Abstract

Background

Outcome after spontaneous (non‐traumatic) intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) is influenced by haematoma volume; up to one‐third of ICHs enlarge within 24 hours of onset. Early haemostatic therapy might improve outcome by limiting haematoma growth. This is an update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2006, and last updated in 2009.

Objectives

To examine 1) the effectiveness and safety of individual classes of haemostatic therapies, compared against placebo or open control, in adults with acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage, and 2) the effects of each class of haemostatic therapy according to the type of antithrombotic drug taken immediately before ICH onset (i.e. anticoagulant, antiplatelet, or none).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Trials Register, CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 11, MEDLINE Ovid, and Embase Ovid on 27 November 2017. In an effort to identify further published, ongoing, and unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCT), we scanned bibliographies of relevant articles and searched international registers of RCTs in November 2017.

Selection criteria

We sought randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of any haemostatic intervention (i.e. pro‐coagulant treatments such as coagulation factors, antifibrinolytic drugs, or platelet transfusion) for acute spontaneous ICH, compared with placebo, open control, or an active comparator, reporting relevant clinical outcome measures.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently extracted data, assessed risk of bias, and contacted corresponding authors of eligible RCTs for specific data if they were not provided in the published report of an RCT.

Main results

We included 12 RCTs involving 1732 participants. There were seven RCTs of blood clotting factors versus placebo or open control involving 1480 participants, three RCTs of antifibrinolytic drugs versus placebo or open control involving 57 participants, one RCT of platelet transfusion versus open control involving 190 participants, and one RCT of blood clotting factors versus fresh frozen plasma involving five participants. We were unable to include two eligible RCTs because they presented aggregate data for adults with ICH and other types of intracranial haemorrhage. We identified 10 ongoing RCTs. Across all seven criteria in the 12 included RCTs, the risk of bias was unclear in 37 (44%), high in 16 (19%), and low in 31 (37%). Only one RCT was at low risk of bias in all criteria.

In one RCT of platelet transfusion versus open control for acute spontaneous ICH associated with antiplatelet drug use, there was a significant increase in death or dependence (modified Rankin Scale score 4 to 6) at day 90 (70/97 versus 52/93; risk ratio (RR) 1.29, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.04 to 1.61, one trial, 190 participants, moderate‐quality evidence). All findings were non‐significant for blood clotting factors versus placebo or open control for acute spontaneous ICH with or without surgery (moderate‐quality evidence), for antifibrinolytic drugs versus placebo (moderate‐quality evidence) or open control for acute spontaneous ICH (moderate‐quality evidence), and for clotting factors versus fresh frozen plasma for acute spontaneous ICH associated with anticoagulant drug use (no evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Based on moderate‐quality evidence from one trial, platelet transfusion seems hazardous in comparison to standard care for adults with antiplatelet‐associated ICH.

We were unable to draw firm conclusions about the efficacy and safety of blood clotting factors for acute spontaneous ICH with or without surgery, antifibrinolytic drugs for acute spontaneous ICH, and clotting factors versus fresh frozen plasma for acute spontaneous ICH associated with anticoagulant drug use.

Further RCTs are warranted, and we await the results of the 10 ongoing RCTs with interest.

Plain language summary

Treatments to help blood clotting to improve the recovery of adults with stroke due to bleeding in the brain

Review question

Do treatments to help blood clot reduce the risk of death and disability for adults with stroke due to bleeding in the brain?

Background

More than one‐tenth of all strokes are caused by bleeding in the brain (known as brain haemorrhage). The bigger the haemorrhage, the more likely it is to be fatal. Roughly one‐third of brain haemorrhages enlarge significantly within the first 24 hours. Therefore, treatments that promote blood clotting might reduce the risk of death or being disabled after brain haemorrhage by limiting its growth, if given soon after the bleeding starts. However, haemostatic drugs might cause unwanted clotting, leading to unwanted side effects, such as heart attacks and clots in leg veins.

Study characteristics

We found 12 randomised controlled trials, including 1732 participants, up to November 2017.

Key results

We found moderate‐quality evidence of harm from platelet transfusion for people who had used antiplatelet drugs until they had a brain haemorrhage. We found no evidence of either benefit or harm from other haemostatic therapies for people with brain haemorrhage.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the quality of the evidence was moderate to low.

More information will become available from the 10 trials that are ongoing.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The burden of haemorrhagic stroke is out of proportion to its frequency as a subtype of stroke. Although haemorrhagic stroke causes 11% to 22% of all new strokes (Feigin 2009), it caused 50% of all stroke deaths, and approximately 42% (47 million) of the disability‐adjusted life years lost due to stroke in the 2013 Global Burden of Disease study (Feigin 2015). Spontaneous (non‐traumatic) intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) accounts for two‐thirds of haemorrhagic stroke, amounting to more than two million strokes per year (Al‐Shahi Salman 2009a). ICH is due to cerebral small vessel disease, and may be associated with the use of antithrombotic (i.e. anticoagulant or antiplatelet) drugs. The age‐specific incidence of ICH – like the age‐specific incidence of ischaemic stroke and myocardial infarction – rises with age (Feigin 2015). Two‐thirds of people who have an ICH are 75 years or older (Lovelock 2007; Samarasekera 2015). Given that the number of people aged 75 years and older is projected to rise in many parts of the world, the burden due to ICH incidence, recurrence, and prevalence will rise.

Outcome after stroke due to ICH is poor: one‐year survival is 46% (95% confidence interval (CI) 43% to 49%), five‐year survival is 29% (95% CI 26% to 33%), and predictors most consistently associated with death are increasing age, decreasing Glasgow Coma Scale score, increasing ICH volume, presence of intraventricular haemorrhage, and deep or infratentorial ICH location (Poon 2014). Approximately one‐third of acute ICHs (i.e. less than 24 hours after symptom onset or time last seen well) enlarge from three to 24 hours after onset (Brott 1997); ICH growth is independently associated with death and poor outcome (Davis 2006).

Description of the intervention

The three main components of haemostasis (the process that stops bleeding) are vasoconstriction, platelet plug formation, and coagulation.

Vascular smooth muscle cell vasoconstriction is a blood vessel's first response to injury. They constrict the damaged vessels, which reduces the amount of blood flow through the area and limits the amount of blood loss. Collagen is exposed at the site of injury, which causes platelets to adhere to the injury site.

Primary haemostasis is achieved by platelets, which adhere to damaged endothelium to form a platelet plug. Plug formation is activated by the Von Willebrand factor, which is found in plasma. When platelets are activated, they express glycoprotein receptors that interact with other platelets, producing aggregation and adhesion. Platelets release cytoplasmic granules that contain serotonin, adenosine diphosphate (ADP), and thromboxane A2, all of which increase the effect of vasoconstriction. ADP attracts more platelets to the affected area, serotonin is a vasoconstrictor, and thromboxane A2 assists in platelet aggregation, vasoconstriction, and degranulation.

Secondary haemostasis starts once a platelet plug has been formed. Blood plasma clotting factors are activated in a sequence of events known as the coagulation cascade. Inactive fibrinogen produces a fibrin mesh around the platelet plug to hold it in place. Red and white blood cells are trapped in the mesh to produce a thrombus, or clot. Tissue factor (also called platelet tissue factor, factor III, or thromboplastin) is a protein that is exposed after endothelial damage, which leads to thrombin formation and activation of the tissue factor pathway, as well as its circulating ligand factor VII.

Therapies that intervene in primary haemostasis (e.g. platelet transfusion) or secondary haemostasis (e.g. administration of clotting factors (fresh frozen plasma (FFP), or prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC), or antifibrinolytic drugs) might promote clot formation, decrease bleeding, and thus improve outcomes by limiting ICH growth.

How the intervention might work

Theoretically, early interventions to reduce acute ICH volume might improve outcomes. Although surgical craniotomy to evacuate spontaneous supratentorial ICH and reduce ICH volume was found to reduce the odds of dying or becoming dependent compared with medical management alone, the result was not very robust, and surgical evacuation is not frequently used (Prasad 2008). Therefore, medical (non‐surgical) interventions to promote haemostasis, and limit haematoma growth, have become the main focus of acute ICH therapeutic research.

Why it is important to do this review

Various haemostatic therapies have been investigated in a variety of spontaneous bleeding conditions with little evidence for their effectiveness in some settings (Johansen 2015: Stanworth 2012; Wikkelsø 2013), but clear benefit in others (Ker 2015). It is unclear whether they are effective for acute ICH. Therefore, we systematically reviewed the literature for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of all potential haemostatic therapies for the treatment of acute spontaneous ICH.

Objectives

To examine 1) the effectiveness and safety of individual classes of haemostatic therapies, compared against placebo or open control, in adults with acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH), and 2) the effects of each class of haemostatic therapy according to the type of antithrombotic drug taken immediately before ICH onset (i.e. anticoagulant, antiplatelet, or none).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials, whether published or unpublished, regardless of the language of publication. Pseudo‐randomised studies were not eligible.

Types of participants

People of any sex, aged 16 years or older. We restricted this review to people with radiographically‐confirmed acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH). Where possible, we grouped RCTs, or participant subgroups, by whether ICH was associated with antiplatelet drug use, anticoagulant drug use, or neither.

Types of interventions

Single or multiple haemostatic therapies (including antifibrinolytic drugs, blood coagulation factors, antidotes to specific antithrombotic drugs, platelet transfusion, or other platelet activation therapies), regardless of dosage or route of administration. Interventions could be compared against placebo, open control, or an active comparator.

Types of outcome measures

We assessed the following outcomes at 90 days after randomization (or at the end of scheduled follow‐up, if not provided at 90 days).

Primary outcomes

Death or dependence from any cause (measured on a standard rating scale, such as the modified Rankin Scale)

Secondary outcomes

All serious adverse events (if possible, with a separate analysis of arterial and venous thromboembolic events, including deep vein thrombosis symptomatic pulmonary embolism, arterial embolism, myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke, and disseminated intravascular coagulation)

Change in volume of ICH on follow‐up brain imaging

Death from any cause (categorised into early (e.g. less than seven days) and late (e.g. between seven days and the end of follow‐up) if possible)

Quality of life

Mood

Cognitive function

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We searched for trials in all languages, and arranged for the translation of relevant articles when necessary.

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Stroke Group Information Specialist searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched 27 November 2017), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 11) in the Cochrane Library (searched 27 November 2017; Appendix 1); MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 27 November 2017; Appendix 2); and Embase Ovid (1974 to 27 November 2017; Appendix 3).

One review author (ZL) also searched the following international registers of RCTs on 27 November 2017.

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov) using the search strategy in Appendix 4;

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; apps.who.int/trialsearch) using the search strategy in Appendix 5.

Searching other resources

In an effort to identify further published, ongoing, and unpublished RCTs, three authors (RA‐SS, NS, and ZL) scanned bibliographies of relevant articles.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors independently checked the titles and abstracts of studies identified by the search strategy for RCTs meeting the selection criteria for the first version of this review (You 2006). Two authors (ZL or RA‐SS) independently screened the results of the updated searches for potentially eligible studies for this updated review, and obtained the full published articles or trial registry entries for studies likely to be relevant RCTs. Two authors (NS and RA‐SS) independently read these potentially eligible RCTs in full, and confirmed their inclusion according to the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (NS and RA‐SS) used a standard data collection form to independently extract data on risk of bias, other RCT characteristics, participants, methods, interventions, outcomes, and results. If necessary, we sought additional data from the principal investigators of RCTs that met, or potentially met the inclusion criteria. We sought unpublished data that were not quantified in the original publications, or not presented as stratified by intracranial haemorrhage type, from the principal investigators and pharmaceutical companies. In the one study for which these data were not forthcoming, RA‐SS measured the numbers in the relevant groups in the stacked bar charts, using Adobe Acrobat Professional measuring tools on the PDF of the published study (Mayer 2008 (FAST)). In one phase II study, we could obtain only limited data from the Novo Nordisk website (F7ICH‐1602 2007).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (NS and RA‐SS) independently assessed included RCTs' risk of bias, according to the seven criteria of the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011). The same two authors discussed and agreed on the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome, using the GRADE approach (Higgins 2011).

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous data, and mean difference (MD), or standardized mean difference (SMD) for different measures of the same outcome, for continuous data.

Dealing with missing data

We sought missing data from studies' corresponding authors, and used all the data that were available to us.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We estimated inconsistency between RCTs using the I² statistic.

Assessment of reporting biases

We used funnel plots to assess publication bias where there were sufficient data.

Data synthesis

We used a random‐effects model (because we expected studies of different drugs and doses to estimate different, yet related, treatment effects) to calculate RRs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), with the inverse variance method.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We expected to find that the choice of intervention and comparator would be largely determined by the use and type of antithrombotic drug taken prior to a spontaneous acute ICH (e.g. fresh frozen plasma (FFP), or prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) for anticoagulant‐associated ICH, platelet transfusion for antiplatelet‐associated ICH). However, where interventions were used for ICH, whether it was associated with antithrombotic drug use or not (e.g. the clotting factor recombinant activated factor VII, antifibrinolytic drugs), and where ICH evacuation using craniotomy was performed, we stratified our analyses by pre‐ICH antithrombotic drug use and use of surgery.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Our searches identified 31 potentially eligible randomised controlled trials (RCT); see Figure 1 for the flowchart describing the searches done for this update. We excluded nine studies because: they never started (Ciccone 2007; NCT02429453), they did not report any of our primary or secondary outcomes (Meng 2003; Zhou 2005), they did not report data and outcomes in the intracerebral haemorrhage population (Kerebel 2013; Steiner 2016 (INCH)), they did not quantify outcomes (Madjdinasab 2008), the study was stopped due to poor enrolment but never reported results (NCT00222625), or the study did not relate to a haemostatic therapy (Li 2016). Ten RCTs were still in the process of recruitment (Liu 2017 (TRAIGE); Meretoja 2014 (STOP‐AUST); NCT00699621; NCT02777424; NCT02866838; NCT03044184; NOR‐ICH), follow‐up (Sprigg 2016 (TICH‐2)), or reporting (NCT00810888; NCT01359202) at the time of writing, and will be assessed for inclusion with the next update. This left 12 RCTs that we included in this review, all of which included acute intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) in adults aged 18 years or older (Arumugam 2015; Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH); Boulis 1999; F7ICH‐1602 2007; Imbert 2012 (PRE‐SICH); Li 2012; Mayer 2005a; Mayer 2005b; Mayer 2006; Mayer 2008 (FAST); Sprigg 2014 (TICH‐1); Zazulia 2001 (ATICH)).

1.

Study flow diagram

We included seven RCTs of blood clotting factors versus placebo or open control involving 1480 participants (F7ICH‐1602 2007; Imbert 2012 (PRE‐SICH); Li 2012; Mayer 2005a; Mayer 2005b; Mayer 2006; Mayer 2008 (FAST)), three RCTs of antifibrinolytic drugs versus placebo or open control involving 57 participants (Arumugam 2015; Sprigg 2014 (TICH‐1); Zazulia 2001 (ATICH)), one RCT of platelet transfusion versus open control involving 190 participants (Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH)), and one RCT of blood clotting factors versus fresh frozen plasma involving five participants (Boulis 1999).

Included studies

We included 12 RCTs. For details, please refer to the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Of the seven RCTs of blood clotting factors versus placebo or open control, six examined blood clotting factors in adults with acute spontaneous ICH (F7ICH‐1602 2007; Li 2012; Mayer 2005a; Mayer 2005b; Mayer 2006; Mayer 2008 (FAST)), and one in adults with acute spontaneous ICH undergoing craniotomy (Imbert 2012 (PRE‐SICH)). Five studies were funded and conducted by Novo Nordisk, and compared the use of various doses of intravenous recombinant activated clotting factor VII (rFVIIa; (973 participants)) against placebo (422 participants), started within four hours of ICH onset in adults (F7ICH‐1602 2007; Mayer 2005a; Mayer 2005b; Mayer 2006; Mayer 2008 (FAST)). Novo Nordisk supplied supplementary, unpublished data from three trials (Mayer 2005a; Mayer 2005b; Mayer 2006), but did not respond to several requests to provide further data from two trials (F7ICH‐1602 2007; Mayer 2008 (FAST)). The other study of intravenous rFVIIa was performed independently of Novo Nordisk, as a single centre, phase II study, in adults with acute spontaneous ICH within six hours of ICH onset (Li 2012). We had not pre‐specified the exclusion of RCTs of haemostatic therapies following surgical intervention, so we included Imbert 2012 (PRE‐SICH), which was a phase II study of intravenous rFVIIa in adults with acute spontaneous ICH undergoing craniotomy, administered immediately after the evacuation of the haematoma, within 24 hours of ICH onset.

Of the three RCTs of antifibrinolytic drugs versus placebo or open control, Zazulia 2001 (ATICH) was a phase II RCT of intravenous aminocaproic acid compared against supportive treatment alone, started within three hours of ICH onset in adults. Dr Allyson Zazulia provided unpublished data, because the trial was stopped after the enrolment of three participants because recruitment had been slow, and the investigators decided that the rationale for rFVIIa was better (Zazulia 2005). Sprigg 2014 (TICH‐1) was a phase II RCT of intravenous tranexamic acid compared against supportive treatment alone, started within 24 hours of ICH onset in adults. Arumugam 2015 was a phase II RCT of intravenous tranexamic acid compared against supportive treatment alone, started within eight hours of ICH onset in adults.

We found one RCT of platelet transfusion versus open control involving 190 participants (Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH)).

We found one RCT of blood clotting factors versus fresh frozen plasma involving five participants with acute spontaneous ICH associated with anticoagulant drug use (Boulis 1999).

Excluded studies

We excluded nine studies. For details, please refer to the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. We excluded two eligible RCTs because they presented aggregate data for adults with ICH as well as other types of intracranial haemorrhage, and the study authors could not provide data restricted to the ICH group alone by the time this review was submitted (Kerebel 2013; Steiner 2016 (INCH)). One abstract proposed a RCT of tranexamic acid for ICH, but the corresponding author confirmed that funding had not been obtained (Ciccone 2007). We found two studies of aprotinin, but it was unclear whether they included some participants in both studies, and the outcome measures used were unsuitable for meta‐analysis in this review (Meng 2003; Zhou 2005). NCT02429453 was a planned RCT of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) versus prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC), but was terminated before enrolment began. NCT00222625 was a study of coagulation factors, but it was "stopped due to slow recruitment" (Iorio 2012). Dr Iorio has not responded to requests for clarification about whether any data were collected. Madjdinasab 2008 was a study of coagulation factors, but no results were reported, and there was no response from the authors to requests for information for this review. Finally, Li 2016 was excluded as the intervention (TRABC) did not appear to be haemostatic, and had four Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) medicinals.

We identified 10 ongoing or recently completed but unreported RCTs. See 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' table for details. Two RCTs examined blood clotting factors versus placebo or open control (NCT00810888; NCT01359202), five examined antifibrinolytic drugs versus placebo or open control in acute spontaneous ICH (Liu 2017 (TRAIGE); Meretoja 2014 (STOP‐AUST); NCT03044184; NOR‐ICH; Sprigg 2016 (TICH‐2)); one RCT examined antifibrinolytic drugs versus placebo or open control in acute spontaneous ICH associated with anticoagulant drug use (NCT02866838); one RCT examined platelet transfusion versus open control (NCT00699621), and one RCT examined blood clotting factors versus fresh frozen plasma in acute spontaneous ICH associated with anticoagulant drug use (NCT02777424).

Risk of bias in included studies

Across all seven domains in the 12 included RCTs, we assessed that the risk of bias, according to the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool, and guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, was unclear in 37 (44%), high in 16 (19%), and low in 31 (37%; (Figure 2; Figure 3; Higgins 2011)). Only one RCT was at low risk of bias in all domains (Sprigg 2014 (TICH‐1)).

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias criteria for each included study

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias criteria presented as percentages across all included studies

Allocation

The risk of bias in random sequence generation was low in two RCTs, unclear in 10 RCTs, and high in none. The risk of bias in allocation concealment was low in two RCTs, unclear in nine RCTs, and high in one.

Only four RCTs clearly described the method of randomization (Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH); Mayer 2005b; Sprigg 2014 (TICH‐1); Zazulia 2001 (ATICH)), and one RCT simply mentioned 'block randomization according to site' (Mayer 2008 (FAST)).

Allocation was reported as being concealed in the papers for Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH) and Sprigg 2014 (TICH‐1), there was a risk of unblinding in one study (Mayer 2008 (FAST)), and the rest were unclear about allocation concealment.

It became apparent during questioning after the presentation of the Mayer 2008 (FAST) data at the European Stroke Conference in Glasgow, UK, in 2007 (Mayer 2007), that the imbalance in allocation between the three groups in this trial (there were approximately 30 more participants analysed in the 80 mcg/kg dose group than the other two groups) was due to the 80 mcg/kg dose of rFVIIa tending to be packed in the first of the three boxes of study drug for part of the trial (which might have unblinded investigators, in view of the preponderance of thromboembolic adverse events with the higher dose).

Blinding

Five of the 12 RCTs did not blind the intervention and comparator (Arumugam 2015; Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH); Boulis 1999; Imbert 2012 (PRE‐SICH); Zazulia 2001 (ATICH)), four did blind intervention and comparator, and the risk of bias was unclear in three RCTs. Whether participants and personnel were blinded to treatment allocation was only explicitly stated in Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH), but correspondence with the study authors verified that this was the case for Mayer 2006; Zazulia 2001 (ATICH), and Sprigg 2014 (TICH‐1). The risk of bias in the remaining RCTs was unclear in three RCTs, and high in five RCTs.

Risk of bias from blinding of outcome assessment was low in five RCTs, high in one RCT, and unknown in six RCTs. Assessment of radiological outcome was blinded to treatment allocation in nine included RCTs (Arumugam 2015; Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH); Imbert 2012 (PRE‐SICH); Mayer 2005a; Mayer 2005b; Mayer 2006; Mayer 2008 (FAST); Sprigg 2014 (TICH‐1); Zazulia 2001 (ATICH)), but information was not provided in others.

Incomplete outcome data

Overall, the risk of bias from incomplete outcome data was low in six RCTs, high in two RCTs, and unclear in the remaining four RCTs. Only Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH); Mayer 2008 (FAST), and Sprigg 2014 (TICH‐1) provided data about completeness of clinical follow‐up. In Arumugam 2015 and Li 2012, four participants had missing data. Boulis 1999 excluded eight participants after randomization. The last‐observation‐carried‐forward technique was used in Mayer 2005b and Mayer 2008 (FAST), which is likely to be unbiased only if the completeness of follow‐up was high.

Selective reporting

Bias from selective outcome reporting was low in eight RCTs, appeared to be low in two RCTs, and high in two other RCTs.

Other potential sources of bias

There were differences in baseline characteristics between treatment and control arms in the rFVIIa RCTs, especially in Mayer 2008 (FAST): 90‐day case fatality was worse in the placebo group in Mayer 2005b (29%) than in Mayer 2008 (FAST) (19%), which might be one explanation for the difference between the RCTs' findings. There was no visual evidence of funnel plot asymmetry in the largest group of RCTs, which compared blood clotting factors versus placebo or open control for death or dependency (Figure 4).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Blood clotting factors vs placebo or open control, outcome: 1.1 Death or dependence (mRS 4 to 6) at day 90

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Blood clotting factors versus placebo or open control.

| Blood clotting factors compared with placebo or open control for acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage | ||||

|

Patient or population: adults with acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage Settings: secondary care Intervention: recombinant activated factor VII Comparison: placebo or open control | ||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Death or dependence (mRS 4 to 6) at day 90 | RR 0.87 (0.70 to 1.07) | 1390 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate¹ | |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; mRS: modified Rankin Scale

¹We downgraded the quality of the evidence once because of imprecision.

Summary of findings 2. Antifibrinolytic drugs versus placebo.

| Antifibrinolytic drugs compared with placebo for acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage | ||||

|

Patient or population: adults with acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage Settings: secondary care Intervention: tranexamic acid Comparison: placebo | ||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Death or dependence (mRS 4 to 6) at day 90 | RR 1.25 (0.57 to 2.75) | 24 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate¹ | |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; mRS: modified Rankin Scale

¹We downgraded the quality of the evidence once because of imprecision.

Summary of findings 3. Platelet transfusion versus open control.

| Platelet transfusion compared with open control for acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage associated with antiplatelet drug use | ||||

|

Patient or population: adults with acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage associated with antiplatelet drug use Settings: secondary care Intervention: platelet transfusion Comparison: open control | ||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Death or dependence (mRS 4 to 6) at day 90 | RR 1.29 (1.04 to 1.61) | 190 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate¹ | |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; mRS: modified Rankin Scale

¹We downgraded the quality of the evidence once because of imprecision.

Summary of findings 4. Blood clotting factors versus fresh frozen plasma.

| Blood clotting factors compared with fresh frozen plasma for acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage associated with anticoagulant drug use | ||||

|

Patient or population: adults with acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage associated with anticoagulant drug use Settings: secondary care Intervention: fresh frozen plasma (intravenous), vitamin K (subcutaneous), and factor IX complex concentrate Comparison: fresh frozen plasma (intravenous) | ||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Death or dependence (mRS 4 to 6) at day 90 | No evidence | No evidence as mRS not measured | ||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

CI: confidence interval

We analysed data on intervention effects In 12 RCTs involving 1732 participants (1150 allocated to intervention and 582 allocated to control or active comparator), split by type of intervention as follows.

Blood clotting factors versus placebo or open control

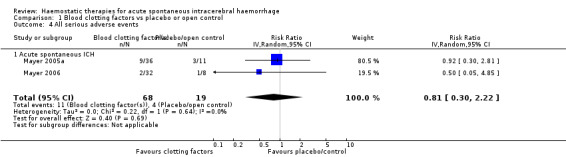

In RCTs of blood clotting factors (N = 1018) versus placebo or open control (N = 462) for acute spontaneous ICH with or without surgery, use of blood clotting factors led to non‐significant reductions in death or dependence (risk ratio (RR) 0.87, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.70 to 1.07; six trials, 1390 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1); in death (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.09; seven trials, 1480 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.3); in all serious adverse events (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.30 to 2.22; two trials, 87 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.4); and in ICH growth (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.48; three trials, 151 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.6). Blood clotting factors resulted in a non‐significant increase in all serious thromboembolic serious adverse events (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.91; five trials, 1398 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.5). In these analyses, the I² varied from 0% to 53%. We downgraded the quality of the evidence by one level because of concerns with design and risk of bias.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Blood clotting factors vs placebo or open control, Outcome 1 Death or dependence (mRS 4 to 6) at day 90.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Blood clotting factors vs placebo or open control, Outcome 3 Death by day 90.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Blood clotting factors vs placebo or open control, Outcome 4 All serious adverse events.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Blood clotting factors vs placebo or open control, Outcome 6 Intracerebral haemorrhage growth by 24 hours.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Blood clotting factors vs placebo or open control, Outcome 5 Thromboembolic serious adverse events.

Antifibrinolytic drugs versus placebo or open control

In RCTs of antifibrinolytic drugs (N = 33) versus placebo or open control (N = 24) for acute spontaneous ICH, use of antifibrinolytic drugs led to non‐significant increases in death or dependence (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.75; one trial, 24 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.1), in death (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.31 to 4.39; three trials, 57 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.2), in all serious adverse events (RR 1.50, 95% CI 0.39 to 5.83; one trial, 24 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.3), and in thromboembolic serious adverse events (RR 1.59, 95% CI 0.07 to 35.15; one trial, 24 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.4). Antifibrinolytic drugs led to a non‐significant reduction in ICH growth (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.05; three trials, 57 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.7). In these analyses, the I² was 0% to 1%. We downgraded the quality of the evidence to moderate because of imprecision.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytic drugs vs placebo or open control, Outcome 1 Death or dependence (mRS 4 to 6) at day 90.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytic drugs vs placebo or open control, Outcome 2 Death by day 90.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytic drugs vs placebo or open control, Outcome 3 All serious adverse events.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytic drugs vs placebo or open control, Outcome 4 Thromboembolic serious adverse events.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytic drugs vs placebo or open control, Outcome 7 Intracerebral haemorrhage growth by 24 hours.

Platelet transfusion versus open control

In one RCT of platelet transfusion (N = 97) versus open control (N = 93) for acute spontaneous ICH associated with antiplatelet drug use, platelet transfusion led to a significant increase in death or dependence (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.61; one trial, 190 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 3.1), and non‐significant increases in death (RR 1.42, 95% CI 0.88 to 2.28; one trial, 190 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 3.2), in all serious adverse events (RR 1.46, 95% CI 0.98 to 2.16; one trial, 190 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 3.3), in thromboembolic serious adverse events (RR 3.84, 95% CI 0.44 to 33.68; one trial, 190 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 3.4), and in ICH growth (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.56 to 2.20; one trial, 190 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 3.5). We downgraded the quality of the evidence by one level because of imprecision.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Platelet transfusion vs open control, Outcome 1 Death or dependence (mRS 4 to 6) at day 90.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Platelet transfusion vs open control, Outcome 2 Death by day 90.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Platelet transfusion vs open control, Outcome 3 All serious adverse events.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Platelet transfusion vs open control, Outcome 4 Thromboembolic serious adverse events.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Platelet transfusion vs open control, Outcome 5 Intracerebral haemorrhage growth by 24 hours.

Clotting factors versus fresh frozen plasma

No conclusions could be drawn from one small RCT of clotting factors (N = 2) versus fresh frozen plasma (N = 3) for acute spontaneous ICH associated with anticoagulant drug use, which did not report the primary outcome of this review.

Discussion

Summary of main results

There was moderate‐quality evidence, based on the findings of one RCT (190 participants), that platelet transfusion appeared hazardous in comparison to standard care for adults with antiplatelet‐associated intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH). Based on moderate‐quality evidence, we were unable to draw firm conclusions about the efficacy and safety of blood clotting factors versus placebo or open control for acute spontaneous ICH with or without surgery (seven trials, 1480 participants), or antifibrinolytic drugs versus placebo or open control for acute spontaneous ICH (three trials, 57 participants). The one very small trial (five participants) we found on clotting factors versus fresh frozen plasma for acute spontaneous ICH associated with anticoagulant drug use did not measure our primary outcome, and provided limited data on the secondary outcomes.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Alongside the 12 included RCTs, we were unable to include two eligible RCTs (N = 113) comparing clotting factors versus fresh frozen plasma for acute spontaneous ICH associated with anticoagulant drug use because data on participants with intracerebral haemorrhage could not be separated from participants with subdural intracranial haemorrhage (Kerebel 2013; Steiner 2016 (INCH)). This resulted in a shortage of data comparing clotting factors versus fresh frozen plasma for acute spontaneous ICH associated with anticoagulant drug use.

The results of 10 ongoing or recently completed unreported RCTs are awaiting completion and publication (Characteristics of ongoing studies). Two of these were recently completed RCTs (N = 142) investigating clotting factors in participants with radiological criteria associated with increased risk of haematoma expansion, so the RCTs in the review only include all patients with ICH and not the subgroup most at risk of ICH growth, i.e. those with the radiological 'spot sign' (tiny, enhancing foci within haematomas) (NCT00810888; NCT01359202).

There were few data available on antifibrinolytic drugs versus placebo after spontaneous acute ICH, but five ongoing RCTs (N > 2500) are investigating the antifibrinolytic drug tranexamic acid versus placebo in acute spontaneous ICH without anticoagulant use (Liu 2017 (TRAIGE); Meretoja 2014 (STOP‐AUST); NCT03044184; NOR‐ICH; Sprigg 2016 (TICH‐2)), and with anticoagulant drug use (NCT02866838). Publication of the largest RCT is expected in 2018 (Sprigg 2016 (TICH‐2)).

It was unclear whether recruitment was complete for one RCT of platelet transfusion (N = 100; NCT00699621). Further RCTs of platelet transfusion seem unlikely, so we await the publication of this RCT to see if the findings of Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH) are externally valid.

Quality of the evidence

We included 12 RCTs with 1732 participants (1150 allocated to intervention, 582 allocated to control or active comparator). One double‐blind RCT (Sprigg 2014 (TICH‐1)), and one open RCT (Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH)), were at low risk of bias, but the risk of bias of most other RCTs was moderate to high (Figure 2; Figure 3). The RCT finding harm from platelet transfusion has not been replicated in another RCT (Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH)).

The largest quantity of data was from RCTs of recombinant activated clotting factor VII (rFVIIa), which were at moderate risk of bias, and their results were moderately inconsistent, showing non‐significant benefits of rFVIIa. These findings have not changed practice (Hemphill 2015 (AHA ICH); RCP 2016; Steiner 2014 (ESO ICH)), and have led to explorations of the use of rFVIIa in ICH sub‐groups in as‐yet‐unpublished RCTs (NCT00810888; NCT01359202).

We rated the overall quality of all of the available evidence as moderate for three comparisons on the grounds of imprecision (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 2.1; Analysis 3.1), and poor for one comparison on the grounds of imprecision and limitations in study design (Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Blood clotting factors vs fresh frozen plasma, Outcome 1 Death by day 90.

Potential biases in the review process

We followed a dual review process: two authors (NS and RA‐SS) independently extracted data that reduced identification bias and improved risk of bias assessment in comparison to the previous update of this review.

We were unable to include data from two eligible studies that separately showed benefits of clotting factors versus FFP on intermediate outcomes (speed of international normalised ratio (INR) reduction) after intracranial haemorrhage as data were not available for the ICH population; we hope to include these RCTs in the next update of this review to also examine the effect of clotting factors versus FFP on clinical outcomes (Steiner 2016 (INCH); Kerebel 2013).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This review was completed after the most recent updates of the European and North American ICH guidelines (Hemphill 2015 (AHA ICH); Steiner 2014 (ESO ICH)). These guidelines predated the results of Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH), and simply found that "the usefulness of platelet transfusions in ICH patients with a history of antiplatelet use is uncertain". Guidance on platelet transfusion has changed to reflect the results of Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH), where platelet transfusion was associated with a worse outcome, hence platelet transfusion is not recommended (Dastur 2017). Consistent with our findings, guidelines have not recommended the use of clotting factors, such as rFVIIa for acute spontaneous ICH not associated with anticoagulant use (Hemphill 2015 (AHA ICH); RCP 2016; Steiner 2014 (ESO ICH)). The AHA and ESO guidelines preceded the publication of Steiner 2016 (INCH), but the national stroke guidelines in the UK recommend using prothrombin complex concentrate for anticoagulant‐associated ICH, reflecting the findings of Steiner 2016 (INCH) on the intermediate outcome of speed of INR reduction (RCP 2016).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Platelet transfusion appears hazardous in comparison to standard care for adults with antiplatelet‐associated ICH (this is based on the findings of one trial). We are unable to draw firm conclusions about the efficacy and safety of blood clotting factors for acute spontaneous ICH (with or without surgery), antifibrinolytic drugs for acute spontaneous ICH, clotting factors or fresh frozen plasma for acute spontaneous ICH associated with anticoagulant drug use.

Implications for research.

Although rFVIIa does not appear beneficial on the basis of existing evidence, RCTs of its use in specific subgroups have been undertaken and their results are awaited (NCT00810888; NCT01359202). Clotting factors appear superior to fresh frozen plasma for normalising coagulation in the RCTs that we could not include because they were not restricted to ICH (Kerebel 2013; Steiner 2016 (INCH)), but their superiority for improving clinical outcome needs to be established. The effect of antifibrinolytic drugs for acute ICH is uncertain, but in view of their effects in other conditions (Ker 2015), the results of several ongoing RCTs are keenly awaited (Liu 2017 (TRAIGE); Meretoja 2014 (STOP‐AUST); NCT02866838; NCT03044184; Sprigg 2016 (TICH‐2)).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 December 2017 | New search has been performed |

|

| 10 December 2017 | New citation required and conclusions have changed |

|

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2006 Review first published: Issue 3, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 June 2013 | Amended | Co‐authors added |

| 29 June 2009 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | In comparison to the previous version of this review, haemostatic drugs no longer significantly reduced death or dependence after acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. |

| 29 June 2009 | New search has been performed | Updated with the addition of 841 people randomised in the FAST trial. |

| 8 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to You Hong who was a co‐author for the first published version of this review (You 2006). We are also grateful to Huey‐Juan Lin, Mei‐Chiun Tseng, and Michael Poon for their help with translation and data extraction. We thank the staff at the Cochrane Stroke Group editorial office for their assistance.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 11) in the Cochrane Library (searched 27 November 2017)

#1 [mh hemostatics]

#2 [mh "Blood Coagulation Factors"]

#3 [mh ^hemostasis/DE] or [mh ^"blood coagulation"/DE] or [mh ^fibrinolysis/DE] or [mh "platelet activation"/DE] or [mh antithrombins] or [mh ^thrombin/AI]

#4 ((haemosta* or hemosta* or antihaemorrhag* or antihemorrhag*) near/5 (drug* or agent* or treat* or therap*)):ti,ab

#5 (antifibrinolytic* or coagulat* next factor* or clotting next factor* or aminocaproic next acid or 6‐aminocaproic next acid or "tranexamic acid" or aprotinin or factor next VII* or "factor 7" or "factor 7a" or NovoSeven or thrombin next inhib* or argatroban):ti,ab

#6 [mh ^"platelet transfusion"] or [mh ^"blood component transfusion"]

#7 [mh ^"blood platelets"]

#8 (infus* or transfus*):ti,ab

#9 #7 and #8

#10 ((platelet* or thrombocyte* or blood component*) near/5 (transfus* or infus*)):ti,ab

#11 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #9 or #10

#12 [mh "basal ganglia haemorrhage"] or [mh ^"intracranial hemorrhages"] or [mh ^"cerebral haemorrhage"] or [mh ^"intracranial hemorrhage, hypertensive"]

#13 ((brain* or cerebr* or cerebell* or intracerebral or intracran* or parenchymal or intraparenchymal or intraventricular or infratentorial or supratentorial or basal next gangli* or putaminal or putamen or posterior next fossa or hemispher* or stroke or apoplex*) near/5 (haemorrhage* or hemorrhage* or haematoma* or hematoma* or bleed*)):ti,ab

#14 (ICH or ICHs):ti,ab

#15 #12 or #13 or #14

#16 #11 and #15

Appendix 2. MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 27 November 2017)

1. exp hemostatics/

2. exp Blood Coagulation Factors/

3. hemostasis/de or blood coagulation/de or fibrinolysis/de or exp platelet activation/de or exp antithrombins/ or thrombin/ai

4. ((haemosta$ or hemosta$ or antihaemorrhag$ or antihemorrhag$) adj5 (drug$ or agent$ or treat$ or therap$)).tw.

5. (antifibrinolytic$ or coagulat$ factor$ or clotting factor$ or aminocaproic acid or 6‐ aminocaproic acid or tranexamic acid or aprotinin or factor VII$ or factor 7 or factor 7a or NovoSeven or thrombin inhib$ or argatroban).tw,nm.

6. platelet transfusion/

7. blood component transfusion/

8. blood platelets/ and (infus$ or transfus$).tw.

9. ((platelet$ or thrombocyte$ or blood component$) adj5 (transfus$ or infus$)).tw.

10. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9

11. exp basal ganglia hemorrhage/ or intracranial hemorrhages/ or cerebral hemorrhage/ or intracranial hemorrhage, hypertensive/

12. ((brain$ or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or intracerebral or intracran$ or parenchymal or intraparenchymal or intraventricular or infratentorial or supratentorial or basal gangli$ or putaminal or putamen or posterior fossa or hemispher$ or stroke or apoplex$) adj5 (h?emorrhag$ or h?ematoma$ or bleed$)).tw.

13. 11 or 12 or (ICH or ICHs).tw.

14. 10 and 13

15. Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic/

16. random allocation/

17. Controlled Clinical Trials as Topic/

18. control groups/

19. clinical trials as topic/ or clinical trials, phase i as topic/ or clinical trials, phase ii as topic/ or clinical trials, phase iii as topic/ or clinical trials, phase iv as topic/

20. double‐blind method/

21. single‐blind method/

22. Placebos/

23. placebo effect/

24. Drug Evaluation/

25. Research Design/

26. randomized controlled trial.pt.

27. controlled clinical trial.pt.

28. clinical trial.pt.

29. random$.tw.

30. (controlled adj5 (trial$ or stud$)).tw.

31. (clinical$ adj5 trial$).tw.

32. ((control or treatment or experiment$ or intervention) adj5 (group$ or subject$ or patient$)).tw.

33. (quasi‐random$ or quasi random$ or pseudo‐random$ or pseudo random$).tw.

34. ((singl$ or doubl$ or tripl$ or trebl$) adj5 (blind$ or mask$)).tw.

35. placebo$.tw.

36. controls.tw.

37. or/15‐36

38. 14 and 37

39. exp animals/ not humans.sh.

40. 38 not 39

Appendix 3. Embase Ovid (1974 to 27 November 2017)

1. exp hemostatic agent/ or exp antifibrinolytic agent/ or exp blood clotting factor/ or exp thrombin inhibitor/

2. hemostasis/

3. exp blood clotting/

4. thrombocyte activation/

5. 2 or 3 or 4

6. drug effect/ or dt.fs.

7. 5 and 6

8. ((haemosta$ or hemosta$ or antihaemorrhag$ or antihemorrhag$) adj5 (drug$ or agent$ or treat$ or therap$)).tw.

9. (antifibrinolytic$ or coagulat$ factor$ or clotting factor$ or aminocaproic acid or 6‐ aminocaproic acid or tranexamic acid or aprotinin or factor VII$ or factor 7 or factor 7a or NovoSeven or thrombin inhib$ or argatroban).tw.

10. thrombocyte transfusion/

11. blood component therapy/

12. exp thrombocyte/ and (infus$ or transfus$).tw.

13. ((platelet$ or thrombocyte$ or blood component$) adj5 (transfus$ or infus$)).tw.

14. 1 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13

15. basal ganglion hemorrhage/ or brain hemorrhage/ or brain ventricle hemorrhage/ or cerebellum hemorrhage/

16. ((brain$ or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or intracerebral or intracran$ or parenchymal or intraparenchymal or intraventricular or infratentorial or supratentorial or basal gangli$ or putaminal or putamen or posterior fossa or hemispher$ or stroke or apoplex$) adj5 (h?emorrhag$ or h?ematoma$ or bleed$)).tw.

17. 15 or 16 or (ICH or ICHs).tw.

18. 14 and 17

19. randomized controlled trial/

20. "randomized controlled trial (topic)"/

21. Randomization/

22. Controlled Study/

23. control group/

24. exp clinical trial/

25. Double Blind Procedure/

26. Single Blind Procedure/ or triple blind procedure/

27. placebo/

28. drug dose comparison/

29. drug comparison/

30. "types of study"/

31. random$.tw.

32. (controlled adj5 (trial$ or stud$)).tw.

33. (clinical$ adj5 trial$).tw.

34. ((control or treatment or experiment$ or interventionl) adj5 (group$ or subject$ or patient$)).tw.

35. (quasi‐random$ or quasi random$ or pseudo‐random$ or pseudo random$).tw.

36. ((singl$ or doubl$ or tripl$ or trebl$) adj5 (blind$ or mask$)).tw.

37. placebo$.tw.

38. controls.tw.

39. or/19‐38

40. 18 and 39

41. (exp animals/ or exp invertebrate/ or animal experiment/ or animal model/ or animal tissue/ or animal cell/ or nonhuman/) not (human/ or normal human/ or human cell/)

42. 40 not 41

Appendix 4. US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov

Study Type: Intervention

Study results: All studies

Recruitment: All studies

Age group: Adults & seniors

Condition: (cerebral haemorrhage OR intracerebral haemorrhage OR intracranial haemorrhage OR intraparenchymal haemorrhage OR parenchymal haemorrhage OR intraventricular haemorrhage OR haemorrhagic stroke OR ICH OR intracerebral bleed)

Intervention (performed as four separate searches, and then de‐duplicated, due to the word limit for search criteria): haemostatics OR haemostasis OR haemostatic agents OR haemostatic therapy OR haemostatic treatment OR antihaemorrhagic agent OR antihaemorrhagic therapy OR antihaemorrhagic treatment OR antihaemorrhage agent OR antihaemorrhage therapy OR blood clotting OR blood coagulation factors OR blood coagulation OR coagulation factors OR thrombin OR platelet activation OR thrombocyte activation OR platelet transfusion OR blood component transfusion OR thrombocyte transfusion OR antifibrinolytic agents OR antifibrinolysis OR tranexamic acid OR aminocaproic acid OR 6‐aminocaproic acid OR aprotinin OR factor VIIa OR factor VII OR Factor 7a OR factor 7 or NovoSeven Or argatroban OR thrombin inhibitor OR desmopressin OR fresh frozen plasma OR FFP OR prothrombin complex concentrates OR PCC

Appendix 5. World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)

Condition: brain haemorrhage OR cerebral haemorrhage OR intracerebral haemorrhage OR intracranial haemorrhage OR intraparenchymal haemorrhage OR intraventricular haemorrhage OR cerebellar haemorrhage OR parenchymal haemorrhage OR infratentorial haemorrhage OR supratentorial haemorrhage OR basal ganglia haemorrhage OR basal ganglion haemorrhage OR thalamic haemorrhage OR putaminal haemorrhage OR posterior fossa haemorrhage OR hemispheric haemorrhage OR haemorrhagic stroke OR haemorrhagic apoplexy brain haematoma OR cerebral haematoma OR intracerebral haematoma OR intracranial haematoma OR intraparenchymal haematoma OR intraventricular haematoma OR cerebellar haematoma OR parenchymal haematoma OR infratentorial haematoma OR supratentorial haematoma OR basal ganglia haematoma OR basal ganglion haematoma OR thalamic haematoma OR putaminal haematoma OR posterior fossa haematoma OR hemispheric haematoma OR brain bleed OR cerebral bleed OR intracerebral bleed OR intracranial bleed OR intraparenchymal bleed OR parenchymal bleed OR intraventricular bleed OR cerebellar bleed OR infratentorial bleed OR supratentorial bleed OR basal ganglia bleed OR putaminal bleed OR posterior fossa bleed OR hemispheric bleed OR ICH OR ICHs

Intervention: haemostatics OR haemostasis OR haemostatic agents OR haemostatic therapy OR haemostatic treatment OR antihaemorrhagic agent OR antihaemorrhagic therapy OR antihaemorrhagic treatment OR antihaemorrhage agent OR antihaemorrhage therapy OR antihaemorrhage treatment OR blood clotting OR blood coagulation factors OR blood coagulation OR coagulation factors OR thrombin OR platelet activation OR thrombocyte activation OR platelet transfusion OR blood component transfusion OR thrombocyte transfusion OR antifibrinolytic agents OR antifibrinolysis OR tranexamic acid OR aminocaproic acid OR 6‐aminocaproic acid OR aprotinin OR factor VIIa OR factor VII OR Factor 7a OR factor 7 or NovoSeven Or argatroban OR thrombin inhibitor OR desmopressin OR fresh frozen plasma OR FFP OR prothrombin complex concentrates OR PCC

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Blood clotting factors vs placebo or open control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death or dependence (mRS 4 to 6) at day 90 | 6 | 1390 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.70, 1.07] |

| 1.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 5 | 1369 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.66, 1.11] |

| 1.2 Acute spontaneous ICH undergoing craniotomy | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.59, 1.31] |

| 2 Death or dependence (GOS‐E 1 to 4) at day 90 | 3 | 486 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.81, 1.01] |

| 2.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 3 | 486 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.81, 1.01] |

| 3 Death by day 90 | 7 | 1480 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.51, 1.09] |

| 3.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 6 | 1459 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.44, 1.14] |

| 3.2 Acute spontaneous ICH undergoing craniotomy | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.41, 1.80] |

| 4 All serious adverse events | 2 | 87 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.30, 2.22] |

| 4.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 2 | 87 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.30, 2.22] |

| 5 Thromboembolic serious adverse events | 5 | 1398 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.80, 1.91] |

| 5.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 5 | 1398 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.80, 1.91] |

| 6 Intracerebral haemorrhage growth by 24 hours | 3 | 151 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.36, 1.48] |

| 6.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 3 | 151 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.36, 1.48] |

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Blood clotting factors vs placebo or open control, Outcome 2 Death or dependence (GOS‐E 1 to 4) at day 90.

Comparison 2. Antifibrinolytic drugs vs placebo or open control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death or dependence (mRS 4 to 6) at day 90 | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.57, 2.75] |

| 1.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.57, 2.75] |

| 2 Death by day 90 | 3 | 57 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.31, 4.39] |

| 2.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 3 | 57 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.31, 4.39] |

| 3 All serious adverse events | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.5 [0.39, 5.83] |

| 3.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.5 [0.39, 5.83] |

| 4 Thromboembolic serious adverse events | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.59 [0.07, 35.15] |

| 4.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.59 [0.07, 35.15] |

| 5 Barthel Index | 1 | 24 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐22.50 [‐45.65, 0.65] |

| 5.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 1 | 24 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐22.50 [‐45.65, 0.65] |

| 6 EuroQoL health utility score | 1 | 24 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.35, 0.27] |

| 6.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 1 | 24 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.35, 0.27] |

| 7 Intracerebral haemorrhage growth by 24 hours | 3 | 57 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.56, 1.05] |

| 7.1 Acute spontaneous ICH | 3 | 57 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.56, 1.05] |

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytic drugs vs placebo or open control, Outcome 5 Barthel Index.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytic drugs vs placebo or open control, Outcome 6 EuroQoL health utility score.

Comparison 3. Platelet transfusion vs open control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death or dependence (mRS 4 to 6) at day 90 | 1 | 190 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.29 [1.04, 1.61] |

| 1.1 Acute antiplatelet‐associated ICH | 1 | 190 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.29 [1.04, 1.61] |

| 2 Death by day 90 | 1 | 190 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.88, 2.28] |

| 2.1 Acute antiplatelet‐associated ICH | 1 | 190 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.88, 2.28] |

| 3 All serious adverse events | 1 | 190 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.46 [0.98, 2.16] |

| 3.1 Acute antiplatelet‐associated ICH | 1 | 190 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.46 [0.98, 2.16] |

| 4 Thromboembolic serious adverse events | 1 | 190 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.84 [0.44, 33.68] |

| 4.1 Acute antiplatelet‐associated ICH | 1 | 190 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.84 [0.44, 33.68] |

| 5 Intracerebral haemorrhage growth by 24 hours | 1 | 190 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.56, 2.20] |

| 5.1 Acute antiplatelet‐associated ICH | 1 | 190 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.56, 2.20] |

Comparison 4. Blood clotting factors vs fresh frozen plasma.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death by day 90 | 1 | 5 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.27 [0.02, 3.74] |

| 1.1 Acute anticoagulant‐associated ICH | 1 | 5 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.27 [0.02, 3.74] |

| 2 All serious adverse events | 1 | 5 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.27 [0.02, 3.74] |

| 2.1 Acute anticoagulant‐associated ICH | 1 | 5 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.27 [0.02, 3.74] |

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Blood clotting factors vs fresh frozen plasma, Outcome 2 All serious adverse events.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Arumugam 2015.

| Methods | Single‐blinded, randomised placebo‐controlled trial of tranexamic acid (intravenous 1 g bolus, followed by infusion 1 g/h for 8 h) in acute (< 8 h) primary ICH. Strict blood pressure control (target SBP 140 mmHg to 160 mmHg). A repeat brain CT was done after 24 h to reassess haematoma growth. The primary objective was to test the effect of tranexamic acid on haematoma growth. Other objectives were to test the feasibility, tolerability, and adverse events of tranexamic acid in primary ICH. |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions | Intervention: tranexamic acid (1 g diluted in 100 mL of 0.9% saline) over a period of 10 minutes. The initial dose was followed by a maintenance dose of 1 g/h for 8 h. Labetalol infusion 2 mg/min to achieve SBP 140 mmHg to 160 mmHg Comparator: placebo mentioned, but not described. Labetalol infusion 2 mg/min to achieve SBP 140 mmHg to 160 mmHg |

|

| Outcomes | Repeat CT brain scan was performed after 24 h, and a blinded radiologist evaluated the size and volume of the haematoma. Adverse events due to tranexamic acid that occurred within 24 h of the treatment were documented by the investigator or pharmacist. | |

| Notes | _ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Each envelope represented either the drug or control group, which was assigned using a random sequence programmer." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Patients or their family members randomly chose one envelope from a box containing 30 closed envelopes." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Single blind |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded radiologist for primary outcome. High risk for other outcomes (not stated as blinded) |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 4 participants had missing data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes in the paper were reported. No protocol |

Baharoglu 2016 (PATCH).

| Methods | Multicentre, open‐label, masked‐endpoint, randomized trial, using a secure web‐based system that concealed allocation and used biased coin randomization (1:1 stratified by hospital and type of antiplatelet therapy) | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions | Intervention: standard care with platelet transfusion within 90 minutes of diagnostic brain imaging Comparator: standard care |

|

| Outcomes | The primary outcome was shift towards death or dependence rated on the mRS at 3 months, and analysed by ordinal logistic regression, adjusted for stratification. Variables and the Intracerebral Haemorrhage Score Secondary clinical outcomes at 3 months were: survival (mRS score of 1 to 5), poor outcome defined as an mRS score of 4 to 6, and poor outcome defined as an mRS score of 3 to 6. The secondary explanatory outcome was median absolute intracerebral haemorrhage growth in mL after 24 h on brain imaging. Safety outcomes were defined as complications of platelet transfusion (transfusion reactions, thrombotic complications). |

|

| Notes | NTR1303 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomisation was done by investigators via a secure, web‐based, computerised randomization system (TENALEA, Clinical Trial Data Management system; NKIAVL, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) that stratified assignment by study hospital and type of pre‐intracerebral haemorrhage antiplatelet therapy (COX inhibitor alone, ADP receptor inhibitor alone, COX inhibitor with an adenosine‐reuptake inhibitor, or COX inhibitor with an ADP receptor inhibitor). A biased coin randomization was used, with coin bias factor of 3 and coin bias threshold of 2" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation was concealed from investigators by the web‐based randomization system |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Participants and local investigators giving interventions were not masked to treatment allocation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Treatment allocation was concealed to outcome assessors and investigators analysing data |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Follow‐up for the primary outcome was complete |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes were reported |

Boulis 1999.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions | Intervention: fresh frozen plasma Comparator: fresh frozen plasma (intravenous), vitamin K (subcutaneous) and factor IX complex concentrate (Konyne; Bayer, Elkhart, IN: containing high concentrations of activated vitamin K‐dependent clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X; dosage according to body weight; intravenous infusion at 100 IU/min) |

|

| Outcomes | Time to INR correction, rate of INR correction, change in GCS | |

| Notes | _ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding was not described |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding was not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Post‐randomisation exclusion of 8 participants |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Outcomes not pre‐specified |

F7ICH‐1602 2007.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, Japanese multicentre, placebo‐controlled, phase II dose‐escalation trial with 3 dose tiers | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions | Intervention: recombinant activated factor VII (NovoSeven) at doses of 40 mcg/kg (N = 15), 80 mcg/kg (N = 15), or 120 mcg/kg (N = 15), within 1 h of baseline CT Comparator: placebo (N = 45), within 1 h of baseline CT |

|

| Outcomes | Preliminary efficacy evaluations were performed as follows

Criteria for evaluation: safety

|

|

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00266006. This unpublished trial was funded by Novo Nordisk, which did not respond to requests to provide data beyond what was on their website. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Participants and personnel said to be blinded to treatment allocation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | The assessment of outcomes was not explicitly stated to be blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Data not provided for most major outcomes |

Imbert 2012 (PRE‐SICH).

| Methods | Randomised (2:1), open‐label, single‐blinded parallel group phase 2 pilot trial involving 21 participants with spontaneous supratentorial ICH diagnosed by CT | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions | All participants were intubated, ventilated, and underwent craniotomy with the intention of complete haematoma removal. The haematoma cavity was lined with Surgicel (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA). Blood pressure was measured continuously, and data were collected every 1 to 2 h. Efforts were made to maintain the mean arterial blood pressure between 90 mmHg and 130 mmHg, PaCO₂ within the range of 35 mmHg to 40 mmHg, natraemia between 137 and 147 mmol/L and to obtain normoglycaemia (80 mg/dL to 110 mg/dL) Intervention: 100 mcg/kg of rFVIIa (NovoSeven, Novo Nordisk, Denmark) by intravenous infusion in 5 to 10 minutes immediately after evacuation of the haematoma, at the beginning of the closure of the dura Comparator: saline solution by intravenous infusion in 5 to 10 minutes immediately after evacuation of the haematoma, at the beginning of the closure of the dura |

|

| Outcomes | Haematoma volume was assessed by CT scan immediately, 18 h to 30 h, and 5 days to 7 days after evacuation of the haematoma. The primary endpoint was haematoma volume at 18 h to 30 h after surgery. Outcome was evaluated at 6 months using the mRS; poor outcome was defined as death or an mRS score of 4 to 5, and good outcome was defined as an mRS score of 0 to 3 | |

| Notes | NCT00128050 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | They stated the trial was both open label and placebo controlled in the methods, but that 'saline' was the comparator. This seemed like an open trial |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Haematoma volume assessment blinded, but unsure about clinical outcomes |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Seemed complete for all outcomes. Unable to extract data on haematoma growth, all SAEs, and all thromboembolic adverse events (although they were reported separately) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes specified in the methods appeared to have been reported |

Li 2012.

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions | Intervention: intravenous rFVIIa (NovoSeven) 40 μg/kg, concentration at 0.6 g/L, within 6 h of ICH onset, injected over 2 to 5 minutes Comparator: routine or best medical treatment All participants received Piracetam 8 g iv 4 times/day |

|

| Outcomes | ICH growth, GCS at 24 h, NIHSS at 24 h, mRS at 90 days, adverse events | |

| Notes | Data extracted by Dr Michael Poon (www.researchgate.net/profile/Michael_Poon3) from full text record available from en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal‐ZXYZ201202009.htm | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not mentioned |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not mentioned |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not mentioned |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes appeared to be reported |

Mayer 2005a.

| Methods | Parallel group, randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase II: a dose‐escalation safety and efficacy study | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Intervention: recombinant activated factor VII (NovoSeven) at doses of 10 mcg/kg, 20 mcg/kg, 40 mcg/kg, 80 mcg/kg, 120 mcg/kg, or 160 mcg/kg, within 1 h of baseline CT Comparator: placebo, within 1 h of baseline CT |

|

| Outcomes | Adverse events at days 1 to 5, 15 (or hospital discharge), and 90; change in ICH ± IVH volume on CT between baseline and 24 h; ICH growth (> 33% or 12.5 mL); drop of > 1 GCS point or increase of > 3 NIHSS points on days 0 to 5; dead versus alive with little disability (BI 95 to 100, GOS‐E 8, mRS 0 to 2), versus alive and functionally independent (BI 60 to 100, GOS‐E 5 to 8, mRS 0 to 3) at day 90 | |

| Notes | There was imbalance in the baseline ICH volumes between placebo and treatment groups (increasing with higher recombinant factor VIIa doses), although the authors stated that this was not statistically significant. The trial drug was given to 2 of 47 participants more than 4 h after ICH onset. This trial was funded by Novo Nordisk. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The method of randomization was not specified |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. Quote: "A randomization schedule was generated." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Providers were said to be blinded to treatment allocation (but treatment dose escalation may have been apparent) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | The assessment of outcomes was not explicitly stated to be blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Mayer 2005b.

| Methods | Parallel group, randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase IIB, dose‐ranging, proof‐of‐concept study | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Intervention: recombinant activated factor VII (NovoSeven) at doses of 40 mcg/kg, 80 mcg/kg, or 160 mcg/kg, within 1 h of baseline CT and no later than 4 h after ICH onset Comparator: placebo, within 1 h of baseline CT and no later than 4 h after ICH onset |

|

| Outcomes | Percentage change in ICH volume on CT from baseline to 24 h; mRS 4 to 6, or GOS‐E 1 to 4 at 90 days; adverse events in hospital, and serious adverse events until day 90 | |

| Notes | One important exclusion criterion was changed mid‐way through the RCT. This trial was funded by Novo Nordisk, which did not respond to repeated requests to provide further data from this trial. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |