Abstract

Objectives: Bone morphogenic protein‐2 (BMP‐2) has long been used to promote bone and periodontal regeneration, while core binding factor α1 (CBFA1) plays important roles in both osteogenic differentiation and tooth morphogenesis. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of CBFA1 or BMP‐2 overexpression on osteoblast/cementoblast‐related gene expressions in NIH3T3 cells and dental follicle cells (DFCs).

Materials and methods: CBFA1 or BMP‐2 overexpression in NIH3T3 and DFCs was achieved by infection with retroviral vectors containing CBFA1 or BMP‐2 cDNA. Cells stably integrated with CBFA1 or BMP‐2 cDNA were selected with G418 for 14 days. Western blotting, real‐time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction, and in vitro mineralization assay were performed to evaluate effects of CBFA1 or BMP‐2 overexpression in cells undergoing osteoblast/cementoblast differentiation.

Results: Our results demonstrated that osteoblast/cementoblast‐related gene expression levels in CBFA1‐overexpressing NIH3T3 cells were higher than those in BMP‐2‐overexpressing cells. More mineral nodules were observed in CBFA1‐overexpressing NIH3T3 cells than in BMP‐2‐overexpressing cells. CBFA1 overexpression in DFCs also increased osteoblast/cementoblast‐related gene expression and promoted mineral nodule formation. However, no significant changes in gene expression levels nor mineral nodule formation were found in BMP‐2‐overexpressing DFCs when compared with empty vector transduced DFCs.

Conclusions: CBFA1 overexpression up‐regulated expression levels of osteoblast/cementoblast‐related genes and enhanced in vitro osteogenic differentiation more efficiently than BMP‐2 in both NIH3T3 cells and DFCs.

Introduction

Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease that leads to progressive destruction of tooth‐supporting structures, including periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone. The ultimate goal of periodontal treatment is to restore architecture and function of periodontal tissues to predisease state by formation of new alveolar bone, cementum, and periodontal ligament (1, 2). To achieve this, application of molecular factors in tissue engineering to promote periodontal regeneration has been an area of intensive interest. Putative factors reported to promote bone and periodontal regeneration include growth factors, such as bone morphogenetic/osteogenic proteins (BMP/OP) (3, 4), transcription factors such as CBFA1 (5) and adhesion factors, such as bone sialoprotein and osteopontin (6, 7).

In 1965, it was reported that certain substances in the extracellular bone matrix can induce new bone formation when implanted into intramuscular sites (8). This led to the discovery of BMPs/OPs, which were identified as members of the transforming growth factor‐β superfamily (9, 10). It has been reported that BMPs/OPs are pleiotropic morphogens governing the three key steps in the bone‐induction cascade, including chemotaxis and mitosis, cartilage differentiation, and then replacement by bone (11). Since their discovery, BMPs/OPs have been applied to bone defects as alternative methods to promote bone regeneration, considering low therapeutic effects associated with bone grafts and metal implants (12, 13, 14). Recently, commercially available collagen‐based products containing BMP‐2 as osteo‐inductive materials were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for human clinical use (15). BMP‐2 InfuseΤΜ bone graft (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA; Wyeth, Maidenhead, UK) was approved for certain interbody fusion procedures in 2002, for open tibial fractures in 2004, and for alveolar ridge and sinus augmentations in 2007 (16).

During the last decade, it has been reported that CBFA1 (also known as Runx2, OSF2, AML3, and Pebp2αA), is a master gene for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation (17, 18). Aetiological factors of cleidocranial dysplasia, an autosomal dominant disorder in human and mouse, characterized by defective bone formation, were reported to be various mutations at the CBFA1 gene locus (19). In addition, CBFA1 protein was identified as essential for tooth formation (20, 21) as patients suffering from cleidocranial dysplasia also show dental defects, including multiple supernumerary teeth, delayed eruption of permanent dentition and absence of cellular cementum formation (22, 23).

The gene transfer approach presents an attractive alternative to conventional topical application of molecules to complex periodontal wound sites (24). Use of viral constructs containing one or more response modifier transgenes for long‐term delivery may enhance periodontal regeneration. In the present study, CBFA1 or BMP‐2 cDNA was stably integrated into NIH3T3 cells and DFCs using a retroviral system to evaluate effects of CBFA1 or BMP‐2 overexpression on in vitro osteogenic differentiation. In vitro mineral nodule formation was then performed and changes in expression levels of osteoblast/cementoblast‐related genes were determined.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Retroviral packaging cell line PT67 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and murine fibroblast cell line NIH3T3 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA) were maintained in α‐minimum essential medium (α‐MEM, HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) foetal bovine serum (FBS, HyClone), 100 U/ml penicillin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen).

DFCs were isolated from 5‐ to 7‐day‐old BALB/c mice, as described previously (25). Briefly, bilateral first mandibular molar germs were dissected under a dissecting microscope and were treated with 1% trypsin at 4 °C for 1.5 h. After digestion, loose dental follicle tissues were isolated and cultured in α‐MEM supplemented with 20% (v/v) FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Non‐adherent tissues were removed 24 h later and culture medium was changed every 3 days. DFCs up to three passages were used for further experiments.

Construction of recombinant retroviral plasmids

CBFA1 cDNA was prepared by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from plasmid pCMV5‐CBFA1 (kindly provided by Dr Patricia Ducy, Department of Molecular Genetics, University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center) encoding full‐length mouse CBFA1 cDNA with MASNSL as the N‐terminal sequence (17, 26). PCR primers were: 5′‐CTCGAGATGGCGTCAAACAGCCTCTT‐3′ and 5′‐ACGCGTTCAATATGGCCGCCAAACA‐3′. PCR product was cloned into XhoI‐MluI sites of the vector pIRES (Clontech) and the resulting construct was named as pIRES‐CBFA1. A 2.2‐kb CBFA1‐IRES fragment was then released from pIRES‐CBFA1 by digestion with XhoI and SalI (Takara, Tokyo, Japan), and was subcloned into retroviral vector pLEGFP‐N1 (Clontech). The resulting construct was named pLEGFP‐IRES‐CBFA1. Similarly, BMP‐2 cDNA was generated from plasmid pSP65‐BMP‐2 (provided by Dr Shaohua Liu, Department of Dentistry, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, China) and the primers were: 5′‐ATACTCGAGATGGTGGCCGGGA CCCG‐3′ and 5′‐ATTACGCGTCTAGCGACACCCACAA CCCTCCA‐3′. The PCR product was also ligated into the XhoI‐MluI sites of pIRES. BMP‐2‐IRES fragment was released and subcloned into XhoI‐SalI sites of pLEGFP‐N1. The resulted construct was named pLEGFP‐IRES‐BMP‐2.

Production of viral stocks and viral infection

Packaging cells PT67 were plated in a 6‐well plate (1 × 105 cells/well) 24–48 h before transfection with 4 µg of pLEGFP‐IRES‐CBFA1, pLEGFP‐IRES‐BMP2, or empty vector, using LipofectamineTM 2000 (Invitrogen). Forty‐eight hours after transfection, stable virus‐producing cell lines were selected with 400 µg/ml G418 (Takara) for 2 weeks. Supernatant of these stable virus‐producing PT67 cells was collected, filtered through a 0.45‐µm filter, and stored at –80 °C. The recombinant retrovirus was tested by PCR.

Viral titre was determined indirectly as previously described (27). In brief, NIH3T3 cells were plated in 6‐well plates (2 × 105cells/well). Twenty‐four hours later, they were infected with diluted viral stocks (six 10‐fold serial dilutions, 1–105). Forty‐eight hours after infection, the cells were selected by G418 until obvious cell colonies appeared. Viral titre corresponded to number of colonies presented at the highest dilution that contained colonies, multiplied by the dilution factor.

Twenty‐four hours before transduction, NIH3T3s and DFCs were plated in 6‐well plates (1 × 105cells/well). Cells were then incubated with viral stocks containing pLEGFP‐IRES‐CBFA1, pLEGFP‐IRES‐BMP2 or empty vector pLEGFP‐N1, in the presence of polybrene (6 µg/ml, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 8 h. Twenty‐four hours after infection, NIH3T3 and DFCs were subjected to G418 (300 µg/ml) for 2 weeks. Stably transduced cells were used for the following experiments.

Real‐time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted with Trizol reagent (Takara) from NIH3T3 cells and DFCs infected with pLEGFP‐N1 (serving as negative control), pLEGFP‐IRES‐CBFA1 or pLEGFP‐IRES‐BMP‐2. RNA isolated from non‐infected cells served as empty control. One microgram of total RNA from each cell type was reverse transcribed to cDNA using RevertAidTM First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (MBI Fermentas, Lithuania) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For real‐time PCR, LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) was used and LightCycler PCR reaction mix was prepared according to manufacturer's instructions; primers used are listed in Table 1. In each reaction, 18 µl of master mixture was placed into the glass capillaries and 2 µl of template cDNA was added. Capillaries were then placed into the rotor of the LightCycler (Roche). After a denaturation step at 95 °C for 10 min, 45 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 59 °C for 5 s and 72 °C for 10 s were initiated. Amounts of mRNA were calculated for each sample based on the standard curve using the LightCycler Software 4.0 (Roche). Investigated genes included CBFA1, BMP‐2, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), osteocalcin (OC), osteopontin (OPN), bone sialoprotein gene (BSP), collagen I gene (Col I), gene for cementum attachment protein (CAP) and cementum protein 23 gene (CP23). β‐actin was used as an internal control.

Table 1.

Specific primers used for real‐time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

| Gene | Primer sequence | Melting temperature (°C) | Size (bp) | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP‐2 | 5′‐CCTCAGCAGAGCTTCAGGTT‐3′ | 59.75 | 153 | NM_001200 |

| 5′‐CCAACCTGGTGTCCAAAAGT‐3′ | 59.86 | |||

| CBFA1 | 5′‐CCCAGCCACCTTTACCTACA‐3′ | 59.99 | 150 | NM_009820 |

| 5′‐TATGGAGTGCTGCTGGTCTG‐3′ | 60.01 | |||

| Col I | 5′‐TGACTGGAAGAGCGGAGAGT‐3′ | 60.14 | 151 | NM_007742 |

| 5′‐GTTCGGGCTGATGTACCAGT‐3′ | 60.00 | |||

| OC | 5′‐AAGCAGGAGGGCAATAAGGT‐3′ | 60.10 | 152 | NM_001032298 |

| 5′‐TAGGCGGTCTTCAAGCCATA‐3′ | 60.73 | |||

| OPN | 5′‐TCTGATGAGACCGTCACTGC‐3′ | 59.99 | 170 | AF515708 |

| 5′‐AGGTCCTCATCTGTGGCATC‐3′ | 60.08 | |||

| BSP | 5′‐GAAGCAGGTGCAGAAGGAAC‐3′ | 60.00 | 154 | NM_008318 |

| 5′‐ACTCAACGGTGCTGCTTTTT‐3′ | 59.92 | |||

| ALP | 5′‐AACCCAGACACAAGCATTCC‐3′ | 59.97 | 151 | X13409 |

| 5′‐GAGAGCGAAGGGTCAGTCAG‐3′ | 60.14 | |||

| CAP | 5′‐CCTGGCTCACCTTCTACGAC‐3′ | 59.87 | 156 | AY455942 |

| 5′‐CCTCAAGCAAGGCAAATGTC‐3′ | 60.78 | |||

| CP23 | 5′‐GGCGATGCTCAACCTCTAAC‐3′ | 59.84 | 158 | NM_001048212 |

| 5′‐GATACCCACCTCTGCCTTGA‐3′ | 60.07 | |||

| β‐actin | 5′‐CCCTGAAGTACCCCATTGAA‐3′ | 59.78 | 158 | NM_007393 |

| 5′‐CTTTTCACGGTTGGCCTTAG‐3′ | 59.74 |

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested using 0.25% trypsin and washed twice with PBS. Proteins were extracted using lysis buffer (25 mm Tris‐Cl, pH 7.2, 1% Triton X‐100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Proteins were separated using SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and were transferred to a Protran nitrocellulose membrane, which was saturated overnight in Tris‐buffered saline with Tween and 5% low‐fat milk. The membrane was incubated with anti‐BMP‐2 (1 : 500) or anti‐CBFA1 antibody (1 : 500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), followed by incubation with mouse or rabbit horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated immunoglobulin G (1 : 10 000, Sigma). Blots were visualized using diaminobenzidine, and β‐actin was used as internal control. Images of the blots were analysed using the JD801 IMAGE 4.11 program (Dahui Biotechnology, Guangzhou, China).

Mineralization assay

Infected and non‐infected NIH3T3 cells and DFCs were plated in 24‐well plates (1 × 104 cells/well) in α‐MEM containing 10% FBS. After 24 h, cells were incubated with mineralizing media (α‐MEM containing 10% FBS, 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid, 10 nm dexamethasone, and 10 mmβ‐glycerophosphate). Biomineralization assay (in vitro mineralization assay) was performed at weeks 2, 3 and 4 with von Kossa staining (28). Nodules were photographed using an Olympus CX71 camera (Tokyo, Japan) and areas covered with mineral nodules in each well were determined using image analysis system DT2000 software V1.0 (Tansi Technology Co. Ltd, Nanjing, China).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error from at least three experiments, and t‐testing was used to determine significance using SPSS 12.0 software. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

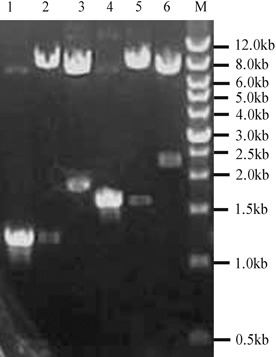

Construction and identification of recombinant plasmids

Recombinant retroviral plasmids pLEGFP‐IRES‐CBFA1 and pLEGFP‐IRES‐BMP‐2 were identified by restriction endonucleases. As shown in Fig. 1, sizes of CBFA1 and BMP‐2 fragments were 1587 and 1191 bp, respectively. Sequence of CBFA1 and BMP‐2 were consistent with their sequences published in GeneBank (BMP‐2: NM_001200; CBFA1: NM_009820).

Figure 1.

Results of agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products and restriction endonuclease digestion analysis. Lane M, wide range DNA marker (500–12000 bp,Takara); lane 1, BMP‐2 gene amplified from plasmid pSP65‐BMP‐2; lane 2, plasmid pLEGFP‐IRES‐BMP‐2 digested with Xho I and Mlu I; lane 3, plasmid pLEGFP‐IRES‐BMP‐2 digested with Xho I and Sal I; lane 4, CBFA1 gene amplified from plasmid pCMV5‐CBFA1; lane 5, plasmid pLEGFP‐IRES‐CBFA1 digested with Xho I and Mlu I; lane 6, plasmid pLEGFP‐IRES‐CBFA1 digested with Xho I and Sal I.

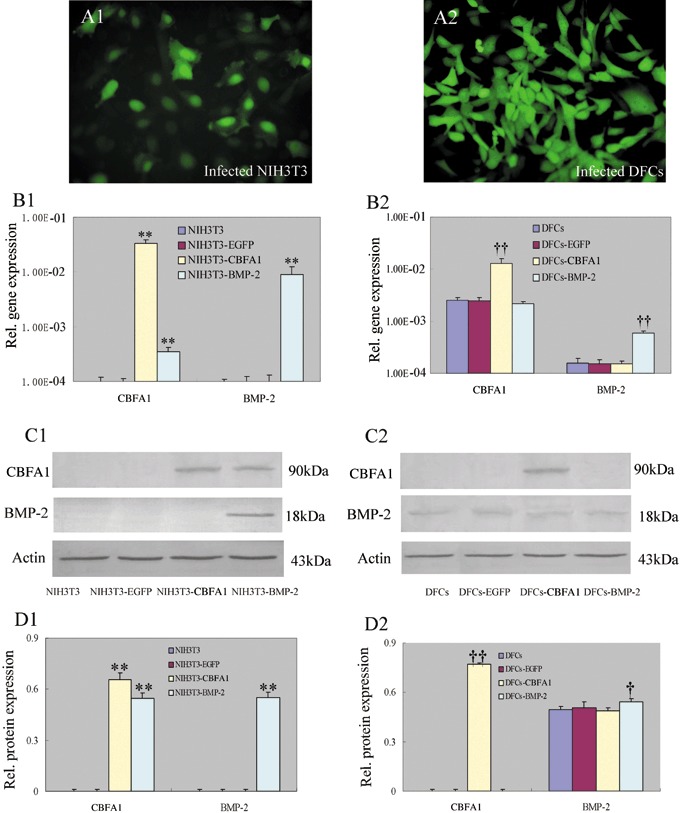

Retroviral infection of NIH3T3s and DFCs

pLEGFP‐IRES‐CBFA1 and pLEGFP‐IRES‐BMP‐2 were transfected into packaging cell line PT67 and stable virus‐producing PT67 cells were obtained by G418 selection. NIH3T3s and DFCs were then infected with virus‐containing supernatants collected from PT67 cells. After G418 selection for 2 weeks, stable CBFA1 or BMP‐2 overexpressing NIH3T3s and DFCs were obtained. Green fluorescence could be observed using an inverted microscope and cells were without significant morphological changes (Fig. 2 A1, A2). Real‐time RT‐PCR confirmed that expression level of CBFA1 or BMP‐2 was increased in pLEGFP‐IRES‐CBFA1 or pLEGFP‐IRES‐BMP‐2 infected cells compared to control cells (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2 B1, B2). Presence of CBFA1 or BMP‐2 protein in cell extract also was detected by Western blotting with CBFA1 or BMP‐2 antibody (Fig. 2 C1, C2). Our results demonstrated that CBFA1 and BMP‐2 protein were up‐regulated in pLEGFP‐IRES‐CBFA1 and pLEGFP‐IRES‐BMP‐2 infected cells, respectively (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2 D1, D2).

Figure 2.

NIH3T3 and DFCs stably overexpressing CBFA1 or BMP‐2. NIH3T3 and DFCs were infected by retrovirus and selected by G418. (A1, A2) Green fluorescence could be detected in the stably transduced cells but without significant morphological changes (at ×200 magnification). (B1, B2) Real‐time RT‐PCR confirmed that the transduced cells overexpressed CBFA1 or BMP‐2 gene. (C1, C2) Representative images demonstrated that the presence of CBFA1 or BMP‐2 protein in cell extract could be detected by Western blot with CBFA1 or BMP‐2 antibody. (D1, D2) Protein levels were normalized with that of β‐actin. CBFA1 and BMP‐2 were up‐regulated in pLEGFP‐IRES‐CBFA1 and pLEGFP‐IRES‐BMP‐2 infected cells, respectively. **P < 0.01 vs. NIH3T3 and NIH3T3‐EGFP, †P < 0.05 vs. DFCs and DFCs‐EGFP, ††P < 0.01 vs. DFCs and DFCs‐EGFP. Statistical significance was determined using t test.

Effects of CBFA1 or BMP‐2 overexpression on changes in osteoblast/cementoblast‐related gene expressions

Expression levels of osteoblast/cementoblast‐related genes including Col I, ALP, OPN, BSP, OC, CAP and CP23 were determined using real‐time RT‐PCR. In NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 3A), overexpression of CBFA1 up‐regulated expression levels of ALP, OC, Col I, BSP and OPN (P < 0.05), while BMP‐2 overexpression increased expression levels of ALP, OC, Col I and BSP but decreased OPN expression level (P < 0.01). Furthermore, expression level of Col I in CBFA1 overexpressing NIH3T3 cells was higher than that in BMP‐2 overexpressing NIH3T3 cells (P < 0.05), while expression levels of ALP and BSP in CBFA1 overexpressing NIH3T3 cells were lower than those in BMP‐2 overexpressing NIH3T3 cells (P < 0.01). In DFCs (Fig. 3B), expression levels of all the above‐mentioned osteoblast/cementoblast‐related genes were detected. Furthermore, overexpression of CBFA1 enhanced the expression levels of BSP, OPN, Col I, CAP and CP23 (P < 0.05), while overexpression of BMP‐2 only enhanced the expression level of CP23 (P < 0.01). In contrast, both CBFA1 and BMP‐2 overexpression inhibited expression of ALP (P < 0.01), with the inhibitory effect more prominent in CBFA1 overexpressing DFCs than in BMP‐2 overexpressing DFCs (P < 0.01).

Figure 3.

Effects of CBFA1 or BMP‐2 overexpression on osteoblast/cementoblast‐related gene expressions. Total RNA was isolated from NIH3T3, DFCs and the cells infected with pLEGFP‐N1, pLEGFP‐IRES‐CBFA1 and pLEGFP‐IRES‐BMP‐2. Real‐time RT‐PCR was performed to compare the effects of CBFA1 or BMP‐2 overexpression on osteoblast/cementoblast‐related gene expressions, including Col I, ALP, OPN, BSP, OC, CAP and CP23. All values were normalized with β‐actin levels and the data were presented as the mean ± SE for three experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. NIH3T3 and NIH3T3‐EGFP, **P < 0.01 vs. NIH3T3 and NIH3T3‐EGFP, †P < 0.05 vs. NIH3T3‐BMP‐2, ††P < 0.01 vs. NIH3T3‐BMP‐2, §P < 0.05 vs. DFCs and DFCs‐EGFP, §§P < 0.01 vs. DFCs and DFCs‐EGFP, ‡‡P < 0.01 vs. DFCs‐BMP‐2. Statistical significance was determined using t test.

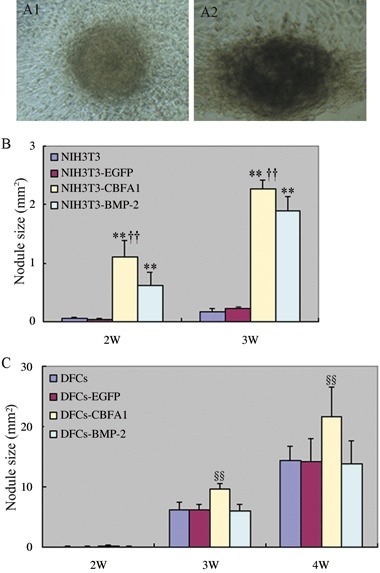

Effects of CBFA1 or BMP‐2 overexpression on mineralization

In vitro mineral nodule formation assay was performed to determine whether CBFA1 or BMP‐2 overexpression would affect in vitro mineralization. In NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 4B), both CBFA1 and BMP‐2 overexpression induced formation of mineral nodules, but more mineral nodules were detected in CBFA1 overexpressing cells than in BMP‐2 overexpressing cells (P < 0.01). In DFCs (Fig. 4C), overexpression of CBFA1 enhanced in vitro mineralization, as indicated by the larger size of mineral nodules formed in CBFA1 overexpressing DFCs than in control DFCs (P < 0.01). In contrast, there was no significant difference in mineral nodule formation between BMP‐2 overexpressing DFCs and control DFCs (P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of CBFA1 or BMP‐2 overexpression on mineral nodule formation. Cells were cultured in mineralizing media and von Kossa staining was performed to evaluate the mineral nodule formation on week 2, 3, 4. The nodules were microphotographed with Olympus camera (×100 magnification) (A1, A2) and the area covered by mineral nodules in each well was determined. The data were presented as the mean ± SE for three experiments. **P < 0.01 vs. NIH3T3 and NIH3T3‐EGFP, ††P < 0.01 vs. NIH3T3‐BMP‐2, §§P < 0.01 vs. DFCs, DFCs‐EGFP and DFCs‐BMP‐2. Statistical significance was determined using t test.

Discussion

The attraction of using local gene therapy to induce repair and formation of bone and periodontium is that genes can be delivered to the appropriate anatomical site, and duration of protein expression can be determined by selecting proper vector and/or promoter (29). Retroviruses can integrate their genes efficiently into the genome of target cells and provide long‐term expression of the transgenes (30). In this study, retroviral strategies were adopted to transfer CBFA1 or BMP‐2 into NIH3T3 cells and DFCs cells to evaluate their effects on osteoblast/cementoblast‐related gene expression profiles. Our data indicated that overexpression of CBFA1 enhanced osteoblast/cementoblast‐related gene expressions and promoted in vitro mineral nodule formation in both NIH3T3s and DFCs. Overexpression of BMP‐2 also enhanced gene expression levels and promoted in vitro mineralization in NIH3T3 cells, but failed to show such effects in DFCs.

CBFA1 is the principal osteogenic master gene during bone formation. Studies have indicated that CBFA1 is a positive regulator that up‐regulates expression levels of bone matrix genes such as Col I, OPN, BSP and OC in mesenchymal cells and non‐osteoblast cells (17, 31, 32, 33, 34). Consistent with these previous findings, our results demonstrated that CBFA1 up‐regulated expression levels of Col I, OPN, BSP and OC. CBFA1 also increased expression levels of CAP and CP23, which are both putative markers for cementoblasts. We speculated that overexpression of CBFA1 might induce NIH3T3/DFCs to differentiate towards osteoblast/cementoblasts by up‐regulating osteoblast/cementoblast‐related genes.

BMP‐2 induces expression of numerous transcription factors, which constitute a network of activities and molecular switches for bone development and osteoblast differentiation (35, 36, 37); CBFA1 is among these transcriptional regulators. BMP‐2 has been reported to increase CBFA1 mRNA level in several immortalized cell lines, such as human bone marrow stromal cells (38), C2C12 cells (39) and 2T3 cells (40), and, therefore, promote these cells to differentiate along the osteoblastic pathway. Our results also demonstrated that in NIH3T3 cells, BMP‐2 enhanced CBFA1 and other osteoblast‐related gene expression levels. However, in our study no changes in expression levels of these osteoblast‐related genes were detected in BMP‐2 overexpressing DFCs. This result was at variance from some previous findings that have shown that BMP‐2 induced osteoblast differentiation of DFCs, as reflected by enhanced Cbfal, BSP and OC mRNA expressions and increasing mineralization formation (41, 42). BMP‐2 exerts its effects through specific receptors on the cell surface by binding to them receptors and interacting with cytoplasmic effector molecules to initiate a complex cascade of intracellular events leading to alteration in gene function (35, 43). In these previous reports, researchers achieved their results by treating DFCs with BMP‐2 protein (41, 42), while in our study the DFCs were infected with retroviral constructs containing BMP‐2 cDNA instead of BMP‐2 protein treatment. Although our G418 selection results demonstrated that the BMP‐2 gene was stably integrated into the genome of DFCs, concentration of BMP‐2 protein secreted by infected DFCs may not be high enough to induce significant changes in gene expression levels. Our results indicated that using retroviral gene transfer strategy CBFA1‐induced changes in osteoblast‐related gene expression levels and in vitro mineralization were more prominent than those induced by BMP‐2.

In addition to these osteoblast‐related genes, CBFA1 overexpression in DFCs also enhanced expression levels of cementoblast‐related genes including CAP and CP23, while overexpression of BMP‐2 only enhanced expression level of CP23. Although BMP‐2 has been used to promote bone and periodontal regeneration (44, 45), it has been reported that BMP‐2 does not have a significant effect on cementum regeneration (46). It has also been reported that BMP‐2 inhibits differentiation and mineralization of cementoblasts in vitro (47). Among the BMPs/OPs family, BMP‐7/OP‐1 have also been approved by the FDA as osteo‐inductive materials for human clinical use (15). BMP‐7/OP‐1 OsigraftTM (Stryker Biotech, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) was approved for long bone fractures and as an alternative to autografts in patients requiring posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion (15). It has been reported that single application of rhOP‐1 preferentially induces cementogenesis on denuded root surfaces in primates (48, 49) and rhOP‐1 showed higher ability to induce cementogenesis when compared with rhBMP‐2 (50). Our results, which demonstrated that cementoblast‐related gene expression changes induced by BMP‐2 overexpression were less prominent than those induced by CBFA1 overexpression, also indicated that effects of BMP‐2 on cementogenesis were relatively mild. Considering that BMP‐7/OP‐1 plays more important roles in cementogenesis than BMP‐2, further studies regarding this growth factor are necessary.

In vitro mineralization assay demonstrated that in NIH3T3 cells, both CBFA1 and BMP‐2 overexpression induced mineral nodule formation. Moreover, more mineral nodules were detected in CBFA1 overexpressing NIH3T3 cells than in BMP‐2 overexpressing NIH3T3 cells. CBFA1 overexpression in DFCs also enhanced mineral nodule formation, but no changes in mineral nodule formation were detected in BMP‐2 overexpressing DFCs. Based on our findings that CBFA1 overexpression increased expression levels of OPN and Col I and promoted mineral nodule formation more efficiently than BMP‐2 overexpression in both NIH3T3s and DFCs, we assume that OPN and Col I might be more important to the mineralization process.

In conclusion, our investigation has indicated that CBFA1 enhanced expression levels of osteoblast/cementoblast‐related genes and promoted mineral nodule formation more efficiently than BMP‐2 in both NIH3T3 cells and DFCs. The results suggested that CBFA1 might be more important than BMP‐2 on up‐regulation of osteoblast/cementoblast‐related gene expressions using the gene transfer method. Based on the fact that BMP‐7/OP‐1 is more important in cementogenesis than BMP‐2, we will include this growth factor in our future studies on cementogenesis.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Doctoral Foundation of China (20050422044).

K. Pan and S. Yan contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1. Melcher AH (1976) On the repair potential of the periodontal tissues. J. Periodontol. 47, 256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kao RT, Conte G, Nishimine D, Dault S (2005) Tissue engineering for periodontal regeneration. J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 33, 205–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giannobile WV (1996) Periodontal tissue engineering by growth factors. Bone 19, 23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kaigler D, Cirelli JA, Giannobile WV (2006) Growth factor delivery for oral and periodontal tissue engineering. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 3, 647–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tu Q, Zhang J, James L, Dickson J, Tang J, Yang P et al. (2007) CBFA1/Runx2‐deficiency delays bone wound healing and locally delivered CBFA1/Runx2 promotes bone repair in animal models. Wound Repair Regen. 15, 404–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lekic P, Sodek J, McCulloch CAG (1996) Osteopontin and bone sialoprotein expression in regenerating rat periodontal ligament and alveolar bone. Anat. Rec. 244, 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bosshardt DD, Degen T, Lang NP (2005) Sequence of protein expression of bone sialoprotein and osteopontin at the developing interface between repair cementum and dentin in human deciduous teeth. Cell Tissue Res. 320, 399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Urist MR (1965) Bone: formation by autoinduction. Science 150, 893–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wozney JM, Rosen V, Celeste AJ, Mitsock LM, Whitters MJ, Kriz RW et al. (1988) Novel regulators of bone formation: molecular clones and activities. Science 242, 1528–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Celeste AJ, Iannazzi JM, Taylor JA, Hewick RC, Rosen V, Wang EA et al. (1990) Identification of transforming growth factor β family members present in bone‐inductive protein purified from bovine bone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 9843–9847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reddi AH (2001) Bone morphogenetic proteins: from basic science to clinical applications. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 83‐A Suppl. 1, S1–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Friedlaender GE, Perry CR, Cole JD, Cook SD, Cierny G, Muschler GF et al. (2001) Osteogenic protein‐1 (bone morphogenetic protein‐7) in the treatment of tibial nonunions. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 83‐A Suppl. 1, S118–S151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Govender S, Csimma C, Genant HK, Valentin‐Opran A, Amit Y, Arbel R et al. BMP‐2 Evaluation in Surgery for Tibial Trauma (BESTT) Study Group (2002) Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein‐2 for treatment of open tibial fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 84‐A, 2123–2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kang Q, Sun MH, Cheng H, Peng Y, Montag AG, Deyrup AT et al. (2004) Characterization of the distinct orthotopic bone‐forming activity of 14 BMPs using recombinant adenovirus‐mediated gene delivery. Gene Ther. 11, 1312–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bessa PC, Casal M, Reis RL (2008) Bone morphogenetic proteins in tissue engineering: the road from laboratory to clinic, part II (BMP delivery). J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2, 81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McKay WF, Peckham SM, Badura JM (2007) A comprehensive clinical review of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein‐2 (INFUSE Bone Graft). Int. Orthop. 31, 729–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ducy P, Zhang R, Geoffroy V, Ridall AL, Karsenty G (1997) Osf2/CBFA1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell 89, 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stein GS, Lian JB, Van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Montecino M, Javed A et al. (2004) Runx2 control of organization, assembly and activity of the regulatory machinery for skeletal gene expression. Oncogene 23, 4315–4329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mundlos S, Otto F, Mundlos C, Mulliken JB, Aylsworth AS, Albright S et al. (1997) Mutations involving the transcription factor CBFA1 cause cleidocranial dysplasia. Cell 89, 773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ducy P, Starbuck M, Priemel M, Shen J, Pinero G, Geoffroy V et al. (1999) A CBFA1‐dependent genetic pathway controls bone formation beyond embryonic development. Genes Dev. 13, 1025–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. D'Souza RN, Aberg T, Gaikwad J, Cavender A, Owen M, Karsenty G et al. (1999) CBFA1 is required for epithelial–mesenchymal interactions regulating tooth development in mice. Development 126, 2911–2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hitchin AD (1975) Cementum and other root abnormalities of permanent teeth in cleidocranial dysostosis. Br. Dent. J. 139, 313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jensen BL, Kreiborg S (1990) Development of the dentition in cleidocranial dysplasia. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 19, 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baum BJ, Kok M, Tran SD, Yamano S (2002) The impact of gene therapy on dentistry: a revisiting after six years. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 133, 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wise GE, Lin F, Fan W (1992) Culture and characterization of dental follicle cells from rat molars. Cell Tissue Res. 267, 483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thirunavukkarasu K, Mahajan M, McLarren KW, Stifani S, Karsenty G (1998) Two domains unique to osteoblast‐specific transcription factor Osf2/CBFA1 contribute to its transactivation function and its inability to heterodimerize with Cbfβ. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 4197–4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kwon YJ, Huang G, Anderson WF, Peng CA, Yu H (2003) Determination of infectious retrovirus concentration from colony‐forming assay with quantitative analysis. J. Virol. 77, 5712–5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Puchtler H, Meloan SN (1978) Demonstration of phosphates in calcium deposits: a modification of von Kossa's reaction. Histochemistry 56, 177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mulligan RC (1993) The basic science of gene therapy. Science 260, 926–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Limon A, Briones J, Puig T, Carmona M, Fornas O, Cancelas AJ et al. (1997) High‐titer retroviral vectors containing the enhanced green fluorescent protein gene for efficient expression in hematopoietic cells. Blood 90, 3316–3321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Banerjee C, McCabe LR, Choi JY, Hiebert SW, Stein JL, Stein GS et al. (1997) Runt homology domain proteins in osteoblast differentiation: AML3/CBFA1 is a major component of a bone‐specific complex. J. Cell. Biochem. 66, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harada H, Tagashira S, Fujiwara M, Ogawa S, Katsumata T, Yamaguchi A et al. (1999) CBFA1 isoforms exert functional differences in osteoblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 6972–6978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee KS, Kim HJ, Li QL, Chi XZ, Ueta C, Komori T et al. (2000) Runx2 is a common target of transforming growth factor 1 and bone morphogenetic protein 2, and cooperation between Runx2 and Smad5 induces osteoblast‐specific gene expression in the pluripotent mesenchymal precursor cell line C2C12. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 8783–8792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Prince M, Banerjee C, Javed A, Green J, Lian JB, Stein GS et al. (2001) Expression and regulation of Runx2/CBFA1 and osteoblast phenotypic markers during the growth and differentiation of human osteoblasts. J. Cell. Biochem. 80, 424–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Canalis E, Economides AN, Gazzerro E (2003) Bone morphogenetic proteins, their antagonists, and the skeleton. Endocr. Rev. 24, 218–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR (2004) Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors 22, 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kobayashi T, Kronenberg H (2005) Minireview: transcriptional regulation in development of bone. Endocrinology 146, 1012–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gori F, Thomas T, Hicok KC, Spelsberg TC, Riggs BL (1999) Differentiation of human marrow stromal precursor cells: bone morphogenetic protein‐2 increases OSF2/CBFA1, enhances osteoblast commitment, and inhibits late adipocyte maturation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 14, 1522–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee MH, Javed A, Kim HJ, Shin HI, Gutierrez S, Choi JY et al. (1999) Transient upregulation of CBFA1 in response to bone morphogenetic protein‐2 and transforming growth factor beta1 in C2C12 myogenic cells coincides with suppression of the myogenic phenotype but is not sufficient for osteoblast differentiation. J. Cell. Biochem. 73, 114–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen D, Ji X, Harris MA, Feng JQ, Karsenty G, Celeste AJ et al. (1998) Differential roles for bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) receptor type IB and IA in differentiation and specification of mesenchymal precursor cells to osteoblast and adipocyte lineages. J. Cell Biol. 142, 295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhao M, Xiao G, Berry JE, Franceschi RT, Reddi A, Somerman MJ (2002) Bone morphogenetic protein 2 induces dental follicle cells to differentiate toward a cementoblast/osteoblast phenotype. J. Bone Miner. Res. 17, 1441–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kémoun P, Laurencin‐Dalicieux S, Rue J, Farges JC, Gennero I, Conte‐Auriol F et al. (2007) Human dental follicle cells acquire cementoblast features under stimulation by BMP‐2/‐7 and enamel matrix derivatives (EMD) in vitro . Cell Tissue Res. 329, 283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Miyazono K, Maeda S, Imamura T (2005) BMP receptor signaling: transcriptional targets, regulation of signals, and signaling cross‐talk. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16, 251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kinoshita A, Oda S, Takahashi K, Yokota S, Ishikawa I (1997) Periodontal regeneration by application of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein‐2 to horizontal circumferential defects created by experimental periodontitis in beagle dogs. J. Periodontol. 68, 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sigurdsson TJ, Lee MB, Kubota K, Turek TJ, Wozney JM, Wikesjö UME (1995) Periodontal repair in dogs: recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein‐2 significantly enhances periodontal regeneration. J. Periodontol. 66, 131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Choi SH, Kim CK, Cho KS, Huh JS, Sorensen RG, Wozney JM et al. (2002) Effect of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein‐2/absorbable collagen sponge (rhBMP‐2/ACS) on healing in 3‐wall intrabony defects in dogs. J. Periodontol. 73, 63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhao M, Berry JE, Somerman MJ (2003) Bone morphogenetic protein‐2 inhibits differentiation and mineralization of cementoblasts in vitro . J. Dent. Res. 82, 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ripamonti U (1996) Induction of cementogenesis and periodontal ligament regeneration by bone morphogenetic proteins In: Lindholm TS, ed. Bone Morphogenetic Proteins: Biology, Biochemistry and Reconstructive Surgery, pp. 189–198. Austin, TX: RG Landes Company. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ripamonti U, Heliotis M, Rueger DC, Sampath TK (1996) Induction of cementogenesis by recombinant human osteogenic protein‐1 (hOP‐1/BMP‐7) in the baboon. Arch. Oral Biol. 41, 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ripamonti U, Crooks J, Petit J‐C, Rueger DC (2001) Periodontal tissue regeneration by combined applications of recombinant human osteogenic protein‐1 and bone morphogenetic protein‐2. A pilot study in Chacma baboons (Papio ursinus ). Eur J. Oral Sci. 109, 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]