Abstract

Cerebral edema in ischemic stroke can lead to increased intracranial pressure, reduced cerebral blood flow and neuronal death. Unfortunately, current therapies for cerebral edema are either ineffective or highly invasive. During the development of cytotoxic and subsequent ionic cerebral edema water enters the brain by moving across an intact blood brain barrier and through aquaporin-4 (AQP4) at astrocyte endfeet. Using AQP4-expressing cells, we screened small molecule libraries for inhibitors that reduce AQP4-mediated water permeability. Additional functional assays were used to validate AQP4 inhibition and identified a promising structural series for medicinal chemistry. These efforts improved potency and revealed a compound we designated AER-270, N-[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-5-chloro-2-hydroxybenzamide. AER-270 and a prodrug with enhanced solubility, AER-271 2-{[3,5-Bis(trifluoromethyl) phenyl]carbamoyl}−4-chlorophenyl dihydrogen phosphate, improved neurological outcome and reduced swelling in two models of CNS injury complicated by cerebral edema: water intoxication and ischemic stroke modeled by middle cerebral artery occlusion.

Keywords: AQP4 inhibitor, High Throughput Screen, cytotoxic edema, ionic edema, cerebral edema, ischemic stroke, MCAo, water intoxication

INTRODUCTION

Many therapies have been studied for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke, but few have been approved by regulatory agencies (O’Collins et al., 2006). Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) has seen restricted use due to the risk of hemorrhagic conversion (Wang et al., 2004) and a relatively short therapeutic window. Mannitol is typically used to temporarily reduce intracranial pressure (ICP) as patients are prepared for decompressive craniectomy (Wijdicks et al., 2014). This procedure can largely ameliorate the effects of ICP, but it does nothing to reduce or prevent cerebral edema (CE), the underlying cause of ICP, and its utility in the clinic is limited to patients under the age of sixty (Arac et al., 2009). More recently, endovascular thrombectomy for clot removal has shown encouraging results (Berkhemer et al., 2015; Goyal et al., 2015), but, similar to tPA, early intervention is necessary for optimal utility and the effects of subsequent reperfusion can be detrimental in more severe cases of acute ischemic stroke (Sanak et al., 2006; Yoo et al., 2009; Mlynash et al., 2011). Effective therapies to treat cerebral edema in stroke remain a high unmet medical need.

An ischemic stroke is initiated by a vascular obstruction or stenosis that causes hypoxia in the surrounding tissue. Initially anaerobic metabolism results in the accumulation of lactate and inorganic phosphate forming a significant osmotic imbalance, increasing osmolarity by 50–80 mOsm (Hossmann et al., 1982; LaManna 1996). Cation influx through ion channels like the sulfonylurea receptor 1-regulated transient receptor potential melastatin 4 (TRPM4) subsequently contribute to a building osmotic imbalance (Simard et al., 2013). Water follows the osmotic gradient through an intact blood-brain barrier (BBB) resulting in cytotoxic cerebral edema. CE is subsequently enhanced with the restoration of blood flow to the affected area giving larger osmotic gradients between blood and brain tissue resulting in ionic cerebral edema (Young et al., 1987; Stokum et al., 2015). If left unchecked, CE will lead to an increase in ICP that reduces cerebral perfusion and exacerbates the damage caused by the initial ischemic injury (Marmarou 2007; Bardutzky and Schwab 2007).

Central to the development of cerebral and spinal-cord edema is the bi-directional water channel aquaporin-4 (AQP4), found at unprecedented levels—35% of total membrane surface area—in the portion of the astrocytic endfeet that face blood vessels at the BBB (Amiry-Moghaddam et al., 2004; Anders and Brightman 1979; Rash et al., 1998; Papadopoulos and Verkman 2013). In mice, deletion of the AQP4 gene reduces water permeability of astrocytes (Manley et al., 2000; Solenov et al., 2004) without gross phenotypic changes under normal physiological conditions (Ma et al., 1997). Quite remarkably, these AQP4-null mice show substantially improved outcomes and survivability over their wild-type counterparts in four models of CNS injury: ischemic stroke (Manley et al., 2000; Yao et al., 2015A; Hirt et al., 2017), water intoxication (Manley et al., 2000), bacterial meningitis (Papadopoulos and Verkman 2005), and spinal-cord compression (Saadoun et al., 2008). AQP4-null mice have also shown reduced CE and BBB permeability in a model of severe hypoglycemia (Zhao et al., 2018). These studies represent a genetic proof-of-principle highlighting the central role of AQP4 in the formation of cerebral edema and its potential as a target for an anti-edema strategy aimed at stroke therapy.

Multiple attempts have been made to identify AQP4 inhibitors, but no inhibitor has gained widespread use. Various drugs have been tested including: arylsulfonamides (Huber et al., 2007), anti-epileptics (Huber et al., 2009A), loop diuretics (Migliati et al., 2009) and a selection of other known drugs (Huber et al., 2009B). In these studies, inhibition of AQP4 expressed in Xenopus oocytes gave IC50s in the high micromolar range, but these and other compounds showed no inhibition upon retesting in mammalian cell cultures expressing AQP4 (Yang et al., 2008; Tradtrantip et al., 2017). After many years of searching, the development of an effective aquaporin inhibitor remains a challenging goal (Verkman et al., 2014).

Here, we report the development of a new class of AQP4 inhibitors, discovered through cell-based high-throughput screening. Medicinal chemistry was used to identify a lead compound with improved potency (designated AER-270) and a prodrug (designated AER-271) was synthesized to increase solubility. These compounds were effective at reducing cerebral edema and improving neurological outcomes in two distinct models of CNS injury.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

CHO cell lines

Stable, isogenic Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell-lines expressing human AQP1, AQP2, AQP4-M1, AQP4-M23 (an alternative translation start site lacking 22 N-terminal amino acids), AQP5 or CD81 were generated using the Flp-In™ system according to the manufacturers recommendations (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Protein expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis using an N-terminal FLAG tag and relative water permeabilities assessed by video microscopy (data not shown).

High-throughput screen

AQP4-M23 (AQP4) and CD81 expressing CHO cells were seeded in 384-well tissue culture-treated plates using 10 μl Ham’s F12 medium per well supplemented to 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% pen/strep (10,000 U/ml) and 500 μg/ml hygromycin B and grown to 95% confluence at 37°C. 161,000 compounds were transferred in 10 nl aliquots (10–20 mM in DMSO) from chemical library plates to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were challenged with a hypoosmotic shock by replacing the media with 40 μl deionized water for 5.5 min at 37°C. Osmotic shock was terminated by adding 40 μl of 2x concentrated PBS containing 10 μM calcein-AM as a fluorescent marker for cell viability. After 30 min at 37°C, fluorescence (495Ex/515Em) was quantitated using a multiplate reader (Biotek Instruments, Inc., Burlington, VT, USA). Libraries screened: MicroSource GenPlus 960 (Microsource Discovery Systems, Inc., Gaylordsville, CT, USA), Maybridge Diversity Set 20,000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 140,000 compounds selected from ChemBridge Corp. (San Diego, CA, USA) libraries DIVERSet, MicroFormat and MW-Set. Various derivatives of AER-37 and AER-270, as well as prodrugs of AER-270 (Tables 1 and 2), were synthesized by Zamboni Chemistry Solutions (Montreal, Canada).

Table 1.

Structure of selected phenylbenzamides.

|

AER-3 |

|

AER-7 |

|

AER-22 |

|

AER-37 |

|

AER-270 |

|

AER-271 |

Table 2.

Structure activity relationship analysis of AER-37 by inhibition of AQP4-mediated water permeability, light scattering assay.

| Compound | Compound Structure | Percent AQP4 Inhibition | Compound | Compound Structure | Percent AQP4 Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AER-37 |  |

53.0 | AER-506 |  |

3.1 |

| AER-22 |  |

55.6 | AER-507 |  |

2.4 |

| AER-253 |  |

0 | AER-508 |  |

0 |

| AER-270 |  |

47.0 | AER-510 |  |

0 |

| AER-311 |  |

3.9 | AER-511 |  |

5.2 |

| AER-460 |  |

50.5 | AER-517 |  |

21.0 |

| AER-461 |  |

4.4 | AER-518 |  |

25.2 |

| AER-464 |  |

3.3 | AER-524 |  |

50.6 |

| AER-487 |  |

46.6 | AER-531 |  |

17.3 |

| AER-505 |  |

33.6 | AER-533 |  |

49.1 |

Video Microscopy

AQP4 and CD81 expressing CHO cells were seeded at ~5% confluence and grown for 24 hours in 6-well tissue culture plates. Cells were treated for 30 min in Ham’s F12 (as described above) supplemented to 0.1% DMSO (Vehicle) or 10 μM test compound/0.1% DMSO. Media was aspirated, replaced with 500 μl deionized water and swelling recorded using a light microscope at 100x magnification. Video files were analyzed at one frame per second using ImageJ 1.37 (Schneider et al., 2012), measuring relative diameter (D/D0) at the cells widest cross section. Data fit to equation 1: D/Do = 1 + Dm*(1 - exp(−k1*t)); where D cell diameter, Do initial cell diameter, Dm maximal change in cell diameter, k1 rate of cell diameter increase and t time. Percent Inhibition for this assay and others was calculated using equation 2: ((kAQP4,Vehicle – kCD81,Vehicle) – (kAQP4,Drug – kCD81,Vehicle) / (kAQP4,Vehicle – kCD81,Vehicle)) * 100%; where kAQP4,Drug, kAQP4,Vehicle and kCD81,Vehicle are initial rates of change for AQP4 cells with and without test compound and CD81 cells without test compound, respectively. Note: the initial rates for CD81 cells, with and without test article, in this and subsequent assays showed little difference, ~5–10% variation.

Cell Volume Cytometry

CHO cells expressing AQP4 or CD81 were grown on glass coverslips (90–95% confluent) and treated with Vehicle or 10 μM test compound in Ham’s F12 media as described above. Coverslips were placed cell-side down onto a microfluidics chamber and HBSS (prepared at 100 mOsm and adjusted to 300 mOsm with mannitol to maintain uniform conductivity) applied through a microfluidics system (Cell Volume Cytometer, CVC-7000, Volnamics, LLC, Buffalo, NY, USA). A hypoosmotic shock from 300 to 100 mOsm was introduced using HBSS at 100 mOsm. Swelling was monitored by comparing Initial Resistance (Ro) to Resistance (R) observed at subsequent time points.

Light Scattering Assay

Light scattering by a confluent monolayer of CHO cells was monitored using absorbance at 600 nm in a 96-well plate with a multiplate reader. Cells were treated with either Vehicle or 10 μM test compound in 40 ul isosmotic DMEM/F12 media supplemented to 15 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and FBS, pen/strep and hygromycin B (as above) for 30 min at 37°C. In Fig. 2C, a hyperosmotic shock was induced by adding 40 μL of 530 mOsm HBSS (high osmolarity achieved by the addition of mannitol) for a final osmolarity of 415 mOsm. CD81 cell data fit to equation 3: A = Ao + Ad*(1 - exp(−k1*t)); where A is absorbance, k1 rate of absorbance increase, Ao initial absorbance and Ad maximal change in absorbance. Data from AQP4 cells showing two phases were fit to equation 4: A = Ao*exp(−k2*t) – Ad*exp(−k1*t); defined above with k2 rate of absorbance decrease. Each curve represents an average of data from multiple wells as indicated in the figure captions. Percent Inhibition was calculated using equation 2 and the initial rise in absorbance observed with hyperosmotic shock.

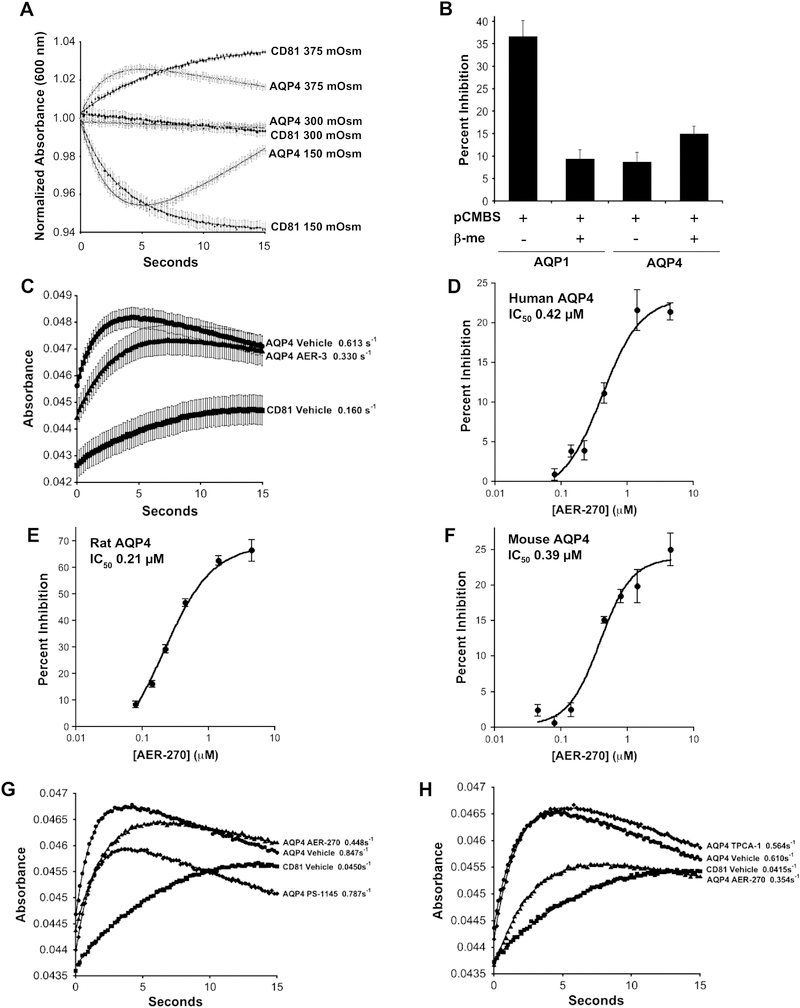

Fig. 2.

Light scattering detects water movement in CHO cells expressing aquaporins providing an efficient assay for detecting aquaporin inhibitors. (A) AQP4 expressing CHO cells, grown as a confluent monolayer on 96-well plates, give predictable changes in light scattering in response to osmotic stress. AQP4 and CD81 expressing CHO cells were exposed to either hyperosmotic (375 mOSM), isosmotic or hypoosmotic (150 mOSM) conditions by the addition of an equal volume of HBSS adjusted to 450 mOSM using mannitol, unadjusted HBSS or water, respectively. Light scattering detected by change in absorbance at 600 nm. Mean of normalized values plotted versus time ± SEM (n=16 wells). (B) Inhibition of AQP1 but not AQP4 by mercury demonstrates utility of light scattering method for detecting inhibitors of aquaporin-based water movement. AQP1 (mercury sensitive), AQP4 (mercury insensitive) and CD81 expressing CHO cells were incubated in HBSS containing 0.3 mM p-chloromercuribenzenesulfonic acid (pCMBS) for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were subsequently incubated for 30 min in fresh HBSS with or without 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (β-me). Changes in water permeability were then determined using Percent Inhibition calculated from light scattering data after a hyperosmotic shock, 300 to 415 mOsm, as describe in Experimental Procedures. Mean Percent Inhibition displayed ± SEM (n=8 wells). (C) Light scattering detects inhibition of AQP4-mediated water permeability by early hit AER-3. Cells were exposed to a hyperosmotic shock. Mean absorbance plotted at the indicated times ± SEM (n=8 wells). Rate constants for the rise in the curves are shown. (D-F) Lead compound AER-270 inhibits AQP4 from human, rat and mouse with similar potency. Using CHO cells expressing AQP4-M23 (AQP4) derived from human, rat (Rattus norvegicus) and mouse (Mus musculus) the IC50s of AER-270 were investigated using the light scattering assay as described in (C) above. Mean Percent Inhibition ± SEM (n=8 wells). (G-H) Kinase inhibitors selective for IKK-β do not affect AQP4-mediated water permeability. The effects of IKK-β inhibitors on AQP4-based water permeability were investigated using the light scattering assay. As a positive control 10 μM AER-270 and a Vehicle control were used to confirm AQP4 inhibition. (G) 5 μM PS-1145 and (H) 10 μM TPCA-1. Mean absorbance plotted at the indicated times ± SEM (n=8 wells).

Animals

Male mice (C57BL/6J, 8–12 week-old, 25–30g) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Male rats (Sprague Dawley strain 400, 7–8 week-old, 250–300g) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA, USA). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Case Western Reserve University approved these studies. All experiments were performed according to the relevant guidelines and regulations in the United States National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Water Intoxication

Sterile deionized water was prepared for injection with either 0.1% DMSO (Vehicle) or a dose of 0.8 mg/kg AER-270/0.1% DMSO (AER-270) in a volume equal to 20% body weight. This dose of AER-270 represents the maximum possible dose, given the poor solubility of AER-270 (4 μg/mL) in aqueous solution at pH 7. Mice were injected intraperitoneal (IP) then observed for 4 hrs after which all survivors were euthanized. Lab personnel observing mice were blind to administration of drug.

Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion

An ischemic stroke was modeled by occlusion of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) as previously described (Longa et al., 1989). Male mice (25–30g) or Sprague Dawley rats (250–300g) were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in 100% O2 and MCA occlusion achieved by inserting a monofilament (mice: 6–0 nylon, 0.21 × 2 mm silicon tip; rat: 4–0 nylon, 0.43 × 2–3 mm silicon tip; Doccol, Corp., Sharon, MA, USA) to block the origin of the MCA. Reduction of cerebral blood flow was confirmed using Laser-Doppler flowmetry. Animals with cerebral blood flow reduction > 90% or < 70% were excluded from the study. After one hour of occlusion the filament was removed. Mice were treated by IP injection of either 5 mg/kg AER-271 or Vehicle (Tris buffered saline) every 3 hours beginning 75 min after initiating the occlusion. Rats were administered AER-271 by IV infusion with dosing as described in Fig. 6 beginning 2 hours after initiating the occlusion. Lab personnel, blind to the administration of drug, observed mice at 24 hours for basic neurological scoring (Yang et al., 1994) and rats at 48 hours using a modified Garcia score (Shimamura et al., 2006). Two independent data analysts, blind to the administration of AER-271, determined brain volume changes using MRI data collected at 24 (mice) or 48 hours (rats). Animals that did not survive two hours post-surgery likely expired due to complications during surgery and were therefore excluded from the study.

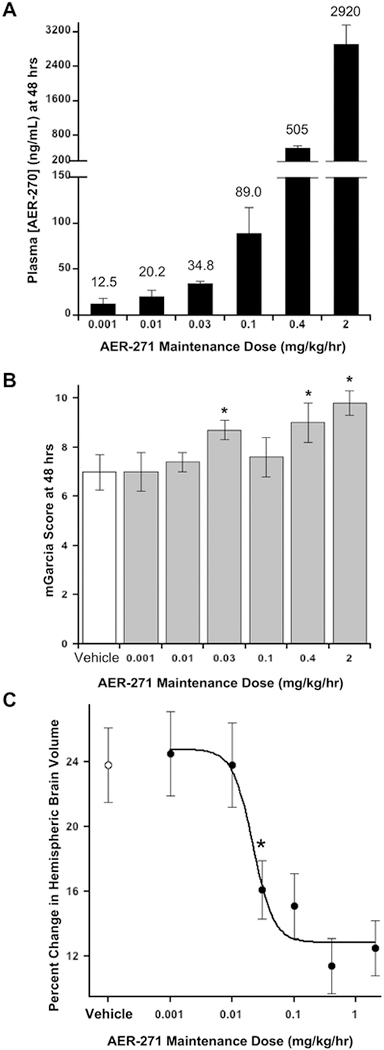

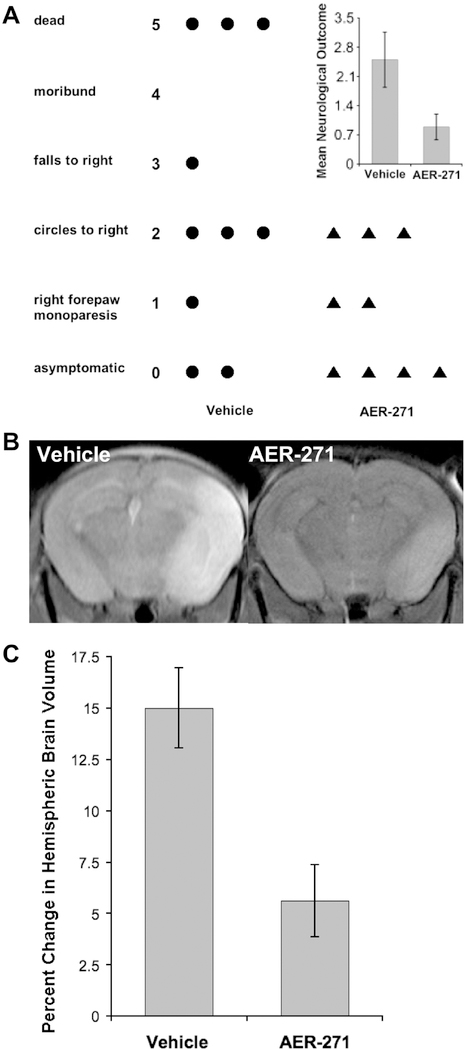

Fig. 6.

Rats treated with AER-271 show modestly improved outcomes and reduced cerebral edema in a model of ischemic stroke. (A) Plasma AER-270 concentration after 48 hours continuous IV infusion of AER-271. An acute ischemic stroke was modelled in rats by a temporary middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo) for one-hour. At two-hours after initiating the injury, rats were given a loading dose administered over 30 min followed by a continuous maintenance dose of AER-271 for 48 hours by IV infusion through an external jugular vein catheter. A loading dose of 10 mg/kg was used for 2 mg/kg/hr maintenance dose; 4 mg/kg for 0.4, 0.1 and 0.03 mg/kg/hr maintenance doses; and 1 mg/kg for 0.01 and 0.001 mg/kg/hr maintenance doses. After 48 hrs of dosing plasma levels of AER-270 were quantitated by LC-MS/MS. Mean Plasma concentration of AER-270 ± SEM with mean value shown on top of each bar. AER-271 maintenance doses of 2, 0.4, 0.1, 0.03, 0.01 and 0.001 mg/kg/hr utilized n=12, n=10, n=10, n=8, n=9 and n=9 rats, respectively. (B) Improved neurological outcome after intervention with AER-271 in the rat MCAo model. After 48 hrs of reperfusion, at the indicated maintenance doses, rats were evaluated for general neurological outcomes using the modified Garcia Score (mGarcia): scale from 0 dead to 15 unaffected, assessed by multiple aspects of movement and reaction to various stimuli (Shimamura et al., 2006). Mean mGarcia ± SEM; Vehicle n=10 rats, others as indicated in (A). * Student’s t-tests P < 0.02 relative to Vehicle control. (C) Reduced cerebral edema with administration of AER-271 in rat MCAo model. Changes in hemispheric brain volume, cerebral edema, were measured from T2-weighted MR images as described in Experimental Procedures. Mean Percent Change in Hemispheric Brain Volume ± SEM displayed for the same cohorts described in (A) and (B) above. Student’s t-tests P < 0.002 for doses ≥ 0.03 mg/kg/hr relative to Vehicle control.

Pharmacokinetics

Mice were injected intraperitoneal (IP) with either 0.8 mg/kg AER-270 in 6 mL water or 10 mg/kg AER-271 in 0.2 mL of Tris buffered saline. For mice, blood samples were collected by tail laceration and 2 mM EDTA added as an anticoagulant and to stabilize AER-270/271. Mice were perfused with PBS before decapitation and brains dissected and frozen at −20°C. Rats were administered AER-271 at the indicated doses (Fig. 6) by IV injection and continuous infusion using an external jugular vein catheter and blood samples drawn into heparinized glass capillaries using a tail vein catheter. Plasma samples were brought to 1.5% (v/v) ammonium hydroxide to stabilize AER-270/271 prior to centrifugation. Proteins were removed by 75% acetonitrile extraction. Brain extracts were initially generated by homogenization with an equal volume of PBS on ice, followed with further homogenization in 75% acetonitrile. Samples were cleared of aggregated proteins by centrifugation at 17,000×g for 10 min and AER-37 (Table 1) introduced as an internal standard. Samples were analyzed by tandem LC-MS/MS using C18 reversed-phase chromatography and mass analysis with Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) using a triple-quadrapole mass spectrometer at the Mass Spectrometry II Core, Lerner Research Institute (Cleveland Clinic Foundation). The method gave reliable quantitation for AER-270 (0.5–1000 ng/mL, data not shown). Data were fit to a single-dose Pharmacokinetic equation: C = ((F.D.ka)/(Vd(ka - ke)).(e−ke.t/(1 - e−ke) - e−ka.t/(1 - e−ka)); where, C concentration of drug, F bioavailability, D total dose, Vd volume of distribution, ka rate of absorption, ke rate of elimination and t time.

Brain Volume Change

Mouse brain volumes were assessed using T2-weighted MRI images collected at the Case Center for Imaging Research (Case Western Reserve University). Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in 100% O2. A 35 mm inner diameter volume coil was used to ensure uniform images over the entire brain. For water intoxication studies, sagittal images of the head were acquired using conventional spin echo (TR/TE = 3000/12 ms, resolution = 0.0195 cm/pixel, 3 averages, total scan time = 4 min 48 s) prior to water injection, 5:40 min post water injection, and every 5:20 min thereafter until the animal expired from the water load. Each scan contained twenty-five 0.7 mm contiguous imaging slices of which 12–14 slices contained a portion of the brain. The cross-sectional area of the brain in each imaging slice was measured by manual region-of-interest selection using DICOM images and ImageJ. Brain volumes were then calculated for each scan by summing the individual cross-sectional brain areas and multiplying by the slice thickness (0.7 mm). A similar approach was employed for MCAo experiments except coronal images were used so that right and left hemispheres could be easily discerned. Images (TR/TE = 3000/12 ms, resolution = 0.0078 (mice) or 0.0156 (rat) cm/pixel, 3 averages, total scan time = 9 min 36 s) were collected once after 24 hours of reperfusion for mice and 48 hours for rats. The volumes of the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres were quantitated separately using DICOM images and OsiriX (Pixmeo SARL, Bernex, Switzerland). Relative changes in hemispheric brain volume were calculated as a percent of the difference between ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres relative to the contralateral hemisphere as follows: ((Vi - Vc)/Vc) × 100%; where Vi is the ipsilateral brain volume and Vc is the contralateral brain volume. For all data analyses two lab personnel, blind to the administration of drug, quantitated brain volumes independently of each other.

RESULTS

High-throughput screening of AQP4 inhibitors - cell viability

A high-throughput screening (HTS) assay for AQP4 inhibitors was developed using human AQP4-M23 (AQP4) expressed in CHO cells. The effect of osmotic changes on cells without AQP4 was gauged using a separate CHO cell line expressing CD81, an unrelated transmembrane protein of similar size with no apparent effect on water permeability. When exposed to a hypoosmotic shock by replacing media with deionized water, AQP4-expressing cells showed enhanced water permeability, rapidly swelling then bursting, as compared to untransfected or CD81-expressing cells which swell but remain stable under these conditions (Fig. 1A).

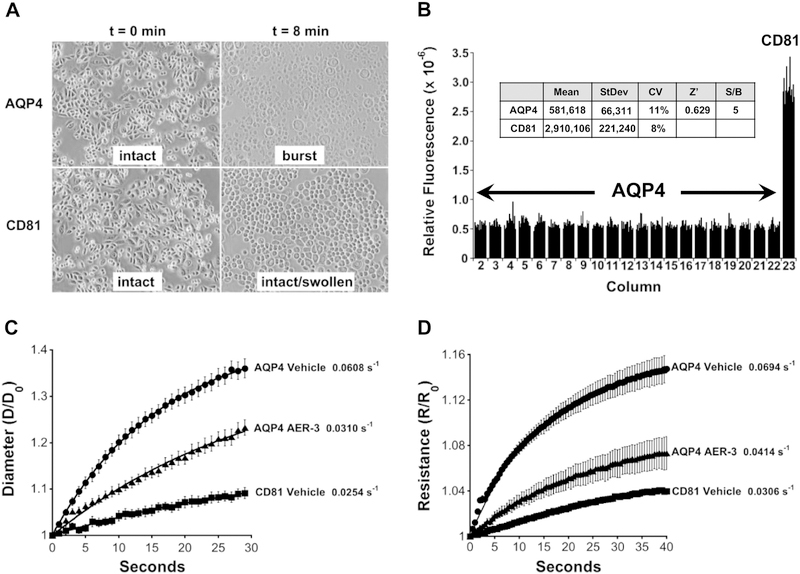

Fig. 1.

High throughput screen for inhibitors of AQP-4-mediated water permeability and cell swelling assays. (A) AQP4 imparts elevated osmotic sensitivity. CHO cells expressing human AQP4-M23 (AQP4) swell and burst within 8 min when exposed to a hypoosmotic shock (deionized water), whereas cells expressing a control membrane protein CD81 swell but remain intact. (B) High throughput assay for screening inhibitors of AQP4. The viability of cells exposed to hypoosmotic shock for 5.5 min, was measured using calcein-AM during recovery at normal osmolarity. Relative fluorescent intensity of calcein is plotted according to plate column position for CHO cells grown in a 384-well plate. AQP4 expressing cells show poor viability, lower fluorescence relative to CD81 expressing cells, and inhibitors of AQP4-mediated water permeability improve viability. Inset: 5.5 min of osmotic shock provided an optimal signal-to-noise ratio and plate statistics (Coefficient of Variation: CV = StDev/Mean; Z’ = 1 – 3[AQP4 StDev + CD81 StDev]/[AQP4 Mean - CD81 Mean]; n=14 for both AQP4 and CD81). (C) Phenylbenzamide AER-3 inhibits AQP4-mediated water movement assessed by changes in cell diameter observed with video microscopy during osmotic shock. CHO cells expressing CD81 or AQP4-M23 were given a hypoosmotic shock (deionized water), and cell diameters measured at the indicated times. Normalized mean diameters (D/Do) are plotted at the indicated times ± SEM (n=10 cells). (D) Inhibition of AQP4-mediated water movement by AER-3 assayed by Cell Volume Cytometry to measure cell volume change. CHO cells expressing AQP4-M23 or CD81 were exposed to a hypoosmotic shock and cell swelling monitored by comparing Initial Resistance (Ro) to Resistance (R) at subsequent time points using a microfluidics system. Normalized mean resistance (R/Ro) plotted ± SEM (n=4). For C and D, rate constants indicated adjacent to the fitted data.

Uptake of nonfluorescent acetoxymethyl-calcein (calcein-AM) and conversion to fluorescent calcein provided a quantitative measure of cell viability giving a robust detection system for the HTS assay. The rapid influx of water by AQP4 cells resulted in loss of viability within 4 min of exposure. In contrast, most CD81 cells remained viable after 8 min. As an endpoint HTS assay, calcein provided easily detectable signals with suitable plate statistics and signal-to-noise ratio at 5.5 min (Fig. 1B and inset).

The HTS assay was used to screen 161,000 compounds (see Experimental Procedures). Replicate analysis of the best performing compounds gave 13 confirmed hits that improved cell viability by at least 10%. Three of these compounds, AER-3, AER-7 and AER-22, were from the same structural class, phenylbenzamide (Table 1).

Hit Validation - AQP4-mediated water permeability

Several layers of hit validation were employed to ensure that compounds identified in the HTS assay were able to reduce AQP4-mediated water permeability rather than prevent AQP4-mediated cell death by some other means. Video microscopy was used to directly observe cell swelling. The diameter of AQP4 cells rapidly increased with time when exposed to a hypoosmotic shock, whereas this increase was 2.4-fold slower for CD81 control cells (Fig. 1C). In the presence of AER-3 the rate of AQP4 cell swelling was reduced, giving ~84% inhibition (see Experimental Procedures). A similar result was observed using video microscopy of Xenopus oocytes injected with human AQP4-M23 cRNA (~23% inhibition, data not shown).

Cell Volume Cytometry was also used to detect cell volume change with a hypoosmotic shock. Lowering the osmolarity from 300 to 100 mOsm increased the electrical resistance of AQP4 cells in a microfluidics chamber at a rate 2.3-fold faster than CD81 cells (Fig. 1D). In the presence of AER-3 this rate was again reduced giving ~72% inhibition.

Light scattering has been used to assess changes in water permeability conferred by aquaporins expressed in cells or reconstituted in proteoliposomes (Yang et al., 1997; Mola et al., 2009). This method was explored with a confluent monolayer of AQP4-expressing CHO cells grown in a 96-well plate using a microplate reader to observe changes in light scattering after a hyperosmotic shock, 300 to 375 mOsm (Fig. 2A). Initially shrinking cells cause an increase in absorbance due to the scattering of light by the increased density of individual cells. Cells remain adhered to the plate and subsequently cell membranes near points of cell-cell contact begin to thin and allow transmitted light to bring the absorbance down. (A similar but reciprocal response was observed with a hypoosmotic shock, 300 to 150 mOsm.) Using the rate of the initial rise in absorbance (cell shrinking now at 415 mOsm), the utility of this assay for detecting aquaporin inhibitors was investigated with CHO cells expressing AQP1, the mercury sensitive aquaporin (Zeidel et al., 1992). In the presence of 0.3 mM p-chloromercuribenzenesulfonic acid (pCMBS, Toronto Research Chemicals, Toronto Canada) AQP1-mediated water permeability was inhibited 36% and was readily reversed with β-mercaptoethanol (Fig. 2B). Conversely, pCMBS showed little effect on cells expressing AQP4, which is insensitive to mercury inhibition (Hasegawa et al., 1994).

Using this Light Scattering Assay AQP4 cells shrank 3.8-fold faster than CD81 controls (Fig. 2C). This increased rate of shrinking was reduced in the presence of AER-3, giving ~62% inhibition of AQP4-dependent water permeability.

Lead Selection - AER-270

The structure-activity relationships (SAR) of the phenylbenzamide series were explored with the Light Scattering Assay using compound analogues available from commercial catalogues and through custom synthesis (Table 2). Several iterative rounds of analysis led us independently to a compound designated AER-270 with >10-fold improved potency compared to AER-3, the initial phenylbenzamide hit from HTS (AER-3 IC50 ~5.1 μM, AER-37 ~5.2 μM and AER-270 ~0.42 μM). AER-270 also showed similar potency for AQP4-M23 derived from human, rat and mouse (Fig. 2D–F).

Remarkably, others have previously investigated a molecule identical to AER-270 as a topical antibiotic (Zerweck et al., 1967; Stecker 1967). More recently this compound was reported as an IkB kinase (IKK-β) inhibitor with good tolerance in rodents (Onai et al., 2004). Given that phosphorylation has been proposed to regulate trafficking or gating of AQP4 (Yukutake and Yasui 2010), the possibility that IKK-β inhibition affects AQP4-mediated water permeability was examined. Two known IKK-β inhibitors, PS-1145 (Castro et al., 2003) and TPCA-1 (Podolin et al., 2005), were tested and both failed to inhibit AQP4 (Fig. 2G–H). The ability of AER-270 to inhibit IKK-β and other kinases was also investigated by three independent contractors: Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA), Cerep (Poitiers, France) tested a panel of 210 kinases and DiscoveRx (Fremont, CA) tested a panel of 456 kinases. No inhibition of IKK-β, other kinases in the NFkB pathway or any other kinase tested was observed (data not shown).

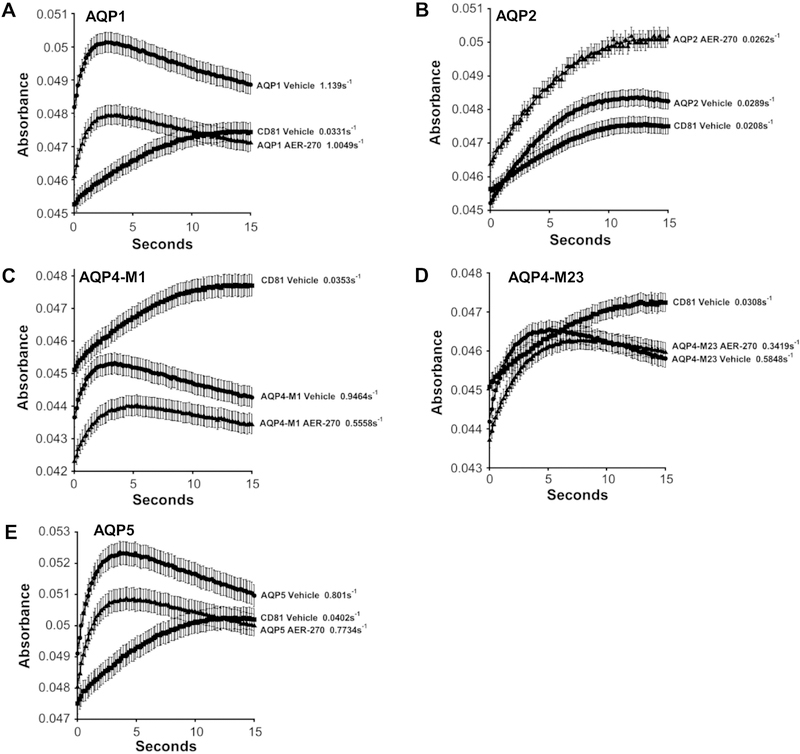

Aquaporin Selectivity

The ability of AER-270 to selectively inhibit AQP4-M23 was tested by comparison with four related aquaporins: AQP1, AQP2, AQP4-M1 (a variant of AQP4 with an extra 22 N-terminal amino acids) and AQP5. These additional aquaporins were expressed in CHO cells and enhanced water permeability confirmed by comparison with CD81-expressing cells using the Light Scattering Assay (Fig. 3). As expected, AQP4-M1 and AQP4-M23 showed similar inhibition at 44.9±1.4% and 48.8±1.6%, respectively. AQP2, responsible for water reabsorption in the collecting duct of the kidney, was difficult to assess due to its relatively weak contribution to water permeability in our assays. AQP1 and AQP5 showed limited or no inhibition, 13.2±1.1% and 4.5±0.7%, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Lead compound AER-270 preferentially inhibits AQP4. The indicated human aquaporins were stably expressed in CHO cell lines and assayed for water permeability with and without 10 μM AER-270 using the light scattering assay. (A) AQP1, (B) AQP2, (C) AQP4-M1, (D) AQP4-M23 and (E) AQP5. Mean absorbance plotted at the indicated times ± SEM (n=16 wells). Rate constants for the rise in each curve are shown. Percent Inhibition: AQP1 13.2±1.1%, AQP2 not determined, AQP4-M1 44.9±1.4%, AQP4-M23 48.8±1.6% and AQP5 4.5±0.7%.

Water Intoxication

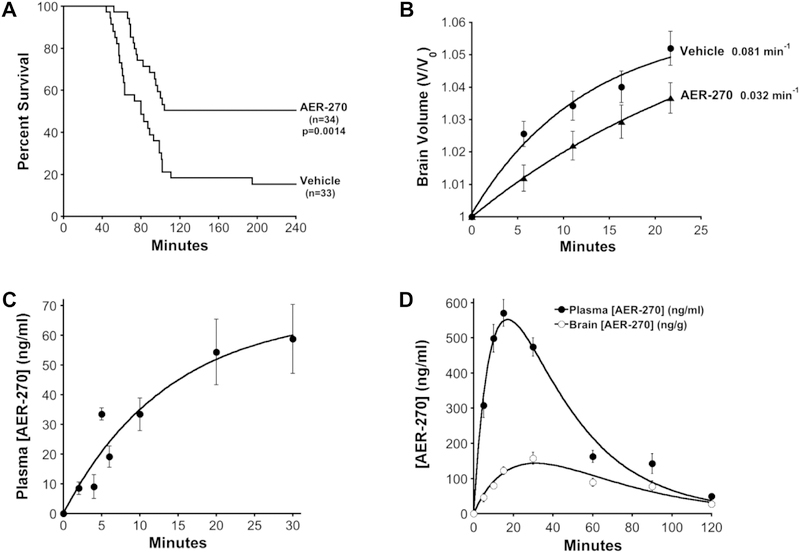

Water intoxication is a well-documented model for studying the effects of cerebral edema (Gullans and Verbalis 1993). In this model, a rapid drop in serum osmolarity is achieved by an IP infusion of water (20% body weight). Water moves with the osmotic gradient into the brain giving rapid cerebral edema without disruption of the BBB. Under this osmotic stress, AQP4-null mice show greatly improved survival and reduced cerebral edema compared to wild-type mice (Manley et al., 2000). In a vehicle control we observed 15.3% survival at 4hr (Fig. 4A, Vehicle). When AER-270 was included in the water bolus at 0.8 mg/kg, mice succumbed to the water load more slowly and the 4hr survival was 50.5% (Fig. 4A, AER-270) representing a 3.3-fold improvement in survival.

Fig. 4.

AER-270 reduces the effects of water intoxication in mice and pharmacokinetics of AER-270 and its prodrug AER-271. (A) AER-270 improves survival from water intoxication. Mice were given an IP injection of deionized water (20% body weight): Vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) or AER-270 (0.8 mg/kg, 0.1% DMSO). General neurological changes were followed for 4 hours and time of death recorded. The percent survival is plotted as a function of time, Vehicle n=33 and AER-270 n=34 mice. P value, significance of difference between Vehicle and AER-270 curves determined by Log-Rank Test using the Kaplan-Meier estimator, p=0.0014. (B) Cerebral edema is reduced by AER-270 during water intoxication as measured by MRI brain volume analysis. T2-weighted MRI scans of mice were collected before and during water intoxication in the presence or absence of 0.8 mg/kg AER-270. Normalized mean brain volume is shown for each time point and rate constants are shown adjacent to each curve ± SEM (n=14 mice). (C) Plasma levels of AER-270 during water intoxication. The plasma concentration of AER-270 was determined by LC-MS/MS from mice injected with AER-270 in water as described in (A). Mean plasma AER-270 plotted at indicated time points ± SEM, (n=3 mice). (D) Improved solubility of prodrug AER-271 permits higher dosing and increased plasma concentrations as well as detection of AER-270 in brain tissue. Mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of 10 mg/kg AER-271 and AER-270 determined by LC-MS/MS of plasma and brain samples. Mean plasma or brain tissue concentration plotted at the indicated time points ± SEM, (n=3 mice).

The formation of cerebral edema during water intoxication was assessed by MRI analysis of brain volume using high-resolution T2-weighted scans. Treatment with AER-270 reduced the rate of cerebral edema by 2.5-fold (Fig. 4B, Vehicle vs AER-270). A 10-fold lower dose of AER-270 had no effect on the rate of cerebral edema, indicating a dose-dependent relationship (data not shown). Analogues of AER-270 were tested for their ability to reduce cerebral edema during water intoxication: AER-533 (Table 2), which showed good efficacy inhibiting AQP4-mediated water permeability using cell-based assays also reduced the rate of cerebral edema (Table 3). By contrast, AER-311 (Table 2), which has no effect in cell-based assays, was ineffective in the water intoxication model (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of Aeromics’ compounds on AQP4-mediated water permeability and cerebral edema.

| Compound | Percent AQP4 Inhibition LSA Cell-Based Assay | Rate of Brain Swelling Water Toxicity Model (min-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 0 | 0.081 |

| AER-270 | 62.4+3.1 | 0.032 |

| AER-311 | 4.8+2.7 | 0.096 |

| AER-533 | 61.0+2.4 | 0.022 |

Prodrug development - AER-271

For water intoxication AER-270 was delivered simultaneously with a large bolus of water. Given the low solubility of AER-270 at neutral pH, 4 μg/ml, this made the maximum possible dose only 0.8 mg/kg, which gave a peak plasma concentration of ~60 ng/mL in the water intoxication model (Fig. 4C). Unfortunately, this method of drug delivery imposes a low upper limit for the dose of AER-270 that can be investigated and is impractical for other CNS injury models because the large volume of water also induces cerebral edema. To overcome this obstacle and others we developed a prodrug AER-271 (Table 1) with >5000-fold improved aqueous solubility. AER-271 was administered intraperitoneal (IP) to mice at 10 mg/kg and plasma as well as brain concentrations were followed for two hours by LC-MS/MS. Detection of AER-271 was limited due to poor recovery on LC-MS. Nevertheless, AER-270 was observed at high levels, peak plasma concentrations > 500 ng/ml, consistent with good bioconversion of AER-271 (Fig. 4D). AER-270 also showed good exposure in the brain with tissue concentrations peaking at > 100 ng/g (Fig. 4D). In mice, we estimate a rate of IP absorption/conversion 0.10 min−1 and elimination 0.029 min−1 for AER-270 derived from AER-271.

Middle Cerebral Artery occlusion - MCAo

An acute ischemic stroke was modeled in mice using an occlusion of the middle cerebral artery (MCAo) that results in reproducible neurological deficits, cerebral edema and damage to brain tissue (Longa et al., 1989). We used a temporary occlusion of one hour followed by 24 hours of reperfusion to study the efficacy of AER-271. Administration of AER-271 was started 75 min after initiating the occlusion. Due to the rapid elimination of AER-270, t1/2 ~24 min, we used a multi-dosing regimen during reperfusion (see Experimental Procedures) that sustained a plasma concentration of at least 79.0 ± 14.7 ng/ml AER-270. This level was targeted based on experience in the water intoxication model where a peak plasma concentration of 60 ng/mL AER-270 was observed. At 24 hours mice were scored for neurological outcome on a 5-point scale (Yang et al., 1994; Fig. 5A). Control mice receiving vehicle had an average neurological score of 2.50 ± 0.62, while mice treated with AER-271 had better outcomes with an average score of 0.89 ± 0.31 (Fig. 5A, inset; mean ± SEM; n=10 and n=9 mice, respectively; p=0.025). Notably, mice treated with AER-271 did not progress to severe paralysis or death.

Fig. 5.

Mice treated with AER-271 show improved outcomes and reduced cerebral edema in a model of ischemic stroke. (A) Improved neurological outcome following temporary, one-hour, middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo) in mice treated with AER-271. Mice were treated by multi-dosing (see Experimental Procedures) beginning 75 min after the occlusion was initiated using 5 mg/kg AER-271 or Vehicle and evaluated after 24 hours for general neurological outcomes (Yang et al., 1994). Inset: mean neurological outcome ± SEM, Student’s t-test P < 0.025. Vehicle n=10 mice and AER-271 n=9 mice. (B) Representative T2-weighted MR images of brains from mice receiving a temporary MCAo after 24 hrs of reperfusion. (C) Mice given a temporary MCAo and treated with AER-271 show reduced cerebral edema. Changes in hemispheric brain volume measured from T2-weighted MR images encompassing the entire brain. The mean Percent Change in Hemispheric Brain Volume (see Experimental Procedures) is displayed ± SEM for Vehicle n=7 and AER-271 n=9 mice, Student’s t-test P < 0.003.

Improvements in neurological outcome correlated well with control of cerebral edema. T2-weighted MRI scans showed significant swelling in the ipsilateral hemisphere of vehicle control mice with a relative change in ipsilateral brain volume of 15.01 ± 1.95% while mice treated with AER-271 showed a 5.63 ± 1.75% change (Fig. 5B and 5C, mean ± SEM, p=0.003). This represents a 2.6-fold reduction in brain swelling after MCAo and links the AER-270/271 pharmacology of reduced cerebral edema to improved outcomes in rodent stroke. When these studies were repeated at a 10-fold lower dose of AER-271, no improvement in either neurological outcome or cerebral edema was observed indicating a dose-dependent relationship for the efficacy of AER-271 (data not shown).

The effect of AER-271 on cerebral edema was further investigated using a similar MCAo stroke model in rat where an external jugular vein catheter allowed continuous intravenous (IV) infusion of AER-271. This study was undertaken for several reasons: further exploration of AER-271 efficacy in a larger animal, investigation of AER-271 dose-response to determine a minimum effective dose, and testing the utility of IV infusion for AER-271 (the route of administration anticipated for human use in an acute care setting). For this study, a one-hour occlusion time was followed at two-hours with a loading dose to achieve efficacious levels quickly followed by a maintenance dose to hold plasma AER-270 at a desired plasma concentration for 48 hrs (Fig. 6A). Animals receiving AER-271 showed improvements in neurological status at 48 hrs (Fig. 6B) that correlated well with dose-dependent reductions in cerebral edema (Fig. 6C). We observed a minimum effective dose of 4 mg/kg loading, 0.03 mg/kg/hr maintenance doses that reduced cerebral edema from 23.8 ± 2.3 (Vehicle) to 16.1 ± 1.8 percent swelling (Student’s t-test P < 0.002).

DISCUSSION

Aquaporins were discovered by Peter Agre and colleagues three decades ago, a discovery resulting in a shared Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 2003. This breakthrough led to a paradigm shift in our understanding of water physiology as the family of aquaporin genes were uncovered and their expression, tissue distribution and contribution to physiological processes like water reabsorption in the kidney were understood (Agre et al., 2002). The potential of aquaporins as a target for therapeutic intervention was confirmed when mice deficient of AQP4 at the BBB were shown to be highly resistant to cerebral edema and have improved neurological outcomes in models of CNS injury like severe ischemic stroke (Manley et al., 2000).

This discovery garnered considerable interest in finding AQP4 specific inhibitors that could be developed as anti-edema therapies for stroke and other indications complicated by cerebral edema. Unfortunately, none of these efforts have identified an inhibitor with sufficient specificity and potency (many require high μM concentrations) to gain widespread use or with the qualities necessary to treat CE in human stroke. We tested many of these putative AQP4 inhibitors and, in agreement with Yang et al., 2008, found no significant inhibition of AQP4-mediated water permeability in our tissue culture-based assays. Rizatriptan was investigated using Cell Volume Cytometry and rizatriptan, sumatriptan, acetazolamide and TGN-020 with the light scattering assay (data not shown). No inhibition of AQP4-mediated cell volume change was observed. The reason for these differences is unclear, but may be related to the use of serum in tissue culture as compared to well-defined buffers with oocytes where, in the absence of serum proteins, a higher free concentration of test article would be expected.

A different approach to identifying AQP4 inhibitors was taken in the current work. We developed a high throughput assay with a relatively binary response based on cell viability (Fig. 1). After screening 161,000 compounds, a structural series—phenylbenzamide—was identified with good activity and formed the basis for a medicinal chemistry program. A light scattering assay was chosen for its speed and ease of use to drive these efforts. This assay has been used in various forms by other investigators to study aquaporins (Yang et al., 1997; Mola et al., 2009), and we confirmed its utility for detecting inhibitors of aquaporin activity by comparing the inhibition of AQP1 and AQP4 with the mercury compound pCMBS (Fig. 2B). After investigating ~460 commercially available and 42 custom synthesized compounds the specific structural qualities necessary to inhibit AQP4 by a phenylbenzamide were revealed (Table 2).

Our medicinal chemistry effort independently led to a compound, AER-270, that is identical to a molecule proposed by others to be an IKK-β inhibitor (Onai et al., 2004; Tanaka et al., 2005). The possibility that IKK-β inhibition affects AQP4-mediated water permeability was investigated and no connection found (Fig. 2G–H). The ability of AER-270 to inhibit 456 different kinases including IKK-β was also interrogated by three independent contractors who reported no effect (data not shown). Given that AER-270 lacks the heterocyclic moieties typical of nearly all small molecule kinase inhibitors, these results are not wholly unexpected (Liu and Gray 2006). Protein Kinase C activators PMA and PDBu, reported to affect AQP4 activity, reviewed in Yukutake and Yasui 2010, were also investigated and no effect on AQP4-mediated water permeability was observed. Nevertheless, potential kinase sites in AQP4 and their effects on AQP4 activity and inhibition by AER-270 are currently being studied.

Off-target activity was further explored using a broad ligand screening assay (binding assays) to investigate AER-270 interactions with 80 different pharmacologically relevant targets including GPCRs, neurotransmitter receptors and ion channels (performed by Eurofins Scientific, Inc. formerly CEREP). Multiple potential off-target hits were observed, but upon follow-up functional assays no significant effect was observed at ≤ 2 μM AER-270 (data not shown). Similar results were obtained with Cytochrome P450 inhibition (Eurofins Scientific, Inc., data not shown).

Similar to observations made with AQP4-null mice (Manley et al., 2000), we found that mice co-injected with AER-270 were highly resistant to the effects of water intoxication (Fig. 4A). The anti-edema effect of AER-270 was rapid, inhibition of cerebral edema could be observed as early as 5 min, suggesting that the compound was not acting through inflammatory pathways (Fig. 2B). On the contrary, this rapid inhibition points at control of water movement, i.e. edema control. The poor solubility of AER-270, however, necessitated the development of a prodrug, AER-271, with improved aqueous solubility to facilitate higher dosing and IV administration in the MCAo models of ischemic stroke (Fig. 4D, 5 and 6). Using AER-271, neurological scores improved 2.8-fold with no mice succumbing to the insult and cerebral edema was reduced 2.6-fold in this stroke model (Fig. 5A and C). focused

We anticipate that AER-271 will be used in an acute care setting where neurologists will want to use IV infusion to administer the drug quickly so that CE can be slowed as early as possible. AER-271 was, therefore, further investigated for efficacy in a rat stroke model where IV catheters can be placed more reliably than in mice. In a rat MCAo ischemic stroke model good efficacy was observed with the control of CE and improved neurological outcomes (Fig. 6). AER-271 gave a strong dose-response relationship and a minimum effective maintenance dose of 0.03 mg/kg/hr was observed. Taken together with observations from the mouse models, these results establish a pharmacological proof-of-concept for an anti-edema medication targeting AQP4-based water movement in ischemic strokes that lead to large hemispheric infarctions and result in severe cerebral edema.

A limitation of the current work was the recovery period studied in the stroke models, 24 and 48 hours in mouse and rat, respectively. Our exploratory studies of AER-271 were focused on edema prevention, and these timepoints where cerebral edema reaches maximal values represented the best opportunity to observe the largest antiedema effect. While longer-term recovery is the ultimate goal, we chose to investigate these timepoints to place an emphasis on edema control as has been done in other studies (Manley et al., 2000; Simard et al., 2012).

In collaboration with several independent investigators, we explored the use of AER-271 in other animal models where AQP4 mediates the edematous movement of water. In a pediatric rat model of asphyxial cardiac arrest, global cytotoxic/ionic cerebral edema is observed post-resuscitation (Tress et al., 2014). In this model AER-271 was observed to prevent CE, improve early outcomes and reduce neuronal death and neuroinflammation (Wallisch et al., 2018). AQP4 is also found in cardiomyocytes where it has been shown to mediate cardiac edema in mouse models of myocardial infarction (Rutkovskiy et al., 2012; Warth et al., 2007). AER-271 was effective in reducing cardiac edema and improving transplant survival in a mouse cold ischemic storage model of cardiac transplantation (Ayasoufi et al., 2018). These results further demonstrate the utility of AER-271 for the control of cytotoxic edema where AQP4 facilitates water movement.

The utility of AER-271 in models of traumatic brain injury (TBI) was also investigated in collaboration with Operation Brain Trauma Therapy, a consortium of academic labs specializing in controlled cortical impact, parasagittal fluid percussion injury and penetrating ballistic-like brain injury models of TBI in rat. AER-271 showed no effect, neither benefit nor harm, in all three of these models (Kochanek et al., 2018). This may be explained by the observation that vasogenic brain edema is the primary source of CE in TBI, although there is some indication that cytotoxic edema also complicates recovery from the trauma (Donkin and Vink 2010). Interestingly, AQP4-null mice in a controlled cortical impact model of TBI showed only mildly reduced CE and modestly improved neurological outcomes (Yao et al., 2015B). A similar traumatic brain injury model in neonatal rats treated post injury with siRNA to reduce the expression of AQP4 by 30% also exhibited modestly reduced edema and early improvements in motor function and spatial memory (Fukuda et al., 2013). Thus, while elimination of AQP4 may show striking effects in models of ischemic stroke where cytotoxic/ionic edema is the primary cause of brain swelling, in TBI where vasogenic edema is a dominant contributor to CE these benefits appear to be dampened.

To date, anti-edema medications have had little clinical success. However, glyburide, the diabetic drug in use since the late 1960s, has recently been advanced to the clinic to treat cerebral edema. Based on a retrospective study of diabetic patients who were hospitalized for acute ischemic stroke (Kunte et al., 2007) and experiments using ischemic stroke models in rodents (Simard et al., 2006; Simard et al., 2009), glyburide has been proposed as a treatment for the prevention of CE in stroke and TBI (Simard et al., 2008). This sulfonylurea has a different mechanism of action relative to AER-271. It blocks the sulfonylurea receptor 1-regulated TRPM4 in astrocytes and cerebral vascular endothelial cells, thus inhibiting a sodium leakage pathway that contributes to osmotic imbalance during ischemia. Glyburide (CIRARA/BIIB093) is showing promise in humans (GAMES-RP) with encouraging effects on cerebral edema markers and improved mortality and functional outcomes at 90 and 120 days (Sheth et al., 2016; Sheth et al., 2018).

We envision a different approach for the treatment of severe cerebral edema. Rather than targeting one of many potential routes by which ischemia may lead to CE, we seek to control water permeability at the blood-brain barrier. Regardless of which ion channels/cotransporters or accumulation of metabolites in hypoxic tissue create the osmotic driving force for CE, the subsequent movement of water occurs through one final, common pathway—AQP4 (Papadopoulos and Verkman 2013; Nagelhus and Ottersen 2013; Stockum et al., 2015). Our approach to the control of CE is, therefore, mechanistically distinct from glyburide and other ion-channel inhibitors. Consequently, future studies exploring a combination of ion channel and water pore blockers warrant investigation to maximize the potential of anti-edema therapy.

HIGHLIGHTS.

High throughput screening of small molecule libraries reveals an inhibitor of Aquaporin-4

Medicinal Chemistry leads to development of AER-270 and IV prodrug AER-271, selective partial antagonist of Aquaporin-4

Aquaporin-4 inhibitor AER-270 prevents cerebral edema and improves survival in a mouse model of water intoxication

Aquaporin-4 inhibitor AER-271 reduces cerebral edema and improves neurological outcomes in rodent ischemic stroke models

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Robert Zamboni and Anthony Marfat for sharing their knowledge of drug development, the staff of the Case Center for Imaging Research, Wen-Hai Chou at Kent State University for assistance with rodent stroke models and Renliang Zhang at the Metabolomics Core of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. This work was supported by SBIR grants from the NIH-NINDS (Grant Numbers R43NS060199, R43NS074890 and R44NS060199) to M.F.P.

Abbreviations

- AQP4

aquaporin-4

- BBB

blood brain barrier

- CE

cerebral edema

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary cells

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- ICP

intracranial pressure

- IP

intraperitoneal

- LC-MS/MS

tandem liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- MCAo

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- TRPM4

transient receptor potential melastatin 4

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

G.W.F., C.H.H., S.M.F., J.M.D., A.G.A., J.M.B., P.R.M., W.F.B and M.F.P. were employees of and/or received compensation from Aeromics, Inc. All other authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Agre P, King LS, Yasui M, Guggino WB, Ottersen OP, Fujiyoshi Y, Engel A, Nielsen S (2002) Aquaporin water channels--from atomic structure to clinical medicine. J Physiol (Lond) 542:3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiry-Moghaddam M, Frydenlund DS, Ottersen OP (2004) Anchoring of aquaporin-4 in brain: molecular mechanisms and implications for the physiology and pathophysiology of water transport. Neuroscience 129:999–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders JJ, Brightman MW (1979) Assemblies of particles in the cell membranes of developing, mature and reactive astrocytes. J Neurocytol 8:777–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arac A, Blanchard V, Lee M, Steinberg GK (2009) Assessment of outcome following decompressive craniectomy for malignant middle cerebral artery infarction in patients older than 60 years of age. Neurosur Focus 26:E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayasoufi K, Kohei N, Nicosia M, Fan R, Farr GW, McGuirk PR, Pelletier MF, Fairchild RL, Valujskikh A (2018) Aquaporin 4 Blockade Improves Survival of Murine Heart Allografts Subjected to Prolonged Cold Ischemia. Am J Transplan 18:1238–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardutzky J, Schwab S (2007) Antiedema therapy in ischemic stroke. Stroke 38:3084–3094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkhemer OA, Fransen PSS, Beumer D, van den Berg LA, Lingsma HF, Yoo AJ, Schonewille WJ, Vos JA, et al. (2015) A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 372:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro AC, Dang LC, Soucy F, Grenier L, Mazdiyasni H, Hottelet M, Parent L, Pien C, et al. (2003) Novel IKK inhibitors: β-carbolines. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 13:2419–2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkin JJ, Vink R (2010) Mechanisms of cerebral edema in traumatic brain injury: therapeutic developments. Curr. Opin. Neurol 23:293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda AM, Adami A, Pop V, Bellone JA, Coats JS, Hartman RE, Ashwal S, Obenaus A, et al. (2013) Posttraumatic reduction of edema with aquaporin-4 RNA interference improves acute and chronic functional recovery. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 33:1621–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, Eesa M, Rempel JL, Thornton J, Roy D, Jovin TG, et al. (2015) Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 372:1019–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullans SR, Verbalis JG (1993) Control of Brain Volume During Hyperosmolar and Hypoosmolar Conditions. Annu Rev Med 44:289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H, Ma T, Skach W, Matthay MA, Verkman AS (1994) Molecular cloning of a mercurial-insensitive water channel expressed in selected water-transporting tissues. J Biol Chem 269:5497–5500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirt L, Fukuda AM, Ambadipudi K, Rashid F, Binder D, Verkman A, Ashwal S, Obenaus A, et al. (2017) Improved long-term outcome after transient cerebral ischemia in aquaporin-4 knockout mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 37:277–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossmann KA (1982) Treatment of experimental cerebral ischemia. J Cerebr Blood F Met 2:275–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber VJ, Tsujita M, Yamazaki M, Sakimura K, Nakada T (2007) Identification of arylsulfonamides as Aquaporin 4 inhibitors. Bioorgan Med Chem Lett 17:1270–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber VJ, Tsujita M, Kwee IL, Nakada T (2009A) Inhibition of aquaporin 4 by antiepileptic drugs. Bioorgan Med Chem 17:418–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber VJ, Tsujita M, Nakada T (2009B) Identification of Aquaporin 4 inhibitors using in vitro and in silico methods. Bioorgan Med Chem 17:411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek PM, Bramlett HM, Dixon CE, Dietrich WD, Mondello S, Wang KKW, Hayes RL, Lafrenaye A, et al. (2018) Operation Brain Trauma Therapy: 2016 Update. Mil Med 183:303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunte H, Schmidt S, Eliasziw M, del Zoppo GJ, Simard JM, Masuhr F, Weih M, Dirnagl U (2007) Sulfonylureas improve outcome in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 38:2526–2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaManna JC (1996) Hypoxia/ischemia and the pH paradox. Adv Exp Med Biol 388:283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y and Gray NS (2006) Rational design of inhibitors that bind to inactive kinase conformations. Nat Chem Biol 2:358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R (1989) Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke 20:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Yang B, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS (1997) Generation and phenotype of a transgenic knockout mouse lacking the mercurial-insensitive water channel aquaporin-4. J Clin Invest 100:957–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GT, Fujimura M, Ma T, Noshita N, Filiz F, Bollen AW, Chan P, Verkman AS (2000) Aquaporin-4 deletion in mice reduces brain edema after acute water intoxication and ischemic stroke. Nat Med 6:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarou A (2007) A review of progress in understanding the pathophysiology and treatment of brain edema. Neurosurg Focus 22:E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliati E, Meurice N, DuBois P, Fang JS, Somasekharan, Beckett E, Flynn G, Yool AJ (2009) Inhibition of Aquaporin-1 and Aquaporin-4 Water Permeability by a Derivative of the Loop Diuretic Bumetanide Acting at an Internal Pore-Occluding Binding Site. Mol Pharmacol 76:105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlynash M, Lansberg MG, De Silva DA, Lee J, Christensen S, Straka M, Campbell BCV, Bammer R, et al. (2011) Refining the definition of the malignant profile: insights from the DEFUSE-EPITHET pooled data set. Stroke 42:1270–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mola MG, Nicchia GP, Svelto M, Spray DC, Frigeri A (2009) Automated cell-based assay for screening of aquaporin inhibitors. Anal Chem 81:8219–8229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhus EA, Ottersen OP (2013) Physiological roles of aquaporin-4 in brain. Physiol Rev 93:1543–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Collins VE, Macleod MR, Donnan GA, Horky LL, van der Worp BH, Howells DW (2006) 1,026 experimental treatments in acute stroke. Ann Neurol 59:467–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onai Y, Suzuki J, Kakuta T, Maejima Y, Haraguchi G, Fukasawa H, Muto S, Itai A, et al. (2004) Inhibition of IkappaB phosphorylation in cardiomyocytes attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res 63:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos MC, Verkman AS (2005) Aquaporin-4 gene disruption in mice reduces brain swelling and mortality in pneumococcal meningitis. J Biol Chem 280:13906–13912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos MC, Verkman AS (2013) Aquaporin water channels in the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci 14:265–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolin PL, Callahan JF, Bolognese BJ, Li YH, Carlson K, Davis TG, Mellor GW, Evans C, et al. (2005) Attenuation of murine collagen-induced arthritis by a novel, potent, selective small molecule inhibitor of IkappaB Kinase 2, TPCA-1 (2-[(aminocarbonyl)amino]-5- (4-fluorophenyl)-3-thiophenecarboxamide), occurs via reduction of proinflammatory cytokines and antigen-induced T cell proliferation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 312:373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash JE, Yasumura T, Hudson CS, Agre P, Nielsen S (1998) Direct immunogold labeling of aquaporin-4 in square arrays of astrocyte and ependymocyte plasma membranes in rat brain and spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:11981–11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkovskiy A, Stensløkken K-O, Mariero LK, Skrbic B, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Hillestad V, Valen G, Perreauly M-C, et al. (2012) Aquaporin-4 in the heart: expression, regulation and functional role in ischemia. Basic Res Cardiol 107:280–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun S, Bell BA, Verkman AS, Papadopoulos MC (2008) Greatly improved neurological outcome after spinal cord compression injury in AQP4-deficient mice. Brain 131:1087–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanak D, Nosal V, Horak D, Bartkova A, Zelenak K, Herzig R, Bucil J, Skoloudik D, et al. (2006) Impact of diffusion-weighted MRI-measured initial cerebral infarction volume on clinical outcome in acute stroke patients with middle cerebral artery occlusion treated by thrombolysis. Neuroradiology 48:632–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 9:671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth KN, Elm JJ, Molyneaux BJ, Hinson H, Beslow LA, Sze GK, Ostwaldt A-C, del Zoppo GJ, et al. (2016) Safety and efficacy of intravenous glyburide on brain swelling after large hemispheric infarction (GAMES-RP): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. The Lancet 15:1160–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth KN, Petersen NH, Cheung K, Elm JJ, Hinson HE, Molyneaux BJ, Beslow LA, Sze GK, et al. (2018) Long-Term Outcomes in Patients Aged ≤70 Years With Intravenous Glyburide From the Phase II GAMES-RP Study of Large Hemispheric Infarction: An Exploratory Analysis. Stroke 49:1457–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura N, Matchett G, Tsubokawa T, Ohkuma H, Zhang J (2006) Comparison of silicon-coated nylon suture to plain nylon suture in the rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model. J Neurosci Methods 156:161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard JM, Chen M, Tarasov KV, Bhatta S, Ivanova S, Melnitchenko L, Tsymbalyuk N, West GA, et al. (2006) Newly expressed SUR1-regulated NC(Ca-ATP) channel mediates cerebral edema after ischemic stroke. Nat Med 12:433–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard JM, Woo SK, Bhatta S, Gerzanich V (2008) Drugs acting on SUR1 to treat CNS ischemia and trauma. Curr Opin Pharmacol 8:42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard JM, Yurovsky V, Tsymbalyuk N, Melnichenko L, Ivanova S, Gerzanich V (2009) Protective Effect of Delayed Treatment with Low-Dose Glibenclamide in Three Models of Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 40:604–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard JM, Woo SK, Tsymbalyuk N, Voloshyn O, Yurovsky V, Ivanova S, Lee R, Gerzanich V (2012) Glibenclamide-10-h Treatment Window in a Clinically Relevant Model of Stroke. Transl Stroke Res 3:286–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard JM, Sheth KN, Kimberly WT, Stern BJ, del Zoppo GJ, Jacobson S, Gerzanich V (2013) Glibenclamide in Cerebral Ischemia and Stroke. Neurocrit Care 20:319–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solenov E, Watanabe H, Manley GT, Verkman AS (2004) Sevenfold-reduced osmotic water permeability in primary astrocyte cultures from AQP-4-deficient mice, measured by a fluorescence quenching method. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286:C426–C432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecker HC (1967) Bistrifluoromethyl Anilides, Patent 3,331,874, USA.

- Stokum JA, Kurland DB, Gerzanich V, Simard JM (2015) Mechanisms of astrocyte-mediated cerebral edema. Neurochem Res 40:317–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait MJ, Saadoun S, Bell BA, Verkman AS, Papadopoulos MC (2010) Increased brain edema in aqp4-null mice in an experimental model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neuroscience 167:60–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka A, Konno M, Muto S, Kambe N, Morii E, Nakahata T, Itai A, Matsuda H (2005) A novel NF-kappaB inhibitor, IMD-0354, suppresses neoplastic proliferation of human mast cells with constitutively activated c-kit receptors. Blood 105:2324–2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tradtrantip L, Jin B-J, Yao X, Anderson MO, Verkman AS (2017) Aquaporin-Targeted Therapeutics: State-of-the-Field. Adv Exp Med Biol 969:239–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tress EE, Clark RS, Foley LM, Alexander H, Hickey RW, Drabek T, Kochanek PM, Manole MD (2014) Blood brain barrier is impermeable to solutes and permeable to water after experimental pediatric cardiac arrest. Neurosci Lett 578:17–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkman AS, Anderson MO, Papadopoulos MC (2014) Aquaporins: important but elusive drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 13:259–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallisch JS, Janesko-Feldman K, Alexander H, Jha RM, Farr GW, McGuirk PR, Pelletier MF, Kline AE, et al. (2018) The aquaporin-4 inhibitor AER-271 blocks acute cerebral edema and improves early outcome in a pediatric model of asphyxial cardiac arrest. Pediatr Res 104:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Tsuji K, Lee S-R, Ning M, Furie KL, Buchan AM, Lo EH (2004) Mechanisms of hemorrhagic transformation after tissue plasminogen activator reperfusion therapy for ischemic stroke. Stroke 35:2726–2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warth A, Eckle T, Kohler D, Faigle M, Zug S, Klingel K, Eltzschig HK, Wolburg H (2007) Upregulation of the water channel aquaporin-4 as a potential cause of postischemic cell swelling in a murine model of myocardial infarction. Cardiology 107:402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijdicks EFM, Sheth KN, Carter BS, Greer DM, Kasner SE, Kimberly WT, Schwab S, Smith EE, et al. (2014) Recommendations for the Management of Cerebral and Cerebellar Infarction with Swelling: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 45:1222–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Chan PK, Chen J, Carlson E, Chen SF, Weinstein P, Epstein CJ, Kamii H (1994) Human copper-zinc superoxide dismutase transgenic mice are highly resistant to reperfusion injury after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 25:165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, van Hoek AN, Verkman AS (1997) Very High Single Channel Water Permeability of Aquaporin-4 in Baculovirus-Infected Insect Cells and Liposomes Reconstituted with Purified Aquaporin-4. Biochemistry 36:7625–7632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Zhang H, Verkman AS (2008) Lack of aquaporin-4 water transport inhibition by antiepileptics and arylsulfonamides. Bioorgan Med Chem 16:7489–7493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Derugin N, Manley GT, Verkman AS (2015A) Reduced brain edema and infarct volume in aquaporin-4 deficient mice after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Neurosci. Lett. 584:368–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Uchida K, Papadopoulos MC, Zador Z, Manley GT, Verkman AS (2015B) Mildly Reduced Brain Swelling and Improved Neurological Outcome in Aquaporin-4 Knockout Mice following Controlled Cortical Impact Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma 32:1458–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo AJ, Verduzco LA, Schaefer PW, Hirsch JA, Rabinov JD, Gonzalez RG (2009) MRI-based selection for intra-arterial stroke therapy: value of pretreatment diffusion-weighted imaging lesion volume in selecting patients with acute stroke who will benefit from early recanalization. Stroke 40:2046–2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young W, Rappaport ZH, Chalif DJ, Flamm ES (1987) Regional brain sodium, potassium, and water changes in the rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model of ischemia. Stroke 18:751–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yukutake Y, Yasui M (2010) Regulation of water permeability through aquaporin-4. Neuroscience 168:885–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidel ML, Ambudkar SV, Smith BL, Agre P (1992) Reconstitution of functional water channels in liposomes containing purified red cell CHIP28 protein. Biochemistry 31:7436–7440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerweck W, Trosken O, Hintermeier K (1967) Trifluoromethyl-substituted salicylanilides. Patent 3,332,996, USA.

- Zhao F, Deng J, Xu X, Cao F, Lu K, Li D, Cheng X, Wang X, Zhao Y (2018) Aquaporin-4 Deletion Ameliorates Hypoglycemia-Induced BBB Permeability by Inhibiting Inflammatory Responses. J Neuroinflamm 15:157–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]