Abstract

Introduction

This paper describes a novel technique developed by the senior author to address acute acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) dislocations and certain distal clavicle fractures.

Methods

The procedure employs a four strand, single tunnel, double endobutton repair performed entirely percutaneously, without any arthroscopic guidance or deep surgical dissection.

Results

We present the preliminary results from our series of 6 consecutive patients performed over a period of 18 months. The mean length of surgery was 36min (range 32–40) and the mean correction of coracoclavicular (CC) distance achieved was 12.6 mm (range 10.3–14.1). There was no restriction of movement in any of the patients post-operatively and their average QuickDASH scores at final follow-up was 4.2 (range 0–6.8).

Conclusion

Results in the present series were at least comparable to those for other techniques, validating percutaneous treatment as a solution for acute ACJ dislocations.

Keywords: Percutaneous, Acromioclavicular joint, Endobutton, Clavicle, Fracture, Tight rope, Fixation

1. Introduction

The management of acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) injuries remains highly controversial. The injury classification, the appropriate management of acute Rockwood Type III injuries, the surgical constructs used and the need for the use of biological augments are all matters for debate. Numerous static and dynamic techniques have been described for the management of acute ACJ dislocations, and these include ACJ pinning, coracoclavicular (CC) screw insertion (either percutaneously or via open surgery), CC loop cerclage, CC ligament repair, hook plates, coracoid transfer, distal clavicle excision and ligament or muscle transfer.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Endobutton™ reconstructions, utilising single, double or triple button configurations have also been described and these have been inserted either via open, mini-open, or arthroscopic techniques.1,7, 8, 9 Each of these procedures have had complications described and no standard technique has been established to date.4,6,10, 11, 12 The aim of this study was to describe and evaluate a novel percutaneous Endobutton™ technique developed by the senior author to address acute ACJ dislocations and certain Neer type II distal clavicle fractures.

2. Methods

The senior surgeon employs this technique for acute ACJ injuries less than 2 weeks old, which are clinically mobile and reducible with manual pressure. It is a single tunnel, double Endobutton™ (Smith & Nephew) repair that utilises 4 strands of Fibertape® (Arthrex). This study describes the surgical technique and the results from 6 consecutive patients who had undergone the procedure.

2.1. Surgical technique

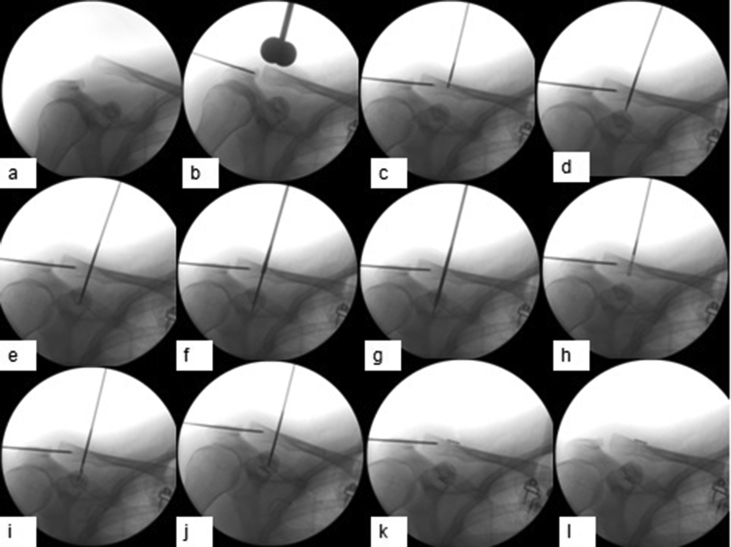

The patient is under general anaesthesia and given antibiotic prophylaxis. He is sat upright in the beachchair position. The C— arm of the x-ray image intensifier (II) approaches from the opposite side and is nearly horizontal, allowing it to take true anteroposterior (AP views) of the AC joint (Fig. 1a and b). The AC joint is manually reduced and held in place with a temporary 2 mm K-wire. Closed reduction is achieved via downward pressure on the distal clavicle and upward pressure on the arm. The K-wire is directed from the anterolateral corner of the acromion, across the AC joint and towards the posterior cortex of the distal clavicle. This is to allow for enough space in the middle of the bone for the clavicle tunnel preparation. The entry point is identified under II guidance and a small 1 cm stab incision is made. The entry point is positioned such that it allows for a straight passage of the guidewire from the clavicle to the centre of the coracoid. This is usually about 3 cm from the distal clavicle edge, between the native insertions of the conoid and trapezoid ligaments (Fig. 2c). After making the skin incision, the guidewire is used to feel for the anterior and posterior cortices of the clavicle and hence determine the entry point, which should be in the middle of the clavicle. The guidewire is then aimed 15–20° anteriorly and towards the middle of the coracoid (under II guidance) and then slowly advanced. Care should be taken to slowly advance the guidewire through each of the 4 cortices it will pass in the superior to inferior direction, checking under II guidance and by feel at each cortex. The guidewire should not be advanced deeper beyond the inferior cortex of the coracoid, to prevent injury to the neurovascular structures below (Fig. 2d and e).

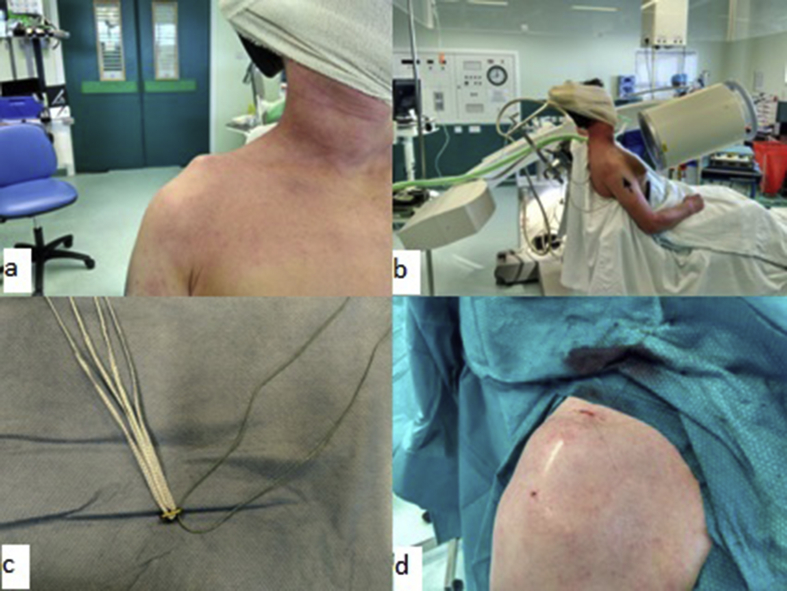

Fig. 1.

a–d. Intra-operative pictures showing the pre-operative deformity (a), set-up of the image intensifier in theatre (b), Endobutton/Fibretape construct with ‘rescue’ suture limb before deploying (c) and the post-operative surgical scar (d).

Fig. 2.

a–l. Intra-operative imaging showing the sequence of steps: Closed reduction of ACJ, held in place with a temporary K –wire (a,b), Careful passage of the guide wire across the 4 cortices, followed by over drilling (c–g), passing of the inferior endobutton through the 2 bone tunnels on the end of the Beath pin (h–j), final strong double endobutton construct shows no widening of the CC distance after removal of the temporary transfixing k-wire (k–l).

Once satisfactory position of the guidewire has been determined, this is over-drilled with the 4.5 mm cannulated drill. This is done in a similar fashion to the guidewire, checking under II guidance and by feel at each cortex. The drill is left to run in the space between the clavicle and coracoid, to create a ‘soft tissue tunnel’ for the Endobutton™/Fibertape® construct to pass through later. It must also be monitored under II that the drilling does not cause the guidewire to advance inferiorly (Fig. 2f and g).

Once the bone and soft tissue tunnels have been created, we prepare the Endobutton™/Fibertape® construct. We remove the continuous loop suture of an Endobutton™ and thread two 2 mm Fibertape® sutures through the central holes. We also remove one of the ‘flipping’ sutures from the Endobutton, leaving just one behind, which would be used as an emergency ‘retrieval’ suture, should the need arise (Fig. 1c). The resultant Endobutton™/Fibretape® construct is then advanced lengthwise through the bone tunnels, using the blunt end of the guidewire to push it through, checking its progress and that it remains vertical along its path under II guidance (Fig. 2h and i). When the endobutton has passed beyond the coracoid tunnel, the guidewire is left in the coracoid tunnel and the slack on the Fibertape® is tightened, till the Endobutton™ flips horizontally and is snug under the coracoid (Fig. 2j). The ‘retrieval suture’ can be removed at this stage. A second Endobutton™ is then threaded through the sutures superiorly and the 2 lengths of Fibertape® are tightened over this sequentially, while manual pressure is applied to keep the AC joint well reduced. It should be ensured that there is no slack between the Endobuttons™ and the bone on either end. The temporary 2 mm K-wire is removed at this stage, and it can be appreciated that the CC distance is maintained (Fig. 2k-l). The wound is washed and closed with subcuticular sutures and the arm is protected in a sling for 4 weeks. The patient can do gentle pendular active range-of-movement (ROM) in this period, commences overhead active ROM at 4 weeks and progresses to gradual passive ROM and strengthening exercises after 6 weeks post-operatively. They are allowed full return to activities and sports after 12 weeks. The procedure is performed as a day surgery case and the patient goes home the same day.

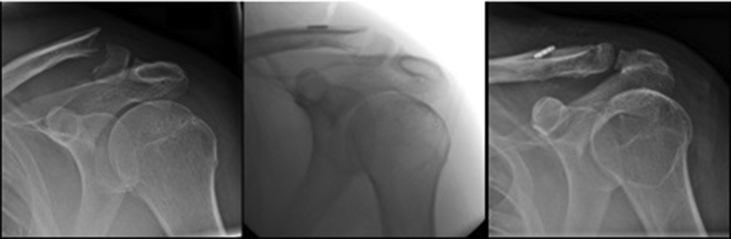

2.2. Neer Type II distal clavicle fractures

The author has also adopted this percutaneous method to successfully treat an amenable Neer type 2 fracture of the distal clavicle, where the medial fragment was significantly displaced as a result of the injury involving the CC ligaments. Robinson et al. have had good outcomes utilising a similar construct in such injuries done via an open approach.13

Data entry was performed using a spreadsheet application (Excel 2010; Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). Descriptive statistics (mean, range) were presented for all variables. Categorical variables were presented as proportions, while continuous variables were presented as a mean. The paired sample T test was used for pre- and post-operative CC distance. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05, and data analysis was performed using SPSS (Version 16; SPSS, Inc, an IBM Company, Chicago, IL).

3. Results

Our retrospective series has 6 consecutive patients, whose surgeries were performed over a period of 18 months. Their mean age was 42.5 years (range 26–48). They were all male and 4 of them had injured their shoulder on the dominant side. The mechanisms of injury were all high impact, including road traffic accidents, mountain bike injuries and rugby injuries. Four of them were purely ACJ dislocations (3 Rockwood grade III injuries, 1 Rockwood grade IV injury), one of them had a Neer type II distal clavicle fracture (Fig. 3) and one was a grade III ACJ dislocation in someone who had a midshaft clavicle fixation performed previously with the plate still insitu (Fig. 4). The mean time between injury and date of surgery was 10.6 days (range 3–13). The mean duration of surgery was 36min (range 32–40). All patients were operated on by the senior author. Their mean follow up was 17.5 months (range 12–30).

Fig. 3.

Successful treatment of a Neer Type II distal clavicle fracture using this technique.

Fig. 4.

Percutaneous technique applied to a Type III ACJ injury with adjacent clavicle implants in-situ.

Their pre-operatively widened CC distances measured a mean of 24.9 mm (range 21.5–28.5). Their immediate post-operative CC distances were significantly reduced with a mean of 12.3 mm (range 10.6–15.8) (p = 0.00). This resulted in a mean CC distance correction of 12.6 mm (range 10.3–14.1). There was no restriction of movement (ROM) in any of the patients post-operatively and their mean QuickDASH scores at final follow-up was 4.2 (range 0–6.8). All patients were able to return to their pre-injury level of activity, work or sport.

There was one complication in this series; a patient who had a significant history of atopic dermatitis developed an infected granuloma at the wound site approximately 3 months post-operatively. When this did not respond to oral antibiotics and outpatient silver nitrate cautery, he underwent an elective wound debridement and removal of the endobutton construct. After this second surgery, his wound went on to heal satisfactorily without incident and there was no widening of the CC distance at 17 months despite removal of the endobutton implants after only 3 months.

4. Discussion

The literature does not show any clear advantage of surgery or conservative management over each other in the treatment of Type III ACJ injuries. In a series of patients with Type III ACJ injuries treated by both methods, Press et al. reported that the surgery group had better pain free status, subjective impression of pain, ROM, less functional limitations, better cosmesis, faster return to full work duties and long term reported satisfaction.14 Another comparative study of Type III ACJ injuries managed either surgically or conservatively by Gstettner et al. also showed better functional and radiographic outcomes in the surgical group.15 However, there are also numerous studies which show similar outcomes irrespective of the treatment modality, which leads most surgeons to adopt an initial trial of conservative treatment for type III ACJ injuries, unless the injury is in a manual labourer, elite athlete or similarly active individual.6,16 Other relative indications for surgery in Type III injuries are associated intra-articular injuries, significant deformity or a highly mobile clavicle in the acute setting, secondary scapula dyskinesis and persistent pain or instability after failed conservative management. The patients in our series comprised of physically active labourers, sportsmen and a soldier, hence they underwent surgery in the acute setting.

What are the benefits of this procedure? This fixation offers excellent results, in terms of reduction of the AC joint and the superior biomechanical strength of the construct compared to the native CC ligaments.17 Studies have shown that similar constructs performed open/arthroscopically are strong, without being rigid. The percutaneous approach means superior cosmesis, and potentially less post-operative pain and faster recovery as a result of less soft tissue dissection. Because of the minimally invasive nature of the approach, there can be better biological healing of the distal clavicle fractures/CC ligaments as the fracture site/soft tissue envelope containing the inflammatory healing tissue factors are not disrupted at the site of injury as a result of open dissection. Unlike the hookplate, using this endobutton construct does not require a second procedure for implant removal. This procedure can also be performed relatively quickly, which allows for efficient theatre utilisation and potentially confers a lower infection risk. When these initial cases were performed, this technique had not been described in the literature previously. However, a series utilising a similar technique was published by Acar et al. prior to the submission of this manuscript.18

A potential criticism of this technique would be that we are unable to address any accompanying glenohumeral (GH) pathology with this method. Tischer et al. noted that 18.2% (14/77) in their series of patients with ACJ injuries had associated intra-articular pathology, such as SLAP lesions, rotator cuff tears or associated fractures.19 However, none of their patients with Type III injuries were found to have any associated injuries. Pauly et al. showed in their series of high grade ACJ injuries a rate of concomitant GH pathologies of 30.4% (38/125 patients).20 However, of these 38 associated lesions, only 9 were due to the acute trauma and the rest were either degenerative or of unknown aetiologies. A recent study by Jensen et al. observed concomitant GH pathologies in 53% of their surgically treated ACJ injuries.21 They also noted that increasing patient age, chronic injuries and Type V injuries were significantly associated with concomitant GH lesions. Perhaps a screening MRI can be performed in suspicious high grade ACJ injuries to exclude such concomitant GH pathology before employing this percutaneous technique.

Another downside is that this method does not allow for repair of the ruptured delto-trapezial fascia or reconstruction of the injured ACJ ligaments, which some believe is crucial for a good clinical outcome.22, 23, 24, 25 However, it should be noted that the popular all-arthroscopic and mini-open methods of CC-ligament reconstructions do not allow for these either and their long term clinical results are still good.1,7,26 In this study, we only aim to replicate that double button construct, via a different percutaneous technique. A recent biomechanical study looking at the horizontal stabilizing effect of the delto-trapezial fascia (DTF) concluded that a combined lesion of the AC ligaments and DTF resulted in significantly more anterior rotation and lateral translation of the distal clavicle-however, these differences were quantitatively small and of questionable clinical relevance.27

Possible complications might include persistent instability despite repair, loss of reduction over time, fractures of the clavicle or coracoid, endobutton slippage and neurovascular injury, though in our series we did not encounter any of these. Another potential problem would be difficulty in deploying the endobutton through the coracoid, necessitating conversion to open surgery. We did not encounter this problem in our series, but it has been reported by Acar et al. in their series utilising a similar percutaneous technique.18 It is for this reason that we advise on leaving a ‘retrieval’ flipping suture in place, till the endobutton is satisfactorily deployed, to act as a bail-out option. This procedure would also entail significantly more radiation exposure than either open or arthroscopic surgery would.

The limitations of this study are its small patient numbers, relatively short follow-up period and the absence of an open and/or arthroscopic fixation group for comparison. Perhaps future studies can look into the longer term outcomes, as well as comparing outcomes between open, percutaneous and arthroscopic endobutton fixation techniques.

5. Conclusion

Percutaneous fixation of ACJ injuries and lateral clavicle fractures is a safe, simple and effective treatment option. It provides satisfactory functional and radiographic outcomes with an excellent cosmetic result.

5.1. Technical pearls and pitfalls

-

1.

The procedure should only be attempted in acute injuries less than 2 weeks old which are clinically reducible.

-

2.

The temporary trans-fixing K-wire should pass across the AC joint from the anterolateral corner of the acromion, towards the posterior cortex of the distal clavicle to allow space for the clavicle bone tunnel. This should be in the middle of the bone, angled approximately 20° anteriorly towards the base of the coracoid.

-

3.

Always check the smooth passage of the guidewire and drill across each cortex using II guidance and feeling resistance. Do not let either plunge deep below the coracoid.

-

4.

The “soft tissue tunnel” should also be ‘created’ with the drill, failing which one may encounter difficulty passing the Endobutton™/Fibretape® construct across the space between the clavicle and the coracoid.

-

5.

Remember to leave one of the ‘flipping sutures’ behind to act as a retrieval suture, should the unfortunate need arise during the insertion!

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2018.10.013.

Contributor Information

Ruben Manohara, Email: ruben_manohara@nuhs.edu.sg.

Jeffrey Todd Reid, Email: Jeffrey.Reid@nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Beris A., Lykissas M., Kostas-Agnantis I., Vekris M., Mitsionis G., Korompilias A. Management of acute acromioclavicular joint dislocation with a double-button fixation system. Injury. 2013;44:288–292. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatia D.N. Orthogonal biplanar fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous fixation of a coracoid base fracture associated with acromioclavicular joint dislocation. Tech Hand Surg. 2012;16:56–59. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0b013e31823e2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohamed T.E.S., Hatem E.A. Suture repair using loop technique in cases of acute complete acromioclavicular joint dislocation. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s10195-011-0130-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook J.B., Shaha J.S., Rowles D.J., Bottoni C.R., Shaha S.H., Tokish J.M. Early failures with single clavicular transosseous coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:1746–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladermann A., Grosclaude M., Lubbeke A. Acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular cerclage reconstruction for acute acromioclavicular joint dislocations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein D., Day M., Rokito A. Current concepts in the surgical management of acromioclavicular joint injuries. Bull Hosp Joint Dis. 2012;70(1):11–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Defoort S., Verborgt O. Functional and radiological outcome after arthroscopic and open acromioclavicular stabilization using a double-button fixation system. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76:585–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim Y.W. Triple endobutton technique in acromioclavicular joint reduction and reconstruction. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Struhl S., Wolfson T.S. Continuous double loop endobutton reconstruction for acromioclavicular joint dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(10):2437–2444. doi: 10.1177/0363546515596409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milewski M.D., Tompkins M., Giugale J.M., Carson E.W., Miller M.D., Diduch D.R. Complications related to anatomic reconstruction of the coracoclavicular ligaments. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1628–1634. doi: 10.1177/0363546512445273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martetschlager F., Horan M.P., Warth R.J., Millet P.J. Complications after anatomic fixation and reconstruction of the coracoclavicular ligaments. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(12):2896–2903. doi: 10.1177/0363546513502459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clavert P., Meyer A., Boyer P., Gastaud O., Barth J., Duparc F. Complication rates and types of failure after arthroscopic acute acromioclavicular dislocation fixation. Prospective multicenter study of 116 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(8 Suppl):S313–S316. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson C.M., Akhtar M.A., Jenkins P.J., Sharpe T., Ray A., Olabi B. Open reduction and endobutton fixation of displaced fractures of the lateral end of the clavicle in younger patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92B:811–816. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B6.23558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Press J., Zuckerman J.D., Gallagher M., Cuomo F. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular separations. Operative versus non operative management. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1997;56:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gstettner C., Tauber M., Hitzl W., Resch H. Rockwood type III acromioclavicular dislocation: surgical versus conservative treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips A.M., Smart C., Groom A.F. Acromioclavicular dislocation. Conservative or Surgical therapy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;353:10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beitzel K., Obopilwe E., Chowaniec D.M. Biomechanical comparison of arthroscopic repairs for acromioclavicular joint instability, suture button systems without biological augmentation. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2218–2225. doi: 10.1177/0363546511416784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acar M.A., Gulec A., Erkocak O.F., Yilmaz G., Durgut F., Elmadag M. Percutanous double-button fixation method for treatment of acute type III acromioclavicular joint dislocation. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turcica. 2015;49(3):241–248. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2015.14.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tischer T., Salzmann G.M., El-Azab H., Vogt S., Imhoff A.B. Incidence of associated injuries with acute acromioclavicular joint dislocations types III through V. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(1):136–139. doi: 10.1177/0363546508322891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pauly S., Kraus N., Greiner S., Scheibel M. Prevalence and pattern of glenohumeral injuries among acute high-grade acromioclavicular joint instabilities. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:760–766. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen G., Millett P.J., Tahal D.S., Al Ibadi M., Lill H., Katthagen J.C. Concomitant glenohumeral pathologies associated with acute and chronic grade III and grade V acromioclavicular joint injuries. Int Orthop. 2017;41(8):1633–1640. doi: 10.1007/s00264-017-3469-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beitzel K., Obopilwe E., Apostolakos J. Rotational and translational stability of different methods for direct acromioclavicular ligament repair in anatomic acromioclavicular joint reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2141–2148. doi: 10.1177/0363546514538947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez- Lomas G., Javidan P., Lin T., Adamson G.J., Limpisvasti O., Lee T.Q. Intramedullary acromioclavicular ligament reconstruction strengthens isolated coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction in acromioclavicular dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(10):2113–2122. doi: 10.1177/0363546510371442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abrams G.D., McGarry M.H., Jain N.S. Biomechanical evaluation of a coracoclavicular and acromioclavicular ligament reconstruction technique utilizing a single continuous intramedullary free tendon graft. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:979–985. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barth J., Duparc F., Andrieu K. Is coracoclavicular stabilisation alone sufficient for the endoscopic treatment of severe acromioclavicular joint dislocation (Rockwood types III, IV, and V)? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(8 Suppl):S297–S303. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeBerardino T.M., Pensak M.J., Ferreira J., Mazzocca A.D. Arthroscopic stabilisation of acromioclavicular joint dislocation using the AC graftrope system. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pastor M.F., Averbeck A.K., Welke B., Smith T., Claassen L., Wellmann M. The biomechanical influence of the deltotrapezoid fascia on horizontal and vertical acromioclavicular joint stability. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136(4):513–519. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.