Abstract

Pharmacotherapies for fibromyalgia treatment are lacking. This study examined the antinociceptive and antidepressant-like effects of imidazoline I2 receptor (I2R) agonists in a reserpine-induced model of fibromyalgia in rats. Rats were treated for three days with vehicle or reserpine. The von Frey filament test was used to assess the antinociceptive effects of I2 receptor agonists, and the forced swim test was used to assess the antidepressant-like effects of these drugs. 2-BFI (3.2 – 10 mg/kg, i.p.), phenyzoline (17.8 – 56 mg/kg, i.p.) and CR4056 (3.2 – 10 mg/kg, i.p.) all dose-dependently produced significant antinociceptive effects, which were attenuated by the I2R antagonist idazoxan. Only CR4056 significantly reduced the immobility time in the forced swim test in both vehicle- and reserpine-treated rats. These data suggest that I2R agonists may be useful to treat fibromyalgia-related pain and comorbid depression.

Keywords: Imidazoline I2 receptor, pain, reserpine, 2-BFI, phenyzoline, CR4056, forced swim test, pain, nociception, rat

Introduction

Chronic pain is a leading healthcare challenge that affects 100 million Americans and costs society over $600 billion each year, with a severe lack of effective pharmacotherapies (Kissin, 2010; NIH, 2013). Among painful conditions, fibromyalgia is a prevalent disorder characterized by chronic widespread pain and complex comorbid symptoms which include affective disorders like depression. Fibromyalgia has been reported to affect 1.3–8% of the general population (Branco et al., 2010; Lawrence et al., 1998; Theoharides et al., 2015), and similar to other pain disorders is commonly resistant to treatment (Ablin et al., 2008; Chinn et al., 2016; Sluka and Clauw, 2016). One hypothesis for the pain symptoms in fibromyalgia is central sensitization, in which the central nervous system becomes over-reactive to stimuli (Price et al., 2002; Staud and Rodriguez, 2006). While the molecules and mechanisms responsible for central sensitization are yet to be fully understood, biogenic amine dysfunction may play an underlying role (Ablin et al., 2008; Arnold, 2006; Wood et al., 2007).

Norepinephrine (NE) and serotonin (5-HT) are the main neurotransmitters involved in descending pain inhibition (Mense, 2000), and dopamine (DA) is also thought to be important for central nervous system (CNS) pain control (Wood, 2008). Therefore, deficient levels of these neurotransmitters may result in hypersensitivity. In support of this hypothesis DA, NE, and 5-HT levels are lower in cerebrospinal fluid from fibromyalgia patients as compared to healthy controls (Russell et al., 1992). To this end, a rodent model has been characterized in which to evaluate potential pharmacotherapies for fibromyalgia (Nagakura et al., 2009). Treatment with reserpine, which depletes biogenic amines from the nervous system by irreversibly binding to vesicular monoamine transporters, caused mechanical hypersensitivity and increased time spent immobile in the forced swim test (FST), two behavioral endpoints that are often used to evaluate potential analgesic and antidepressant drugs (Huang et al., 2004; Vetulani et al., 1986). The pain-related behaviors were reduced by pregabalin, duloxetine, and pramipexole, but not the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac, thus showing that this animal model responds to similar treatments as fibromyalgia in humans (i.e., predictive validity) (Nagakura et al., 2009).

Agonists selective for the imidazoline I2 receptor (I2R) have been established as promising candidates for the treatment of chronic pain in many preclinical studies. I2R agonists significantly reduce mechanical hypersensitivity in preclinical models of chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain (Ferrari et al., 2011; Li et al., 2014; Siemian et al., 2016a), and also produce additive to synergistic enhancement of opioid analgesia (Siemian et al., 2016b; Thorn et al., 2015). More importantly, a recently finished phase II clinical trial showed clear analgesic efficacy of an I2R agonist CR4056 in patients with osteoarthritis (Rovati et al., 2017), demonstrating strong feasibility of developing I2R agonists as analgesics to treat chronic pain. Interestingly, some I2R agonists have also been demonstrated to decrease immobility time in the forced swim test in rodents, suggesting that they may also exert antidepressant-like activity (Finn et al., 2003; Meregalli et al., 2012; Nutt et al., 1995). While a comprehensive understanding of I2R localization and signaling pathways is yet unachieved, current data suggest that one population of I2Rs are allosteric inhibitory binding domains on monoamine oxidase (MAO) A and B (Bour et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2007; Raddatz et al., 1999; Ramsay, 2016). Thus, heightened levels of monoamines following in vivo I2R agonist administration may result from the inhibition of their breakdown and likely account for some I2R-mediated behavioral effects (Ferrari et al., 2011; Nutt et al., 1995; Sastre-Coll et al., 1999, 2001; Siemian et al., 2018). As such, I2R agonists may hold value in treating conditions such as fibromyalgia for which monoaminergic drugs have demonstrated efficacy.

This study examined the antinociceptive effects of selective I2R agonists using the von Frey filament test in adult male rats treated with reserpine. Idazoxan was administered as pretreatment to verify the pharmacological specificity of I2Rs in the antinociceptive effects. Furthermore, we examined the effects of I2R ligands on immobility time in the forced swim test (FST) in both saline- and reserpine-treated rats to explore potential antidepressant-like effects.

Methods

Subjects

200 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Sprague-Dawley Inc., Indianapolis, IN), at least 8 weeks old and weighing at least 250 g were housed under conditions described previously (Siemian et al., 2016b). Water and standard rodent chow were always available except during testing. Animals were maintained and experiments were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York (Buffalo, NY), and with the 2011 Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources on Life Sciences, National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC). Rats were handled for at least two days before testing.

Mechanical Nociception Test and Reserpine Treatment

Mechanical nociception was measured using von Frey filaments as previously described (Siemian et al., 2016b). Briefly, rats (n = 5–6) were placed in elevated plastic chambers with a wire mesh floor and allowed to habituate. Filaments were then applied perpendicularly to the medial plantar surface of the right hind paw from below the mesh floor in an ascending order of filament force, beginning with the lowest filament (1.0 g) and ending with the highest filament (26 g). Stronger filaments (> 26 g) lifted hindpaws in naïve rats and did not reflect a nociceptive reaction. A filament was applied until buckling occurred for approximately 2 s, and the lowest force filament to elicit a paw withdrawal was recorded. For the time course of reserpine-induced mechanical hypersensitivity, a treatment regimen previously characterized to induce tactile hypersensitivity (1 mg/kg reserpine, s.c. for three consecutive days) was used (Nagakura et al., 2009). Paw withdrawal threshold was measured before reserpine treatment as well as 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, and 21 days post-treatment. This timeline was designed to demonstrate the temporal changes of the paw withdrawal threshold before and after reserpine treatments and the successful establishment of the model. In all subsequent experiments, because the paw withdrawal threshold change was most prominent 3 days after the last reserpine treatment, drug tests were always conducted on day 3 post-reserpine. For the drug tests, behavioral measurements were taken immediately before and every 15 min after drug injection for 120 min. When drug combinations were studied, the α2/I2 receptor antagonist idazoxan was administered 10 min prior to the other drug. The dose of idazoxan (3.2 mg/kg) was selected based on our previous studies, which showed that this dose is sufficient to block the antinociceptive effects of I2 receptor agonists but has no apparent behavioral effects when studied alone (Li et al., 2014). Experimenters were well trained and blinded to drug treatments to minimize bias.

Forced Swim Test

For the forced swim test (Detke et al., 1995; France et al., 2009; Porsolt et al., 1977), rats were placed in a transparent plexiglas cylinder (20 cm diameter × 40 cm high) containing water (25±1°C, 30 cm deep). On the first day of the experiment, the rat was placed in the cylinder for 15 min, and 24 h later it was placed back into the cylinder for a 6 min test; for reserpine-treated rats the 6 min test was conducted on day 3 after the reserpine treatment regimen (1 mg/kg, s.c. for three consecutive days). Drugs or saline were administered 23, 9, and 1 h before the test. During the test, the rats were videotaped for later scoring by two observers blinded to the treatment condition. The first minute of the test was disregarded and the time of immobility (s) of each rat in the last 5 minutes was scored. The inter-rater reliability was 0.92.

Drugs

2-BFI hydrochloride, phenyzoline oxalate, and CR4056 were synthesized according to standard procedures (Ishihara and Togo, 2007; Jarry et al., 1997). These drugs were used in this study because they were extensively studied in this laboratory and the dose ranges across a battery of behavioral assays have been well described previously (Thorn et al., 2015; 2016; Siemian et al., 2018). Idazoxan hydrochloride and reserpine were purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Imipramine hydrochloride was purchased from Cayman (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI). All drugs were dissolved in 0.9 % saline except CR4056 which was dissolved in 20% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in saline and reserpine which was dissolved in 0.5% acetic acid in saline. All drugs were injected at a volume of 1 ml/kg i.p. except reserpine which was administered s.c.

Data Analyses

Data were plotted and analyzed using GraphPad Prim version 7 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. The difference in paw withdrawal threshold (g) between reserpine- and vehicle-treated rats on each testing day was compared using two-way mixed-model ANOVA (treatment × time), with time as the within-subject factor. Drug effects in reserpine-treated rats were analyzed using two-way mixed-model ANOVA (treatment × time), with time as the within-subject factor followed by Bonferroni’s post-test. Immobility time (s) in the forced swim test was analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-test or unpaired Student’s unpaired t-test where appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Results

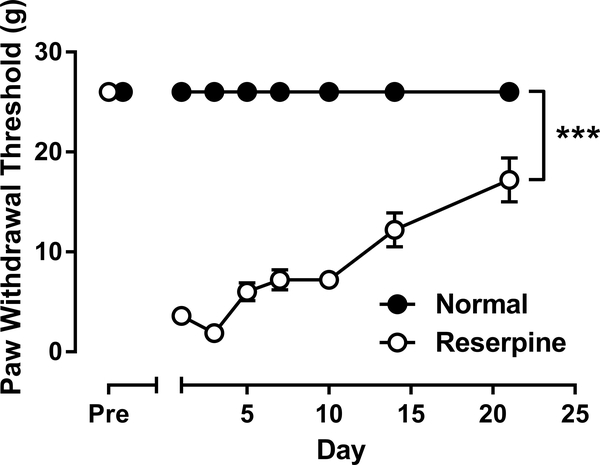

As shown in Fig. 1, reserpine treatment produced significant mechanical allodynia that lasted for at least 20 days. Two-way mixed-model ANOVA, with time entered as the repeated measure factor, revealed a significant reserpine × day interaction (F(7, 56) = 51.92, p < 0.001) with significant main effects of both reserpine treatment (F(1, 8) = 1219, p < 0.001) and time (F(7, 56) = 51.92, p < 0.001). After reserpine treatment, PWT gradually recovered towards the pre-reserpine value (one-way repeated measures ANOVA: F(6, 28) = 19.44, p < 0.001).The most pronounced allodynic effect was apparent on day 3 after reserpine treatment, when PWT was 1.9 ± 0.6 g (as compared to the baseline PWT value of 26 g).

Fig. 1.

Effects of three-day reserpine treatment on mechanical hypersensitivity. Vertical axis: paw withdrawal threshold in g. Horizontal axis: the day relative to reserpine treatment. ***P < 0.001.

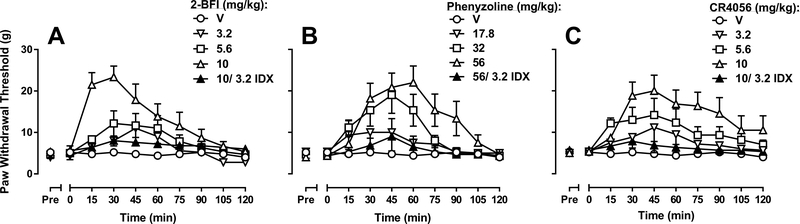

As shown in Fig. 2, all three I2R agonists tested showed dose- and time-dependent antiallodynic effect when the drug effect was tested on day 3 post-reserpine. 2-BFI dose-dependently increased paw withdrawal threshold. Two-way mixed-model ANOVA revealed a significant 2-BFI × time interaction (F(27, 162) = 5.40, p < 0.001) with significant main effects of both 2-BFI (F(3, 18) = 6.19, p < 0.01) and time (F(9, 162) = 20.14, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). Bonferroni’s post-tests analysis revealed that 5.6 mg/kg 2-BFI produced significant effects 30–60 min following injection and 10 mg/kg 2-BFI produced significant effects 15–75 min following injection as compared to vehicle (p < 0.05). Pretreatment with 3.2 mg/kg idazoxan significantly attenuated the antinociceptive effects of 10 mg/kg 2-BFI, with a significant idazoxan × time interaction (F(9, 81) = 10.39, p < 0.001) and significant main effects of both idazoxan (F(1, 9) = 7.27, p < 0.05) and time (F(9, 81) = 15.97, p<0.001). Phenyzoline also dose-dependently increased paw withdrawal threshold. Two-way mixed-model ANOVA revealed a significant phenyzoline × time interaction (F(27, 171) = 4.55, p < 0.001) with significant main effects of both phenyzoline (F(3, 19) = 3.34, p < 0.05) and time (F(9, 171) = 17.4, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). Bonferroni’s post-tests analysis revealed that 32 mg/kg phenyzoline produced significant effects 30–60 min following injection and 56 mg/kg phenyzoline produced significant effects 30–90 min following injection as compared to vehicle. Pretreatment with 3.2 mg/kg idazoxan significantly attenuated the antinociceptive effects of 56 mg/kg phenyzoline, with a significant idazoxan × time interaction (F(9, 90) = 6.00, p < 0.001) and significant main effects of both idazoxan (F(1, 10) = 7.36, p < 0.05) and time (F(9, 90) = 12.1, p < 0.001). Likewise, CR4056 dose-dependently increased paw withdrawal threshold. Two-way mixed-model ANOVA revealed a significant CR4056 × time interaction (F(27, 171) = 2.43, p < 0.001) with significant main effects of both CR4056 (F(3, 19) = 4.22, p < 0.05) and time (F(9, 171) = 10.24, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2C). Bonferroni’s post-tests revealed that 5.6 mg/kg CR4056 produced significant effects 30–60 min following injection and 10 mg/kg CR4056 produced significant effects 30–90 min following injection as compared to vehicle. Pretreatment with 3.2 mg/kg idazoxan significantly attenuated the antinociceptive effects of 10 mg/kg CR4056, with a significant idazoxan × time interaction (F(9, 90) = 4.95, p < 0.001) and significant main effects of both idazoxan (F(1, 10) = 7.60, p < 0.05) and time (F(9, 90) = 6.96, p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Effects of (A) 2-BFI, (B) phenyzoline, and (C) CR4056 on reserpine-induced mechanical hypersensitivity, on day three following reserpine treatment. Vertical axes: paw withdrawal threshold. Horizontal axes: time following drug administration in min.

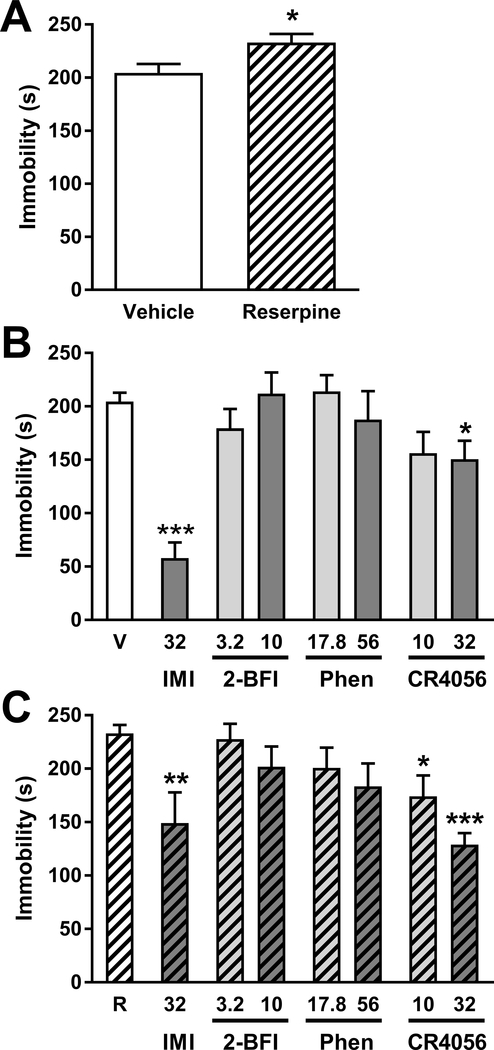

Fig. 3 showsed the drug effects in the forced swim test. As shown in Fig. 3A, saline-treated rats displayed 204.5 ± 8.4 s of immobility time during the 5 min scoring period, which was significantly increased by reserpine treatment (t(14) = 2.46, p < 0.05). In vehicle-treated rats, 32 mg/kg imipramine significantly reduced immobility time (unpaired t-test t(14) = 8.72, p < 0.001). Among I2R ligands, CR4056 reduced immobility time according to one-way ANOVA (F(2, 21) = 3.47, p < 0.05), with Dunnett’s post-test revealing significant effects at a dose of 32 mg/kg as compared to vehicle, but 2-BFI and phenyzoline treatment did not significantly affect immobility time. In reserpine-treated rats, 32 mg/kg imipramine significantly reduced immobility time (t(11) = 3.44, p < 0.01). Among I2R ligands, only CR4056 reduced immobility time (F(2, 21) = 14.48, p < 0.001) with significant effects at doses of 10 mg/kg and 32 mg/kg as compared to vehicle according to Dunnett’s post-test.

Fig. 3.

Effects of (A) reserpine treatment on immobility time in the forced swim test, and the effects of I2R agonists on immobility time in (B) normal and (C) reserpine-treated rats. Vertical axes: time spent immobile in s. Horizontal axes: drug treatments. V, vehicle; R, reserpine; IMI, imipramine; Phen, phenyzoline. *P < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

The primary findings of the current study were that several I2R agonists produced dose-dependent mechanical antinociception in the reserpine-induced pain model in rats. Pretreatment with the I2R antagonist idazoxan attenuated the antinociceptive effect of each compound. However, when the effects of I2R agonists on immobility time of saline- or reserpine-treated rats in the FST were assessed, only CR4056 produced significant effects. Since reserpine-treated rats demonstrate similar biochemical and phenotypic features to fibromyalgia in humans, I2R agonists may represent a novel treatment for fibromyalgia pain and potentially comorbid depression. It should be noted that because only male rats were used in this study and the prevalence of fibromyalgia is higher in women than in men (Haviland et al., 2011), it is possible that the results can only be applied to a specific population.

Fibromyalgia is a serious public health problem affecting up to 8% of the general population and is characterized by widespread chronic pain and often comorbid depression (Branco et al., 2010; Lawrence et al., 1998; Theoharides et al., 2015). Similar to other forms of chronic pain, fibromyalgia is commonly resistant to treatment and thus novel therapies are urgently needed. Since one underlying feature of fibromyalgia pain is thought to be monoamine dysfunction, fibromyalgia symptoms may respond more positively to treatment with drugs that restore monoamine function. For example, MAO inhibitors such as moclobemide are effective to alleviate fibromyalgia pain and other symptoms such as fatigue (Häuser et al., 2009). Accumulating preclinical data have established I2R agonists as effective antinociceptive agents (Li et al., 2014; Siemian et al., 2016b) which may function by reversibly inhibiting MAO A and B (Jones et al., 2007; McDonald et al., 2010) to increase monoamine levels in various CNS regions (Ferrari et al., 2011; Nutt et al., 1995). To examine the therapeutic potential of I2R agonists to treat fibromyalgia, we tested several of these compounds in the reserpine-induced pain model, which significantly depletes CNS monoamines in rats to induce a fibromyalgia-like conditions (Nagakura et al., 2009). Consistent with previous reports, a three-day reserpine treatment regimen produced marked hypersensitivity to mechanical stimuli, which was most pronounced on day three following the treatment. 2-BFI, phenyzoline, and CR4056 each produced dose-dependent antinociception that was attenuated by the I2R antagonist idazoxan, suggesting that the effect was primarily mediated by I2 receptors. I2R agonists do not alter the normal nociceptive responses as they are ineffective in assays that study acute nociception such as tail flick or paw withdrawal (see Li, 2018 for a review). Given the clear effects of I2R agonists in enhancing monoaminergic function and the critical role the monoaminergic system plays in mediating I2R agonist-induced antinociceptive effects in animal models of chronic pain (Ferrari et al., 2011; Siemian et al., 2018), the antinociception produced by the I2R agonists in the current study may likely be explained by the temporary inhibition of MAO enzymes to restore monoaminergic transmission in descending pain inhibitory systems. Thus, the I2R appears to be a candidate target for future fibromyalgia pharmacotherapies.

Since fibromyalgia pain patients often suffer comorbid depression, and since reserpine produces behavioral changes that are responsive to antidepressants in rats (e.g., increased immobility in FST) (Nagakura et al., 2009), we also assessed the effects of I2R agonists on behavior in the forced swim test, a widely-used model for detecting antidepressant-like drug activity (Porsolt et al., 1977; Ye et al., 2012; Han et al., 2013). Similar to previous reports, reserpine treatment produced a significant increase in immobility time on day three after reserpine treatment, indicative of a depressive-like condition (Nagakura et al., 2009). However, in both the reserpine-treated and control rats, the only I2R agonist to reduce immobility time was CR4056. This is partially in contrast to some previous reports where, for example, 2-BFI had been reported to reduce immobility time (Nutt et al., 1995). While discrepancies between the behavioral profiles of I2R agonists effects are currently difficult to explain, they are not the first to be reported. For example, I2R agonists produce different patterns of antinociceptive interactions when paired with opioids (Lanza et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Thorn et al., 2015) and differentially affect flinching behavior in the formalin test (Thorn et al., 2016). One likely reason for the divergent effects of these agonists is that I2Rs are heterogeneous and I2R agonists potentially bind to at least four proteins (Keller and Garcia-Sevilla, 2015; Kimura et al., 2009; Olmos et al., 1999) which may be differentially modulated by different I2R ligands. In the case of the present results, 2-BFI, phenyzoline, and CR4056 all have been shown to be highly selective to I2 receptors via radioligand counter screening (Hudson et al., 1999; Ferrari et al., 2011; Qiu et al., 2015). Given that the radioligands used in all the binding studies are [3H] idazoxan (saturated by norepinephrine first to mask adrenergic receptors) or [3H] 2-BFI, these I2 receptor agonists may recognize the same I2 receptor proteins as idazoxan but cannot be further discriminated. Therefore, it is possible that these I2 receptor agonists may act on one common population of I2Rs to relieve pain (e.g., MAO binding domain), but otherwise differentially engage other I2R populations to lead to their distinct behavioral effects. That other monoaminergic drugs produce antinociception and improve mood via different mechanisms lends credence to this possibility (Max et al., 1987). Similarly, as noted in clinical studies, the doses and duration of treatment with antidepressant drugs required to achieve analgesia are generally less than those required for depression treatment (Goldstein et al., 2005; McCleane, 2008). Thus, 2-BFI and phenyzoline may, in fact, produce antidepressant-like effects but simply require longer chronicity of treatment before the effect is apparent.

In summary, this study demonstrated that three I2R agonists, 2-BFI, phenyzoline, and CR4056 all produced antinociception in a rat model of fibromyalgia induced by biogenic amine depletion with reserpine. While reserpine treatment increased immobility time in the forced swim test, only CR4056 decreased immobility time among I2R agonists. These data suggest that I2R agonists may warrant further investigation for the treatment of fibromyalgia-related chronic pain.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (Award no. R01DA034806). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- Ablin J, Neumann L, Buskila D (2008) Pathogenesis of fibromyalgia - a review. Joint Bone Spine 75: 273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LM (2006) Biology and therapy of fibromyalgia. New therapies in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res Ther 8: 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bour S, Iglesias-Osma MC, Marti L, Duro P, Garcia-Barrado MJ, Pastor MF, Prevot D, Visentin V, Valet P, Moratinos J, Carpene C (2006) The imidazoline I2-site ligands BU 224 and 2-BFI inhibit MAO-A and MAO-B activities, hydrogen peroxide production, and lipolysis in rodent and human adipocytes. Eur J Pharmacol 552: 20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco JC, Bannwarth B, Failde I, Abello Carbonell J, Blotman F, Spaeth M, Saraiva F, Nacci F, Thomas E, Caubere JP, Le Lay K, Taieb C, Matucci-Cerinic M (2010) Prevalence of fibromyalgia: a survey in five European countries. Semin Arthritis Rheum 39: 448–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinn S, Caldwell W, Gritsenko K (2016) Fibromyalgia Pathogenesis and Treatment Options Update. Curr Pain Headache Rep 20: 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detke MJ, Rickels M, Lucki I (1995) Active behaviors in the rat forced swimming test differentially produced by serotonergic and noradrenergic antidepressants. Psychopharmacology 121: 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari F, Fiorentino S, Mennuni L, Garofalo P, Letari O, Mandelli S, Giordani A, Lanza M, Caselli G (2011) Analgesic efficacy of CR4056, a novel imidazoline-2 receptor ligand, in rat models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. J Pain Res 4: 111–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn DP, Marti O, Harbuz MS, Valles A, Belda X, Marquez C, Jessop DS, Lalies MD, Armario A, Nutt DJ, Hudson AL (2003) Behavioral, neuroendocrine and neurochemical effects of the imidazoline I2 receptor selective ligand BU224 in naive rats and rats exposed to the stress of the forced swim test. Psychopharmacology 167: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France CP, Li JX, Owens WA, Koek W, Toney GM, Daws LC (2009) Reduced effectiveness of escitalopram in the forced swimming test is associated with increased serotonin clearance rate in food-restricted rats. Intl J Neuropsychopharmacol 12: 731–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DJ, Lu Y, Detke MJ, Lee TC, Iyengar S (2005) Duloxetine vs. placebo in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy. Pain 116: 109–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Hu J, Shen J, Gao Y, Lu Y, Wang T (2013) Neuroprotective effect of hydroxysafflor yellow A on 6-hydroxydopamine-induced Parkinson’s disease in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 14:83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häuser W, Bernardy K, Uçeyler N, Sommer C (2009) Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with antidepressants: a meta-analysis. JAMA 301:198–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haviland MG, Banta JE, Przekop P (2011) Fibromyalgia: prevalence, course, and co-morbidities in hospitalized patients in the United States, 1999–2007. Clin Exp Rheumatol 29(6 Suppl 69):S79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang QJ, Jiang H, Hao XL, Minor TR (2004) Brain IL-1 beta was involved in reserpine-induced behavioral depression in rats. Acta pharmacol Sin 25: 293–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson AL, Gough R, Tyacke R, Lione L, Lalies M, Lewis J, Husbands S, Knight P, Murray F, Hutson P, Nutt DJ. Novel selective compounds for the investigation of imidazoline receptors. Ann N Y Acad Sci 881:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara M, Togo H (2007) Direct oxidative conversion of aldehydes and alcohols to 2-imidazolines and 2-oxazolines using molecular iodine. Tetrahedron 63: 1474–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Jarry C, Forfar I, Bosc J, Renard P, Scalbert E, Guardiola B (1997) 5-(Aryloxymethyl)oxazoline. US Patent 5,686,477 Adir e Compagnie.

- Jones TZ, Giurato L, Guccione S, Ramsay RR (2007) Interactions of imidazoline ligands with the active site of purified monoamine oxidase A. FEBS J 274: 1567–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller B, Garcia-Sevilla JA (2015) Immunodetection and subcellular distribution of imidazoline receptor proteins with three antibodies in mouse and human brains: Effects of treatments with I1- and I2-imidazoline drugs. J Psychopharmacol 29: 996–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura A, Tyacke RJ, Robinson JJ, Husbands SM, Minchin MC, Nutt DJ, Hudson AL (2009) Identification of an imidazoline binding protein: creatine kinase and an imidazoline-2 binding site. Brain Res 1279: 21–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissin I (2010) The development of new analgesics over the past 50 years: a lack of real breakthrough drugs. Anesth Analg 110: 780–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza M, Ferrari F, Menghetti I, Tremolada D, Caselli G (2014) Modulation of imidazoline I2 binding sites by CR4056 relieves postoperative hyperalgesia in male and female rats. Br J Pharmacol 171: 3693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, Deyo RA, Felson DT, Giannini EH, Heyse SP, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG, Liang MH, Pillemer SR, Steen VD, Wolfe F (1998) Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum 41: 778–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JX (2018) Imidazoline I2 receptors: an update. Pharmacol Ther 178: 48–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J-X, Thorn DA, Qiu Y, Peng B-W, Zhang Y (2014) Antihyperalgesic effects of imidazoline I(2) receptor ligands in rat models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Brit J Pharmacol 171: 1580–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Max MB, Culnane M, Schafer SC, Gracely RH, Walther DJ, Smoller B, Dubner R (1987) Amitriptyline relieves diabetic neuropathy pain in patients with normal or depressed mood. Neurology 37: 589–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleane G (2008) Antidepressants as analgesics. CNS Drugs 22: 139–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald GR, Olivieri A, Ramsay RR, Holt A (2010) On the formation and nature of the imidazoline I2 binding site on human monoamine oxidase-B. Pharmacol Res 62: 475–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mense S (2000) Neurobiological concepts of fibromyalgia--the possible role of descending spinal tracts. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl 113: 24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meregalli C, Ceresa C, Canta A, Carozzi VA, Chiorazzi A, Sala B, Oggioni N, Lanza M, Letari O, Ferrari F, Avezza F, Marmiroli P, Caselli G, Cavaletti G (2012) CR4056, a new analgesic I2 ligand, is highly effective against bortezomib-induced painful neuropathy in rats. J Pain Res 5: 151–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagakura Y, Oe T, Aoki T, Matsuoka N (2009) Biogenic amine depletion causes chronic muscular pain and tactile allodynia accompanied by depression: A putative animal model of fibromyalgia. Pain 146: 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH (2013) Pain in America NINDS Chronic Pain Information Page, Bethesda, MD

- Nutt DJ, French N, Handley S, Hudson A, Husbands S, Jackson H, Jordan S, Lalies MD, Lewis J, Lione L, et al. (1995) Functional studies of specific imidazoline-2 receptor ligands. Ann N Y Acad Sci 763: 125–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmos G, Alemany R, Boronat MA, Garcia-Sevilla JA (1999) Pharmacologic and molecular discrimination of I2-imidazoline receptor subtypes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 881: 144–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsolt RD, Le Pichon M, Jalfre M (1977) Depression: a new animal model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Nature 266: 730–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DD, Staud R, Robinson ME, Mauderli AP, Cannon R, Vierck CJ (2002) Enhanced temporal summation of second pain and its central modulation in fibromyalgia patients. Pain 99: 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Zhang Y, Li JX (2015) Discriminative stimulus effects of the imidazoline I2 receptor ligands BU224 and phenyzoline in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 749: 133–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raddatz R, Savic SL, Lanier SM (1999) Imidazoline binding domains on MAO-B. Localization and accessibility. Ann N Y Acad Sci 881: 26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay RR (2016) Molecular aspects of monoamine oxidase B. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 69: 81–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovati LC, Brambilla N, Blicharski T, Probert NJ, Vitalini C, Giacovelli G, Girolami F, D’Amato M (2017) A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase II clinical trial of the first-in-class imidazoline-2 receptor ligand CR4056 in pain from knee osteoarthritis and disease phenotypes. Arthritis Rheumatol 69 (suppl 10). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell IJ, Vaeroy H, Javors M, Nyberg F (1992) Cerebrospinal fluid biogenic amine metabolites in fibromyalgia/fibrositis syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 35: 550–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre-Coll A, Esteban S, Garcia-Sevilla JA (1999) Effects of imidazoline receptor ligands on monoamine synthesis in the rat brain in vivo. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 360: 50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre-Coll A, Esteban S, Miralles A, Zanetti R, Garcia-Sevilla JA (2001) The imidazoline receptor ligand 2-(2-benzofuranyl)-2-imidazoline is a dopamine-releasing agent in the rat striatum in vivo. Neurosci Lett 301: 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemian JN, Li J, Zhang Y, Li JX (2016a) Interactions between imidazoline I2 receptor ligands and acetaminophen in adult male rats: antinociception and schedule-controlled responding. Psychopharmacology 233: 873–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemian JN, Obeng S, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Li JX (2016b) Antinociceptive Interactions between the Imidazoline I2 Receptor Agonist 2-BFI and Opioids in Rats: Role of Efficacy at the mu-Opioid Receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 357: 509–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemian JN, Wang K, Zhang Y, Li JX (2018) Mechanisms of imidazoline I2 receptor agonist-induced antinociception in rats: involvement of monoaminergic neurotransmission. Br J Pharmacol 175:1519–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluka KA, Clauw DJ (2016) Neurobiology of fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain. Neuroscience 338: 114–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staud R, Rodriguez ME (2006) Mechanisms of disease: pain in fibromyalgia syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2: 90–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides TC, Tsilioni I, Arbetman L, Panagiotidou S, Stewart JM, Gleason RM, Russell IJ (2015) Fibromyalgia syndrome in need of effective treatments. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 355: 255–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn DA, Siemian JN, Zhang Y, Li JX (2015) Anti-hyperalgesic effects of imidazoline I2 receptor ligands in a rat model of inflammatory pain: interactions with oxycodone. Psychopharmacology 232: 3309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn DA, Qiu Y, Jia S, Zhang Y, Li JX (2016) Antinociceptive effects of imidazoline I2 receptor agonists in the formalin test in rats. Behav Pharmacol 27: 377–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetulani J, Antkiewicz-Michaluk L, Rokosz-Pelc A, Michaluk J (1986) Effects of chronically administered antidepressants and electroconvulsive treatment on cerebral neurotransmitter receptors in rodents with ‘model depression’. Ciba Found Symp 123: 234–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PB (2008) Role of central dopamine in pain and analgesia. Expert Rev Neurother 8: 781–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PB, Holman AJ, Jones KD (2007) Novel pharmacotherapy for fibromyalgia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 16: 829–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Hu Z, Du G, Zhang J, Dong Q, Fu F, Tian J (2012) Antidepressant-like effects of the extract from Cimicifuga foetida L. J Ethnopharmacol 144:683–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]