Abstract

Abstract. The prostate gland is the site of the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men in USA and UK, accounting for one in five of new cases of male cancer. Common with many other cancer types, prostate cancer is believed to arise from a stem cell that shares characteristics with the normal stem cell. Normal prostate epithelial stem cells were recently identified and found to have a basal cell phenotype together with expression of CD133. Preliminary data have now emerged for a prostate cancer stem cell that also expresses cell surface CD133 but lacks expression of the androgen receptor. Here we examine the evidence supporting the existence of prostate cancer stem cells and discuss possible mechanisms of stem cell maintenance.

INTRODUCTION

The prostate is a walnut‐sized gland surrounding the urethra in human males. As part of the male reproductive system, its function involves production of approximately 30% of seminal fluid volume (Cunha et al. 1987) and one role of these secretions may be to provide nutrients for sperm. One of the secreted proteins is prostate specific antigen (PSA), a chymotrypsin that acts by preventing the coagulation of seminal fluid.

Prostate cancer is the most common male malignancy (excluding non‐melanomatous skin cancer) in Western societies and the second most common cause of male cancer‐related death in USA and UK, accounting for approximately 12% of all male cancer‐related deaths (Jemal et al. 2003; Cancer Research UK statistics 2005 1 ).

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is uncommon in young men but its prevalence increases sharply in men over the age of 50. Up to one in three men over 50 years of age suffer from symptoms related to BPH, and histological evidence of BPH occurs at autopsy in 90% of 80‐year‐old men. The transition zone of cells that surrounds the urethra enlarges with age in a hormonally dependent manner causing symptoms of bladder outflow obstruction. Castrated males do not develop BPH. Changes in the balance between epithelial cell division and differentiation have long been implicated in both BPH and prostate cancer (Isaacs & Coffey 1989; Bonkhoff & Remberger 1996), but until recently, there had been no evidence for the existence of stem cells in either normal or malignant prostate tissue. In common with research on stem cells in several other human tissues, there has recently been a rapid improvement in our understanding of prostate stem cells and it is now apparent that stem cells are a potentially valuable target for novel therapeutic strategies.

PROSTATE CANCER‐THE CLINICAL PROBLEM

Over 90% of prostate cancer patients with incurable disease respond to primary treatment, which consists of intervention to lower serum testosterone. Up to 90% of testosterone in adult males is produced by the Leydig cells in the male testis under the influence of luteinizing hormone (LH) produced by the hypothalamus. Ablation of testicular testosterone by orchiectomy or LH releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists, such as goserelin or leuprolide, in patients with advanced disease results in dramatic clinical response with improvement in bone pain, regression of soft tissue metastasis and steep declines in PSA seen in the majority of cases. This results from the dependency of prostate cancer cells on activation of the androgen receptor (AR) by androgenic steroids for proliferation and differentiation with loss of AR signalling following androgen withdrawal resulting in apoptosis. However, the duration of response is short (12–33 months) and in almost all patients, is followed by the emergence of a phenotype resistant to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) (known as hormone‐ or androgen‐resistant prostate cancer; HRPC) (Han et al. 2003). Despite significant clinical benefit from treatment with the chemotherapeutic agent docetaxel, patients with HRPC have a median life expectancy of less than 24 months (Tannock et al. 2004). Once patients relapse with hormone‐resistant disease, residual androgens, produced by the adrenal glands and possibly the prostate itself (Holzbeierlein et al. 2004), are thought to restore AR signalling in cells that have become ‘hypersensitive’ secondary to AR amplification (Edwards et al. 2003), mutations in the AR gene (Taplin et al. 2003), increased AR expression (Chen et al. 2004), or alterations in AR corepressor/coactivator function (Li et al. 2002). In fact, treatments that compete with residual androgens for binding to the AR, such as the anti‐androgens and oestrogens, or inhibitors of adrenal steroidogenesis, such as corticosteroids and ketoconazole, confer symptomatic benefit and PSA responses in some patients who relapse with HRPC (Oh 2002). However, response to secondary hormonal therapies is often short‐lived and no large, randomised studies have demonstrated a survival benefit with the use of these treatments (Oh 2002). Various strategies to delay the onset of hormone resistance are currently undergoing evaluation. If androgen resistance develops, in part, from adaptive cell survival mechanisms activated by androgen withdrawal, intermittent re‐exposure to androgens may prolong time to relapse. Intermittent androgen suppression (IAS) follows a cycle of reversible androgen suppression for 6 to 9 months until a PSA response is achieved, at which time treatment is withheld, allowing serum testosterone levels to rise. Treatment is restarted when PSA starts to rise again and cycles of IAS are continued until PSA fails to decline or there is other evidence of disease progression. IAS delays the onset of androgen‐independent PSA gene regulation in the LNCaP tumour model (Sato et al. 1996), but an improvement in overall or progression‐free survival in a large, randomised phase III study has yet to be demonstrated. A better understanding of the molecular changes that underlie androgen resistance is required in order to allow the development of more effective treatment strategies.

IS PROSTATE CANCER A STEM CELL DISEASE?

The Goldie–Coldman hypothesis, proposed more than 20 years ago, suggested that a small percentage of cells in a tumour harboured intrinsic characteristics that made them resistant to treatment (Goldie & Coldman 1979). The tumour stem cell theory could support this hypothesis and explain how patients with metastatic disease who show a clinical response to ADT relapse several months after starting treatment due to the survival of a small group of cells with unique characteristics, including the ability to give rise to a new population of cells with a resistant phenotype. Several theories about the origin of prostate cancer stem cells (PSCS) have been proposed, with different workers postulating them to arise from normal stem cells (Bonkhoff & Remberger 1996), transit‐amplifying cells (Verhagen et al. 1992; De Marzo et al. 1998) or de‐differentiated luminal cells (Liu et al. 1999; Nagle et al. 1987). As will be discussed, the balance of current evidence supports the first option. Normal prostate stem cells do not express AR and if PCSCs truly originate from them, one would expect PCSCs not to express AR. PCSCs would therefore not be dependent on androgenic steroids for survival and proliferation, allowing them to survive despite sudden androgen withdrawal (Bonkhoff & Remberger 1996). Tumour stem cells could then give rise to a clone of differentiated cells with characteristics that confer a survival advantage in the presence of castrate levels of androgens. The cancer stem cell (CSC) paradigm suggests that targeting differentiated cells will not achieve long‐term remission or cure unless the stem‐cell phenotype is also targeted. However, to date, CSCs remain poorly characterised and therefore the development of therapies that effectively target them has not been feasible.

CANCER STEM CELLS

Although theories proposing that cancers contained stem cells have been published over 20 years ago (Mackillop et al. 1983), until recently there has been very little proof for their existence. CSCs were first identified in the haemopoietic system where Bonnet & Dick (1997) showed that tumour‐initiating cells in human acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) shared a cell surface (CD34+ CD38−) phenotype with normal haematopoietic stem cells. Only recently, however, has it become clear that solid tumours may also contain stem cell populations and tissues in which CSCs have now been identified include the mammary gland (Al‐Hajj et al. 2004), brain (Galli et al. 2004; Hirschmann‐Jax et al. 2004; Singh et al. 2004), lung (Kim et al. 2005) and kidney (Florek et al. 2005). Evidence supporting the existence of normal stem cells in the prostate is now emerging and although there remains a paucity of direct evidence for the existence of PCSCs, this is steadily mounting.

EXPERIMENTAL EVIDENCE FOR PROSTATE STEM CELLS

Androgen‐independent stem cells

Early evidence for stem cells in the prostate came from a set of experiments involving androgen withdrawal from both human (van der Kwast et al. 1998) and rat (English et al. 1987; Evans & Chandler 1987; Verhagen et al. 1988) prostate. The epithelial component of the prostate gland consists of two cell layers, with a luminal secretory‐cell layer separated from the basement membrane by a basal layer that exhibits most of the cell proliferation and which is believed to contain the stem cells (Bonkhoff & Remberger 1996; Hudson et al. 2001). Upon castration, there is a dramatic reduction in prostate size caused by massive cell death. However, not all normal cells die, and death is largely restricted to apoptosis of the AR expressing luminal cells. The remainder of the cells can survive for long periods of time and re‐exposure to androgens leads to regeneration of a full‐sized prostate. Following these observations, the stem‐cell theory for prostate growth proposed that androgen‐independent stem cells produce androgen‐dependent, fully differentiated luminal cells via an androgen‐independent transit‐amplifying (TA) population (Isaacs & Coffey 1989). The absence of growth in androgen‐independent cells upon androgen withdrawal appears to oppose this theory. However, growth of basal cells is dependent on a complex stromal–epithelial interaction in which cell division is driven indirectly by androgens that induce growth factor production by underlying smooth muscle cells (reviewed by Hayward et al. 1997) that in turn stimulate epithelial cell growth.

Differentiation marker expression in prostate

Normal prostate

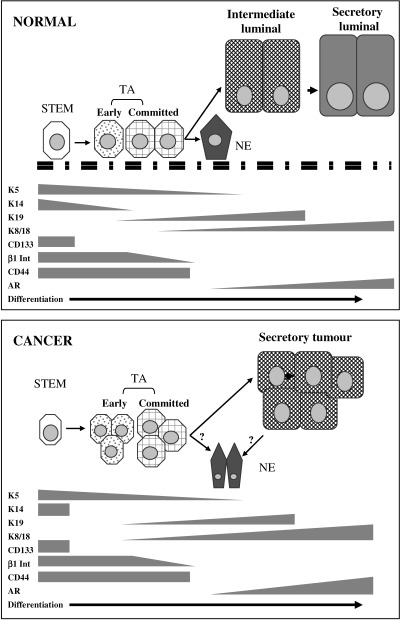

Further evidence for the stem cell hierarchy in prostate epithelium came from the study of the expression patterns of various markers of differentiation, including keratins and CD44. Basal cells express keratins (K) 5 and 14 together with CD44 (Liu et al. 1997; Alam et al. 2004) and the anti‐apoptotic protein, bcl‐2 (McDonnell et al. 1992), whereas luminal cells express K8 with K18, CD57 (Liu et al. 1997), AR and the secretory proteins, PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP). In addition to the basal and luminal cells there is a third epithelial cell type, neuroendocrine cells. These basally located cells express a mixed keratin pattern, including K5 and K8, and secrete serotonin and chromogranin A (Abrahamsson 1999). As these cells are non‐proliferative, they are generally believed to arise from a common stem cell along with the luminal cells and TA cells of the basal layer (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Expression patterns of differentiation markers in normal prostate and prostate cancer. Stem cells in both normal prostate and prostate cancer have a basal cell phenotype with expression of CD133, high levels of β1 integrin, and keratins K5 and K14. These cells give rise to transit‐amplifying populations that still have high integrin expression but no longer express CD133. Normal transit‐amplifying cells (TA) differentiate into luminal cells with transient expression of keratin 19 before fully differentiating into prostate‐specific antigen‐secreting cells that express K8, K18 and the androgen receptor (AR). Cancer transit‐amplifying cells loose expression of integrins and differentiate into secretory cancer cells that comprise the majority of the tumour. CD44 is expressed by all normal basal cells and by the stem and TA tumour cells. Neuroendocrine (NE) cells arise from differentiation of normal basal cells and have a complex marker expression pattern of basal and luminal keratins, together with secretion of chromogranin A and serotonin. The origin of NE cells in tumours is unclear but may be either from TA cells or from more differentiated tumour cells.

Further studies of keratin expression demonstrated that there are cells with a phenotype intermediate between that of basal and luminal cells and this led to the idea that these cells represented the TA population. These cells do not express K14 but instead, either K17 or K19. The expression of K19 in a subgroup of luminal cells has led to the proposed differentiation pathway represented in Fig. 1 (Hudson et al. 2000). The stem cells express K5 and 14, whereas the TA cells express K19 and low levels of K8 (van Leenders et al. 2000). Expression of K19 is transiently maintained by cells moving into a luminal location before being lost as the cells differentiate fully to a secretory phenotype expressing K8 and 18.

Our group has recently shown that the transmembrane glycoprotein, CD44, was also differentially expressed within the basal layer (Alam et al. 2004). CD44 functions as an extracellular matrix receptor and is involved in cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions in both normal and tumour tissues. The protein can be expressed in a number of different isoforms that are generated by alternative DNA splicing and larger isoforms have been shown to be involved in various human malignancies, including squamous cell carcinoma (Hudson et al. 1996) and prostate (Nagabhushan et al. 1996). In the K14 expressing basal cells, CD44 expression was restricted to shorter isoforms, whereas the largest isoform (termed v3‐v10) was found in K14 negative cells, corresponding to expression of K19.

Cancer

Since most prostate tumours have a predominantly luminal phenotype with expression of K8 and androgen receptor, this has led to the belief that tumours arise from a luminal or intermediate cell type. However, a more detailed examination of keratin‐staining patterns in tissue sections of prostate cancers has revealed a small percentage of cells that express K5, the basal cell marker. In a panel of metastatic prostate cancers, it was found that K5 expression could be detected in 28% of untreated patients. This figure rose to 75% in patients whose disease regressed following androgen deprivation and this fell to 43% in patients whose disease progressed to androgen independence (van Leenders et al. 2001). This is in line with the idea that the cancers contain an androgen‐independent cell, with a basal K5 expressing phenotype.

Prostate stem cell culture models

Recent advances in the development of culture systems have allowed the study of stem cells in both in vitro and in vivo situations. We found that using clonal epithelial cell growth on an irradiated 3T6 cell feeder layer resulted in a colony‐forming efficiency of approximately 6% for primary prostatic epithelial cells (Hudson et al. 2000). The colonies generated were of two distinct types, which we named types I and II. Type I colonies, forming the majority of colonies, were irregular in shape, made up of both K14 expressing basal‐type cells and more differentiated cells expressing the luminal cell marker, K8. A smaller number of cells, approximately 10% of colony‐producing cells, produced type II colonies. Compared to type I colonies these were much larger and were comprised of densely packed small cells that almost exclusively expressed K14, indicative of low levels of differentiation. We believe that the cells generating type II colonies have a more stem cell‐like phenotype than the rest. Using the criteria of colony formation we therefore estimated that approximately 2% of basal cells were stem cells. We showed that colony‐forming cells attached to extracellular matrix proteins more rapidly and that this could be used to enrich for the stem cell population. Collins et al. (2001) went on to show, by flow cytometry, that the colony‐forming cells expressed higher levels of β1 integrin. Rapidly adhering basal cells also had the ability, when combined with human stromal cells, to form differentiated, three‐dimensional secretory prostatic acinar‐like structures in athymic mouse xenografts. Since one of the definitions of a stem cell is the ability to generate differentiated daughter cells, this confirmed the presence of stem cells within the high β1integrin expressing population.

PROSTATE STEM CELL MARKERS

There has recently been an enormous increase in interest in stem cell markers in different tissues. Two stem cells markers, Hoechst 33342‐excluding side population cells and the cell‐surface marker, CD133, have been identified in both normal tissues and in cancers and there is now evidence for them in the prostate.

Side populations

One of the functional characteristics of bone marrow stem cells is the ability to efflux a nucleic acid‐binding fluorescent dye called Hoechst 33342. Experimentally, the fluorescence level of Hoechst 33342 bound dye is proportional to cellular DNA content, allowing assessment of the cell cycle. Goodell et al. (1996) observed that measuring Hoechst emission at two wavelengths, rather than the usual single wavelength, allowed identification of a rare side population (SP) of cells in murine bone marrow with dim fluorescence. The reduced fluorescence resulted from the efflux activity of a group of drug‐resistance pump proteins (ATP‐binding cassetted (ABC) transporter superfamily) expressed on the cell surface. Only SP cells exhibited a primitive haemopoietic phenotype and a proportion of these were found to express markers previously described as characteristic of stem cells. The subsequent isolation of rhesus monkey SP cells demonstrated that a haemopoietic SP is conserved across species (Goodell et al. 1997).

Recently, this method has been utilised widely to identify SPs in a range of normal adult tissues across species (reviewed by Zhou et al. 2001). Side populations have now also been identified in a range of cancers including neuroblastoma, and are also present in a number of cancer cell lines (Hirschmann‐Jax et al. 2004). It was further shown that not only did the C6 glioma cell lines maintain cells with SP characteristics but the SP alone were capable of regenerating tumours in mice (Kondo et al. 2004). In addition, the side populations within primary cancers and cancer cell lines were shown to be able to efflux cytotoxic agents, thereby conferring these cells with an ability to resist anticancer therapies (Hirschmann‐Jax et al. 2004). This suggests one way in which CSCs may be relatively more resistant to therapeutic agents.

Recently it was shown that prostatic epithelial tissue contains a side population constituting 1.38% of the epithelial cells and exhibiting low cell cycle activity (Bhatt et al. 2003), a feature that may be considered a general stem cell characteristic in vivo. However, the prostate SP cells were phenotypically heterogeneous, expressing either basal or luminal keratins and populations with differing light scatter characteristics were identified by flow cytometry. Interestingly, cells within the tail of the SP did express high levels of integrin α2 that, as described previously, had previously been identified as a marker for a stem cell‐enriched subpopulation of epithelial cells (Collins et al. 2001). At present there is no evidence for SP in prostate cancers although preliminary data (not shown) from our laboratory have shown that at least some prostate cancer cell lines maintain a SP with 22RV‐1 showing a SP of less than 1% of the cells. More work needs to be carried out, however, to characterize these cells further and to identify any differential tumourigenic potential between SP and non‐SP cells.

CD133

CD133 is the human homologue of prominin, a cell surface protein originally found on neuroepithelial stem cells in mice. CD133 is a five‐transmembrane‐domain cell‐surface glycoprotein that localizes to membrane protrusions. Its function is currently unknown although a frameshift mutation resulting in a loss of protein transport to the cell surface was shown to result in retinal degeneration (Maw et al. 2000). It has been suggested that this indicates a role for CD133 in either establishing or maintaining essential plasma membrane protrusions (Corbeil et al. 2001). Antibodies have now been used to identify and isolate CD133 stem cells from several different tissues. The first isolation was from haemopoietic cells (Yin et al. 1997). Since then the technique has been extended to other tissues including endothelial cells (Peichev et al. 2000), neuronal cells (Uchida et al. 2000), prostate (Richardson et al. 2004) and kidney progenitor cells (Bussolati et al. 2005).

Richardson and colleagues have demonstrated that similar to other tissues, a small number of cells in the prostate expressed CD133. They took the rapidly adhering, high integrin (α2β1hi) expressing populations of basal cells that they had previously shown to contain the epithelial stem cells (Collins et al. 2001) and further enriched for stem cells using anti‐CD133 antibody coated magnetic beads. The CD133‐positive (CD133+) population was shown to have a greater colony‐forming efficiency and higher proliferative output than the negative cells. Furthermore, colonies first appeared from CD133+ cells up to 5 days later than the CD133−α2β1hi cells, indicating them to be in a more quiescent state. The proportion of CD133+ cells within the α2β1hi population was approximately 1 in 4, indicating the CD133+ population accounts for approximately 0.75% of the total basal population. Immunofluorescent staining identified CD133+ cells to be contained within the basal layer and staining of isolated cells has shown them to be of a basal phenotype, with the majority expressing K5 and 14. There was no positive staining for either PSA or AR. As final confirmation that these cells can act as stem cells, CD133+ or CD133− cells were grafted with human stromal cells into nude mice. Only the grafts derived from CD133+ cells resulted in growth and these showed full differentiation not only to basal cells but also to luminally located cells that stained positively for K8, PAP and the AR.

Following on from these studies, Collins et al. (2001) have now shown that prostate cancers also contain a population of cells with the same phenotype (manuscript submitted, personal communication). From a panel of 40 primary and metastatic prostate carcinoma patients approximately 0.01% of tumour cells had a stem cell marker profile of CD44+/α2β1hi/CD133+. These cells had a basal phenotype, as for normal stem cells, with expression of K5, K14 but not K18, PSA, PAP, AR or c‐MET. In addition to the stem cell phenotype there were also more differentiated, proliferative CD44 positive cells with CD44+/α2β1hi/CD133− or CD44+/α2β1low, representative of transit‐amplifying and committed populations. This is summarised in Fig. 1. The putative cancer stem cells had an extensive capacity for self‐renewal compared to the other cell types, were more anchorage independent when held in methylcellulose, and were more invasive through matrigel than MCF7 or PC3M in 6/7 cases and equal in one case.

Preliminary studies from our laboratory also confirm a CD133+ population in hormone refractory prostate cancer that survives suspension in methylcellulose and has higher proliferative capacity than normal. Early examples indicate that the proportion of stem cells in these tumours may be higher than seen in hormone‐sensitive disease but more replicates are needed before this can be confirmed.

Animal studies are required to confirm that the CD133 population are indeed tumour forming, as seen in other tumour types and the results of these studies should begin to appear in the near future.

REGULATION OF CANCER STEM CELL SELF‐RENEWAL

In normal tissues, homeostasis is maintained through a fine balance between stem cell self‐renewal and loss of cells through differentiation or apoptosis. This is established through interactions with environment factors such as soluble growth factors, the extracellular matrix or neighbouring cells (Fuchs et al. 2004). Some of the factors that have been shown to be involved in stem cell self‐renewal have also been implicated in CSC control. These include the Delta/Notch1 pathway, hedgehog and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ). Studies involving mouse development have shown the importance of several individual pathways in normal prostate growth but only limited proof of their involvement in prostate cancer exists.

Notch

The Notch receptor and its ligand, Delta, are involved in both tissue development (Artavanis‐Tsakonas et al. 1999) and in the maintenance of adult tissues (Milner et al. 1994). Keratinocyte stem cells in the skin express higher levels of Delta1 than their neighbours and signal to their neighbours, via Notch1, to enter the differentiation pathway (Lowell et al. 2000). In the prostate, Wang et al. (2004) demonstrated that ablation of Notch expression from the mouse prostate inhibited branching morphogenesis, growth and differentiation during development and inhibited prostate regrowth triggered by hormone replacement in castrated mice. Also in the mouse, Notch 1 was up‐regulated during tumourigenesis in the TRAMP mouse model (Shou et al. 2001).

Hedgehog

One of the signalling pathways crucial for both embryonic pattern formation and in stem cell self‐renewal and regeneration involves Hedgehog (Hh) and its receptors Patched (PTCH) and Smoothened (SMO), which signal through a complex pathway to the GLI transcription factor. Hh signalling has been implicated in several types of human cancer including basal‐cell carcinoma, medulloblastoma and prostate cancer (reviewed in (Stecca et al. 2005). Karhadkar and colleagues (Karhadkar et al. 2004) showed that several prostate cancer cell lines express high levels of Hh pathway components and that blocking Hh signalling using cyclopamine inhibited cell growth both in vitro and in vivo. A direct role in progenitor cell growth was implicated by experiments whereby blocking the Hh pathway using cyclopamine or an Hh‐neutralising antibody inhibited prostate regeneration following castration induced prostate regression. Disrupting Hh signalling by over‐expressing GLI was also shown to induce tumourigenesis in normal cells.

TGFβ

Recently it was demonstrated that in the mouse, label‐retaining cells (a function of the quiescent nature of stem cells) are concentrated in the proximal regions of prostatic ducts (Tsujimura et al. 2002), a region that is also known to have higher levels of stromally derived TGFβ (Nemeth et al. 1997). Tsujimura proposed that the high levels of TGFβ might be involved in maintaining the stem cells in a state of quiescence. This group has since gone on to show that higher levels of Bcl‐2 are also produced in the proximal region and these are believed to protect the cells from TGFβ‐induced apoptosis. This may be particularly important following castration, when levels of TGFβ are increased. Bruckheimer & Kyprianou (2002) showed that Bcl‐2 antagonises the effects of TGFβ in tumour cells and it therefore appears that both normal stem cells and cancer cells express high levels of Bcl‐2.

Other factors that may be involved in the regulation of prostate cancer stem cells include p27kip1 (De Marzo et al. 1998; Di Cristofano et al. 2001), a negative cell cycle regulator that is expressed in a subset of basal cells and which is lost in cancers; and the Polycomb group proteins, transcriptional regulators that may be important in controlling prostate cell growth (Bernard et al. 2005).

CONCLUSIONS

There is now conclusive evidence for the existence of cancer stem cells in several tumour types including leukaemias, breast and brain but, to date, nothing has been published on PCSCs. One anticipates this will change shortly and studies identifying and characterizing a tumour‐forming stem cell from prostate cancer should soon be published. The information we have so far indicates that, as for other tissues, the prostate stem cell shares many characteristics with its normal counterpart, with a basal phenotype expressing K5 and 14, Bcl‐2, CD44, CD133, and high levels of β1 integrin. We may find that the main impact of genetic changes in stem cells do not affect the stem cell itself, but instead results in incomplete differentiation of their progeny.

The most important implication from the identification of stem cells is that current drug‐based therapies may be targeting the wrong cells and treatments such as androgen ablation may be killing the transit‐amplifying and postproliferative tumour cells but not the stem cells. One result of this approach to therapy is the emergence of tumours that evade androgen deprivation through amplification or mutations of the androgen receptor that allow the cells to survive very low androgen levels or to use alternative growth factors or cytokines. If we can target the prostate cancer stem cell before these mutations occur we may be able to prevent the progression to androgen independence.

Now that we are closer to identifying a definitive prostate cancer stem cell we should be able to determine the precise role of different signalling pathways in their maintenance and more precisely target these cells.

REFERENCES

- Abrahamsson PA (1999) Neuroendocrine differentiation in prostatic carcinoma. Prostate 39, 135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam TN, O'Hare MJ, Laczko I, Freeman A, Al‐Beidh F, Masters JR, Hudson DL (2004) Differential expression of CD44 during human prostate epithelial cell differentiation. J Histochem. Cytochem. 52, 1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Hajj M, Becker MW, Wicha M, Weissman I, Clarke MF (2004) Therapeutic implications of cancer stem cells. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14, 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artavanis‐Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ (1999) Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science 284, 770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard D, Martinez‐Leal JF, Rizzo S, Martinez D, Hudson D, Visakorpi T, Peters G, Carnero A, Beach D, Gil J (2005) CBX7 controls the growth of normal and tumor‐derived prostate cells by repressing the Ink4a/Arf locus. Oncogene 24, 5543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt RI, Brown MD, Hart CA, Gilmore P, Ramani VA, George NJ, Clarke NW (2003) Novel method for the isolation and characterisation of the putative prostatic stem cell. Cytometry 54A, 89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonkhoff H, Remberger K (1996) Differentiation pathways and histogenetic aspects of normal and abnormal prostatic growth: a stem cell model. Prostate 28, 98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet D, Dick JE (1997) Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat. Med. 3, 730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckheimer EM, Kyprianou N (2002) Bcl‐2 antagonizes the combined apoptotic effect of transforming growth factor‐beta and dihydrotestosterone in prostate cancer cells. Prostate 53, 133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussolati B, Bruno S, Grange C, Buttiglieri S, Deregibus MC, Cantino D, Camussi G (2005) Isolation of renal progenitor cells from adult human kidney. Am. J. Pathol. 166, 545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, Vessella R, Rosenfeld MG, Sawyers CL (2004) Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat. Med. 10, 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AT, Habib FK, Maitland NJ, Neal DE (2001) Identification and isolation of human prostate epithelial stem cells based on alpha(2)beta(1)‐integrin expression. J. Cell Sci. 114, 3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbeil D, Roper K, Fargeas CA, Joester A, Huttner WB (2001) Prominin: a story of cholesterol, plasma membrane protrusions and human pathology. Traffic 2, 82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha GR, Donjacour AA, Cooke PS, Mee S, Bigsby RM, Higgins SJ, Sugimura Y (1987) The endocrinology and developmental biology of the prostate. Endocr. Rev. 8, 338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Marzo AM, Meeker AK, Epstein JI, Coffey DS (1998) Prostate stem cell compartments: expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 in normal, hyperplastic, and neoplastic cells. Am. J. Pathol. 153, 911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cristofano A, De Acetis M, Koff A, Cordon‐Cardo C, Pandolfi PP (2001) Pten and p27KIP1 cooperate in prostate cancer tumor suppression in the mouse. Nat. Genet. 27, 222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Krishna NS, Grigor KM, Bartlett JM (2003) Androgen receptor gene amplification and protein expression in hormone refractory prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 89, 552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English HF, Santen RJ, Isaacs JT (1987) Response of glandular versus basal rat ventral prostatic epithelial cells to androgen withdrawal and replacement. Prostate 11, 229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GS, Chandler JA (1987) Cell proliferation studies in the rat prostate: II. The effects of castration and androgen‐induced regeneration upon basal and secretory cell proliferation. Prostate 11, 339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florek M, Haase M, Marzesco AM, Freund D, Ehninger G, Huttner WB, Corbeil D (2005) Prominin‐1/CD133, a neural and hematopoietic stem cell marker, is expressed in adult human differentiated cells and certain types of kidney cancer. Cell Tissue Res. 319, 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Tumbar T, Guasch G (2004) Socializing with the neighbors: stem cells and their niche. Cell 116, 769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli R, Binda E, Orfanelli U, Cipelletti B, Gritti A, De Vitis S, Fiocco R, Foroni C, Dimeco F, Vescovi A (2004) Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem‐like neural precursors from human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 64, 7011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldie JH, Coldman AJ (1979) A mathematic model for relating the drug sensitivity of tumors to their spontaneous mutation rate. Cancer Treat. Rev. 63, 1727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell MA, Brose K, Paradis G, Con Ner AS, Mulligan RC (1996) Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 183, 1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell MA, Rosenzweig M, Kim H, Marks DF, Demaria M, Paradis G, Grupp SA, Sieff CA, Mulligan RC, Johnson RP (1997) Dye efflux studies suggest that hematopoietic stem cells expressing low or undetectable levels of CD34 antigen exist in multiple species. Nat. Med. 3, 1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Partin AW, Zahurak M, Piantadosi S, Epstein JI, Walsh PC (2003) Biochemical (prostate specific antigen) recurrence probability following radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer. J. Urol. 169, 517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward SW, Rosen MA, Cunha GR (1997) Stromal–epithelial interactions in the normal and neoplastic prostate. Br. J. Urol. 79 (Suppl. 2), 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschmann‐Jax C, Foster AE, Wulf GG, Nuchtern JG, Jax TW, Gobel U, Goodell MA, Brenner MK (2004) A distinct ‘side population’ of cells with high drug efflux capacity in human tumor cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A 101, 14228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzbeierlein J, Lal P, LaTulippe E, Smith A, Satagopan J, Zhang L, Ryan C, Smith S, Scher H, Scardino P, Reuter V, Gerald WL (2004) Gene Expression Analysis of Human Prostate Carcinoma during Hormonal Therapy Identifies Androgen‐Responsive Genes and Mechanisms of Therapy Resistance. Am. J. Pathol 164, 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson DL, Guy AT, Fry PM, O'Hare MJ, Watt FM, Masters JRW (2001) Epithelial differentiation pathways in the human prostate: identification of intermediate phenotypes by keratin expression. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 49, 271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson DL, O'Hare MJ, Watt FM, Masters JRW (2000) Proliferative heterogeneity in the human prostate: evidence for epithelial stem cells. Lab. Invest. 80, 1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson DL, Speight PM, Watt FM (1996) Altered expression of CD44 isoforms in squamous‐cell carcinomas and cell lines derived from them. Int. J. Cancer 66, 457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs JT, Coffey DS (1989) Etiology and disease process of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate Suppl. 2, 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, Ghafoor A, Ward E, Thun MJ (2003) Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J. Clin. 53, 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karhadkar SS, Bova GS, Abdallah N, Dhara S, Gardner D, Maitra A, Isaacs JT, Berman DM, Beachy PA (2004) Hedgehog signalling in prostate regeneration, neoplasia and metastasis. Nature 431, 707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CF, Jackson EL, Woolfenden AE, Lawrence S, Babar I, Vogel S, Crowley D, Bronson RT, Jacks T (2005) Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell 121, 823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Setoguchi T, Taga T (2004) Persistence of a small subpopulation of cancer stem‐like cells in the C6 glioma cell line. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A 101, 781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Der Kwast TH, Tetu B, Suburu ER, Gomez J, Lemay M, Labrie F (1998) Cycling activity of benign prostatic epithelial cells during long‐term androgen blockade: evidence for self‐renewal of luminal cells. J. Pathol. 186, 406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leenders GJ, Aalders TW, Hulsbergen‐van de Kaa CA, Ruiter DJ, Schalken JA (2001) Expression of basal cell keratins in human prostate cancer metastases and cell lines. J. Pathol. 195, 563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leenders G, Dijkman H, Hulsbergen‐van de Kaa C, Ruiter D, Schalken J (2000) Demonstration of intermediate cells during human prostate epithelial differentiation in situ and in vitro using triple‐staining confocal scanning microscopy. Lab. Invest. 80, 1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Yu X, Ge K, Melamed J, Roeder RG, Wang Z (2002) Heterogeneous expression and functions of androgen receptor co‐factors in primary prostate cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 161, 1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu AY, True LD, Latray L, Ellis WJ, Vessella RL, Lange PH, Higano CS, Hood L, van Den Engh G (1999) Analysis and sorting of prostate cancer cell types by flow cytometry. Prostate 40, 192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu AY, True LD, Latray L, Nelson PS, Ellis WJ, Vessella RL, Lange PH, Hood L, van Den Engh G (1997) Cell‐cell interaction in prostate gene regulation and cytodifferentiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A 94, 10705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell S, Jones P, Le Roux I, Dunne J, Watt FM (2000) Stimulation of human epidermal differentiation by delta‐notch signalling at the boundaries of stem‐cell clusters. Curr. Biol. 10, 491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackillop WJ, Ciampi A, Till JE, Buick RN (1983) A stem cell model of human tumor growth: implications for tumor cell clonogenic assays. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 70, 9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maw MA, Corbeil D, Koch J, Hellwig A, Wilson‐Wheeler JC, Bridges RJ, Kumaramanickavel G, John S, Nancarrow D, Roper K, Weigmann A, Huttner WB, Denton MJ (2000) A frameshift mutation in prominin (mouse) ‐like 1 causes human retinal degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell TJ, Troncoso P, Brisbay SM, Logothetis C, Chung LW, Hsieh JT, Tu SM, Campbell ML (1992) Expression of the protooncogene bcl‐2 in the prostate and its association with emergence of androgen‐independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 52, 6940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner LA, Kopan R, Martin DI, Bernstein ID (1994) A human homologue of the drosophila developmental gene, Notch, is expressed in CD34+ hematopoietic precursors. Blood 83, 2057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagabhushan M, Pretlow TG, Guo YJ, Amini SB, Pretlow TP, Sy MS (1996) Altered expression of CD44 in human prostate cancer during progression. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 106, 647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle RB, Ahmann FR, McDaniel KM, Paquin ML, Clark VA, Celniker A (1987) Cytokeratin characterization of human prostatic carcinoma and its derived cell lines. Cancer Res. 47, 281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth JA, Sensibar JA, White RR, Zelner DJ, Kim IY, Lee C (1997) Prostatic ductal system in rats: tissue‐specific expression and regional variation in stromal distribution of transforming growth factor‐beta 1. Prostate 33, 64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh WK (2002) The evolving role of estrogen therapy in prostate cancer. Clin. Prostate Cancer 1, 81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peichev M, Naiyer AJ, Pereira D, Zhu Z, Lane WJ, Williams M, Oz MC, Hicklin DJ, Witte L, Moore MA, Rafii S (2000) Expression of VEGFR‐2 and AC133 by circulating human CD34(+) cells identifies a population of functional endothelial precursors. Blood 95, 952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GD, Robson CN, Lang SH, Neal DE, Maitland NJ, Collins AT (2004) CD133, a novel marker for human prostatic epithelial stem cells. J. Cell Sci. 117, 3539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Gleave ME, Bruchovsky N, Rennie PS, Goldenberg SL, Lange PH, Sullivan LD (1996) Intermittent androgen suppression delays progression to androgen‐independent regulation of prostate‐specific antigen gene in the LNCaP prostate tumour model. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 58, 139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou J, Ross S, Koeppen H, de Sauvage FJ, Gao WQ (2001) Dynamics of notch expression during murine prostate development and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 61, 7291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, Henkelman RM, Cusimano MD, Dirks PB (2004) Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature 432, 396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecca B, Mas C, Altaba AR (2005) Interference with HH‐GLI signaling inhibits prostate cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 11, 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, Chi KN, Oudard S, Theodore C, James ND, Turesson I et al. (2004) Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taplin ME, Rajeshkumar B, Halabi S, Werner CP, Woda BA, Picus J, Stadler W, Hayes DF, Kantoff PW, Vogelzang NJ, Small EJ (2003) Androgen receptor mutations in androgen‐independent prostate cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study 9663. J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimura A, Koikawa Y, Salm S, Takao T, Coetzee S, Moscatelli D, Shapiro E, Lepor H, Sun TT, Wilson EL (2002) Proximal location of mouse prostate epithelial stem cells: a model of prostatic homeostasis. J. Cell Biol. 157, 1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N, Buck DW, He D, Reitsma MJ, Masek M, Phan TV, Tsukamoto AS, Gage FH, Weissman IL (2000) Direct isolation of human central nervous system stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A 97, 14720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen AP, Aalders TW, Ramaekers FC, Debruyne FM, Schalken JA (1988) Differential expression of keratins in the basal and luminal compartments of rat prostatic epithelium during degeneration and regeneration. Prostate 13, 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen AP, Ramaekers FC, Aalders TW, Schaafsma HE, Debruyne FM, Schalken JA (1992) Colocalization of basal and luminal cell‐type cytokeratins in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 52, 6182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XD, Shou J, Wong P, French DM, Gao WQ (2004) Notch1‐expressing cells are indispensable for prostatic branching morphogenesis during development and re‐growth following castration and androgen replacement. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 24733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin AH, Miraglia S, Zanjani ED, Almeida‐Porada G, Ogawa M, Leary AG, Olweus J, Kearney J, Buck DW (1997) AC133, a novel marker for human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood 90, 5002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Schuetz JD, Bunting KD, Colapietro AM, Sampath J, Morris JJ, Lagutina I, Grosveld GC, Osawa M, Nakauchi H, Sorrentino BP (2001) The ABC transporter Bcrp1/ABCG2 is expressed in a wide variety of stem cells and is a molecular determinant of the side‐population phenotype. Nat. Med. 7, 1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]