Abstract

Background

A woman may need to give birth prior to the spontaneous onset of labour in situations where the fetus has died in utero (also called a stillbirth), or for the termination of pregnancy where the fetus, if born alive would not survive or would have a permanent handicap. Misoprostol is a prostaglandin medication that can be used to induce labour in these situations.

Objectives

To compare the benefits and harms of misoprostol to induce labour to terminate pregnancy in the second and third trimester for women with a fetal anomaly or after intrauterine fetal death when compared with other methods of induction of labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (November 2009).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing misoprostol with placebo or no treatment, or any other method of induction of labour, for women undergoing induction of labour to terminate pregnancy in the second and third trimester following an intrauterine fetal death or for fetal anomalies.

Data collection and analysis

Both authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data.

Main results

We included 38 studies (3679 women).

Nine studies included pregnancies after intrauterine deaths, five studies included termination of pregnancies because of fetal anomalies when the fetus was still alive and the rest (24) presented the pooled data for intrauterine deaths, fetal anomalies and social reasons.

When compared with agents that have traditionally been used to induce labour in this setting (for example, gemeprost, prostaglandin E2 and prostaglandin F2alpha), vaginal misoprostol is as effective in ensuring vaginal birth within 24 hours, with a similar induction to birth interval. Vaginal misoprostol is associated with a reduction in the occurrence of maternal gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea when compared with other prostaglandin preparations. While the different treatments involving various prostaglandin preparations appear comparable for the reported outcomes, the information available regarding rare maternal complications, such as uterine rupture, is limited.

Authors' conclusions

The use of vaginal misoprostol in the termination of second and third trimester of pregnancy is as effective as other prostaglandin preparations (including cervagem, prostaglandin E2 and prostaglandin F2alpha), and more effective than oral administration of misoprostol. However, important information regarding maternal safety, and in particular the occurrence of rare outcomes such as uterine rupture, remains limited. Future research efforts should be directed towards determining the optimal dose and frequency of administration, with particular attention to standardised reporting of all relevant outcomes and assessment of rare adverse events. Further information is required about the use of sublingual misoprostol in this setting.

Plain language summary

Misoprostol for induction of labour to terminate pregnancy in the second or third trimester for women with a fetal anomaly or following intrauterine fetal death

A woman may need to give birth prior to the spontaneous onset of labour in middle to late pregnancy to terminate the pregnancy in situations where the fetus, if born alive, would not survive or would have permanent handicaps, or where the fetus has died in utero (also called a stillbirth). Misoprostol is a prostaglandin medication that can be used to induce labour in these situations. This review included 38 randomised controlled studies, involving 3679 women. Vaginal misoprostol was as effective as other agents in inducing labour and achieving vaginal birth within 24 hours, with a reduction in the occurrence of maternal side effects. Side effects include gastrointestinal disturbance (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea). The information on rare adverse events (including uterine rupture) is limited.

Background

Description of the condition

A woman may need to give birth prior to the spontaneous onset of labour in situations where the fetus has died in utero (also called a stillbirth), or for the termination of pregnancy where the fetus, if born alive, would not survive or would have significant disability. This situation is psychologically stressful for the woman, her partner and family, and for the health professionals caring for her.

When a baby dies before birth, the options for care are either to wait for labour to start spontaneously or to induce labour. Most women (over 90%) begin to contract and labour within three weeks of their baby dying, but if labour does not begin, there is a risk of developing a disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) (Weiner 1999). This complication develops when various factors in the blood which usually stop a person from bleeding (clotting factors) are used faster than they can be replaced. This increases the risk of severe bleeding complications or haemorrhage.

A disadvantage of a long interval between fetal death and birth relates to the degree of information that can be obtained from a postmortem examination or autopsy of the baby. Where there has been a considerable delay between the death of the baby and birth, the tissue may begin to break down, limiting the amount of information that can be obtained about the cause of death (Weiner 1999). This may have implications for counselling about the risks for any future pregnancy.

Description of the intervention

Inducing labour may involve the use of the hormone oxytocin which causes the uterus to contract (Kelly 2001). When labour is induced early in pregnancy, this has been associated with long and painful labours, as the uterus is less sensitive to oxytocin before term (Weiner 1999). Prostaglandins have been used to induce labour and are particularly useful where a woman's cervix is unfavourable or not ready to commence labour (Mackenzie 1999). Prostaglandins have been administered orally (French 2001), vaginally (Kelly 2003), into the cervix (intracervical), outside the amniotic sac (extra‐amniotically) (Hutton 2001), or intravenously (Luckas 2000). There are also mechanical devices which have been developed to dilate or open the cervix (Boulvain 2001).

How the intervention might work

Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin that is structurally related to prostaglandin E1 (PGE1). Misoprostol is licensed for use as an anti‐ulcer medication in the treatment of gastric ulcer disease and does not have a product license for use in pregnancy anywhere in the world. Despite this, the use of misoprostol in obstetric and gynaecological practice has increased, being used widely in the management of first and second trimester abortion (Dickinson 1998), and in the third trimester of pregnancy following intrauterine fetal death (Mariani‐Neto 1987). More recently, misoprostol has been used in the induction of labour at term in the presence of a viable fetus, with both vaginal (Hofmeyr 2003) and oral (Alfirevic 2006) routes of administration being used. Misoprostol has been investigated for use in the third stage of labour to prevent postpartum haemorrhage (Gulmezoglu 2007). Potential advantages to the use of misoprostol over other prostaglandin preparations include its stability at room temperature (other prostaglandins need to be stored in the refrigerator) and low cost. This has important implications for women in low‐resource countries.

The Cochrane reviews assessing misoprostol for the induction of labour at term in the presence of a live fetus (Alfirevic 2006; Hofmeyr 2003) concluded that there was considerable variation in both the dose and frequency of misoprostol administered to induce labour, and that at present the optimal dosing regimen is uncertain. There have been calls to further investigate the lowest effective dose of misoprostol, thereby minimising side effects and maximising safety for both the woman and her infant (Alfirevic 2006; Hofmeyr 2003).

Why it is important to do this review

The issues related to the use of low doses of misoprostol are a little different for women who are having labour induced to terminate their pregnancy because of fetal anomalies or after intrauterine fetal death. While side effects (including uterine hyperstimulation, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea) and safety (particularly rare complications such as uterine rupture) are important considerations for the woman, issues related to fetal wellbeing are not. Furthermore, it is necessary to consider the receptivity of the uterus to prostaglandin medication, especially at early gestational ages, where the use of low doses of misoprostol may be ineffective in inducing labour, or be associated with a long induction to delivery interval. Sensitivity of the uterus to medication may also be influenced by whether or not the fetus is alive at the time of induction.

The aim of this review is to assess the benefits and harms of misoprostol to induce labour after the death in utero of a fetus, or for fetal anomalies in the second or third trimester of pregnancy when compared with other methods of induction of labour.

Clinical trials of medical treatment, including misoprostol, for fetal deaths before 24 weeks are considered in a separate Cochrane review (Neilson 2006).

In addition, there is a published Cochrane protocol planning to review trials of medical treatments, including misoprostol, for mid‐trimester termination of pregnancy (Medema 2005).

Objectives

To compare, using the best available evidence, the benefits and harms of misoprostol to induce labour to terminate pregnancy in the second and third trimester for women with a fetal anomaly or after intrauterine fetal death when compared with other methods of induction of labour.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published, unpublished, and ongoing randomised controlled trials comparing misoprostol (either oral or vaginal administration) with placebo or no treatment, or any other method of induction of labour (including prostaglandins administered orally, vaginally, intracervically, extra‐amniotically; oxytocin; misoprostol (oral or vaginal); mifepristone; or mechanical methods of induction including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter or laminaria).

We excluded quasi‐randomised trials (e.g. those randomised by date of birth or hospital number). We have included studies reported only in abstract form in the 'Studies awaiting classification' category, and will include these in analyses when published as full reports.

Types of participants

Women undergoing induction of labour to terminate pregnancy in the second and third trimester following an intrauterine fetal death or for fetal anomalies. Where trials included a mix of indications for termination of pregnancy (including social reasons), they were eligible for inclusion if less than 30% of participants were undergoing termination of pregnancy for social indications, or where information was reported separately by indication.

Types of interventions

Misoprostol for the induction of labour to terminate pregnancy versus placebo or no treatment, or any other method of induction of labour to terminate pregnancy in the second and third trimester. We have included studies reporting comparisons between different routes of administration or different doses of misoprostol.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Vaginal birth not achieved within 24 hours

Induction to delivery interval

Secondary outcomes

Analgesia requirements (as defined by trial authors)

Blood loss (as defined by trial authors)

Need for blood transfusion

Surgical evacuation of the uterus (as defined by trial authors)

Puerperal sepsis requiring antibiotic treatment

Maternal death or serious maternal morbidity (e.g. admission to intensive care unit; uterine rupture)

Side effects ‐ all

Side effects ‐ nausea

Side effects ‐ vomiting

Side effects ‐ diarrhoea

Side effects ‐ other

Psychological wellbeing of the woman (as defined by trial authors)

Maternal satisfaction with induction process

Only outcomes with available data appear in the analysis table. Outcome data that were not prestated by the review authors, but reported by the authors, are labelled as such in the analysis.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (November 2009).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Both review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should have produced comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

adequate (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

inadequate (any non random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We judged studies at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate, inadequate or unclear for participants;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for personnel;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We state whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or was supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses. We assessed methods as:

adequate (defined as less than 20% incomplete data);

inadequate:

unclear.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (where it was clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

inadequate (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

(6) Other sources of bias

We have described for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias, including study design, early stopping of the trial due to data‐dependent processes or extreme baseline imbalance.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias as:

yes;

no;

unclear.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2008). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking Sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we present results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any eligible cluster‐randomised trials.

Crossover trials

Crossover trials are not considered an appropriate study design to evaluate this intervention.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data (considered to be more than 20%) in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. Where we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 50%), we have explored it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspect reporting bias (see ‘Selective reporting bias’ above), we have attempted to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we have explored the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by a Sensitivity analysis.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We used fixed‐effect inverse variance meta‐analysis for combining data where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. Where we suspected clinical or methodological heterogeneity between studies sufficient to suggest that treatment effects may differ between trials, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis.

If we identified substantial heterogeneity in a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis, we have noted this and repeated the analysis using a random‐effects method.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses:

oral versus vaginal route of administration of misoprostol;

dose of misoprostol used;

indication for induction of labour (that is intrauterine fetal death versus termination of live pregnancy); and

gestational age (second versus third trimester of pregnancy as defined by trial authors);

maternal parity; and

previous caesarean section.

We used the following primary outcomes in subgroup analysis:

vaginal birth not achieved within 24 hours;

induction to delivery interval.

For fixed‐effect meta‐analyses, we conducted planned subgroup analyses classifying whole trials by interaction tests as described by Deeks 2001. For random‐effects meta‐analyses, we assessed differences between subgroups by inspection of the subgroups’ confidence intervals; non‐overlapping confidence intervals indicate a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not conduct sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Our search strategy identified 54 studies for consideration, of which we included 38 (involving 3679 women), excluded 11 studies and five studies are awaiting classification.

Included studies

Thirty‐eight studies (involving 3490 women) met our inclusion criteria. The interventions compared included:

vaginal misoprostol compared with oral misoprostol (Akoury 2004; Bebbington 2002; Behrashi 2008; Caliskan 2005; Chittacharoen 2003; Dickinson 2003; Elhassan 2008; Fadalla 2004; Gilbert 2001; Neto 1988; Nyende 2004);

vaginal misoprostol compared with vaginal gemeprost (alone or with oxytocin) (Dickinson 1998; Nor Azlin 2006; Nuutila 1997);

vaginal misoprostol compared with vaginal prostaglandin E2 (alone or with other agents) (Herabutya 1997; Jain 1999; Kara 1999; Makhlouf 2003; Owen 1999);

vaginal misoprostol compared with prostaglandin F2alpha (Akoury 2004; Ghorab 1998; Munthali 2001; Perry 1999; Su 2005; Zuo 1998);

vaginal misoprostol compared with oxytocin alone (Nakintu 2001);

vaginal misoprostol alone compared with vaginal misoprostol and oxytocin (Hidar 2001);

vaginal misoprostol compared with vaginal glyceryl trinitrate (Makhlouf 2003);

vaginal misoprostol alone compared with vaginal misoprostol and laminaria (Jain 1994);

vaginal misoprostol alone compared with vaginal misoprostol and nitric oxide donor (Hidar 2005);

oral misoprostol compared with prostaglandin F2alpha (Akoury 2004);

combination of oral and vaginal misoprostol compared with vaginal misoprostol alone (Dickinson 2003; Feldman 2003), oral misoprostol alone (Dickinson 2003), and dilation and evacuation (Grimes 2005);

sublingual misoprostol compared with vaginal misoprostol (Caliskan 2005; Elhassan 2008);

sublingual misoprostol compared with oral misoprostol (Caliskan 2005; Elhassan 2008); and two different doses of sublingual misoprostol (Caliskan 2009).

Dose and route of administration

There were several trials comparing a dosing interval of six hours with 12 hours (Herabutya 2005; Jain 1996; Nuutila 1997), and several trials comparing varying doses of vaginal misoprostol. These were arbitrarily divided into those comparing a low dose (less than 800 mcg in a 24‐hour period) with a moderate dose (between 800 mcg and 2400 mcg in a 24‐hour period) (Dickinson 2002; Niromanesh 2005), and those comparing a moderate dose (800 mcg to 2400 mcg in a 24‐hour period) with a high dose (in excess of 2400 mcg in a 24‐hour period) (Pongsatha 2004). The route of administration of misoprostol (vaginal, oral or combined oral and vaginal) varied considerably across trials, as did the dose used (a cumulative dose in 24 hours ranging from 400 mcg to 3200 mcg) and the dosing interval administered (from three‐hourly intervals to 12‐hourly intervals).

Participant population

Most trials recruited women undergoing termination of pregnancy in the presence of both a live fetus, and following intrauterine fetal death, with no separate reporting of outcomes by method of induction of labour and indication for induction.

Reported outcomes

There was variable reporting of the prespecified outcomes, with the majority of trials only reporting vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours, induction to birth interval (often as a median and interquartile range precluding inclusion in the meta‐analysis), surgical evacuation of the uterus, and side effects from therapy. More severe but less common complications (including excessive blood loss, need for transfusion, and complications such as uterine rupture) were poorly reported. Maternal satisfaction with the process of induction of labour was reported in several trials, but reported as a median and interquartile range, precluding inclusion in the meta‐analysis.

For further details seeCharacteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded 11 trials. Six trials involved only women undergoing termination of pregnancy for 'social' indications (Biswas 2007; El‐Refaey 1995; Guix 2005; Marquette 2005; Nigam 2006; Saha 2006); and three trials used quasi‐randomisation methods (Eng 1997; Herabutya 2001; Yapar 1996). In one trial, termination of pregnancy was effected in all women using the same misoprostol regimen, with randomisation occurring to administration on an inpatient versus outpatient basis (Gonzalez 2001). One trial involved women at seven to 12 weeks' gestation with early pregnancy failure (Ayudhaya 2006). For further details seeCharacteristics of excluded studies.

Studies awaiting classification

Five trials have been presented only in abstract form; we will assess these once further details are obtained (Abdel Fattah 1997; Agrawal 2006; Nuthalapaty 2004; Roy 2003; Surita 1997). For further details seeCharacteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Risk of bias in included studies

The overall quality of the included trials varied from good to fair. All trials were stated to be randomised, and while most utilised a random number table to generate the randomisation sequence, the method of randomisation was unclear in 13 of the trials (Behrashi 2008; Elhassan 2008; Fadalla 2004; Ghorab 1998; Herabutya 1997; Hidar 2005; Jain 1996; Kara 1999; Neto 1988; Niromanesh 2005; Nor Azlin 2006; Nyende 2004; Pongsatha 2004). Allocation concealment involved the use of sealed opaque envelopes in the majority of trials, but was considered to be unclear in 19 of the trials (Behrashi 2008; Caliskan 2005; Elhassan 2008; Fadalla 2004; Gilbert 2001; Ghorab 1998; Herabutya 1997; Hidar 2005; Jain 1994; Jain 1996; Jain 1999; Kara 1999; Makhlouf 2003; Nakintu 2001; Neto 1988; Niromanesh 2005; Nyende 2004; Pongsatha 2004; Zuo 1998). Blinding of women and outcome assessors was achieved in only one trial (Dickinson 1998), with women, caregivers and outcome assessors aware of the treatment allocated in all of the remaining trials. Four trials were stopped prior to reaching the projected sample size following an interim analysis of results (Dickinson 1998; Dickinson 2003; Gilbert 2001; Owen 1999), and one trial was stopped prior to reaching sample size due to difficulties with recruitment (Grimes 2005).

Refer to table Characteristics of included studies for further details.

Effects of interventions

Vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol (Analysis 1)

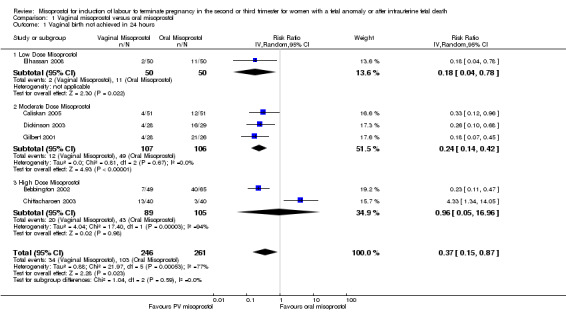

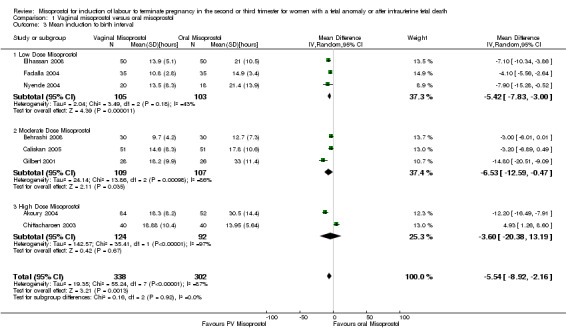

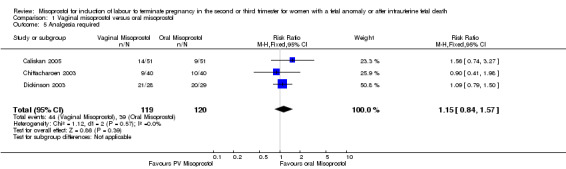

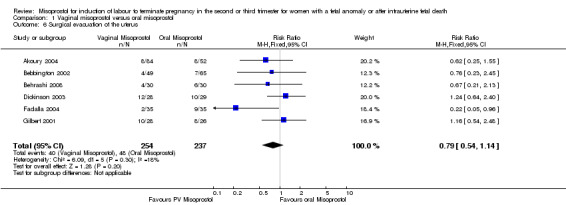

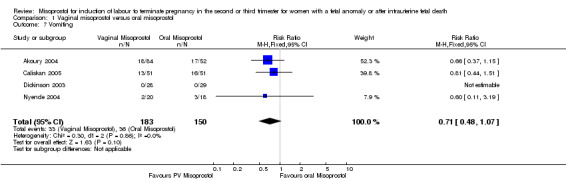

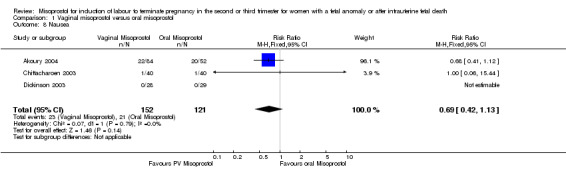

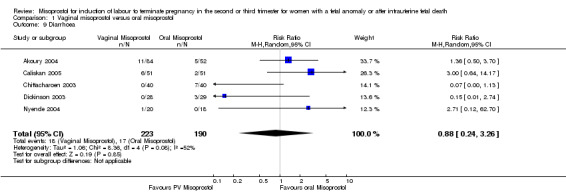

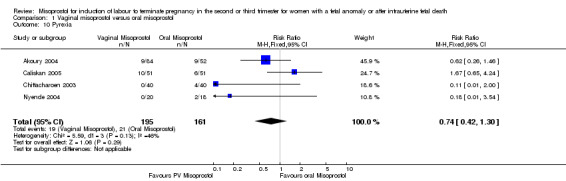

We included 11 studies involving 855 women. Women administered vaginal misoprostol were more likely to achieve vaginal birth within 24 hours (risk ratio (RR) 0.18, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.04 to 0.78; I2 = 77%; random‐effects model (six studies, 507 women)) and had a shorter mean induction to birth interval (mean difference (MD) ‐5.54 hours, 95% CI ‐8.92 to ‐2.16; I2 = 87%; random‐effects model (eight studies, 590 women)) when compared with women administered oral misoprostol. The test for heterogeneity was significant for these outcomes, possibly accounted for by the Chittacharoen 2003 trial, in which a much higher dose of oral misoprostol was used than in the other trials. There were no statistically significant differences for the other outcomes reported including need for analgesia, surgical evacuation of the uterus, and side effects including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and pyrexia.

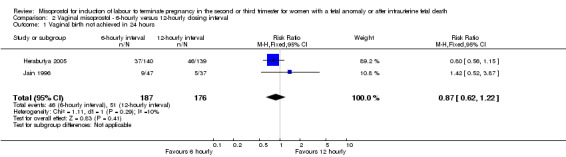

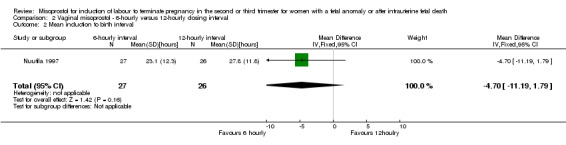

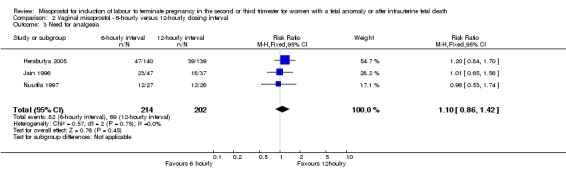

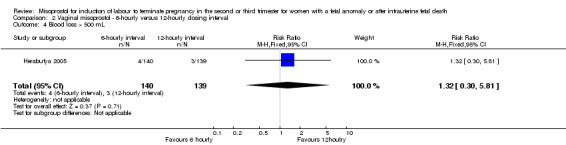

Vaginal misoprostol six‐hourly dosing intervals versus 12‐hourly dosing intervals (Analysis 2)

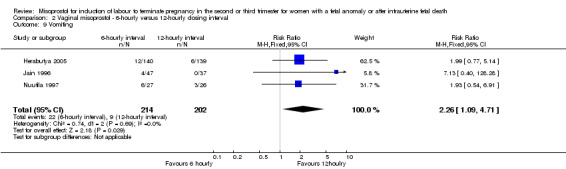

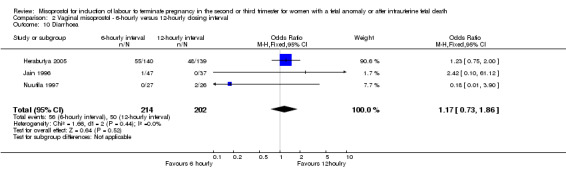

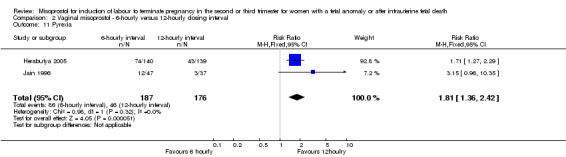

We included three studies involving 416 women. There were no statistically significant differences identified between the dosing regimens for the outcomes vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours or the mean induction to birth interval. However, the six‐hourly dosing interval was associated with an increase in women's experience of side effects, particularly vomiting (RR 2.26, 95% CI 1.09 to 4.71 (three studies, 416 women)).

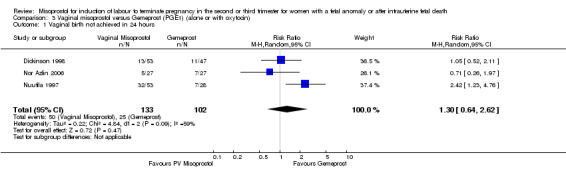

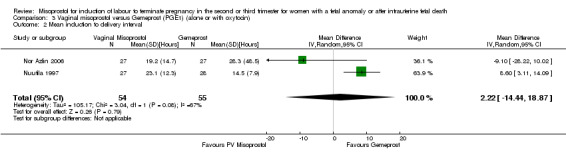

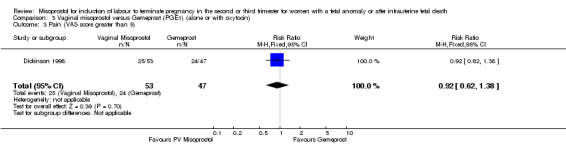

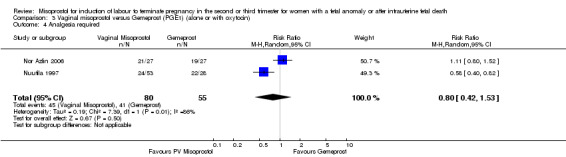

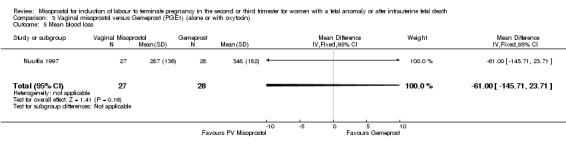

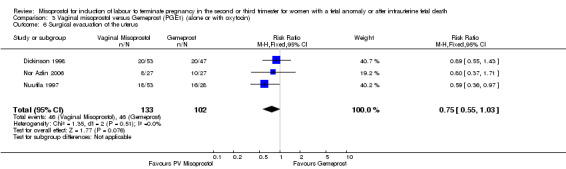

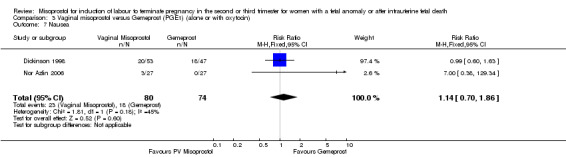

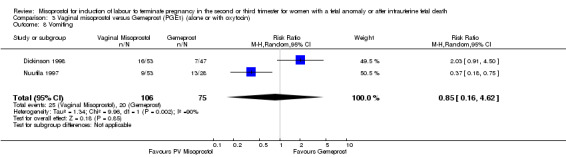

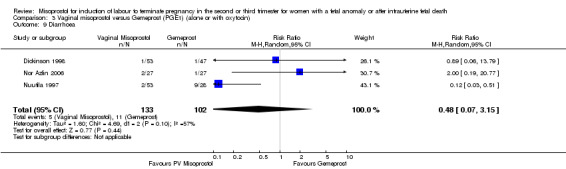

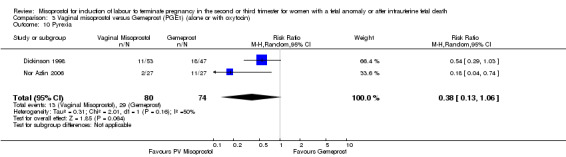

Vaginal misoprostol versus Gemeprost (alone or with oxytocin) (Analysis 3)

We included four studies involving 315 women. There were no statistically significant differences identified between the two agents for the outcomes vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours, mean induction to delivery interval, analgesic requirements, blood loss, or experience of side effects, although the outcome pyrexia was of borderline statistical significance (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.13 to 1.06 (two studies, 154 women)). However, there was statistical heterogeneity identified, possibly accounted for by the low dose of misoprostol used in the trial by Nuutila (Nuutila 1997).

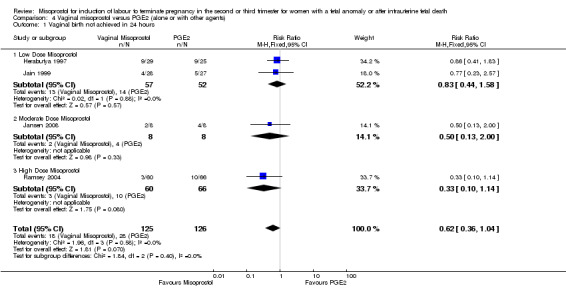

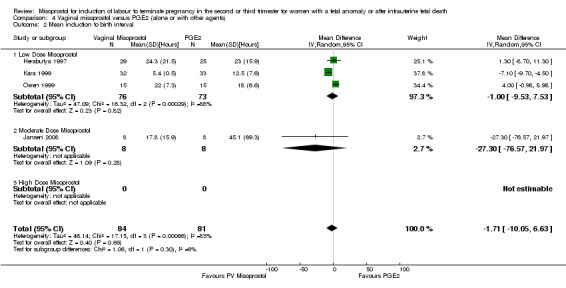

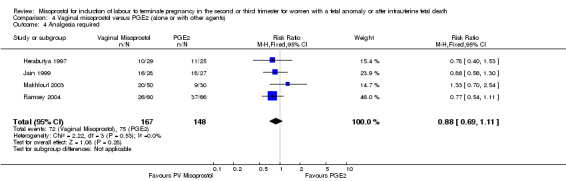

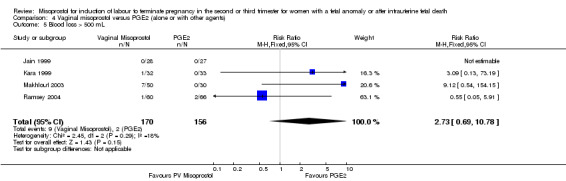

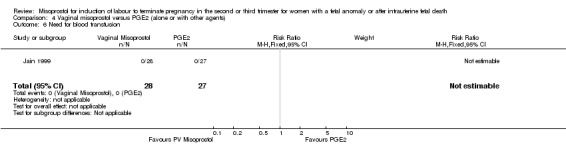

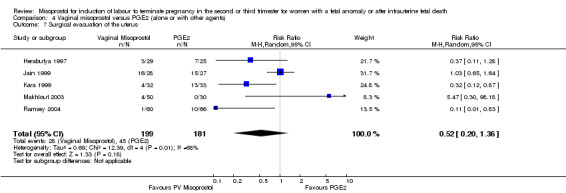

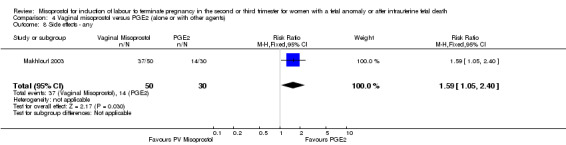

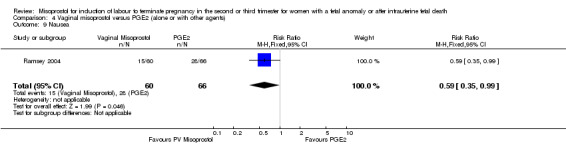

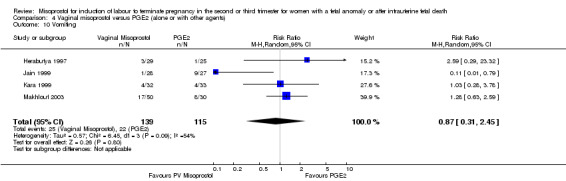

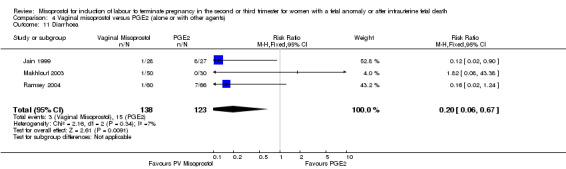

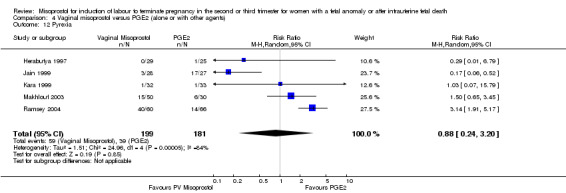

Vaginal misoprostol versus prostaglandin E2 (alone or with other agents) (Analysis 4)

We included six studies involving 410 women. There were no statistically significant differences in a woman's chance of achieving vaginal birth within 24 hours (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.04), or in their mean induction to birth interval (MD ‐1.71 hours, 95% CI ‐10.05 to 6.63; I2 = 83%; random‐effects (four studies, 165 women)). Women administered misoprostol were less likely to experience any side effects (RR 1.59, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.40 (one study, 80 women)), to experience nausea (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.99 (one study, 126 women)), or diarrhoea (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.67 (three studies, 261 women)) when compared with women administered prostaglandin E2.

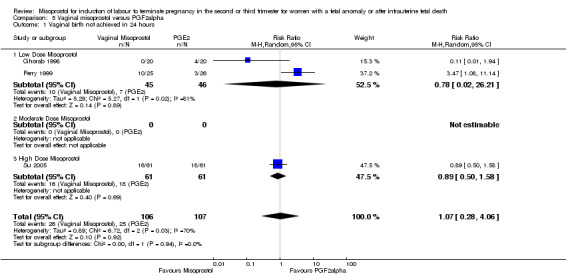

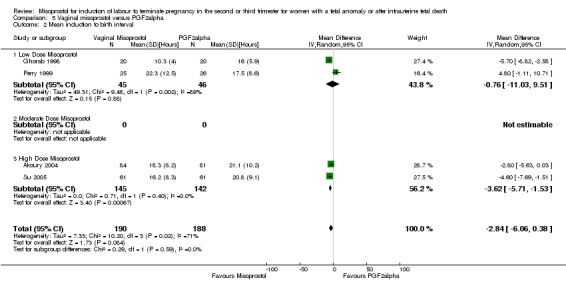

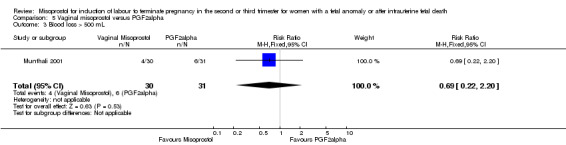

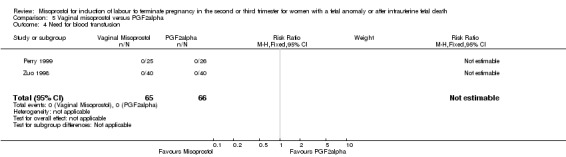

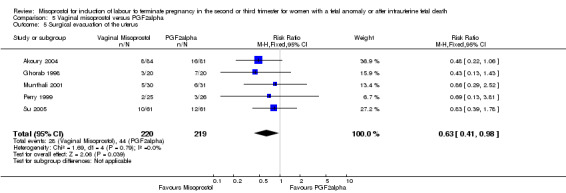

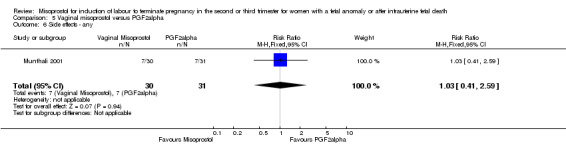

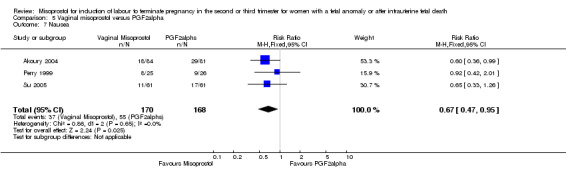

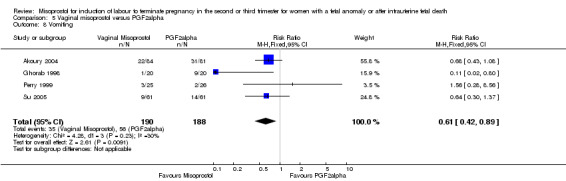

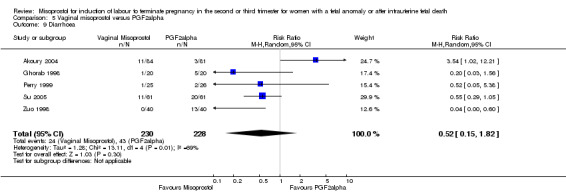

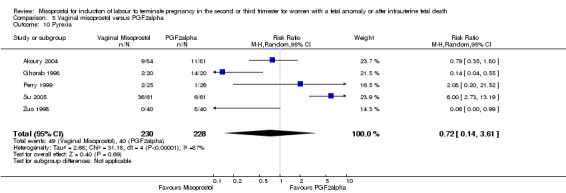

Vaginal misoprostol versus prostaglandin F2alpha (Analysis 5)

We included six studies involving 534 women. When compared with prostaglandin F2alpha, vaginal misoprostol was not associated with a statistically significant difference in a woman's chance of achieving vaginal birth within 24 hours (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.28 to 4.06; I2 = 70%, random‐effects (three studies, 213 women) or in the mean induction to birth interval (MD ‐2.84, 95% CI ‐6.06 to 0.38; I2 = 71%, random‐effects (four studies, 378 women)). Women administered vaginal misoprostol were less likely to require surgical evacuation of the uterus (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.98 (five studies, 439 women)), and less likely to experience both nausea (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.95 (three studies, 338 women)) and vomiting (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.89 (four studies, 378 women)).

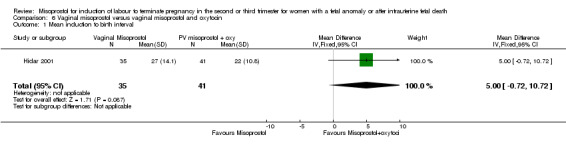

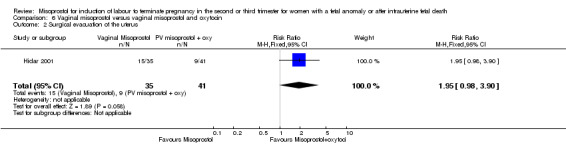

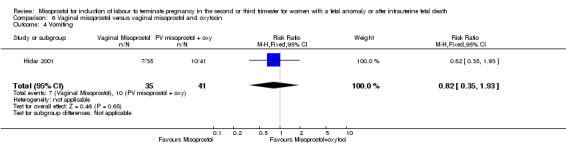

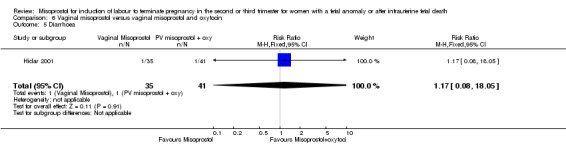

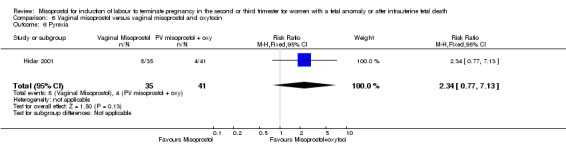

Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and oxytocin (Analysis 6)

We identified a single trial of 76 women, with no statistically significant differences reported for the outcomes: mean induction to birth interval; surgical evacuation of the uterus; side effects; vomiting; diarrhoea; or pyrexia.

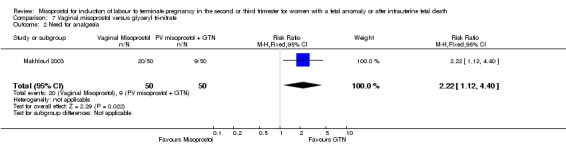

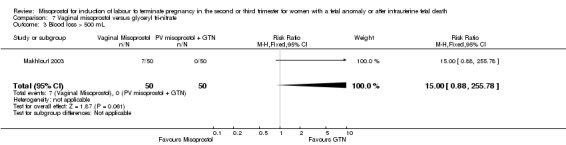

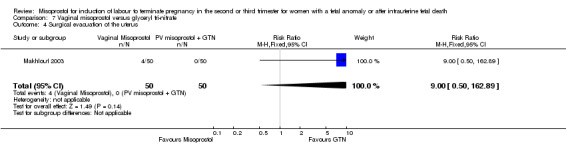

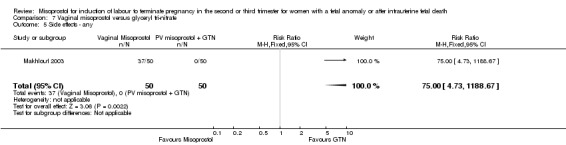

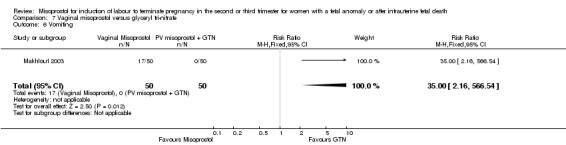

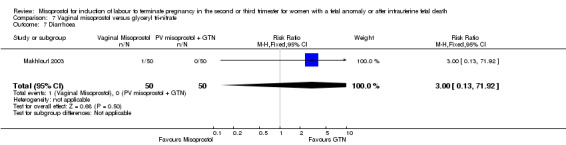

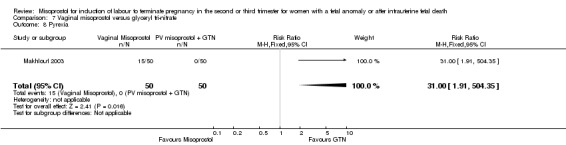

Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal glyceryl tri‐nitrate (Analysis 7)

We identified a single trial of 100 women, in which no primary outcomes were reported. Women who were administered vaginal misoprostol were more likely to require analgesia (RR 2.22, 95% CI 1.12 to 4.40 (one study, 100 women)), and to experience any side effects (RR 75.00, 95% CI 4.73 to 1188.78), including vomiting (RR 35.00, 95% CI 2.16 to 566.54) and pyrexia (RR 31.00, 95% CI 1.91 to 504.35) when compared with women administered vaginal glyceryl tri‐nitrate.

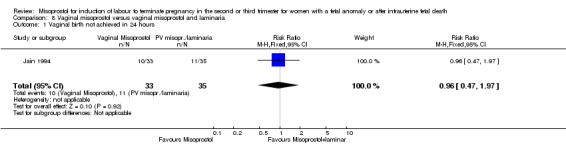

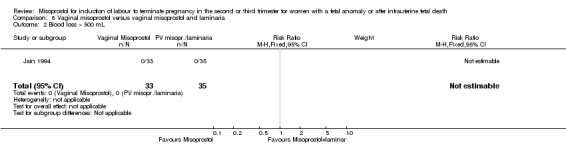

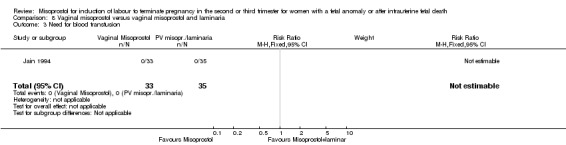

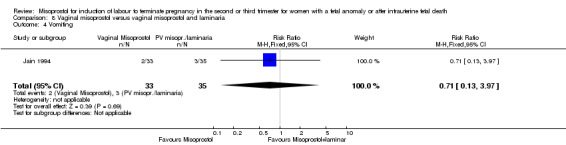

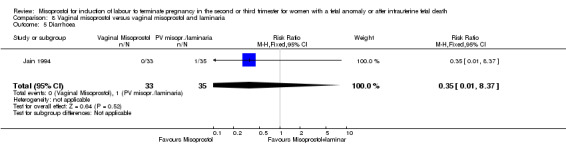

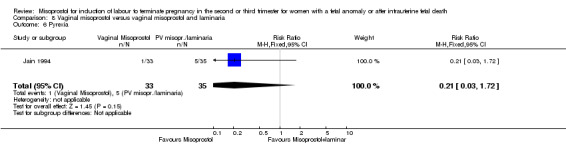

Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and laminaria (Analysis 8)

We identified a single trial of 68 women. There were no statistically significant differences identified between the two methods of induction for the following outcomes: vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours; blood loss greater than 500 mL; need for transfusion; and side effects (vomiting, diarrhoea, and pyrexia).

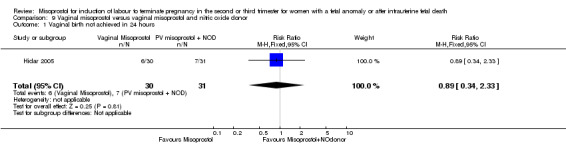

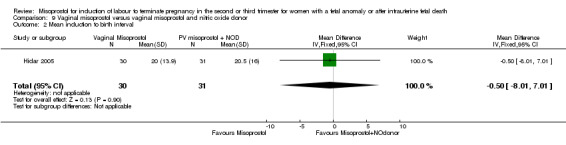

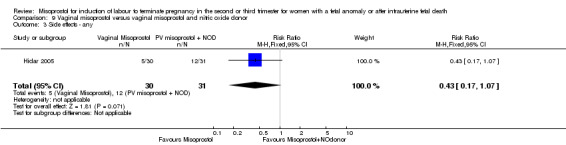

Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and vaginal nitric oxide donor (Analysis 9)

We identified a single trial involving 61 women, with no statistically significant differences reported for the following outcomes: vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours; mean induction to birth interval; and any side effects.

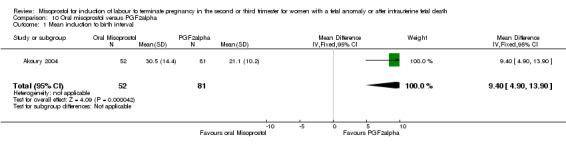

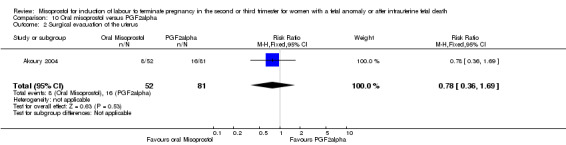

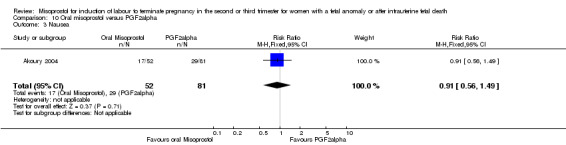

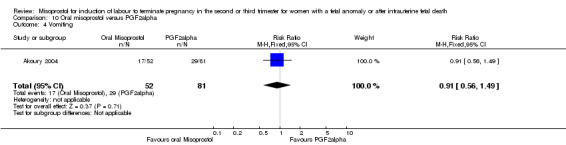

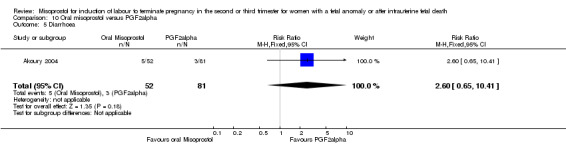

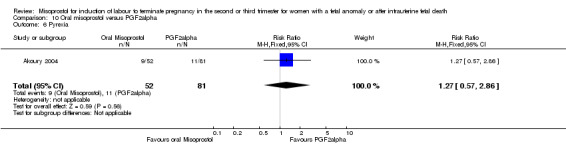

Oral misoprostol versus prostaglandin F2alpha (Analysis 10)

We identified a single trial involving 133 women. Women who were administered oral misoprostol had a longer mean induction to birth interval when compared with those women administered prostaglandin F2alpha (MD 9.40, 95% CI 4.9 to 13.90 (one study, 133 women)). There were no statistically significant differences identified for the following outcomes: need for surgical evacuation of the uterus; nausea; vomiting; diarrhoea; and pyrexia.

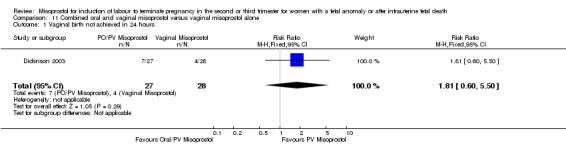

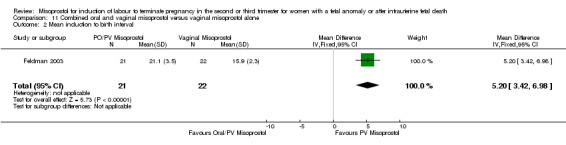

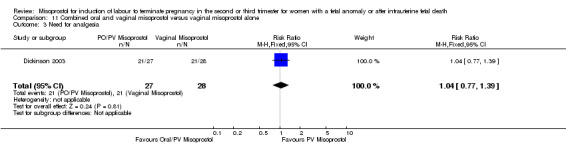

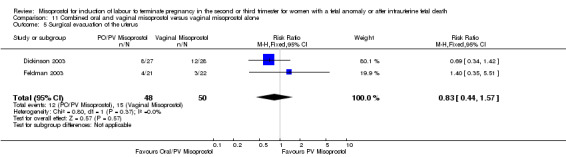

Combined oral and loading dose vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol alone (Analysis 11)

We included two studies involving 98 women. Women who received vaginal misoprostol alone had a longer mean induction to birth interval (MD 5.20, 95% CI 3.42 to 6.98 (one study, 43 women)) when compared with women who were administered oral misoprostol following a loading dose of vaginal misoprostol. There were no statistically significant differences identified for the following outcomes: vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours; need for analgesia; surgical evacuation of the uterus; and side effects (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea).

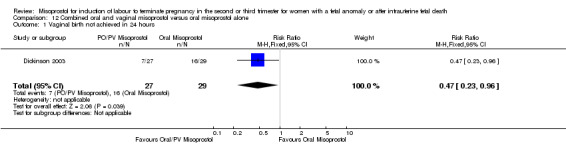

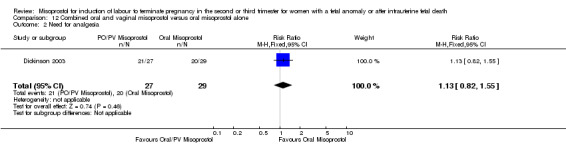

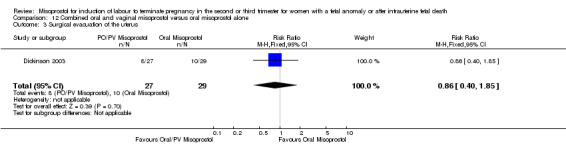

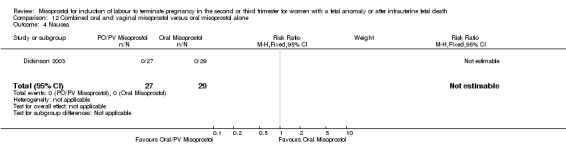

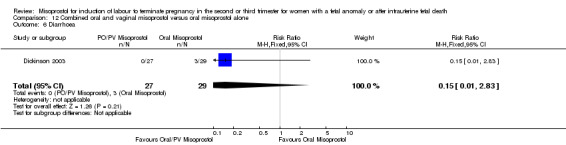

Combined oral and loading dose vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol alone (Analysis 12)

We identified one study involving 56 women. The addition of a loading dose of vaginal misoprostol reduced the chance of a woman not achieving vaginal birth within 24 hours when compared with oral misoprostol alone (RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.96 (one study, 56 women)). There were no other differences identified between the two methods of induction for the following outcomes: need for analgesia; surgical evacuation of the uterus; or side effects (nausea, vomiting, or diarrhoea).

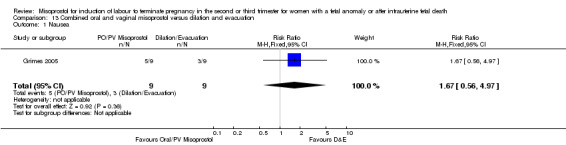

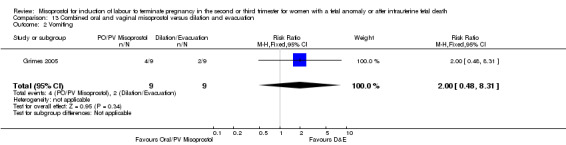

Combined oral and loading dose vaginal misoprostol versus dilation and evacuation (Analysis 13)

We identified one study involving 18 women. There were no statistically significant differences identified between the two methods for the outcomes nausea, vomiting, or diarrhoea.

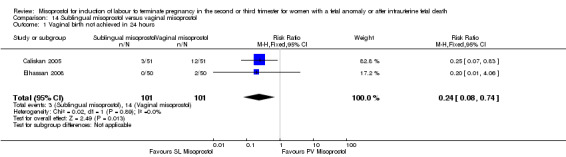

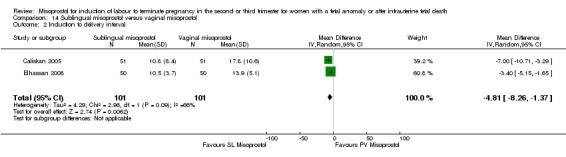

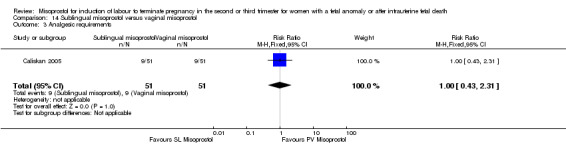

Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol (Analysis 14)

We identified two studies involving 202 women. Women who were administered sublingual misoprostol were more likely to achieve vaginal birth within 24 hours (RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.74 (two studies, 202 women)) and had a shorter mean induction to birth interval (MD ‐4.81 hours, 95% CI ‐8.26 to ‐1.37; I2 = 66%, random‐effects (two studies, 202 women)) when compared with administration of vaginal misoprostol. There were no other differences identified between the two methods of induction for the following outcomes: need for analgesia; side effects (vomiting, diarrhoea, or pyrexia).

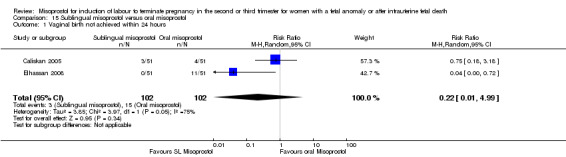

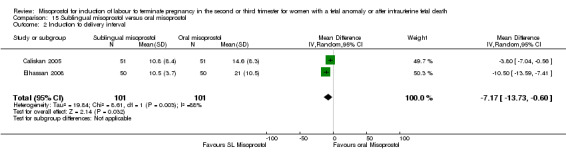

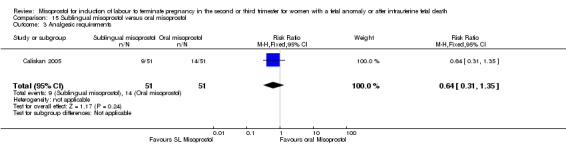

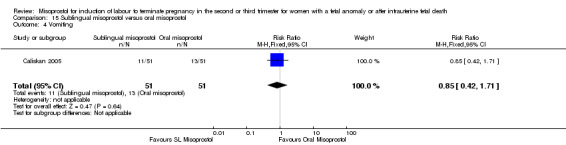

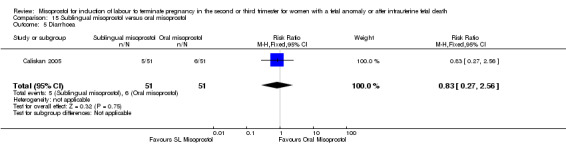

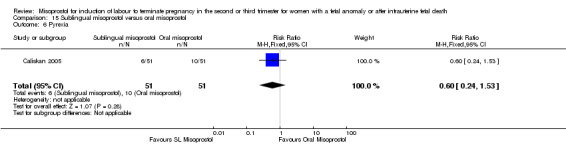

Sublingual misoprostol versus oral misoprostol (Analysis 15)

We identified two studies involving 204 women. Women who were administered sublingual misoprostol had a shorter mean induction to birth interval (MD ‐7.17 hours, 95% CI ‐13.73 to ‐0.60; I2 = 88%, random‐effects (two studies, 202 women)) but were no more likely to achieve vaginal birth within 24 hours (RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.01 to 4.99; I2 = 75%, random‐effects (two studies, 204 women)) when compared with administration of oral misoprostol. There were no other differences identified between the two methods of induction for the following outcomes: need for analgesia; and side effects (vomiting, diarrhoea, or pyrexia).

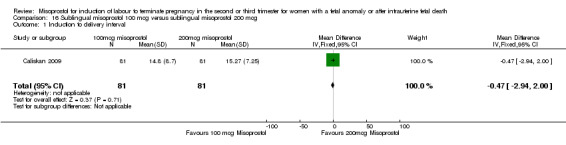

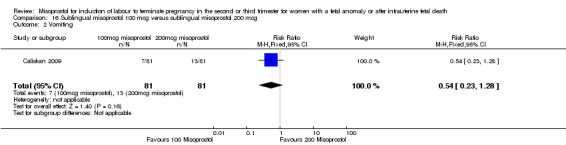

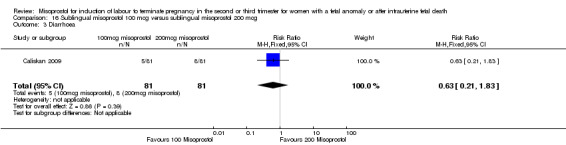

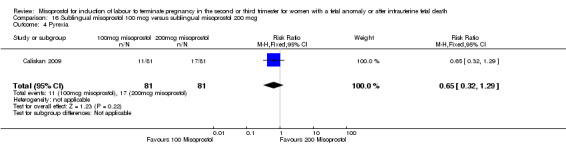

Sublingual misoprostol 100 mcg versus sublingual misoprostol 200 mcg (Analysis 16)

We identified one study involving 81 women. There were no statistically significant differences identified between the two doses of misoprostol for the following outcomes: vomiting, diarrhoea, or pyrexia.

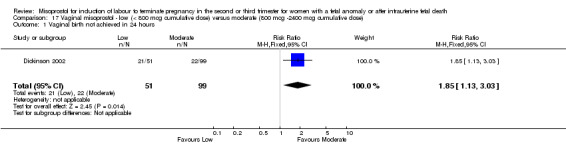

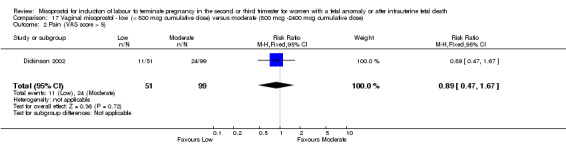

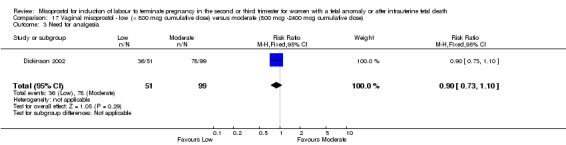

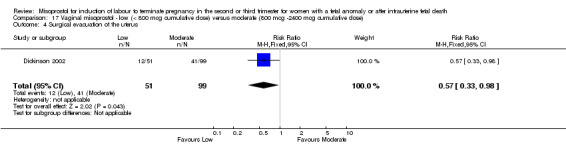

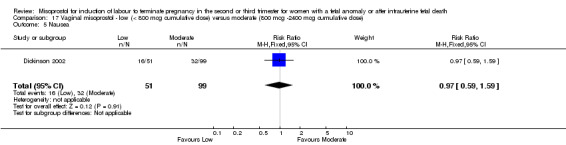

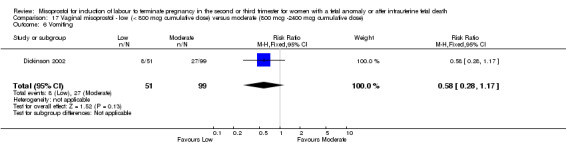

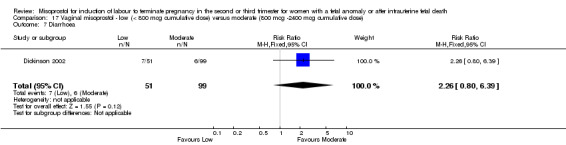

Low dose vaginal misoprostol (< 800 mcg) versus moderate dose vaginal misoprostol (800 mcg to 2400 mcg) (Analysis 17)

We identified a single study involving 150 women. The use of lower cumulative doses of misoprostol was associated with an increased chance of a woman not achieving vaginal birth within 24 hours when compared with moderate doses of misoprostol (RR 1.85, 95% CI 1.13 to 3.03 (one study, 150 women)), and a reduction in the need for surgical evacuation of the uterus (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.98 (one study, 150 women)). There were no significant differences identified for the following outcomes: need for analgesia; or side effects (nausea, vomiting, or diarrhoea).

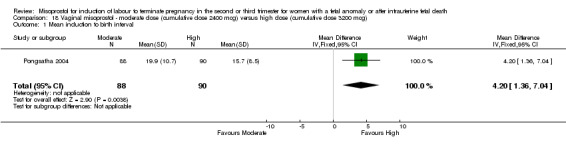

Moderate dose vaginal misoprostol (800 mcg to 2400 mcg) versus high dose vaginal misoprostol (greater than 2400 mcg) (Analysis 18)

We identified a single study involving 178 women. The use of moderate cumulative doses of misoprostol over a 24‐hour period was associated with an increased mean induction to birth interval when compared with higher doses of misoprostol (MD 4.20 hours, 95% CI 1.36 to 7.04 (one study, 178 women)).

Subgroup analyses

It was not possible to explore the effect of induction of labour in the presence of a live fetus or following intrauterine fetal death. Where studies included both indications for termination of pregnancy, outcomes were not reported separately by indication for induction, or by the method of induction used. It was not possible to explore the effect of gestational age on the termination process, as studies did not separately report outcomes for women undergoing termination in the second or third trimester of pregnancy. Similarly, it was not possible to explore the effect of maternal parity, or the presence of a prior caesarean birth on the induction process, as women with a scarred uterus were often excluded from the trials.

Discussion

Misoprostol is being used widely in the obstetric community as an agent to induce labour for termination of pregnancy in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy for fetal anomaly or following intrauterine fetal demise. This systematic review includes the available randomised controlled trials comparing the use of misoprostol in second and third trimester of pregnancy with other methods of labour induction to terminate pregnancy. Overall, the quality of the trials available for inclusion was reasonable, although there was considerable variation in the outcomes reported, and in the regimen of misoprostol adopted.

When compared with agents that have traditionally been used to induce labour in this setting (for example, gemeprost, prostaglandin E2 and prostaglandin F2alpha), vaginal misoprostol is as effective in effecting vaginal birth within 24 hours, with a similar induction to birth interval. When compared with other prostaglandin preparations, the occurrence of maternal gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea is reduced with the use of vaginal misoprostol. While the different treatments involving various prostaglandin preparations appear comparable for the reported outcomes, the information available regarding rare maternal complications, such as uterine rupture, is limited.

The use of oral misoprostol for induction of labour for termination in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy for fetal anomaly or following intra‐uterine fetal demise, is less effective than vaginal misoprostol, with women experiencing a longer induction to birth interval, and an increased chance of remaining undelivered 24 hours after the induction process commences. The more limited information available about the use of sublingual misoprostol in this setting would suggest that it is more effective than both oral or vaginal administration. Information about women's preferences for an oral induction method in this clinical setting is limited, with suggestions that satisfaction with the induction process is more related to the duration of the induction rather than the route of administration of medication (Akoury 2004; Dickinson 2003; Grimes 2005).

The Cochrane systematic reviews of the use of oral (Hofmeyr 2003) and vaginal (Alfirevic 2006) misoprostol for induction of labour at term in the presence of a live fetus identified significant variation in both the dose and frequency of drug administration, concluding that at present, the optimal regimen for misoprostol is uncertain. Similarly, there is wide variation in the dose, frequency of administration and route of administration of misoprostol to effect termination of pregnancy in the second or third trimester of pregnancy. There have been calls for further investigation of the lowest effective dose of misoprostol to induce labour at term in the presence of a live fetus, to ensure minimal side effects for the woman, and maintain safety for both the woman and fetus (Alfirevic 2006; Hofmeyr 2003). These efforts have been somewhat hampered by the preparation of misoprostol as a 100 mcg or 200 mcg tablet. Concerns about fetal safety and avoidance of toxicity are not relevant in the situation of induction of labour following fetal death or to effect termination of pregnancy in the second and third trimester. However, issues of side effects and safety for the woman remain. While this meta‐analysis indicates a low occurrence of medication side effects with the use of misoprostol, not all trials provided this information. There are insufficient data to assess the occurrence of rare but potentially life threatening complications for the woman, including uterine rupture, with not all trials reporting serious adverse outcomes, and at present a combined sample size underpowered to be able to detect all but large differences.

The use of low doses of misoprostol must take into account the receptivity of the uterus to prostaglandin agents, particularly at early gestational ages. The use of lower doses of misoprostol was associated with an increased chance of a woman not achieving vaginal birth within 24 hours, and a longer induction to birth interval, when compared with higher doses of misoprostol. In this situation, low dose medication may be ineffective in inducing labour or result in an unacceptably long induction to delivery interval. However, the increased dose of misoprostol to effect termination must be balanced against an increase in the occurrence of maternal gastrointestinal side effects. The effect of increasing the dose of misoprostol on the occurrence of rare but potentially life threatening maternal complications remains uncertain.

Future research efforts should be directed towards determining the optimal dose and frequency of administration, with particular attention to standardised reporting of all relevant outcomes and assessment of rare adverse events. Further information is required about the use of sublingual misoprostol in this clinical setting.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The use of vaginal misoprostol in the termination of second and third trimester of pregnancy is as effective as other prostaglandin preparations (including cervagem, prostaglandin E2 and prostaglandin F2alpha), and more effective than oral administration of misoprostol. However, important information regarding maternal safety, and in particular the occurrence of rare outcomes such as uterine rupture, remains limited.

Implications for research.

Future research efforts should be directed towards determining the optimal dose and frequency of administration, with particular attention to standardised reporting of all relevant outcomes and assessment of rare adverse events. Further information is required about the use of sublingual misoprostol in this clinical setting.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 April 2018 | Amended | Added Published notes to clarify that this review has been relinquished by the review team. A new review team will prepare a new review on this topic, following a new protocol. |

Notes

This review is now out‐of‐date and has been relinquished by the review team. A new team will now prepare a new review on this topic, following a new protocol. This review will be linked to the new review once it has been published.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Andrea Strane for translating the Neto 1988 study, and Shanshan Han for translating the Zuo 1998 study.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team) and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours | 6 | 507 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.15, 0.87] |

| 1.1 Low Dose Misoprostol | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.04, 0.78] |

| 1.2 Moderate Dose Misoprostol | 3 | 213 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.14, 0.42] |

| 1.3 High Dose Misoprostol | 2 | 194 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.05, 16.96] |

| 3 Mean induction to birth interval | 8 | 640 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.54 [‐8.92, ‐2.16] |

| 3.1 Low Dose Misoprostol | 3 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.42 [‐7.83, ‐1.00] |

| 3.2 Moderate Dose Misoprostol | 3 | 216 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐6.53 [‐12.59, ‐0.47] |

| 3.3 High Dose Misoprostol | 2 | 216 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.60 [‐20.38, 13.19] |

| 5 Analgesia required | 3 | 239 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.84, 1.57] |

| 6 Surgical evacuation of the uterus | 6 | 491 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.54, 1.14] |

| 7 Vomiting | 4 | 333 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.48, 1.07] |

| 8 Nausea | 3 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.42, 1.13] |

| 9 Diarrhoea | 5 | 413 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.24, 3.26] |

| 10 Pyrexia | 4 | 356 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.42, 1.30] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 3 Mean induction to birth interval.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 5 Analgesia required.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 6 Surgical evacuation of the uterus.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 7 Vomiting.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 8 Nausea.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 9 Diarrhoea.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 10 Pyrexia.

Comparison 2. Vaginal misoprostol ‐ 6‐hourly versus 12‐hourly dosing interval.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours | 2 | 363 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.62, 1.22] |

| 2 Mean induction to birth interval | 1 | 53 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.70 [‐11.19, 1.79] |

| 3 Need for analgesia | 3 | 416 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.86, 1.42] |

| 4 Blood loss > 500 mL | 1 | 279 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.30, 5.81] |

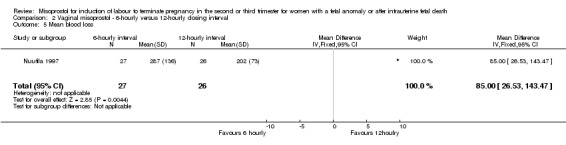

| 5 Mean blood loss | 1 | 53 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 85.0 [26.53, 143.47] |

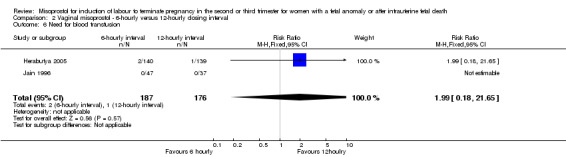

| 6 Need for blood transfusion | 2 | 363 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.99 [0.18, 21.65] |

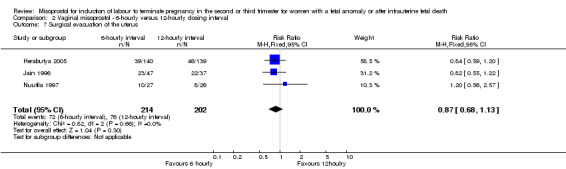

| 7 Surgical evacuation of the uterus | 3 | 416 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.68, 1.13] |

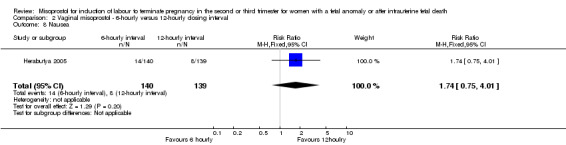

| 8 Nausea | 1 | 279 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.74 [0.75, 4.01] |

| 9 Vomiting | 3 | 416 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.26 [1.09, 4.71] |

| 10 Diarrhoea | 3 | 416 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.73, 1.86] |

| 11 Pyrexia | 2 | 363 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.81 [1.36, 2.42] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ 6‐hourly versus 12‐hourly dosing interval, Outcome 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ 6‐hourly versus 12‐hourly dosing interval, Outcome 2 Mean induction to birth interval.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ 6‐hourly versus 12‐hourly dosing interval, Outcome 3 Need for analgesia.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ 6‐hourly versus 12‐hourly dosing interval, Outcome 4 Blood loss > 500 mL.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ 6‐hourly versus 12‐hourly dosing interval, Outcome 5 Mean blood loss.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ 6‐hourly versus 12‐hourly dosing interval, Outcome 6 Need for blood transfusion.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ 6‐hourly versus 12‐hourly dosing interval, Outcome 7 Surgical evacuation of the uterus.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ 6‐hourly versus 12‐hourly dosing interval, Outcome 8 Nausea.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ 6‐hourly versus 12‐hourly dosing interval, Outcome 9 Vomiting.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ 6‐hourly versus 12‐hourly dosing interval, Outcome 10 Diarrhoea.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ 6‐hourly versus 12‐hourly dosing interval, Outcome 11 Pyrexia.

Comparison 3. Vaginal misoprostol versus Gemeprost (PGE1) (alone or with oxytocin).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours | 3 | 235 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.30 [0.64, 2.62] |

| 2 Mean induction to delivery interval | 2 | 109 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.22 [‐14.44, 18.87] |

| 3 Pain (VAS score greater than 5) | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.62, 1.38] |

| 4 Analgesia required | 2 | 135 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.42, 1.53] |

| 5 Mean blood loss | 1 | 55 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐61.0 [‐145.71, 23.71] |

| 6 Surgical evacuation of the uterus | 3 | 235 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.55, 1.03] |

| 7 Nausea | 2 | 154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.70, 1.86] |

| 8 Vomiting | 2 | 181 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.16, 4.62] |

| 9 Diarrhoea | 3 | 235 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.07, 3.15] |

| 10 Pyrexia | 2 | 154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.13, 1.06] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus Gemeprost (PGE1) (alone or with oxytocin), Outcome 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus Gemeprost (PGE1) (alone or with oxytocin), Outcome 2 Mean induction to delivery interval.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus Gemeprost (PGE1) (alone or with oxytocin), Outcome 3 Pain (VAS score greater than 5).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus Gemeprost (PGE1) (alone or with oxytocin), Outcome 4 Analgesia required.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus Gemeprost (PGE1) (alone or with oxytocin), Outcome 5 Mean blood loss.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus Gemeprost (PGE1) (alone or with oxytocin), Outcome 6 Surgical evacuation of the uterus.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus Gemeprost (PGE1) (alone or with oxytocin), Outcome 7 Nausea.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus Gemeprost (PGE1) (alone or with oxytocin), Outcome 8 Vomiting.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus Gemeprost (PGE1) (alone or with oxytocin), Outcome 9 Diarrhoea.

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus Gemeprost (PGE1) (alone or with oxytocin), Outcome 10 Pyrexia.

Comparison 4. Vaginal misoprostol versus PGE2 (alone or with other agents).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours | 4 | 251 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.36, 1.04] |

| 1.1 Low Dose Misoprostol | 2 | 109 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.44, 1.58] |

| 1.2 Moderate Dose Misoprostol | 1 | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.13, 2.00] |

| 1.3 High Dose Misoprostol | 1 | 126 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.10, 1.14] |

| 2 Mean induction to birth interval | 4 | 165 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.71 [‐10.05, 6.63] |

| 2.1 Low Dose Misoprostol | 3 | 149 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.00 [‐9.53, 7.53] |

| 2.2 Moderate Dose Misoprostol | 1 | 16 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐27.3 [‐76.57, 21.97] |

| 2.3 High Dose Misoprostol | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Analgesia required | 4 | 315 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.69, 1.11] |

| 5 Blood loss > 500 mL | 4 | 326 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.73 [0.69, 10.78] |

| 6 Need for blood transfusion | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Surgical evacuation of the uterus | 5 | 380 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.20, 1.36] |

| 8 Side effects ‐ any | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.59 [1.05, 2.40] |

| 9 Nausea | 1 | 126 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.35, 0.99] |

| 10 Vomiting | 4 | 254 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.31, 2.45] |

| 11 Diarrhoea | 3 | 261 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.06, 0.67] |

| 12 Pyrexia | 5 | 380 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.24, 3.20] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGE2 (alone or with other agents), Outcome 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGE2 (alone or with other agents), Outcome 2 Mean induction to birth interval.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGE2 (alone or with other agents), Outcome 4 Analgesia required.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGE2 (alone or with other agents), Outcome 5 Blood loss > 500 mL.

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGE2 (alone or with other agents), Outcome 6 Need for blood transfusion.

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGE2 (alone or with other agents), Outcome 7 Surgical evacuation of the uterus.

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGE2 (alone or with other agents), Outcome 8 Side effects ‐ any.

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGE2 (alone or with other agents), Outcome 9 Nausea.

4.10. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGE2 (alone or with other agents), Outcome 10 Vomiting.

4.11. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGE2 (alone or with other agents), Outcome 11 Diarrhoea.

4.12. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGE2 (alone or with other agents), Outcome 12 Pyrexia.

Comparison 5. Vaginal misoprostol versus PGF2alpha.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours | 3 | 213 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.28, 4.06] |

| 1.1 Low Dose Misoprostol | 2 | 91 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.02, 26.21] |

| 1.2 Moderate Dose Misoprostol | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.3 High Dose Misoprostol | 1 | 122 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.50, 1.58] |

| 2 Mean induction to birth interval | 4 | 378 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.84 [‐6.06, 0.38] |

| 2.1 Low Dose Misoprostol | 2 | 91 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.76 [‐11.03, 9.51] |

| 2.2 Moderate Dose Misoprostol | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.3 High Dose Misoprostol | 2 | 287 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.62 [‐5.71, ‐1.53] |

| 3 Blood loss > 500 mL | 1 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.22, 2.20] |

| 4 Need for blood transfusion | 2 | 131 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Surgical evacuation of the uterus | 5 | 439 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.41, 0.98] |

| 6 Side effects ‐ any | 1 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.41, 2.59] |

| 7 Nausea | 3 | 338 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.47, 0.95] |

| 8 Vomiting | 4 | 378 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.42, 0.89] |

| 9 Diarrhoea | 5 | 458 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.15, 1.82] |

| 10 Pyrexia | 5 | 458 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.14, 3.61] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 2 Mean induction to birth interval.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 3 Blood loss > 500 mL.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 4 Need for blood transfusion.

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 5 Surgical evacuation of the uterus.

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 6 Side effects ‐ any.

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 7 Nausea.

5.8. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 8 Vomiting.

5.9. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 9 Diarrhoea.

5.10. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 10 Pyrexia.

Comparison 6. Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and oxytocin.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mean induction to birth interval | 1 | 76 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [‐0.72, 10.72] |

| 2 Surgical evacuation of the uterus | 1 | 76 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.95 [0.98, 3.90] |

| 4 Vomiting | 1 | 76 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.35, 1.93] |

| 5 Diarrhoea | 1 | 76 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.08, 18.05] |

| 6 Pyrexia | 1 | 76 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.34 [0.77, 7.13] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and oxytocin, Outcome 1 Mean induction to birth interval.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and oxytocin, Outcome 2 Surgical evacuation of the uterus.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and oxytocin, Outcome 4 Vomiting.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and oxytocin, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea.

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and oxytocin, Outcome 6 Pyrexia.

Comparison 7. Vaginal misoprostol versus glyceryl tri‐nitrate.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Need for analgesia | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.22 [1.12, 4.40] |

| 3 Blood loss > 500 mL | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 15.0 [0.88, 255.78] |

| 4 Surgical evacuation of the uterus | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.0 [0.50, 162.89] |

| 5 Side effects ‐ any | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 75.0 [4.73, 1188.67] |

| 6 Vomiting | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 35.0 [2.16, 566.54] |

| 7 Diarrhoea | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.92] |

| 8 Pyrexia | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 31.0 [1.91, 504.35] |

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Vaginal misoprostol versus glyceryl tri‐nitrate, Outcome 2 Need for analgesia.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Vaginal misoprostol versus glyceryl tri‐nitrate, Outcome 3 Blood loss > 500 mL.

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Vaginal misoprostol versus glyceryl tri‐nitrate, Outcome 4 Surgical evacuation of the uterus.

7.5. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Vaginal misoprostol versus glyceryl tri‐nitrate, Outcome 5 Side effects ‐ any.

7.6. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Vaginal misoprostol versus glyceryl tri‐nitrate, Outcome 6 Vomiting.

7.7. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Vaginal misoprostol versus glyceryl tri‐nitrate, Outcome 7 Diarrhoea.

7.8. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Vaginal misoprostol versus glyceryl tri‐nitrate, Outcome 8 Pyrexia.

Comparison 8. Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and laminaria.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours | 1 | 68 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.47, 1.97] |

| 2 Blood loss > 500 mL | 1 | 68 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Need for blood transfusion | 1 | 68 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Vomiting | 1 | 68 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.13, 3.97] |

| 5 Diarrhoea | 1 | 68 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.35 [0.01, 8.37] |

| 6 Pyrexia | 1 | 68 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.03, 1.72] |

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and laminaria, Outcome 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and laminaria, Outcome 2 Blood loss > 500 mL.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and laminaria, Outcome 3 Need for blood transfusion.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and laminaria, Outcome 4 Vomiting.

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and laminaria, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea.

8.6. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and laminaria, Outcome 6 Pyrexia.

Comparison 9. Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and nitric oxide donor.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours | 1 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.34, 2.33] |

| 2 Mean induction to birth interval | 1 | 61 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.5 [‐8.01, 7.01] |

| 3 Side effects ‐ any | 1 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.17, 1.07] |

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and nitric oxide donor, Outcome 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and nitric oxide donor, Outcome 2 Mean induction to birth interval.

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol and nitric oxide donor, Outcome 3 Side effects ‐ any.

Comparison 10. Oral misoprostol versus PGF2alpha.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mean induction to birth interval | 1 | 133 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.40 [4.90, 13.90] |

| 2 Surgical evacuation of the uterus | 1 | 133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.36, 1.69] |

| 3 Nausea | 1 | 133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.56, 1.49] |

| 4 Vomiting | 1 | 133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.56, 1.49] |

| 5 Diarrhoea | 1 | 133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.60 [0.65, 10.41] |

| 6 Pyrexia | 1 | 133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.57, 2.86] |

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 1 Mean induction to birth interval.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 2 Surgical evacuation of the uterus.

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 3 Nausea.

10.4. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 4 Vomiting.

10.5. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea.

10.6. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol versus PGF2alpha, Outcome 6 Pyrexia.

Comparison 11. Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol alone.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.81 [0.60, 5.50] |

| 2 Mean induction to birth interval | 1 | 43 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.20 [3.42, 6.98] |

| 3 Need for analgesia | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.77, 1.39] |

| 5 Surgical evacuation of the uterus | 2 | 98 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.44, 1.57] |

| 6 Nausea | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Vomiting | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Diarrhoea | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours.

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 2 Mean induction to birth interval.

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 3 Need for analgesia.

11.5. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 5 Surgical evacuation of the uterus.

11.6. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 6 Nausea.

11.7. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 7 Vomiting.

11.8. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 8 Diarrhoea.

Comparison 12. Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol alone.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.47 [0.23, 0.96] |

| 2 Need for analgesia | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.82, 1.55] |

| 3 Surgical evacuation of the uterus | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.40, 1.85] |

| 4 Nausea | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Vomiting | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Diarrhoea | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.15 [0.01, 2.83] |

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol alone, Outcome 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours.

12.2. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol alone, Outcome 2 Need for analgesia.

12.3. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol alone, Outcome 3 Surgical evacuation of the uterus.

12.4. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol alone, Outcome 4 Nausea.

12.5. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol alone, Outcome 5 Vomiting.

12.6. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus oral misoprostol alone, Outcome 6 Diarrhoea.

Comparison 13. Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus dilation and evacuation.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Nausea | 1 | 18 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.56, 4.97] |

| 2 Vomiting | 1 | 18 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.48, 8.31] |

| 3 Diarrhoea | 1 | 18 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus dilation and evacuation, Outcome 1 Nausea.

13.2. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus dilation and evacuation, Outcome 2 Vomiting.

13.3. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Combined oral and vaginal misoprostol versus dilation and evacuation, Outcome 3 Diarrhoea.

Comparison 14. Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours | 2 | 202 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.08, 0.74] |

| 2 Induction to delivery interval | 2 | 202 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.81 [‐8.26, ‐1.37] |

| 3 Analgesic requirements | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.43, 2.31] |

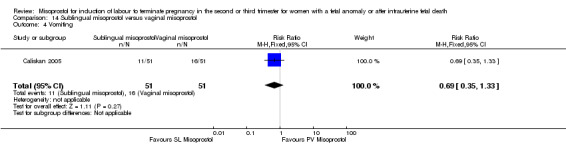

| 4 Vomiting | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.35, 1.33] |

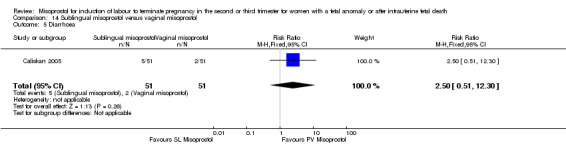

| 5 Diarrhoea | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.5 [0.51, 12.30] |

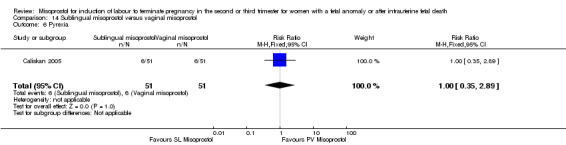

| 6 Pyrexia | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.35, 2.89] |

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours.

14.2. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 2 Induction to delivery interval.

14.3. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 3 Analgesic requirements.

14.4. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 4 Vomiting.

14.5. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea.

14.6. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 6 Pyrexia.

Comparison 15. Sublingual misoprostol versus oral misoprostol.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth not achieved within 24 hours | 2 | 204 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.22 [0.01, 4.99] |

| 2 Induction to delivery interval | 2 | 202 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐7.17 [‐13.73, ‐0.60] |

| 3 Analgesic requirements | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.31, 1.35] |

| 4 Vomiting | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.42, 1.71] |

| 5 Diarrhoea | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.27, 2.56] |

| 6 Pyrexia | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.6 [0.24, 1.53] |

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Sublingual misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 1 Vaginal birth not achieved within 24 hours.

15.2. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Sublingual misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 2 Induction to delivery interval.

15.3. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Sublingual misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 3 Analgesic requirements.

15.4. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Sublingual misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 4 Vomiting.

15.5. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Sublingual misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea.

15.6. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Sublingual misoprostol versus oral misoprostol, Outcome 6 Pyrexia.

Comparison 16. Sublingual misoprostol 100 mcg versus sublingual misoprostol 200 mcg.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Induction to delivery interval | 1 | 162 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.47 [‐2.94, 2.00] |

| 2 Vomiting | 1 | 162 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.23, 1.28] |

| 3 Diarrhoea | 1 | 162 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.21, 1.83] |

| 4 Pyrexia | 1 | 162 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.32, 1.29] |

16.1. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Sublingual misoprostol 100 mcg versus sublingual misoprostol 200 mcg, Outcome 1 Induction to delivery interval.

16.2. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Sublingual misoprostol 100 mcg versus sublingual misoprostol 200 mcg, Outcome 2 Vomiting.

16.3. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Sublingual misoprostol 100 mcg versus sublingual misoprostol 200 mcg, Outcome 3 Diarrhoea.

16.4. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Sublingual misoprostol 100 mcg versus sublingual misoprostol 200 mcg, Outcome 4 Pyrexia.

Comparison 17. Vaginal misoprostol ‐ low (< 800 mcg cumulative dose) versus moderate (800 mcg ‐2400 mcg cumulative dose).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.85 [1.13, 3.03] |

| 2 Pain (VAS score > 5) | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.47, 1.67] |

| 3 Need for analgesia | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.73, 1.10] |

| 4 Surgical evacuation of the uterus | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.33, 0.98] |

| 5 Nausea | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.59, 1.59] |

| 6 Vomiting | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.28, 1.17] |

| 7 Diarrhoea | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.26 [0.80, 6.39] |

| 8 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

17.1. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ low (< 800 mcg cumulative dose) versus moderate (800 mcg ‐2400 mcg cumulative dose), Outcome 1 Vaginal birth not achieved in 24 hours.

17.2. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ low (< 800 mcg cumulative dose) versus moderate (800 mcg ‐2400 mcg cumulative dose), Outcome 2 Pain (VAS score > 5).

17.3. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ low (< 800 mcg cumulative dose) versus moderate (800 mcg ‐2400 mcg cumulative dose), Outcome 3 Need for analgesia.

17.4. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ low (< 800 mcg cumulative dose) versus moderate (800 mcg ‐2400 mcg cumulative dose), Outcome 4 Surgical evacuation of the uterus.

17.5. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ low (< 800 mcg cumulative dose) versus moderate (800 mcg ‐2400 mcg cumulative dose), Outcome 5 Nausea.

17.6. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ low (< 800 mcg cumulative dose) versus moderate (800 mcg ‐2400 mcg cumulative dose), Outcome 6 Vomiting.

17.7. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ low (< 800 mcg cumulative dose) versus moderate (800 mcg ‐2400 mcg cumulative dose), Outcome 7 Diarrhoea.

Comparison 18. Vaginal misoprostol ‐ moderate dose (cumulative dose 2400 mcg) versus high dose (cumulative dose 3200 mcg).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mean induction to birth interval | 1 | 178 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.20 [1.36, 7.04] |

18.1. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Vaginal misoprostol ‐ moderate dose (cumulative dose 2400 mcg) versus high dose (cumulative dose 3200 mcg), Outcome 1 Mean induction to birth interval.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Akoury 2004.

| Methods | Trial conducted in Canada, January 1998‐February 2001. | |