Abstract

Background

Many people with schizophrenia do not reach a satisfactory clinical response with a standard dose of an initially prescribed antipsychotic drug. In such cases, clinicians face the dilemma of increasing the antipsychotic dose in order to enhance antipsychotic efficacy.

Objectives

To examine the efficacy of increasing antipsychotic dose compared to keeping the same dose in the treatment of people with schizophrenia who have not responded (as defined in the individual studies) to an initial antipsychotic drug trial. We also examine the adverse effects associated with such a procedure.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (10 June 2014, 6 October 2015, and 30 March 2017). We examined references of all included studies for further trials.

Selection criteria

All relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs), reporting useable data, comparing increasing the antipsychotic dose rather than maintaining the original dose for people with schizophrenia who do not respond to their initial antipsychotic treatment.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors independently extracted data . We analysed dichotomous data using relative risks (RR) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI). We analysed continuous data using mean differences (MD) and their 95% CI. We assessed risk of bias for included studies and used GRADE to create a 'Summary of findings' table.

Main results

Ten relevant RCTs with 675 participants are included in this review. All trials were double blind except one single blind. All studies had a run‐in phase to confirm they did not respond to their initial antipsychotic treatment. The trials were published between 1980 and 2016. In most studies the methods of randomisation, allocation and blinding were poorly reported. In addition sample sizes were often small, limiting the overall quality of the evidence. Overall, no clear difference was found between groups in terms of the number of participants who showed clinically relevant response (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.40, 9 RCTs, N = 533, low‐quality evidence), or left the study early due to adverse effects (RR 1.63, 95% CI 0.52 to 5.07, very low quality evidence), or due to any reason (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.90, 5 RCTs, N = 353, low‐quality evidence). Similarly, no clear difference was found in general mental state as measured by PANSS total score change (MD −1.44, 95% CI −6.85 to 3.97, 3 RCTs, N = 258, very low quality evidence). At least one adverse effect was equivocal between groups (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.50, 2 RCTs, N = 191, very low quality evidence). Data were not reported for time in hospital or quality‐of‐life outcomes. Finally, subgroup and sensitivity analyses did not show any effect on the primary outcome but these analyses were clearly underpowered.

Authors' conclusions

Current data do not show any clear differences between increasing or maintaining the antipsychotic dose for people with schizophrenia who do not respond to their initial antipsychotic treatment. Adverse effect reporting was limited and poor. There is an urgent need for further trials in order to determine the optional treatment strategy in such cases.

Plain language summary

Increasing versus maintaining the dose of antipsychotic medication for people with schizophrenia who do not respond to treatment

Review question

If a person with schizophrenia does not initially respond to an antipsychotic medication, is increasing the dose of this antipsychotic effective and safe?

Background

Many people with the serious mental illness schizophrenia do not respond fully (i.e. symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations still remain) with a standard dose of an initially prescribed antipsychotic drug. In such cases, clinicians can consider increasing the antipsychotic dose beyond regular thresholds or switching to a different antipsychotic drug in order to enhance antipsychotic efficacy. The evidence surrounding the optimal treatment strategy is scarce.

Searching for evidence

The Information Specialist of Cochrane Schizophrenia ran an electronic search of their specialised register up to 30 March 2017 for trials that randomised people with schizophrenia who were not responding to their initial antipsychotic treatment to receive either an increased antipsychotic dose or continue on the same dose. The search returned 1919 records, which were checked for eligibility by the review authors.

Evidence found

Ten trials met the review requirements and provided usable data. No clear difference between increasing the dose of the antipsychotic drug and continuing antipsychotic treatment at the same dose was shown for any efficacy (clinical response) or safety (incidence of adverse effects) outcomes. The evidence currently available is limited and of low or very low quality. In particular, very few studies reported adverse effects adequately.

Conclusions

The results of the present review show that there is no good‐quality evidence to support or refute the hypothesis that increasing the antipsychotic dose for patients not responding to their initial antipsychotic treatment differs from continuing antipsychotic treatment at the same dose. No clear evidence regarding safety is available. Therefore, no firm conclusions can be made. Larger, well‐designed trials are needed.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antipsychotic dose increase compared to antipsychotic dose continuation for non response in schizophrenia.

| Antipsychotic dose increase compared to antipsychotic dose continuation for non response in schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: non response in schizophrenia Setting: inpatients and outpatients Intervention: antipsychotic dose increase Comparison: antipsychotic dose continuation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with antipsychotic dose continuation | Risk with antipsychotic dose increase | |||||

| Global state: clinically relevant response: Assessed with response ratio follow‐up: range 2 weeks to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 1.09 (0.86 to 1.40) | 533 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 309 per 1000 | 336 per 1000 (265 to 432) | |||||

| Leaving the study early: tolerability ‐ leaving early due to adverse effects. Assessed with risk ratio follow‐up: range 2 weeks to 9 weeks | Study population | RR 1.63 (0.52 to 5.07) | 496 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ||

| 74 per 1000 | 121 per 1000 (39 to 376) | |||||

| Leaving the study early: acceptability ‐ leaving early due to any reason. Assessed with: Risk ratio follow‐up: range 2 weeks to 9 weeks | Study population | RR 1.30 (0.89 to 1.90) | 353 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 23 per 100 | 30 per 100 (20 to 43) | |||||

| General mental state : PANSS total score change* assessed with: Weighted mean difference follow‐up: range 2 weeks to 9 weeks | The mean general mental state ‐ PANSS total score change ranged from −8.9 to 0.03 points | MD 1.44 points lower (6.85 lower to 3.97 higher) | ‐ | 258 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3 4 5 | One other trial used the BPRS total score change and showed no clear difference between the two groups. Pre‐defined outcome: Clinically important change in general mental state not reported. |

| Adverse effects ‐ at least one adverse effect assessed with: Risk ratio follow‐up: range 2 weeks to 9 weeks | Study population | RR 0.91 (0.55 to 1.50) | 191 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 6 | ||

| 716 per 1000 | 652 per 1000 (394 to 1000) | |||||

| Service use: time in hospital | ‐ | see comment | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No studies reported this outcome. |

| Quality of life ‐ clinically important change in quality of life (defined as at least 50% improvement in HQLS) | Study population | not estimable | 17 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Imprecision for dichotomous outcomes: a) sample size should be >800 and/or total number of events>300; in our review, both numbers are much smaller. b) the pooled estimate of effect includes both no effect and an appreciable benefit or appreciable harm.

2 Inconsistency: Heterogeneity: Tau² = 1.03; Chi² = 11.24, df = 5 (P = 0.05); I² = 56%

3 Inconsistency: Heterogeneity: Tau² = 14.71; Chi² = 5.70, df = 2 (P = 0.06); I² = 65%

4 Imprecision for continuous outcomes: a) sample size is lower than 400, b) confidence interval includes no effect and the upper or lower confidence limit crosses the minimal important difference (MID), either for benefit of harm

5 Indirectness: The pre‐specified outcome (clinical important change in mental state) was not reported.

6 Inconsistency: Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.10; Chi² = 3.62, df = 1 (P = 0.06); I² = 72%

Background

Between one‐fifth and one‐third of people with schizophrenia do not respond to standard antipsychotic treatment adequately (Barnes 2003). One possibility to help these individuals is to increase the dose of the currently prescribed antipsychotic. This approach is based on the premise that increasing dose of an antipsychotic drug would lead to enhanced treatment efficacy (Kinon 2004). In the 1970s and the 1980s there was a trend to use high doses for the treatment of schizophrenia. This strategy, sometimes also called "rapid neuroleptization" (Neborsky 1981), was later given up when a narrative review suggested that high doses were not more efficacious than lower doses (Baldessarini 1988). However, this review was not restricted to non‐responding patients, who might still benefit from a dose increase if standard doses were not effective. The use of high antipsychotic doses is frequent practice, making a systematic review on this question important.

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia is often a chronic and disabling psychiatric disorder. It afflicts approximately 1% of the population world‐wide with little gender differences. Its typical manifestations are 'positive' symptoms such as fixed, false beliefs (delusions) and perceptions without cause (hallucinations), 'negative' symptoms such as apathy and lack of drive, disorganisation of behaviour and thought, and catatonic symptoms such as mannerisms and bizarre posturing (Carpenter 1994). The degree of suffering and disability is considerable with 80% to 90% not working (Marvaha 2004), and approximately 5% dying from suicide (Palmer 2005). Antipsychotic medication is the current treatment of choice in schizophrenia (Kane 1996). Unfortunately, a large number of patients experience no significant improvement despite pharmacological treatment (Lieberman 2005). These patients are often labelled as 'non‐responders'. The exact epidemiology of this phenomenon is not clearly understood, one reason being that the criteria for non response or treatment resistance differ (Howes 2017). But guidelines say that approximately 20% to 30% of patients do not respond to an adequate trial of an antipsychotic drug (Lehmann 2004). There are no clear predictors of non response to antipsychotics, but it is well established that people with a first episode respond better than chronic patients (Jäger 2007).

Description of the intervention

Increasing antipsychotic dose in non‐responsive schizophrenia patients is often done in incremental steps — the dosage is systematically increased until a clinical response is reached or the side effects become too pronounced and no further gain in efficacy is obtained. The effective dose ranges of second‐generation antipsychotics are overall better understood than those of first‐generation antipsychotics (Davis 2004; Baldessarini 1988). But even in their case the effective dose ranges are only based on mean values of many patients. Individual patients might well need higher doses beyond the officially approved ranges. Studies on plasma levels of antipsychotics show that there is a lot of interindividual variability, i.e. two different patients may have very different plasma levels when they receive the same dose of an antipsychotic, for example because of the differing activity of their liver enzymes that metabolise these drugs (mainly of the cytochrome P450 family). This may explain why some patients need much higher doses than others (Hiemke 2011).

How the intervention might work

The idea behind increasing the antipsychotic dose is that for a given non‐responsive schizophrenic patient an individual threshold of sensitivity has to be reached for the drug to be effective. It is well known that considerable individual differences exist in respect to pharmacokinetics antipsychotics, which directly influences their efficacy (Miller 2009). A major factor lies in the differences in the expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes which are responsible for the metabolism of many antipsychotic drugs. Polymorphisms in the genes coding for these enzymes exist which can lead to their excessive expression and thus to too fast elimination of drugs (so‐called 'ultrarapid metabolisers') and subsequent non response. More recent work suggested that some of the individual differences in response to antipsychotic drugs might have their source in the variability of ABCB1 genotypes, meaning that individuals with a favourable genotypic configuration show a lower risk of developing refractoriness to increasing antipsychotic dose (Vijayan 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

One of the major challenges in the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia is non response to antipsychotics. Increasing antipsychotic dose is one of the major strategies to do so which is frequently applied in clinical practice. Unfortunately, there is a lack of clear evidence to what extent this strategy is effective. This often results in uninformed clinical decisions which may lead to severe side effects, exacerbations of psychosis or relapse in many people with schizophrenia. Our aim is to provide a family of related systematic reviews of this topic in order to contribute to a more evidence‐based clinical practice. The review is also potentially important for policy makers, because the high frequency of non response and treatment resistance lead to high rates of disability and thus costs for society (Vos 2012).

This review is part of three 'sibling' Cochrane Reviews, investigating non response in people with schizophrenia ('Increasing antipsychotic dose versus switching antipsychotic for non response in schizophrenia' (Samara 2015b), and 'Reducing antipsychotic dose for people with schizophrenia' (title only)).

Objectives

To examine the efficacy of increasing antipsychotic dose compared to keeping the same dose in the treatment of people with schizophrenia who have not responded (as defined in the individual studies) to an initial antipsychotic drug trial. We also examine the adverse effects associated with such a procedure.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials. If a trial was described as 'double blind' but randomisation was implied, we included such trials in a sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis). We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by alternate days of the week. When people were given additional treatments, we only included data if the adjunct treatment was evenly distributed between groups and it was only the increasing dose group that was randomised.

Types of participants

Adults, however defined, with schizophrenia or related disorders — including schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder and delusional disorder, by any means of diagnosis — who were non‐responsive to their current antipsychotic treatment, irrespective of age, gender or race. We accepted any definition of non response that was used in the individual studies. It is a general strategy of the Cochrane Schizophrenia group to also include studies which did not use operationalised diagnostic criteria such as those of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM‐5), because in clinical routine practice such criteria are not meticulously used either.

Types of interventions

1. Dose increase

Any increase of the antipsychotic dose, irrespectively of how it was defined. The new doses could be either within recommended target dose ranges as described in the antipsychotics' labels or international recommendations (Gardner 2010), or higher.

2. Dose continuation

Continuation of the current antipsychotic dose.

Types of outcome measures

We divided all outcomes into short term (up to 3 months), medium term (more than 3 months up to 6 months) and long term (more than 6 months).

We endeavoured to report binary outcomes recording clear and clinically meaningful degrees of change (e.g. global impression of much improved, or more than 50% improvement on a rating scale as defined within the trials) before any others. Thereafter we listed other binary outcomes and then those that are continuous.

Primary outcomes

1. Global state: clinically relevant response ‒ as defined by trials *

* We expected that different trials would use different definitions of response. But studies have shown that, as long as relative measures of risk (relative risks, odds ratios) are applied, meta‐analytic results do not differ much depending on the exact cut‐off applied (Furukawa 2011).

2. Leaving the study early

2.1 Tolerability ‒ leaving early due to adverse effects

Secondary outcomes

1. Leaving the study early

1.1 Acceptability ‒ leaving early due to any reason 1.2 Efficacy ‒ leaving early due to inefficacy of treatment

2. Mental state

2.1 General mental state

2.1.1 Clinically important change in general mental state ‒ as defined by each of the studies 2.1.2 Average endpoint general mental state score 2.1.3 Average change in general mental state scores

2.2 Positive symptoms

2.2.1 Clinically important change in positive symptoms ‒ as defined by each of the studies 2.2.2 Average endpoint positive symptom score 2.2.3 Average change in positive symptom scores

2.3 Negative symptoms

2.3.1 Clinically important change in negative symptoms ‒ as defined by each of the studies 2.3.2 Average endpoint negative symptom score 2.3.3 Average change in negative symptom scores

3. Depression

3.1 Clinically important change in depressive symptoms ‒ as defined by each of the studies 3.2 Average endpoint depressive symptom score 3.3 Average change in depressive symptom scores

4. Aggressive behaviour

4.1 Clinically important change in aggressive behaviour ‒ as defined by each of the studies 4.2 Average endpoint aggressive behaviour score 4.3 Average change in aggressive behaviour score

5. Exacerbations of psychosis (as defined by the individual studies)

5.1. Time ill (number of days in exacerbation)

6. Service use

6.1 Hospitalisation ‒ time in hospital (days)

7. Adverse effects

7.1. At least one adverse effect 7.2. Specific side effects (as defined by the original authors, based on any reference values they applied)

8. Quality of life

8.1 Clinically important change in quality of life ‒ as defined by each of the studies 8.2 Average endpoint quality of life 8.3 Average change in quality of life

9. Satisfaction with care

9.1 Clinically important change in satisfaction with care ‒ as defined by each of the studies 9.2 Average endpoint satisfaction with care 9.3 Average change in satisfaction with care

'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2011), and the GRADE profiler (GRADE pro GDT), to export data from this review and create the 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes that we rated as important to patient care and decision making.

We aimed to select the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Global state: clinically relevant response ‒ as defined by trials.

Leaving the study early: tolerability ‒ leaving early due to adverse effects.

Leaving the study early: acceptability ‒ leaving early due to any reason.

General mental state ‒ clinically important change in general mental state scores.

Adverse effects ‒ at least one adverse effect.

Service use ‒ time in hospital.

Quality of life ‒ clinically important change in quality of life.

If data were not available for these pre‐specified outcomes but were available for ones that are similar, we presented the closest outcome to the pre‐specified one in the table but took this into account when grading the finding.

Search methods for identification of studies

We applied no language restriction within the limitations of the search tools.

Electronic searches

1. Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Study‐Based Register of Trials

On 30 March 2017, the Information Specialist searched the register using the following search strategies.

(Dosage Increasing*) in Intervention Field of STUDY

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Registry of Trials is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including AMED, BIOSIS, CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and registries of clinical trials) and their monthly updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings (see Group Module). There were no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected references of all included studies for further relevant studies.

2. Personal contact

We contacted the first author of each included study for information regarding unpublished trials. We noted any response in the Characteristics of included studies and thanked the authors in the Acknowledgements.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

At least two authors (EK, MTS) independently inspected citations from the searches to identify relevant abstracts. Where disputes arose, we acquired the full report for more detailed scrutiny. At least two review authors (EK, MTS) obtained and independently inspected full reports of the abstracts meeting the review criteria. We resolved disagreements by discussion with SL. Where it was not possible to resolve disagreement by discussion, we attempted to contact the authors of the study for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

Two review authors (MS, EK) independently extracted data from all included studies. Again, we discussed any disagreement, eventually with SL; documented decisions; and, if necessary, contacted authors of studies for clarification. We extracted data presented only in graphs and figures whenever necessary and possible. We attempted to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted data onto standard, simple forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if: a) the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument have been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); b) the measuring instrument has not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial; and c) the instrument is a global assessment of an area of functioning and not sub‐scores which are not, in themselves, validated or shown to be reliable. There are exceptions, however: we included sub‐scores from mental state scales measuring positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

Ideally the measuring instrument should either be i. a self‐report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly: we note if this is the case or not in Description of studies.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint) which can be difficult in unstable and difficult‐to‐measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided to use endpoint data primarily, and only use change data if the latter were not available. We combined endpoint and change data as we preferred to used mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences (Deeks 2011).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we applied the following standards to relevant continuous data before inclusion.

For endpoint data from studies including fewer than 200 participants:

when a scale starts from the finite number zero, we subtracted the lowest possible value from the mean, and divided this by the standard deviation. If this value is lower than 1, it strongly suggests that the data are skewed and we would exclude these data. If this ratio is higher than 1 but less than 2, there is a suggestion that the data are skewed: we would enter these data and test whether their inclusion or exclusion would change the results substantially. If such data changed results we would enter as 'other data'. Finally, if the ratio is larger than 2 we would include these data, because it is less likely that they are skewed (Altman 1996; Higgins 2011).

if a scale starts from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), which can have values from 30 to 210 (Kay 1986)), we would modify the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skewed data are present if 2 SD > (S − S min), where S is the mean score and 'S min' is the minimum score.

Please note: we would have entered all relevant data from studies of more than 200 participants in the analysis irrespective of the above rules, because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies. We also entered all relevant change data, as when continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether or not data are skewed.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we made efforts to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962), or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005a; Leucht 2005b). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for increased dose group. Where keeping to this made it impossible to avoid outcome titles with clumsy double‐negatives (e.g. 'Not un‐improved') we reported data where the left of the line indicated an unfavourable outcome. We noted this in the relevant graphs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Review authors (MTS and EK) worked independently to assess risk of bias by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to assess trial quality (Higgins 2011b). This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

If MTS and EK disagreed, they involved SI to make the final rating by consensus. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. We reported non‐concurrence in quality assessment, but if disputes arose as to which category we would allocate a trial then again we resolved by discussion.

The level of risk of bias was noted in the text of the review (Risk of bias in included studies), the Characteristics of included studies table and in the Table 1.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive than odds ratios (Boissel 1999); and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). The number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) and number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH), with confidence intervals, is intuitively attractive to clinicians but is problematic both in its accurate calculation in meta‐analyses and interpretation (Hutton 2009). For binary data presented in the 'Summary of findings' table, we calculated illustrative comparative risks where possible.

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes we estimated mean difference (MD) between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference (SMD)). However if scales of very considerable similarity were used, we presumed there was a small difference in measurement, and we calculated effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992), whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

If clustering had not been accounted for in primary studies, we would have presented data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. We would have contacted first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). If clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intra‐class correlation coefficient (ICC) [Design effect = 1 + (m − 1) * ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported we assumed it to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account intra‐class correlation coefficients and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would have been possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in people with severe mental illness, we used data of the first phase only of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involves more than two treatment arms, if relevant we presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. If data were binary we simply added and combined within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous we combined data following the formula in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not use these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

We share the concern that at some degree of loss to follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2010). However, from which degree of attrition onward this is a problem is unclear. Therefore we did not exclude studies on the basis of degree of attrition, but we took attrition into account in the 'Risk of bias' assessment.

2. Binary

We presented data on a 'once randomised, always analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis, ITT). Those leaving the study early were all assumed to have the same rates of outcome as those who completed.

3. Continuous

3.1 Assumptions about participants who left the trials early or who were lost to follow‐up

Various methods are available to account for participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up. Some trials just present the results of study completers, others use the method of 'last observation carried forward' (LOCF, Leucht 2007), while more recently methods such as multiple imputation or mixed‐effects models for repeated measurements (MMRM) have become more of a standard. While the last two methods seem somewhat better than LOCF (Leon 2006), we felt that the high percentage of participants leaving the studies early and differences in the reasons for leaving the studies early between groups is often the core problem in randomised schizophrenia trials. We therefore did not exclude studies based on the statistical approach used. However, for preference we used the more sophisticated approaches. For example, we preferred MMRM or multiple imputation to LOCF and we only presented completer analyses if some kind of ITT data were not available at all. Moreover, we addressed attrition in the 'Risk of bias' assessment.

3.2 Standard deviations

If standard deviations were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error and confidence intervals available for group means, and either P value or t value available for differences in mean, we calculated them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). When only the standard error (SE) was reported, we calculated standard deviations (SDs) by the formula SD = SE * √(n). The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions presents detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, t or F values, confidence intervals, ranges or other statistics (Higgins 2011a). If these formulae did not apply, we calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. We nevertheless examined the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations which we had not predicted would arise. When such situations or participant groups arose, we discussed these.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise. When such methodological outliers arose, we discussed these.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I² statistic

We investigated statistical heterogeneity between studies by considering the I² statistic alongside the Chi² P value. The I² statistic provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I² depends on i. magnitude and direction of effects and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from Chi² test, or a confidence interval for I²). We considered an I² estimate greater than or equal to 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi² statistic as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Deeks 2011). When substantial levels of heterogeneity were found in the primary outcome, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2011).

1. Protocol versus full study

We tried to locate protocols of included randomised trials. If the protocol was available, we compared outcomes in the protocol and in the published report . If the protocol was not available, we compared outcomes listed in the Methods section of the trial report with actually reported results.

2. Funnel plot

We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We planned not to use funnel plots for outcomes where there are 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies are of similar size. In future versions, where funnel plots are possible we will seek statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This does seem true to us as we are a priori expecting some clinical heterogeneity between the participants in the different trials. Therefore we chose the random‐effects model for analyses (DerSimonian 1986). There is, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model: it puts added weight onto small studies which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses

1.1 Antipsychotic drugs

We performed subgroup analyses based on the antipsychotic drugs included in the selected studies.

1.2 Clinical state, stage or problem

We undertook this review and provided an overview of the effects of dose increase versus dose maintenance for people with schizophrenia in general. In addition, however, we aimed to report data on subgroups of people in the same clinical state, stage and with similar problems.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

We reported if heterogeneity was high. First, we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data were correct we visually inspected the graph and we inspected closely studies outside of the company of the rest to identify reasons that might explain the heterogeneity. Decisions as to whether single studies should be excluded from the analysis, or whether a formal meta‐analysis should not be undertaken at all depend on issues such as whether the heterogeneity was due to differences in direction of effect or only to the degree of the difference between intervention and control (Higgins 2011a). When unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity was obvious we simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We did not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

1. Implication of randomisation

We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way as to imply randomisation. For the primary outcomes we included these studies; if their inclusion did not result in a substantive difference, they remained in the analyses. If their inclusion did result in important clinically significant but not necessarily statistically significant differences, we did not add the data from these lower quality studies to the results of the better trials, but presented such data within a subcategory.

2. Risk of bias

We analysed the effects of excluding trials that were judged to be at high risk of bias across one or more of the domains described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies. If the exclusion of trials at high risk of bias did not substantially alter the direction of effect or the precision of the effect estimates, then we included relevant data from these trials in the analysis. Studies with a high risk of bias in terms of randomisation or allocation concealment were excluded right from the start. When randomisation and allocation methods had not been described (and risk of bias was usually rated as unclear) we also entered such trials in a sensitivity analysis.

3. Imputed values

Where we had to make assumptions regarding missing SDs (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption/s and when we used data only from studies which provided SDs.

We also undertook a sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials where we used imputed values for ICC in calculating the design effect in cluster randomised trials.

4. Fixed and random effects

We synthesised data using a random‐effects model; however, we also synthesised data for the primary outcomes using a fixed‐effect model to evaluate whether this altered the results.

If substantial differences were noted in the direction or precision of effect estimates in any of the sensitivity analyses listed above, we did not pool data from the excluded trials with the other trials contributing to the outcome, but presented them separately.

Results

Description of studies

For substantive description of studies please see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Results of the search

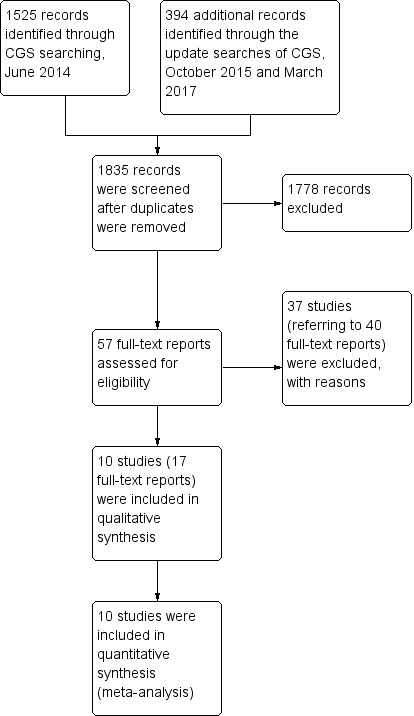

The initial search of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register yielded 1525 reports. We made two later searches of the same Trials Register (using the same search strategy): one in October 2015 which yielded 386 records; and one in March 2017 which yielded 8 records. A total of 1835 records remained after we removed duplicates. After excluding 1778 records based on abstract or title, we obtained and closely inspected 57 full‐text reports. From these, we included 10 studies (referring to 17 full‐text reports); and excluded 37 studies (referring to 40 full‐text reports) (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We selected 10 studies for inclusion in this review. The studies were published between 1980 and 2016 (for more details, see Characteristics of included studies and the accompanying ‘Risk of bias’ tables).

1. Study design

All studies were randomised; however, only two studies provided an adequate description of randomisation (Honer 2011; Sakurai 2016). All studies had a non‐randomised run‐in phase apart from one trial which had a randomised double‐blind run‐in phase of 2 weeks' duration (Loebel 2014).

2. Length of trials

The included trials varied in duration, both in terms of the run‐in phase and the main phase. The run‐in phase varied from 2 weeks (Huang 1987; Loebel 2014) to 4 weeks (Bjørndal 1980; Honer 2011; Kinon 1993; Lindenmayer 2011; McEvoy 1991; McGorry 2011; Sakurai 2016), whereas the main phase varied from 2 weeks (McEvoy 1991) to 12 weeks (Bjørndal 1980).

3. Participants

There were a total of 675 participants in the 10 included studies. Participants in seven of the included trials appear to have been inpatients (Bjørndal 1980; Huang 1987; Kinon 1993; Lindenmayer 2011; Loebel 2014; McEvoy 1991; McGorry 2011); while in the remaining three studies participants could be either in‐ or outpatients (Goff 2013; Honer 2011; Sakurai 2016). All studies bar one included patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia according to different operational diagnostic criteria such as Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (McEvoy 1991), DSM‐III (Huang 1987), DSM‐III‐R (Kinon 1993), DSM‐IV (Goff 2013; Honer 2011), DSM‐IV‐TR (Lindenmayer 2011; McGorry 2011), and ICD‐10 (Sakurai 2016) — the exception was Bjørndal 1980, which did not describe any diagnostic criteria. All studies included both male and female participants apart from two: Bjørndal 1980 included only male participants and Huang 1987 did not provide any data on the sex of the participants. The mean age of participants was 36.4 years.

4. Study size

Honer 2011 was the largest study (131 participants) followed by Sakurai 2016 (103 participants) and Loebel 2014 (95 participants) whereas Bjørndal 1980 and McGorry 2011 were the smallest studies (29 and 26 participants respectively). The remaining five studies had 48 to 75 participants.

5. Interventions

Ten studies compared antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose continuation. In four studies the dose increase was flexible (Bjørndal 1980; Honer 2011; McEvoy 1991; McGorry 2011), whereas in the remaining studies it was fixed. There was one study on fluphenazine (Kinon 1993), two on haloperidol (Bjørndal 1980; McEvoy 1991), two on quetiapine (Honer 2011; Lindenmayer 2011), one on lurasidone (Loebel 2014), one on risperidone (McGorry 2011), one on thiothixene (Huang 1987), one on ziprasidone (Goff 2013), and one on olanzapine or risperidone (Sakurai 2016).

6. Outcomes

A variety of scales were used to assess clinical response and adverse events. The reporting on efficacy and side effects was incomplete in the original publications. However, we were able to improve this situation by contacting the authors, some of whom agreed to share their data with us (see Acknowledgements).

6.1 Outcome scales

Details of scales that provided usable data are shown below.

6.1.1 Global state

Clinical Global Impression ‒ CGI (Guy 1976)

CGI is a 7‐point rating instrument that is commonly used in studies on schizophrenia. It enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness (CGI‐Severity) and/or overall clinical improvement (CGI‐Improvement) during therapy with low scores indicating decreased severity or greater improvement.

6.1.2 Mental state

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‒ BPRS (Overall 1962)

The BPRS is a scale used to measure the severity of psychiatric symptoms, including psychotic symptoms. The scale usually has 18 items (depending on the version the number of items could vary from 16 to 24), and each item is rated on a seven‐point scoring system varying from 'not present' (1) to 'extremely severe' (7). Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Nurses' Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation ‐ NOSIE‐30 (Honigfeld 1965; Honigfeld 1973)

The NOSIE‐30 is a ward behaviour rating scale, especially designed for use by nurses and other subprofessional personnel. This 30‐item scale is quick (can be completed in 5 to 10 minutes) and simple (requires minimum training). The 30 items (behaviours) are rated on a 5‐point scoring system varying from 'never' (0) to 'always' (4) based on their frequency during the three days prior to examination. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Positive and Negative Symptom Scale ‒ PANSS (Kay 1986)

The PANSS was developed from the BPRS and the Psychopathology Rating Scale. It is used to evaluate the positive, negative and general symptoms in schizophrenia. The scale has 30 items, and each item is rated on a 7‐point scoring system varying from 'absent' (1) to 'extreme' (7). Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms ‒ SANS (Andreasen 1982)

The SANS is a scale used to measure the severity of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. The scale is used to evaluate five domains of symptoms: alogia, affective blunting, avolition‒apathy, anhedonia‒asociality and attention impairment. Each symptom is rated on a 6‐point scoring system varying from 'absent' (0) to 'severe' (5). Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

6.1.3 Adverse events

Simpson Angus Scale ‒ SAS (Simpson 1970)

This 10‐item scale, with a scoring system of 0 to 4 for each item, measures drug‐induced parkinsonism, a short‐term drug‐induced movement disorder. A low score indicates low levels of parkinsonism.

Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale ‒ AIMS (NIMH 1970)

The AIMS has been used to assess tardive dyskinesia, a long‐term, drug‐induced movement disorder. However, using this scale in short‐term trials may also be helpful to assess some rapidly occurring abnormal movement disorders such as tremor. A low score indicates low levels of abnormal involuntary movements.

Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale ‒ BAS (Barnes 1989)

This scale comprises items rating the observable, restless movements that characterise akathisia, the subjective awareness of restlessness and any distress associated with the condition. These items are rated from 'normal' (0) to 'severe' (3). In addition, there is an item for rating the global severity (from 'absent' (0) to 'severe' (5)). A low score indicates low levels of akathisia.

6.1.4 Behaviour

Behavioral Activity Rating Scale ‒ BARS (Swift 2002)

The BARS was designed to measure the degree of activity for patients with agitated behaviour rather than to represent the severity of a specific diagnostic entity such as schizophrenia. The BARS describes seven levels of activity, from 'difficult or unable to rouse' (1) to 'violent, requires restraint' (7).

6.1.5 Functioning

Global Assessment of Functioning ‒ GAF (DSM‐IV‐TR 1994)

The GAF has been used to rate the social, occupational, and psychological functioning on a hypothetical continuum of mental health‒illness. The lowest scores are 1 to 10 corresponding to 'Persistent danger of severely hurting self or others OR persistent inability to maintain minimal personal hygiene OR serious suicidal act with clear expectation of death' and the highest scores are 91 to 100 corresponding to 'No symptoms, life's problems never seem to get out of hand, is sought out by others because of his or her many positive qualities'. A score of 0 is given for inadequate information. A high score indicates good functioning.

Social‐Adaptive Functioning Evaluation ‒ SAFE (Harvey 1997)

The SAFE was originally designed to rate severity of impairment in crucial adaptive functioning domains of geriatric patients in a restricted setting, but has now been adapted for use with people of all ages. The scale has 17 items that measure social‒interpersonal, instrumental, and life skills functioning and are rated by observation, caregiver contact, and interaction with the subject if possible. Scoring ranges from 'no impairment' (0) to 'extreme impairment' (4). A low score indicates good functioning.

Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale ‒ SOFAS (DSM‐IV‐TR 1994)

The SOFAS has been used to rate the social and occupational functioning on a hypothetical continuum of mental health‒illness. It takes into account impairments in functioning due to physical limitations or mental impairments, but not due to lack of opportunity and other environmental limitations. The lowest scores are 1 to 10 corresponding to 'Persistent hygiene problems, inability to maintain minimal personal hygiene. Unable to function without harming self or others or without considerable external support' and the highest scores are 91 to 100 corresponding to 'Superior functioning in a wide range of activities'. A score of 0 is given for inadequate information. A high score indicates good functioning.

6.1.6 Quality of Life

Heinrichs‐Carpenter‐Hanlon Quality of Life Scale ‒ HQLS (Heinrichs 1984; Carpenter 1994)

The HQLS is a semi‐structured interviewer‐administered scale containing 21 items divided in four subscales. The structure of the instrument establishes a series of topics to be explored, using specified sample probes. Each item is rated on a 7‐point scale (0 to 6) for which descriptive anchors are provided. High scores reflect normal or unimpaired function, and low scores reflect severe impairment of function.

Excluded studies

We excluded 40 full‐text articles on 37 trials. Three studies were excluded because they were not appropriately randomised (Agid 2013; Bai 2002; DeBuck 1972). Twenty‐three studies were excluded because they did not examine suitable participants (e.g. stable participants or not selected after a run‐in phase to confirm that they had failed to improve with their current antipsychotic treatment (Badgett 1996; Baker 2003; Bastecky 1982; Bondolfi 1995; Branchey 1981; Canuso 2010; Chen 1998; Clerc 1989; Daniel 1997; Ericksen 1978; Gardos 1971; Gulliver 2010; Harris 1997; Hirschowitz 1995; Itil 1970; Kane 1985; Lehmann 1980; McCreadie 1979; Mitchell 2004; NCT00862992; NCT01457339; NCT01569659; Suzuki 1992). Nine studies were excluded because of wrong interventions, most of them did not have a continuation control group (Bitter 1989; CN138032; Coryell 1998; Cookson 1987; de Leon 2007; Hirschowitz 1997; Janicak 1997; Simpson 1999; Volavka 1996). Two studies were excluded since no usable data were presented (NCT00539071; Dencker 1978).

Studies awaiting assessment

None.

Ongoing studies

None.

Risk of bias in included studies

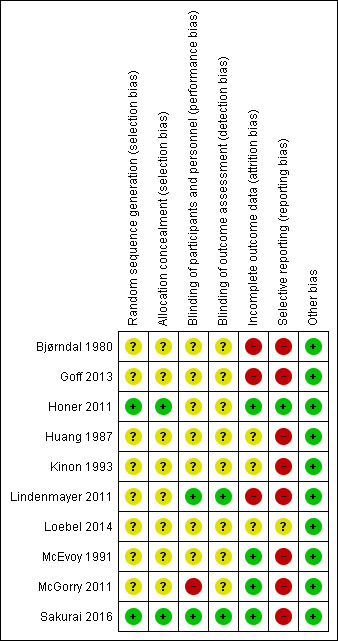

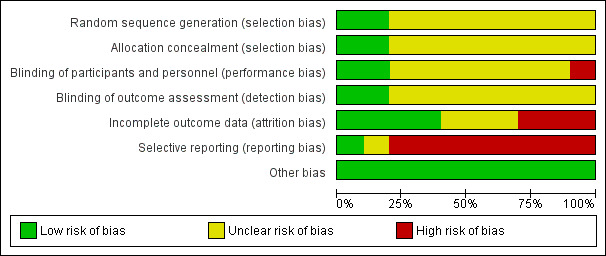

For graphical representations of our judgements of risk of bias please refer to Figure 2 and Figure 3. Full details of judgements are seen in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

We rated no studies at high risk for allocation bias. In two studies, random sequence generation was adequate (Honer 2011; Sakurai 2016). In the remaining eight studies, this was unclear: they were described as randomised, but none of them provided any further details about random sequence generation. As for allocation concealment, again only two studies provided information and we rated them as adequate (Honer 2011; Sakurai 2016). The remaining eight studies did not provide any details on allocation concealment.

Blinding

Concerning performance bias, we rated two studies at low risk of bias since it was explicitly mentioned that subjects, caregivers and investigators were blinded to the randomisation status (Lindenmayer 2011), and antipsychotics were provided in identical powder form in amount and colour (Sakurai 2016). However we rated one study at high risk of bias since it was described as single‐blind (McGorry 2011). The remaining seven studies we rated with an unclear risk of bias since the term "double‐blind" was the only description provided by the authors.

Concerning detection bias, we rated two studies with a low risk of bias since it was explicitly mentioned that outcome assessors were blinded to the randomisation status (Lindenmayer 2011; Sakurai 2016). All the remaining eight studies we rated with an unclear risk of bias since the term "blind" was the only description provided by the authors.

Incomplete outcome data

The number of participants leaving the studies early was relatively low (< 25%) in four studies which also used an ITT approach to analyse the results (Honer 2011; McEvoy 1991; McGorry 2011; Sakurai 2016); thus we rated these studies at low risk of bias. Three studies had an unclear risk of bias since this outcome was not adequately addressed (Huang 1987; Kinon 1993; Loebel 2014). The remaining three studies we rated with a high risk of bias (Bjørndal 1980; Goff 2013; Lindenmayer 2011).

Selective reporting

One study reported data on all predefined outcomes and we therefore rated it at low risk of bias (Honer 2011). We rated one study with an unclear risk of bias (Loebel 2014). The remaining eight studies we rated with a high risk of bias as not all outcomes were reported; usually, data on adverse effects were missing.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged all studies to be free of other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See: Table 1 for the main comparison 'Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose continuation'. We used risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous data and mean differences (MD) for continuous data, with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) throughout.

1. Comparison: Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance

1.1 Global state: 1a. Clinically relevant response ‒ as defined by trials

Nine studies provided data on the number of responders in the dose increase versus dose maintenance group; only Loebel 2014 did not provide any data on this outcome. There was no clear difference between dose increase versus dose maintenance in any of the nine included studies either when examined separately or pooled (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.40, 9 RCTs, N = 533, Analysis 1.1). Moreover, no significant heterogeneity was indicated (P = 0.37, I² = 8%). Response was defined as a higher than 0% BPRS total score reduction in Bjørndal 1980; as a 20% or more PANSS total score reduction in Goff 2013, Honer 2011 and Lindenmayer 2011; as a 20% or more BPRS total score reduction in McGorry 2011; and as a 25% or more PANSS total score reduction in Sakurai 2016. In the remaining three studies, response was defined by the score on a global improvement scale (Huang 1987; Kinon 1993); or by a combination of various criteria (McEvoy 1991).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 1 Global state: 1a. Clinically relevant response as defined by trials.

1.2 Global state: 1b. Any change (improvement on Global Assessment scale)

There was no clear difference in one single small study by Bjørndal 1980 for this outcome (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.80, 1 RCT, N = 23, Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 2 Global state: 1b. Any change (improvement in Global Assesment scale).

1.3 Global state: 2a. Average endpoint score (CGI‐Severity, high = poor)

Three studies reported the average CGI‐Severity score at endpoint (Honer 2011; McEvoy 1991; McGorry 2011). There was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment (MD −0.11, 95% CI −0.40 to 0.19, 3 RCTs, N = 99, Analysis 1.3 ). Moreover, no significant heterogeneity was indicated (P = 0.88, I² = 0%).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 3 Global state: 2a. Average endpoint score (CGI‐Severity , high = poor).

1.4 Global state: 2b. Average change score (CGI‐Severity, high = poor)

One study reported the average CGI‐Severity score at change (Loebel 2014). No clear effect between antipsychotic dose increase and dose maintenance was observed (MD −0.40, 95% CI −0.80 to −0.00, 1 RCT, N = 95, Analysis 1.4 ).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 4 Global state: 2b. Average change score ( CGI‐Severity, high = poor).

1.5 Global state: 2c. Average endpoint score (CGI‐Improvement, high = poor)

One study reported the average CGI‐Improvement score at endpoint (Sakurai 2016), and showed no difference between the two groups (MD 0.00, 95% CI −0.35 to 0.35, 1 RCT, N = 103, Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 5 Global state: 2c. Average endpoint score (CGI‐Improvement, high = poor).

1.6 Leaving the study early: 1. Tolerability ‒ due to side effects

Seven studies provided data on the number of participants leaving early due to side effects in the dose increase versus dose maintenance group (Honer 2011; Huang 1987; Lindenmayer 2011; Loebel 2014; McEvoy 1991; McGorry 2011; Sakurai 2016). There was no clear difference between dose increase versus dose maintenance group (RR 1.63, 95% CI 0.52 to 5.07, 7 RCTs, N = 496, Analysis 1.6), but there was some heterogeneity (P = 0.05, I² = 56%). The heterogeneity was due to Sakurai 2016 which had less attrition due to side effects in the dose continuation group compared to the dose increase group. There was no clear difference between the two groups in the remaining six studies.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 6 Leaving the study early: 1. Tolerability ‐ due to adverse events.

1.7 Leaving the study early: 2. Acceptability ‒ due to any reason

Five studies provided data on the number of participants leaving early due to any reason in the dose increase versus dose maintenance group (Honer 2011; Huang 1987; Lindenmayer 2011; McGorry 2011; Sakurai 2016). There was no clear difference between dose increase versus dose maintenance group in any of the five included studies either when examined separately or pooled (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.90, 5 RCTs, N = 353, Analysis 1.7). Moreover, no significant heterogeneity was indicated (P = 0.36, I² = 8%).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 7 Leaving the study early: 2. Acceptability of treatment ‐ due to any reason.

1.8 Leaving the study early: 3. Efficacy ‒ due to inefficacy

Four studies provided data on the number of participants leaving early due to inefficacy in the dose increase versus dose maintenance group (Honer 2011; Huang 1987; Lindenmayer 2011; Sakurai 2016). There was no clear difference between dose increase versus dose maintenance group in any of the four included studies either when examined separately or pooled (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.30 to 2.28, 4 RCTs, N = 336, Analysis 1.8). Moreover, no significant heterogeneity was indicated (P = 0.36, I² = 3%).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 8 Leaving the study early: 3. Efficacy ‐ due to inefficacy.

1.9 Mental state: 1a. General ‒ average endpoint score (PANSS total, high = poor)

Two studies reported the average PANSS total score at endpoint (Honer 2011; Lindenmayer 2011). There was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment for this outcome (MD −1.81, 95% CI −7.31 to 3.69, 2 RCTs, N = 191, Analysis 1.9). Moreover, no significant heterogeneity was indicated (P = 0.63, I² = 0%).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 9 Mental state: 1a. General ‐ average endpoint score (PANSS total, high = poor).

1.10 Mental state: 1b. General ‒ average change score (PANSS total, high = poor)

Three studies reported the average PANSS total score change (Lindenmayer 2011; Loebel 2014; Sakurai 2016). Lindenmayer 2011 and Sakurai 2016 showed a trend in favour of dose maintenance versus dose increase whereas Loebel 2014 study showed a clear difference in favour of dose increase versus dose maintenance. Overall, there was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment for this outcome (MD −1.44, 95% CI −6.85 to 3.97, 3 RCTs, N = 258, Analysis 1.10) but heterogeneity was considerable, even though not significant (P = 0.06, I² = 65%).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 10 Mental state: 1b. General ‐ average change score (PANSS total, high = poor).

1.11 Mental state: 1c. General ‒ average endpoint and/or change score (PANSS total, high = poor)

Four studies reported the average PANSS total score at endpoint or change or both; Honer 2011 reported only endpoint scores, Loebel 2014 and Sakurai 2016 only change scores, whereas Lindenmayer 2011 reported both endpoint and change scores. In this analysis we used endpoint scores for the latter study in accordance with our protocol. There was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment for this outcome (MD −2.13, 95% CI −6.16 to 1.90, 4 RCTs, N = 389, Analysis 1.11). Moreover, no significant heterogeneity was indicated (P = 0.14, I² = 46%).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 11 Mental state: 1c. General ‐ average endpoint and/or change score (PANSS total, high = poor).

1.12 Mental state: 1d. General ‒ average endpoint score (BPRS total, high = poor)

Three studies reported the average BPRS total score at endpoint (Kinon 1993; McEvoy 1991; McGorry 2011). There was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment (MD −1.25, 95% CI −4.60 to 2.11, 3 RCTs, N = 99, Analysis 1.12). Moreover, no significant heterogeneity was indicated (P = 0.98, I² = 0%).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 12 Mental state: 1d. General ‐ average endpoint score (BPRS total, high = poor).

1.13 Mental state: 1e. General ‒ average change score (BPRS total, high = poor)

Only one study reported the average BPRS total score change (Huang 1987). There was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment (MD −2.38, 95% CI −6.15 to 1.39, 1 RCT, N = 42, Analysis 1.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 13 Mental state: 1e. General ‐ average change score (BPRS total, high = poor).

1.14 Mental state: 1f. General ‒ average endpoint and/or change score (BPRS total, high = poor)

Four studies reported the average BPRS total score at endpoint or change (Huang 1987; Kinon 1993; McEvoy 1991; McGorry 2011). There was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment for this outcome (MD −1.75, 95% CI −4.25 to 0.76, 4 RCTs, N = 141, Analysis 1.14). Moreover, no significant heterogeneity was indicated (P = 0.97, I² = 0%).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 14 Mental state: 1f. General ‐ average endpoint and/or change score (BPRS total, high = poor).

1.15 Mental state: 1g. General average change score (NOSIE total, high = poor)

Only one study reported the average NOSIE total score change (Huang 1987). There was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment (MD 3.70, 95% CI −5.38 to 12.78, 1 RCT, N = 42, Analysis 1.15).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 15 Mental state: 1g. General ‐ average change score (NOSIE total, high = poor).

1.16 Mental state: 2a. Positive symptoms ‒ clinically important change

There was no clear difference in one single small study by McGorry 2011 for this outcome (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.58 to 3.07, 1 RCT, N = 17, Analysis 1.16).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 16 Mental state: 2a. Positive symptoms ‐ Clinically important change.

1.17 Mental state: 2b. Positive symptoms ‒ average endpoint subscore (PANSS positive, high = poor)

Two studies reported the average PANSS positive subscore at endpoint (Honer 2011; Lindenmayer 2011). There was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment for this outcome (MD −0.94, 95% CI −2.79 to 0.90, 2 RCTs, N = 191, Analysis 1.17). Moreover, no significant heterogeneity was indicated (P = 0.38, I² = 0%).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 17 Mental state: 2b. Positive symptoms ‐ average endpoint subscore (PANSS positive, high = poor).

1.18 Mental state: 2c. Positive symptoms ‒ average change subscore (PANSS positive, high = poor)

Three studies reported the average PANSS positive subscore change (Goff 2013; Lindenmayer 2011; Sakurai 2016). There was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment for this outcome (MD 0.04, 95% CI −1.31 to 1.40, 3 RCTs, N = 238, Analysis 1.18). Moreover, no significant heterogeneity was indicated (P = 0.20, I² = 38%).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 18 Mental state: 2c. Positive symptoms ‐ average change subscore (PANSS positive, high = poor).

1.19 Mental state: 2d. Positive symptoms ‒ average endpoint subscore (BPRS positive subscore, high = poor)

There was no clear difference in one single small study by McGorry 2011 for this outcome (MD 0.40, 95% CI −2.94 to 3.74, 1 RCT, N = 17, Analysis 1.19).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 19 Mental state: 2d. Positive symptoms ‐ average endpoint subscore (BPRS positive,high = poor).

1.20 Mental state: 3a. Negative symptoms ‒ average endpoint subscore (PANSS negative, high = poor)

Two studies reported the average PANSS negative subscore at endpoint (Honer 2011; Lindenmayer 2011). There was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment for this outcome (MD 0.32, 95% CI −1.48 to 2.11, 2 RCTs, N = 191, Analysis 1.20). Moreover, no significant heterogeneity was indicated (P = 0.64, I² = 0%).

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 20 Mental state: 3a. Negative symptoms ‐ average endpoint subscore (PANSS negative, high = poor).

1.21 Mental state: 3b. Negative symptoms ‒ average change subscore (PANSS negative, high = poor)

Two studies reported the average PANSS negative subscore change (Lindenmayer 2011; Sakurai 2016). There was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment for this outcome (MD −0.15, 95% CI −0.96 to 0.67, 2 RCTs, N = 163, Analysis 1.21). Moreover, no significant heterogeneity was indicated (P = 0.80, I² = 0%).

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 21 Mental state: 3b. Negative symptoms ‐ average change subscore (PANSS negative, high = poor).

1.22 Mental state: 3c. Negative symptoms ‒ average endpoint subscore (BPRS negative, high = poor)

There was no clear difference in one single small study by McGorry 2011 for this outcome (MD −0.40, 95% CI −1.97 to 1.17, 1 RCT, N = 17, Analysis 1.22).

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 22 Mental state: 3c. Negative symptoms ‐ average endpoint subscore (BPRS negative, high = poor).

1.23 Mental state: 3d. Negative symptoms ‒ average endpoint score (SANS, high = poor)

One study reported the average SANS score at endpoint (Kinon 1993). There was no clear difference between dose increase and dose maintenance antipsychotic treatment for this outcome (MD 1.50, 95% CI −14.33 to 17.33, 1 RCT, N = 34, Analysis 1.23).

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 23 Mental state: 3d. Negative symptoms ‐ average endpoint score (SANS, high = poor).

1.24 Adverse effects ‒ At least one adverse effect

Two studies — Honer 2011 and Lindenmayer 2011 — reported the numbers of participants with at least one adverse effect but did not reveal a clear difference between the antipsychotic dose increase group (75.2%) versus the antipsychotic dose maintenance group (71.6%), Analysis 1.24. The results were considerably but not significantly heterogeneous (P = 0.06, I² = 72%). It should be noted that, particularly in recent trials, efficacy related events such as exacerbation of psychosis can also be considered adverse events which may in part explain the heterogeneity.

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 24 Adverse effects ‐ At least one adverse effect.

1.25 Adverse effects ‒ Cardiac: QTc prolongation

Two studies reported the numbers of participants with QTc prolongation (Goff 2013; Honer 2011). There was no clear difference between the two groups. In total there were two participants with QTc prolongation in the antipsychotic dose increase group (1.6%) and no events in the dose maintenance group (0%) (RR 2.47, 95% CI 0.12 to 50.39, 2 RCTs, N = 206; heterogeneity test: not applicable, Analysis 1.25).

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 25 Adverse effects ‐ Cardiac: QTc prolongation.

1.26 Adverse effects ‒ Cardiac: Orthostatic hypotension

Two studies reported the numbers of participants with orthostatic hypotension (Huang 1987; Lindenmayer 2011). There was no clear difference between the two groups. In total, 3 out of 50 participants in the antipsychotic dose increase group and 3 out of 52 participants in the dose maintenance group presented with orthostatic hypotension (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.25 to 4.82, 2 RCTs, N = 102; heterogeneity test: P = 0.43, I² = 0%, Analysis 1.26).

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 26 Adverse effects ‐ Cardiac: Orthostatic hypotension.

1.27 Adverse effects ‒ Cardiac: Palpitations

One study reported data in terms of participants reporting palpitations (Huang 1987). There was no clear difference between the antipsychotic dose increase group (4.8%) versus the antipsychotic dose maintenance group (0%) (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.13 to 69.70, 1 RCT, N = 42, Analysis 1.27).

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 27 Adverse effects ‐ Cardiac: Palpitations.

1.28 Adverse effects ‒ Cardiac: Premature Ventricular Contractions

One study reported data in terms of participants with premature ventricular contractions (Huang 1987). There was no clear difference between the antipsychotic dose increase group (4.8%) versus the antipsychotic dose maintenance group (0%) (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.13 to 69.70, 1 RCT, N = 42, Analysis 1.28).

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 28 Adverse effects ‐ Cardiac: Premature Ventricular Contractions.

1.29 Adverse effects ‒ Constipation

Two studies reported the numbers of participants with constipation (Huang 1987; Lindenmayer 2011). There was no clear difference between the two groups. In total there were five participants with constipation in the antipsychotic dose increase group (10%) and three participants in the dose maintenance group (5.8%) (RR 1.53, 95% CI 0.44 to 5.38, 2 RCTs, N = 102; heterogeneity test: P = 0.62, I² = 0%, Analysis 1.29).

1.29. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 29 Adverse effects ‐ Constipation.

1.30 Adverse effects ‐ Dizziness

Two studies reported the numbers of participants with dizziness (Honer 2011; Huang 1987). There was no clear difference between the two groups. In total there were 18 patients with dizziness in the antipsychotic dose increase group (16.5%) and 15 patients in the dose maintenance group (23.4%) (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.44, 2 RCTs, N = 173; heterogeneity test: P = 0.56, I² = 0%, Analysis 1.30).

1.30. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 30 Adverse effects ‐ Dizziness.

1.31 Adverse effects ‒ Drooling

One study reported data in terms of participants complaining of drooling (Huang 1987). There was no clear difference between the antipsychotic dose increase group (9.5%) versus the antipsychotic dose maintenance group (4.8%) (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.20 to 20.41, 1 RCT, N = 42, Analysis 1.31).

1.31. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antipsychotic dose increase versus antipsychotic dose maintenance, Outcome 31 Adverse effects ‐ Drooling.

1.32 Adverse effects ‒ Death (suicide or natural cause)

One study reported that there were no deaths or suicides during the trial in any of the two groups (Honer 2011).

1.33 Adverse effects ‒ Extrapyramidal: Categorical deterioration (AIMS score)