1. Background

Proximal Humerus Fractures (PHF) is a source of a dilemma to most of us. While literature supports conservative treatment,1, 2, 3 there is an increasing trend of surgical intervention in the last 20 years. Recent advances in fixation methods encouraged many to fix them surgically. The initial promise of locking plates & screws could not be fulfilled in older, weak, osteoporotic bones. Varus collapse, screw cut-outs & greater tuberosity non-union are becoming increasingly common.

The intrigue of these fractures can partially be cleared if we understand their bimodal age group presentation. The majority (>80%) of these are fragility fractures, occurring in low demand (often elderly) patients. Weak osteoporotic bones not only break easily but are also difficult to stabilize and are often associated with high failure rates, after the surgery. Younger individuals, however, have stronger bones & fixation provides a stable construct during fracture healing. They have significantly more demands from their shoulder function too. Hence, an accurate reduction is required to achieve efficient biomechanics of the shoulder joint. These patients thus show maximum improvement in post-surgical shoulder function.

2. Evaluation of PHF

A) Clinical evaluation should assess swelling, breach in skin continuity, the possibility of shoulder dislocation and any neurovascular injuries. The axillary nerve is occasionally involved, with a marked displacement of the humeral shaft or with an anterior fracture dislocation.

B) Radiological examination should ideally include a minimum of two views (a true Antero Posterior (AP) and a Lateral view of the glenohumeral joint. While Axillary Lateral view is ideal, very often it cannot be done because arm cannot be abducted. Y Lateral view is an excellent practical alternative in fracture cases. When these radiological views are adequately done, these are sufficient for sound decision making in the majority of cases. As true AP & Y lateral views are not routinely done, the radiographer must be sensitized to obtain proper imaging of the shoulder joint. A computed tomogram (CT) scan is required if these two proper radiographic views are either not possible or available. CT scan provides useful details of the path anatomy of the PHF and is now considered to be the most favored investigation. 3D CT scans are relatively easier to interpret by those who do not treat these cases frequently.

A surgeon must have clear answers to the following questions before making any decision in PHF:

-

1.

Is the humeral head in the glenoid socket? (A posteriorly dislocated head can look deceptively normal even on a good AP view).

-

2.

Is there a posterior tilt? (It can only be seen in a good lateral view).

-

3.

Has the greater tuberosity (GT) moved upwards?

-

4.

Has the greater tuberosity (or a part of it) moved posteriorly? (Only lateral view can show this)

-

5.

Are there signs of medial pillar instability? Medial cortical comminution or marked varus?

3. Decision making

The PHF can be managed by both nonoperative means and with surgery. The absolute indications for surgery include:

-

1.

Dislocated head.

-

2.

Head facing superiorly/posteriorly (though in the socket, but not facing the glenoid).

-

3.

Splitting of head

-

4.

GT is lying above the humeral head or displaced posteriorly.

-

5.

Significant varus angulation of the head (usually indicates severe medial pillar instability & progressive malposition).

-

6.

A significant change of fragments position with conservative treatment, on serial radiographs.

-

7.

Minor displacement of GT, minimal head shaft angulation only in young and high demand individuals. (These include overhead workers like plumbers, electricians, etc)

The management of all the other fracture patterns, except for the indications mentioned above is debatable. These can be treated by either non-operative or operative means, especially in low demand older patients. Cochrane reviews4 and PROpher trial5 have shown that the results of surgery and conservative treatment are almost the same, particularly in the older population for these nonabsolute indications. Coincidently, the majority of PHF (about 50%) fall in this category.

The best indications for conservative treatment (20–30% cases) include:

-

1.

An undisplaced 2 or 3 fragment fracture, in any age group.

-

2.

An undisplaced 2, 3 or 4 fragment fracture, in the older age group.

-

3.

A mild to moderately displaced fracture, where the anesthesia risks are high.

The conservative treatment involves rest to the arm and shoulder in a pouch or a sling for three to four weeks. Passive mobilization can be started as early as the second week. However, weekly serial radiographs must be done in the first three weeks to check for any displacement of the fracture.

4. Operative treatment

There are several ways by which the PHF could be fixed surgically. These include the following:

-

A)

Percutaneous pinning: Though the least invasive, it needs considerable experience and dexterity. It is indicated in mild to moderately displaced fractures where open reduction is not required. A minimum of two Kirschner wires (K wires) must be placed to stabilize each displaced fragment. In comminuted fractures, more K wires may be required to stabilize the fracture. The main contraindications for this technique include a significant displacement or angulation of the fracture fragments and medial cortical comminution.

-

B)Locking plates and screws: Fractures of neck needing an ORIF are best fixed with locking plates and screws. It is also an implant of choice in displaced 3 & 4 part fractures. However, it must be realized that the complication rates are high (20–50%) in the older population. We believe that these failures would be even higher with low volume surgeons. There could be many factors to influence the outcomes in these cases, some of these are beyond and some under the control of the surgeon:

- I) Beyond the Surgeon's control - Almost 80% of these fractures occur in older and severely osteoporotic bones, and hence the purchase of these implants is not great. Hence, the bone void in humeral head must be filled with bone graft (autogenous, allografts or bone substitutes).

- II) Within the Surgeon's control-

-

a)Supporting the weak medial pillar: A weakness in medial pillar below the humeral head could be due to medial comminution, thin cortices, and severe varus deformity. If not supported adequately, it invariably leads to varus collapse of the fracture or screw penetration through the humeral head. A well-positioned calcar screw, fibular strut graft or a small medial plate can prevent this complication.

-

b)Repairing the ‘bony’ rotator cuff: The crux of PHF surgery is to bring back the fractured GT in its anatomical position, to achieve satisfactory rotator cuff function. Nonunion of GT is the most frequent cause of inability to lift arm. Sufficient time must be spent to identify, tag and repair the GT. A posteriorly displaced GT is often missed from the anterior deltopectoral approach. Suture bites must be taken from the bone-tendon junction (not thru the bone). Insufficient sutures & rough handling of GT are often responsible for “high flying” GT on post-op Xrays.

-

a)

-

C)

Intramedullary nailing:

Older generation nails scarred the rotator cuff and thus went out of favor. The 3rd generation nails have been recently introduced which are inserted through the supraspinatus belly and articular part of the head. These are difficult to insert and useful only to stabilize largely undisplaced fractures.

-

D)Arthroplasty:

-

I)Hemi-arthroplasty (HA) - Every attempt must be made to reconstruct proximal humerus (even in split or dislocated head), particularly in younger patients.6 Good functional results are possible even if AVN ensues in future. In elderly patients, HA (with fracture prosthesis) can be used. However, failure rates are high because of the nonunion of tuberosities.

-

II)Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty (RSA) – Non-union of tuberosities and varus collapse leading to screw cut-outs are common in fragile bones. RSA offers an attractive alternative approach.7 Though attractive, it is a challenging surgery, and the complication rates are high in the hands of low volume surgeons.

-

I)

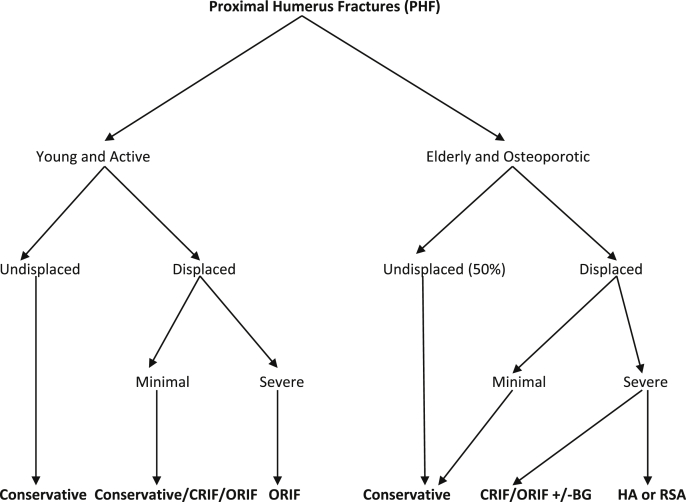

We propose an algorithm (Fig. 1) for the management of PHF, which may provide an easy understanding and treatment guidelines to the practicing Orthopaedic surgeons.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for the management of Proximal Humeral Fractures

Abbreviations: CRIF: Closed Reduction and Internal Fixation; ORIF: Open Reduction and Internal Fixation; BG: Bone Grafting; HA: Hemi-arthroplasty; RSA: Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty.

Contributor Information

Shashank Misra, Email: shashank.misra@outlook.com.

Raju Vaishya, Email: raju.vaishya@gmail.com.

Vivek Trikha, Email: vivektrikha@gmail.com.

Jitendra Maheshwari, Email: dr.maheshwari@kneeandshoulderclinic.com.

References

- 1.Laux C.J., Grubhofer F., Werner C.M.L., Simmen H.P., Osterhoff G. Current concepts in locking plate fixation of proximal humeral fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017;12:137–145. doi: 10.1186/s13018-017-0639-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sabharwal S., Patel N.K., Griffiths D., Athanasiou T., Gupte C.M., Reilly P. Trials based on specific fracture configuration and surgical procedures likely to be more relevant for decision making in the management of fractures of the proximal humerus. Bone J Res. 2016;5(10):470–480. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.510.2000638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabi S., Evaniew N., Sprague S.A., Bhandari M., Slobogean G.P. Operative vs. non-operative management of displaced proximal humeral fractures in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Orthoped. 2015;6(10):838–846. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i10.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Handoll H.H.G., Brorson S. Interventions for treating proximal humeral fractures in adults (Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000434.pub4. Art. No. CD000434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Handoll H., Brealey S., Rangan A. The ProPHER (PROximal Fractures of the Humerus: evaluation by Randomisation) trial-a pragmatic multicentric randomized controlled trial evaluating the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of surgical compared with non-surgical treatment of proximal fracture of the humerus in adults. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(24) doi: 10.3310/hta19240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers L., Dines J.S., Lorich D.G., Dines D.M. Hemiarthroplasty for proximal humeral fractures. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6:57–62. doi: 10.1007/s12178-012-9152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chivot M., Lami D., Bizzozero P., Galland A., Argenson J.N. Three-and Four-part displaced proximal humeral fractures in patients older than 70 years: reverse shoulder arthroplasty or non-surgical treatment? J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2019;28(2):252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]