Abstract

Syntrophins are a family of 59 kDa peripheral membrane‐associated adapter proteins, containing multiple protein‐protein and protein‐lipid interaction domains. The syntrophin family consists of five isoforms that exhibit specific tissue distribution, distinct sub‐cellular localization and unique expression patterns implying their diverse functional roles. These syntrophin isoforms form multiple functional protein complexes and ensure proper localization of signalling proteins and their binding partners to specific membrane domains and provide appropriate spatiotemporal regulation of signalling pathways. Syntrophins consist of two PH domains, a PDZ domain and a conserved SU domain. The PH1 domain is split by the PDZ domain. The PH2 and the SU domain are involved in the interaction between syntrophin and the dystrophin‐glycoprotein complex (DGC). Syntrophins recruit various signalling proteins to DGC and link extracellular matrix to internal signalling apparatus via DGC. The different domains of the syntrophin isoforms are responsible for modulation of cytoskeleton. Syntrophins associate with cytoskeletal proteins and lead to various cellular responses by modulating the cytoskeleton. Syntrophins are involved in many physiological processes which involve cytoskeletal reorganization like insulin secretion, blood pressure regulation, myogenesis, cell migration, formation and retraction of focal adhesions. Syntrophins have been implicated in various pathologies like Alzheimer’s disease, muscular dystrophy, cancer. Their role in cytoskeletal organization and modulation makes them perfect candidates for further studies in various cancers and other ailments that involve cytoskeletal modulation. The role of syntrophins in cytoskeletal organization and modulation has not yet been comprehensively reviewed till now. This review focuses on syntrophins and highlights their role in cytoskeletal organization, modulation and dynamics via its involvement in different cell signalling networks.

Keywords: Actin, cancer, cell migration, cell signalling, cytoskeleton, syntrophin

1. INTRODUCTION

Syntrophins are a heterogeneous group of membrane‐associated adaptor proteins, originally identified in the post‐synaptic membrane of torpedo electric organ.1 Syntrophins act as scaffolding proteins containing multiple protein‐protein and protein‐lipid interaction domains, interacting with various signalling molecules and kinases like ion channels,2, 3 aquaporin4 (AQP4),4, 5 ankyrin repeat‐rich membrane spanning (ARMS) protein,6 α1D‐adrenergic receptor,7 growth factor receptor bound 2 (Grb2),8 phosphoinositides,9, 10 microtubule‐associated serine/threonine kinase (MAST),11 syntrophin‐associated serine/threonine kinase (SAST),12 diacylglycerol kinase‐ζ,13 stress‐activated protein kinase (SAPK).14 Syntrophins, thus, form multiple functional protein complexes, ensuring proper localization of signalling proteins and their binding partners to specific membrane domains and providing appropriate spatiotemporal regulation of signalling pathways. Interaction of syntrophins with multiple signalling molecules is mediated by two PH domains, a PDZ domain and a conserved SU domain. The PH2 domain and the SU domain are involved in the interaction between syntrophin and the dystrophin‐glycoprotein complex (DGC). Syntrophin recruits signalling proteins to DGC, thus linking extracellular matrix to internal signalling apparatus via DGC.

The different domains of syntrophin are crucial for cytoskeletal dynamics as well as for signalling. Syntrophins associate with various cytoskeletal proteins (like actin, intermediate filaments and microtubules) within the cell and induce diverse cellular responses by modulating cell cytoskeleton. Syntrophins are involved in key physiological processes which involve cytoskeletal reorganization like insulin secretion, blood pressure regulation, myogenesis and cell migration.15, 16, 17 In pancreatic β‐cells, the PDZ domain of β2‐syntrophin regulates the release of insulin and helps in maintaining the blood glucose level. When the protein is phosphorylated on ser90, it activates actin filaments to clamp the secretory insulin granules and inhibits the release of insulin from cells. When Cdk5 phosphorylates the β2‐syntrophin on ser75 near the PDZ domain, it decreases its binding to insulin granules and increases its motility and exocytosis.17, 18 α‐1 syntrophin has a role in myoblast differentiation in early stages of muscle development. It has been found that α‐1 syntrophin in association with histone methyltransferase MLL5 increases expression of myogenin, a key regulatory factor of muscle differentiation, in myoblasts.16

Syntrophins have a pivotal role in cell migration and are involved in formation and retraction of focal adhesion. The PH1 domain of α‐1 syntrophin binds to the phosphoinositol‐4,5‐bisphosphate (Ptdins(4,5)P2) which regulates signalling proteins crucial for migration.19 Phosphatidylinositol phosphate 5 kinase (PTEN) synthesizes Ptdins(4,5)P2 at membrane ruffles inducing actin polymerization and focal adhesion formation at these sites.20, 21, 22 In skeletal muscles, α‐1 syntrophin links calcium signalling to DGC via heterotrimeric G‐protein(Gαβγ). The PDZ domain of α‐1 syntrophin binds to Gβγ subunit of heterotrimeric G‐protein (Gαβγ) in presence laminin. This interaction decreases active Gα subunit and inhibits Ca2+ influx through calcium channels. However, in absence of laminin‐dystroglycan complex, Gα subunit gets activated and Gβγ subunits dissociate from α‐1 syntrophin leading to dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) mediated Ca2+ influx in skeletal muscles.23, 24, 25 The increase in intracellular Ca2+ ion concentration activates calcium‐regulated enzymes like calcineurin (phosphatase) and calpain (protease) which mediate focal adhesion disassembly.26, 27, 28, 29, 30 In presence of calcium, the SU domain of syntrophin interacts with calmodulin and plasma membrane Ca2+/calmodulin dependent ATPase (PMCA).31, 32 Syntrophins are also phosphorylated by calcium‐calmodulin‐dependent kinase ΙΙ (CAMK ΙΙ) which is required for vascular smooth muscle cell migration.33, 34 Syntrophins, thus, help in the retraction of tail end at the trailing edge of migrating cell by inducing focal adhesion disassembly in a calcium‐dependent manner. The Syntrophin scaffold has been implicated in the pathophysiology of various diseases including brain edema,35, 36 muscular dystrophy,9, 37, 38, 39 long QT syndrome40 and cancer.38, 41 Owing to the importance of syntrophins in cell physiology and disease pathology, in this review we have discussed in detail the role of syntrophin in cytoskeletal organization and remodelling.

2. THE LOCALIZATION AND STRUCTURE OF SYNTROPHIN PROTEIN FAMILY

Syntrophins are a multigene family of cytoplasmic 59 kDa peripheral membrane scaffolding adapter proteins, containing multiple protein‐protein interaction domains. The syntrophin family consists of five different homologous isoforms (α‐1, β‐1, β‐2, γ‐1 and γ‐2) that exhibit specific tissue distribution, distinct sub‐cellular localization and unique expression patterns implying their diverse functional roles.42, 43, 44, 45 α‐1 syntrophin shows predominant expression in skeletal and cardiac muscles, distributed over entire sarcolemma and throughout folds of the neuromuscular junction. β‐1 and β‐2 syntrophins are ubiquitously expressed in different tissues including liver, kidney, brain, testis, skeletal muscles and neuromuscular junction. The distribution of β syntrophin is mainly restricted to neuromuscular junction folds.46, 47 γ‐1 and γ‐2 syntrophins show strong expression in brain, central nervous system (CNS) and testis, localized to endoplasmic reticulum and sarcolemma.48 The subcellular localizations of the various syntrophin isoforms are stringently regulated in response to their distinctive functional roles within cells. For example, in skeletal muscles, α‐1 syntrophin has been shown to be predominantly over the sarcolemma and throughout the folds of neuromuscular junction where they interact with membrane proteins and cytoskeletal elements providing mechanical support to sarcolemma during contractions and also provide appropriate signalling scaffold at synapses for the targeting signalling proteins like nNOS, dystrophin/utrophin to the post‐synaptic membrane increasing the efficacy of the signalling cascade at neuromuscular junction. Similarly, β‐2 syntrophin via its PDZ domains localizes to insulin secretory granules and microtubules regulating the release of insulin and microtubule organization respectively. γ‐1 and γ‐2 syntrophins regulate the subcellular localization of DGK‐ζ protein and are also present at synaptic junction involved in synaptic functions of cell (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characterization of Syntrophin protein family isoforms

| Syntrophin protein family | |||||

| α‐1 Syntrophin | β‐1 Syntrophin | β‐2 Syntrophin | γ‐1 Syntrophin | γ‐2 Syntrophin | |

| Chromosome location | 20q11.21 | 8q24.12 | 16q22.1 | 8q11.21 | 2p25.3 |

| Number of exons | 9 | 8 | 7 | 19 | 17 |

| Number of amino acids | 505 | 538 | 540 | 517 | 539 |

| Molecular weight, kDa | 55.5 | 59.1 | 59.4 | 56.8 | 59.2 |

| Tissue specificity | Ubiquitous high expression in skeletal and cardiac muscles | Ubiquitous expression in different tissues | Ubiquitous expression in different tissues | Exclusively expressed in neurons of brain and CNS | Brain, CNS and testis |

| Subcellular localization and interacting domains | Sarcolemma via PH2 and SU, Cell junction, Neuromuscular junction via PH1 and PDZ, Cytoskeleton via PH and SU | Plasma membrane via PH2 and SU, Neuromuscular junction folds via PH1 and PDZ, Synapse via PDZ, Cell junction, Cytoskeleton via PH and SU | Plasma membrane via PH2 and SU, Microtubules via PH2 and PDZ, Focal adhesion via PDZ and SU, Synapse via PDZ, Cytoplasmic vesicle via PDZ | Nucleus, E.R, Cytoskeleton via PH and SU, Plasma membrane via PH2 and SU | Cytoskeleton via PH and SU, E.R, Cytoplasmic side of Sarcolemma via PH2 and SU, Membrane proteins via PDZ |

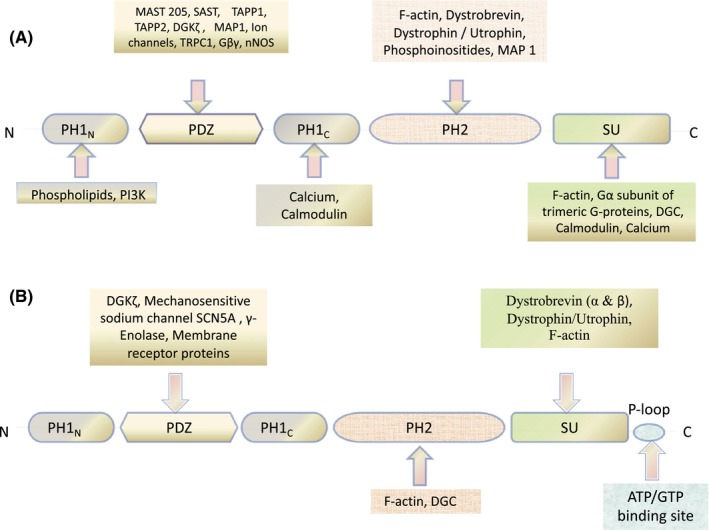

All the members of the syntrophin protein family share similar domain organization, containing two pleckstrin homology (PH1 and PH2) domains at amino‐terminus, a single PDZ domain and highly conserved domain unique to syntrophin at the carboxyl terminus. The PH domains are modules of 120 amino acids found in various signalling and cytoskeletal proteins (like β‐spectrin, Phospholipase C‐γ etc) playing diverse roles in signal transduction and cytoskeletal organization.49, 50 The N‐terminal PH1 domain of syntrophins dissociates into two halves (PHN and PHC) due to the intrusion of 80 amino acid long (Post‐Synaptic Density Protein‐75, Drosophila Discs Large Protein, and the Zona Occludens Protein 1) PDZ domain. Biochemical and structural studies on α‐1 syntrophin demonstrated that the split PH domain enfolds into canonical PH domain with or without the PDZ domain embedded.51, 52 The C‐terminal PH2 domain exists as an intact PH domain; PDZ domain insertion does not split it into two halves. The Syntrophin Unique (SU) domain is highly conserved 57 amino acid sequence present at the C‐terminal end and is specific to all syntrophin isoforms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Common Domain organization of Syntrophin Protein Family and their interaction with various signalling and structural proteins regulating cytoskeletal dynamics. A, α and β Syntrophin. B, γ Syntrophin

3. SYNTROPHINS IN THE DGC NETWORK

All five isoforms of syntrophin have a role to play in cytoskeletal organization and maintenance. Different domains of syntrophins are important for cytoskeletal dynamics as well as signal transduction. Since none of these domains contains any intrinsic enzyme activity, syntrophins are therefore thought to function as adaptors that serve to target their binding partners to specific locations on the cell membrane and localize them for signal transduction46. Syntrophins interact with dystrophin‐glycoprotein complex (DGC) primarily via its PH2 domain and the C‐terminal syntrophin‐specific SU domain and recruit various cytoskeletal and signalling proteins to DGC thereby providing membrane stabilization and maintaining integrity of cell membrane.42, 45, 53, 54 Dystrophin‐glycoprotein complex (DGC) is a multi‐component and multifunctional protein complex localized onto the plasma membrane, composed of extracellular, transmembrane and intracellular components, expressed in myriad tissues (muscle and non‐muscle).55, 56 Syntrophins are integral components of this complex along with dystroglycans (α and β), dystrobrevins (α), sarcoglycans (α, β, γ and δ), sarcospan, caveolin‐3 and NO synthase that are in strong association with the dystrophin, that is, the central core protein of this complex. The components of DGC serve mechanical role maintaining the structural integrity of skeletal muscle fibres by mediating interaction between extracellular matrix, transmembrane and cytoskeleton proteins. The binding of α‐dystroglycans to extracellular matrix proteins (laminin, argin, perlecan and neurexin) and dystrophin to actin filaments forms a continuous framework linking the cytoskeletal elements with peripheral membrane proteins.57, 58, 59, 60, 61 Thus, DGC acts as a strong functional link physically coupling cell cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix proteins. The anomalies in DGC have been linked with several forms of muscular dystrophies and cardiomyopathy.62, 63, 64, 66, 67 Apart from the structural role, DGC also interacts with various signalling molecules, ion channels and kinases including Grb‐2, calmodulin, neuronal nitric oxide synthase, stress‐activated protein kinase 3, diacylglycerol kinase‐ζ, muscle voltage‐gated sodium channels SkM1 and SkM2, cardiac voltage‐gated sodium channels Nav1.5, the heterotrimeric G‐protein and the TRPC1 stretch‐activated calcium channel, thereby regulating various biological processes like cell growth and survival, cytoskeletal reorganization, calcium homeostasis and cell migration.8, 14, 23, 31, 33, 68, 69, 70, 71 Association of syntrophins with different members of DGC has been reported in various studies. Syntrophins are known to interact with dystrophin, utrophin (dystrophin homolog) and dystrobrevin members of membrane‐associated cytoskeletal proteins of dystrophin family.72, 73, 74 Interaction of syntrophin with dystrophin protein family is mediated by SU domain and adjacent PH domain localized at the distal half of syntrophin. In skeletal muscle, four potential syntrophin binding sites are present in each dystrophin complex: two on dystrobrevin and two on dystrophin or utrophin.75 The presence of adjacent syntrophin binding sites in DGC complex suggests that syntrophin acts as an adaptor protein which facilitates the recruitment and organization of multiple signalling molecules together into functional complexes at plasma membrane, linking the cytoskeletal elements with the plasma membrane.76 This co‐localization increases specificity and efficiency of signalling cascade.

4. MODULATION OF CYTOSKELETAL FRAMEWORK BY THE DGC‐SYNTROPHIN SCAFFOLD

Dystrophin, 427 kDa cytoskeletal protein, member of spectrin superfamily of actin‐binding proteins, is organized into four distinct domains, an N‐terminal actin‐binding domain, a central rod region, a cysteine‐rich (CR) domain and a C‐terminal domain.77 The N‐terminal domain of dystrophin has a pair of Calponin Homology (CH) modules harbouring actin‐binding motif (ABD1) that directly binds to actin.78 ABD1 also connects the dystrophin to contractile apparatus in skeletal muscle by interacting with the costamere‐enriched intermediate filament protein cytokeratin 19 (K19).79, 80 The central rod domain composed of 24 spectrin‐like repeats (SLRs) and four hinge regions conferring it properties for shock resistance, elasticity and flexibility.81 The rod domain also bears second actin‐binding motif (ABD2) that in conjunction with ABD1 forms a strong lateral association with actin filaments.82 The CR region consists of a WW anti‐parallel β‐sheet motif containing two highly conserved tryptophan residues; two EF‐hand‐like motifs having helix‐loop‐helix fold and a ZZ module containing two zinc finger motifs.83, 84 The WW motif interacts with β‐dystroglycan and recognizes proline‐rich sequences/phosphorylated linear peptide/PPxY motif in ligand.85 The EF‐hands along with ZZ modules bind to calmodulin in a calcium‐dependent manner. The cysteine‐rich domain also binds to ankyrin and intermediate filament synemin which further strengthens the link between cytoskeleton and sarcolemma via dystrophin.86, 87 The C‐terminal region contains two α‐helical motifs (α‐helical coiled coil) interrupted by a short proline linker that is necessary for full dystrophin function and interacts with molecules with similar regions such as syntrophin, dystroglycan.88, 89, 90 Dystrophin has two syntrophin binding sites in the C‐terminal region that are flanked by coiled‐coil motifs.91 Protein overlay assays, studying the association of syntrophin with dystrophin fusion protein; outlines the syntrophin binding site on GST fused human dystrophin protein. This study confined the syntrophin binding motif to terminal 251 amino acid residues (amino acids 3447‐3481) encoded by exon 73 and 74 of dystrophin, directly upstream coiled‐coil motif.74, 91 The interaction of syntrophin with dystrophin was further confirmed in vivo using yeast two‐hybrid system.92 Utrophin, like dystrophin, engrosses in similar association with syntrophin; however, its localization is restricted to zone enriched with acetylcholine receptor in neuromuscular junction.93, 94, 95 In dystrophin/utrophin protein complex, syntrophins act as an adaptor interacting with muscle voltage‐gated sodium channels SkM1 and SkM2, cardiac voltage‐gated sodium channels Nav1.5 and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) via its PDZ domain.96, 97, 98 Syntrophins thus link voltage‐gated sodium channels to the actin cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix through dystrophin/utrophin and DGC complex.99, 100

Syntrophin proteins have also been shown to have a role in cell synapse modulated via the PDZ domain interactions with several proteins containing PDZ domains.44, 52 The SU domain is primarily responsible for linking syntrophins to the membrane via the DGC by interacting with proteins like dystrophin and utrophin.53, 72, 101, 102 There is an additional C‐terminus amino acid tail in γ‐syntrophins that encodes for a P‐loop. This P‐loop is considered to be a potential nucleotide (ATP/GTP) binding site.103, 104 γ‐syntrophins bind to the dystrophin protein in DGC via this P‐loop, and the splice variant of γ‐1 syntrophins that lack the P‐loop fail to bind dystrophin.103, 104

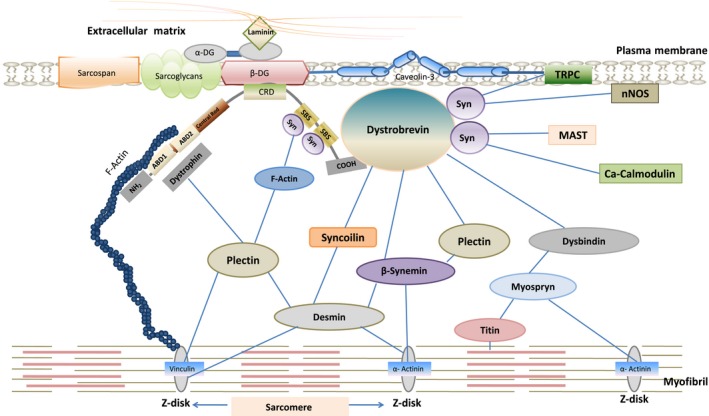

α‐dystrobrevin, 87 kDa membrane‐associated protein, a critical member of DGC that interacts directly with α‐1 syntrophin and dystrophin.1, 89 α‐dystrobrevin shows predominant expression in muscle cells (skeletal and cardiac) and in brain.105 The domain organization of this protein is similar to that of dystrophin containing EF domain with two EF‐hand motifs involved in calcium binding, a ZZ zinc finger domain binding to calmodulin, a syntrophin binding domain encoded by exon 13 and 14 (amino acids 427–480), and a coiled‐coil domain consisting of two alpha helices interacts dystrophin/utrophin. α‐dystrobrevin also has a unique C‐terminal tail containing tyrosine residues that are phosphorylated under in vivo conditions.89 α‐dystrobrevin links DGC to intermediate filament network that are the key components of cell cytoskeleton via syncoilin, β‐synemin/desmuslin, dysbindin and plectin75, 106, 107, 108 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Dystrophin‐glycoprotein complex linking the contractile apparatus to Extracellular matrix by interacting with cytoskeletal and matrix proteins

5. BRIEF OVERVIEW OF CYTOSKELETAL ORGANIZATION

The cytoskeleton is composed of interconnected meshwork of filaments: actin microfilaments, microtubules and intermediate filaments that provide structural support to cells and maintain organization of multicellular tissues. The cytoskeletal proteins also participate in signal transduction pathways integrating various intracellular and extracellular signals received at membrane and thereby facilitating distinct cellular responses to the different signals. Cytoskeleton is critical for life, as it regulates many aspects of cell physiology including cellular division, cell migration, cell morphology, cellular and tissue integrity, extracellular matrix patterning and cell polarity. The actin filaments are highly conserved indispensable building block of cytoskeleton that are constantly being remodelled between two forms of actin, globular and monomeric G‐actin and filamentous and polymeric F‐actin. This transition between the two forms of actin is tightly regulated by different signalling, scaffolding and actin‐binding proteins. Microtubules are also important components of cytoskeleton that organize the interior of cell by positioning the organelles in cytoplasm. These hollow cylindrical filaments composed of α‐ and β‐tubulin are dynamic in nature and are involved in cell division, motility, intracellular transport, cell signalling etc These are maintained by various microtubule‐associated proteins (MAP). The dynamic remodelling of cytoskeleton is crucial for most of cellular processes and malfunctioning or defective regulation of cytoskeletal proteins leads to serious consequences resulting in various human diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and a myriad of other ailments.

6. CYTOSKELETAL MODULATION BY SYNTROPHIN SIGNALPLEX

DGC and syntrophins act as a scaffold to promote the formation of a signalling complex that regulates the remodelling of the actin cytoskeleton. Syntrophins play a central role in organizing signalplex anchored to the dystrophin scaffold. The DGC provides structural stability to the cell membrane by forming a link between the actin cytoskeleton and the extracellular membrane in skeletal muscles. DGC is also pivotal in providing stability against the forces of contraction or relaxation in muscle cells.109 DGC is also involved in modulating the actin cytoskeleton by recruiting various proteins, including syntrophins, involved in actin cytoskeletal organization to the membrane.110, 111, 112 Syntrophins have been shown to have a pivotal role in executing the cytoskeletal modulating role of the DGC. The sub‐cellular localization of syntrophins in muscle cells is controlled through the cytoskeletal reorganization in these cells. In addition to this, syntrophins themselves have been characterized as actin‐binding proteins with α‐1, β‐1 and β‐2‐syntrophins been shown to bind F‐actin.113 The second PH domain and the carboxy‐terminal SU domain are primarily involved in the binding of syntrophins to actin. α‐1 syntrophin has four actin‐binding sites, three of which are present in the PH2 domain (amino acids 317‐328, 349‐357 and 497‐505) and fourth in the SU domain. The amino acid sequences at these sites are highly conserved among syntrophin isoforms. The syntrophin‐actin interaction further strengthens mechanical coupling between sarcolemma and actin filaments in costamers during muscle contraction. Syntrophins also help in the actin stabilization at the cell membrane and inhibit the actin‐activated myosin ATPase activity.113 We have recently studied the role of F‐actin in the α‐1 syntrophin mediated signalling pathway. Loss of α‐1 syntrophin tyrosine phosphorylation was observed upon actin depolymerization. This actin depolymerization mediated loss of α‐1 syntrophin phosphorylation, in turn, prevents the interaction of Rac1 with α‐syntrophin. The loss of α‐1 syntrophin‐Rac‐1 interaction further leads to a loss of Rac1 activation, which ultimately causes increased apoptosis, decreased cell migration and a decrease in ROS production. Loss of α‐1 syntrophin phosphorylation by actin depolymerization may be responsible for all these downstream effects in breast carcinoma cells.41

Pleckstrin homology (PH) domains of syntrophins have been shown to play important roles in the cytoskeletal organization.50 PH domains target several PH‐containing proteins to the cell membrane. These are involved in lipid signal transduction by functioning as lipid‐binding modules.114, 115 Along with the PH domains, the PDZ domain of syntrophins recruits several membrane proteins to the cell membrane by acting as an adaptor.46 α‐1 syntrophin interacts with a highly conserved COOH‐terminal domain of Microtubule‐Associated Protein 1 family (MAP1A, MAP1B, MAP1S) via its PH2 and PDZ domain.116 MAP1 proteins contain structurally and functionally conserved domains in their light and heavy chains that mediate heavy‐light chain interaction, binding to microtubule and F‐actin.117, 118 MAP1 proteins interact with microtubules and various signalling proteins that maintain the stability, integrity and dynamics of microtubules as well as modulate the access and activity of microtubule‐dependent motor proteins. The PDZ domain of β2‐syntrophin binds to the microtubule‐associated serine/threonine kinase‐205 (MAST205).11 This binding involves a PDZ‐PDZ domain interaction. MAP1 proteins and MAST205 kinase link the dystrophin/utrophin proteins in DGC with microtubule filaments via syntrophins, thus linking the DGC with the microtubule network.11, 116

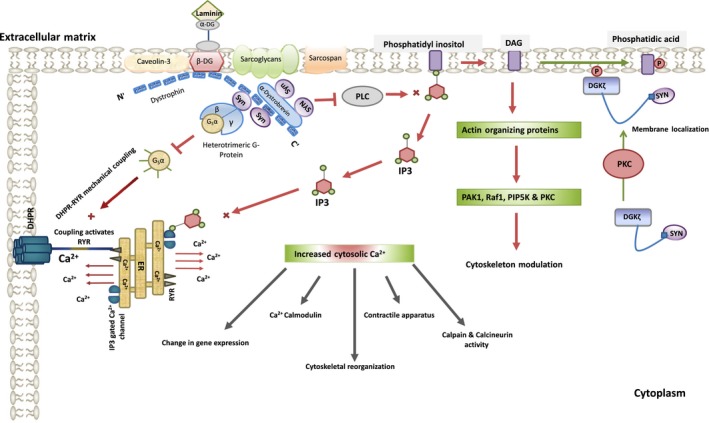

Syntrophins have also been shown to bind lipid proteins like phosphoinositol‐3‐phosphate kinase (PI3K) and diacylglycerol kinase‐ζ (DGK‐ζ) on the inner surface of the membrane. These proteins are involved in regulating the lipid signalling pathways and actin cytoskeletal organization.110, 119 The role of plasma membrane lipids in the regulation of actin dynamics is well documented.120 Diacylglycerol kinase‐ζ (DGK‐ζ) phosphorylates membrane phospholipid phosphatidylinositol yielding Phosphatidyl inositol‐4,5‐bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2). PI(4,5)P2 controls activity of various actin‐organizing proteins by increasing their association with membrane proteins and subsequently triggering the signalling pathways that promote actin polymerization.121, 122 Phospholipase C (PLC), a membrane‐bound enzyme, hydrolyses PI(4,5)P2 into diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol‐3‐phosphate (IP3), which further contribute to changes in actin dynamics. IP3 triggers the release of calcium ions from the endoplasmic reticulum, thereby, altering activity and function of many actin remodelling proteins.123 DAG, an Allosteric activator of protein kinase C (PKC), binds to the cysteine‐rich C1 domain of PKC and activates it. This DAG‐mediated PKC activation causes dramatic remodelling of the actin cytoskeleton. In addition to this, DAG has been found to be an important intermediate in phospholipids and triglyceride synthesis.110, 124 DAG also gets phosphorylated to phosphatidic acid (PA), activating various proteins involved in actin reorganization like p21 activated kinase 1 (PAK1), Raf‐1, phosphatidylinositol‐4‐phosphate‐5‐kinase (PIP5K) and PKCζ.52, 74, 125, 126, 127 PA also invigorates actin stress fibres assembly.128, 129 DGK‐ζ in association with syntrophin significantly regulates the state of actin organization. In skeletal muscles, PDZ domain of Syntrophin binds to the C‐terminal PDZ binding sequence of DGK‐ζ and forms a complex. PKC dependent phosphorylation of DGK‐ζ MARCKS homology domain regulates the translocation of this complex from cytosol to plasma membrane. The membrane localization of DGK‐ζ plays an important role in the regulation of DAG concentration and production of phospholipids at the membrane, which is critical for proper control of lipid signalling pathways regulating actin organization13 (Figure 3). γ‐1 syntrophin has been found to co‐localize with DGK‐ζ and F‐actin in the peripheral ruffles and lamellipodia in skeletal muscle cells.13, 112 Co‐localization DGK‐ζ with Rac‐1, a member Rho family of small GTPases that regulates organization actin cytoskeleton, has also been reported. DGK‐ζ in association with syntrophin forms a complex with Rac1 controlling actin reorganization in membrane ruffles and lamellipodia.110, 130

Figure 3.

Syntrophin modulating cell cytoskeleton by regulating Ca2+ signalling networks in skeletal muscles

PH domain‐containing proteins are recruited to the sites of receptor activation at the plasma membrane by signalling phosphoinositides such as phosphoinositol‐3,4‐bisphosphate [PI(3,4)P2] and phosphatidylinositol‐3,4,5‐trisphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3].112 These lipid signalling proteins tightly regulate changes in actin organization. They regulate actin cytoskeletal organization and reorganization in response to growth factor stimulation. PI3K being a component of many important signalling pathways regulates many important processes like cell survival, cell growth and motility.111, 131 PI3K also plays an important role in the production of phosphatidylinositols. These phosphatidylinositols, in turn, lead to the activation of various downstream signalling pathways by recruiting PH domain‐containing signalling proteins to the membrane. One of these PH domain‐containing proteins is TAPP1 (Tandom PH domain‐containing proteins1) adapter protein. TAPP1 is recruited to the plasma membrane of cells when PI3K is activated by growth factors like PDGF. PI‐(3,4)‐P2 interacts with TAPP1 protein and translocates it to the plasma membrane. PI(3,4)P2 binds to the TAPP1 protein via the C‐terminal PH domain of TAPP1 protein.132 Reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton is one of the responses these signalling proteins initiate at the plasma membrane after they are activated. Hence TAPP1 functions as an actin reorganizing protein. TAPP1 has been shown to interact with syntrophins and has been shown to regulate the actin cytoskeletal organization in conjunction with the syntrophins.132, 133, 134, 135, 136 The intracellular localization of a TAPP1 protein is determined by its binding to syntrophins. The C‐terminal PDZ binding sequence of TAPP1 binds to the PDZ domain of α‐1‐, β‐2‐ and γ‐1‐syntrophin.132 The signalling pathways that are initiated after the stimulation of PI3K by PDGF induce a rapid reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, and it has also been shown that various components of DGC also have a role in the regulation of actin organization in response to PDGF signalling.75, 99, 137 In addition to this, TAPP2 proteins also link PI3K signalling with cytoskeleton by interacting with β‐2‐syntrophin and utrophin.138

7. SYNTROPHIN‐ASSOCIATED PROTEINS AS MODULATORS OF CELL CYTOSKELETON

The syntrophin isoforms and the DGC in conjunction organize signalling components which lead to the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton. Up to four different syntrophin proteins associate with the DGC at a time and recruit proteins to the plasma membrane. These signalling proteins bind via the PDZ binding motifs to the circular ruffles on the membrane which are induced by PDGF.75, 139 One of the complexes comprises of the DGC, syntrophins, TAPP1 and the other downstream effectors. These protein complexes which include syntrophins stabilize the association of TAPP1 with the plasma membrane.112, 137 Therefore, syntrophins play a pivotal role in the modulation of the cytoskeleton in the cell by controlling the localization and activity of the proteins like PI3K, PI(3,4)P2 and DGK‐ζ, TAPP1 and Rac1.

α‐1‐syntrophin interacts with Grb2 via its proline‐rich regions. This interaction is important for the activation of Rho family GTPase Rac1.8 The matrix laminin on the outside is linked to Grb2 binding to α‐1‐syntrophin on the inner surface on the sarcolemma and forms a signalling pathway via ‐Sos1‐Rac1‐PAK1‐JNK, further leading to the phosphorylation of c‐jun on Ser65.140, 141 α‐dystroglycan serves as receptor for laminin and binds to LG4‐5 globular domain of laminin. The binding LG4‐5 region of laminin to α‐dystroglycan induces syntrophin phosphorylation at tyrosine residue and recruits SOS1/2 to Grb2141 (Figure 4). Rac1 protein has been shown to get immuno‐precipitated with α‐1‐syntrophin.41 Rac1, in turn, is known to control many cellular processes one of which is the actin and microtubule cytoskeletal organization.142, 143 The stability of the Rac1, PAK and RhoA signalling is important for driving the actin cytoskeleton dynamics and motility.144 There must be the highly coordinated interplay between Rac1 and RhoA activities for cells to migrate effectively.145, 146 High activity of one of these proteins warrants the low expression of the other one in order to maintain conflict‐free actin cytoskeletal organization. Rac1 activity is high at the leading edge, and RhoA activity is high at the trailing edge.142

Figure 4.

Phosphorylation of transcriptional factor c‐Jun at Ser65 by Syntrophin signalling network leads to cell cycle progression. The inhibition of the phosphorylation can lead to cell cycle defects and apoptosis

8. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Many functions of syntrophin proteins have been elucidated, and it has been seen that these membrane‐associated adaptor proteins play a major role in recruiting various signalling molecules into signalling complexes. These signalling complexes are further involved in maintaining the proper functioning of the cell. Any disruption in any of these signalling pathways can lead to disturbances that can lead to a myriad of unwanted events in cell functioning. One of the unexplored tasks vis‐à‐vis syntrophins is their role in cytoskeletal organization. Syntrophins, associated with the DGC complex, have been shown to be involved in the organization and maintenance of the cytoskeletal integrity of the cell. The components of DGC (which includes the syntrophin proteins) serve mechanical role maintaining the structural integrity of skeletal muscle fibres by mediating interaction between extracellular matrix, transmembrane and cytoskeleton proteins. Syntrophins also link voltage‐gated sodium channels to the actin cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix through dystrophin/utrophin and the DGC complex. Syntrophins play a pivotal role in the modulation of the cytoskeleton in the cell by controlling the localization and activity of the actin reorganizing proteins like PI3K, PI(3,4)P2 and DGK‐ζ, TAPP1 and Rac1. Syntrophins associate with various cytoskeletal proteins within the cells, and are, therefore, involved in key physiological processes like myogenesis, calcium homeostasis, cell migration and regulation of focal adhesions. Understanding the relationships between syntrophin proteins and cytoskeletal structures will pave the way to further the information about the functioning of syntrophins and their role in various signalling pathways. Further knowledge in this field will help us to understand how syntrophins help in the organization and maintenance of cellular cytoskeleton and other cellular events and molecular processes like cell growth, cell migration, proliferation and synapses, in addition to the understanding of various pathologies in which syntrophins are implicated like cancer, muscular dystrophy and Alzheimer’s. A thorough understanding of the functioning of syntrophins and their role in cytoskeletal organization can pave the way for the design of novel therapeutics, where then can be used as markers or these can also be potentially used as therapeutic targets which can prove helpful in the prevention of pathologies such as cancer.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was financed by grant to SSB by the Department of Science and Technology (DST) of India, No.DST/INSPIRE/04/2016/001373.

Bhat SS, Ali R, Khanday FA. Syntrophins entangled in cytoskeletal meshwork: Helping to hold it all together. Cell Prolif. 2019;52:e12562 10.1111/cpr.12562

Sahar Saleem Bhat and Roshia Ali are equally contributed.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wagner KR, Cohen JB, Huganir RL. The 87K postsynaptic membrane protein from Torpedo is a protein‐tyrosine kinase substrate homologous to dystrophin. Neuron. 1993;10(3):511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leonoudakis D, Conti LR, Anderson S, et al. Protein trafficking and anchoring complexes revealed by proteomic analysis of inward rectifier potassium channel (Kir2. x)‐associated proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(21):22331–22346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Connors NC, Adams ME, Froehner SC, Kofuji P. The potassium channel Kir4. 1 associates with the dystrophin‐glycoprotein complex via α‐syntrophin in glia. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(27):28387–28392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yokota T, Miyagoe Y, Hosaka Y, et al. Aquaporin‐4 is absent at the sarcolemma and at perivascular astrocyte endfeet in α1‐syntrophin knockout mice. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B. 2000;76(2):22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adams ME, Mueller HA, Froehner SC. In vivo requirement of the α‐syntrophin PDZ domain for the sarcolemmal localization of nNOS and aquaporin‐4. J Cell Biol. 2001;155(1):113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Luo S, Chen Y, Lai K‐O, et al. α‐Syntrophin regulates ARMS localization at the neuromuscular junction and enhances EphA4 signaling in an ARMS‐dependent manner. J Cell Biol. 2005;169(5):813–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen Z, Hague C, Hall RA, Minneman KP. Syntrophins regulate α1D‐adrenergic receptors through a PDZ domain‐mediated interaction. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(18):12414–12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oak SA, Russo K, Petrucci TC, Jarrett HW. Mouse α1‐syntrophin binding to Grb2: further evidence of a role for syntrophin in cell signaling. Biochemistry. 2001;40(37):11270–11278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wakayama Y, Inoue M, Kojima H, et al. Altered alpha1‐syntrophin expression in myofibers with Duchenne and Fukuyama muscular dystrophies. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21(1/3):23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zimmermann P. The prevalence and significance of PDZ domain–phosphoinositide interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761(8):947–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lumeng C, Phelps S, Crawford GE, Walden PD, Barald K, Chamberlain JS. Interactions between β2‐syntrophin and a family of microtubule‐associated serine/threonine kinases. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(7):611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yano R, Yap C, Yamazaki Y, et al. Sast124, a novel splice variant of syntrophin‐associated serine/threonine kinase (SAST), is specifically localized in the restricted brain regions. Neuroscience. 2003;117(2):373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hogan A, Shepherd L, Chabot J, et al. Interaction of γ1‐syntrophin with diacylglycerol kinase‐ζ regulation of nuclear localization by PDZ interactions. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(28):26526–26533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hasegawa M, Cuenda A, Spillantini MG, et al. Stress‐activated protein kinase‐3 interacts with the pdz domain of α1‐syntrophin a mechanism for specific substrate recognition. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(18):12626–12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lyssand JS, DeFino MC, Tang XB, et al. Blood pressure is regulated by an α1D‐adrenergic receptor/dystrophin signalosome. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(27):18792–18800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim MJ, Hwang SH, Lim JA, Froehner SC, Adams ME, Kim HS. Α‐syntrophin modulates myogenin expression in differentiating myoblasts. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):e15355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ort T, Voronov S, Guo J, et al. Dephosphorylation of β2‐syntrophin and Ca2+/μ‐calpain‐mediated cleavage of ICA512 upon stimulation of insulin secretion. EMBO J. 2001;20(15):4013–4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schubert S, Knoch K‐P, Ouwendijk J, et al. β2‐Syntrophin is a Cdk5 substrate that restrains the motility of insulin secretory granules. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(9):e12929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim MJ, Froehner SC, Adams ME, Kim HS. α‐Syntrophin is required for the hepatocyte growth factor‐induced migration of cultured myoblasts. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317(20):2914–2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van den Bout I, Divecha N. PIP5K‐driven PtdIns (4, 5) P2 synthesis: regulation and cellular functions. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(21):3837–3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ling K, Schill NJ, Wagoner MP, Sun Y, Anderson RA. Movin'on up: the role of PtdIns (4, 5) P2 in cell migration. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16(6):276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Raftopoulou M, Etienne‐Manneville S, Self A, Nicholls S, Hall A. Regulation of cell migration by the C2 domain of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Science. 2004;303(5661):1179–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhou YW, Oak SA, Senogles SE, Jarrett HW. Laminin‐α1 globular domains 3 and 4 induce heterotrimeric G protein binding to α‐syntrophin's PDZ domain and alter intracellular Ca2+ in muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288(2):C377–C388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Batchelor CL, Winder SJ. Sparks, signals and shock absorbers: how dystrophin loss causes muscular dystrophy. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16(4):198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson BD, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Convergent regulation of skeletal muscle Ca2+ channels by dystrophin, the actin cytoskeleton, and cAMP‐dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(11):4191–4196. 10.1073/pnas.0409695102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hendey B, Klee CB, Maxfield FR. Inhibition of neutrophil chemokinesis on vitronectin by inhibitors of calcineurin. Science. 1992;258(5080):296–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glading A, Lauffenburger DA, Wells A. Cutting to the chase: calpain proteases in cell motility. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12(1):46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Araya R, Liberona JL, Cárdenas JC, et al. Dihydropyridine receptors as voltage sensors for a depolarization‐evoked, IP3R‐mediated, slow calcium signal in skeletal muscle cells. J Gen Physiol. 2003;121(1):3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baier LJ, Permana PA, Yang X, et al. A calpain‐10 gene polymorphism is associated with reduced muscle mRNA levels and insulin resistance. J Clin Investig. 2000;106(7):R69–R73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sakuma K, Yamaguchi A. The functional role of calcineurin in hypertrophy, regeneration, and disorders of skeletal muscle. Biomed Res Int. 2010;2010:721219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Newbell BJ, Anderson JT, Jarrett HW. Ca2+‐calmodulin binding to mouse α1 syntrophin: syntrophin is also a Ca2+‐binding protein. Biochemistry. 1997;36(6):1295–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Williams JC, Armesilla AL, Mohamed TM, et al. The sarcolemmal calcium pump, α‐1 syntrophin, and neuronal nitric‐oxide synthase are parts of a macromolecular protein complex. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(33):23341–23348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Madhavan R, Jarrett HW. Calmodulin‐activated phosphorylation of dystrophin. Biochemistry. 1994;33(19):5797–5804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pfleiderer PJ, Lu KK, Crow MT, Keller RS, Singer HA. Modulation of vascular smooth muscle cell migration by calcium/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II‐δ2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286(6):C1238–C1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chu H, Huang C, Ding H, et al. Aquaporin‐4 and cerebrovascular diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(8):1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zador Z, Stiver S, Wang V, Manley GT. Role of aquaporin-4 in cerebral edema and stroke. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;159–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Adams ME, Kramarcy N, Krall SP, et al. Absence of α‐syntrophin leads to structurally aberrant neuromuscular synapses deficient in utrophin. J Cell Biol. 2000;150(6):1385–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Acharyya S, Butchbach ME, Sahenk Z, et al. Dystrophin glycoprotein complex dysfunction: a regulatory link between muscular dystrophy and cancer cachexia. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(5):421–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hosaka Y, Yokota T, Miyagoe‐Suzuki Y, et al. α1‐Syntrophin–deficient skeletal muscle exhibits hypertrophy and aberrant formation of neuromuscular junctions during regeneration. J Cell Biol. 2002;158(6):1097–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ueda K, Valdivia C, Medeiros‐Domingo A, et al. Syntrophin mutation associated with long QT syndrome through activation of the nNOS–SCN5A macromolecular complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(27):9355–9360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bhat SS, Parray AA, Mushtaq U, Fazili KM, Khanday FA. Actin depolymerization mediated loss of SNTA1 phosphorylation and Rac1 activity has implications on ROS production, cell migration and apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2016;21(6):737–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Adams ME, Butler MH, Dwyer TM, Peters MF, Murnane AA, Froehner SC. Two forms of mouse syntrophin, a 58 kd dystrophin‐associated protein, differ in primary structure and tissue distribution. Neuron. 1993;11(3):531–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Adams ME, Dwyer TM, Dowler LL, White RA, Froehner SC. Mouse α1‐ and β2‐syntrophin gene structure, chromosome localization, and homology with a discs large domain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(43):25859–25865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Adams ME, Kramarcy N, Fukuda T, Engel AG, Sealock R, Froehner SC. Structural abnormalities at neuromuscular synapses lacking multiple syntrophin isoforms. J Neurosci. 2004;24(46):10302–10309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ahn AH, Freener CA, Gussoni E, Yoshida M, Ozawa E, Kunkel LM. The three human syntrophin genes are expressed in diverse tissues, have distinct chromosomal locations, and each bind to dystrophin and its relatives. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(5):2724–2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Albrecht DE, Froehner SC. Syntrophins and dystrobrevins: defining the dystrophin scaffold at synapses. Neurosignals. 2002;11(3):123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Peters MF, Kramarcy NR, Sealock R, Froehner SC. Beta 2‐Syntrophin: localization at the neuromuscular junction in skeletal muscle. NeuroReport. 1994;5(13):1577–1580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Piluso G, Mirabella M, Ricci E, et al. γ1‐and γ2‐syntrophins, two novel dystrophin‐binding proteins localized in neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(21):15851–15860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lemmon MA, Ferguson KM. Signal‐dependent membrane targeting by pleckstrin homology (PH) domains. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 1):1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lemmon MA, Ferguson KM, Abrams CS. Pleckstrin homology domains and the cytoskeleton. FEBS Lett. 2002;513(1):71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wen W, Yan J, Zhang M. Structural characterization of the split pleckstrin homology domain in phospholipase C‐γ1 and its interaction with TRPC3. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(17):12060–12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yan J, Wen W, Xu W, et al. Structure of the split PH domain and distinct lipid‐binding properties of the PH–PDZ supramodule of α‐syntrophin. EMBO J. 2005;24(23):3985–3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ahn AH, Kunkel LM. Syntrophin binds to an alternatively spliced exon of dystrophin. J Cell Biol. 1995;128(3):363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ahn AH, Yoshida M, Anderson MS, et al. Cloning of human basic A1, a distinct 59‐kDa dystrophin‐associated protein encoded on chromosome 8q23‐24. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(10):4446–4450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Durbeej M, Campbell KP. Biochemical characterization of the epithelial dystroglycan complex. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(37):26609–26616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ervasti JM, Campbell KP. Membrane organization of the dystrophin‐glycoprotein complex. Cell. 1991;66(6):1121–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ibraghimov‐Beskrovnaya O, Ervasti JM, Leveille CJ, Slaughter CA, Sernett SW, Campbell KP. Primary structure of dystrophin‐associated glycoproteins linking dystrophin to the extracellular matrix. Nature. 1992;355(6362):696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rybakova IN, Ervasti JM. Dystrophin‐glycoprotein complex is monomeric and stabilizes actin filaments in vitro through a lateral association. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(45):28771–28778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rybakova IN, Patel JR, Ervasti JM. The dystrophin complex forms a mechanically strong link between the sarcolemma and costameric actin. J Cell Biol. 2000;150(5):1209–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sugita S, Saito F, Tang J, Satz J, Campbell K, Südhof TC. A stoichiometric complex of neurexins and dystroglycan in brain. J Cell Biol. 2001;154(2):435–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Weller B, Karpati G, Carpenter S. Dystrophin‐deficient mdx muscle fibers are preferentially vulnerable to necrosis induced by experimental lengthening contractions. J Neurol Sci. 1990;100(1–2):9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Barresi R, Di Blasi C, Negri T, et al. Disruption of heart sarcoglycan complex and severe cardiomyopathy caused by β sarcoglycan mutations. J Med Genet. 2000;37(2):102–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wheeler MT, Korcarz CE, Collins KA, et al. Secondary coronary artery vasospasm promotes cardiomyopathy progression. Am J Pathol. 2004;164(3):1063–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hack A, Cordier L, Shoturma D, Lam M, Sweeney H, McNally E. Muscle degeneration without mechanical injury in sarcoglycan deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(19):10723–10728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yoshida M, Ozawa E. Glycoprotein complex anchoring dystrophin to sarcolemma. J. Biochem. 1990;108:748–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Durbeej M, Cohn RD, Hrstka RF, et al. Disruption of the β‐sarcoglycan gene reveals pathogenetic complexity of limb‐girdle muscular dystrophy type 2E. Mol Cell. 2000;5(1):141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wheeler MT, Allikian MJ, Heydemann A, Hadhazy M, Zarnegar S, McNally EM. Smooth muscle cell–extrinsic vascular spasm arises from cardiomyocyte degeneration in sarcoglycan‐deficient cardiomyopathy. J Clin Investig. 2004;113(5):668–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Madhavan R, Massom LR, Jarrett HW. Calmodulin specifically binds three proteins of the dystrophin‐glycoprotein complex. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1992;185(2):753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sabourin J, Harisseh R, Harnois T, et al. Dystrophin/α1‐syntrophin scaffold regulated PLC/PKC‐dependent store‐operated calcium entry in myotubes. Cell Calcium. 2012;52(6):445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sabourin J, Lamiche C, Vandebrouck A, et al. Regulation of TRPC1 and TRPC4 cation channels requires an α1‐syntrophin‐dependent complex in skeletal mouse myotubes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(52):36248–36261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Vandebrouck A, Sabourin J, Rivet J, et al. Regulation of capacitative calcium entries by α1‐syntrophin: association of TRPC1 with dystrophin complex and the PDZ domain of α1‐syntrophin. FASEB J. 2007;21(2):608–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kramarcy NR, Vidal A, Froehner SC, Sealock R. Association of utrophin and multiple dystrophin short forms with the mammalian M (r) 58,000 dystrophin‐associated protein (syntrophin). J Biol Chem. 1994;269(4):2870–2876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Madhavan R, Jarrett HW. Interactions between dystrophin glycoprotein complex proteins. Biochemistry. 1995;34(38):12204–12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yang B, Jung D, Rafael JA, Chamberlain JS, Campbell KP. Identification of α‐syntrophin binding to syntrophin triplet, dystrophin, and utrophin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(10):4975–4978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Newey S, Benson MA, Ponting CP, Davies KE, Blake DJ. Alternative splicing of dystrobrevin regulates the stoichiometry of syntrophin binding to the dystrophin protein complex. Curr Biol. 2000;10(20):1295–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Constantin B. Dystrophin complex functions as a scaffold for signalling proteins. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2014;1838(2):635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Koenig M, Monaco A, Kunkel L. The complete sequence of dystrophin predicts a rod‐shaped cytoskeletal protein. Cell. 1988;53(2):219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Norwood FL, Sutherland‐Smith AJ, Keep NH, Kendrick‐Jones J. The structure of the N‐terminal actin‐binding domain of human dystrophin and how mutations in this domain may cause Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophy. Structure. 2000;8(5):481–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Stone MR, O'Neill A, Catino D, Bloch RJ. Specific interaction of the actin‐binding domain of dystrophin with intermediate filaments containing keratin 19. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(9):4280–4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Stone MR, O'Neill A, Lovering RM, et al. Absence of keratin 19 in mice causes skeletal myopathy with mitochondrial and sarcolemmal reorganization. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(22):3999–4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Muthu M, Richardson KA, Sutherland‐Smith AJ. The crystal structures of dystrophin and utrophin spectrin repeats: implications for domain boundaries. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Rybakova IN, Amann KJ, Ervasti JM. A new model for the interaction of dystrophin with F‐actin. J Cell Biol. 1996;135(3):661–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hnia K, Zouiten D, Cantel S, et al. ZZ domain of dystrophin and utrophin: topology and mapping of a β‐dystroglycan interaction site. Biochem J. 2007;401(3):667–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ilsley J, Sudol M, Winder S. The interaction of dystrophin with β‐dystroglycan is regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation. Cell Signal. 2001;13(9):625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Huang X, Poy F, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Sudol M, Eck MJ. Structure of a WW domain containing fragment of dystrophin in complex with β‐dystroglycan. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2000;7(8):634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ayalon G, Davis JQ, Scotland PB, Bennett V. An ankyrin‐based mechanism for functional organization of dystrophin and dystroglycan. Cell. 2008;135(7):1189–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bhosle RC, Michele DE, Campbell KP, Li Z, Robson RM. Interactions of intermediate filament protein synemin with dystrophin and utrophin. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2006;346(3):768–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Banks GB, Judge LM, Allen JM, Chamberlain JS. The polyproline site in hinge 2 influences the functional capacity of truncated dystrophins. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(5):e1000958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Blake DJ, Tinsley JM, Davies KE, Knight AE, Winder SJ, Kendrick‐Jones J. Coiled‐coil regions in the carboxy‐terminal domains of dystrophin and related proteins: potentials for protein‐protein interactions. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20(4):133–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Carsana A, Frisso G, Tremolaterra M, et al. Analysis of dystrophin gene deletions indicates that the hinge III region of the protein correlates with disease severity. Ann Hum Genet. 2005;69(3):253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sadoulet‐Puccio HM, Rajala M, Kunkel LM. Dystrobrevin and dystrophin: an interaction through coiled‐coil motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(23):12413–12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Castelló A, Brochériou V, Chafey P, Kahn A, Gilgenkrantz H. Characterization of the dystrophin‐syntrophin interaction using the two‐hybrid system in yeast. FEBS Lett. 1996;383(1–2):124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Bewick GS, Young C, Slater C. Spatial relationships of utrophin, dystrophin, beta‐dystroglycan and beta‐spectrin to acetylcholine receptor clusters during postnatal maturation of the rat neuromuscular junction. J Neurocytol. 1996;25(7):367–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Matsumura K, Ervasti JM, Ohlendieck K, Kahl SD, Campbell KP. Association of dystrophin‐related protein with dystrophin‐associated proteins in mdx mouse muscle. Nature. 1992;360(6404):588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Tinsley JM, Blake DJ, Roche A, et al. Primary structure of dystrophin‐related protein. Nature. 1992;360(6404):591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Gee SH, Madhavan R, Levinson SR, Caldwell JH, Sealock R, Froehner SC. Interaction of muscle and brain sodium channels with multiple members of the syntrophin family of dystrophin‐associated proteins. J Neurosci. 1998;18(1):128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Schultz J, Hoffmuüller U, Krause G, et al. Specific interactions between the syntrophin PDZ domain and voltage‐gated sodium channels. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 1998;5(1):19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Brenman JE, Chao DS, Gee SH, et al. Interaction of nitric oxide synthase with the postsynaptic density protein PSD‐95 and α1‐syntrophin mediated by PDZ domains. Cell. 1996;84(5):757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Gavillet B, Rougier J‐S, Domenighetti AA, et al. Cardiac sodium channel Nav1. 5 is regulated by a multiprotein complex composed of syntrophins and dystrophin. Circ Res. 2006;99(4):407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Su Y, Edwards‐Bennett S, Bubb MR, Block ER. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by the actin cytoskeleton. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284(6):C1542–C1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kachinsky AM, Froehner SC, Milgram SL. A PDZ‐containing scaffold related to the dystrophin complex at the basolateral membrane of epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1999;145(2):391–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Suzuki A, Yoshida M, Ozawa E. Mammalian alpha 1‐and beta 1‐syntrophin bind to the alternative splice‐prone region of the dystrophin COOH terminus. J Cell Biol. 1995;128(3):373–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Alessi A, Bragg AD, Percival JM, et al. γ‐Syntrophin scaffolding is spatially and functionally distinct from that of the α/β syntrophins. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312(16):3084–3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Saraste M, Sibbald PR, Wittinghofer A. The P‐loop—a common motif in ATP‐and GTP‐binding proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15(11):430–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Blake DJ, Kröger S. The neurobiology of duchenne muscular dystrophy: learning lessons from muscle? Trends Neurosci. 2000;23(3):92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Mizuno Y, Thompson TG, Guyon JR, et al. Desmuslin, an intermediate filament protein that interacts with α‐dystrobrevin and desmin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(11):6156–6161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Poon E, Howman EV, Newey SE, Davies KE. Association of Syncoilin and Desmin linking intermediate filament proteins to the dystrophin‐associated protein complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(5):3433–3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Benson MA, Newey SE, Martin‐Rendon E, Hawkes R, Blake DJ. Dysbindin, a novel coiled‐coil‐containing protein that interacts with the dystrobrevins in muscle and brain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(26):24232–24241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Petrof BJ, Shrager JB, Stedman HH, Kelly AM, Sweeney HL. Dystrophin protects the sarcolemma from stresses developed during muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(8):3710–3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Abramovici H, Hogan AB, Obagi C, Topham MK, Gee SH. Diacylglycerol kinase‐ζ localization in skeletal muscle is regulated by phosphorylation and interaction with syntrophins. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(11):4499–4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3‐kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296(5573):1655–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Hogan A, Yakubchyk Y, Chabot J, et al. The phosphoinositol 3, 4‐bisphosphate‐binding protein TAPP1 interacts with syntrophins and regulates actin cytoskeletal organization. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(51):53717–53724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Iwata Y, Sampaolesi M, Shigekawa M, Wakabayashi S. Syntrophin is an actin‐binding protein the cellular localization of which is regulated through cytoskeletal reorganization in skeletal muscle cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83(10):555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Ferguson KM, Kavran JM, Sankaran VG, et al. Structural basis for discrimination of 3‐phosphoinositides by pleckstrin homology domains. Mol Cell. 2000;6(2):373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Kavran JM, Klein DE, Lee A, et al. Specificity and promiscuity in phosphoinositide binding by pleckstrin homology domains. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(46):30497–30508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Fuhrmann‐Stroissnigg H, Noiges R, Descovich L, et al. The light chains of microtubule‐associated proteins MAP1A and MAP1B interact with α1‐syntrophin in the central and peripheral nervous system. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e49722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Noiges R, Stroissnigg H, Trančiková A, Kalny I, Eichinger R, Propst F. Heterotypic complex formation between subunits of microtubule‐associated proteins 1A and 1B is due to interaction of conserved domains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763(10):1011–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Tögel M, Wiche G, Propst F. Novel features of the light chain of microtubule‐associated protein MAP1B: microtubule stabilization, self interaction, actin filament binding, and regulation by the heavy chain. J Cell Biol. 1998;143(3):695–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Chockalingam PS, Gee SH, Jarrett HW. Pleckstrin homology domain 1 of mouse α1‐syntrophin binds phosphatidylinositol 4, 5‐bisphosphate. Biochemistry. 1999;38(17):5596–5602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Saarikangas J, Zhao H, Lappalainen P. Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton‐plasma membrane interplay by phosphoinositides. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(1):259–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Janmey PA, Lindberg U. Cytoskeletal regulation: rich in lipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(8):658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Sechi AS, Wehland J. The actin cytoskeleton and plasma membrane connection: PtdIns (4, 5) P (2) influences cytoskeletal protein activity at the plasma membrane. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(21):3685–3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Janmey PA. Phosphoinositides and calcium as regulators of cellular actin assembly and disassembly. Annu Rev Physiol. 1994;56(1):169–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Topham MK, Bunting M, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, Blackshear PJ, Prescott SM. Protein kinase C regulates the nuclear localization of diacylglycerol kinase‐ζ. Nature. 1998;394(6694):697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Bokoch GM, Reilly AM, Daniels RH, et al. A GTPase‐independent Mechanism of p21‐activated kinase activation regulation by sphingosine and other biologically active lipids. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(14):8137–8144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Limatola C, Schaap D, Moolenaar W, Van Blitterswijk W. Phosphatidic acid activation of protein kinase C‐zeta overexpressed in COS cells: comparison with other protein kinase C isotypes and other acidic lipids. Biochem J. 1994;304(Pt 3):1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Stace CL, Ktistakis NT. Phosphatidic acid‐and phosphatidylserine‐binding proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761(8):913–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Cross MJ, Roberts S, Ridley AJ, et al. Stimulation of actin stress fibre formation mediated by activation of phospholipase D. Curr Biol. 1996;6(5):588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Komati H, Naro F, Mebarek S, et al. Phospholipase D is involved in myogenic differentiation through remodeling of actin cytoskeleton. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(3):1232–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Small JV, Stradal T, Vignal E, Rottner K. The lamellipodium: where motility begins. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12(3):112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Fang Y, Vilella‐Bach M, Bachmann R, Flanigan A, Chen J. Phosphatidic acid‐mediated mitogenic activation of mTOR signaling. Science. 2001;294(5548):1942–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Kimber WA, Trinkle‐Mulcahy L, Cheung PC, et al. Evidence that the tandem‐pleckstrin‐homology‐domain‐containing protein TAPP1 interacts with Ptd (3, 4) P2 and the multi‐PDZ‐domain‐containing protein MUPP1 in vivo. Biochem J. 2002;361(Pt 3):525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Marshall A, Niiro H, Lerner C, et al. Dual adapter for phosphotyrosine and 3‐phosphotyrosine and 3‐phosphoinositide (hDAPP1)(B cell adapter molecule of 32 kDa)(Blymphocyte adapter protein Bam32). J Exp Med. 2000;191:1319–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Marshall AJ, Krahn AK, Ma K, Duronio V, Hou S. TAPP1 and TAPP2 are targets of phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase signaling in B cells: sustained plasma membrane recruitment triggered by the B‐cell antigen receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(15):5479–5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Dowler S, Currie RA, Campbell DG, et al. Identification of pleckstrin‐homology‐domain‐containing proteins with novel phosphoinositide‐binding specificities. Biochem J. 2000;351(Pt 1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Dowler S, Currie RA, Downes CP, Alessi DR. DAPP1: a dual adaptor for phosphotyrosine and 3‐phosphoinositides. Biochem J. 1999;342(Pt 1):7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Buccione R, Orth JD, McNiven MA. Foot and mouth: podosomes, invadopodia and circular dorsal ruffles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(8):647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Costantini JL, Cheung SM, Hou S, et al. TAPP2 links phosphoinositide 3‐kinase signaling to B‐cell adhesion through interaction with the cytoskeletal protein utrophin: expression of a novel cell adhesion‐promoting complex in B‐cell leukemia. Blood. 2009;114(21):4703–4712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Peters MF, Adams ME, Froehner SC. Differential association of syntrophin pairs with the dystrophin complex. J Cell Biol. 1997;138(1):81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Oak SA, Zhou YW, Jarrett HW. Skeletal muscle signaling pathway through the dystrophin glycoprotein complex and Rac1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(41):39287–39295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Zhou YW, Thomason DB, Gullberg D, Jarrett HW. Binding of laminin α1‐chain LG4− 5 domain to α‐dystroglycan causes tyrosine phosphorylation of syntrophin to initiate Rac1 signaling. Biochemistry. 2006;45(7):2042–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Byrne KM, Monsefi N, Dawson JC, et al. Bistability in the Rac1, PAK, and RhoA signaling network drives actin cytoskeleton dynamics and cell motility switches. Cell Syst. 2016;2(1):38–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Colley NJ. Actin'up with Rac1. Science. 2000;290(5498):1902–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, et al. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302(5651):1704–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho, rac, and cdc42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia, and filopodia. Cell. 1995;81(1):53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho GTPases control polarity, protrusion, and adhesion during cell movement. J Cell Biol. 1999;144(6):1235–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]