Abstract

Background

Statin medications have immunomodulatory effects. Several recent studies suggest that statins may reduce influenza vaccine response and reduce influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE).

Methods

We compared influenza VE in statin users and nonusers aged ≥45 years enrolled in the US Vaccine Effectiveness Network study over 6 influenza seasons (2011–2012 through 2016–2017). All enrollees presented to outpatients clinics with acute respiratory illness and were tested for influenza. Information on vaccination status, medical history, and statin use at the time of vaccination were collected by medical and pharmacy records. Using a test-negative design, we estimated VE as (1 – OR) × 100, in which OR is the odds ratio for testing positive for influenza virus among vaccinated vs unvaccinated participants.

Results

Among 11692 eligible participants, 3359 (30%) were statin users and 2806 (24%) tested positive for influenza virus infection; 78% of statin users and 60% of nonusers had received influenza vaccine. After adjusting for potential confounders, influenza VE was 36% (95% confidence interval [CI], 22%–47%) among statin users and 39% (95% CI, 32%–45%) among nonusers. We observed no significant modification of VE by statin use. VE against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H3N2), and B viruses were similar among statin users and nonusers.

Conclusions

In this large observational study, influenza VE against laboratory-confirmed influenza illness was not affected by current statin use among persons aged ≥45 years. Statin use did not modify the effect of vaccination on influenza when analyzed by type and subtype.

Keywords: influenza vaccine, vaccine effectiveness, statins

In a study of 11692 outpatients aged ≥45 years with acute respiratory illness, statin use had no significant effect on influenza vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza. Statin use did not modify the effect of vaccination on influenza when analyzed by type/subtype.

The burden of hospitalizations and deaths associated with seasonal influenza falls largely on older adults. During 3 recent influenza seasons, an estimated 115000–630000 hospitalizations and 5000–27000 deaths associated with influenza occurred annually in the United States, with up to 71% of hospitalizations and 85% of these deaths occurring in adults aged ≥65 years [1]. In addition, multiple studies have demonstrated that influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) in older adults can be lower compared with that in younger age groups [2, 3]. Understanding factors that contribute to VE is critical to improving protection in this vulnerable population.

Statins (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors) are frequently prescribed to older adults to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease; 1 in 4 US adults aged >40 years was prescribed a statin in 2012 [4]. Several recent studies suggest that statins may reduce the influenza vaccine response and reduce influenza VE [5–7]. Statins, although best known for their cardiovascular benefits, have wide-ranging anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects, and an effect on influenza VE is biologically plausible [8–12]. In a post hoc analysis of data from a randomized trial, Black et al found an association between statin use and reduced antibody titers in response to influenza vaccination [7]. Another study found that statin use was associated with decreased VE against influenza A(H3N2) virus infection but not against other virus types or subtypes [5]. Two additional studies have recently examined this issue. One study that used health records data from a large healthcare organization found an association between statin prescriptions and lower estimates of influenza VE against medically attended acute respiratory infection (MAARI) [6], while a study of Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥65 years concluded that statin use around the time of vaccination does not substantially affect the risk of influenza-related medical encounters (adjusted relative risk, 1.09 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.025–1.15]) [13].

To examine whether statin use during the vaccination period modified influenza VE against laboratory-confirmed influenza among adults, we analyzed data from patients aged ≥45 years with MAARI enrolled in the US Influenza VE study during 6 influenza seasons from 2011–2012 through 2016–2017.

METHODS

We used data collected by the US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (US Flu VE Network) during 6 influenza seasons (2011–2012 through 2016–2017), as described elsewhere [14]. In brief, the network included 50–60 clinics each year that were affiliated with 5 geographically diverse sites that included academic medical centers and healthcare organizations. During periods of influenza circulation at study clinic sites, patients with a MAARI, defined by a new cough of ≤7 days’ duration, were eligible for enrollment. We restricted the analysis to participants aged ≥45 years. Respiratory swab specimens were obtained and tested for influenza with real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for research purposes only [15]. Subjects with a positive test were designated as case patients, and subjects testing negative as non–case patients. In each season, patients could be enrolled once in a 14-day period; only the first enrollment each season was included in this analysis. Eligible patients provided informed consent. Study procedures, forms, and consent documents were approved by site institutional review boards.

Patient characteristics and symptom onset date were ascertained by interview. We obtained patients’ history of underlying medical conditions by examining the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision and Tenth Revision codes assigned to medical encounters during the year before enrollment. Influenza vaccination history for the current influenza season was defined with the use of electronic immunization records and data reported by the participants, as described previously [14]. Vaccination in prior season was determined by electronic immunization records.

Statin prescribing (4 sites) and dispensing data (1 site) were collected from pharmacy and electronic medical records for 1 September in the year prior to the enrollment season through the date of enrollment. The statin prescription start and end dates were calculated based on the prescribing (or dispensing) dates, taking into account the number of pills prescribed, the prescribed daily dose, and the frequency and number of refills associated with each prescription. Patients were classified as statin users if the prescribing or dispensing data indicated that they had received a statin prescription before 1 September of the enrollment season, or, if they received a vaccination and it was before or within 30 days of 1 September, they were on a statin >30 days prior to vaccination. Statin users also could not have a statin prescription end date in the 30 days after vaccination. Patients with no record of statin prescription in the year prior to study enrollment were classified as statin nonusers. Patients were excluded if they had a record of a statin prescription but started statins within 30 days of vaccination or after 1 September of the season of interest, or if they stopped statins within 30 days of vaccination, or, for those patients who were not vaccinated, within 30 days of the median vaccination date for that season. Because other studies have found an association between type of statin and effect on vaccination [5], statins were classified as synthetic (atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and fluvastatin) and nonsynthetic (simvastatin, pravastatin, and lovastatin). If 2 types of statins were listed, the statin with the earliest prescription date was used.

Patients were excluded if they were vaccinated <14 days before illness onset, had inconclusive RT-PCR results, were tested >7 days after symptom onset, or had incomplete medical records.

Vaccine Effectiveness

Influenza VE was estimated using a test-negative design, using the formula (1 – OR) × 100, where OR is the odds ratio for influenza among vaccinated persons as compared with unvaccinated persons. VE estimates the ratio of influenza risk between vaccinated and unvaccinated participants [16]. We used logistic regression models to estimate the adjusted ORs and their 95% CIs. For all influenza virus subtypes, the model included, a priori, age group, sex, study site, season, month of illness onset, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic pulmonary disease. Other variables were included in the model if they improved model fit based on standard model fitting procedures (Akaike information criterion [AIC]); based on the AIC, the final model also included self-rated health and smoking status.

We examined whether inclusion of statin use in the model confounded VE estimates. We also used the same covariates in logistic regression models that estimated VE for the 4 combinations of statin exposure and vaccination (vaccinated nonusers, unvaccinated nonusers, unvaccinated statin users, and vaccinated statin users); results were presented stratified by statin use, with the reference groups being unvaccinated statin users and unvaccinated nonusers. We tested for effect modification of VE by statin use by including an interaction term between vaccination and statin use. Because of site-specific variation in both statin use and influenza activity, we also presented VE data by site.

Several studies have found an association with statin use and influenza virus infection that suggests a protective effect of statin use independent of vaccination status [5, 17, 18]; we examined the independent effect of statin use on risk for influenza. In addition, because prior vaccination has been shown to modify the effectiveness of the current season vaccine [19, 20], and statin use and seasonal influenza vaccination are correlated, the prior season’s vaccination status was assessed as a confounder in a separate analysis. This analysis excluded the 2011–2012 season, for which some data needed to verify prior vaccination status were missing.

We estimated VE for any influenza-associated illness overall and by season and by prespecified age groups. VE for specific influenza types and subtypes—influenza A(H1N1)pmd09, influenza A(H3N2), and influenza B viruses—were estimated using separate models. For the subtype-specific and lineage-specific estimates, case patients infected with other influenza virus subtypes or lineages were excluded. We limited VE estimates by virus type/subtype to those seasons in which there were >30 influenza cases of that virus type/subtype identified: 2013–2014 and 2015–2016 for influenza A(H1N1)pdm09; 2011–2012, 2012–2013, 2014–2015, and 2016–2017 for influenza A(H3N2); and all seasons except 2013–2014 for influenza B. We also analyzed data on influenza A(H3N2) excluding the 2014–2015 season, when antigenic mismatch between the A(H3N2) vaccine component and circulating A(H3N2) viruses resulted in low VE [21].

For all estimates, P values <.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) was used for all analyses. In a power simulation, we estimated that a sample size of 10350 subjects would be adequate to detect a reduction in absolute VE of 17.5% in statin users compared with nonsusers as a result of the interaction between statins and influenza vaccination (details are shown in the Supplementary Materials).

RESULTS

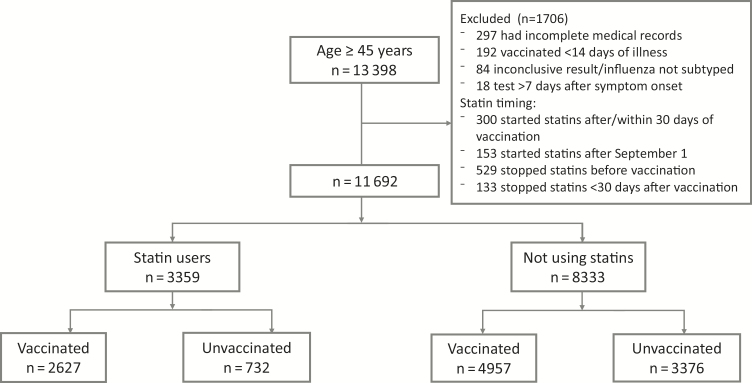

From 1 January 2011 through 14 April 2017, we enrolled 13398 patients aged ≥45 years with MAARI over 6 influenza seasons (Figure 1). We excluded 1706 participants, including 192 participants who were vaccinated <14 days prior to illness onset; 84 who had inconclusive RT-PCR results, were coinfected with multiple influenza types or subtypes, or lacked influenza subtype information; 297 who had incomplete medical records; and 18 who had symptom onset >7 days before enrollment. In addition, we excluded 1115 persons with evidence of a statin prescription in the year prior to the enrollment season, but they had started statins after 1 September or <30 days prior to vaccination (n = 453) or had stopped statins before vaccination or <30 days after vaccination or, for the unvaccinated, <30 days after the median vaccination date for that season (n = 662).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study enrollment.

Among the remaining 11692 participants, 3359 (30%) were statin users and 7584 (65%) were vaccinated (Table 1). Among statin users, 2627 of 3359 (78%) were vaccinated, as were 4957 of 8333 (60%) of nonusers. Statin users were older than nonusers, more likely to be female, and had a higher prevalence of underlying health conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, and morbid obesity. They were also less likely to be a smoker and more likely to have received influenza vaccination, both in the current and in the prior season. Simvastatin was the most frequently prescribed statin (n = 1540), comprising 52% of statin prescriptions, followed by atorvastatin (29%), pravastatin (11%), lovastatin (5.1%), rosuvastatin (0.7%), and fluvastatin (0.1%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Subjects: Patients Aged ≥45 Years Presenting With an Acute Respiratory Infection to Ambulatory Care Settings Affiliated With the US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network, 2011–2012 Through 2016–2017 Influenza Seasons

| Characteristic | Statin Users | Statin Nonusers | All (N = 11692) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unvaccinated (n = 732) |

Vaccinated (n = 2627) |

Unvaccinated (n = 3376) |

Vaccinated (n = 4957) |

||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 354 (48) | 1208 (46) | 1328 (39) | 1586 (32) | 4476 (38) |

| Female | 378 (52) | 1419 (54) | 2048 (61) | 3371 (68) | 7216 (62) |

| Age | |||||

| 45–54 | 184 (25) | 314 (12) | 1690 (50) | 1661 (34) | 3849 (33) |

| 55–64 | 289 (39) | 750 (29) | 1185 (35) | 1650 (33) | 3874 (33) |

| 65–74 | 181 (25)) | 927 (35) | 371 (11) | 1063 (21) | 2542 (22) |

| ≥75 | 78 (11) | 636 (24) | 130 (4) | 583 (12) | 1427 (12) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 604 (83) | 2261 (86) | 2765 (82) | 4232 (85) | 9862 (84) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 48 (7) | 93 (4) | 239 (7) | 194 (4) | 574 (5) |

| Other race, non-Hispanic | 42 (6) | 177 (7) | 219 (42) | 314 (6) | 752 (6) |

| Hispanic (any race) | 36 (5) | 92 (4) | 140 (4) | 202 (4) | 470 (4) |

| Sitea | |||||

| Michigan | 66 (9) | 257 (10) | 400 (12) | 563 (11) | 1286 (11) |

| Pennsylvania | 117 (16) | 432 (16) | 810 (24) | 920 (19) | 2279 (19) |

| Texas | 171 (23) | 450 (17) | 575 (17) | 635 (13) | 1831 (16) |

| Washington | 209 (29) | 1031 (39) | 967 (29) | 1939 (39) | 4146 (35) |

| Wisconsin | 169 (23) | 457 (17) | 624 (18 | 900 (18) | 2150 (18) |

| Any high-risk condition | 591 (81) | 2279 (87) | 1312 (39) | 2790 (56) | 6972 (60) |

| Diabetes | 244 (33) | 1005 (38) | 190 (6) | 422 (9) | 1861 (16) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 263 (36) | 1193 (45) | 358 (11) | 924 (19) | 2738 (23) |

| Chronic lung condition | 153 (21) | 710 (27) | 463 (14) | 1158 (23) | 2484 (21) |

| Influenza vaccination in prior yeara | 212 (29) | 2067 (79) | 569 (17) | 3354 (68) | 6202 (53) |

| Smoker | 94 (13) | 186 (7) | 471 (14) | 414 (8) | 1165 (10) |

Data are presented as No. (%).

aExcludes 2011–2012 season.

Among study participants, 2806 of 11692 (24%) tested positive for influenza virus infection. Among these, 633 (23%) were infected with influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, 1510 (54%) with influenza A(H3N2), and 663 (24%) with influenza B, which included 561 (85%) with Yamagata lineage virus, 83 (13%) with Victoria lineage virus, and 19 (2.9%) with influenza B virus infections of undetermined lineage.

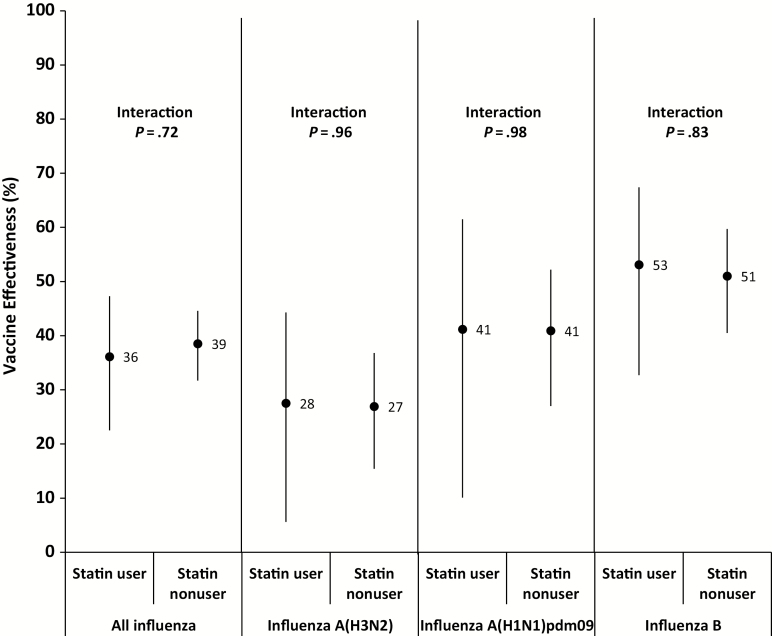

After adjusting for potential confounders, but not including statin use, the estimated VE against any influenza virus for all participants was 38% (95% CI, 32%–44%). When statin use was included in the model, the results were unchanged (VE, 38% [95% CI, 32%–44%]). When testing for effect modification by statin use, there was no significant interaction between statin use and vaccination status (P = .72; Supplementary Table). When stratifying by statin use, VE among statin users was 36% (95% CI, 22%–47%) and among nonusers it was 39% (95% CI, 32%–45%) (Table 2; Figure 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratio for Influenza Virus Infection, by Influenza Virus Type and Subtype by Vaccination Status and Exposure Group (Statin Users and Statin Nonusers)

| Influenza Virus Type | Vaccination Status/Exposure Group | No. of Case Patients/Total No. (%) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All influenza types and subtypes | Vaccinated statin user | 552/2627 (21) | 0.64 (.53–.78) |

| Unvaccinated statin user | 217/732 (30) | Ref | |

| Vaccinated nonuser | 1015/4661 (22) | 0.61 (.55–.68) | |

| Unvaccinated nonuser | 1022/3189 (32) | Ref | |

| Influenza A(H3N2) | Vaccinated statin user | 368/1686 (22) | 0.73 (.58–.94) |

| Unvaccinated statin user | 108/408 (27) | Ref | |

| Vaccinated nonuser | 560/2873 (20) | 0.73 (.63–.85) | |

| Unvaccinated nonuser | 441/1808 (24) | Ref | |

| Influenza A(H1N1) | Vaccinated statin user | 75/832 (9) | 0.59 (.39–.90) |

| Unvaccinated statin user | 43/258 (17) | Ref | |

| Vaccinated nonuser | 210/1543 (14) | 0.59 (.48–.73) | |

| Unvaccinated nonuser | 254/1054 (24) | Ref | |

| Influenza B | Vaccinated statin user | 94/1860 (5.0) | 0.47 (.33–.67) |

| Unvaccinated statin user | 57/500 (11) | Ref | |

| Vaccinated nonuser | 209/3303 (6.3) | 0.49 (.40–.60) | |

| Unvaccinated nonuser | 282/2147 (13) | Ref |

Seasons included for each analysis: all influenza subtypes: 2011–2012 to 2016–2017; H1N1: 2013–2014, 2015–2016; H3N2: 2011–2012, 2012–2013, 2014–2015, 2016–2017; influenza B: 2011–2012, 2012–2013, 2014–2015, 2015–2016, 2016–2017.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; Ref, referent group.

aModels adjusted for age group, sex, site, season, month of illness onset, self-rated health, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, and smoking status.

Figure 2.

Adjusted estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness, stratified by statin use and virus type or subtype, with point estimates and 95% confidence interval. “Interaction” refers to interaction term for statin use and vaccination. Models adjusted for age group, sex, site, season, month of illness onset, self-rated health, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, and smoking status. Seasons included for each analysis: all influenza: 2011–2012 to 2016–2017; H1N1: 2013–2014, 2015–2016; H3N2: 2011–2012, 2012–2013, 2014–2015, 2016–2017; influenza B: 2011–2012, 2012–2013, 2014–2015, 2015–2016, 2016–2017.

Statin use did not modify the effect of vaccination on influenza when analyzed by type and subtype (Table 2; Figure 2). For influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, VE among statin users was 41% (95% CI, 10%–62%) and 41% (95% CI, 27%–52%) among nonusers. For influenza A(H3N2), VE among statin users was 28% (95% CI, 6%–44%) and 27% (95% CI, 15%–37%) among nonusers. When the 2014–2015 season was excluded, VE for influenza A(H3N2) was higher for both groups, but did not significantly differ between statin users and nonusers (36% [95% CI, 12%–53%] vs 30% [95% CI, 17%–42%]; interaction term P = .66). For influenza B, VE among statin users was 53% (95% CI, 33%–67%) and 51% (95% CI, 41%–60%) among nonusers.

Statin use alone was not significantly associated with a reduced odds of medically attended influenza independent of vaccination, either for all influenza viruses or when analyzed separately by type and subtype, suggesting no protective effect of statin use independent of vaccination (data not shown). In an analysis stratified by prior vaccination, statins did not modify the effect of current season influenza vaccination among those vaccinated in the prior season (P = .70) or among those who were not vaccinated in the prior season (P = .27). Results were unchanged when analyzed for cases of influenza A(H3N2), influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, and influenza B viruses (data not shown). The type of statin (synthetic vs nonsynthetic statins) also did not have a significant effect. We examined site-specific variation in VE; although VE among statin users and nonusers varied considerably among sites, there was no consistent association between statin use and VE, against any influenza (Supplementary Figure 1) or against influenza A(H3N2) (Supplementary Figure 2), influenza A(H1N1), and influenza B viruses (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This analysis of >11000 adults aged ≥45 years with MAARI enrolled in the US Flu VE Network over 6 influenza seasons suggested similar influenza VE among those receiving statins during the time of influenza vaccination and those not taking statin medications. In contrast with previous studies, we found no evidence of significant modification of vaccine effects against any influenza or against specific influenza virus types/subtypes [5–7]. We also found no significant association between statin use and odds of influenza virus infection independent of vaccination status.

Several recent studies found an association between statin use and possible decreased vaccine effects [5–7]. In a post hoc analysis of >5000 persons >65 years of age enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of 2 different influenza vaccines over 2 seasons, Black et al compared hemagglutination inhibition (HI) geometric mean titers (GMTs) in statin users and nonusers. Statin use was not randomized. After adjusting for prevaccination HI titer, postvaccination GMTs were significantly lower among statin users compared with nonusers, with the difference most marked among those prescribed synthetic statins [7]. A retrospective observational study using data from a large healthcare organization compared incidence of MAARI, not confirmed as influenza, among statin users vs nonusers aged ≥45 years over 9 influenza seasons during periods with and without influenza virus circulation. After adjusting for differences in MAARI incidence during periods when influenza virus was not circulating, VE against MAARI was estimated to be lower among statin users compared with nonusers during periods with widespread circulation of influenza virus [6]. In another study, researchers used Medicare records to examine 1403651 statin users matched to nonusers, and found associations between statin use and 9%–10% increases in relative risks for influenza office visits and hospitalizations among vaccinated Medicare beneficiaries; the authors concluded that statin use around the time of vaccination does not substantially affect the risk of influenza-related medical encounters among older adults [13].

A multiyear study by McLean et al found a statistically significant association between statin use and decreased VE against laboratory-confirmed influenza A(H3N2) associated with MAARI, but not against other influenza types and subtypes, as well as a statistically significant association of statin use alone with decreased odds of influenza A(H3N2) virus infection, regardless of vaccination status [5]. We found that for all influenza types and subtypes, including influenza A(H3N2), there was no significant difference between statin users and nonusers, nor did we observe an effect of statin use on the odds of influenza virus infection, although we found that there was considerable variation in results among study sites. The study by McLean et al examined VE in the 2004–2005 through 2014–2015 influenza seasons and was conducted at the Marshfield Clinic, one of the US Flu VE Network sites included in this study, several years of which overlapped with that of our study. Although some influenza seasons and study enrollees from that site were included in both studies, the study by McLean et al used a different method for determining statin use in its patient population, was limited to 1 site, and covered a different range of influenza seasons, which may account for the different findings in the 2 studies.

Statins have some anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects [8–11, 22]. It is biologically plausible that they may interfere with the immune response elicited by vaccination [5–7]. However, associations between statin use and influenza VE are potentially subject to confounding by selective use of statins in individuals with reduced responsiveness to vaccination, whether as a result of comorbidities, prior vaccination, or other factors. Statin use was also inversely associated with markers of frailty and certain comorbidities among the elderly, potentially confounding the apparent association between statin use and mortality rates [23]. Furthermore, statin users—especially prevalent users (eg, those who have an indication for and adhere to long-term treatment)—also may have a constellation of healthier behaviors and characteristics associated with improved outcomes (the “healthy user effect”) [24–30], and may have different healthcare-seeking behavior than those not on statins but with similar underlying medical conditions. These differences can potentially bias estimates, and, although this study had extensive data on patients’ medical histories and other information and we were able to adjust for potential confounders when analyzing the effects of statins on VE, residual confounding may have occurred. This was an observational study, and as such may be more subject to bias than a randomized trial, which may not be feasible for ethical considerations given that both annual influenza vaccination and statin use for select individuals are considered standard of care for the study population.

The strengths of this study include laboratory confirmation of influenza infection and a large sample size, with a patient population drawn from multiple geographically diverse sites over 6 influenza seasons. Among its limitations are those inherent to observational studies, as well as potential misclassification of statin use due to incomplete pharmacy and medical record data. In addition, nonadherence to statin prescriptions has been shown in multiple studies, with observational studies indicating that statin adherence may drop to 50% at 6 months [31–33]. Dispensing data were only available for 1 site, and an unknown proportion of study participants may have been prescribed statins, but did not take them, potentially biasing the study toward the null. Furthermore, as in many studies examining statin use, there were significant differences between statin users and nonusers, and although we had information about their health status, underlying comorbidities, and other information, residual confounding may have masked any true effect of statin use on VE. Sample size may also have been inadequate to detect smaller effects of statins on VE.

Statins are among the most widely prescribed drugs in the world, and an estimated 38.6 million Americans currently take statin medications [34]. Although other studies have found an association between statin use and reduced vaccine effects, we did not observe any significant effect of statin use on influenza VE against laboratory-confirmed influenza among outpatients aged ≥45 years with MAARI. Both statin use and annual influenza vaccination according to current recommendations have many beneficial effects; our study findings are reassuring and do not suggest that either statin use or influenza vaccination guidelines need to be changed.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network study staff and participants. University of Pittsburgh: G. K. Balasubramani, Heather Eng, Theresa Sax, Krissy K. Moehling, Jonathan Raviotta, Michael Susick, Arlene Bullotta, Charles Rinaldo, Samantha Ford, Stephen Wisniewski; Baylor Scott and White Health: Michael Reis, Madhava Beeram, Alejandro Arroliga, Donald Wesson, Richard Beswick, Monica Weir, Lydia Clipper, Archana Nangrani, Anne Robertson, Jessica Pruszynski, Patricia Sleeth, Virginia Gandy, Teresa Ponder, Mary Kylberg, Hope Gonzales, Martha Zayed, Deborah Furze, Jeremy Ray, Jessica Rostocykj, Glen Cryer. Baylor College of Medicine: Pedro Piedra, W. Paul Glezen, Vasanthi Avadhanula, Alan Jewell, Kirtida Patel, Sneha Thaker; Marshfield Clinic Research Institute: Carla Rottscheit.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Financial support. This work was supported by the CDC through cooperative agreements with the University of Michigan (U01 IP000474), Kaiser Permanente Washington Research Institute (U01 IP000466), Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation (U01 IP000471), University of Pittsburgh (U01 IP000467), and Baylor Scott and White Healthcare (U01 IP000473). At the University of Pittsburgh, the project was also supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers UL1 RR024153 and UL1TR000005).

Potential conflicts of interest. M. G. has received grants from the CDC, MedImmune-AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. H. Q. M. and E. A. B. have received research grant support from Medimmune. R. K. Z. has received research grant support from Pfizer, Medimmune, Sanofi, and Merck and consulting fees from Medimmune. M. P. N. has received research funding from Pfizer and Merck & Co, Inc. A. S. M. has received consulting fees from Roche, Novartis, Sanofi, and Seqirus. L. J. has received research grant support from Novartis and Takeda. K. M. has received grants from MedImmune-AstraZeneca. M. J. has received grant from Sanofi Pasteur. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Reed C, Chaves SS, Daily Kirley P, et al. Estimating influenza disease burden from population-based surveillance data in the United States. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0118369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Darvishian M, Bijlsma MJ, Hak E, van den Heuvel ER. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine in community-dwelling elderly people: a meta-analysis of test-negative design case-control studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:1228–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goodwin K, Viboud C, Simonsen L. Antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly: a quantitative review. Vaccine 2006; 24:1159–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gu Q, Paulose-Ram R, Burt VL, Kit BK. Prescription cholesterol-lowering medication use in adults aged 40 and over: United States, 2003–2012. NCHS Data Brief 2014:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McLean HQ, Chow BD, VanWormer JJ, King JP, Belongia EA. Effect of statin use on influenza vaccine effectiveness. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:1150–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Omer SB, Phadke VK, Bednarczyk RA, Chamberlain AT, Brosseau JL, Orenstein WA. Impact of statins on influenza vaccine effectiveness against medically attended acute respiratory illness. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:1216–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Black S, Nicolay U, Del Giudice G, Rappuoli R. Influence of statins on influenza vaccine response in elderly individuals. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:1224–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Takemoto M, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001; 21:1712–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Terblanche M, Almog Y, Rosenson RS, Smith TS, Hackam DG. Statins and sepsis: multiple modifications at multiple levels. Lancet Infect Dis 2007; 7:358–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jain MK, Ridker PM. Anti-inflammatory effects of statins: clinical evidence and basic mechanisms. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2005; 4:977–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rosenson RS, Tangney CC, Casey LC. Inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine production by pravastatin. Lancet 1999; 353:983–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Myles PR, Hubbard RB, Gibson JE, Pogson Z, Smith CJ, McKeever TM. The impact of statins, ACE inhibitors and gastric acid suppressants on pneumonia mortality in a UK general practice population cohort. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009; 18:697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Izurieta HS, Chillarige Y, Kelman JA, et al. Statin use and risks of influenza-related outcomes among older adults receiving standard-dose or high-dose influenza vaccines through Medicare during 2010–2015. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67:378–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gaglani M, Pruszynski J, Murthy K, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus differed by vaccine type during 2013-2014 in the United States. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:1546–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ohmit SE, Thompson MG, Petrie JG, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the 2011-2012 season: protection against each circulating virus and the effect of prior vaccination on estimates. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:319–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jackson ML, Nelson JC. The test-negative design for estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine 2013; 31:2165–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vandermeer ML, Thomas AR, Kamimoto L, et al. Association between use of statins and mortality among patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infections: a multistate study. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:13–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kwong JC, Li P, Redelmeier DA. Influenza morbidity and mortality in elderly patients receiving statins: a cohort study. PLoS One 2009; 4:e8087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thompson MG, Naleway A, Fry AM, et al. Effects of repeated annual inactivated influenza vaccination among healthcare personnel on serum hemagglutinin inhibition antibody response to A/Perth/16/2009 (H3N2)-like virus during 2010-11. Vaccine 2016; 34:981–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Belongia EA, Skowronski DM, McLean HQ, Chambers C, Sundaram ME, De Serres G. Repeated annual influenza vaccination and vaccine effectiveness: review of evidence. Expert Rev Vaccines 2017; 16:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Chung J, et al. US Flu VE Investigators 2014-2015 influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States by vaccine type. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:1564–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shi J, Wang J, Zheng H, et al. Statins increase thrombomodulin expression and function in human endothelial cells by a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism and counteract tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced thrombomodulin downregulation. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2003; 14:575–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Glynn RJ, Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Levin R, Avorn J. Selective prescribing led to overestimation of the benefits of lipid-lowering drugs. J Clin Epidemiol 2006; 59:819–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brookhart MA, Patrick AR, Dormuth C, et al. Adherence to lipid-lowering therapy and the use of preventive health services: an investigation of the healthy user effect. Am J Epidemiol 2007; 166:348–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Polgreen LA, Cook EA, Brooks JM, Tang Y, Polgreen PM. Increased statin prescribing does not lower pneumonia risk. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1760–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shrank WH, Patrick AR, Brookhart MA. Healthy user and related biases in observational studies of preventive interventions: a primer for physicians. J Gen Intern Med 2011; 26:546–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Eurich DT, Padwal RS, Marrie TJ. Statins and outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with community acquired pneumonia: population based prospective cohort study. BMJ 2006; 333:999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yende S, Milbrandt EB, Kellum JA, et al. Understanding the potential role of statins in pneumonia and sepsis. Crit Care Med 2011; 39:1871–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jackson LA, Nelson JC. Association between statins and mortality. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:303–4; author reply 304–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patrick AR, Shrank WH, Glynn RJ, et al. The association between statin use and outcomes potentially attributable to an unhealthy lifestyle in older adults. Value Health 2011; 14:513–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ho PM, Magid DJ, Shetterly SM, et al. Medication nonadherence is associated with a broad range of adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2008; 155:772–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jackevicius CA, Mamdani M, Tu JV. Adherence with statin therapy in elderly patients with and without acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2002; 288:462–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wei MY, Ito MK, Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA. Predictors of statin adherence, switching, and discontinuation in the USAGE survey: understanding the use of statins in America and gaps in patient education. J Clin Lipidol 2013; 7:472–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Adedinsewo D, Taka N, Agasthi P, Sachdeva R, Rust G, Onwuanyi A. Prevalence and factors associated with statin use among a nationally representative sample of US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. Clin Cardiol 2016; 39:491–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.