Abstract

Abstract. Objectives: Adipose tissue is the most abundant and accessible source of adult stem cells. Human processed lipoaspirate contains pre‐adipocytes that possess one of the a characteristic pathways of multipotent adult stem cells and are able to differentiate in vitro into mesenchymal and also neurogenic lineages. Because stem cells have great potential for use in tissue repair and regeneration, it would be significant to be able to obtain large amounts of these cells in vitro. As demonstrated previously, purine nucleosides and nucleotides mixtures can act as mitogens for several cell types. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of polydeoxyribonucleotides (PDRN), at appropriate concentrations, on human pre‐adipocytes grown in a controlled medium, also using different passages, so as to investigate the relationship between the effect of this compound and cellular senescence, which is the phenomenon when normal diploid cells lose the ability to divide further. Materials and methods: Human pre‐adipocytes were obtained by liposuction. Cells from different culture passages (P6 and P16) were treated with PDRN at different experimental times. Cell number was evaluated for each sample by direct counting after trypan blue treatment. DNA assay and the 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide test were also carried out in all cases. Results and Conclusions: PDRN seemed to promote proliferation of human pre‐adipocytes at both passages, but cell population growth increased in pre‐adipocyte at P16, after 9 days as compared to control. Our data suggest that PDRN could act as a pre‐adipocyte growth stimulator.

INTRODUCTION

Several researchers have shed new light on the importance of the action of extracellular nucleotides and nucleosides to increase cell proliferation and activity. Purine nucleosides and nucleotides in particular, bind to specific receptors triggering different signal transduction pathways. They act as mitogens for fibroblasts, endothelial cells and other cell types (Rathbone et al. 1992; Muratore et al. 1997; Thellung et al. 1999) and work synergistically with different growth factors (epidermal growth factor, platelet‐derived growth factor, fibroblast growth actor) (Dingji et al. 1990; , Chavan et al. 1994). Furthermore, polydeoxyribonucleotides (PDRN) are commonly used by plastic surgeons in pre‐surgical cutaneous treatments, as they stimulate fibroblast metabolism, promoting both an increase in the number of fibroblasts and dermal matrix component production (Bigliardi 1982). Recently, the effect of PDRN has been analysed in a number of tissues, such as human corneal epithelium (Lazzarotto et al. 2004) and both rat and human bone (Bowler et al. 2001; Guizzardi et al. 2007), showing enhancement of tissue regeneration in all cases. In addition, PDRN leads to improvement in angiogenesis in burn wound treatment (Bitto et al. 2006) and activates the salvage pathway of nucleic acids to provide available nucleosides and nucleotides (Guizzardi et al. 2003). PDRNs are also able to influence immunological responses (Edgington 1992; Gailit & Clark 1994) and production of different cytokines and growth factors (Musk et al. 1989; Edgington 1992). They have offered a protective and regenerative effect on ultraviolet‐irradiated mouse cell cultures (Henning et al. 1996) and also on human ultraviolet B‐exposed dermal fibroblasts (Belletti et al. 2007).

Human stem cells represent an important starting point for carrying out medical and biological clinical studies, as they have a large potential for use in tissue repair and regeneration. Adipose tissue contains mesenchymal‐like multipotent stem cells, pre‐adipocytes, that can be maintained for long periods of time with low levels of senescence (Zu et al. 2002), and these possess multilineage potential in vitro (Gimble & Guilak 2003; Raposio et al. 2007) in the presence of lineage‐specific induction factors. Our team is able to take a large volume of tissue from conventional liposuction procedures of healthy donors (standard procedures, low cell morbidity and minimal patient discomfort). Pre‐adipocytes possess many characteristics that are present in bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells, such as cell surface marker expression of CD105, CD90, CD71 and CD44 (De Ugarte et al. 2003). Similarly, they do not express the haematopoietic and endothelial markers, CD14, CD45 and CD31 (Gronthos et al. 2001; Astori et al. 2007). It is of great importance to be able to increase multipotent pre‐adipocyte number in vitro to obtain a greater proportion of these cells. Thus, this review is a first simple step to verify and investigate the behaviour and characteristics of human pre‐adipocytes at different passages in vitro, when treated with PDRN. Our choice to use pre‐adipocytes is of interest as these cells are considered to be a new source for adult multipotent stem cell populations (Strem et al. 2005) and their final characterization is still in progress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Polydeoxyribonucleotide is product of Officina Bio‐Farmaceutica Mastelli s.r.l. (Sanremo, Italy). The commercial preparation (Placentex Integro) contains 5625 mg of PDRN in a 3‐mL ampoule sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min. PDRN is a pure substance with a titre superior to 95%, constituted of different lengths of PDRN (from 50 to 2000 base pairs) obtained from sperm of salmon trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) for human alimentation, through an original purification and sterilization process. The other chemical reagents, unless otherwise specified, were from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All cell culture products, unless otherwise specified, were from Euroclone, Life Sciences Division (Pero, Italy).

Processed lipoaspirate cell processing and cell culture

Human adipose tissue was obtained from healthy donors during liposuction procedures under local anaesthesia. All procedures were approved by the Human Subject Protection Committee (Protocol HSPC 98‐08‐011‐01) of Italy. Lipoaspirate samples were processed as previously described by Zuk et al. (2001) to obtain pre‐adipocytes. Briefly, samples were repeatedly washed in Dulbecco's phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), to remove blood cells and anaesthetic. The extracellular matrix was digested with 2 mg/mL type I collagenase solution for 1 h at 37 °C, then was centrifuged to obtain the pellet which contains the stromal vascular components, including adipocyte progenitor cells, in addition to haematopoietic lineage cells. The pellet was then incubated with 160 mm ammonium chloride for 10 min, to lyse contaminating erythrocytes. The resulting cells were re‐suspended in cell culture control medium [Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/Ham's F‐12 1 : 1, 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mm glutamine, penicillin (100 UI/mL), streptomycin (50 µg/mL), amphotericin B (2.5 µg/mL)], filtered through a 100‐µm nylon mesh to remove cellular debris, and was incubated overnight at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After 24 h, cells were extensively washed in PBS and were maintained in control medium. Once arriving 80% confluence (after about 10 days culture), the cells were usually detached using trypsin 0.05%–sodium EDTA 0.02% solution and then were seeded in sterile flasks at a density of 2 × 104 per cm2. The culture medium was generally replaced with fresh medium three times a week. Cells were observed microscopically, daily (Nikon Eclipse TS100; Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Vitality evaluation

Vitality of the pre‐adipocytes was analysed when the cells were at the 6th and 16th passages in vitro. Then, they were treated for 24, 48 and 72 h with 100 µg/mL and 80 µg/mL PDRN. The number of cells was evaluated for each sample by detaching with trypsin 0.05%–sodium EDTA 0.02% solution and counting using a Neubauer chamber and trypan blue solution. Pre‐adipocytes were then plated in 96 multiwells (Corning Co., Corning, NY, USA), at a density of 5000 per well, in DMEM/Ham's F‐12 (1 : 1) supplemented with 10% FBS. Forty‐eight hours after seeding, cells were treated with PDRN (100–80 µg/mL) for the whole experimental time: 24, 48 and 72 h. At the end, cell viability was evaluated in both treated and untreated cultures by the 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) test as described by Mosmann (1983). Briefly, pre‐adipocytes were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C with 500 µg/mL MTT in serum‐free medium. In viable cells, mitochondria reduce MTT to formazane that accumulates as blue crystals. These were dissolved by adding a solution of 1 N hydrogen chloride–isopropanol (1 : 24 v/v). Then, the plates were left at room temperature for 10 min, after which the absorbance of the product was measured spectrophotometrically at 570 nm.

MTT proliferation assay

Pre‐adipocytes at the 6th and 16th passages in vitro were plated in 6 multiwells (Corning Co.) at a density of 10 000 per well, in DMEM/Ham's F‐12 (1 : 1) supplemented with 10% FBS. Forty‐eight hours after the seeding, cells were treated with PDRN (80 µg/mL) for 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 days. During these steps, growth medium was changed every 2 days. After each experimental culture condition, cell proliferation was evaluated in treated and untreated cultures by MTT test, as described above.

DNA assay

Pre‐adipocytes at the 6th and 16th passages in vitro were plated in 12 multiwells (Corning Co.), at a density of 5000 per well, in DMEM/Ham's F‐12 (1 : 1) supplemented with 10% FBS. Twenty‐four hours after seeding, cells were treated with PDRN (80 µg/mL) for 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 days. In this period, growth medium was changed every 2 days. After each experimental culture condition, cell proliferation was evaluated in treated and untreated cultures by DNA assay. Cell proliferation index was observed as cellular DNA content, measured by the method of Rao & Otto (1992). At pre‐determined time points, the experimental medium was removed; after washing with warm PBS, 1 mL of lysis solution [urea 10 m, 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate in saline sodium citrate buffer (SSC) 0.154 m NaCl, 0.015 m Na3 citrate, pH 7] was added to each well. Dissolved cell suspensions were incubated at 37 °C in a shaking bath for 2 h, then 1 mL of Hoechst 33258 dye 1 µg/µL in SSC buffer was added in the dark. Absorbance was measured with an LS5 PerkinElmer spectrofluorometer (Norwalk, CT, USA) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 355 nm and 460 nm, respectively. Cell proliferation was estimated by referring fluorescence units to a linear standard curve for DNA fluorescence versus cell number.

Senescence‐associated β‐galactosidase assay

Pre‐adipocytes at the 6th and 16th passages in vitro underwent β‐galactosidase (β‐gal) staining. In this assay, β‐gal activity tallies with senescent cells at pH 6.0 (Dimri et al. 1995; Gary & Kindell 2005). When cells were subconfluent (1 × 106 cells per flasks), monolayers were repeatedly washed with PBS, fixed in 2% formaldehyde/0.2% glutaraldehyde for 3–5 min at room temperature and washed twice in PBS. Then, cells were incubated at 37 °C (without CO2) with the senescence‐associated β‐gal staining solution: 1 mg of 5‐bromo‐4‐chloro‐3‐indolyl β‐D‐galactoside (X‐Gal) per millilitre in dimethylformamide; 40 mm citric acid/sodium phosphate (pH 6.0); 5 mm potassium ferrocyanide; 5 mm potassium ferricyanide; 150 mm sodium chloride; 2 mm magnesium chloride. The X‐Gal solution had to be added just before use. After 2–4 h of incubation, it was possible to observe the blue‐green staining, that was maximal after 12–16 h.

5‐Bromo‐2′‐deoxyuridine staining

Pre‐adipocytes at the 6th and 16th passages in vitro were seeded in sterile flasks at a density of 6 × 103 per cm2 in DMEM/Ham's F‐12 (1 : 1) with 10% FBS. Cell population growth and antibody staining for detection of 5‐bromo‐2′‐deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation has been shown previously by Dolbeare et al. (1983). Briefly, when pre‐adipocytes reached exponential growth, BrdU at a final concentration of 10 µm was added to the culture medium for 45 min at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Then, cells were detached with trypsin 0.05%–sodium EDTA 0.02% solution, and were centrifuged and washed once with cold PBS. Pellets were gently re‐suspended in 200–300 µL of PBS and cells were fixed by dropping them slowly into ice cold 70% ethanol; finally, they incubated at 4 °C for at least 30 min. Next, they were washed once with cold PBS and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 2 N HCl/Triton X‐100 to denature the DNA. After DNA denaturation, cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Tween‐20 in PBS, and were incubated with anti‐BrdU, pure diluted 1 : 10 (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) in Tween‐20 0.5% in PBS plus 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Cells were washed with PBS and then incubated with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 F(ab′) fragment of goat antimouse IgG (H + L), Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) diluted 1 : 500 in Tween‐20 0.5% in PBS, for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Finally, cells were washed once with cold PBS, re‐suspended in propidium iodide and RNAsi solution (Becton Dickinson) and stored at 4 °C overnight in the dark. Samples were acquired by FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and data were analyzed by Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson).

Carboxyl fluorescein succinimidyl ester staining

Carboxyl fluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) staining was performed as follows: 1 day before seeding, cells were washed three times with PBS and were incubated in the dark for 10 min at 37 °C in 5% CO2 with 5 µm CFSE solution in PBS, then washed three times with PBS, added with 10% FBS (Urbani et al. 2006). Pre‐adipocytes at the 6th and 16th passages in vitro were seeded in sterile flasks at a density of 4000 per cm2 in DMEM/Ham's F‐12 (1 : 1) with 10% FBS. Pre‐adipocytes at different times after CSFE staining (1, 2, 5 and 9 days) were harvested using trypsin 0.05%–sodium EDTA 0.02% solution, centrifuged, and washed in PBS. Samples were acquired using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). FACS data analysis was performed using Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson) and ModFit (Mac3.1 SP2, Verity Software House Inc., Topsham, ME, USA).

Immunocytochemistry

Pre‐adipocytes, treated and untreated with PDRN (100 µg/mL) for 24, 48 and 72 h, were cultured using Laboratory‐Tek™ II Chamber Slide™ System (Nunc A/S, Roskilde, Denmark) and were fixed with absolute methanol at –20 °C for 4 min. Monoclonal antihuman Ki‐67 (BGX‐Ki67 clone, 1 : 30, BioGenex, San Ramon, CA, USA), a cell proliferation marker, was used. Super Sensitive™ Link‐Label Detection Systems Concentrated Format (BioGenex), avidin‐biotin complex technique (Hsu et al. 1981; Van der Loos et al. 1989) and 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB chromogen, BioGenex) were used as the chromogen. Counterstaining with haematoxylin was performed to identify the cells.

RESULTS

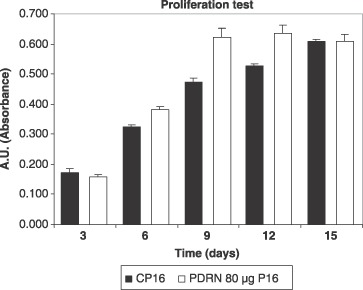

Level of senescence of the pre‐adipocytes was verified at the 6th and 16th passages in vitro by the senescence‐associated β‐gal assay (Fig. 1). The results obtained were: 4 senescent pre‐adipocytes per 133 cells (3%) per mm2 at the 6th in vitro passage and 7 senescent pre‐adipocytes per 133 cells (5.2%) per mm2 at the 16th in vitro passage. Our data represent means of three separate experiments in duplicate. The BrdU assay showed that only 1% (6th passage) and 2% (16th passage) of cells were in S phase, the greater amount of being in G0 phase (Fig. 2). Pre‐adipocyte proliferation was assessed at different time points, comparing the 6th and 16th passages. At 24 h after CFSE staining, both samples displayed only the parental peak. After 5 and 9 days, we confirmed modest proliferation activity; pre‐adipocytes at the 16th passage showed virtually five generations but cells at the 6th passage possessed virtually six generations without parental peak (Fig. 3). The effect of PDRN treatment on pre‐adipocytes at the 6th and 16th passages was demonstrated by our following experiments. Index of viability showed no toxic effects of PDRN for each dose (80 and 100 µg/mL) and experimental time (24, 48 and 72 h) (Table 1). The proliferation MTT test of human pre‐adipocytes is shown in 4, 5. In these graphics, the values represent averages of three different experiments in quadruplicate and show that PDRN treatment had no significant effect on pre‐adipocyte population growth at the 6th passage. On the other hand, PDRN treatment on pre‐adipocytes at the 16th passage seemed to indicate an enhancement of growth rate compared to the untreated controls. We could also affirm that cell proliferation under the effect of PDRN showed a time‐dependent response. After 15 days of treatment, proliferation of pre‐adipocytes, both at the 6th and 16th passages, seemed to reach a saturation point, displaying a lower proliferative effect of PDRN. Moreover, we evaluated the cells using trypan blue staining in the same experimental conditions as the proliferation MTT test, as represented in 6, 7. We also employed DNA assay with 80 µg/mL PDRN on pre‐adipocytes at the 6th and 16th passages for 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 days to confirm results obtained previously, and values are shown in 8, 9. Cell proliferation was estimated by referring fluorescence units to a linear standard curve for DNA fluorescence versus cell number of three different experiments in duplicate. After 3 days, the difference in growth rate between PDRN‐treated and untreated cells was not relevant, and only on the 6th day did it reach significance between the two groups (P < 0.05), mainly at the 16th passage, as shown in Fig. 8. By immunocytochemistry, Ki‐67 nuclear expression was prevalently displayed in the treated pre‐adipocytes, in comparison with the untreated ones (Fig. 10). Bearing these results in mind, we counted numbers of mitoses in PDRN‐treated pre‐adipocytes and in controls by staining with haematoxylin and eosin. The results revealed that mitosis of pre‐adipocytes treated with 80 µg/mL PDRN was greater than that observed in control pre‐adipocytes (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Senescence‐associated β‐galactosidase assay in pre‐adipocytes at the 6th (a) and 16th (b) passages in vitro. The blue‐green staining represents senescent cells (original magnification ×100).

Figure 2.

BrdU staining in human pre‐adipocytes at the 6th (P6) and 16th (P16) passages in vitro. The axis of graphics illustrate propidium iodide (PI) versus secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 488 F(ab′) fragment of goat antimouse IgG (H + L); 1% pre‐adipocytes at P6 and 2% pre‐adipocytes at P16 are in S phase.

Figure 3.

CFSE staining in human pre‐adipocytes at the 6th (P6) and 16th (P16) passages at different times (1, 2, 5 and 9 days).

Table 1.

Effect of the treatment with PDRN 100 and 80 µg/mL for 24, 48 and 72 h on the viability of human pre‐adipocytes to passages 6 and 16, as evaluated by MTT assay

| Treatment | MTT P6 | MTT P16 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | PDRN (100 µg/mL) | PDRN (80 µg/mL) | Control | PDRN (100 µg/mL) | PDRN (80 µg/mL) | |

| 24 h | 100 | 100 ± 0.1 | 100 ± 0.1 | 100 | 100 ± 0.5 | 100 ± 2 |

| 48 h | 100 | 100 ± 0 | 100 ± 0.6 | 100 | 96 ± 1 | 100 ± 4 |

| 72 h | 100 | 100 ± 0.5 | 100 ± 1 | 100 | 92 ± 1 | 98 ± 1 |

| Values are expressed as percentage of the untreated controls, and represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments in quadruplicate. | ||||||

Figure 4.

Effect of PDRN on the growth of cultured human pre‐adipocytes at the 16th passage in vitro. Cells were cultured in the experimental conditions in the absence and in the presence of 80 µg/mL PDRN for 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 days. Values are expressed as an arbitrary unit (the absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 570 nm), and represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments in quadruplicate. *P < 0.05, compared to control by analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's test.

Figure 5.

Effect of PDRN on the growth of cultured human pre‐adipocytes at the 6th passage in vitro. Cells were cultured in the experimental conditions in the absence and in the presence of 80 µg/mL PDRN for 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 days. Values are expressed as an arbitrary unit (the absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 570 nm) and represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments in quadruplicate.

Figure 6.

Effect of PDRN on the growth of cultured human pre‐adipocytes at the 16th passage in vitro. Cells were cultured in the experimental conditions in the absence and in the presence of 80 µg/mL PDRN for 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 days. Cell counting was measured by Trypan blue staining. Values are expressed as a cell number and represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments in quadruplicate.

Figure 7.

Effect of PDRN on the growth of cultured human pre‐adipocytes at the 6th passage in vitro. Cells were cultured in the experimental conditions in the absence and in the presence of 80 µg/mL PDRN for 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 days. Cell counting was measured by Trypan blue staining. Values are expressed as a cell number and represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments in quadruplicate.

Figure 8.

Effect of PDRN on the growth of cultured human pre‐adipocytes at the 16th passage in vitro. Cells were cultured in the experimental conditions in the absence and in the presence of 80 µg/mL PDRN for 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 days. Cell proliferation was estimated by referring fluorescence units to a linear standard curve for DNA fluorescence versus cell number, and represent the mean ± SEM of two separate experiments in duplicate. *P < 0.05, compared to control by analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's test.

Figure 9.

Effect of PDRN on the growth of cultured human pre‐adipocytes at the 6th passage in vitro. Cells were cultured in the experimental conditions, in the absence and in the presence of 80 µg/mL PDRN for 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 days. Cell proliferation was estimated by referring fluorescence units to a linear standard curve for DNA fluorescence versus cell number, and represent the mean ± SEM of two separate experiments in duplicate. *P < 0.05, compared to control by analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's test.

Figure 10.

Immunostaining with Ki‐67 antibody: (a) in untreated pre‐adipocytes (original magnification ×600) and (b) in pre‐adipocytes treated with PDRN (100 µg/mL) (original magnification ×600), as shown by the arrows.

DISCUSSION

As shown in previous pieces of research (Rathbone et al. 1992; Muratore et al. 1997, 2003; Guizzardi et al. 2003), PDRN can stimulate the growth of osteoblasts, fibroblasts and other kind of cells in vitro. PDRN, as described before, is a sterile, apirogen pure substance constituted of more then 95% (generally 99%) deoxyribonucleotide polymers of different lengths (from 50 to 2000 base pairs). It was observed by Guizzardi et al. (2003), Rubegni et al. (2001) and Sini et al. (1999) that nucleotides and nucleosides may operate on cell proliferation in two different ways: they can stimulate nucleic acid synthesis through the salvage pathways (Pickard & Kinsella 1996; Nakamura et al. 2000) and they can bind and activate purinergic receptors (Rathbone et al. 1992; Thellung et al. 1999; , Nakamura et al. 2000), in particular, P1 and P2 receptors, which bind nucleosides and nucleotides, respectively. In this report, we have discussed the PDRN effect on pre‐adipocyte cell cultures. These types of cell are abundant and easily found after suction‐assisted lipectomy (liposuction) as discarded tissue from surgical interventions. As mentioned above, pre‐adipocytes are multipotent cells, differentiating in vitro along numerous lineages, such as adipocytes, chondrocytes, osteoblasts, myocytes, neuronal cells, pancreatic and hepatic lineages (Ashjian et al. 2003; Shi & Cheng 2004; Seo et al. 2005; Timper et al. 2006). For that reason, pre‐adipocytes could be used in the future for cell therapy and tissue engineering (Katz et al. 1999); they could be employed in regeneration of damaged tissues and in treatment of several disorders (diabetes mellitus, musculoskeletal, nervous and hepatic diseases) in combination with appropriate biomaterials (Shaffler & Buchler 2007). We have analysed pre‐adipocytes at different passages in vitro (P6 and P16) as we wanted to understand the effect of PDRN on early and mature cells. Cellular senescence is a phenomenon which develops when normal diploid cells lose the ability to divide. In general, mesenchymal stem cells, like pre‐adipocytes, have low levels of senescence (Zuk et al. 2001; Mizuno & Hyakusoku 2003). By the β‐galactosidase test, we observed an increase in positive cell numbers from 6th to 16th passages. Measurement of cell proliferation using BrdU was carefully examined by multicolour flow cytometry and microscopic analysis (Forster et al. 1989; Brockhoff et al. 2001; Leif et al. 2004; , Rothaeusler & Baumgarth 2006). BrdU staining has been applied in different cell lines used for immunocytochemistry and immunofluorescence (Coltrera & Gown 1991), it becomes incorporated into nuclear DNA of dividing cells (Gratzner 1982). We verified that there was no a significant difference between amounts of cells in G0 and S phases between pre‐adipocytes in the two passages. In our opinion, S phase was restricted because our cells originated from adult adipose tissue and were not stabilized cell lines. A further test to determine proliferation of pre‐adipocytes at the 6th and 16th passages was CSFE staining. The CSFE method has previously been applied for labelling human pre‐adipocytes (Hemmrich et al. 2006) leucocytes and lymphocytes (De Clerck et al. 1994; Urbani et al. 2006). CSFE has the ability to covalently label long‐lived intracellular molecules with the fluorescent dye, carboxyfluorescein. Following each cell division, the equal distribution of this fluorescent molecule to progeny cells results in halving of the fluorescence to each daughter cell (Quah et al. 2007). Our more significant discovery was that pre‐adipocytes at the 6th passage showed six generations after 9 days of treatment and at the same time, we verified the loss of a parental peak. Otherwise, pre‐adipocytes at the 16th passage had five generations only, and we found parental peak yet. According to these considerations, we could affirm that pre‐adipocytes at the 6th passage possess a higher capability of proliferation. Therefore, we thought to use these different passages for our studies. At the beginning, we observed that the effect of PDRN (80–100 µg/mL) on our cells was not toxic during the exposure time (24, 48 and 72 h). According to these considerations, we decided to use only one PDRN concentration (80 µg/mL) in subsequent analysis and at the same time, to extend treatment up to 15 days. However, on the contrary to what we thought at the beginning of this work, pre‐adipocytes at the 16th passage seem to grow more than pre‐adipocytes at the 6th passage. In the MTT test, this enhancement is clearer to the 12th day, while in the DNA assay the point of saturation of pre‐adipocyte proliferation seems to be 9 days. Similar results were obtained by corresponding cell counting. The answer to this strange behaviour is perhaps connected to a major adaptation of cells at the 16th passage in these culture conditions and external stimulation. The fibroblast‐like morphology of treated and untreated cells at all passages is similar; finally, by immunocytochemical analysis, we have found a prevalent presence of Ki‐67 in PDRN‐treated pre‐adipocytes, indicative of cell proliferation. At the same time, we observed an increase in mitoses in PDRN‐treated pre‐adipocytes. According to these considerations, we could deduce that both provided evidence for enhancement in proliferation in treated cells. The Ki‐67 is a 360‐kDa protein which is expressed by proliferating cells in all phases of the active cell cycle (G1, S, G2 and M phases). In G1 phase, the Ki‐67 antigen is predominantly localized in the perinucleolar region, but in the later phases of the cell cycle it is also detected throughout the nuclear interior, being predominantly localized in the nuclear matrix. In mitosis, the Ki‐67 antigen is present in all chromosomes and appears in a reticulate structure surrounding metaphase chromosomes (Bullwinkel et al. 2006). Thus, presence of the Ki‐67 antigen is strictly associated with the cell cycle and is confined to the nucleus, suggesting an important role of this structure in the maintenance and/or regulation of the cell division cycle. From analysis of our data, we can conclude that PDRN also can stimulate proliferation of pre‐adipocytes. The effect of PDRN does not seem to be so remarkable; perhaps it is due to the origin of our particular cells, that is, adult adipose tissue. In our opinion, this research is a good starting point for further investigation of differentiated pre‐adipocytes in various lineages, such as hepatic and pancreatic. In future, we propose to study pre‐adipocyte cells at passages above the 16th in vitro, to evaluate and to confirm our hypothesis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the skilful help of Prof. C. Falugi, Dr. M. G. Aluigi, Dr. L. Mastracci, Dr. M. Zacco and Mr. L. Mastrobuono. Thanks also to Drs G. Cattarini and O. Cattarini, Mastelli s.r.l., Sanremo, Italy, for providing and assistance in preparation of PDRN.

REFERENCES

- Ashjian PH, Elbarbary AS, Edmonds B, Deugarte D, Zhu M, Zuk PA, Lorenz HP, Benhaim P, Hedrick MH (2003) In vitro differentiation of human processed lipoaspirate cells into early neural progenitors. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 111, 1922–1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astori G, Vignati F, Bardelli S, Tubio M, Gola M, Albertini V, Bambi F, Scali G, Castelli D, Rasini V, Soldati G, Moccetti T (2007) ‘In vitro’ and multicolor phenotypic characterization of cell subpopulations identified in fresh human adipose tissue stromal vascular fraction and in the derived mesenchymal stem cells. J. Transl. Med. 5, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belletti S, Uggeri J, Gatti R, Govoni P, Guizzardi S (2007) Polydeoxyribonucleotide promotes cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer repair in UVB‐exposed dermal fibroblasts. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 23, 242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigliardi P (1982) Treatment of acute radiodermatitis of first and second degrees with semi‐greasy placenta ointment. Int. J. Tissue React. 4, 153–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitto A, Minatoli L, Polito F, Altavilla D, Cattarini G, Squadrito F (2006) Polydeoxyribonucleotide improve angiogenesis and wound healing in experimental burn wounds In: 8th International Symposium on Adenosine and Adenine Nucleotides. Ferrara, Italy: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler WB, Buckley KA, Gartland A, Hipskind RA, Bilbe G, Gallagher JA (2001) Extracellular nucleotide signaling: a mechanism for integrating local and systemic responses in the activation of bone remodelling. Bone 28, 507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockhoff G, Heiss P, Schlegel J, Hofstaedter F, Knuechel R (2001) Epidermal growth factor receptor, c‐erbB2 and c‐erbB3 receptor interaction, and related cell cycle kinetics of SK‐BR‐3 and BT474 breast carcinoma cells. Cytometry 44, 338–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullwinkel J, Baron‐Lühr B, Lüdemann A, Wohlenberg C, Gerdes J, Scholzen T (2006) Ki‐67 protein is associated with ribosomal RNA transcription in quiescent and proliferating cells. J. Cell Physiol. 206, 624–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan AJ, Haley BE, Volkin DB, Marfia KE, Verticelli AM, Bruner MW, Draper JP, Burke CJ, Middaugh CR (1994) Interaction of nucleotides with acidic fibroblasts growth factor (FGF‐1). Biochemistry 33, 7193–7202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltrera MD, Gown AM (1991) PCNA/cyclin expression and BrdU uptake define different subpopulations in different cell lines. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 39, 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clerck LS, Bridts CH, Mertens AM, Moens MM, Stevens WJ (1994) Use of fluorescent dyes in the determination of adherence of human leucocytes to endothelial cells and the effect of fluorochromes on cellular function. J. Immunol. Methods 172, 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ugarte DA, Morizono K, Elbarbary A, Alfonso Z, Zuk PA, Zhu M, Dragoo JL, Ashjian P, Thomas B, Benhaim P, Chen I, Fraser J, Hedrick MH (2003) Comparison of multi‐lineage cells from human adipose tissue and bone marrow. Cells Tissues Organs 174, 101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira‐Smith O, Peacocke M (1995) A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo . Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 9363–9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingji W, Ning‐Na H, Heppel LA (1990) Extracellular ATP shows synergistic enhancement of DNA synthesis when combined with agents that are active in wound healing or as neurotransmitters. Biochem. Biophs. Res. Commun. 166, 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolbeare F, Gratzner H, Pallavicini MG, Gray JW (1983) Flow cytometric measurement of total DNA content and incorporated bromodeoxyuridine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 80, 5573–5577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgington SM (1992) DNA and RNA therapeutics: unsolved riddles. Biotechnology 10, 993–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster I, Vieira P, Rajewsky K (1989) Flow cytometric analysis of cell proliferation dynamics in the B cell compartment of the mouse. Int. Immunol. 1, 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gailit J, Clark AF (1994) Wound repair in the context of extracellular matrix. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 6, 717–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gary RK, Kindell SM (2005) Quantitative assay of senescence‐associated β‐galactosidase activity in mammalian cell extracts. Anal. Biochem. 343, 329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimble JM, Guilak F (2003) Adipose‐derived adult stem cells: isolation, characterization and differentiation potential. Cytotherapy 5, 362–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratzner HG (1982) Monoclonal antibody to 5‐bromo and 5‐iododeoxy‐uridine: a new reagent for detection of DNA replication. Science 218, 474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronthos S, Franklin DM, Leddy HA, Robey PG, Storms RW, Gimble JM (2001) Surface protein characterization of human adipose tissue‐derived stromal cells. J. Cell Physiol. 189, 54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guizzardi S, Galli C, Govoni P, Boratto R, Cattarini G, Martini D, Belletti S, Scandroglio R (2003) Polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) promotes human osteoblast proliferation: a new proposal for bone tissue repair. Life Sci. 73, 1973–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guizzardi S, Martini D, Baccelli B, Valdatta L, Thione A, Scaloni S, Uggeri J, Ruggeri A (2007) Effects of heat deproteinate bone and polynucleotides on bone regeneration: an experimental study on rat. Micron 38, 722–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmrich K, Meersch M, Von Heimburg D, Pallua N (2006) Applicability of the dyes CFSE, CM‐DiI and PKH26 for tracking of human pre‐adipocytes to evaluate adipose tissue engineering. Cells Tissues Organs 184, 117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning UG, Wang Q, Gee NH, Borstel RC (1996) Protection and repair of gamma radiation‐induced lesions in mice with DNA or deoxyribonucleotides treatments. Mutat. Res. 35, 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H (1981) Use of avidin‐biotin‐peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques: a comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 29, 577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz AJ, Llull R, Hedrick MH, Furtrell JW (1999) Emerging approaches to the tissue engineering of fat. Clin. Plast. Surg. 26, 587–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarotto M, Tomasello EM, Caporossi A (2004) Clinical evaluation of corneal epithelialization after photorefractive keratectomy in patients treated with polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) eye drops: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 14, 284–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leif RC, Stein JH, Zucker RM (2004) A short history of the initial application of anti‐5‐BrdU to the detection and measurement of S phase. Cytometry 58, 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo MJ, Suh SY, Bae YC, Jung JS (2005) Differentiation of human adipose stromal cells into hepatic lineage in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophs. Res. Coummun. 328, 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno H, Hyakusoku H (2003) Mesengenic potential and future clinical perspective of human processed lipoaspirate cells. J. Nippon Med. Sch. 70, 300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T (1983) Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 65, 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratore O, Cattarini G, Gianoglio S, Tonoli EL, Sacca SC, Ghiglione D, Venzano D, Ciurlo C, Lantieri PB, Schito GC (2003) A human placental polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) may promote the growth of human corneal fibroblasts and iris pigment epithelial cells in primary culture. New Microbiol. 26, 13–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratore O, Pesce Schito A, Cattarini G, Tonoli EL, Gianoglio S, Schiappacasse S, Felli L, Picchetta F, Schito GC (1997) Evaluation of the trophic effect of human placental polydeoxyribonucleotide on human knee skin fibroblasts in primary culture. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 53, 279–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musk P, Campbell R, Staples J, Moss D, Parson PG (1989) Solar and UVC‐induced mutation in human cells and inhibition by deoxyribonucleosides. Mutat. Res. 227, 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura E, Uezono Y, Narusawa K, Shibuya I, Oishi Y, Tanaka M, Yanaggihara N, Nakamura T, Izumi F (2000) ATP activates DNA synthesis by acting on P2X receptors in human osteoblasts like MG‐63 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, C510–C519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard M, Kinsella A (1996) Influence of both salvage and DNA damage response pathways on resistance to chemotherapeutic antimetabolites. Biochem. Pharmacol. 52, 425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quah BJ, Warren HS, Parish CR (2007) Monitoring lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and in vivo with the intracellular fluorescent dye carboxyfluorescein diacetate. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2049–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao J, Otto WR (1992) Fluorimetric DNA assay for cell growth estimation. Anal. Biochem. 207, 186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposio E, Guida C, Baldelli I, Benvenuto F, Curto M, Paleari L, Filippi F, Fiocca R, Robello G, Santi PL (2007) Characterization and induction of human pre‐adipocytes. Toxicol. In Vitro 21, 330–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathbone MP, Middlemiss PJ, Gysbers JW, De Forge S, Costello P, Del Mastro RF (1992) Purine nucleosides and nucleotides stimulate proliferation of a wide range of cell types. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. 28A, 529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothaeusler K, Baumgarth N (2006) Evaluation of intranuclear BrdU detection procedures for use in multicolor flow cytometry. Cytometry 69, 249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubegni P, De Aloe G, Mazzatenta C, Cattarini L, Fimiani M (2001) Clinical evaluation of the trophic effect of polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) in patients undergoing skin explants. A pilot study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 17, 128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffler A, Buchler C (2007) Concise review: adipose tissue‐derived stromal cells‐basic and clinical implications for novel cell‐based therapies. Stem Cells 25, 818–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi CM, Cheng TM (2004) Differentiation of dermis‐derived multipotent cells into insulin producing pancreatic cells in vitro . World J. Gastroenterol. 10, 2550–2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sini P, Denti A, Cattarini G, Daglio M, Tira ME, Balduini C (1999) Effect of polydeoxyribonucleotides on human fibroblasts in primary culture. Cell Biochem. Funct. 17, 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strem BM, Hicok KC, Zhu M, Wulur I, Alfonso Z, Schreiber RE, Fraser JK, Hedrick MH (2005) Multipotential differentiation of adipose tissue‐derived stem cells. Keio J. Med. 54, 132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thellung S, Florio T, Maragliano A, Cattarini G, Schettini G (1999) Polydeoxyribonucleotides enhance the proliferation of human skin fibroblasts: involvement of A2 purinergic receptor subtypes. Life Sci. 64, 1661–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timper K, Seboek D, Eberhardt M, Linscheid P, Christ‐Crain M, Keller U, Muller B, Zulewski H (2006) Human adipose tissue‐derived mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into insulin, somatostatin, and glucagon expressing cells. Biochem. Biophs. Res. Commun. 341, 1135–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbani S, Caporale R, Lombardini L, Bosi A, Saccaridi R (2006) Use of CFDA‐SE for evaluating the in vitro proliferation pattern of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotherapy 8, 243–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Loos CM, Das PK, Van den Oord JJ, Houthoff HJ (1989) Multiple immunoenzyme staining techniques. Use of fluoresceinated, biotinylated and unlabelled monoclonal antibodies. J. Immunol. Methods 117, 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, De Ugarte DA, Huang J, Mizuno H, Alfonso ZC, Fraser JK, Benhaim P, Hedrick MH (2002) Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 4279–4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, Huang J, Futrell JW, Katz AJ, Benhaim P, Lorenz HP, Hedrick MH (2001) Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implication for cell‐based therapies. Tissue Eng. 7, 211–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]