‐ EDENT) (low score better oral health) Follow‐up: 2 weeks |

Mean score 28.9 | MD 7.2 higher on average (2.71 higher to 11.69 higher) | ‐ | 144 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1, 2 | |

| Participant‐reported quality of the denture Follow‐up: two weeks |

The study reported that there was no difference between groups for comfort, but that more participants reported better stability and chewing efficiency with silicone. Data were not amenable to analysis | |||||

| Number of border adjustments and sore spots after insertion of denture Follow‐up: two weeks |

Not measured | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded for indirectness as it is the only study that has used alginate as final (wash) impression hence it cannot be generalised.

2 Downgraded for imprecision as the 95% CI is wide and includes the possibility of the mean difference being clinically unimportant.

Summary of findings 4. Complete dentures: different techniques, different materials.

| Single stage with alginate versus two stage‐two step elastomer for making dentures for completely edentulous people | ||||||

|

Population: completely edentulous people Setting: university dental clinic Intervention: single stage with alginate Comparison: two stage‐two step with elastomer | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with elastomer | Risk with alginate | |||||

| Participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life (OHIP‐EDENT) Follow‐up: 1 month | Mean (OHIP‐EDENT) score was 18 | MD 0.05 higher on average (2.37 lower to 2.47 higher) | ‐ | 98 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 2 3 | |

| Participant‐reported quality of the denture ‐ general satisfaction Follow‐up: 6 months | Mean general satisfaction was 79 | MD 0 on average (8.23 lower to 8.23 higher) | ‐ | 105 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 3 4 | Satisfaction with maxillary and mandibular dentures were also assessed separately by two studies (155 participants), with no evidence of a difference in satisfaction between groups at six months. |

| Number of border adjustments and sore spots after insertion of denture | Not measured | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded for imprecision due to the wide 95% CI

2 Downgraded for indirectness due to study participants with long period of edentulousness (mean range 24 to 38 years) and poor prognostic factors for success of denture in both groups (ACP classification was at least 69% to 73% in ACP III and ACP IV)

3 Downgraded for risk of bias as allocation concealment was at unclear risk of bias and clinicians were not blinded.

4 Downgraded for imprecision due to the wide 95% CI. Single study with 105 participants

Summary of findings 5. Complete dentures: different techniques, different materials.

| Single‐stage with alginate versus two step‐two stage with ZoE for making dentures for completely edentulous people | ||||||

|

Population: completely edentulous people Setting: dental school hospital Intervention: single‐stage with alginate Comparison: two step‐two stage with ZoE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with ZoE | Risk with alginate | |||||

| Participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life (OHIP‐EDENT) Follow‐up: 6 months | Mean OHIP‐EDENT score 5.5 |

MD 0.5 higher (2.67 lower to 3.67 higher) | ‐ | 39 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 2 | |

| Participant‐reported quality of the denture: general satisfaction Follow‐up: 6 months | 25 per 1000 | 79 per 1000 (4 to 1000) | RR 3.15 (0.14 to 72.88) | 39 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 2 | |

| Number of border adjustments and sore spots after insertion of denture | Not measured | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio. ZoE: zinc‐oxide eugenol | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded for indirectness due to the single study with only 39 participants included in this trial. Therefore, it is difficult to generalise.

2 Downgraded twice for serious imprecision, small sample size and wide 95% CI.

Summary of findings 6. Removable partial dentures. Tooth‐tissue‐supported conditions: same material, different dual‐impression techniques.

| Altered cast compared with one‐piece cast (polyether) for final impression | ||||||

| Population: people requiring removable partial dentures Setting: university dental clinic Intervention: altered cast Comparison: one‐piece cast | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life | Not measured | |||||

| Participant‐reported quality of the denture: general satisfaction | The study reported that 50 of 57 participants were moderately to completely satisfied, with no significant difference between the groups. Data not reported separately for each group. | 57 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 2 | |||

| Number of intaglio adjustments Follow up: one year |

194 per 1000 | 278 per 1000 (119 to 649) |

RR 1.43 (0.61 to 3.34) |

72 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 2 3 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level as allocation concealment was unclear and there was a high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data and blinding of personnel

2 Downgraded one level as a single study contributed data for this outcome

3 Downgraded one level because 95% CI is wide

Background

Description of the condition

The increase in life expectancy in both high‐income and low‐income countries could result in the global population over 60 years of age surpassing two billion by 2050 (United Nations 2013). Edentulism is among the 50 most common diseases, affecting 2.3% of the total global population in 2010 (Vos 2012). The prevalence of partially and completely edentulous people is likely to increase, as the risk of tooth loss increases with age (Urzua 2012).

Complete edentulism is a chronic and irreversible condition, having a major impact on the oral and general health of an individual (Atwood 1971; Gift 1992). The global prevalence of complete edentulousness ranges from about 3% to 21%, and varies depending on age, sex, socioeconomic status, education, dental awareness, patient to dentist ratio, and demography (Cunha‐Cruz 2007; Peltzer 2014; Steele 2012). This condition affects diet and nutritional status (Hutton 2002; Lee 2004), and people who are edentulous may have comorbid conditions that make it difficult to adapt to complete dentures as they age (Emami 2013). The only cost‐effective, non‐implant treatment to restore dentition is complete dentures (MacEntee 1998). A complete denture is defined as "a fixed or removable dental prosthesis that replaces the entire dentition and associated structures of the maxillae or mandible" (GPT 2017).

Partial edentulousness is more prevalent than complete edentulousness (Jeyapalan 2015; Slade 2014; Tanasić 2015). Loss of teeth correlates with an increase in obesity and a decrease in nutritional status, psychological self‐image, and quality of life (Emami 2013; Friedman 2014; Gil‐Montoya 2015; Goel 2016; Hilgert 2009; Huang 2013; Hugo 2009; Kandelman 2008; Rodrigues 2012; Roohafza 2015). The partial loss of teeth may be replaced by fixed or removable treatment options based on number of teeth lost and condition of the residual ridge.

Description of the intervention

Complete dentures

A dental impression is defined as "a negative imprint or a positive digital image display of intraoral anatomy used to cast or print a 3D replica of the anatomic structure that is to be used as a permanent record or in the production of a dental restoration or prosthesis" (GPT 2017). Dental practitioners can make the impression in a single stage (abbreviated impression) or in two stages (preliminary impression made for the purposes of diagnosis, or for the construction of a tray, followed by final impression) (Trapozzano 1939). The final‐impression techniques and materials used for complete dentures date back to 1900s (Paulino 2015; Zinner 1981). They make the impression using an open‐mouth or closed‐mouth approach, in one or two steps (Boucher 1951). In the single‐step procedure, border moulding and recording the final impression are performed simultaneously, using the same material, either a resinous wax, or a monophase elastomer (Joglekar 1968; Loh 1997; Minagi 1987). The two‐step final‐impression technique begins with border moulding, followed by a final‐impression procedure (Chaffee 1999; Friedman 1957; Smith 1979). Border moulding is defined as "the shaping of impression material along the border areas of an impression tray by functional or manual manipulation of the soft tissues adjacent to the borders to duplicate the contour and size of the vestibule". It is also defined as determining the extension of a prosthesis, by using tissue function or manual manipulation of the tissues to shape the border area of an impression material (GPT 2017). It can be accomplished by using either a sectional or a single‐step technique, using different types of materials. These techniques may be further classified as operator‐manipulated, or functionally moulded, based on the condition of the ridge and operator's preference. In terms of materials, the sectional technique involves border moulding in sections using a low‐fusing impression compound (Friedman 1957). The single‐step border moulding technique uses polyether, and addition silicone of differing viscosities (Chaffee 1999; Smith 1979; Solomon 1973; Solomon 2011).

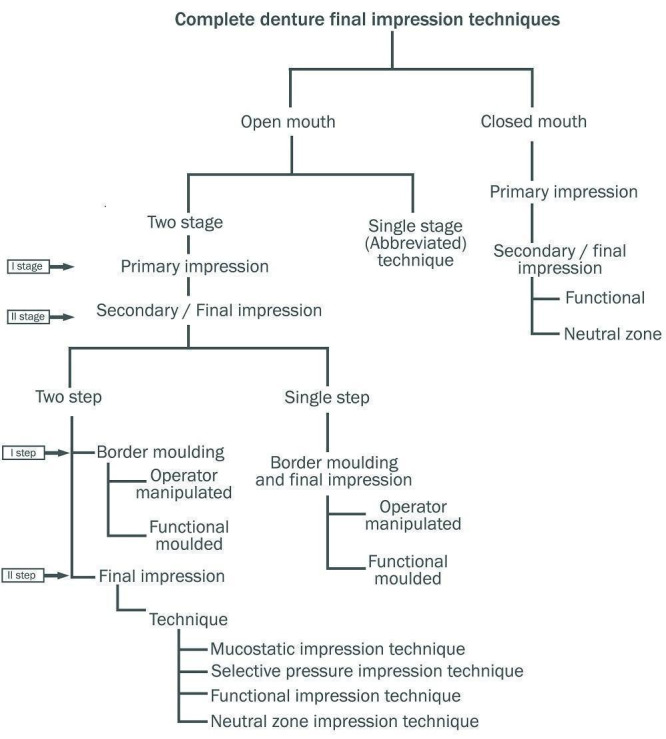

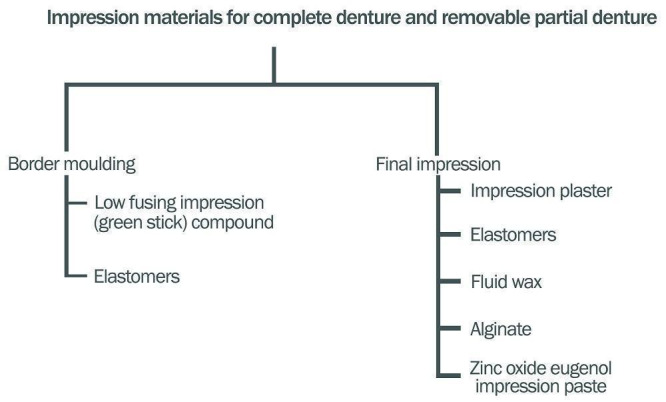

Clinicians can make the final impression (sometimes referred to as the wash impression) for complete dentures using different techniques and materials (Starcke 1975). These have evolved along with our understanding of the biology of the tissues, and advances in available impression materials. The techniques can be grouped into mucostatic, mucocompressive, selective pressure, functional, and neutral zone impression techniques (Addison 1944; Beresin 1976; Boucher 1943; Cagna 2009; Freeman 1969; Solomon 1973; (Figure 1)). The impression materials used are impression plaster, resinous wax, zinc‐oxide eugenol impression paste, alginate, polysulfide, addition silicone, and polyether (Boucher 1951; Daou 2010; Joglekar 1968; Koran 1977; Mehra 2014; Trapozzano 1939). See Figure 2.

1.

Complete denture final impression techniques (Al‐Ahmar 2008; Drago 2003; Freeman 1969; Paulino 2015; Petropoulos 2003)

2.

Impression materials for complete denture and removable partial denture (Freeman 1969; Phoenix 2008)

Removable partial dentures

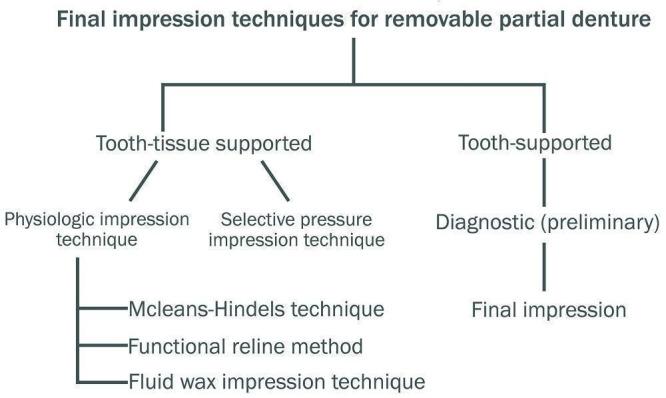

The distribution of occlusal forces varies, based on the condition of the partially edentulous state, in removable cast partial dentures (RPD). In a tooth‐supported partial denture, the occlusal forces are mainly distributed to the abutment teeth rather than the edentulous ridge, so the final impression is used to record the tissues in their anatomic state, in order to produce an accurate master cast (Applegate 1960; Leupold 1966). The materials and techniques used for recording the final impression in tooth‐supported conditions are alginates and elastomers, with either a custom or a stock tray. In tooth‐ and tissue‐supported partial dentures, a special or dual impression procedure is indicated, due to the relative discrepancy in the degree of movement that occurs between the tooth and mucosa covering the ridge, in response to occlusal forces (Hindels 1957). The different techniques are classified into physiologic and selective pressure impression techniques (Phoenix 2008). The physiologic impression techniques are the McLean‐Hindels technique, the functional reline method, and the fluid wax impression (altered cast) techniques (see Figure 3). In the selective pressure technique, the ridge is selectively relieved to redirect forces to stress‐bearing areas during impression making (Akerly 1978; Applegate 1937; Applegate 1960; Hindels 1957; Leupold 1965; McLean 1936; Sajjan 2010; Santana‐Penin 1998).

3.

Final impression techniques for removable partial denture (Phoenix 2008)

How the intervention might work

Complete dentures

The ultimate goal of the removable prosthesis is to maintain oral health, function, aesthetics, comfort, and psychological well‐being of the patient (Bell 1968). To achieve these goals, it is essential to obtain an accurate recording of the denture base foundation within functional and physiologically tolerable limits of the tissue (Drago 2003; El‐Khodary 1985; Massad 2005). Of the five cardinal objectives of an impression, the two main factors that prevent dislodgement of the dentures and increase chewing efficiency are retention and stability (Boucher 1944, Friedman 1957; Jacobson 1983a; Jacobson 1983b). Loss of these qualities lead to a decrease in denture efficiency, thereby reducing comfort, mastication, speech, self‐esteem, and patient satisfaction (Silva 2014). Retention and stability are directly related to a patient's compliance in wearing the dentures. Denture‐related problems can be due to patient‐ or dentist‐related factors, or processing errors (Critchlow 2011). Complaints about dentures are most often due to faulty design, so are dentist‐, rather than patient‐related (Brunello 1998; Laurina 2006). The most common denture‐related problems are insufficient retention and improper jaw relations; both are directly and indirectly related to the final‐impression technique, and the material used to make the dentures (Kotkin 1985).

Removable partial dentures

Cast partial removable dental prostheses are based on the theory of broad stress distribution, and aim to preserve the remaining dentition (DeVan 1952; Steffel 1951). In a distal extension, partially edentulous situation (tooth‐ and tissue‐supported conditions), a destructive class‐I lever is created, because of the compressibility of the mucosa of the edentulous ridge relative to the remaining tooth under occlusal load, which tends to overload the abutment tooth (Holmes 1965; Leupold 1966). The various dual final‐impression techniques used to make cast partial dentures and semi‐precision attachments, help reduce the transfer of excessive stress to the abutment tooth during occlusal loading, thereby improving support, and preserving the health of the remaining oral tissues (Blatterfein 1980; Leupold 1966). Hence, the choice of final‐impression material and technique is very important.

Why it is important to do this review

Treatment with complete or partial dentures involves multiple steps, some of which are crucial for success. One such step is the final‐impression procedure. Retention, stability, support, chewing efficiency, patient comfort, and overall satisfaction depend on the correct recording of the final impression during the making of complete and partial dentures (Cunha 2013). There are no evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines for the fabrication of removable dental prostheses to inform policy makers, healthcare providers, patients, or the public (Owen 2006). There are narrative reviews, but to date, no systematic review with meta‐analysis has provided evidence to guide the selection of one material, technique, or both, over another, for edentulous people (Carlsson 2013; Daou 2010; Rao 2010; Zinner 1981).

Objectives

To assess the effects of different final‐impression techniques and materials used to make complete dentures for retention, stability, comfort, and quality of life in completely edentulous people.

To assess the effects of different final‐impression techniques and materials used to make removable partial dentures for stability, comfort, overextension, and quality of life in partially edentulous people.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cross‐over trials in any language that dealt with impression making for both complete dentures and removable partial dentures.

Types of participants

Complete dentures

Participants who were completely edentulous, and had undergone treatment for complete dentures in both arches, regardless of age, sex, and socioeconomic status.

Participants with a complete denture in either the upper or lower jaw, if outcomes were reported for that particular arch.

We excluded participants with implant‐supported or retained prosthesis, as well as overdentures and immediate denture prosthesis.

Removable partial dentures

Participants who were partially edentulous, and required rehabilitation with permanent, removable, partial dentures for one or both arches.

We excluded participants with implant‐supported or retained dentures, with any form of intracoronal or extracoronal attachments, except Akers and bar clasp, transitional partial denture, treatment partial denture, temporary partials, overdenture, and immediate partial denture.

Types of interventions

We only considered the impression materials and prescribed technique(s) used for border moulding and final impression.

Complete dentures

Interventions that compared the following.

Same material using different techniques.

Same technique using different materials.

Different techniques using different materials.

Different techniques (comparisons 1 and 2)

single stage using one‐step final impression

two‐stage techniques using primary and final impression, either single‐step or two‐step

Different techniques (comparison 3)

different impression techniques for flabby ridge

different neutral zone techniques for resorbed ridge

any of the above techniques, and 1 and 2 done with different materials

Different final‐impression materials (comparisons 1, 2, and 3)

alginate

zinc‐oxide eugenol

elastomeric impression materials

impression plaster

green stick

fluid wax

Removable partial dentures

Interventions that compared the following.

-

Tooth‐supported conditions, using:

same material and different techniques;

same technique with different materials.

-

Tooth‐tissue‐supported conditions, using:

same material and different dual‐impression techniques;

different dual‐impression techniques with different materials.

Different types of final‐impression material

alginate

zinc‐oxide eugenol

elastomeric impression materials

green stick

fluid wax

impression plaster

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Complete dentures

Participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life, measured with any pre‐validated questionnaire (including all domains in the Oral Health Impact Profile Questionnaire (OHIP), OHIP in Edentulous Adults (OHIP‐EDENT), OHIP‐14, OHIP‐20, OHIP‐49, GOHAI (Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index)).

Participant‐reported quality of the denture assessment, measured by any pre‐validated questionnaire, including retention, stability, comfort, chewing ability, satisfaction, and denture dislodgement during function, for one or all of the factors.

Removable partial dentures

Participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life, measured with any pre‐validated questionnaire (including all domains in the OHIP, OHIP‐EDENT, OHIP‐14, OHIP‐20, OHIP‐49, GOHAI.

Participant‐reported quality of the denture assessment, measured by any pre‐validated questionnaire, including stability, comfort, chewing ability, satisfaction, and denture dislodgement during function, for one or all of the factors.

Secondary outcomes

Complete dentures

Number of border adjustments or sore spots, measured up to one month after insertion of dentures.

Denture base retention (movement), stability, and overextension, assessed quantitatively or qualitatively by a calibrated operator, up to one month after insertion.

Participant‐reported preference for any technique or material.

Dislodgement of the denture during function.

Removable partial dentures

Number of border and intaglio adjustments, measured up to one month after insertion of dentures. We did not include sore spots as an outcome for removable partial dentures, as this may occur due to other components of the partial dentures, such as poor design or placement of the components during fabrication, and are not always due to overextension of the borders of the dentures.

Number of years of service after which a reline was required.

Abutment mobility, gingival health, and denture base adaptation, assessed quantitatively by operators.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Oral Health’s Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials without language or publication status restrictions:

Cochrane Oral Health’s Trials Register (searched 22 November 2017) (Appendix 1);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; in the Cochrane Register of Studies, searched 22 November 2017) (Appendix 2);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 22 November 2017) (Appendix 3);

Embase Ovid (21 December 2015 to 22 November 2017) (Appendix 4).

Subject strategies were modelled on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE Ovid. Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Chapter 6 (Lefebvre 2011).

Due to the Cochrane Centralised Search Project to identify all clinical trials in the database and add them to CENTRAL, only the most recent months of the Embase database were searched. See the searching page on the Cochrane Oral Health website for more information. No other restrictions were placed on the date of publication when searching the electronic databases.

Searching other resources

We searched the following trial registries for ongoing studies:

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; searched 22 November 2017) (Appendix 5);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch; searched 22 November 2017) (Appendix 5).

We screened the references of included studies to identify additional records, and we checked any review articles for studies not identified by the above‐mentioned search strategy. We contacted authors of published papers for more information. We translated non‐English records, with help from translators identified through Cochrane Oral Health.

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of interventions used; we considered adverse effects described in included studies only.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We imported all the retrieved search results from the different databases to reference manager software, and removed duplicates. As a part of the data extraction process, two review authors (SJ and BPS) independently evaluated all retrieved studies by cross‐checking the title and abstract against the review inclusion and exclusion criteria. When the title or abstract did not clearly state the objectives, methods, and results, the authors retrieved the full text, along with additional information, if required. When multiple publications of one study were identified, we linked these under the same study identification. After initial screening, two review authors compared their selection of included studies and came to an agreement on ambiguous studies. When the review authors had a different opinion, the third and fourth authors (MPP and BR), and the methodologist (RK) were consulted, and arrived at a final agreement on the inclusion of the study. When one of the two screening authors was an author of a retrieved study, another author assessed its eligibility, to avoid bias. We explained the reasons for exclusion in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Data extraction and management

We generated a customised comprehensive data extraction form with the objectives of this review. We pilot tested the data form, extracting and recording the following information for included studies.

General information: study ID, name of the review author (extractor), details of the study authors, year and date, publisher, journal and study design.

Study eligibility: inclusion and exclusion criteria, interventions and comparators, types of outcomes.

Population and setting: population description, setting, methods of recruitment of participants.

Methods: aim of study, design, unit of allocation, date of the start and end of the trial, total study duration, ethical approval obtained.

Participants: total number randomised, baseline imbalance, withdrawals and exclusion, age, sex, type of ridge, comorbidities, other treatments received after intervention.

Intervention: number of groups, impression technique and materials used in intervention and control groups, if trialists performed facebow transfer, and the occlusal registration techniques and scheme. For cross‐over trials, we recorded the period of habituation prior to cross‐over.

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes, and the time points at which they were assessed.

Others: funding source, conflict of interest.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias of included studies for internal validity, as per Higgins 2011, in the following domains.

Sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation sequence concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome assessment (attrition bias).

Selective outcome reporting bias (reporting bias).

With cross‐over trials, if the design was suitable for the outcome, we did not consider the duration of washout because Hyde 2014 showed that there was no period effect or carry‐over effect in a randomised cross‐over denture trial. We accepted a minimum period of one to two weeks of habituation prior to cross‐over.

We graded the risk of bias as low, high, or unclear, based on pre‐set criteria presented in Appendix 6, conforming to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We created a 'Risk of bias' summary graph and figure, and we used our judgements to grade the overall quality of evidence for each comparison and outcome in the 'Summary of findings' tables. We contacted authors of the studies for clarification regarding the randomisation and allocation concealment domains. If the author did not respond, and the methods used were not clearly stated in the article, we assessed that study as being at unclear risk of bias. Two review authors (SJ and BPS) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies, and MPP checked all 'Risk of bias' assessments. We resolved any ambiguity through consensus among all authors.

Measures of treatment effect

When studies recorded outcomes as dichotomous data, we reported the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). When investigators reported outcomes as continuous data, we used the difference in means (MD) if the outcomes were measured on the same scale, and the standardised mean difference (SMD) if measured on a different scale, with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Unit of analysis issues

In parallel‐group trials, we considered the participant to be the unit for analysis. In multi‐arm trials, we had intended to combine similar arms where appropriate. For cross‐over trials, we analysed the data appropriately, taking into account the paired nature of the data (see Data synthesis section)

Dealing with missing data

We contacted some of the study authors, requesting they provide us with missing data. However, we were unsuccessful in getting the missing data. Therefore, when feasible, we estimated the missing data using results reported in the article, by following methods recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We analysed and investigated heterogeneity at three levels: clinical, methodological, and statistical. Heterogeneity due to clinical and methodological factors included age, trial type, outcomes measured, use of facebow, follow‐up, risk of bias, type or classification of the ridge, and other factors that arose after the analysis. For statistical heterogeneity, we checked the direction and magnitude of the effect, along with overlapping CI and point estimates.

We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the Chi² statistic, with a level of significance of 0.1 instead of 0.05. We used the I² statistic to quantify heterogeneity, according to Higgins 2011. The I² statistic indicates the degree of heterogeneity, and the value ranges from 0 to 100. A higher value indicates greater heterogeneity. A rough guide for interpretation of I² is: 0% to 40% ‐ might not be important; 30% to 60% ‐ may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% ‐ may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100% ‐ may represent considerable (very substantial) heterogeneity. When I² was higher than 60%, we investigated heterogeneity using a random‐effects model, or explored it using a subgroup analysis. When heterogeneity was higher than 80%, we did not pool data.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not use funnel plots to look for publication bias, as there were too few studies.

Data synthesis

We undertook data analysis using Review Manager 5 (RevMan), following the methods stated in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011; Review Manager 2014). When there was similarity across the participants, interventions, and outcomes, we performed a meta‐analysis. We combined MDs for continuous data (or SMDs for studies using different scales), and RRs for dichotomous data. Our general approach was to use a random‐effects model. With this approach, the CIs for the average intervention effect were wider than those obtained using a fixed‐effect model, leading to a more conservative interpretation.

We extracted appropriate data from the crossover trials (Elbourne 2002), and we used the generic inverse variance (GIV) method to enter log RR or mean differences and their respective standard errors into RevMan. For cross‐over studies, we intended to use the Becker‐Balagtas method (BB OR) to calculate log odds ratios (ORs), as indicated by Curtin 2002 to accommodate data pooling from cross‐over and parallel‐group studies in a single meta‐analyses, and facilitate data synthesis; however, we did not meta‐analyse any dichotomous data (see Stedman 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had planned the following subgroup analyses for complete dentures, but we were only able to conduct the analysis by trial type.

Use of a facebow transfer with semi‐adjustable articulator during complete dentures treatment.

Types of ridges (we grouped them using American College of Prosthodontics (ACP) classification I and II versus III and IV, or Atwoods classification above order III versus below order III).

Performance of intervention on a single arch or on both arches, for the primary outcomes.

Trial type.

Sensitivity analysis

As there were inadequate data, we did not perform any of the sensitivity analyses we had planned in order to evaluate the robustness of the pooled estimate.

Summarising findings

We generated 'Summary of findings' tables for comparisons 1, 2, and 3. Comparison 3 compared the most widely and commonly used technique and material in the fabrication of complete dentures. We summarised the findings for our key outcomes: participant‐reported quality of life, participant‐reported quality of the denture, and number of border adjustments and sore spots after insertion of the denture. We did not generate a 'Summary of findings' table for removable partial dentures.

We assessed the quality of the evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low, in accordance with section 11.5 of Higgins 2011, using GRADE methods and the GRADEPro software package (GRADE 2004; GRADEpro 2015). We graded the body of evidence based on the risk of bias of included studies, indirectness of the evidence, inconsistency between results, imprecision of measure of effects, and publication bias. We provided a citation and rationale for the figure we used to calculate the assumed risk.

Results

Description of studies

See the 'Characteristics of included studies' and 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables.

Results of the search

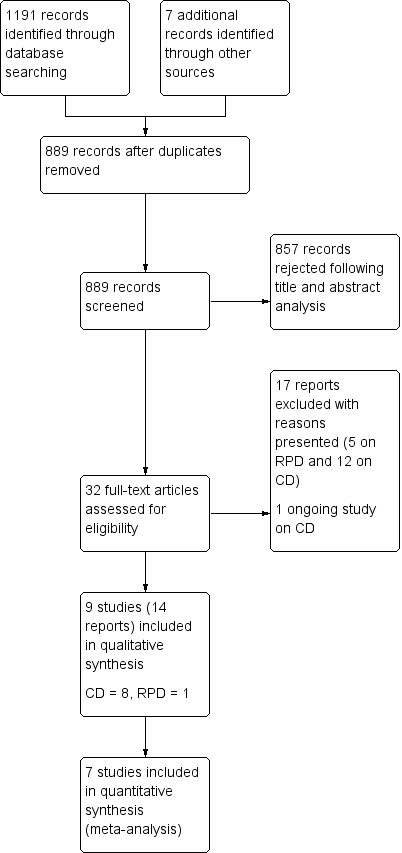

The search of electronic databases yielded a total of 1191 records, and we identified seven additional records from other sources. After we removed duplicates, we had 889 records remaining. We screened the titles and abstracts of these records, and rejected 857 records. We assessed 32 full‐text reports for eligibility. We excluded 17 reports (12 on complete dentures (CD); five on removable partial dentures (RPD)). We listed the reasons for exclusion in Characteristics of excluded studies. There is one ongoing study on CD (NCT02339194). We included nine studies in 14 reports: eight studies on CD (Firtell 1992; Hyde 2010; Hyde 2014; Jo 2015; Kawai 2005; Matsuda 2015; Nunez 2015; Regis 2013), and one study on RPD (Frank 2004). We present the study selection process in Figure 4.

4.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

Complete dentures

Characteristics of trial setting and design

Location

Of the eight studies on complete dentures we included in the review, two were conducted in Japan (Jo 2015; Matsuda 2015), two in Brazil (Nunez 2015; Regis 2013), two in the UK (Hyde 2010; Hyde 2014), one in Canada (Kawai 2005), and one in the USA (Firtell 1992). The setting for seven studies was a dental school, or university hospital, and one study was conducted in a general hospital in Canada.

Design

Four trials had a two‐arm, parallel‐group design (Firtell 1992; Kawai 2005; Nunez 2015; Regis 2013) and three studies had a two‐arm, cross‐over design (Hyde 2014; Jo 2015; Matsuda 2015). The final study, Hyde 2010, had a three‐arm, cross‐over design, but only one outcome (denture preference) was measured based on the randomisation of participants to the three arms. The study's other outcomes were assessed after participants had chosen which of the dentures they preferred and had worn them for three months; as these measurements were not based on a randomised comparison, we did not include these data.

Duration

Trial length varied from 1.2 to 2.9 years; one study stated only the enrolment period (0.7 years; (Regis 2013)); and one study did not state the trial duration (Firtell 1992).

Funding

Only one trial did not specify any funding source (Firtell 1992). Hyde 2010 was funded by a grant from the Dunhill Medical Trust; Hyde 2014 was funded by a NIHR‐RfPB (National Institute of Health ‐ Research for Patient Benefit grant); Jo 2015 was supported by the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science; Kawai 2005 by the Nihon University Grant for Overseas Research and the Suzuki Memorial Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Matsuda 2015 was supported by the research fund of Osaka University Graduate School of Dentistry, where both of the authors (K Mastudaand, Y Maeda) are remunerated instructors, who had given educational lectures at the request of the Ivoclar Vivadent company, and who conducted and supervised the study; Nunez 2015 was supported by a grant from the Brazilian National Research Council and State Foundation Research of Goias; and Regis 2013 was funded by a FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo) grant.

A priori sample size calculation

Of the eight studies included, five trials reported sample size with 80% power estimates (Hyde 2014; Jo 2015; Kawai 2005; Nunez 2015; Regis 2013); in one pilot study no sample size calculation was done (Matsuda 2015); one study did not report clearly (Hyde 2010); and one study did not report sample size (Firtell 1992). The sample size of the studies varied from 10 (Matsuda 2015) to 122 (Kawai 2005).

A total of 435 participants were randomised from eight trials, with a mean of 54.3 participants per trial, and a range of 10 to 122. The participants were both male and female, who were edentulous in the upper and lower arch. The average age of the participants ranged from 45 to 75 years. Three studies reported the period of edentulousness, which ranged from 10 to 35 years (Kawai 2005; Nunez 2015; Regis 2013). Three studies reported patient classification based on American College of Prosthodontics classification for completely edentulous patients, and found about 60% to 75% of ACP‐III and ACP–IV in both groups (Jo 2015; Kawai 2005; Regis 2013). Three studies did not report demographic details of participants (Firtell 1992; Hyde 2010; Hyde 2014). The other studies reported demographic details, which were balanced at baseline. Most studies excluded people with temporomandibular disorders, psychological disorders, allergies to acrylic or silicone, dysfunction disorders of the masticatory system, debilitating systemic disease or oral mucosal disease, and decline in cognitive function.

Characteristics of the intervention

Comparison 1: same material and different techniques

We found two studies for the Comparsion 1, comparing same material and different techniques (Hyde 2010; Matsuda 2015).

One study (pilot) compared open versus closed mouth/two stage‐two step silicone elastomers (Matsuda 2015). In Group 1, Biofunctional Prosthetic System CD fabrication method (BPS) preliminary impression (Accu‐dent System I) was made using irreversible hydrocolloid as tray and syringe material. The custom trays were fabricated using Gnathometer‐M tracing and final impressions were made in 'mouth‐closed' position with both light‐ and heavy‐body vinyl polysiloxane impression material. In Group 2, the conventional CD fabrication method, the preliminary impression was made with irreversible hydrocolloid impression material with a stock metal tray. The final impression was made with a custom tray, border moulded with impression compound and made with hydrophilic vinyl polysiloxane impression material, which was same for both groups. The other differences between the two intervention arms (co‐intervention) were that jaw relation was taken as tentative along with the primary impression and second jaw relation with vertical maxillomandibular relationship and horizontal relation recorded using Gnathometer‐M intraoral gothic arch tracing device with a silicone bite registration paste. Hence the BPS method had one less step than the conventional method of denture fabrication.

One study was a cross‐over, three‐arm trial (Hyde 2010). For all groups, the preliminary impression was made with irreversible hydrocolloid using a stock tray (different two stage‐two step techniques with silicone). Final impression in the control group was done with standard technique using wax relief on a custom tray, making a relatively mucostatic impression. The second intervention was traditional technique (redistributing pressure) using tin foil of 0.6 mm on the primary cast while making a custom tray. The third intervention was selective pressure impression technique, which involves placing relief holes on the tray after removing impression material over mental foramen before final impression. All impressions were taken with medium‐bodied silicone material followed by a light‐bodied silicone final impression.

Comparison 2: same technique and different materials

We identified two trials comparing same technique with different materials (Firtell 1992; Hyde 2014).

Firtell 1992 compared two stage‐two step/wax versus polysulfide. This was a two‐arm, parallel‐group trial in which a stock metal tray with irreversible hydrocolloid was used for preliminary impression. A custom tray was made and border moulding with green stick moulding compound and relieved for open‐mouth selective pressure final impression either with fluid wax (Group 1) or polysulfide impression material (Group 2) .

In Hyde 2014, which was a two‐arm, cross‐over trial of two stage‐two step/alginate versus silicone, preliminary impression was made with alginate impression material in a stock metal tray. One group used alginate as final impression after border moulding with green stick and the other group used heavy body for upper and light body for lower border moulding and final impression was made with silicone. All other procedures were the same until the insertion of denture. Washout period was eliminated by using a novel habituation period of wearing unadjusted dentures for two weeks.

Comparison 3: different techniques and different materials

We found four studies using different materials with different techniques (Jo 2015; Kawai 2005; Nunez 2015; Regis 2013).

In Jo 2015, the only difference between the two interventions was at the impression stage: the simplified method of fabricating complete dentures used alginate (single‐stage impression with alginate versus two stage‐two step silicone) and the conventional method used border moulding with green stick and silicone final impression. All clinical and lab phases of denture fabrication were the same until denture insertion. Washout period was one month and relined old denture was used during the washout period. No co‐intervention was used.

Kawai 2005 employed a simplified procedure of denture fabrication using (single‐stage) alginate impression material with a stock metal tray. The traditional/conventional method (two stage‐two step) used preliminary alginate impression with a stock metal tray. The final impression was made with a custom tray, border moulded with impression compound and final impression with polyether rubber impression material. The traditional procedure used the co‐intervention of facebow, semi‐adjustable articulator and remount procedure than simplified procedure until denture insertion.

In Nunez 2015, a two‐arm, parallel‐group study, the simplified procedure of denture fabrication used (single‐stage) alginate impression materials with a stock metal tray. The traditional/conventional method (two stage‐two step) used preliminary alginate impression with a stock metal tray. The final impression was made with a custom tray, border moulded with impression compound and polysulfide impression material (elastomer). The traditional procedure used the co‐intervention of facebow, but both methods used average setting on semi‐adjustable articulator and no remount procedure than simplified procedure until denture insertion.

In Regis 2013, a two‐arm, parallel‐group study, the simplified procedure of denture fabrication used (single‐stage) alginate impression materials with a stock metal tray. The traditional/conventional method (two stage‐two step) used preliminary alginate impression with a stock metal tray. The final impression was made with a custom tray, border moulded with impression compound and final impression with zinc‐oxide eugenol impression paste. The traditional procedure also used the co‐intervention of facebow and two try‐in steps, but both methods used an average setting on semi‐adjustable articulator and no remount procedure compared to simplified procedure until denture insertion.

Impression materials for complete denture

One study used wax (Firtell 1992); all eight studies used elastomers as final‐impression material, either polysulfide, polyether or addition silicone (Firtell 1992; Frank 2004; Hyde 2010; Hyde 2014; Jo 2015; Kawai 2005; Matsuda 2015; Nunez 2015); and five studies used alginate as final‐impression material (Hyde 2014; Kawai 2005; Nunez 2015; Regis 2013; Jo 2015). Only one trial used zinc‐oxide eugenol (Regis 2013), and no study used impression plaster as final‐impression material.

Characteristics of outcome assessments

The primary outcomes in our review were participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life (OHRQoL; using the OHIP, OHIP‐EDENT, OHIP 14, OHIP 20, OHIP 49, and the GOHAI questionnaires), and participant‐reported quality of the denture assessment for retention, stability, comfort, chewing and masticatory ability, satisfaction, and denture dislodgement during function.

All studies published after 2010 assessed OHRQoL using the OHIP‐EDENT questionnaire as one of the main outcomes (Hyde 2010; Hyde 2014; Jo 2015; Matsuda 2015; Nunez 2015).

Five studies evaluated participant‐rated general satisfaction with the new dentures using a 100‐mm or a 10‐point visual analogue scale (VAS) (Jo 2015; Kawai 2005; Matsuda 2015; Nunez 2015; Regis 2013).

Five studies assessed participant‐rated comfort, stability, aesthetics, ability to speak, ease of cleaning, and masticatory ability on 10‐point VAS or 5‐point Likert Scale (Hyde 2010; Hyde 2014; Kawai 2005; Nunez 2015), or qualitatively (Matsuda 2015).

Two studies reported the number of adjustments required post denture insertion (Firtell 1992; Matsuda 2015).

Three studies assessed participants' preference for dentures (Hyde 2010; Hyde 2014; Matsuda 2015).

Two trials reported operator‐rated quality of denture (Regis 2013; Kawai 2005).

Some outcomes in Firtell 1992 were measured but not reported.

From Hyde 2010, we used only the data for our secondary outcome 'denture preference' as the measurement of the other outcomes was not based on a randomised comparison.

Duration of follow‐up

Duration of follow‐up varied from 24 hours to one year. See Table 7 for details.

1. Outcomes and follow‐up times.

| Outcomes | 24 hours | One week | Two weeks | One month | Three months | Six months | One year |

| Participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life (OHIP‐EDENT) | Hyde 2014 |

Jo 2015; Nunez 2015 |

Matsuda 2015; Hyde 2010; Regis 2013 |

Nunez 2015; Regis 2013 |

|||

| Participant‐reported quality of the denture, for satisfaction, comfort, masticatory ability and speech | Hyde 2014 | Nunez 2015 |

Matsuda 2015; Kawai 2005 |

Nunez 2015; Kawai 2005 |

|||

| Number of denture adjustments required post insertion | Firtell 1992 | Firtell 1992 | Matsuda 2015 | Firtell 1992 | |||

| Operator‐reported quality of the denture | Regis 2013 |

Regis 2013; Kawai 2005 |

|||||

| Participant preference for dentures (impression material and technique) | Hyde 2014 | Jo 2015; Hyde 2010 | Matsuda 2015 |

Removable partial dentures (RPD)

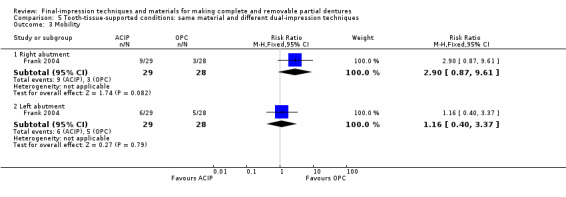

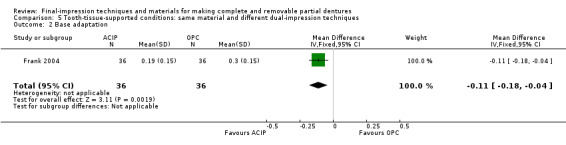

We included one parallel‐group, arm trial on RPD for tooth‐tissue‐supported conditions, which compared same material and different dual‐impression techniques (Frank 2004). It was conducted at University of Washington, Seattle, USA. Recruitment period and funding source were not mentioned in the study.

Characteristics of participants

They recruited participants from those undergoing routine prosthodontic treatment at the pre‐doctoral patient pool at the University of Washington. Patients requiring mandibular Kennedy Class‐1 RPD with at least one indirect retainer on premolar or canine were included in the study and no exclusion criteria were stated.

Characteristics of the intervention

The study compared an altered‐cast technique, in which the framework was fabricated after the impression of distal extension and made in the laboratory versus a one‐piece cast, in which the framework was fabricated and checked for fit intraorally. The preliminary impression with a stock tray, and final impression with an auto‐polymerising resin custom tray, were made with a standardised mixture of equal parts of light‐body and medium‐body polyether for both groups.

Characteristics of the outcomes

They measured under and over extension, base movement, adaptation of the denture base, gingival sulcus depth, mobility, gingival index of direct retainer abutment, resorption, tissue quality of the edentulous ridge, participant‐reported general satisfaction, most liked, and most disliked feature of the removable partial dentures.

Excluded studies

We reported the reasons for excluding studies in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. We excluded 17 articles (12 on CD and five on RPD). In CD, three studies evaluated denture bases mounted on cast (Adnan 2010; Al‐Judy 2015; Birtles 2015); two studies compared the same material and technique for both groups (Heydecke 2008; Nascimento 2004); one study evaluated mandibular dentures only (McCord 2005); one study was quasi‐randomised (Sharif 2013); one study was not an RCT (Tasleem 2013); two study compared relining material (Wegner 2011; DRKS00000149); and two were ongoing studies evaluating polyamide (NCT03043456; NCT03234803). We excluded five reports on RPD: two studies compared two different types of prostheses (Au 2000; Hundal 2015); one was not randomised (Hochman 1998); one was an ongoing study evaluating polyamide and polyetheretheketone (NCT03025555) and one had removable partial against complete denture (RBR‐8fs5ww).

Ongoing studies

We identified one relevant ongoing study: NCT02339194. See the 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' table.

Risk of bias in included studies

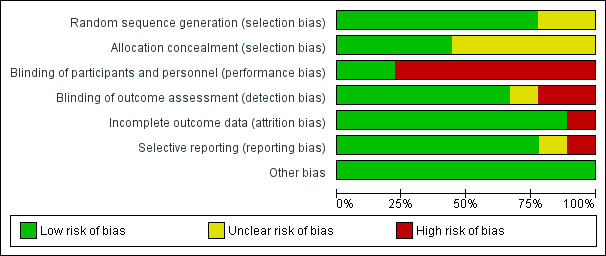

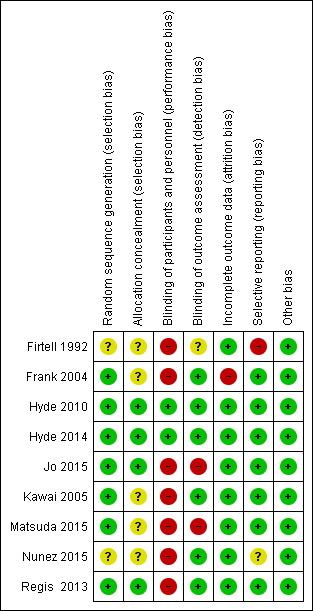

We assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. For CD studies, we judged six studies to be at high risk of bias (Firtell 1992; Jo 2015; Kawai 2005; Matsuda 2015; Nunez 2015; Regis 2013), and two to be at low risk of bias (Hyde 2010; Hyde 2014). For RPD, we judged the one study to be at high risk of bias (Frank 2004). See Figure 5 and Figure 6.

5.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' domain, presented as percentages across all included studies

6.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' domain for each included study

Allocation

Complete dentures

We assessed the method for random sequence generation as low risk of bias for six studies that reported computer‐generated random sequence (Hyde 2010; Hyde 2014; Jo 2015; Kawai 2005; Matsuda 2015; Regis 2013) and as unclear for two studies (Firtell 1992; Nunez 2015). We assessed the concealment of allocation as low risk of bias for four studies (Hyde 2010; Hyde 2014; Jo 2015; Regis 2013), and as unclear for four studies (Firtell 1992; Kawai 2005; Matsuda 2015; Nunez 2015).

Removable partial dentures

We assessed Frank 2004 as low risk of bias for random sequence generation and unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment.

Blinding

Complete dentures

We assessed the blinding of participants and personnel as low risk of bias for Hyde 2010 and Hyde 2014 because randomisation was done only at the delivery of dentures, followed by adjustment of the dentures. We assessed six studies as high risk of bias as it was not possible to blind the operator in these trials (Firtell 1992; Jo 2015; Kawai 2005; Matsuda 2015; Nunez 2015; Regis 2013).

We assessed the blinding of outcome assessment as low risk of bias for five studies (Hyde 2010; Hyde 2014; Kawai 2005; Nunez 2015; Regis 2013). We assessed it as high risk of bias for two studies, one did not blind the outcome assessor (Jo 2015), and in other, the same resident dentists operated and evaluated the outcomes for each participant (Matsuda 2015). Firtell 1992 was at unclear risk of bias as it did not describe blinding.

Removable partial dentures

We assessed blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) in Frank 2004 as high risk of bias as it is not possible to blind the operator and blinding of participants was not reported. We assessed the blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) as low risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Complete dentures

We assessed incomplete outcome data for all eight studies as low risk of bias.

Removable partial dentures

We assessed Frank 2004 as high risk of attrition bias as loss to follow‐up was 19 participants at one year (15.1%).

Selective reporting

Complete dentures

We assessed six studies as low risk of reporting bias (Hyde 2010; Hyde 2014; Jo 2015; Kawai 2005; Matsuda 2015; Regis 2013); one study as unclear risk of bias, as it did not report general satisfaction of the denture but reported maxillary and mandibular denture satisfaction separately (Nunez 2015); and one study as high risk of bias, as it reported only denture adjustment, and other outcomes were not reported (Firtell 1992).

Removable partial dentures

We assessed Frank 2004 as low risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

No other potential sources of bias were found.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6

Complete dentures

Comparison 1 (same material and different techniques)

Closed mouth two stage‐two step with addition silicone elastomer (Biofunctional Prosthetic System (BPS)) versus open mouth two stage‐two step conventional technique (CCD) using elastomer

This comparison was assessed in one very small study (10 participants), which was at high risk of bias (Matsuda 2015). Although both interventions used a similar material for the final impression, they differed in impression technique, jaw registration methods, type of teeth, and occlusal scheme. Data were taken directly from the paper. See Table 1.

Primary outcomes

At three months, Matsuda 2015 measured participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life, using the OHIP‐EDENT‐J. The median OHIP‐EDENT‐J score was 34.5 for the BPS group and 35.8 for the CCD group.

For participant‐reported denture satisfaction, assessed using a 100‐mm VAS, the median score was 86.5 for the BPS group and 88 for the CCD group.

There was very low‐quality evidence of no clear difference between groups for either outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Matsuda 2015 reported that the median number of denture adjustments was 3.5 for the BPS group and 4.5 for the CCD group at three months.

When participants were asked which denture they would prefer to use long term, nine out of 10 opted for the one made with the BPS complete denture technique.

Denture base retention and dislodgement of the denture during function were not measured.

Two stage–two step with addition silicone elastomer impression material : selective pressure technique versus traditional technique (redistributing pressure) versus a control (placebo) technique (relatively mucostatic standard impression procedure)

Hyde 2010 compared these three techniques, analysing 69 participants. No cointerventions were given to either group after the final impression.

Primary outcomes

Participant‐reported quality of life was measured but it was based on an assessment of dentures participants had chosen, therefore it was not a randomised comparison. Quality of the dentures was not assessed.

Secondary outcomes

The study assessed participant preference for dentures at four to five weeks. Participants were more likely to prefer dentures made using the selective pressure technique over dentures made in the traditional method or using a control technique (33 participants chose dentures made using the selective pressure technique, 19 chose the traditionally‐made denture and 14 chose the control denture). There was no clear preference between the traditional and control denture groups.

This study did not measure the number of adjustments, denture base retention, or dislodgement of the denture during function.

Comparison 2 (same technique and different materials)

Two stage–two step selective pressure final‐impression technique using wax versus polysulfide elastomeric impression material

One study at high risk of bias evaluated this comparison and provided very low‐quality evidence for the outcomes (Firtell 1992; 27 participants; Table 2).

Primary outcomes

Neither of the primary outcomes were reported in this study.

Secondary outcomes

There was no evidence of a clear difference in the need for denture adjustments over one year of follow‐up between the wax and polysulfide groups (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.70; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Same technique, different materials: wax versus rubber, Outcome 1 Need for adjustments.

Firtell 1992 did not measure denture base retention, participant‐reported preference, or dislodgement of the denture during function.

Two stage‐two step (alginate versus silicone elastomers)

One study at low risk of bias evaluated this comparison. Hyde 2014 compared an alginate final impression after border moulding with green stick, and a light‐body silicone final impression after border moulding with heavy‐ and regular‐body silicone. This was the only study to use alginate for the final impression (wash impression). Seventy‐eight out of 85 participants completed the trial. None of the participants received any cointerventions.

Primary outcomes

Participant‐reported oral health‐related quality of life was measured at two weeks using the OHIP‐EDENT. Low‐quality evidence favoured silicone (MD 7.20, 95% CI 2.71 to 11.69; 144 participants; Analysis 2.1; Table 3). The difference between the groups was more than six units, which is the minimally clinical important difference for the OHIP‐EDENT, although the 95% confidence interval included scores under six units (John 2009).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Same technique, different materials: alginate versus silicone, Outcome 1 Oral health‐related quality of life (OHIP edent score).

Participant‐reported quality of the dentures was assessed using 5‐point Likert scales after two weeks of confirmation, for comfort, stability, and chewing efficiency. There was no evidence of a clear difference for comfort, but more participants favoured silicone for stability and chewing efficiency. These data were not amenable to meta‐analysis.

Secondary outcomes

There was evidence that one material was preferred over another after two weeks (confirmation period): silicone impressions 57.7% (41 participants), and alginate impressions 23.9% (17 participants). Both dentures were equally satisfactory for seven participants (9.9%) and equally unsatisfactory for six participants (8.5%) (McNemar chi‐square 12.02, 1 df, P = 0.0005).

They did not measure number of adjustments, denture base retention, or dislodgement of the denture during function.

Comparison 3 (different techniques and different materials)

Four trials (all at high risk of bias) addressed this comparison (Jo 2015; Kawai 2005; Nunez 2015; Regis 2013).

Single‐stage alginate (simplified method) versus two stage‐two step elastomer (silicone, polysulfide, or polyether) conventional method

Three studies compared simplified (alginate) and conventional methods of fabricating dentures with a silicone final impression and no cointervention (Jo 2015), a polyether cointervention of facebow transfer (Kawai 2005), and a polysulfide cointervention of facebow transfer (Nunez 2015).

Primary outcomes