Abstract

Autophagy is a highly conserved lysosomal degradation process which can recycle unnecessary or dysfunctional cell organelles and proteins, thereby playing a crucial regulatory role in cell survival and maintenance. It has been widely accepted that autophagy regulates various pathological processes, among which cancer attracts much attention. Autophagy may either promote cancer cell survival by providing energy during unfavourable metabolic circumstance or can induce individual cancer cell death by preventing necrosis and increasing genetic instability. Thus, dual roles of autophagy may determine the destiny of cancer cells and make it an attractive target for small‐molecule drug discovery. Collectively, key autophagy‐related elements as potential targets, oncogenes mTORC1, class I PI3K and AKT, as well as tumour suppressor class III PI3K, Beclin‐1 and p53, have been discussed. In addition, some small molecule drugs, such as rapamycin and its derivatives, rottlerin, PP242 and AZD8055 (targeting PI3K/AKT/mTORC1), spautin‐1, and tamoxifen, as well as oridonin and metformin (targeting p53), can modulate autophagic pathways in different types of cancer. All these data will shed new light on targeting the autophagic process for cancer therapy, using small‐molecule compounds, to fight cancer in the near future.

Introduction

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved, multi‐step lysosomal process, in which cellular materials are delivered to lysosomes for degradation and recycling 1. At least three forms of autophagy have been identified: macroautophagy, chaperone‐mediated autophagy and microautophagy, which are different in physiological functions and modes of cargo delivery to the lysosome 2. Among them, macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is the major regulated catabolic mechanism by which an autophagosome sequesters cytoplasm then fuses with a lysosome for degradation 3. It has been demonstrated that autophagy is modulated by a limited number of AuTophaGy‐related genes (ATGs) 4.

Cancer is a multi‐step process caused by genetic alterations involving mutations of oncogenes or tumour suppressors which drives progressive transformation of normal cells to malignancy 5. On the one hand, autophagy can help in cell maintenance by specifically degrading damaged or superfluous organelles; in this context it can be regarded as a powerful promoter of metabolic homeostasis 6. On the other hand, an opposing role of autophagy has been discovered, since it can promote cell death in cancer, which helps classify autophagy as type II programmed cell death (PCD) 7. Different oncogenic pathways, including Bcl‐2, mTOR, class I phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase (PI3KCI), AKT and MAPKs, or tumour suppressive pathways, such as PI3KCIII, Beclin‐1, Bif‐1, UVRAG, DAPKs, PTEN and p53, have distinct influence on various types of cancer 8. Thus, autophagy may either promote cancer cell survival or induce cancer cell death under different conditions.

Since a number of small molecule compounds have been found to target key regulatory autophagy‐related components, and regarding their great potential in affecting malignancy, they have received considerable attention. For example, drugs, including rapamycin and its derivatives, rottlerin, PP242 and AZD8055, target the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway to induce autophagy, while other agents such as spautin‐1 and tamoxifen effect their function by regulating Beclin‐1 activity in autophagy. In addition, drugs such as oridonin and metformin may induce cell death via p53‐mediated autophagy. Thus, small molecule compounds can target oncogenic or tumour suppressive autophagic pathways in different types of cancer, which may shed new light on finding novel and potential drugs for future cancer therapeutics.

The machinery of autophagy

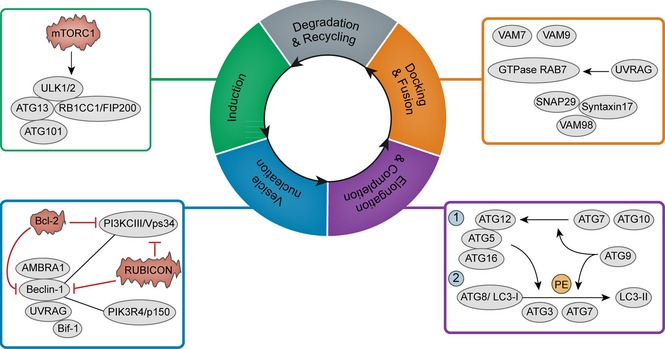

To the best of our knowledge, the autophagic process can be dissected into five different steps: induction, nucleation, elongation & completion, docking & fusion and degradation & recycling 9.

Induction of autophagosome formation is modulated by the complex comprised of Unc51‐like kinase 1/2 (ULK1/2), the mammalian homolog of ATG13 (mATG13) and RB1‐inducible coiled‐coil 1/focal adhesion kinase family interacting protein of 200 kD (RB1CC1/FIP200) 10, 11. Directly binding to ATG13, C12orf44/ATG101 is also essential for the induction process 12. The mammalian ortholog of the yeast protein kinase TOR (mTORC1) is influenced by different nutrient levels 13. When mTORC1 is associated with the complex, it phosphorylates and subsequently inactivates ULK1/2 and mATG13; however, when mTORC1 dissociates from the complex, it results in induction of autophagy 13.

Vesicle nucleation proceeds, which requires ATG14‐containing PI3KCIII complex, containing Beclin‐1, PI3KCIII/VPS34, and PIK3R4/p150. Anti‐apoptotic protein Bcl‐2 may bind to Beclin‐1 and prevent its interaction with PI3KCIII 14. RUBICON, a Beclin‐1‐binding protein, inhibits PI3KCIII activity in the UVRAG‐associated Beclin‐1 complex 15. A further two positive regulators of the complex are AMBRA1 which directly binds to Beclin‐1, and Bif‐1 which can interact with Beclin‐1 through UVRAG 16, 17.

The process of elongation & completion calls for two ubiquitin‐like pathways. First is the ATG12‐ATG5‐ATG16 complex, of which ATG12 is catalyzed by ATG7 and ATG10, and is then fused with ATG5 18. In conjunction with ATG12‐ATG5, ATG16L leads the complex to the autophagic isolation membrane 19. The second is the ATG8/LC3 system, in which the ATG4‐processed form of LC3 is regarded as LC3‐I and PE‐conjugated form is called LC3‐II 22. Transmembrane protein ATG9 also functions in elongation, whose mechanism is not yet clearly understood 23. Once autophagosome expansion is completed, LC3 detaches from LC3‐II, and then is released into the cytosol 24.

Fusion of autophagosomes with endosomes may involve protein components from SNARE machinery, such as VAM7 and VAM9, while UVRAG can also activate the GTPase RAB7, thus promoting fusion with lysosomes 25, 26. A further component of SNARE, syntaxin 17, interacts with SNAP29 and endosomal/lysosomal SNARE VAMP8 27.

Degradation & recycling proceed. In this way, autophagy helps cells respond to a wide range of extracellular and intracellular stresses (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The machinery of autophagy.

Roles of autophagy with relevant compounds in cancer

Autophagy has been demonstrated to be able to act as either cell guardian or executioner in cancer. Self‐recycling properties of autophagy can function as a tumour‐promoting mechanism, while its cell death characteristics may help autophagy work as type II PCD 28. Both oncogenesis and tumour suppression are influenced by perturbations of the molecular machinery that control autophagy. Numerous oncogenic proteins, including Bcl‐2, Ras, mTOR, PI3KCI, AKT and MAPKs may suppress autophagy, while several tumour suppressor proteins, such as Beclin‐1 interacome, DAPK1, LKB1/STK11 and PTEN promote it 29. However, it is surprising to find that p53, one of the most important tumour suppressor proteins, regulates autophagy based on its different subcellular localization 30. Small molecule compounds that regulate protein function and affect biological processes have been extensively employed to dissect biological pathways and to study different diseases. With deepening research into cancer treatment via different autophagic signalling pathways, several kinds of small molecule compounds have been revealed to promote or suppress autophagy, by targeting corresponding autophagy‐related signalling pathways. Here, we have provided examples of specific mechanisms of some widely accepted autophagic modulators such as PI3KCI/AKT/mTORC1 signalling pathway, Beclin‐1 interactome and p53, as mentioned above.

PI3KCI/AKT/mTORC1 pathway with relevant small molecule compounds

mTOR‐dependent signalling pathway, induced by insulin or amino acid depletion, is the major mechanism which controls autophagic activities. As a principal regulator of cell population growth, mTORC1 is deregulated in most human cancers, and can be promoted by activation of class I phosphotidylinositol 3‐kinase (PI3KCI) and its downstream components, such as AKT kinase 31. Enhanced activity of PI3KCI is often found via activating kinase mutations or gene amplification in cancers, thus inhibiting autophagy 32. Further, AKT mutational activation may suppress autophagy in response to metabolic stress, whereas AKT kinase inhibition potently induces autophagy by inactivating mTORC1 33. After activation of PI3KCI, AKT is phosphorylated by PDK1, a pleckstrin homology domain (PH‐domain)‐containing protein. Subsequently, AKT regulates a number of targets – kinases, transcription factors and other regulatory molecules 36. Over‐expression of two tumour suppressors, PTEN and ARHI, induce autophagy by negatively regulating the PI3KCI/AKT/mTORC1 pathway 34. A further well‐known major homeostatic regulator, AMPK suppresses activation of mTORC1 by direct phosphorylation of mTOR; thus, targeting AMPK can be an important therapeutic strategy to overcome cancer. By mediating protein translation, mTORC1 regulates autophagy, and the mTORC1 sub‐network may occupy a central position in autophagic pathways. Thus, autophagy is controlled by a complicated network of signalling routes mostly dependent on PI3KCI/AKT/mTORC1, an important oncogenic signalling mechanism involved in many human cancers.

Our understanding of the interplay between autophagy and cancer first benefited from availability of rapamycin, a natural product that inhibits mTORC1 by dissociating raptor from mTOR, thus limiting access of mTOR to some substrates 35. With its exquisite selectivity, rapamycin is used as an indispensable pharmacological probe for elucidating biological functions of mTOR serine/threonine kinase, in governing cell population growth and proliferation 36. Since rapamycin has significant therapeutic effects, its synthetic analogues including temsirolimus (CCI‐779), everolimus (RAD001) and ridaforolimus (AP23573), have also been developed to improve pharmacokinetic properties and produce advantageous intellectual property positions 37. Temsirolimus is a pro‐drug of sirolimus, and contains a dihydroxylmethyl propionic acid ester moiety at the C‐40‐O position. This is quickly hydrolyzed after intravenous administration, aiding treatment of cancers such as acute myeloid leukaemia, non–small−cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and renal cell carcinoma 38. In addition, everolimus enhances anti‐tumour effects of oncolytic adenovirus Delta−24−RGD, by inducing autophagy in gliomas 36. It's effect in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, prostate cancer and NSCLC causes increased autophagy and reduced tumour size 36. With a dimethyl phosphate group at C‐40‐O position, ridaforolimus has been aimed to treat various cancers, such as advanced malignancies and relapsed haematological ones 38. Four additional mTORC1 inhibitors, rottlerin, niclosamide, perhexiline and torin1, promote autophagy by directly inhibiting mTORC1 function or inhibiting proteins upstream of the mTOR pathway in cancer cells, under nutrient‐rich conditions 39. Interestingly, rottlerin also targets TSC2, a negative regulator of mTORC1, thereby suppressing mTORC1 signalling 39. In addition, metformin, primarily known as an activator of AMPK, represses expression of mTORC1 by its interaction with AMPK. After activation of AMPK by treating metformin, activated AMPK directly phosphorylates mTOR and suppresses its activation, resulting in activating substrates of mTORC1, including the ULK1 complex, which is essential for autophagosome formation.

ATP‐competitive inhibitors directly prevent mTOR function and suppress AKT phosphorylation in primary leukaemic cells and stromal cells cultured alone or in combination with leukaemic cells 40. As ATP‐competitive inhibitors, PP242 and AZD8055 block phosphorylation of mTORC1 substrates and AKT, while AZD8055 also shows excellent selectivity against all PI3K isoforms and other members of PI3K‐like kinase family 40, 41. Both these inhibitors greatly prevent cell proliferation and suppresses tumour growth by inducing autophagy in malignancy, such as cancer of the head and neck, squamous cell carcinoma and acute myeloid leukaemia.

Phenethyl isothiocyanate, a promising chemo‐preventive agent of human prostate cancer, induces autophagic cell death by suppressing phosphorylation of both AKT and mTORC1 42. 2‐deoxyglucose and glucose 6‐phosphate also reduce mTORC1 and AKT phosphorylation, which have been used in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and other lymphoid malignancies 43. As a main active component of marijuana, THC induces autophagic cell death and enhances endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress by inhibiting AKT and mTORC1 in cancer cells 44. Resveratrol, a polyphenol present in grapes, peanuts and other plants, is known to display anti‐tumour activities, promoting cell death by triggering autophagy and thereby activating AKT and mTORC1 in ovarian cancer cells 45. The standard first‐line systemic drug sorafenib is used to treat advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); it can activate AKT through an mTOR feedback loop, switching protective autophagy into autophagic cell death 46.

A class of PI3KCI inhibitors with multiple‐target abilities has also emerged. The 1H‐imidazo [4,5‐c]quinoline derivative NVP‐BEZ235 inhibits activities of PI3KCI/AKT/mTOR cascade by binding to the ATP‐binding cleft of both PI3CKI and mTOR, in glioma cells 47. PI103 is a potent inhibitor of both PI3KCI and mTOR, thereby preventing AKT phosphorylation and resulting in enhancement of autophagy. This compound may also inhibit proliferation and invasion of cancer cells, as it suppresses tumour growth in a variety of human cancers with genetic abnormalities of PI3KCI activation 48. With a morpholino pyridinopyrimidine core structure, KU0063794 (AstraZeneca) has, presumably, been developed using PI103 as lead compound, and has high potential and selectivity as an mTOR inhibitor 49. In addition, the synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone potently inhibits the PI3KCI/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia cells, and is used clinically as a chemotherapeutic agent against many haematological malignancies 15. Also, PTEN, a tumour suppressor frequently mutated in human tumours, induces autophagy by inhibiting the PI3KCI/AKT/mTOR signalling cascade. It has been found that magnolol blocks PI3K/PTEN/AKT and induces H460 autophagic cell death, underlining potential utility of its induction as a new cancer treatment 50 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

PI3KCI–Akt‐mTORC1 pathway and its autophagy‐modulated compounds in cancer.

Beclin‐1 interactome with relevant small molecule compounds

Beclin‐1, mammalian homologue of ATG6, enhances autophagy by combining with PI3KIII/Vps34 in autophagic inducton, as the evolutionarily conserved domain of Beclin‐1 interacts with PI3KIII/Vps34 51. This Beclin‐1‐Vps34 complex is primarily regulated by post‐translational modification and several Beclin‐1 binding partners 52. Beclin‐1 is also a direct substrate of caspases‐3/7/8 in apoptosis, whose caspase cleavage is sufficient to suppress autophagy in cancer 53. Beclin‐1 is mediated by positive regulators such as UVRAG, Bif‐1, AMBRA1, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), survivin, and PTEN‐induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1), as well as having negative regulators including Bcl‐2, Bcl‐XL, Mcl‐1 and RUBICON 54. UVRAG interacts with Beclin‐1 and PI3KCIII/Vps34, while Bif‐1 fuses with Beclin‐1 through UVRAG, thereby enhancing autophagy 55. AMBRA1 promotes Beclin‐1 interaction with its target PI3KCIII/Vps34 and mediates autophagosome nucleation 56. As an extracellular damage‐associated molecular pattern molecule, HMGB1 disrupts interaction between Beclin‐1 and its negative regulator Bcl‐2, by competitively binding to Beclin‐1 57.

A further positive modulator is the anti‐apoptotic protein, survivin, which presents a possible mechanism in crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis by Beclin‐1‐mediated degradation 58. PINK1, a serine/threonine protein kinase in mitochondria, also interacts with Beclin‐1 thus inducing autophagy 17. Beclin‐1 contains a BH‐3 motif necessary for binding to Bcl‐2, Bcl‐XL and Mcl‐1. Bcl‐2 blocks Beclin‐1 interaction with PI3KCIII/Vps34 and reduces PI3KCIII activity, while Bcl‐XL and Mcl‐1 inhibit Beclin‐1 activity by stabilizing Beclin‐1 homo‐dimerization 59, 60.

Contrary to UVRAG and Bif‐1, RUBICON prevents kinase activity of PI3KCIII/Vps34 and blocks autophagosome maturation; it is also involved in endocytic pathways by inducing aberrant endosomes and blocking EGFR degradation 50. Interaction of Bcl‐2/Bcl‐XL with the Beclin‐1/Vps34 complex reduces PI3KCIII/Vps34 activity, and this interaction can be competitively disrupted by BH3‐only proteins, such as Bad. Thus, in cancers, Beclin‐1 enhances autophagy and inhibits tumourigenesis, by mediation of positive and negative regulators.

Although currently no Beclin‐1‐related drugs have undergone successful trials for clinical use, a number of small molecule compounds can target Beclin‐1 in different cancer cells. As a possible lead compound for development of anti‐cancer drugs, spautin‐1 is also a potent inhibitor of autophagy. It promotes degradation of PI3KCIII/Vps34 complexes by inhibiting two ubiquitin‐specific peptidases, USP10 and USP13, which target the Beclin‐1 subunit of Vps34 complexes 61. Xestosponging B disrupts Beclin‐1 through an indirect link established by Bcl‐2, and then interferes with the molecular complex formed by PI3KIII and Beclin‐1 62. BH3 mimetic ABT‐737 specifically reduces interaction between Bcl‐2 and Bcl‐XL with the BH3 motif of Beclin‐1, which stimulates Beclin‐1‐dependent activation of PI3KCIII 63. A chemotherapeutic vitamin D analogue, EB1089, promotes massive autophagy by disrupting inhibitory interaction between two BH3 domains of Beclin‐1 and Bcl‐2 64 and a further small molecule inhibitor, gossypol, interrupts interaction between Beclin‐1 and Bcl‐2/Bcl‐XL at ER and induces autophagy in a Beclin‐1‐/Atg5‐dependent manner 65. In addition, tamoxifen, a well‐recognized anti‐tumour drug for breast cancer treatment, is able to increase levels of Beclin‐1 to stimulate autophagy 66. Generally regarded as an mTORC1 inhibitor, RAD001 (everolimus) has also been found to increase Beclin‐1 expression and induce autophagy in leukaemia 67, 68.

Some small molecule compounds directly inhibit PI3KIII, thereby influencing expression of Beclin‐1. 3‐Methyladenine is also used as a specific inhibitor of autophagic sequestration, controlling PI3KCIII and thus providing a target for its action 69. Furthermore, anti‐proteolytic effects of wortmannin (IC50 = 30 nm) and LY294002 (IC50 = 10 μm) have been found to be accompanied, not by an increase in lysosomal pH or a reduction in intracellular ATP, but by inhibition of autophagic sequestration 70. Thus, PI3KCIII inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002 inhibit autophagy in isolated hepatocytes (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Beclin‐1, PI3KCIII and their autophagy‐regulating compounds in cancer.

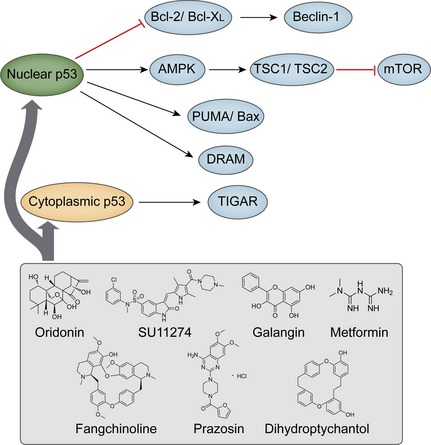

p53 with relevant small molecule compounds

Embedded within a highly interconnected signalling pathway, p53 regulates key cell processes such as DNA repair, metabolism, development, inflammation, endocytosis and cell death 71. It has been demonstrated that p53 can positively or negatively control autophagy, but its role in autophagy is paradoxical as it depends on its subcellular location; it occurs in two forms, cytoplasmic p53 and nuclear p53 72. During responses of p53 to DNA damage, a number of cell death genes are transcriptionally activated, some of which play important roles in autophagy. When exposed to stress, nuclear p53 induces autophagy by acting at multiple levels on the AMPK‐mTOR axis. It may down‐regulate mTOR by transcriptional regulation of main activators of AMPK‐Sestrin1/2, and target it to phosphorylate tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2) 73. Damage‐regulated autophagy modulator (DRAM) can also be regarded as a transcriptional target of nuclear p53 in autophagy modulation, explaining the complexity of mutual regulation in apoptosis and autophagy 74. Regarding this crosstalk, the pro‐autophagic role of p53 can influence expression of Bcl‐2 protein family members, including Bcl‐2, Bcl‐XL, Mcl‐1, and Bad, while reduction of p53 induces release of Beclin‐1 from sequestration 75. p53‐inducible BH3‐only protein PUMA induces mitochondrial autophagy, but Bax alone can induce mitochondria‐selective autophagy in the absence of PUMA activation 76. Following activation, cytoplasmic p53 translocates to the nucleus and regulates expression of a number of target genes 77. In this condition, PUMA enhances cell death by targeting mitochondria to autophagy, and in response to mitochondrial dysfunction, p53 also induces DRAM1‐dependent autophagy 78. Cytoplasmic p53 also inhibits autophagy through inhibition of AMPK and activation of mTOR, resulting in hyper‐phosphorylation of AMPK, TSC2, acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACCα) and p70S6K 79. As a target of cytoplasmic p53, TP53‐induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator (TIGAR) inhibits autophagy by negatively modulating glycolysis and suppressing reactive oxygen species 80. However, divergent effects of nuclear and cytoplasmic p53 are still controversial. p53 variants in the cytoplasm significantly inhibit autophagy, whereas those in the nucleus may fail to suppress it. Thus, p53 plays a role in controlling the basal level of autophagy, as nuclear p53 boost it and cytoplasmic p53 reduces it, independent of its transcriptional activity.

There are numbers of small molecule compounds identified to target p53 in different cancer cells. Tetracycline diterpenoid natural product oridonin activates p53 and ERK in murine fibrosarcoma L929 cells. Nitric oxide has been demonstrated to play a pivotal role in oridonin‐induced autophagy, whose production may lead to oridonin‐induced p53 and ERK activation, oridonin inducing autophagy in L929 cells via the nitric oxide‐ERK‐p53 positive‐feedback loop 79, 80. As a selective Met tyrosine kinase inhibitor, SU11274 activation leads to autophagic cell death in NSCLC A549 cells. It has been demonstrated that p53 can be activated after SU11274 treatment, while interruption of p53 activity reduces SU11274‐induced autophagy 81. Treatment with polyphenolic compound, galangin, inhibits cell proliferation and induces autophagy, particularly leading to accumulation of autophagosomes and increase in p53 expression. This mediates autophagy through a p53‐dependent pathway in HCC HepG2 cells 82. Additionally, metformin increases expression of p53, but reduces mRNA level of anti‐apoptotic Bcl‐2. It has been demonstrated that anti‐melanoma effects of metformin are mediated through autophagy associated with p53/Bcl‐2 modulation, mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress 83. Fangchinoline is a highly specific anti‐tumour agent which induces autophagic cell death via p53/Sestrin2/AMPK signalling in HCC HepG2 and PLC/PRF/5 cells 84. Previously used to treat high blood pressure and anxiety, prazosin has been found to induce patterns of autophagy by a p53‐mediated mechanism in HPC2 cells, since cells exposured to prazosin have higher levels of phospho‐p53 and phospho‐AMPK 85. What is more, dihydroptychantol A, a macrocyclic bisbibenzyl derivative, increases p53 expression, induces p53 phosphorylation and up‐regulates p21 (Waf1/Cip1), thus mediating autophagy associated with p53, in human osteosarcoma U2OS cells 86 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

p53 and its autophagy‐regulating compounds in cancer.

Conclusions

As an evolutionarily conserved lysosomal degradation process, autophagy is Janus‐faced in cancer; it primarily acts as a survival mechanism, but can lead to cell death under certain circumstances. Autophagy can be modulated by some key oncogenes (for example, PI3KCI, AKT, and mTORC1) and tumour suppressors (Beclin‐1 and p53), which are implicated in autophagic signalling pathways. This seals the fate of the cancer cells. In addition, several small molecule drugs have also been demonstrated to target or regulate corresponding autophagic signalling pathways in cancer. To a certain extent, our understanding of the links between autophagy and cancer has benefited from the availability of rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor, proven to be powerful at discerning major players in cancers associated with autophagy.

Autophagy interacts with cell death pathways via multiple mechanisms in different contexts, although its effect on cell death decisions is not always predictable. However, there is promising pre‐clinical and clinical evidence, suggesting autophagy modulators may enhance certain types of anti‐cancer treatment and reduce resistance to therapies, in many cases. Better understanding of how autophagy determines cell death decisions in specific contexts and development of new drugs, which will allow fine tuning of the autophagic response, have great potential to lead to novel anti‐cancer treatment.

Although many small molecule compounds that regulate autophagy are presently utilized in autophagy research, some of these molecules have multiple functions and targets. As a result, more selective inducers and inhibitors of autophagy need to be developed to unravel the network of processes. The best hope for cancer therapeutics may lie in discovering candidate small molecule drugs that target core oncogenic or tumour‐suppressive autophagic pathways or even the autophagic network itself, rather than individual genes or proteins. Application of combinatorial treatment may overcome weaknesses and limitations of traditional single‐target drugs by employing a network‐level perspective, and inhibiting multiple pathways. Thus, further elucidation of the complicated mechanisms involved in autophagy will provide promising information to promote discovery of novel small molecule drugs targeting oncogenic and tumour suppressive autophagic networks, in the near future.

Conflict of interest

We declare that none of the authors has a financial interest related to this work.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Key Projects of the National Science and Technology Pillar Program (no. 2012BAI30B02) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos 81402496, 81473091, U1170302, 81160543, 81260628, 81303270 and 81172374).

References

- 1. Klionsky DJ (2007) Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 931–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Parzych KR, Klionsky DJ (2014) An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 460–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Levine B, Kroemer G (2008) Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 132, 27–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu B, Wen X, Cheng Y (2013) Survival or death: disequilibrating the oncogenic and tumor suppressive autophagy in cancer. Cell Death Dis. 4, e892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu B, Cheng Y, Liu Q, Bao JK, Yang JM (2010) Autophagic pathways as new targets for cancer drug development. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 31, 1154–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huang J, Klionsky DJ (2007) Autophagy and human disease. Cell Cycle 6, 1837–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rabinowitz JD, White E (2010) Autophagy and metabolism. Science 330, 1344–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maiuri MC, Tasdemir E, Criollo A, Morselli E, Vicencio JM, Carnuccio R et al (2009) Control of autophagy by oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Cell Death Differ. 16, 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feng Y, He D, Yao Z, Klionsky DJ (2014) The machinery of macroautophagy. Cell Res. 1, 24–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hara T, Takamura A, Kishi C, Iemura S, Natsume T, Guan JL et al (2008) FIP200, a ULK‐interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 181, 497–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jung CH, Jun CB, Ro SH, Kim YM, Otto NM, Cao J et al (2009) ULK‐Atg13‐FIP200 complexes mediate mTORC1 signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1992–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hosokawa N, Sasaki T, Iemura S, Natsume T, Hara T, Mizushima N (2009) Atg101, a novel mammalian autophagy protein interacting with Atg13. Autophagy 5, 973–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martina JA, Chen Y, Gucek M, Puertollano R (2012) MTORC1 functions as a transcriptional regulator of autophagy by preventing nuclear transport of TFEB. Autophagy 8, 903–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Itakura E, Kishi C, Inoue K, Mizushima N (2008) Beclin 1 forms two distinct phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase complexes with mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 5360–5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fu LL, Cheng Y, Liu B (2013) Beclin‐1: autophagic regulator and therapeutic target in cancer. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 45, 921–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nazio F, Cecconi F (2013) mTOR, AMBRA1, and autophagy: an intricate relationship. Cell Cycle 12, 2524–2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Tang D (2011) The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 18, 571–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mizushima N, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Tanaka Y, Ishii T, George MD et al (1998) A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature 395, 395–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mizushima N, Kuma A, Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto A, Matsubae M, Takao T et al (2003) Mouse Apg16L, a novel WD‐repeat protein, targets to the autophagic isolation membrane with the Apg12‐Apg5 conjugate. J. Cell Sci. 116, 1679–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geng J, Klionsky DJ (2008) The Atg8 and Atg12 ubiquitin‐like conjugation systems in macroautophagy. EMBO Rep. 9, 859–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reggiori F, Tucker KA, Stromhaug PE, Klionsky DJ (2004) The Atg1‐Atg13 complex regulates Atg9 and Atg23 retrieval transport from the pre‐autophagosomal structure. Dev. Cell 6, 79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Satoo K, Noda NN, Kumeta H, Fujioka Y, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y et al (2009) The structure of Atg4B‐LC3 complex reveals the mechanism of LC3 processing and delipidation during autophagy. EMBO J. 28, 1341–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Atlashkin V, Kreykenbohm V, Eskelinen E‐L, Wenzel D, Fayyazi A, Fischer von Mollard G (2003) Deletion of the SNARE vti1b in mice results in the loss of a single SNARE partner, syntaxin 8. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 5198–5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Furuta N, Fujita N, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Amano A (2010) Combinational soluble N‐ethylmaleimide‐sensitive factor attachment protein receptor proteins VAMP8 and Vti1b mediate fusion of antimicrobial and canonical autophagosomes with lysosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 1001–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Itakura E, Kishi‐Itakura C, Mizushima N (2012) The hairpin‐type tail‐anchored SNARE syntaxin 17 targets to autophagosomes for fusion with endosomes/lysosomes. Cell 151, 1256–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang SY, Yu QJ, Zhang RD, Liu B (2011) Core signaling pathways of survival/death in autophagy‐related cancer networks. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 43, 1263–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morselli E, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Vicencio JM, Criollo A, Maiuri MC et al (2009) Anti‐ and pro‐tumor functions of autophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1793, 1524–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McCarthy N (2014) Autophagy: directed development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 74–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ren XS, Sato Y, Harada K, Sasaki M, Furubo S, Song JY et al (2014) Activation of the PI3K/mTOR pathway is involved in cystic proliferation of cholangiocytes of the PCK rat. PLoS One 9, e87660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lin Z, Liu T, Kamp DW, Wang Y, He H, Zhou X et al (2014) AKT/mTOR and C‐ N‐terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathways are required for chrysotile asbestos‐induced autophagy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 72, 296–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nho RS, Hergert P (2014) IPF fibroblasts are desensitized to type I collagen matrix‐induced cell death by suppressing low autophagy via aberrant Akt/mTOR kinases. PLoS One 9, e94616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM (2011) mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 21–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ciuffreda L, Di Sanza C, Incani UC, Milella M (2010) The mTOR pathway: a new target in cancer therapy. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 10, 484–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hartford CM, Ratain MJ (2007) Rapamycin: something old, something new, sometimes borrowed and now renewed. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 82, 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu Q, Thoreen C, Wang J, Sabatini D, Gray NS (2009) mTOR mediated anti‐cancer drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today Ther. Strateg. 6, 47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ku F, McConkey DJ, Hong DS, Kurzrock R (2011) Autophagy as a target for anticancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 8, 528–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rubinsztein DC, Codogno P, Levine B (2012) Autophagy modulation as a potential therapeutic target for diverse diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 709–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Balgi AD, Fonseca BD, Donohue E, Tsang TC, Lajoie P, Proud CG et al (2009) Screen for chemical modulators of autophagy reveals el therapeutic inhibitors of mTORC1 signaling. PLoS One 4, e7124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Apsel B, Blair JA, Gonzalez B, Nazif TM, Feldman ME, Aizenstein B et al (2008) Targeted polypharmacology: discovery of dual inhibitors of tyrosine and phosphoinositide kinases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 691–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bomeddy A, Hahm ER, Xiao D, Powolny AA, Fisher AL, Jiang Y et al (2009) Atg5 regulates phenethyl isothiocyanate‐induced autophagic and apoptotic cell death in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 69, 3704–3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raviku B, Stewart A, Kita H, Kato K, Duden R, Rubinsztein DC (2003) Raised intracellular glucose concentrations reduce aggregation and cell death caused by mutant huntingtin exon 1 by reasing mTOR phosphorylation and inducing autophagy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 985–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Salazar M, Carracedo A, Salanueva IJ, Hernández‐Tiedra S, Lorente M, Egia A et al (2009) Cannabinoid action induces autophagy‐mediated cell death through stimulation of ER stress in human glioma cells. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1359–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Scarlatti F, Maffei R, Beau I, Codogno P, Ghidoni R (2008) Role of non‐canonical Beclin 1‐independent autophagy in cell death induced by resveratrol in human breast cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 15, 1318–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bareford MD, Park MA, Yacoub A, Hamed HA, Tang Y, Cruickshanks N et al (2011) Sorafenib enhances pemetrexed cytotoxicity through an autophagy‐dependent mechanism in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 71, 4955–4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu TJ, Koul D, LaFortune T, Tiao N, Shen RJ, Maira SM et al (2009) NVP‐BEZ235, a novel dual phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, elicits multifaceted antitumor activities in human gliomas. Mol. Cancer Ther. 8, 2204–2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fan QW, Cheng C, Hackett C, Feldman M, Houseman BT, Nicolaides T et al (2010) Akt and autophagy cooperate to promote survival of drug‐resistant glioma. Sci. Signal. 3, ra81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. García‐tínez JM, Moran J, Clarke RG, Gray A, Cosulich SC, Chresta CM et al (2009) Ku‐0063794 is a specific inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). Biochem. J. 421, 29–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Laane E, Tamm KP, Buentke E, Ito K, Kharaziha P, Oscarsson J et al (2009) Cell death induced by dexamethasone in lymphoid leukemia is mediated through initiation of autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 16, 1018–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li HB, Yi X, Gao JM, Ying XX, Guan HQ, Li JC (2007) Magnolol‐induced H460 cells death via autophagy but not apoptosis. Arch. Pharm. Res. 30, 1566–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vicencio JM, Ortiz C, Criollo A, Jones AW, Kepp O, Galluzzi L et al (2009) The inositol 1, 4, 5‐trisphosphate receptor regulates autophagy through its interaction with Beclin 1. Cell Death Differ. 16, 1006–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li H, Wang P, Sun Q, Ding WX, Yin XM, Sobol RW et al (2011) Following cytochrome c release, autophagy is inhibited during chemotherapy‐induced apoptosis by caspase 8‐mediated cleavage of Beclin 1. Cancer Res. 71, 3625–3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McKnight NC, Zhenyu Y (2013) Beclin 1, an essential component and master regulator of PI3K‐III in health and disease. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep. 1, 231–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li X, He L, Che KH, Funderburk SF, Pan L, Pan N et al (2012) Imperfect interface of Beclin1 coiled‐coil domain regulates homodimer and heterodimer formation with Atg14L and UVRAG. Nat. Commun. 3, 662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Di Bartolomeo S, Corazzari M, Nazio F, Oliverio S, Lisi G, Antonioli M et al (2010) The dynamic interaction of AMBRA1 with the dynein motor complex regulates mammalian autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 19, 155–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tang D, Kang R, Livesey KM, Cheh CW, Farkas A, Loughran P et al (2010) Endogenous HMGB1 regulates autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 190, 881–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mobahat M, Narendran A, Riabowol K (2014) Survivin as a preferential target for cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 2494–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Michiorri S, Gelmetti V, Giarda E, Lombardi F, Romano F, Marongiu R et al (2010) The Parkinson‐associated protein PINK1 interacts with Beclin1 and promotes autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 17, 962–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N et al (2005) Bcl‐2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1‐dependent autophagy. Cell 122, 927–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sun Q, Zhang J, Fan W, Wong KN, Ding X, Chen S et al (2011) The RUN domain of rubicon is important for hVps34 binding, lipid kinase inhibition, and autophagy suppression. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 185–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Liu J, Xia H, Kim M, Xu L, Li Y, Zhang L et al (2011) Beclin1 controls the levels of p53 by regulating the deubiquitination activity of USP10 and USP13. Cell 147, 223–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Malik SA, Orhon I, Morselli E, Criollo A, Shen S, Mariño G et al (2011) BH3 mimetics activate multiple pro‐autophagic pathways. Oncogene 30, 3918–3929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hoyer‐Hansen M, Bastholm L, Mathiasen IS, Elling F, Jaattela M (2005) Vitamin D analog EB1089 triggers dramatic lysosomal changes and Beclin 1‐mediated autophagic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 12, 1297–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lian J, Wu X, He F, Karnak D, Tang W, Meng Y et al (2011) A natural BH3 mimetic induces autophagy in apoptosis‐resistant prostate cancer via modulating Bcl‐2‐Beclin1 interaction at endoplasmic reticulum. Cell Death Differ. 18, 60–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wienecke R, Fackler I, Linsenmaier U, Linsenmaier U, Mayer K, Licht T et al (2006) Antitumoral activity of rapamycin in renal angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 48, e27–e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Crazzolara R, Bradstock KF, Bendall LJ (2009) RAD001 (Everolimus) induces autophagy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Autophagy 5, 727–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Blommaart EF, Krause U, Schellens JP, Vreeling‐Sindelarova H, Meijer AJ (1997) The phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002 inhibit autophagy in isolated rat hepatocytes. Eur. J. Biochem. 243, 240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wu YT, Tan HL, Shui G, Bauvy C, Huang Q, Wenk MR et al (2010) Dual role of 3‐methyladenine in modulation of autophagy via different temporal patterns of inhibition on class I and III phosphoinositide 3‐kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 10850–10861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Shang LB, Wang XD (2011) AMPK and mTOR coordinate the regulation of Ulk1 and mammalian autophagy initiation. Autophagy 7, 924–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Jiang L, Sheikh MS, Huang Y (2010) Decision making by p53: life versus death. Mol. Cell Pharmacol. 2, 69–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ryan KM (2011) P53 and autophagy in cancer: guardian of the genome meets guardian of the proteome. Eur. J. Cancer 47, 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Feng Z, Zhang H, Levine AJ, Jin S (2005) The coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 8204–8209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Crighton D, Wilkinson S, O'Prey J, Syed N, Smith P, Harrison PR et al (2006) DRAM, a p53‐induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell 126, 121–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kawamura T, Suzuki J, Wang YV, Menendez S, Morera LB, Raya A et al (2009) Linking the p53 tumour suppressor pathway to somatic cell reprogramming . Nature 460, 1140–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yee KS, Wilkinson S, James J, Ryan KM, Vousden KH (2009) PUMA and Bax‐induced autophagy contributes to apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 16, 1135–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sui X, Jin L, Huang X, Geng S, He C, Hu X (2011) P53 signaling and autophagy in cancer: a revolutionary strategy could be developed for cancer treatment. Autophagy 7, 565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tasdemir E, Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Djavaheri‐Mergny M, D'Amelio M et al (2008) Regulation of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 676–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Morselli E, Tasdemir E, Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Criollo A et al (2008) Mutant p53 protein localized in the cytoplasm inhibits autophagy. Cell Cycle 19, 3056–3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bensaad K, Tsuruta A, Selak MA, Vidal MN, Nakano K, Bartrons R et al (2006) TIGAR, a p53‐inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell 126, 107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Morselli E, Kepp O, Malik SA, Kroemer G (2010) Autophagy regulation by p53. Cur. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ye YC, Wang HJ, Xu L (2012) Oridonin induces apoptosis and autophagy in murine fibrosarcoma L929 cells partly via NO‐ERK‐p53 positive‐feedback loop signaling pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 33, 1055–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Liu Y, Yang Y, Ye YC, Shi QF, Chai K, Tashiro S et al (2012) Activation of ERK‐p53 and ERK‐mediated phosphorylation of Bcl‐2 are involved in autophagic cell death induced by the c‐Met inhibitor SU11274 in human lung cancer A549 cells. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 118, 423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Wen M, Wu J, Luo H, Zhang H (2012) Galangin induces autophagy through upregulation of p53 in HepG2 cells. Pharmacology 89, 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Janjetovic K, Harhaji‐Trajkovic L, Misirkic‐Marjanovic M, Vucicevic L, Stevanovic D, Zogovic N et al (2011) In vitro and in vivo anti‐melanoma action of metformin. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 668, 373–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Wang N, Pan W, Zhu M, Zhang M, Hao X, Liang G et al (2011) Fangchinoline induces autophagic cell death via p53/sestrin2/AMPK signalling in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 164, 731–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Yang YF, Wu CC, Chen WP, Chen YL, Su MJ (2011) Prazosin induces p53‐mediated autophagic cell death in H9C2 cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 384, 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Li X, Wu WK, Sun B, Cui M, Liu S, Gao J et al (2011) Dihydroptychantol A, a macrocyclic bisbibenzyl derivative, induces autophagy and following apoptosis associated with p53 pathway in human osteosarcoma U2OS cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 251, 146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]