Abstract

IscR (iron-sulfur cluster regulator) is encoded by an ORF located immediately upstream of genes coding for the Escherichia coli Fe-S cluster assembly proteins, IscS, IscU, and IscA. IscR shares amino acid similarity with MarA, a member of the MarA/SoxS/Rob family of transcription factors. In this study, we found that IscR functions as a repressor of the iscRSUA operon, because strains deleted for iscR have increased expression of this operon. In addition, in vitro transcription reactions established a direct role for IscR in repression of the iscR promoter. Analysis of IscR by electron paramagnetic resonance showed that the anaerobically isolated protein contains a [2Fe-2S]1+ cluster. The Fe-S cluster appears to be important for IscR function, because repression of iscR expression is significantly reduced in strains containing null mutations of the Fe-S cluster assembly genes iscS or hscA. The finding that IscR activity is decreased in strain backgrounds in which Fe-S cluster assembly is impaired suggests that this protein may be part of a novel autoregulatory mechanism that senses the Fe-S cluster assembly status of cells.

Keywords: cofactor synthesis|metalloproteins|MarA|transcriptional regulator|EPR

Fe-S proteins are nearly ubiquitous in nature and are required for many cellular processes. Although Fe-S clusters can be assembled into proteins in vitro from Fe2+ and S2−, it is clear that in vivo, this process must be facilitated by protein factors to avoid accumulation of Fe2+ and S2− to toxic levels. An important finding in recent years is the discovery of a conserved set of proteins in organisms from bacteria to humans that facilitate assembly of Fe-S clusters into Fe-S proteins (1, 2). In several bacteria, the genes encoding these Fe-S assembly proteins (IscS, IscU, IscA, Hsc66, Hsc20, and ferredoxin) are organized in a cluster, iscSUAhscBAfdx. In this study, we have focused on the regulation of the expression of the genes that encode the Fe-S cluster assembly factors from Escherichia coli.

Genetic experiments support the key role of the proteins encoded by iscSUAhscBAfdx in Fe-S cluster assembly, because mutations in the E. coli genes decrease the activity of many Fe-S proteins (3–5). Furthermore, biochemical studies have begun to provide some insight into the process of Fe-S cluster assembly (1, 6–10). IscS is a cysteine desulfurase that procures the sulfur from cysteine for Fe-S cluster assembly (1, 7). IscU can form a complex with IscS and acquire an unstable [2Fe-2S] cluster that has been proposed to be a source of Fe and sulfur for Fe-S protein assembly (6, 8, 11). IscA can also acquire a Fe-S cluster in vitro (9). Hsc66 and Hsc20, homologs to molecular chaperones, form a complex in vitro with IscU, but the exact physiological function of this interaction has yet to be determined (10).

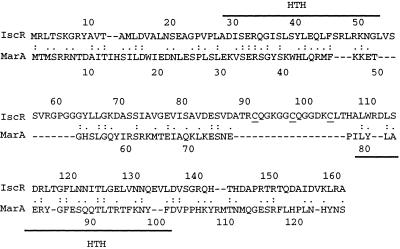

It is also of interest to understand how expression of the Fe-S cluster assembly proteins is controlled. In bacteria, the cellular requirements for Fe-S cluster assembly must vary, because the synthesis of many Fe-S proteins is regulated (12) and environmental conditions arise that lead to the destruction of these metal centers (13). Thus, it would not be surprising to find that expression of the assembly proteins is regulated to accommodate such changes in Fe-S cluster assembly requirements. A clue that the genes encoding Fe-S cluster assembly proteins might be regulated came from the observation that immediately upstream of iscSUA in E. coli and several other bacteria, there is a gene (here called iscR) whose protein product is similar to the well characterized transcriptional regulator MarA (multiple antibiotic resistance) from E. coli (Fig. 1). MarA is a global regulator of genes induced by antibiotics and is a member of a subfamily of AraC-like transcriptional regulators called the Mar/Sox/Rob family (14). Interestingly, IscR contains a stretch of amino acids not found in MarA, which includes cysteine residues that may coordinate a Fe-S cluster (Fig. 1). Given the proximity of iscR to the Fe-S cluster assembly genes iscSUA, the similarity of IscR to MarA, and the possibility that IscR contains a Fe-S cluster, we characterized the properties of IscR and investigated whether this protein regulates the transcription of the isc gene cluster. Our results indicate that IscR contains a [2Fe-2S] cluster and acts as a direct negative regulator of the iscRSUA operon.

Figure 1.

Similarity of IscR to MarA. Amino acid sequence alignment of IscR and MarA generated with align showed 20% identical residues (:) and 47% similar residues (.). Solid lines denote the two helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domains of MarA; the three cysteine residues (C92, C98, C104) of IscR that may coordinate the [2Fe-2S] cluster are underlined.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Construction.

iscR is annotated as yfhP or b2531 in the E. coli genome sequence. Plasmid pPK5960 was created by ligating the 985-bp StuI-EcoRV fragment containing iscR from pPK4071 (5) into the EcoRV site of pACYC184 (15). pPK6161 was created by PCR amplification of the iscR ORF (+1 to +489 nucleotides) by using primers that contained NdeI and BamHI restriction enzyme sites for subsequent directional cloning into the expression vector pET-11a (16).

Strain Construction.

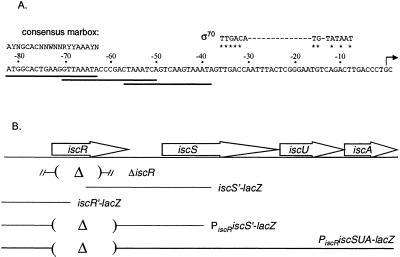

Chromosomal lacZ fusions to the isc operon were constructed by using the two-step method of Simons et al. (17). DNA fragments to be analyzed for promoter activity were obtained by PCR amplification of chromosomal DNA with Pfu DNA Polymerase (Stratagene) following the manufacturer's recommended conditions. PCR fragments (Fig. 2) containing 476 to +74 nucleotides relative to the iscR start codon; −396 to +419 nucleotides relative to the iscS start codon; −476 to +9 nucleotides relative to the iscR start codon, and −226 to +419 nucleotides relative to the iscS start codon; and −476 to +9 nucleotides relative to the iscR start codon and −226 relative to the iscS start codon to the end of the iscA ORF were phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega) and ligated into SmaI-digested pRS1553 to generate gene fusions to lacZ (17). These lacZ fusions will be referred to as iscR′-lacZ, iscS′-lacZ, PiscRiscS′-lacZ, and PiscRiscSUA-lacZ, respectively. PiscRiscS′-lacZ and PiscRiscSUA-lacZ have the same promoter region as iscR′-lacZ but contain an in-frame deletion of iscR (from codons 3 to 127) and have a BamHI restriction site in place of codons 3 and 127. The various isc-lacZ fusions were then recombined onto λRS468, and the resulting recombinant λ phages were inserted in single copy at the chromosomal λ attachment site of RZ4500 (18), which was verified by the ter excision test (17, 19).

Figure 2.

The iscR promoter region. (A) The DNA sequence of the iscR promoter region. The transcription start site identified by 5′ mapping is indicated by an arrow. Matches to an extended −10 element and a consensus −35 hexamer of the Eσ70-binding site with a 17-bp spacer region are marked by asterisks. The position of three overlapping marbox-like sequences (sequences that bind MarA) are denoted by the solid lines; −63 to −82 nucleotides contain an exact match to the marbox consensus sequence, whereas the sequences from −38 to −57 nucleotides and −51 to −70 nucleotides match only 9 nucleotides of the 14 conserved marbox nucleotides. (B) The location of the DNA segments used to generate lacZ fusions in this study are shown and consist of the following regions: iscR′ (−476 to +74 nucleotides relative to the iscR start codon), PiscRiscS′ (−476 to +9 nucleotides relative to the iscR start codon and −226 to +419 nucleotides relative to the iscS start codon), PiscRiscSUA (−476 +9 nucleotides relative to the iscR start codon and −226 nucleotides relative to the iscS start codon to the end of the iscA ORF). The iscR sequences that were removed to generate the in-frame iscR deletions in the lacZ fusions or in the chromosome (the line flanked by the hash marks) are indicated by parentheses.

An iscR deletion strain, PK5956, was constructed by replacing codons 2–120 of iscR with a KnR cassette flanked by FRT (FLP recognition target) sites from plasmid pKD13 in strain BW25113/pKD46, as previously described (20). This ΔiscR∷KnR allele was introduced into strains MG1655, PK6361, PK6259, and PK6364 by P1 transduction, creating strains PK4855, PK6367, PK6271, and PK6390, respectively. The KnR cassette was subsequently deleted from PK4855 by transforming with pCP20 encoding FLP recombinase (20). The resulting KnS strain (PK4854) contained the iscR start codon, 84 nucleotides of FRT sequence, and the nine terminal codons of iscR, leaving an in-frame iscR deletion.

To analyze the effect of the loss of IscR, IscS, and HscA on isc gene expression, null mutations of the genes encoding these proteins (Table 1) were introduced into the appropriate strains by P1 transduction. To facilitate construction of the ΔiscS∷KnR derivative, a closely linked (90%) TetR marker [zff-208∷Tn10 from CAG 18481 (21)] was first introduced into PK4331 (5) to obtain PK6311 containing both the TetR and KnR markers. Because strains containing ΔiscS∷KnR have a slow growth phenotype and take 2 days to form colonies on plates, selection for the TetR marker eliminated obtaining spontaneous KnR strains that would also appear in that time period.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Genotype | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| Strain | ||

| RZ4500 | MG1655 lacZΔ145 | Ref. 18 |

| W3110hscA2-cat | L. E. Vickery, personal communication | |

| PK6307 | RZ4500 λiscS′-lacZ | Transduction of RZ4500 with λiscS′-lacZ |

| PK6311 | RZ4500 ΔiscS∷KnR, zff-208∷Tn10 | P1 transduction of Tn10 from CAG18481 (21) into PK4331 (5) |

| PK6361 | RZ4500 λPiscRiscS′-lacZ | Transduction of RZ4500 with λPiscRiscS′-lacZ |

| PK5956 | BW25113/pKD46 ΔiscR∷KnR | Transformation of BW25113/pKD46 (20) |

| PK6367 | PK6361 ΔiscR∷KnR | P1 transduction from PK5956 |

| PK6259 | RZ4500 λPiscRiscSUA-lacZ | Transduction of RZ4500 with λPiscRiscSUA-lacZ |

| PK6271 | PK6259 ΔiscR∷KnR | P1 transduction from PK5956 |

| PK6364 | RZ4500 λiscR′-lacZ | Transduction of RZ4500 with λiscR′-lacZ |

| PK6390 | PK6364 ΔiscR∷KnR | P1 transduction from PK5956 |

| PK6391 | PK6364 ΔiscS∷KnR, zff-208∷Tn10 | P1 transduction from PK6311 |

| PK6389 | PK6364 hscA2-cat | P1 transduction from W3110hscA2-cat |

| PK4855 | MG1655 ΔiscR∷KnR | P1 transduction from PK5956 |

| PK4854 | MG1655 ΔiscR | Resolution of Kn cartridge with pCP20 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pPK5960 | StuI-EcoRV 985-bp iscR fragment cloned into pACYC184, CmR | This study |

| pPK6161 | +1 to +489 iscR fragment cloned into pET-11a, ApR | This study |

| pPK6511 | −161 to +38 iscR promoter fragment cloned into pUC19-spf′, ApR | This study |

β-Galactosidase Assays.

To assay promoter activity from the lacZ fusion constructs, cells were grown overnight in LB media and subcultured into fresh growth medium at 1:800 dilution. Cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.4–0.8, placed on ice, the appropriate antibiotic was added to inhibit further cell growth, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as previously described (22).

Mapping the 5′ End of isc mRNA.

Total cellular RNA (2–5 μg) was prepared (method from C. Gross, personal communication) from cultures grown in LB media to an OD600 of 0.3–0.8 and then hybridized at 65°C to 32P-labeled primers complementary to +53 to +71 nucleotides of the iscR mRNA. Primer extension with Thermoscript Reverse Transcriptase (GIBCO/BRL) was carried out according to the manufacturer's recommendations; the products were separated on a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel, and the gel was exposed to either film or a PhosphorImager screen (Molecular Dynamics). To identify the transcription start site, sequencing reactions of pPK4071 (5) by using the same primer were run in parallel.

In Vitro Transcription Reactions.

A plasmid template (pPK6511) for in vitro transcription reactions was created by ligating the SmaI-StuI fragment from pPK4071, containing sequences −161 to +38 relative to the in vivo mapped transcription start site of iscR, into pUC19-spf′ (23). This plasmid was purified by using the Maxiprep kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), and in vitro transcription reactions containing pPK6511 template DNA (2 nM), IscR (656 nM protein, 200 nM Fe-S cluster), and RNAP Eσ70 holoenzyme (50 nM) (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, WI) were performed as previously described (24) in a Coy chamber.

IscR Purification.

IscR was purified from E. coli B strain PK22 (BL21Δcrp-bs990Δfnr) harboring iscR under the control of the inducible T7 RNA polymerase promoter on plasmid pPK6161. Cell growth, protein overproduction, harvesting of cells, and preparation of anaerobic cell extracts were carried out as described previously (25). In an anaerobic chamber (Coy) containing 5% CO2, 5% H2, and 90% N2, the supernatant was loaded at a flow rate of 1 ml/min onto a 5-ml HiTrap Heparin column (Amersham Pharmacia) by using an Amersham Pharmacia LCC-501 Plus-based FPLC system. The column was washed with 10 ml of anaerobic buffer A (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4/10% glycerol/0.1 M KCl) containing 1 mM DTT, 1.7 mM dithionite, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. IscR was eluted from the column in a linear gradient of 0.1–1.0 M KCl in anaerobic buffer A at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Fractions containing IscR were pooled and loaded at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min onto a 5-ml BioRex70 (Bio-Rad) column on the same FPLC system. IscR was eluted from the column in a linear gradient of 0.1–1.0 M KCl in anaerobic buffer A at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min and concentrated by passing the eluent over a 1-ml BioRex70 column and eluting with 0.8 M KCl-containing buffer A.

Iron, Sulfide, and Protein Determinations.

The iron (26) and sulfide (27) content of IscR were analyzed in duplicate. Protein concentrations (reported here as monomers) were determined by a biuret procedure as described previously (28) and standardized against the FNR protein (28).

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy.

After recording the spectrum of the protein as obtained on anaerobic purification, [2Fe-2S] IscR was oxidized by exposing the purified protein to air for 10 min and then frozen. For reduction of the air-oxidized sample, the sample (200 μl) was thawed and transferred to a 5-ml vessel with two sidearms, suitable for gassing and evacuation (29). The sample was degassed, and 5 μl of a dithionite solution (containing a 5-fold molar excess of dithionite) was added through a sidearm during argon flow. The vessel was closed and placed in an anaerobic chamber, where the sample was transferred to an EPR tube and frozen.

Results

IscR Negatively Regulates iscR Expression in Vivo.

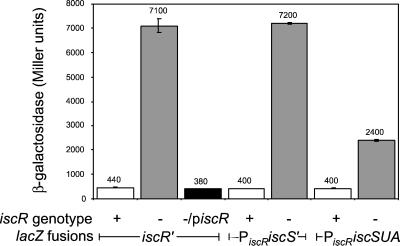

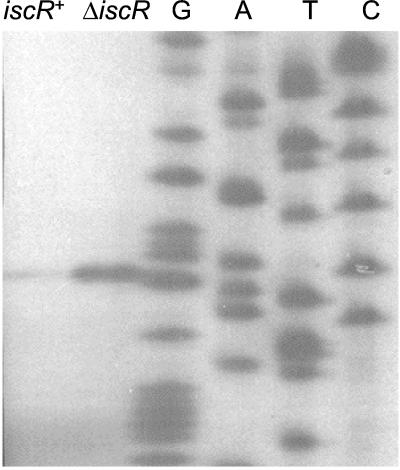

Inspection of the DNA sequence upstream of iscR revealed the presence of DNA sequences similar to those that MarA binds −151 to −106 nucleotides upstream of the iscR initiation codon (Fig. 2). We considered it a reasonable possibility that IscR might bind these sequences, because IscR contains regions similar to the helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domains of MarA (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the location of the putative binding sites upstream of iscR led us to hypothesize that IscR might regulate its own synthesis. Two lines of evidence suggest that in vivo IscR is indeed a regulator of iscR transcription. First, we compared β-galactosidase levels of both iscR+ and ΔiscR∷KnR strains containing the iscR upstream region fused to the reporter gene, lacZ (iscR′-lacZ), on a λ phage integrated at the λ attachment site (Fig. 2). These results showed that expression of the iscR′-lacZ fusion increased 17-fold in the absence of IscR (Fig. 3). When iscR was provided in trans on plasmid pPK5960, β-galactosidase activity returned to wild-type levels, demonstrating that the effect is attributable to iscR (Fig. 3; piscR). Second, mapping of the 5′ end of the iscR mRNA by primer extension assays showed that one major 5′ end was identified 67 nucleotides upstream of the iscR start codon in both an iscR+ strain (MG1655) and a strain containing an in-frame deletion of iscR (PK4854) (Fig. 4). In addition, this appears to be an IscR-responsive transcript, because levels were increased in a strain lacking IscR (Fig. 4). Taken together, these data indicate that IscR negatively regulates transcription from a promoter located upstream of iscR.

Figure 3.

IscR negatively regulates expression of iscRSUA. β-Galactosidase activity was measured from strains containing lacZ fusions to the DNA regions shown in Fig. 2. IscR+ strains (open bars) contain wild-type iscR, and IscR− strains (filled bars) contain the ΔiscR∷ KnR allele; piscR is plasmid pPK5960. The data represent the average activity of three independently isolated strains.

Figure 4.

Primer extension assays of iscR mRNA. An autoradiograph of primer-extended RNA products from either MG1655 (iscR+) or PK4854 (ΔiscR), by using an iscR-specific primer. Sequencing ladders carried out with the same primer are included as a reference.

IscR Contains a [2Fe-2S] Cluster.

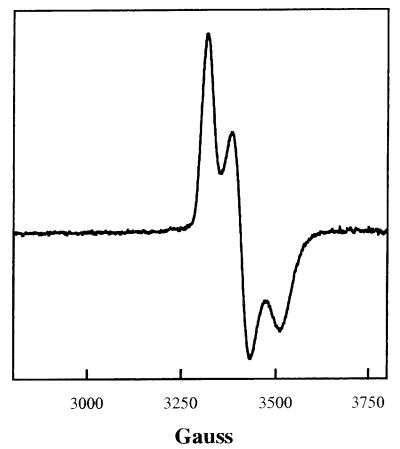

To further characterize IscR and determine whether it directly represses iscR transcription, we purified the protein from cells that overexpress IscR. Because IscR contained a series of Cys residues, we reasoned that it might contain a Fe-S cluster; therefore, the protein was purified under anaerobic conditions by using the overexpression scheme previously shown to allow isolation of the FNR protein, which contains an oxygen-sensitive Fe-S cluster (25). By SDS/PAGE, the protein as obtained on purification had a molecular weight of approximately that of the predicted size of 17,336 (data not shown). In addition, IscR had a reddish color, and the broad absorption features between 500 and 600 nm in the absorption spectrum were typical of a protein containing a [2Fe-2S] cluster (data not shown) (30). Anaerobically purified IscR showed an EPR signal with g values at 1.99, 1.94, and 1.88, typical for the reduced (1+) state (Fig. 5), which accounted for one spin per 2 S2−. The behavior of the signal toward changes of temperature and microwave power indicated that the Fe-S cluster in IscR has a particularly low spin relaxation rate. These features together, the optical spectra, the spin vs. sulfide stoichiometry, and the low spin relaxation rate, leave no doubt that IscR contains a [2Fe-2S] cluster. When the sample was thawed, oxidized by shaking in air for 10 min, and refrozen, the only signal observed was at g = 4.3, typical for a high-spin ferric iron accounting for only 4% of the iron in the sample, and the color of the protein changed from red to brown, indicative of [2Fe-2S]1+ cluster conversion to the 2+ oxidation state. After reduction (see Materials and Methods) the signal at g = 1.99, 1.94, 1.88 was again observed with no significant loss in intensity, demonstrating that the cluster undergoes reversible oxidation reduction. Sulfide and iron analysis of four IscR preparations showed that the stoichiometry of S2− per mol of IscR ranged from 0.36 to 0.63 with an average Fe to S2− ratio of 1.2. In summary, these results demonstrate that IscR contains a [2Fe-2S] cluster, but that these preparations are not completely occupied with Fe-S clusters, a finding not unusual for overexpressed Fe-S proteins (25).

Figure 5.

EPR spectrum of IscR. EPR spectrum (first derivative) of IscR as obtained on purification under anaerobic conditions. The protein concentration was 1.75 mM, S2−1.11 mM and Fe 1.16 mM. The spectra were collected at a frequency of 9.2254 GHz, microwave power of 10 μW, modulation amplitude of 0.4 mT (4 G), modulation frequency of 100 kHz, scan time of 4 min, and temperature of 20 K. The g values are 1.99, 1.93, and 1.88.

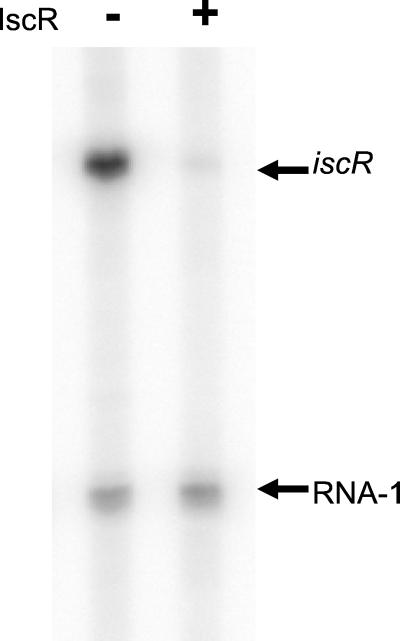

IscR Acts as a Repressor in Vitro.

To establish that IscR was directly affecting transcription from its own promoter, we carried out in vitro transcription reactions by using an iscR promoter template. In the presence of only Eσ70 RNAP and supercoiled template DNA, a transcript of 155 nucleotides was observed in addition to the control RNA-1 transcript (Fig. 6). The 155-nt transcript corresponds to the iscR transcript, because its production depended on the iscR insert, and this product is of the size expected according to the in vivo 5′end-mapping data in Fig. 4. Addition of IscR protein to the transcription reactions reduced the abundance of the iscR transcript 38-fold (±2), whereas no change in the level of RNA-1 transcript was observed. This result indicates that IscR directly represses transcription from its own promoter.

Figure 6.

IscR represses transcription from the iscR promoter. A phosphorimage of the products from in vitro transcription reactions containing the iscR promoter plasmid, pPK6511 (2 nM) and Eσ70 (50 nM) (lanes 1 and 2). The reaction in lane 2 also contained IscR (656 nM protein; 200 nM Fe-S cluster). The arrows indicate the transcripts corresponding to iscR and RNA-1.

iscRSUA Expression Is Under the Control of the IscR-Responsive Promoter.

To test whether IscR is also a regulator of the downstream iscSUA genes, we measured β-galactosidase activity from strains containing a lacZ fusion starting from the same region 5′ to iscR but ending within iscS or at the end of iscA and containing an in-frame deletion of iscR (PiscRiscS′-lacZ and PiscRiscSUA-lacZ, respectively; Fig. 2). Regardless of the 3′ endpoint fused to lacZ, expression was increased in strains lacking IscR, demonstrating that IscR regulates transcription of the entire iscRSUA gene cluster (Fig. 3). To determine whether IscR regulates iscSUA expression from the promoter identified upstream of iscR or from an unknown promoter located within the intragenic region (115 nucleotides) between iscR and iscS, we measured β-galactosidase activity from a strain containing a lacZ fusion that was under control of the region that extends from −396 to +419 nucleotides relative to the iscS start codon (iscS′-lacZ). Overall, very little β-galactosidase activity was detected, and the iscR deletion had no effect on expression of the iscS′-lacZ fusion, suggesting that this region, which includes the 281 terminal nucleotides of iscR, has no promoter activity (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that iscSUA must be cotranscribed with iscR from the major IscR-responsive promoter.

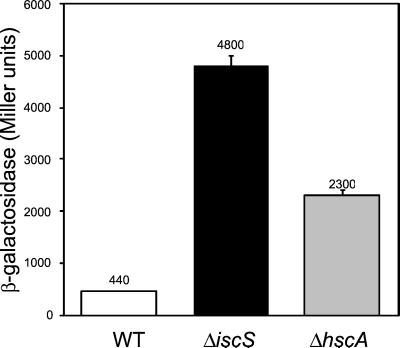

IscR Activity Is Affected by Fe-S Cluster Assembly Mutants.

IscS has been previously characterized as a cysteine desulfurase, and strains deleted for iscS display deficiencies in Fe-S cluster assembly (3–5). Therefore, we wanted to test whether the defects in Fe-S cluster assembly that occur in an iscS deletion strain would affect IscR activity. Indeed, we observed that iscR′-lacZ expression was increased in strains in which iscS was replaced with a KnR cartridge (Fig. 7). Strains containing null mutations in hscA lack Hsc66 and are defective in Fe-S cluster assembly, similar to strains containing an iscS deletion (3, 5), so we also assayed IscR activity in a strain containing an insertion in hscA (hscA2-cat). As shown in Fig. 7, iscR′-lacZ expression was also increased in cells lacking Hsc66, indicating that IscR activity was decreased. Therefore, the loss of two different gene products implicated in Fe-S cluster assembly, IscS or Hsc66, leads to increased expression from the iscR promoter, suggesting that the Fe-S cluster of IscR is important for IscR-dependent regulation. IscR activity was not completely eliminated in the ΔiscS∷KnR or the hscA2-cat strains, because the β-galactosidase levels were not as high as that in an ΔiscR strain. This finding is not surprising, because previous results showed that strains deleted for iscS or hscA still possess some residual Fe-S cluster assembly activity (5).

Figure 7.

IscR activity is decreased in strains lacking Fe-S cluster assembly proteins. β-Galactosidase activity was measured from strains containing a lacZ fusion to the iscR promoter (Fig. 2) and derivatives containing hscA2-cat or ΔiscS∷ KnR. The data represent the average activity of three independently isolated strains.

Discussion

IscS, IscU, and IscA have been implicated in facilitating Fe-S cluster assembly both in vitro and in vivo. In this study, we found that a previously uncharacterized regulator, IscR, regulates expression of the genes encoding these proteins. We have shown that IscR contains a [2Fe-2S] cluster and is a transcriptional repressor of the iscRSUA operon. Because our data also suggest that the Fe-S cluster of IscR may be important for its function as a transcriptional regulator, we propose that IscR participates in an autoregulatory loop to maintain the appropriate levels of cellular Fe-S cluster synthesis.

iscR Is Cotranscribed with iscSUA.

Our data indicate that IscR represses transcription initiation from a single promoter upstream of iscR. Both an extended −10 element and a nearly consensus −35 hexamer are present upstream of this start site (Fig. 2), consistent with this promoter being transcribed by Eσ70 RNA polymerase. In addition, we found that deletion of iscR led to derepression not only of iscR but also of iscSUA. Because no additional promoter element was identified between iscR and iscS by using lacZ fusions, the simplest interpretation of these data is that iscR is cotranscribed with iscSUA and that transcription of iscRSUA originates from a single promoter upstream of iscR that is repressed by IscR. Furthermore, the genomic organization of iscRSUA is conserved in many β- and γ-proteobacteria, or, as in the case of some Gram-positive bacteria, iscRS is conserved. This suggests that the autoregulation of Fe-S cluster assembly genes by IscR is not unique to E. coli.

IscR, a Member of the Mar/Sox/Rob Family, Functions as a Repressor.

IscR is the first MarA/Rob/SoxS family member, to our knowledge, that has been shown to directly function as a repressor. Although the exact location of the IscR-binding site(s) within the iscR promoter region is unknown, it must reside within the region from −161 to +38 nucleotides relative to the start site of transcription, because this region was sufficient for IscR to decrease transcription in vitro. Within this region (−82 to −38 nucleotides relative to the iscR transcription start site; Fig. 2), three sequences with similarity to MarA-binding sites were found (31, 32). If these represent sequences to which IscR binds, then these sites are in a position atypical for binding of a repressor. Additional studies are necessary to determine what sequences in the iscR promoter are critical for IscR DNA binding and repression and the mechanism of IscR repression.

Our finding that IscR is a repressor of iscRSUA does not exclude the possibility that IscR may also function as a transcription activator like other members of the AraC family (14). In this regard, it is important to note that we did not observe any large growth defects with the iscR deletion strain. Furthermore, Tokumoto and Takahashi (3) found that normal levels of several Fe-S proteins were present in strains deleted for iscR. Together, these data indicate that if IscR does have other targets, changes in their expression apparently cause no large growth defects or large changes in levels of Fe-S proteins.

Expression of hscBAfdx.

Downstream of the isc operon are the genes encoding a ferredoxin and the chaperone homologs, Hsc66 and Hsc20, which have also been implicated in promoting Fe-S cluster assembly (1). Although it is logical to hypothesize that expression of these genes may also be under the control of the major IscR-responsive promoter, two independent transcription start sites have been previously mapped upstream of each of the hsc genes, suggesting that they may be transcribed separately from the isc genes (33, 34). However, in some bacteria, such as Azotobacter vinelandii (1), the intergenic space between the iscA and hscB is smaller than in E. coli, leaving open the possibility that, in such cases, the Fe-S cluster assembly genes may be cotranscribed. Experiments that address whether hscBAfdx expression is regulated by IscR in E. coli should provide additional insight as to how expression of these genes is controlled.

The Role of the [2Fe-2S] Cluster in Controlling IscR Function.

Our finding that IscR contains a [2Fe-2S] cluster raises the question of how this cluster might function in regulation of IscR repressor activity. The observation that IscR activity is decreased in mutants lacking the Fe-S cluster assembly proteins, IscS and Hsc66, has led us to consider that the ability of IscR to function as a repressor depends on whether it contains a [2Fe-2S] cluster. This is a particularly attractive hypothesis, because the three IscR cysteine residues, which may coordinate the Fe-S cluster, are located in a region that in MarA separates the two helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motifs (14). Thus, if IscR has DNA-binding domains organized in a manner similar to other members of this family, the presence of the Fe-S cluster might affect IscR repressor function by influencing its DNA binding activity. In this case, we would expect that IscR is a monomer like other members of this family (14) and contains one [2Fe-2S] cluster, although this hypothesis has not been tested experimentally. This model would also imply that the [2Fe-2S] cluster would have one noncysteinyl ligand, because only three Cys are present in IscR. Nevertheless, it is also possible that the oxidation state of the cluster further modulates IscR function as has been found with the [2Fe-2S]-containing transcription factor, SoxR (35). However, preliminary experiments suggest that oxidation of IscR does not cause any large changes in the ability of IscR to repress the iscR promoter in vitro (data not shown).

Nonetheless, the finding that IscR activity is decreased in mutants lacking the Fe-S cluster assembly proteins, IscS and Hsc66, has led us to consider that there may be a link between the levels of [2Fe-2S] IscR and the rate of Fe-S cluster formation catalyzed by the Fe-S cluster assembly proteins. This type of homeostatic model would predict that when Fe-S cluster assembly becomes rate limiting (i.e., all Isc proteins are engaged in Fe-S cluster assembly), levels of [2Fe-2S] IscR would decrease as a result of a diminution in its rate of synthesis, and repression of iscRSUA would be relieved. The resulting increase in the Isc assembly proteins would subsequently lead to an increase in the rate of Fe-S cluster formation, causing levels of [2Fe-2S] IscR to rise, thus reestablishing repression of the isc operon. If this model were correct, then we would expect that Fe-S clusters would be assembled only when there is a need. For example, it predicts there would be an increase in Fe-S cluster synthesis in response to conditions known to damage Fe-S clusters, such as oxidative stress. In support of this notion, it has been recently reported that iscR expression is increased by high external concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (1 mM) (36).

In summary, we have presented data showing that IscR is a transcriptional repressor of iscRSUA. This repression appears to depend on the Fe-S cluster assembly proteins, providing a mechanism by which Fe-S cluster assembly can be coupled to cellular requirements for synthesis or repair of Fe-S proteins. Because the synthesis or repair of individual Fe-S cluster proteins is subject to input from a variety of physiological and environmental signals, this type of mechanism would provide an additional level of global regulation to ensure that Fe-S clusters are synthesized when there is an increased demand. Future work will aim to elucidate the mechanism of IscR repression, determine whether other targets exist for IscR, and study how the activity of this protein is modulated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dennis Dean (Virginia Polytechnic Institute) for pointing out the similarity of IscR to MarA, Larry Vickery (University of California, Irvine) for providing the hscA− strain, Barry Wanner (Purdue University) and colleagues for advice in making deletion strains, Lindy Walter (University of Wisconsin) for construction of pPK5960, Carol Gross (University of California, San Francisco) for the RNA isolation protocol, and Timothy Donohue (University of Wisconsin) for critically reading this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant GM-45844 and a Shaw Scientist award from the Milwaukee Foundation (P.J.K.). J.L.G. was a trainee of the NIH Biotechnology Predoctoral Training Grant GM08349 to the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Abbreviation

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

Footnotes

See commentary on page 14751.

References

- 1.Zheng L, Cash V L, Flint D H, Dean D R. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13264–13272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mühlenhoff U, Lill R. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1459:370–382. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tokumoto U, Takahashi Y. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2001;130:63–71. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skovran E, Downs D M. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3896–3903. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.14.3896-3903.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz C J, Djaman O, Imlay J A, Kiley P J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9009–9014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160261497. . (First Published July 25, 2000; 10.1073/pnas.160261497) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agar J N, Zheng L, Cash V L, Dean D R, Johnson M K. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:2136–2137. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flint D H. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16068–16074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agar J N, Krebs C, Frazzon J, Huynh B H, Dean D R, Johnson M K. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7856–7862. doi: 10.1021/bi000931n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ollagnier-de-Choudens S, Mattioli T, Takahashi Y, Fontecave M. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22604–22607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoff K G, Silberg J J, Vickery L E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7790–7795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130201997. . (First Published June 27, 2000; 10.1073/pnas.130201997) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agar J N, Yuvaniyama P, Jack R F, Cash V L, Smith A D, Dean D R, Johnson M K. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2000;5:167–177. doi: 10.1007/s007750050361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patschkowski T, Bates D M, Kiley P J. In: Bacterial Stress Responses. Storz G, Hengge-Aronis R, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 2000. pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storz G, Imlay J A. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:188–194. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin R G, Rosner J L. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:132–137. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang A C, Cohen S N. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubendorff J W, Studier F W. J Mol Biol. 1991;219:45–59. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90856-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simons R W, Houman F, Kleckner N. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choe M, Reznikoff W S. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6139–6146. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.6139-6146.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mousset S, Thomas R. Nature (London) 1969;221:242–244. doi: 10.1038/221242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Datsenko K A, Wanner B L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. . (First Published May 30, 2000; 10.1073/pnas.120163297) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singer M, Baker T A, Schnitzler G, Deischel S M, Goel M, Dove W, Jaacks K J, Grossman A D, Erickson J W, Gross C A. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:1–24. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.1-24.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller J H. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erickson J W, Gross C A. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1462–1471. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lonetto M A, Virgil R, Lamberg K, Kiley P, Busby S, Gross C. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:1353–1365. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bates D M, Popescu C V, Khoroshilova N, Vogt K, Beinert H, Münck E, Kiley P J. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6234–6240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennedy M C, Kent T A, Emptage M, Merkle H, Beinert H, Münck E. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:14463–14471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beinert H. Anal Biochem. 1983;131:373–378. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khoroshilova N, Popescu C, Münck E, Beinert H, Kiley P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6087–6092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beinert H, Orme-Johnson W H, Palmer G. In: Methods in Enzymology. Colowick S P, Kaplan N O, editors. LIV. New York: Academic; 1978. pp. 111–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer G. Iron–Sulfur Proteins. New York: Academic; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin R G, Gillette W K, Rhee S, Rosner J L. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:431–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barbosa T M, Levy S B. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3467–3474. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.12.3467-3474.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lelivelt M J, Kawula T H. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4900–4907. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4900-4907.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seaton B L, Vickery L E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2066–2070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hidalgo E, Ding H, Demple B. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng M, Wang X, Templeton L J, Smulski D R, LaRossa R A, Storz G. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4562–4570. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.15.4562-4570.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]