Abstract

Objectives

Osteosarcoma (OS) is one of the most common primary malignant bone tumours of childhood and adolescence, and is characterized by high propensity for metastasis (specially to the lung), which is the main cause of death. However, molecular mechanisms underlying metastasis of OS are still poorly understood.

Materials and methods

Metadherin (MTDH) was identified to be significantly upregulated in OS tissues that had metastasized compared to OS without metastasis, using a two‐dimensional approach of electrophoresis, coupled with mass spectrometry. To understand the function of MTDH in OS, OS cell lines U2OS and SOSP‐M were transfected with retroviral shRNA vector against MTDH.

Results

It was found that metastatic propensity as well as cell proliferation were significantly reduced in both U2OS and SOSP‐M. Migration and invasion of U2OS and SOSP‐M cells were significantly lower after knock‐down of MTDH. In addition, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) was reduced after knock‐down of MTDH. Clinicopathologically, overexpression of MTDH was significantly associated with metastasis and poor survival of patients with OS.

Conclusion

Taken together, our results demonstrate that MTDH mediated metastasis of OS through regulating EMT. This could be an ideal therapeutic target against metastasis of OS.

Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS) is one of the most common primary malignant bone tumours of childhood and adolescence 1. Similar to other types of solid tumour, OS is characterized by high propensity for metastasis (specially to the lung), which is the leading cause of death 2. In spite of advancement in neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery in the treatment of OS, 5‐year survival of patients with metastatic disease has been dismal, <20% 3. Thus, it is urgent to identify new targets or factors that govern metastasis here, and to develop novel therapeutic strategies in OS management.

Cellularly, cancer has been proposed to have six fundamental hallmarks 4, which include self‐sufficiency in growth factors, insensitivity to growth‐inhibitory signals, evasion of apoptosis, limitless replicative potential, sustained angiogenesis and ability to invade and metastasize. However, the primary tumour is rarely fatal to the organism. It is the final hallmark of cancer, invasion and metastasis, that underlies its deadly nature of progression 5. Metastatic spread is responsible for more than 90% of all cancer‐related deaths, yet despite this being well‐appreciated, metastasis in and of itself remains the most poorly understood component of cancer progression.

Proteomic technologies have been used to identify proteins as cancer biomarkers and therapeutic targets that cannot be obtained by other approaches 6. Thus, two‐dimensional gel electrophoresis (2‐DE) coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) has been widely applied to analyse protein profiling of OS 7 as well as other cancers 8, 9, to develop novel diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers and to understand the biology of tumour progression. In the present study, we have identified metadherin (MTDH) as being significantly upregulated in OS tissues that had metastasized in comparison to OS without metastasis, employing 2‐DE coupled with MS. Ensuing functional analysis has shown that MTDH to be in charge of metastatic ability of OS cells, knock‐down of which can significantly suppress metastasis and proliferation of OS cells, suggesting that MTDH could be an ideal therapeutic target against metastasis of OS.

Materials and methods

OS clinical tissue specimens

Ten pairs of fresh OS tissues that had metastasized, and non metastatic, were collected from patients with OS. One hundred and two cases of OS tissue in formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded (FFPE) blocks were recruited from the Department of Orthopaedics, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People's Hospital, collected from 2006 to 2013. The present study was approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee and written informed consent was obtained from patients. None of the recruited patients had received treatment before surgery, and for all patients, full clinicopathological information was available. Representative haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)‐stained slides from each patient were retrospectively reviewed blindly and separately by two pathologists. For fresh tissue, ‘M’ samples were obtained from primary OS that metastasized to lung, and ‘N’ samples were obtained from primaries without metastasis. Both types of sample were separately excised by experienced pathologists and were frozen in liquid nitrogen within 30 min of surgery and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

OS cell lines

Human OS cell lines U2OS, SaOS‐2, SoSP‐M, OS‐9901, MG‐63 and SoSP‐9607 (Shanghai fmgbio, Shanghai, China) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37 °C, atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Protein extraction and 2‐dimensional electrophoresis (2‐DE)

Protein extraction and 2‐DE were performed as described previously 10. Briefly, total amount of 100 mg tissue samples were crushed using a metal mortar after immerging them in liquid nitrogen, and were then precipitated with 10% TCA/acetone for 2 h. The precipitate was washed in pre‐cooled acetone. After removing acetone by vacuum evaporation, the pellet was dissolved in lysis buffer and lysate was sonicated using a probe sonicator for 5 min followed by centrifugation at 40 000 × g for 30 min. Supernatant fractions were extracted from the homogenized samples and used for 2‐DE detection.

Identification of differentially expressed protein by MALDI‐TOF‐MS

For MALDI‐TOF‐MS analysis, differential protein spots were manually excised from gels and transferred to 96‐well plates. Protein‐containing gel particles were treated with 10 mm DTT, alkylated with 55 mm IAM, and subjected to in‐gel digestion with 0.01 g of trypsin (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) at 37 °C overnight (O/N). Digestion reaction was stopped using 0.1% triflouroacetic acid. Peptides generated from tryptic digestion were spotted on to Anchorchip (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) and co‐crystallized with cyano‐4‐hydroxycinnamic acid (4 mg/ml). Mass spectra of peptides were acquired by an Ultraflex MALDI‐TOF‐MS (Bruker). All PMFS were analysed using Mascot (Matrix Science, London, UK) protein search engine.

Immunohistochemistry

Haematoxylin and eosin‐stained slides and unstained slides for immunohistochemical analysis were prepared from formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded blocks of OS tissues. Immunohistochemical stains were performed using heat‐induced epitope retrieval, an avidin–biotin complex method. Rabbit anti‐MTDH antibody (ZYMED Laboratories; Invitrogen) was diluted 1:150. After incubation, sections were evaluated by light microscope examination, and cell localization of protein and immunostaining level in each section was assessed by two experienced pathologists. Staining patterns were scored as follows: negative (no staining/less than 15% of cells with positive staining, were defined as −), weak (more than 15% and less than 30% of cells with positive staining, defined as +), moderate (more than 30% and less than 60% of cells with positive staining, defined as ++) and strong positive (more than 60% of cells with positive staining, defined as +++), according to staining intensity.

Western blotting

Seventy‐two hours after transfection, U2OS and SOSP‐M cells were harvested in RIPA lysis buffer (Bioteke, Beijing, China) and 80 μg protein were subjected to 10% SDS‐PAGE separation. Proteins were transferred to PVDF microporous membrane (Millipore, Boston, MA, USA) and blots were probed with rabbit polyclonal antibody against MTDH (ZYMED Laboratories; Invitrogen); while p‐AKT (#4058S), p‐ERK1/2 (#4377S), vimentin (#3932S), E‐cadherin (#3195S), N‐cadherin (#4061S), Elf5(#2480S), PI3K(#4255S), NF‐κB (# 4764S) and GAPDH (#2118S) were all from Cell Signalling Technology (Danvers, Massachusetts, USA). β‐tubulin (sc‐9104) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). β‐tubulin and GAPDH were chosen as internal control and blots were visualized using WesternBreeze Kit (WB7105; Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) or detected using enhanced chemiluminescence plus (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) as appropriate.

Generation of stable cell lines

Stable shRNA‐mediated knockdown was achieved using the pSuper‐Retro system (OligoEngine) targeting sequences 5′‐AAGGAGCGATCTGCTAGCTAC‐3′(KD) for MTDH. Retroviral vectors were transfected into packaging cell line H29. After 48 h, viruses were collected, filtered and used to infect target cells in the presence of 5 μg/ml polybrene. Infected cells were selected with 0.8 μg/ml puromycin.

Cell proliferation assay

Methylthiazolyl blue tetrazolium (MTT; Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) spectrophotometric dye assay was used to observe and compare cell proliferation ability. U2OS and SOSP‐M cells were plated in 96‐well plates at 3 × 103 cells per well. After transfection, cell proliferation was assessed. Cells were incubated for 4 h in 20 μl MTT at 37 °C then colour was developed by incubating them in 150 μl dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO); absorbance was detected at 490 nm. Data were obtained from three independent experiments.

Cell migration and invasion assays in vitro

Cell migration propensity was calculated by the wound healing assay. U2OS and SOSP‐M cells were plated in 6‐well plates at 5 × 105 cells/well and allowed to form a confluent monolayer for 24 h. After transfection, the monolayer was scratched with a sterile pipette tip (10 μl), washed in serum‐free medium to remove floating and detached cells and photographed (time 0, 24 and 48 h) using an inversion fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Takachiho Seisakusho, Japan). Cell culture inserts (24‐well, pore size 8 μm; BD Biosciences San Diego, California, USA) were seeded with 5 × 103 cells in 100 μl medium with 0.1% FBS. Inserts pre‐coated with Matrigel (40 μl, 1 mg/ml; BD Biosciences) were used for invasion assays. Medium with 10% FBS (400 μl) was added to lower chambers and served as chemotactic agent. Non‐invasive cells were wiped from upper sides of membranes and cells on lower sides were fixed in cold methanol (−20 °C) and air dried. Cells were stained in 0.1% crystal violet (dissolved in methanol) and counted using the inverted microscope. Each individual experiment had triplicate inserts, and four microscopic fields were counted per insert.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± SEM and were analysed by two‐sided independent Student's t‐test, one‐way ANOVA and χ2 test, using spss for Windows version 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted and log‐rank testing was performed. Significance of variables for survival was analysed by Cox proportional hazards model in multivariate analysis. P < 0.05 in all cases was considered statistically significant.

Results

Protein profiling by 2‐DE with MS analysis revealed five proteins that were upregulated in OS tissues

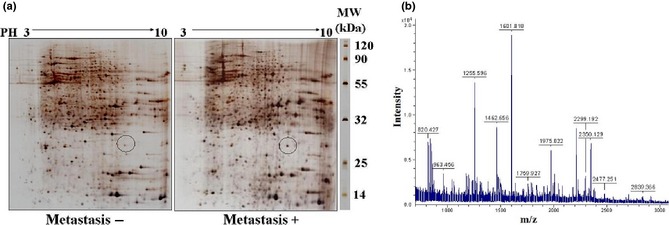

To search for and identify candidate biomarkers of metastasis of OS, we analysed 10 pairs of OS tissues that had, or had not, metastasized. Stained spots were well‐separated by 2‐DE with sharp focusing as well as wide distribution along pH 3–10 (Fig. 1a). To avoid artificial bias in differentiating protein spots, we used two criteria to judge gel quality and ensure these images were sufficient for comparative analysis: (I) overlap for all parallel gels derived from the same sample should be more than 90%, (II) correlation coefficients for all gels derived from different samples in the same tissue should be no less than 80%. Results indicated that all 2‐DE images were qualified for comparative analysis. Number of spots was automatically determined, and their normalized volume was quantified as percentage volume (%v), where %v = spot volume/spot volumes of all spots resolved in the gel. Those spots located at similar 2‐DE positions in different gels with 3‐fold difference in relative spot volumes were defined as ‘differential spots’ in these 2‐DE gels. Eventually, we identified MTDH (Fig. 1b) as a differential spot that was extremely significantly upregulated in OS tissues that had metastasized (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Differential upregulation of proteins in osteosarcoma ( OS ) tissues between metastasis and non‐metastasis using the proteomics approach. (a) Representative images of 2‐D gel for OS with metastasis to lung (M+) and non‐metastasis (M−). Isoelectric focusing at pH 3–10 was carried out at first dimension electrophoresis using 18 cm immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips with higher loading of proteins. Differential spots between M+ and M− labelled with a circle. (b) Mass spectrum of metadherin (MTDH) generated from digested peptides of 2‐DE spot no. 1, identified by mass spectrometry and peptide mass fingerprinting.

Table 1.

Upregulated proteins in OS tissues with metastasis identified by 2‐DE and mass spectrometry

| Spot no. | Accession no. | Protein name | Theoretical molecular mass | Theoretical PI | Coverage (%) | Peptides identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AAH14977 | MTDH | 64.4 | 9.33 | 45 | RHDGKEVDEGAWETKISHREKR |

| 2 | O95433 | AHSA1 | 38.6 | 5.41 | 50 | LKETFLTSPE ELYRVFTTQELVQ |

| 3 | Q9UJZ1 | STOML2 | 37.6 | 6.88 | 35 | QTTMRSELGK LSLDKVFRER |

| 4 | P14618 | PKM2 | 59.4 | 5.35 | 17 | KITLDNAYME KCDENILW |

| 5 | P61978 | HNPRK | 66.1 | 5.39 | 18 | RVVLIGGKPD RVVECIKIIL |

OS, osteosarcoma; PI, isoelectric point.

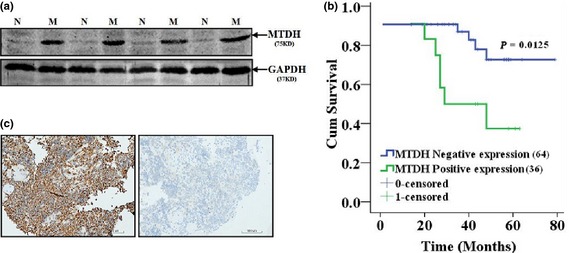

MTDH was highly expressed in OS tissues with metastasis

To confirm results provided by 2‐DE and MS, we analysed MTDH expression trend using Western blotting, with rather limited fresh OS clinical tissues with or without metastasis. It was verified that MTDH was significantly higher in OS with metastasis than in non‐metastasis tissues (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, we proceeded to validate MTDH expression using an extended larger panel of PPFE blocks of OS with IHE methods. It can be seen that MTDH was homogeneously expressed in OS tissue, and that through IHC analysis, that MTDH mainly located in cytoplasm (Fig. 2b). Statistical analysis of MTDH expression in combination with clinicopathological information determined that MTDH was significantly associated with metastasis (Table 2) and poorer prognosis (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Confirmation of expression of metadherin ( MTDH ) in osteosarcoma ( OS ) tissues with metastasis ( M ) and non‐metastasis ( N ). (a) Confirmation of MTDH in fresh OS tissues with metastasis and without metastasis using immunoblotting method. (b) Confirmation of MTDH using immunohistochemistry method. (c) Survival analysis using Kaplan–Meier curve in 102 cases of OS.

Table 2.

Clinicopathological significance of metadherin (MTDH) expression in osteosarcoma

| MTDH | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Low expression (−/+) | High expression (++/+++) | χ2 | P value | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 62 | 43 | 19 | 0.381 | 0.654 |

| Female | 40 | 30 | 10 | ||

| Age | 18.4 ± 8.7 | 18.3 ± 11.7 | 0.482 | ||

| Survival year | |||||

| <5 | 52 | 21 | 31 | 7.449 | 0.008 |

| >5 | 50 | 42 | 8 | ||

| Metastasis | |||||

| Yes | 28 | 12 | 16 | 15.636 | 0.000 |

| No | 74 | 61 | 13 | ||

| Tumour size (diameter) | |||||

| ≤8 cm | 40 | 27 | 13 | 0.535 | 0.505 |

| >8 cm | 62 | 46 | 16 | ||

| Histological stage | |||||

| G1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.952 | 0.576 |

| G2 | 98 | 71 | 27 | ||

| Histological type | |||||

| Osteoblastic | 54 | 38 | 16 | 0.302 | 0.959 |

| Fibroblastic | 20 | 15 | 5 | ||

| Chondroblastoma | 9 | 6 | 3 | ||

| Others | 19 | 14 | 5 | ||

| Primary site | |||||

| Femur, tibia | 79 | 59 | 20 | 1.671 | 0.293 |

| Others | 23 | 14 | 9 | ||

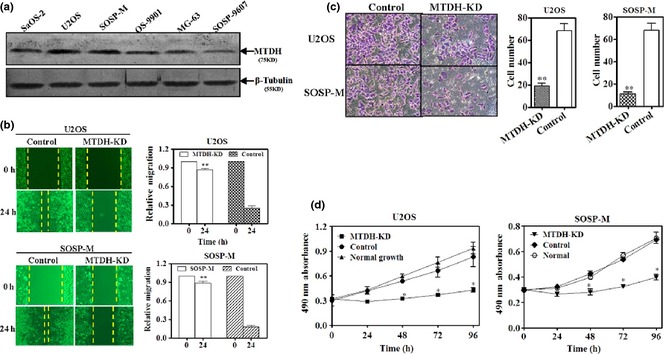

MTDH promoted OS cell metastasis

To determine the role of MTDH in OS cells, first, we detected basal expression of MTDH in a panel of OS cell lines. It was found that its basal expression was higher in U2OS and SoSP‐M cell lines. Thus, these two OS cell lines were chosen for the following experiment in vitro. Secondly, MTDH was knocked‐down in both U2OS and SoSP‐M cell lines using retroviral shRNA vector. It was found that reducing MTDH protein significantly suppressed both migratory (Fig. 3a) and invasive (Fig. 3b) propensities of U2OS and SoSP‐M cell lines; also inhibited their proliferation (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Metadherin ( MTDH ) promoted migration, invasion and proliferation of osteosarcoma ( OS ) cell lines. (a) Endogenous expression of MTDH in a panel of OS cell lines was detected using immunoblotting. β‐tubulin, loading control. Total protein of 80 μg was loaded per lane, separated by 10% SDS‐PAGE, followed by visualization with WesternBreeze kit (Invitrogen, USA). (b) Wound‐healing assay for U2OS and SOSP‐M after knock‐down of MTDH using retroviral shRNA vector transfection for 24 h. Left – qualification assay, right – quantification assay of wound‐healing. (c) Transwell assays for U2OS and SOSP‐M after knock‐down of MTDH using retroviral shRNA vector transfection for 48 h. Left – qualification assay, right – quantification assay of transwell. (d) MTT assay for U2OS and SOSP‐M after knock‐down of MTDH using retroviral shRNA vector transfection for 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, independent Student's t‐test or one‐way ANOVA analysis).

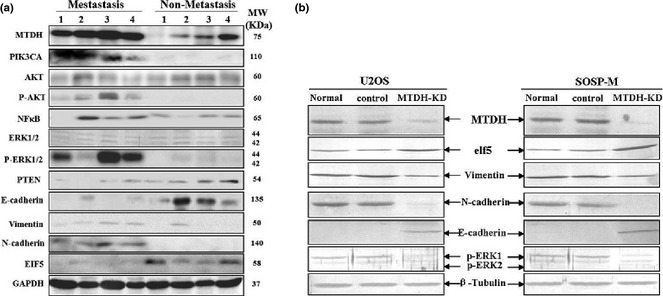

MTDH promoted metastasis via epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)

To understand MTDH worked in metastasis‐associated OS, we examined key markers involved in EMT and in the ERK1/2 signalling pathway, based on literature available 11, 12 for both cell lines and clinical tissues. In clinical OS tissues with or without metastasis, it was found that those cases with metastasis whose MTDH expression was remarkably higher, specific mesenchymal markers, such as vimentin and N‐cadherin were correspondingly higher, whereas E‐cadherin, a classical epithelial marker was lower compared to those OS cases without metastasis. Elf5, reported to be an inhibitor of EMT 13, was also consistently and expectedly lower. Meanwhile, we could also see that p‐ERK1/2, p‐AKT and NF‐κB signalling pathways could be activated by overexpression of MTDH. While, those OS cases without metastasis whose MTDH expressions were lower, expression of vimentin, N‐cadherin and E‐cadherin, were in contrast to those in OS with metastasis. P‐ERK1/2, p‐AKT and NF‐κB signalling pathways were close to inactivated in non‐metastasis OS tissues (Fig. 4a). To further validate whether MTDH promoted metastasis via EMT, we repeated the whole experiment on OS cell lines in vitro after knock‐down of MTDH (Fig. 4b). The result was highly consistent and in agreement with that of the clinical tissues.

Figure 4.

Metadherin ( MTDH ) promoted metastasis via epithelial–mesenchymal transition ( EMT ). (a) Canonical markers of EMT as well as ERK signalling pathway were assayed using immuoblotting in four cases of metastasis and non‐metastasis osteosarcoma (OS) tissues. (b) In parallel, markers of EMT as well as ERK signalling pathway were assayed using immuoblotting in U2OS and SOSP‐M cells after knock‐down of MTDH by retroviral shRNA vector transfection for 72 h. GAPDH and β‐tubulin – loading control. Total protein of 80 μg was loaded per lane, separated by 10% SDS‐PAGE, followed by visualization with WesternBreeze kit (Invitrogen, USA) and with enhanced chemiluminescence plus (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Discussion

In our study, we found that MTDH was significantly overexpressed in OS tissues with metastasis compared to non‐metastatic OS tissues, and that MTDH promoted metastasis by regulating EMT. Knock‐down of MTDH also inhibited proliferation of the OS cell lines. Our results demonstrate that MTDH could, thus, be used as an ideal therapeutic target in the management of OS metastasis.

Metadherin has been extensively reported to be as an important molecule involved in metastasis of breast carcinoma 14, 15, 16 and hepatocellular carcinoma 17. However, few reports are available regarding MTDH in investigation of OS. Of three earlier studies, one reported that MTDH played a crucial role in OS progression through MMP‐2, and MTDH could be a useful biomarker for prediction of OS progression and prognosis; this is totally in line with our clinical–pathological observations 18. The second found that MTDH regulated OS cell invasion and chemoresistance via endothelin‐1/endothelin‐A receptor signalling 19 and the third, concerned MTDH being identified as a new cell surface target shared with several paediatric solid tumours including OS, using gene expression profiles coupled with annotation databases 20. However, in this last study, MTDH was only identified at the mRNA level and is yet to be validated at protein level. Consistent and complementary between these pieces of work and ours is that MTDH has been identified as novel, and is highly associated with metastasis of OS, using a proteomics approach at the protein level.

The majority of previous reports on MTDH have focused on its role in oncogenic 18, 21 and metastatic ability 15, 16. In these earlier findings MTDH was shown, using either overexpression or knock‐down or both techniques, to promote anchorage‐independent growth in soft agar 20, invasion 22, metastasis 17, apoptosis resistance 23, chemoresistance 24 of different types of cell lines in vitro and primary tumour growth in vivo 25. In our study, our discoveries in OS cell lines were in agreement with above previously reported work.

A striking feature of MTDH was the remarkable correlation of its expression with either tumour formation, metastasis, prognosis or chemoresistance, in almost every tumour type where clinical data have been investigated. For example, in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma 26, non‐small cell lung cancer 27 and oligodendroglioma 28, MTDH was shown (using IHC) to be markedly upregulated in tumours, compared to corresponding normal tissues. In the earlier reports, MTDH expression was shown to be strongly correlated with increased patient stage and reduced overall survival in multiple patient cohorts – wholly consistent with our findings in OS, despite different cancer types.

Growing reports suggest and even demonstrate that MTDH highly consistently involves and leads to metastasis in a wide variety of different cancer cell lines 15. However, the underlying mechanism by which MTDH promotes metastasis remains largely unknown. There have been reports that found that MTDH can modulate many pathways, such as activation of NF‐κB and AKT 12, 29, and activation of MEK/ERK branch of the Ras downstream pathway 12. In our study, not only have we replicated that overexpression of MTDH can activate the AKT, ERK and NF‐κB signalling pathway, but also we found that MTDH can regulate epithelial–mesenchymal transition of OS cells, with supporting evidence from both OS tissues and cell lines. Specifically, knock‐down MTDH suppressed EMT by upregulating Elf‐5 in one way or another, that has been reported to be an inhibitor of EMT 13. With regard to the proposal that MTDH mediates metastasis via regulating EMT, this has been experimentally supported by different studies but with similar conclusions in breast cancer 11, hepatocellular carcinoma 17 and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck 30 respectively. Although clinical samples and OS cell lines we employed are limited, we have demonstrated with biochemical evidence that MTDH mediates metastasis through regulating EMT both in OS tissues and cell lines; detailed mechanisms of this will be extended in the future.

In all, MTDH was significantly expressed in OS tissues with metastasis. Knock‐down of MTDH suppressed proliferation, migration and invasion of OS cells in vitro, which may be via regulating EMT. Our results demonstrate that MTDH could be used as an ideal therapeutic target in the management of OS with metastasis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Jiayi Liu PhD for her careful examination of our manuscript.

References

- 1. Long XH, Mao JH, Peng AF, Zhou Y, Huang SH, Liu ZL (2013) Tumor suppressive microRNA‐424 inhibits osteosarcoma cell migration and invasion via targeting fatty acid synthase. Exp. Ther. Med. 5, 1048–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mao J, Niu M, Yang M, Zhang L, Xi Y (2013) Role of relaxin‐2 in human primary osteosarcoma. Cancer Cell Int. 13, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hegyi M, Semsei AF, Jakab Z, Antal I, Kiss J et al (2011) Good prognosis of localized osteosarcoma in young patients treated with limb‐salvage surgery and chemotherapy. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 57, 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lu X, Kang Y (2007) Organotropism of breast cancer metastasis. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 12, 153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kawai A, Kondo T, Suehara Y, Kikuta K, Hrohashi S (2008) Global protein‐expression analysis of bone and soft tissue sarcomas. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 466, 2099–2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suehara Y, Kubota D, Kikuta K, Kaneko K, Kawai A et al (2012) Discovery of biomarkers for osteosarcoma by proteomics approaches. Sarcoma 2012, 425636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Qi YJ, Chao WX, Chiu JF (2012) An overview of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma proteomics. J. Proteomics 75, 3129–3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mustafa MG, Petersen JR, Ju H, Cicalese L, Snyder N et al (2013) Biomarker discovery for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C‐infected patients. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 3640–3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grunewald TG, Kammerer U, Winkler C, Schindler D, Sickmann A et al (2007) Overexpression of LASP‐1 mediates migration and proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells and influences zyxin localisation. Br. J. Cancer 96, 296–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li X, Kong X, Huo Q, Guo H, Yan S et al (2011) Metadherin enhances the invasiveness of breast cancer cells by inducing epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cancer Sci. 102, 1151–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang J, Zhang Y, Liu S, Zhang Q, Wang Y et al (2013) Metadherin confers chemoresistance of cervical cancer cells by inducing autophagy and activating ERK/NF‐κB pathway. Tumour Biol. 34, 2433–2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chakrabarti R, Hwang J, Andres Blanco M, Wei Y, Lukačišin M et al (2012) Elf5 inhibits the epithelial‐mesenchymal transition in mammary gland development and breast cancer metastasis by transcriptionally repressing Snail2. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 1212–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Qian BJ, Yan F, Li N, Liu QL, Lin YH et al (2011) MTDH/AEG‐1‐based DNA vaccine suppresses lung metastasis and enhances chemosensitivity to doxorubicin in breast cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 60, 883–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wei Y, Hu G, Kang Y (2009) Metadherin as a link between metastasis and chemoresistance. Cell Cycle 8, 2132–2133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hu G, Chong RA, Yang Q, Wei Y, Blanco MA et al (2009) MTDH activation by 8q22 genomic gain promotes chemoresistance and metastasis of poor‐prognosis breast cancer. Cancer Cell 15, 9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhu K, Dai Z, Pan Q, Wang Z, Yang GH et al (2011) Metadherin promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through induction of epithelial‐mesenchymal transition. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 7294–7302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang F, Ke ZF, Sun SJ, Chen WF, Yang SC et al (2011) Oncogenic roles of astrocyte elevated gene‐1 (AEG‐1) in osteosarcoma progression and prognosis. Cancer Biol. Ther. 12, 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu B, Wu Y, Peng D (2013) Astrocyte elevated gene‐1 regulates osteosarcoma cell invasion and chemoresistance via endothelin‐1/endothelin A receptor signaling. Oncol. Lett. 5, 505–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Orentas RJ, Yang JJ, Wen X, Wei JS, Mackall CL et al (2012) Identification of cell surface proteins as potential immunotherapy targets in 12 pediatric cancers. Front. Oncol. 2, 194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Emdad L, Lee SG, Su ZZ, Jeon HY, Boukerche H et al (2009) Astrocyte elevated gene‐1 (AEG‐1) functions as an oncogene and regulates angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21300–21305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhao Y, Kong X, Li X, Yan S, Yuan C et al (2011) Metadherin mediates lipopolysaccharide‐induced migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. PLoS One 6, e29363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meng X, Brachova P, Yang S, Xiong Z, Zhang Y et al (2011) Knockdown of MTDH sensitizes endometrial cancer cells to cell death induction by death receptor ligand TRAIL and HDAC inhibitor LBH589 co‐treatment. PLoS One 6, e20920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yoo BK, Chen D, Su ZZ, Gredler R, Yoo J et al (2010) Molecular mechanism of chemoresistance by astrocyte elevated gene‐1. Cancer Res. 70, 3249–3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Emdad L, Sarkar D, Lee SG, Su ZZ, Yoo BK et al (2010) Astrocyte elevated gene‐1: a novel target for human glioma therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 9, 79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu C, Chen K, Zheng H, Guo X, Jia W et al (2009) Overexpression of astrocyte elevated gene‐1 (AEG‐1) is associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) progression and pathogenesis. Carcinogenesis 30, 894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song L, Li W, Zhang H, Liao W, Dai T et al (2009) Over‐expression of AEG‐1 significantly associates with tumour aggressiveness and poor prognosis in human non‐small cell lung cancer. J. Pathol. 219, 317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xia Z, Zhang N, Jin H, Yu Z, Xu G et al (2010) Clinical significance of astrocyte elevated gene‐1 expression in human oligodendrogliomas. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 112, 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Long M, Hao M, Dong K, Shen J, Wang X et al (2013) AEG‐1 overexpression is essential for maintenance of malignant state in human AML cells via up‐regulation of Akt1 mediated by AURKA activation. Cell. Signal. 25, 1438–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yu C, Liu Y, Tan H, Li G, Su Z et al (2013) Metadherin regulates metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck via AKT signalling pathway‐mediated epithelial‐mesenchymal transition. Cancer Lett. 343, 258–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]