Abstract

Background

Antidepressants are a first‐line treatment for adults with moderate to severe major depression. However, many people prescribed antidepressants for depression don't respond fully to such medication, and little evidence is available to inform the most appropriate 'next step' treatment for such patients, who may be referred to as having treatment‐resistant depression (TRD). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance suggests that the 'next step' for those who do not respond to antidepressants may include a change in the dose or type of antidepressant medication, the addition of another medication, or the start of psychotherapy. Different types of psychotherapies may be used for TRD; evidence on these treatments is available but has not been collated to date.

Along with the sister review of pharmacological therapies for TRD, this review summarises available evidence for the effectiveness of psychotherapies for adults (18 to 74 years) with TRD with the goal of establishing the best 'next step' for this group.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of psychotherapies for adults with TRD.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (until May 2016), along with CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO via OVID (until 16 May 2017). We also searched the World Health Organization (WHO) trials portal (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify unpublished and ongoing studies. There were no date or language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with participants aged 18 to 74 years diagnosed with unipolar depression that had not responded to minimum four weeks of antidepressant treatment at a recommended dose. We excluded studies of drug intolerance. Acceptable diagnoses of unipolar depression were based onthe Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV‐TR) or earlier versions, International Classification of Diseases (ICD)‐10, Feighner criteria, or Research Diagnostic Criteria. We included the following comparisons.

1. Any psychological therapy versus antidepressant treatment alone, or another psychological therapy.

2. Any psychological therapy given in addition to antidepressant medication versus antidepressant treatment alone, or a psychological therapy alone.

Primary outcomes required were change in depressive symptoms and number of dropouts from study or treatment (as a measure of acceptability).

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data, assessed risk of bias in duplicate, and resolved disagreements through discussion or consultation with a third person. We conducted random‐effects meta‐analyses when appropriate. We summarised continuous outcomes using mean differences (MDs) or standardised mean differences (SMDs), and dichotomous outcomes using risk ratios (RRs).

Main results

We included six trials (n = 698; most participants were women approximately 40 years of age). All studies evaluated psychotherapy plus usual care (with antidepressants) versus usual care (with antidepressants). Three studies addressed the addition of cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) to usual care (n = 522), and one each evaluated intensive short‐term dynamic psychotherapy (ISTDP) (n = 60), interpersonal therapy (IPT) (n = 34), or group dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) (n = 19) as the intervention. Most studies were small (except one trial of CBT was large), and all studies were at high risk of detection bias for the main outcome of self‐reported depressive symptoms.

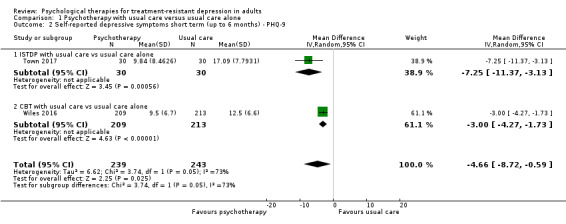

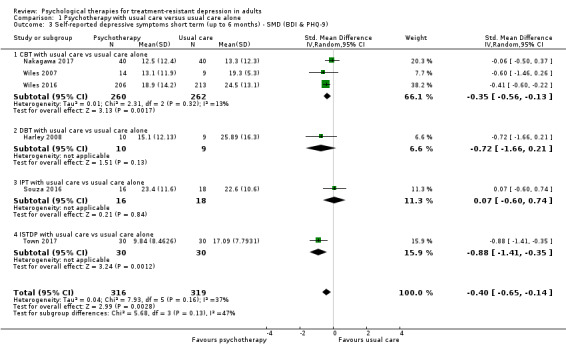

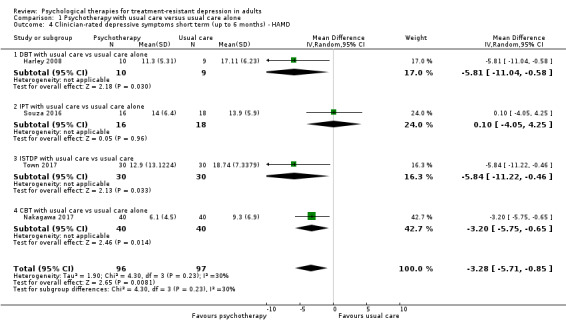

A random‐effects meta‐analysis of five trials (n = 575) showed that psychotherapy given in addition to usual care (vs usual care alone) produced improvement in self‐reported depressive symptoms (MD ‐4.07 points, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐7.07 to ‐1.07 on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scale) over the short term (up to six months). Effects were similar when data from all six studies were combined for self‐reported depressive symptoms (SMD ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐0.65 to ‐0.14; n = 635). The quality of this evidence was moderate. Similar moderate‐quality evidence of benefit was seen on the Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 Scale (PHQ‐9) from two studies (MD ‐4.66, 95% CI 8.72 to ‐0.59; n = 482) and on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) from four studies (MD ‐3.28, 95% CI ‐5.71 to ‐0.85; n = 193).

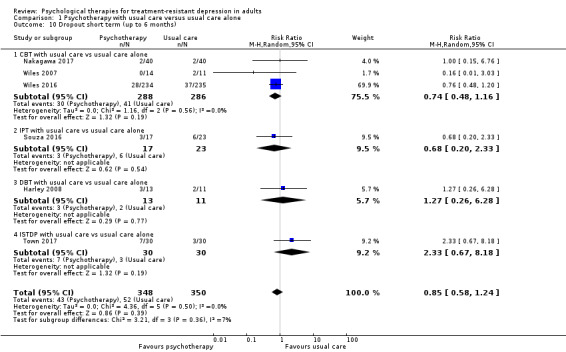

High‐quality evidence shows no differential dropout (a measure of acceptability) between intervention and comparator groups over the short term (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.24; six studies; n = 698).

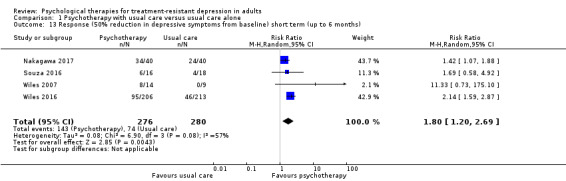

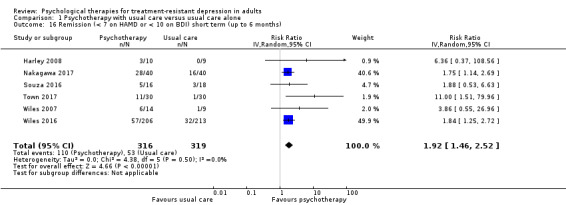

Moderate‐quality evidence for remission from six studies (RR 1.92, 95% CI 1.46 to 2.52; n = 635) and low‐quality evidence for response from four studies (RR 1.80, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.7; n = 556) indicate that psychotherapy was beneficial as an adjunct to usual care over the short term.

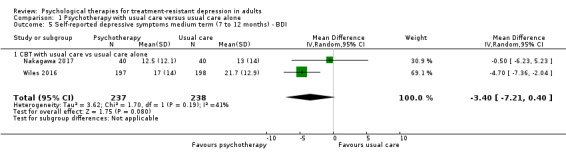

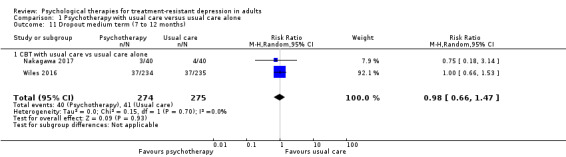

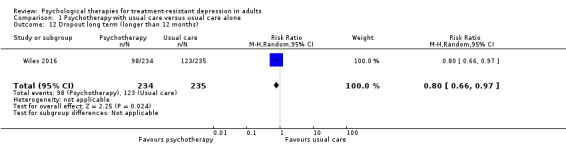

With the addition of CBT, low‐quality evidence suggests lower depression scores on the BDI scale over the medium term (12 months) (RR ‐3.40, 95% CI ‐7.21 to 0.40; two studies; n = 475) and over the long term (46 months) (RR ‐1.90, 95% CI ‐3.22 to ‐0.58; one study; n = 248). Moderate‐quality evidence for adjunctive CBT suggests no difference in acceptability (dropout) over the medium term (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.47; two studies; n = 549) and lower dropout over long term (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.97; one study; n = 248).

Two studies reported serious adverse events (one suicide, two hospitalisations, and two exacerbations of depression) in 4.2% of the total sample, which occurred only in the usual care group (no events in the intervention group).

An economic analysis (conducted as part of an included study) from the UK healthcare perspective (National Health Service (NHS)) revealed that adjunctive CBT was cost‐effective over nearly four years.

Authors' conclusions

Moderate‐quality evidence shows that psychotherapy added to usual care (with antidepressants) is beneficial for depressive symptoms and for response and remission rates over the short term for patients with TRD. Medium‐ and long‐term effects seem similarly beneficial, although most evidence was derived from a single large trial. Psychotherapy added to usual care seems as acceptable as usual care alone.

Further evidence is needed on the effectiveness of different types of psychotherapies for patients with TRD. No evidence currently shows whether switching to a psychotherapy is more beneficial for this patient group than continuing an antidepressant medication regimen. Addressing this evidence gap is an important goal for researchers.

Keywords: Adult; Aged; Female; Humans; Male; Middle Aged; Young Adult; Antidepressive Agents; Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Depression; Depression/therapy; Drug Resistance; Psychotherapy; Psychotherapy/methods; Psychotherapy, Group; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Are psychological therapies effective in treating depression that did not get better with previous treatment?

Review question

Is psychological therapy an effective treatment for adults with treatment‐resistant depression (TRD)?

Background

Depression is a common problem often treated with antidepressant medication. However, many people do not get better with antidepressants. These patients may be said to have TRD. For these people, several different treatments can be tried ‐ such as increasing the dose of medicine being taken, adding another medicine, or switching to a new one. Another option is to add or switch to a psychotherapy. Evidence indicates that psychotherapies can help in depression. What we don't know is whether psychotherapies work in people with TRD. This review aimed to answer this question.

Search date

Searches are current up to May 2017.

Study characteristics

We included six randomised trials (studies in which participants are allocated at random (by chance) to receive one of the treatments being compared). These trials included 698 people and tested three different types of psychotherapy. All studies looked at whether adding psychotherapy to current medical treatment leads to improvement in depression.

Study funding sources

All studies were funded by public research grants.

Key results

We found that patients who receive psychotherapy as well as usual care with antidepressants had fewer depressive symptoms and were more often depression‐free six months later compared with patients who continued with usual care alone. We are moderately confident of these findings, which means that the true effect of adding CBT may be different from what we found, although findings are likely to be close. We also found that added psychotherapy was as acceptable to patients as usual care alone. Two studies noted similar beneficial effects after 12 months, and one study at 46 months.

Two studies reported harmful effects in people receiving usual care alone (one suicide, two people hospitalised) but none in people receiving psychotherapy in addition to usual care.

Quality of the evidence

Because participants were aware of the treatment they had received, and because we identified only a small number of studies, we graded the evidence as moderate in quality for findings at six months and low in quality for long‐term results. This assessment might change in the future, if higher‐quality research results become available.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Psychotherapy as an adjunct to usual care compared with usual care alone for treatment‐resistant depression in adults ‐ short‐term effects.

| Psychotherapy as an adjunct to usual care compared with usual care alone for treatment‐resistant depression in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with treatment‐resistant depression Setting: primary or secondary care Intervention: psychotherapy with usual care Comparison: usual care alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with usual care alone | Risk with psychotherapy as an adjunct to usual care | |||||

| Self‐reported depressive symptoms short term (up to 6 months) ‐ BDI (BDI) | Mean depressive symptoms short term (up to 6 months) ‐ BDI was 21.1 | MD 4.07 lower (7.07 lower to 1.07 lower) | MD ‐4.07 (‐7.01 to ‐1.07) | 575 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa,b |

One large and 4 small studies comprising mainly women. Third‐wave cognitive/behavioural therapies given (individual CBT in 3 studies, group DBT in 1, and individual IPT in 1) |

| Self‐reported depressive symptoms short term (up to 6 months) ‐ SMD (BDI & PHQ9) | Mean depressive symptoms short term (up to 6 months) ‐ BDI was 21.1, and PHQ9 was 14.79 | SMD 0.4 SD lower (0.65 lower to 0.14 lower) | SMD ‐0.4 (‐0.65 to ‐0.14) | 635 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa,b |

All 6 studies combined |

| Observer‐rated depressive symptoms short term (up to 6 months) ‐ PHQ‐9 | Mean depressive symptoms short term (up to 6 months) ‐ PHQ‐9 was 14.8 | MD 4.66 lower (8.72 lower to 0.59 lower) | MD ‐4.66 (‐8.72 to ‐0.59) | 482 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa |

One large study from UK and one relatively small one from Canada |

| Observer‐rated depressive symptoms short term (up to 6 months) ‐ HAMD | Mean depressive symptoms short term (up to 6 months) ‐ HAMD was 14.76 | MD 3.28 lower (5.71 lower to 0.85 lower) | MD ‐3.28 (‐5.71 to ‐0.85) | 193 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

LOW c,d |

Although blinded outcome assessment, 4 small studies each using a different type of psychotherapy: group DBT; ISTDP; CBT; IPT |

| Dropout short term (up to 6 months) | Study population | RR 0.85 (0.58 to 1.24) | 698 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Objective outcome; data reported in all studies; Although a proxy for acceptability, it suggests that intervention may be as acceptable as usual care | |

| 149 per 1000 (14%) | 126 per 1000 (12.6%) (86 to 184) | |||||

| Response (50% reduction in depressive symptoms from baseline) short term (up to 6 months) | Study population | RR 1.80 (1.20 to 2.69) | 556 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,e |

‐ | |

| 264 per 1000 | 476 per 1000 (317 to 711) | |||||

| Remission (< 7 on HAMD or < 10 on BDI) short term (up to 6 months) | Study population | RR 1.92 (1.46 to 2.52) | 635 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa,b |

One large and 5 small studies comprising mainly women. Third‐wave cognitive/behavioural therapies given (individual CBT in 3 studies; individual IPT, ISTDP, and group DBT in 1 study each) | |

| 166 per 1000 | 319 per 1000 (243 to 419) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aOutcome assessment not blind.

bAllocation concealment unclear for one of the two smaller studies.

cRisk of bias due to incomplete outcome data in two of the studies.

dStudies are small. Effects not in the same direction for IPT study (n = 30).

eReporting bias likely as less frequently reported than remission or mean scores.

Summary of findings 2. Psychotherapy as an adjunct to usual care compared with usual care alone for treatment‐resistant depression in adults ‐ medium‐ to long‐term effects.

| Psychotherapy as an adjunct to usual care compared with usual care alone for treatment‐resistant depression in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with treatment‐resistant depression Setting: outpatient primary or secondary care Intervention: psychotherapy as an adjunct to usual care Comparison: usual care alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with usual care alone | Risk with psychotherapy as an adjunct to usual care | |||||

| Self‐reported depressive symptoms medium term (7 to 12 months) ‐ BDI | Mean depressive symptoms score at medium term ‐ BDI was 17.5 | MD 3.4 lower (7.21 lower to 0.4 higher) | ‐ | 475 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | Two studies (CBT): outcome assessment not blind as participants aware; wide confidence intervals |

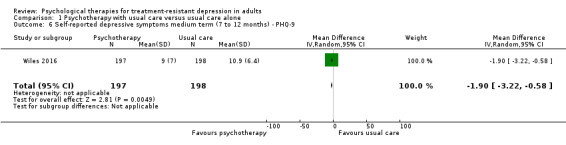

| Observer‐rated depressive symptoms medium term (7 to 12 months) ‐ PHQ‐9 | Mean depressive symptoms score at medium term ‐ BDI was 13 | MD 1.9 lower (3.22 lower to 0.58 lower) | ‐ | 395 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,c | Single study (CBT) |

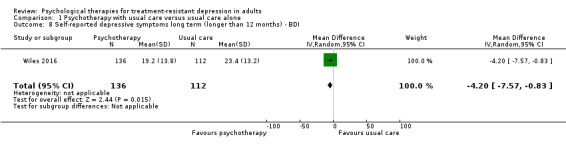

| Self (patient)‐reported depressive symptoms long term (longer than 12 months) ‐ BDI | Mean depressive symptoms score at long term ‐ BDI was 23.4 | MD 4.2 lower (7.57 lower to 0.83 lower) | ‐ | 248 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,c | 46‐Month results |

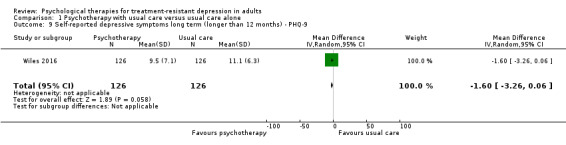

| Observer‐rated depressive symptoms long term (longer than 12 months) ‐ PHQ‐9 | Mean depressive symptoms score at long term ‐ BDI was 11.1 | MD 1.6 lower (3.26 lower to 0.06 higher) | ‐ | 252 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b,c | 46‐Month results |

| Dropout medium term (7 to 12 months)* | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.66 to 1.47) | 549 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEb | Two studies (CBT) | |

| 149 per 1000 | 146 per 1000 (98 to 219) | |||||

| Dropout long term (longer than 12 months)* | Study population | RR 0.80 (0.66 to 0.97) | 469 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWc,d | 46‐Month results | |

| 523 per 1000 | 419 per 1000 (345 to 508) | |||||

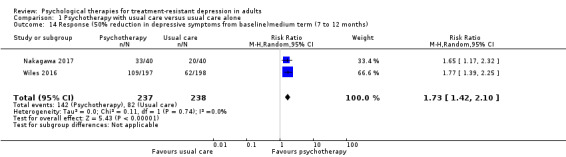

| Response (50% reduction in BDI) medium term (7 to 12 months)* | Study population | RR 1.73 (1.42 to 2.10) | 475 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,e | Two studies (CBT) | |

| 345 per 1000 | 434 per 1000 (489 to 724) | |||||

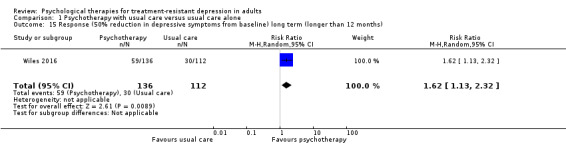

| Response (50% reduction in BDI) long term (longer than 12 months)* | Study population | RR 1.62 (1.13 to 2.32) | 248 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,c | 46‐Month results | |

| 268 per 1000 | 434 per 1000 (303 to 621) | |||||

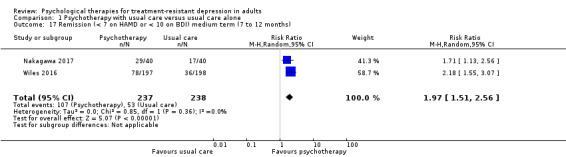

| Remission (< 7 on HAMD or < 10 on BDI) medium term (7 to 12 months)* | Study population | RR 1.97 (1.51 to 2.56) | 475 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa |

Two studies (CBT) | |

| 223 per 1000 | 439 per 1000 (336 to 570) | |||||

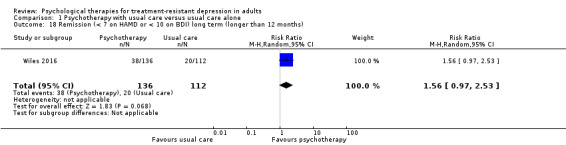

| Remission (< 7 on HAMD or < 10 on BDI) long term (longer than 12 months)* | Study population | RR 1.56 (0.97 to 2.53) | 248 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b,c | 46‐Month results | |

| 179 per 1000 | 279 per 1000 (173 to 452) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aOutcome assessment not blind.

bWide confidence intervals.

cSingle study data.

dResults at 46 months favour psychotherapy intervention when earlier results (6‐month and 12‐month) showed no difference.

eReporting bias likely as less frequently reported than remission or mean scores.

Background

Description of the condition

It has been predicted that depression will be the leading cause of disability in high‐income countries by the year 2030 (Mathers 2005). Severity of depression can be classified on the basis of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV), criteria as mild (five or more symptoms with minor functional impairment), moderate (symptoms or functional impairment between 'mild' and 'severe'), or severe (most symptoms present and interfering with functioning) (NICE 2009).

Antidepressants are often prescribed as first‐line treatment for adults with moderate to severe depression (APA 2010; NICE 2009). In England in 2010, 42.8 million prescriptions for antidepressants were issued at a cost of GBP220 million (The NHS Information Centre 2011). However, two‐thirds of people do not respond fully to such pharmacotherapy (Trivedi 2006). Such non‐response may result from intolerance to the prescribed medication or non‐adherence to the treatment regimen but may also indicate treatment 'resistance', whereby treatment of an adequate dose and duration has been given. The World Psychiatric Association provided the earliest definition of treatment‐'resistant' depression: "an absence of clinical response to treatment with a tricyclic antidepressant at a minimum dose of 150 mg per day of Imipramine (or equivalent drug) for 4 to 6 weeks" (WPA 1974). Subsequently, others suggested more complex classification systems based on non‐response to multiple courses of treatment (Fava 2005; Fekadu 2009; Thase 1997), using terms such as 'treatment‐refractory' depression and 'antidepressant‐resistant' depression to describe this condition. For the purpose of this review, we will use the term 'treatment‐resistant depression' as this is the descriptor that has generally represented the broadest definition of the condition.

The burden of depression is substantial, and in the UK the average service cost to the National Health Service (NHS) has been estimated as GBP2085 per patient (McCrone 2008). Total cost of services for depression in 2007 was estimated as GBP1.7 billion, although these costs were dwarfed by the cost of lost productivity, which accounted for a further GBP5.8 billion (McCrone 2008). Similar substantial costs have been estimated for the USA, with direct treatment costs estimated at USD26.1 billion and workplace costs at a further USD51.5 billion in the year 2000 (Greenberg 2003). If up to one‐third of patients have 'treatment‐resistant' depression, it is clear that this condition represents a considerable burden to patients, the NHS, and society.

Description of the intervention

First‐line treatment for adults with moderate to severe depression commonly consists of an antidepressant (APA 2010; NICE 2009). Five main types of antidepressants are available: tricyclic (TCAs) and related antidepressants; monoamine‐oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs); selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs); serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs); and noradrenergic and specific serotonin antidepressants (NaSSAs). SSRIs are safer in terms of overdose than TCAs and tend to be better tolerated than antidepressants of other classes. Hence, it is not surprising that SSRIs are the most commonly prescribed antidepressants for treating individuals with depression (Olfson 2009; The NHS Information Centre 2011).

No agreement has been reached on the standard approach for treatment of those whose depression does not respond to antidepressant medication. Guidance published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA 2010) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE 2009) suggests that the 'next step' may include increasing the dose of the antidepressant medication, switching to another antidepressant (within the same or in a different pharmacological class), or augmenting treatment via another pharmacological or psychological approach. Psychological therapies that may be given as an adjunct can be broadly categorised into four separate philosophical and theoretical schools: (1) psychodynamic/psychoanalytical (Freud 1949; Jung 1963; Klein 1960); (2) behavioural (Marks 1981; Skinner 1953; Watson 1924); (3) humanistic (Maslow 1943; May 1961; Rogers 1951); and (4) cognitive (Beck 1979; Lazarus 1971). In addition, 'third wave' (Hayes 2004; Hayes 2006; Hofmann 2008) and 'integrative' (Hollanders 2007; Klerman 1984; McCullough 1984; Ryle 1990; Shapiro 1990; Weissman 2007) psychological approaches may be used. Elements of these approaches may overlap or may differ. For example, cognitive‐analytical therapy (CAT) incorporates elements from several theoretical schools (Ryle 1990), whereas interpersonal therapy for depression (IPT) is disorder‐specific (Klerman 1984). The most influential cognitive approaches have been merged with the behavioural approach to form cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) (Beck 1979; Ellis 1962), which is now viewed as a family of therapies that draw upon a common base of cognitive and behavioural models of psychological disorders (Mansell 2008).

How the intervention might work

Psychological therapies such as CBT have been shown to be effective for people with depression (Churchill 2001). When a psychological therapy is given as an adjunct to pharmacological treatment, it is hoped that the benefits gained from these different treatment approaches may be optimised. Mechanisms of action differ among psychological therapies. Cognitive‐behavioural therapy targets the person's unrealistic and unhelpful negative thoughts ("dysfunctional attitudes") to improve outcomes, whereas behavioural therapy focuses on changing maladaptive patterns of behaviour. In contrast, humanistic therapy seeks to increase an individual's self‐awareness, and psychodynamic therapy focuses on past experiences and an understanding of how these events might have influenced the individual and his or her current thoughts and behaviours.

Why it is important to do this review

Antidepressants continue to serve as first‐line treatment for many people with depression. However, only one‐third of people prescribed antidepressants for depression will respond fully to such medication (Trivedi 2006). Evidence suggests that people may prefer pyschotherapy to medication for depression (McHugh 2013). Therefore, summarising the evidence for effectiveness of psychological therapies for people with treatment‐resistant depression (TRD) is important toward establishing the best 'next step' treatment for this patient group.

Several traditional reviews have examined the evidence on treatment of people whose depression has not responded to antidepressant medication alone (e.g. Carvalho 2008; Nierenberg 2007; Papakostas 2009). Systematic reviews on the effectiveness of combination treatment for people with depression have not examined evidence for the treatment‐resistant population (Friedman 2004; Pampallona 2004). Others have summarised the evidence for effectiveness of particular treatment strategies for those who have not responded to antidepressants: (1) augmentation as discussed in Carvalho 2007 with lithium ‐ Bauer 1999 ‐ or atypical antipsychotics ‐ Shelton 2008; (2) within‐ or between‐class switches (Papakostas 2008); and (3) psychological treatments (McPherson 2005). One review focused on interventions for older people (≥ 55 years of age) (Cooper 2011). However, several of these reviews included uncontrolled studies, non‐randomised studies, or a combination of these, as well as randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Carvalho 2007; Cooper 2011; McPherson 2005; Shelton 2008).

A previous systematic review of RCTs investigating pharmacological and psychological therapies for people with TRD found no strong evidence to guide the management of such people (Stimpson 2002). However, this review, along with others (e.g. Bauer 1999, which summarised the evidence for lithium up to June 1997), is out‐of‐date, and several relevant RCTs were published subsequently. Another review of psychotherapies for TRD included four controlled studies of CBT (McPherson 2005); two studies showed benefit derived from CBT, and two found no difference between psychotherapy and control.

No agreement has been reached on the definition of 'treatment‐resistant depression'. Many studies have defined TRD as 'failure to respond to at least two previous antidepressants'. Given continued reliance upon antidepressants as first‐line treatment, we have used a broader and more inclusive definition of treatment resistance ‐ 'non‐response to at least four weeks of antidepressant medication' ‐ to help establish the best 'next step' of treatment for the significant number of people whose depression does not respond to antidepressant medication. The rise in antidepressant prescribing along with increased demand for psychotherapy in recent years (BACP, 2014; McManus 2000; Middleton 2001; Pincus 1998) means that a review of the evidence for effectiveness of psychological therapies for people with TRD is timely. A connected review is examining pharmacological interventions for TRD (Williams 2013). Together, evidence from these two linked reviews will provide a comprehensive evidence base of the main interventions available for management of TRD, which will inform clinical decision‐making with regards to the best 'next step' for adults whose depression has not responded to first‐line treatment with medication.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of psychotherapies for adults with TRD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

This review includes RCTs and cluster RCTs.

This review includes trials using a cross‐over design but only data from the first treatment phase.

Excluded from this review are trials of any other study design, including quasi‐randomised studies and non‐randomised studies.

Types of participants

Age range

Participants must be 18 to 74 years of age.

We excluded any study that included some participants younger than 75 years and some older than 74 years if the mean age of participants was over 74 years. Similarly, we excluded any study that included some participants younger than 18 years and some older than 18 years if the mean age of participants was less than 18 years.

Definition of treatment‐resistant depression

We defined treatment resitsant depression as "A primary diagnosis of unipolar depression that has not responded (or has only partially responded) to a minimum of four weeks of antidepressant treatment at a recommended dose (at least 150 mg/d imipramine or equivalent antidepressant (e.g. 20 mg/d citalopram))."

We excluded studies that included people who had not responded because of intolerance of antidepressant medication.

Although initiatives have sought to improve access to psychological therapies in England and elsewhere, access to psychological treatment remains limited and antidepressants are often given as first‐line treatment for adults with depression. Therefore, this review does not include studies of interventions intended for those who have not responded to psychological treatment.

Diagnosis

Acceptable diagnoses of unipolar depression include those based on criteria from DSM‐IV‐TR or earlier versions of this publication (APA 2000), International Classification of Diseases (ICD)‐10 (WHO 1992), Feighner criteria (Feighner 1972), or Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer 1978). We excluded studies that did not use standardised diagnostic criteria.

Comorbidities

Excluded from this review are studies of participants with comorbid schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

Also excluded are studies including participants with both unipolar and bipolar depression unless data are available for the subgroup of unipolar participants.

This review includes studies involving participants with comorbid physical conditions or other psychological disorders (e.g. anxiety) for whom psychological therapy was not being primarily used to manage the physical illness, in other words, the focus of treatment was TRD ‐ not the comorbidity.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

Any psychological therapy provided as monotherapy, that is, the intervention comprised only a psychological therapy.

Any psychological therapy provided as an adjunct to antidepressant therapy, that is, the intervention was given in addition to an antidepressant.

We grouped psychological therapies into (1) psychodynamic/psychoanalytical; (2) cognitive‐behavioural; (3) humanistic; and (4) integrated therapies. The 'integrated therapies' category includes integrative therapies such as IPT and CAT, which involve components of different psychological therapy models. Group 2 includes 'third wave' cognitive‐behavioural therapy‐based approaches.

Comparator interventions

An antidepressant that is included in one of five main types: TCAs, MAOIs, SSRIs, SNRIs, and NaSSAs.

Another psychological therapy ‐ grouped as above.

An attentional control providing the same level of support and attention from a practitioner (as is received by those in the experimental intervention arm) but not containing any of the key 'active' ingredients of the experimental intervention.

The authors of another review have included studies examining pharmacological interventions for individuals with TRD (Williams 2013).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Change in depressive symptoms as measured on rating scales for depression, either

Clinician‐rated depressive symptoms (e.g. Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) ‐ Hamilton 1960; Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) ‐ Montgomery 1979), or

Self‐reported depressive symptoms (e.g. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) ‐ Beck 1961; Beck 1996; other validated measures). We analysed data on observer‐rated and self‐reported outcomes separately.

2. Number of dropouts from study or treatment (all‐cause dropout) within trials.

When available, we collected data on reasons for dropout and summarised them in narrative form.

Secondary outcomes

3. Response or remission rates, or both, based on changes in depression measures ‐ either clinician‐rated (e.g. HAMD ‐ Hamilton 1960) or self‐report (e.g. BDI ‐ Beck 1961; Beck 1996) or other validated measures. Response is frequently quantified as at least a 50% reduction in symptoms on HAMD or BDI, but we accepted the study's original definition. Remission is based on the absolute score on the depression measure. Examples of definitions of remission include scores of 7 or less on the HAMD and 10 or less on the BDI. Again, we accepted the study authors' original definition

4. When available, we summarised in narrative form data on improvements in social adjustment and social functioning including Global Assessment of Function scores, as provided in Luborsky 1962

5. When available, we summarised in narrative form data on improvement in quality of life as measured on Short Form (SF)‐36 (Ware 1993), Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) (Wing 1994), or World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL ‐ WHOQOL 1998) or similar scales

6. When reported, we summarised in narrative form economic outcomes, for example, days of work absence/ability to return to work, number of appointments with primary care physician, number of referrals to secondary services, and use of additional treatments

7. When reported, we summarised in narrative form data on adverse effects, for example, completed/attempted suicides

Timing of outcome assessment

We summarised outcomes at each reported follow‐up point. When appropriate, and when the data allowed, we categorised outcomes as short term (up to six months), medium term (seven to 12 months post treatment), and long term (longer than 12 months).

Search methods for identification of studies

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR)

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group (CCMD) maintains two archived clinical trials registers at its editorial base in York, UK: a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCMDCTR‐References Register contains over 40,000 reports of RCTs examining depression, anxiety, and neurosis. Approximately 50% of these references have been tagged to individual coded trials. Coded trials are held in the CCMDCTR‐Studies Register, and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual, which uses a controlled vocabulary (please contact the CCMD Information Specialist for further details). Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group's registers are collated from routine (weekly) generic searches of MEDLINE (1950 to 2016), Embase (1974 to 2016), and PsycINFO (1967 to 2016); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trials registers via the World Health Organization trials portal (International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)), pharmaceutical companies, handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings, and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Details of CCMD's generic search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website. The Group’s Specialised Register had fallen out of date with the Editorial Group’s move from Bristol to York in the summer of 2016.

Electronic searches

We searched the CCMDCTR‐Studies Register using the following terms: Condition = ((depressi* or "affective disorder" or "mood disorder*") and ("treatment‐resistant" or recurrent))

We searched the CCMDCTR‐References Register using a more sensitive set of terms (keywords and subject headings) to identify additional untagged/uncoded references:

1. depressi* [Ti, Ab, KW] 2. (*refractory* or *resistan* or *recurren*) [Ti, Ab] 3. (augment* or potentiat*) [Ti, Ab] 4. (chronicity or "chronic depress*" or "chronically depress*" or "depressed chronic*" or "chronic major depressi*" or "chronic affective disorder*" or "chronic mood disorder*" or (chronic* and (relaps* or recurr*))) [Ti, Ab, KW] 5. ("persistent depress*" or "persistently depress*" or "depression persist*" or "persistent major depress*" or "persistence of depress*" or "persistence of major depress*") [Ti, Ab] 6. (nonrespon* or non‐respon* or "non respon*" or "not respon*" or "no respon*" or "partial respon*" or "partially respon*" or "incomplete respon*" or "incompletely respon*" or unrespon*) [Ti, Ab] 7. ("failed to respond" or "failed to improve" or "failure to respon*" or "failure to improve" or "failed medication*" or "antidepressant fail*" or "treatment fail*") [Ti, Ab] 8. (inadequate* and respon*) [Ti, Ab] 9. "treatment‐resistant depression" [KW] 10. (recurrence or "recurrent depression" or "recurrent disease") [KW] 11. "drug resistance" [KW] 12. "treatment failure" [KW] 13. "drug potentiation" [KW] 14. augmentation [KW] 15. or/2‐14 16. (1 and 15)

We applied no date or language restrictions to our search. Our search of the CCMDCTR was up‐to‐date as of 18 March 2016.

We ran additional searches via the following biomedical databases (1 January 2016 to 16 May 2017) (Appendix 1):

Medline/Premedline = 553

Embase = 546

CENTRAL = 477

Psychinfo = 246

Web of Science = 673

We used the term 'treatment‐resistant' or 'treatment refractory' depression to search international trials registries, including the WHO trials portal (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov (to 30 June 2017) (Appendix 1), to identify any additional ongoing and unpublished studies. We contacted Principal Investigators, when necessary, to request further details of ongoing/unpublished studies or trials reported as conference abstracts only. These searches are up‐to‐date until 30 June 2017.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of all included studies and other relevant systematic reviews for studies that may meet review inclusion criteria. We contacted subject experts to ensure that we had considered for inclusion all relevant published and unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (NW or PD or SI) examined titles and abstracts and removed obviously irrelevant reports, then screened study abstracts against inclusion criteria using a standardised abstract screening form. In any case of uncertainty, an over‐inclusive approach was taken and the full paper was obtained, along with full papers for studies assessed as meeting the inclusion criteria. Two review authors screened each paper for inclusion or exclusion from the review. If any disagreements arose, these were discussed with a third review author. If it was not possible to determine eligibility for a study, review authors added that study to the list of those awaiting assessment and contacted trial authors to request further information or clarification.

Review authors documented the study selection process using a PRISMA study selection flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors used a standardised data extraction form to independently extract data regarding participants, interventions and their comparators, methodological details, treatment effects including dropouts, and possible biases. If any disagreements arose, they discussed these with a third review author. The data extraction form was piloted during the first phase of data extraction.

Review authors abstracted information related to study populations, definition of TRD, sample size, interventions, comparators, potential biases in conduct of the trial, outcomes, follow‐up, and methods of statistical analysis.

Main planned comparisons

Any psychological therapy versus antidepressant treatment alone.

Any psychological therapy versus another psychological therapy.

Any psychological therapy given in addition to antidepressant medication versus antidepressant treatment alone.

Any psychological therapy given in addition to antidepressant medication versus a psychological therapy alone.

Any psychological therapy versus an attention control.

For comparison 2, review authors grouped the different types of psychological therapies according to the list given earlier.

If we identified enough studies, we planned to pool the evidence for CBT, IPT, CAT, etc., individually within various categories for comparisons 1, 3, and 4.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each included study using the 'Risk of bias' tool of the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2017). We discussed any disagreements with a third review author. We assessed the following criteria.

Sequence generation: Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Allocation concealment: Was allocation adequately concealed?

Blinding of participants, study personnel, and outcome assessors for each outcome: Was knowledge of the allocated treatment adequately prevented during the study?

Incomplete outcome data for each main outcome or class of outcomes: Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

Selective outcome reporting: Were reports of the study free of the suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Other sources of bias: Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at high risk of bias? For example, not reporting baseline numbers, describing differential attrition, following up only on people who continued taking medication.

Review authors extracted a description of what was reported to have happened in each study and judged risk of bias for each domain within and across studies, based on the following three categories: low risk of bias; unclear risk of bias; and high risk of bias.

When studies provided few or no details about the process of randomisation, review authors contacted trial authors to seek clarification.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed continuous outcomes by calculating the mean difference (MD) between groups if studies used the same outcome measure for comparison. If studies used different outcome measures to assess the same outcome, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The SMD can be interpreted as follows: 0.2 represents a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect (Cohen 1988).

We calculated risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous outcomes. When overall risks were significant, we planned to calculate the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) to produce one outcome by combining the overall RR with an estimate of prevalence of the event in the control groups of trials.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We planned to incorporate results from cluster RCTs into the review using generic inverse variance methods (Higgins 2011). With cluster RCTs, it is important to ensure that data were analysed with consideration of their clustered nature. The intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) for each trial was to be extracted. When no such data were reported, we planned to request them from study authors. If these data were not available, in line with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), we planned to use estimates from similar studies to 'correct' data for clustering when this had not been done.

Cross‐over trials

For cross‐over trials, we planned to include in the analysis only results from the first randomised treatment period.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

Studies that include more than two arms (e.g. psychological intervention (A); psychological intervention (B); and control) can cause problems in pair‐wise meta‐analysis. For studies with two or more active treatment arms, we undertook the following approach according to whether the outcome was continuous or dichotomous.

For a continuous outcome: We pooled means, standard deviations (SDs), and the number of participants for each active treatment group across treatment arms as a function of the number of participants in each arm for comparison against the control group (Higgins 2011).

For a dichotomous outcome: We planned to combine active treatment groups into a single arm for comparison against the control group (in terms of numbers of people with events and sample sizes) or to split the control group equally (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to request data when missing. If an outcome was missing for more than 50% of participants, we excluded this study from the analysis. When available, we used intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses from the study reports and wrote to study authors to request relevant unreported analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using the Chi² test, which provides evidence of variation in effect estimates beyond that of chance. The Chi² test has low power to assess heterogeneity when included studies are few or numbers of participants small; so we set the P value conservatively at 0.1. We also quantified heterogeneity using the I² statistic, which calculates the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance. We expected, a priori, that clinical heterogeneity between studies would be considerable; therefore we considered I² values between 50% and 90% to represent substantial statistical heterogeneity that would need to be explored further.

Assessment of reporting biases

We managed reporting bias by undertaking comprehensive searches for papers in all languages and studies outside the peer‐reviewed domain. We determined outcome reporting bias for all included studies and sought trial protocols whenever possible. If outcome data were missing, we requested these from trial authors.

We had planned to use funnel plots to help detect reporting biases and to conduct formal testing for small‐study effects using the Egger test (Egger 1997) if 10 or more studies were included in the review (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

Given the potential for heterogeneity in the included interventions, we used a random‐effects model for all analyses.

This approach incorporates the assumption that different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects and takes into account differences between studies even if no statistically significant heterogeneity is found. We tested heterogeneity formally using both the Chi² test and the I² statistic (as outlined above). We sought clinical advice regarding combining treatment groups to ensure that findings were clinically meaningful.

When a meta‐analysis was not possible (e.g. owing to insufficient data or substantial heterogeneity), we provided a narrative assessment of the evidence in which we summarised the evidence according to intervention type.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

A priori, we considered the degree of treatment resistance recorded at the point of entry to the trial a potential effect modifier. Therefore we planned the following subgroup analyses (based on two variables).

Severity of depression: classifying participants as 'non‐responders' or 'partial responders' at baseline

Length of acute treatment phase (before trial entry): four weeks or longer, 12 weeks or longer, or six months or longer

We planned to conduct such subgroup analyses when we had obtained data from at least 10 included studies (Higgins 2011).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to explore how much of the variation between studies comparing psychological therapies for TRD was accounted for by between‐study differences in:

study quality: allocation concealment used as a marker of trial quality; studies that have not used allocation concealment were excluded;

attrition: studies with more than 20% dropout excluded;

missing data: studies that have imputed missing data excluded;

treatment fidelity: studies that have not measured treatment fidelity of the psychological model excluded; or

publication type: studies that have not been published in full (conference abstracts/proceedings, doctoral dissertations) excluded.

'Summary of findings' table

In the original protocol, we stated that we would produce 'Summary of findings' (SoF) tables for all relevant comparisons. However, the current recommendation to Cochrane review authors is that they select one 'primary' time point that they will report for all outcomes in the SoF tables. Following this, we present the short‐term outcome in the SoF table.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

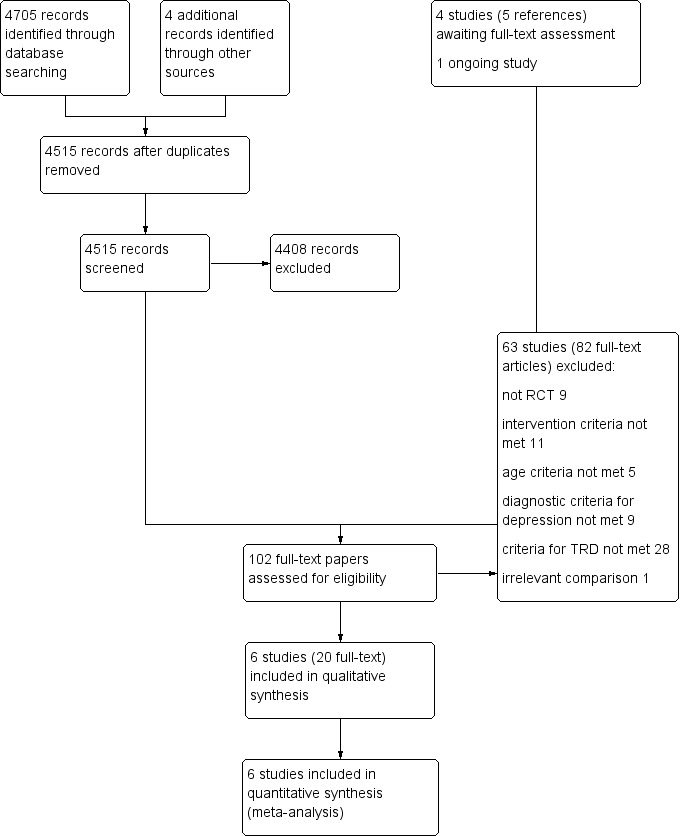

We found 4705 records via our electronic searches. We located four further papers through complementary searches of references and study author contacts. After removing duplicates, we screened 4515 titles and abstracts, of which we excluded 4408. However, four studies (five references) are still awaiting full‐text assessment (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification) as, to date, we could not obtain full‐text papers and we identified one ongoing study (Characteristics of ongoing studies), for which a full paper is not yet available. We therefore screened 102 full‐text articles. We excluded 82 articles (pertaining to 63 studies) and provided reasons for exclusion in Figure 1; we presented additional details under Characteristics of excluded studies. We included in this review 20 full‐text articles pertaining to six studies. All six studies contributed data to meta‐analyses. We contacted the authors of all included studies with regards to points of clarification and received a response from five of the six. We also contacted two of the authors of excluded studies to request clarification on methods and received a response from one.

1.

Study flow diagram.

We have presented details of study flow in a PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1.

Included studies

Six studies met all of our inclusion criteria, and we included them in this review (see Characteristics of included studies) (Harley 2008; Nakagawa 2017; Souza 2016; Town 2017; Wiles 2007; Wiles 2016).

Design

All six studies were parallel‐group randomised trials conducted to compare the effectiveness of psychotherapy as an adjunct to usual care that included antidepressant medication versus usual care alone.

Sample size

Three of the six studies were small, recruiting fewer than 50 participants in total (Harley 2008; Souza 2016; Wiles 2007). Only one study was a large multi‐centre RCT with a total of 469 participants randomised between two groups (Wiles 2016).

Setting

Two studies were reported from the same UK research group, which recruited participants from general practices (primary care) (Wiles 2007; Wiles 2016). The other four studies recruited participants from the psychiatric outpatient departments of hospitals (secondary care) and were conducted in the USA (Harley 2008), Canada (Town 2017), Japan (Nakagawa 2017), and Brazil (Souza 2016).

Participants

The mean age of participants in these studies ranged from 40.6 years ‐ in Nakagawa 2017 ‐ to 49.3 years ‐ in Souza 2016 ‐ and most participants were women (63.3% in Town 2017 to 85% in Souza 2016); Nakagawa 2017 was the only study that recruited more male than female participants (36%).

Interventions

All included studies addressed the same comparison: psychotherapy as adjunct to usual care (including antidepressants) compared with usual care alone. Trialists studied four types of psychotherapies: cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT); dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT); interpersonal therapy (IPT); and Intensive short‐term dynamic psychotherapy (ISTDP).

Three studies ‐ one from Japan ‐ Nakagawa 2017 ‐ and two from the UK ‐ Wiles 2007 and Wiles 2016 ‐ evaluated individual cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) for depression using the model proposed by Beck et al (Beck 1979). The number of sessions was similar across these studies: 16 to 20 sessions in Nakagawa 2017, 12 to 20 sessions in Wiles 2007, and 12 to 18 sessions in Wiles 2016. In the two UK studies, sessions lasted up to an hour and were provided by trained and supervised therapists representative of the NHS psychological therapy services (two therapists delivered CBT in Wiles 2007, and 11 part‐time therapists delivered treatment in Wiles 2016). In the Japanese study, individual sessions were 50 minutes in duration and were provided by four trained and supervised psychiatrists, one clinical psychologist, and one psychiatric nurse. In all three studies, patients in both groups continued to receive usual care from their treating doctors as needed during the study. Participants were expected to continue taking antidepressant medication as part of usual care.

Harley 2008 studied group dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), which shares key elements of CBT, namely, change‐oriented cognitive‐behavioural strategies. Participants received 16 weekly sessions, each lasting 1.5 hours, with weekly between‐session homework assignments. The group was run by two clinical psychologists, both of whom had received DBT training and had at least 7 years experience of leading DBT skills groups.

Souza 2016 evaluated interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) as an adjunct to usual care. Participants received 16 individual weekly sessions, each 40 minutes in duration. One psychiatrist and one third‐year psychiatry resident delivered therapy sessions. A senior IPT therapist supervised the sessions weekly.

Town 2017 studied Intensive short‐term dynamic psychotherapy (ISTDP) ‐ a brief psychotherapy format tailored to the patient's anxiety tolerance that helps the patient identify and address emotional factors that culminate into, exacerbate, and perpetuate depression.

Intervention engagement

In the pilot study of CBT (Wiles 2007), participants attended, on average (median), 9.5 sessions (interquartile range (IQR) 2, 12]. In the US study of DBT (Harley 2008), participants did not attend, on average, 1.8 out of 16 sessions (range 0 to 3). In the large UK multi‐centre trial (Wiles 2016), participants received an average (median) of 12 sessions of CBT (IQR 6 to 17) by 12‐month follow‐up. In total, 141 participants (60.3%) received at least 12 sessions of CBT, and the average duration of therapy was 6.3 months (SD 3.0). In Nakagawa 2017, the mean number of sessions completed was 15 (SD 3), with 97.5% of participants completing the CBT course.

Participants in the Brazilian study received on average 11 sessions of IPT, with 70% participants receiving at least eight sessions (Souza 2016). Harley 2008 reported no information on the number of sessions. The mean number of sessions completed in Town 2017 was 16.1 (SD 6.68), and 72% (n = 24) of participants received at least 15 sessions of ISTDP.

Intervention fidelity

Four studies also assessed the fidelity of the intervention to the respective psychotherapy models (CBT and ISTDP) using a validated rating scale completed by independent raters (Nakagawa 2017; Town 2017; Wiles 2007; Wiles 2016).

Primary outcomes

Change in depressive symptoms

All included studies reported the main outcome of change in depressive symptoms. All six studies reported short‐term follow‐up. Two studies reported medium‐term follow‐up (7 to 12 months) (Nakagawa 2017; Wiles 2016), and one study reported long‐term (longer than 12 months) follow‐up (Wiles 2016).

Five recorded outcomes using the self‐report BDI scale. Three studies used BDI version II (Beck 1996) (Nakagawa 2017; Wiles 2007; Wiles 2016), and two studies used BDI version I (Beck 1961) (Harley 2008; Souza 2016).

Two studies also reported change in depressive symptoms on the HAMD scale (Harley 2008: Souza 2016), and Town 2017 reported HAMD‐GRID change scores.

Two studies also reported change in depressive symptoms on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)‐9 scale (Town 2017: Wiles 2016).

Number of dropouts

All trials reported the number of dropouts by group. When reported, the most common reason for dropout was inability to contact the participant, followed by withdrawal from treatment. All reported reasons are listed in Table 3 by study and group allocation.

1. Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone ‐ reasons for dropout.

| Study ID | Total N randomised | Follow‐up time point, months | Reason for dropout given in Intervention group (psychotherapy as an adjunct to usual care) | Reason for dropout given in control group (usual care alone) |

| Harley 2008 | 24 | 4 | 1 difficulty finding child care; 1 work schedule conflict; 1 decided group was not a good fit | 1 moved; 1 medical problem |

| Wiles 2016 | 469 | 6 | 25 not followed up 14 withdrew from study 6 lost to follow‐up 4 unable to contact 1 died | 22 not followed up 13 withdrew from study 6 lost to follow‐up 3 unable to contact |

| 12 | 36 not followed up 17 withdrew from study 17 lost to follow‐up 2 died | 37 not followed up 15 withdrew from study 22 lost to follow‐up | ||

| Wiles 2007 | 25 | 4 | NA | 2 lost to follow‐up |

| Nakagawa 2017 | 80 | 6 | 1 not contactable; 1 patient discontinued because of lumbago | 1 not contactable; patient discontinued owing to family health problem |

| 12 | 1 not contactable | 1 not contactable; 1 died | ||

| Town 2017 | 60 | 6 | 2 did not start therapy; 3 not contactable; 2 withdrew | 3 not contactable |

N: number

NA: not available

Secondary outcomes

Response or remission rates

All six studies measured remission. Three studies defined remission as participants scoring less than 7 on the HAMD scale (Harley 2008: Souza 2016: Town 2017); Nakagawa 2017 defined it as scoring less than 7 on the HAMD‐GRID; and Wiles 2007 and Wiles 2016 defined remission as scoring less than 10 on the BDI‐II.

Four studies measured response (Nakagawa 2017; Souza 2016; Wiles 2007: Wiles 2016). Both UK studies defined response as a reduction in BDI‐II score of at least 50% compared with baseline (Wiles 2007; Wiles 2016). Nakagawa 2017 and Souza 2016 defined response as a 50% reduction on the HAMD and HAMD‐GRID scales, respectively.

Social adjustment and social functioning

Only one trial reported social functioning, which was measured on SAS work and LIFE work scales (Harley 2008). See Table 4.

2. Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone for social functioning.

| Study ID | Measure | N psychotherapy + usual care |

Final mean psych + usual care | SD psych + usual care | N usual care |

Final mean usual care |

SD usual care |

Effect size (Cohen's D)a | Significance (as reported in the study) |

| Harley 2008 | SAS workb | 10 | 65.7 | 19.27 | 9 | 69.56 | 17.66 | 1.60 | P < 0.05 |

| Harley 2008 | LIFE workb | 10 | 2.7 | 1.34 | 9 | 3.11 | 1.69 | 0.56 | Not significant |

| Harley 2008 | SAS social or leisureb | 10 | 64.30 | 12.91 | 9 | 72.56 | 16.21 | 0.77 | Not significant |

| Harley 2008 | LIFE recreationb | 10 | 2.7 | 1.06 | 9 | 3 | 1.19 | 0.49 | Not significant |

| Harley 2008 | LIFE satisfactionb | 10 | 2.7 | 0.95 | 9 | 3.33 | 1.19 | 1.12 | P < 0.05 |

| Harley 2008 | SOS‐10c | 10 | 35.3 | 13.12 | 9 | 21.56 | 11.09 | 1.18 | P < 0.05 |

N: number

P: P value

SD: standard deviation

aCohen's D > 0.5 is moderate effect and > 0.8 is large effect.

bSAS‐SR and LIFE‐RIFT (SAS work/social recreational, LIFE work/recreation/satisfaction): Lower scores are healthier.

cSchwartz Outcome Scale‐10 (SOS‐10): Higher scores are healthier.

Quality of life

Five trials measured quality of life (Nakagawa 2017; Souza 2016; Town 2017; Wiles 2007; Wiles 2016). However, results for this outcome from the Town 2017 study are not yet available. Wiles 2007 used an unpublished tool to measure quality of life, Town 2017 and Wiles 2016 used the SF‐12 (mental and physical subscales); Souza 2016 used the WHOQOL scale; and Nakagawa 2017 used the SF‐36 scale. Data are reported in Table 5.

3. Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone for quality of life.

| Study ID | Measure | Time point (months) |

N psychotherapy + usual care |

N usual care |

Mean difference | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper |

| Wiles 2007 | Unpublished toola | 4 | 14 | 9 | 1.20 | ‐1.61 | 4.01 |

| Wiles 2016 | SF‐12 mentalb | 6 | 201 | 209 | 6 | 3.5 | 8.2 |

| Wiles 2016 | SF‐12 mentalb | 12 | 194 | 195 | 4.1 | 1.6 | 6.7 |

| Wiles 2016 | SF‐12 mentalb | 46 | 132 | 110 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 6.3 |

| Wiles 2016 | SF‐12 physicalb | 6 | 201 | 209 | −1.7 | −3.4 | 0.02 |

| Wiles 2016 | SF‐12 physicalb | 12 | 194 | 195 | 0.3 | −1.4 | 2 |

| Wiles 2016 | SF‐12 physicalb | 46 | 132 | 110 | 0.9 | ‐2 | 3.7 |

| Souza 2016 | WHOQOL overall QOLc | 6 | 16 | 18 | 0.80 | ‐2.67 | 4.27 |

| Souza 2016 | WHOQOL physicalc | 6 | 16 | 18 | 7.10 | ‐3.04 | 17.24 |

| Souza 2016 | WHOQOL psychologicalc | 6 | 16 | 18 | 3.00 | ‐8.51 | 14.51 |

| Souza 2016 | WHOQOL socialc | 6 | 16 | 18 | 6.50 | ‐6.71 | 19.71 |

| Nakagawa 2017 | SF‐36 mentalb | 6 | 40 | 40 | ‐2.32 | ‐7.25 | 2.6 |

| Nakagawa 2017 | SF‐36 mentalb | 12 | 40 | 40 | ‐1.27 | ‐6.26 | 3.71 |

| Nakagawa 2017 | SF‐36 physicalb | 6 | 40 | 40 | ‐1.17 | ‐6.46 | 3.81 |

| Nakagawa 2017 | SF‐36 physicalb | 12 | 40 | 40 | 0.95 | ‐4.4 | 6.82 |

CI: confidence interval

N: number

aA 6‐item instrument (unpublished) on which one could score between zero and 12: lower scores denote poorer QOL

bSF physical/mental: Higher score denotes better quality of life

cWHOQOL: Higher scores denote higher quality of life.

Economic outcomes

Four studies collected economic data (Nakagawa 2017; Town 2017; Wiles 2007; Wiles 2016); however results from the recent studies are not yet available (Nakagawa 2017; Town 2017). An analysis of cost‐effectiveness was conducted for the large‐scale multi‐centre trial (Wiles 2016), whereas in the pilot study (Wiles 2007), trial authors piloted the method of data collection and reported costs per patient for the entire sample (intervention and control groups combined).

Adverse effects

Two of the included studies reported adverse effect data (Nakagawa 2017; Town 2017). We have presented these in Table 6.

4. Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone for serious adverse events.

| Study ID | Outcome | Measure | Time point, months | N psychotherapy + usual care |

N psychotherapy + usual care with outcome |

% | N usual care | N usual care with outcome | % |

| Nakagawa 2017 | Serious adverse event | Hospitalisation due to depression exacerbation | 12 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 2 | 5 |

| Nakagawa 2017 | Serious adverse event | Suicide | 6 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Town 2017 | Adverse event | Increases in depressive symptoms | 6 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 2 | 6 |

N: number

Follow‐up times reported

Harley 2008 and Wiles 2007 reported all outcome data at four months post randomisation, and Wiles 2016 at six, 12, and (on average) 46 months post randomisation. Souza 2016 reported all outcomes at two, four, five, and six months of follow‐up.

Nakagawa 2017 reported six and 12 months' follow‐up for all outcomes (except economic outcomes), and Town 2017 reported six months' follow‐up for only the main outcomes of depression score and dropout.

Excluded studies

We have listed excluded studies with reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

In total, we excluded 68 full‐text articles referring to 55 studies. Primary reasons for exclusion were as follows: study was not an RCT (n = 8); study did not meet intervention criteria (n = 9); age criteria were not met (n = 5); diagnostic criteria for depression were not met (n = 7); comparison was irrelevant (n = 1); and criteria for TRD were not met (n = 25). Those not meeting TRD criteria included: relapse prevention and/or recurrent depression (n = 13), did not meet criteria for dose and duration of antidepressant treatment (n = 13), other mood or depressive disorders (n = 7), and psychotic disorders (n = 2) (see Characteristics of excluded studies for detail for each study). We excluded some studies (n = 7) for more than one primary reason.

We did not include three large and well‐known trials (STAR*D, REVAMP, and TADS) in this review as they did not meet inclusion criteria.

The STAR*D trial did not apply diagnostic criteria at the stage of randomisation to psychotherapy (Thase, 2007‐ STAR*D). This study also originally included those who could not tolerate antidepressant medication as well as those who had not responded to medication.

For the REVAMP trial (Kocsis, 2009 ‐ REVAMP), not all participants met the DSM diagnosis at the stage of randomisation to the psychotherapy phase.

The TADS study used a definition of TRD that did not fit our review: two failed attempts with treatments ‐ one with an antidepressant medication, and one with either an antidepressant medication or a psychological treatment (McPherson 2003 ‐TADS). No criterion pertained to the dose/duration of treatment in defining a 'failed attempt,' whereas our definition included a minimum of four weeks' treatment at an adequate dose. Further, studies of interventions for those who have not responded to psychological treatments were outside the scope of our review.

Ongoing studies

We will add one ongoing trial to the update of this review (Lynch 2015 ‐ RO‐DBT (REFRAMED).

Studies awaiting classification

Four studies (five references) await assessment and classification as we have found no full texts to date via interlibrary loans or contact with study authors (Checkley, 1999; Moras, 1999; Spooner 1999; Strauss, 2002).

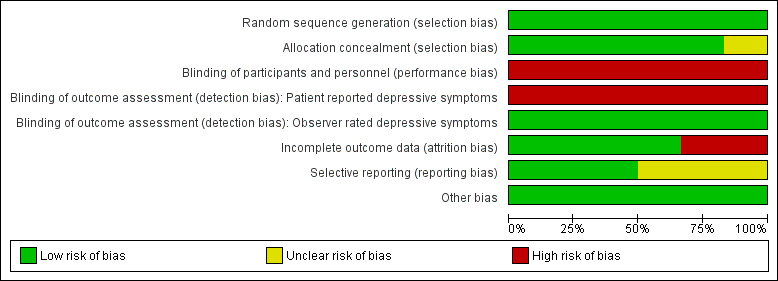

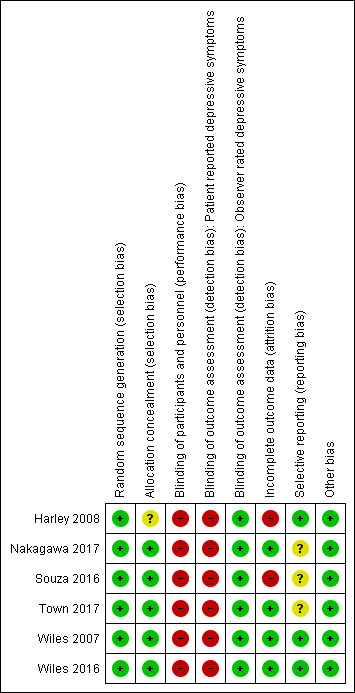

Risk of bias in included studies

We have given full details of the risk of bias for included studies under Characteristics of included studies. We have provided graphical representations of the overall risk of bias in included studies for each risk of bias item in Figure 2, and for each study in Figure 3. Given the small number of studies included, we undertook no formal comparison of reporting bias based on a funnel plot.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

All six studies stated that they were randomised and reported adequate random sequence generation; therefore they were at low risk of bias for this item.

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Five of the six studies were at low risk of bias in this domain (Nakagawa 2017; Souza 2016; Town 2017; Wiles 2007; Wiles 2016), and one was at unclear risk (Harley 2008).

In terms of how allocation was concealed from individual recruiting participants, Harley 2008 did not provide details of the method of allocation concealment used; therefore we marked this one as having unclear risk of bias for this domain. Wiles 2007 and Town 2017 used an individual independent of the recruiting researchers. Wiles 2016 used a telephone randomisation service to conceal allocation from those recruiting participants. Souza 2016 used sequentially numbered brown sealed envelopes containing the randomisation sequence. Nakagawa 2017 used an automated computer system for allocation.

Blinding

For psychological interventions, it is very difficult to blind patients and therapists to the intervention being provided. Participants and personnel providing treatment were not blind to treatment allocation in any of the studies. Therefore for the domain of performance bias, we considered all six studies to be at high risk of bias due to lack of blinding.

For the same reason, all self‐completed BDI outcome assessments were unblinded and at high risk of detection bias. Harley 2008, Nakagawa 2017, and Souza 2016 minimised the likelihood of observer bias by blinding outcome assessors administering the observer‐rated (HAMD) scale. Hence, for the HAMD depression outcome, risk of detection bias was low.

We considered risk of bias due to lack of blinding for the second primary outcome (dropout from the study) as low for all studies, as this is not likely to be affected by observer bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Nakagawa 2017, Wiles 2007, and Wiles 2016 were at low risk of bias in this domain, having conducted their analyses on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis. Nakagawa 2017 and Wiles 2016 analysed outcomes without imputation for missing data first, then evaluated the robustness of their findings (assumed missing at random) by conducting sensitivity analyses imputing missing data. Wiles 2007 used last observation carried forward in the ITT analysis. Souza 2016 indicated that researchers used an ITT approach; however this likely referred to people who received the allocated intervention, as the CONSORT diagram reported including only completers in final analysis and excluding those who did not receive an allocated intervention or were lost to follow‐up. Hence, with 27% dropout, we considered this study to be at high risk for bias for this domain. We also marked Harley 2008 as having high risk of bias due to high dropout without an ITT analysis to account for missing data.

Selective reporting

Three studies were at low risk of bias in this domain, as contact with study authors provided additional or missing information regarding planned and additional analyses (Harley 2008; Wiles 2007; Wiles 2016). Souza 2016 discussed in the study report two new outcomes that were not listed in the protocol. We have not yet received clarification from study authors on this; therefore we have marked risk of bias for this study as unclear. We also considered the two recent studies to be at unclear risk in this domain, as papers (and communication from study authors) stated that remaining outcomes will be reported in future papers (Nakagawa 2017; Town 2017).

Other potential sources of bias

We considered studies at high risk of bias from other sources if we noted any inconsistencies between papers reporting findings that could not be explained by study protocols or study authors in terms of differential attrition, selective follow‐up, or baseline numbers not reported. We observed no such anomalies and therefore considered all six studies to be at low risk of bias from other sources.

Effects of interventions

Comparison 1. Psychotherapy + usual care (including antidepressant medication) versus usual care (including antidepressant medication)

Primary outcomes

1.1 Depressive symptoms

Up to six months (short term)

Self‐reported depressive symptoms

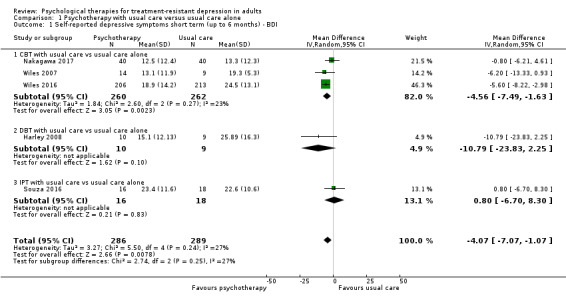

The pooled mean difference on the self‐reported BDI scale (mean difference (MD) ‐4.07, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐7.01 to ‐1.07; five trials, n = 575; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1) favoured the addition of psychotherapy to usual care with antidepressant medication compared with usual care alone. Data show little evidence of heterogeneity (I² = 27%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone, Outcome 1 Self‐reported depressive symptoms short term (up to 6 months) ‐ BDI.

Stratified by therapy type, analyses showed a similar effect for trials focusing on CBT (MD ‐4.56, 95% CI ‐7.49 to ‐1.63; three trials, n = 522; Analysis 1.1). The size of this effect was similar to the overall pooled estimate because a substantial proportion of weight (46.3 %) in the combined analysis came from the Wiles 2016 study included in this group. For group‐based DBT given in addition to usual care compared with usual care (Harley 2008), data show a larger difference in mean BDI score but wide confidence intervals and the null value of zero (MD ‐10.79, 95% CI ‐23.83 to 2.25; one study; n = 19: Analysis 1.1). The addition of Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) (Souza 2016) to usual care showed no difference between addition of IPT to usual care compared with usual care alone (MD 0.80, 95% CI ‐6.70 to 8.30; one trial, n = 34; Analysis 1.1).

Two studies reported results at six months for self‐reported depressive symptoms on the PHQ‐9 scale (Analysis 1.2) (Town 2017; Wiles 2016). This analysis also provided evidence of the benefit of adding psychotherapy to usual care (MD ‐4.66, 95% CI ‐8.72 to ‐0.59; two trials, n = 482; moderate‐quality evidence). However, heterogeneity was substantial (I² = 73%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone, Outcome 2 Self‐reported depressive symptoms short term (up to 6 months) ‐ PHQ‐9.

Combining self‐reported depressive scales across all included studies produced very similar results (SMD ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐0.65 to ‐0.14; six trials, n = 635, moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.3). Heterogeneity was also similar (I² = 37%).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone, Outcome 3 Self‐reported depressive symptoms short term (up to 6 months) ‐ SMD (BDI & PHQ‐9).

Clinician‐rated depressive symptoms

Four studies used an observer‐rated instrument, the HAMD, to measure depressive symptoms (Harley 2008; Nakagawa 2017; Souza 2016; Town 2017). The pooled effect showed a small between‐group difference favouring psychotherapy as an adjunct to usual care (MD ‐3.28, 95% CI ‐5.71 to ‐0.85; four trials, n = 193; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.4). We noted some evidence of heterogeneity (I² = 30%). Stratified by type of therapy, analyses showed that effects were similar for CBT (MD‐3.20, 95% CI ‐5.75 to ‐0.65; one trial; n = 80), ISTDP (MD ‐5.84, 95% CI ‐11.22 to ‐0.46; one trial, n = 60), and DBT (MD ‐5.81, 95% CI ‐11.04 to ‐0.58; one trial, n = 19) in single studies but not for IPT (MD 0.10, 95% CI ‐4.05 to 4.25; one trial, n = 34; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone, Outcome 4 Clinician‐rated depressive symptoms short term (up to 6 months) ‐ HAMD.

7 to 12 months (medium term)

Self‐reported depressive symptoms

Two studies examined outcomes over the medium term (Nakagawa 2017; Wiles 2016). Those who received CBT in addition to usual care, had a BDI‐II score that was lower compared than the score for those who continued with usual care (MD ‐3.40. 95% CI ‐7.21 to 0.40; two trials, n = 475; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.5); however, the effect included the null value of zero. Heterogeneity was moderate (I² = 41%).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone, Outcome 5 Self‐reported depressive symptoms medium term (7 to 12 months) ‐ BDI.

Researchers found beneficial effects of adjunctive therapy in terms of depressive symptoms measured on the PHQ‐9 (Wiles 2016), with a small difference at one year (MD ‐1.90 points, 95% CI ‐3.2 to ‐0.58; one trial, n = 395; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone, Outcome 6 Self‐reported depressive symptoms medium term (7 to 12 months) ‐ PHQ‐9.

Clinician‐rated depressive symptoms

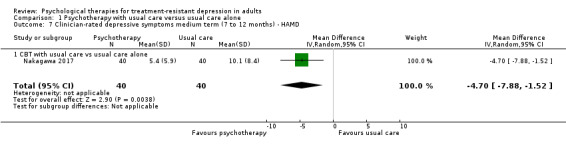

Nakagawa also reported 12‐month results on the HAMD‐GRID scale. These results were similar to those for self‐reported symptoms for this length of follow‐up (MD ‐4.70, 95% CI ‐7.88 to‐1.52; one trial, n = 80; Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone, Outcome 7 Clinician‐rated depressive symptoms medium term (7 to 12 months) ‐ HAMD.

Longer than 12 months (long term)

Self‐reported depressive symptoms

Only one trial reported long‐term outcomes (Wiles 2016). This long‐term follow‐up took place, on average, 46 months after randomisation. At 46 months, those who had received CBT in addition to usual care had fewer symptoms of depression on the BDI scale compared with those given usual care alone (MD ‐4.2, 95% CI ‐7.57 to ‐0.83; one trial, n = 248; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone, Outcome 8 Self‐reported depressive symptoms long term (longer than 12 months) ‐ BDI.

Benefit was also evident in terms of depressive symptoms on PHQ‐9 scores (MD ‐1.6, 95% CI ‐3.26 to ‐0.06; one study, n = 252; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone, Outcome 9 Self‐reported depressive symptoms long term (longer than 12 months) ‐ PHQ‐9.

Clinician‐rated depressive symptoms

No study reported this outcome over the long term.

1.2 Dropout

Up to six months (short term)

Random‐effects meta analysis combining all six studies showed that dropout did not differ between adjunct psychotherapy and usual care groups (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.24; six trials, n = 698; high‐quality evidence) (Harley 2008; Nakagawa 2017; Souza 2016; ; Town 2017; Wiles 2007; Wiles 2016). Data show no evidence of heterogeneity (I² = 0%; Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy with usual care versus usual care alone, Outcome 10 Dropout short term (up to 6 months).