Abstract

Background

Major depression and other depressive conditions are common in people with cancer. These conditions are not easily detectable in clinical practice, due to the overlap between medical and psychiatric symptoms, as described by diagnostic manuals such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Moreover, it is particularly challenging to distinguish between pathological and normal reactions to such a severe illness. Depressive symptoms, even in subthreshold manifestations, have been shown to have a negative impact in terms of quality of life, compliance with anti‐cancer treatment, suicide risk and likely even the mortality rate for the cancer itself. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the efficacy, tolerability and acceptability of antidepressants in this population are few and often report conflicting results.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy, tolerability and acceptability of antidepressants for treating depressive symptoms in adults (aged 18 years or older) with cancer (any site and stage).

Search methods

We searched the following electronic bibliographic databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2017, Issue 6), MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to June week 4 2017), Embase Ovid (1980 to 2017 week 27) and PsycINFO Ovid (1987 to July week 4 2017). We additionally handsearched the trial databases of the most relevant national, international and pharmaceutical company trial registers and drug‐approving agencies for published, unpublished and ongoing controlled trials.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs comparing antidepressants versus placebo, or antidepressants versus other antidepressants, in adults (aged 18 years or above) with any primary diagnosis of cancer and depression (including major depressive disorder, adjustment disorder, dysthymic disorder or depressive symptoms in the absence of a formal diagnosis).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently checked eligibility and extracted data using a form specifically designed for the aims of this review. The two authors compared the data extracted and then entered data into Review Manager 5 using a double‐entry procedure. Information extracted included study and participant characteristics, intervention details, outcome measures for each time point of interest, cost analysis and sponsorship by a drug company. We used the standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

We retrieved a total of 10 studies (885 participants), seven of which contributed to the meta‐analysis for the primary outcome. Four of these compared antidepressants and placebo, two compared two antidepressants, and one three‐armed study compared two antidepressants and placebo. In this update we included one additional unpublished study. These new data contributed to the secondary analysis, while the results of the primary analysis remained unchanged.

For acute‐phase treatment response (6 to 12 weeks), we found no difference between antidepressants as a class and placebo on symptoms of depression measured both as a continuous outcome (standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) −1.01 to 0.11, five RCTs, 266 participants; very low certainty evidence) and as a proportion of people who had depression at the end of the study (risk ratio (RR) 0.82, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.08, five RCTs, 417 participants; very low certainty evidence). No trials reported data on follow‐up response (more than 12 weeks). In head‐to‐head comparisons we only retrieved data for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus tricyclic antidepressants, showing no difference between these two classes (SMD −0.08, 95% CI −0.34 to 0.18, three RCTs, 237 participants; very low certainty evidence). No clear evidence of a beneficial effect of antidepressants versus either placebo or other antidepressants emerged from our analyses of the secondary efficacy outcomes (dichotomous outcome, response at 6 to 12 weeks, very low certainty evidence). In terms of dropouts due to any cause, we found no difference between antidepressants as a class compared with placebo (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.38, seven RCTs, 479 participants; very low certainty evidence), and between SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.30, three RCTs, 237 participants). We downgraded the certainty (quality) of the evidence because the included studies were at an unclear or high risk of bias due to poor reporting, imprecision arising from small sample sizes and wide confidence intervals, and inconsistency due to statistical or clinical heterogeneity.

Authors' conclusions

Despite the impact of depression on people with cancer, the available studies were very few and of low quality. This review found very low certainty evidence for the effects of these drugs compared with placebo. On the basis of these results, clear implications for practice cannot be deduced. The use of antidepressants in people with cancer should be considered on an individual basis and, considering the lack of head‐to‐head data, the choice of which agent to prescribe may be based on the data on antidepressant efficacy in the general population of individuals with major depression, also taking into account that data on medically ill patients suggest a positive safety profile for the SSRIs. To better inform clinical practice, there is an urgent need for large, simple, randomised, pragmatic trials comparing commonly used antidepressants versus placebo in people with cancer who have depressive symptoms, with or without a formal diagnosis of a depressive disorder.

Plain language summary

Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in people with cancer

The issue Depressive states are frequent among people suffering from cancer. Often depressive symptoms are a normal reaction or a direct effect of such a severe and life‐threatening illness. It is therefore not easy to establish when depressive symptoms become a proper disorder and need to be treated with drugs. Current scientific literature reveals that depressive symptoms, even when mild, can have a relevant impact on the course of cancer, reducing people's overall quality of life and affecting their compliance with anti‐cancer treatment, as well as possibly increasing the likelihood of death.

The aim of the review It is important to assess the possible beneficial role of antidepressants in adults (aged 18 years or above) with cancer. The aim of this review is to assess the efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants for treating depressive symptoms in patients with cancer at any site and stage.

What are the main findings? We systematically reviewed ten studies assessing the efficacy of antidepressants, for a total of 885 participants. The evidence is current to 3 July 2017. Due to the small number of people in the studies, and issues with how the studies reported what was done, there is uncertainty over whether antidepressants were better than placebo in terms of depressive symptoms after 6 to 12 weeks of treatment. We did not have enough evidence to determine how well antidepressants were tolerated in comparison with placebo. Our results did not show whether any particular antidepressant was better than any other in terms of both beneficial and harmful effects. To better inform clinical practice, we need large studies which randomly assign people to different treatments. Currently, we cannot draw reliable conclusions about the effects of antidepressants on depression in people with cancer.

Certainty of the evidence The certainty of the evidence was very low because of a lack of information about how the studies were designed, low numbers of people in the analysis of results, and differences between the characteristics of the studies and their results.

What are the conclusions? Despite the impact of depression on people with cancer, the available studies were very few and of low quality. This review found very low certainty evidence for the effects of these drugs compared with placebo.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The prevalence of major depression among people with cancer has been estimated to be around 15% in oncological and haematological settings, with similar rates in palliative care settings. Adding other depressive diagnoses, including dysthymia and minor depression, prevalence rates rise up to 20% in oncological and haematological settings, and up to 25% in palliative care settings (Mitchell 2011). However, a precise estimation of the prevalence of depression in cancer patients is difficult due to the influence of many variables, including site and stage of cancer, type of anti‐cancer treatment, and diagnostic tools employed (Caruso 2017).

Formulating a diagnosis of depression in patients affected by serious medical conditions is particularly challenging, as several symptoms of the medical condition may overlap with those described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (APA 1994) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (WHO 1992) for depression, such as fatigue, weight loss and sleep disturbances (Thompson 2017). Furthermore, besides physical symptoms, cancer progression is associated with functional, social and relational impairment. Even recurrent thoughts of death might be a normal reaction to a limited life expectancy or to severe pain syndromes (Breitbart 2000). It has recently been reported that atypical depressive symptoms, such as anxiety, despair, fatigue, post‐traumatic stress symptoms, body image distortions, inner restlessness and social withdrawal might be more frequent in this population, and need to be taken into account when depressive symptoms are assessed (Brenne 2013; Diaz‐Frutos 2016; Ebede 2017; Yi 2017).

Cancer may increase patients' susceptibility to depression in several ways. First, a reaction to a severe diagnosis and the forthcoming deterioration of health status may constitute a risk factor for depression; second, treatment with immune response modifiers and chemotherapy regimens, and experiencing of metabolic and endocrine alterations, chronic pain and extensive surgical interventions, may represent additional contributing factors (Irwin 2013; Onitilo 2006; Sotelo 2014).

In people with cancer, depression and other psychiatric comorbidities are responsible for worsened quality of life (Arrieta 2013), lower compliance with anti‐cancer treatment (Colleoni 2000), prolonged hospitalisation (Prieto 2002), higher suicide risk (Shim 2012), and greater psychological burden on the family (Kim 2010). Furthermore, depression is likely to be an independent risk factor for cancer mortality (Lloyd‐Williams 2009; Pinquart 2010), with estimates as high as a 26% greater mortality rate among patients with depressive symptoms and a 39% higher mortality rate among those with a diagnosis of major depression (Satin 2009). The effects of depression on mortality may differ by cancer site, being higher in people with lung, gastrointestinal (in particular, pancreatic), and brain cancer, and lower in those with genitourinary and skin cancer (Onitilo 2006; Hartung 2017). However, data are sparse and conflicting on this compelling issue (Pinquart 2010). As a consequence, individuals with cancer and major depression or depressive symptoms may have radically different features compared with individuals without cancer in terms of underlying risk factors, natural history, outcome and antidepressant treatment response (Brenne 2013; Irwin 2013).

Description of the intervention

Antidepressants are the most common psychotropic drugs prescribed in people with depression. Amongst antidepressants, many different agents are available, including tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin‐noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and other newer agents, such as agomelatine, mirtazapine, reboxetine and bupropion. It has been repeatedly shown that SSRIs are not more effective than TCAs (Anderson 2000; Mottram 2009), but are better tolerated and safer in overdose than TCAs (Anderson 2000; Barbui 2001; Henry 1995).

In a narrative review covering pharmacological, psychological and psychosocial interventions, Li 2012 reported controversial findings on the effectiveness of antidepressants for the prevention and treatment of depressive symptoms in people with cancer. There were few available trials and the findings were not consistent. It has been suggested that in people with cancer, Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) level I evidence (at least two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with adequate sample sizes, preferably placebo‐controlled, or meta‐analysis with narrow confidence intervals (CIs), or both) (Kennedy 2016) is available only for mianserin for the treatment of depressive symptoms and for paroxetine for the prevention of new episodes (Li 2012). A meta‐analysis of the efficacy of psychological and pharmacological interventions by Hart 2012 identified only four eligible trials assessing the efficacy of antidepressant drugs. A more recent meta‐analysis, carried out by Laoutidis 2013, found six placebo‐controlled trials and three head‐to‐head trials concerning the treatment of depression in people with cancer at any stage and site. Among these trials, substantial heterogeneity was found (i.e. relevant variability of participants, interventions and outcome due to different clinical, methodological and statistical approaches) (Higgins 2011). The meta‐analysis showed an improvement in depressive symptoms in patients treated with antidepressants, with an overall risk ratio of 1.56 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07 to 2.28). No difference in dropouts was found between groups. Subgroup analysis failed to identify differences between TCAs and SSRIs, and found that subsyndromal depressive symptoms (i.e. symptoms which do not reach the status of a formal depressive syndrome as it is described by diagnostic manuals, such as DSM or ICD) may similarly improve with antidepressant treatment (Laoutidis 2013). Similar findings have been previously shown in physically ill people in a meta‐analytic study (Rayner 2010).

A meta‐analysis by Walker 2014, which included trials carried out in people with a formal diagnosis of depression, found limited evidence in favour of the use of antidepressant drugs. However, only two placebo‐controlled trials were included, and in both of them the antidepressant was mianserin, an agent rarely used in current clinical practice. More recently, Riblet and colleagues (Riblet 2014), who systematically reviewed the evidence comparing antidepressants and placebo in individuals with any type and stage of cancer and comorbid depression of any severity, retrieved 10 trials suitable for a meta‐analysis on the efficacy of antidepressants. They concluded that fluoxetine, paroxetine and mianserin may improve cancer‐related depression. However, one quasi‐randomised trial was included and two trials included patients who were not depressed at baseline.

Rayner 2011a conducted a meta‐analytic study on the efficacy of antidepressants in people receiving palliative care (including cancer and several other life‐threatening illnesses) and suffering from depression (including major depressive disorder, adjustment disorder and dysthymic disorder based on standardised criteria, and/or according to a score above a certain cut‐off on validated tools). This review detected a beneficial effect associated with antidepressant treatment and suggested that people in palliative care with milder depressive disorders, as well as major depression, may be responsive to antidepressant treatment. These findings were incorporated into European guidelines on the management of depression in palliative cancer care (Rayner 2011b), in which use of an antidepressant is recommended, not only in major depression but also in mild depression, if symptoms persist after first‐line treatments have failed (including assessment of the quality of relationships with significant others, psychosocial support, guided self‐help programmes and brief psychological interventions). However, there is still a lack of evidence as to whether antidepressants are all similarly effective in this population.

How the intervention might work

Antidepressants are a heterogeneous class of drugs, in which a common mechanism of action is not traceable. Their therapeutic action may be related to their ability to affect serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine neurotransmission systems, according to the broadly studied theory about monoamine dysregulation as the key neurophysiological event underlying mood disorders. However, in recent years, alternative mechanisms have been shown, making progressively clearer the complexity of interactions between several systems on which the action of these drugs rely. For instance, current research on new antidepressant drugs focuses on affecting mechanisms related to glutamate (Lapidus 2013) and melatonin transmission (Hickie 2011), neural proliferation and plasticity in limbic areas (Pilar‐Cuéllar 2013), and endocrine system activities (hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis in particular) (Sarubin 2014), as well as antioxidant, anti‐inflammatory and immunologic pathways (Lopresti 2012).

The extent to which each of these components can contribute to the dysregulation of the brain's homeostatic system could vary extensively among different individuals and also with several biological, environmental and psychological factors (Shelton 2007). For this reason, even if the efficacy of antidepressants has been proven for some kinds of depressive conditions, we cannot assume these data to be reliable in the same way for people with cancer, for whom several further factors may be involved in the pathogenesis (including psychological, immunologic and metabolic factors, as well as pain and highly distressing treatments). Some authors have suggested a possible beneficial effect of antidepressants in cancer biology (Gil‐Ad 2008; Ahmadian 2017; Chan 2017; Zingone 2017). However, these findings are largely explorative and need to be further investigated; and it is not clear whether the effect of antidepressants may differ according to the specific cancer type or site, or both. Few systematic reviews have explored this issue, retrieving only small numbers of studies from which to draw conclusions (Carvalho 2014; Walker 2014).

In most cases antidepressant dose should be gradually titrated and it can be some weeks before the treatment takes effect. Antidepressants may require adjustment over time to ensure an appropriate dose is given. Moreover, it has been highlighted that compliance represents a relevant factor for an antidepressant's efficacy (Vergouwen 2003).

Why it is important to do this review

Providing better interventions for people with cancer and depressive symptoms is an important goal. Single pharmacological, psychological and physical interventions are not an exhaustive response for such a complex and multi‐faceted condition, which is likely to benefit from integrated, multi‐component approaches (Anwar 2017; Sharpe 2014). With this in mind, a Cochrane systematic review on the efficacy, tolerability and acceptability of antidepressants is needed in addition to existing Cochrane systematic reviews on psychotherapy (Akechi 2008; McCaughan 2017), psychosocial (Galway 2012; Semple 2013), physical (Furmaniak 2016; Shin 2016) and complementary interventions (Bradt 2015; Cramer 2017).

A systematic review by Laoutidis 2013 included participants with depressive disorder and subsyndromal depressive symptoms, identified nine randomised trials for inclusion and showed antidepressants to be superior to placebo. In their review, however, only trials in English were included, unpublished trials were not sought, and trials with depression as a secondary outcome were excluded. Further, the authors performed a meta‐analysis on dichotomous data only. Another review (Ostuzzi 2015) included people with a diagnosis of depressive disorder, subsyndromal depressive symptoms, and also people without an assessment of depressive symptoms at baseline, provided that they received antidepressant treatments for emotionally distressing cancer‐related manifestations (such as fatigue, insomnia, asthenia or cancer pain), The meta‐analysis showed a beneficial effect of antidepressants over placebo in treating depressive symptoms as a whole, and the effect remained statistically significant when considering separately participants with a formal diagnosis of major depression or depressive symptoms at baseline, and participants for whom antidepressant use was related to other distressing cancer‐related symptoms. In addition, antidepressants showed to be effective in improving quality of life.

Considering these limitations and that available systematic reviews provide contrasting findings (Hart 2012; Laoutidis 2013; Li 2012; Rodin 2007), there is still uncertainty as to the true efficacy of antidepressants (Rooney 2010; Rooney 2013; Walker 2014). Moreover, most of the previous reviews focused on elevated depressive symptoms (Hart 2012), or major depression (Iovieno 2011; Ng 2011; Walker 2014), while current findings suggest that depressive symptoms, even in subsyndromal manifestations, could represent an independent risk factor for the burden of disease (Arrieta 2013; Brenne 2013; Pinquart 2010; Satin 2009). Although the efficacy of antidepressants in minor depression, dysthymia and adjustment disorder is still not clear (Barbui 2011; Casey 2011; Silva de Lima 1999; Silva de Lima 2005), different authors suggest that antidepressants are effective in people suffering from severe medical illness (including cancer), even for subthreshold depressive symptoms (Laoutidis 2013; Rayner 2010; Rayner 2011a).

Based on this evidence we carried out a systematic review Ostuzzi 2015 (full review). In this previous version of the review we found no significant differences between antidepressants (as a class) and placebo in treating depressive symptoms, and this evidence was of very low certainty. Similarly, we found no significant differences between SSRIs and TCAs; this evidence was also of very low certainty. In this update, we have sought to include new relevant studies, or to retrieve new data from studies which were previously ongoing or awaiting classification.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy, tolerability and acceptability of antidepressants for treating depressive symptoms in adults (aged 18 years or older) with cancer (any site and stage).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We only included randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We excluded trials using quasi‐random methods. We included trials published in any language.

Types of participants

We included adults (aged 18 years or older) with any primary diagnosis of cancer (confirmed with appropriate clinical and instrumental assessment) and major depressive disorder, adjustment disorder, dysthymic disorder or depressive symptoms in the absence of a formal diagnosis of major depression. We included participants receiving antidepressants for other indications (e.g. fatigue, neuropathic pain, hot flushes, etc.) only if the criterion of being affected by one of the above‐mentioned depressive conditions was met at the time of enrolment.

For trials including a diagnosis of depression, we included any standardised criteria. Most recent trials use DSM‐IV (APA 1994), or ICD‐10 (WHO 1992) criteria. Older trials use ICD‐9 (WHO 1978), DSM‐III (APA 1980) or DSM‐ III‐R (APA 1987), or other diagnostic systems. For trials including depressive symptoms in the absence of a formal diagnosis of major depression, we only included those employing standardised criteria to measure depressive symptoms and with evidence of adequate validity and reliability. Most recent trials use the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) (Hamilton 1960), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1961), the Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979), or the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond 1983).

Types of interventions

We included the following antidepressants, reported in the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical/Defined Daily Dose (ATC/DDD) Index (updated to December 2017) from the World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology website (www.whocc.no):

non‐selective monoamine reuptake inhibitors, such as amitriptyline, desipramine, imipramine, imipramine oxide, nortriptyline, clomipramine, dosulepine, doxepin, opipramol, trimipramine, lofepramine, dibenzepin, protriptyline, iprindole, melitracen, butriptyline, amoxapine, dimetacrine, amineptine, maprotiline, quinupramine;

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram, escitalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, alaproclate, etoperidone, zimelidine;

monoamine oxidase A inhibitors, such as moclobemide, toloxatone;

non‐selective monoamine oxidase inhibitors, such as isocarboxazid, nialamide, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, iproniazide, iproclozide;

any newer antidepressant and any other non‐conventional antidepressive agents, such as mianserin, trazodone, nefazodone, mirtazapine, bupropion, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, reboxetine, agomelatine, milnacipran, oxitriptan, tryptophan, nomifensine, minaprine, bifemelane, viloxazine, oxaflozane, medifoxamine, tianeptine, pivagabine, gepirone, vilazodone, Hyperici herba.

The comparison group was placebo or any other antidepressants (head‐to‐head comparisons), or both.

We excluded trials in which antidepressants were compared with another type of psychopharmacological agent, i.e. psycho‐stimulants, anxiolytics, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics or mood stabilisers.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Efficacy as a continuous outcome

We extracted and analysed group mean scores at different time points and, if these were not available, group mean change scores, on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD), Montgomery and Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) or Clinical Global Impression Rating scale (CGI), or on any other depression rating scale with evidence of adequate validity and reliability, as follows:

early response: between one and four weeks, giving preference to the time point closest to two weeks;

acute phase treatment response: between 6 and 12 weeks, giving preference to the time point given in the original trial as the study endpoint;

follow‐up response: after 12 weeks, giving preference to the time point closest to 24 weeks.

The acute phase treatment response (between 6 and 12 weeks) was our primary outcome of interest. If the acute phase treatment response was reported, we then reported early response and follow‐up response as secondary outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

Efficacy as a dichotomous outcome

Treatment responders during the 'acute phase' (between 6 and 12 weeks): proportion of participants showing a reduction of at least 50% on the HRSD or MADRS or any other depression scale (e.g. the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) or the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D)), or who were 'much or very much improved' (score 1 or 2) on the Clinical Global Impression‐Improvement (CGI‐I) scale, or the proportion of participants who improved using any other pre‐specified criterion.

Social adjustment

Mean scores on social adjustment rating scales, e.g. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), as defined by each of the trials, during the 'acute phase' (between 6 and 12 weeks).

Health‐related quality of life

Mean scores on quality of life (QoL) rating scales during the 'acute phase' (between 6 and 12 weeks). We gave preference to illness‐specific QoL measures, such as the European Organisation for Research and Treatment into Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire‐30 (EORTC QLQ‐30) (Aaronson 1993), the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) scale (Cella 1993), and the Short Form (36) Health Survey (SF‐36) (Ware 1980; Ware 1992). When such tools were not employed, we used a general health‐related QoL measure with evidence of adequate validity and reliability, as defined by each of the trial

Dropouts:

number of participants who dropped out during the trial as a proportion of the total number randomised (total dropout rate, also referred as "acceptability");

number of participants who dropped out due to inefficacy during the trial as a proportion of the total number randomised (dropout rates due to inefficacy);

number of participants who dropped out due to adverse effects during the trial as a proportion of the total number randomised (dropout rates due to adverse effects, also referred as "tolerability").

We extracted dropouts at trial endpoint only.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic bibliographic databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, 2017, Issue 6) in the Cochrane Library (searched 3 July 2017) (Appendix 1), MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to June week 4 2017) (Appendix 2), Embase Ovid (1980 to 2017 week 217) (Appendix 3) and PsycINFO Ovid (1987 to June 2017 week 4) (Appendix 4).

Searching other resources

Handsearches

We handsearched the trial databases of the following drug‐approving agencies for published, unpublished and ongoing controlled trials: the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the USA (http://www.fda.gov), the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the United Kingdom (http://www.mhra.gov.uk/), the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in the European Union (http://www.ema.europa.eu), the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) in Japan (http://www.pmda.go.jp/english/) and the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) in Australia (http://www.tga.gov.au/).

We additionally searched the following trial registers: clinicaltrials.gov in the USA (http://clinicaltrials.gov/), ISRCTN and National Research Register in the United Kingdom (www.isrctn.com/), UMIN‐CTR in Japan (www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/), the ANZ‐CTR in Australia and New Zealand (www.anzctr.org.au/), the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) and the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (IFPMA) Clinical Trials Portal (www.ifpma.org/tag/clinical‐trials/).

We also handsearched appropriate journals and conference proceedings relating to depression treatment in people with cancer. We also handsearched the web sites of the most relevant pharmaceutical companies producing antidepressants, such as GlaxoSmithKline (www.gsk‐clinicalstudyregister.com/), Sanofi (www.sanofi.com/en/science‐and‐innovation/clinical‐trials‐and‐results/), Janssen (www.janssen.com/clinical‐trials), Lundbeck (www.lundbeck.com/trials), Pfizer (www.pfizer.co.uk/clinical‐trials), Abbott (www.abbott.com/policies/clinical‐trials.html), Lilly (www.lillytrials.com/), and Merck (www.merck.com/research/discovery‐and‐development/clinical‐development/home.html) for published, unpublished and ongoing controlled trials.

We also searched reference lists of included trials and other relevant studies.

Personal communication

We searched the websites of pharmaceutical companies (list reported in the methods) and contacted the authors of the unpublished studies. Only one author provided data from one unpublished study.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to a reference management database (Endnote) and removed duplicates. Two review authors (GO and FM) examined the remaining references independently. We excluded those trials that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria, and we obtained copies of the full text of potentially relevant references. Two review authors (GO and FM) independently assessed the eligibility of retrieved trials. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two review authors and, if necessary, with a third review author (CB). We documented reasons for exclusion. We collated multiple reports of the same trials to ensure that no data were included in the meta‐analysis more than once.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (GO and FM), working independently and in duplicate, extracted data from the included trials using a data collection sheet (see Appendix 5), which was developed in accordance with recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011; chapter 7). If the trial was a three (or more)‐armed trial involving a placebo arm, we also extracted data from the placebo arm.

Data included:

first author, year and journal;

methodological features (study design, randomisation, blinding and allocation concealment, follow‐up period);

participant characteristics (gender, age, study setting, number of participants randomised to each arm, depression diagnosis, previous history of depression, cancer site and stage, cancer treatment);

intervention details (antidepressant and other interventions employed, dosage range, mean daily dosage prescribed);

outcome measures for each time point of interest. Continuous measures encompassed mean scores of rating scales, standard deviation or standard error; dichotomous measures were endpoint response rate and dropout rate, which were calculated on a strict intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis;

cost analysis (estimates of the cost of resources employed to perform the trial);

presence of sponsorship by a drug company.

Alongside the data which contributed to meta‐analysis, we collected characteristics of participants, settings, interventions and methodological approaches, in order to provide an overall view of the available evidence on this topic (see Description of studies), as well as to perform an accurate assessment of the risk of bias (see Risk of bias in included studies). These elements provided a crucial contribution to the discussion, with particular regards to the clinical applicability of the results of the study (see Overall completeness and applicability of evidence; Implications for practice).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (GO and FM) independently assessed the risk of bias of all included trials in accordance with Cochrane's tool in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), which includes the following domains: random sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (detection bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting of outcomes (reporting bias) and other biases. To determine the risk of bias of a trial, for each criterion we evaluated the presence of sufficient information and the likelihood of potential bias. We rated each criterion as 'low risk of bias', 'high risk of bias' or 'unclear risk of bias' (indicating either lack of information or uncertainty over the potential for bias). Particular attention was given to the adequacy of the random allocation concealment and blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors. If inadequate details of methodological characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted the authors in order to obtain further information. If the raters disagreed, the final rating was made by consensus with the involvement (if necessary) of a third review author (CB). We summarised results in a 'Risk of bias' graph and a 'Risk of bias' summary and discussed and interpreted the results of meta‐analysis in light of the findings and with respect to the risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Continuous data

We evaluated the efficacy of treatments as a continuous measure, namely the group mean scores on depression rating scales at the acute phase (between 6 and 12 weeks). We employed other continuous data for some secondary outcomes, namely efficacy at early response (between one and four weeks), efficacy at follow‐up response (after 12 weeks), social adjustment and health‐related quality of life.

2. Dichotomous data

We employed dichotomous data for some secondary outcomes, namely efficacy as the number of treatment responders at the acute phase (between 6 and 12 weeks), and the proportion of dropouts.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase, the participants can differ systematically from their initial state, even despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason, cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). Both effects are very likely in major depression, thus we planned to use only data from the first phase of cross‐over trials.

2. Cluster‐randomised trials

We planned to use the generic inverse variance technique to appropriately analyse cluster‐randomised trials, taking into account intra‐class correlation coefficients to adjust for cluster effects.

Dealing with missing data

At some degree of loss to follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). For any particular outcome, if more than 50% of data were unaccounted for, we did not reproduce these data or use them within analyses. If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a trial were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we planned to mark such data with (*) to indicate that such a result may be prone to bias. When dichotomous or continuous outcomes were not reported, we asked trial authors to supply the data.

We calculated dichotomous data on a strict intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis: dropouts were always included in this analysis. Where participants had been excluded from the trial before the endpoint, we assumed that they experienced a negative outcome by the end of the trial. For continuous variables, we applied a loose ITT analysis, whereby all the participants with at least one post‐baseline measurement were represented by their last observations carried forward (LOCF), with due consideration of potential biases, including number and timings of dropouts in each arm.

When relevant outcomes were not reported, we asked trial authors to supply the data. In the absence of data from authors, we only employed validated statistical methods to impute missing outcomes, with due consideration of the possible bias of these procedures, in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and with www.missingdata.org.uk. When standard deviations (SDs) were not reported, we asked authors to supply the data. When only the standard error (SE) or t‐statistics or P values were reported, we calculated SDs according to Altman 1996. In the absence of data from the authors, we substituted SDs with those reported in other trials in the review (Furukawa 2006).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We investigated heterogeneity between trials using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003; Ioannidis 2008) (we considered an I2 value equal to or more than 50% to indicate substantial heterogeneity) and by visual inspection of the forest plots.

Assessment of reporting biases

We had planned to use the tests for funnel plot asymmetry to investigate small‐study effects (Sterne 2000), if there were at least 10 trials included in the meta‐analysis, with cautious interpretation of the results by visual inspection (Higgins 2011). Since we were unable to conduct any analysis including at least 10 trials we did not use a funnel plot. When evidence of small‐study effects was identified, we aimed to investigate possible reasons for funnel plot asymmetry, including publication bias.

Data synthesis

If a sufficient number of clinically similar studies was available, we pooled their results in meta‐analyses.

For continuous data we pooled the mean differences (MDs) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) between the treatment arms at the time point of interest, if all trials measured the outcome using the same rating scale; otherwise we pooled standardised mean differences (SMDs). For dichotomous data, we pooled the risk ratio (RR) with a 95% CI. For the analysis of dichotomous data we employed the Mantel‐Haenszel methods. For statistically significant results, we calculated the number needed to treat to provide benefit (NNTB). We included trials that compared more than two intervention groups of the same drug (i.e. different dosages) in meta‐analysis by combining arms of the trials into a single group, for the intervention and for the control group respectively, as recommended in section 16.5 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If data were binary, we simply added and combined them into one group or divided the comparison arm into two (or more) as appropriate. If data were continuous, we combined the data following the formula in Chapter 7, section 7.7.3.8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We included trials that compared two or more antidepressants with placebo as independent comparisons, splitting the 'shared' group (placebo) into two or more groups with smaller sample size (Higgins 2011).

We chose a random‐effects model as heterogeneity was expected (Higgins 2011). We only considered direct comparisons for the meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We aimed to perform the following subgroup analyses for the primary outcome:

psychiatric diagnosis, separating major depressive disorder, and pooling data from studies including only participants with adjustment disorder, dysthymic disorder, depressive symptoms;

previous history of depressive conditions;

antidepressant class, in particular separating SSRIs, TCAs and other antidepressants;

cancer site, separating breast cancer and other sites;

cancer stage, separating early stages (stage 0 and I) and late stages (stage II, III and IV);

gender.

We interpreted subgroup analyses with caution, as multiple analyses can lead to false positive conclusions (Oxman 1992).

Sensitivity analysis

We aimed to perform the following sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome:

excluding trials in which the randomisation process was not clearly reported;

excluding trials with unclear concealment of random allocation;

excluding trials that did not employ adequate blinding of participants, healthcare providers and outcome assessors;

excluding trials that did not employ depressive symptoms as their primary outcome;

excluding trials with imputed data.

'Summary of findings' table

We prepared 'Summary of findings' tables, summarising the key findings of the systematic review in line with the standard methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). These findings include:

-

antidepressants compared to placebo for depressive symptoms in people with cancer:

efficacy as a continuous outcome;

efficacy as a dichotomous outcome;

dropouts.

-

antidepressants compared to other antidepressants for depressive symptoms in people with cancer:

efficacy as a continuous outcome;

efficacy as a dichotomous outcome;

dropouts.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

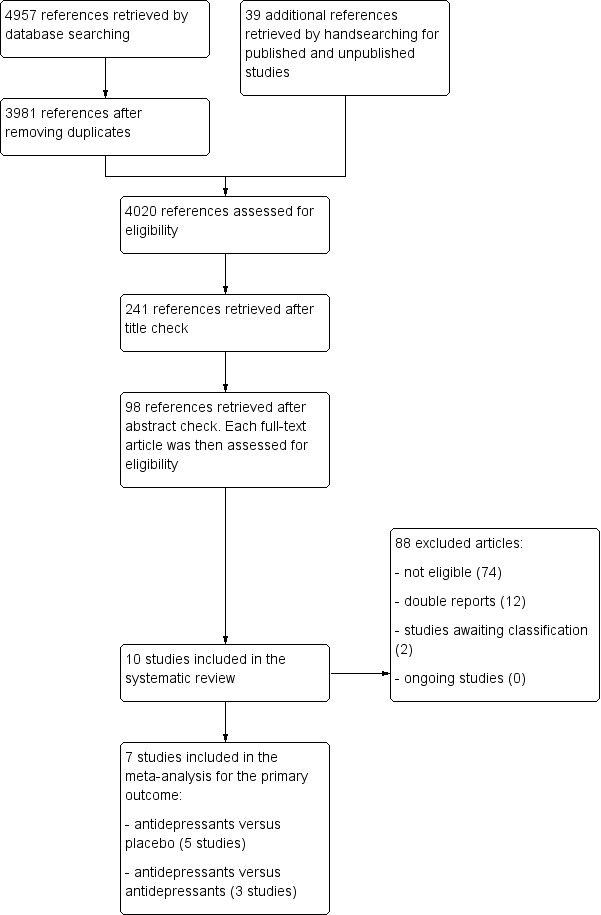

See Figure 1 for an illustration of the process of study selection. The search of the electronic databases retrieved 4957 references. After eliminating the duplicates, we identified 3981 references for screening. We added 39 further references from the handsearching of articles' references and the websites of drug‐approving agencies and pharmaceutical companies. Two review authors (GO, FM) independently checked 10% of the titles. Since the degree of agreement was 'good' according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (simple kappa statistic 0.73), one review author (GO) checked the remaining titles. From the 241 titles identified, the two review authors independently checked 50% of the abstracts. The degree of agreement was 'fair' according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (simple kappa statistic 0.41). The two review authors discussed the abstracts for which there was inconsistency between them and achieved complete agreement. One review author (GO) checked the remaining abstracts. The two review authors examined the full text of all of the 98 studies identified after the abstract check in detail. Ten studies fulfilled the criteria for eligibility and were included in the review (Costa 1985; EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR; Fisch 2003; Holland 1998; Musselman 2006; Navari 2008; NCT00387348; Pezzella 2001; Razavi 1996; Van Heeringen 1996). Only seven studies contributed to the meta‐analysis for the primary outcome (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR; Fisch 2003; Holland 1998; Musselman 2006; Pezzella 2001; Razavi 1996; Van Heeringen 1996). Two studies (Costa 1985; NCT00387348) contributed only to the meta‐analysis for secondary outcomes and Navari 2008 did not provide useful data for the meta‐analysis.

1.

Flow diagram.

Included studies

We included a total of ten studies: eight published studies (Costa 1985; Fisch 2003; Holland 1998; Musselman 2006; Navari 2008; Pezzella 2001; Razavi 1996; Van Heeringen 1996), and two unpublished studies (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR; NCT00387348). A total of 885 participants were involved in these studies. A detailed description of each study is reported in the section Characteristics of included studies.

Design and interventions

All the included studies were reported to be randomised and double‐blind. The participants were followed up for four weeks in one trial (Costa 1985), five weeks in one trial (Razavi 1996), six weeks in three trials (Holland 1998; Musselman 2006; Van Heeringen 1996), eight weeks in two trials (NCT00387348; Pezzella 2001), 12 weeks in one trial (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR), 24 weeks in one trial (Navari 2008) and for a mean of 15 weeks in one trial (range between 4 and 24 weeks) (Fisch 2003). Seven studies had two arms and explored the efficacy of an antidepressant versus placebo (Costa 1985; EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR; NCT00387348; Fisch 2003; Navari 2008; Razavi 1996; Van Heeringen 1996). In five of these studies the antidepressant was a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR; NCT00387348; Fisch 2003; Navari 2008; Razavi 1996), and in two the tetracyclic antidepressant mianserin was evaluated (Costa 1985; Van Heeringen 1996). Two studies compared two antidepressants with a two‐arm, head‐to‐head study design (paroxetine versus amitriptyline and fluoxetine versus desipramine respectively) (Holland 1998; Pezzella 2001). One study used a three‐arm design, comparing paroxetine versus desipramine versus placebo (Musselman 2006). In these three studies the head‐to‐head comparisons were between a tricyclic antidepressant and a SSRI.

Sample sizes

The mean number of participants per study was approximately 88, with a minimum sample size of 24 (NCT00387348), and a maximum of 193 (Navari 2008). Only three studies had more than 100 participants (Fisch 2003; Navari 2008; Pezzella 2001).

Setting

Four trials enrolled only outpatients (Fisch 2003; Musselman 2006; Navari 2008; Van Heeringen 1996). Inpatients and outpatients were enrolled in one trial (Costa 1985). For the remaining five trials the setting was not clearly reported (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR; NCT00387348; Holland 1998; Pezzella 2001; Razavi 1996).

Participants

Two trials excluded people aged over 65 years (Holland 1998; Van Heeringen 1996), while no trials included only elderly participants. The population of participants was heterogeneous in terms of diagnosis of depression. One trial enrolled only participants with a diagnosis of major depression based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM‐III) in association with a score greater than 16 on the 21‐item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) (Van Heeringen 1996). One trial enrolled participants with a diagnosis of major depression according to DSM‐IV, to Endicott criteria, and with a score higher than 14 on 17‐item HRSD (NCT00387348). One trial enrolled participants with major depression according to International Classification of Diseases‐ tenth revision (ICD‐10) criteria (Pezzella 2001). Three studies enrolled both people with a diagnosis of major depression and people with adjustment disorders based on DSM‐III‐R (Holland 1998), on DSM‐III‐R in association with a score greater than 14 on the first 17 items of the 21‐item HRSD (Musselman 2006), or on DSM‐III‐R in association with a score greater than 13 on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Razavi 1996). However, in the Musselman 2006 trial only people with major depression took part in the study. Three studies enrolled people with depressive symptoms, but without a formal diagnosis of depression according to a cut‐off score on standardised rating scales, respectively Two‐Question Screening Survey (TQSS) greater than 2 (Fisch 2003; Navari 2008) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) greater than 11 (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR). One study (Costa 1985) used alternative criteria for defining depression (quote: "diagnosis of depression according to the criteria proposed by Stewart [Stewart 1965] for medically ill patients, with slight additional inclusion criteria suggested by Kathol and Petty [Kathol 1981] [...]") in association with a cut‐off score on standardised rating scales, Zung Self‐Rating Depression Scale (ZSRDS) greater than 41; 17‐item HRSD greater than 16.

With regards to the cancer type and stage, three studies had mixed populations (Costa 1985; Holland 1998; Razavi 1996), but the majority of participants suffered from breast cancer. In Fisch 2003, the population was quite equally distributed between breast, thoracic, genitourinary and other types of cancer. Four studies included only women with breast cancer (Musselman 2006; Navari 2008; Pezzella 2001; Van Heeringen 1996). One study (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR) included only people suffering from head and neck cancer and another (NCT00387348) included only people suffering from lung or gastro‐intestinal cancer. In two studies the cancer stage was not clearly reported (Fisch 2003; Razavi 1996). Two studies included only people with early stages ("localized" or "early locally advanced" disease) (Navari 2008; Van Heeringen 1996), while all other studies also recruited people with late‐stage disease (Costa 1985; EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR; Holland 1998; Musselman 2006; Pezzella 2001). One study (NCT00387348) included only people with late locally advanced or metastasised disease.

Outcomes

For efficacy outcomes, most of the randomised controlled trials (RCTs) provided continuous data such as mean score or mean change on standardised rating scales, including those considered reliable for the aims of this review, such as HRSD (Costa 1985; Musselman 2006; NCT00387348; Van Heeringen 1996), Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR; Razavi 1996), or other scales (Fisch 2003; Pezzella 2001). One study (Navari 2008) provided only dichotomous data, defining "responders" those who achieved a certain improvement in the rating scale score. This study provided these data only for the six‐month assessment and thus could not be included in the meta‐analysis.

For secondary outcomes, the majority of the studies provided complete data on total dropouts, due to inefficacy and side‐effects. Three studies provided only partial data on dropouts (Fisch 2003; Navari 2008; NCT00387348). Very few studies reported data on other secondary outcomes, such as social adjustment (Pezzella 2001) and quality of life (Fisch 2003; Pezzella 2001).

We included a total of 479 people in the efficacy analysis on a continuous outcome between 6 and 12 weeks (primary outcome) and 592 on a dichotomous outcome; 175 in the social adjustments analysis; 305 in the quality of life analysis; and 716 in the analysis of dropouts.

Excluded studies

We excluded most of the retrieved references after title and abstract screening. Of the 98 studies selected for a full‐text evaluation, we excluded 88: 74 did not meet one or more inclusion criteria (mostly a wrong diagnostic status), 12 were double reports and 2 were added to Studies awaiting classification. No ongoing studies were retrieved (Figure 1).

In particular, one study did not enrol patients with cancer, while in 35 studies participants were not depressed when enrolled or the studies enrolled a population with mixed psychiatric symptoms (e.g. both anxious and depressed patients). Nine studies were not randomised and one was actually a review of other studies. For eight studies the comparison group was not reliable because no placebo or active comparator were employed. For three studies, for which only the abstract or the protocol was available, we contacted the authors who informed us that these studies had been withdrawn or changed in their design. Details are reported in Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

We found the overall methodological quality of the included studies to be unclear or low (see Figure 2; Figure 3). Only five studies had a low risk of bias for at least one item (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR; NCT00387348; Fisch 2003; Musselman 2006; Pezzella 2001).

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Almost all the studies had an 'unclear risk' for the selection bias domain — which includes random sequence generation and allocation concealment — because procedures for ensuring adequate concealment of allocation were not reported in the paper or in the protocol, and because information about the adequacy of the allocation sequence generation were not provided. Only one study (Fisch 2003) clearly described the procedures for randomisation and allocation of participants, which were properly performed.

Blinding

With the exception of NCT00387348, which had a 'low risk' of performance and detection bias, we considered all the included studies to have an 'unclear risk'. The studies were described as "double‐blind", however they did not report who was blinded among practitioners, outcome assessors and statisticians; neither did they describe procedures for ensuring the blinding of both participants and who administered the intervention.

Incomplete outcome data

The risk of attrition bias appeared to be a particularly relevant issue, with different reasons between studies. We considered six studies to have a 'high risk' because no imputation for missing data was performed, resulting in a 'per protocol analysis' or an 'as treated analysis' (even if the term 'intention‐to‐treat analysis' was often reported) (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR; Fisch 2003; Holland 1998; Navari 2008; Razavi 1996; Van Heeringen 1996). Furthermore, in three of these studies this issue was associated with a dropout rate higher than 20% in at least in one arm, which could possibly induce bias in the intervention effect estimate (Holland 1998; Razavi 1996; Van Heeringen 1996). For two studies we considered the risk of bias as 'unclear' since the intention‐to‐treat analysis was properly performed (Costa 1985; Musselman 2006), but the dropout rate was particularly high (40.5% in the placebo arm in Costa 1985; and 38% in the paroxetine arm, 36% in the desipramine arm and 45% in the placebo arm in Musselman 2006). For two studies (Pezzella 2001; NCT00387348) we considered the risk to be 'low' since the intention‐to‐treat analysis was properly performed and the dropout rate was not particularly relevant.

Selective reporting

The risk of reporting bias was particularly inconsistent between studies. For two studies the risk was 'high' as primary outcomes were not clearly prespecified and were poorly reported in the text (Holland 1998; Navari 2008). For four studies the risk was 'unclear' as primary outcomes were not clearly prespecified, but relevant outcomes of interest were properly reported in the results (Costa 1985; Pezzella 2001; Razavi 1996; Van Heeringen 1996). For the remaining studies all the prespecified primary outcomes were reported for the time points of interest (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR; NCT00387348; Fisch 2003; Musselman 2006).

Other potential sources of bias

With regards to the possible occurrence of other types of bias, we found no relevant baseline imbalance of the population composition. Furthermore, we systematically assessed the risk of sponsorship bias and in five studies this bias could not be ruled out since the possible conflicts of interest, as well as the role of funders in planning, conducting and writing the study were not discussed (Costa 1985; Fisch 2003; Musselman 2006; Navari 2008; Pezzella 2001). For these studies we considered the risk of bias to be 'unclear'. For three studies we considered the risk to be 'high', as the funder was a pharmaceutical company and its role in planning, conducting and writing the study was not discussed (Holland 1998; Razavi 1996; Van Heeringen 1996). In one study a pharmaceutical company funded the cost of drugs but did not play any relevant role in planning, conducting and writing the study (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR). One study was clearly funded by non‐profit institutes (NCT00387348).

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antidepressants compared to placebo for people with cancer and depression.

| Antidepressants compared to placebo for patients with cancer and depression | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with cancer and depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: antidepressants Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainity (quality) of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Antidepressants | |||||

| Efficacy as a continuous outcome Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | The mean efficacy as a continuous outcome (SMD) in the intervention groups was 0.45 standard deviations lower (1.01 lower to 1.11 higher) | 266 (5 studies, 6 comparisons) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 | |||

| Efficacy as a dichotomous outcome Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | 358 per 1000 | 294 per 1000 (222 to 387) | RR 0.82 (0.62 to 1.08) | 417 (5 studies, 6 comparisons) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3,4,5 | |

| Dropouts due to any cause (acceptability) Follow‐up: 4 to 12 weeks | 215 per 1000 | 187 per 1000 (105 to 328) | RR 0.85 (0.52 to 1.38) | 479 (7 studies, 7 comparisons) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3,4,6 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded as no studies described the outcome assessment as masked. This should be considered a major limitation, which is likely to result in a biased assessment of the intervention effect. 2 Downgraded due to heterogeneity ‐ I² = 77%. An I² between 50% and 75% suggests a serious risk of inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity), which may arise from relevant differences in populations, interventions and outcomes of the studies entered into the analysis. 3 Downgraded due to very low number of participants recruited (fewer than 100 individuals in both treatment arms) and 95% CI includes both no effect and appreciable benefit or appreciable harm, which suggests the risk of very serious imprecision of the results and thus low confidence in their reliability. 4 Downgraded due to high risk of sponsorship bias. 5 Downgrade due to heterogeneity ‐ I² = 49%. See above 6 Downgrade due to heterogeneity ‐ I² = 53%. See above.

Summary of findings 2. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) compared to tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) for people with cancer and depression.

| SSRIs compared to TCAs for patients with cancer and depression | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with cancer and depression Settings: in‐ and outpatients Intervention: SSRIs Comparison: TCAs | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty (Quality) of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| TCAs | SSRIs | |||||

| Efficacy as a continuous outcome Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | The mean efficacy as a continuous outcome (SMD) in the intervention groups was 0.08 standard deviations lower (0.34 lower to 0.18 higher) | 237 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |||

| Efficacy as a dichotomous outcome Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 1.10 (0.78 to 1.53 | 199 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 388 per 1000 | 454 per 1000 (256 to 799) | |||||

| Dropouts due to any cause (acceptability) Follow‐up: 4 to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 0.83 (0.53 to 1.3) | 237 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| 261 per 1000 | 217 per 1000 (138 to 339) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded as no studies described the outcome assessment as masked. This should be considered a major limitation, which is likely to result in a biased assessment of the intervention effect. 2 Downgraded as very low number of participants recruited (fewer than 100 individuals in both treatment arms) and 95% CI includes both no effect and appreciable benefit or appreciable harm, which suggests the risk of very serious imprecision of the results and thus low confidence in their reliability. 3 Downgraded as one study out of three had a high risk of sponsorship bias.

Primary outcome: efficacy at 6 to 12 weeks (continuous outcome)

1.1 Antidepressants versus placebo

We found no statistically significant difference between antidepressants as a class and placebo, with a standardised mean difference (SMD) of −0.45(95% confidence interval (CI) −1.01 to 0.11, five RCTs, 266 participants; very low certainty evidence) (see Analysis 1.1; Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Depression: efficacy as a continuous outcome at 6 to 12 weeks, Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Depression: efficacy at 6‐12 weeks (continuous outcome), outcome: 1.1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

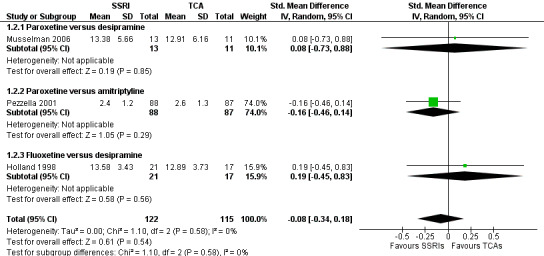

1.2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants

We found no statistically significant difference between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) as classes, with a SMD of −0.08 (95% CI −0.34 to 0.18, three RCTs, 237 participants) (see Analysis 1.2; Figure 5).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Depression: efficacy as a continuous outcome at 6 to 12 weeks, Outcome 2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Depression: efficacy at 6‐12 weeks (continuous outcome), outcome: 1.2 Antidepressants versus Antidepressants.

Secondary outcomes

2 Efficacy at one to four weeks (continuous outcome)

2.1 Antidepressants versus placebo

We found no statistically significant difference between antidepressants as a class and placebo, with a SMD of −0.29 (95% CI −0.72 to 0.13, five RCTs, 310 participants) (see Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Depression: efficacy as a continuous outcome at 1 to 4 weeks, Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

For antidepressants versus antidepressants, no studies provided data for this outcome. For efficacy after 12 weeks (continuous outcome), no studies provided data for this outcome.

3 Efficacy at 6 to 12 weeks (dichotomous outcome)

3.1 Antidepressants versus placebo

We found no statistically significant difference between antidepressants as a class and placebo in terms of response rate, with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.82 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.08, five RCTs, 417 participants; very low certainty evidence) (see Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Depression: efficacy as a dichotomous outcome at 6 to 12 weeks, Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

3.2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants

We found no statistically significant difference in terms of response rate between SSRIs and TCAs as classes, with a RR of 1.10 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.53, two RCTs, 199 participants, very low certainty evidence) (see Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Depression: efficacy as a dichotomous outcome at 6 to 12 weeks, Outcome 2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants.

4 Social adjustment at 6 to 12 weeks

4.1 Antidepressants versus antidepressants

Only one study provided data for this outcome, showing no statistically significant difference between paroxetine and amitriptyline, with a mean difference (MD) of 0.10 (95% CI −0.38 to 0.58, 175 participants, negative values favour paroxetine) on the MADRS rating scale (see Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Social adjustment at 6 to 12 weeks, Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus antidepressants.

For antidepressants versus placebo, no studies provided data for this outcome.

5 Quality of life at 6 to 12 weeks

5.1 Antidepressants versus placebo

We found no statistically significant difference between antidepressants as a class and placebo, with a SMD of 0.05 (95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.37, two RCTs, 152 participants) (see Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Quality of life at 6 to 12 weeks, Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

5.2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants

Only one study provided data for this outcome, showing no statistically significant difference between paroxetine and amitriptyline, with a MD of 6.50 (95% CI 0.21 to 12.79, 153 participants, negative values favour paroxetine) on the MADRS rating scale (see Analysis 5.2).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Quality of life at 6 to 12 weeks, Outcome 2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants.

6 Dropouts due to inefficacy

6.1 Antidepressants versus placebo

We found no statistically significant difference between antidepressants as a class and placebo, with a RR of 0.41 (95% CI 0.13 to 1.32, six RCTs, 455 participants) (see Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Dropouts due to inefficacy, Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

6.2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants

We found no statistically significant difference between SSRIs and TCAs as classes, with a RR of 0.85 (95% CI 0.14 to 5.06, three RCTs, 237 participants) (see Analysis 6.2).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Dropouts due to inefficacy, Outcome 2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants.

7 Dropouts due to side effects (tolerability)

7.1 Antidepressants versus placebo

We found no statistically significant difference between antidepressants as a class and placebo, with a RR of 1.19 (95% CI 0.54 to 2.62, seven RCTs, 479 participants) (see Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Dropouts due to side effects (tolerability), Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

7.2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants

We found no statistically significant difference between SSRIs and TCAs as classes, with a RR of 1.04 (95% CI 0.55 to 1.99, three RCTs, 237 participants) (see Analysis 7.2).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Dropouts due to side effects (tolerability), Outcome 2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants.

8 Dropouts due to any cause (acceptability)

8.1 Antidepressants versus placebo

We found no statistically significant difference between antidepressants as a class and placebo, with a RR of 0.85 (95% CI 0.52 to 1.38, seven RCTs, 479 participants; very low certainty evidence) (see Analysis 8.1).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Dropouts due to any cause (acceptability), Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

8.2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants

We found no statistically significant difference between SSRIs and TCAs as classes, with a RR of 0.83 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.30, three RCTs, 237 participants; very low certainty evidence) (see Analysis 8.2).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Dropouts due to any cause (acceptability), Outcome 2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants.

Subgroup analyses

1. Psychiatric diagnosis

Results from this subgroup analysis did not materially change the main findings for the primary outcome, which remains not statistically significant in both people with major depressive disorder and people with adjustment disorder, dysthymic disorder or depressive symptoms. This is true for both the 'antidepressant‐placebo' and the 'head‐to‐head' comparisons (see Analysis 9.1 and Analysis 9.2).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Subgroup analysis: psychiatric diagnosis, Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Subgroup analysis: psychiatric diagnosis, Outcome 2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants.

2. Previous history of depressive conditions

We did not perform this analysis since the data provided were not sufficient to measure the primary outcome in this subgroup of participants.

3. Antidepressant class

In the main analysis we pooled data separating the following classes of antidepressants: SSRIs, TCAs and other antidepressants. Considering the 'antidepressant‐placebo' comparison, we found no statistically significant effect for both SSRIs (SMD −0.21, 95% CI −0.50 to 0.08, four RCTs, 194 participants) and TCAs (MD 0.27, 95% CI ‐5.13 to 5.67, one trial, 17 participants). However, we found mianserin, the only compound in the 'other antidepressants' class, to be effective over placebo (MD −8.2, 95% CI −10.6 to −5.77, one trial, 55 participants) (see Analysis 1.1). In this analysis MDs are reported as SMDs. The difference between the subgroups was statistically significant (P value < 0.0001). The 'head‐to‐head' comparison did not show statistically significant differences between SSRIs and TCAs as classes (SMD −0.08, 95% CI −0.34 to 0.18, three studies, 237 participants) (see Analysis 1.2).

4. Cancer site

Results from this subgroup analysis did not materially change the main findings for the primary outcome. No statistically significant effect was found when pooling studies that enrolled only women with breast cancer (see Analysis 10.1 and Analysis 10.2). It was technically feasible to separate these two subgroups, however the 'other sites' subgroup could not be considered a reliable comparison with the 'breast cancer' subgroup because, even if in these studies people with different types of cancer were enrolled, the vast majority of them were actually affected by breast cancer.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Subgroup analysis: cancer site, Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Subgroup analysis: cancer site, Outcome 2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants.

5. Cancer stage

Results from this subgroup analysis did not materially change the main findings for the primary outcome (see Analysis 11.1 and Analysis 11.2). Two studies among those comparing antidepressants versus placebo enrolled only people with late‐stage disease (Costa 1985; Holland 1998), however the study by Costa 1985 did not provide data for the primary outcome (efficacy at 6 to 12 weeks) and was not included in the analysis. Other studies had a mixed population in terms of cancer stage, with the exception of Razavi 1996, in which only people in a stage 0 (carcinoma in situ, early form) were enrolled. Considering the 'head‐to‐head' comparison, only one study (Holland 1998) enrolled people with early‐stage disease, showing no statistically significant differences between SSRIs and TCAs as classes (MD 0.69, 95% CI −1.61 to 2.99, one trial, 38 participants), while other studies had a mixed population.

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Subgroup analysis: cancer stage, Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Subgroup analysis: cancer stage, Outcome 2 Antidepressants versus antidepressants.

6. Gender

This analysis is encompassed in the 'cancer site' analysis, because the 'female participant' subgroup matches with the 'breast cancer' subgroup (see Analysis 10.1). A subgroup analysis for men only was not feasible, since other studies enrolled both male and female participants.

Sensitivity analyses

1. Excluding trials in which the randomisation process is not clearly reported

We did not perform this sensitivity analysis because no studies, with the exception of Fisch 2003, reported clear details on random sequence generation and concealment of random allocation.

2. Excluding trials with unclear concealment of random allocation

See above.

3. Excluding trials that did not employ adequate blinding of participants, healthcare providers and outcome assessors

We did not perform this sensitivity analysis because no studies reported clear details on the procedures for ensuring blinding.

4. Excluding trials that did not employ depressive symptoms as their primary outcome

Only one study assessed depressive symptoms as a secondary outcome (Fisch 2003), and it contributed only to the 'antidepressants versus placebo' analysis. Results from this sensitivity analysis did not materially change the main findings for the primary outcome (see Analysis 12.1).

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Sensitivity analysis: excluding trials that did not employ depressive symptoms as their primary outcome, Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

5. Excluding trials with imputed data

Five studies did not impute missing data, applying a 'per protocol' or an 'as treated' analysis (EUCTR2008‐002159‐25‐FR; Fisch 2003; Navari 2008; Razavi 1996; Van Heeringen 1996). These studies contributed only to the 'antidepressants versus placebo' analysis. After removing trials with imputed data the meta‐analysis still did not show a statistically significant superiority of antidepressants over placebo, with a SMD of −0.64(95% CI ‐1.35 to 0.06, four trials, 231 participants) (see Analysis 13.1).

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Sensitivity analysis: excluding trials with imputed data, Outcome 1 Antidepressants versus placebo.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included a total of ten randomised controlled trials (RCTs), involving 885 participants, in the present systematic review. The included studies did not report all the outcomes that were prespecified in the protocol. Seven of the RCTs provided continuous data, which contributed to the meta‐analysis for the primary outcome (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2). Only one study (Navari 2008) did not provide data suitable for the meta‐analysis. The majority of studies provided detailed data on dropouts, while for some other secondary outcomes very few trials provided data (Analysis 4.1; Analysis 5.1; Analysis 5.2). Compared to the previous version of this systematic review, our updated electronic search and handsearch for new studies (and for new data on previously ongoing and 'awaiting classification' studies), allowed us to identify new data from one study (NCT00387348). However, this study contributed only to secondary outcomes (in particular Analysis 2.1, Analysis 7.1, Analysis 8.1) because of its relatively short follow‐up period (only four weeks). Therefore, the main data from the previous version of this systematic review and meta‐analysis remains unchanged.

Overall, we detected no evidence of a difference between antidepressants as a class and placebo in terms of efficacy (both on continuous and dichotomous outcomes), acceptability (dropouts due to any cause), and tolerability (dropouts due to adverse events). For the primary outcome ('efficacy as a continuous outcome at 6 to 12 weeks') we found only mianserin to be effective over placebo. For the primary outcome, the sensitivity analysis excluding trials with imputed data gave similar results. We cannot rule out benefit in the early response phase (one to four weeks), but this comes from an analysis with substantial statistical variation. No trials assessed follow‐up response (more than 12 weeks). In head‐to‐head comparisons, we retrieved only data for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and found no difference between these two classes.