Abstract

Background

People with stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) are at increased risk of future stroke and other cardiovascular events. Stroke services need to be configured to maximise the adoption of evidence‐based strategies for secondary stroke prevention. Smoking‐related interventions were examined in a separate review so were not considered in this review. This is an update of our 2014 review.

Objectives

To assess the effects of stroke service interventions for implementing secondary stroke prevention strategies on modifiable risk factor control, including patient adherence to prescribed medications, and the occurrence of secondary cardiovascular events.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (April 2017), the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group Trials Register (April 2017), CENTRAL (the Cochrane Library 2017, issue 3), MEDLINE (1950 to April 2017), Embase (1981 to April 2017) and 10 additional databases including clinical trials registers. We located further studies by searching reference lists of articles and contacting authors of included studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated the effects of organisational or educational and behavioural interventions (compared with usual care) on modifiable risk factor control for secondary stroke prevention.

Data collection and analysis

Four review authors selected studies for inclusion and independently extracted data. The quality of the evidence as 'high', 'moderate', 'low' or 'very low' according to the GRADE approach (GRADEpro GDT).Three review authors assessed the risk of bias for the included studies. We sought missing data from trialists.The results are presented in 'Summary of findings' tables.

Main results

The updated review included 16 new studies involving 25,819 participants, resulting in a total of 42 studies including 33,840 participants. We used the Cochrane risk of bias tool and assessed three studies at high risk of bias; the remainder were considered to have a low risk of bias. We included 26 studies that predominantly evaluated organisational interventions and 16 that evaluated educational and behavioural interventions for participants. We pooled results where appropriate, although some clinical and methodological heterogeneity was present.

Educational and behavioural interventions showed no clear differences on any of the review outcomes, which include mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure, mean body mass index, achievement of HbA1c target, lipid profile, mean HbA1c level, medication adherence, or recurrent cardiovascular events. There was moderate‐quality evidence that organisational interventions resulted in improved blood pressure control, in particular an improvement in achieving target blood pressure (odds ratio (OR) 1.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.09 to1.90; 13 studies; 23,631 participants). However, there were no significant changes in mean systolic blood pressure (mean difference (MD), ‐1.58 mmHg 95% CI ‐4.66 to 1.51; 16 studies; 17,490 participants) and mean diastolic blood pressure (MD ‐0.91 mmHg 95% CI ‐2.75 to 0.93; 14 studies; 17,178 participants). There were no significant changes in the remaining review outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

We found that organisational interventions may be associated with an improvement in achieving blood pressure target but we did not find any clear evidence that these interventions improve other modifiable risk factors (lipid profile, HbA1c, medication adherence) or reduce the incidence of recurrent cardiovascular events. Interventions, including patient education alone, did not lead to improvements in modifiable risk factor control or the prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events.

Plain language summary

Healthcare interventions for reducing the risk of future stroke in people with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA)

Review question

How effective are healthcare interventions for preventing a recurrent stroke or other cardiovascular events in people who have had a stroke or a transient ischaemic attack (TIA: also known as a mini‐stroke)?

Background

Stroke and TIA are diseases caused by interruptions in the blood supply to the brain. People who experience a stroke or TIA are at risk of future stroke. Several medications and lifestyle changes can be used to lower stroke risk by improving the control of modifiable risk factors such as blood pressure, blood fats, being overweight, raised blood sugar, and the use of preventive medications. These risk factors are often not managed effectively following a stroke or TIA. It is important to identify healthcare interventions that can help prevent stroke by improving these risk factors. Interventions in this review targeted patients or clinicians, or both (aimed at education or changing behaviour, or both); and organisations (e.g. changing the way services were provided).

This is an update of our review published in 2014.

Search date

We searched for studies up to April 2017.

Study characteristics

This updated review included 16 new studies involving 25,819 participants, resulting in a total of 42 studies including 33,840 with stroke or TIA whose average age ranged from 60 to 74.3 years. Most studies took place in primary care or community settings. Sixteen studies involved educational or behavioural interventions for participants and 26 studies mostly involved organisational interventions. Most interventions lasted for between three and 12 months, with follow‐up from three months up to three years.

Key results

Changes to healthcare services that looked at patient education or behaviour only, without any alterations in the organisation of patient care, showed no clear evidence of improvements in risk factors for stroke. Changes in the organisation of healthcare services resulted in improvements in blood pressure control. The effects of these interventions on changes in blood fats, blood sugar, body weight, or use of medicines were not conclusive.

We identified 24 ongoing studies suggesting that research in this area is increasing.

Quality of the evidence

The available evidence was assessed as moderate‐ or low‐quality because of variations in methods used and results reported.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Stroke is defined as a rapidly developing neurological deficit of presumed vascular origin, lasting for over 24 hours or leading to death (WHO 1978). Transient ischaemic attack (TIA) is an expression used traditionally to describe comparable neurological deficits lasting for fewer than 24 hours (Albers 2002). More recently, a new definition of TIA has been proposed, omitting the arbitrary 24‐hour time frame and identifying a TIA as a "transient episode of neurological dysfunction caused by focal brain, spinal cord, or retinal ischaemia, without acute infarction" (Easton 2009).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that cerebrovascular disease (stroke) is the second leading cause of mortality and disease burden among adults aged 60 years and over (Feigin 2014; Feigin 2016; Fourth SSNAP Annual Report 2016/17; Stroke Association 2018; WHO 2017). Following a TIA or minor stroke people have a 5.1% risk of stroke recurrence in the next year (Amarenco 2016). Long‐term cohort studies have demonstrated that the risk of cardiovascular events remains high for at least 10 years after stroke or TIA (Touze 2005; Van Wijk 2005). Secondary prevention strategies aim to prevent recurrent events by improving modifiable risk factor control. National stroke guidelines identify clinical conditions (hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, and obesity) and lifestyle factors (smoking, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, and excess alcohol consumption) as significant modifiable risk factors that should be targeted for secondary prevention (Canadian Stroke Best Practices 2017; ESO 2008; Kernan 2014; National Stroke Foundation 2017; SIGN 2008; Stroke Audit 2016). The strength of evidence for benefit from modifying risk factors varies: there is direct clinical trial evidence for treatment of hypertension and raised lipids, anti‐platelet drugs, anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation, surgery for carotid stenosis and, more recently, insulin resistance (Kernan 2016). The evidence for lifestyle interventions such as improving control of diabetes, weight loss, smoking cessation, and alcohol reduction relies on observational studies (Hankey 2014).

Description of the intervention

For the purposes of this review, we considered stroke services to include all services responsible for providing acute and follow‐up care to people with stroke and TIA. Stroke services exist as part of diverse healthcare systems, with specific treatment goals varying according to national clinical guidelines. Acute stroke services include organised inpatient (stroke unit) care and specialist TIA clinics (RCP 2016; Stroke Unit Trialists' Collaboration 2013). Recommendations for secondary prevention can be initiated as part of a co‐ordinated treatment programme during acute hospitalisation (Ovbiagele 2004). However, primary care services are well placed to monitor patient risk factors, encourage lifestyle change and review secondary prevention medications on an ongoing basis (RCP 2016). Primary care aims to be characterised by person‐centred, comprehensiveness, continuity of care, and community participation (Starfield 2002; WHO 2008). Social care services and voluntary sector organisations can also work in partnership with primary care to deliver healthy living support (NAO 2005). Stroke service interventions are considered complex interventions since they often contain several interacting components and may require complex behaviours, organisational change, or the assessment of numerous outcome measures (Craig 2008; Redfern 2008).

How the intervention might work

Stroke services addressing secondary prevention aim to improve patient adherence with medication regimens and lifestyle advice. Several classes of medication reduce stroke incidence by modifying cardiovascular risk. For example, long‐term antiplatelet medication in those with a history of stroke or TIA is associated with a significant 25% reduction in secondary vascular events (Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration 2002; Barber 2016). Similarly, antihypertensive and statin medications are associated with improvements in secondary prevention (Collins 2016; Ettehad 2016; Logue 2015; Preiss 2015; Sundström 2014;). Meta‐analyses report that moderate to high physical activity (Bennett 2017; Fan 2017), moderate alcohol consumption (Holmes 2014; Reynolds 2003), reduction of salt intake (Aburto 2013; He 2013), and specific dietary changes (He 2004; He 2006) can also facilitate stroke prevention and cardiovascular risk reduction. An international case‐control study identified five modifiable risk factors accounting for 83% of the population attributable risk (PAR) for stroke (O'Donnell 2010; Perk 2012). Targeting multiple risk factors may have additive benefits for secondary prevention, for example, a modelling study predicted that a 80% cumulative risk reduction in recurrent vascular events could be achieved by combining dietary modification, exercise, aspirin, a statin, and an antihypertensive agent (Hackam 2007; Perk 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

Most people with stroke have at least one cardiovascular risk factor and hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, smoking, and obesity are often inadequately managed during follow‐up (Hankey 2014; Herttua 2016; Kernan 2014; Perreault 2012; Xu 2017). Although the effectiveness of secondary prevention medications is well‐established, non‐treatment rates for antithrombotic, antihypertensive, and statin therapies remain high after stroke (Hankey 2014; Raine 2009) and TIA (Lager 2012). This includes a large proportion due to behavioural factors such as smoking and low physical activity (Feigin 2016). Only 31% of people with stroke and 35% of people with TIA receive combination treatment with all three medication classes (Ramsay 2007). Furthermore, adherence to secondary prevention medications falls progressively as time since the primary stroke elapses (Glader 2010). As strategies for stroke prevention are not optimally implemented, substantial benefits stand to be gained from improving the use of evidence‐based interventions (Goldstein 2008).

Several studies have revealed inequalities in the provision of stroke care with older people being less likely to receive or adhere to secondary prevention medication (De Schryver 2005; Raine 2009; Ramsay 2007). Similarly, people with stroke who have more severe disability (Barthel scores of 14 or less) are less likely to receive appropriate secondary prevention than those with mild disability (Barthel score 15 to 20) (Rudd 2004). Ethnic groups are also reported to differ with respect to patterns in behavioural risk factors for stroke (Dundas 2001). These subgroups of people may require targeted interventions to improve risk factor control.

Service interventions used for other conditions, particularly secondary prevention of ischaemic heart disease, may be relevant to the secondary prevention of stroke (Buckley 2010; Kernan 2014). However, more direct evidence is needed to guide improvements in follow‐up care after stroke or TIA. For example, stroke commonly results in cognitive impairments or physical disabilities that are likely to influence both intervention design and outcomes. To date, there are no systematic reviews that have considered the impact of stroke service interventions on cardiovascular risk factor control or adherence to secondary prevention medications. An assessment of the quality and outcomes of previous studies in this field will inform the development of new interventions.

Objectives

To assess the effects of stroke service interventions for implementing secondary stroke prevention strategies on modifiable risk factor control, including patient adherence to prescribed medications, and the occurrence of secondary cardiovascular events.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included published or unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with a minimum follow‐up of three months after the start of the intervention. Parallel group trials, cluster‐randomised trials and cross‐over trials were eligible for inclusion in the review.

Types of participants

We included adults (aged 18 years and over) with a confirmed diagnosis of ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, or transient ischaemic attack (TIA).

Types of interventions

For the purposes of this review, we defined stroke service educational or organisational interventions as alternative models of care that are implemented to improve patient outcomes following stroke or TIA. We included stroke service interventions that were intended to improve modifiable risk factor control. We focused on interventions that aimed to improve modifiable risk factor control through increased adherence to existing recommendations for secondary stroke prevention (e.g. recommendations in international stroke guidelines). We did not consider smoking‐related interventions which have been extensively reported elsewhere (Critchley 2012; Stead 2013a; Stead 2013b; Stead 2017; Taylor 2017; Whittaker 2016).

Following EPOC guidelines (EPOC 2015) we considered the following intervention categories (pre‐specified in the review protocol). Because educational and organisational interventions differ in their theoretical frameworks, the protocol stated these would be analysed separately (Lager 2011).

Educational and behavioural interventions for stroke patients.

Educational and behavioural interventions for stroke service providers.

Organisational interventions (subdivided into the following categories developed by Wensing 2006):

revision of professional roles, e.g. involvement of non‐physician staff in prevention clinics;

collaboration between multidisciplinary teams, e.g. interventions promoting effective liaison between primary and secondary care teams;

integrated care services, e.g. disease and case management programs where patient care follows protocols for screening, education and treatment or monitoring;

knowledge management systems, e.g. computerised decision support on medication prescribing, shared medical records;

quality management, e.g. guideline and protocol development;

financial incentives, e.g. the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework (NHS 2014).

We excluded interventions that were intended to improve physical rehabilitation or knowledge of stroke in general, surgical interventions, and interventions testing new pharmacological therapies. We also excluded exercise training programs for people with stroke or TIA which are the subject of other Cochrane Reviews (MacKay‐Lyons 2013; Saunders 2016).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Target achievement or mean reductions, or both, for blood pressure, lipid profile (total cholesterol), high density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides (TG), glycaemic control (HbA1c), body mass index (BMI), or validated cardiovascular risk score.

Any indicator of patient adherence to secondary prevention medications, e.g. self‐reported medication adherence or medication persistence, medication possession, individual patient data on prescriptions, pharmacy claims, electronic monitoring, drug tracers in blood or urine. Secondary prevention medications include those to lower causal risk factors (blood pressure, lipids, etc.) as well as antithrombotics to directly reduce the risk of a cerebrovascular event.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary cardiovascular events: stroke, myocardial infarction, or vascular death or composites. Because this review focused on long‐term prevention, we did not include surgical interventions for carotid stenosis nor identification and management of atrial fibrillation. We also excluded other more recently identified risk factors, such as insulin resistance.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialised register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We searched for trials in all languages and arranged for translation of relevant papers where necessary.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases to identify relevant trials:

Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (to April 2017);

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group Trials Register (to April 2017);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 5) in the Cochrane Library (searched May 2017) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE in Ovid (1950 to April 2017) (Appendix 2);

Embase in Ovid (1981 to April 2017) (Appendix 3);

CINAHL in EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1982 to April 2017) (Appendix 4);

AMED in Ovid (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database; 1985 to April 2017) (Appendix 5);

British Nursing Index (BNI) in Ovid (1985 to April 2017) (Appendix 6);

Web of Science Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science (1970 to April 2017) (Appendix 7); and

BiblioMap (health promotion research) (April 2017) (www.eppi.ioe.ac.uk/webdatabases/Intro.aspx?ID=7).

We also searched the following databases of ongoing trials and grants registers:

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched April 2017) (Appendix 8);

ISRCTN Registry (www.isrctn.com; searched April 2017) (Appendix 9);

Stroke Trials Registry (www.strokecenter.org/trials/; searched April 2017) (Appendix 10); and

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.apps.who.int/trialsearch/; searched April 2017) (Appendix 11)

Searching other resources

We used the Science Citation Index Cited Reference Search to search for studies citing included trials. We also checked the reference lists of included trials, relevant systematic reviews, and relevant meta‐analyses. We contacted authors and trialists involved in included trials to facilitate identification of ongoing trials and unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the previous version of this review, two review authors (KL and a second review author) independently assessed the titles, abstracts and keywords of all records retrieved from the electronic searches and excluded obviously irrelevant studies (Lager 2014). We resolved any disagreements regarding study eligibility by discussion among all review authors. For this search update in April 2017, two review authors (BB and AW) undertook the same process, identifying relevant studies published since the original review. A third author (PM) validated the results and edited the review. We obtained the full texts of the remaining studies and two review authors independently selected studies for inclusion based on the following criteria.

The study:

was an RCT;

restricted participants to people with TIA or stroke, or reported outcomes separately for TIA or stroke patient subgroups;

evaluated a stroke service intervention;

stated or clearly implied that the intention of an intervention was to improve modifiable risk factor control;

assessed one or more of the defined outcome measures; and

did not include physical rehabilitation programs, new pharmacological therapies, surgical procedures, exercise training programmes, or educational programmes intended to improve knowledge of stroke in general.

Data extraction and management

For the previous version of this review, two review authors independently extracted outcome data for each eligible trial using a pre‐specified data extraction form (Lager 2014). One review author extracted data for all eligible studies (KL) and a second review author (AKS and VH) independently repeated data extraction for each study. We resolved disagreements by discussion to reach consensus, with review authors referring back to the original article. For this update, this method was repeated by BB, AW and PM respectively.

We recorded the following information for each study.

General information: published or unpublished, title, authors, journal or source, publication date, country of origin, publication language.

Study methods: unit of randomisation (and method), allocation concealment (and method), blinding (outcome assessors), validation of questionnaires.

Participants: sampling (random or convenience), place of recruitment, total sample size, numbers randomised, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, demographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, socio‐economic or socio‐demographic status), disability (modified Rankin score, Barthel score), co‐morbidities, similarity between groups at baseline, dropout and withdrawal rates.

Intervention details: components, length, frequency, location, mode of delivery, personnel responsible for delivery, timing post‐stroke, details of control protocol.

Outcomes: pre‐specified outcomes (see Selection of studies), follow‐up intervals from start of intervention, units of measurement, missing data.

Results: results for pre‐specified outcomes, number of participants assessed, method of analysis (intention‐to‐treat analysis, per protocol analysis).

Intervention category: pre‐specified in the review protocol.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (KL, BB, AW) independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study, using the 'Risk of bias' tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We resolved any disagreements by discussion. We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias.

We graded the risk of bias for each domain as of high, low, or unclear risk of bias and entered this information into the 'Risk of bias' table produced for each study in the Characteristics of included studies section, along with the reason for each decision. We contacted study authors to retrieve missing information. If study authors did not provide the requested information, we recorded the relevant items on the risk of bias assessment as 'unclear'.

We summarised the risk of bias according to the following criteria (Higgins 2011a).

Low risk of bias: low risk of bias for all domains.

Unclear risk of bias: unclear risk of bias for one or more domains.

High risk of bias: high risk of bias for one or more domains.

Measures of treatment effect

A mixture of continuous outcomes and dichotomous outcomes were reported by studies included in this review. Where possible, we reported data in terms of mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for continuous data. For dichotomous data, we reported risk ratios (RR) or odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs. If individual studies reported continuous and dichotomous data for the same outcome, we included both variables in the review. We used RevMan 5 to carry out statistical analyses (RevMan 2014).

Unit of analysis issues

We analysed cluster‐RCTs by reporting effect estimates from analyses that accounted for the cluster design. Where necessary, we calculated effective sample sizes for cluster‐RCTs and combined these with parallel RCTs in meta‐analyses (Higgins 2011b). When examining recurrent events we aimed to analyse the number of people with one or more events rather than number of events. Where studies included repeated measurements for participants at several time points, we reported the outcomes recorded at the end of the study per protocol.

Dealing with missing data

We proposed to contact study authors if necessary to request any missing data and to input missing summary data (e.g. standard deviations) based on recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011; Higgins 2011b). There was an apparent inconsistency with the standard deviation values reported for MacKenzie 2013. We attempted to contact the author to clarify; however, we did not receive a response, so we used the published standard deviation values.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We identified heterogeneity from forest plots using the Chi² test and a significance level of alpha = 0.1. We also quantified heterogeneity using the I² statistic, where I² values of 50% or more indicate a substantial level of heterogeneity (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003). Where appropriate, we assessed possible sources of heterogeneity using sensitivity analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

We used funnel plots to assess publication bias.

Data synthesis

Included studies were heterogeneous in terms of interventions, settings, participant characteristics, and outcome measurements. Where there were sufficient comparable data we combined results for each outcome to give an overall estimate of treatment effect. We conducted meta‐analyses separately for each intervention category to reduce clinical heterogeneity among the studies that were combined to produce pooled estimates using random‐effects models. We pre‐specified intervention categories in the review protocol. Where meta‐analysis was not possible or appropriate, we presented results as a qualitative synthesis of intervention effects.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to analyse outcomes according to the following subgroups.

Participant age (under 65 years, 65 years and over).

Condition (ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, or TIA).

Stroke severity (e.g. according to the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)) or disability (e.g. according to the Barthel score or modified Rankin Score (mRS)).

Specific risk factor management strategy (e.g. blood pressure lowering interventions).

However, subgroup analyses were not possible because relevant data were not available from the included studies. We were, however, able to undertake subgroup analysis for studies involving multidisciplinary team members.

Sensitivity analysis

We undertook sensitivity analysis for achievement of blood pressure targets using the following criteria.

Repeating analyses excluding unpublished studies.

Repeating analyses excluding studies at high or unclear risk of bias.

Repeating analyses excluding very large studies to investigate the extent to which they dominated the results.

Repeating analyses using different measures of effect size (risk difference, odds ratio etc.) and different statistical models (fixed‐effect and random‐effects models).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used GRADEpro GDT to import data from Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014) in order to create 'Summary of findings' tables. Within these tables, we presented a summary of the evidence for educational and behavioural interventions for participants receiving treatment compared with those in the control group for secondary stroke prevention (Table 1), and organisational interventions for participants receiving treatment compared with those in the control group for secondary stroke prevention (Summary of findings table 2). We included the following outcomes: mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure, blood pressure target achievement, medication adherence, mean low density lipoprotein, mean HbA1c and mean BMI.

Summary of findings 1. Educational or behavioural interventions for patients compared to usual care for improving modifiable risk factor control in the secondary prevention of stroke.

| Educational or behavioural interventions for patients compared to usual care for improving modifiable risk factor control in the secondary prevention of stroke | |||||

|

Patient or population: The trials included a total of 33,840 participants with cerebrovascular disease. The mean or median age of participants ranged from 60 years to 74.3 years. Nine studies included participants with diagnoses of ischaemic stroke; six studies included participants with either ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke; one focused on lacunar strokes; two did not specify stroke subtype; four included participants with TIA only and 19 trials included a broader range of participants with a diagnosis of either stroke or TIA. Settings: Primary or secondary care Intervention: Educational or behavioural interventions for patients Comparison: Usual care | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) Follow up | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with usual care | Risk difference with Educational or behavioural interventions for patients | ||||

| Mean systolic blood pressure | 1398 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ‐ | The mean systolic blood pressure was 135.59 mmHg | MD 2.81 mmHg lower (7.02 lower to 1.39 higher) |

| Mean diastolic blood pressure | 1398 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ‐ | The mean diastolic blood pressure was 78.28 mmHg | MD 0.83 mmHg lower (2.8 lower to 1.13 higher) |

| Blood pressure target achievement | 266 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | OR 1.34 (0.70 to 2.59) | Study population | |

| 385 per 1000 | 71 more per 1000 (80 fewer to 234 more) | ||||

| Low | |||||

| 260 per 1000 | 60 more per 1000 (63 fewer to 216 more) | ||||

| High | |||||

| 430 per 1000 | 73 more per 1000 (84 fewer to 231 more) | ||||

| Medication adherence | 33,762 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 3 | ‐ | Most studies measuring medication adherence outcomes found no significant differences between the intervention and control groups on any indicator of adherence | |

| Mean low density lipoprotein | 495 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4 | ‐ | The mean low density lipoprotein was 2.62 mmol/L | MD 0.13 mmol/L lower (0.28 lower to 0.02 higher) |

| Mean HbA1c | 70 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4 5 | ‐ | The mean HbA1c was 5.98 | MD 0.11 lower (0.39 lower to 0.17 higher) |

| Mean BMI | 127 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4 | ‐ | The mean BMI was 24.01 kg/m² | MD 0.22 kg/m² higher (0.85 lower to 1.29 higher) |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 The methods used in these studies were heterogenous which made these difficult to directly correlate

2 Contains at least one study that scores 'high' using the Cochrane risk analysis and thus down graded by one level

3 Results were inconsistent across the studies

4 Secondary outcome

5 One study provided evidence for this outcome

We justified judgements about the quality of the evidence (high, moderate, low, or very low) according to the GRADE approach (Higgins 2011c), which we documented and incorporated into the reporting of results for each outcome. The quality of evidence could be downgraded by one level (serious concern) or two levels (very serious concerns) due to concerns raised within: risk of bias; inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity, inconsistency of results); indirectness (indirect population, intervention, control, outcomes) and due to imprecision (wide CIs, single trials). Grade outcomes are presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables (Table 1; Table 2).

Summary of findings 2. Organisational interventions compared to usual care for improving modifiable risk factor control in the secondary prevention of stroke.

| Organisational interventions compared to usual care for improving modifiable risk factor control in the secondary prevention of stroke | |||||

|

Patient or population: The trials included a total of 33,840 participants with cerebrovascular disease. The mean or median age of participants ranged from 60 years to 74.3 years. Nine studies included participants with diagnoses of ischaemic stroke; six studies included participants with either ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke; one focused on lacunar strokes; two did not specify stroke subtype; four included participants with TIA only and 19 trials included a broader range of participants with a diagnosis of either stroke or TIA. Settings: Primary or secondary care Intervention: Organisational derived interventions Comparison: Usual care | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) Follow up | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with usual care | Risk difference with Organisational interventions | ||||

| Mean systolic blood pressure | 17,490 (16 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE2 | ‐ | The mean mean systolic blood pressure was 133.85 mmHg | MD 1.58 mmHg lower (‐4.66 lower to 1.51 higher) |

| Mean diastolic blood pressure | 17,178 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE2 | ‐ | The mean mean diastolic blood pressure was 75.12 mmHg | MD 0.91 mmHg lower (‐2.75 lower to 0.93 higher) |

| Blood pressure target achievement | 23,631 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE2 | OR 1.44 (1.09 to 1.90) | Study population | |

| 391 per 1000 | 89 more per 1000 (21 more to 159 more) | ||||

| Low | |||||

| 220 per 1000 | 69 more per 1000 (15 more to 129 more) | ||||

| High | |||||

| 800 per 1000 | 52 more per 1000 (13 more to 84 more) | ||||

Sensitivity analysis

| |||||

| Medication adherence | 5384 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 3 | ‐ | Most studies measuring medication adherence outcomes found no significant differences between the intervention and control groups on any indicator of adherence | |

| Mean low density lipoprotein | 1008 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4 | ‐ | The mean mean low density lipoprotein was 2.60 mmol/L | MD 0.21 mmol/L lower (‐0.31 to ‐0.11) |

| Mean HbA1C | 554 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | ‐ | The mean mean HbA1c was 5.71 | MD 0.2 lower (‐0.98 to 0.59) |

| Mean BMI | 1089 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | ‐ | The mean mean BMI was 27.89 kg/m² | MD 0.47 kg/m² lower (‐1.24 to 0.30) |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 One included study did not include an explanation of blinding

2 The methods and outcome measures used in these studies were heterogenous which made these difficult to directly correlate

3 One study deemed high risk when assessed using Cochrane risk of bias tool Contains at least one study thus down graded by one level

4 The methods used in these studies were heterogenous which made these difficult to directly correlate

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies

Results of the search

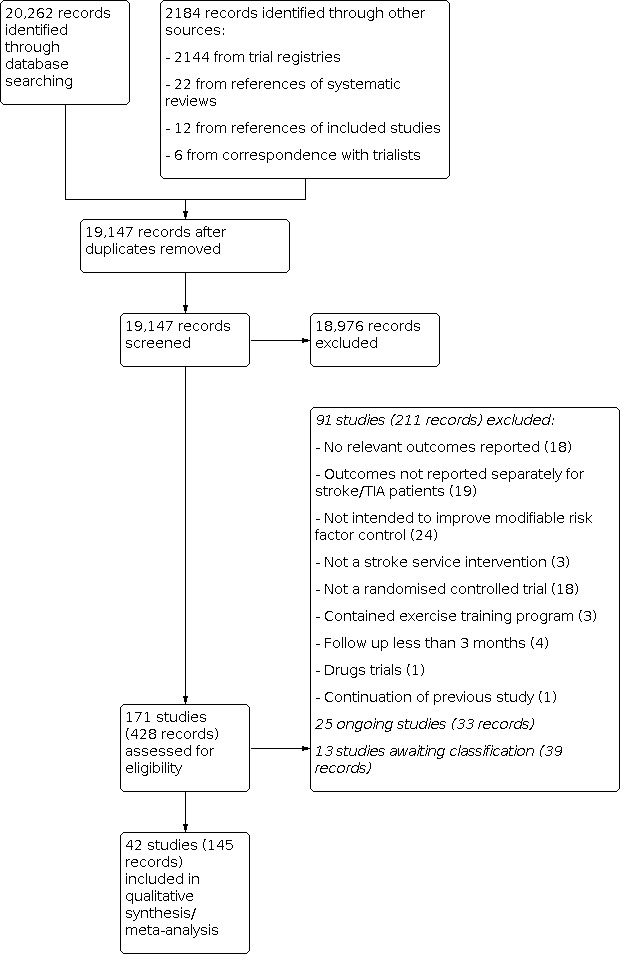

We carried out searches in April 2013 and updated the search in April 2017 and identified a total of 19,147 records after the removal of duplicates (Figure 1). Title and abstract screening identified 171 studies (82 in the first review (Lager 2014) and 89 in this update, consisting of 428 records collectively) that were potentially eligible for this review.

1.

Study flow diagram.

We found 10 potentially eligible studies that reported collective outcome data for participants with a broad range of cardiovascular diseases (Amariles 2012; Brotons 2011; Evans 2010; Goessens 2006; Ma 2009; McManus 2014; Palanco 2011; Spassova 2016; Strandberg 2006; Vernooij 2012). We contacted study authors to request outcome data separately for participants with stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA). We received responses from four study authors who provided unpublished outcome data for participants with stroke and TIA; these studies were included in the review (Brotons 2011; Evans 2010; Jönsson 2014; McManus 2014). The authors of one study reported that separate outcome data for participants with stroke and TIA were unavailable (Vernooij 2012). The authors of six studies did not respond to requests for additional data and these studies were excluded from the review (Amariles 2012; Goessens 2006; Ma 2009; Palanco 2011; Spassova 2016; Strandberg 2006).

We identified a further 47 studies of potential relevance to this review, if unpublished outcome data were available. We therefore attempted to obtain information about these studies by emailing the main study contacts. Seven authors supplied unpublished data, for example blood pressure or body mass index (BMI). We included these studies in the review (Eames 2013; Flemming 2013; Lowrie 2010; Jönsson 2014; McManus 2014; O'Carroll 2011; Slark 2013).

Included studies

We added 16 new studies (25,819 participants), to the 26 studies (8021 participants) in the previous version of the review, resulting in a total of 42 studies including 33,840 participants in this update. Of these 36 used a parallel group design (Adie 2010; Allen 2002; Allen 2009; MIST 2014; Boter 2004; Boysen 2009; Chanruengvanich 2006; Chiu 2008; Damush 2015; Eames 2013; Ellis 2005; Evans 2010; Flemming 2013; Hanley 2015; Hedegaard 2014; Hornnes 2011; Nailed Stroke 2010; Jönsson 2014; Joubert 2009; Kerry 2013; Kim 2013; Kono 2013; Kronish 2014; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; MacKenzie 2013; Markle‐Reid 2011; Mant 2016; McAlister 2014; McManus 2014; O'Carroll 2011; Pergola 2014; Slark 2013; Wan 2016; Wang 2005; Welin 2010) and six used a cluster design (Brotons 2011; Dregan 2014; Johnston 2010; Lowrie 2010; Ranta 2015; Peng 2014). Visual inspection of funnel plots to detect possible reporting bias suggested no asymmetry. Detailed information on each study is provided in Characteristics of included studies.

Participants

The trials included a total of 33,840 participants with cerebrovascular disease. The mean or median age of participants ranged from 60 years to 74.3 years. Nine studies included participants with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke (Allen 2009; Boysen 2009; Chiu 2008; Hedegaard 2014; Johnston 2010; Kim 2013; Kono 2013; Slark 2013; Wan 2016), whereas six studies included participants with either ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke (MIST 2014; Dregan 2014; Jönsson 2014; Lowe 2007; Lowe 2007; Welin 2010), one focused on lacunar strokes (Pergola 2014) and two did not specify stroke subtype (McManus 2014; Wang 2005). Nineteen trials included a broader range of participants with a diagnosis of either stroke or TIA (Allen 2002; Boter 2004; Damush 2015; Eames 2013; Ellis 2005; Flemming 2013; Hanley 2015; Hornnes 2011; Nailed Stroke 2010; Joubert 2009; Kronish 2014; MacKenzie 2013; McManus 2014; Mant 2016; Markle‐Reid 2011; McAlister 2014; O'Carroll 2011; Peng 2014; Ranta 2015). The proportion of TIA participants ranged from 1% (Eames 2013) to 46% (Flemming 2013). Four studies focused only on individuals with minor stroke or TIA (Adie 2010; Chanruengvanich 2006; Kerry 2013; Maasland 2007). Other studies included participants with a history of cardiovascular disease or elevated cardiovascular risk factors, and provided separate unpublished data for stroke and TIA participants (Brotons 2011; Evans 2010; Lowrie 2010).

Location

Seven included trials were conducted in the USA (Allen 2002; Allen 2009; Damush 2015; Flemming 2013; Johnston 2010; Kronish 2014; Pergola 2014), four in Canada (Evans 2010; McAlister 2014; MacKenzie 2013; Markle‐Reid 2011), nine in the UK (Adie 2010; Dregan 2014; Ellis 2005; Hanley 2015; Lowe 2007; Lowrie 2010; Mant 2016; McManus 2014; O'Carroll 2011), 10 in other European countries (Boter 2004; Brotons 2011; Hedegaard 2014; Hornnes 2011; Nailed Stroke 2010; Jönsson 2014; Kerry 2013; Maasland 2007; Slark 2013; Welin 2010), four in Australasia (MIST 2014; Eames 2013; Joubert 2009; Ranta 2015), and seven in Asia (Chanruengvanich 2006; Chiu 2008; Kim 2013; Kono 2013; Peng 2014; Wan 2016; Wang 2005). One study was a multicentre trial conducted in five centres in China and Europe (Boysen 2009).

Setting

Most studies were set in primary care or community settings (Adie 2010; Allen 2002; Allen 2009; Boter 2004; Boysen 2009; Brotons 2011; Chanruengvanich 2006; Dregan 2014; Evans 2010; Hanley 2015; Hornnes 2011; Nailed Stroke 2010; Kerry 2013; Kim 2013; Kono 2013; Kronish 2014; MacKenzie 2013; Mant 2016; Markle‐Reid 2011; McManus 2014; O'Carroll 2011; Pergola 2014; Ranta 2015; Wan 2016; Wang 2005). Seven studies were set in outpatient clinics (Chiu 2008; Damush 2015; Ellis 2005; Flemming 2013; Hedegaard 2014; Jönsson 2014; Welin 2010). One study was incorporated into a TIA service that provided screening and diagnostic work‐up in a single day (Maasland 2007). One study was based at a stroke prevention centre (McAlister 2014), and another at a veterans' medical centre (Damush 2015). A further two interventions were performed during hospitalisation for acute stroke (Johnston 2010; Slark 2013). Five studies were initiated in the hospital setting (Eames 2013; Joubert 2009; Lowe 2007) with two subsequently continuing the intervention in the community (Eames 2013; Joubert 2009) and one was undertaken either in a hospital (if the participant was still an inpatient), or in the community if discharged (MIST 2014).

Interventions

See Characteristics of included studies for details of interventions (components, length, frequency).

Intervention categories

To facilitate analysis and interpretation of study results, we described interventions according to categories pre‐specified in the review protocol (educational and behavioural interventions for patients; educational and behavioural interventions for healthcare providers; organisational interventions as defined according to the taxonomy developed by Wensing 2006). Most interventions were multifaceted and contained components that were associated with more than one category, for example studies included organisational elements with varying amounts of education (directed for patients or healthcare professionals). However, to summarise evidence effectively, we categorised interventions according to their predominant components. For example, if organisational elements were considered to have facilitated or permitted the delivery of education (e.g. patient education is often a component of multidisciplinary team services (Wensing 2006)) these were classified as organisational. We decided final category assignments by discussion among review authors to reach consensus.

Sixteen studies included educational or behavioural interventions for participants. Nineteen studies included multidisciplinary team services where patient care was delivered according to protocols for screening, education, and treatment or monitoring. Fourteen studies included educational or behavioural interventions for healthcare providers, which usually involved the provision of guidelines or specification of individual patient targets. Less common intervention elements included revision of professional roles (changes in the tasks carried out by pharmacists), collaboration among multidisciplinary teams, knowledge management systems, and quality management. No studies included financial interventions. Just under half of the studies included multidisciplinary teams where patient care was delivered according to protocols for screening, education, and treatment or monitoring. After review and discussion, we agreed that the interventions were categorised predominately as educational or behavioural interventions for patients and organisational interventions. Predominant intervention categories are highlighted in Table 3.

1. Intervention categories.

| Study | Educational/behavioural interventions for patients | Educational/behavioural interventions for service providers | Organisational interventions |

Predominant intervention category |

|||||

| Revision of professional roles | Collaboration between multidisciplinary teams | Integrated care services | Knowledge management systems | Quality management | Financial incentives | ||||

| Allen 2002 | X | X | X | X | Organisational | ||||

| Allen 2009 | X | X | X | X | Organisational | ||||

| Boter 2004 | X | X | Organisational | ||||||

| Brotons 2011 | X | X | X | Organisational | |||||

| Damush 2015 | X | X | Organisational | ||||||

| Dregan 2014 | X | X | Organisational | ||||||

| Ellis 2005 | X | X | Organisational | ||||||

| Evans 2010 | X | X | X | Organisational | |||||

| Flemming 2013 | X | X | X | X | X | Organisational | |||

| Hanley 2015 | X | X | X | Organisational | |||||

| Hedegaard 2014 | X | X | X | Organisational | |||||

| Hornnes 2011 | X | X | Organisational | ||||||

| Nailed Stroke 2010 | X | X | X | X | Organisational | ||||

| Johnston 2010 | X | X | Organisational | ||||||

| Jönsson 2014 | X | X | X | X | Organisational | ||||

| Joubert 2009 | X | X | X | X | X | Organisational | |||

| Kerry 2013 | X | X | Organisational | ||||||

| Lowrie 2010 | X | X | Organisational | ||||||

| Mant 2016 | X | X | Organisational | ||||||

| Markle‐Reid 2011 | X | X | X | X | Organisational | ||||

| McAlister 2014 | X | X | X | X | X | Organisational | |||

| McManus 2014 | X | X | X | Organisational | |||||

| Pergola 2014 | X | Organisational | |||||||

| Ranta 2015 | X | X | Organisational | ||||||

| Wang 2005 | X | X | Organisational | ||||||

| Welin 2010 | X | X | Organisational | ||||||

| Adie 2010 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| MIST 2014 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| Boysen 2009 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| Chanruengvanich 2006 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| Chiu 2008 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| Eames 2013 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| Kim 2013 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| Kono 2013 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| Kronish 2014 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| Lowe 2007 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| Maasland 2007 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| MacKenzie 2013 | X | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | ||||||

| O'Carroll 2011 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| Peng 2014 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| Slark 2013 | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | |||||||

| Wan 2016 | X | X | Educational/behavioural intervention for patients | ||||||

Educational or behavioural interventions for patients

Sixteen studies involved educational and behavioural interventions for participants (Adie 2010; Boysen 2009; Chanruengvanich 2006; Chiu 2008; Eames 2013; Kim 2013; Kono 2013; Kronish 2014; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; MacKenzie 2013; MIST 2014; O'Carroll 2011; Peng 2014; Slark 2013; Wan 2016). None of the interventions investigated by these studies incorporated organisational elements.

The content of 11 studies was largely focused on modifiable risk factors for stroke (Adie 2010; MIST 2014; Boysen 2009; Chanruengvanich 2006; Chiu 2008; Kim 2013; Kono 2013; Maasland 2007; MacKenzie 2013; O'Carroll 2011; Slark 2013). Five interventions delivered education about secondary stroke prevention as part of broader stroke education programmes (Eames 2013; Kronish 2014; Lowe 2007; Peng 2014; Wan 2016).

Organisational interventions

We included 26 studies that involved predominantly organisational interventions (Allen 2002; Allen 2009; Boter 2004; Brotons 2011; Damush 2015; Dregan 2014; Ellis 2005; Evans 2010; Flemming 2013; Hanley 2015; Hedegaard 2014; Hornnes 2011; Nailed Stroke 2010; Johnston 2010; Jönsson 2014; Joubert 2009; Kerry 2013; Lowrie 2010; Mant 2016; Markle‐Reid 2011; McAlister 2014; McManus 2014; Pergola 2014; Ranta 2015; Wang 2005; Welin 2010). Seven interventions addressed secondary stroke prevention as part of a wider set of study aims encompassing post‐stroke rehabilitation (interventions with a broad focus) (Allen 2002; Allen 2009; Boter 2004; Damush 2015; Jönsson 2014; Markle‐Reid 2011; Welin 2010). Although these organisational interventions generally provided some patient education about secondary stroke prevention, this appeared to be delivered on only one occasion (Allen 2002; Allen 2009) or on an opportunistic basis (Boter 2004; Welin 2010). Conversely, secondary prevention was the main aim of the remaining 18 organisational interventions (interventions specifically targeting secondary prevention). Nine of these interventions included an element of patient education or behavioural counselling directed towards secondary stroke prevention (Brotons 2011; Ellis 2005; Evans 2010; Flemming 2013; Hornnes 2011; Joubert 2009; Kerry 2013; McAlister 2014; Wang 2005). Three studies did not specify the inclusion of patient education elements but directed secondary prevention education for healthcare professionals (Johnston 2010; Kronish 2014; Lowrie 2010).

Control comparators

Usual care, described as standard care provided by the managing medical team without any enhancement, was used as the control comparator in 30 studies (Adie 2010; Allen 2002; Allen 2009; Boter 2004; Brotons 2011; Chanruengvanich 2006; Chiu 2008; Eames 2013; Ellis 2005; Flemming 2013; Hanley 2015; Hedegaard 2014; Hornnes 2011; Johnston 2010; Jönsson 2014; Joubert 2009; Kerry 2013; Kim 2013; Kono 2013; Lowrie 2010; MacKenzie 2013; Markle‐Reid 2011; McManus 2014; MIST 2014; Nailed Stroke 2010; Peng 2014; Ranta 2015; Slark 2013; Wang 2005; Welin 2010).

Seven studies provided control participants with the same initial information and educational advice as the intervention group, without any individualised advice (Boysen 2009; Damush 2015; Evans 2010; Kronish 2014; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; Wan 2016 ).

Dregan 2014 reminded practices in the control group to record all stroke‐related consultations and adverse events.

An active control group was used in four studies. Control group participants in O'Carroll 2011 received visits from a research fellow, where a generalised, non medication‐related discussion was provided. McAlister 2014 used a nurse‐led management control group. Mant 2016 randomised participants into either an intensive blood pressure target (< 130 mmHg or a 10 mmHg reduction if baseline pressure was < 140 mm Hg) (active group) or a standard target (< 140 mmHg) (control arm). Pergola 2014 used a similar model whereby patients with recent symptomatic lacunar stroke were randomised to one of two levels of systolic BP (SBP) targets: lower: < 130 mmHg (intervention group), or higher: 130 to 149 mmHg (control group).

Timing

We included 24 studies that recruited participants immediately following diagnosis of an acute stoke or TIA. These studies initiated interventions following symptoms of an event (Ranta 2015), before hospital discharge (Eames 2013; Hedegaard 2014; Johnston 2010; Joubert 2009; Lowe 2007; MacKenzie 2013; Maasland 2007; Slark 2013), within one week post‐discharge (Allen 2002; Allen 2009; Boter 2004; Wang 2005), within one month post‐discharge (Adie 2010; MIST 2014; Nailed Stroke 2010; Wan 2016), within three months post‐discharge (Boysen 2009; Chanruengvanich 2006; Ellis 2005; Flemming 2013; Jönsson 2014; O'Carroll 2011; Welin 2010), or within 12 months post‐discharge (Damush 2015). Twelve studies recruited participants from primary care, outpatient or community settings, within three months (Hanley 2015; Kono 2013; Peng 2014; Ranta 2015), six months (Pergola 2014), nine months (Kerry 2013), 12 months (Brotons 2011; Kim 2013; McAlister 2014), 18 months (Markle‐Reid 2011), up to five years (Kronish 2014) post stroke or TIA diagnosis; or ever had a stroke or TIA (Dregan 2014). One study initiated the intervention when participants had been attending an outpatient clinic for at least 12 months (Chiu 2008). Four studies did not specify intervention timing (Evans 2010; Lowrie 2010; Mant 2016; McManus 2014).

Five studies involved interventions that were delivered on a single occasion (Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; Ranta 2015; Slark 2013) or on two occasions (O'Carroll 2011). The remaining studies implemented interventions over a time frame ranging from three months to 36 months. Most interventions studied by trials had durations of between three months and 12 months.

Outcomes

Details of outcomes are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Funding sources

Sources of funding were reported by 38 studies (90%). Most studies were either funded by charities (45%) or government sources (24%). Other funding sources included universities, fellowships, industry, and the NHS. Three studies had multiple funding sources and two did not receive any funding.

Excluded studies

We excluded eight studies that did not report separately on TIA and stroke participants (Amariles 2012; Goessens 2006; Joshi 2012; Ma 2009; Palanco 2011; Spassova 2016; Strandberg 2006; Vernooij 2012); six with no relevant outcomes (Banet 1997; Bokemark 1996; Gillham 2010; Green 2007; Middleton 2004; Nir 2006); three did not present a stroke service intervention (FIMDM_CVD 2010; Johnston 2000; Ornstein 2004); two were not intended to improve modifiable risk factor control (Harrington 2007; Ross 2007), two contained an exercise training program (Rimmer 2000; UMIN000001865) and one was not a RCT (Sides 2012). We will consider these studies for inclusion in a future update. We have provided a summary in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Studies awaiting classification

There were 13 completed trials for which further study information was unavailable (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

Ongoing studies

We identified 24 eligible studies: 17 were currently recruiting, 2 were not yet recruiting, 3 were classified as ongoing, 1 was active but not recruiting, and one was unknown (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias according to Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias. We extracted information about methods of randomisation and allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and any other potential sources of bias for each included study. We assessed three studies at high risk of bias; the remainder were considered to have a low risk of bias. Detailed assessments of risk of bias for each study is presented in Characteristics of included studies. Summary assessments are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item from each study

Allocation

Inclusion criteria for this review required studies to be randomised. All but four studies reported adequate generation of allocation sequence. Two studies were reported as RCTs but did not provide details of randomisation methods (Chanruengvanich 2006; Chiu 2008). Wang 2005 reported that participants were "randomly divided into intervention group (146 cases) and control group (52 cases)". Although the use of randomised methods can be inferred from this statement, the large imbalances in group size were not explained and this included study was considered at high risk of bias. In the study by Jönsson 2014, allocation was undertaken by an administration secretary using lists made by a second study author. Although computer randomisation was used initially, it was deemed that there was high potential for possible bias (Jönsson 2014).

Criteria for adequate allocation concealment were met by all but eight studies. Three trials that did not report randomisation methods also provided insufficient information about allocation concealment (Chanruengvanich 2006; Chiu 2008; Wang 2005). Another five studies with adequate sequence generation contained no information about allocation concealment (Allen 2002; Kim 2013; Mant 2016; Peng 2014; Pergola 2014).

Blinding

We found that 14 studies reported blinding of outcome assessors for all outcomes (Allen 2009; Boter 2004; Boysen 2009; Chanruengvanich 2006; Eames 2013; Ellis 2005; Hanley 2015; Hedegaard 2014; Hornnes 2011; Kerry 2013; Kronish 2014; Markle‐Reid 2011; MIST 2014; Wan 2016). A further three studies reported blinding during assessment of selected outcomes (Allen 2002; Johnston 2010; Welin 2010). There were 25 studies for which at least some data were collected by unblinded outcome assessors (Adie 2010; Allen 2002; Brotons 2011; Chiu 2008; Damush 2015; Dregan 2014; Evans 2010; Flemming 2013; Nailed Stroke 2010; Jönsson 2014; Joubert 2009; Kim 2013; Kono 2013; Lowrie 2010; Maasland 2007; MacKenzie 2013; Mant 2016; McAlister 2014; McManus 2014; O'Carroll 2011; Peng 2014; Pergola 2014; Ranta 2015; Slark 2013; Wang 2005). Following consideration of these 25 studies, we judged that non‐blinding of outcome assessors was unlikely to affect the measurement of objective outcomes such as physiological data (e.g. blood pressure), information extracted from medical records, or information measured using validated questionnaires. However, it was unclear whether non‐blinding could have affected outcomes obtained from participants via self‐reporting (e.g. adherence to medication and self‐reported cardiovascular events) (Flemming 2013; Joubert 2009; Kim 2013; Maasland 2007; MacKenzie 2013; MIST 2014; Slark 2013).

Incomplete outcome data

The proportion of study participants completing follow‐up ranged from 70% (Brotons 2011) to 100% (Adie 2010; MacKenzie 2013). Two studies did not report the proportion of participants who completed follow‐up (Chiu 2008; Wang 2005). In Lowrie 2010, information was only available for those participants with baseline and follow‐up data. No missing outcome data were reported for three studies (Adie 2010; MacKenzie 2013; Ranta 2015). We found that 27 studies reported reasons for missing outcome data and we judged these were unlikely to be related to the study outcomes (Boter 2004; Boysen 2009; Brotons 2011; Chanruengvanich 2006; Dregan 2014; Eames 2013; Ellis 2005; Evans 2010; Flemming 2013; Hornnes 2011; Johnston 2010; Kerry 2013; Kim 2013; Kronish 2014; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; MacKenzie 2013; Mant 2016; Markle‐Reid 2011; McAlister 2014; McManus 2014; MIST 2014; O'Carroll 2011; Ranta 2015; Slark 2013; Wan 2016; Welin 2010). The 13 remaining studies did not provide enough information about missing outcome data to permit judgement (Allen 2002; Allen 2009; Chiu 2008; Damush 2015; Hanley 2015; Hedegaard 2014; Nailed Stroke 2010; Joubert 2009; Kono 2013; Lowrie 2010; Peng 2014; Pergola 2014; Wang 2005).

Selective reporting

Protocols were available for 41 studies, and 31 appeared to be free of selective outcome reporting (Adie 2010; Allen 2009; MIST 2014; Boter 2004; Boysen 2009; Brotons 2011; Chanruengvanich 2006; Dregan 2014; Eames 2013; Evans 2010; Flemming 2013; Hanley 2015; Hedegaard 2014; Hornnes 2011; Nailed Stroke 2010; Jönsson 2014; Kerry 2013; Kono 2013; Lowrie 2010; Maasland 2007; MacKenzie 2013; Mant 2016; McAlister 2014; McManus 2014; O'Carroll 2011; Peng 2014; Pergola 2014; Ranta 2015; Slark 2013; Wan 2016; Welin 2010). Johnston 2010 reported primary outcomes as pre‐specified, although some secondary outcomes were not reported.

Other potential sources of bias

It was unclear in some studies if recurrent events were presented as number of events rather than number of people with one or more event (Kono 2013; McAlister 2014; Nailed Stroke 2010; Peng 2014).

Effects of interventions

Target achievement of mean reductions, or both

Blood pressure

We included 30 studies that reported data on differences in mean systolic or diastolic blood pressure, or both, including where blood pressure target was achieved. Of these, 10 studies evaluated educational or behavioural interventions for participants (Adie 2010; Chanruengvanich 2006; Chiu 2008; Kono 2013; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; MacKenzie 2013; MIST 2014; O'Carroll 2011; Slark 2013) and 20 evaluated organisational interventions (Allen 2002; Allen 2009; Brotons 2011; Dregan 2014; Ellis 2005; Evans 2010; Flemming 2013; Hanley 2015; Hornnes 2011; Nailed Stroke 2010; Johnston 2010; Jönsson 2014; Joubert 2009; Kerry 2013; Mant 2016; McAlister 2014; McManus 2014; Pergola 2014; Wang 2005; Welin 2010).

Educational and behavioural interventions for patients

Pooled data from 11 studies (Adie 2010; Chanruengvanich 2006; Chiu 2008; Kono 2013; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; MacKenzie 2013; Mant 2016; MIST 2014; O'Carroll 2011; Slark 2013; N = 1398) indicated that educational and behavioural interventions for participants were not associated with significant changes in mean systolic blood pressure (MD ‐2.81, 95% CI ‐7.02 to 1.39; Analysis 1.1) or mean diastolic blood pressure (MD ‐0.83, 95% CI ‐2.80 to 1.13; Analysis 1.2). However, the analyses included one large study that was independently associated with reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Chiu 2008, N = 160) (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2). Chiu 2008 reported outcome data only for a subgroup of participants with hypertension, so baseline blood pressure levels were higher and therefore easier to improve upon. Kono 2013, a smaller study that involved 70 participants, was associated with a significant reduction in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure within home and clinic readings. The pooled results were associated with a substantial level of statistical heterogeneity (I² = 79%). When Chiu 2008 was removed from the analyses, pooled data from the remaining 10 studies did not indicate any intervention effects and statistical heterogeneity was reduced (I² = 72%). The three studies that reported data on achieving blood pressure targets (< 140/90 mmHg or < 130/80 mmHg) indicated that educational and behavioural interventions for patients were not associated with a significant change in the proportion of participants who attained adequate blood pressure control (Adie 2010; Chiu 2008; MacKenzie 2013) (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.44; N = 266; Analysis 1.3; moderate‐quality evidence).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational or behavioural interventions for patients versus usual care, Outcome 1: Mean systolic blood pressure

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational or behavioural interventions for patients versus usual care, Outcome 2: Mean diastolic blood pressure

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational or behavioural interventions for patients versus usual care, Outcome 3: Blood pressure target achievement

Organisational interventions

Pooled data from 16 studies indicated that organisational interventions were associated with a non‐statistically significant reduction in mean systolic blood pressure reduction (MD ‐1.58, 95% CI ‐4.66 to 1.51; N = 17,490; Analysis 2.1) (Brotons 2011; Dregan 2014; Ellis 2005; Evans 2010; Flemming 2013; Hanley 2015; Hornnes 2011; Nailed Stroke 2010; Jönsson 2014; Joubert 2009; Kerry 2013; Mant 2016; McAlister 2014; McManus 2014; Pergola 2014; Welin 2010) (Figure 4; Table 2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Organisational interventions versus usual care, Outcome 1: Mean systolic blood pressure

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Organisational interventions versus usual care, outcome: 2.1 Mean systolic blood pressure.

Pooled data from 14 studies indicated that organisational interventions were also associated with a non‐statistically significant reduction in mean diastolic blood pressure reduction (MD ‐0.91, 95% CI ‐2.75 to 0.93; N = 17,178; Analysis 2.2) (Brotons 2011; Dregan 2014; Ellis 2005; Evans 2010; Hanley 2015; Hornnes 2011; Nailed Stroke 2010; Jönsson 2014; Joubert 2009; Kerry 2013; Mant 2016; McManus 2014; Pergola 2014; Welin 2010) (Figure 5; Table 2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Organisational interventions versus usual care, Outcome 2: Mean diastolic blood pressure

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Organisational interventions versus usual care, outcome: 2.2 Mean diastolic blood pressure.

The five studies that were associated with the greatest reductions in mean systolic blood pressure (values ranged from ‐3.10 mmHg to ‐12.09 mmHg) combined multidisciplinary team approaches with comprehensive patient education (involving promotion and tracking of adherence to medications and healthy lifestyle behaviours for secondary stroke prevention). These studies focused specifically on secondary stroke prevention and involved regular patient appointments (with a nurse, pharmacist or general practitioner (GP)) and review of multiple stroke risk factors (by a nurse case manager) (Ellis 2005; Flemming 2013; Nailed Stroke 2010; Joubert 2009; Pergola 2014). Nurse case managers informed participants (Ellis 2005; Nailed Stroke 2010) or their GPs (Flemming 2013; Joubert 2009; Pergola 2014) if risk factors deviated from recommended targets (although nurses themselves did not influence medication prescribing).

Consideration of other studies included in the meta‐analysis of systolic blood pressure data showed that most interventions were not focused specifically on secondary stroke prevention due to wider study aims (Allen 2002; Welin 2010) or the inclusion of participants with a range of other cardiovascular diseases (Brotons 2011; Evans 2010). Six studies that focused specifically on secondary stroke prevention had a more narrow objective; these largely considered blood pressure control rather than multiple risk factor reduction (Hanley 2015; Hornnes 2011; Kerry 2013; Mant 2016; McManus 2014; Pergola 2014).

Thirteen studies evaluating organisational interventions reported data on achievement of blood pressure targets (Allen 2009; Brotons 2011; Dregan 2014; Flemming 2013; Hanley 2015; Hornnes 2011; Nailed Stroke 2010; Johnston 2010; Jönsson 2014; Joubert 2009; McAlister 2014; Pergola 2014; Wang 2005). Targets varied by study and according to participant co‐morbidities; most studies specified a blood pressure target of ≤ 140/90 mmHg or ≤ 130/80 mmHg for participants with diabetes. Some studies defined alternative blood pressure targets unrelated to co‐morbidities of systolic values between 130 mmHg and 140 mmHg and diastolic values of 70 mmHg to 90 mmHg. Pergola 2014 allocated participants to achieve a systolic blood pressure target of either < 130 mmHg or 130 to 149 mmHg. Pooled data indicated that organisational interventions were associated with a significant increase in the proportion of participants who attained blood pressure targets (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.92; N = 23,631; P = 0.01; Analysis 2.3; Figure 6; Table 2). Sensitivity analysis was undertaken for target blood pressure. A statistically significant result was observed for all results (Table 2).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Organisational interventions versus usual care, Outcome 3: Blood pressure target achievement

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Organisational interventions versus usual care, outcome: 2.3 Blood pressure target achievement.

Seven studies reported involving multidisciplinary team members that included nurses, pharmacists able to prescribe, stroke specialist, care co‐ordinator, GP, and a neurologist (Allen 2009; Flemming 2013; Hornnes 2011; Nailed Stroke 2010; Jönsson 2014; Joubert 2009; McAlister 2014). Sensitivity analysis of this subgroup revealed a significant effect of involving multidisciplinary team members on target achievement (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.62; P = 0.04). Heterogeneity was moderate (I² = 26%). A further subgroup analysis of nurse led care again identified a significant effect (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.09 to1.78; P = 0.008) with little difference in heterogeneity (I² = 15%) (Allen 2002; Flemming 2013; Hornnes 2011; Nailed Stroke 2010; Jönsson 2014; McAlister 2014). McAlister 2014 involved pharmacists who were able to prescribe. This group showed a significant percentage of participants who achieved the targets for blood pressure and LDL cholesterol. Multivariate analyses confirmed there was greater attainment of the guideline‐recommended targets in the pharmacist‐led group compared with the nurse‐led group (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.06 to 4.23; P = 0.03). It is noted that no control group comparison was made.

Total cholesterol

We included 17 studies that reported cholesterol data, of which seven included educational and behavioural interventions for patients (Adie 2010; Chanruengvanich 2006; Chiu 2008; Kim 2013; Maasland 2007; MIST 2014; Slark 2013) and 10 included predominantly organisational interventions (Allen 2002; Brotons 2011; Dregan 2014; Ellis 2005; Evans 2010; Jönsson 2014; Joubert 2009; Lowrie 2010; McAlister 2014; Wang 2005).

Educational and behavioural interventions for patients

Pooled data from seven studies indicated that educational and behavioural interventions for patients were not associated with changes in mean total cholesterol levels (MD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.47; N = 721; Analysis 1.4) (Adie 2010; Chanruengvanich 2006; Chiu 2008; Kim 2013; Maasland 2007; MIST 2014; Slark 2013). Only Adie 2010 reported achievement of total cholesterol targets (total cholesterol ≤ 4 mmol/L) and found no significant difference between the intervention and control groups (OR 1.78, 95% CI 0.60 to 5.30; N = 56; Analysis 1.5).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational or behavioural interventions for patients versus usual care, Outcome 4: Mean total cholesterol

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational or behavioural interventions for patients versus usual care, Outcome 5: Total cholesterol target achievement

Organisational interventions

Organisational interventions were not associated with changes in mean total cholesterol levels (Brotons 2011; Dregan 2014; Ellis 2005; Evans 2010; Joubert 2009; Lowrie 2010; McAlister 2014) (MD ‐0.00, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.03; N = 11,955; Analysis 2.4). Pooled data from six studies indicated that organisational interventions were also associated with changes in the achievement of total cholesterol targets, although the substantial level of statistical heterogeneity observed in this analysis meant that results should be interpreted with caution (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.17; N = 12,539; I² = 80%; Analysis 2.5) (Allen 2009; Dregan 2014; Jönsson 2014; Joubert 2009; Lowrie 2010; Wang 2005). It should be noted that in this meta‐analysis we considered the outlying study with the largest effect size to be at high risk of bias due to concerns about the adequacy of the randomisation procedures (Wang 2005). Furthermore, the authors of this trial did not specify risk factor targets, stating instead that the results of blood fat tests were either classified as qualified or disqualified. When we removed this study from the meta‐analysis, there were no changes in the achievement of total cholesterol targets (varying from < 4.0 to < 5.0 mmol/L) when we pooled the data from the remaining five studies, and statistical heterogeneity was absent (I² = 0%).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Organisational interventions versus usual care, Outcome 4: Mean total cholesterol

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Organisational interventions versus usual care, Outcome 5: Total cholesterol target achievement

Low density lipoprotein (LDL)

We included 11 studies that reported LDL data, of which four evaluated educational and behavioural interventions for patients (Chiu 2008; Kono 2013; Maasland 2007; MIST 2014) and seven evaluated organisational interventions (Brotons 2011; Evans 2010; Flemming 2013; Nailed Stroke 2010; Jönsson 2014; Kronish 2014; McAlister 2014).

Educational and behavioural interventions for patients

Pooled data from four studies indicated that educational and behavioural interventions for patients were not associated with changes in mean LDL levels (Table 1) (Chiu 2008; Kono 2013; Maasland 2007; MIST 2014). A low level of statistical heterogeneity was observed (MD ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.02; N = 495; I² = 12%; Analysis 1.6). Chiu 2008 reported improvements in LDL levels (MD ‐0.13 mmol/L; 95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.02; P = 0.1). Data, however, were only presented for a subgroup of participants with hypercholesterolaemia (i.e. those with the greatest potential for improvement). Maasland 2007 reported significant reductions in LDL for both the intervention and control groups, with no significant differences between the groups. Only Chiu 2008 presented data on the achievement of LDL targets (LDL < 2.6 mmol/L or, if LDL was not available, total cholesterol < 4.1 mmol/L) and no significant improvements were reported (Chiu 2008). Neither of the two other studies identified a significant effect on LDL.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Educational or behavioural interventions for patients versus usual care, Outcome 6: Mean low density lipoprotein

Organisational interventions

Pooled data from five studies indicated that organisational interventions were associated with a significant reduction in mean LDL levels (Analysis 2.6) (MD ‐0.19mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.30 to ‐0.09; n = 1154) (Table 2) (Brotons 2011; Evans 2010; Flemming 2013; Nailed Stroke 2010; McAlister 2014). There was, however, no statistically significant improvement in achieving LDL targets (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.13; N = 1790; P = 0.15; Analysis 2.7; Table 2). Heterogeneity was high (I² = 75%). Sensitivity analysis of a subgroup of nurse‐led care to achieve LDL levels were not associated with achieving LDL targets (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.13; N = 1790; Analysis 2.7) (Flemming 2013; Jönsson 2014; Nailed Stroke 2010). One study that involved prescribing pharmacists identified a greater association with achieving LDL target levels (fasting LDL ≤ 2 mmol/L) (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.26 to 3.31; P = 0.004) than non‐prescribing healthcare practitioners. However, no control was compared.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Organisational interventions versus usual care, Outcome 6: Mean low density lipoprotein

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Organisational interventions versus usual care, Outcome 7: Low density lipoprotein target achievement

High density lipoprotein (HDL)

Seven studies reported data on HDL, of which three evaluated an educational or behavioural intervention for patients (Chanruengvanich 2006; Kono 2013; MIST 2014), and four evaluated organisational interventions (Brotons 2011; Evans 2010; Flemming 2013; McAlister 2014). To ensure homogeneous data presentation, we multiplied the mean values by ‐1 to ensure that all scales pointed in the same direction for both educational and behavioural interventions for patients and for organisations interventions (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 2.8). This is in accordance with guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011c).

1.7. Analysis.