Abstract

Autophagy, the cell process of self‐digestion, plays a pivotal role in maintaining energy homoeostasis and protein synthesis. When required, it causes degradation of long‐lived proteins and damaged organelles, indicating that it may play a dual role in cancer, by both protecting against and promoting cell death. The autophagy‐related gene (Atg) family, with more than 35 members, regulates multiple stages of the process. Serine/threonine protein kinase Atg1 in yeast, for example, can interact with other ATG gene products, functioning in autophagosome formation. One mammalian homologue of Atg1, UNC‐51‐like kinase 1 (ULK1) and its related complex ULK1–mAtg13–FIP200 can mediate autophagy under nutrient‐deprived conditions, by protein–protein interactions and post‐translational modifications. Although specific mechanisms of how ULK1 and its complex transduces upstream signals to the downstream central autophagy pathways is not fully understood, past studies have indicated that ULK1 can both suppress and promote tumour growth under different conditions. Here, we summarize some properties of ULK1 which can regulate autophagy in cancer, which may shed new light on future cancer therapy strategies, utilizing ULK1 as a potential new target.

Introduction

Autophagy is a highly regulated self‐digestion process, which plays a pivotal role in maintaining energy homoeostasis and protein synthesis during metabolic stresses by degradation of long‐lived proteins and damaged organelles 1. It was first described half a century ago, after discovery of the connection between autophagic dysfunction and multiple diseases 2; research into autophagy's molecular mechanisms has gradually increased over the last decade. There are three models of autophagy: macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone‐mediated autophagy, of which macroautophagy is the best known and most studied (referred to simply as ‘autophagy’ hereafter). Macroautophagy is the vesicular mode of transport of intracellular components to lysosomes, during which process cytosolic components are enclosed within a specific double membraned vesicle called an autophagosome, essential and unique in macroautophagy.

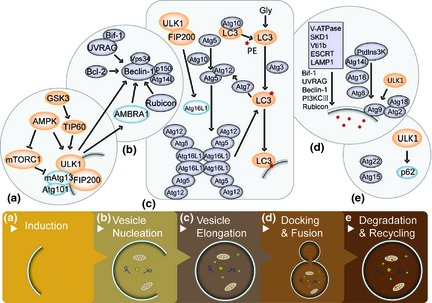

Autophagy can be divided into five stages: induction; nucleation; elongation and completion; docking and fusion; degradation and recycling 3, 4. Multiple proteins are involved in the stages and genetic studies in yeast have confirmed a series of proteins expressed by Atgs (autophagy‐related genes). Up now, more than 35 Atg proteins have been identified, most of which regulate formation of the autophagosome. Atg1 was the first known autophagy protein, found in yeast 5, and as the only serine/threonine kinase of Atg proteins, it forms a complex with Atg13 and Atg17 initiating formation of autophagosomes 6. UNC51‐like kinase 1 (ULK1), the homologue of Atg1 in mammals, has a similar function to Atg1 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

UNC51‐like kinase 1 (ULK1) and its complex participate in the five stages of autophagy. Autophagy is divided into five different stages: (a) induction, (b) nucleation, (c) elongation and completion, (d) docking and fusion and (e) degradation and recycling. ULK1 is involved in multiple steps and can activate signallig pathways through different targets, indicating the significant role it plays in autophagosome formation.

During the process of assembling autophagosomes in mammals, two major homoeostatic regulators, mammalian TOR complex 1(mTORC1) and AMP‐activated kinase (AMPK), sense starvation stress signals and pass them on to ULK1, via post‐translational modifications 19, 22. Under normal conditions, with no upstream signalling, AMPK is inactive, while the vital regulator of cell growth, mTORC1, represses autophagy by inhibition of ULK1 kinase activity and control of Atg9 trafficking. Atg9 is the only multiple spanning membrane protein so far identified, required for autophagy in both yeast and mammalian cells 7. Under starvation stress, AMPK induces activity of ULK1 by inhibiting activity of mTORC1 and directly phosphorylating ULK1. Subsequently, ULK1 and its related complex, ULK1–mAtg13–FIP200 are activated and release necessary downstream signals. The mammalian ULK complex is present on phagophores 8, and together with class III phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase complex (consisting of Beclin1, ATG14L, Vps34, and Vps15), regulates initial events of autophagosome formation 9, 10. Next, two ubiquitin‐like (Ub‐like) conjugation systems, Atg12–5–16 complex and PE‐modified Atg8, drive downstream events. Atg8 was first identified in yeast; mammalian cells have several Atg8‐like molecules, for exampe LC3, GABARAP and GATE‐16, of which the first two have multiple family members. Function of these two Ub‐like complexes is intimately linked; Atg12–5–16 complex has been shown to recruit LC3 conjugation machinery 11 and these systems work together to drive membrane expansion and fusion 12. During autophagy, carboxy‐terminal lipid modification of LC3 is required for autophagosome formation 13. Thus, by analysis of LC3‐II, action of autophagosome formation has been deduced. In addition, Atg8 family members recruit to the autophagosomal membrane, proteins that contain an LC3‐interacting region (LIR). The final stage of autophagy degrades long‐lived proteins and organelles in the docking complex of isolation membrane and lysosome.

Current data suggest that ULK1 is the major regulator of initial steps of autophagy 13, and interacts with FIP200 and mAtg13 forming an ULK1–mAtg13–FIP200 complex, which senses upstream signalling and easily transforms this to downstream targets. Investigation of ULK1 is rapidly expanding and accelerating this field of research; increasing reports indicate that ULK1 and its related complex is regulated by a variety of signalling pathways through myriads of modifications, implementing its function via refined pathways. Recently, due to the two‐sided roles of autophagy in different diseases (specially in the cancer and neuronal degeneration), research has become interested in ULK1 as a potential therapy target to cure different conditions. As the essential roles ULK1 complex holds in autophagosome formation, targeting upstream signals of ULK1 can affect autophagy; there already exist avenues of research that target AMPK or mTOR in cancer cells, by regulating activation of ULK1. Compounds concerned promote or suppress cell growth or other cancer hallmarks. In this review, we summarize knowledge of ULK1 and its different types of expression behaviour and biological function in cancer, which may shed new light on targeting it and its related proteins in cancer therapies.

Structure of ULK1 and its complex

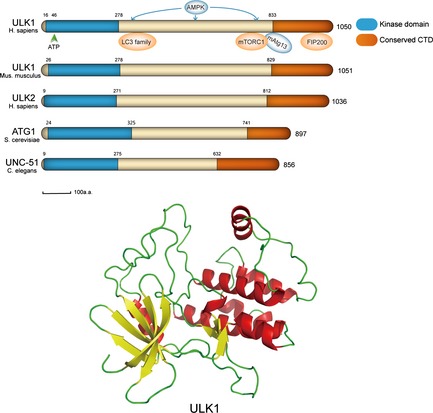

Up to now, the precise three‐dimensional crystalline structure of ULK1 had remained unknown, however, through extensive research, conserved domains of ULK1 in different model organisms have been confirmed (Fig. 2). Human ULK1 has 41% overall similarity to UNC‐51, its Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) homologue, and 29% similarity to Atg1 14. In contrast to other Atg1/UNC‐51‐related kinases, ULK3, ULK4 and STK36, the similarity between ULK1 and Atg1 is not restricted to the N‐terminal catalytic domain but extends over the entire protein, including central proline/serine‐rich (PS) and C‐terminal domains (CTD) 15, 16.

Figure 2.

Identity of UNC51‐like kinase 1 in Homo sapiens compared to its homologues in other model organisms.

UNC51‐like kinase 1 in Homo sapiens has an N‐terminal kinase domain(residue 16–278)and a CTD (residue 833–1050), highly conserved to its homologous proteins in both yeast and C. elegans. Between kinase domain and CTD is a serine/proline‐rich region, the site for many post‐translational modifications 17. ULK2, a further homologue of Atg1 in mammals, has 52% overall amino acid identity with ULK1 7; and formerly it was believed to play essential roles in initial steps of autophagosome formation 13. However, via an RNAi‐based screen, ULK1, not ULK2, was identified to be the one involved in mammalian autophagy, as an essential component for amino acid starvation‐induced autophagy in HEK293 cells 18. Furthermore, the highly conserved CTD domain is speculated to carry out important functions. Autophosphorylation testing and conformational changes involving exposure of the CTD and mapping the regions that direct membrane association and interaction with the putative human homologue of Atg13 in HEK293 cell systems, a seven‐residue motif within the CTD was confirmed to be needed in the dominant‐negative activity of kinase‐dead mutants. Such results indicated that CTD affected ULK1 kinase function that it does not bind to mAtg13, indicating that it may interact with further autophagy proteins 19. In addition, siRNA screening results have identified that deletion of the PDZ domain‐binding Val–Tyr–Ala motif at the ULK1 C terminus, may generate a more potent dominant‐negative protein, providing evidence for multiple function modules of ULK1.

Thus by its sharing high sequence identity and similarity, specially in the kinase domain, ULK1 plays similar roles in mammalian autophagy compared to its homologue in other organisms, such as Atg1 or UNC‐51. It has also been confirmed that they all function by forming complexes rather than by reacting alone 20. Yet, differences between Atg1 as first studied and its mammalian homologue ULK1, still exist. In yeast, Atg1 forms a complex with Atg13 and Atg17; in mammals, the Atg1 homologue and that of Atg13 have been identified, – ULK1 and mAtg13. However, no homologue of Atg17 has been found in mammals. In 2008, one result identified the focal adhesion kinase family‐interacting protein of 200 KDa (FIP200) as an essential factor for the initial step of autophagosome generation – this can interact with ULK1. Thus, speculation that FIP200 might be the autophagy‐specific binding partner of ULK1 and functional counterpart of Atg17 has been suggested 21. Further, it has been confirmed that ULK1 forms at least a quadruple complex with mAtg13, FIP200 and Atg101. These react together in downstream signalling. mAtg13 ULK1‐binding sites have been mapped to C‐terminal regions containing residues 829–1051 22, 23. In addition, mAtg13 not only binds to ULK1 but also interacts with FIP200. Furthermore, human Atg13‐interacting protein, Atg101, has been identified on mAtg13, indicating that mAtg13, FIP200 and Atg101 can function in a ULK1‐independent manner. Whether any of them can function independently to autophagy induction remains unknown at present 24.

For this complex, one of the major functions is to regulate ULK1 kinase activity; either can do so alone in the absence of the other, however, maximal stimulation of ULK1 activity requires both. On the other hand, both ATG13 and FIP200 are required for ULK1 localization to the isolation membrane, and absence of either prevents correct localization of ULK1 24, indicating that this complex is essential for autophagy‐induced ULK1 translocation. Atg101 binding to mAtg13 is essential for autophagy and interacts with ULK1 in an Atg13‐dependent manner.

Expression, transcriptional regulation and post‐translation modifications of ULK1

UNC51‐like kinase 1 is a ubiquitously expressed protein kinase localized to autophagosomal membranes in mammalian cells and shows no special patterns in normal tissues 25. Dominant‐negative mutants of ULK1 block autophagy, indicating that ULK1 is an obligatory protein kinase 26. By northern blot analysis, ULK1 mRNA has been detected as multiple bands in heart, brain, spleen, lung, liver and skeletal muscle at varying degrees, indicating that the ubiquitously expressed genes exist in a wide variety of adult tissues, as does its mammalian homologue, ULK2 6, 7. In addition, the single ULK1 transcript has been detected to be 4.7kb 6.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) can regulate expression of ULK1. In C2C12 myoblasts it has been revealed that two members of the miR‐17 family, miR‐20a and miR‐106b, participate in regulating leucine deprivation‐induced autophagy by suppressing ULK1 expression 27. Leucine deprivation down‐regulates miR‐20a and miR‐106b expression by suppression of their c‐Myc transcription factor. Treatment of C2C12 cells with miR‐20a or miR‐106b mimic reduced endogenous ULK1 protein levels 27, and under chronic nutrient deprivation, miR‐290–295 cluster is strongly up‐regulated in melanoma cells, whose over‐expression confers resistance to glucose starvation. Besides ULK1, a further Atg protein, Atg7, mediates miR‐290–295‐induced down‐regulation 28.

Compared to normal cells, expression of ULK1 in some types of malignant cell can vary, including those of breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and melanoma. It has been observed in human breast cancer, that mRNA and protein levels of ULK1 are low, and statistical analysis has shown that ULK1 expression negatively correlated with tumour size, lymph node status and pathological stage 16. Significant positive correlation between expression of ULK1 and LC3A has been observed in a breast cancer cohort, as well as a significant negative correlation between expression of ULK1 and p62, suggesting that reduced expression of ULK1 is associated with breast cancer progression and decreased autophagic capacity 29. In HCC, expression of ULK1 in adjacent peritumoural tissue has been seen to be lower than in HCC tissues; this was significantly associated with tumour size 30. Furthermore, in basal cell carcinoma, expression level of ULK1 and a further neuronal differentiation marker, ARC, was up‐regulated by overexpression GLI1, in human keratinocytes 31.

In circumstances of severe hypoxia, expression levels also change by regulation of different signals. For instance, mRNA and protein expressions are transcriptionally up‐regulated by activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) in hypoxia. To protect cells from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress caused by severe hypoxia, ULK1 is also required for the integrated stress response, and ablation of ULK1 causes caspase‐3/7‐independent cell death 32.

As reviewed previously, in early stages of autophagy, three major groups, including Atg1 complex, are involved in the core machinery of enabling localization of Atg proteins to the pre‐autophagosomal structure (PAS) 33. Up to now, no such evidence proving the existence of PAS in mammals has been shown, however, due to homology of ULK1 and Atg1, ULK–Atg13–FIP200 complex (>1 MDa) is suspected of possessing the same function. It is directly regulated by some important stress sensors, such as mammalian TOR complex 1(mTORC1) and AMPK 34. Under normal growth conditions, AMPK remains inactive, while mTORC1 associates with the ULK1/2–Atg13–FIP200 complex via direct interaction between raptor and ULK1, and active mTOR phosphorylates mAtg13 and ULK1, suppressing ULK1 complex activity 34, 35. When the ATP/AMP ratio decreases, AMPK is activated and can regulate autophagy induction by inhibition of mTORC1, or via the TSC1/2‐Rheb pathway 36, 37. Interactions between AMPK, mTORC1 and ULK complex conducted through phosphorylating mTORC1, also preventing phosphorylation between mTORC1 and ULK1. It has also been revealed that AMPK and ULK1 complex can directly interact in a mTORC1‐deficient conditions 38, proving a direct regulation relationship between ULK1 and AMPK. Considering these above results and the crucial role of ULK1 and its related complex in the autophagic process, it is easy to speculate that ULK1 has intricate post‐translational modification. Several studies have been conducted to determine different types of modification behaviour and their specialized sites. Recently, including phosphorylation, ubiquitination and acetylation, many modification experiments have been carried out (Table 1).

Table 1.

Post‐translational modifications of and by the UNC51‐like kinase 1 (ULK1) complex in autophagy

| Substrate | Modification | Site | Modifying enzyme | Effect in autophagy | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ULK1 | P | Ser317 | AMPK | Direct activating ULK1 in a mTOR‐independent manner | 81 |

| Thr575 | |||||

| Ser555 | |||||

| Ser777 | |||||

| P | Ser757 | mTOR | Prevent ULK1 action & disrupting the interaction between ULK1 and AMPK | 37, 81 | |

| Ser638 | |||||

| Ser758 | |||||

| P | Ser774 | Akt | 37 | ||

| P | Thr180 | ULK1 | Autophosphorylation to form the kinase‐activation loop | 37 | |

| P | C‐terminal regions residues 829–1051 | mAtg13 | Binding with ULK1 | 41, 54 | |

| P | C‐terminal regions residues 651–1051 | FIP200 | |||

| Ac | Lys162 | Tip60 | Active ULK1 in serum starvation | ||

| Lys606 | 53 | ||||

| Ub | Unknown | TRAF6 | AMBRA1, interacting with the E3‐ligase TRAF6, supports ULK1 ubiquitylation by LYS‐63‐linked chains | 53, 82 | |

| AMPK | P | Thr172 | ULK1 | Decreased the starvation induced activation of AMPK (Feedback mechanisms) | 37, 44 |

| AMBRA1 | P | Ser52 | mTOR | Inhibit AMBRA1 by phosphorylation, whereas on autophagy induction | 52 |

| AMBRA1 | P | Unknown | ULK1 | The cross‐talk between ULK1 and Beclin‐1 complexes | 52 |

| FIP200 | P | Unknown | ULK1 | Binding with ULK1 | 41, 54 |

| Raptor | P | Ser855 | Inactivating mTORC1 | 83 | |

| Ser859 | ULK1 | ||||

| Ser863 | |||||

| Ser792 | |||||

| mTOR | P | Ser2481 | ULK1 | Induced by ULK1 | 83 |

| mAtg13 | P | C‐terminal residues 384–517 | ULK1 | Binding with ULK1 | 41, 54 |

| Sqa (ZIPK homology) | P | Thr194 | ULK1 | Phosphorylation of Sqa at Thr‐279 is required for Atg1‐mediated myosin II activation | 59 |

| Thr239 | ULK1 | ||||

| Thr279 | ULK1 | ||||

| ZIPK | P | Unknown | ULK1 | May process the same function of Atg1 acting with Sqa. | 59 |

| Beclin‐1 | P | Ser14 | ULK1 | Enhance the activity of the Atg14L‐containing VPS34 complexes | 58 |

ULK1 regulation network in cancer

Previous studies have indicated that ULK1 is a good potential target for cancer therapy. Autophagy has both tumour‐suppressive and cancer‐promoting functions. Generally, once a tumour has formed, autophagy becomes detrimental to the host as it enables tumour cells to survive energy deprivation and other stresses. Thus, one way to treat cancer would be to inhibit autophagy in its cells. ULKs, as targets needed in the autophagic pathway, are required for inhibition of autophagy. Previous studies have shown that activating ULK1 up‐regulates tumour‐protective autophagy. Transcriptional up‐regulation of ULK1 can also proceed via TP53‐independent pathways, also presumably allowing for sustained autophagy in cells deficient in TP53 17. ULK1 thus could be a good potential target.

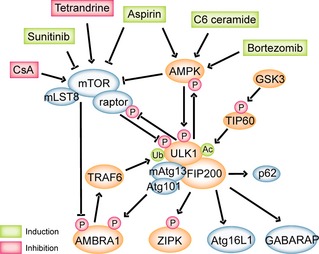

Living cells are adaptive self‐sustaining systems; this depends strictly on supply of nutrients, energy and oxygen from outside. Autophagy functions to answer stress, in which autophagosome formation is the key event. In yeast, the process consists of several functional units: Atg1 and its regulators, PI3K complex, Atg9, Atg2–Atg18 complex, and two ubiquitin‐like conjugation systems. In the first, Atg12 is conjugated to Atg5 resulting in formation of a complex consisting of the Atg12–Atg5 conjugate and Atg16L. This complex is in turn required for conjugation of ATG8 family proteins to phosphatidylethanolamine on the phagophore membrane 39 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Regulation network of UNC51‐like kinase 1 (ULK1) in autophagy, and compounds targeting different signalling pathways. AMPK and mTOR are important upstream regulators of ULK1; they are both capable of sensing energy or nutrient stresses and regulate activation of ULK1 through phosphorylation at different sites. ULK1, mAtg13, FIP200 and Atg101 form a complex in the network, and deprivation of any leads to termination of autophagy, indicating the essential function of ULK1 complex. Activated ULK1 complex has multiple downstream signals, including AMBRA1, ZIPK, Atg16L1 and GABARAP. AMBRA1 can activate a further Beclin‐1 complex, also necessary for autophagy. ZIPK phosphorylation site by ULK1 has not yet been identified, but its homologue in yeast, Sqa, can be activated by Atg1, resulting in activation of myosin II. Atg16L1 participates in ubiquitin‐like conjugation system, functioning in elongation of the isolation membrane with Atg5 and Atg12. In this network, it can be phosphorylated by FIP200 and pass the signal to Atg5. A further ubiquitin‐like conjugation system can be regulated by ULK1 complex through the LIR motif of the LC3 and GABARAP subfamily.

AMPK, a crucial upstream regulator of ULK1, has initially been identified as a serine/threonine kinase that negatively regulates several key enzymes of lipid anabolism, and it is the major energy‐sensing kinase that activates a whole variety of catabolic processes in multicellular organisms, such as glucose uptake and general metabolism 40. When facing glucose starvation, ULK1 becomes significantly activated through AMPK‐dependent phosphorylation; by testing activation of ULK1 under the treatment of different substrates of AMPK, or suppresser of AMPK, during glucose starvation 41. Results showed that AMPK pre‐treatment significantly increased ULK1 kinase activity and reduced ULK1 mobility, while AMPK did not activate ULK1 in the absence of ATP or in the presence of the AMPK inhibitor. This indicates that AMPK directly phosphorylated and activated ULK1 in glucose starvation. As reviewed previously, we can conjecture autophagosome formation status by observing activation of LC3‐II; in one type of autophagy induction amino acid starvation study, LC3‐II was induced with GFP‐LC3 puncta formation; autophosphorylation activity of ULK1 was greatly increased, and activation of AMPK was lower than in glucose starvation 42. ULK1 regulated autophagy in an AMPK‐dependent and AMPK‐independent way, proving that LC3‐II could be an important marker and may indicate the activity of ULK1. And as mentioned previously, mTORC1 regulates ULK1 and mAtg13 to keep them inactive through phosphorylation, identifying its essential role in autophagy. mTOR and its homologues were first discovered in yeast as TOR (target of rapamycin), and under treatment of rapamycin, TOR functioned to hyperphosphorylate Atg13, therefore regulating ULK1 43. mTORC1 is an mTOR‐related complex, formed by mTOR, raptor and mLST8 44; activity of mTORC1 depends on diverse positive signals such as high‐energy levels, normoxia, presence of amino acids or growth factors that all result in inhibition of autophagy 45. In addition to the AMPK/ULK1 pathway, the AMPK/mTORC1/ULK1 pathway is a further major autophagic system, specially in nutrient starvation. While activated under low‐energy conditions, AMPK possesses at least two different mechanisms to release mTORC1‐mediated repression. AMPK can directly phosphorylate mTORC1 to repress its activation, but activated AMPK inhibits mTORC1 activity primarily mainly by phosphorylation and activation of the negative regulator tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2); thus TSC2 is able to suppress the mTORC1 complex by inactivating Rheb 46. While under normal conditions, growth factors activate the PI3K/Akt pathway by binding with receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK), before Akt being recruited to the plasma membrane and activated through phosphorylation by PDK1. Activated Akt in turn phosphorylates TSC2, which serves as a GTPase‐activating protein (GAP) and inactivates small GTPase Rheb; subsequently, allowing Rheb to directly activate mTORC1 47, 48.

Compared to the counterpart of mTOR and ULK1 complex in yeast, Atg1–Atg13–Atg17 and TOR, is largely unaffected by nutrient status. Under normal growth conditions, mTORC1 associates with the ULK1–Atg13–FIP200 complex, by direct interaction between raptor and ULK1 34. Active mTOR phosphorylates mAtg13 and Ulk1, thereby suppressing ULK1 kinase activity. Under starvation conditions or when mTORC1 activity is pharmacologically inhibited, these sites are rapidly dephosphorylated by yet unknown phosphatases 23. Using stable isotope labelling with amino acids in cell culture, several serine and threonine residues have been identified in human ULK1, whose phosphorylation is reduced after starvation, including S638 and S758 49.

Apart from mTORC1 and AMPK, p53 also has the capacity to integrate stress‐related pathways and transmit them to the complex. p53 is known to be both a negative and positive regulator of autophagy 50, and upon DNA damage, ULK1 and ULK2 have additionally been identified as transcriptional targets of p53 51. A further study confirmed that cytoplasmic p53 can negatively regulate autophagy by its ability to directly interact with FIP200 52.

In metazoans, cells depend on extracellular growth factors for energy homoeostasis, and glucose and growth factor deprivation can lead to activation of ULK1 by acetylation. In this pathway, GSK3 (glycogen synthase kinase‐3) is activated by removal of inhibitory Ser9 phosphorylation upon withdrawal of growth factors. Activated GSK3 catalyses phosphorylation of TIP60 (HIV‐1 Tat interactive protein, 60 kDa) at Ser86, which depends on prior phosphorylation at Ser90, and results in higher affinity of TIP60 for ULK1 and increased acetylation and kinase activity of ULK1 53. In the HCT116 cell line, cells engineered to express TIP60‐S86A that cannot be phosphorylated by GSK3 did not undergo serum deprivation‐induced autophagy, and acetylation‐defective mutant of ULK1 failed to rescue autophagy in ULK1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts. These findings uncover an activating pathway that integrates protein phosphorylation and acetylation to connect growth factor deprivation to autophagy 54.

Sensing upstream signalling, the ULK1/2–Atg13–FIP200 complex reacts together, and passing the downstream signal. ULK1 forms a triple complex with Atg13 and FIP200. It has been discovered that Atg13 not only binds with ULK1 but also interacts with FIP200, and Atg13 and FIP200 can function in a ULK1‐independent manner 55, 56.

Downstream signalling of the ULK1/2–mAtg13–FIP200 complex is not yet fully understood, but existing studies have revealed multiple mechanisms. One report suggests that Ulk1 directly phosphorylates AMBRA1 (a Beclin1‐interacting protein and regulatory component of the PI3K class III complex); the latter associates with dynein motor complex via direct interaction between AMBRA1 and dynein light chain 1 (DLC1) 57. Upon starvation, activated ULK1 phosphorylates AMBRA1; thereupon, the PI3K complex is released and translocates to the ER, where it initiates autophagosome formation 58. However, besides the AMBRA1 pathway, ULK1 can directly phosphorylate Beclin‐1 on Ser14, thereby enhancing activity of Atg14L‐containing VPS34 complexes and autophagy induction 59.

Further reports have revealed that dAtg1 and ULK1 are able to regulate the actin motor protein myosin II 60. In Drosophila, ULK1 directly phosphorylates and activates zipper‐interacting protein kinase (ZIPK, also known as DAPK3), attenuated myosin II activation and starvation‐induced autophagy 47. Notably, ZIPK knockdown and myosin II inhibition, in addition, significantly inhibit redistribution of mAtg9 from the trans‐Golgi network (TGN) to a peripheral pool upon starvation 47. In response to nutrient deprivation, ULK1‐ and Atg13‐dependent cycling causes the movement of transmembrane protein mAtg9 61, 62. Although mAtg9 is essential for autophagy induction, its exact function still remains unknown. However, it has been suggested that shuttling of mAtg9 from the Golgi apparatus helps provide membranes for newly formed autophagosomes 48. These two mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, as ULK1 might act at several stages of autophagy initiation and regulate both mAtg9 trafficking and recruitment of PI3K class III complex to the ER, to initiate autophagosome generation.

In addition, ULK1 can function with the Atg8 family in mammals. Conjugation of Atg8 to phosphatidylethanolamine has been suggested to drive elongation of the phagophore 63. Mammals have at least seven Atg8 family members, LC3A–C, with two isoforms of LC3A, GABARAP and GABARAPL1–2 64. Both LC3 and GABARAP subfamily members are conjugated to the phagophore 65, 66. ULK1 has previously been found to interact with GABARAP and GABARAPL2,and studies have revealed that these interactions are dependent on the LIR (LC3‐interaction region) motif of ULK1 to regulate elongation of the phagophore, suggesting a role for ULK1 in later steps of autophagosome formation 67.

Furthermore, in mitophagy, loss of AMPK or ULK1 may result in aberrant accumulation of autophagy adaptor p62, which may function in the degradation stage of autophagy. Moreover, this study observed autophagy in cells with mutant ULK1 that cannot be phosphorylated by AMPK showing defective mitophagy, revealing that such phosphorylation of AMPK and ULK1 is required for mitochondrial homoeostasis and cell survival, following starvation 68. During mitophagy, ULK1 interacts with FUNDC1, phosphorylating it at serine 17 at mitochondria, which enhances FUNDC1 binding to LC3, while FUNDC1 can regulate ULK1 recruitment to damaged mitochondria, where FUNDC1 phosphorylation by ULK1 is crucial for mitophagy 69. Recent study also revealed that ULK1‐ and Atg13‐mediated mitophagy are regulated by the Hsp90–Cdc37 chaperone complex, which co‐ordinately regulates activity of select kinases to orchestrate many facets of the stress response. Although the relationship between Hsp90–Cdc37 and autophagy has not yet been well characterized, it was verified the interaction between ULK1 and Hsp90–Cdc37 stabilized and activated ULK1, which in turn is required for phosphorylation and release of Atg13 from ULK1, and for recruitment of Atg13 to damaged mitochondria for efficient mitochondrial clearance 70.

Interestingly, a recent study in Arabidopsis also showed that Atg1 and Atg13 are both regulators and targets of autophagy. Levels of Atg1 and Arg13 phosphor‐proteins dropped dramatically during nutrient starvation and rose again upon nutrient addition; this turnover was abrogated by inhibition of the Atg system, indicating that Atg1/13 complex became a target of autophagy 71. The mammalian homologue of Atg1, ULK1 may also be the target of autophagy by as yet unknown mechanisms.

Likewise, regulation of ULK1 resembles other stable systems, by being dependent on negative feedback loops to retain internal control. As indicated above, AMPK activates ULK1 by direct phosphorylation, and consistent with this, activated ULK1 directly phosphorylates AMPK and inhibits its activation. In addition to AMPK, a negative‐feedback loop also emerges between mTORC1 and ULK1; several studies have indicated that both phosphorylations of raptor are strongly enhanced after overexpression of ULK1 by direct phosphorylation of raptor at numerous sites 72; one of these residues (T792) is the above mentioned effector site through which AMPK negatively regulates mTORC1 activity 73. Multiple ULK1‐dependent phosphorylation of raptor, which either results in direct inhibition of mTORC1 kinase activity 74 or interferes with raptor–substrate interaction 44, thus finally leads to reduced phosphorylation of mTORC1 downstream targets.

Potential therapeutic applications of ULK1 in cancer

Autophagy has a two‐side role in respect to multiple diseases, specially cancer, as it can be of interest in both cell proliferation and its suppression. The relationship between autophagy and cancer is complicated; cell survival inhibition is beneficial to treat cancer, and cell death by autophagy induction can be beneficial for the patient. When a tumour has been formed, a cell‐survival trait of autophagy enables tumour cells to survive during stress, such as nutrient deprivation, hypoxia and others. Thus, to inhibit autophagy may be a valuable strategy to prevent tumour growth, and many positive regulators of autophagy function as tumour suppressors 75. For example, rapamycin may target mTORC1 76, while tamoxifen can aim at Beclin‐1 77. As ULK1 can regulate initial steps of induction and can transduce upstream sensors to downstream pathways of autophagy, it has long been speculated to be a potent target of cancer therapy. Also, studies on ULK1 function to promote cancer cell viability have been conducted. In primary human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), ULK1 enrichment was observed in hypoxic tumour regions, that is, high enrichment of ULK1 was associated with a high hypoxic fraction 78. In contrast, a log‐rank test indicated that cancer patients with lower levels of ULK1 had a significantly shorter, distant metastasis‐free survival time and cancer‐related survival time 79. Study into the dual role ULK1 plays in cancer have revealed that it is a complicated, but potent target toward potential cancer therapies.

Many existing compounds can influence autophagy by targeting different parts of the ULK1 complex and autophagy network. A new role for phospholipase D (PLD) has been demonstrated as an autophagic regulator, whose inhibition enhances autophagic flux via ULK1, ATG5 and ATG7. PLD also suppresses autophagy by differentially modulating phosphorylation of ULK1 mediated by mTOR and AMPK 80, which inhibit regression of cancer cells. Studies also conducted in SAS human oral cancer cells have shown that tetrandrine can trigger autophagy to reduce cell viability by increasing levels of several targets, such as p‐ULK1 and p‐mTOR. Tithonia diversifolia methanolic extract, a representative natural product, increases expression of ULK1 and LC3II, inducing human glioblastoma U373 cell death, depending upon autophagy. Recently, with increased attention of therapeutic approaches through targeting ULK1 to regulate tumour growth or other cancer hallmarks, many compounds have been verified to regulate the ULK1 complex and its network in autophagy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Different actions targeting UNC51‐like kinase 1 (ULK1) in cancer cells

| Compounds | Target in autophagy | Cancer cell type | Effects in cancer | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthricin | mTOR | Breast cancer MCF7 and MDA‐MB‐231 cell | Inhibition of cell growth and genetic deletion of ULK1 and can accelerate anthricin‐induced apoptosis | 87 |

| Tetrandrine | LC‐3 II, Atg‐5, beclin‐1, p‐S6, p‐ULK, p‐mTOR, p‐Akt (S473) and raptor | SAS human oral cancer cells | Induce the levels of targets and decreased cell viability | 88 |

| Bortezomib | AMPK | PANC‐1 pancreatic cancer cells and HT‐29 colorectal cancer cells | Induce protective autophagy through AMPK activation, followed by regulating ULK1 | 89 |

| Phospholipase D | ATG1 (ULK1), ATG5, ATG7,mTOR, AMPK | Several cancer cells | Inhibit the regression of cancer cells through ULK1 complex and Beclin‐1 complex | 78 |

| C6 ceramide | AMPK/ULK1 signalling | Colorectal cancer HT‐29 cell | Induce cytotoxic effects and activate AMPK/Ulk1 signalling | 90 |

| Deguelin | AMPK & Hsp‐90 | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Inhibit Akt signalling by activating AMPK and disrupt Cdk4's association with Hsp‐90 expressions | 91 |

| Sunitinib | mTORC1 signalling | Rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells | Induce ULK1 expression through inhibiting mTORC1 signalling | 92 |

| Cyclosporine A (CsA, an immunophilin/calcineurin inhibitor) | ER mTOR/p70S6K1 | Malignant gliomas | Induction of ER stress and inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K1 pathway | |

| mTOR | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Up‐regulate mTOR in 50% | 93 | |

| Aspirin | mTOR & AMPK | Colorectal cancer | Inhibit mTOR signalling and activate AMPK | 94 |

| Cisplatin | ΔNp63α | Squamous cell carcinoma cells | Transcriptional regulate Atg proteins including ULK1 | 1 |

| Tithonia diversifolia methanolic extract | PARP, p‐p38, ULK1, and LC3‐II expression | human glioblastoma U373 cells | Induce U373 cell death dependent upon autophagy | 95 |

In addition, expression of ULK1 has remarkable differences between cancers and normal tissues, thus it can not only function as a therapeutic target but also as a diagnostic biomarker. For example, in breast cancer, the reduced expression of ULK1 is associated with tumour progression, together with closely related to reduced autophagic capacity, and multivariate Cox regression analysis, it was found that ULK1 expression was recognized to be an independent prognostic factor 16. Furthermore, hypoxia in the microenvironment of many solid tumours is an important determinant of malignant progression, which may up‐regulate ULK1 expression in breast cancer 17. With more research into ULK1 expression level in different cancers, as a biomarker it has potential uses in cancer diagnosis.

Conclusions

The ULK1 complex is part of a key process in initiation of autophagy in response to different stresses; it is highly regulated through post‐translational modification and protein–protein interactions. Homologues of Atg1, ULK1 and ULK2 were identified in the 1990s, the study of ULK1 gradually burgeoning. Recent studies have revealed different mechanism in ULK1‐regulated autophagy, such as existence of AMPK‐ or mTORC1‐independent induction of ULK1 complex, and function of the novel‐related protein Atg101.

Different expression and biological function in cancer cells have indicated ULK1 to be a novel target for cancer diagnose or therapy. Dissimilar mechanisms involved in triggering autophagy and regulating autophagosome formation have offered researchers multiple choices for targeting ULK1 or its related network in cancer therapy. As reviewed, numerous published results have indcated the feasibility of targeting ULK1 complex for cancer therapy, and there exist various compounds that express their function for cancers by targeting ULK1 (Table 3). Although not mentioned here, besides cancer, there are further diseases for which it is thought that therapies targeting ULK1will be useful. Still, there are many important Atg proteins which function or interact with mechanisms of ULK1, which are not yet fully characterized. However, the essential roles ULK1 plays in autophagy and its dual role in cancer therapy, its potential role will play an important part in future cancer drug design or diagnosis biomarkers. We firmly believe that more comprehensive understanding of ULK1 will be made recently, and it will help us specifically target ULK1 complex function in cancer treatment.

Table 3.

The effects of different compounds targeting UNC51‐like kinase 1 (ULK1) and its related protein in cancer cells

| Target mechanism in autophagy | Cancer cell type | Effects in cancer | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional knockout of FIP200 | Mouse model of human breast cancer cells | Suppress mammary tumourigenesis and progression | 84 |

| Depletion of ULK1 | Melanoma MVT‐1 cells | Increase melanin production by elevating mRNA levels of MITF and tyrosinase | 85 |

| Overexpression of GLI1 in human keratinocytes | Basal cell carcinoma | Increase expression of the neuronal differentiation markers ARC and ULK1 | 86 |

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Key Projects of the National Science and Technology Pillar Program (no. 2012BAI30B02), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos U1170302, 81473091, 81260628, 81303270 and 81402496).

References

- 1. Liu B, Cheng Y, Liu QA, Bao JK, Yang JM (2010) Autophagic pathways as new targets for cancer drug development. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 31, 1154–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ (2008) Autophagy fights disease through cellular self‐digestion. Nature 451, 1069–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. He CC, Klionsky DJ (2009) Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 67–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wen X, Wu JM, Wang FT, Liu B, Huang CH, Wei YQ (2013) Deconvoluting the role of reactive oxygen species and autophagy in human diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 65, 402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chan EY, Tooze SA (2009) Evolution of Atg1 function and regulation. Autophagy 5, 758–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kawamata T, Kamada Y, Kabeya Y, Sekito T, Ohsumi Y (2008) Organization of the pre‐autophagosomal structure responsible for autophagosome formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2039–2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saitoh T, Fujita N, Hayashi T, Takahara K, Satoh T, Lee H et al (2009) Atg9a controls dsDNA‐driven dynamic translocation of STING and the innate immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 20842–20846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alemu EA, Lamark T, Torgersen KM, Birgisdottir AB, Larsen KB, Jain A et al (2012) ATG8 family proteins act as scaffolds for assembly of the ULK complex sequence requirements for LC3‐interacting region (LIR) motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hara T, Takamura A, Kishi C, Iemura SI, Natsume T, Guan JL et al (2008) FIP200, a ULK‐interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 181, 497–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang ZF, Klionsky DJ (2010) Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 124–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Noda T, Fujita N, Yoshimori T (2008) The Ubi brothers reunited. Autophagy 4, 540–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weidberg H, Shvets E, Elazar Z (2011) Biogenesis and Cargo Selectivity of Autophagosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 125–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Klionsky DJ, Abeliovich H, Agostinis P, Agrawal DK, Aliev G, Askew DS et al (2008) Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy 4, 151–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuroyanagi H, Yan J, Seki N, Yamanouchi Y, Suzuki Y, Takano T et al (1998) Human ULK1, a novel serine/threonine kinase related to UNC‐51 kinase of Caenorhabditis elegans: CDNA cloning, expression, and chromosomal assignment. Genomics 51, 76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yan J, Kuroyanagi H, Kuroiwa A, Matsuda Y, Tokumitsu H, Tomoda T et al (1998) Identification of mouse ULK1, a novel protein kinase structurally related to C‐elegans UNC‐51. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 246, 222–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yan J, Kuroyanagi H, Tomemori T, Okazaki N, Asato K, Matsuda Y et al (1999) Mouse ULK2, a novel member of the UNC‐51‐like protein kinases: unique features of functional domains. Oncogene 18, 5850–5859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wong PM, Puente C, Ganley IG, Jiang XJ (2013) The ULK1 complex Sensing nutrient signals for autophagy activation. Autophagy 9, 124–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chan EYW, Kir S, Tooze SA (2007) SiRNA screening of the kinome identifies ULK1 as a multidomain modulator of autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 25464–25474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chan EYW, Longatti A, McKnight NC, Tooze SA (2009) Kinase‐inactivated ULK proteins inhibit autophagy via their conserved C‐terminal domains using an Atg13‐independent mechanism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 157–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu B, Cheng Y, Yang J‐M. (2013) Autophagy in Health and Disease, Chapter 10, Drug Discovery in the Autophagy Pathways. Gottlieb R, eds. Boston, USA: Academic Press, Elsevier, 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hara T, Mizushima N (2009) Role of ULK‐FIP200 complex in mammalian autophagy FIP200, a counterpart of yeast Atg 17? Autophagy 5, 85–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ganley IG, Lam DH, Wang JR, Ding XJ, Chen S, Jiang XJ (2009) ULK1 center dot ATG13 center dot FIP200 complex mediates mTOR signaling and is essential for autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12297–12305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alers S, Loffler AS, Paasch F, Dieterle AM, Keppeler H, Lauber K et al (2011) Atg13 and FIP200 act independently of Ulk1 and Ulk2 in autophagy induction. Autophagy 7, 1424–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hosokawa N, Hara T, Kaizuka T, Kishi C, Takamura A, Miura Y et al (2009) Nutrient‐dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1‐Atg13‐FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1981–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fu L‐l, Xie T, Zhang S‐Y, Liu B (2013) Eukaryotic elongation factor‐2 kinase (eEF2K): a potential therapeutic target in cancer. Apoptosis 19, 1527–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu B, Ouyang L. (2014) Autophagy, Cancer, Other Pathologies, Inflammation, Immunity, Infection and Aging, Volume 3: Mitophagy, Chapter 18, Involvement of Autophagy and Apoptosis in Studies of Anticancer Drugs. New Jersey, USA: Academic Press, Elsevier; 263–287. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu H, Wang FL, Hu SL, Yin C, Li X, Zhao SH et al (2012) MiR‐20a and miR‐106b negatively regulate autophagy induced by leucine deprivation via suppression of ULK1 expression in C2C12 myoblasts. Cell. Signal. 24, 2179–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen Y, Liersch R, Detmar M (2012) The miR‐290‐295 cluster suppresses autophagic cell death of melanoma cells. Sci. Rep. 2, 808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tang J, Deng R, Luo RZ, Shen GP, Cai MY, Du ZM et al (2012) Low expression of ULK1 is associated with operable breast cancer progression and is an adverse prognostic marker of survival for patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 134, 549–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xu HT, Yu H, Zhang XY, Shen XY, Zhang KH, Sheng HH et al (2013) UNC51‐like kinase 1 as a potential prognostic biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 6, 711–717. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gore SM, Kasper M, Williams T, Regl G, Aberger F, Cerio R et al (2009) Neuronal differentiation in basal cell carcinoma: possible relationship to Hedgehog pathway activation? J. Pathol. 219, 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pike LRG, Singleton DC, Buffa F, Abramczyk O, Phadwal K, Li JL et al (2013) Transcriptional up‐regulation of ULK1 by ATF4 contributes to cancer cell survival. Biochem. J. 449, 389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Suzuki K, Ohsumi Y (2007) Molecular machinery of autophagosome formation in yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae . FEBS Lett. 581, 2156–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fu L‐L, Wen X, Bao J‐K, Liu B (2012) MicroRNA‐modulated autophagic signaling networks in cancer. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 44, 733–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meley D, Bauvy C, Houben‐Weerts J, Dubbelhuis PF, Helmond MTJ, Codogno P et al (2006) AMP‐activated protein kinase and the regulation of autophagic proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34870–34879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Inoki K, Zhu TQ, Guan KL (2003) TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell 115, 577–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bach M, Larance M, James DE, Ramm G (2011) The serine/threonine kinase ULK1 is a target of multiple phosphorylation events. Biochem. J. 440, 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen Y, Fu LL, Wen X, Liu B, Huang J, Wang JH et al (2014) Oncogenic and tumor suppressive roles of microRNAs in apoptosis and autophagy. Apoptosis 19, 1177–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hardie DG (2007) AMP‐activated/SNF1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 774–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL (2011) AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 132–U171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Z‐y Li, Yang Y, Ming M, Liu B (2011) Mitochondrial ROS generation for regulation of autophagic pathways in cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 414, 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y (2011) The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 27, 107–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Valvezan AJ, Huang J, Lengner CJ, Pack M, Klein PS (2014) Oncogenic mutations in adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc) activate mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) in mice and zebrafish. Dis. Model. Mech. 7, 63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alers S, Loffler AS, Wesselborg S, Stork B (2012) Role of AMPK‐mTOR‐Ulk1/2 in the regulation of autophagy: cross talk, shortcuts, and feedbacks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 2–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ouyang L, Shi Z, Zhao S, Wang FT, Zhou TT, Liu B et al (2012) Programmed cell death pathways in cancer: a review of apoptosis, autophagy and programmed necrosis. Cell Prolif. 45, 487–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Huang JX, Manning BD (2009) A complex interplay between Akt, TSC2 and the two mTOR complexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 217–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Long XM, Ortiz‐Vega S, Lin YS, Avruch J (2005) Rheb binding to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is regulated by amino acid sufficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23433–23436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shang LB, Wang XD (2011) AMPK and mTOR coordinate the regulation of Ulk1 and mammalian autophagy initiation. Autophagy 7, 924–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Levine B, Abrams J (2008) p53: the Janus of autophagy? Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 637–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gao W, Shen Z, Shang L, Wang X (2011) Upregulation of human autophagy‐initiation kinase ULK1 by tumor suppressor p53 contributes to DNA‐damage‐induced cell death. Cell Death Differ. 18, 1598–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Morselli E, Shen SS, Ruckenstuhl C, Bauer MA, Marino G, Galluzzi L et al (2011) p53 inhibits autophagy by interacting with the human ortholog of yeast Atg17, RB1CC1/FIP200. Cell Cycle 10, 2763–2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lin SY, Li TY, Liu Q, Zhang CX, Li XT, Chen Y et al (2012) Protein phosphorylation‐acetylation cascade connects growth factor deprivation to autophagy. Autophagy 8, 1385–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lin SY, Li TY, Liu Q, Zhang CX, Li XT, Chen Y et al (2012) GSK3‐TIP60‐ULK1 signaling pathway links growth factor deprivation to autophagy. Science 336, 477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fimia GM, Stoykova A, Romagnoli A, Giunta L, Di Bartolomeo S, Nardacci R et al (2007) Ambra1 regulates autophagy and development of the nervous system. Nature 447, 1121–U1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chen Y, Liu XR, Yin YQ, Lee CJ, Wang FT, Liu HQ et al (2014) Unravelling the multifaceted roles of Atg proteins to improve cancer therapy. Cell Prolif. 47, 105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Di Bartolomeo S, Corazzari M, Nazio F, Oliverio S, Lisi G, Antonioli M et al (2010) The dynamic interaction of AMBRA1 with the dynein motor complex regulates mammalian autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 191, 155–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Russell RC, Tian Y, Yuan HX, Park HW, Chang YY, Kim J et al (2013) ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin‐1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 741–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tang HW, Wang YB, Wang SL, Wu MH, Lin SY, Chen GC (2011) Atg1‐mediated myosin II activation regulates autophagosome formation during starvation‐induced autophagy. EMBO J. 30, 636–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Young ARJ, Chan EYW, Hu XW, Koch R, Crawshaw SG, High S et al (2006) Starvation and ULK1‐dependent cycling of mammalian Atg9 between the TGN and endosomes. J. Cell Sci. 119, 3888–3900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nakatogawa H, Ichimura Y, Ohsumi Y (2007) Atg8, a ubiquitin‐like protein required for autophagosome formation, mediates membrane tethering and hemifusion. Cell 130, 165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Uero T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T et al (2000) LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 19, 5720–5728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Oshitani‐Okamoto S, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T (2004) LC3, GABARAP and GATE16 localize to autophagosomal membrane depending on form‐II formation. J. Cell Sci. 117, 2805–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Okazaki N, Yan J, Yuasa S, Ueno T, Kominami E, Masuho Y et al (2000) Interaction of the Unc‐51‐like kinase and microtubule‐associated protein light chain 3 related proteins in the brain: possible role of vesicular transport in axonal elongation. Mol. Brain Res. 85, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W et al (2011) Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP‐Activated Protein Kinase Connects Energy Sensing to Mitophagy. Science 331, 456–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wu WX, Tian WL, Hu Z, Chen G, Huang L, Li W et al (2014) ULK1 translocates to mitochondria and phosphorylates FUNDC1 to regulate mitophagy. EMBO Rep. 15, 566–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Joo JH, Dorsey FC, Joshi A, Hennessy‐Walters KM, Rose KL, McCastlain K et al (2011) Hsp90‐Cdc37 chaperone complex regulates Ulk1‐and Atg13‐mediated mitophagy. Mol. Cell 43, 572–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Suttangkakul A, Li FQ, Chung T, Vierstra RD (2011) The ATG1/ATG13 protein kinase complex is both a regulator and a target of autophagic recycling in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23, 3761–3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dunlop EA, Hunt DK, Acosta‐Jaquez HA, Fingar DC, Tee AR (2011) ULK1 inhibits mTORC1 signaling, promotes multisite Raptor phosphorylation and hinders substrate binding. Autophagy 7, 737–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS et al (2008) AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 30, 214–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Jung CH, Seo M, Otto NM, Kim DH (2011) ULK1 inhibits the kinase activity of mTORC1 and cell proliferation. Autophagy 7, 1212–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rubinsztein DC, Gestwicki JE, Murphy LO, Klionsky DJ (2007) Potential therapeutic applications of autophagy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 6, 304–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Klionsky DJ, Meijer AJ, Codogno P, Neufeld TP, Scott RC (2005) Autophagy and p70S6 kinase. Autophagy 1, 59–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wienecke R, Fackler I, Linsenmaier U, Mayer K, Licht T, Kretzler M (2006) Antitumoral activity of rapamycin in renal angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 48, E27–E29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Schaaf MBE, Cojocari D, Keulers TG, Jutten B, Starmans MH, de Jong MC et al (2013) The autophagy associated gene, ULK1, promotes tolerance to chronic and acute hypoxia. Radiother. Oncol. 108, 529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jang YH, Choi KY, Min DS (2014) Phospholipase D‐mediated autophagic regulation is a potential target for cancer therapy. Cell Death Differ. 21, 533–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Liu B, Wen X, Cheng Y (2013) Survival or death: disequilibrating the oncogenic and tumor suppressive autophagy in cancer. Cell Death Dis. 4, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Liu J‐J, Lin M, Yu J‐Y, Liu B, Bao J‐K (2011) Targeting apoptotic and autophagic pathways for cancer therapeutics. Cancer Lett. 300, 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wang SY, Yu QJ, Zhang RD, Liu B (2011) Core signaling pathways of survival/death in autophagy‐related cancer networks. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 43, 1263–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Egan DF, Kim J, Shaw RJ, Guan KL (2011) The autophagy initiating kinase ULK1 is regulated via opposing phosphorylation by AMPK and mTOR. Autophagy 7, 645–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Nazio F, Strappazzon F, Antonioli M, Bielli P, Cianfanelli V, Bordi M et al (2013) mTOR inhibits autophagy by controlling ULK1 ubiquitylation, self‐association and function through AMBRA1 and TRAF6. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 406–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wei HJ, Guan JL (2012) Pro‐tumorigenic function of autophagy in mammary oncogenesis. Autophagy 8, 129–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kalie E, Razi M, Tooze SA (2013) ULK1 regulates melanin levels in MNT‐1 cells independently of mTORC1. PLoS One 8, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Fu L‐l, Cheng Y, Liu B (2013) Beclin‐1: autophagic regulator and therapeutic target in cancer. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 45, 921–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jung CH, Kim H, Ahn J, Jung SK, Um MY, Son K‐H et al (2013) Anthricin isolated from Anthriscus sylvestris (L.) Hoffm. Inhibits the growth of breast cancer cells by inhibiting Akt/mTOR signaling, and its apoptotic effects are enhanced by autophagy inhibition. Evid. Based complement. Alternat. Med. 2013, 385219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hau AM, Greenwood JA, Lohr CV, Serrill JD, Proteau PJ, Ganley IG et al (2013) Coibamide A induces mTOR‐independent autophagy and cell Death in human glioblastoma cells. PLoS One 8, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Fu LL, Zhao X, Xu HL, Wen X, Wang SY, Liu B et al (2012) Identification of microRNA‐regulated autophagic pathways in plant lectin‐induced cancer cell death. Cell Prolif. 45, 477–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Min H, Xu M, Chen Z‐R, Zhou J‐D, Huang M, Zheng K et al (2014) Bortezomib induces protective autophagy through AMP‐activated protein kinase activation in cultured pancreatic and colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 74, 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Huo HZ, Wang B, Qin J, Guo SY, Liu WY, Gu Y (2013) AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK)/Ulk1‐dependent autophagic pathway contributes to C6 ceramide‐induced cytotoxic effects in cultured colorectal cancer HT‐29 cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 378, 171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Yang YL, Ji C, Bi ZG, Lu CC, Wang R, Gu B et al (2013) Deguelin induces both apoptosis and autophagy in cultured head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. PLoS One 8, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ikeda T, Ishii K, Saito Y, Miura M, Otagiri A, Kawakami Y et al (2013) Inhibition of autophagy enhances sunitinib‐induced cytotoxicity in rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 121, 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Thomas HE, Mercer CA, Carnevalli LS, Park J, Andersen JB, Conner EA et al (2012) mTOR inhibitors synergize on regression, reversal of gene expression, and autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Din FVN, Valanciute A, Houde VP, Zibrova D, Green KA, Sakamoto K et al (2012) Aspirin inhibits mTOR signaling, activates AMP‐activated protein kinase, and induces autophagy in colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology 142, 1504–15.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Huang YP, Guerrero‐Preston R, Ratovitski EA (2012) Phospho‐Delta Np63 alpha‐dependent regulation of autophagic signaling through transcription and micro‐RNA modulation. Cell Cycle 11, 1247–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Lee MY, Liao MH, Tsai YN, Chiu KH, Wen HC (2011) Identification and anti‐human glioblastoma activity of tagitinin C from tithonia diversifolia methanolic extract. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 2347–2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Troncoso RL, Díaz‐Elizondo J, Espinoza SP, Navarro‐Marquez MF, Oyarzún AP, Riquelme JA et al (2013) Regulation of cardiac autophagy by insulin‐like growth factor 1. IUBMB Life 65, 593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]