Doravirine is a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Due to the high prevalence of HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection and coadministration of HIV-1 and HCV treatment, potential drug-drug interactions (DDIs) between doravirine and two HCV treatments were investigated in two phase 1 drug interaction trials in healthy participants.

KEYWORDS: HIV, doravirine, drug-drug interactions, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)

ABSTRACT

Doravirine is a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Due to the high prevalence of HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection and coadministration of HIV-1 and HCV treatment, potential drug-drug interactions (DDIs) between doravirine and two HCV treatments were investigated in two phase 1 drug interaction trials in healthy participants. Trial 1 investigated the effect of multiple-dose doravirine and elbasvir + grazoprevir coadministration (N = 12), and trial 2 investigated the effect of single-dose doravirine and ledipasvir-sofosbuvir coadministration (N = 14). Doravirine had no clinically relevant effect on the pharmacokinetics of elbasvir, grazoprevir, ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, or the sofosbuvir metabolite GS-331007. Coadministration of elbasvir + grazoprevir with doravirine moderately increased doravirine area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24), maximal concentration (Cmax), and concentration 24 h postdose (C24), with geometric least-squares mean ratio (GMR) with 90% confidence intervals (CI) of 1.56 (1.45, 1.68), 1.41 (1.25, 1.58), and 1.61 (1.45, 1.79), respectively. Doravirine AUC0–∞, Cmax, and C24 values increased slightly following coadministration with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir (GMR [90% CI] of 1.15 [1.07, 1.24], 1.11 [0.97, 1.27], and 1.24 [1.13, 1.36], respectively). The modest increases in doravirine exposure are not clinically meaningful based on the therapeutic profile of doravirine. Effects are likely secondary to cytochrome P450 3A and P-glycoprotein inhibition by grazoprevir and ledipasvir, respectively. Coadministration of doravirine with elbasvir + grazoprevir or ledipasvir-sofosbuvir was generally well tolerated. Clinically relevant DDIs are not expected to occur between doravirine and elbasvir-grazoprevir or ledipasvir-sofosbuvir at the therapeutic doses.

INTRODUCTION

Doravirine (MK-1439) is a novel nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Doravirine has demonstrated robust and durable efficacy and is generally safe and well tolerated (1, 2). It is administered with other antiretroviral agents or as a three-drug single-tablet regimen with lamivudine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (3, 4). Doravirine has a favorable resistance profile that is distinct from those of other NNRTIs, with in vitro activity against wild-type HIV-1 and prevalent NNRTI resistance mutations (reverse transcriptase mutations K103N, Y181C, G190A, and K103N/Y181C) and rilpivirine-associated mutants (e.g., E138K) (5). Doravirine is primarily metabolized via cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A)-mediated oxidation (6). While in vitro data demonstrate that doravirine is a substrate for P-glycoprotein (P-gp) (6), P-gp is not expected to play an important role in the absorption or disposition for doravirine based on clinical drug-drug interaction (DDI) data (7, 8). In vitro studies have demonstrated that doravirine does not inhibit the activity of major CYP enzymes, including CYP3A, or uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1), and is not a meaningful inducer of CYP1A2, 2B6, or 3A4 (9). In addition, doravirine does not have a clinically relevant effect on CYP3A, as evaluated in a DDI trial with midazolam, a sensitive CYP3A substrate (10). Due to doravirine showing no inhibitory effect on organic anion transporter 1 (OAT1) and only a weak inhibitory effect on breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), organic anion transporter polypeptide (OATP)-1B1, OATP-1B3, OAT3, and organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2) in vitro, the potential for clinically relevant interactions with substrates of these transporters with therapeutic concentrations of doravirine is thought to be unlikely (9). Doravirine is therefore considered to have low potential for perpetrating DDIs, although as a CYP3A substrate it is susceptible to DDIs with drugs that modulate CYP3A activity.

HIV-infected individuals are at high risk of hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection due to overlapping modes of transmission and affected populations. It is estimated that intravenous drug users constitute 58% of the global burden of HCV coinfections in HIV-infected individuals (11). Based on a meta-analysis of studies published between 2002 and 2015, there are approximately 2.3 million individuals worldwide with HIV-HCV coinfection, equaling an overall coinfection prevalence in HIV-infected individuals of 6.2% (11). In intravenous drug users, HIV-HCV coinfection prevalence is more than 80% in six global regions, including central and eastern Europe, south and southeast Asia, and North America, where there are large populations of these individuals with concentrated HIV epidemics (11). As AIDS-related mortality has decreased following the introduction of antiretroviral therapy, liver disease, including that caused by HCV, has emerged as a major cause of mortality in the HIV-infected population (12, 13). HIV-1 infection influences the progression of HCV infection by both increasing the likelihood of chronic disease developing and expediting the progression of fibrosis to cirrhosis (12).

There are a number of medications available for the treatment of HCV infection. Chronic infection with HCV genotype 1 or 4 can be treated with a fixed-dose combination of 50 mg elbasvir and 100 mg grazoprevir (14–16). Grazoprevir is taken up into the liver via OATP1B (14). Elimination of grazoprevir and elbasvir is predominantly via feces as the parent compound and as CYP3A oxidative metabolites (14). Grazoprevir is also a substrate of P-gp (14, 17), a weak CYP3A inhibitor, and a BCRP inhibitor (14, 17, 18). Elbasvir is also a substrate of P-gp and a BCRP inhibitor (14, 17). Elbasvir has minimal intestinal P-gp inhibition and does not inhibit CYP3A (14, 17). For clarity, throughout the manuscript, the fixed-dose combination of 50 mg elbasvir and 100 mg grazoprevir is referred to as elbasvir-grazoprevir; the non-fixed-dose combination is denoted elbasvir + grazoprevir.

Another option for the treatment of chronic HCV infection of genotype 1, 4, 5, or 6 is a once-daily, fixed-dose combination of 90 mg ledipasvir and 400 mg sofosbuvir (19). Ledipasvir is excreted mainly in an unmetabolized form (19). Sofosbuvir is a nucleotide analog prodrug that, after ingestion, is quickly converted to the predominant circulating metabolite GS-331007, which accounts for >90% of systemic exposure of the drug (20). Although GS-331007 is not the active moiety, it has been monitored as a surrogate for the active moiety, which cannot be readily measured in blood (21). Neither ledipasvir nor sofosbuvir is a substrate for CYP enzymes (19), but both are substrates for P-gp and BCRP, while GS-331007 is not, and ledipasvir is an inhibitor of P-gp and BCRP (19, 20).

Due to the likelihood of doravirine being coadministered with elbasvir-grazoprevir or ledipasvir-sofosbuvir, it is important to establish if any DDIs result from inhibition of any of the disposition pathways of coadministered drugs. Several existing HIV-1 medications are contraindicated with HCV medications. Elbasvir-grazoprevir is contraindicated for coadministration with the CYP3A inducer efavirenz, due to the resulting significant decrease in elbasvir and grazoprevir plasma concentrations, and with protease inhibitors atazanavir, darunavir, lopinavir, saquinavir, and tipranavir due to increased grazoprevir plasma concentrations caused by OATP-1B1/3 inhibition (14). Coadministration of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir is not recommended with combination elvitegravir-cobicistat/emtricitabine-tenofovir disoproxil fumarate due to the resulting increase in tenofovir concentration or with tipranavir-ritonavir due to decreased plasma concentrations of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir (19).

Based on the potential for DDIs between doravirine and medications commonly prescribed to treat HCV infection, it is essential to understand the pharmacokinetic (PK) interactions in order to inform selection of appropriate treatment regimens. The current work was conducted to evaluate the interaction of 100 mg of doravirine, the approved dose in the United States (3, 4), and either elbasvir + grazoprevir or ledipasvir-sofosbuvir, as well as the safety and tolerability of coadministration.

RESULTS

Trial 1, elbasvir + grazoprevir. (i) Trial population.

Twelve healthy adult male and female participants were enrolled, and all participants completed the trial; participant demographics are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Disposition and demographic characteristics

| Parametera | Value(s) for trial: |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 (elbasvir + grazoprevir) | 2 (ledipasvir-sofosbuvir) | |

| Enrolled, N | 12 | 14 |

| Completed, n (%) | 12 (100) | 14 (100) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 5 (41.7) | 12 (85.7) |

| Female | 7 (58.3) | 2 (14.3) |

| Age, yr | ||

| Mean (SD) | 34.7 (11.0) | 38.1 (10.3) |

| Median (range) | 29.0 (25–55) | 36.0 (25–60) |

| Weight, kg [mean (range)] | 73.1 (51.9–84.3) | 78.0 (56.1–92.9) |

| BMI, kg/m2 [mean (range)] | 26.2 (21.1–31.7) | 25.2 (19.6–30.9) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Native American or Alaska Native | 1 (8.3) | 1 (7.1) |

| Black or African American | 2 (16.7) | 3 (21.4) |

| White | 9 (75.0) | 10 (71.4) |

| Ethnicity, n (%), Hispanic or Latino | 3 (25.0) | 1 (7.1) |

BMI, body mass index; N, number of participants in population; n, number of participants in subpopulation; SD, standard deviation.

(ii) PK evaluations.

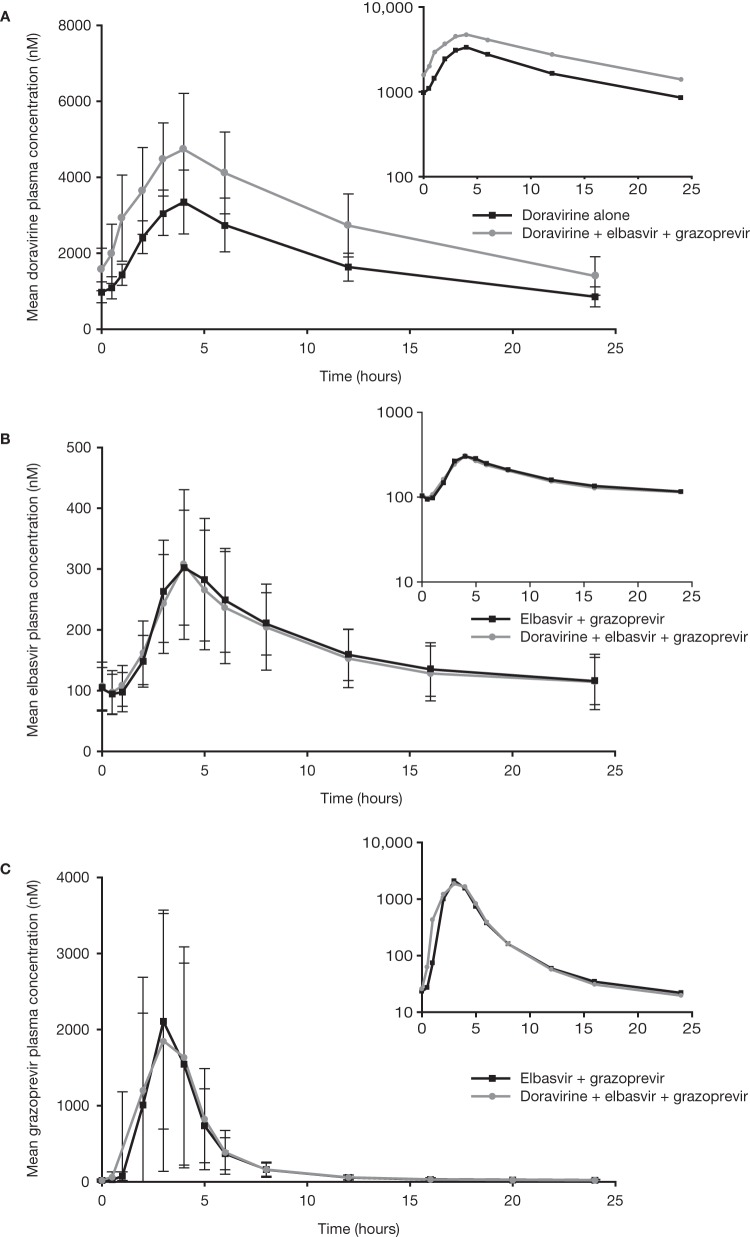

The PK for doravirine, elbasvir, and grazoprevir are given in Table 2. Mean concentration-time profiles for doravirine, elbasvir, and grazoprevir are shown in Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

Trial 1, elbasvir + grazoprevir, plasma PKa

| PK parameter | Doravirine alone |

Doravirine + elbasvir + grazoprevir |

GMR (90% CI) for (doravirine + elbasvir + grazoprevir)/(doravirine alone) | Pseudo-within-participant %CVc | Elbasvir + grazoprevir |

Doravirine + elbasvir + grazoprevir |

GMR (90% CI) for (doravirine + elbasvir + grazoprevir)/(elbasvir + grazoprevir) | Pseudo-within-participant %CVc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | GMb (95% CI) | N | GMb (95% CI) | N | GMb (95% CI) | N | GMb (95% CI) | |||||

| Doravirine | ||||||||||||

| AUC0–24 (μM·h) | 12 | 41.3 (35.5, 48.1) | 12 | 64.6 (54.1, 77.3) | 1.56 (1.45, 1.68) | 9.9 | ||||||

| Cmax (nM) | 12 | 3,400 (2,950, 3,910) | 12 | 4,770 (4,080, 5,590) | 1.41 (1.25, 1.58) | 16.1 | ||||||

| C24 (nM) | 12 | 814 (657, 1,010) | 12 | 1,310 (1,020, 1,690) | 1.61 (1.45, 1.79) | 14.4 | ||||||

| Tmax (h)d | 12 | 3.98 (3.00, 4.00) | 12 | 3.99 (2.98, 6.00) | ||||||||

| Elbasvir | ||||||||||||

| AUC0–24 (μM·h) | 12 | 3.89 (3.24, 4.67) | 12 | 3.73 (3, 4.63) | 0.96 (0.90, 1.02) | 8.5 | ||||||

| Cmax (nM) | 12 | 298 (238, 373) | 12 | 287 (222, 370) | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) | 7.2 | ||||||

| C24 (nM) | 12 | 110 (88.8, 136) | 12 | 106 (81.2, 138) | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) | 10.1 | ||||||

| Tmax (h)d | 12 | 4.00 (2.98, 5.00) | 12 | 4.00 (3.00, 5.00) | ||||||||

| Grazoprevir | ||||||||||||

| AUC0–24 (μM·h) | 12 | 5.64 (3.68, 8.66) | 12 | 6.05 (4.12, 8.87) | 1.07 (0.94, 1.23) | 18.5 | ||||||

| Cmax (nM) | 12 | 1,800 (1,090, 2,950) | 12 | 2,190 (1,400, 3,410) | 1.22 (1.01, 1.47) | 25.7 | ||||||

| C24 (nM) | 12 | 19.5 (14.2, 26.8) | 12 | 17.5 (12.9, 23.8) | 0.90 (0.83, 0.96) | 9.9 | ||||||

| Tmax (h)d | 12 | 3.00 (2.00, 4.00) | 12 | 3.00 (1.98, 4.00) | ||||||||

Plasma PK for doravirine, elbasvir, and grazoprevir following once-daily administration of 100 mg doravirine alone, 50 mg elbasvir + 200 mg grazoprevir, and coadministered 100 mg doravirine + 50 mg elbasvir + 200 mg grazoprevir in healthy adults. Doravirine alone, oral dose of 100 mg doravirine QD for 5 days; elbasvir + grazoprevir, oral dose of 50 mg elbasvir and 200 mg grazoprevir QD for 10 days; doravirine + elbasvir + grazoprevir, oral dose of 50 mg elbasvir and 200 mg grazoprevir administered QD for a total of 15 consecutive days (days 1 to 10 in period 2 and days 1 to 5 in period 3) and 100 mg doravirine QD (oral) on days 1 to 5 of period 3. Abbreviations: %CV, percent coefficient of variation; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; Cmax, maximum concentration; C24, plasma concentration 24 h postdose; GM, geometric least-square mean; GMR, geometric least-square mean ratio; N, number of participants; PK, pharmacokinetic; QD, once daily; Tmax, time of maximum plasma concentration.

Back-transformed least-square means and CI from mixed-effects model performed on natural log-transformed values of AUC0–24, Cmax, and C24.

Pseudo-within-participant %CV = 100 × sqrt[(σa2 + σb2 – 2σab)/2], where σa2 and σb2 are the estimated variances on the log scale for the two treatment groups and σab is the corresponding estimated covariance, each obtained from the linear mixed-effects model.

Median (minimum, maximum) values are reported for Tmax.

FIG 1.

Trial 1, elbasvir + grazoprevir, mean concentration-time profiles for doravirine, elbasvir, and grazoprevir. (A) Arithmetic mean (± standard deviation [SD]) doravirine plasma concentration versus time profiles following the administration of 100 mg doravirine once daily for 5 days alone and coadministered with 50 mg elbasvir and 200 mg grazoprevir once daily for 5 days in healthy adults (N = 12). (B and C) Arithmetic mean (±SD) elbasvir (B) and grazoprevir (C) plasma concentration versus time profiles following the administration of 50 mg elbasvir and 200 mg grazoprevir once daily for 10 days alone or coadministered with 100 mg doravirine once daily for 5 days in healthy adults (both N = 12). Main panels, linear scale; insets, semilog scale.

Doravirine area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24), maximal concentration (Cmax), and concentration 24 h postdose (C24), increased following coadministration with elbasvir and grazoprevir compared to those with doravirine alone; these increases were not considered clinically relevant. The geometric least-square mean ratios (GMRs) (90% confidence interval [CI]) of doravirine AUC0–24, Cmax, and C24 for (doravirine + elbasvir + grazoprevir)/doravirine were 1.56 (1.45, 1.68), 1.41 (1.25, 1.58), and 1.61 (1.45, 1.79), respectively. Doravirine time of maximum plasma concentration (Tmax) values were similar for both treatments.

The coadministration of doravirine did not have a clinically relevant effect on the PK values of elbasvir and grazoprevir. The GMRs (90% CI) of elbasvir AUC0–24, Cmax, and C24 for (doravirine + elbasvir + grazoprevir)/(elbasvir + grazoprevir) were 0.96 (0.90, 1.02), 0.96 (0.91, 1.01), and 0.96 (0.89, 1.04), respectively, and of grazoprevir were 1.07 (0.94, 1.23), 1.22 (1.01, 1.47), and 0.90 (0.83, 0.96), respectively.

(iii) Safety.

Multiple-dose doravirine at 100 mg once daily (QD) and multiple-dose elbasvir and grazoprevir were generally well tolerated when administered alone or together. A total of six participants (50%) reported 12 adverse events (AEs) after initation of the study drug(s), which included three posttrial AEs. The most common AEs were discolored feces, headache, and abnormal dreams. Four participants reported AEs that were considered drug related by the investigator. These included headache in one participant after receiving elbasvir and grazoprevir, abnormal dreams in two participants, one after receiving doravirine alone and one after receiving elbasvir and grazoprevir, and spontaneous abortion in one participant after receiving doravirine, elbasvir, and grazoprevir. The drug-related AE of spontaneous abortion was considered a serious AE (SAE) and occurred in one participant who became pregnant during the trial, approximately 1 month after the last dose of study drug. With the exception of the SAE of spontaneous abortion, which was categorized as severe in intensity, all of the AEs were mild in intensity, of limited duration, and resolved by the end of the trial. There were no deaths during the trial, and there were no discontinuations due to an AE. There were no consistent treatment-related changes in laboratory values, vital signs, or electrocardiograms (ECGs).

Trial 2, ledipasvir-sofosbuvir. (i) Trial population.

Fourteen healthy adult male and female participants were enrolled, and all participants completed the trial; participant demographics are shown in Table 1.

(ii) PK evaluations.

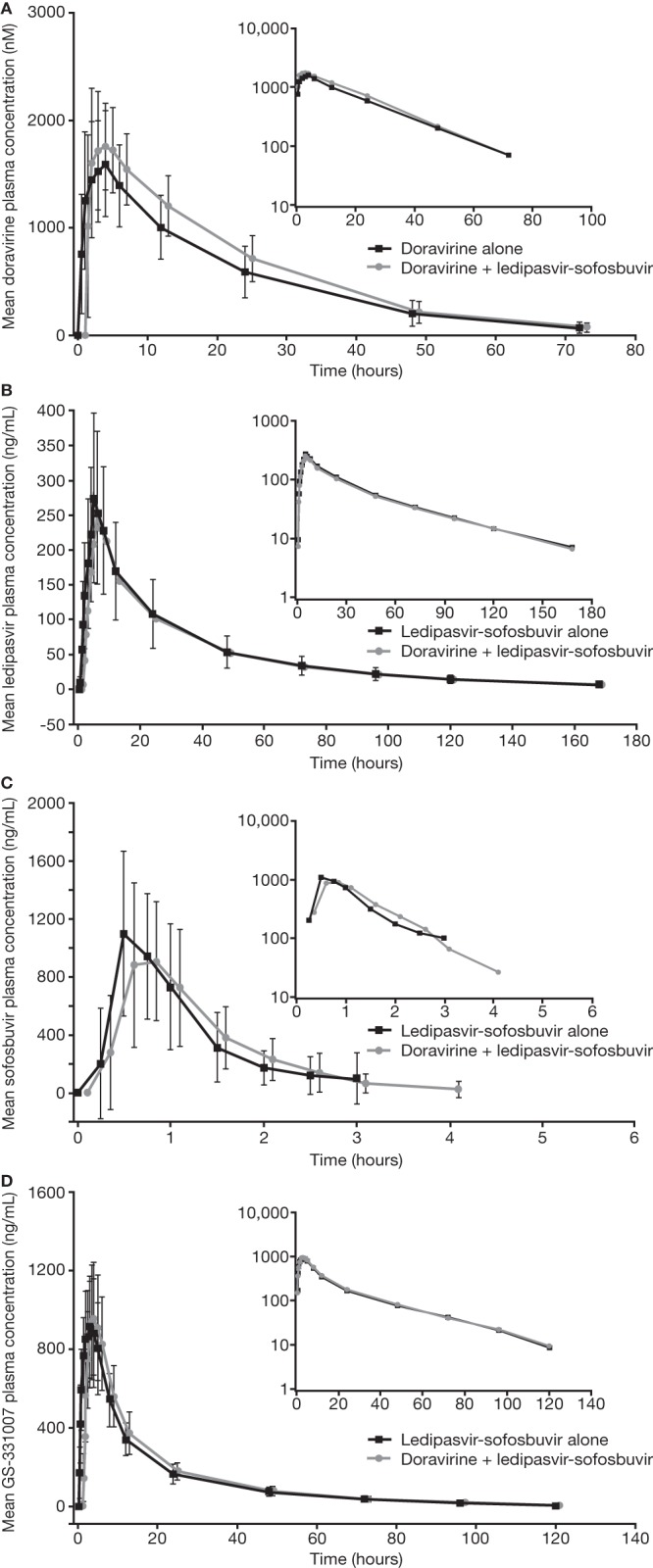

The PK for doravirine, ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, and GS-331007 can be found in Table 3. The mean concentration-time curves are shown in Fig. 2.

TABLE 3.

Trial 2, ledipasvir-sofosbuvir, plasma PKa

| PK parameter | Doravirine alone |

Doravirine + ledipasvir-sofosbuvir |

GMR (doravirine + ledipasvir-sofosbuvir)/doravirine alone (90% CI) | Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir alone |

GMR (doravirine + ledipasvir-sofosbuvir)/(ledipasvir-sofosbuvir alone) (90% CI) | Pseudo-within-participant %CVb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | GM (95% CI) | N | GM (95% CI) | N | GM (95% CI) | ||||

| Doravirine | |||||||||

| AUC0–∞c (μM·h) | 14 | 36.3 (30.2, 43.7) | 14 | 41.8 (36.2, 48.3) | 1.15 (1.07, 1.24) | 11.0 | |||

| Cmaxc (nM) | 14 | 1,670 (1,400, 1,990) | 14 | 1,850 (1,550, 2,210) | 1.11 (0.97, 1.27) | 20.1 | |||

| C24c (nM) | 14 | 550 (438, 690) | 14 | 682 (568, 818) | 1.24 (1.13, 1.36) | 13.9 | |||

| Tmaxd (h) | 14 | 4.00 (1.00, 6.00) | 14 | 3.00 (0.50, 6.00) | |||||

| Apparent terminal t1/2e (h) | 14 | 14.25 (25.6) | 14 | 13.63 (26.8) | |||||

| CL/Fe (liters/h) | 14 | 6.52 (30.8) | 14 | 5.60 (26.4) | |||||

| VZ/Fe (liters) | 14 | 134 (25.0) | 14 | 110 (24.8) | |||||

| Ledipasvir | |||||||||

| AUC0–∞c (ng·h/ml) | 14 | 7,450 (5,470, 10,100) | 14 | 8,080 (6,060, 10,800) | 0.92 (0.80, 1.06) | 20.2 | |||

| Cmaxc (ng/ml) | 14 | 225 (165, 308) | 14 | 248 (182, 339) | 0.91 (0.80, 1.02) | 17.8 | |||

| Tmaxd (h) | 14 | 5.00 (5.00, 6.01) | 14 | 5.00 (5.00, 8.00) | |||||

| Apparent terminal t1/2e (h) | 14 | 41.59 (24.9) | 14 | 41.96 (31.9) | |||||

| CL/Fe (liters/h) | 14 | 12.1 (56.9) | 14 | 11.1 (52.4) | |||||

| VZ/Fe (liters) | 14 | 725 (70.7) | 14 | 674 (72.2) | |||||

| Sofosbuvir | |||||||||

| AUC0–∞c (ng·h/ml) | 14 | 1,170 (949, 1,440) | 14 | 1,130 (886, 1,440) | 1.04 (0.91, 1.18) | 19.1 | |||

| Cmaxc (ng/ml) | 14 | 1,060 (829, 1,350) | 14 | 1,190 (949, 1,500) | 0.89 (0.79, 1.00) | 17.9 | |||

| Tmaxd (h) | 14 | 0.67 (0.51, 2.50) | 14 | 0.50 (0.50, 2.50) | |||||

| Apparent terminal t1/2e (h) | 14 | 0.49 (35.9) | 14 | 0.49 (51.1) | |||||

| CL/Fe (liters/h) | 14 | 342 (37.1) | 14 | 354 (42.8) | |||||

| VZ/Fe (liters) | 14 | 242 (46.8) | 14 | 251 (80.0) | |||||

| GS-331007 | |||||||||

| AUC0–∞c (ng·h/ml) | 14 | 16,400 (14,400, 18,600) | 14 | 15,800 (13,900, 18,000) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 7.4 | |||

| Cmaxc (ng/ml) | 14 | 1,010 (877, 1,160) | 14 | 981 (866, 1,110) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) | 8.8 | |||

| Tmaxd (h) | 14 | 2.75 (1.01, 5.00) | 14 | 2.76 (1.00, 4.03) | |||||

| Apparent terminal t1/2e (h) | 14 | 27.40 (15.6) | 14 | 27.67 (18.8) | |||||

Plasma PK for doravirine, ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, and GS-331007 following single-dose administration of 100 mg doravirine alone, 90 mg ledipasvir and 400 mg sofosbuvir alone, and coadministered 100 mg doravirine + 90 mg ledipasvir and 400 mg sofosbuvir in healthy adults. Doravirine alone, a single oral dose of 100 mg doravirine. Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir alone, a single oral dose of 90 mg ledipasvir and 400 mg sofosbuvir. Doravirine + ledipasvir-sofosbuvir, coadministration of a single oral dose of 100 mg doravirine and a single oral dose of 90 mg ledipasvir and 400 mg sofosbuvir. Abbreviations: %CV, percent coefficient of variation; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; CL/F, apparent clearance after extravascular administration; Cmax, maximum concentration; C24, plasma concentration 24 h postdose; GM, geometric least-square mean; GMR, geometric least-square mean ratio; N, number of participants; PK, pharmacokinetics; Tmax, time of maximum plasma concentration; t1/2, apparent terminal half-life; VZ/F, apparent volume of distribution during the apparent terminal phase after extravascular administration.

Pseudo within-participant %CV = 100 × sqrt[(σa2 + σb2 – 2σab)/2], where σa2 and σb2 are the estimated variances on the log scale for the two treatment groups, and σab is the corresponding estimated covariance, each obtained from the linear mixed-effects model.

Back-transformed least-square mean and CI from the linear mixed-effect model performed on natural log-transformed values.

Median (minimum, maximum) values are reported for Tmax.

Geometric mean and geometric percent coefficient of variation reported for apparent terminal half-life, CL/F, and VZ/F.

FIG 2.

Trial 2, ledipasvir-sofosbuvir, mean concentration-time profiles for doravirine, ledipasvir, and sofosbuvir. (A) Arithmetic mean (± standard deviation [SD]) doravirine plasma concentration-time profiles following the administration of a single oral dose of 100 mg doravirine with and without the coadministration of a single oral dose of 90 mg ledipasvir and 400 mg sofosbuvir in healthy adults (N = 14). (B to D) Arithmetic mean (±SD) ledipasvir (B), sofosbuvir (C), and GS-331007 (D) plasma concentration-time profiles following the administration of a single oral dose of 90 mg ledipasvir with 400 mg sofosbuvir with and without the coadministration of a single oral dose of 100 mg doravirine in healthy adults (all N = 14). Main panels, linear scale; insets, semilog scale. Doravirine + ledipasvir-sofosbuvir linear profiles are shifted to the right for ease of reading.

Doravirine AUC0–∞, Cmax, and C24 increased slightly following coadministration with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir compared to that with doravirine alone. GMRs (90% CI) for (doravirine + ledipasvir-sofosbuvir)/doravirine were 1.15 (1.07, 1.24), 1.11 (0.97, 1.27), and 1.24 (1.13, 1.36), respectively. Doravirine median Tmax decreased by 1 to 3 h with coadministration, and apparent terminal half-life (t1/2) was similar for coadministration and doravirine alone.

The PK of ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, and GS-331007 during coadministration of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir with doravirine were similar to those of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir alone (Table 3).

(iii) Safety.

The single oral doses of doravirine, ledipasvir-sofosbuvir, and their coadministration were generally well tolerated. Six participants (43%) reported a total of 13 AEs after initiation of the study drug(s), none of which were reported by more than one participant. Two participants (14%) reported AEs that were deemed to be drug related by the investigator. One participant reported somnolence following administration of doravirine alone and after administration of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir + doravirine. One participant reported headache following administration of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir + doravirine. There were no SAEs or deaths during the trial, and there were no discontinuations due to an AE. All reported AEs were mild in nature and resolved by the end of the trial. There were no clinically meaningful changes in laboratory tests, vital signs, or ECGs.

DISCUSSION

Given the high rate of HIV-HCV coinfection, it is anticipated that doravirine may be coadministered with HCV antiviral regimens. Since medications to treat HIV and HCV infections may give rise to clinically significant DDIs, it is important to evaluate the potential for such interactions prior to coadministration in coinfected individuals. The results of the two studies reported here support the coadministration of 100 mg of doravirine with the HCV antiviral regimens elbasvir-grazoprevir and ledipasvir-sofosbuvir at their therapeutic doses.

In trial 1 (elbasvir + grazoprevir), a multiple-dose trial design was used, as single-dose PK of grazoprevir are not entirely predictive of steady-state PK (22). In trial 2 (ledipasvir-sofosbuvir), a single-dose design was used, as PK following single doses and in healthy adults are considered predictive of steady-state PK in patients for all three drugs (10, 19, 20, 23).

Doravirine did not have a clinically relevant effect on the PK of elbasvir, grazoprevir, ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, or its metabolite, GS-331007. Although both HCV regimens modestly increased the exposure of doravirine, the increase was not expected to be clinically meaningful. The coadministration of doravirine and elbasvir + grazoprevir led to modest increases in doravirine AUC0–24, Cmax, and C24 of 56%, 41%, and 61%, respectively, while coadministration of doravirine and ledipasvir-sofosbuvir led to small increases in doravirine AUC0–∞, Cmax, and C24 of 15%, 11%, and 24%, respectively. The magnitude of the increases in doravirine AUC0–24 and Cmax were within the range of exposures shown to be generally well tolerated in clinical assessment, including at 200 mg QD, where exposures are nearly 2-fold those of the clinical dose of 100 mg QD, in a phase 2 trial of doravirine in combination with emtricitabine-tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for 24 weeks (24). Furthermore, the doravirine prescribing information does not indicate the need for any dose adjustment of doravirine when coadministered with a strong CYP3A inhibitor, which may increase doravirine exposure by 3-fold (3). Therefore, the increases in doravirine exposure seen in the current trial are not thought to be clinically meaningful.

The mechanism of the increase in doravirine PK following coadministration with elbasvir + grazoprevir may be through inhibition of CYP3A, likely due to grazoprevir. Grazoprevir is a weak CYP3A inhibitor (14), while data suggest that elbasvir is not a CYP3A inhibitor (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50] of >100 μM) (14). In DDI trials of grazoprevir with midazolam and tacrolimus, both CYP3A substrates (14, 25), grazoprevir increased the AUC of midazolam by approximately 30% (14), and coadministration with elbasvir-grazoprevir increased the AUC of tacrolimus by approximately 40% (26), which is comparable with the effect of grazoprevir on doravirine. Elbasvir inhibited P-gp in vitro but did not have a clinically meaningful effect on the PK of digoxin (14). Thus, inhibition of P-gp by elbasvir is unlikely to be the mechanism involved in the modest increase in doravirine exposure. Given that the current trial was a multiple-dose trial, the effect of elbasvir and grazoprevir on doravirine t1/2 could not be ascertained.

The mechanism of the small increase in doravirine PK following coadministration with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir may involve inhibition of P-gp. Doravirine is a P-gp substrate; however, P-gp does not appear to have a major role in its elimination and is not expected to limit its absorption (6). Coadministration of doravirine with single-dose rifampin, known to inhibit P-gp and CYP3A, led to only a modest increase (40%) in Cmax, as expected due to the high permeability of doravirine (8). Meanwhile, drug interaction studies of doravirine with multiple doses of ritonavir (7) or ketoconazole (7) (also P-gp and CYP3A inhibitors) showed a more substantial increase in AUC and C24 compared with Cmax, supporting that systemic inhibition of CYP3A plays a more significant role than inhibition of P-gp. Ledipasvir has been shown to be a P-gp inhibitor (19). However, as doravirine has good permeability, the effect of P-gp inhibition on absorption would not be expected to be substantial, consistent with the small increases in doravirine exposure observed in the current trial.

Given the in vitro and in vivo DDI profile of doravirine, the 100-mg dose studied here was not expected to meaningfully alter the exposures of elbasvir, grazoprevir, ledipasvir, and sofosbuvir or its metabolite, GS-331007. The most likely mechanism of interaction would be anticipated to be through inhibition of intestinal BCRP only, as doravirine is a weak inhibitor of BCRP in vitro. At a supratherapeutic dose of 200 mg, doravirine was shown in a clinical DDI trial to modestly increase the Cmax and AUC values of dolutegravir (∼30 to 40% increase) (27), a BCRP substrate. However, doravirine at a 100-mg dose did not increase the Cmax or AUC of atorvastatin, the elimination of which is partially mediated by BCRP (28). While the potential for grazoprevir to be a BCRP substrate cannot be excluded (17) and GS-331007 is not a BCRP substrate (19), ledipasvir and sofosbuvir are both substrates of BCRP (19). In the studies reported here, coadministration of doravirine with elbasvir + grazoprevir and with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir had little to no effect on the exposures of the studied HCV medications. Although the Cmax of grazoprevir was modestly increased (22%) in the presence of doravirine, this increase was well within the range of clinical exposures determined to be well tolerated in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials (17). These results also support that doravirine is not a clinically meaningful inhibitor of OATP1B, as indicated by an in vitro study (9).

It is also anticipated that doravirine will have limited interactions with other anti-HCV treatment combinations, including fixed-dose glecaprevir-pibrentasvir, sofosbuvir-velpatasvir, and sofosbuvir-velpatasvir-voxilaprevir. Glecaprevir and pibrentasvir are weak inhibitors of CYP3A (29); based on the results of the study with grazoprevir, also a weak CYP3A inhibitor, glecaprevir-pibrentasvir would not be expected to cause a clinically meaningful increase in doravirine exposure. Although glecaprevir, pibrentasvir, sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir are all inhibitors of P-gp (29, 30), clinical DDI data indicate that P-gp inhibitors are unlikely to have a clinically meaningful effect on doravirine (7, 8). Like ledipasvir and sofosbuvir, glecaprevir, pibrentasvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir are BCRP substrates (29, 30). Given the lack of effect of doravirine on ledipasvir or sofosbuvir and the results of a study with dolutegravir (27), also a BCRP substrate, doravirine is not expected to have a clinically meaningful effect on these other HCV drugs. Velpatasvir and voxilaprevir are substrates of CYP3A (30); however, previous clinical trials have indicated that doravirine does not have a clinically relevant impact on the PK of CYP3A substrates such as midazolam (10) or atorvastatin (28) and hence would not be anticipated to have an impact on velpatasvir or voxilaprevir.

The coadministration of doravirine with the studied HCV medications was generally well tolerated in healthy participants, and the safety data support the coadministration of doravirine with elbasvir-grazoprevir or ledipasvir-sofosbuvir. There was no clear difference in the occurrence of AEs when trial drugs were administered alone compared with those in combination. No clinically meaningful changes were observed in clinical laboratory values, vital signs, or ECG safety parameter values. A pregnancy was reported in trial 1; the outcome of the pregnancy was spontaneous abortion, which was classified as an SAE. Since the cause of the spontaneous abortion could not be identified, and because the participant was pregnant throughout dosing with all three study medications, a causative relationship to study medication could not be ruled out.

Conclusions.

No clinically relevant PK changes were observed during the coadministration of doravirine with HCV regimens of elbasvir + grazoprevir or ledipasvir-sofosbuvir. The lack of a meaningful impact on PK following coadministration of doravirine and elbasvir + grazoprevir or ledipasvir-sofosbuvir suggests that doravirine can be coadministered with elbasvir-grazoprevir or ledipasvir-sofosbuvir without any need for dose adjustment. Given the high prevalence of HCV coinfection in individuals with HIV-1, a lack of DDIs between doravirine and elbasvir-grazoprevir or ledipasvir-sofosbuvir offers a valuable HIV-1 anchor that is compatible with these two HCV combination therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DDIs between doravirine and two HCV medications were studied in two phase 1, open-label, PK drug interaction studies. Trial 1 (elbasvir + grazoprevir [protocol MK-1439-050]) was a nonrandomized, three-period, fixed-sequence, multiple-dose trial, conducted between 14 April and 2 June 2016. Trial 2 (ledipasvir-sofosbuvir [protocol MK-1439-053]) was a randomized, three-period, crossover, single-dose trial, conducted between 6 July and 9 September 2016. Both trials were approved by an institutional review board (Chesapeake IRB, Columbia, MD, USA) and were performed in accordance with Good Clinical Practice. All participants provided written, informed consent.

Trial population and procedures. (i) Trial 1, elbasvir + grazoprevir.

Healthy men and women aged between 19 and 55 years with a body mass index (BMI) of ≥18.5 to ≤32.0 kg/m2 were eligible for enrollment. Women of childbearing potential were required to use appropriate contraception. Individuals who tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen, HCV antibodies, or HIV were excluded. In period 1, participants received 100 mg doravirine QD on days 1 to 5, followed by a washout period of at least 5 days. In period 2, participants received 50 mg elbasvir and 200 mg grazoprevir (100 mg two times) coadministered QD on days 1 to 10. In period 3, which began the day after day 10 of period 2, 100 mg doravirine, 50 mg elbasvir, and 200 mg grazoprevir were coadministered QD on days 1 to 5. Because grazoprevir exhibits approximately 2-fold higher exposures in HCV-infected individuals than healthy individuals (22), the trial was conducted with 50 mg of elbasvir and 200 mg of grazoprevir (elbasvir + grazoprevir) rather than the fixed-dose combination of 50 mg elbasvir and 100 mg grazoprevir (elbasvir-grazoprevir) to better replicate exposures achieved in HCV-infected individuals. In addition, due to nonlinearity in the PK of grazoprevir with time (22) and a small but clinically irrelevant effect of food (14), the DDI assessment was conducted at steady state and all trial drugs were administered after a moderate-fat breakfast, which was consumed after a fast of ≥8 h.

Blood for doravirine plasma concentration analysis was collected on day 5 of periods 1 and 3 at the following time points: predose and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h postdose. Blood for elbasvir and grazoprevir plasma analysis was collected on day 10 of period 2 and day 5 of period 3 at the following time points: predose and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 16, and 24 h postdose.

Safety and tolerability was assessed via AEs, physical examination, vital signs, and laboratory safety tests.

(ii) Trial 2, ledipasvir-sofosbuvir.

Healthy men and women aged between 19 and 64 years with a BMI of ≥18.5 to ≤32.0 kg/m2 were eligible for enrollment. Women of childbearing potential were required to use appropriate contraception. Individuals who tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen, HCV antibodies, or HIV were excluded. In each of the three periods, participants received a single dose of either 100 mg doravirine alone, 90 mg ledipasvir with 400 mg sofosbuvir alone, or doravirine coadministered with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir in a randomized manner. The therapeutically indicated dose of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir and the intended clinical dose of doravirine were used in the trial. There was a washout of 14 days between the dosing of each treatment period. All trial drugs were administered in a fasted state to reduce potential PK variability related to food.

Blood samples for doravirine plasma concentration analysis were collected predose and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h postdose; samples for ledipasvir plasma concentration analysis were collected predose and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, and 168 h postdose; and samples for sofosbuvir and GS-331007 plasma concentration analysis were collected predose and at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h postdose.

Bioanalysis.

All bioanalysis was conducted by inVentiv Health Clinique (Quebec, QC, Canada).

(i) Doravirine, grazoprevir, and elbasvir.

The analytical methods for doravirine, grazoprevir, and elbasvir are based on an automated liquid-liquid extraction from human plasma with dipotassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (K2EDTA) anticoagulant. The analytes and stable-labeled internal standards were assayed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) detection. A calibration curve range of 1.00 to 1,000 ng/ml with a lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) of 1.00 ng/ml was used for doravirine and grazoprevir, and a curve range of 0.25 to 250 ng/ml with an LLOQ of 0.25 ng/ml was used for elbasvir. Interday precision and accuracy assessments were perfomed on quality control (QC) samples. The mean accuracy of study QCs were within 2.53%, 2.36%, and 4.40% of nominal values for doravirine, grazoprevir, and elbasvir, respectively. Assay precision ranged from 1.65 to 6.28% coefficient of variation (CV) for doravirine, from 1.50 to 4.11% CV for grazoprevir, and from 1.34 to 3.55% CV for elbasvir.

(ii) Ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, and GS-331007.

The analytical methods for ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, and GS-331007 are based on an automated protein precipitation extraction from human plasma with K2EDTA anticoagulant. Ledipasvir and its stable-label internal standard, 13C2-D6, and sofosbuvir and GS-331007 with their internal standard, zidovudine, were assayed by HPLC with MS/MS detection. A calibration curve range of 1.00 to 1,000 ng/ml with an LLOQ of 1.00 was used for ledipasvir, a calibration curve range of 10.00 to 2,040 ng/ml with an LLOQ of 10.00 ng/ml was used for sofosbuvir, and a curve range of 10.00 to 3,000 ng/ml with an LLOQ of 10.00 ng/ml was used for GS-331007. Between-run precision and accuracy assessments were performed on QC samples. The mean accuracy of study QCs were within 3.89%, 1.98%, and 3.03% of nominal values for ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, and GS-331007, respectively. Assay precision ranged from 2.13 to 3.98% CV for ledipasvir, 3.64 to 3.78% CV for sofosbuvir, and 4.11 to 6.30% CV for GS-331007.

PK evaluations and data analysis. (i) Trial 1, elbasvir + grazoprevir.

AUC0–24, Cmax, C24, and Tmax were estimated for doravirine, elbasvir, and grazoprevir. PK values were calculated using Phoenix WinNonlin, version 6.3 (Certara L.P. [Pharsight], St. Louis, MO). Cmax, Tmax, and C24 were generated from the plasma concentration-time data. AUC0–24 was calculated using the linear-trapezoidal method for ascending concentrations and the log-trapezoidal method for descending concentrations up to the last detectable plasma concentration or the nominal sampling times at 24 h postdose for AUC0–24 (linear up/log down). AUC0–24, Cmax, and C24 were natural-log (ln) transformed and evaluated with a linear mixed-effects model with fixed-effect terms for treatment. An unstructured covariance matrix was used to allow for unequal treatment variances and to model the correlation between the treatment measurements within each participant via the REPEATED statement in SAS PROC MIXED. The Kenward-Roger adjustment method was used to calculate the denominator degrees of freedom for the fixed effects.

The effect of elbasvir and grazoprevir on doravirine PK was determined by estimation of the true GMRs ([doravirine + elbasvir + grazoprevir]/[doravirine alone]) for doravirine AUC0-24, Cmax, and C24. Similarly, the effect of doravirine on elbasvir and grazoprevir PK was determined by estimating the true GMRs ([doravirine + elbasvir + grazoprevir]/[elbasvir + grazoprevir alone]) for elbasvir and grazoprevir AUC0–24, Cmax, and C24.

(ii) Trial 2, ledipasvir-sofosbuvir.

AUC0–∞, Cmax, Tmax, and the apparent terminal t1/2 were estimated for doravirine, ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, and GS-331007. Additionally, apparent clearance after extravascular administration (CL/F) and apparent volume of distribution during the apparent terminal phase after extravascular administration (VZ/F) were estimated for doravirine, ledipasvir, and sofosbuvir, and C24 was measured for doravirine. PK values were estimated using Phoenix WinNonlin, version 6.3 (Certara L.P. [Pharsight], St. Louis, MO). Cmax, C24, and Tmax values were obtained directly from the plasma concentration-time data. AUC0-∞ was calculated using the linear-trapezoidal method for ascending concentrations and the log-trapezoidal method for descending concentrations (linear up/log down). AUC0–∞ was calculated as the sum of AUC from time zero to the time of the last measurable concentration and Cest,last/λz, where Cest,last was the estimated last measurable concentration and λz was the apparent first-order terminal elimination rate constant calculated from the slope of the linear regression of the terminal log-linear portion of the concentration-time profile. The apparent terminal t1/2 was calculated as the quotient of the ln of 2 and λz (ln[2]/λz). CL/F was calculated as dose/AUC0–∞. VZ/F was calculated as dose/(AUC0–∞ × λz). PK values for AUC0–∞, Cmax, and C24 (C24 for doravirine only) were ln transformed and evaluated with a linear mixed-effects model with fixed-effect terms for treatment and period. An unstructured covariance matrix was used to allow for unequal treatment variances and to model the correlation between the treatment measurements within each participant via the REPEATED statement in SAS PROC MIXED. The Kenward-Roger adjustment method was used to calculate the denominator degrees of freedom for the fixed effects.

The effect of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir on doravirine PK was determined by estimation of the true GMRs ([ledipasvir-sofosbuvir + doravirine]/[doravirine alone]) for doravirine AUC0–∞, Cmax, and C24. Similarly, the effect of doravirine on ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, and GS-331007 PK was determined by estimating the true GMRs ([ledipasvir-sofosbuvir + doravirine]/[ledipasvir-sofosbuvir alone]) for ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, and GS-331007 AUC0–∞ and Cmax.

One participant did not provide a 96-h blood sample in period 2 (ledipasvir-sofosbuvir alone). The impact of this missing concentration data was deemed insignificant, and available data for this participant were included for PK analysis. Two participants had a ledipasvir measurable predose concentration value in period 3 (ledipasvir-sofosbuvir + doravirine) following dosing in period 2 (ledipasvir-sofosbuvir alone). These predose concentrations were <5% (1% and 0.4%, respectively) of their respective period 3 Cmax values. This level of carryover was considered negligible, and no corrections were applied.

Safety assessments.

In both trials, safety was monitored via reports of AEs, physical examinations, monitoring of vital signs, ECGs, and laboratory safety tests throughout the trials. The investigator assessed whether or not an AE was considered related to drug based in part on expected AEs with the agents being dosed, temporal relationship to dosing, and lack of other identified medical causes of an AE.

Data availability.

Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA’s data sharing policy, including restrictions, is available at http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php. Requests for access to the clinical study data can be submitted through the EngageZone site or via email to dataaccess@merck.com.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the trial staff and participants and Robert Valesky for oversight of the bioanalytical work. Medical writing assistance, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Kirsty Muirhead, of CMC AFFINITY, a division of McCann Health Medical Communications, Ltd., Glasgow, UK, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines. This assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Authors made the following contributions: conception, design or planning of study, W.A., L.F., S.K., S.A.S., R.I.S., I.T., D.W., and K.L.Y.; acquisition of data, S.A.S., L.M.S., and D.W.; analysis of data, W.A., L.F., P.M., and K.L.Y.; interpretation of results, W.A., L.F., S.K., M.I., P.M., R.I.S., and K.L.Y. All authors contributed to drafting, critically reviewing, and revising the manuscript.

Funding for this research was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme, Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. W.A., R.I.S., K.L.Y., L.F., P.M., D.W., I.T., S.A.S., M.I., and S.K. are current or former employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme, Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA, and may own stock and/or stock options in Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. L.M.S. has no disclosures to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Molina JM, Squires K, Sax PE, Cahn P, Lombaard J, DeJesus E, Lai M-T, Xu X, Rodgers A, Lupinacci L, Kumar S, Sklar P, Nguyen BY, Hanna GJ, Hwang C, DRIVE-FORWARD Study Group. 2018. Doravirine versus ritonavir-boosted darunavir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 (DRIVE-FORWARD): 48-week results of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV 5:e211–e220. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orkin C, Squires KE, Molina JM, Sax PE, Wong WW, Sussmann O, Kaplan R, Lupinacci L, Rodgers A, Xu X, Lin G, Kumar S, Sklar P, Nguyen BY, Hanna GJ, Hwang C, Martin EA, DRIVE-AHEAD Study Group. 2019. Doravirine/lamivudine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is non-inferior to efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in treatment-naive adults with human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection: week 48 results of the DRIVE-AHEAD trial. Clin Infect Dis 68:535–544. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. 2018. Pifeltro (doravirine) prescribing information. Merck & Co., Inc, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA: https://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/p/pifeltro/pifeltro_pi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. 2018. Delstrigo (doravirine, lamivudine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) prescribing information. Merck & Co., Inc, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA: https://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/d/delstrigo/delstrigo_pi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng M, Sachs NA, Xu M, Grobler J, Blair W, Hazuda DJ, Miller MD, Lai M-T. 2016. Doravirine suppresses common nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-associated mutants at clinically relevant concentrations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:2241–2247. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02650-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez RI, Fillgrove KL, Yee KL, Liang Y, Lu B, Tatavarti A, Liu R, Anderson MS, Behm MO, Fan L, Li Y, Butterton JR, Iwamoto M, Khalilieh SG. 2019. Characterisation of the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and mass balance of doravirine, a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor in humans. Xenobiotica 49:422–432. doi: 10.1080/00498254.2018.1451667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalilieh SG, Yee KL, Sanchez RI, Fan L, Anderson MS, Sura M, Laethem T, Rasmussen S, van Bortel L, van Lancker G, Iwamoto M. 2019. Doravirine and the potential for CYP3A-mediated drug-drug interactions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e02016-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02016-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yee KL, Khalilieh SG, Sanchez RI, Liu R, Anderson MS, Manthos H, Judge T, Brejda J, Butterton JR. 2017. The effect of single and multiple doses of rifampin on the pharmacokinetics of doravirine in healthy subjects. Clin Drug Investig 37:659–667. doi: 10.1007/s40261-017-0513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleasby K, Fillgrove KL, Houle R, Lu B, Palamanda J, Newton DJ, Lin M, Chan GH, Sanchez RI. 2019. In vitro evaluation of the drug interaction potential of doravirine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e02492-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02492-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson MS, Gilmartin J, Cilissen C, De Lepeleire I, van Bortel L, Dockendorf MF, Tetteh E, Ancona JK, Liu R, Guo Y, Wagner JA, Butterton JR. 2015. Safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of doravirine, a novel HIV non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, after single and multiple doses in healthy subjects. Antivir Ther 20:397–405. doi: 10.3851/IMP2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Platt L, Easterbrook P, Gower E, McDonald B, Sabin K, McGowan C, Yanny I, Razavi H, Vickerman P. 2016. Prevalence and burden of HCV co-infection in people living with HIV: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 16:797–808. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez MD, Sherman KE. 2011. HIV/hepatitis C coinfection natural history and disease progression. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 6:478–482. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32834bd365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotman Y, Liang TJ. 2009. Coinfection with hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus: virological, immunological, and clinical outcomes. J Virol 83:7366–7374. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00191-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. 2017. ZEPATIER (elbasvir-grazoprevir) prescribing information. Merck & Co., Inc, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA: http://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/z/zepatier/zepatier_pi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeuzem S, Ghalib R, Reddy KR, Pockros PJ, Ben Ari Z, Zhao Y, Brown DD, Wan S, DiNubile MJ, Nguyen BY, Robertson MN, Wahl J, Barr E, Butterton JR. 2015. Grazoprevir-elbasvir combination therapy for treatment-naive cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1, 4, or 6 infection: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 163:1–13. doi: 10.7326/M15-0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rockstroh JK, Nelson M, Katlama C, Lalezari J, Mallolas J, Bloch M, Matthews GV, Saag MS, Zamor PJ, Orkin C, Gress J, Klopfer S, Shaughnessy M, Wahl J, Nguyen B-Y, Barr E, Platt HL, Robertson MN, Sulkowski M. 2015. Efficacy and safety of grazoprevir (MK-5172) and elbasvir (MK-8742) in patients with hepatitis C virus and HIV co-infection (C-EDGE CO-INFECTION): a non-randomised, open-label trial. Lancet HIV 2:e319–e327. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd. 2018. Zepatier 50 mg/100 mg film coated tablets SmPC. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4422/smpc. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caro L, Talaty JE, Guo Z, Reitmann C, Fraser IP, Evers R, Swearingen D, Yeh WW, Butterton JR. 2013. Pharmacokinetic interaction between the HCV protease inhibitor MK‐5172 and midazolam, pitavastatin, and atorvastatin in healthy volunteers. Abstr 64th Annu Meet Am Assoc Study Liver Dis. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilead Sciences Inc. 2017. HARVONI (ledipasvir-sofosbuvir) prescribing information. http://www.gilead.com/~/media/files/pdfs/medicines/liver-disease/harvoni/harvoni_pi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2014. FDA clinical pharmacology review of Harvoni. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/205834Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf.

- 21.Kirby BJ, Symonds WT, Kearney BP, Mathias AA. 2015. Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and drug-interaction profile of the hepatitis C virus NS5B polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir. Clin Pharmacokinet 54:677–690. doi: 10.1007/s40262-015-0261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caro L, Anderson M, Du L, Palcza J, Han L, Van Dyck K, Robberechts M, De Lepeleire I, Petry A, Young MB, Fraser I, O'Mara E, Moiseev V, Kobalava Z, Uhle M, Wagner F. 2011. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship for MK-5172, a novel hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3/4A protease inhibitor, in genotype 1 and genotype 3 HCV-infected patients. Abstr 62nd Annu Meet Am Assoc Study Liver Dis. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schürmann D, Sobotha C, Gilmartin J, Robberechts M, De Lepeleire I, Yee KL, Guo Y, Liu R, Wagner F, Wagner JA, Butterton JR, Anderson MS. 2016. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, short-term monotherapy study of doravirine in treatment-naive HIV-infected individuals. AIDS 30:57–63. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morales-Ramirez JO, Gatell JM, Hagins DP, Thompson M, Arasteh K, Hoffmann C, Harvey C, Xu X, Teppler H. 2014. Safety and antiviral effect of MK-1439, a novel NNRTI (+FTC/TDF) in ART-naive HIV-infected patients. Abstr Conf Retrovir Opportun Infect, abstr 92LB. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lampen A, Christians U, Guengerich FP, Watkins PB, Kolars JC, Bader A, Gonschior AK, Dralle H, Hackbarth I, Sewing KF. 1995. Metabolism of the immunosuppressant tacrolimus in the small intestine: cytochrome P450, drug interactions, and interindividual variability. Drug Metab Dispos 23:1315–1324. http://dmd.aspetjournals.org/content/23/12/1315.long. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng HP, Caro L, Fandozzi CM, Guo Z, Talaty J, Wolford D, Panebianco D, Iwamoto M, Butterton JR, Yeh WW. 2018. Pharmacokinetic interactions between elbasvir-grazoprevir and immunosuppressant drugs in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 58:666–673. doi: 10.1002/jcph.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson MS, Khalilieh S, Yee KL, Liu R, Fan L, Rizk ML, Shah V, Hussaini A, Song I, Ross LL, Butterton JR. 2017. A two-way steady-state pharmacokinetic interaction study of doravirine (MK-1439) and dolutegravir. Clin Pharmacokinet 56:661–669. doi: 10.1007/s40262-016-0458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khalilieh S, Yee KL, Sanchez RI, Triantafyllou I, Fan L, Maklad N, Jordan H, Martell M, Iwamoto M. 2017. Results of a doravirine-atorvastatin drug-drug interaction study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01364-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01364-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.AbbVie Inc. 2018. Mavyret (glecaprevir and pibrentasvir) prescribing information. https://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/mavyret_pi.pdf.

- 30.Gilead Sciences Inc. 2017. Vosevi (sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir) prescribing information. http://www.gilead.com/-/media/a25fc64c75fb4704947d80c0f7390425.ashx.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA’s data sharing policy, including restrictions, is available at http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php. Requests for access to the clinical study data can be submitted through the EngageZone site or via email to dataaccess@merck.com.