Abstract

Background

Coxa vara is a hip deformity in which the femoral neck-shaft angle decreases below its normal value. Standard surgical treatment for this condition is corrective valgus osteotomy. Appropriate correction of the Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle is important to prevent recurrence. The purpose of this study is to: 1) evaluate the recurrence of the deformity at the latest follow up; and 2) find the appropriate angle of correction associated with the lowest recurrence.

Methods

34 hips in 31 patients who underwent surgery for treatment of coxa vara from 2005 to 2014 were included. Patient-reported outcomes, Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle, and neck-shaft angle were assessed preoperatively, postoperatively, and at latest follow-up.

Results

The mean age at surgery was 10.99, with a range of 5–30, years. Preoperative neck-shaft angle ranged from 60 to 100 degrees, and Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle ranged from 60 to 90 degrees. At the latest follow up, the neck-shaft angle ranged from 120 to 135 degrees and the Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle ranged from 22 to 35 degrees (p < 0.001). The Harris hip score improved from 47.20 (34–66) to 79.68 (60–100) (p < 0.001). There was no recurrence of deformities at the mean follow up of 37.87 months.

Conclusion

Surgical correction of coxa vara in various pathologies can be done successfully with the Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle corrected to ≤ 35 degrees or the neck shaft angle corrected to > 120 degrees in order to prevent recurrence of the deformity. Majority of the patients were reported improvement of hip function. However, a longer-term follow up is required to determine further outcomes regarding to recurrence of the deformity.

Keywords: Coxa vara, Osteotomy, Intramedullary nail, Osteogenesis imperfecta, Fibrous dysplasia, Skeletal dysplasia

1. Background

Coxa vara is a condition in which the femoral neck-shaft angle decreases below its normal value based on age.1, 2, 3 The deformity can be primarily caused by a congenital defect of the femoral neck cartilage, or from secondary causes related to trauma, infection, skeletal dysplasia, and pathologic bone disorders.1,4

Common presentations in patients with coxa vara include Trendelenburg gait and, in unilateral cases, leg-length discrepancy. When left untreated, patients can develop morbidities, such as stress fractures and hip joint degeneration.1 Because coxa vara occurs infrequently, there have been only a few reports describing its surgical correction. The indications for treatment of coxa vara are: 1) Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle greater than 60 degrees; 2) progression of the deformity; and 3) Trendelenburg movement.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Goals of treatment are: 1) restoration of the hip mechanical axis; 2) restoration of Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle and the neck-shaft angle to prevent the recurrence of deformities; and 3) restored function of the hip abductor.11

The purpose of this study is to: 1) report the outcomes of surgical correction of coxa vara with various pathologies using radiographic measurements and outcome scores; 2) evaluate the recurrence of the deformity at the latest follow up; and 3) find the appropriate angle of correction that may help prevent recurrence.

2. Methods

An IRB-approval was obtained prior to data collection for this study. During the 2005–2014 study periods, there were 31 patients (34 hips) with coxa vara, from various etiologies, who underwent surgical correction. Clinic notes and radiographs of these patients were reviewed. The criteria for exclusion were incomplete patient information, incomplete radiographic data, presenting of osteoarthritis, and a follow up of less than 2 years. There were 18 males (19 hips) and 13 females (15 hips) included in this study. The left side was affected in 13 hips, and the right side in 21 hips. Three patients had bilateral correction. A valgus proximal femoral osteotomy was performed in all patients12,13 (Fig. 3). In addition, some patients underwent a femoral osteotomy due to femoral shaft deformity14 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). The radiographic parameters recorded were Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle and the neck-shaft angle, measured on standard AP hip radiographs. All of these parameters were reviewed and evaluated preoperatively, postoperatively, and at the latest follow up. The Harris hip scores were reviewed pre-operatively, and at the lastest follow up. More than 20% progression of the Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle and the neck shaft angle were considered a recurrence of deformity.

Fig. 3.

Radiographic characteristics of a 18-year-old female patient: (3A) Fibrous dysplasia withcoxa vara; valgus osteotomy using a gamma nail was performed at the right hip. At the 3-year follow-up, the patient could walk independent without aid and had a neck-shaft angle of 130 degees. (3B).

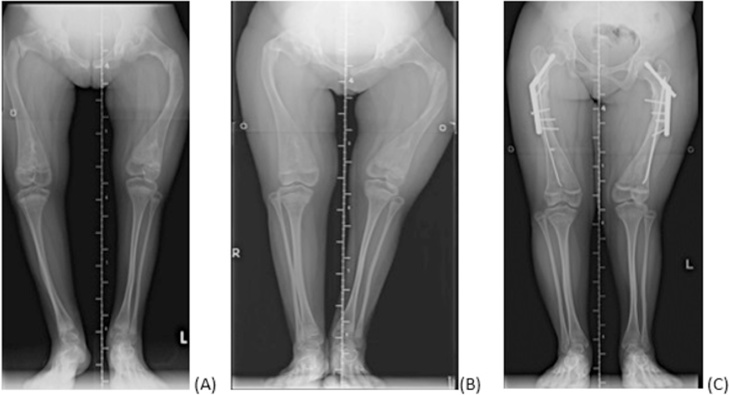

Fig. 1.

Radiographic characteristics of a 12-year-old female patient: (1A) Osteogenesis imperfecta proximal femoral fractures with severe coxa vara; (1B) After healing of the right proximal femur, the neck-shaft angle decreased to 60 degrees, but the left hip had delayed union; (1C) Valgus osteotomy combined with a Sofield-Millar operation using a pediatric dynamic hip screw and titanium elastic nail performed at the left hip, then at the right hip 3 months later. At the 2-year follow-up, the patient could walk independently without aid and had a neck-shaft angle of 130 degrees.

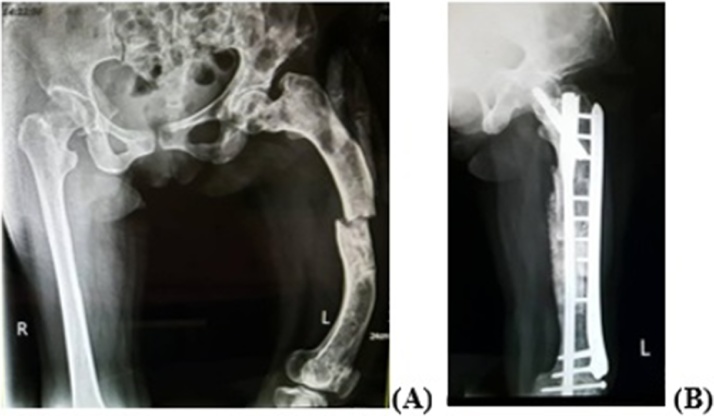

Fig. 2.

Radiographic characteristics of a 30-year-old female: (2A) Monostotic fibrous dysplasia with coxa vara and femoral fracture; (2B) Valgus osteotomy combined with a Sofield-Millar operation using gamma nail with plate and screw augmentation was performed at the left hip. At 3-year follow-up, the patient could walk independently without aid and had a neck-shaft angle of 130 degrees.

3. Results

The mean age at surgery was 10.99 (ranging from 5 to 30) years. The average follow-up period was 37.87 (ranging from 24 to 84) months. The etiologies of the deformity were classified as Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI) in 9 patients, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia or multiple epiphyseal dysplasia in 3 patients, malunion femoral neck fracture in 4 patients, congenital coxa vara in 4 patients, polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, fibrous dysplasia /monostotic fibrous dysplasia in 9 patients, and Histiocytosis X in 2 patients (Table 1). Radiographic analysis of Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle and the neck-shaft angle showed significant improvement at the final follow up compared with the preoperative baseline for all patients (Table 2). The mean neck-shaft angle improved from 86.09 ± 11.31 degrees preoperatively to 129.64 ± 3.95 degrees at the latest follow-up (p < 0.001). The mean Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle improved from 66.76 ± 7.99 degrees preoperatively to 29.26 ± 4.37 degrees at the final follow-up (p < 0.001). By the last follow-up visit, all bone fragments showed signs of radiographic union. In all osteotomies, surgical correction was maintained at the final follow up with a neck-shaft angle of at least 122 degrees in each case. At the final follow-up visit for each patient, no recurrence of coxa vara was reported. The Harris hip score improved from 47.23 ± 7.46 to 79.68 ± 8.22 (p < 0.001). One patient had a delayed union that was treated with bone grafting at 4 months after the first surgery. The osteotomy healed successfully without further incident after the bone grafting. Within the study period, there were no incidences of implant-related complications or infection. Significant improvement in the quality of life following the surgery was reported. Those patients who used wheel chair or axillary crutches before surgery were able to walk independently without a gait aid afterward.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of coxa vara patients.

| Case | Gender | Hip | Diagnosis | Age at surgery (year) | Healing time (months) |

Follow-up (months) | Ambulatory Status Pre-op |

Ambulatory Status post-op |

fixation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | Right | OI | 12 | 3 | 36 | Wheel chair | Independent walk | DHS + titanium elastic nail |

| Left | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | F | Right | OI | 13 | 5 | 26 | Wheel chair | Independent walk | DHS + titanium elastic nail |

| Left | 5 | ||||||||

| 3 | M | Right | Fibrous dysplasia | 9 | 3 | 30 | crutches | Independent walk | DHS |

| 4 | F | Right | Histiocytosis X | 5 | 2 | 40 | crutches | Independent walk | DHS |

| 5 | M | Right | OI | 5 | 3 | 24 | crutches | Independent walk | DHS + titanium elastic nail |

| 6 | M | Right | Fibrous dysplasia | 6 | 2 | 28 | crutches | Independent walk | DHS |

| 7 | M | Left | OI | 11 | 4 | 30 | crutches | Independent walk | DHS |

| 8 | F | Right | OI | 8 | 3 | 40 | Independent walk | Independent walk | ABP |

| 9 | F | Right | Monostotic fibrous dysplasia | 30 | 3 | 36 | Independent walk | Independent walk | Gamma nail |

| 10 | F | Left | polyostotic fibrous dysplasia | 28 | 5 | 30 | Wheel chair | Independent walk | Gamma nail |

| 11 | F | Right | Histiocytosis X | 5 | 2 | 40 | crutches | Independent walk | DHS |

| 12 | M | Right | OI | 10 | 3 | 24 | crutches | Independent walk | DHS + titanium elastic nail |

| 13 | M | Right | Fibrous dysplasia | 7 | 2 | 28 | crutches | Independent walk | DHS |

| 14 | M | Left | OI | 13 | 4 | 30 | crutches | Independent walk | DHS + titanium elastic nail |

| 15 | F | Right | OI | 8 | 3 | 40 | Independent walk | Independent walk | DHS + titanium elastic nail |

| 16 | F | Right | Monostotic fibrous dysplasia | 18 | 3 | 36 | Independent walk | Independent walk | Gamma nail + plate and screws |

| 17 | F | Left | polyostotic fibrous dysplasia | 15 | 5 | 30 | Wheel chair | Independent walk | Gamma nail |

| 18 | M | Right | Fibrous dysplasia | 14 | 2 | 28 | crutches | Independent walk | DHS |

| 19 | M | Right | OI | 13 | 3 | 24 | crutches | Independent walk | DHS + titanium elastic nail |

| 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Mean ± SD |

M M M M F F M M M M M F |

Right Right Left Left Right Left Right Right Left Left Left Right Left |

Fibrous dysplasia SED SED MED MFNF MFNF MFNF MFNF CCV CCV CCV CCV |

6 7 7.4 10.5 12 11.6 10 8 11.5 9 10 7.6 10.99 ± 5.75 |

2 2 2 3 3 2 3 3 3 3 2 3 3 ± 0.94 |

28 40 42 65 44 40 67 36 41 84 50 37 37.87 ± 13.40 |

Crutches Independent walk Independent walk Independent walk Crutches Crutches Crutches Crutches Independent walk Independent walk Independent walk Independent walk |

Independent walk Independentwalk Independent walk Independent walk Independent walk Independent walk Independent walk Independent walk Independent walk Independent walk Independent walk Independent walk |

DHS ABP ABP ABP ABP ABP ABP ABP ABP ABP ABP ABP |

Abbreviations: OI: Osteogenesis imperfecta, SED: Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, MED: Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, MFNF: Malunion femoral neck fracture, CCV: Congenital coxa vara, ABP: Angle Blade plate.

Table 2.

Radiographic data and ambulatory status of Coxa Vara patients.

| Case | NSA (pre-op) | NSA (post-op) | NSA (final follow-up) | HEA (pre-op) | HEA (post-op) | HEA (final follow-up) | HHS (pre-op) |

HHS (final follow-up) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Right 60° Left 90° |

Right 130° Left 130° |

Right 130° Left 130° |

Right 90° Left 70° |

Right 28° Left 30° |

Right 27° Left 28° |

34 | 78 |

| 2 | Right 85° Left 100° |

Right 130° Left 130° |

Right 130° Left 130° |

Right 70° Left 75° |

Right 25° Left 22° |

Right 28° Left 21° |

41 | 60 |

| 3 | 90° | 130° | 130° | 65° | 26° | 28° | 50 | 82 |

| 4 | 100° | 135° | 135° | 60° | 27° | 28° | 40 | 75 |

| 5 | 85° | 130° | 130° | 60° | 25° | 26° | 52 | 78 |

| 6 | 100° | 135° | 135° | 60° | 28° | 30° | 49 | 78 |

| 7 | 80° | 130° | 130° | 70° | 22° | 22° | 66 | 82 |

| 8 | 85° | 130° | 130° | 60° | 25° | 26° | 50 | 68 |

| 9 | 100° | 135° | 135° | 60° | 28° | 30° | 49 | 85 |

| 10 | 100° | 135° | 135° | 60° | 28° | 30° | 45 | 89 |

| 11 | 80° | 130° | 130° | 70° | 22° | 22° | 43 | 81 |

| 12 | 90° | 130° | 130° | 65° | 26° | 28° | 41 | 68 |

| 13 | 100° | 135° | 135° | 60° | 27° | 28° | 43 | 81 |

| 14 | 85° | 130° | 130° | 60° | 25° | 26° | 41 | 75 |

| 15 | 90° | 130° | 130° | 65° | 26° | 28° | 50 | 78 |

| 16 | 100° | 135° | 135° | 60° | 27° | 28° | 40 | 85 |

| 17 | 85° | 130° | 130° | 60° | 25° | 26° | 41 | 89 |

| 18 | 100° | 135° | 135° | 60° | 28° | 30° | 45 | 78 |

| 19 | 80° | 130° | 130° | 70° | 22° | 22° | 43 | 81 |

| 20 | 85° | 130° | 130° | 60° | 25° | 26° | 41 | 75 |

| 21 | Rt.80° | 131° | 130° | 75° | 30° | 31° | 55 | 78 |

| Lt.85° | 135° | 135° | 80° | 30° | 31° | |||

| 22 | 85° | 125° | 130° | 75° | 35° | 35° | 50 | 68 |

| 23 | 65° | 125° | 125° | 73° | 28° | 30° | 60 | 85 |

| 24 | 69° | 123° | 124° | 70° | 30° | 32° | 50 | 90 |

| 25 | 70° | 120° | 123° | 62° | 33° | 35° | 43 | 81 |

| 26 | 85° | 124° | 124° | 61° | 35° | 35° | 41 | 68 |

| 27 | 65° | 125° | 125° | 65° | 35° | 35° | 55 | 90 |

| 28 | 92 | 125 | 127 | 65 | 35 | 37 | 41 | 75 |

| 29 | 93 | 120 | 122 | 68 | 32 | 33 | 60 | 100 |

| 30 | 95 | 123 | 123 | 66 | 35 | 37 | 60 | 80 |

| 31 | 73 | 120 | 125 | 86 | 33 | 35 | 45 | 89 |

| Mean ± SD | 86.09 ± 11.13 | 128.26 ± 6.59 | 129.64 ± 3.95 | 66.76 ± 7.99 | 28.09 ± 3.92 | 29.26 ± 4.37 | 47.23 ± 7.46 | 76.68 ± 8.22 |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

Abbreviations: NSA: neck-shaft angle; HEA: Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle, HHS: Harris hip score.

4. Discussion

Patients with coxa vara are generally presented with difficulties in ambulating, specifically leg-length discrepancy and Trendelenburg gait. Abnormal force transferred through the femoral neck can cause stress fractures and osteoarthritis of the hip.1,4 Surgical correction plays a vital role to prevent the progression of these sequelae in patients with coxa vara. The surgical indications include Trendelenburg gait, progressively decreasing neck-shaft angle, and a Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle of greater than 60 degrees. Pauwels15 described the concept of osteotomy aiming to convert coxa vara to the normal axis. The treatment goal for coxa vara is to restore a normal biomechanical function of the hip joint by correcting Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle and the neck-shaft angle. In pediatric patients, this will re-orientate the physis to a more regular horizontal position, which is less susceptible to shear stress. Several methods have been used for fixation of the femoral osteotomy, including tension band wiring, angle blade plates, dynamic sliding hip screws, and external fixators.2,7,8,16

Recurrence of the deformity is the most important problem following corrective surgery and has been reported at rates varying from 30 to 70%.2,3,8,10,17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Carroll et al9 stated that a high recurrence may be related to the altered hip biomechanics. When the proximal femoral physis is in a vertical position, the mechanical forces across the hip joint change, leading to a progression of coxa vara as well as osteoarthritis. Many authors have agreed that appropriate correction of the Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle is the most crucial factor in prevention of the recurrence.9,18,19 Desai and Johnson19 claimed that no recurrence occurred in a case series of 12 hips with a postoperative Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle of ≤ 35 degrees and a neck-shaft angle of ≥ 130 degrees, irrespective of the patient’s age at surgery. Cordes et al18 studied 14 cases and described excellent clinical results, regardless to the etiology of coxa vara, when the Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle of ≤ 40 degrees was achieved. Carroll et al9 found that when the Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle was corrected to less than 38 degrees, 95% of their studied group had no recurrence of varus deformity. They also found that the recurrence rate was not affected by etiology of deformity, type of implant, type of surgery, and the age at surgery. A study by Burns and Stevens1 concurringly emphasized the importance of the correction of the Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle to less than 38 degrees.

In this studied group, we were able to improve the mean Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle and neck-shaft angle at the last follow up to 29.26 and 129.64 degrees, respectively. The maximum postoperative value of the Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle was 35 degrees, and none of these cases had recurrence. Comparing the postoperative images to the final follow-up images, we found no statically significant difference in neck-shaft angles and Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angles, implying that the correction was maintained throughout the follow-up period of 37.84 months. The postoperative Harris hip scores improved significantly at the final follow up, indicating improved functional activity of the patients after corrective treatment.

Based on our findings, surgical correction of coxa vara in various bone diseases with a Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle correction of ≤ 35 degrees and a neck-shaft angle of > 120 degrees produced good short-term results. However, a longer-term observation is necessary to determine further outcomes with respect the recurrence of the deformity.

5. Conclusion

The surgical treatment of femoral coxa vara to achieve Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle ≤ 35 degrees and neck-shaft angle > 120 degrees can prevent recurrence regardless of the cause of the deformity. The aim of treatment was to modify the femoral neck anatomy to normalize the forces around the hip joint and reduce the incidence of further stress fracture and osteoarthritis.

Funding disclosure

This was an unfunded study.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest declaration

The authors hereby declare no personal or professional conflicts of interest regarding any aspect of this study.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study gratefully acknowledge Suchitphon Chanchoo for assistance with data collection and statistical analysis.

Contributor Information

Thammanoon Srisaarn, Email: srisaarn@pmk.ac.th.

Krits Salang, Email: kwanichanon@gmail.com.

Benjamin Klawson, Email: btklawson@wustl.edu.

Kitiwan Vipulakorn, Email: KITVIP@kku.ac.th.

Ornusa Chalayon, Email: ornusa9@gmail.com.

Perajit Eamsobhana, Email: peerajite@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Burns K.A., Stevens P.M. Coxa vara: another option for fixation. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2001;10(October (4)):304–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weighill F.J. The treatment of developmental coxa vara by abduction subtrochanteric and intertrochanteric femoral osteotomy with special reference to the role of adductor tenotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;(May (116)):116–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chotigavanichaya C., Leeprakobboon D., Eamsobhana P., Kaewpornsawan K. Results of surgical treatment of coxa vara in children: valgus osteotomy with angle blade plate fixation. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97(September (Suppl. 9)):S78–S82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Key J.A. The classic: epiphyseal coxa vara or displacement of the capital epiphysis of the femur in adolescence. 1926. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(July (7)):2087–2117. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2913-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elzohairy M.M., Khairy H.M. Fixation of intertrochanteric valgus osteotomy with T Plate in treatment of developmental coxa vara. Clin Orthop Surg. 2016;8(September (3)):310–315. doi: 10.4055/cios.2016.8.3.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aarabi M., Rauch F., Hamdy R.C. High prevalence of coxa vara in patients with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(January– February (1)):24–28. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000189007.55174.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amstutz H.C., Frieberger R.H. Coxa vara in children. Clin Orthop. 1962;22:73–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amstutz H.D., Wilson P.D. Dysgenesis of the proximal femur (coxa vara) and its surgical management. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1962;44-A(January):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll K., Coleman S., Stevens P.M. Coxa vara: surgical outcomes of valgus osteotomies. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17(March–April (2)):220–224. doi: 10.1097/00004694-199703000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinstein J., Kuo K., Millar E. Congenital coxa vara. A retrospective review. J Pediatr Orthop. 1984;4(January (1)):70–77. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198401000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serafin J., Szulc W. Coxa vara infantum, hip growth disturbances, etiopathogenesis, and long term results of treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;(November (272)):103–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eamsobhana P., Keawpornsawan K. Nonunion paediatric femoral neck fracture treatment without open reduction. Hip Int. 2016;26(November (6)):608–611. doi: 10.5301/hipint.5000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borden J., Spencer G.E., Jr., Herndon C.H. Treatment of coxa vara in children by means of a modified osteotomy. Bone Jt Surg Am. 1966;48(September (6)):1106–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman B.H., Bray E.W., Meyer L.C. Multiple osteotomies with Zickel nail fixation for polyostotic fibrous dysplasia involving the proximal part of the femur. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1987;69(June (5)):691–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pauwels F. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: 1976. Biomechanics of the normal and diseased hip. Theoretical foundation, technique and results of treatment; pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobbs M., Morcuende J. Coxa vara. In: Morrissy R.T., Weinstein S.L., editors. Lovell & winter’s pediatric orthopaedics. Lippincott-Raven Publishers; Philadelphia, PA: 2006. pp. 1126–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Widmann R.F., Hresko M.T., Kasser J.R. Wagner multiple K-wire osteosynthesis to correct coxa vara in the young child: experience with a versatile’ tailor-made’ high angle blade plate equivalent. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2001;10(January (1)):43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cordes S., Dickens D.R., Cole W.G. Correction of coxa vara in childhood. The use of Pauwels’ Y-shaped osteotomy. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1991;73(January (1)):3–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B1.1991770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desai S.S., Johnson L.O. Long term results of valgus osteotomy for congenital coxa vara. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(September (294)):204–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livesley P.J., McAllister J.C., Catterrall A. The treatment of progressive coxa vara in children with bone softening disorders. Int Orthop. 1994;18(October (5)):310–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00180233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fassier F., Sardar Z., Aarabi M., Odent T., Haque T. Results and complications of a surgical technique for correction of coxa vara in children with osteopenic bones. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28(December (8)):799–805. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31818e19b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]