Abstract.

In the panorama of the numerous established cell lines, the human keratinocyte line HaCaT has a very interesting feature, having a close similarity in functional competence to normal keratinocytes. This cell line has been used in many studies as a paradigm for epidermal cells and therefore we selected HaCaT as a cell model for investigating the activity of three antitopoisomerase drugs (Camptothecin, Doxorubicin, Ciprofloxacin) on in vitro cell growth. The effect was evaluated both by a 24‐h cytotoxicity test and by a 7‐day antiproliferation assay, in which the cell viability was assessed by an MTT (3‐(4,5‐dimethyl‐2‐thiazolyl) 2,5‐diphenil‐2‐H‐tetrazolium bromide) test. DNA topoisomerase I was also partially purified from a nuclear extract of HaCaT cells, the level of topo I catalytic activity was measured by a pBR322 DNA relaxation assay and then the in vitro effect of antitopoisomerase drugs on the target enzyme was also assessed.

The results indicated that the in vitro sensitivity of human epidermal HaCaT cells to antitopoisomerase drugs is comparable to that of many human tumour cell lines. HaCaT cells express a high level of topoisomerase I activity that is significantly inhibited by both Camptothecin and Doxorubicin and to a minor degree by Ciprofloxacin. A high correlation between the cell sensitivity to the antitopoisomerase I drug measured by the MTT test and the in vitro direct inhibition of HaCaT topoisomerase I was observed, suggesting that HaCaT cells can represent a very interesting model both for studying cellular pharmacokinetics of antineoplastic drugs on keratinocytes and for predicting possible secondary effects, exerted by these drugs on cutaneous cells, during treatment with chemotherapy.

Introduction

Eukaryotic topoisomerase I is a nuclear enzyme capable of introducing transient breaks in one strand of doubled‐strand DNA (Wang 1985). This enzyme is involved in many DNA functions such as replication, transcription and recombination mechanisms (Parchment & Pessina 1998) and has been shown to be the target of antineoplastic drugs of the Camptothecin group (Hsiang et al. 1985), which act by stabilizing the covalent complex between the single‐strand DNA break and the topoisomerase I molecule. As is well documented, cells expressing high levels of topoisomerase I are more sensitive to antineoplastic drugs of the Camptothecin group than cells with low topoisomerase I levels (Bronstein et al. 1996). This has been documented by Masin et al. (1995), who reported that in solid cutaneous tumours of the head and neck the activity of topoisomerase I is increased about 60‐fold compared to normal tissue. As stated by Breitkreutz et al. (1998), HaCaT cells appear to express an epidermal phenotype in a natural environment by responding to regulating signals in a similar way to normal keratinocytes and are therefore highly suitable for in vitro studies on structural and regulatory aspects of keratinocyte physiology and pathology. This close similarity in the functional competence of HaCaT cells to normal keratinocyte makes this line a good in vitro human model of established cells for investigating the intracellular levels and activities of topoisomerase I in cutaneous cells.

In this context, to further validate this cell model, our study has made a preliminary characterization of the HaCaT keratinocyte cell line by comparing the cytotoxic and antiproliferative sensitivities of HaCaT cells to three drugs with antitopoisomerase activity (Camptothecin, Doxorubicin and Ciprofloxacin). As control drugs we used two polyenes (Amphotericin B and a Partricin A derivative), having direct cytotoxic activity but unable to interfere with cell proliferation. Furthermore, the topoisomerase I catalytic activity of HaCaT cells has been determined and the direct in vitro effect of the three antitopoisomerase drugs against the enzyme activity has also been studied.

Materials and methods

Drugs and chemicals

The topoisomerase inhibitors used were Doxorubicin (DXR, MW: 580) (Fluka, Milwaukee, WI, USA), Camptothecin (CAM, MW: 348) (Fluka, Milwaukee, WI, USA) and Ciprofloxacin (CPX, MW: 348) (Bayer, Wuppertal, Germany). For comparison, two polyene antifungal molecules were tested: Amphotericin B (ATB, MW: 924.1) (Bristol–Myers–Squibb, USA) and a Partricin A derivative (PTA, MW: 1633.8) (SPA, Milan, Italy), which do not affect topoisomerases. Supercoiled plasmid pBR322 DNA for testing topoisomerase I activity was purchased from SIGMA (St Louis, MS, USA).

Cells and culture conditions

The HaCaT cell line is a spontaneously transformed human epithelial cell line developed by Boukamp et al. (1988), generously provided by Prof. N. Fusenig (DKFZ, Heidelberg, Germany). These cells are known to produce in vitro stem cell factor (SCF), platelet aggregating factor (PAF) and IL‐6 (induced by TNFα stimulation) as well as two autocrine growth inhibitors: TGFβ and TCFBP‐6 (Kato et al. 1995). The line has been maintained in our laboratory by 1:6 weekly passage in MEM supplemented with 10% FCS and antibiotics (penicillin 100 U/ml + streptomycin 100 µg/ml). In these conditions we studied the basal growth kinetics of the cell line for the determination of the best standardized growth conditions to perform both the cytotoxicity test and topoisomerase I extraction at passage number 27.

The cell growth was estimated by counting the number of cells in a haemocytometer and the main growth parameters were evaluated as suggested by McAteer & Davis (1994). The in vitro sensitivity to DXR, CAM and CPX was compared to WEHI‐3B cells (murine myelomonocytic leukaemia) maintained by serial passages in our laboratory (Warner et al. 1969).

In vitro growth inhibition assay

The in vitro sensitivity of HaCaT cells to the drugs has been tested by assessing cell viability both in a 24‐h cytotoxicity test (30 000 cells/well) and in a 7‐day antiproliferation test (with a inoculum of 103 cells/well) according to a modification of the MTT assay (Mossman 1983; Pessina et al. 1994). The degree of sensitivity has been studied by comparing the IC50 values (drug concentration able to induce a 50% reduction of cell viability) determined for each drug in the two tests.

Topoisomerase extraction

The nuclear extract from exponentially growing HaCaT cells was prepared according to the method suggested by Deffie et al. (1989). Briefly, 40 × 106 cells were collected after 72 h of cultures (starting inoculum of 104 cells/ml), washed and resuspended in 1 ml of nuclear buffer (NB = 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm KH2PO4, 1 mm EDTANa2 10% glycerol) supplemented with 0.35% Triton X‐100, 1 mm phenylmethyl‐sulphonyl‐fluoride (PMSF) and 0.2 mm DTT (pH adjusted to 6.5). Cell suspension was mixed, maintained for 10 min at 4 °C and then centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min to isolate nuclei. The nuclear pellet was suspended in Triton X‐free NB, and nuclear proteins were extracted by adding 5 m NaCl to a final concentration of 0.35 m and treating for 30 min at 4 °C. DNA and nuclear debris were pelleted by centrifugation at 17 000 g for 10 min and the supernatant was collected. The protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (1976) and the extracts were adjusted to a final protein concentration of 25 µg/ml. Glycerol (1:1 v/v) was added to the extracts to a final concentration of 50% and aliquots of 100 µl were stored at −80 °C (used within 2 months).

Topoisomerase I relaxation assay

The catalytic activity of topoisomerase I was determined by pBR322 DNA relaxation assay performed in the absence of ATP and Mg++ ions (Drake et al. 1989). Briefly, to 20 µl reaction mixture containing 50 mm Tris HCl pH 7.5, 1 mm 2‐ME, 165 mm KCl, 0.5 mm EDTA‐Na2 and 30 µg/ml BSA, 150 ng pBR322 DNA, 5 µL (4 U/ml) nuclear extract and 5 µL drug were added to a final concentration ranging from 0.187 µg/ml to 30 µg/ml (CAM, DXR) and from 31.5 µg/ml to 500 µg/ml (CPX) and were then incubated at 37 °C for 10 min The reaction was stopped by adding 10 µl SDS 10% + 250 mm EDTA + 0.8 ng/ml Proteinase K and samples were incubated at 50 °C for 30 min to digest the enzyme. The final products were mixed with loading solution (BBF 0.25% + 60% sucrose) and subjected to electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel in 40 mm Tris‐acetate buffer. Gel was stained with ethidium bromide and photographed by UV light through Kodak filters with a Polaroid type 665 positive‐negative film. The amount of DNA was quantified by scanning the photographic negatives with a densitometer and measuring the relaxed DNA.

One unit of topoisomerase I activity is the quantity of extract required to relax 50% of 150 ng of pBR322 DNA in 10 min at 37°. The direct inhibitory effect on topoisomerase I has been evaluated by testing increasing concentrations of drugs in the presence of an amount of nuclear extract corresponding to 5 U topoisomerase I activity. The inhibition has been expressed as the drug concentration able to produce a 50% inhibition of topoisomerase I activity (IC50).

Immunoblotting

A sample of nuclear extract prepared as described above was subjected to electrophoresis in 7.5% SDS polyacrylamide gel by the method of Laemmli (1970) and then transferred to nitrocellulose filters essentially as described by Towbin et al. (1979). After incubation in 5% dry milk in PBS, the blot was washed with PBS and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with the serum of a scleroderma patient, containing antitopoisomerase I antibodies (Shero et al. 1986) and diluted 1:1500 in 5% dry milk–PBS. After washing with PBS + Tween 0.3%, the blot was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with an antihuman IGG peroxidase conjugate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) diluted 1:5000 in PBS–5% dry milk. After further washing, the blot was developed by an enhanced chemiluminescence technique (ECL) (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK), Western blotting detecting reagents and Hyperfilm ECL (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK). As a positive control a sample of purified human Topo I (TopoGEN, Columbus, OH, USA) was subjected to electrophoresis and then immunoblotted as described above.

Immunoperoxidase staining

The expression of nuclear topoisomerase I has been verified on acetone‐fixed cytospins of the HaCaT cell line using the serum of a scleroderma patient diluted 1:2000. The reaction was revealed by a peroxidase‐labelled rabbit antiserum specific for human IgG (Dako, Clostrupp, DK) diluted 1:100, followed by tyramide signal amplification (DuPont/NEN, Boston, MA, USA) and development with diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Sigma, St Louis, MS, USA). Patient sera and peroxydase‐labelled rabbit antihuman IgG were diluted in 0.05 m TBS (Tris‐buffered saline, pH 7.2) containing 1% BSA (bovine serum albumine, fraction V, Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MS, USA) and 0.001% Nonidet P‐40 (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MS, USA).

Data analysis

The IC50 values were determined by the Reed & Muench (1938) formula. The data were statistically analysed using the Instat Programme (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA), and where required the means were compared using a bidirectional Student t‐test and the differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

HaCaT cell growth

After a 104 cells/ml inoculum, HaCaT cells showed a lag phase of 24–48 h, a population doubling time (PDT) of 26.4 h and a cell density at confluence of 105 cells/cm2. These preliminary results have been used to select the best experimental conditions for investigating both cytotoxicity (at 24 h) and antiproliferation activity (7 days) of the drugs. The 7‐day proliferation test was set to obtain a range of optical densities (OD) from 0.1 to 0.8 in a multiwell colourimetric assay (MTT) able to discriminate cell densities from 2500 to 40 000 cells/well (data not shown). Optimal growth conditions were also chosen to harvest cells for topoisomerase I extraction.

In vitro drug sensitivity of HaCaT cells

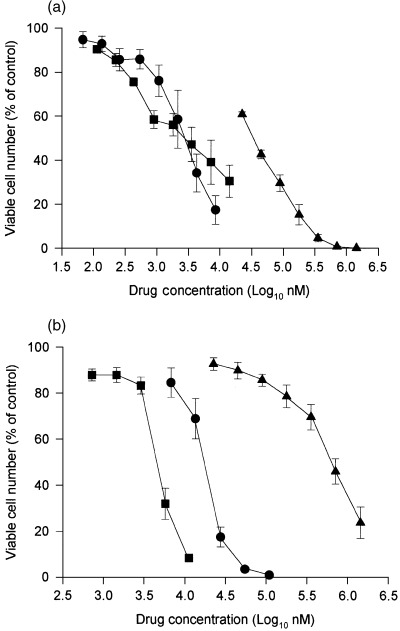

The in vitro sensitivity of HaCaT cells to Doxorubicin, Camptothecin and Ciprofloxacin is reported in Figs 1a and b. Both the cytotoxicity and the antiproliferation tests show a concentration‐dependent inhibition of cell growth, although with a different degree of efficacy as expressed by the different IC50 values, which are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Effects of Doxorubicin, Camptothecin and Ciprofloxacin on in vitro HaCaT cell growth. The cell growth is expressed as a percentage of the OD measured on untreated cells (Control) assumed as 100% of cell viability. (a) Cytotoxic activity measured by a 24‐h test. (b) Antiproliferative activity measured by a 7‐day proliferation test. Circles: Doxorubicin; squares: Camptothecin; triangles: Ciprofloxacin. Each value represents the mean ± SE of three experiments performed in triplicate.

Table 1.

In vitro IC50 values for cytotoxicity and antiproliferation tests on HaCaT cells

| Drug | Cytotoxicity test (IC50 in µm) | Antiproliferation test (IC50 in µm) | IC50 ratio: cytotoxic/antiproliferative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Camptothecin | 3.02 (1) a | 0.0051 (1) | 592.16 |

| Doxorubicin | 2.72 (0.9) | 0.017 (3.33) | 160 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 658 (217.8) | 35.72 (7003.92) | 18.42 |

| Partricin A | 97.9 (32.4) | 5.8 (1137.2) | 16.8 |

| Amphotericin B | 102.9 (34.1) | 29.3 (5745.1) | 3.51 |

a Numbers in brackets are the ratios calculated using the CAM IC 50 value.

In the cytotoxicity test, Camptothecin and Doxorubicin show very similar IC50 values, whereas Amphotericin B, Partricin A and Ciprofloxacin are, respectively, 32.4, 34.1 and 217.8 times less active. In the antiproliferation test these ratios are dramatically higher, ranging from an activity of about 1000‐fold (Partricin A) to 6000–7000‐fold for Amphotericin B and Ciprofloxacin. The drug sensitivity of HaCaT cells determined in the two different assays (expressed as a ratio between the IC50 values cytotoxicity:antiproliferation) shows high ratios for DXR (160 times) and CAM (592.16 times), whereas for the other drugs the ratio ranged from 3.5 to 18.4.

Topoisomerase I expression by HaCaT cells

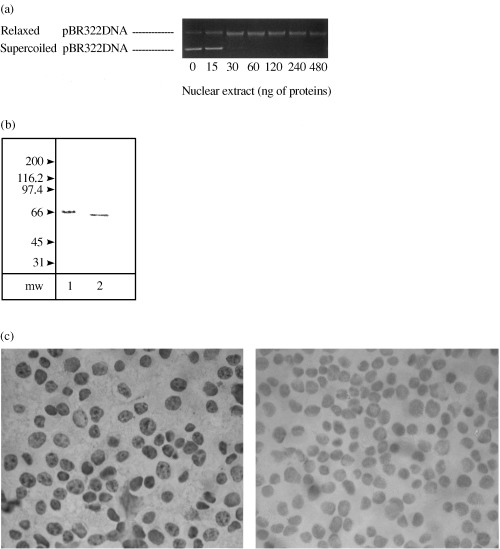

Figure 2a reports the densitometric scanning of agarose gels. The quantitative analysis of the bands of relaxed DNA has been used to calculate the specific catalytic activity of topoisomerase I in the nuclear extract of HaCaT cells, which was 55 000 + 7300 U/mg.

Figure 2.

Topoisomerase I from HaCaT cells. (a) The bands of relaxed DNA were quantified by densitometric scanning for determination of the specific catalytic activity of topoisomerase I (see Materials and methods). (b) Immunoblot analysis of topoisomerase I protein from nuclear extract of HaCaT cells (lane 2). The migration positions of Mr markers (kDa) are indicated. Lane 1 = human standard preparation of topoisomerase I from TopoGEN (positive control). (c) Immunoperoxidase staining of whole HaCaT cells treated with antitopoisomerase I antibodies (right‐hand side). The left‐hand photo shows a negative control with cells untreated with antibodies (100 × magnification).

Topoisomerase I immunoblotting is shown in Fig. 2b and is characterized by a 66 kDa band (lane 2) that represents the common breakdown product of the intact 100 kDa protein (Liu & Miller 1981; Florell et al. 1996). Lane 1 shows the positive control, consisting of a preparation of human topoisomerase I purchased from TopoGEN (Columbus, OH, USA).

Figure 2c reports the level of the expression of topoisomerase I determined by immunoperoxidase staining on whole cells. The enzyme is localized into the nuclei of almost 90% of HaCaT cells (showing specific immunostaining of topoisomerase I).

Direct effect of drugs on topoisomerase I

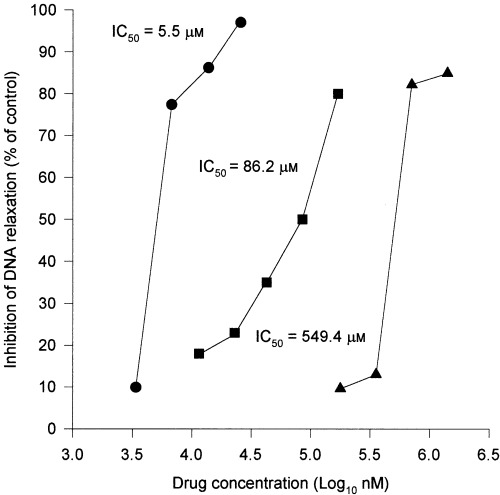

The graphs in Fig. 3 show the direct inhibition exerted by drugs on the in vitro activity of topoisomerase I expressed as a percentage decrease of relaxed DNA quantified by densitometric scanning. The topoisomerase I relaxing activity is inhibited strongly by Doxorubicin (IC50 = 5.5 µm) and Camptothecin (IC50 = 86.2 µm) and to a minor degree by Ciprofloxacin (IC50 = 549.4 µm).

Figure 3.

In vitro inhibition of catalytic activity of topoisomerase I from HaCaT cells. Effect of Doxorubicin, Camptothecin and Ciprofloxacin on in vitro catalytic activity of topoisomerase I. The inhibition is expressed as a percentage decrease of relaxed DNA (identified by densitometric scanning). Circles: Doxorubicin; squares: Camptothecin; triangles: Ciprofloxacin.

Discussion

In the absence of mechanisms of resistance such as the expression of proteins involved in drug efflux pumps (P‐gp, MRP, LRP, etc.) and several other mechanisms (Beck 1987; Scheper et al. 1993; Clynes 1994; Pratt et al. 1994), the cell sensitivity to topoisomerase I targeted drugs could depend solely on the cellular amount of enzyme. Therefore, cells with elevated amounts of topoisomerase I are more sensitive to topoisomerase I poisons such as Camptothecin than cells having low levels of this enzyme (Bronstein et al. 1996). The average of topoisomerase I activity in normal mammalian tissue is reported to be about 2–3 × 104 U/mg, whereas in some tumours such as those in the cervix and human colon, topoisomerase I activity is relatively higher (2–3‐fold) in comparison to non‐small‐cell lung cancer and breast cancer (McLeod et al. 1994). Our data show that HaCaT cells have a remarkably high level of topoisomerase I activity that is sensitive to topoisomerase poisons, as confirmed by the high ratios between the IC50 values determined in the cytotoxicity test and that calculated from the antiproliferative test (see Table 1). In fact, as the 7‐day test measures a combination of the cytotoxicity and decreased proliferation, the high IC50 ratios demonstrate that the inhibition of cell growth is consistent with strong interference with cell cycle proliferation (this seems to be more effective with DXR than with CAM). On the other hand, the low ratios observed for Partricin A, Amphotericin B and Ciprofloxacin are a confirmation that these drugs may act as cytotoxic agents but do not play a very significant role in cell proliferation (while CAM and DXR do, very efficiently). However, Ciprofloxacin seems to be a drug able to interfere with cell proliferation, although in a minor degree.

In Table 2 we report data in the literature on the sensitivity of different tumour cell lines to CAM and DXR. According to the observations of Kapoor et al. (1995), human T‐leukaemia CCRF/CEM is more sensitive to CAM (IC50 = 8.1 nm) than to DXR (IC50 = 103 nm), while non‐small‐cell lung carcinoma H460 shows the same sensitivity to CAM and DXR, with IC50 values of 4.9 and 4.2 nm, respectively. Jurkat leukaemia cells are also very similar, with 5.6 nm for CAM and 9.6 nm for DXR (Bridewell et al. 1997).

Table 2.

Sensitivity of different cell lines to the in vitro antiproliferative effect of Camptothecin (CAM) and Doxorubicin (DXR) expressed as IC50 values

| Cell type | CAM | DXR | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCRF/CEM (T cell lymphoblastic leukaemia) | 8.1 nm | 103 nm | (Kapoor et al. 1995) |

| 2.2 nm | 29 nm | (Riou et al. 1993) | |

| KB (nasopharingeal Ca) | 9.8 nm | (Beidler et al. 1996) | |

| JURKAT (acute T‐cell leukaemia) | 5.6 nm | 9.6 nm | (Bridewell et al. 1997) |

| H460 (non‐small‐cell lung Ca) | 4.9 nm | 4.2 nm | (Bridewell et al. 1997) |

| U937 (monoblastic leukaemia) | 420 nm | (Bridewell et al. 1997) | |

| N‐417 (small‐cell lung Ca) | 200 nm | 20 nm | (Prost & Riou 1994) |

| HaCaT | 4.9 nm | 17 nm (epithelial cells) | |

Taken together, our results are very interesting because they show that HaCaT cells (which are not tumoral cells) are very sensitive to CAM (IC50 = 5.1 nm), showing a susceptibility very similar to that of tumour cell lines such as KB, Jurkat, CCRF/CEM and H460 (see Table 2) and about eight times higher than for human monoblastic leukaemia (U937). A further very surprising observation is that HaCaT cells show a susceptibility to DXR (IC50 = 17 nm) six times higher than that reported for T‐cells lymphoblastic leukaemia. As DXR is considered to be a topoisomerase II poison rather than topoisomerase I, it will be of interest to investigate the meaning of this sensitivity, and our laboratory is currently involved in investigating this aspect.

The high value of the PDT (26.4 h) of HaCaT cells may explain in part their minor degree of sensitivity with respect to other cell types that have a lower PDT such as the above‐mentioned CEM cells (21.2 h) or WEHI‐3B cells (18 h), cells that in our laboratory have been compared with HaCaT for CAM, DXR and CPX sensitivity (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of IC50 determined by antiproliferation and antitopoisomerase tests on HaCaT and WEHI‐3B cells

| Drug | Antiproliferation test | Antitopoisomerase I test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WEHI‐3B (µm) | HaCaT (µm) | WEHI‐3B (µm) | HaCaT (µm) | |

| Doxorubicin | 0.13 | 0.017 | 0.3 (2.3) a | 5.5 (323.5) |

| Camptothecin | 0.0069 | 0.0051 | 50.41 (7246) | 86.2 (18862) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 87.35 | 35.72 | 302.9 (3.46) | 548 (15.3) |

a Numbers in brackets are the ratios of the IC 50 values (antitopoisomerase I:antiproliferation test).

The in vitro sensitivity to CAM of topoisomerase I from HaCaT cells (IC50 = 86.2 µm) is 7–10 times lower than that observed by Danks et al. (1988) in CCRF/CEM (IC50 = 11 µm) and by Florell et al. (1996) in a human malignant lymphoma (IC50 = 8 µm).

If the in vitro drug sensitivity of topoisomerase I from HaCaT and WEHI‐3B cells is compared with the drug sensitivity of the whole cells (see Table 2), the high activity of these drugs on HaCaT proliferation is apparently confirmed. However, whereas the whole cells are more sensitive to CAM than DXR, DNA topoisomerase I shows a higher sensitivity towards DXR than towards CAM (in both HaCaT and WEHI‐3B cells). Furthermore, while in the antiproliferative test DXR is eight times more active on HaCaT than on WEHI‐3B cells, in the in vitro antitopoisomerase I test, this ratio is reversed. These discrepancies may depend on the fact that although the DXR is active on topoisomerase I, the most important poison mechanism of DXR is its antitopoisomerase II activity (rather than antitopoisomerase I), whereas CAM is only active on topoisomerase I. These observations taken together indicate and confirm that the actual expression of cytotoxicity on cell proliferation is strongly dependent on the different cellular pharmacokinetics.

As HaCaT cells have a very high topoisomerase I activity and show a remarkable sensitivity to the antiproliferative action of drugs affecting topoisomerases, this line may represent a good in vitro established cutaneous model cell line for testing topoisomerase I inhibitors by a simple in vitro antiproliferative test such as MTT assay by extending the previous observations of Brosin et al. (1997), who suggested using these cells for the screening of irritating substances.

Of particular interest, we consider the possibility that HaCaT cells may work as a good model for studying cellular pharmacokinetics of neoplastics drugs on keratinocytes, also helping to predict possible secondary effects (for example, on cytokine production or other regulatory functions) on cutaneous cells exerted by drugs in the course of anticancer chemotherapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms Loredana Cavicchini for her excellent technical assistance and Prof. Martin Clynes (Dublin City University, Ireland) for critically reading the manuscript.

References

- Beck WT (1987) The cell biology of multiple drug resistance. Biochem. Pharmacol. 36, 2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidler DR, Chang J‐Y, Zhou B, Cheng Y (1996) Camptothecin resistance involving steps subsequent to the formation of protein‐linked DNA breaks in human camptothecin‐resistant KB cell lines. Cancer Res. 56, 345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukamp P, Rule T, Breitkreutz D, Hornung J, Markham A, Fusenig NE (1988) Normal keratinization in a spontaneous imortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J. Cell Biol. 106, 761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248DOI: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitkreutz D, Schoop VM, Mirancea N, Baur M, Stark H‐J, Fusenig NE (1998) Epidermal differentiation and basement membrane formation by HaCaT cells in surface transplants. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 75, 273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridewell DJA, Finlay GJ, Baguley BC (1997) Differential actions of Aclarubicin and Doxorubicin: the role of topoisomerase I. Oncol. Res. 9, 535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein IB, Vorobyev S, Timofeev A, Jolles CJ, Alder SL, Holden JA (1996) Elevations of DNA topoisomerase I catalytic activity and immunoprotein in human malignancies. Oncol. Res. 8, 17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosin A, Wolf V, Mattheus A, Heise H (1997) Use of XTT‐assay to assess the cytotoxicity of different surfactants and metal salts in human keratinocytes (HaCaT). A feasible method for in vitro testing of skin irritants. Acta Derm. Venereol. 77, 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clynes M (1994) Multiple Drug Resistance in Cancer: Cellular, Molecular and Clinical Approaches. London: Kluwer Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Danks MK, Schmidt CA, Cirtain MC, Suttle DP, Beck WT (1988) Altered catalytic activity of and DNA cleavage by DNA topoisomerase II from human leukemic cells selected for resistance to VM‐26. Biochemistry 27, 8861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffie AM, Batra JK, Goldenberg GJ (1989) Direct correlation between DNA topoisomerase II activity and cytotoxicity in Adryamicin‐sensitive and resistant P388 leukemia cell lines. Cancer Res. 49, 58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake H et al. (1989) In vitro and intracellular inhibition of topoisomerase II by the antitumor agent merbarone. Cancer Res. 49, 2578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florell SR, Martinchick JF, Holden JA (1996) Purification of DNA topoisomerase I from the spleen of a patient with non‐Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Anticancer Res. 16, 3467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiang YH, Herzberg R., Hecht S, Liu LF (1985) Camptothecin induces protein linked DNA breaks via mammalian DNA topoisomerase. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 14873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor R., Slade DL, Fujimori A, Pommier Y, Harker WG (1995) Altered Topoisomerase I expression in two subclones of human CEM leukemia selected for resistance to camptothecin. Oncol. Res. 7, 83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M et al. (1995) A human keratinocyte cell line produces two autocrine growth inhibitors, transforming growth factor‐β and insulin‐like growth factor binding protein‐6, in a calcium‐ and cell density‐dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 12373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of the bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LF & Miller KG (1981) Eukaryotic DNA topoisomerases: Two forms of type I DNA topoisomerases from HeLa cell nuclei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78, 3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masin JS, Berger JJ, Setrakian S, Stepnick DW, Berger NA (1995) Topoisomerase I activity in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope 105, 1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAteer JA & Davis J (1994) Basic cell culture technique and the maintenance of cell lines In: Davis JM, ed. Basic Cell Culture, p. 93 Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod HL et al. (1994) Topoisomerase I and II activity in human breast, cervix, lung and colon cancer. Int. J. Cancer 59, 607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman T (1983) Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and citotoxicity assay. J. Immunol. Methods 65, 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parchment RE & Pessina A (1998) Topoisomerase I inhibitors and drug resistance. Cytotechnology 27, 149DOI: 10.1023/a:1008008719699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessina A, Gribaldo L, Mineo E, Neri MG (1994) In vitro short‐term and long‐term cytotoxicity of fluoroquinolones on murine cell lines. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 32, 113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WB, Rubbon RW, Ensminger WD, Maybaum J (1994) The Anti‐Cancer Drugs, 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prost S & Riou G (1994) A human small cell lung carcinoma cell line, resistant to 4′‐(9‐acridinylamino)‐methanesulfon‐m‐anisidide and cross‐resistant to camptothecin with a high level of topoisomerase I. Biochem. Pharmacol. 48, 975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ & Muench H (1938) A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27, 493. [Google Scholar]

- Riou JF et al. (1993) Intoplicine (RP, 60475) and its derivatives, a new class of antitumor agents inhibiting both topoisomerase I and topoisomerase II activities. Cancer Res. 53, 5987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper RJ et al. (1993) Overexpression of a 110 kD vesicular protein in non‐P‐glycoprotein mediated multidrug resistance. Cancer Res. 53, 1475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shero JH, Bordwel B, Rothfield NF, Earnshaw WC (1986) High titres of autoantibodiesto topoisomerase I (Scl‐70) in sera from scleroderma patient. Science 231, 737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J (1979) Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76, 4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JC (1985) DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 54, 665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner LN, Moore MAS, Metcalf D (1969) A transplantable myelomonocytic leukemia in Balb/C mice: cytology, caryotype and neuroaminidase content. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 43, 963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]