Abstract

Background

Panic disorder is characterised by repeated, unexpected panic attacks, which represent a discrete period of fear or anxiety that has a rapid onset, reaches a peak within 10 minutes, and in which at least four of 13 characteristic symptoms are experienced, including racing heart, chest pain, sweating, shaking, dizziness, flushing, stomach churning, faintness and breathlessness. It is common in the general population with a lifetime prevalence of 1% to 4%. The treatment of panic disorder includes psychological and pharmacological interventions. Amongst pharmacological agents, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the British Association for Psychopharmacology consider antidepressants, mainly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), as the first‐line treatment for panic disorder, due to their more favourable adverse effect profile over monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Several classes of antidepressants have been studied and compared, but it is still unclear which antidepressants have a more or less favourable profile in terms of effectiveness and acceptability in the treatment of this condition.

Objectives

To assess the effects of antidepressants for panic disorder in adults, specifically:

1. to determine the efficacy of antidepressants in alleviating symptoms of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, in comparison to placebo;

2. to review the acceptability of antidepressants in panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, in comparison with placebo; and

3. to investigate the adverse effects of antidepressants in panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, including the general prevalence of adverse effects, compared to placebo.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders' (CCMD) Specialised Register, and CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO up to May 2017. We handsearched reference lists of relevant papers and previous systematic reviews.

Selection criteria

All double‐blind, randomised, controlled trials (RCTs) allocating adults with panic disorder to antidepressants or placebo.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently checked eligibility and extracted data using a standard form. We entered data into Review Manager 5 using a double‐check procedure. Information extracted included study characteristics, participant characteristics, intervention details and settings. Primary outcomes included failure to respond, measured by a range of response scales, and treatment acceptability, measured by total number of dropouts for any reason. Secondary outcomes included failure to remit, panic symptom scales, frequency of panic attacks, agoraphobia, general anxiety, depression, social functioning, quality of life and patient satisfaction, measured by various scales as defined in individual studies. We used GRADE to assess the quality of the evidence for each outcome

Main results

Forty‐one unique RCTs including 9377 participants overall, of whom we included 8252 in the 49 placebo‐controlled arms of interest (antidepressant as monotherapy and placebo alone) in this review. The majority of studies were of moderate to low quality due to inconsistency, imprecision and unclear risk of selection and performance bias.

We found low‐quality evidence that revealed a benefit for antidepressants as a group in comparison with placebo in terms of efficacy measured as failure to respond (risk ratio (RR) 0.72, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66 to 0.79; participants = 6500; studies = 30). The magnitude of effect corresponds to a number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) of 7 (95% CI 6 to 9): that means seven people would need to be treated with antidepressants in order for one to benefit. We observed the same finding when classes of antidepressants were compared with placebo.

Moderate‐quality evidence suggested a benefit for antidepressants compared to placebo when looking at number of dropouts due to any cause (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.97; participants = 7850; studies = 30). The magnitude of effect corresponds to a NNTB of 27 (95% CI 17 to 105); treating 27 people will result in one person fewer dropping out. Considering antidepressant classes, TCAs showed a benefit over placebo, while for SSRIs and serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRIs) we observed no difference.

When looking at dropouts due to adverse effects, which can be considered as a measure of tolerability, we found moderate‐quality evidence showing that antidepressants as a whole are less well tolerated than placebo. In particular, TCAs and SSRIs produced more dropouts due to adverse effects in comparison with placebo, while the confidence interval for SNRI, noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (NRI) and other antidepressants were wide and included the possibility of no difference.

Authors' conclusions

The identified studies comprehensively address the objectives of the present review.

Based on these results, antidepressants may be more effective than placebo in treating panic disorder. Efficacy can be quantified as a NNTB of 7, implying that seven people need to be treated with antidepressants in order for one to benefit. Antidepressants may also have benefit in comparison with placebo in terms of number of dropouts, but a less favourable profile in terms of dropout due to adverse effects. However, the tolerability profile varied between different classes of antidepressants.

The choice of whether antidepressants should be prescribed in clinical practice cannot be made on the basis of this review.

Limitations in results include funding of some studies by pharmaceutical companies, and only assessing short‐term outcomes.

Data from the present review will be included in a network meta‐analysis of psychopharmacological treatment in panic disorder, which will hopefully provide further useful information on this issue.

Plain language summary

Antidepressants for panic disorder in adults

Why is this review important?

Panic disorder is common in the general population. It is characterised by panic attacks, periods of fear or anxiety with a rapid onset in which other characteristic symptoms are experienced (involving bodily systems and fearful thoughts). The treatment of panic disorder includes psychological and pharmacological interventions, often used in combination. Among pharmacological interventions, the standard treatment suggested by guidelines is different classes of antidepressants. Evidence for their effectiveness and acceptability is unclear.

Who will be interested in this review?

People with panic disorder and general practitioners.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

How effective are antidepressants compared to a sham treatment (known as placebo) in treating panic disorder?

What is the acceptability of antidepressants compared to placebo in treating panic disorder?

How many unintended and untoward effects (adverse effects) do antidepressants have compared to placebo in people with panic disorder?

Which studies were included in the review?

We searched electronic databases to find all relevant studies. The medical studies included in the review compared treatment with antidepressants or placebo in adults with a diagnosis of panic disorder. The studies also had to be randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which means adults were allocated at random (by chance alone) to receive the treatment or placebo. We included 41 RCTs for a total of 9377 people in the review.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

We found evidence showing that antidepressants are better than placebo in terms of effectiveness and number of people leaving the study early. However, our findings also showed that antidepressants are less well tolerated than placebo, producing more dropouts due to adverse effects. Results are limited in the following ways: some studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies, and only short‐term outcomes were assessed. We found almost no data on other clinically relevant outcomes, such as functioning and quality of life. The quality of the available evidence ranged from very low to high.

What should happen next?

Studies with outcomes assessed at longer‐term follow‐up visits should be carried out to establish whether the effect is transient or maintained. Trials should better report any harms experienced by participants during the trial. In addition, a further analysis with an approach called 'network meta‐analysis' will include all psychopharmacological treatments available for panic disorder, and will likely shed further light on this compelling issue, also being able to provide more information with regard to comparative efficacy of different available interventions.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Panic disorder is characterised by repeated, unexpected panic attacks, which are discrete periods of fear or anxiety that have a rapid onset, reach a peak within 10 minutes and in which at least four of 13 characteristic symptoms are experienced. Many of these symptoms involve bodily systems, such as racing heart, chest pain, sweating, shaking, dizziness, flushing, stomach churning, faintness and breathlessness. Further recognised panic attack symptoms involve fearful cognitions, such as the fear of collapse, going mad or dying, and derealisation (APA 1994).

Panic disorder first entered diagnostic classification systems in 1980 with the publication of DSM‐III, following observations that people with panic attacks responded to treatment with the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) imipramine (Klein 1964). To diagnose panic disorder, further conditions must be met relating to the frequency of attacks, the need for some to come on ‘out of the blue’ rather than in a predictable, externally‐triggered situation, and exclusions where attacks are attributable solely to medical causes or panic‐inducing substances, notably caffeine. DSM‐IV requires additionally that at least one attack has been followed by either a) persistent concern about having additional attacks, b) worry about the implications of the attack or its consequences or c) a significant change in behaviour related to the attacks (APA 1994).

Panic disorder is common in the general population with a lifetime prevalence of 1% to 4% (Bijl 1998; Eaton 1994). In primary care settings, panic syndromes have been reported to have a prevalence of around 10% (King 2008). Its aetiology is not fully understood and is probably heterogeneous. Biological theories incorporate the faulty triggering of an inbuilt anxiety response, possibly a suffocation alarm. Evidence for this comes from biological challenge tests (lactate and carbon dioxide are used to trigger panic in those with the disorder) and from animal experiments and neuroimaging studies in humans that show activation of fear circuits, such as that involving the periaqueductal grey matter (Gorman 2000).

Agoraphobia is anxiety about being in places or situations from which escape might be difficult or embarrassing, or in which help may not be available in the event of having a panic attack (APA 1994). Agoraphobia can occur with panic disorder (APA 1994). About 25% of people suffering from panic disorder also have agoraphobia (Kessler 2006). The presence of agoraphobia is associated with increased severity and worse outcome (Kessler 2006). There are several risk factors that predict the development of agoraphobia in people suffering from panic disorder: female gender, more severe dizziness during panic attacks, cognitive factors, dependent personality traits and social anxiety disorder (Starcevic 2009).

Panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, is highly comorbid with other psychiatric disorders, such as drug dependence, major depression, bipolar I disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, and generalised anxiety disorder (Grant 2006). It is estimated that generalised anxiety disorder co‐occurs in 68% of people with panic disorder, whilst major depression has a prevalence of 24% to 88% among people with panic disorder (Starcevic 2009).

Description of the intervention

The treatment of panic disorder includes psychological and pharmacological interventions, often used in combination (Furukawa 2007). Historically, pharmacological interventions for panic disorder have been based on the use of mono‐amino oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (Bruce 2003). However, MAOIs and TCAs are burdened by severe adverse effects, such as dietary restrictions (to avoid hypertensive crisis) for MAOIs, and anticholinergic, arrhythmogenic and overall poor tolerability for TCAs (Wade 1999). Benzodiazepines (BDZs), particularly high‐potency ones, have been used as a safer alternative in panic disorder (Stein 2010), although the long‐term outcome may be less good (NICE 2011). Recent guidelines (APA guideline: APA 2009; BAP guideline: BAP 2005; NICE Guideline: NICE 2011) consider antidepressants, mainly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), as the first‐line treatment for panic disorder, due to their more favourable adverse effect profile over MAOIs and TCAs. A meta‐analysis comparing SSRIs and TCAs in panic disorder showed that SSRIs are as effective as TCAs, and are better tolerated (Bakker 2002), although other studies showed a possible overestimation of the efficacy of SSRIs over older antidepressants in panic disorder (Anderson 2000; Otto 2001). It appears that TCAs can still have a role in the treatment of panic disorder.

How the intervention might work

The main classes with evidence of efficacy in panic disorder are antidepressant drugs that augment the function of the monoamines serotonin or noradrenaline, or both. Considering the serotonergic antidepressants (SSRIs such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline and citalopram), these drugs promote the transmission of the neurotransmitter serotonin across brain synapses; most notably in the dorsal raphe nucleus (Briley 1993). They prevent reuptake of serotonin into nerve terminals by inhibiting serotonin transporters, thus allowing more to be available for neurotransmission. In panic disorder, imaging studies have revealed reduced expression of the 5H1A receptor (Nash 2008), which has an inhibitory function, so the increased serotonin throughput may in part serve to overcome this deficit of inhibition. Noradrenergic antidepressants can similarly increase transmission of the catecholamine noradrenaline. Some antidepressants such as the serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) drugs (e.g. venlafaxine, duloxetine) and TCAs can enhance both serotonin and noradrenaline transmission by inhibiting both transporters.

Why it is important to do this review

Antidepressants are widely used in panic disorder. Published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown some evidence of efficacy. However, no systematic study on all antidepressants in panic disorder has been conducted recently, to our knowledge. A meta‐analysis published in 2007 focused on combined psychotherapy and antidepressants in panic disorder (Furukawa 2007), and a more recent systematic review focused on psychological treatments only (Sanchez‐Meca 2010). Furukawa 2007 concluded that either combined psychotherapy and antidepressants or psychotherapy alone may be chosen as first line treatment for panic disorder. Sanchez‐Meca 2010 reported that exposure, relaxation training and breathing retraining have the most robust evidence. A network meta‐analysis was also performed to compare different psychological therapies for panic disorder (Pompoli 2016). A meta‐analysis of Bakker and colleagues included 43 studies comparing SSRIs and TCAs (Bakker 2002). The authors concluded that SSRIs and TCAs are of equal efficacy in the treatment of panic disorder, with a better tolerability profile for SSRIs. A recent Cochrane Review comparing active treatments (antidepressants and benzodiazepines) for panic disorder included 35 RCTs and failed to detect important differences between these treatments (Bighelli 2016). Both these studies were focused on active comparisons, and inform on the comparative efficacy of antidepressants with other available compounds. Antidepressants as a group were not compared with placebo, so it was not possible to estimate the effect size of antidepressant treatment in panic disorder.

To our knowledge, the most recent meta‐analysis specifically focused on antidepressants in panic disorder was published in 2013 (Andrisano 2013). This systematic review compared newer antidepressants with placebo, and included the SSRI, SNRI and NRI. The authors included 50 studies, of which only 26 were RCTs, with no requirements on blinding. Andrisano and colleagues found sertraline, paroxetine, fluoxetine and venlafaxine to be more effective than placebo on change in panic symptoms. Venlafaxine, fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram and mirtazapine were found to have a lower number of dropouts compared to placebo. However, the authors only considered total dropouts and did not investigate dropouts due to adverse effects or the number of participants experiencing adverse effects. Due to all these limitations, results from this review should be cautiously interpreted and considered only as preliminary.

An up‐to‐date review is needed to help prescribers identify the effect size of active treatment compared to placebo in panic disorder, in order to be better guided in the choice of the pharmacological agent.

One other Cochrane Review in people with panic disorder, comparing benzodiazepines with placebo is ongoing, and will be of further help to identify effective treatments in panic disorder (Guaiana 2013a).

Based on these data, a Cochrane network meta‐analysis of psychopharmacological treatment in panic disorder is also in progress (Guaiana 2017).

Objectives

To assess the effects of antidepressants for panic disorder in adults, specifically:

to determine the efficacy of antidepressants in alleviating symptoms of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, in comparison to placebo;

to review the acceptability of antidepressants in panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, in comparison with placebo; and

to investigate the adverse effects of antidepressants in panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, including the general prevalence of adverse effects, compared to placebo.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised, double‐blind, controlled trials using a parallel‐group design that compare antidepressants with placebo as monotherapy.

We included cross‐over trials, randomised, placebo‐controlled trials with more than two arms, and cluster‐randomised, placebo‐controlled trials.

We excluded quasi‐randomised trials, such as those allocated by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

Participants aged 18 years or older with a primary diagnosis of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, diagnosed according to any of the following criteria: Feighner criteria, Research Diagnostic Criteria, DSM‐III, DSM‐III‐R, DSM‐IV or ICD‐10. In case study eligibility focused on agoraphobia, rather than panic disorder, studies were to be included if operationally diagnosed according to the above‐named criteria and when it could be safely assumed that at least 30% of the participants were suffering from panic disorder as defined by the above criteria. There is evidence that more than 95% of people with agoraphobia seen clinically also suffer from panic disorder (Goisman 1995). However, we did not find any studies with such inclusion criteria.

We excluded participants with serious comorbid physical disorders (e.g. myocardial infarction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, uncontrolled diabetes, electrolyte disturbances) as they may confound treatment effectiveness and tolerability.

We included participants with comorbid mental disorders, but we examined the effect of including these participants in sensitivity analyses.

Types of interventions

Any trial comparing antidepressants as monotherapy with placebo in the treatment of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia.

We included only acute treatment studies treating participants for less than six months. We excluded relapse prevention studies.

We included the following antidepressants.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): amitriptyline, amoxapine, clomipramine, desipramine, dosulepin/dothiepin, doxepin, imipramine, lofepramine, maprotiline, nortriptyline, protriptyline, trimipramine

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, citalopram, paroxetine, escitalopram

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs): phenelzine, isocarboxazid, tranylcypromine, moclobemide, brofaromine

Serotonin‐noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, milnacipran

Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs): mirtazapine

Noradrenergic and dopaminergic reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs): bupropion

Noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (NRIs): reboxetine

Others: agomelatine, trazodone, nefazodone, mianserin, maprotiline, non‐conventional herbal products (e.g. hypericum)

We included studies in which irregular (i.e. not daily) use of benzodiazepines took place. Excluding such studies would have been meaningless because it has been documented that a minority of people take benzodiazepines surreptitiously when they are prohibited by the protocol (Clark 1990). We excluded studies in which benzodiazepines were regularly administered at a constant dosage for a long time or as part of the study medication. We noted possible differences in co‐interventions (such as differential usage of benzodiazepines in antidepressant trials) and examined their influence in sensitivity analyses.

We did not apply any restriction on dose, frequency, intensity or duration.

We excluded studies administering psychological therapies targeted at panic disorder concurrently.

Types of outcome measures

When multiple measures were used, we gave preference to the ones in the order listed below for each outcome.

Primary outcomes

Failure to respond, that is, lacking substantial improvement from baseline as defined by the original investigators. Examples of improvement would be “very much or much improved” according to the Clinical Global Impressions Scale, more than 40% reduction in the Panic Disorder Severity Scale score (which is considered as equivalent to "very much or much improved" on the Clinical Global Impression of Improvement Scale (Furukawa 2009), and more than 50% reduction in the Fear Questionnaire Agoraphobia Subscale (which is considered as an appropriate rate of response according to Bandelow 2006). For this outcome we calculated the number of participants who failed to meet these improvement criteria.

Total number of dropouts for any reason as a proxy measure of treatment acceptability.

Secondary outcomes

Failure to remit, that is, lacking of satisfactory end state as defined by global judgment of the original investigators. Examples of satisfactory end‐state would be "panic free" and "no or minimal symptoms" according to the Clinical Global Impression Severity Scale. For this outcome, we calculated the number of participants who failed to meet these remission criteria.

Panic symptom scales and global judgment on a continuous scale. Examples include Panic Disorder Severity Scale total score (0 to 28), Clinical Global Impression Severity Scale (1 to 7), and Clinical Global Impression Change Scale (1 to 7). When multiple measures were used, we gave preference in the order above, preferring to use panic symptom scales where available. We indicated the actual measure entered into meta‐analyses at the top of the listings in the Characteristics of included studies.

Frequency of panic attacks, as recorded, for example, by a panic diary.

Agoraphobia, as measured, for example, by the Fear Questionnaire, Mobility Inventory, or behavioural avoidance test.

General anxiety, as measured, for example, by the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety, Beck Anxiety Inventory, State‐Trait Anxiety Index, Sheehan Patient‐Rated Anxiety Scale, or Anxiety Subscale of SCL‐90‐R.

Depression, as measured, for example, by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, or Depression Subscale of SCL‐90‐R.

Social functioning, as measured, for example, by the Sheehan Disability Scale, Global Assessment Scale, or Social Adjustment Scale‐Self Report.

Quality of life, as measured for example by SF‐36 or SF‐12.

Patient satisfaction with treatment

Economic costs

Number of dropouts due to adverse effects

Number of participants experiencing at least one adverse effect

Timing of outcome assessment

All outcomes are short term, which we define as acute‐phase treatment that would normally last two to six months.

When studies reported response rates at different time points within two to six months, we preferred the time point closest to 12 weeks.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders' Specialised Register (CCMDCTR)

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders (CCMD) maintains two clinical trials registers at their editorial base in York, UK: a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCMDCTR‐References Register contains over 31,500 reports of RCTs in depression, anxiety and neurosis. Approximately 65% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCMDCTR‐Studies Register and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual, using a controlled vocabulary; please contact the CCMD Information Specialist for further details. Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group's registers are collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of MEDLINE (1950 to date), Embase (1974 to date) and PsycINFO (1967 to date); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (in the Cochrane Library) and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trials registers via the World Health Organization's trials portal (the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)), pharmaceutical companies, the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Details of CCMDs' generic search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website.

We searched the CCMD registers using the following terms:

CCMDCTR‐Studies

Diagnosis = "panic disorder" and Intervention = placebo* We screened records for placebo‐controlled antidepressant trials.

CCMDCTR‐References

We searched the References Register using the free‐text term 'panic*' to identify additional untagged references. We screened abstracts for antidepressant trials and retrieved full‐text articles, where necessary, to check for placebo controls.

2. National and international trials registers

We also conducted complementary searches on the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Searching other resources

Review authors checked the reference lists of all included studies, non‐Cochrane systematic reviews and major textbooks of affective disorders (written in English), for published reports and citations of unpublished research. We also conducted a citation search via the Web of Science (included studies only) to identify additional works. We contacted experts in the field.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MC and AC) independently selected trials for inclusion in this systematic review.

MC and AC inspected the search retrieval by reading the titles and abstracts to see if they met the inclusion criteria. We resolved possible doubts by consultation with the review co‐authors. We obtained each potentially‐relevant study located in the search as a full‐text article; the review authors independently assessed them for inclusion and, in the case of discordance, sought resolution by discussion between the two. We calculated the discordance in the selection of studies using Cohen's Kappa (k) (Cohen 1960), a more robust measure than a simple per cent agreement calculation, since it takes into account the agreement between review authors that occurs by chance. When it was not possible to evaluate the study because of language problems or missing information, we classified the study as 'awaiting assessment' until we could obtain a translation or further information.The reasons for the exclusion of potentially‐relevant trials are reported in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

We recorded all decisions made during the selection process, along with numbers of studies and references, and we presented them in a PRISMA flow diagram at the end of the review (Figure 1; Moher 2009).

1.

Study flow diagram

Data extraction and management

Two review authors used a data extraction form to independently extract the data from included studies concerning participant characteristics (age, sex, severity of panic disorder, study setting), intervention details (dosage, duration of study, sponsorship), study characteristics (blinding, allocation, etc) and outcome measures of interest. We piloted the data extraction sheet on a sample of 10% of the included studies. Again, we resolved any disagreement by consensus or by involving a third member of the review team. If necessary, we contacted authors of studies to obtain clarification.

Main comparisons

Antidepressants as a whole versus placebo

TCAs versus placebo

SSRIs versus placebo

MAOIs versus placebo

SNRIs versus placebo

NaSSAs versus placebo

NDRIs versus placebo

NRIs versus placebo

Other antidepressants versus placebo

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias in included studies using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). This tool encourages consideration of how the sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, the integrity of blinding at outcome assessment, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other biases. We also considered sponsorship bias.

We assessed and categorised the risk of bias in each domain and overall as either:

low risk of bias, plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results;

high risk of bias, plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results;

unclear risk of bias, plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results.

If the assessors disagreed, we made the final rating with the involvement of another member of the review group. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. We also reported non‐concurrence in quality assessment.

Measures of treatment effect

The main outcome result was reduction of severity of panic and agoraphobia symptoms. Improvement was usually presented as a change in a panic disorder scale(s) (mean and standard deviation) or as a dichotomous outcome (responder or non‐responder, remitted or not‐remitted), or both.

Binary or dichotomous data

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the random‐effects model risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that a random‐effects model has a good generalisability and that RR is more intuitive than odds ratio (Furukawa 2002; Boissel 1999). Furthermore, odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This may lead to an overestimation of the impression of the effect (Deeks 2011). For all primary outcomes, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome or harmful outcome (NNTB or NNTH) and its 95% CI using Visual Rx (www.nntonline.net/), while taking account of the event rate in the control group.

Continuous data

Summary statistics

We used standardised mean difference (SMD) as originally planned in the protocol, when studies used an idiosyncratic scale that is seldom or never used elsewhere (e.g. Phobia Scale for Agoraphobia). However, when all the included studies used the same standard scales such as Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, we used mean differences (MDs).

Endpoint versus change data

Trials usually report results either using endpoint means and standard deviation of scales or using change in mean values from baseline of assessment rating scales. We prefer to use scale endpoint data, which typically cannot have negative values and are easier to interpret from a clinical point of view. If endpoint data were unavailable, we used the change data in separate analyses. Where we used MD, we pooled results based on change data and endpoint data in the same analysis.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials are trials in which all participants receive both the control and intervention treatment but in a different order. The major problem is a carryover effect from the first phase to the second phase of the study, especially if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As this is the case with panic disorder, randomised cross‐over studies were eligible, but we planned to use only data up to the point of first cross over. However, there were no cross‐over trials included in our review.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, especially two appropriate dose groups of the same drug, we pooled the different dose arms and treated them as one group; we included 10 trials of this kind. If the trial involved one placebo arm and two or more arms of different antidepressants, we compared each arm with placebo separately. In this case, a unit‐of‐analysis error can occur, because of the unaddressed differences between the estimated intervention effects from multiple comparisons (Deeks 2011), resulting in double counting. In order to avoid that, we included each pair‐wise comparison separately, according to the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, section 16.5.4 (Higgins 2011b). If the variable was continuous, only the total number of participants was divided up, leaving means and standard deviations unchanged. There were seven studies to which this analysis was applicable.

Cluster‐randomised trials

In cluster‐randomised trials groups of individuals rather than individuals are randomised to different interventions. If we had identified cluster placebo‐controlled randomised trials, we planned to use the generic inverse variance technique, providing such trials had been appropriately analysed, while taking into account intraclass correlation coefficients to adjust for cluster effects. If study authors had not adjusted for the effects of clustering, we planned to do this by obtaining an intracluster correlation coefficient and then following the guidance given in chapter 16.3.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). However, there were no cluster‐randomised trials included in our review.

Dealing with missing data

We tried to contact the study authors for all relevant missing data.

Dichotomous outcomes

We calculated response or remission on treatment using an intention‐to‐treat analysis (ITT). We followed the principle 'once randomised always analysed'. Where participants left the study before the intended endpoint, we assumed that they would have experienced the negative outcome. We planned to test the validity of the above assumption by sensitivity analysis, applying worst and best case scenarios. However, this was not possible, as explained in Effects of interventions section. When dichotomous outcomes were not reported but the baseline mean and standard deviation on a panic disorder scale were reported, we calculated the number of responding or remitted participants according to a validated imputation method (Furukawa 2005). We checked the validity of the above approach by sensitivity analysis excluding studies with imputed data. If necessary, we contacted authors of studies to obtain data or clarification, or both.

Continuous outcomes

Concerning continuous data, the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions recommends avoiding imputation of continuous data and suggests using the data as presented by the original authors (Higgins 2011b). Where ITT data were available we used them in preference to 'per‐protocol analysis'. If necessary, we contacted authors of studies to obtain data or clarification, or both.

Skewed or qualitative data

We planned to present skewed and qualitative data descriptively.

We considered several strategies for skewed data. If papers reported a mean and standard deviation and there was also an absolute minimum possible value for the outcome, we divided the mean by the standard deviation. If the value obtained was less than 2 then we concluded that some skewness was indicated. If the value obtained was less than 1 (i.e. the standard deviation was bigger than the mean) skewness was almost certain. If papers did not report the skewness and simply reported means, standard deviations and sample sizes, we used these numbers. Because these data may not have been properly analysed and can be misleading, we conducted analysis with and without these studies. If the data had been log‐transformed for analysis, and the geometric means were reported, skewness would be reduced. This is the recommended method of analysis of skewed data (Deeks 2011). If papers used non‐parametric tests and described averages using medians, they could not be formally pooled in the analysis. We followed the recommendation made in the Cochrane Handbook and the results of these studies have been reported in a table in our review, along with all other papers. This means that the data are not lost from the review and that we can consider the results when drawing conclusions, even if they cannot be formally pooled in the analyses.

Missing statistics

When only P or standard error (SE) values were reported, we calculated standard deviations (SDs) (Altman 1996). In the absence of supplementary data after we had requested them from the study authors, we calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method (Furukawa 2006).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Following the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, we quantified heterogeneity using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions recommends overlapping intervals for I2 interpretation (section 9.5.2, Deeks 2011), as follows:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; and

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

We also used the Chi2 test and its P value to determine the direction and magnitude of the treatment effects. In a meta‐analysis of few trials Chi2 will be underpowered to detect heterogeneity, if it exists. We used P = 0.10 as a threshold of statistical significance.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These are described in chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2011). A funnel plot is usually used to investigate publication bias. However, it has a limited role when there are only few studies of similar size. Secondly, asymmetry of a funnel plot does not always reflect publication bias. Visual inspection of funnel plots has been used to assess publication bias as well as the statistical test for funnel plot asymmetry proposed by Egger or Rücker (Egger 1997; Rücker 2008; Sterne 2011). However we did not use funnel plots for outcomes if there were 10 or fewer studies, or if all studies were of similar size.

Data synthesis

We used a random‐effects model to calculate the treatment effects. We preferred the random‐effects model as it takes into account differences between studies even when there is no evidence of statistical heterogeneity. It gives a more conservative estimate than the fixed‐effect model. We note that the random‐effects model gives added weight to small studies, which can either increase or decrease the effect size. We applied a fixed‐effect model, on primary outcomes only, to see whether it markedly changed the effect size.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses are often exploratory in nature and should be interpreted cautiously because they often involve multiple analyses and can lead to false positive results. While keeping in mind the above reservations, we planned to perform the following subgroup analyses:

for classes of antidepressants, such as TCAs, SSRIs, and others;

for participants with agoraphobia and for participants without agoraphobia, because the same treatment may have differential effectiveness with regard to panic and agoraphobia;

acute‐phase treatment studies that last for less than four months versus acute‐phase treatment studies that last for four months or more.

However, we were unable to conduct the first two of these subgroup analyses since we did not find relevant studies (see Effects of interventions).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct the following sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes only in order to examine if the results changed and check for the robustness of the observed findings:

excluding trials with high risk of bias (i.e. trials with inadequate allocation concealment and blinding; with incomplete data reporting, or with high probability of selective reporting, or both);

excluding trials with dropout rates greater than 20%;

excluding studies funded by the pharmaceutical company marketing each antidepressant. This sensitivity analysis is particularly important in view of the repeated findings that funding strongly affects outcomes of research studies and because industry sponsorship and authorship of clinical trial reports have increased over the last 20 years (Als‐Nielsen 2003; Bhandari 2004; Buchkowsky 2004; Lexchin 2003);

excluding studies whose protocols do not explicitly prohibit concomitant use of BDZ. According to Clark 1990, 10% to 20% of those assigned to placebo or imipramine arms in a RCT took explicitly‐prohibited anxiolytic medication;

excluding studies whose participants clearly had significant psychiatric co‐morbidities, including primary or secondary depressive disorders;

applying best and worst case scenarios to studies where participants left the study before the endpoint;

excluding studies where number of responding participants is calculated according to an imputation method.

It was not possible to perform sensitivity analysis 6, as explained in Effects of interventions.

Our routine application of random‐effects and fixed‐effect models as well as our secondary outcomes of remission rates and continuous severity measures might be considered additional forms of sensitivity analyses.

'Summary of findings' table

We presented our results using 'Summary of findings' tables, in which we assessed the quality of the evidence applying the GRADE approach (GRADE Working Group 2004; Schünemann 2011). 'Summary of findings' tables include the primary outcomes, failure to respond and total number of dropouts, and secondary outcomes, failure to remit, panic symptom scales as further measures of efficacy and number of dropouts due to adverse effects as a measure of tolerability.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The number of references identified by the searches (last update May 2017) was 1746. We excluded 1615 references after assessment of titles and abstracts. We retrieved 131 full‐text reports for full inspection, describing 76 unique RCTs. Of these, we excluded 23 studies, and placed 11 studies in the awaiting assessment group; one study is ongoing. Finally, we included 41 RCTs (49 placebo controlled study arms) including 9377 participants, 8252 for the arms of interest (described in 95 reports) in the review. In case of missing information, we contacted authors of the included studies for additional information, and two of them responded (Drs. Lavori, CNCPS 1992, and Stahl, Stahl 2003‐cit, Stahl 2003‐esc). See Figure 1 for a PRISMA flow diagram depicting the study selection process (Moher 2009).

Included studies

Forty‐one RCTs (43 'studies') were included in this review, with characteristics as follows (see also Characteristics of included studies).

Design

All 41 included studies were parallel‐group, individually randomised controlled studies. Two studies were three‐armed and included placebo comparison of two antidepressants belonging to the same class. Since this might be confusing when reading the forest plots, these studies have been labelled according to the drug used (Gentil 1993‐clo; Gentil 1993‐imi; Stahl 2003‐cit; Stahl 2003‐esc), and appear therefore twice. When reporting the number of studies that contributed for each analysis, studies contributing with more comparisons are counted only once.

Sample sizes

The sample sizes ranged between six (Mavissakalian 1989) and 445 (Sheehan 2005) participants in each arm. Twenty‐six studies included overall sample sizes over 100: Asnis 2001, (n = 188), Ballenger 1998 (n = 278), Barlow 2000 (n = 312), Bradwejn 2005 (n = 361), Caillard 1999 (n = 180), Cassano 1999 (n = 274), CNCPS 1992 (n = 1168), GSK 1994 (n= 226), Koszycki 2011 (n = 251), Lecrubier 1997 (n = 368), Liebowitz 2009 (n = 343), Londborg 1998 (n = 177), Michelson 2001 (n = 180), Nair 1996 (n = 148), Pollack 1998 (n = 176), Pollack 2007‐a (n = 653), Pollack 2007‐b (n = 663), Schweizer 1993 (n = 106), Sharp 1996 (n = 190), Sheehan 2005 (n = 889), Stahl 2003‐cit (also referred to as Stahl 2003‐esc) (n = 380), Tsutsui 1997 (n = 169), Tsutsui 2000a (n = 171), Tsutsui 2000b (n = 120), Wade 1997 (n = 475).

Setting

A total of 27 trials enrolled only outpatients, one trial enrolled only inpatients, both inpatients and outpatients were enrolled in three trials and a total of two trials enrolled patients in primary care centres or in general practice. For the remaining eight trials, the setting was unclear. Thirteen trials were conducted in the USA, three each in the Netherlands, Japan and European sites, two in Canada, and one each in Brazil, France, Germany and the UK; 10 trials were multinational, and three did not provide information about the country.

Participants

The proportion of women ranged from 47% to 92%. Mean age ranged from 30.63 to 61.24 years.

Interventions

Twenty‐six studies included two arms of interest for this review, while the remaining studies had three or more arms. Seventeen studies compared TCAs to placebo; 22, SSRIs; four, SNRIs; one, MAOIs; one, NRIs; and two included a comparison between other antidepressants (nefazodone and ritanserin) and placebo. No trials looked at NaSSAs or NDRIs.

Duration of the intervention ranged from 8 to 28 weeks.

Outcomes

Thirty studies reported data on response rates, measured with improvement on Clinical Global Impression of Improvement scale (CGI‐I), Clinical Global Impression Severity of Illness Score (CGI‐S) or Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS). The number of dropouts for any reason was reported in 38 studies. Twenty‐three studies reported on remission rates, remission being defined in the studies with the criterion "patients free from full panic attacks". Twenty‐four studies reported data on panic symptoms (using Panic and Anticipatory Anxiety Scale (PAAS), PDSS, CGI‐S), 24 on frequency of panic attacks, 19 on agoraphobia (using Fear Questionnaire (FQ) and Marks‐Sheehan Phobia Scale), 28 on general anxiety (using Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAS) and Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAMA)), 18 on depression (using Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)). Sixteen studies reported data on social functioning (using Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS)), 5 on quality of life. Three studies reported data on patient satisfaction; none of the studies reported on economic costs. Thirty‐one studies had data on dropouts due to adverse effects, and 15 on number of patients experiencing at least one adverse effect.

Excluded studies

See: Characteristics of excluded studies.

Twenty‐three studies, initially selected did not meet our inclusion criteria and we excluded them for the following reasons: six had an ineligible study design; two trials included participants younger than 18 years; four included participants who were not primarily diagnosed with panic disorder; two studies included participants with anxiety disorders in general, but the randomisation was not stratified by the presence of panic disorder; and nine studies had an ineligible comparison group.

Ongoing studies

See: Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Our search identified one ongoing study (Kruimel 2015), comparing escitalopram versus placebo.

Studies awaiting classification

See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

We classified 10 studies as awaiting classification.

Risk of bias in included studies

For details of the 'Risk of bias' judgements for each study, see Characteristics of included studies. Graphical representations of the overall risk of bias in included studies are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Random sequence generation

The majority of studies (39 RCTs) did not report the methods of random sequence generation; only two studies specified this information, and we classified them as low risk (Koszycki 2011; Pollack 1998).

Allocation concealment

Only four studies reported details on allocation concealment and we classified them as low risk (Koszycki 2011; Tsutsui 1997; Tsutsui 2000a; Tsutsui 2000b).

Blinding

All 41 included RCTs were reported to be double‐blind, mostly without providing any further detail. Sixteen RCTs reported details on strategies to ensure blinding of participants and key study personnel, and we classified them as low risk for performance bias. We classified 11 studies as low risk for detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We rated 10 trials as adequate in terms of addressing incomplete outcome data, while we classified 20 studies as unclear risk and 11 as high risk.

Selective reporting

The study protocol was not available for almost all studies so it is difficult to make a judgment on the possibility of outcome reporting bias. However, in 21 studies results were consistent with the outcomes pre‐specified in the methods section and clearly reported in the results, so we evaluated them as low risk. Using the same criterion, we judged 11 studies to be at high risk.

Other potential sources of bias

Twenty‐seven of the included studies were funded by the pharmaceutical industry, and they did not report details on the role of the funder in planning, conducting and writing the study; for this reason we rated them as high risk. Ten studies did not specify the source of funding. Four studies were funded by public grants or explicitly declared not to have received funding from pharmaceutical companies, so we classified them as low risk (Broocks 1998; Gentil 1993‐clo; Mavissakalian 1989; Van Vliet 1993).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antidepressants compared to placebo for panic disorder.

| Antidepressants compared to placebo for panic disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with panic disorder Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: antidepressants Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes (2‐6 months post‐treatment) | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Antidepressants | |||||

| Failure to respond | 556 per 1000 | 400 per 1000 (367 to 439) | RR 0.72 (0.66 to 0.79) | 6500 (30 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | A RR of 0.72 means that the treatment with antidepressants decreases the risk of nonresponse to treatment by 28% compared to placebo. |

| Total number of dropouts | 319 per 1000 | 281 per 1000 (258 to 309) | RR 0.88 (0.81 to 0.97) | 7850 (38 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | A RR of 0.88 means that the treatment with antidepressants decreases the risk of leaving the study early by 12% compared to placebo. |

| Failure to remit | 595 per 1000 | 494 per 1000 (464 to 524) | RR 0.83 (0.78 to 0.88) | 6164 (24 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | A RR of 0.83 means that the treatment with antidepressants decreases the risk of non reaching remission by 17% compared to placebo. |

|

Panic symptoms ‐ endpoint score (various scales) |

The mean endpoint score for panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.44 standard deviations lower (0.58 lower to 0.30 lower) | 3699 (15 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | We calculated SMD of endpoint scores. The results show a benefit for antidepressants compared to placebo. The size of effect can be considered between small and moderate (Cohen 1988). | ||

|

Panic symptoms ‐ mean change (various scales) |

The mean change in panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.53 standard deviations lower (0.72 lower to 0.33 lower) | 2010 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,4 | We calculated SMD of mean change scores. The results show a benefit for antidepressants compared to placebo. The size of effect can be considered moderate (Cohen 1988). | ||

| Number of dropouts due to adverse effects | 57 per 1000 | 85 per 1000 (72 to 102) | RR 1.49 (1.25 to 1.78) | 7688 (33 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | A RR of 1.49 means that the treatment with antidepressants increases the risk of leaving the study because of adverse effects by 49%, compared to placebo. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Downgraded one point due to high dropout rates (> 30%) in many studies. Moreover, random sequence generation and allocation concealment were unclear in most of the studies. 2Downgraded one point due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 67%). 3Downgraded one point due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 68%). 4Downgraded one point due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 73%).

Summary of findings 2. Tricyclic antidepressants compared to placebo for panic disorder.

| Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) compared to placebo for panic disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with panic disorder Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: TCA Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes (2‐6 months post‐treatment) | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | TCA | |||||

| Failure to respond | 659 per 1000 | 481 per 1000 (415 to 566) | RR 0.73 (0.63 to 0.86) | 829 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | A RR of 0.73 means that treatment with TCA decreases the risk of nonresponse to treatment by 27% compared to placebo. |

| Total number of dropouts | 408 per 1000 | 302 per 1000 (257 to 351) | RR 0.74 (0.63 to 0.86) | 1906 (17 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | A RR of 0.74 means that treatment with TCA decreases the risk of leaving the study early by 26% compared to placebo. |

| Failure to remit | 581 per 1000 | 476 per 1000 (401 to 575) | RR 0.82 (0.69 to 0.99) | 1294 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | A RR of 0.82 means that treatment with TCA decreases the risk of not reaching remission by 18% compared to placebo. |

|

Panic symptoms ‐ endpoint score (various scales) |

The mean endpoint score for panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.50 standard deviations lower (0.62 lower to 0.39 lower) | 1247 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | We calculated SMD of endpoint scores. The results show a benefit for TCA compared to placebo. The size of effect can be considered moderate (Cohen 1988). | ||

|

Panic symptoms ‐ mean change (various scales) |

The mean change in panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 2.09 standard deviations lower (4.07 lower to 0.12 lower) | 70 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3,4 | We calculated SMD of mean change scores. The results show a benefit for TCA compared to placebo. The size of effect can be considered large (Cohen 1988). | ||

| Number of dropouts due to adverse effects | 44 per 1000 | 87 per 1000 (58 to 128) | RR 1.97 (1.33 to 2.91) | 1641 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | A RR of 1.97 means that treatment with TCA increases the risk of leaving the study because of adverse effects by 97% compared to placebo. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Downgraded one point due to high dropout rates (> 30%) in many studies. Moreover, random sequence generation and allocation concealment were unclear in most of the studies. 2Downgraded one point due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 63%). 3Downgraded two points due to considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 89%). 4Downgraded one point due to imprecision: number of participants included in the analysis is very low.

Summary of findings 3. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors compared to placebo for panic disorder.

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) compared to placebo for panic disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with panic disorder Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: SSRIs Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes (2‐6 months post‐treatment) | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | SSRI | |||||

| Failure to respond | 545 per 1000 | 408 per 1000 (365 to 457) | RR 0.75 (0.67 to 0.84) | 4000 (21 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | A RR of 0.75 means that treatment with SSRI decreases the risk of to treatment by 25% compared to placebo. |

| Total number of dropouts | 292 per 1000 | 290 per 1000 (263 to 319) | RR 0.99 (0.90 to 1.09) | 4302 (23 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | A RR close to 1 means that the risk of leaving the study early is no different with treatment with SSRI or with placebo. |

| Failure to remit | 557 per 1000 | 451 per 1000 (418 to 490) | RR 0.81 (0.75 to 0.88) | 3339 (16 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ moderate1 | A RR of 0.81 means that treatment with SSRI decreases the risk of not reaching remission by 19% compared to placebo. |

|

Panic symptoms ‐ endpoint score (various scales) |

The mean endpoint score for panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.28 standard deviations lower (0.39 lower to 0.17 lower) | 1625 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | We calculated SMD of endpoint scores. The results show a benefit for SSRI compared to placebo. The size of effect can be considered between small and moderate (Cohen 1988). | ||

|

Panic symptoms ‐ mean change (various scales) |

The mean change in panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.43 standard deviations lower (0.58 lower to 0.29 lower) | 1255 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | We calculated SMD of mean change scores. The results show a benefit for SSRI compared to placebo. The size of effect can be considered between small and moderate (Cohen 1988). | ||

| Number of dropouts due to adverse effects | 67 per 1000 | 97 per 1000 (77 to 121) | RR 1.45 (1.16 to 1.81) | 4131 (22 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | A RR of 1.45 means that treatment with SSRI increases the risk of leaving the study because of adverse effects by 45% compared to placebo. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Downgraded one point due to high dropout rates (> 30%) in many studies. Moreover, random sequence generation and allocation concealment were unclear in most of the studies. 2Downgraded one point due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 64%).

Summary of findings 4. Serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors compared to placebo for panic disorder.

| Serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) compared to placebo for panic disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with panic disorder Settings: outpatients Intervention: SNRIs Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes (2‐6 months post‐treatment) | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | SNRI | |||||

| Failure to respond | 495 per 1000 | 302 per 1000 (203 to 451) | RR 0.61 (0.41 to 0.91) | 1531 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | A RR of 0.61 means that treatment with SNRI decreases the risk of nonresponse to treatment by 39% compared to placebo. |

| Total number of dropouts | 254 per 1000 | 237 per 1000 (176 to 321) | RR 0.93 (0.69 to 1.26) | 1531 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | A RR close to 1 means that the risk of leaving the study early is no different with treatment with SNRI or with placebo. |

| Failure to remit | 667 per 1000 | 561 per 1000 (500 to 634) | RR 0.84 (0.75 to 0.95) | 1531 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | A RR of 0.84 means that treatment with SNRI decreases the risk of not reaching remission by 16% compared to placebo. |

|

Panic symptoms ‐ endpoint score (various scales) |

The mean endpoint score for panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.28 standard deviations lower (0.44 lower to 0.12 lower) | 723 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | We calculated SMD of endpoint scores. The results show a benefit for SNRI compared to placebo. The size of effect can be considered between small and moderate (Cohen 1988). | ||

|

Panic symptoms ‐ mean change (various scales) |

The mean change in panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.41 standard deviations lower (0.60 lower to 0.23 lower) | 685 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | We calculated SMD of mean change scores. The results show a benefit for SNRI compared to placebo. The size of effect can be considered between small and moderate (Cohen 1988). | ||

| Number of dropouts due to adverse effects | 43 per 1000 | 64 per 1000 (40 to 103) | RR 1.49 (0.92 to 2.40) | 1531 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | A RR of 1.49 means that treatment with SNRI increases the risk of leaving the study because of adverse effects by 49% compared to placebo. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; SNRI: serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded two points due to considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 89%). 2 Downgraded one point due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 60%). 3 Downgraded one point due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 57%). 4 Downgraded one point due to serious imprecision: 95% CI ranges from no difference to appreciable benefit with placebo.

All comparisons and outcomes with data are reported below. Time point for outcome assessment was short term (acute‐phase treatment, two to six months), with preference given for the time point closest to 12 weeks.

Comparison 1. Antidepressants versus placebo

Forty studies including 8220 participants provided data for at least one outcome for this comparison. See also: Table 1.

Primary outcomes

1.1 Failure to respond

We found low‐quality evidence showing a benefit for antidepressants over placebo in terms of response rates (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.79; participants = 6500; studies = 30).

The effect estimate is very precise, with a small confidence interval, even if the degree of heterogeneity between studies was substantial (I2 = 67%) (Analysis 1.1). The magnitude of effect corresponds to a NNTB of 7 (95% CI 6 to 9): that means 7 people would need to be treated with antidepressants in order for one to benefit. Visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested that publication bias might have occurred, although Egger's test was not statistically significant (P = 0.058).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antidepressants versus placebo, Outcome 1 Failure to respond.

All classes of antidepressants showed a benefit over placebo: TCAs (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.86; participants = 829; studies = 9; I2 = 37% , moderate‐quality evidence; NNTB of 6, 95% CI 5 to 11), SSRIs (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.84; participants = 4000; studies = 21; I2 = 64%, low‐quality evidence; NNTB of 8, 95% CI 6 to 12), MAOIs (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.88; participants = 29; studies = 1; NNTB of 3, 95% CI 2 to 25), SNRIs (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.91; participants = 1531; studies = 4; I2 = 89%, low‐quality evidence; NNTB of 6, 95% CI 4 to 23), NRIs (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.97; participants = 82; studies = 1; NNTB of 5, 95% CI 3 to 43), with the exception of other antidepressants (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.15; participants = 29; studies = 1). No data were available for NaSSAs or NDRIs.

Test for subgroup difference did not reveal heterogeneity between classes of antidepressants (P = 0.24), I² = 25.8%).

Results of this outcome are shown in Figure 4.

4.

Forest plot of comparison 1. Antidepressants versus placebo, outcome 1.1, failure to respond

1.2 Total number of dropouts

In comparison with placebo, fewer participants receiving antidepressants dropped out due to any cause (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.97; participants = 7850; studies = 38; I2 = 30%, moderate‐quality evidence) (Analysis 1.2). The magnitude of effect corresponds to a NNTB of 27 (95% CI 17 to 105); treating 27 people will result in one person fewer dropping out. Visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested that publication bias might have occurred, although Egger's test was not statistically significant (0.639).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antidepressants versus placebo, Outcome 2 Total number of dropouts.

When looking at classes of antidepressants, only TCAs (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.86; participants = 1906; studies = 17; I2 = 11%, moderate‐quality evidence) (NNTH of 10, 95% CI 7 to 18) and NRIs (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.90; participants = 82; studies = 1) (NNTH of 4, 95% CI 3 to 19) had a benefit over placebo, while moderate‐quality evidence showed no difference between SSRIs and placebo (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.09; participants = 4302; studies = 23; I2 = 0%) and between SNRIs and placebo (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.26; participants = 1531; studies = 4; I2 = 60%, moderate‐quality evidence).

One study on other antidepressants found no dropouts both for ritanserin and placebo arms, so it was not possible to calculate a RR.

Test for subgroup differences revealed a substantial heterogeneity between classes of antidepressants (P = 0.002, I2 = 79.7%).

No data were available for MAOIs, NaSSAs and NDRIs for this outcome.

Results of this outcome are shown in Figure 5.

5.

Forest plot of comparison 1. Antidepressants versus placebo, outcome 1.2, total number of dropouts

Secondary outcomes

1.3 Failure to remit

We found moderate‐quality evidence showing a benefit for antidepressants compared to placebo in terms of remission rates (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.88; participants = 6164; studies = 24); heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 40%) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antidepressants versus placebo, Outcome 3 Failure to remit.

All classes of antidepressants showed a benefit over placebo on this outcome: TCAs (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.99; participants = 1294; studies = 8; I2 = 63%, low‐quality evidence), SSRIs (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.88; participants = 3339; studies = 16; I2 = 30%, moderate‐quality evidence) and SNRIs (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.95; participants = 1531; studies = 4; I2 = 57%, moderate‐quality evidence), without any subgroup differences (P = 0.89, I2 = 0%).

No data were available for MAOIs, NaSSAs, NDRIs, NRIs and other antidepressants for this outcome.

1.4 Panic symptoms ‐ endpoint score

We found low‐quality evidence showing a benefit for antidepressants in comparison with placebo in decreasing panic symptoms, measured as a continuous outcome with endpoint scores (SMD ‐0.44, 95% CI ‐0.58 to ‐0.30; participants = 3699; studies = 15), with substantial heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 68%) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antidepressants versus placebo, Outcome 4 Panic symptoms ‐ endpoint score.

All classes of antidepressants showed a benefit over placebo: TCAs (SMD ‐0.50, 95% CI ‐0.62 to ‐0.39; participants = 1247; studies = 7; I2 = 0%, moderate‐quality evidence), SSRIs (SMD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐0.39 to ‐0.17; participants = 1625; studies = 6; I2 = 4%, moderate‐quality evidence), MAOIs (SMD ‐3.68, 95% CI ‐4.93 to ‐2.43; participants = 29; studies = 1), SNRIs (SMD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐0.44 to ‐0.12; participants = 723; studies = 2; I2 = 0%, high‐quality evidence) and NRIs (SMD ‐1.02, 95% CI ‐1.50 to ‐0.53; participants = 75; studies = 1).

The difference between subgroups was considerable (P < 0.001, I2 = 90.6%)

No data were available for NaSSAs, NDRIs and other antidepressants for this outcome.

1.5 Panic symptoms ‐ mean change

Low‐quality evidence showed a benefit for antidepressants in comparison with placebo in decreasing panic symptoms, measured as a continuous outcome with mean change from baseline scores (SMD ‐0.53, 95% CI ‐0.72 to ‐0.33; participants = 2010; studies = 10), with substantial heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 73%) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antidepressants versus placebo, Outcome 5 Panic symptoms ‐ mean change.

When looking at classes of antidepressants, all classes showed a benefit over placebo: TCAs (SMD ‐2.09, 95% CI ‐4.07 to ‐0.12; participants = 70; studies = 2; I2 = 89%, very low‐quality evidence), SSRIs (SMD ‐0.43, 95% CI ‐0.58 to ‐0.29; participants = 1255; studies = 7; I2 = 36%, moderate‐quality evidence), SNRIs (SMD ‐0.41, 95% CI ‐0.60 to ‐0.23; participants = 685; studies = 2; I2 = 17%, high‐quality evidence).

The subgroups did not differ significantly (P = 0.25, I² = 27.3%)

No data were available for MAOIs, NaSSAs, NDRIs, NRIs and other antidepressants for this outcome.

1.6 Frequency of panic attacks ‐ endpoint score

Antidepressants as a whole showed a benefit over placebo in terms of frequency of panic attacks measured at endpoint (SMD ‐0.43, 95% CI ‐0.66 to ‐0.20; participants = 1671; studies = 17); heterogeneity was substantial (I2 = 78%) (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antidepressants versus placebo, Outcome 6 Frequency of panic attacks ‐ endpoint score.

All classes of antidepressants compared to placebo decreased the frequency of panic attacks: TCAs (SMD ‐0.83, 95% CI ‐1.38 to ‐0.28; participants = 470; studies = 8; I2 = 84%), SSRIs (SMD ‐0.17, 95% CI ‐0.32 to ‐0.02; participants = 1126; studies = 8; I2 = 25%) and NRIs (SMD ‐0.91, 95% CI ‐1.39 to ‐0.44; participants = 75; studies = 1).

The subgroup differed significantly (P < 0.002, I2 = 84.3%)

No data were available for MAOIs, SNRIs, NaSSAs, NDRIs and other antidepressants for this outcome.

1.7 Frequency of panic attacks ‐ mean change

In terms of frequency of panic attacks measured as change from baseline, antidepressants as a whole showed a benefit over placebo (SMD ‐0.43, 95% CI ‐0.72 to ‐0.14; participants = 2579; studies = 8), with a considerable heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 91%) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antidepressants versus placebo, Outcome 7 Frequency of panic attacks ‐ mean change.

When looking at classes of antidepressants, we found evidence showing no difference between TCAs and placebo (SMD ‐0.08, 95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.21; participants = 204; studies = 2; I2 = 0%), a benefit for SSRIs over placebo (SMD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.30 to ‐0.03; participants = 949; studies = 5; I2 = 0%) and a benefit for SNRIs over placebo (SMD ‐0.87, 95% CI ‐1.35 to ‐0.39; participants = 1426; studies = 4; I2 = 94%).

Subgroup difference was substantial (I2 = 76%).

No data were available for MAOIs, NaSSAs, NDRIs, NRIs and other antidepressants for this outcome.

1.8 Agoraphobia ‐ endpoint score

We found evidence showing a benefit for antidepressants over placebo in terms of agoraphobia measured as a continuous outcome with endpoint scores (SMD ‐0.69, 95% CI ‐0.99 to ‐0.39; participants = 2987; studies = 12); heterogeneity was considerable (I2 = 91%) (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antidepressants versus placebo, Outcome 8 Agoraphobia ‐ endpoint score.

Six studies about TCAs suggested a benefit in the direction of antidepressants over placebo (SMD ‐0.59, 95% CI ‐1.31 to 0.13; participants = 1122; I2 = 94%); SSRIs showed a benefit over placebo (SMD ‐0.50, 95% CI ‐0.71 to ‐0.29; participants = 1732; studies = 6; I2 = 67%), as well as MAOIs (SMD ‐5.38, 95% CI ‐7.03 to ‐3.72; participants = 29; studies = 1) and NRIs (SMD ‐1.56, 95% CI ‐2.09 to ‐1.04; participants = 75; studies = 1). One study found no difference between other antidepressants and placebo (SMD 0.23, 95% CI ‐0.56 to 1.02; participants = 29; studies = 1).

The was a considerable difference between classes of antidepressants (P < 0.001, I2 = 92%).

No data were available for SNRIs, NaSSAs and NDRIs for this outcome.

1.9 Agoraphobia ‐ mean change

We found evidence showing a benefit for antidepressants over placebo in terms of agoraphobia measured as a continuous outcome with mean change from baseline scores (SMD ‐0.68, 95% CI ‐1.19 to ‐0.17; participants = 1792; studies = 7), with a considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 96%) (Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

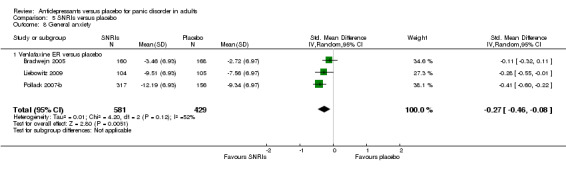

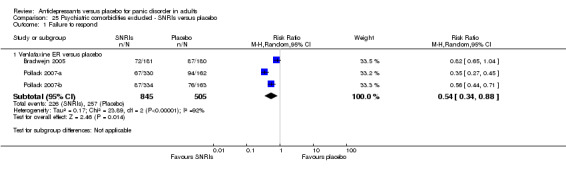

Comparison 1 Antidepressants versus placebo, Outcome 9 Agoraphobia ‐ mean change.