Abstract

A 43-year-old male with a history of allergic rhinitis on chronic intranasal corticosteroids presented with complaints of a “black band” in his right eye visual field. On examination, he had subretinal fluid and lab tests and imaging studies including optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fluorescein angiography (FA) did not show any evidence of inflammatory, degenerative, or malignant process. He was diagnosed with central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR). Symptoms improved and the subretinal fluid resolved after the discontinuation of intranasal corticosteroid medication. Intranasal corticosteroids are rarely associated with CSCR. Patients and providers should be aware of the potential risk of vision loss caused by intranasal corticosteroids.

Introduction

Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) is a noninflammatory serous detachment of the neurosensory retina usually at the macula. The pathogenesis is not fully known but it is proposed to occur due to a combination of leakage from retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and dysfunctional RPE ion-pump function. Strong evidence shows association with a high endogenous cortisol condition or exogenous corticosteroid use.3–4 Local corticosteroid use in the form of topical creams has also been rarely implicated in the development of CSCR.2,5–8 There are only a few reports of CSCR associated with using intranasal or inhaler corticosteroids. Intranasal steroid use is pervasive due to the widespread prevalence of allergic rhinitis and upper respiratory infections. Persistent allergic rhinitis is known to be associated with environments that are humid, such as Hawaii or other Pacific Islands, and the use of intranasal corticosteroid medications may be even more ubiquitous in these regions.1 Of note, intranasal corticosteroid medications are now found over the counter which may contribute to their widespread use. Local side effects such as nasal irritation are generally well-known to patients and providers but the potential effects on vision are generally not known.2 We report a case of central serous chorioretinopathy associated with intranasal corticosteroid use that resolved after corticosteroid discontinuation. We will also review the current literature for the association of intranasal corticosteroid use and CSCR to highlight the association of this rare ocular side effect to medical practitioners who may interact on a daily basis with individuals using intranasal or inhaler corticosteroids.

Report

A 43-year-old male with a past medical history of allergic rhinitis controlled with tiamcinolone acetonide (Nasacort™), an intranasal corticosteroid, presented with complaints of decreased vision in the right eye for 4 days. A review of systems was otherwise unremarkable. Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/25 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye. Despite seemingly equal vision on examination, the patient was complaining of distorted vision and seeing a black “band-like” shadow located in the central visual field of the right eye. Intraocular pressure was within normal limits and visual fields were full in confrontation test. Slit lamp examination was unremarkable. Fundus exam revealed macular thickening due to clear subretinal fluid in the right eye. Optical coherence tomography (OCT), a noninvasive optical imaging modality, revealed subretinal fluid in the right eye and no fluid in the left eye (Figure 1). Fluorescein angiography, another imaging tool that utilizes fluorescence to highlight retinal vessels, revealed no delay in retinal perfusion (normal transit time), no macular or peripheral ischemia, and no signs of an inflammatory process such as vascular leakage in the macula (Figure 2). Blood pressure was within normal limits. Baseline laboratory studies including complete blood count (CBC) with differential, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), and partial thromboplastin time with international normalized ratio (PT INR) were within normal limits. The patient was diagnosed as having central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR). The only potential risk factor was identified as chronic use of over-the-counter intranasal corticosteroid. He also described himself as having type A personality. The patient was told to discontinue intranasal corticosteroid use. Subretinal fluid improved at 6 month follow-up examination and completely resolved at 12 months, when the patient reported resolution of his visual symptoms.

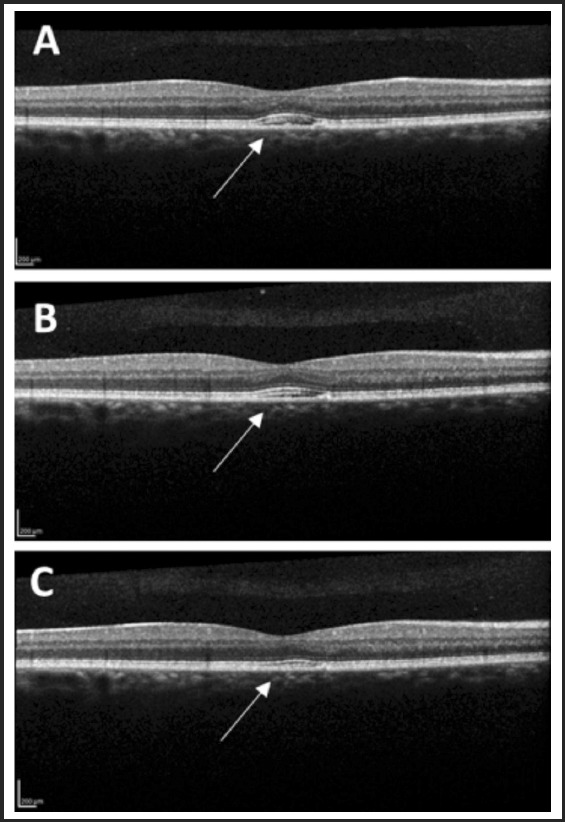

Figure 1.

Optical coherence tomography image of the macula showing interval reduction of mild subretinal fluid (arrow) from presentation (A), to 6 month (B), and 12 month (C) follow-up examinations.

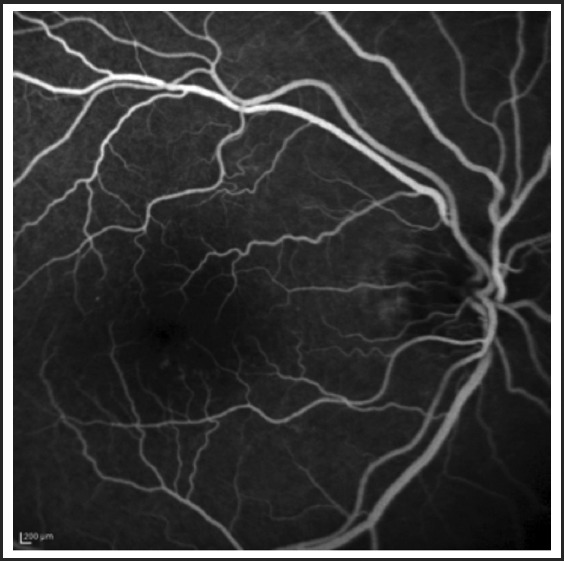

Figure 2.

Intravenous Fluorescein Angiography shows normal transit time, no macular ischemia or peripheral ischemia, and no leakage.

Discussion

We report a case of CSCR supposedly associated with chronic intranasal corticosteroid use. While there is no way to prove the causative connection between the development of serous retinal detachment and intranasal corticosteroid use, the resolution of subretinal fluid after discontinuation of corticosteroid is very suggestive, although subretinal fluid often resolves spontaneously even in non-corticosteroid associated CSCR. A Pubmed search of the English literature from 2000 to 2018 with the key words of “central serous chorioretinopathy”, or ”central serous retinopathy” AND “inhaled corticosteroids”, or “intranasal corticosteroid” found reports of 11 cases of CSCR associated with inhaled corticosteroid use (Table 1). Four of these cases were due to oral inhaled corticosteroid and seven were due to intranasal inhaled corticosteroid.5–8 In all cases, the subretinal fluid resolved after corticosteroid discontinuation.8

Table 1.

Case reports of CSCR associated with local steroid use (inhaled or topical)

| CSCR and Steroids Case Report - Updated 09 Nov 2017 | |||||||||||

| Publishing Date | Authors | Publishing Journal | Patient Age | Patient Sex | Affected Eye(s) | Initial visual acuity | Type of Treatment | Final Visual Acuity | CSCR Persistence | Type of Steroid | Steroid Administration |

| Oct 2016 | B Fardin, D J Weissgold | The British Journal of Ophthalmology | 40 | F | L | 20/15 right, 20/20-2 left | steroid discontinuation, observation | 20/15 right, 20/20 left | N | Fluticasone (glucocorticoid) | Oral inhaler |

| Oct–Dec 2013 | Gunjan Prakash, Jain Shephali, Nath Tirupati, Pandey D Ji | Middle East African Journal of Ophthalmology | 35 | M | R | 6/18 | 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose eye drops TID, observation | 6/6 | N | Dexamethasone (glucocorticoid) | Intranasal spray |

| Sep 2011 | Andrew J. Kleinberger, MD, Chirag Patel, MD, Ronni M. Lieberman, MD, Benjamin D. Malkin, MD | The Laryngoscope | 48 | F | Both | no data | steroid discontinuation, observation | no data | N | Fluticasone (glucocorticoid) | Intranasal spray |

| Sep 2002 | Lauren Y. Chan, Robert S. Adam, David N. Adam | The Journal of Dermatological Treatment | 64 | F | R | no data | steroid discontinuation, observation | no data | N | Betamethasone diproprionate (glucocorticoid) | Topical ointment |

| The Journal of Dermatological Treatment | 56 | F | Both | no data | steroid discontinuation, observation | no data | N | Betamethasone diproprionate (glucocorticoid), Clobetasol diproprionate (glucocorticoid), Betamethasone valerate (glucocorticoid) | Topical ointment | ||

| Oct 1997 | Robert Haimovici, MD, Evangelos S. Gragoudas, MD, Z ]ay S. Duker, MD, Raymond N. Sjaarda, MD, Dean Eliott, MD | Ophthalmology | 43 | M | R | 20/40 right, 20/25 left | steroid discontinuation, observation | 20/40 right, 20/25 left | N | Betamethasone diproprionate (glucocorticoid) | Oral inhaler |

| 31 | M | L | 20/20 right, 20/25 left | steroid discontinuation, observation | 20/15 right, 20/25 left | N | Triamcinolone acetonide (glucocorticoid) | Oral inhaler | |||

| 45 | F | L | 20/15 right, 20/40 left (corrected) | steroid discontinuation, observation | 20/15 right, 20/30- left (corrected) | N | Fluticasone proprionate (glucocorticoid) | Intranasal spray | |||

| 47 | F | Both | 20/20 right, 20/20 left | continued use of steroids, observation | 20/20 right, 20/20 left | Y | Beclomethasone diproprionate (glucocorticoid) | Oral inhaler | |||

| 24 | M | R | 20/60 right, 20/20 left | steroid discontinuation, observation | 20/25+2 right, 20/20 left | N | Beclomethasone diproprionate (glucocorticoid) | Intranasal spray | |||

| 41 | M | Both | 20/20 right, 20/20 left | continued use of steroids, observation | 20/20 right, 20/70 left | Y | Beclomethasone diproprionate (glucocorticoid) | Intranasal spray | |||

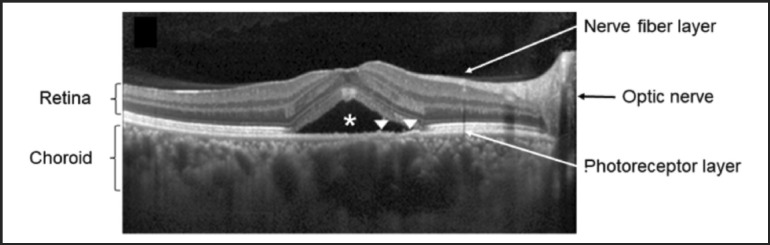

CSCR is hypothesized to be caused by a defective retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) ion-pump function or increased vascular permeability of a thick and hypervascular choroid (pachychoroid) (Figure 3), the vascular layer located between the retina and outer coating of the eye, the sclera. The innermost layer of the choroid is called choriocapillaris which is composed of a network of capillary vessels. One of the many physiologic functions of the choriocapillaris is to supply oxygen and nutrients to the outer retina and to remove waste products. It has been postulated that corticosteroids enhance fibroblastic growth, leading to capillary fragility in the choroidal vessels and causing suboptimal choriocapillaris function. Another theory is that corticosteroids may also interfere with ion transport across the RPE.9

Figure 3.

Optical coherence tomography of a patient with central serous chorioretinopathy showing thickened choroid and subretinal fluid. This is an OCT line scan through the fovea and shows subretinal fluid (asterisk) and abnormally thick choroid. Arrow heads indicate retinal pigment epithelium layer located between the retina and choroid. (Reproduced with permission and modifications under Creative Commons license from “Lee H, Bae K, Kang SW, Woo SJ, Ryoo NK, et al. Morphologic characteristics of choroid in the major choroidal thickening disease, studied by optical coherence tomography. PLOS ONE 2016;11(1):e0147139.)

Although no direct causes of CSCR have been found, a strong association between CSCR and increased exogenous or endogenous corticosteroids as well as a stressful lifestyle and type A personality has been established.10–11 The association between systemic corticosteroid use is documented frequently. However, even local corticosteroid use administered intranasally, orally inhaled, or placed topically may be linked to CSCR, as evidenced with our literature search. Like other similar cases, macular subretinal fluid in our patient resolved after cessation of intranasal corticosteroid, possibly indicating a diagnosis of CSCR related to intranasal corticosteroids. This patient had a self-described type A personality (a behavior pattern that was described in 1959 by two cardiologists as a complex in a person involved in a constant struggle to achieve success and has been linked to stress and coronary artery disease),12 which may have predisposed him to development of CSCR, as well. The major components of type A personality are described as (1) a competitive drive (2) a sense of urgency (3) an aggressive nature 4) a hostile temperament.13 It is hypothesized that constant and higher catecholamine drive in individuals with type A personality contributes to the multifactorial etiology of CSCR.

Our patient's symptoms improved and subretinal fluid resolved upon discontinuation of corticosteroid. Although CSCR is generally considered a benign condition with spontaneous resolution within 3–4 months in almost 80% of the cases, the subretinal fluid resorption is not universal and about one in five patient experience persistent subretinal fluid and vision loss lasting beyond 6 months.8,11,14 Patients and primary providers should be aware of the potential visual consequences of what may be considered “benign low-dose” corticosteroid, especially in patients who may be otherwise prone for the development of CSCR. This has broad implications in Hawaii and other tropical regions where intranasal corticosteroid use is widespread due to greater incidence of exacerbated atopic conditions.1

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identify a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wang DY, Chan A, Smith J. Management of allergic rhinitis: a common part of practice in primary care clinics. Allergy. 2004;59:315–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1398-9995.2003.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleinberger AJ, Patel C, Lieberman RM, Malkin BD. Bilateral central serous chorioretinopathy caused by intranasal corticosteroids: a case report and review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(9):2034–2037. doi: 10.1002/lary.21967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregory DL, Jones DC, Denton ER, Harnett AN. Acute visual loss induced by dexamethasone during neoadjuvant docetaxol. Clin Med Oncol. 2008;2:37–42. doi: 10.4137/cmo.s339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zamir E. Central serous retinopathy associated with adrenocorticotrophic hormone therapy: a case report and hypothesis. Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1997;235:339–344. doi: 10.1007/BF00937280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan LY, Adam RS, Adam DN. Localized topical steroid use and central serous retinopathy. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27(5):425–426. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2015.1136049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prakash G, Shephali J, Tirupati N, Ji PD. Recurrent central serous chorioretinopathy with dexamethasone eye drop used nasally for rhinitis. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2013;20(4):363–365. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.120001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fardin B, Weissgold DJ. Central serous chorioretinopathy after inhaled steroid use for post-mycoplasmal bronchospasm. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(9):1065–1066. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.9.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haimovici R, Gragoudas ES, Duker JS, Sjaarda RN, Eliott D. Central serous chorioretinopathy associated with inhaled or intranasal corticosteroids. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(10):1653–1660. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gass JDM, Little H. Bilateral bullous exudative retinal detachment complicating idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy during systemic corticosteroid therapy. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:737–747. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30960-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wynn PA. Idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy-a physical complication of stress? Occup Med (Chic III) 2001;51:139–140. doi: 10.1093/occmed/51.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loo JL, Lee SY, Ang CL. Can long-term corticosteroids lead to blindness? a case series of central serous chorioretinopathy induced by corticosteroids. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35:496–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hisam A, Rahman MU, Mashhadi SF, Raza G. Type a and type b personality among undergraduate medical students: need for psychosocial rehabilitation. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2014;30(6):1304–1307. doi: 10.12669/pjms.306.5541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yannuzi LA. Type-a behavior and central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 1987;7(2):111–131. doi: 10.1097/00006982-198700720-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilbert CM, Owens SL, Smith PD, Fine SL. Long-term follow-up of central serous chorioretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68:815–820. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.11.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]