Abstract

Background

Postoperative ileus is a major complication for persons undergoing abdominal surgery. Daikenchuto, a Japanese traditional medicine (Kampo), is a drug that may reduce postoperative ileus.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of Daikenchuto for reducing prolonged postoperative ileus in persons undergoing elective abdominal surgery.

Search methods

We searched the following databases on 3 July 2017: CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, ICHUSHI, WHO (World Health Organization) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), EU Crinical Trials registry (EU‐CTR), UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN‐CTR), ClinicalTrials.gov, The Japan Society for Oriental Medicine (JSOM), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endscopic Surgeons (SAGES). We set no limitations on language or date of publication.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing Daikenchuto with any control condition in adults, 18 years of age or older, undergoing elective abdominal surgery.

Data collection and analysis

We applied standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. Two review authors independently reviewed the articles identified by literature searches, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias of the included studies using the Cochrane software Review Manager 5.

Main results

We included seven RCTs with a total of 1202 participants. Overall, we judged the risk of bias as low in four studies and high in three studies. We are uncertain whether Daikenchuto reduced time to first flatus (mean difference (MD) ‐11.32 hours, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐17.45 to ‐5.19; two RCTs, 83 participants; very low‐quality evidence), or time to first bowel movement (MD ‐9.44 hours, 95% CI ‐22.22 to 3.35; four RCTs, 500 participants; very low‐quality evidence) following surgery. There was little or no difference in time to resumption of regular solid food following surgery (MD 3.64 hours, 95% CI ‐24.45 to 31.74; two RCTs, 258 participants; low‐quality evidence). There were no adverse events in either arm of the five RCTs that reported on drug‐related adverse events (risk difference (RD) 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.02, 568 participants, low‐quality evidence). We are uncertain of the effect of Daikenchuto on patient satisfaction (MD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.37; one RCT, 81 participants; very low‐quality of evidence). There was little or no difference in the incidence of any re‐interventions for postoperative ileus before leaving hospital (risk ratio (RR) 0.99, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.62; one RCT, 207 participants; moderate‐quality evidence), or length of hospital stay (MD ‐0.49 days, 95% CI ‐1.21 to 0.22; three RCTs, 292 participants; low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Evidence from current literature was unclear whether Daikenchuto reduced postoperative ileus in patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery, due to the small number of participants in the meta‐analyses. Very low‐quality evidence means we are uncertain whether Daikenchuto improved postoperative flatus or bowel movement. Further well‐designed and adequately powered studies are needed to assess the efficacy of Daikenchuto.

Keywords: Humans, Abdomen, Abdomen/surgery, Defecation, Elective Surgical Procedures, Elective Surgical Procedures/adverse effects, Flatulence, Flatulence/etiology, Ileus, Ileus/prevention & control, Patient Satisfaction, Plant Extracts, Plant Extracts/therapeutic use, Postoperative Complications, Postoperative Complications/prevention & control, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Time Factors

Does Daikenchuto reduce postoperative ileus in persons undergoing elective abdominal surgery?

Background

Postoperative ileus is the medical term for a functional obstruction of the bowel, and a common complication in persons who undergo abdominal surgery. It is characterized by lack of bowel movements, causing an accumulation of bowel contents, and delayed flatus (passing gas). Persons with persistent postoperative ileus are immobilized, have discomfort and pain, and are at increased risk for other complications. This results in prolonged hospitalisation and increased medical costs. Daikenchuto is a Japanese traditional medicine (also known as Kampo) that may reduce postoperative ileus.

Review question

This review investigated whether Daikenchuto reduced postoperative ileus in persons undergoing abdominal surgery.

Study characteristics

We included seven studies (1202 participants), in which the participants were allocated at random (by chance alone) to receive one of several clinical interventions, where Daikenchuto was compared with any other medicine, placebo, or no treatment. The searches were performed 3 July 2017. We evaluated: time from completion of abdominal surgery to first flatus, time to first bowel movement, time to resumption of regular solid food intake, adverse events related to Daikenchuto, patient satisfaction, re‐interventions for postoperative ileus before leaving hospital, and length of hospital stay.

Key results and quality of evidence

Overall, there were a small number of participants included in each analysis. We could not fully investigate time from surgery to first flatus, to first bowel movement, or to resumption of regular solid food intake, any medicine‐related adverse events, patient satisfaction, any re‐interventions for postoperative ileus before leaving hospital, or length of hospital stay. We considered the quality of evidence for all presented outcomes as moderate to very low.

Authors' conclusion

Based upon our findings, it was uncertain whether Daikenchuto accelerated post‐surgical bowel motility in persons undergoing abdominal surgery, and thus, unclear whether Daikenchuto reduced postoperative ileus.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Daikenchuto compared to control for reducing postoperative ileus

| Daikenchuto compared to control for reducing postoperative ileus | ||||||

|

Participants: patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery, either open or laparoscopic Setting: hospital Intervention: all doses of Daikenchuto, administered orally and regularly in the preoperative or postoperative periods, or both Comparison: placebo, any intestinal stimulant, or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with Daikenchuto | |||||

| Time from completion of operation to first flatus (hours) | The mean time from completion of operation to first flatus in the control groups was 75.50 hours | The mean time from completion of operation to first flatus in the Daikenchuto groups was 11.32 hours less (17.45 hours less to 5.19 hours less) | ‐ | 83 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | |

| Time from completion of operation to first bowel movement (hours) | The mean time from completion of operation to first bowel movement in the control groups was 105.15 hours | The mean time from completion of operation to first bowel movement in the Daikenchuto groups was 9.44 hours less (22.22 hours less to 3.35 hours more) | ‐ | 500 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 4 | |

| Time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food intake (hours) | The mean time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food intake in the control groups was 101.50 hours | The mean time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food intake in the Daikenchuto groups was 3.64 hours more (24.45 hours less to 31.74 more) | ‐ | 258 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 4 | |

| Any drug‐related adverse events (CTCAE grade ≥ 2) | Study population | RD 0.00 (‐0.02 to 0.02) | 568 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 4 | ||

| No events were reported in either arm in any of the studies | ||||||

| Patient satisfaction on day of discharge (Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS)) Range: a higher score represents greater satisfaction |

The mean patient satisfaction in the control group on the day of discharge was 1.92 | The mean patient satisfaction in the Daikenchuto group on the day of discharge was 0.09 points higher (0.19 lower to 0.37 higher) | ‐ | 81 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 4 | |

| Incidence ratio of any re‐interventions before leaving hospital | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.06 to 15.62) | 207 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (1 to 152) | |||||

| Length of postoperative hospital stay (days) | The mean length of postoperative hospital stay for the control group was 17.37 days | The mean length of postoperative hospital stay for the Daikenchuto groups was 0.49 days lower (1.21 days lower to 0.22 days higher) | ‐ | 292 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 4 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CTCAE: Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; RD: risk difference; RR: risk ratio; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded by one level because of lack of blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessment

2 Downgraded by two levels because of a very small sample size

3 Downgraded by one level because of substantial heterogeneity

4 Downgraded by one level because of imprecision (95% confidence interval overlapped no effect)

Background

Description of the condition

Postoperative ileus refers to the atony of the bowel, and is characterised by delayed passage of flatus and faeces, due to delayed recovery of normal bowel peristalsis. It is frequently reported after abdominal surgery, and may cause clinical symptoms from minor complaints to significant and painful discomfort for the patient. Surgeons have discussed both the cause and treatment of postoperative ileus for more than two centuries, with the aim of reducing the burden it places on patients (Augestad 2010).

Bowel rest and fluid management are normally required for the initial management of ileus. However, pharmacotherapy, and even total parental nutrition, may be required for a protracted course of ileus. Surgery is not normally indicated for postoperative ileus, unless other conditions, such as mechanical obstruction or acute postoperative complications, require it. Such an intervention will most likely result in prolonged hospitalisation, which often causes other complications, such as hospital‐acquired pneumonia and thrombosis, decreased patient satisfaction, and increased healthcare costs (Behm 2003). While patients undergoing any type of surgery are at risk of postoperative ileus, those undergoing abdominal surgery are especially at risk of the condition (Augestad 2010). In the postoperative period, patients often use opioid or nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for analgesia, which could influence the normal bowel function (Holte 2000). Postoperative ileus occurs in at least 10% of colectomy surgeries. The presence of postoperative ileus is associated with a 15% increase in hospital costs (Iyer 2009).

Description of the intervention

In general, herbal medicines are low cost products of nature. When product packaging is marked 'Traditional herbal registration' (THR), the product complies with quality standards relating to safety and manufacturing, and provides information about how and when to use it.

Daikenchuto is a traditional Japanese herbal medicine (Kampo). Extracted granules containing processed ginger, ginseng, and Zanthoxylum fruit are its active components. This medicine is a 'standardised' herbal medicine, for which the proportion of the active components is always the same. Daikenchuto has been widely used for the treatment of postoperative ileus in Japan. It is taken orally two or three times per day, before or between meals, and few adverse events have been reported (Itoh 2002). Recently, it has also been used for other conditions, such as radiation‐induced enteritis (Takeda 2008), and constipation (Numata 2014). It has been asserted that Daikenchuto might prevent postoperative ileus (Mochiki 2010).

How the intervention might work

It is known that Daikenchuto has three major effects that promote intestinal motility and help to prevent ileus, thus helping to achieve earlier recovery after abdominal surgery. Firstly, Daikenchuto has an anti‐inflammatory effect, by inhibiting the activity of cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2; (Hayakawa 1999)), and up‐regulating endogenous adrenomedullin (Kono 2011). As several studies have strengthened the concept that cyclooxygenases (both COX‐1 and COX‐2 pathways) are involved in the modulation of gastrointestinal neuromuscular activity, and that changes in their regulatory activities occur in the presence of various digestive disorders, including postoperative ileus (Kono 2015), this could be an important pharmacological effect of Daikenchuto on postoperative ileus. Secondly, the prophylactic effect of Daikenchuto could be ascribed to its up‐regulating effect on calcitonin gene‐related peptide (CGRP), increasing intestinal blood flow (Kono 2008), and also increasing blood flow in the superior mesenteric artery (Takayama 2009), and portal vein (Ogasawara 2008). Thirdly, Daikenchuto has been reported to improve the slowed gastrointestinal motility caused by intestinal manipulation (Fukuda 2006). It has been reported that Daikenchuto stimulates upper gastrointestinal motility via cholinergic receptors (Jin 2001), and improves postoperative intestinal stasis through cholinergic nerves and 5‐HT4 receptors (Tokita 2007). It also reportedly induces both contraction and relaxation with the adjustment of acetylcholine, nitric oxide, and other excitatory neurotransmitters (Kito 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

Postoperative ileus is considered to be an inevitable complication of abdominal surgery, and as such, has elicited discussion on treatment, as well as prevention strategies (Kehlet 2001). Currently, Alvimopan, a peripherally‐acting μ‐opioid antagonist, is considered to be the only effective drug for the prevention of postoperative ileus. It has been reported that preoperative administration of this drug is effective without compromising analgesia (Wolff 2004). However, this drug is expensive to produce (Touchette 2012). Daikenchuto might be effective in the treatment of postoperative ileus, and might play an important role in prevention of the condition. As traditional herbal medicines, including Daikenchuto, are usually low cost treatments, they might be alternatives to existing treatments.

To our knowledge, there is no systematic review on the efficacy and safety of Daikenchuto as a potential prophylactic drug for preventing postoperative intestinal stasis.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of Daikenchuto for reducing prolonged postoperative ileus in persons undergoing elective abdominal surgery.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials (RCT), including cluster RCTs, with no restrictions on language or publication date.

We excluded quasi‐randomised trials, as their potential for bias is high. We also excluded studies with cross‐over design, as these are not appropriate for the assessment of treatments for acute conditions, including a perioperative period.

Types of participants

Age and sex

We included participants aged 18 years or older, of both sexes.

Diagnosis

We included participants undergoing elective abdominal organ surgery, either open or laparoscopic, regardless of epidural analgesia.

Setting

We included inpatients in the perioperative period.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

We included all administered doses of Daikenchuto, if it had been given orally and regularly, in either the preoperative or postoperative periods, or both.

Comparator interventions

Placebo

Drugs that stimulate intestinal motility, such as lactobacillus preparation, administered in the perioperative period

No treatment

We included any doses of intestinal stimulants, regardless of frequency or duration of therapy. To minimise clinical heterogeneity, we included only abdominal organ surgery. We did not include similar drugs, such as Dajianzhong (Chinese herbal medicine), which are derived from the same origin as Daikenchuto, but which have been developed in different ways.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Time from completion of operation to first flatus (hours)

Time from completion of operation to first bowel movement (hours)

Secondary outcomes

Time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food intake, regardless of quantity (hours)

Any drug‐related adverse events, for example incidence ratio of hepatobiliary dysfunction (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event (CTCAE) grade 2 or higher; moderate adverse events that require treatment)

Patient satisfaction (Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale after surgery)

Incidence ratio of re‐interventions, including surgical, endoscopic or radiological treatment, and decompression tubes for postoperative ileus before leaving hospital

Length of hospital stay (days)

There were no studies in which we found a composite endpoint, or co‐primary endpoints of a mixture of these outcomes. If a study uses the composite endpoint or co‐primary endpoint in future updates, we will contact the study author to ask for the outcome data separately. We were aware that the primary outcomes were reported in variable quality in the available literature. Patient reports of postoperative flatus and bowel movement might sometimes be of variable quality in the hours immediately following surgery, due to anaesthesia and strong opioids. Hence, the criteria used for measuring each outcome were appraised.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We conducted a comprehensive literature search, with no language restriction, by searching the following electronic databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 6) in the Cochrane Library (searched 3 July 2017; Appendix 1);

MEDLINE Ovid Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, MEDLINE Ovid Daily and MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 3 July 2017; Appendix 2);

Embase Ovid (1974 to week 27; Appendix 3);

ICHUSHI (1977 to 4 July 2017; Appendix 4);

WHO (World Health Organization) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; 6 July 2017);

EU Crinical Trials registry (EU‐CTR; 6 July 2017);

UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN‐CTR; 6 July 2017);

ClinicalTrials.gov (6 July 2017);

The Japan Society for Oriental Medicine (JSOM; 6 July 2017);

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO; 6 July 2017);

Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endscopic Surgeons (SAGES; 6 July 2017).

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all included studies to find additional studies that had been overlooked in the primary electronic searches. We searched citations in the Web of Science (3 July 2017) to find articles citing the included studies. We also searched the grey literature, using Google Scholar.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (NH, TT) independently assessed titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria. The same two authors obtained full‐text articles for studies that met the inclusion criteria. Duplicate publications of the same study were identified using author names, location and setting, specific details of interventions, numbers of participants and baseline data, and date and duration of the study, according to the recommendation in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We included studies irrespective of whether measured outcome data were reported. They resolved disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (NH, TT) independently extracted data from the included studies, checked the data for accuracy, and entered them into Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2014). Extracted data included:

study characteristics (design, single or multi‐centered, randomisation, number of arms, number of randomised participants, intervention, comparator, blinding)

participants' characteristics (age, sex, disease and its severity, surgical method, operative time, amount of intraoperative bleeding, epidural anaesthesia, opioid use, non‐steroid anti‐inflammatory drug use, laparoscopy)

administered intervention (drug, amount, duration)

outcomes (time from completion of operation to first flatus, time from completion of operation to first bowel movement, incidence ratio of hepatobiliary dysfunction, length of hospital stay, time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food intake, patient satisfaction, incidence ratio of any re‐interventions)

risk of bias and publication status

The two review authors resolved disagreements by discussion with a third review author. We contacted the study authors to obtain more information. We reported the level of agreement between the data extractors.

If multiple reports are found in future updates, we will extract data from all reports directly into a single data collection form.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (NH, TT) independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains:

random sequence generation

allocation concealment

blinding of participants and personnel

blinding of outcome assessment

incomplete outcome data

selective reporting

other bias (i.e. specific study design, fraudulent study, blinding of data analysts, co‐intervention, baseline imbalance in participant characteristics, influence of funders)

We classified each potential domain of bias as high, low, or unclear, and reported the agreement between the two review authors about the risk of bias as percentage agreement (see Appendix 5 for criteria). We resolved disagreements by discussion. We summarised the judgments of the risk of bias for each listed domain in a 'Risk of bias' table. We classified overall risk of bias as high when a study included two domains at high risk of bias, and as low when a study included five domains at low risk of bias. Otherwise, overall risk of bias was classified as unclear.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Dichotomous outcomes

We used risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). We employed risk difference (RD) with 95% CI when we did not calculate RR.

2. Continuous outcomes

We used the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI when the same outcome measure was reported. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI when different measures were used to evaluate the same outcome.

3. Change versus endpoint data

We used endpoint data, rather than change data.

Unit of analysis issues

To assess if there were unit of analysis issues, we checked each study for the way the randomisation had been carried out, e.g. if groups of individuals had been randomised together, and if individuals had undergone multiple interventions, or had multiple events. The unit of analysis was the individual participant, as we did not identify any cluster RCTs.

However, if we identify cluster‐randomised trials in future updates, we will include them in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions chapters 16.3.4 and 16.3.6, using an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial, or from a study involving a similar population (Higgins 2011). If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this, and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs, and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

We did not identify any studies including multiple treatment arms. Should we do so in future updates, we will include only the relevant arms. For dichotomous outcomes, when a study involves two 'different dosages of the same intervention' arms and a control arm, we will combine the data from the intervention arms into a single arm or split the data from the control arm equally. For continuous outcomes, we will combine means and standard deviations (SDs), as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the study authors or sponsors to obtain missing numerical outcome data.

1. Missing participants

We analysed all data based on the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) principle, as able. When participants had dropped out from the trial before the endpoint assessment, and the study authors had not imputed them properly, we analysed only the available data. We did not impute any data in this study. However, in future updates, we will describe any assumptions and imputations in the handling of missing data, and assess their effects using sensitivity analyses.

2. Missing statistics

We did not impute any missing statistics in this review. In future updates, we will calculate SDs only when the standard error (SE) or P values are reported (Altman 1996). If we cannot obtain additional data from the study authors, we will calculate the SDs from CIs, t values, or P values, according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), or impute them from other studies in the meta‐analysis, if possible (Furukawa 2006). We will assess the validity of these imputations in sensitivity analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity visually in forest plots and statistically with the Chi² test. We set P = 0.10 to determine statistical significance, because the Chi² test has low power to assess heterogeneity when studies have small sample sizes or are few in number (Higgins 2011). We also quantified heterogeneity using the I² statistic with the following interpretations: 0% to 40% low heterogeneity, 30% to 60% moderate heterogeneity, 50% to 90% substantial heterogeneity, and 75% to 100% considerable heterogeneity. We applied this for all outcomes as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

To minimise the influence of reporting biases, we conducted comprehensive searches using multiple sources, identifying unpublished trials, and including non‐English papers. We contacted study authors to obtain all outcomes regardless of whether they have been reported, as much as possible. Funnel plots were not applicable because there were fewer than 10 included studies. However, for all outcomes where 10 or more studies are available in future updates, we will construct funnel plots, regarding asymmetry on visual inspection, and Egger's linear regression test with P < 0.1 as evidence of small study effect (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

We used a fixed‐effect model for analysis of data unless there was substantial heterogeneity (I2 values ≥ 50%), in which case, we used the random‐effects model. If too few studies were identified to inform the distribution of effects, we used the fixed‐effect model (Higgins 2011). We used an inverse‐variance method for the random‐effects model and Mantel‐Haenszel method for the fixed‐effect model. We considered P < 0.05 to be significant. We used Trial Sequential Analysis (TSA 2011) to calculate enough sample size for the meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not perform subgroup analyses in this review because we did not include sufficient studies.

In future updates, we will perform subgroup analyses to investigate the observed heterogeneity. We plan to undertake subgroup analysis for:

participants who underwent gastrointestinal surgeries, such as colectomy or solid organ surgeries, such as liver resection,

elderly (≥ 70 years) versus non‐elderly (< 70 years) participants.

Subgroup analyses are exploratory and may yield false positive and false negative results, so we will apply these analyses to primary outcomes only, as these are likely to be reported in the majority of studies.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not perform sensitivity analyses in this review because we did not include sufficient studies.

To assess the robustness of our conclusions, we will carry out the following sensitivity analyses in future updates:

Risk of bias: we will exclude trials with a high risk of bias, such as inadequate random sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Imputing missing data: in trials with missing data, we will impute data according to the best or worst case scenario.

Non‐use of placebo: we will exclude trials without placebo.

Grey literature: we will exclude trials that have been listed as ongoing, and for which full reports have not been published.

Not administered in postoperative period: we will exclude trials in which Daikenchuto is not administered in the postoperative period.

Pharmaceutical sponsor: we will exclude studies from pharmaceutical companies because of an inevitable conflict of interest. When a pharmaceutical company provides the medication only, we will not classify such studies as industry sponsored.

Unusual dose or generic drugs: we will exclude studies examining unusual doses of Daikenchuto or generic drugs. The normal adult dosage is between 7.5 g and 15 g given as two or three daily doses.

'Summary of findings' tables

We analysed the quality of evidence of all our outcomes using the GRADE approach, and presented it in a 'Summary of findings' table (Chapter 12.2.1, Higgins 2011). These tables present key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effects of interventions examined, and the sum of available data for the main outcomes.

The GRADE system classifies the quality of evidence in one of four grades:

High: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect,

Moderate: Further research is likely to have an impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate,

Low: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate, or

Very low: Any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

For randomised controlled trials, the quality of evidence was downgraded by one (serious concern) or two levels (very serious concern) for the following reasons: risk of bias, inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity, inconsistency of results), indirectness (indirect population, intervention, control, outcomes), imprecision (wide confidence intervals), and other considerations, including publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified 2408 references through the searches, and removed 317 duplicates between CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase. We examined titles and abstracts of 2091 references, and excluded 2065 clearly irrelevant references or duplicates among all databases. We assessed the remaining 26 references according to our inclusion criteria. Eight were ongoing studies (in nine references, see Characteristics of ongoing studies). We assessed the full text of the remaining 17 references. We excluded nine studies (nine references) with reasons, which we listed in Characteristics of excluded studies. Finally, we included seven studies (in eight references) in our analyses (see Characteristics of included studies). We presented the results of our searches in a PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

Characteristics of the trial design and settings

All seven studies were of parallel design, had two arms, and were conducted in Japan. There were five multicenter, and two single‐centre studies (Nishi 2012; Yaegashi 2014). All seven studies reported the study duration, which ranged from 12 to 30 months.

Five studies reported the details of sample size calculation: two of these studies achieved their required sample size (Shimada 2015, Yaegashi 2014), three studies did not (Katsuno 2015; Okada 2016; Yoshikawa 2015). The remaining two studies did not report their sample size calculation.

Five studies reported the funding source. Three studies were funded by the Japanese Foundation for Multidisciplinary Treatment of Cancer (Katsuno 2015; Shimada 2015; Yoshikawa 2015), one study by the Epidemiological and Clinical Research Information Network (Okada 2016), and one study by a pharmaceutical company, Tsumura & Co. (Akamaru 2015). The remaining two studies did not report the funding source (Nishi 2012; Yaegashi 2014).

Five studies mentioned authors' conflicts of interest. Three studies reported the authors' conflicts of interests (Okada 2016; Shimada 2015; Yoshikawa 2015), and two studies declared that there were none (Akamaru 2015; Katsuno 2015). The remaining two studies did not mention conflicts of interest.

The trial protocol was available for five of the seven studies (Akamaru 2015; Katsuno 2015; Okada 2016; Shimada 2015; Yoshikawa 2015), but one of them was registered after the first participant was recruited (Akamaru 2015).

Characteristics of the participants

There were 1202 participants included in the seven RCTs; 608 were allocated to the intervention, and 594 to the comparator group. Age ranged from 28 to 91 years across studies, with median or mean ages ranging from 67 to 69 years. Five studies included more males than females, while two studies included more females than males (Okada 2016; Yaegashi 2014).

Disease, its severity and surgical method

Two studies were of people with colon cancer who underwent curative colectomy (Katsuno 2015; Yaegashi 2014). Two studies were of people with gastric cancer, who underwent total gastrectomy with D2 dissection and Roux‐en‐Y reconstruction (Japanese Gastric Cancer Association 2011); one of which was a curative resection (Akamaru 2015), and the other included both curative and non‐curative resections (Yoshikawa 2015). Two studies involved people with liver tumours who underwent hepatic resection (Nishi 2012; Shimada 2015). One study involved people with periampullary tumours and tumours of the head of the pancreas, who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (Okada 2016).

Operative time and amount of intraoperative bleeding

All seven studies reported median or mean operative time, which ranged from 174 to 419 minutes. All seven studies reported median or mean amount of intraoperative bleeding, which ranged from 12 to 764 mL.

Epidural anaesthesia

Three studies reported on the use of epidural anaesthesia; the rate ranged from 59.6% to 90.9% (Katsuno 2015; Okada 2016; Yoshikawa 2015). The remaining four studies did not mention the use of epidural anaesthesia.

Opioid and nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID) use

There were no studies that referred to the use of opioids or NSAIDs. We contacted study authors; two of them replied that they did not collect data on opioid and NSAID use (Katsuno 2015; Yaegashi 2014).

Laparoscopy

Four studies did not use laparoscopic surgery (Katsuno 2015; Nishi 2012; Shimada 2015; Yoshikawa 2015), one study used only laparoscopic surgery (Yaegashi 2014), and ne study reported the proportion of laparoscopic surgery, which ranged from 41.5% to 42.5% (Akamaru 2015). One study did not mention the use of laparoscopy (Okada 2016).

Characteristics of the interventions and comparisons

Four studies compared 15 g/day of Daikenchuto against 15 g/day of placebo (Katsuno 2015; Okada 2016; Shimada 2015; Yoshikawa 2015). One study compared 7.5 g/day of Daikenchuto against 3 g/day of lactobacillus preparation (Yaegashi 2014). The remaining two studies compared 7.5 g/day of Daikenchuto against no treatment (Akamaru 2015; Nishi 2012).

The durations of intervention were within one month in five studies (Katsuno 2015; Okada 2016; Shimada 2015; Yaegashi 2014; Yoshikawa 2015). The duration of intervention was three months in one study (Akamaru 2015), and unclear in another study, because the end date of administration was not reported (Nishi 2012).

In four studies, the intervention was given both preoperatively and postoperatively (Akamaru 2015; Katsuno 2015; Nishi 2012; Yoshikawa 2015). In the remaining three studies, it was given only postoperatively.

Characteristics of primary outcomes

Time from completion of operation to first flatus

Four studies reported the time from completion of operation to first flatus (Nishi 2012; Okada 2016; Yaegashi 2014; Yoshikawa 2015). Two of them reported the time from extubation on an hourly basis (Yaegashi 2014; Yoshikawa 2015), and the others reported the time from the day of surgery in days (Nishi 2012; Okada 2016). Among these studies, two studies reported a mean and standard deviation for each group (Nishi 2012; Yaegashi 2014), while the others reported a median with range or 97.5% confidence interval (Okada 2016; Yoshikawa 2015). We contacted the study authors but did not obtain additional information.

One study reported the time from removal of nasogastric tube to first flatus on an hourly basis (Katsuno 2015). We did not include this study in the analysis.

Time from completion of operation to first bowel movement

Six studies reported the time to first bowel movement (Akamaru 2015; Katsuno 2015; Nishi 2012; Shimada 2015; Yaegashi 2014; Yoshikawa 2015). Four of them reported the time from extubation on an hourly basis (Katsuno 2015; Shimada 2015; Yaegashi 2014; Yoshikawa 2015), and the others reported the time from the day of surgery in days (Akamaru 2015; Nishi 2012). Among these studies, three studies reported a mean and standard deviation for each group (Akamaru 2015; Nishi 2012; Yaegashi 2014). However, the others reported a median and 95% confidence interval (Shimada 2015), a median and range (Yoshikawa 2015), or Kaplan‐Meier curve (Katsuno 2015). We contacted the study authors, and obtained the result in a mean and standard deviation from one author (Katsuno 2015).

Characteristics of secondary outcomes

Time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food intake, regardless of quantity

Two studies reported the time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food intake (Okada 2016; Yaegashi 2014). One of them reported the time from extubation on an hourly basis (Yaegashi 2014), and the other reported the time from the day of surgery in days (Okada 2016). Both studies reported a mean and standard deviation for each group.

One study reported the time from the day of surgery to the day of full recovery of oral intake (Nishi 2012). We did not include this study in the analysis.

Any other adverse events (drug‐related, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event (CTCAE grade ≥2))

Five studies reported that there were no drug‐related adverse events (Akamaru 2015; Nishi 2012; Shimada 2015; Yaegashi 2014; Yoshikawa 2015).

Patient satisfaction

Four studies reported the scores regarding participants' quality of life (Akamaru 2015; Katsuno 2015; Okada 2016; Yoshikawa 2015). Among these studies, one study used the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy for patients with Gastric cancer (FACT‐Ga; (Yoshikawa 2015)), one study used GSRS and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy for patients with Colorectal cancer (FACT‐C; (Katsuno 2015)), one study used the GSRS and visual analogue scale (Okada 2016), and the remaining study used only GSRS (Akamaru 2015). Therefore, we decided to pool the results using the GSRS to assess the quality of life after surgery.

One study reported GSRS scores at four time points, such as the day before the surgery, the day of discharge, one month after the surgery, and three months after the surgery (Akamaru 2015). We decided to apply the score at the day of discharge. Three studies reported that there was no difference across groups, and did not report the details of the score (Katsuno 2015; Okada 2016; Yoshikawa 2015). We contacted the study authors but did not obtain additional information.

Incidence ratio of re‐interventions including surgical, endoscopic or radiological treatment, and decompression tubes for postoperative ileus before leaving hospital

Only one study reported the incidence ratio of re‐interventions for postoperative ileus before leaving hospital (Okada 2016).

Two studies reported the incidence ratio of postoperative ileus, but did not report on re‐interventions (Akamaru 2015; Shimada 2015). We contacted the study authors but did not obtain additional information.

Length of hospital stay

Five studies reported the length of hospital stay (Nishi 2012; Okada 2016; Shimada 2015; Yaegashi 2014; Yoshikawa 2015). Among these studies, three reported a mean and standard deviation for each group (Nishi 2012; Shimada 2015; Yaegashi 2014), one study reported a median and 95% confidence interval (Okada 2016), and one study reported that there was no significant difference across groups, but did not report the details of the data (Yoshikawa 2015). We contacted the study authors but did not obtain additional information.

Excluded studies

We excluded nine studies (nine references) from this review for the following reasons.

three studies were non‐RCTs (historical cohort: Kaiho 2004, Sasaki 1998, retrospective study: Kaiho 2015)

five studies were quasi‐RCTs (Fujii 2011, Naka 2002, Osawa 2015, Suehiro 2005, Yoshikawa 2012)

one study included pelvic surgery (Takagi 2007)

Risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (NH, TT) independently assessed risk of bias in the included studies. The agreement of their assessments was 71%, and they achieved 100% agreement after discussion.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Three studies adequately described the method of random sequence generation (Akamaru 2015; Nishi 2012; Yaegashi 2014), and were judged to have a low risk of bias for this domain.

Four studies did not describe how the random sequence allocation was generated. We contacted the study authors, and one study author replied that a random number table was used (Katsuno 2015). Therefore, we judged this study to be at low risk of bias and the others to be at unclear risk of bias in this domain.

Allocation concealment

Six studies adequately described the method of allocation concealment (Katsuno 2015; Nishi 2012; Okada 2016; Shimada 2015; Yaegashi 2014; Yoshikawa 2015), and were judged to have a low risk of bias for this domain.

One study did not describe the method of allocation concealment. We contacted the study author, but we did not obtain any additional information. Therefore, we judged this study to be at unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

Three studies were described as 'double blind ‐ all involved were blinded' (Katsuno 2015; Shimada 2015; Yoshikawa 2015). One study described that participants and investigators were blinded (Okada 2016). We judged these studies to be at low risk of bias for this domain.

Three studies did not use placebos, and it was impossible to blind the participants and personnel. We judged these studies to be at a high risk of bias for this domain.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

Three studies were described as 'double blind ‐ all involved were blinded' (Katsuno 2015; Shimada 2015; Yoshikawa 2015). We judged these studies to be at low risk of bias for this domain.

Three studies did not use placebos, and there was no mention of blinding of outcome assessment. We judged these studies to be at high risk of bias for this domain.

One study did not describe blinding of outcome assessment (Okada 2016). We contacted the study author but did not obtain any additional information.Therefore, we judged this study to be at unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Incomplete outcome data

There were no missing participants in one study (Nishi 2012). Six studies described reasonable reasons for excluded participants, such as: retraction of agreement to the trial, change of a surgical procedure, and inability to take medicines due to postoperative complications, including anastomotic leakage and high fever. The number of dropouts were relatively small (3 to 22 dropouts in each study) and well‐balanced between intervention and comparator groups in the other six studies. We judged all seven studies to be at low risk of bias for this domain.

Selective reporting

Four studies had been registered in UMIN‐CTR or Clinical Trial.gov, and we did not find any selective reporting (Katsuno 2015; Okada 2016; Shimada 2015; Yoshikawa 2015). We judged these studies to be at low risk of bias for this domain.

One study was registered in UMIN‐CTR after the starting date (Akamaru 2015), and two studies were not registered anywhere (Nishi 2012; Yaegashi 2014). We judged these studies to be at unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify other potential sources of bias, and judged all studies involved to be at low risk of bias for this domain.

Overall risk of bias

We judged four studies to be at low overall risk of bias (Katsuno 2015; Okada 2016; Shimada 2015; Yoshikawa 2015), whereas the remaining studies were judged to be at high overall risk of bias due to lack of blinding (Figure 2; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See Table 1.

Time from completion of operation to first flatus, first bowel movement, or resumption of regular solid food intake was reported in both days or hours. We converted the number of days to hours by multiplying by 24.

Primary outcomes

Time from completion of operation to first flatus (hours)

Two studies (83 participants) reported on time from completion of operation to first flatus. Overall, the time was shortened by using Daikenchuto (mean difference (MD) ‐11.32 hours, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐17.45 to ‐5.19; I² = 0%; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1). We downgraded the quality by three levels because of risk of bias (lack of blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessment), and imprecision (very small sample size).

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Daikenchuto versus control, Outcome 1 Time from completion of operation to first flatus (hours).

Time from completion of operation to first bowel movement (hours)

Four studies (500 participants) reported time from completion of operation to first bowel movement. Overall, the time was not significantly shortened by using Daikenchuto (MD ‐9.44 hours, 95% CI ‐22.22 to 3.35; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.2). There was substantial heterogeneity (I² = 66%). We downgraded the quality by three levels because of risk of bias (lack of blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessment), inconsistency (substantial heterogeneity), and imprecision (95% CI overlapped no effect).

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Daikenchuto versus control, Outcome 2 Time from completion of operation to first bowel movement (hours).

We further assessed this result using Trial Sequential Analysis. We set two‐sided alfa = 0.05 and beta = 0.20, and conducted the analysis. Cummurative Z‐curve did not cross the monitoring boundary and did not reach the required Imformation size (N = 1875). Thus, we considered that the result could be a false negative (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Trial Sequential Analysis for time from completion of operation to first bowel movement

Secondary outcomes

Time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food intake (hours)

Two studies (258 participants) reported on time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food intake, regardless of quantity. There was no clear effect of Daikenchuto (MD 3.64 hours, 95% CI ‐24.45 to 31.74; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.3). There was substantial heterogeneity (I² = 63%). We downgraded the quality by three levels because of risk of bias (lack of blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessment), inconsistency (substantial heterogeneity), and imprecision (small sample size, 95% CI overlapped no effect).

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Daikenchuto versus control, Outcome 3 Time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food intake (hours).

Any drug‐related adverse events

Five studies (568 participants) reported that there were no drug‐related adverse events in either arm of the trials. Because it is statistically problematic to pool the data to calculate risk ratio (RR) when the number of events is zero in all arms, we decided to calculate risk difference (RD). The estimated RD was 0.00 (95% CI: ‐0.02 to 0.02; I² = 0%; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.4). We downgraded the quality by two levels because of risk of bias (lack of blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessment), and imprecision (small sample size, 95% CI overlapped no effect).

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Daikenchuto versus control, Outcome 4 Any drug‐related adverse events.

Patient satisfaction on the day of discharge (Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS))

One study (81 participants) reported the quality of life score. The use of Daikenchuto did not significantly improve patient satisfaction (mean difference (MD) 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.37; Analysis 1.5). Three studies reported that there were no significant differences in quality of life between intervention and control groups, but did not report the data. We judged the quality of evidence as very low. We downgraded it by three levels because of risk of bias (lack of blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessment), and imprecision (very small sample size, 95% CI overlapped no effect).

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 Daikenchuto versus control, Outcome 5 Patient satisfaction.

Incidence ratio of any re‐interventions before leaving hospital

One study (207 participants) reported the incidence ratio of re‐interventions for postoperative ileus, and found no clear difference between the Daikenchuto and comparator groups (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.62; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.6). We downgraded the quality by one level because of imprecision (small sample size, 95% CI overlapped no effect).

Analysis 1.6.

Comparison 1 Daikenchuto versus control, Outcome 6 Incidence ratio of any re‐interventions before leaving hospital.

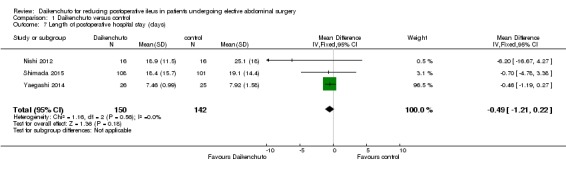

Length of hospital stay (days)

Three studies (292 participants) reported length of hospital stay. There was no significant difference between the Daikenchuto and comparator groups (MD ‐0.49 days, 95% CI ‐1.21 to 0.22; I² = 0%; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.7). We downgraded the quality by two levels because of risk of bias (lack of blinding of participants and personnel), and imprecision (small sample size, 95% CI overlapped no effect).

Analysis 1.7.

Comparison 1 Daikenchuto versus control, Outcome 7 Length of postoperative hospital stay (days).

Discussion

Summary of main results

We identified and included seven RCTs (1202 participants) that met our eligibility criteria.

We found that the use of Daikenchuto decreased the time from completion of operation to first flatus with a mean difference (MD) of ‐11.32 hours (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐17.45 to ‐5.19; I² = 0%; two randomised controlled trials (RCT), 83 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). The number of participants was very small, and we could not judge the clinical meaningfulness of this level of reduction.

Overall, the time from completion of operation to first bowel movement was not significantly shortened by using Daikenchuto (MD ‐9.44 hours, 95% CI ‐22.22 to 3.35; I² = 66%; four RCTs, 500 participants; very low‐certainty evidence. The number of participants was small, and we could not judge the clinical meaningfulness of this level of reduction.

There was no clear effect of Daikenchuto on the time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food intake (MD 3.64 hours, 95% CI ‐24.45 to 31.74; I² = 63%; two RCTs, 258 participants; very low‐certainty evidence. The number of participants was small, and there was no clear difference between intervention and comparator groups.

None of the five trials (568 participants) that measured severe or drug‐related adverse events identified any (risk difference (RD) 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.02; I² = 0%; low‐certainty evidence).

There was no clear difference between the Daikenchuto and comparator groups for patient satisfaction, measured with the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale on the day of discharge (MD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.37; one RCT, 81 participants; very low‐certainty evidence).

There was no clear difference between the Daikenchuto and comparator groups in the incidence of re‐interventions for postoperative ileus before leaving hospital (risk ratio (RR) 0.99, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.62; one RCT, 207 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence).

There was no significant difference in the length of hospital stay between the Daikenchuto and comparator groups (MD ‐0.49 days, 95% CI ‐1.21 to 0.22; I² = 0%; three RCTs, 292 participants; low‐certainty evidence). The number of participants was small, and we could not judge the clinical meaningfulness of this level of reduction.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In this review, we tried to investigate the impact of Daikenchuto on reducing postoperative ileus. However, we did not set the incidence ratio of postoperative ileus as an outcome, because we considered that the definition of postoperative ileus was diverse across studies. Instead, we set several surrogate outcomes to evaluate the efficacy of Daikenchuto, but various outcomes were used across the studies, and there were a small number of studies that measured each outcome. This review included potential heterogeneity because different abdominal diseases were included in the studies (i.e. gastric cancer, colon cancer, liver cancer, and pancreatic cancer). In addition, different doses of Daikenchuto and comparator drugs were administered. Four studies used 15 g/day of Daikenchuto, and three studies used 7.5 g/day of Daikenchuto. Four studies compared it to placebo, one study used 3 g/day of lactobacillus preparation, and two studies did not use a comparator drug. We had planned to perform several subgroup analyses to improve the applicability, but we were unable to, because of the small number of studies that measured each outcome.

We had hypothesized the potential for some confounding factors, such as operative time, amount of intraoperative bleeding, use of epidural anaesthesia, opioids, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and laparoscopy. No studies reported the use of opioids or NSAIDs. All studies were performed in Japan and included only cancer patients. Therefore, the results of this review may not be applicable to all types of abdominal disease, or patients in other countries.

Quality of the evidence

This review included seven RCTs and randomised 1202 participants, 1111 participants of whom were included in the analyses. We assessed the quality or certainty of the evidence for each outcome using GRADE methodology, and in general, considered it to be low to very low. This was mainly due to serious risk of bias in the included studies and imprecision. All but one of the studies provided insufficient details on randomisation, allocation concealment, or blinding. For most outcomes, we could only include a few studies in each meta‐analysis, resulting in small sample sizes, and 95% CI that crossed the line of no effect in all but one analysis. Therefore, we were not able to fully investigate the precise effect of Daikenchuto.

We had planned to explore the possibility of publication bias, but none of the outcomes were measured by 10 or more studies. If we are able to include more than 10 trials in future updates, we will explore this further, following the methods recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Chapter 10.4.1, Sterne 2011).

Potential biases in the review process

We searched for relevant studies in all the main electric databases, in an effort to minimize potential publication bias. However, we only identified seven studies. Some continuous outcomes were only reported as P values, some were described as 'not significant', and others only provided a Kaplan‐Meier curve, so we could not impute these missing values. This might have affected the results of the meta‐analyses.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

As far as we could determine, there were no systematic reviews regarding the efficacy of Daikenchuto. Fujii 2011 reported that time to first bowel movement was significantly reduced by Daikenchuto, while time to first bowel movement was not in their quasi‐RCT, which agree with the results of this review.

One Cochrane Review found low‐quality evidence that the use of chewing gum significantly shortened time to first flatus (‐10.4 hours, 95% CI ‐11.9 to ‐8.9), and first bowel movement (‐18.1 hours, 95% CI ‐25.3 to ‐10.9; (Short 2015)). Traut 2008 explored the prokinetic effects of Alvimopan, and found that it had a significantly large effect on time to first bowel movement (HR 1.70, 95% CI 1.43 to 2.02), but it did not show a significant effect on time to first flatus (HR 1.67, 95% CI 0.86 to 3.23). Quality of evidence in this review was not reported. Recently, Ehlers 2016 reported that Alvimopan was associated with a shorter length of hospital stay (0.9 days), while there remains several problems in Alvimopan including its high cost, limited use, and severe adverse events including myocardial infarction (Nair 2016; Kraft 2010). Therefore, chewing gum and Alvimopan are potential interventions to improve postoperative ileus, but similar to our findings of the effect of Daikenchuto, lack high‐quality evidence.

Authors' conclusions

In this review, we assessed the efficacy of Daikenchuto for postoperative ileus. Based on the current literature, we are uncertain whether Daikenchuto reduces time to first flatus or time to first bowel movement. There may be little or no difference in time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food. We are uncertain of the effect of Daikenchuto on patient satisfaction. There is probably little or no difference in the incidence of re‐intervention for postoperative ileus before leaving hospital or length of hospital stay. No adverse events were reported in either arm in any of the included studies.

We included seven RCTs with 1202 participants in this review, but the efficacy of Daikenchuto was not fully assessed. Larger numbers of participants are necessary. All seven studies included in this review assessed the time to first flatus or bowel movement. These outcomes are important to assess the impact of Daikenchuto on intestinal movement. However, few studies reported more clinically important outcomes, including re‐interventions and quality of life. We hope that future trials assess these outcomes to evaluate the clinical benefit for patients. Most of the included studies compared Daikenchuto with placebo or no treatment. We are interested in the comparison with other effective interventions such as chewing gum and Alvimopan.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group editorial office, editors, and referees for the support and constructive input they have provided.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 6) in The Cochrane Library (searched 3 July 2017; 54 hits) #1 (daikenchuto or dai‐kenchu‐to or dai‐ken‐chu‐to or DKT or TJ‐100 or TU‐100):ti,ab,kw

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) (1946 to 3 July 2017; 230 hits) 1. (daikenchuto or dai‐kenchu‐to or dai‐ken‐chu‐to or DKT or TJ‐100 or TU‐100).mp

Appendix 3. Embase search strategy

Embase Ovid (1974 to 3 July 2017; 450 hits) 1. (daikenchuto or dai‐kenchu‐to or dai‐ken‐chu‐to or DKT or TJ‐100 or TU‐100).mp.

Appendix 4. ICHUSHI search strategy

Igaku Chuo Zasshi (ICHUSHI) (1977 to 3 July 2017; 1458 hits) 1. (daikenchuto or dai‐kenchu‐to or dai‐ken‐chu‐to or DKT or TJ‐100 or TU‐100).mp.

Appendix 5. Criteria for judging risk of bias in the 'Risk of bias' assessment tool

| Random sequence generation: selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomized sequence | |

| Criteria for a judgement of low risk of bias | The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as:

*Minimisation may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random. |

| Criteria for a judgement of high risk of bias | The investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process. Usually, the description would involve some systematic, non‐random approach, for example:

Other non‐random approaches happen much less frequently than the systematic approaches mentioned above and tend to be obvious. They usually involve judgement, or some method of non‐random categorisation of participants, for example:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of unclear risk of bias | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement of low risk or high risk. |

| Allocation concealment: selection bias (biased allocation to intervention) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment | |

| Criteria for a judgement of low risk of bias | Participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of high risk of bias | Participants or investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignment and thus introduce selection bias, such as allocation based on:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of unclear risk of bias | Insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk. This is usually the case if the method of concealment is not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement – for example if the use of assignment envelopes is described, but it remains unclear whether envelopes were sequentially‐numbered, opaque and sealed. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel: performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study | |

| Criteria for a judgement of low risk of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of high risk of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of unclear risk of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Blinding of outcome assessment: detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors | |

| Criteria for a judgement of low risk of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of high risk of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of unclear risk of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Incomplete outcome data: attrition bias due to amount, nature, or handling of incomplete data | |

| Criteria for a judgement of low risk of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of high risk of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of unclear risk of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Selective reporting: reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting | |

| Criteria for a judgement of low risk of bias | Any of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of high risk of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of unclear risk of bias | Insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk. It is likely that the majority of studies will fall into this category. |

| Other bias: bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table | |

| Criteria for a judgement of low risk of bias | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| Criteria for a judgement of high risk of bias | There is at least one important risk of bias. For example, the study:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of unclear risk of bias | There may be a risk of bias, but there is either:

|

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Daikenchuto versus control

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Time from completion of operation to first flatus (hours) | 2 | 83 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐11.32 [‐17.45, ‐5.19] |

| 2 Time from completion of operation to first bowel movement (hours) | 4 | 500 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐9.44 [‐22.22, 3.35] |

| 3 Time from completion of operation to resumption of regular solid food intake (hours) | 2 | 258 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.64 [‐24.45, 31.74] |

| 4 Any drug‐related adverse events | 5 | 568 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.02, 0.02] |

| 5 Patient satisfaction | 1 | 81 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.09 [‐0.19, 0.37] |

| 6 Incidence ratio of any re‐interventions before leaving hospital | 1 | 207 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.06, 15.62] |

| 7 Length of postoperative hospital stay (days) | 3 | 292 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.49 [‐1.21, 0.22] |

Differences between protocol and review

'N 100' was excluded from search terms.

Any other adverse events (drug‐related) was evaluated using RD instead of RR.

There were, at most, four studies included in each meta‐analyses to investigate the efficacy of Daikenchuto. Therefore, Trial Sequential Analysis was only used to calculate adequate sample size for the meta‐analysis of time from completion of operation to first bowel movement.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Trial design: parallel (two arms) Location: Japan Number of centres: eight Study duration: September 2007 to December 2009 |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: histologically confirmed stage I, II, or III gastric cancer with a plan to undergo total gastrectomy with a D2 dissection (permitting preservation of the spleen), Roux‐en‐Y reconstruction and R0 surgery (Japanese Gastric Cancer Association 2011); no previous cancer treatment or past history of any other cancer; age between 20 to 80 years; an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1; adequate organ functions Exclusion criteria: any hepatic, peritoneal, or distant metastasis; any positive tumour cells in cytological examinations of peritoneal fluids; emergency surgery; other active malignancies; morbid cardiopulmonary disease; severe liver‐kidney dysfunction; a history of laparotomy (except appendectomy); intestinal obstruction Age (years): Gp I: 63.4 ± 8.9 (range 32 to 77); Gp C: 63.7 ± 9.2 (range 40 to 78) Sex: Gp I: 75.6% male; Gp C: 67.5% male Disease and its severity: gastric cancer (stage IA: Gp I: 46.3%; Gp C: 42.5%; stage IB: Gp I: 17.1%: Gp C: 7.5%; stage II: Gp I: 14.6%; Gp C: 20.0%; stage IIIA: Gp I: 14.6%; Gp C: 22.5%; stage IIIB: Gp I: 7.3%; Gp C: 7.5%) Surgical method: total gastrectomy with a D2 dissection and Roux‐en‐Y reconstruction Operative time (min): Gp I: 252 ± 56; Gp C: 254 ± 54 Amount of intraoperative bleeding (mL): Gp I: 406 ± 422; Gp C: 341 ± 395 Epidural anaesthesia: not reported Opioid use: not reported Non‐steroid anti‐inflammatory drug use: not reported Laparoscopy: Gp I: 41.5%; Gp C: 42.5% Number randomised: 100 (Gp I: 51; Gp C: 49) Number evaluated: 81 (Gp I: 41; Gp C: 40) |

|

| Interventions | Comparison: Daikenchuto versus no treatment Intervention group (Gp I): 2.5 g of Daikenchuto, taken orally with 20 mL tepid water three times per day, starting the day after operation, when oral intake was allowed Comparator group (Gp C): 20 mL tepid water three times per day Prokinetics drugs were restricted during the study period including acetylcholine agonists, serotonin agonists, dopamine antagonists, cholinesterase inhibitors, or prostaglandin F2 alpha. |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Analysis method: per protocol analysis Administration route: oral Treatment compliance: not reported Sample size calculation: not reported Funding: "This study was supported by a grant‐in‐aid from Tsumura & Co., Tokyo, Japan" Declarations/ conflicts of interest: "All authors declare no conflict of interest or financial ties that might have influenced the findings of this study" |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Numbered container method" in UMIN Clinical Trials Registry Comments: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Quote: "This was an open‐labeled prospective randomised trial" Comments: impossible to blind |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Quote: "This was an open‐labeled prospective randomised trial" Comments: impossible to blind |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Reasonable reasons for exclusion were reported and the number of dropouts was relatively small and well‐balanced between groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | This study was registered after the starting date. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias were apparent |

| Methods | Trial design: parallel (two arms) Location: Japan Number of centres: 51 Study duration: January 2009 to June 2011 |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: colon cancer patients; curative colonic open resection; TNM stage I, II, IIIa, or IIIb (Washington 2010); a performance status of 0 to 1, able to tolerate oral administration of Daikenchuto; aged 20 years or older; man or woman; able to stay in hospital during the entire length of study period Exclusion criteria: scheduled for endoscopic or laparoscopic surgery; complicated inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease); emergency surgery; double cancer; serious liver or renal disorder; a history of laparotomy and peritonitis (excluding surgery for appendicitis); pregnant, possibly pregnant, lactating or considering pregnancy; unfit for the study as determined by the attending physician Age (years): Gp I: 68 (range 28 to 88); Gp C: 69 (range 35 to 91) Sex: Gp I: 56.3% male; Gp C: 61.1% male Disease and its severity: Colon cancer: T (T1: Gp I: 1.7%; Gp C: 6.2%; T2: Gp I: 5.7%; Gp C: 8.0%; T3: Gp I: 87.9%; Gp C: 80.2%; T4: Gp I: 4.6%; Gp C: 4.3%; N0: Gp I: 49.4%; Gp C: 51.2%; N1: Gp I: 36.2%; Gp C: 34.0%; N2: Gp I: 9.8%; Gp C: 11.7%; N3: Gp I: 4.6%; Gp C: 3.1%; M0: Gp I: 99.4%; Gp C: 0.6%; M1: Gp I: 99.4%; Gp C: 0.6%) Surgical method: ileocecal resection: Gp I: 7.5%; Gp C: 6.8%; right hemicolectomy: Gp I: 23.6%; Gp C: 21.0%; left hemicolectomy: Gp I: 6.9%; Gp C: 4.9%; sigmoidectomy: Gp I: 20.7%; Gp C: 9.3%; anterior resection: Gp I: 33.3%; Gp C: 22.8%; partial resection: Gp I: 5.7%; Gp C: 8.0% Operative time (hr): Gp I: 2.91 ± 0.89; Gp C: 3.00 ± 1.00 Amount of intraoperative bleeding (mL): Gp I: 202.5 ± 226.9; Gp C: 222.9 ± 265.5 Epidural anaesthesia: Gp I: 86.2%; Gp C: 85.8% Opioid use: not reported Non‐steroid anti‐inflammatory drug use: not reported Laparoscopy: none Number randomised: (Gp I: 181; Gp C: 173) Number evaluated: (Gp I: 174; Gp C: 162) |

|

| Interventions | Comparison: Daikenchuto versus placebo Intervention group (Gp I): oral doses of 15 g /day (5 g three times a day) of Daikenchuto from postoperative day 2 to 8 Comparator group (Gp C): oral doses of 15 g /day (5 g three times a day) of placebo from postoperative day 2 to 8 |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Analysis method: per protocol analysis Adminiatration route: oral Treatment compliance: not reported Sample size calculation: based on the assumptions, 200 participants were needed per group to provide 81% power to detect a difference at the 5% level of significance in a two‐sided test Funding: "The study was supported by the Japanese Foundation for Multidisciplinary Treatment of Cancer" Declarations/ conflicts of interest: "None declared" |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Block randomisation was performed by the JFMC 39‐0902 data centre." Comments: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Eligibility criteria checking report forms were sent to the JFMC 39‐0902 data centre. Patients were allocated randomly and registered into two arms" Comments: probably done |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, randomised, exploratory trial" Comments: 'double' included participants and personnel |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Double‐blind ‐ all involved are blind" in UMIN Clinical Trials Registry Comments: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Reasonable reasons for exclusion were reported and the number of dropouts was relatively small and well‐balanced between groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No findings were identified to suggest selective reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias were apparent |

| Methods | Trial design: parallel (two arms) Location: Japan Number of centres: one Study duration: July 2007 to August 2008 |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: hepatic resection; age 18 to 80; performance status 0 to 1 Exclusion criteria: hepatojejunostomy; splenectomy; ablation therapy; laparoscopic surgery; colorectal surgery; other surgeries Age (years): Gp A: 68.8 ± 8.7; Gp B: 64.3 ± 7.3 Sex: Gp I: 75.0% male; Gp C: 56.3% male Disease and its severity: diagnosis (primary liver cancer: Gp I: 62.5%; Gp C: 31.3%; metastatic liver cancer: Gp I: 31.3%; Gp C: 37.5%: others: Gp I: 6.3%; Gp C: 31.3%); background liver (liver cirrhosis: Gp I: 25.0%; Gp C: 18.8%; liver fibrosis/chronic hepatitis: Gp I: 31.3%; Gp C: 18.8%: normal liver: Gp I: 43.8%; Gp C: 62.5%) Surgical method: lobectomy: Gp I: 18.8%; Gp C: 43.8%; segmentectomy: Gp I: 31.3%; Gp C: 25.0%; smaller than segmentectomy: Gp I: 50.0%; Gp C: 31.3% Operative time (min): Gp I: 300 ± 50; Gp C: 321 ± 110 Amount of intraoperative bleeding (mL): Gp I: 273 ± 156; Gp C: 241 ± 122 Epidural anaesthesia: not reported Opioid use: not reported Non‐steroid anti‐inflammatory drug use: not reported Laparoscopy: none Number randomised: (Gp I: 16; Gp C: 16) Number evaluated: (Gp I: 16; Gp C: 16) |

|

| Interventions | Comparison: Daikenchuto versus no treatment Intervention group (Gp I): 2.5 g of Daikenchuto, from the morning of postoperative day 1 via nasal gastric tube, and thereafter orally three times a day Comparator group (Gp C): no treatment |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Analysis method: per protocol analysis Adminiatration route: 'via nasal gastric tube and thereafter orally' Treatment compliance: not reported Sample size calculation: not reported Funding: not reported Declarations/ conflicts of interest: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quate: "A simple randomisation was used with no restriction", "The generator of allocation was separated to enrolled patients" Comments: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quate: "The generator of allocation was separated to enrolled patients" Comments: probably done |