Introduction

Cholemic nephrosis represents a spectrum of bilirubin and bile cast mediated renal injury from proximal tubulopathy, acute tubular injury (ATI), intrarenal bile cast formation, tubular obstruction to renal failure. Elevated plasma concentrations of bile salts and both conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin, putatively mediate the nephrotoxicity, causing a functional derangement of renal tubule cells with intact renal architecture, primarily in patients with severe liver dysfunction.1 Published data on renal histology in cholemic nephrosis is scarce. Both bilirubin and bile salts are potential nephrotoxins in animal models, but their precise role in the pathogenesis of jaundice-related nephropathy is not known.2, 3, 4 We present a case of cholemic nephrosis with severe liver dysfunction.

Case report

A 47 year old male patient, known alcoholic, presented with a two-week history of yellowish discoloration of eyes, abdominal distension, reduced appetite for one month and high colored urine for four months. No history of any behavioral changes, fever, pain abdomen, hematemesis, malaena, reduced urinary output, hematuria or behavioral abnormalities were present. History of chronic alcohol consumption (360–440 mL/day for last 20 years) was elicited. Icterus, mild bipedal edema and multiple petechiae on the abdomen along with normal vitals were seen. Abdominal distension with ascites and a 4 cm palpable liver was observed and confirmed by ultrasonography. He was diagnosed as acute alcoholic hepatitis with oliguric renal injury. Serology for HIVI and II, HBsAg, hepatitis E, hepatitis C were negative however IgM anti-hepatitis A was positive. While on treatment with parenteral pantoprazole, vitamin K and empirical meropenem, coagulopathy was noticed in the form of ecchymotic patches over right flank, passage of black-colored stools and spontaneous mucocutaneous bleeding. Coagulation profile was deranged. The diagnosis was revised as acute on chronic liver failure, acute HAV infection, alcoholic liver disease with decompensation (ascites and coagulopathy), ATI with intermittent encephalopathy and hepatorenal syndrome.

Laboratory investigations (with initial and final values) revealed hemoglobin 12.8–6.3 g/dL; leukocyte count 14,800–10,800/dL, 82% polymorphs, 10% lymphocytes, 2% monocytes and 6% eosinophils, left shift, toxic granules in >20% neutrophils, platelets 80,000–110,000/dL and ESR 30 mm at 1 h. Chest radiograph was normal. PT and INR were 23/12–19.6/12 and 1.9–1.63. Liver function tests revealed total bilirubin 26.5–41.7 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 13.3–23.4 mg/dL, AST 121–114 IU/L, ALT 163–62 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 199–216 IU/L and amylase 205–463 U/L. Total proteins were 6.5 g/dL with albumin 3.9 g/dL. Urea and creatinine were 136–236 and 2.8–8.2 mg/dL. Na+, K+ and Ca2+ ions were 140–143, 4.4–2.4 mmol/L and 9.3–8.7 mg/dL. Random blood sugar was 69–61 mg/dL. Traces of albumin, 1–2 pus cells/hpf and yellowish casts were observed in urine. Escherichia coli susceptible to nitrofurantoin and imipenem was isolated consecutively from urine. Approximately 480 mL drainage of blood-mixed ascitic fluid revealed numerous erythrocytes and leucocytes with lymphocyte predominance, lymphocyte:neutrophil: 60:40 ratio, protein 3.4 mg/dL, albumin 1.9 mg/dL, sugar 118 mg/dL and LDH 640 mg/dL. No organism was isolated from ascitic fluid.

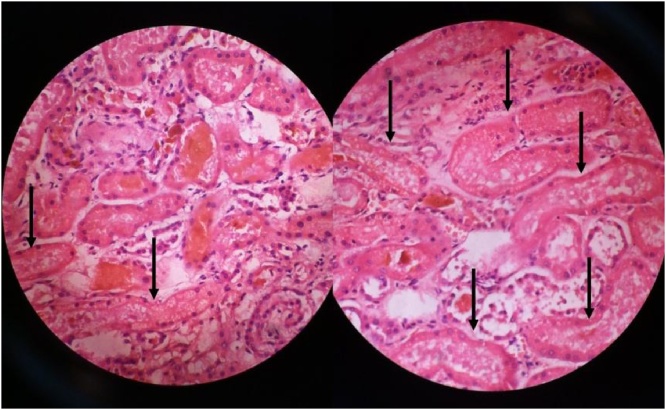

The patient was further managed with parenteral albumin 20%, frusemide, pantoprazole, meropenem, metronidazole, multivitamins, pentoxyfylline, l-ornithine aspartate and fresh frozen plasma transfusion along with oral lactulose. The patient rapidly deteriorated with increasing azotemia, coagulopathy, dyselectrolytemia, jaundice and ascites before peritoneal dialysis could be safely attempted. Grade I encephalopathy worsened to coma requiring non-invasive ventilatory support. Dual inotropic support was extended. He suffered a cardiac arrest and could not be resuscitated despite aggressive efforts. Postmortem revealed a 2000 g liver with an irregular surface with multiple micro and macronodules. Cirrhosis of liver with macrovesicular steatosis and chronic cholestasis was evident. Spleen was 650 g, firm, enlarged and congested. Bilateral interstitial pneumonia with pulmonary edema was seen. Both kidneys weighed 270 g, had non-adherent capsules, greenish-yellow cut surface and multiple green spots in corticomedullary junction. Both kidneys revealed bile casts in renal tubules on Hall's stain with bile staining of necrosed cells and tubular casts. Focal necrosis and desquamation of lining epithelium was seen in few tubules. Findings were consistent with cholemic nephrosis (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Gross photograph of bile stained kidneys weighing 270 g each.

Fig. 2.

Photomicrograph of bile casts in renal tubules (H&E 400×).

Fig. 3.

Photomicrograph of bile casts in renal tubules (Halls’ Fouchest stain 400×).

Discussion

The patient suffered from cholemic nephrosis due to underlying severe hepatic dysfunction while E. coli in urine represents healthcare-associated urinary tract infection. Bilirubin in concentrations of >20 mg/dL can cause a functional proximal tubulopathy or may precipitate into casts associated with ATI, even in the absence of portal hypertension or other common causes of ATI. Bile casts may complicate renal injury of severely jaundiced patients by direct bile and bilirubin toxicity and tubular obstruction to cause renal failure. Most of the damage occurs at distal nephron. ATI is a result of tubular epithelial cell injury and peritubular capillary endothelial cell injury caused by depletion of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and angiogenic factors, and decrease in RBC velocity and renal inflammation; thereby affecting microcirculation.5 The entity has been described in relation to severe liver dysfunction6 and anabolic steroid abuse.7 Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a major complication in patients with acute liver failure and chronic liver disease. Hemodynamic changes appear to be the principal alterations in these conditions, therefore there should be no known structural abnormalities responsible for AKI. On the other hand, several authors have published data on structural changes known as bile cast nephropathy or cholemic nephrosis, which basically consist of the presence of bile casts in tubular lumen analogous to those observed in myeloma, so management should be directed toward acute kidney injury.6 Depending on the study population, bile cast formation ranges from 2.6% to 73.5% of examined kidneys. Holmes et al.10 studied 68 autopsies of jaundiced individuals mostly due to obstructive causes and observed swelling of the tubular epithelium, pigmented casts, hypertrophy, and hyperplasia of the parietal layer of Bowman's capsule in 50 (73.5%) cases. De Tezanos et al.11 found renal bile casts in 13 (12%) of 105 patients with liver disease and renal dysfunction, which is similar to the percentage of cases in our study with severe bile cast formation. Bal et al.9 identified bile casts in all three post-mortem kidney biopsies from patients who died of subacute hepatic failure. Shet et al.8 found that renal bile casts were more prominent and extensive in biliary cirrhosis and involved four of seven pediatric patients with extrahepatic biliary atresia at autopsy.

Cholemic nephrosis, as a distinct entity, is debated to be a part of the spectrum of hepatorenal syndrome or any other unidentifiable cause of ATI. The entity is distinct from hepatorenal syndrome which is caused by intrarenal vasoconstriction and is purely functional; although histopathology of ATI may be seen.1 Both mechanisms are analogous to the injury by myeloma or myoglobin casts. The casts in our case significantly correlated with higher serum total and direct bilirubin levels, creatinine and transaminases; are thus form appropriate markers of severe renal injury.6, 8, 9 Likelihood of bile cast formation increases with prolonged exposure to high levels of bilirubin, which are typically >20 mg/dL.6 Further series studies are required which the authors propose to undertake as a observation study in autopsy series. Kidney biopsy is necessary to diagnose bile cast nephropathy,6 which may otherwise be overlooked in these patient population. If suspected, renal biopsy to be done after PT INR.

Conclusion

Patients with serum bilirubin concentrations >20 mg/dL are more prone to develop a functional proximal tubulopathy while bile casts may further cause tubular obstruction resulting in renal failure. Altered renal function in such a setting should raise a high index of suspicion for cholemic nephrosis and renal biopsy should be done and management should be directed toward acute kidney injury.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Betjes M.G., Bajema I. The pathology of jaundice-related renal insufficiency: cholemic nephrosis revisited. J Nephrol. 2006;19(2):229–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fickert P., Krones E., Pollheimer M.J. Bile acids trigger cholemic nephropathy in common bile duct ligated mice. Hepatology. 2013;58(6):2056–2069. doi: 10.1002/hep.26599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee J., Azzaroli F., Wang L. Adaptive regulation of bile salt transporters in kidney and liver in obstructive cholestasis in the rat. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1473–1484. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka Y., Kobayashi Y., Gabazza E.C. Increased renal expression of bilirubin glucuronide transporters in a rat model of obstructive jaundice. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:G656–G662. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00383.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimizu A., Ishii E., Masuda Y. Renal inflammatory changes in acute hepatic failure-associated acute kidney injury. Am J Nephrol. 2013;37(4):378–388. doi: 10.1159/000348567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Slambrouck C.M., Salem F., Meehan S.M., Chang A. Bile cast nephropathy is a common pathologic finding for kidney injury associated with severe liver dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2013;84:192–197. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luciano R.L., Castano E., Moeckel G., Perazella M.A. Bile acid nephropathy in a bodybuilder abusing an anabolic androgenic steroid. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(3):473–476. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shet T., Kandalkar B., Balasubramaniam M., Phatak A. The renal pathology in children dying with hepatic cirrhosis. Ind J Pathol Microbiol. 2002;45:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bal C., Longkumer T., Patel C., Gupta S.D., Acharya S.K. Renal function and structure in subacute hepatic failure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:1318–1324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes T.W. The histologic lesion of cholemic nephrosis. J Urol. 1953;70(5):677–685. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)67968-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Tezanos Pinto S., Aguirre J.H., Silva L. Hepatorenal syndrome glomerulosclerosis and cholemic nephrosis. Rev Med De Chile. 1969;97(3):179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]