Abstract

Background:

High pre-pregnancy body mass index (ppBMI) has been linked to neurodevelopmental impairments in childhood. However, very few studies have investigated mechanisms in human cohorts.

Methods:

Among 1361 mother-child pairs in Project Viva, we examined associations of ppBMI categories with the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test III [PPVT] and Wide Range Assessment of Visual Motor Abilities [WRAVMA] in early childhood (median 3.2y); and with the Kaufman Brief Intelligence test (KBIT) and WRAVMA in mid-childhood (7.7y). We further examined the role of maternal inflammation in these associations using the following measures from the 2nd trimester of pregnancy: plasma C-reactive protein (CRP), dietary inflammatory index (DII), and plasma omega-6 (n-6): n-3 fatty acid ratio.

Results:

Children of mothers with prenatal obesity (ppBMI ≥30kg/m2) had WRAVMA scores that were 2.1 points lower (95% CI −3.9, −0.2) in early childhood than children of normal weight mothers (ppBMI 18.5-<25 kg/m2), in a covariate adjusted model. This association was attenuated when we additionally adjusted for maternal CRP (β −1.8 points; 95% CI −3.8, 0.2) but not for other inflammatory markers. PpBMI was not associated with other cognitive outcomes.

Conclusion:

Maternal inflammation may modestly mediate the association between maternal obesity and offspring visual motor abilities.

INTRODUCTION

Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity, which affects one in three women of childbearing age (1, 2), has been associated with adverse offspring health and developmental outcomes. Recent studies have reported that higher maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (ppBMI) was associated with offspring developmental delay, anxiety behaviors, autism-spectrum disorders (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and cognitive deficits (3, 4). However, the underlying mechanisms for these associations are still not well understood.

The perinatal environment plays a critical role in fetal developmental programming, and perturbations to this environment during critical periods of development can have life-long impact on many body systems, including processes that modulate fetal brain development. In rodent and human studies, obesity during pregnancy has been associated with higher systemic and placental inflammation, dysregulated metabolic and neuro-endocrine signaling, and increased oxidative stress and antioxidant micronutrient deficiencies, which may further accentuate the obesogenic inflammatory milieu (5-8). Placental inflammation, in turn, has been causally linked to fetal neuronal inflammation in obese rodent dams, which has been shown to be associated with altered fetal neurogenesis, myelination, and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus and hypothalamus (9-12). Animal models have also suggested a causal link between maternal obesity and impairment in specific domains of cognitive function. Memory, learning and visual-motor functions all play key roles in cognitive functioning (13). In rodent studies, offspring of obese dams have impaired performances in the Morris Water Maze, the Barnes Maze, as well as in novel object recognition, which are tests that assess visual-spatial orientation, memory and learning (10, 11, 14). However, there is limited longitudinal evidence in humans on the mechanisms linking maternal obesity to later deficits in specific cognitive domains in childhood.

Here, we examined associations of maternal obesity with specific early and mid-childhood cognitive domains. We additionally explored the role of maternal-obesity related inflammation in these associations, with markers of systemic inflammation (C-reactive protein, CRP) as well as of dietary inflammation (plasma omega-6 (n-6): omega-3 (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) ratio and the dietary inflammatory index (DII)). Based on available evidence from animal models, we hypothesized that higher maternal ppBMI would be associated with lower offspring scores in memory, learning, fine-motor and visual-spatial tests and that maternal and dietary inflammatory markers would play a mediating role in these associations.

METHODS

Study design and participants

We analyzed data from participants in Project Viva, a prospective longitudinal pre-birth cohort study. From April 1999 to July 2002, Project Viva enrolled pregnant women at their initial prenatal visits (median 9.9 weeks of gestation) at 8 obstetrical offices of Atrius Health, a multispecialty group practice in eastern Massachusetts. Exclusion criteria included multiple gestation, inability to answer questions in English, gestational age of at least 22 weeks at the initial prenatal care appointment, and plans to move away from the area before delivery. Study procedures for this cohort have been described previously (15). For this analysis, we included women with a ppBMI ≥18.5 kg/m2 without preexisting type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus, who completed early or mid-childhood in-person visits with their child. Of 2,128 live births, our sample comprised 1,361 Project Viva mothers and children (1,246 at median age 3.2 years and 1,070 at median age 7.7 years). The Institutional Review Boards of the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital approved the study. All mothers provided written informed consent.

Exposure

Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI (ppBMI).

Research participants reported their height and pre-pregnant weight at recruitment visits. We calculated ppBMI in kg/m2 and categorized it per WHO guidelines as follows: normal (BMI 18.5 to <25kg/m2), overweight (25 to <30 kg/m2) and obese (≥30 kg/m2).

Markers of systemic and dietary inflammation

We examined three markers of inflammation: 1) Plasma CRP; 2) Plasma n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio; and 3) DII. Research assistants collected blood samples during the routine mid-pregnancy clinical blood draw between 22 and 31 weeks of gestation. Samples were processed within 24hr and stored at −80°C until analyses. We measured plasma CRP, a non-specific marker of chronic systemic inflammation, using ELISA. We assayed plasma fatty acids using gas-liquid chromatography (16) and calculated total n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio. Eicosanoid products derived from n-6 PUFA are potent modulators of inflammation and lead to increased production of IL-1, NFKB, and TNF, while those derived from n-3 PUFA are anti-inflammatory (17). Higher ratios have been associated with various inflammatory markers and have been implicated in cardiovascular and metabolic disorders (18).

Mothers completed self-administered semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) at the first (median 9.9 weeks of gestation) and second (median 27.9 weeks of gestation) in-person study visits. The first FFQ assessed diet intake since the last menstrual period and the second FFQ during the previous 3 months. The FFQ has been validated in pregnancy (19). We used the Harvard nutrient composition database, which is based primarily on USDA publications, to obtain estimates of nutrients (20). We used these dietary data to calculate DII scores for each mother. The DII is a literature-based and population-adjusted measure which was developed to provide an aggregate assessment of dietary inflammation in adults, and has been validated with various inflammatory markers, including CRP, TNF-a, and IL-6 in non-pregnant and pregnant adults including in this cohort (21, 22). Detailed procedure for DII estimations in this cohort have been described previously (21). A higher (i.e., more positive) DII score indicates a more proinflammatory diet, whereas a more negative score represents a more anti-inflammatory diet. We used the mean of first- and second-trimester DII for this analysis because DII at these time points were closely correlated (r=0.61, p<0.0001) (21).

Child cognitive outcomes

Intelligence measures.

In early childhood (median 3.2 years), trained research staff administered the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-3rd edition (PPVT-III), a test of receptive language. In mid-childhood (median 7.7 years), we administered the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test-2nd edition (KBIT-II) which measures verbal and non-verbal intelligence. Both the PPVT-III and the KBIT-II correlate strongly (Pearson r=0.90 and 0.89, respectively) with the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (23) and are scaled to a mean (SD) of 100 (15).

Visual-motor measures.

In early childhood, we administered the Wide Range Assessment of Visual Motor Abilities (WRAVMA) which includes the fine motor (pegboard), visual spatial (matching), and visual motor (drawing) subtests. Subtest scores were combined to yield a visual motor composite score, the total WRAVMA score. In mid-childhood, we administered the WRAVMA visual motor (drawing) subtest only. All WRAVMA tests are scaled to a mean (SD) of 100 (15).

Memory and learning measures:

In mid childhood, we assessed memory and learning with the design memory and picture memory subsets of Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning (WRAML); these two subset scores were combined to yield a Visual Memory Index composite score. The WRAML-Visual Memory Index is scaled to a mean (SD) of 10 (3).

Covariates

Mothers reported information about their age, education, household income, race/ethnicity, parity, smoking status before learning of pregnancy, and partner’s education via questionnaires and interviews. We obtained information on child sex and date of delivery from hospital medical records. To measure maternal intelligence, we administered the PPVT-III at the early childhood visit and the KBIT-II at the mid-childhood visit, to the mother.

Data analysis

We analyzed maternal ppBMI, our main exposure, as a categorical variable, and cognitive outcomes as continuous variables. We used multiple imputation for missing data. We imputed 50 values for each missing observation to create 50 “completed” datasets including all 2,128 mother-child pairs. Following imputation, we combined the multivariable modeling estimates using PROC MI ANALYZE. In adherence with Project Viva protocols, we set our analytic sample sizes based on those who were eligible to have exposures and outcomes. Characteristics were similar in the un-imputed and imputed datasets (data not shown).

We investigated the associations of maternal ppBMI with childhood cognitive outcomes using multivariable linear regression. . We also included maternal and family covariates as potential confounders. We constructed regression models adjusting for the following potential confounders: maternal age at enrollment, race/ethnicity, education, pre-pregnancy smoking status, parity and cognitive test score; household income and partner’s education. To optimize sample sizes, we adjusted for maternal PPVT in models predicting early childhood cognitive outcomes, and for maternal KBIT in models predicting mid-childhood outcomes. We also included child sex and age as covariates in our multivariable models to increase precision and decrease variability in our cognitive outcomes.

We also explored the role of maternal obesity-related inflammation in offspring cognition to investigate potential mechanistic pathways. We adjusted the associations of ppBMI with offspring cognitive outcomes (primary association) for the three inflammatory markers (CRP, n6:n3 PUFA and DII), individually and jointly, to determine the extent to which this adjustment attenuated the associations of ppBMI with cognitive outcomes. We also conducted mediation analysis using the mediation macro developed by VanderWeele (24) to examine the extent to which the exposure – outcome associations were mediated through CRP, n-6:n-3 PUFA and DII. We further examined the association of ppBMI with inflammatory markers and of inflammatory markers with cognitive outcomes.

We conducted all analyses with the use of SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Mean (SD) maternal ppBMI was 25.0 (5.2) kg/m2 and age was 32.2 (5.2) years (Table 1); 70% of mothers were white, 61% had a household income >$70,000/year, 69% had at least a college education, and 63% had partners with at least a college education. Mothers with obesity were more likely to have a lower socioeconomic status (i.e. less educated, lower annual income, have a partner without college degree) and have lower PPVT and KBIT scores (Table 1). Compared with the 767 women excluded from the analysis, the 1,361 included women were slightly older (mean age at enrollment 32.2 vs. 31.2 years) and were more likely to report white race/ethnicity (70% vs. 61%), be college graduates (69% vs. 57%) and have a household income greater than $70,000/year (61% vs. 52%). However, ppBMI (mean 25.0 vs. 24.8 kg/m2) and child sex (48% vs. 49% female) were similar in both groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1,361 mothers and children in the Project Viva cohort, overall and according to maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category

| Characteristics by maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall N=1361 |

18.5 to <25.0 kg/m2 851 (62.6%) |

25.0 to <30.0 kg/m2 306 (22.5%) |

≥30.0 kg/m2 203 (14.9%) |

|

| N (%) or mean (SD) | ||||

| Maternal characteristics | ||||

| Age at enrollment, years | 32.2 (5.2) | 32.3 (5.1) | 32.1 (5.4) | 31.6 (5.3) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 25.0 (5.2) | 21.9 (1.8) | 27.0 (1.4) | 34.8 (4.3) |

| Maternal education, % | ||||

| . Not a college graduate | 426 (31) | 216 (25) | 100 (33) | 110 (54) |

| . College graduate | 935 (69) | 636 (75) | 207 (67) | 93 (46) |

| Mother's PPVT score (3y visit), points | 105.5 (14.7) | 106.7 (14.3) | 104.2 (14.3) | 102.4 (16.3) |

| Mother's KBIT score (7y visit), points | 106.4 (15.5) | 108.3 (14.8) | 104.9 (15.8) | 100.4 (16.0) |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||

| . White | 946 (70) | 636 (75) | 197 (64) | 112 (55) |

| . Black | 201 (14) | 89 (10) | 51 (17) | 61 (30) |

| . Hispanic | 95 (7) | 49 (6) | 28 (9) | 17 (8) |

| . Asian | 62 (5) | 47 (6) | 11 (4) | 4 (2) |

| . Other | 57 (4) | 29 (3) | 19 (6) | 9 (4) |

| Pre-pregnancy smoking status, % | ||||

| . Never | 945 (69) | 604 (71) | 203 (67) | 137 (67) |

| . Smoked, quit >3 months prior to pregnancy test | 273 (20) | 169 (20) | 69 (22) | 35 (18) |

| . Smoked in the 3 months prior to pregnancy test | 143 (11) | 78 (9) | 34 (11) | 31 (15) |

| Nulliparous, % | ||||

| . No | 718 (53) | 412 (48) | 180 (59) | 126 (62) |

| . Yes | 643 (47) | 439 (52) | 126 (41) | 78 (38) |

| Household income >$70,000/year, % | ||||

| . No | 530 (39) | 290 (34) | 117 (38) | 124 (61) |

| . Yes | 831 (61) | 562 (66) | 189 (62) | 79 (39) |

| Partner's education, % | ||||

| . Not a college graduate | 497 (37) | 256 (30) | 116 (38) | 126 (62) |

| . College graduate | 864 (63) | 596 (70) | 191 (62) | 77 (38) |

| Average 1st-2nd trim DII, units | −2.6 (1.4) | −2.7 (1.3) | −2.4 (1.4) | −2.2 (1.4) |

| 2nd trim CRP, mg/L | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.3 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.4) |

| 2nd trim plasma n3 (%molar) | 136.7 (57.7) | 140.4 (57.7) | 134.7 (60.9) | 124.3 (50.6) |

| 2nd trim plasma n6 (%molar) | 1441 (528) | 1437 (522) | 1443 (553) | 1456 (515) |

| 2nd trim plasma n6:n3 | 11.2 (3.8) | 10.8 (3.6) | 11.4 (3.8) | 12.5 (4.2) |

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Female, % | ||||

| . No | 705 (51.8) | 432 (50.8) | 170 (55.4) | 103 (50.7) |

| . Yes | 656 (48.2) | 419 (49.2) | 136 (44.6) | 100 (49.3) |

| Age at early childhood visit, years, median (IQR) | 3.2 (3.1-3.3) | 3.2 (3.1-3.3) | 3.2 (3.1-3.3) | 3.2 (3.1-3.3) |

| Age at mid-childhood visit, years, median (IQR) | 7.7 (7.3-8.4) | 7.7 (7.3-8.3) | 7.7 (7.4-8.5) | 7.8 (7.3-8.6) |

| Early childhood cognitive outcomes | ||||

| PPVT-III | 103 (15) | 104 (14) | 102 (15) | 102 (15) |

| Total WRAVMA | 102 (11) | 103 (11) | 101 (11) | 98 (11) |

| WRAVMA pegboard | 98 (11) | 99 (11) | 98 (11) | 96 (10) |

| WRAVMA matching | 108 (14) | 109 (14) | 107 (13) | 104 (13) |

| WRAVMA drawing | 99 (11) | 100 (11) | 98 (11) | 98 (11) |

| Mid-childhood cognitive outcomes | ||||

| KBIT-II verbal | 112 (15) | 114 (14) | 110 (15) | 106 (18) |

| KBIT-II non-verbal | 106 (17) | 107 (17) | 106 (17) | 103 (17) |

| WRAVMA drawing | 92 (17) | 93 (17) | 91 (16) | 90 (16) |

| WRAML visual memory | 17 (4) | 17 (4) | 17 (4) | 17 (5) |

BMI: Body Mass Index. PPVT: Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-3rd edition. KBIT: Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test-2nd edition. DII: Dietary Inflammatory Index. CRP: C-reactive protein. n-6:n-3: omega-6: omega-3 ratio. IQR: Inter Quartile Range. WRAVMA: Wide Range Assessment of Visual Motor Abilities. WRAVML: Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning.

Maternal ppBMI and childhood cognition

Intelligence measures:

The mean (SD) PPVT-III score in early childhood was 103 (15) points. The mean (SD) KBIT-II verbal and non-verbal scores in mid-childhood were 112 (15) points and 106 (17) points, respectively. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity was associated with these early and mid-childhood intelligence measures in unadjusted models, but after adjustment for socio-demographic factors, associations were substantially attenuated and confidence intervals no longer excluded the null. For example, compared with normal ppBMI category, maternal pre-pregnancy obesity was associated with KBIT-II verbal scores that were 7.2 points lower (95% CI: −9.8, −4.6) in unadjusted analysis, but these associations were substantially weaker after adjustment for socio-demographic factors (−1.5 points, 95% CI: −3.9, 0.8). The pattern of associations with other measures of global intelligence was similar (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category with early and mid-childhood cognitive outcomes

| Outcome | BMI Category (kg/m2) |

Model 0a | Model 1b β (95% CI) |

Model 2c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intelligence measures | ||||

| Early Childhood | ||||

| PPVT-III | 18.5-<25.0 | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) |

| 25.0-<30.0 | −2.5 (−4.5, −0.5) | −0.4 (−2.2, 1.4) | −0.2 (−2.0, 1.6) | |

| ≥30.0 | −2.8 (−5.3, −0.3) | 1.9 (−0.4, 4.1) | 1.5 (−0.7, 3.8) | |

| Mid-Childhood | ||||

| KBIT-II verbal | 18.5-<25.0 | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) |

| 25.0-<30.0 | −3.3 (−5.6, −1.1) | −0.6 (−2.6, 1.3) | −0.4 (−2.3, 1.5) | |

| ≥30.0 | −7.2 (−9.8, −4.6) | −1.5 (−3.9, 0.8) | −1.4 (−3.7, 0.9) | |

| KBIT-II non-verbal | 18.5-<25.0 | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) |

| 25.0-<30.0 | −1.5 (−4.0, 1.1) | 0.3 (−2.2, 2.8) | 0.5 (−2.0, 2.9) | |

| ≥30.0 | −4.1 (−7.1, −1.2) | −0.3 (−3.3, 2.7) | −0.2 (−3.2, 2.7) | |

| Visual-motor measures | ||||

| Early Childhood | ||||

| Total WRAVMA | 18.5-<25.0 | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) |

| 25.0-<30.0 | −1.4 (−3.0, 0.2) | −0.5 (−1.9, 1.0) | −0.4 (−1.9, 1.1) | |

| ≥30.0 | −4.2 (−6.1, −2.3) | −2.0 (−3.9, −0.1) | −2.1 (−3.9, −0.2) | |

| WRAVMA-Fine motor subset (pegboard) |

18.5-<25.0 | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) |

| 25.0-<30.0 | 0.0 (−1.5, 1.4) | 0.4 (−1.1, 1.9) | 0.4 (−1.1, 1.9) | |

| ≥30.0 | −2.8 (−4.6, −1.0) | −1.8 (−3.7, 0.0) | −1.8 (−3.7, 0.0) | |

| WRAVMA-Visual spatial subset (matching) |

18.5-<25.0 | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) |

| 25.0-<30.0 | −1.7 (−3.5, 0.2) | −0.6 (−2.4, 1.3) | −0.5 (−2.3, 1.3) | |

| ≥30.0 | −4.5 (−6.8, −2.2) | −1.8 (−4.1, 0.5) | −1.9 (−4.3, 0.4) | |

| WRAVMA-Visual motor subset (drawing) |

18.5-<25.0 | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) |

| 25.0-<30.0 | −1.4 (−2.9, 0.2) | −0.7 (−2.3, 0.8) | −0.7 (−2.2, 0.8) | |

| ≥30.0 | −2.1 (−4.0, −0.2) | −0.8 (−2.7, 1.2) | −0.8 (−2.7, 1.1) | |

| Mid-Childhood | ||||

| WRAVMA- Visual motor subset (drawing) |

18.5-<25.0 | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) |

| 25.0-<30.0 | −1.8 (−4.3, 0.8) | −0.9 (−3.4, 1.6) | −0.8 (−3.4, 1.7) | |

| ≥30.0 | −3.1 (−6.0, −0.2) | −1.7 (−4.7, 1.3) | −1.7 (−4.7, 1.3) | |

| Memory and Learning measures | ||||

| WRAML-visual memory | 18.5-<25.0 | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) |

| 25.0-<30.0 | 0.0 (−0.7, 0.6) | 0.2 (−0.5, 0.8) | 0.2 (−0.5, 0.9) | |

| ≥30.0 | −0.4 (−1.1, 0.4) | 0.2 (−0.6, 1.0) | 0.2 (−0.6, 1.0) |

PPVT-III: Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-3rd edition. KBIT-II: Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test-2nd edition. WRAVMA: Wide Range Assessment of Visual Motor Abilities. WRAVML: Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning.

Model 0. Unadjusted.

Model 1. Adjusted for maternal age at enrollment, race/ethnicity, education, pre-pregnancy smoking status, and parity; household income and partner education; and child sex and age at outcome.

Model 2. Model 1 + maternal IQ.

Visual-motor measures:

The mean (SD) total WRAVMA score in early childhood was 102 (11) points; the mean (SD) subscores for fine motor (pegboard), visual motor (drawing), and visual spatial (matching) domains were 98 (11), 99 (11) and 108 (14), respectively. The mean (SD) WRAVMA-drawing (visual motor) subset score in mid-childhood was 92 (17) points. Children of mothers with obesity had total WRAVMA scores that were lower compared to children of normal weight mothers in unadjusted models (β −4.2 points; 95% CI −6.1, −2.3) (Table 2). This association was attenuated after adjustment for socio-demographic factors and maternal KBIT score in the fully adjusted model, but continued to be significant (β −2.1 points; 95% CI −3.9, −0.2) (Table 2). Further analysis of the WRAVMA subscales in early childhood revealed that, when compared to normal maternal ppBMI category, maternal pre-pregnancy obesity was associated with lower fine motor (β −2.8 points; 95% CI −4.6, −1.0), visual motor (β −2.1 points; 95% CI −4.0, −0.2), and visual spatial (β −4.5 points; 95% CI −6.8, −2.2) scores in unadjusted analysis (Table 2). These associations were considerably attenuated after adjustment for socio-demographic factors and confidence intervals no longer excluded the null (Table 2). In adjusted analysis, however, maternal pre-pregnancy obesity remained weakly associated with the fine motor subset scores (β −1.8 points; 95% CI −3.7, 0.0). In mid-childhood, similarly to early childhood, maternal pre-pregnancy obesity was not associated with visual motor (drawing) subset scores in adjusted analysis (β −1.7 points; 95% CI −4.7, 1.3) (Table 2).

Memory and learning measures:

In mid-childhood, the mean (SD) WRAML-Visual Memory Index score was 17 (4) points. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity was not associated with WRAML-Visual Memory Index score (β −0.4 points; 95% CI −1.1, 0.4) in unadjusted analysis (Table 2).

Maternal ppBMI and markers of inflammation

After adjustment for maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, smoking, parity and household income, mothers with obesity had higher CRP (β 0.9 mg/L; 95% CI 0.6, 1.2), plasma n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio (β 1.4; 95% CI 0.5, 2.4) and DII (β 0.2 units; 95% CI 0.0, 0.4), compared to mothers with normal weight (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category with markers of inflammation during pregnancy

| Outcome | BMI category (kg/m2) |

Unadjusted β (95% CI) |

Adjusteda β (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd trimester CRP, mg/L | 18.5-<25.0 | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) |

| 25.0-<30.0 | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | |

| ≥30.0 | 1.0 (0.7, 1.3) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | |

| 2nd trimester plasma n6:n3 | 18.5-<25.0 | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) |

| 25.0-<30.0 | 0.6 (0.0, 1.2) | 0.5 (−0.1, 1.1) | |

| ≥30.0 | 1.7 (0.7, 2.6) | 1.4 (0.5, 2.4) | |

| Mean 1st+2nd trimester DII, units | 18.5-<25.0 | 0.0 (ref) | 0.0 (ref) |

| 25.0-<30.0 | 0.3 (0.1, 0.4) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.3) | |

| ≥30.0 | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) | 0.2 (0.0, 0.4) |

CRP: C-reactive protein. n-6:n-3: omega-6: omega-3. DII: Dietary Inflammatory Index.

Adjusted for maternal age at enrollment, race/ethnicity, education, pre-pregnancy smoking status, parity, and household income.

Mediation of associations between maternal ppBMI and childhood cognition by inflammation

When maternal CRP was additionally included as a covariate in the multivariable linear regression analysis, the magnitude of the association of maternal obesity with early childhood total WRAVMA score was reduced by approximately 15% (β −2.1 points; 95% CI −3.9, −0.2, before vs. β −1.8 points; 95% CI −3.8, 0.2, after adjustment). This association was partially mediated through maternal CRP; the estimate for the indirect effect was −0.3 points (95% CI −0.7, 0.1). Similarly, after adjustment for maternal CRP, the magnitude of the association of maternal obesity with scores on the fine motor subset of the WRAVMA was reduced by approximately 28% (β −1.8 points; 95% CI −3.7, 0.0, before vs. β −1.3 points; 95% CI −3.2, 0.7, after adjustment). This association was mediated in part through maternal CRP; the estimate for the indirect effect was −0.6 points (95% CI −1.0, −0.1). Inclusion of n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio or DII did not attenuate the associations of maternal ppBMI category with WRAVMA scores. Results were similar to the mediation analysis of CRP alone when all three inflammatory markers were jointly included in the regression model for the total WRAVMA score (β −1.7 points; 95% CI −3.7, 0.3, after adjustment) and the fine motor subset of the WRAVMA (β −1.2 points; 95% CI −3.1 0.8, after adjustment).

Association of obesity-related maternal inflammation with cognitive outcomes

Maternal plasma CRP and n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio were not associated with early childhood PPVT-III scores in adjusted analysis. However, maternal DII was associated with lower early childhood PPVT-III scores (β −2.4 points for every unit increase in DII; 95% CI −3.0, −1.7) in unadjusted analysis and remained weakly associated (β −0.6 points for every unit increase in DII; 95% CI −1.2, 0.0) in fully adjusted models (Table 4). Maternal CRP, n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio and DII were not associated with mid-childhood KBIT non-verbal scores in fully adjusted models. However, n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio (β −0.3 points for every unit increase in n-6:n-3 ratio; 95% CI −0.6, 0.0) and DII (β −0.6 points for every unit increase in DII; 95% CI −1.3, 0.0) both had weak associations with KBIT verbal scores in fully adjusted models. With regards to visual motor outcomes, maternal CRP remained weakly associated with the fine motor subset scores of the WRAVMA in early childhood (β −0.6 points for every 1 mg/L increase in CRP; 95% CI −1.3, 0.0) in fully adjusted models (Table 4). Associations of n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio and DII with WRAVMA or WRAML-Visual Memory scores were null in fully adjusted models.

Table 4.

Associations of inflammatory markers with early (n=1246) and mid-childhood (n=1070) cognitive outcomes

| Exposures | CRP β (95% CI) | n-6:n-3 β (95% CI) | DII β (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda |

| Intelligence measures | ||||||

| Early Childhood | ||||||

| PPVT-III | −0.8 (−1.6, 0.0) | −0.1 (−0.9, 0.6) | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.1) | 0.1 (−0.2, 0.3) | −2.4 (−3.0, −1.7) | −0.6 (−1.2, 0.1) |

| Mid-Childhood | ||||||

| KBIT-II verbal | −1.3 (−2.3, −0.3) | −0.1 (−1.0, 0.8) | −0.6 (−1.0, −0.3) | −0.3 (−0.6, 0.0) | −3.1 (−3.8, −2.4) | −0.6 (−1.3, 0.0) |

| KBIT-II nonverbal | −0.5 (−1.5, 0.6) | 0.3 (−0.7, 1.3) | 0.1 (−0.3, 0.4) | 0.2 (−0.2, 0.6) | −1.4 (−2.2, −0.7) | 0.0 (−0.9, 0.8) |

| Visual-motor measures | ||||||

| Early Childhood | ||||||

| Total WRAVMA | −0.8 (−1.4, −0.1) | −0.3 (−1.0, 0.3) | −0.2 (−0.4, 0.0) | −0.1 (−0.4, 0.1) | −0.8 (−1.3, −0.3) | 0.1 (−0.5, 0.6) |

| WRAVMA-Fine motor (pegboard) | −0.8 (−1.4, −0.2) | −0.6 (−1.3, 0.0) | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.1) | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.1) | −0.2 (−0.7, 0.3) | 0.2 (−0.3, 0.7) |

| WRAVMA-Visual spatial (matching) | −0.5 (−1.3, 0.3) | 0.0 (−0.9, 0.8) | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.2) | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.3) | −1.2 (−1.8, −0.6) | −0.1 (−0.7, 0.6) |

| WRAVMA-Visual motor (drawing) | −0.3 (−1.0, 0.3) | −0.1 (−0.7, 0.6) | −0.2 (−0.5, 0.0) | −0.2 (−0.5, 0.0) | −0.4 (−0.9, 0.1) | 0.1 (−0.5, 0.6) |

| Mid-Childhood | ||||||

| WRAVMA (drawing) | −0.2 (−1.3, 0.8) | 0.1 (−1.0, 1.2) | −0.2 (−0.5, 0.2) | −0.1 (−0.5, 0.3) | −0.5 (−1.2, 0.3) | 0.2 (−0.7, 1.1) |

| Memory and Learning measures | ||||||

| WRAML visual memory | 0.0 (−0.3, 0.3) | 0.1 (−0.2, 0.4) | 0.0 (−0.1, 0.1) | 0.0 (−0.1, 0.1) | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.1) | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.3) |

PPVT-III: Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-3rd edition. KBIT-II: Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test-2nd edition. WRAVMA: Wide Range Assessment of Visual Motor Abilities. WRAVML: Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning. CRP: C-reactive protein. n-6:n-3: omega-6: omega-3. DII: Dietary Inflammatory Index.

Adjusted for maternal age at enrollment, race/ethnicity, education, IQ, pre-pregnancy smoking status, parity, household income and partner education, child sex and age at outcome

DISCUSSION

Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity has been associated with adverse cognitive outcomes in several epidemiological studies but the specific cognitive domains affected and the mechanisms underlying these associations remain unclear. Here, we show that children of mothers with obesity may have perturbations in global visual motor abilities in early childhood, particularly in the fine motor domain, compared to children of normal weight mothers, and that this association may be partially mediated by maternal obesity-related inflammation.

Global cognitive tests routinely used in epidemiological studies (such as intelligence scales) may have important limitations. The same overall intelligence quotient score between individuals may reflect different patterns of performance in different domains, and thus may mask different patterns of ability, sometimes quite substantial (13). Therefore, it may be important to evaluate specific domains of cognition such as memory, learning, or visual-motor abilities, which this study assessed. Our results suggest that a specific cognitive domain (visual-motor abilities) that is affected in animal models of maternal obesity may also be affected in children of mothers with obesity. Two prior human cohort studies have investigated the effect of ppBMI on fine motor skills only, with similar findings (25, 26). Casas et al (26) reported that higher maternal BMI was associated with lower fine motor scores on the Bayley-III (−0.28 points; 95% CI: −0.60, 0.03) in a Greek mother-child longitudinal cohort. However, the Bayley-III poorly integrates measures of visual-perception and motor skills, in contrast to the WRAVMA test.

Our findings also highlight the critical importance of the postnatal environment in the development of children’s cognitive skills. Maternal obesity in this cohort was associated with most offspring cognitive measures in unadjusted models but there was significant attenuation after adjustment for markers of socioeconomic status. This finding suggests that analyses of the possible causal contribution of maternal obesity to childhood outcomes must consider the broader psychosocial context in which obesity is embedded. One of the strengths of this study was that we obtained and adjusted for robust measures of these socioeconomic confounders. Other studies have had similar findings, with attenuation of some the associations of maternal ppBMI with offspring outcomes after adjustment for confounders (25, 27, 28). For example, Yeung et al (25) found that in unadjusted analyses of the Upstate KIDS cohort, maternal obesity was associated with higher odds of failing most domains on the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ); but only the fine motor domain remained significant after adjustment for covariates, results that are similar to our study. Studies that have found stronger associations of maternal ppBMI with childhood cognition did so only with more extreme levels of obesity(classes II and III) (29, 30).

Another strength of this study is that we investigated inflammation, one of the potential biological mechanism linking maternal obesity and long-term cognitive outcomes. In this cohort, we showed that ppBMI was associated with systemic inflammation, and that this inflammation in turn was associated with lower scores on the fine motor subscale of the WRAVMA. The magnitude of the association of maternal ppBMI category with scores on the fine motor subset of the early childhood WRAVMA was reduced by almost one third after adjusting for maternal CRP, suggesting a partial mediation by maternal inflammation. The impact of the maternal inflammatory state on offspring neurodevelopment has been extensively described in preterm infants particularly in relation to intrauterine infections and sepsis (31). Obesity is a systemic inflammatory condition with chronic activation of the innate immune system. Similar to prior published studies, we found that maternal ppBMI was associated with higher CRP (8, 32). Our mediation results are consistent with findings from rodent studies in which maternal obesity-related inflammation has been linked to impaired offspring visual motor abilities (11, 33). While maternal CRP has been a useful marker in other studies examining the role of maternal inflammation in fetal and childhood outcomes (34), and thus may be a good inflammatory biomarker to study in this association, other biomarkers such as TNF-alpha and IL-6 may be more specific biomarkers of inflammation, as they are directly produced by adipocytes, placental macrophages and brain microglia, and have been shown to be associated with increased anxiety and decreased cognition in human and rodent studies (12, 35).

Additionally, we showed that DII and n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio, although associated with ppBMI, were not physiological mediators like CRP, in that they did not attenuate associations of ppBMI with offspring visual motor outcomes. Furthermore, results of the joint inflammation mediation analysis were similar compared to the mediation analysis with CRP alone. This finding suggests that systemic inflammation might play a more substantial mechanistic role, compared to dietary inflammation, in the association of maternal obesity with WRAVMA in early childhood. It may also suggest that systemic inflammation might be the common biologic pathway via which dietary inflammation and other sources of intrinsic inflammation converge to impact visual motor outcomes. Finally, the fact that DII and plasma n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio were associated with only global intelligence measures (and not visual motor measures) suggest that they may play an independent but synergic role in the pathogenesis of offspring neurodevelopmental impairment. Similarly, in the EDEN Cohort, Bernard et al (36) found negative associations of maternal dietary n-6:n-3 PUFA ratios with ASQ scores in early childhood, but not with fine motor abilities. In fact, dietary inflammation and metabolic inflammation (as measured by CRP or other adipokines, such as TNF-alpha, secreted by adipocytes) may alter specific domains of cognition, each via unique mechanisms. These results could lay the groundwork for larger investigations to explore the role of fatty acid balance and dietary inflammation in obese pregnant women on specific domains of offspring neurodevelopment.

Overall, we show a modest mediation effect by CRP in the association of maternal obesity with offspring cognition. Inflammation may be only one mechanism potentially involved in the association of maternal obesity with offspring cognition. Other mechanisms may include insulin and leptin resistance (37), alteration of BDNF-mediated synaptic plasticity (10), inadequate antioxidant micronutrient status (oxidative stress has been associated with impaired fetal neurogenesis in animal models, 9), epigenetic influences (3, 4) and differences in breastmilk composition (38). These distinct mechanistic pathways, along with inflammation, could synergically act to alter offspring brain development pre- and postnatally.

Limitations of our study are that 1) the Project Viva cohort is characterized by generally higher socioeconomic status, lower rates of obesity, and higher intelligence scores compared to the average US population, limiting generalizability to other cohorts. 2) We may have been underpowered in our study to detect an association between ppBMI and offspring intelligence measures. Previously published studies that have found significant associations have had cohort size ranging from ~5,000 to ~30,000 mother-infant dyads (26-29). 3) We observed only a modest association of maternal ppBMI with offspring cognitive outcomes, so we were limited in our ability to assess mediating inflammatory influences on these associations. 4) We were missing data on some variables, and therefore used imputed data for our analysis. However, characteristics were similar in the un-imputed and imputed datasets (data not shown). 5) Another limitation is that we collected self-reported pre-pregnancy weight at the initial prenatal visit. However, among 343 women who had weight recorded in the medical record in the 3 months before their last menstrual period, the association between self-reported and clinically measured weights was linear (r = 0.997) (39). 6) Finally, we did not measure maternal cognition, an important confounder, prior to pregnancy, but as intelligence is a trait that is stable over time we do not believe that the timing of this assessment makes any difference.

CONCLUSION

In this cohort of generally healthy children, maternal pre-pregnancy obesity was significantly but modestly associated with lower visual motor abilities. This modest association was mediated, in part, by maternal inflammation, especially within the fine motor skills outcome. Future studies should attempt to further delineate biological mechanisms by which maternal obesity may influence fetal and postnatal brain development and affect cognitive outcomes.

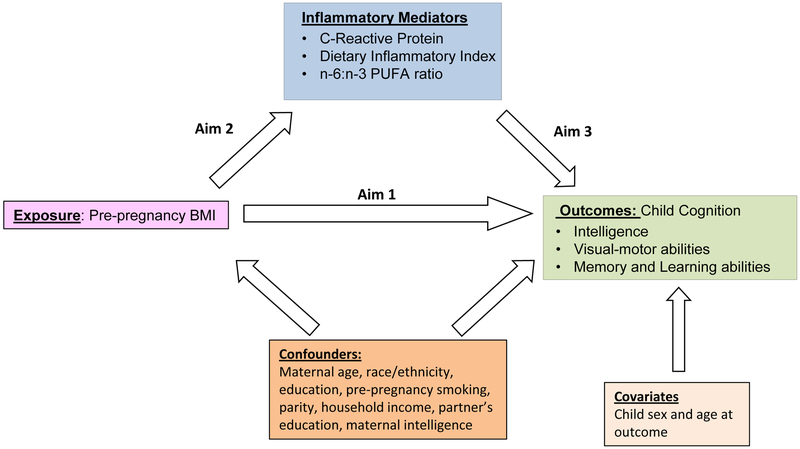

Figure 1.

Directed acyclic diagram representing potential mediation in the association between pre-pregnancy BMI and adverse child cognitive development. BMI: Body Mass Index. n-6:n-3 PUFA: omega-6:omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Acknowledgments

STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL SUPPORT: Project Viva is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 HD034568, R01 ES016314, and R01 AI102960. S.S. is supported by the NIH K23 HD074648. C.M.D. was supported by the NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Training Grant 4T32 HD007466-20.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors do not declare any conflicts of interest.

CATEGORY OF STUDY: Clinical Investigation

REFERENCES

- 1.Fisher SC, Kim SY, Sharma AJ, Rochat R, Morrow B. Is obesity still increasing among pregnant women? Prepregnancy obesity trends in 20 states, 2003-2009. Prev Med. 2013;56:372–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity Among Adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2284–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Burg JW, Sen S, Chomitz VR, Seidell JC, Leviton A, Dammann O. The role of systemic inflammation linking maternal BMI to neurodevelopment in children. Pediatr Res. 2016;79:3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edlow AG. Maternal obesity and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in offspring. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37:95–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aye IL, Lager S, Ramirez VI, Gaccioli F, et al. Increasing maternal body mass index is associated with systemic inflammation in the mother and the activation of distinct placental inflammatory pathways. Biol Reprod. 2014;90:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan EL, Grayson B, Takahashi D, et al. Chronic consumption of a high-fat diet during pregnancy causes perturbations in the serotonergic system and increased anxiety-like behavior in nonhuman primate offspring. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3826–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan EL, Riper KM, Lockard R, Valleau JC. Maternal high-fat diet programming of the neuroendocrine system and behavior. Horm Behav. 2015;76:153–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sen S, Iyer C, Meydani SN. Obesity during pregnancy alters maternal oxidant balance and micronutrient status. J Perinatol. 2014;34:105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tozuka Y, Wada E, Wada K. Diet-induced obesity in female mice leads to peroxidized lipid accumulations and impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis during the early life of their offspring. FASEB J. 2009;23:1920–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tozuka Y, Kumon M, Wada E, Onodera M, Mochizuki H, Wada K. Maternal obesity impairs hippocampal BDNF production and spatial learning performance in young mouse offspring. Neurochem Int. 2010;57:235–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilbo SD, Tsang V. Enduring consequences of maternal obesity for brain inflammation and behavior of offspring. FASEB J. 2010;24:2104–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang SS, Kurti A, Fair DA, Fryer JD. Dietary intervention rescues maternal obesity induced behavior deficits and neuroinflammation in offspring. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:156–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isaacs E, Oates J. Nutrition and cognition: assessing cognitive abilities in children and young people. Eur J Nutr. 2008;47(Suppl 3):4–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordner ZA, Tamashiro KL. Effects of high-fat diet exposure on learning & memory. Physiol Behav. 2015;152(Pt B):363–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oken E, Baccarelli AA, Gold DR, Kleinman KP, Litonjua AA, De Meo D, et al. Cohort profile: project viva. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donahue SM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Olsen SF, Gold DR, Gillman MW, Oken E. Associations of maternal prenatal dietary intake of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids with maternal and umbilical cord blood levels. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2009;80:289–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.James MJ, Gibson RA, Cleland LG. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory mediator production. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(1 Suppl):343S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang LG, Song ZX, Yin H, et al. Low n-6/n-3 PUFA Ratio Improves Lipid Metabolism, Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Function in Rats Using Plant Oils as n-3 Fatty Acid Source. Lipids. 2016;51:49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fawzi WW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Rich-Edwards JW, Willett WC, Gillman MW. Calibration of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire in early pregnancy. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:754–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oken E, Kleinman KP, Olsen SF, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. Associations of seafood and elongated n-3 fatty acid intake with fetal growth and length of gestation: results from a US pregnancy cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:774–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sen S, Rifas-Shiman SL, Shivappa N, et al. Dietary Inflammatory Potential during Pregnancy Is Associated with Lower Fetal Growth and Breastfeeding Failure: Results from Project Viva. J Nutr. 2016;146:728–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabung FK, Steck SE, Ma Y, et al. Changes in the Inflammatory Potential of Diet Over Time and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Postmenopausal Women. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:514–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belfort MB, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman KP, et al. Infant feeding and childhood cognition at ages 3 and 7 years: Effects of breastfeeding duration and exclusivity. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:836–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valeri L, Vanderweele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol Methods. 2013;18:137–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeung EH, Sundaram R, Ghassabian A, Xie Y, Buck Louis G. Parental Obesity and Early Childhood Development. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20161459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casas M, Chatzi L, Carsin AE, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy overweight and obesity, and child neuropsychological development: two Southern European birth cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:506–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basatemur E, Gardiner J, Williams C, Melhuish E, Barnes J, Sutcliffe A. Maternal prepregnancy BMI and child cognition: a longitudinal cohort study. Pediatrics. 2013;131:56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brion MJ, Zeegers M, Jaddoe V, et al. Intrauterine effects of maternal prepregnancy overweight on child cognition and behavior in 2 cohorts. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e202–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hinkle SN, Schieve LA, Stein AD, Swan DW, Ramakrishnan U, Sharma AJ. Associations between maternal prepregnancy body mass index and child neurodevelopment at 2 years of age. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012;36:1312–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jo H, Schieve LA, Sharma AJ, Hinkle SN, Li R, Lind JN. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and child psychosocial development at 6 years of age. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e1198–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoon BH, Romero R, Park JS, et al. Fetal exposure to an intra-amniotic inflammation and the development of cerebral palsy at the age of three years. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:675–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCloskey K, Ponsonby AL, Collier F, et al. The association between higher maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and increased birth weight, adiposity and inflammation in the newborn. Pediatr Obes. 10.1111/ijpo.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White CL, Pistell PJ, Purpera MN, Gupta S, Fernandez-Kim SO, Hise TL, et al. Effects of high fat diet on Morris maze performance, oxidative stress, and inflammation in rats: contributions of maternal diet. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;35:3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaillard R, Rifas-Shiman SL, Perng W, Oken E, Gillman MW. Maternal inflammation during pregnancy and childhood adiposity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24:1320–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goines PE, Croen LA, Braunschweig D, et al. Increased midgestational IFN-gamma, IL-4 and IL-5 in women bearing a child with autism: A case-control study. Mol Autism. 2011:2392–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernard JY, De Agostini M, Forhan A, et al. The dietary n6:n3 fatty acid ratio during pregnancy is inversely associated with child neurodevelopment in the EDEN mother-child cohort. J Nutr. 2013;143:1481–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao WQ, Alkon DL. Role of insulin and insulin receptor in learning and memory. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;177:125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panagos PG, Vishwanathan R, Penfield-Cyr A, et al. Breastmilk from obese mothers has pro-inflammatory properties and decreased neuroprotective factors. J Perinatol. 2016;36:284–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Provenzano AM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Herring SJ, Rich-Edwards JW, Oken E. Associations of maternal material hardships during childhood and adulthood with pre-pregnancy weight, gestational weight gain, and postpartum weight retention. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015; 24:563–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]