Abstract

Membrane models of the stratum corneum (SC) lipid barrier, either healthy or affected by recessive X-linked ichthyosis, constructed from ceramide [Cer; nonhydroxyacyl sphingosine N-tetracosanoyl-d-erythro-sphingosine (CerNS24) alone or with omega-O-acylceramide N-(32-linoleyloxy)dotriacontanoyl-d-erythro-sphingosine (CerEOS)], FFAs(C16–24), cholesterol (Chol), and sodium cholesteryl sulfate (CholS) were investigated. X-ray diffraction (XRD) revealed a previously unreported polymorphism of the membranes. In the absence of CerEOS, the membranes formed a short lamellar phase (SLP; the repeat distance d = 5.3 nm), a medium lamellar phase (MLP; d = 10.6 nm), or very long lamellar phases (VLLP; d = 15.9 and 21.2 nm). An increased CholS-to-Chol ratio modulated the membrane polymorphism, although the CholS phase separated at ≥ 7 weight% (of total lipids). The presence of CerEOS led to the stable long lamellar phase (LLP) with d = 12.2 nm and prevented VLLP formation. Our XRD results agree well with recently published cryo-electron microscopy data for vitreous skin sections, while also revealing new structures. Thus, lamellar phases with long repeat distances (MLP and VLLP) may be formed in the absence of omega-O-acylceramide, whereas these ultralong Cer species likely stabilize the final SC lipid architecture of LLP by riveting the adjacent lipid layers.

Keywords: ceramide, skin, extracellular matrix, membranes/model, X-ray crystallography, cholesterol, cholesteryl sulfate, skin barrier

The stratum corneum (SC) has evolved to protect the body from desiccation and thus to ensure the terrestrial life of mammals, including humans (1). This outermost skin layer also hampers the entry of possibly harmful substances from the environment. SC consists of several layers of cornified cells, corneocytes, and extracellular lipid matrix, which represents the major skin-permeability barrier (2). The SC extracellular lipid matrix consists mainly of ceramides (Cers), FFAs, and cholesterol (Chol) at an ∼1:1:1 molar ratio (supplemental Fig. S1). These lipids are highly organized in the lamellae aligned parallel to the skin surface (3, 4). Skin Cers are a class of sphingolipids comprising, to date, 15 classes of free Cers, including the ultralong ω-O-acylceramides (ω-O-acylCers), which contain 30–34C acyl chains with a linoleic acid ester-linked to the ω-hydroxyl terminus (5–9); for a review, see Ref. 10.

The lipid matrix of isolated SC has a lamellar characteristic and a long repeat distance (d) of ∼13 nm, as was revealed by electron microscopy (11–13) and/or by X-ray diffraction (XRD) (12, 14, 15). The so-called long periodicity phase with d ∼ 13 nm was reconstructed in vitro from isolated skin lipids (16–18) and lipids synthesized in a laboratory (19). A separated Chol with d ∼ 3.4 nm and a short periodicity phase with d ∼ 6.4 nm were found to coexist with the long periodicity phase in isolated SC by XRD (20). Chol also separates in vitro in model SC lipid membranes, creating a distinct phase that is detectable by XRD (21, 22). A key role of ω-O-acylCers for formation of the long periodicity phase was demonstrated in vitro in model lipid membranes with isolated pig skin Cers (18). A correlation was found ex vivo between a decreased fraction of ω-O-acylCer and changes in the XRD patterns of SC in healthy humans (23) and in patients with atopic dermatitis (24). Several models of the molecular arrangement of the SC extracellular lipid domains have been proposed; however, they remain under discussion (25–28).

In this work, we investigated the lamellar organization in a membrane model of recessive X-linked ichthyosis (RXLI). RXLI is a genetic skin disease with impaired processing of sodium cholesteryl sulfate (CholS) to Chol. In healthy skin, CholS is gradually distributed across the SC, from 5 weight% at the stratum granulosum/SC boundary to 1 weight% in the outer SC (29, 30). In RXLI, mean CholS levels in the SC are ∼5- to 10-fold elevated, whereas free Chol levels are ∼50% reduced in comparison to healthy skin (4). The disruption of CholS desulfation leads to an abnormal permeability barrier, abnormal desquamation, and the presence of nonlamellar domains within the SC extracellular spaces (31, 32). A high CholS level in model lipid mixtures induces the formation of an additional less-ordered phase (33) and alterations in the electron spin probe microenvironment (34). Rehfeld et al. (34) proposed that different H-bonding of CholS relative to Chol may play a role in RXLI pathogenesis. However, the contributions of increased CholS and decreased Chol to the abnormalities in lipid organization and permeability in RXLI are unclear.

Thus, we aimed at studying the effects of CholS on SC lipid membranes based on N-tetracosanoyl-d-erythro-sphingosine d18:1/24:0 (CerNS24). During the initial experiments, we observed an extraordinary and yet unreported polymorphic behavior of our SC lipid membranes, which was modulated by the Chol/CholS content variation and sample preparation method. Here, we show, for the first time, that SC lipids without ω-O-acylCer can self-organize in patterns with not only a short repeat distance, but also with medium or very long repeat distances. The formation of these structures is further compared with the structural behavior of the SC model containing N-(32-linoleyloxy)dotriacontanoyl-d-erythro-sphingosine d18:1/h32:0/18:2 (CerEOS). The experiments with various Chol/CholS ratios further show that the simple SC model of RXLI can mimic structural defects similar to those reported in the SC of RXLI patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and material

CerNS24 was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). CerEOS was synthesized as described in Ref. 35. Chol from lanolin, CholS, hexadecanoic acid, octadecanoic acid, eicosanoic acid, docosanoic acid, tetracosanoic acid, and solvents (all analytical or HPLC grade) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie Gmbh (Schnelldorf, Germany). Single side polished Si substrates (111, N-type/Phos-dopant) of 25 × 50 × 0.5 mm3 were purchased from Crystal GmbH (Berlin, Germany). Esco® microscope cover glasses of 22 × 22 mm2 were from Erie Scientific LLC (Portsmouth, NH).

Preparation of model lipid membranes

A mixture of FFAs with 16, 18, 20, 22, and 24 carbons [FFAs(16–24)] were mixed at a molar ratio corresponding to the native composition of human skin FFA: 1.8% hexadecanoic acid, 4.0% octadecanoic acid, 7.6% eicosanoic acid, 47.8% docosanoic acid, and 38.8% tetracosanoic acid (36). The lipids [CerNS24 or CerEOS/CerNS24 mixture, FFAs(16–24), Chol, and CholS] were dissolved in 2:1 chloroform/methanol (v/v) and mixed at the molar fractions specified in Table 1. The lipid solutions were dried, redissolved (see below), and applied on cover glasses or Si substrates in either of the following manners:

TABLE 1.

The composition of the model lipid membranes

| Sample Labeling (Chol/CholS molar ratio) | Molar Fraction | Weight% CholS (of total lipids) | ||||

| CerNS24 | CerEOS | FFA(16–24) | Chol | CholS | ||

| No CholS | ||||||

| 1/0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.45/0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.45 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.45/0+EOS | 0.7 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.45 | 0 | 0 |

| Controls | ||||||

| 1/0.13 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.13 | 5 |

| 1/0.03 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.03 | 1 |

| RXLI model | ||||||

| 0.85/0.15 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 5 |

| 0.8/0.2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 7 |

| 0.7/0.3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 10 |

| 0.6/0.4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 14 |

| 0.5/0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 17 |

| 0.4/0.6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 20 |

Spraying.

The dry lipid was dissolved in 2:1 hexane/96% ethanol (v/v) at a concentration of 4.5 mg/ml, and 3 × 100 μl of the lipid solution was sprayed on a wafer under a stream of nitrogen at a flow rate of 10.2 μl/min using a Linomat V (Camag, Muttenz, Switzerland) equipped for additional y-axis movement.

Dropping at 50°C.

The 17–60 μl of 2:1 hexane/96% ethanol (v/v) was added per 1 mg of dry lipid. The mixture was homogenized using an ultrasound bath at 50°C until a homogeneous transparent viscous liquid was created. The concentration depended on the solubility of each lipid sample. The liquid, which was continuously heated to 50°C, was applied in several subsequent steps on a wafer preheated to 50°C using a 100 μl gastight syringe preheated to 50°C. Before each application, the syringe and wafer were preheated again.

The prepared lipid membranes were dried overnight under a vacuum over P4O10 and solid paraffin in a desiccator and then annealed according to the following two protocols:

Annealed at 90°C.

The samples were heated to 90°C, equilibrated at this temperature for 10 min, and slowly (∼3 h) cooled to room temperature.

Annealed at 70°C/H2O.

The samples underlaid with aluminum rings were sealed in aluminum containers with distilled water at the bottom (water was not in contact with the lipids) and heated to 70°C, equilibrated at this temperature for 10–30 min, and slowly (∼3 h) cooled to room temperature.

The prepared membranes were not specifically hydrated and were stored at 2–6°C. Before the XRD measurements, they were equilibrated at room temperature for 24 h.

XRD

The XRD data were collected at ambient room temperature and humidity with an X’Pert PRO θ-θ diffractometer (PANalytical B.V., Almelo, The Netherlands) with parafocusing Bragg-Brentano geometry using CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å, U = 40 kV, I = 30 mA) or CoKα radiation (λ = 1.7903 Å, U = 35 kV, I = 40 mA) in modified sample holders over the angular range of 0.6–30° (2θ). Data were scanned with an ultrafast position-sensitive linear (1D) X’Celerator detector with a step size of 0.0167° (2θ) and a counting time of 20.32 s·step−1. Certain samples were measured in an elevated position against the origin using an Empyrean θ-θ diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical B.V., Almelo, The Netherlands) with Bragg-Brentano geometry using CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å, U = 40 kV, I = 20–40 mA). The shift of the origin was subtracted from the resulting XRD patterns mathematically. The data were evaluated using X’Pert Data Viewer software (PANalytical B.V.) and Jandel Scientific Peakfit 2.01 software (AISN Software). The peaks were fitted by the Lorentzian function above a linear background. The XRD patterns show the unscaled raw scattered intensities as a function of the scattering vector Q (nm−1). The repeat distance d (nm) characterizes the spacing between adjacent scattering planes for parallel lipid layers arranged in a 1D lattice. The XRD patterns of the lamellar phases exhibit a set of Bragg reflections with reciprocal spacings in the characteristic ratios of Qn = 2πn/d (Miller index n = 1, 2, 3…). The d was obtained from the slope a of a linear regression of the dependence Qn = a.n + q0, according to the equation d = 2π/a, where q0 is a constant corresponding to a shift of the origin. The XRD reflection positions of all the lamellar structure types are listed in supplemental Table ST1.

RESULTS

Polymorphism of CerNS24-based model membranes: formation of MLP and VLLP in the absence of ω-O-acylCer

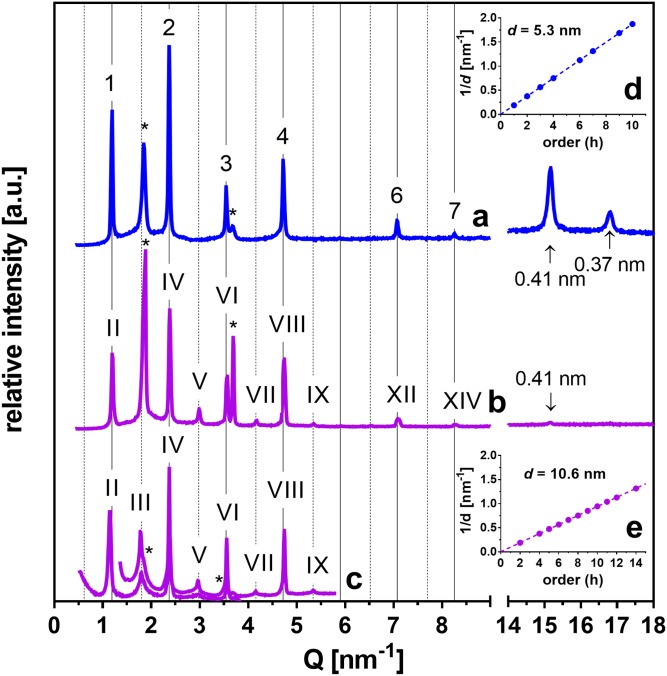

First, we constructed simple SC lipid models using CerNS24, FFA(16–24), and Chol in equimolar ratios with 1 and 5 weight% of CholS (samples labeled 1/0.03 and 1/0.13, respectively; Table 1). The lipids were deposited by spraying and were annealed at 90°C (17). The XRD pattern of the 1/0.13 sample (Fig. 1A) contained several reflections (supplemental Table ST1) attributed to the orders 1, 2, 3…up to 10 of the diffraction from the periodically arranged lipid lamellae forming the short lamellar phase (SLP) with a repeat distance d = 5.3 nm (Fig. 1D). The region of long-range arrangement further contained reflections attributed to separated Chol. In the region of short-range arrangement (Q-range 14–18 nm−1 in Fig. 1A), we detected two reflections that provided the repeat distances 0.41 and 0.37 nm, which were most likely derived from the orthorhombic packing of lipid polymethylene chains. This behavior was in accordance with Ref. 17.

Fig. 1.

Formation of the SLP (A) and MLP (B, C) in the SC model membranes. XRD patterns in the regions corresponding to the long-range (left-hand side) and short-range (right-hand side) arrangements of the 1/0.13 sample [i.e., CerNS24/FFA(16–24)/Chol/CholS at the 1/1/1/0.13 molar ratio] forming a SLP (A) or MLP (B). C: The 0.45/0 sample with the molar ratio CerNS24/FFA(16–24)/Chol/CholS = 1/1/0.45/0 forming MLP measured at two configurations of the diffractometer providing small differences in the background of overlapping regions. Linear regressions of the dependence of 1/d on the reflection order h for SLP (D) and MLP (E). Arabic numerals, Roman numerals, and asterisks indicate SLP, MLP, and separated Chol, respectively. Arrows indicate the reflections of chain packing. Full and dashed grid lines predict the positions of SLP and odd MLP reflections, respectively. The intensities of different measurements are not scaled and are shown in arbitrary units (a.u.).

In the preliminary experiments, one of the 1/0.13 samples was allowed to evaporate more slowly during the spraying process. The XRD pattern of this sample (Fig. 1B) showed a set of reflections (supplemental Table ST1) of the orders II, IV, V…up to XIV corresponding to d = 10.6 nm (in addition to separated Chol). The first-order reflection of this phase was not detected due to the instrument limitations. The used XRD experimental configuration and its effects on the shape of the XRD patterns are thoroughly discussed in supplemental data. The third-order reflection coincided with the separated Chol peak at Q = 1.86 nm−1. The dependence of the peak positions in 1/d on their order (h) was nevertheless clearly linear (Fig. 1E), confirming a lamellar phase denoted here as the medium lamellar phase (MLP). The peak indices (II, IV, V … up to XIV) were attributed according to the scheme proposed in Ref. 37 and will be further discussed. In the region of the short-range arrangement, a weak reflection at the repeat distance of 0.41 nm was detected.

The MLP formation was further reproduced using a modified preparation protocol (Fig. 1C). To avoid the overlap of Chol and MLP reflections, the Chol content was decreased to 45%, and no CholS was used (0.45/0 sample). The membrane was prepared by dropping the lipid solution at 50°C instead of spraying at room temperature, followed by annealing at 70°C/H2O for 10 min. This sample enabled us to resolve the third-order MLP peak from Chol (only two shoulders at the third- and sixth-order MLP reflections indicated separated Chol) to further confirm this lamellar structure.

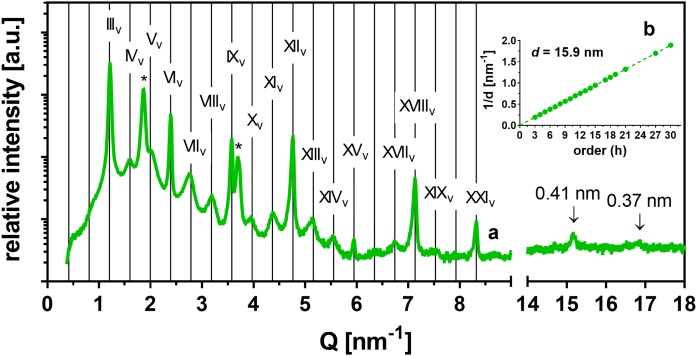

Next, we prepared the 1/0.03 and 1/0.13 samples by dropping the lipid solution at 50°C, but the annealing at 70°C/H2O was prolonged to 30 min. These samples displayed substantially different XRD patterns relative to those in Fig. 1. The 1/0.03 sample (i.e., with 1% CholS; Fig. 2A and the dark blue line in Fig. 3) showed separated Chol and a set of strong reflections resembling SLP and weak reflections apparently arranged in pairs in the gaps between the strong reflections (supplemental Table ST1). Analysis revealed that all these reflections belonged to a lamellar phase as the 1/d dependence on the order (h) was clearly linear (Fig. 2B). These reflections were assigned the orders IIIv, IVv, Vv…up to XXXv, and they provided a very long d = 15.9 nm. This d was three times longer than dSLP, and we denoted this lamellar phase as a very long lamellar phase (VLLP15.9, subscripts “v” in the order numbers mark the assignment to VLLP). The formation of VLLP15.9 instead of MLP in these membranes was most likely induced by the longer annealing at 70°C/H2O. The region of the short-range arrangement contained a weak reflection at the repeat distance of 0.41 nm and an insufficiently resolved reflection at the repeat distance of 0.37 nm.

Fig. 2.

Formation of the VLLP15.9 in SC model membranes. A: XRD pattern of the VLLP15.9 in the 1/0.03 sample [i.e., CerNS24/FFA(16–24)/Chol/CholS at the 1/1/1/0.03 molar ratio] in the region of long-range arrangement (left-hand side) and short-range arrangement (right-hand side). Roman numerals with the subscript ”v“ indicate the VLLP15.9 reflections; asterisks indicate separated Chol, and arrows indicate the reflections of orthorhombic chain packing. Full grid lines predict the position of VLLP15.9 reflections. The intensity in arbitrary units (a.u.) is shown on a logarithmic scale. B: A linear regression of the dependence of 1/d on the reflection order h.

Fig. 3.

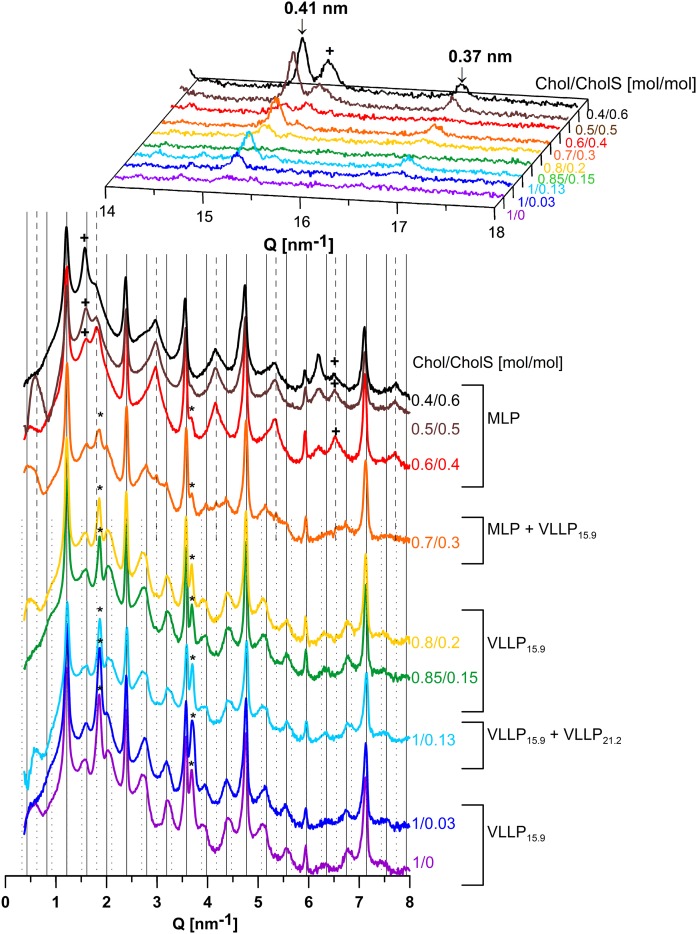

Polymorphism of the lipid membranes modeling the increased CholS-to-Chol ratio in RXLI disease, prepared by dropping and annealing at 70°C/H2O. XRD patterns of the CerNS24/FFA(16–24)/Chol/CholS samples with the molar ratio Chol/CholS = 1/0–0.4/0.6 in the region of long-range (bottom) and short-range (top) arrangements. Grid lines predict the position of VLLP15.9 reflections (solid), specific MLP reflections (dashed), and specific VLLP21.2 reflections (dotted); asterisks, plus symbols, and arrows indicate separated Chol, separated CholS, and reflections of orthorhombic chain packing, respectively. The intensities of different measurements are not scaled and are shown in arbitrary units. The intensities in the region of the long-range arrangement are shown on a logarithmic scale.

The XRD pattern of the 1/0.13 sample (i.e., with 5% CholS) formed VLLP15.9, which coexisted with another set of weak, regularly spaced reflections (Fig. 3, light blue line). The positions of these reflections (supplemental Table ST1) corresponded to another VLLP21.2 with d = 21.2 nm, which was four times longer than dSLP. The formation of VLLP21.2 was also confirmed in the 0.45/0 sample with reduced Chol after additional annealing at 70°C for 20 min (supplemental Fig. S2A, B). The VLLP21.2 together with VLLP15.9 was also detected in another control sample 1/0.13 prepared by spraying and annealing at 70°C/H2O for 30 min (supplemental Fig. S2C, D). Thus, the slow evaporation of the solvent seemed to be decisive for the formation of MLP, and the long (∼30 min) annealing in the presence of H2O controlled the formation of VLLP15.9 and VLLP21.2.

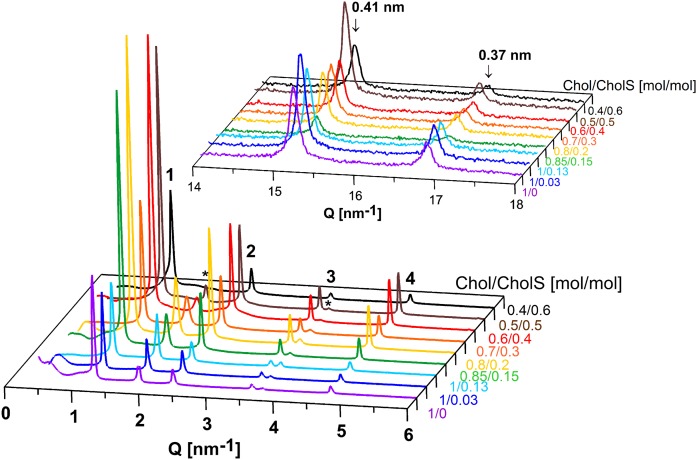

The Chol/CholS ratio modulates the polymorphism of SC lipid membranes

In the next experiment, an impairment of CholS-to-Chol processing in RXLI was simulated using the CerNS24/FFA(16–24)/Chol/CholS samples with increased CholS and reduced Chol content (the Chol/CholS molar ratios were varied from 0.85/0.15 to 0.4/0.6). The samples 1/0.03 and 1/0.13 (mimicking normal CholS levels in healthy SC), as well as 1/0 (without CholS), served as controls. All the samples prepared by spraying and annealing at 90°C formed SLP with d ∼ 5.3–5.4 nm with orthorhombic packing of polymethylene chains detected in the region of the short-range arrangement (Fig. 4). Separated Chol was also present, except in sample 0.4/0.6, i.e., that with Chol content reduced to 40%, which agrees with previous findings concerning the Chol miscibility with SC lipids (21). Even the significant CholS increment (from 0% to 60%) did not considerably change the lipid lamellar structure under these conditions. It has been previously reported that CholS improves the miscibility of Chol with other lipids in the fully hydrated SC model composed of isolated pig skin Cer/FFA/Chol/CholS at pH 7.4 and 5. Better Chol miscibility was apparent based on the disappearance of the first-order Chol reflection at the Chol/CholS molar ratio = 1:0.3 (38). If we solely examined the Chol/CholS molar ratio in our samples, we should expect the Chol reflection to disappear at the latest in sample 0.7/0.3, corresponding to 1 mol of Chol per 0.42 mol of CholS. However, disappearance of the Chol reflections was observed only in the membrane with the Chol/CholS molar ratio = 0.4/0.6. This phenomenon was caused by a low Chol fraction in the whole mixture rather than a high CholS fraction. The XRD patterns did not confirm an improved Chol miscibility with other SC lipids due to the higher CholS content. Different Cer species and different sample treatments and environments could explain the discrepancy between our findings and previously reported results (38).

Fig. 4.

SLP formed in lipid membranes modeling the increased CholS-to-Chol ratio in RXLI disease, prepared by spraying and annealing at 90°C. XRD patterns of the CerNS24/FFA(16–24)/Chol/CholS samples with the molar ratio Chol/CholS = 1/0–0.4/0.6 in the region of long-range (bottom) and short-range (top) arrangements. Arabic numerals indicate the reflections of SLP; asterisks indicate the separated Chol; arrows indicate the reflections of orthorhombic chain packing. The intensities of different measurements are not scaled and are shown in arbitrary units.

In contrast, the same lipid samples as in Fig. 4 prepared by dropping at 50°C and annealing at 70°C/H2O for 30 min formed MLP and VLLP, some with resolved reflections of the orthorhombic polymethylene chain packing (0.37 and 0.41 nm) (Fig. 3). The VLLP15.9 and separated Chol appeared in the XRD patterns of the samples with the Chol/CholS molar ratio in the range from 1/0 to 0.8/0.2. In the 1/0.13 sample (i.e., that mimicking the CholS content in deeper layers of healthy SC), both VLLP15.9 and VLLP21.2 were found, as mentioned above. At 10 weight%, CholS (the 0.7/0.3 sample), the VLLP15.9 coexisted with MLP and separated Chol. Further increases of the CholS level in the 0.6/0.4, 0.5/0.5, and 0.4/0.6 membranes resulted in the formation of MLP without any resolved signs of VLLP. Thus, a CholS content ≥ 14 weight% appears to suppress VLLP formation.

In the MLP-forming samples with high CholS content, additional reflections at Q = 1.57–1.59 and 6.19–6.20 nm−1 were observed. An examination of the short-range arrangement of the samples also revealed a peak at Q = 15.46 nm−1, the intensity of which increased with increasing CholS content. This feature could be observed in the low-CholS content samples, whereas it became clearly evident in the high-CholS content samples. Thus, the peaks at Q = 1.57–1.59, 6.19–6.20, and 15.46 nm−1 were assigned to the 1st-, 4th-, and 10th-order reflections, respectively, of separated crystalline CholS dihydrate with a spacing of 4.07 nm (39). This observation is corroborated by previous results, according to which a complete replacement of Chol by CholS in SC model membranes led to a phase-separation of CholS to provide d = 4.1 nm (40).

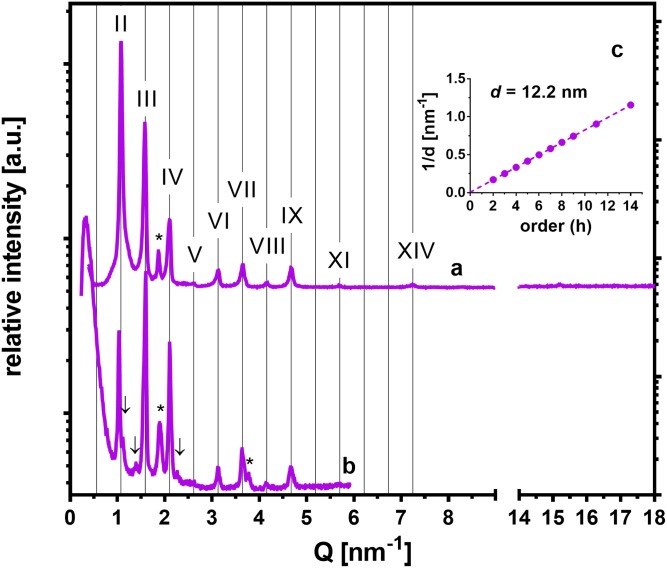

CerEOS abolishes the CerNS24-based membrane polymorphism

To probe the effects of an ω-O-acylCer, namely, CerEOS, on the abovementioned membrane polymorphism, we prepared the 0.45/0+EOS sample [i.e., CerEOS/CerNS/FFA(16–24)/Chol with the 0.3/0.7/1/0.45 molar ratio; Table 1]. A similar membrane has been reported to form long lamellar phases (LLPs) exclusively (41). Chol was reduced to 45% to prevent an overlap with the LLP reflections. The sample was prepared by dropping at 50°C and annealing once or twice at 70°C/H2O for 10 min or 10 and 20 min, respectively. In the XRD patterns of this sample (Fig. 5), we detected reflections of the orders II, III, IV… up to XIV, providing LLP with d = 12.2 nm after the first (supplemental Table ST1) and second annealing. There was only a small indication that an additional structure, most likely VLLP, formed after the second annealing (Fig. 5B). Weak reflections of separated Chol, and very weak reflections of the orthorhombic polymethylene chain packing (unresolvable in Fig. 5A) were also found.

Fig. 5.

The effect of CerEOS on the structure of SC model membranes. XRD patterns of the sample 0.45/0 + EOS with the molar ratio CerEOS/CerNS24/FFA(16–24)/Chol/CholS = 0.3/0.7/1/0.45/0 after the first annealing (A) and after the second annealing (B) in the region of long-range arrangement (left-hand side) and short-range arrangement (right-hand side). Roman numerals indicate the reflections of LLP, asterisks indicate separated Chol, and arrows indicate weak additional reflections, which most likely belong to a VLLP. The intensities of different measurements are not scaled and are shown in arbitrary units (a.u.). C: A linear regression of the dependence of 1/d on the reflection order h for LLP .

DISCUSSION

The XRD and electron-microscopy results have provided essential information about the SC lipid barrier structure, i.e., that the dominant repeating unit is ∼13 nm long (14, 15, 42) and contains repeating patterns of broad/narrow/broad electron-lucent bands bordered by electron-dense segments (25). A recent study using cryo-electron microscopy of vitreous skin sections without staining showed a different pattern, consisting of narrow (4.5 nm) and broad (6.5 nm) lucent bands, together revealing an asymmetric repeating unit of 11 nm (10–12 nm) (26).

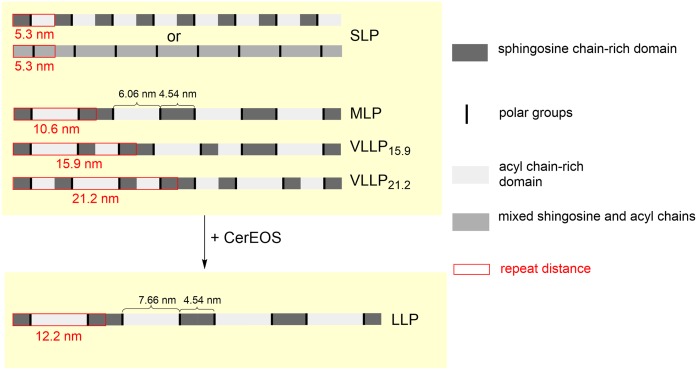

Until recently, ω-O-acylCers were thought to be essential for the formation of lamellar lipid phases with long d, as only complex model membranes containing ω-O-acylCer formed a long periodicity phase with d ∼ 13 nm along with other phases (18, 43). Here, we report, for the first time, that CerNS24-based model membranes in the absence of ω-O-acylCer form not only the SLP but also MLP and VLLP and that their lamellae can be arranged with even longer repeat distances than in membranes with ω-O-acylCer. The formation of MLP has recently also been observed in model lipid systems based on CerNH (44) or the CerNH/CerNS mixture (45). These models were prepared by spraying and annealing at 90°C. Thus, there might be an intrinsic susceptibility of various Cer species to form MLP under specific conditions.

MLP and VLLP can macroscopically coexist with a certain fraction of SLP [e.g., coexistence of MLP (d = 10.6 nm) and SLP (d = 5.3 nm)], and they are indistinguishable in XRD patterns due to an overlap of their reflections. The phase separation on a macroscopic scale can be recognized in the diffraction patterns only in the cases of incommensurate phases (e.g., MLP and VLLP15.9, VLLP15.9, and VLLP21.2 in Fig. 3). On a microscopic scale, however, the coexistence may also conform to a different scenario, in which the shorter phase would serve as a base unit for all the longer phases (i.e., MLP = 2×SLP, VLLP15.9=3×SLP, and VLLP21.2=4×SLP). We suggest a possible simplified arrangement of the lamellar phases in the CerNS24-based model (Fig. 6) based on the following: the length of the fully extended (splayed-chain) CerNS24 molecule is very close to dSLP = 5.3 nm (26). The extended conformation of CerNS24 in SC lipid model membranes has been indicated previously (46). Furthermore, the average length of lipid chains is known to affect the resulting d of lamellar phases in SC model membranes (22).

Fig. 6.

The proposed simplified models of the repeating units of the CerNS24-based and CerEOS/CerNS24-based SC model membranes.

The single base unit is most likely asymmetric with acyl chain-rich and sphingosine chain-rich domains. In SLP, the base unit with d = 5.3 nm can be repeated with translational symmetry, but the resulting structure would not be centrosymmetric. The sphingosine chains would point in the same direction in all the repeating units. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that SLP could be based on a different molecular arrangement than the other longer phases, with acyl and sphingosine chains mixed in the same domain. Such a symmetric unit could be repeated with translational symmetry and creates a centrosymmetric structure (Fig. 6).

The MLP can be constructed from the asymmetric base units arranged alternately so that sphingosine chains of two adjacent layers point to each other. In artificial asymmetric lipid bilayers, asymmetry in the region of polar headgroups as well as of polymethylene chains became evident due to weak reflections attributed to odd-numbered orders in the XRD patterns (37). A similar pattern was evident in the XRD of the MLP described herein. The ever-present base unit would be one of the reasons for the large diffraction intensities recorded at positions h ×1/5.3 nm.

In the MLP, the asymmetry inheres in regions rich in acyl chains (24C; approximate length of the fully stretched chain is 3.1 nm) and sphingosine chains (18C; 2.3 nm). If we divide the dSLP = 5.3 nm according to the ratio of 24:18, we obtain 3.03 and 2.27 nm fractions. Thus, the sphingosine chain domain in the MLP would have a width of 4.54 nm and the acyl chain domain a width of 6.06 nm. The 4.54 nm width of the supposed sphingosine domain agrees well with a width of the narrow electron-lucent band (4.5 nm) reported in SC micrographs (26). The broad electron-lucent band in the SC micrographs was 6.5 nm wide, which is 0.44 nm longer than the calculations based on our XRD data. If we subtract the width of the sphingosine domain (4.54 nm) from the LLP (d = 12.2 nm) in the membrane with CerEOS, we obtain a length of 7.66 nm, which is more than 1 nm larger than the broad lucent band in the SC micrographs reported by Iwai et al. (26). However, the CerEOS fraction in our model was increased to 30 mol% (of total Cer pool) because this composition ensures LLP formation without other lamellar phases. The physiological content of ω-O-acylCer is approximately 10 mol% of the total Cer fraction (47). Thus, if we assume a linear relationship between the average lipid chain length and d, we can interpolate the theoretical widths in the membrane with 10% of ω-O-acylCer: the acyl chain domain of 6.59 nm and d = 11.13 nm. Such widths would be in excellent agreement with the micrographs and the model proposed in Ref. 26. Our CerNS24-based model also formed VLLP with d values three or four times larger than dSLP. The putative arrangements of those units were derived from the existence of an asymmetric base unit and require regular assembly of the lipid sheets on a large scale.

This membrane polymorphism was significantly affected by the CholS concentration in the RXLI model when annealed at 70°C/H2O. The increasing CholS/Chol ratio changed the propensity of the lipid mixture to self-organize into VLLP; at 14–20 weight% CholS, the lipids created MLP instead of VLLP. The mechanism of the CholS effect on the SC model polymorphism is unknown and requires further studies. In addition, CholS separation was already detected at 7 weight% CholS and became more pronounced at 14 weight% CholS. These abilities of increased CholS concentrations to modulate the SC lipid architecture and to phase separate appear to be consistent with the altered organization of the SC barrier in RXLI patients (31, 32). CholS applied topically onto the isolated murine SC caused extensive nonlamellar domain formation and disruption of the lamellar membrane structure (31). Lamellar-phase separation was also detected in RXLI patients (32). The phase separation of CholS in our model could be relevant to the nonlamellar domains and phase separation in the skin, which is attributed to the skin barrier abnormality. However, the pathophysiology of RXLI patient skin is more complex, comprising the inhibition of serine proteases by CholS and, consequently, diminished degradation of the corneodesmosomes that bind corneocytes, leading to abnormal desquamation (48). Furthermore, CholS acts as an acidifier of the SC interstices in RXLI patients relative to the pH in healthy individuals (49). Increased Ca2+ levels in the SC of RXLI patients also contribute to corneocyte retention by increasing corneodesmosome and interlamellar cohesion (32). Although our model simulated some important properties of the SC lipid barrier (it contained the main SC lipid classes at a proper molar ratio and attained the lamellar characteristic of the lipid matrix), we are aware of the model limitations. For example, the formation of extracellular lipid domains in the epidermal differentiation concurs with the cornification of granular cells to corneocytes and formation of the corneocyte lipid envelope. The corneocyte lipid envelope is an external membrane monolayer of lipids that is covalently bound to corneocytes and serves as a template for the orientation of SC lipids (50, 51). It would be interesting to study the templating function of the corneocyte lipid envelope on the formation of the lamellar phases described herein in healthy and RXLI models. However, no in vitro membrane models are currently available that would include corneocytes with a cornified envelope and corneocyte lipid envelope.

An interesting aspect of the SC model membranes was the occurrence of peaks in the region of short-range arrangement, indicating an orthorhombic packing of the polymethylene chains. These peaks with spacings of 0.41 and 0.37 nm were resolved when the samples were applied by spraying and annealing at 90°C in the absence of H2O. The other preparation and annealing methods led to obviously lower relative intensity peaks of 0.41 and 0.37 nm or their complete disappearance. We do not have an explanation for this effect, and thus it will be further assessed in our future studies.

Our results suggest that CerEOS (and possibly also other ω-O-acylCer) suppresses lipid arrangements other than LLP in a CerNS24-based model. The elongated acyl chains with ester-linked linoleic acid in CerEOS likely act as a molecular rivet, literally sticking together the opposing lipid sheets and reinforcing the LLP structure. Such cross-linking can contribute to the barrier function by hampering the diffusion of molecules along lipid layers, as indicated by Ref. 41. We consider this feature of the CerEOS-containing membrane to be a key point in understanding the fundamental properties of Cer-based lipid systems and the involvement of ω-O-acylCer therein.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- Cer

- ceramide

- CerEOS

- N-(32-linoleyloxy)dotriacontanoyl-d-erythro-sphingosine

- CerNS24

- N-tetracosanoyl-d-erythro-sphingosine

- Chol

- cholesterol

- CholS

- sodium cholesteryl sulfate

- ω-O-acylCer

- ceramides having 30–34C acyl chains with a linoleic acid ester linked to an ω-hydroxyl

- FFA(16–24)

- mixture of free fatty acids with 16, 18, 20, 22, and 24 carbons

- LLP

- long lamellar phase

- MLP

- medium lamellar phase

- RXLI

- recessive X-linked ichthyosis

- SC

- stratum corneum

- SLP

- short lamellar phase

- VLLP

- very long lamellar phase

- XRD

- X-ray diffraction

- ω-O-acylceramide

- ω-O-acylCer

This work was supported by the project Efficiency and Safety Improvement of Current Drugs and Nutraceuticals: Advanced Methods-New Challenges (CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000841), co-funded by European Regional Development Fund, Grantová Agentura České Republiky Grant 19-09135J, and a Grant of the Representative of the Czech Republic in the Committee of Plenipotentiaries of the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) within JINR Topical Theme 04-4-1121-2015/2020.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matsui T., and Amagai M.. 2015. Dissecting the formation, structure and barrier function of the stratum corneum. Int. Immunol. 27: 269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wertz P. W. 2004. Stratum corneum lipids and water. Exogenous Dermatol. 3: 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elias P. M. 1981. Epidermal lipids, membranes, and keratinization. Int. J. Dermatol. 20: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams M. L., and Elias P. M.. 1981. Stratum corneum lipids in disorders of cornification: increased cholesterol sulfate content of stratum corneum in recessive x-linked ichthyosis. J. Clin. Invest. 68: 1404–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masukawa Y., Narita H., Shimizu E., Kondo N., Sugai Y., Oba T., Homma R., Ishikawa J., Takagi Y., Kitahara T., et al. 2008. Characterization of overall ceramide species in human stratum corneum. J. Lipid Res. 49: 1466–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robson K. J., Stewart M. E., Michelsen S., Lazo N. D., and Downing D. T.. 1994. 6-Hydroxy-4-sphingenine in human epidermal ceramides. J. Lipid Res. 35: 2060–2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.t’Kindt, R., L. Jorge, E. Dumont, P. Couturon, F. David, P. Sandra, and K. Sandra. 2012. Profiling and characterizing skin ceramides using reversed-phase liquid chromatography–quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 84: 403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabionet M., Bayerle A., Marsching C., Jennemann R., Gröne H-J., Yildiz Y., Wachten D., Shaw W., Shayman J. A., and Sandhoff R.. 2013. 1-O-acylceramides are natural components of human and mouse epidermis. J. Lipid Res. 54: 3312–3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Smeden J., Boiten W. A., Hankemeier T., Rissmann R., Bouwstra J. A., and Vreeken R. J.. 2014. Combined LC/MS-platform for analysis of all major stratum corneum lipids, and the profiling of skin substitutes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1841: 70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabionet M., Gorgas K., and Sandhoff R.. 2014. Ceramide synthesis in the epidermis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1841: 422–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elias P. M., and Friend D. S.. 1975. The permeability barrier in mammalian epidermis. J. Cell Biol. 65: 180–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hou S. Y. E., Mitra A. K., White S. H., Menon G. K., Ghadially R., and Elias P. M.. 1991. Membrane structures in normal and essential fatty acid-deficient stratum corneum: characterization by ruthenium tetroxide staining and X-ray diffraction. J. Invest. Dermatol. 96: 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elias P. M., and Menon G. K.. 1991. Structural and lipid biochemical correlates of the epidermal permeability barrier. Adv. Lipid Res. 24: 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouwstra J. A., Gooris G. S., van der Spek J. A., and Bras W.. 1991. Structural investigations of human stratum corneum by small-angle X-ray scattering. J. Invest. Dermatol. 97: 1005–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White S. H., Mirejovsky D., and King G. I.. 1988. Structure of lamellar lipid domains and corneocyte envelopes of murine stratum corneum. An X-ray diffraction study. Biochemistry. 27: 3725–3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McIntosh T. J., Stewart M. E., and Downing D. T.. 1996. X-ray diffraction analysis of isolated skin lipids: reconstitution of intercellular lipid domains. Biochemistry. 35: 3649–3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouwstra J. A., Gooris G. S., Cheng K., Weerheim A., Bras W., and Ponec M.. 1996. Phase behavior of isolated skin lipids. J. Lipid Res. 37: 999–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouwstra J. A., Gooris G. S., Dubbelaar F. E. R., Weerheim A. M., IJzerman A. P., and Ponec M.. 1998. Role of ceramide 1 in the molecular organization of the stratum corneum lipids. J. Lipid Res. 39: 186–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Jager M. W., Gooris G. S., Dolbnya I. P., Bras W., Ponec M., and Bouwstra J. A.. 2003. The phase behaviour of skin lipid mixtures based on synthetic ceramides. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 124: 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouwstra J. A., Gooris G. S., Vries M. A. S., van der Spek J. A., and Bras W.. 1992. Structure of human stratum corneum as a function of temperature and hydration: a wide-angle X-ray diffraction study. Int. J. Pharm. 84: 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sochorová M., Audrlická P., Červená M., Kováčik A., Kopečná M., Opálka L., Pullmannová P., and Vávrová K.. 2019. Permeability and microstructure of cholesterol-depleted skin lipid membranes and human stratum corneum. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 535: 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Školová B., Janůšová B., Zbytovská J., Gooris G., Bouwstra J., Slepička P., Berka P., Roh J., Palát K., Hrabálek A., et al. 2013. Ceramides in the skin lipid membranes: length matters. Langmuir. 29: 15624–15633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreiner V., Gooris G. S., Pfeiffer S., Lanzendörfer G., Wenck H., Diembeck W., Proksch E., and Bouwstra J.. 2000. Barrier characteristics of different human skin types investigated with X-ray diffraction, lipid analysis, and electron microscopy imaging. J. Invest. Dermatol. 114: 654–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssens M., van Smeden J., Gooris G. S., Bras W., Portale G., Caspers P. J., Vreeken R. J., Kezic S., Lavrijsen A. P. M., and Bouwstra J. A.. 2011. Lamellar lipid organization and ceramide composition in the stratum corneum of patients with atopic eczema. J. Invest. Dermatol. 131: 2136–2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swartzendruber D. C., Wertz P. W., Kitko D. J., Madison K. C., and Downing D. T.. 1989. Molecular models of the intercellular lipid lamellae in mammalian stratum corneum. J. Invest. Dermatol. 92: 251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwai I., Han H., den Hollander L., Svensson S., Öfverstedt L-G., Anwar J., Brewer J., Bloksgaard M., Laloeuf A., Nosek D., et al. 2012. The human skin barrier is organized as stacked bilayers of fully extended ceramides with cholesterol molecules associated with the ceramide sphingoid moiety. J. Invest. Dermatol. 132: 2215–2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mojumdar E. H., Gooris G. S., Groen D., Barlow D. J., Lawrence M. J., Demé B., and Bouwstra J. A.. 2016. Stratum corneum lipid matrix: location of acyl ceramide and cholesterol in the unit cell of the long periodicity phase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1858: 1926–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lundborg M., Narangifard A., Wennberg C. L., Lindahl E., Daneholt B., and Norlén L.. 2018. Human skin barrier structure and function analyzed by cryo-EM and molecular dynamics simulation. J. Struct. Biol. 203: 149–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elias P. M., Williams M. L., Maloney M. E., Bonifas J. A., Brown B. E., Grayson S., and Epstein E. H.. 1984. Stratum corneum lipids in disorders of cornification. Steroid sulfatase and cholesterol sulfate in normal desquamation and the pathogenesis of recessive X-linked ichthyosis. J. Clin. Invest. 74: 1414–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ranasinghe A. W., Wertz P. W., Downing D. T., and Mackenzie I. C.. 1986. Lipid composition of cohesive and desquamated corneocytes from mouse ear skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 86: 187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zettersten E., Man M-Q., Farrell A., Ghadially R., Williams M. L., Feingold K. R., Elias P. M., Sato J., and Denda M.. 1998. Recessive x-linked ichthyosis: role of cholesterol-sulfate accumulation in the barrier abnormality. J. Invest. Dermatol. 111: 784–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elias P. M., Crumrine D., Rassner U., Hachem J-P., Menon G. K., Man W., Wun C., Leypoldt L., Feingold K. R., and Williams M. L.. 2004. Basis for abnormal desquamation and permeability barrier dysfunction in RXLI. J. Invest. Dermatol. 122: 314–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groen D., Poole D. S., Gooris G. S., and Bouwstra J. A.. 2011. Investigating the barrier function of skin lipid models with varying compositions. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 79: 334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rehfeld S. J., Plachy W. Z., Williams M. L., and Elias P. M.. 1988. Calorimetric and electron spin resonance examination of lipid phase transitions in human stratum corneum: molecular basis for normal cohesion and abnormal desquamation in recessive X-linked ichthyosis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 91: 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Opálka L., Kováčik A., Sochorová M., Roh J., Kuneš J., Lenčo J., and Vávrová K.. 2015. Scalable synthesis of human ultralong chain ceramides. Org. Lett. 17: 5456–5459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groen D., Gooris G. S., and Bouwstra J. A.. 2010. Model membranes prepared with ceramide EOS, cholesterol and free fatty acids form a unique lamellar phase. Langmuir. 26: 4168–4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McIntosh T. J., Waldbillig R. C., and Robertson J. D.. 1977. The molecular organization of asymmetric lipid bilayers and lipid-peptide complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 466: 209–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouwstra J. A., Gooris G. S., Dubbelaar F. E. R., and Ponec M.. 1999. Cholesterol sulfate and calcium affect stratum corneum lipid organization over a wide temperature range. J. Lipid Res. 40: 2303–2312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abrahamsson J., Abrahamsson S., Hellqvist B., Larsson K., Pascher I., and Sundell S.. 1977. Cholesteryl sulphate and phosphate in the solid state and in aqueous systems. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 19: 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McIntosh T. J. 2003. Organization of skin stratum corneum extracellular lamellae: diffraction Evidence for asymmetric distribution of cholesterol. Biophys. J. 85: 1675–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Opálka L., Kováčik A., Maixner J., and Vávrová K.. 2016. Omega-O-acylceramides in skin lipid membranes: effects of concentration, sphingoid base, and model complexity on microstructure and permeability. Langmuir. 32: 12894–12904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madison K. C., Swartzendruber D. C., Wertz P. W., and Downing D. T.. 1987. Presence of intact intercellular lipid lamellae in the upper layers of the stratum corneum. J. Invest. Dermatol. 88: 714–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Jager M. W., Gooris G. S., Dolbnya I. P., Bras W., Ponec M., and Bouwstra J. A.. 2004. Novel lipid mixtures based on synthetic ceramides reproduce the unique stratum corneum lipid organization. J. Lipid Res. 45: 923–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kováčik A., Šilarová M., Pullmannová P., Maixner J., and Vávrová K.. 2017. Effects of 6-hydroxyceramides on the thermotropic phase behavior and permeability of model skin lipid membranes. Langmuir. 33: 2890–2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kováčik A., Vogel A., Adler J., Pullmannová P., Vávrová K., and Huster D.. 2018. Probing the role of ceramide hydroxylation in skin barrier lipid models by 2H solid-state NMR spectroscopy and X-ray powder diffraction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1860: 1162–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Školová B., Hudská K., Pullmannová P., Kováčik A., Palát K., Roh J., Fleddermann J., Estrela-Lopis I., and Vávrová K.. 2014. Different phase behavior and packing of ceramides with long (C16) and very long (C24) acyls in model membranes: infrared spectroscopy using deuterated lipids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 118: 10460–10470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masukawa Y., Narita H., Sato H., Naoe A., Kondo N., Sugai Y., Oba T., Homma R., Ishikawa J., Takagi Y., et al. 2009. Comprehensive quantification of ceramide species in human stratum corneum. J. Lipid Res. 50: 1708–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elias P. M., Williams M. L., Choi E-H., and Feingold K. R.. 2014. Role of cholesterol sulfate in epidermal structure and function: Lessons from X-linked ichthyosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1841: 353–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Öhman H., and Vahlquist A.. 1998. The pH gradient over the stratum corneum differs in X-linked recessive and autosomal dominant ichthyosis: a clue to the molecular origin of the “acid skin mantle”? J. Invest. Dermatol. 111: 674–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elias P. M., Gruber R., Crumrine D., Menon G., Williams M. L., Wakefield J. S., Holleran W. M., and Uchida Y.. 2014. Formation and functions of the corneocyte lipid envelope (CLE). Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1841: 314–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wertz P. W., and van den Bergh B.. 1998. The physical, chemical and functional properties of lipids in the skin and other biological barriers. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 91: 85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.