Abstract

Background

The most common cause for trigeminal neuralgia is contact of the trigeminal nerve with an offending vessel which is also observed routinely in many asymptomatic patients. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine when an asymptomatic Neuro Vascular Contact (NVC) turned into a neurovascular conflict and made the patient symptomatic.

Methods

All patients who underwent Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) brain with clinical diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia formed the study group and all cases of sensorineural hearing loss formed the control group.

Results

Out of 51 cases of trigeminal neuralgia 27 were males and 24 were females. The neurovascular contact was seen in 41 (80.4%) cases and 17 (28.3%) controls. Change in caliber of trigeminal nerve was seen in 27 (52.9%) cases and only in 01 (1.66%) control. Arterial imprint on nerve was seen in 26 (50.9%) cases and 01 (1.66%) control. Distortion of the course of nerve was seen in 12 (23.5%) cases and 01 (1.66%) control. Superior cerebellar artery was commonest vessel seen in contact with nerve on affected side in 25 (61%) cases.

Conclusion

Demonstrating neurovascular contact alone is not enough for diagnosis of conflict as it is also present in some asymptomatic individuals, therefore it is important to identify thinning of nerve, arterial imprint or grooving and distortion in course of nerve, as these are more reliable signs of a conflict between the vessel and the nerve, and these cases are best treated surgically by Micro Vascular Decompression (MVD).

Keywords: MRI, Trigeminal neuralgia, Neurovascular contact/conflict

Introduction

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) also known as tic douloureux is the neuralgic pain in the distribution of sensory supply area of the trigeminal nerve (Vth cranial nerve) affecting the face, which is typically intense, paroxysmal, sharp and lancinating. The most common cause described in literature for trigeminal neuralgia is mechanical contact of the trigeminal nerve with an offending vessel which in most cases is an artery.1 3D Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) with constructive interference in steady-state (CISS) sequence which is used for evaluation of cerebellopontine angle and the inner ear produces excellent contrast between the nerves and vessels and allows us to study the neurovascular contact in detail.2 Neurovascular contact (NVC) between trigeminal nerve and a vessel is also observed routinely in many asymptomatic patients who undergo MRI for some other problem such as sensorineural hearing loss. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine when an asymptomatic NVC turned into a neurovascular conflict and made the patient symptomatic. In this single-center case control study we have evaluated the MRI findings in patients with trigeminal neuralgia and control group with no symptoms of trigeminal neuralgia.

Materials and methods

Setting

The study was conducted at the department of Radiodiagnosis and Imaging of a tertiary care hospital and teaching institution.

Study design

Case control study.

Inclusion criteria

All patients who underwent MRI brain and CISS sequence for clinical diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia in our institute from 01 April 2006 to 31 March 2016 formed the study group.

Control group

As per our institution protocol all cases of sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) undergo evaluation with 3D CISS sequence after routine MRI of brain. The Field of view (FOV) for CISS sequence in these cases also includes the course of trigeminal nerve in pontine cistern. Therefore, these cases from 01 January 2012 to 30 April 2016 formed the controls group.

Exclusion criteria

-

(a)

Patients found to have cerebellopontine angle tumor or space occupying lesions in pontine cisterns were excluded from the study.

-

(b)

Children with SNHL were excluded from the control group.

Data acquisition

All cases diagnosed clinically as trigeminal neuralgia in the study period were first identified by searching in the MRI report database with the keyword ‘trigeminal neuralgia’. These patients formed the study group.

All cases diagnosed clinically as sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) from January 2012 to April 2016 were identified by searching in the MRI report database with the keyword ‘Sensorineural hearing loss/SNHL’. These patients formed the control group.

Imaging parameters

All cases and controls were done on 1.5T Siemens (Germany) Somatom symphony MRI scanner. All cases and controls underwent a routine MRI of brain followed by high spatial resolution 3D CISS sequence with following parameters TR 750, TE 116 and slice thickness of 1 mm.

Image analysis

All 3D CISS sequences of cases and controls were interpreted by two radiologists with more than 10 years experience in Neuroimaging. They were blinded to the clinical findings and each other. The discrepancy if any was resolved with consensus. The vascular contact with trigeminal nerve was determined in two orthogonal planes i.e. axial and sagittal. It was considered to be present if the contact was demonstrable in both these planes (Fig. 1a and b).

Fig. 1.

(a and b) Axial and Sagittal CISS images showing vascular contact with trigeminal nerve in pontine cistern (arrow).

All cases in the study group and controls were recorded for age, sex, side affected, presence or absence of neurovascular contact, arterial branch, distance from pons, thinning in caliber of nerve, arterial imprint/grooving on nerve and distortion in the course of nerve.

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed by using Statistical packages for social sciences 22 to determine the means and proportions. Chi-square test was used to compare the changes in the trigeminal nerve at the site of NVC between the two groups. p values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Informed consent

Institutional Ethical committee waiver for consent and retrospective data was obtained for the study. Permission from the institution was also obtained for analyzing the data. Identity of patients was kept confidential.

Results

During the study period, ranging from 01 April 2006 to 31 March 2016, 53 cases clinically diagnosed as trigeminal neuralgia underwent MRI examinations out of which 02 cases were found to have intracranial tumors (01 epidermoid and 01 acoustic schwannoma) and were excluded from the study. Out of 51 cases of trigeminal neuralgia 27 were males and 24 were females (male:female: 1.1:1). 60 controls from a period of 01 January 2012 to 30 April 2016 were subjected to MRI with male to female ratio 1.6:1. The maximum number of patients (14 cases) with trigeminal neuralgia were seen in 41–50 and 61–70 year age groups followed by 10 in 51–60, 9 in 31–40 and 4 in 71–80 year age group.

The mean distance of neurovascular contact from Pons in patients with trigeminal neuralgia was 3.16 mm and 5.71 mm in cases and controls respectively with p < 0.001 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distance of neurovascular contact from Pons (in mm) in cases and controls.

| Mean | Std Deviation | t value (difference) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 41) | 3.16 | 2.33 | 4.37 | <0.001 |

| Control (n = 17) | 5.71 | 0.85 |

The neurovascular contact between trigeminal nerve and vessel was seen in 41 (80.4%) cases of trigeminal neuralgia and 17 (28.3%) controls who had undergone MRI for SNHL with p = .000 and χ2 = 29.945 (Table 2). Change in caliber of trigeminal nerve was seen in 27 (52.9%) cases and only in 01 (1.66%) control with p = .000 and χ2 = 38.425 (Table 2). Arterial imprint/grooving on the trigeminal nerve with neurovascular contact was seen in 26 (50.9%) cases and 01 (1.66%) control with p = .000 and χ2 = 38.425 (Table 2). Distortion of the course of trigeminal nerve was seen in 12 (23.5%) cases and 01 (1.66%) control with p = .000 and χ2 = 12.743 (Table 2). Post hoc power for neurovascular contact, thinning in caliber of nerve and arterial imprint/grooving on nerve was 100% and for distortion of course of nerve was 94.52%.

Table 2.

Neurovascular contact and effect on trigeminal nerve among cases and controls.

| Variable | Cases | Controls | Chi-square test | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 51) | (n = 60) | |||

| Neurovascular contact present | 41 | 17 | 29.95 | <0.001 |

| Thinning in caliber of nerve | 27 | 01 | 38.42 | <0.001 |

| Arterial imprint/grooving on nerve | 26 | 01 | 36.42 | <0.001 |

| Distortion of course of nerve | 12 | 01 | 12.74 | <0.001 |

Superior cerebellar artery (SCA) was seen in contact with the trigeminal nerve on affected side in 25 (61%) cases and in 12 (70.5%) controls (Table 3). Anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) was seen in contact with the nerve in 07 (17%) cases and 02 (11.7%) controls (Table 3). Both SCA and AICA were seen in contact with the trigeminal nerve in 03 (7.3%) cases and vessel contact could not be evaluated in 06 (14.7%) cases and 03 controls due to technical reasons. Post hoc power for SCA contact with nerve was 96.95% and for AICA contact with nerve was 59.51%.

Table 3.

Vessel in contact among cases and controls.

| Vessel | Casesa | Controlsb | Chi-square test | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 45) | (n = 57) | |||

| Superior cerebellar Artery (SCA) | 25 | 12 | 12.95 | <0.001 |

| Anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) | 07 | 02 | 04.53 | 0.33 |

| SCA and AICAc | 03 | 00 | – | – |

06 cases could not be evaluated.

03 Controls could not be evaluated.

Chi square value not calculated since no controls had the contact.

Discussion

Incidence of trigeminal nerve in general population has been variable in different studies, Katusic et al. reported an overall incidence of 4.3 per 100,000 in their study population with higher incidence in females than males.3 However in this study the trigeminal neuralgia was observed in more males (27 cases) than females (24 cases) with male:female ratio of 1.1:1. In this study it was found that maximum number of 14 cases each were seen in 41–50 and 61–70 year age groups, followed by 10 in 51–60, 9 in 31–40 and 4 in 71–80 year age group. This is in conformity with the literature where it has been reported that the disease typically affects patients in middle and later life with maximum incidence reported in 61–70 year age group.

Trigeminal neuralgia is associated with variety of conditions such as multiple sclerosis, injury to nerve and space occupying lesions in pontine cistern but the most common cause is the vascular contact. The exact pathophysiology of vascular contact resulting in pain in the facial region in the distribution of trigeminal nerve remains controversial, however it is agreed that the vascular contact causes focal demyelination of the trigeminal nerve which is commonly observed in the root entry zone (REZ), this leads to ephaptic transmission, in which there is cross talk between one nerve fiber and another resulting in altered pain mechanisms with ensuing neuropathic pain.4 REZ is the cisternal part of the trigeminal nerve close to the entrance into the pons and extends for a distance of 4–5 mm from pons.5 It represents a transition zone between the peripheral myelin, derived from Schwann cells, and central myelin, derived from oligodendroglia. As per this anatomical organization, the junctional zone is thinner and more vulnerable to vascular compression than the other nerve's segments. In this study the mean distance of vascular contact from pons (Fig. 2) was found to be 3.16 mm in patients presenting with trigeminal neuralgia which supports the cross talk hypothesis and reiterates the fact that the REZ is the most vulnerable part for neurovascular conflict6 (Table 1). Even though 17 controls also showed neurovascular contact but were asymptomatic, this could be explained by the fact that the mean distance of contact in these patients was 5.71 mm which is just beyond the REZ which makes the nerve less vulnerable for anatomical changes resulting due to vascular contact (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Axial image showing loop of SCA, 2 mm from pons, in contact with trigeminal nerve at REZ (arrow). Also note early thinning in caliber of right nerve as compared to left side.

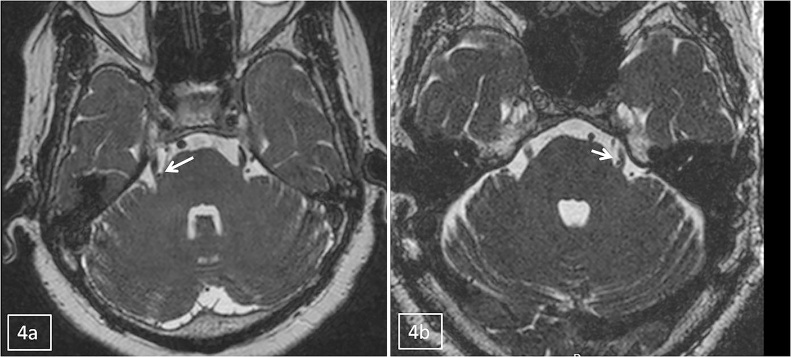

The neurovascular contact between trigeminal nerve and vessel was seen in 41 (80.4%) cases (Fig. 2) though this is significant (p < 0.001) but NVC was also seen in 17 (28.3%) controls (Table 2). To say with conviction that there exists a conflict between the offending vessel and nerve, merely a lone criterion of presence of NVC is not sufficient. Other criteria studied in this study were the anatomical changes in the nerve which are more frequently seen in the REZ were thinning in caliber of nerve, arterial imprint/grooving on the nerve or distortion of the course of nerve. The thinning in caliber of trigeminal nerve (Fig. 3) was seen in 52.9% cases, arterial imprint/grooving on the trigeminal nerve (Fig. 4a and b) was seen in 50.9% cases and distortion of the course of trigeminal nerve (Fig. 5) was seen in 23.5% cases, these findings were significant with p < 0.001. Also the post hoc power for NVC, thinning of caliber and arterial imprint was 100% and for distortion of course of nerve was 94.52%. All these anatomical changes in the nerve result in the focal demyelination or stretching of nerve which is the basis of symptoms in these patients as discussed above therefore these findings are highly significant as they point toward a potential conflict between the nerve and the vessel. Sherif et al. in their study reviewed MRI of 782 cases of neurovascular compression to analyze the imaging criteria and found that distortion of course of nerve and reduction in caliber of nerve were significant findings, however they did not consider arterial imprint/grooving on the nerve in their study and the findings were not compared to control group which was done in this study.6

Fig. 3.

Axial image showing vascular contact at REZ with thinned out caliber of trigeminal nerve on left side (arrow).

Fig. 4.

(a and b) Axial images of two different patients showing vascular loops at root entry zone with arterial imprint/grooving on the trigeminal nerves (arrow).

Fig. 5.

Axial image showing distortion in the course of right nerve (arrow) due to contact with vascular loop at the REZ.

SCA or its branch has been described in the literature as the most common vessel which comes in contact with the trigeminal nerve in the pontine cistern.6 This is followed by AICA and its branch and in some patients both SCA and AICA may show contact with the affected nerve. Yoshino et al.2 found SCA responsible for NVC in 46%, AICA in 17% both SCA and AICA in 9%, basilar artery in 4%, and posterior cerebellar artery in 2% and vein in 6% of cases. In this study it was found that SCA was responsible for NVC in 61% and AICA in 17% and both SCA and AICA in 7.3% of cases (Table 3), the NVC could not be evaluated in 03 (14.7%) of cases as the vessels could not be traced to their origin in the given field of view.

Limitations of the study were the lack of correlation with post op findings as all the cases were not taken up for surgery. Secondly, since the post hoc power of contact of AICA was 59.51% the significance of its contact with nerve could not be established with certainty and would require a study with larger sample size.

It is important for a radiologist to differentiate between a simple neurovascular contact from a potential neurovascular conflict while reporting the cases of trigeminal neuralgia as this may help the clinician in deciding whether to give a therapeutic trial of medicines or opt for microvascular decompression (MVD), which is a surgical procedure, for managing these cases. MVD produces rapid relief in symptoms. Immediate post op respite from pain occurs in 87–98% of patients, roughly 80% of patients remain symptom-free 1 year after the procedure.7 Therefore, the aim of radiologist should be to identify a potential neurovascular conflict in symptomatic cases as these cases can be better managed surgically.

Conclusion

Trigeminal neuralgia is a neuropathic pain which occurs in the distribution of trigeminal nerve. MRI is the imaging modality of choice to identify the cause in these cases. The neurovascular contact has been identified as the most common cause in these patients. But demonstrating NVC alone is not enough as it is also present in some asymptomatic individuals, therefore it is important to identify thinning of nerve, arterial imprint or grooving and distortion in course of nerve as these are more reliable signs of a conflict between the vessel and the nerve as these cases can be best treated surgically by MVD.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Sindou M., Howeidy T., Acevedo G. Anatomical observations during microvascular decompression for idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: prospective study in a series of 579 patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s701-002-8269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshino N., Akimoto H., Yamada I. Trigeminal neuralgia: evaluation of neuralgic manifestation and site of neurovascular compression with 3D CISS MR imaging and MR angiography. Radiology. 2003;228:539–545. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2282020439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katusic S., Beard C.M., Bergstralh E., Kurland L.T. Incidence and clinical features of trigeminal neuralgia, Rochester, Minnesota, 1945–1984. Ann Neurol. 1990;27(January (1)):89–95. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Love S., Coakham H.B. Trigeminal neuralgia: pathology and pathogenesis. Brain. 2001;124(December (Pt 12)):2347–2360. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.12.2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang E., Naraghi R., Tanrikulu L., Hastreiter P. Neurovascular relationship at the trigeminal root entry zone in persistent idiopathic facial pain: findings from MRI 3D visualisation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1506–1509. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.066084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elainia S., Magnanb J., Devezeb A., Girardc N. Magnetic resonance imaging criteria in vascular compression syndrome. Egypt J Otolaryngol. 2013;29:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haller S., Etienne, KÖvari E. Imaging of neurovascular compression syndrome: trigeminal neuralgia, hemifacial spasm, vestibular paroxsia and glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37(August (8)):1384–1392. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]