Abstract

Objectives

Tet (ten‐eleven translocation) protein 1 is a key enzyme for DNA demethylation, which modulates DNA methylation and gene transcription. DNA methylation and histone methylation are critical elements in self‐renewal of male germline stem cells (mGSCs) and spermatogenesis. mGSCs are the only type of adult stem cells able to achieve intergenerational transfer of genetic information, which is accomplished through differentiated sperm cells. However, numerous epigenetic obstacles including incomplete DNA methylation and histone methylation dynamics make establishment of stable livestock mGSC cell lines difficult. The present study was conducted to detect effects of DNA methylation and histone methylation dynamics in dairy goat mGSCs self‐renewal and proliferation, through overexpression of Tet1.

Materials and methods

An immortalized dairy goat mGSC cell line bearing mouse Tet1 (mTet1) gene was screened and characteristics of the cells were assayed by quantitative real‐time PCR (qRT‐PCR), immunofluorescence assay, western blotting, fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) and use of the cell counting kit (CCK8) assay.

Results

The screened immortalized dairy goat mGSC cell line bearing mTet1, called mGSC‐mTet1 cells was treated with optimal doxycycline (Dox) concentration to maintain Tet1 gene expression. mGSC‐mTet1 cells proliferated at a significantly greater rate than wild‐type mGSCs, and mGSCs‐specific markers such as proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), cyclinD1 (CCND1), GDNF family receptor alpha 1 (Gfra1) and endogenic Tet1, Tet2 were upregulated. The cells exhibited not only reduction in level of histone methylation but also changes in nuclear location of that methylation marker. While H3K9me3 was uniformly distributed throughout the nucleus of mGSC‐mTet1 cells, it was present in only particular locations in mGSCs. H3K27me3 was distributed surrounding the edges of nuclei of mGSC‐mTet1 cells, while it was uniformly distributed throughout nuclei of mGSCs. Our results conclusively demonstrate that modification of mGSCs with mTet1 affected mGSC maintenance and seemed to promote establishment of stable goat mGSC cell lines.

Conclusions

Taken together, our data suggest that Tet1 had novel and dynamic roles for regulating maintenance of pluripotency and proliferation of mGSCs by forming complexes with PCNA and histone methylation dynamics. This may provide new solutions for mGSCs stability and livestock mGSC cell line establishment.

Introduction

Male germline stem cells (mGSCs), also known as spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs), are able to maintain their numbers through self‐renewal even as they differentiate into sperm. The mGSCs play a significant role in male fertility and in the intergenerational transfer of genetic information. Male GSCs from livestock are unstable when cultured in vitro, as it is difficult to maintain the biological properties of self‐renewal in a stable culture system 1, 2. Previous studies with mouse mGSCs have achieved significant progress 3, providing more basic evidences about the pluripotency and reprogramming of livestock mGSCs.

Livestock have many valuable products including meat, wool and dairy products from cows and dairy goats. Biomedical interventions are becoming increasingly necessary as antibodies and drugs are obtained from livestock, with long reproductive cycles and low numbers of offspring resulting in a severe livestock situation 4, 5. The Guanzhong dairy goat is an important livestock animal in China, and studies on dairy goat mGSCs may improve the preservation and optimization of the germplasm resources 6. Stably culturing mGSCs in vitro is an important basic mechanism of research on self‐renewal and differentiation, which is especially important for adult stem cells for the production of transgenic animals and hereditary breeding 7.

Epigenetic modification, especially DNA methylation, plays a key role in the self‐renewal and differentiation of mGSCs 8. Tet (ten‐eleven translocation) protein 1 is a key enzyme responsible for active DNA demethylation, catalyzing the oxidation of 5mC to 5hmC, and many studies have elucidated the functions of Tet1 in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and brain tissue 9, 10. In developing primordial germ cells (PGCs), Tet1 is specifically required for the proper erasure of genomic imprints 11. Tet1 is expressed at high levels in carcinomas in situ, suggesting that germ cell cancers using the oxidative pathway to achieve active DNA demethylation 12. Lysine methylation functions in both the repression and activation of chromatin structure in a context‐specific manner. Lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3) exhibits a special role in the DNA demethylation mediated by Tet1 13. To date, while mGSCs have exhibited great pluripotency and an ability for self‐renewal and differentiation, it remains difficult to establish stable livestock mGSC cell lines and in vitro culture systems 14, 15. In our laboratory, we have successfully established an immortalized dairy goat mGSC cell line, enabling the long‐term study of dairy goat mGSCs in vitro 16. Maintaining pluripotency and reprogramming efficiency are expected to be the biggest obstacles to stable in vitro culture stem cells. Thus, we investigate the mGSC biology through Tet1 modification to explore the role of DNA demethylation and histone methylation dynamics in male germ cell specification and development.

Materials and methods

Plasmid reconstruction

The Tet‐On 3G Systems Vector pTRE3G‐BI (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) with the mTet1 gene fragment and GFP was constructed by first inserting mTet1 (pTRE3G‐BI‐mTet1) and then adding GFP (pTRE3G‐BI‐GFP‐mTet1). To reconstruct pTRE3G‐BI‐mTet1, this vector (pTRE3G‐BI) was digested with BamHI/NotI and ligated to a 6120 bp mTet1 fragment generated from Myc‐mTet1 (A gift from Dr Zekun Guo). Primers were designed using published sequences for the goat Tet1 gene (F: 5′‐GGATCCATGTCTCGGTCCCGCC‐3′, R: 5′‐AAGCGGCCGCTTAGAACCAACGATTGTAGGG‐3′). To reconstruct pTRE3G‐BI‐GFP‐mTet1, the pTRE3G‐BI‐mTet1 plasmid was digested with NdeI/MluI and ligated to a 722 bp GFP fragment generated from pEGFP‐C1. The following primers were used: (F: 5′‐CGACGCGTATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGA‐3′, R: 5′‐GGAATTCCATATGTTATCTAGATCCGGTGGATC‐3′).

Cell culture and DNA transfection

The male germline stem cell line (mGSC) used in this study was an immortalized dairy goat mGSC line mGSCs‐I‐SB 16. The cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), 0.1 mM ß‐mercaptoethanol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 2 mm glutamine (Invitrogen) at 38.5 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The J1 mouse embryonic stem cells were cultured as the conventional conditions 17.

To co‐transfect the Tet‐On 3G Systems Vector pTRE3G‐BI‐GFP‐mTet1 and pEF1α‐Tet3G, the two plasmids [pTRE3G‐BI‐GFP‐mTet1: pEF1α‐Tet3G=5:1 (m/m)] were incubated with opti‐MEM (GIBCO). 1 × 106 cells with the density of 75% were replaced with fresh DMEM/F12 consisted of the supplements for 30 min before cell transfection. 5 μg pTRE3G‐BI‐GFP‐mTet1 plasmid and 1 μg pEF1α‐Tet3G were co‐incubated and Tuberfect was used as a transfection reagent, which was added to the plasmids at a volume V = (m of plasmids/2), co‐incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and then added to the cells. At 12 h after transfection, the medium was discarded and replaced with fresh DMEM/F12 with supplements. At 24 h, cells were diluted in a 10‐cm dish containing fresh medium supplemented with G418 (600 μg/ml) and Dox to select for stably transfected cells. Individual cell colonies were isolated 8–12 days after dilution culture and expanded for further culture. Tet‐On systems were provided with a Dox concentrations far below cytotoxic levels for either cell culture or transgenic studies, while the reconstructed plasmid may require different Dox concentrations in cell induction, and different Dox concentrations (0, 0.10, 0.25, 0.50, 2.50 μg/ml) were presented to select optimal concentration for cell induction.

Immunofluorescence of 5hmC

The cell samples were directly fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 15 min and then 0.5% Triton X‐100 in PBS for 10 min, followed by incubation with RNase (50 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 1 h in the dark, 4 N HCl at 37 °C for 20 min, and then 100 mm Tris‐HCl at room temperature for 10 min. After three washes in PBS, samples were blocked in 4% goat serum at room temperature for 30 min and exposed to a primary antibody against 5hmC (1:500; Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 4 °C overnight. Then, after three 5 min washes in PBS, samples were incubated with Alexa 594 anti‐rabbit IgG antibody (1:500; Invitrogen) at room temperature for 30 min followed by three washes in PBS. The cell nuclei were stained using PI (Prodium Iodide). Images were captured using a Leica fluorescence microscope (Hicksville, NY, USA).

Immunofluorescence of histone methylation

The cells were directly fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 15 min and 0.5% Triton X‐100 in PBS for 10 min, blocked in 4% goat serum at room temperature for 30 min, and then exposed to primary antibody against H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 (1:200; Sino Biological Inc., Beijing, China) overnight at 4 °C. After three 5 min washes in PBS, samples were incubated with secondary Alexa 594 anti‐rabbit IgG antibody (1:500; Invitrogen) at room temperature for 30 min, followed by three washes in PBS. Cell nuclei were stained using DAPI. Images were captured using a Leica fluorescence microscope (Hicksville).

RT‐PCR and (Semi) quantitative RT‐PCR

Total RNA was extracted from mGSCs and mGSC‐mTet1 cells using TRIzol (Tiangen Biotech Co. Ltd, Beijing, China). Primers for mTet1, germ cell markers Gfra1 and Promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein (PLZF), the cell proliferation marker PCNA, the cell cycle protein CCND1, cell differentiation markers synaptonemal complex protein 3(Scp3), homeobox B1 (HoxB1), Tet1 associated gene SIN3 transcription regulator family member A (Sin3A), and goat endogenic Tet family genes (gTet1 and gTet3) were designed using the published goat gene sequences as listed in Table 1. Detailed qRT‐PCR and gel electrophoresis protocols can be found in previous studies 18. The expression levels of genes were analyzed by a quantitative reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (QRT‐PCR) as described previously 19.

Table 1.

The quantitative Real‐time PCR primers

| Gene | Strand | Sequence | Length of PCR Fragment (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gapdh | F | CCACGCCATCACTGCCACCC | 116 |

| R | CAGCCTTGGCAGCGCCAGTA | ||

| Gfra1 | F | GGACAGGCAGCAGGAAATA | 200 |

| R | GTCTCCTGTCCCAGTCAAA | ||

| PLZF | F | CACCGCAACAGCCAGCACTAT | 127 |

| R | CAGCGTACAGCAGGTCATCCAG | ||

| PCNA | F | AGTGGAGAACTTGGAAATGGAA | 167 |

| R | GAGACAGTGGAGTGGCTTTTGT | ||

| CCND1 | F | TGAACTACCTGGACCGCT | 212 |

| R | CAGGTTCCACTTGAGYTTGT | ||

| Scp3 | F | GTATGGAGGACTTGGAGA | 138 |

| R | GAGACTTTCGGACACTTGC | ||

| Sin3A | F | GAGGCTGCTTCGGATTTGT | 105 |

| R | GCTGTCACTCTTGTCTCGCTTA | ||

| HoxB1 | F | CCTTCGCACCAACTTCACCA | 165 |

| R | CTCCCGCTTCTTCTGCTTCAT | ||

| mTet1 | F | GAGCCTGTTCCTCGATGTGG | 202 |

| R | CAAACCCACCTGAGGCTGTT | ||

| gTet1 | F | AAGGGAAGGAATGGAAGCCAAGATC | 108 |

| R | CCAGAACGAGGAATGGGTTGAGTAA | ||

| gTet3 | F | ACCCATCCTTTGCTCCTGACG | 205 |

| R | TCGGGCCGCTTGAATACTG |

Western blot assay

Proteins were extracted from stably transfected cells and then the protein concentration was detected using the BCA Protein Quantification Kit (Vazyme, Piscataway, NJ, USA). After heat denaturation in 5% SDS–PAGE sample loading buffer, the protein samples were resolved by SDS‐PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The samples were probed with β‐actin (1:1000; Sino Biological Inc.), and antibodies against Tet1 (1:1000; GeneTex Inc., USA), H3K9me2, H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 (1:1000; Sino Biological Inc.) as previously described 18. The secondary antibody was horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated anti‐rabbit IgG (1:1,000, Bioworld, Nanjing, China). The detection was performed using Thermo Scientific Pierce ECL western blotting substrate, and the results were analyzed using a Tanon‐410 automatic gel imaging system.

Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) Assay

For the FACS‐mediated cell cycle assay, the cells were digested by trypsin and washed in PBS at room temperature. After centrifugation, the PBS was discarded and 1 ml cold staining buffer was added. Cells were resuspended, and then 10 μl PI solution was added and incubated with the cells for 15 min in the dark. FACS was performed on an EPICS ELITE apparatus (Beckmann–Coulter) with MultiCycle software (Phoenix Flow Systems, Inc.) 20.

5‐Bromo‐2‐DeoxyUridine (BrdU) assay

The cells were treated with BrdU (30 μg/ml, Sigma) for 1 h and then subjected to BrdU immunostaining. Cells were fixed with methanol/acetone [3:1 (v/v)] for 15 min at room temperature followed by three washes in PBS, and then incubated in 0.5% Triton X‐100 for 10 min, followed by three washes in PBS at room temperature. Mouse anti‐BrdU (1:300; Santa Cruz, Inc., California, USA) dissolved in 0.1 m PBS (pH 7.4) containing 4% normal goat serum was added, and the cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C. After three washes in PBS, cells were incubated with Alexa 594 anti‐rabbit IgG antibody (1:500, Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature. After three washes, cells were visualized under fluorescence microscopy.

Cell Counting Kit (CCK8) assay

To detect the cell proliferation, cell suspensions were inoculated in 96‐well plates (100 μl/well) and cultured at 38.5 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Then, using the Cell Counting Kit (CCK8), 10 μl CCK Solution was added to the wells and the cells were incubated for 2.5 h in the incubator. The Multi‐Volume Spectrophotometer System (BioTek Epoch, Vermont, USA) was used to measure the absorbance at 450 nm. The results were calculated as [OD value of Dox − OD value of blank]/[OD value of (Dox‐) − OD value of blank] %. All data were collected from 3 independent experiments.

Statistical analysis

The relative GFP intensity of Dox‐induced cells and the results of the BrdU, qRT‐PCR and western assays were statistically analyzed using a two‐tailed t‐test analysis (Excel, Microsoft 2007). The results of the CCK8 assay were statistically analyzed using one‐way ANOVA with Tukey's test. All data were collected from 3 independent experiments.

Results

Generation and identification of transgenic cells using pTRE3G‐BI‐GFP‐mTet1 and pEF1α‐Tet3G

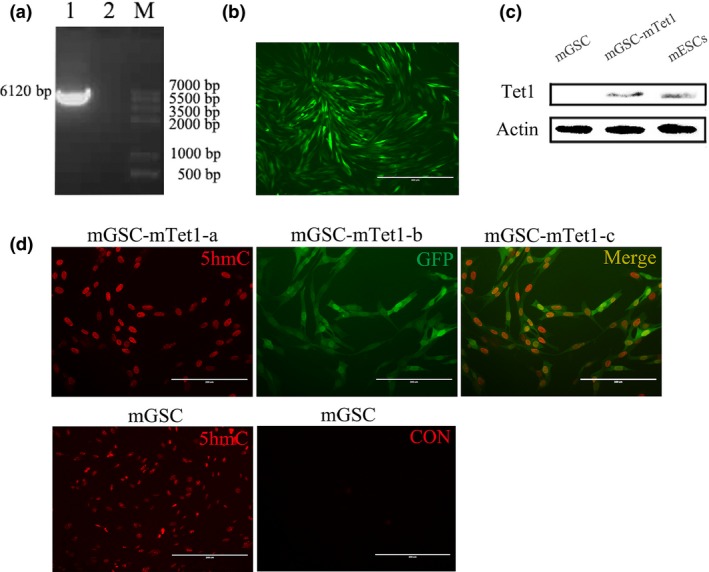

The mouse Tet1 (mTet1) (Fig. 1a) was transfected into mGSC‐I‐SB cells by the plasmids pTRE3G‐BI‐GFP‐mTet1 and pEF1α‐Tet3G (Fig. S1). The plasmid pTRE3G‐BI‐GFP‐mTet1 (Fig. S1) was constructed by supplementing pTRE3G‐BI with GFP from pEGFP‐C1, and mTet1 from Myc‐mTet1. The fluorescence reporter was constructed to monitor mTet1 expression in living cells. The positive cell colonies were screened with G418 and 600 μg/ml Dox, and mTet1 positive cell colonies were identified by GFP expression (Fig. 1b). Western Blot showed that the mTet1 was expressed in mTet1 positive mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs), with high Tet1 expression levels observed in mESCs 21, but no detected in mGSCs (Fig. 1c). As the hydroxyl product of Tet1, 5hmC was increased to a higher level in mTet1 positive cells (mGSC‐mTet1 cells) than in mGSCs (Fig. 1d). Moreover, the nuclei of mGSC‐mTet1 cells were larger than those of mGSCs, which may be a morphological response to Tet1 modification of mGSCs.

Figure 1.

The construction of pTRE 3G‐ BI ‐ GFP ‐ mT et1 and mT et1 positive mGSC screening and identification. (a) The PCR production of mTet1 (1. mTet1 gene fragment, 2. H2O, M. Marker). (b) The mGSCs were transfected with pTRE3G‐BI‐GFP‐mTet1 and screened positive clonal cells (mGSC‐mTet1). (c) Western blot analysis of mTet1 in mGSCs, positive clonal cells and mESCs (positive control). (d) Immunofluorescence staining of 5hmC in mGSCs and mGSC‐mTet1 cells, CON was for negative control of immunofluorescence staining. Bar = 200 μm.

The identification of the optimal Dox concentration to screen mGSC‐mTet1

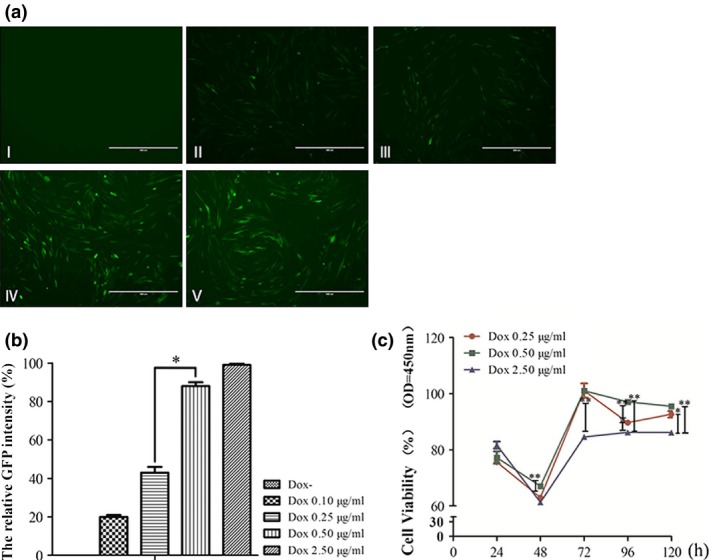

The plasmid pTRE3G‐BI‐GFP‐mTet1 exhibits inducible mTet1 expression under the control of a TRE3G promoter (PTRE3G) when cultured in the presence of Dox. As low Dox concentrations may lead to the induction of Tet‐On systems and high Dox concentrations may lead to cytotoxicity to cells, it is important to identify the optimal Dox concentration. The stably transfected mGSC‐mTet1 cells were cultured with different Dox concentrations (0, 0.10, 0.25, 0.50, 2.50 μg/ml). Stronger fluorescent signals were detected with higher Dox concentrations (Fig. 2a), reaching the maximum at 0.5 μg/ml, without significant increase from 0.5 to 2.50 μg/ml, suggesting an extreme level of mTet1 induction (Fig. 2a). Dox affected the cell viability, with lower viability observed when the cells were cultured for 48 h because of the logarithmic phase of mGSCs. Higher Dox concentrations may lead to cytotoxicity, with the cells cultured at 2.50 μg/ml Dox exhibiting more cell death (Fig. 2A‐V), and a lower rate of cell proliferation compared with lower Dox concentrations (Fig. 2c). The CCK8 assay revealed that 0.50 μg/ml is the optimal Dox concentration for mTet1 expression in dairy goat mGSCs.

Figure 2.

Identification of the optimal Dox concentration to screen mGSC ‐ mT et1 cells. (a) mGSC‐mTet1 cells cultured at different Dox concentrations (I‐V indicate cells with Dox concentrations of 0, 0.10, 0.25, 0.50, 2.50 μg/ml), Bar = 200 μm. (b) The relative fluorescence intensity of GFP in mGSC‐mTet1 cells with different Dox concentrations. The strongest fluorescence intensity was considered to be 100% (Dox concentration of 2.50 μg/ml), and other results were compared with this intensity to obtain relative fluorescence intensity. Three repeats were performed for each sample, and data were analyzed by a two‐tailed t‐test analysis was used, *P < 0.05. (c) The cell activity assay of mGSC‐mTet1 cells with different Dox concentrations using the CCK8 Kit. Cells treated with different Dox concentrations were detected 5 times every 24 h. Data were analyzed using an ANOVA followed by Tukey's test, with 3 repeats performed for each condition, ***P < 0.001,**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

Cell proliferation and gene expression in Tet1‐modified mGSCs

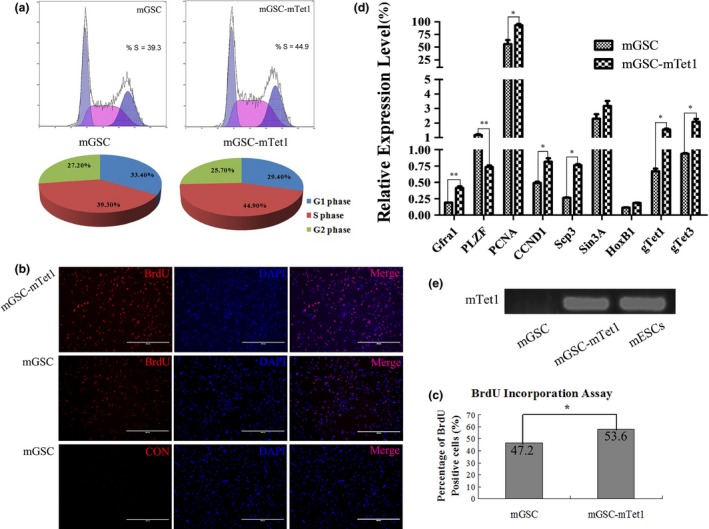

To detect whether Tet1 functions in cell proliferation and self‐renewal, FACS and qRT‐PCR were performed, using the primers in Table 1. The stably transfected mGSC‐mTet1 cells with an optimal Dox concentration (0.5 μg/ml) and mGSCs were cultured under the same conditions, and their cell cycles were analyzed by FACS. The FACS assay showed that 39.3% of mGSCs were in the S phase, as were 44.9% of mGSC‐mTet1 cells (Fig. 3a). The BrdU assay found a higher rate of BrdU positive mGSC‐mTet1 cells (53.6%) than in mGSCs (47.2%) and stronger red fluorescence intensity in positive mGSC‐mTet1 cells (Fig. 3b), differences of cell number and proliferation activity were observed between mGSCs and mGSC‐mTet1 cells (Fig. 3c), suggesting a stronger ability to proliferate under mTet1 overexpression. QRT‐PCR analysis showed a higher Gfra1 expression, suggesting a strengthening of male germline cell characteristics. However, PLZF was down‐regulated in mGSC‐mTet1s. The proliferation marker (PCNA) and cell cycle protein (CCND1) were up‐regulated in mGSC‐mTet1 cells compared with mGSCs, providing further evidences that Tet1 overexpression promotes mGSC proliferation. Stably transfected mGSC‐mTet1 cells at an optimal Dox concentration (0.5 μg/ml) exhibited higher mTet1 RNA expression levels (Fig. 3d), and the up‐regulation of gTet1 and gTet3 in mGSC‐mTet1 cells. In our study, the expression of Scp3 was significantly up‐regulated in mGSC‐mTet1 cells. We hypothesize that Tet1 affects the meiosis progress, as HoxB1 was not found to be significantly different in mGSC‐mTet1 and mGSC cells. In addition, the authenticated target of Tet1, Sin3A, exhibited no significant changes between mGSC‐mTet1 and mGSC cells 22. These results show the effects of species and cell differences on Tet1 function (Fig. 3d). These results demonstrate that Tet1 plays an important role in the regulation of gene expression and cell proliferation. The gene mTet1 was expressed at an extremely high level in stably transfected mGSC‐mTet1 cells compared to the SSC marker genes such as Gfra1. Semi quantitative RT‐PCR detected mTet1 expression in stably transfected mGSC‐mTet1 and mESCs, while no detection in mGSCs (Fig. 3e, Table 1).

Figure 3.

The cell proliferation assay and gene expression of mGSC s and mGSC ‐ mT et1 cells. (a) The FACS assay analyzes the S phase dynamics of mGSCs and mGSC‐mTet1 cells. (b) BrdU assay in mGSCs and mGSC‐mTet1 cells, CON was for negative control of immunofluorescence staining. Bar = 400 μm. (c) The statistical analysis of the BrdU positive rate in mGSCs and mGSC‐mTet1 cells. Data were analyzed using a two‐tailed t‐test analysis, with three repeats performed or each sample, *P < 0.05. (d) Gene expression (Gfra1, PLZF, PCNA, CCND1, Scp3, Sin3A, HoxB1, gTet1 and gTet3) of mGSCs and mGSC‐mTet1 analyzed by QRT‐PCR. Data from three repeats per sample were analyzed using a two‐tailed t‐test analysis with three repeats for each sample, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. (e) Semi QRT‐PCR of mTet1 in mGSCs, positive clonal cells and mESCs (positive control).

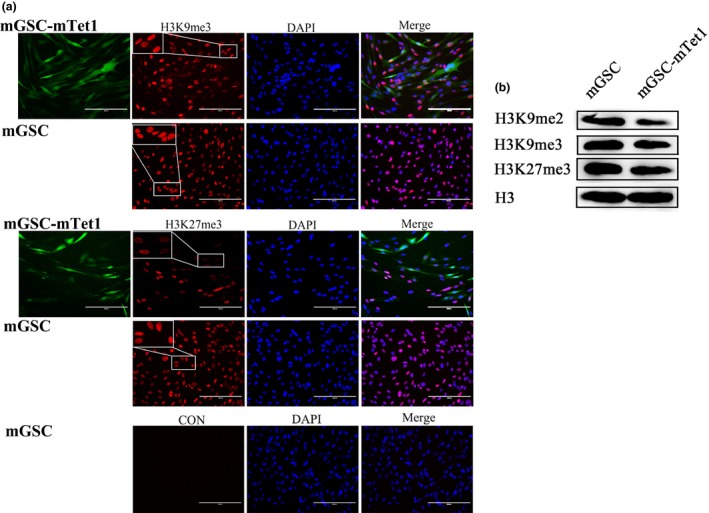

The histone methylation dynamics in mGSCs and mGSC‐mTet1 cells

To identify the histone methylation states of mGSCs and mGSC‐mTet1, antibodies specific to H3K9me2, H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 were used to explore methylation state in stably transfected mGSC‐mTet1 cells culture with the optimal Dox concentration (0.5 μg/ml) and mGSCs. It was interesting that the methylation level of H3K9me2, H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 in mGSC‐mTet1 and mGSCs changed (Fig. 4b), and the methylation location of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 also changed dynamically, while no obvious changes were detected in the H3K9me2 distribution (Fig. 4a). The H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 levels were significantly and uniformly distri‐buted in the nuclei of mGSC‐mTet1 cells, while punctate fluorescence with numerous foci was observed in mGSCs. The H3K27me3 level was significantly decreased and located in the perinuclear area in mGSC‐mTet1s, with staining absent or weak staining distributed in the center of the nucleus. In contrast, H3K27me3 was uniformly distributed throughout the nucleus of mGSCs. This suggests that Tet1 plays a critical role in the histone methylation dynamics in goat mGSCs.

Figure 4.

The histone methylation dynamics in mGSC s and mGSC ‐ mT et1 cells. (a) Immunofluorescence staining of tri‐methyl H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3) and tri‐methyl H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3) in mGSCs and mGSC‐mTet1 cells, CON was for negative control of immunofluorescence staining. Bar = 200 μm. (b) Western blot analysis of Dimethyl histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me2), tri‐methyl H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3) and tri‐methyl H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3) in mGSCs and mGSC‐mTet1 cells.

Discussion

Stem cells are defined as cells with the characteristics of self‐renewal and differentiation 21, with embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and adult stem cells (ASCs) representing attractive resources for biomedical applications 23, 24. The significant achievements of livestock ESCs, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) promoted the applications in regenerative medicine and the area of livestock science 5. However, the in vitro study of livestock mGSCs is difficult due to the lack of a stable mGSC line and little information on the mechanisms on mGSCs, even though mouse mGSC lines have been obtained 25. Optimization the culture condition such as modifying the medium by supplementing some stem cell factors, and using extracellular matrix for the establishment of SSC cell line is still an unsolved issue for domestic animals. The fact that germline stem cells do not maintain their undifferentiated stage in culture might be due many reasons including the niche incompatibility of the in vitro system as compared to the testis; Cell‐cell interactions between the germ cells and testicular somatic cells; Peptide hormones and growth factors provided by the supporting cells may all have influence in determination of the fate of the self‐renewal or differentiation of the germline stem cells. Changing the methylation dynamics of the mGSCs to make a stable cell line to be used for generation of transgenic livestock does seem to be a practical method.

Male GSCs can be induced to differentiate into spermatogenic cells 14. Immortalized dairy goat mGSCs have been produced in our lab 17, and while this cell line is expected to better maintain the ability to self‐renew, many factors determine this progress, especially the epigenetic modification of reprogramming. DNA methylation and histone methylation are the two main forms of epigenetic modification, playing critical roles in spermatogenesis through the regulation of their differentiation. Tet1 functions in stem cell maintenance and in keeping the balance between pluripotency and lineage commitment by initiating the hydroxylation process, leading to cytosine demethylation 26. Our previous study described the expression patterns of Tet1, H3K9 and H3K27 in dairy goat testis and cultured goat spermatogonia stem cells (gSSCs) 18. In this study, mouse Tet1 was transfected into the immortalized male germ cells using the Tet‐On 3G system, and the exogenetic Tet1 can stimulate and promote endogenic dairy goat Tet1 expression. Tet1 protein was stably expressed in mGSC‐mTet1 cells, and increasing 5hmC levels also led to the hydroxylation of Tet1. The nuclei of mGSC‐mTet1 cells were bigger than those of mGSCs, suggesting that demethylation may lead to chromosome loss and improved gene transcription.

Although the Tet‐On 3G System provides a recommended Dox concentration, we analyzed cell proliferation over a range of Dox concentrations. The results showed that in the absence of Dox, mGSC‐mTet1 cells exhibited higher cell proliferation in the CCK8 assay compared to cells cultured in the presence of Dox, indicating that Dox induction led to cytotoxicity. In addition, as the reconstructed vector with its large gene fragments may affect gene expression, it is important to determine the optimal Dox concentration. Our results suggest that 0.5 μg/ml was the optimal induction concentration to minimize cytotoxicity and ensure optimal growth in vitro.

Higher rates of S phase and BrdU positive cells in mGSC‐mTet1 cells compared with mGSCs suggest stronger proliferation ability with mTet1 overexpression. QRT‐PCR analysis evidenced that Tet1 overexpression in mGSC‐mTet1 cells induced up‐regulation of the SSC marker Gfra1, which it has been shown to sustain mGSC characteristics 33. PCNA has been proven to directly interact with Tet1, and the recruitment of Tet1 through Tet1/PCNA complexes is the basis for the regulation of epigenetic enzymes 22. In our study, Tet1 overexpression in mGSC‐mTet1 cells was associated with up‐regulation of PCNA along with CCND1, confirming that Tet1 affects the proliferation ability of mGSCs. However, the upregulation of Scp3 was unexpected, which may be the composite results of strengthen of mGSC stability and significantly enhanced proliferation activity. A surprising and confusing finding from our results is the down‐regulation of PLZF in mGSC‐mTet1 cells. PLZF is essential for SSC maintenance 27, 28. PLZF is associated with H3K9me3 and diffuse chromatin, and which plays roles in the regulation of self‐renewal and differentiation of SSC by indirectly regulating metabolic enzymes and cell cycle regulatory proteins. This may be the reason for the down‐regulation of PLZF in mGSC‐mTet1 cells, as Tet1 plays a critical role in demethylation through complex pathways and PLZF interacts indirectly with genes, as no PLZF binding sites are present in the gene promoters 28, 29. A previous study that showed Tet protein can interact with pathways such as polycomb and glycosylation pathways 26. H3K27me3 is enriched in genes related to the development and differentiation of PGCs 30. EZH2 is H3K27me3 methylase that has been proven to interact directly with Tet1, and EZH2 leads to the up‐regulation of H3K27me3 in cancers through the MEK‐ERK pathway 26. In our study, the location and changes in amounts of H3K9me2, H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 led to the loss of histone methylation and position transfer in mGSC‐mTet1 cells, which may also work through the p53 pathway by DNA‐PK through base excision repair 31. Tet1 was expected to be the main oxygenase involved in oxidation turnover from 5mC to 5hmC 32. Tet1 expression increases with cell density in malignant germ cells, and de novo methylation was essential to key genes for PGC fate 12. Our results first demonstrated that mGSCs overexpressing mTet1 promoted their proliferation through their histone modifications, including H3K9me3 and H3K27me3, while further exploration is required to determine the function and physiological meaning of Tet1 mediated by mGSCs.

Taken together, our results on Tet1 modification provide a new model for DNA methylation/demethylation and better regulation of epigenetic modifications in mammalian mGSCs. Tet1 plays an important role in epigenetic modification through DNA demethylation. In our study, overexpression of Tet1 up‐regulated germ cell‐specific genes and promoted cell proliferation in mGSCs, altering the histone methylation dynamics of H3K9 and H3K27 to make mGSCs in vitro more stable. This approach may provide new solutions for the establishment of mGSC cell lines.

Conclusion

Tet1 plays important role in epigenetic modification through DNA demethylation. In our study, overexpression of Tet1 up‐regulated germ cell‐specific genes and promoted cell proliferation in mGSCs, meanwhile the Histone methylation dynamic of H3K9 and H3K27, which make mGSCs in vitro more stable, and it may provide new solutions for mGSC lines establishment.

Funding

This study was done with the support of grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (31272518, 31572399), the National Major Project for Production of Transgenic Breeding (2014ZX08007‐002), National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (SS2014AA021605), Open Subjects for the Major Basic Researches of Science and Technology Office of Inner Mongolia (20130902). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Maps of Tet‐On 3G Systems (a and b), pTRE3G‐BI (a) and the recombinant plasmid pTRE3G‐BI‐GFP‐mTet1 (c).

References

- 1. Saito M, Handa K, Kiyono T, Hattori S, Yokoi T, Tsubakimoto T et al (2005) Immortalization of cementoblast progenitor cells with Bmi‐1 and TERT. J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feng L‐X, Chen Y, Dettin L, Pera RAR, Herr JC, Goldberg E et al (2002) Generation and in vitro differentiation of a spermatogonial cell line. Science 297, 392–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL (2004) Culture conditions and single growth factors affect fate determination of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Biol. Reprod. 71, 722–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Redwan E‐RM (2009) Animal‐derived pharmaceutical proteins. J. Immunoassay Immunochem. 30, 262–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Flint A, Woolliams J (2008) Precision animal breeding. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363, 573–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhu H, Liu C, Li M, Sun J, Song W, Hua J (2013) Optimization of the conditions of isolation and culture of dairy goat male germline stem cells (mGSC). Anim. Reprod. Sci. 137, 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shi W, Shi T, Chen Z, Lin J, Jia X, Wang J et al (2010) Generation of sp3111 transgenic RNAi mice via permanent integration of small hairpin RNAs in repopulating spermatogonial cells in vivo. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 42, 116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gan H, Wen L, Liao S, Lin X, Ma T, Liu J et al (2013) Dynamics of 5‐hydroxymethylcytosine during mouse spermatogenesis. Nat. Commun. 4, 1995. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stroud H, Feng S, Morey Kinney S, Pradhan S, Jacobsen SE (2011) 5‐Hydroxymethylcytosine is associated with enhancers and gene bodies in human embryonic stem cells. Genome Biol. 12, R54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jin S‐G, Wu X, Li AX, Pfeifer GP (2011) Genomic mapping of 5‐hydroxymethylcytosine in the human brain. Nucleic Acids Res. 39(12), 5015–5024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dawlaty MM, Breiling A, Le T, Raddatz G, Barrasa MI, Cheng AW et al (2013) Combined deficiency of Tet1 and Tet2 causes epigenetic abnormalities but is compatible with postnatal development. Dev. Cell 24, 310–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nettersheim D, Heukamp LC, Fronhoffs F, Grewe MJ, Haas N, Waha A et al (2013) Analysis of TET expression/activity and 5mC oxidation during normal and malignant germ cell development. PLoS ONE 8, e82881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Williams K, Christensen J, Pedersen MT, Johansen JV, Cloos PA, Rappsilber J et al (2011) TET1 and hydroxymethylcytosine in transcription and DNA methylation fidelity. Nature 473, 343–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hua J, Zhu H, Pan S, Liu C, Sun J, Ma X et al (2011) Pluripotent male germline stem cells from goat fetal testis and their survival in mouse testis. Cell. Reprogram. 13, 133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McMillan M, Andronicos N, Davey R, Stockwell S, Hinch G, Schmoelzl S (2013) Claudin‐8 expression in Sertoli cells and putative spermatogonial stem cells in the bovine testis. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 26, 633–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhu H, Ma J, Du R, Zheng L, Wu J, Song W et al (2014) Characterization of immortalized dairy goat male germline stem cells (mGSCs). J. Cell. Biochem. 115, 1549–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peng S, Hua J, Cao X, Wang H (2011) Gelatin induces trophectoderm differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Biol. Int. 35, 587–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zheng L, Zhu H, Tang F, Mu H, Li N, Wu J et al (2015) The Tet1and histone methylation expression patternin dairy goat testis. Theriogenology 83, 1154–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhu H, Liu C, Sun J, Li M, Hua J (2012) Effect of GSK‐3 inhibitor on the proliferation of multipotent male germ line stem cells (mGSCs) derived from goat testis. Theriogenology 77, 1939–1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li M, Liu C, Zhu H, Sun J, Yu M, Niu Z et al (2013) Expression pattern of Boule in dairy goat testis and its function in promoting the meiosis in male germline stem cells (mGSCs). J. Cell. Biochem. 114, 294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Durcova‐Hills G, Wianny F, Merriman J, Zernicka‐Goetz M, McLaren A (2003) Developmental fate of embryonic germ cells (EGCs), in vivo and in vitro. Differentiation 71, 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cartron P‐F, Nadaradjane A, LePape F, Lalier L, Gardie B, Vallette FM (2013) Identification of TET1 partners that control its DNA‐demethylating function. Genes Cancer 4(5–6), 235–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mizuno H, Tobita M, Uysal AC (2012) Concise review: adipose‐derived stem cells as a novel tool for future regenerative medicine. Stem Cells 30, 804–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Young HE, Black AC Jr (2004) Adult Stem Cells. Anat. Rec. A: Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol. 276, 75–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Olive V, Cuzin F (2005) The spermatogonial stem cell: from basic knowledge to transgenic technology. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 37, 246–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fu H‐L, Ma Y, Lu L‐G, Hou P, Li B‐J, Jin W‐L et al (2014) TET1 exerts its tumor suppressor function by interacting with p53‐EZH2 pathway in gastric cancer. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 10, 1217–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Buaas FW, Kirsh AL, Sharma M, McLean DJ, Morris JL, Griswold MD et al (2004) Plzf is required in adult male germ cells for stem cell self‐renewal. Nat. Genet. 36, 647–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Costoya JA, Hobbs RM, Barna M, Cattoretti G, Manova K, Sukhwani M et al (2004) Essential role of Plzf in maintenance of spermatogonial stem cells. Nat. Genet. 36, 653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dadoune J (2007) New insights into male gametogenesis: what about the spermatogonial stem cell niche? Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 45, 141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ng J‐H, Kumar V, Muratani M, Kraus P, Yeo J‐C, Yaw L‐P et al (2013) In vivo epigenomic profiling of germ cells reveals germ cell molecular signatures. Dev. Cell 24, 324–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Parlanti E, Locatelli G, Maga G, Dogliotti E (2007) Human base excision repair complex is physically associated to DNA replication and cell cycle regulatory proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 1569–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tan L, Shi YG (2012) Tet family proteins and 5‐hydroxymethylcytosine in development and disease. Development 139, 1895–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. He Z, Jiang J, Hofmann MC, Dym M (2007) Gfra1 silencing in mouse spermatogonial stem cells results in their differentiation via the inactivation of RET tyrosine kinase. Biol. Reprod. 77, 723–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Maps of Tet‐On 3G Systems (a and b), pTRE3G‐BI (a) and the recombinant plasmid pTRE3G‐BI‐GFP‐mTet1 (c).