Abstract

Abstract. Vascular progenitor cells have been the focus of much attention in recent years; both from the point of view of their pathophysiological roles and their potential as therapeutic agents. However, there is as yet no definitive description of either endothelial or vascular smooth muscle progenitor cells. Cells with the ability to differentiate into mature endothelial and vascular smooth muscle reportedly reside within a number of different tissues, including bone marrow, spleen, cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. Within these niches, vascular progenitor cells remain quiescent, until mobilized in response to injury or disease. Once mobilized, these progenitor cells enter the circulation and migrate to sites of damage, where they contribute to the remodelling process. It is generally perceived that endothelial progenitors are reparative, acting to restore vascular homeostasis, while smooth muscle progenitors contribute to pathological changes. Indeed, the number of circulating endothelial progenitor cells inversely correlates with exposure to cardiovascular risk factors and numbers of animal models and human studies have demonstrated therapeutic roles for endothelial progenitor cells, which can be enhanced by manipulating them to overexpress vasculo‐protective genes. It remains to be determined whether smooth muscle progenitor cells, which are less well studied than their endothelial counterparts, can likewise be manipulated to achieve therapeutic benefit. This review outlines our current understanding of endothelial and smooth muscle progenitor cell biology, their roles in vascular disease and their potential as therapeutic agents.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there has been huge interest in stem and progenitor cell biology, the pathophysiological roles and potential to exploit these cells for regenerative therapy. Atherosclerosis, a leading worldwide cause of morbidity and mortality, is compounded by the fact that surgical interventions aimed at unblocking or bypassing these lesions are themselves prone to developing atherosclerotic occlusion. Coronary artery bypass grafting, for example, commonly employs saphenous vein portions as conduits. However, the failure rate for these grafts is as much as 20% after 1 year and 40% after 10 years (van Brussel et al. 1997; Goldman et al. 2004). Thus, in order to serve patients better, there is a need to improve the patency of such grafts. Much work has been undertaken on the role of endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) in vascular biology and disease since they were first described in peripheral blood a decade ago (Asahara et al. 1997). More recently, haematopoietic cells with the potential to differentiate into smooth muscle cells have been identified and have, likewise, been dubbed smooth muscle progenitor cells (SMPC) (Han et al. 2001; Hillebrands et al. 2001; Shimizu et al. 2001; Sata et al. 2002; Simper et al. 2002). This review outlines our current understanding of these vascular progenitor cells and discusses their possible roles in disease progression and therapy.

LINEAGE OF VASCULAR PROGENITOR CELLS

Cells from a multitude of sources are reportedly able to differentiate into endothelial and/or smooth muscle cells, including bone marrow, peripheral blood and spleen, as well as cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue and embryonic stem cells (for review, see Caplice & Doyle 2005). However, there is as yet no definitive description of the origin and differentiation of EPC or SMPC.

Endothelial progenitor cells were initially described as being a subset of CD34+ haematopoietic stem cells (HSC) co‐expressing vascular endothelial growth factor receptor‐2 (VEGFR‐2/Flk‐1/KDR). These cells were able to differentiate into cells expressing a range of endothelial markers (including CD31, PECAM‐1, and the endothelial receptor tyrosine kinase, tie‐2), to incorporate acetylated low density lipoprotein (LDL), form tube‐like structures in vitro and produce nitric oxide in response to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Asahara et al. 1997; Shi et al. 1998). However, CD34 is not exclusively expressed on HSC and can be found at low levels on mature endothelial cells. Therefore, the more immature progenitor cell markers CD133 (prominin/AC133), c‐kit (CD117) and stem cell antigen‐1 (Sca‐1) have also been used (Caplice & Doyle 2005). Some data also indicate that EPCs may exist in populations of CD34− and CD133− mononuclear cells. Indeed, a population of CD34−/CD133+/VEGFR‐2+ progenitors, recently identified in peripheral blood, are proposed to be precursors of CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR‐2+ EPCs (Friedrich et al. 2006) and CD133−/CD14+ cells isolated from human umbilical cord blood are able to differentiate into mature endothelial cells (Kim et al. 2005). CD14+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) have been reported to express a range of pro‐angiogenic factors, including VEGF, hepatocyte growth factor and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF) (Fernandez Pujol et al. 2000; Moldovan et al. 2000; Harraz et al. 2001; Schmeisser et al. 2001; Rehman et al. 2003), to integrate into ischaemic tissue and to contribute to neo‐angiogenesis (Moldovan et al. 2000; Harraz et al. 2001; Urbich et al. 2003). So‐called side population cells, characterized by efflux of Hoechst 33342, from skeletal muscle are also reportedly able to engraft into damaged endothelium (Majka et al. 2003).

Endothelial progenitor cells contribute to re‐endothelialization of transplanted tissue. Indeed, models have shown that the endothelium of aortic allografts consists entirely of recipient‐derived cells (Hillebrands et al. 2001). In contrast, in cardiac transplant models very few endothelial cells of recipient origin have been observed. It is possible that these differences relate to the use of immunosuppressants in the cardiac but not aortic graft models (Hillebrands et al. 2005). In human studies, it has been demonstrated that the number of circulating EPCs is reduced in cardiac allograft patients with established transplant vasculopthy (Simper et al. 2003) and this may indicate sequestration of these cells to the graft site. Indeed, up to a third of endothelial cells may be recipient‐derived (Minami et al. 2005).

The source of smooth muscle cells within neo‐intimal lesions is still under debate, as different models have provided different answers. For example, animal models of post‐angioplasty restenosis and atherosclerosis have shown that the majority of smooth muscle cells of the intima are of bone marrow origin (Saiura et al. 2001; Sata et al. 2002). However, while it has been shown in rodents that smooth muscle cells of recipient origin are present in the intima of aortic grafts and a proportion of these cells are of bone marrow origin (Hillebrands et al. 2001; Shimizu et al. 2001), it has also been reported that bone marrow‐derived cells do not contribute to the intimal smooth muscle cell population in such grafts (Li et al. 2001; Hu et al. 2002a). Furthermore, animal models of cardiac and aortic transplant vasculopathy suggest that the majority of smooth muscle cells of neo‐intimal lesions are of recipient origin (Han et al. 2001; Hillebrands et al. 2001; Religa et al. 2002; Sata et al. 2002). It appears that no, or very few, smooth muscle cells within cardiac grafts in humans are of recipient origin (Glaser et al. 2002; Atkinson et al. 2004; Minami et al. 2005). In contrast, smooth muscle cells of donor origin have been observed in coronary atherosclerosis plaques in patients having received sex mismatched bone marrow transplantation (Caplice et al. 2003).

The adventitia has also been cited as a possible source of SMPC. Indeed, large numbers of Sca‐1+ cells were observed in the adventitia of aortic roots in apolipoprotein E (ApoE)−/– mice and also in ligated arteries in endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)−/– mice (Hu et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2006). However, it is conceivable that bone marrow‐derived SMPCs might first migrate to the adventitia and, subsequently, translocate to the intima. Indeed, non‐side population cells from skeletal muscle engraft into the smooth muscle of damaged vessels. Evidence suggests that these cells originate in the bone marrow but migrate to the muscle and subsequently lose their bone marrow markers, although they do retain haematopoietic potential (Jackson et al. 1999; Issarachai et al. 2002; McKinney‐Freeman et al. 2002; Majka et al. 2003). Some in vitro studies even suggest that mature endothelial cells can give rise to smooth muscle cells (Frid et al. 2002; Ishisaki et al. 2003).

DIFFERENTIATION OF VASCULAR PROGENITOR CELLS

While VEGF is known to play key roles in the differentiation of endothelial cells during embryonic development (Fong et al. 1995; Shalaby et al. 1995; Ferrara et al. 1996) and is required for the differentiation of EPC into mature endothelial cells in vitro (Asahara et al. 1997; Gehling et al. 2000; Zhao et al. 2003), there are likely to be other factors involved. For example, macrophage colony stimulating factor and transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β1 both play important roles in endothelial cell maturation during embryogenesis (Risau 1997; Minehata et al. 2002), as does vascular endothelial cadherin‐mediated cell adhesion (Hirashima et al. 1999). Smooth muscle cell differentiation from putative vascular progenitor cells is likewise poorly understood, although that TGF‐β1, TGF‐β3 and platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF)‐BB have roles in embryonic development point to their possible involvement (Nakajima et al. 1997; Hirschi et al. 1998; Hellstrom et al. 1999). Indeed, cells expressing a number of smooth muscle specific markers, including α‐smooth muscle actin (αSMA), smooth muscle myosin heavy chain and calponin, as well as CD34, VEGFR‐1 and VEGFR‐2 can be cultured from adult PBMC and VEGFR‐2+ embryonic stem cells in PDGF‐BB‐enriched media (Gehling et al. 2000; Yamashita et al. 2000; Simper et al. 2002). In addition, PDGF‐β receptor−/– mice show reduced investment of arterioles with smooth muscle cells (Lindahl et al. 1997).

MOBILIZATION, HOMING AND RECRUITMENT OF VASCULAR PROGENITOR CELLS

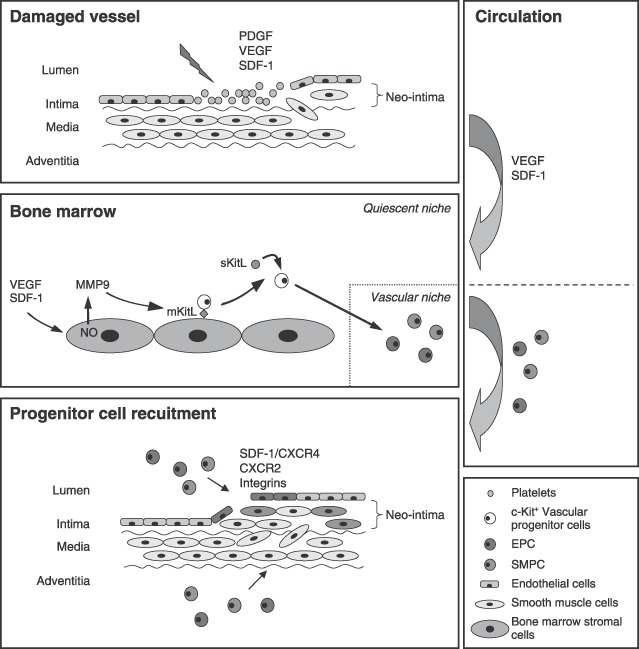

It is believed that under steady‐state conditions vascular progenitor cells are maintained in an undifferentiated and quiescent state but are mobilized following physiological stress and subsequently home to sites of vascular damage (Takahashi et al. 1999; Cheng et al. 2000; Shintani et al. 2001; Laufs et al. 2004). Indeed, there is a significant and rapid increase in the number of circulating EPC following traumatic vascular injury (Gill et al. 2001). The homing ability of vascular progenitor cells was first alluded to when transplanted bone marrow cells were observed lining Dacron grafts in dogs (Shi et al. 1998) and a multitude of factors have since been identified as being important for the mobilization and recruitment of vascular progenitor cells, including growth factors, cytokines/chemokines and integrins (Takahashi et al. 1999; Hattori et al. 2001, 2002; Heeschen et al. 2003; Bahlmann et al. 2004). Some of the key factors in these processes are highlighted in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Mobilization, homing and recruitment of vascular progenitor cells. Vascular damage, such as that following vein grafting or stenting, involves endothelial denudation and platelet accumulation. Platelets, along with neighbouring endothelial and smooth muscle cells, secrete various growth factors and cytokines/chemokines, including platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and stromal cell‐derived factor‐1 (SDF‐1). PDGF is important for smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation. VEGF and SDF‐1 are important for the mobilization of vascular progenitor cells; circulating in the blood and promoting progenitor cell translocation from the quiescent vascular bone marrow niche. Both endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and smooth muscle progenitor cells (SMPCs) of bone marrow origin have been observed in neo‐intimal lesions. Once mobilized, vascular progenitor cells are believed to migrate through the circulation to the site of damage where chemokines and integrins mediate their recruitment and there is evidence for both luminal and adventitial routes of entry. For illustrative purposes, vascular progenitor cells are shown as a population of c‐kit+ cells within the bone marrow, and as EPC and SMPC populations thereafter.

Mobilization of vascular progenitor cells

The mobilization of vascular progenitor cells has largely been studied in the context of EPC and tissue ischaemia. Both VEGF and stromal cell‐derived factor‐1 (SDF‐1) have emerged as key mediators of EPC mobilization (Asahara et al. 1999; Kalka et al. 2000; Pillarisetti & Gupta 2001; Shintani et al. 2001; Massa et al. 2005), functioning in a matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)‐9‐dependent manner (Gu et al. 2002; Heissig et al. 2002). Quiescent c‐kit+ cells are retained in the bone marrow niche by interaction with stromal cells. This interaction is supported by membrane‐bound Kit ligand (mKitL). However, nitric oxide‐mediated activation of MMP‐9 leads to cleavage of mKitL and results in release of soluble (s)KitL and the subsequent translocation of vascular progenitor cells into the circulation (Gu et al. 2002; Heissig et al. 2002). Indeed, both MMP‐9 expression and VEGF‐induced EPC mobilization are reduced in eNOS−/– mice and this correlates with reduced neo‐vascularization following ischaemia (Aicher et al. 2004). eNOS‐mediated nitric oxide production is dependent on the abundance of caveolin (Cav) (Feron & Kelly 2001) and Cav−/– mice demonstrate defective neo‐vascularization following ischaemic injury. In addition, adhesion of Cav−/– EPC to bone marrow stromal cells is resistant to SDF‐1‐mediated mobilization as a result of defective internalization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4, to which SDF‐1 binds exclusively (Lapidot 2001; Sbaa et al. 2006). Conversely, attachment of Cav−/– EPC to SDF‐1‐presenting endothelial cells is significantly increased (Sbaa et al. 2006). However, while eNOS appears to be important for EPC mobilization, it does not seem to directly influence EPC function, as assessed by colony formation and migration in vitro (Hoetzer et al. 2005). In contrast, phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase (PI3K)/Akt‐mediated signalling does appear to be important for both EPC mobilization and function. For example, in Akt1−/– mice, the functional activity of EPC, as well as their mobilization in response to ischaemia, is impaired (Ackah et al. 2005) and wortmannin, a PI3K inhibitor, has been shown to impair exogenous EPC‐mediated reduction of infarct size in a porcine ischaemia‐reperfusion model (Kupatt et al. 2005).

Erythropoietin (EPO), an endogenous protein produced by the kidney that regulates red blood cell production, has been shown to increase the mobilization of Sca‐1+/VEGFR‐2+ cells in mice (Urao et al. 2006) and EPC from patients with congestive heart failure that have been treated with EPO exhibit enhanced proliferation and greater adhesion to endothelial cells and fibronectin than EPC from untreated patients. Similar effects were noted when EPO was applied to EPC from healthy individuals in vitro and these effects were dose‐dependent (George et al. 2005b). EPO appears to exert its effects in a nitric oxide‐dependent manner (George et al. 2005b; Urao et al. 2006).

In coronary artery bypass grafting and burns patients, there is an increase (almost 50‐fold) in the number of CD133+/VEGFR‐2+ cells in the peripheral blood within 6–12 h after injury and a return to basal levels within 48–72 h, which is mirrored by plasma VEGF levels (Gill et al. 2001). However, patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) appear to have reduced numbers of circulating CD133+/VEGFR‐2+ EPC, although numbers can be increased by taking exercise, or with statin (hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitor) or GCSF treatment (Vasa et al. 2001a; Adams et al. 2004; Laufs et al. 2004; Powell et al. 2005). Statins reportedly increase the number and functional activity of EPC (Dimmeler et al. 2001; Llevadot et al. 2001; Vasa et al. 2001a). However, while EPC numbers are increased in the short term (up to 1 month), it has recently been shown that long‐term (3 months) statin treatment actually causes a decrease (almost half that seen prior to treatment) in the number of circulating EPC (Hristov et al. 2006). Use of GCSF to mobilize EPC is supported by recent evidence that serum concentrations of endogenous GCSF, in patients with acute myocardial infarction, correlate with the mobilization of CD34+ cells and improved left ventricular function (Leone et al. 2005), although there is a suggestion that GCSF treatment may increase the risk of vascular events (Hill et al. 2005; Zbinden et al. 2005). As with EPC, there is evidence that SDF‐1 is involved in SMPC mobilization. Indeed, carotid artery ligation in mice leads to an increase in the number of circulating SMPC, which correlates positively with SDF‐1 expression, although there appears to be no link between VEGF expression and SMPC mobilization (Zhang et al. 2006).

There is also compelling evidence that GCSF can mobilize SMPC. Indeed, exogenous application of GCSF mobilized putative SMPC in a rabbit model of vascular injury and this was associated with increased neo‐intimal hyperplasia (Cho et al. 2006). Furthermore, data from the recent MAGIC cell (Myocardial Regenation and Angiogenesis in Myocardial Infarction with GCSF and Intra‐coronary Stem Cell Infusion) trial show that GCSF‐mediated recruitment of bone marrow‐derived cells is associated with an increased rate of restenosis (Kang et al. 2004). It has also been demonstrated that plasma GCSF levels are increased in patients following coronary stenting and that this is associated with an increase in the number of circulating CD34+ cells. In these patients, late lumen loss positively correlated with the percentage increase in CD34+ cells (Inoue et al. 2007). While the effects of statin treatment on SMPC mobilization in vivo remain to be elucidated, it has recently been reported that the number of αSMA+ cells cultured from PBMC is reduced in the presence of pravastatin, which suggests possible inhibitory effects of statins on SMPC (Kusuyama et al. 2006a).

Recruitment and integration

It has been proposed that the recruitment of vascular progenitor cells is a multistep process akin to leucocyte recruitment during inflammation, involving chemo‐attraction, adhesion and transmigration, although the mechanisms involved still remain to be fully elucidated. Serum levels of SDF‐1 are selectively elevated during periods of ischaemia and the SDF‐1/CXCR4 axis has been shown to be important for the recruitment of EPC to ischaemic tissue (De Falco et al. 2004; Ceradini & Gurtner 2005). Indeed, in rodent models of ischaemia increased EPC recruitment is observed in response to increased local SDF‐1 concentrations (Askari et al. 2003; Yamaguchi et al. 2003) and activation of the thrombin receptor PAR‐1 on isolated EPC promotes proliferation, induces CXCR4 expression and enhances migration towards SDF‐1 (Smadja et al. 2005). SDF‐1 expression is regulated by the transcription factor hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 in a manner proportional to tissue oxygen tension (Ceradini et al. 2004) and adenoviral‐mediated overexpression of kinase‐deficient integrin‐linked kinase, a serine/threonine kinase, which lies upstream of hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1, in ischaemic limbs leads to reduced expression of SDF‐1 with an associated decrease in EPC recruitment (Lee et al. 2006). Recent data suggest that CXCR2 may also be important for EPC recruitment. In vitro, under flow conditions, a greater number of EPC arrested on immobilized CXCR2 ligands than on immobilized SDF‐1 and following wire‐induced injury in nude mice, infusion of human PBMC‐derived EPC‐enhanced endothelial recovery; an effect abrogated when EPCs were pre‐treated with an anti‐CXCR2 blocking antibody (Hristov et al. 2007). Based on their observations, the authors suggested that CXCR2 may be important for EPC arrest and CXCR4 for EPC transmigration.

Several studies have also indicated a role for integrins in EPC recruitment. EPCs express high levels of β1‐integrins (Deb et al. 2004), although they appear to preferentially bind to β2‐integrin ligands (Hristov et al. 2007). Indeed, while EPC binding to fibronectin is unaffected by the presence of neutralizing antibodies against β1‐integrin, antibodies against β2‐integrin inhibit EPC adhesion to and migration through endothelial monolayers (Deb et al. 2004; Chavakis et al. 2005) and compared to wild‐type mice, β2−/– mice show significantly impaired recovery after ischaemic injury (Chavakis et al. 2005). αvβ3‐ and αvβ5‐integrins are also highly expressed by EPC and have been shown to be important for re‐endothelialization in a rabbit balloon injury model (Walter et al. 2002; Deb et al. 2004). Furthermore, implanting stents coated with the αvβ3 ligand cyclic Arg‐Gly‐Asp resulted in accelerated re‐endothelialization and significantly reduced in‐stent restenosis in porcine carotid arteries, compared to uncoated stents. This was associated with a significant increase in the early recruitment of either infused EPCs or endogenous CD34+ cells (Blindt et al. 2006).

Platelets express several adhesion molecules and secrete potent chemokines at sites of vascular injury. In vitro, adherent platelets simulate chemotaxis and migration of embryonic EPC under flow conditions, which is inhibited in the presence of neutralizing antibodies against either P‐selectin glycoprotein ligand‐1 or very late antigen‐4 (a β1‐integrin). In addition, immobilized platelets exposed to thrombin stimulate chemotaxis and migration of embryonic EPC, as well as their differentiation into mature endothelial cells (Langer et al. 2006).

Other factors that may influence EPC recruitment include VEGF. Indeed, overexpression of VEGF‐C by fibroblasts embedded in a three‐dimensional collagen matrix lead to enhanced EPC invasion of and migration through the matrix (Bauer et al. 2005). Evidence also points to a possible role for β‐carotene; EPC chemotaxis is up‐regulated in response to β‐carotene stimulation and several genes involved in EPC homing and adhesion are likewise up‐regulated (Kiec‐Wilk et al. 2005).

As with EPC, the SDF‐1/CXCR4 axis appears to be important for the recruitment of SMPC and subsequent neo‐intima formation. In a mouse wire injury model, it was shown that apoptosis triggers SDF‐1 expression by medial smooth muscle cells and that SDF‐1 binds to platelets at the site of injury and mediates CXCR4‐dependent SMPC arrest (Zernecke et al. 2005). In addition, SDF‐1 up‐regulates expression of MMP‐2, which has been implicated in smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation (Kodali et al. 2006). Like EPC, SMPCs express high levels of β1‐integrin and in the presence of antibodies against β1‐integrin the binding of SMPC to fibrin is significantly reduced (Deb et al. 2004). In addition, given its importance in the recruitment of smooth muscle cells during embryonic development and its involvement in the migration of smooth muscle cells from the media to the intima following arterial injury, it is probable that PDGF‐BB also plays a role in SMPC recruitment (Hellstrom et al. 1999; Buetow et al. 2003).

VASCULAR PROGENITOR CELLS AND CARDIOVASCULAR RISK FACTORS

Endothelial cells help to maintain vessel homeostasis and it is believed that EPCs have a role in maintaining the integrity of the endothelium. Increased numbers of CD34+/VEFR‐2+ or CD133+ circulating EPCs are associated with a reduced risk of death from cardiovascular causes, and it has been suggested that the number of circulating EPCs may be a useful prognostic tool for determining the risk of cardiovascular events (Schmidt‐Lucke et al. 2005; Werner et al. 2005). Indeed, there is an inverse relationship between the number of circulating EPC and severity of CAD, independent of traditional risk factors (Kunz et al. 2006). In addition, it has recently been demonstrate that patients with acute coronary syndrome have an increased number of apoptotic circulating CD34+ cells, which is associated with the extent of coronary stenosis (Schwartzenberg et al. 2007).

While the risk of developing atherosclerotic lesions increases with age, it has been reported that the number of circulating CD34+/VEGFR‐2+ or CD133+/VEGFR‐2+ EPC are comparable between old and young individuals without major cardiovascular risk factors, although EPC isolated from older individuals do have a lower survival rate than those from younger people and exhibit reduced migration and proliferation (Heiss et al. 2005). This may be important in terms of a person's ability to maintain homeostasis and repair damage in ageing vessels. In addition, circulating EPC numbers are reduced in healthy individuals with risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and it is evident that a reduced number of circulating EPC correlates with endothelial dysfunction (Hill et al. 2003). There is, likewise, an inverse correlation between the number of circulating EPC and the number of risk factors in patients with known CAD (Vasa et al. 2001b; George et al. 2003, 2004), as well as in patients with disorders known to present a higher risk of developing CVD (Tepper et al. 2002; Chen et al. 2004; Choi et al. 2004; Kondo et al. 2004; Ghani et al. 2005; Grisar et al. 2005; Michaud et al. 2006).

Rheumatoid arthritis, for example, is associated with increased morbidity and mortality attributable to accelerated atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events (Wolfe et al. 1994; Raza et al. 2000). In patients with active disease, the number of circulating EPC is significantly reduced and isolated EPC from these people exhibit reduced migratory activity (Grisar et al. 2005; Herbrig et al. 2006). Other major risk factors for developing CVD, such as smoking and hypercholesterolaemia are also associated with reduced numbers of circulating EPC (Chen et al. 2004; Kondo et al. 2004; Michaud et al. 2006). In people who smoke, the number of circulating EPCs inversely correlates with the number of cigarettes smoked and rapidly increases following cessation of smoking (Kondo et al. 2004; Michaud et al. 2006). Furthermore, EPCs isolated from smokers exhibit impaired functional activity (Chen et al. 2004; Michaud et al. 2006) and, in vitro, benzo(α)pyrene, a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon present in tobacco smoke, dose dependently inhibits EPC colony formation (van Grevenynghe et al. 2006). EPCs isolated from hypercholesterolaemic individuals also demonstrate impaired functional activity and display increased apoptosis/senescence in response to oxidized LDL. These observations may underlie the reduced number of EPC seen in these individuals (Imanishi et al. 2004).

Incidence of hypertension increases with age, particularly in post‐menopausal women, and it is known that oestrogen augments EPC mobilization and recruitment following vascular injury (Iwakura et al. 2003; Strehlow et al. 2003). It has recently been demonstrated, in vitro, that EPC VEGF production and network formation is increased in the presence of 17β‐oestradiol and that 17β‐oestradiol dose dependently inhibits the onset of EPC senescence. Evidence suggests that this may occur through down‐regulation of angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) expression, which is known to be involved in the regulation of blood pressure (Imanishi et al. 2005b,c). Indeed, exposure to angiotensin II accelerates the onset of EPC senescence via mechanisms involving increased oxidative stress, and oestrogen down‐regulates AT1R in mature endothelial cells (Nickenig et al. 1998; Gragasin et al. 2003; Imanishi et al. 2005a,b).

Circulating EPCs are also reduced in patients with diabetes mellitus in accordance with disease severity, although numbers can be increased by improving glycaemic control (Kusuyama et al. 2006b). Patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD) also have reduced numbers of circulating EPCs, which are further reduced following dialysis. In addition, in vitro, serum from ESRD patients is able to impair the growth of EPC isolated from healthy volunteers (Westerweel et al. 2007).

Despite accumulating evidence that SMPCs contribute to alleviating vascular pathological changes, very few studies have looked at how cardiovascular risk factors influence SMPC. However, while cardiovascular risk factors invariably appear to negatively impact on EPC, the limited data available for SMPC are not so clear. For example, circulating SMPCs, like EPCs, are reduced in patients with diabetes mellitus in accordance with disease severity and increase in response to treatments that improve glycaemic control (Kusuyama et al. 2006b). In contrast, in patients with ESRD there is no difference in the number of circulating SMPCs compared to healthy controls. Circulating SMPC numbers are likewise unaffected by dialysis in ESRD patients and serum from ESRD patients has no effect on the growth of SMPC in vitro (Westerweel et al. 2007). A recent investigation of AT1R blockade as means to prevent in‐stent restenosis revealed that significantly more SMPC could be cultured from PBMC isolated from hypercholesterolaemic rabbits than from normal controls. This phenomenon was enhanced in animals that had also undergone carotid artery stenting but could be attenuated with AT1R blockade (Ohtani et al. 2006).

VASCULAR PROGENITOR CELLS AND PERCUTANEOUS REVASCULARIZATION

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stent implantation is the most commonly used revascularization technique and is routinely used in the management of patients with symptomatic CAD. However, 10–30% of these cases will go on to develop in‐stent restenosis (ISR), despite the development of drug‐eluting stents aimed a reducing such pathology (Froeschl et al. 2004). Indeed, while sirolimus‐eluting stents are often employed to prevent ISR, in vitro evidence suggests that sirolimus enhances EPC senescence (Imanishi et al. 2006).

While circulating EPCs are increased post‐PCI in patients with CAD (Bonello et al. 2006), evidence suggests that patients who develop ISR have fewer circulating EPC and that these exhibit reduced functional activity. Furthermore, when compared to patients who do not develop ISR, an increased proportion of these EPC are senescent (Matsuo et al. 2006). In addition, in patients with acute coronary syndrome, despite a significant increase in serum VEGF levels following PCI, EPC are not mobilized. However, the opposite is seen in patients presenting for elective PCI (Banerjee et al. 2006).

Diabetics have a higher incidence of ISR following PCI. Indeed, in diabetic mice re‐endothelialization is significantly reduced following wire injury and is likewise reduced in wild‐type mice transplanted with bone marrow from diabetic mice. Both of these phenomena are associated with reduced EPC recruitment. Indeed, it was recently demonstrated that EPCs derived from diabetic mice display reduced migration and reduced adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins in vitro (Ii et al. 2006). In mice, GCSF treatment has been shown to reduce neo‐intima formation and to increase re‐endothelialization after balloon injury, an observation associated with increase in the number of circulating cells expressing CD31, CD34, VEGFR‐2 or c‐kit (Kong et al. 2004a). However, the recent MAGIC cell trial revealed a high rate of ISR in patients receiving G‐CSF treatment prior to stent implantation, which may indicate mobilization of SMPC (Kang et al. 2006).

Circulating SMPCs may play a major role in the development of ISR. Indeed, in a recent study, while the number of circulating CD34+ cells in patients with atherosclerotic CAD varied following PCI, the frequency and severity of restenosis was the greatest in those patients with increased numbers of circulating CD34+ cells. In addition, the pre‐ and post‐PCI change in circulating CD34+ cells was independently predictive of late lumen loss, suggesting a possible role for these cells in the development of intimal hyperplasia (Schober et al. 2005). Furthermore, c‐kit+ cells co‐expressing αSMA have been identified in ISR lesions (Hibbert et al. 2004). Drug‐eluting stents have been deployed to try to reduce neo‐intimal hyperplasia and, despite its negative impact on EPC, sirolimus has been shown to reduce the formation of neo‐intimal hyperplasia following vascular injury. In vitro evidence suggests this may be achieved by inhibiting SMPC growth (Fukuda et al. 2005).

VASCULAR PROGENITOR CELLS AND VEIN GRAFT INTIMAL HYPERPLASIA

Following grafting of a vein into an artery, a process of remodelling occurs as the vein adapts to the arterial environment; this is characterized by thickening of the intima (intimal hyperplasia), resulting from smooth muscle cell accumulation and extracellular matrix deposition. This intimal hyperplasia acts as a substrate for development of accelerated atherosclerosis and subsequent graft occlusion (Mitra et al. 2006). The source of smooth muscle cells within neo‐intimal lesions of vein grafts is unclear and it has been reported that they may be of both donor and recipient origin (Hu et al. 2002b). By better understanding how intimal hyperplasia and subsequent atherosclerotic lesions develop within these vein grafts, improved post‐operative treatment strategies will hopefully be designed that are able to reduce or prevent the occurrence of such pathology.

Using a mouse model of vein graft atherosclerosis, it has been shown that one of the earliest events to occur following the grafting of a vein into an artery, in response to the increased physical stress, is endothelial cell death (Mayr et al. 2000). However, re‐endothelialization does occur and evidence suggests that circulating EPCs contribute to this process, with about one third of the regenerated endothelium being made up of bone marrow‐derived cells. When performed in ApoE−/– mice, vein grafts show reduced endothelial regeneration and enhanced atherosclerosis, which is associated with reduced numbers of circulating EPC. There is a suggestion that adventitia‐derived progenitor cells may contribute to the development of atherosclerotic lesions and may be a source of smooth muscle cells within the neo‐intima (Xu et al. 2003; Torsney et al. 2005). Nitric oxide‐induced VEGF plays a key role in neo‐intimal lesion development in vein grafts, as evidenced that inducible (i)NOS−/– mice, in which VEGF production is abrogated, exhibit increased neo‐intimal hyperplasia and reduced EPC homing. However, this can be rescued by local overexpression of VEGF (Mayr et al. 2006). Tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α signalling appears to be important for the progression of vein graft neo‐intimal hyperplasia and is involved in the regulation of chemokine and adhesion molecule expression by graft intrinsic cells (Zhang et al. 2004; Peppel et al. 2005). However, whether TNF‐α signalling directly influences recruitment of vascular progenitor cells to the graft remains to be determined.

VASCULAR PROGENITOR CELLS AND ATHEROSCLEROSIS

It has been suggested that reduced numbers of circulating EPCs are associated with the development of atherosclerosis and recent studies show that the number of CD34+/VEGFR‐2+ cells inversely correlates with the occurrence of atherosclerosis in asymptomatic individuals (Chironi et al. 2006; Fadini et al. 2006), although when measured at sites other than the carotid artery, this association was not significant after adjustment for Framingham risk score (Chironi et al. 2006). It is known that high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) protects against atherosclerosis and recent data show that increased serum levels of HDL correlates with an increase in EPC colony formation in vitro, but not in the number of circulating CD34+/CD133+ cells (Pellegatta et al. 2006). In ApoE−/– mice, administration of HDL leads to an increased number of Sca‐1+ endothelial cells in the aortic root following inflammatory insult with lipopolysaccharide (Tso et al. 2006) and transfusion of bone marrow from young, but not from old, ApoE−/– mice to high fat diet fed ApoE−/– mice prevents the development of atherosclerosis. Bone marrow from older mice was found to contain fewer cells expressing vascular progenitor cell markers. There was no change in the number of cells with haematopoietic stem cell markers or generalized murine stem cell markers, when compared to bone marrow from young mice. It was concluded that old ApoE−/– mice suffer from exhaustive consumption of their EPC and that this contributed to the development of atherosclerosis (Rauscher et al. 2003).

Bone marrow‐derived cells form a significant proportion of the smooth muscle cells within atherosclerotic plaques (Sata et al. 2002) and recent data indicate that transfer of bone marrow cells or spleen‐derived EPCs from ApoE−/– mice to age‐matched ApoE−/– mice significantly increases the size of atherosclerotic lesions occurring. Furthermore, atherosclerotic plaques in EPC‐transfused mice contained smaller fibrous caps and larger lipid cores than those in untreated controls, as well as a larger number of CD3+ cells (George et al. 2005a). Cells expressing progenitor cell markers, including CD34, c‐kit and VEGFR‐2, have recently been identified in human atherosclerotic lesions, and there is an increase in the number of these progenitors in the adventitia of atherosclerotic vessels. These cells may be a source of EPCs and/or SMPCs that contribute to the remodelling process (Torsney et al. 2007).

GENETIC MANIPULATION OF VASCULAR PROGENITOR CELLS

From the data discussed herein, it is apparent that progenitor cells contribute to vascular remodelling, and furthermore, that population of these cells may be isolated and deployed therapeutically. For clinical application, it is likely that autologous progenitor cells would be used, in order to avoid possible immunological complications, and the most readily available source is peripheral blood. As detailed earlier, vascular progenitor cells may be isolated from the mononuclear cell fraction of peripheral blood either by positive selection (e.g. CD34+, CD133+ and/or VEGFR‐2+ cells) or by selective culture in the presence of VEGF (EPC) or PDGF‐BB (SMPC). However, vascular progenitor cells are lineage committed and do not possess the same capacity for self‐renewal as pluripotent stem cells. Patients that are likely to undergo such therapy are also likely to exhibit one or more cardiovascular risk factors; there is a relationship between these and progenitor cell dysfunction. Indeed, both hypertension and exposure to oxidized LDL have been shown to accelerate EPC senescence (Imanishi et al. 2004, 2005d). Methods to improve the functional capacity of progenitor cells isolated from patients with cardiovascular risk factors therefore need to be devised. One way in which this might be achieved is by genetically manipulating these cells to overexpress vasculo‐protective genes. It has already been demonstrated, in a rabbit model of vascular injury, that infusion of EPC overexpressing eNOS leads to reduced neo‐intima formation and increased re‐endothelialization; significantly, more so than that observed in animals treated with vector‐transfected EPCs (Kong et al. 2004b). In addition, our group has recently demonstrated, in a mouse wire injury model, that infusion of CD34+ expressing the anticoagulation proteins tissue factor pathway inhibitor or hirudin under an αSMA promoter, co‐localized with smooth muscle cells within lesions, and in those areas infiltrated by these modified CD34+ cells, neo‐intimal formation was abolished (Chen et al. 2006).

CONCLUSIONS

While a great deal has been learned about the nature of progenitor cells in recent years, much of this work has focused on the role of EPC in angiogenesis or their therapeutic use following ischaemia (Asahara & Kawamoto 2004; Werner & Nickenig 2006). However, one of the biggest problems facing cardiovascular medicine today is the failure of bypass grafts, through thrombotic (early) or atherosclerotic (late) occlusion. There are limited data on the roles of vascular progenitor cells in the progression of vein graft intimal hyperplasia, and it has yet to be determined whether infusion of EPC, genetically manipulated or not, would be therapeutic in this context. In addition, one avenue that appears to have been overlooked thus far is the therapeutic use of SMPC. If these could be manipulated to overexpress vasculo‐protective genes, they might prove more effective in reducing intimal hyperplasia than EPC, being able to enter the lesion before deploying their payload; acting as a ‘Trojan Horse’. This notion is supported by the observation that, following wire injury, CD34+ expressing anticoagulation proteins under an αSMA promoter, co‐localized with smooth muscle cells and abolished neo‐intimal formation (Chen et al. 2006). While there is evidence supporting the therapeutic application of vascular progenitor cells, it is likely that the most effective progenitor‐based therapy will involve some genetic manipulation, exploiting inherent homing and engraftment characteristics of vascular progenitor cells to deliver therapeutic genes specifically to the target tissue.

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ackah E, Yu J, Zoellner S, Iwakiri Y, Skurk C, Shibata R, Ouchi N, Easton RM, Galasso G, Birnbaum MJ, Walsh K, Sessa WC (2005) Akt1/protein kinase B{alpha} is critical for ischemic and VEGF‐mediated angiogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2119–2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams V, Lenk K, Linke A, Lenz D, Erbs S, Sandri M, Tarnok A, Gielen S, Emmrich F, Schuler G, Hambrecht R (2004) Increase of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients with coronary artery disease after exercise‐induced ischemia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 684–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aicher A, Heeschen C, Dimmeler S (2004) The role of NOS3 in stem cell mobilization. Trends Mol. Med. 10, 421–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T, Kawamoto A (2004) Endothelial progenitor cells for postnatal vasculogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287, C572–C579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver M, Van Der Zee R, Li T, Witzenbichler B, Schatteman G, Isner JM (1997) Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science 275, 964–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T, Takahashi T, Masuda H, Kalka C, Chen D, Iwaguro H, Inai Y, Silver M, Isner JM (1999) VEGF contributes to postnatal neovascularization by mobilizing bone marrow‐derived endothelial progenitor cells. EMBO J. 18, 3964–3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askari AT, Unzek S, Popovic ZB, Goldman CK, Forudi F, Kiedrowski M, Rovner A, Ellis SG, Thomas JD, Dicorleto PE, Topol EJ, Penn MS (2003) Effect of stromal‐cell‐derived factor 1 on stem‐cell homing and tissue regeneration in ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Lancet 362, 697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson C, Horsley J, Rhind‐Tutt S, Charman S, Phillpotts CJ, Wallwork J, Goddard MJ (2004) Neointimal smooth muscle cells in human cardiac allograft coronary artery vasculopathy are of donor origin. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 23, 427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahlmann FH, De Groot K, Spandau JM, Landry AL, Hertel B, Duckert T, Boehm SM, Menne J, Haller H, Fliser D (2004) Erythropoietin regulates endothelial progenitor cells. Blood 103, 921–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Brilakis E, Zhang S, Roesle M, Lindsey J, Philips B, Blewett CG, Terada LS (2006) Endothelial progenitor cell mobilization after percutaneous coronary intervention. Atherosclerosis 189, 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer SM, Bauer RJ, Liu ZJ, Chen H, Goldstein L, Velazquez OC (2005) Vascular endothelial growth factor‐C promotes vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and collagen constriction in three‐dimensional collagen gels. J. Vasc. Surg. 41, 699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blindt R, Vogt F, Astafieva I, Fach C, Hristov M, Krott N, Seitz B, Kapurniotu A, Kwok C, Dewor M, Bosserhoff AK, Bernhagen J, Hanrath P, Hoffmann R, Weber C (2006) A novel drug‐eluting stent coated with an integrin‐binding cyclic Arg‐Gly‐Asp peptide inhibits neointimal hyperplasia by recruiting endothelial progenitor cells. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47, 1786–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonello L, Basire A, Sabatier F, Paganelli F, Dignat‐George F (2006) Endothelial injury induced by coronary angioplasty triggers mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with stable coronary artery disease1. J. Thromb. Haemost. 4, 979–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brussel BL, Ernst JM, Ernst NM, Kelder HC, Knaepen PJ, Plokker HW, Vermeulen FE, Voors AA (1997) Clinical outcome in venous coronary artery bypass grafting: a 15‐year follow‐up study. Int. J. Cardiol. 58, 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buetow BS, Tappan KA, Crosby JR, Seifert RA, Bowen‐Pope DF (2003) Chimera analysis supports a predominant role of PDGFRbeta in promoting smooth‐muscle cell chemotaxis after arterial injury. Am. J. Pathol. 163, 979–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplice NM, Bunch TJ, Stalboerger PG, Wang S, Simper D, Miller DV, Russell SJ, Litzow MR, Edwards WD (2003) Smooth muscle cells in human coronary atherosclerosis can originate from cells administered at marrow transplantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 4754–4759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplice NM, Doyle B (2005) Vascular progenitor cells: origin and mechanisms of mobilization, differentiation, integration, and vasculogenesis. Stem Cells Dev. 14, 122–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceradini DJ, Gurtner GC (2005) Homing to hypoxia: HIF‐1 as a mediator of progenitor cell recruitment to injured tissue. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 15, 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceradini DJ, Kulkarni AR, Callaghan MJ, Tepper OM, Bastidas N, Kleinman ME, Capla JM, Galiano RD, Levine JP, Gurtner GC (2004) Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF‐1 induction of SDF‐1. Nat. Med. 10, 858–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavakis E, Aicher A, Heeschen C, Sasaki K, Kaiser R, El Makhfi N, Urbich C, Peters T, Scharffetter‐Kochanek K, Zeiher AM, Chavakis T, Dimmeler S (2005) Role of beta2‐integrins for homing and neovascularization capacity of endothelial progenitor cells. J. Exp. Med. 201, 63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Weber M, Shiels PG, Dong R, Webster Z, McVey JH, Kemball‐Cook G, Tuddenham EG, Lechler RI, Dorling A (2006) Post‐injury vascular intimal hyperplasia in mice is completely inhibited by CD34+ bone marrow‐derived progenitor cells expressing membrane‐tethered anticoagulant fusion proteins. J. Thromb. Haemost. 4, 2191–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JZ, Zhang FR, Tao QM, Wang XX, Zhu JH, Zhu JH (2004) Number and activity of endothelial progenitor cells from peripheral blood in patients with hypercholesterolaemia. Clin. Sci. (London) 107, 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T, Rodrigues N, Shen H, Yang Y, Dombkowski D, Sykes M, Scadden DT (2000) Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science 287, 1804–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chironi G, Walch L, Pernollet MG, Gariepy J, Levenson J, Rendu F, Simon A (2007) Decreased number of circulating CD34 (+) KDR (+) cells in asymptomatic subjects with preclinical atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 191, 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HJ, Kim TY, Cho HJ, Park KW, Zhang SY, Kim JH, Kim SH, Hahn JY, Kang HJ, Park YB, Kim HS (2006) The effect of stem cell mobilization by granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor on neointimal hyperplasia and endothelial healing after vascular injury with bare‐metal versus paclitaxel‐eluting stents. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48, 366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JH, Kim KL, Huh W, Kim B, Byun J, Suh W, Sung J, Jeon ES, Oh HY, Kim DK (2004) Decreased number and impaired angiogenic function of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with chronic renal failure. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 1246–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Falco E, Porcelli D, Torella AR, Straino S, Iachininoto MG, Orlandi A, Truffa S, Biglioli P, Napolitano M, Capogrossi MC, Pesce M (2004) SDF‐1 involvement in endothelial phenotype and ischemia‐induced recruitment of bone marrow progenitor cells. Blood 104, 3472–3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb A, Skelding KA, Wang S, Reeder M, Simper D, Caplice NM (2004) Integrin profile and in vivo homing of human smooth muscle progenitor cells. Circulation 110, 2673–2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler S, Aicher A, Vasa M, Mildner‐Rihm C, Adler K, Tiemann M, Rutten H, Fichtlscherer S, Martin H, Zeiher AM (2001) HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) increase endothelial progenitor cells via the PI 3‐kinase/Akt pathway. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 391–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadini GP, Coracina A, Baesso I, Agostini C, Tiengo A, Avogaro A, Vigili de Kreutzenberg S (2006) Peripheral blood CD34+KDR+ endothelial progenitor cells are determinants of subclinical atherosclerosis in a middle‐aged general population. Stroke 37, 2277–2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Pujol B, Lucibello FC, Gehling UM, Lindemann K, Weidner N, Zuzarte ML, Adamkiewicz J, Elsasser HP, Muller R, Havemann K (2000) Endothelial‐like cells derived from human CD14 positive monocytes. Differentiation 65, 287–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feron O, Kelly RA (2001) The caveolar paradox: suppressing, inducing, and terminating eNOS signaling. Circ. Res. 88, 129–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Carver‐Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O'Shea KS, Powell‐Braxton L, Hillan KJ, Moore MW (1996) Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature 380, 439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong GH, Rossant J, Gertsenstein M, Breitman ML (1995) Role of the Flt‐1 receptor tyrosine kinase in regulating the assembly of vascular endothelium. Nature 376, 66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frid MG, Kale VA, Stenmark KR (2002) Mature vascular endothelium can give rise to smooth muscle cells via endothelial‐mesenchymal transdifferentiation: in vitro analysis. Circ. Res. 90, 1189–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich EB, Walenta K, Scharlau J, Nickenig G, Werner N (2006) CD34−/CD133+/VEGFR‐2+ endothelial progenitor cell subpopulation with potent vasoregenerative capacities. Circ. Res. 98, e20–e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froeschl M, Olsen S, Ma X, O’Brien ER (2004) Current understanding of in‐stent restenosis and the potential benefit of drug eluting stents. Curr. Drug Targets Cardiovasc. Haematol. Disord. 4, 103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda D, Sata M, Tanaka K, Nagai R (2005) Potent inhibitory effect of sirolimus on circulating vascular progenitor cells. Circulation 111, 926–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehling UM, Ergun S, Schumacher U, Wagener C, Pantel K, Otte M, Schuch G, Schafhausen P, Mende T, Kilic N, Kluge K, Schafer B, Hossfeld DK, Fiedler W (2000) In vitro differentiation of endothelial cells from AC133‐positive progenitor cells. Blood 95, 3106–3112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Afek A, Abashidze A, Shmilovich H, Deutsch V, Kopolovich J, Miller H, Keren G (2005a) Transfer of endothelial progenitor and bone marrow cells influences atherosclerotic plaque size and composition in apolipoprotein e knockout mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 2636–2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Goldstein E, Abashidze S, Deutsch V, Shmilovich H, Finkelstein A, Herz I, Miller H, Keren G (2004) Circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients with unstable angina: association with systemic inflammation. Eur. Heart J. 25, 1003–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Goldstein E, Abashidze A, Wexler D, Hamed S, Shmilovich H, Deutsch V, Miller H, Keren G, Roth A (2005b) Erythropoietin promotes endothelial progenitor cell proliferative and adhesive properties in a PI 3‐kinase‐dependent manner. Cardiovasc. Res. 68, 299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Herz I, Goldstein E, Abashidze S, Deutch V, Finkelstein A, Michowitz Y, Miller H, Keren G (2003) Number and adhesive properties of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients with in‐stent restenosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, e57–e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghani U, Shuaib A, Salam A, Nasir A, Shuaib U, Jeerakathil T, Sher F, O’Rourke F, Nasser AM, Schwindt B, Todd K (2005) Endothelial progenitor cells during cerebrovascular disease. Stroke 36, 151–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill M, Dias S, Hattori K, Rivera ML, Hicklin D, Witte L, Girardi L, Yurt R, Himel H, Rafii S (2001) Vascular trauma induces rapid but transient mobilization of VEGFR2(+) AC133(+) endothelial precursor cells. Circ. Res. 88, 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R, Lu MM, Narula N, Epstein JA (2002) Smooth muscle cells, but not myocytes, of host origin in transplanted human hearts. Circulation 106, 17–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman S, Zadina K, Moritz T, Ovitt T, Sethi G, Copeland JG, Thottapurathu L, Krasnicka B, Ellis N, Anderson RJ, Henderson W (2004) Long‐term patency of saphenous vein and left internal mammary artery grafts after coronary artery bypass surgery: results from a Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 44, 2149–2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gragasin FS, Xu Y, Arenas IA, Kainth N, Davidge ST (2003) Estrogen reduces angiotensin II‐induced nitric oxide synthase and NAD (P) H oxidase expression in endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Grevenynghe J, Monteiro P, Gilot D, Fest T, Fardel O (2006) Human endothelial progenitors constitute targets for environmental atherogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 341, 763–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisar J, Aletaha D, Steiner CW, Kapral T, Steiner S, Seidinger D, Weigel G, Schwarzinger I, Wolozcszuk W, Steiner G, Smolen JS (2005) Depletion of endothelial progenitor cells in the peripheral blood of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 111, 204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, Kaul M, Yan B, Kridel SJ, Cui J, Strongin A, Smith JW, Liddington RC, Lipton SA (2002) S‐nitrosylation of matrix metalloproteinases: signaling pathway to neuronal cell death. Science 297, 1186–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han CI, Campbell GR, Campbell JH (2001) Circulating bone marrow cells can contribute to neointimal formation. J. Vasc. Res. 38, 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraz M, Jiao C, Hanlon HD, Hartley RS, Schatteman GC (2001) CD34− blood‐derived human endothelial cell progenitors. Stem Cells 19, 304–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori K, Dias S, Heissig B, Hackett NR, Lyden D, Tateno M, Hicklin DJ, Zhu Z, Witte L, Crystal RG, Moore MA, Rafii S (2001) Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietin‐1 stimulate postnatal hematopoiesis by recruitment of vasculogenic and hematopoietic stem cells. J. Exp. Med. 193, 1005–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori K, Heissig B, Wu Y, Dias S, Tejada R, Ferris B, Hicklin DJ, Zhu Z, Bohlen P, Witte L, Hendrikx J, Hackett NR, Crystal RG, Moore MA, Werb Z, Lyden D, Rafii S (2002) Placental growth factor reconstitutes hematopoiesis by recruiting VEGFR1(+) stem cells from bone‐marrow microenvironment. Nat. Med. 8, 841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeschen C, Aicher A, Lehmann R, Fichtlscherer S, Vasa M, Urbich C, Mildner‐Rihm C, Martin H, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S (2003) Erythropoietin is a potent physiologic stimulus for endothelial progenitor cell mobilization. Blood 102, 1340–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss C, Keymel S, Niesler U, Ziemann J, Kelm M, Kalka C (2005) Impaired progenitor cell activity in age‐related endothelial dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 1441–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heissig B, Hattori K, Dias S, Friedrich M, Ferris B, Hackett NR, Crystal RG, Besmer P, Lyden D, Moore MA, Werb Z, Rafii S (2002) Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow niche requires MMP‐9 mediated release of kit‐ligand. Cell 109, 625–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom M, Kalen M, Lindahl P, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C (1999) Role of PDGF‐B and PDGFR‐beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development 126, 3047–3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbrig K, Haensel S, Oelschlaegel U, Pistrosch F, Foerster S, Passauer J (2006) Endothelial dysfunction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a reduced number and impaired function of endothelial progenitor cells. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65, 157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbert B, Chen YX, O’Brien ER (2004) c‐kit‐immunopositive vascular progenitor cells populate human coronary in‐stent restenosis but not primary atherosclerotic lesions. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 287, H518–H524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JM, Syed MA, Arai AE, Powell TM, Paul JD, Zalos G, Read EJ, Khuu HM, Leitman SF, Horne M, Csako G, Dunbar CE, Waclawiw MA, Cannon RO 3rd (2005) Outcomes and risks of granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor in patients with coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 46, 1643–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JM, Zalos G, Halcox JP, Schenke WH, Waclawiw MA, Quyyumi AA, Finkel T (2003) Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillebrands JL, Klatter FA, Van Den Hurk BM, Popa ER, Nieuwenhuis P, Rozing J (2001) Origin of neointimal endothelium and alpha‐actin‐positive smooth muscle cells in transplant arteriosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 107, 1411–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillebrands JL, Onuta G, Rozing J (2005) Role of progenitor cells in transplant arteriosclerosis. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 15, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirashima M, Kataoka H, Nishikawa S, Matsuyoshi N, Nishikawa SI (1999) Maturation of embryonic stem cells into endothelial cells in an in vitro model of vasculogenesis. Blood 93, 1253–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi KK, Rohovsky SA, D’Amore PA (1998) PDGF, TGF‐beta, and heterotypic cell–cell interactions mediate endothelial cell‐induced recruitment of 10T1/2 cells and their differentiation to a smooth muscle fate. J. Cell Biol. 141, 805–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoetzer GL, Irmiger HM, Keith RS, Westbrook KM, Desouza CA (2005) Endothelial nitric oxide synthase inhibition does not alter endothelial progenitor cell colony forming capacity or migratory activity. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 46, 387–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov M, Fach C, Becker C, Heussen N, Liehn EA, Blindt R, Hanrath P, Weber C (2007) Reduced numbers of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients with coronary artery disease associated with long‐term statin treatment. Atherosclerosis 192, 413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov M, Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Liehn EA, Shagdarsuren E, Ludwig A, Weber C (2007) Importance of CXC chemokine receptor 2 in the homing of human peripheral blood endothelial progenitor cells to sites of arterial injury. Circ. Res. 100, 590–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Davison F, Ludewig B, Erdel M, Mayr M, Url M, Dietrich H, Xu Q (2002a) Smooth muscle cells in transplant atherosclerotic lesions are originated from recipients, but not bone marrow progenitor cells. Circulation 106, 1834–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Mayr M, Metzler B, Erdel M, Davison F, Xu Q (2002b) Both donor and recipient origins of smooth muscle cells in vein graft atherosclerotic lesions. Circ. Res. 91, 13e–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Zhang Z, Torsney E, Afzal AR, Davison F, Metzler B, Xu Q (2004) Abundant progenitor cells in the adventitia contribute to atherosclerosis of vein grafts in ApoE‐deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1258–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ii M, Takenaka H, Asai J, Ibusuki K, Mizukami Y, Maruyama K, Yoon Y‐S, Wecker A, Luedemann C, Eaton E, Silver M, Thorne T, Losordo DW (2006) Endothelial progenitor thrombospondin‐1 mediates diabetes‐induced delay in reendothelialization following arterial injury. Circ. Res. 98, 697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi T, Hano T, Nishio I (2005a) Angiotensin II accelerates endothelial progenitor cell senescence through induction of oxidative stress. J. Hypertens. 23, 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi T, Hano T, Nishio I (2005b) Estrogen reduces angiotensin II‐induced acceleration of senescence in endothelial progenitor cells. Hypertens. Res. 28, 263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi T, Hano T, Nishio I (2005c) Estrogen reduces endothelial progenitor cell senescence through augmentation of telomerase activity. J. Hypertens. 23, 1699–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi T, Hano T, Sawamura T, Nishio I (2004) Oxidized low‐density lipoprotein induces endothelial progenitor cell senescence, leading to cellular dysfunction. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 31, 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi T, Kobayashi K, Kuki S, Takahashi C, Akasaka T (2006) Sirolimus accelerates senescence of endothelial progenitor cells through telomerase inactivation. Atherosclerosis 189, 288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi T, Moriwaki C, Hano T, Nishio I (2005d) Endothelial progenitor cell senescence is accelerated in both experimental hypertensive rats and patients with essential hypertension. J. Hypertens. 23, 1831–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Sata M, Hikichi Y, Sohma R, Fukuda D, Uchida T, Shimizu M, Komoda H, Node K (2007) Mobilization of CD34‐positive bone marrow‐derived cells after coronary stent implantation: impact on restenosis. Circulation 115, 553–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishisaki A, Hayashi H, Li AJ, Imamura T (2003) Human umbilical vein endothelium‐derived cells retain potential to differentiate into smooth muscle‐like cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1303–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issarachai S, Priestley GV, Nakamoto B, Papayannopoulou T (2002) Cells with hemopoietic potential residing in muscle are itinerant bone marrow‐derived cells. Exp. Hematol. 30, 366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakura A, Luedemann C, Shastry S, Hanley A, Kearney M, Aikawa R, Isner JM, Asahara T, Losordo DW (2003) Estrogen‐mediated, endothelial nitric oxide synthase‐dependent mobilization of bone marrow‐derived endothelial progenitor cells contributes to reendothelialization after arterial injury. Circulation 108, 3115–3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KA, Mi T, Goodell MA (1999) Hematopoietic potential of stem cells isolated from murine skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14482–14486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalka C, Tehrani H, Laudenberg B, Vale PR, Isner JM, Asahara T, Symes JF (2000) VEGF gene transfer mobilizes endothelial progenitor cells in patients with inoperable coronary disease. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 70, 829–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H‐J, Kim H‐S, Zhang S‐Y, Park K‐W, Cho H‐J, Koo B‐K, Kim Y‐J, Lee D‐S, Sohn D‐W, Han K‐S (2004) Effects of intracoronary infusion of peripheral blood stem‐cells mobilised with granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor on left ventricular systolic function and restenosis after coronary stenting in myocardial infarction: the MAGIC cell randomised clinical trial. Lancet 363, 751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H‐J, Lee H‐Y, Na S‐H, Chang S‐A, Park K‐W, Kim H‐K, Kim S‐Y, Chang H‐J, Lee W, Kang W‐J, Koo B‐K, Kim Y‐J, Lee D‐S, Sohn D‐W, Han K‐S, Oh B‐H, Park Y‐B, Kim H‐S (2006) Differential effect of intracoronary infusion of mobilized peripheral blood stem cells by granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor on left ventricular function and remodeling in patients with acute myocardial infarction versus old myocardial infarction: the magic cell‐3‐DES randomized, controlled trial. Circulation 114, I‐145–I‐151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiec‐Wilk B, Polus A, Grzybowska J, Mikolajczyk M, Hartwich J, Pryjma J, Skrzeczynska J, Dembinska‐Kiec A (2005) beta‐Carotene stimulates chemotaxis of human endothelial progenitor cells. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 43, 488–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Park SY, Kim JM, Kim JW, Kim MY, Yang JH, Kim JO, Choi KH, Kim SB, Ryu HM (2005) Differentiation of endothelial cells from human umbilical cord blood AC133‐CD14+ cells. Ann. Hematol. 84, 417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodali R, Hajjou M, Berman AB, Bansal MB, Zhang S, Pan JJ, Schecter AD (2006) Chemokines induce matrix metalloproteinase‐2 through activation of epidermal growth factor receptor in arterial smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 69, 706–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Hayashi M, Takeshita K, Numaguchi Y, Kobayashi K, Iino S, Inden Y, Murohara T (2004) Smoking cessation rapidly increases circulating progenitor cells in peripheral blood in chronic smokers. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 1442–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D, Melo LG, Gnecchi M, Zhang L, Mostoslavsky G, Liew CC, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ (2004a) Cytokine‐induced mobilization of circulating endothelial progenitor cells enhances repair of injured arteries. Circulation 110, 2039–2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D, Melo LG, Mangi AA, Zhang L, Lopez‐Ilasaca M, Perrella MA, Liew CC, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ (2004b) Enhanced inhibition of neointimal hyperplasia by genetically engineered endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation 109, 1769–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz GA, Liang G, Cuculoski F, Gregg D, Vata KC, Shaw LK, Goldschmidt‐Clermont PJ, Dong C, Taylor DA, Peterson ED (2006) Circulating endothelial progenitor cells predict coronary artery disease severity. Am. Heart J. 152, 190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupatt C, Hinkel R, Lamparter M, Von Bruhl ML, Pohl T, Horstkotte J, Beck H, Muller S, Delker S, Gildehaus FJ, Buning H, Hatzopoulos AK, Boekstegers P (2005) Retroinfusion of embryonic endothelial progenitor cells attenuates ischemia‐reperfusion injury in pigs: role of phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase/AKT kinase. Circulation 112, I117–I122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuyama T, Omura T, Nishiya D, Enomoto S, Matsumoto R, Murata T, Takeuchi K, Yoshikawa J, Yoshiyama M (2006a) The effects of HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitor on vascular progenitor cells. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 101, 344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuyama T, Omura T, Nishiya D, Enomoto S, Matsumoto R, Takeuchi K, Yoshikawa J, Yoshiyama M (2006b) Effects of treatment for diabetes mellitus on circulating vascular progenitor cells. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 102, 96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer H, May AE, Daub K, Heinzmann U, Lang P, Schumm M, Vestweber D, Massberg S, Schonberger T, Pfisterer I, Hatzopoulos AK, Gawaz M (2006) Adherent platelets recruit and induce differentiation of murine embryonic endothelial progenitor cells to mature endothelial cells in vitro . Circ. Res. 98, e2–e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidot T (2001) Mechanism of human stem cell migration and repopulation of NOD/SCID and B2mnull NOD/SCID mice. The role of SDF–1/CXCR4 interactions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 938, 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufs U, Werner N, Link A, Endres M, Wassmann S, Jurgens K, Miche E, Bohm M, Nickenig G (2004) Physical training increases endothelial progenitor cells, inhibits neointima formation, and enhances angiogenesis. Circulation 109, 220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S‐P, Youn S‐W, Cho H‐J, Li L, Kim T‐Y, Yook H‐S, Chung J‐W, Hur J, Yoon C‐H, Park K‐W, Oh B‐H, Park Y‐B, Kim H‐S (2006) Integrin‐linked kinase, a hypoxia‐responsive molecule, controls postnatal vasculogenesis by recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells to ischemic tissue. Circulation 114, 150–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone AM, Rutella S, Bonanno G, Contemi AM, De Ritis DG, Giannico MB, Rebuzzi AG, Leone G, Crea F (2005) Endogenous G‐CSF and CD34(+) cell mobilization after acute myocardial infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. 111, 202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Han X, Jiang J, Zhong R, Williams GM, Pickering JG, Chow LH (2001) Vascular smooth muscle cells of recipient origin mediate intimal expansion after aortic allotransplantation in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 158, 1943–1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl P, Johansson BR, Leveen P, Betsholtz C (1997) Pericyte loss and microaneurysm formation in PDGF‐B‐deficient mice. Science 277, 242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llevadot J, Murasawa S, Kureishi Y, Uchida S, Masuda H, Kawamoto A, Walsh K, Isner JM, Asahara T (2001) HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitor mobilizes bone marrow‐derived endothelial progenitor cells. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majka SM, Jackson KA, Kienstra KA, Majesky MW, Goodell MA, Hirschi KK (2003) Distinct progenitor populations in skeletal muscle are bone marrow derived and exhibit different cell fates during vascular regeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa M, Rosti V, Ferrario M, Campanelli R, Ramajoli I, Rosso R, De Ferrari GM, Ferlini M, Goffredo L, Bertoletti A, Klersy C, Pecci A, Moratti R, Tavazzi L (2005) Increased circulating hematopoietic and endothelial progenitor cells in the early phase of acute myocardial infarction. Blood 105, 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo Y, Imanishi T, Hayashi Y, Tomobuchi Y, Kubo T, Hano T, Akasaka T (2006) The effect of senescence of endothelial progenitor cells on in‐stent restenosis in patients undergoing coronary stenting. Intern. Med. 45, 581–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr M, Li C, Zou Y, Huemer U, Hu Y, Xu Q (2000) Biomechanical stress‐induced apoptosis in vein grafts involves p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinases. FASEB J. 14, 261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr U, Zou Y, Zhang Z, Dietrich H, Hu Y, Xu Q (2006) Accelerated arteriosclerosis of vein grafts in inducible NO synthase (–/–) mice is related to decreased endothelial progenitor cell repair. Circ. Res. 98, 412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney‐Freeman SL, Jackson KA, Camargo FD, Ferrari G, Mavilio F, Goodell MA (2002) Muscle‐derived hematopoietic stem cells are hematopoietic in origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 1341–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud SE, Dussault S, Haddad P, Groleau J, Rivard A (2006) Circulating endothelial progenitor cells from healthy smokers exhibit impaired functional activities. Atherosclerosis 187, 423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami E, Laflamme MA, Saffitz JE, Murry CE (2005) Extracardiac progenitor cells repopulate most major cell types in the transplanted human heart. Circulation 112, 2951–2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minehata K, Mukouyama YS, Sekiguchi T, Hara T, Miyajima A (2002) Macrophage colony stimulating factor modulates the development of hematopoiesis by stimulating the differentiation of endothelial cells in the AGM region. Blood 99, 2360–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra AK, Gangahar DM, Agrawal DK (2006) Cellular, molecular and immunological mechanisms in the pathophysiology of vein graft intimal hyperplasia. Immunol. Cell Biol. 84, 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan NI, Goldschmidt‐Clermont PJ, Parker‐Thornburg J, Shapiro SD, Kolattukudy PE (2000) Contribution of monocytes/macrophages to compensatory neovascularization: the drilling of metalloelastase‐positive tunnels in ischemic myocardium. Circ. Res. 87, 378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Mironov V, Yamagishi T, Nakamura H, Markwald RR (1997) Expression of smooth muscle alpha‐actin in mesenchymal cells during formation of avian endocardial cushion tissue: a role for transforming growth factor beta3. Dev. Dyn. 209, 296–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickenig G, Baumer AT, Grohe C, Kahlert S, Strehlow K, Rosenkranz S, Stablein A, Beckers F, Smits JF, Daemen MJ, Vetter H, Bohm M (1998) Estrogen modulates AT1 receptor gene expression in vitro and in vivo . Circulation 97, 2197–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani K, Egashira K, Ihara Y, Nakano K, Funakoshi K, Zhao G, Sata M, Sunagawa K (2006) Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade attenuates in‐stent restenosis by inhibiting inflammation and progenitor cells. Hypertension 48, 664–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegatta F, Bragheri M, Grigore L, Raselli S, Maggi FM, Brambilla C, Reduzzi A, Pirillo A, Norata GD, Catapano AL (2006) In vitro isolation of circulating endothelial progenitor cells is related to the high density lipoprotein plasma levels. Int. J. Mol. Med. 17, 203–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppel K, Zhang L, Orman ES, Hagen PO, Amalfitano A, Brian L, Freedman NJ (2005) Activation of vascular smooth muscle cells by TNF and PDGF: overlapping and complementary signal transduction mechanisms. Cardiovasc. Res. 65, 674–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillarisetti K, Gupta SK (2001) Cloning and relative expression analysis of rat stromal cell derived factor‐1 (SDF‐1) 1: SDF‐1 alpha mRNA is selectively induced in rat model of myocardial infarction. Inflammation 25, 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell TM, Paul JD, Hill JM, Thompson M, Benjamin M, Rodrigo M, McCoy JP, Read EJ, Khuu HM, Leitman SF, Finkel T, Cannon RO, 3rd (2005) Granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor mobilizes functional endothelial progenitor cells in patients with coronary artery disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauscher FM, Goldschmidt‐Clermont PJ, Davis BH, Wang T, Gregg D, Ramaswami P, Pippen AM, Annex BH, Dong C, Taylor DA (2003) Aging, progenitor cell exhaustion, and atherosclerosis. Circulation 108, 457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza K, Thambyrajah J, Townend JN, Exley AR, Hortas C, Filer A, Carruthers DM, Bacon PA (2000) Suppression of inflammation in primary systemic vasculitis restores vascular endothelial function: lessons for atherosclerotic disease? Circulation 102, 1470–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman J, Li J, Orschell CM, March KL (2003) Peripheral blood ‘endothelial progenitor cells’ are derived from monocyte/macrophages and secrete angiogenic growth factors. Circulation 107, 1164–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Religa P, Bojakowski K, Maksymowicz M, Bojakowska M, Sirsjo A, Gaciong Z, Olszewski W, Hedin U, Thyberg J (2002) Smooth‐muscle progenitor cells of bone marrow origin contribute to the development of neointimal thickenings in rat aortic allografts and injured rat carotid arteries. Transplantation 74, 1310–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risau W (1997) Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature 386, 671–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiura A, Sata M, Hirata Y, Nagai R, Makuuchi M (2001) Circulating smooth muscle progenitor cells contribute to atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 7, 382–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sata M, Saiura A, Kunisato A, Tojo A, Okada S, Tokuhisa T, Hirai H, Makuuchi M, Hirata Y, Nagai R (2002) Hematopoietic stem cells differentiate into vascular cells that participate in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 8, 403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbaa E, Dewever J, Martinive P, Bouzin C, Frerart F, Balligand J‐L, Dessy C, Feron O (2006) Caveolin plays a central role in endothelial progenitor cell mobilization and homing in SDF‐1‐driven postischemic vasculogenesis. Circ. Res. 98, 1219–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeisser A, Garlichs CD, Zhang H, Eskafi S, Graffy C, Ludwig J, Strasser RH, Daniel WG (2001) Monocytes coexpress endothelial and macrophagocytic lineage markers and form cord‐like structures in Matrigel under angiogenic conditions. Cardiovasc. Res. 49, 671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt‐Lucke C, Rossig L, Fichtlscherer S, Vasa M, Britten M, Kamper U, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM (2005) Reduced number of circulating endothelial progenitor cells predicts future cardiovascular events: proof of concept for the clinical importance of endogenous vascular repair. Circulation 111, 2981–2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober A, Hoffmann R, Opree N, Knarren S, Iofina E, Hutschenreuter G, Hanrath P, Weber C (2005) Peripheral CD34+ cells and the risk of in‐stent restenosis in patients with coronary heart disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 96, 1116–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzenberg S, Deutsch V, Maysel‐Auslender S, Kissil S, Keren G, George J (2007) Circulating apoptotic progenitor cells: a novel biomarker in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, e27–e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby F, Rossant J, Yamaguchi TP, Gertsenstein M, Wu XF, Breitman ML, Schuh AC (1995) Failure of blood‐island formation and vasculogenesis in Flk‐1‐deficient mice. Nature 376, 62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Rafii S, Wu MH, Wijelath ES, Yu C, Ishida A, Fujita Y, Kothari S, Mohle R, Sauvage LR, Moore MA, Storb RF, Hammond WP (1998) Evidence for circulating bone marrow‐derived endothelial cells. Blood 92, 362–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Sugiyama S, Aikawa M, Fukumoto Y, Rabkin E, Libby P, Mitchell RN (2001) Host bone‐marrow cells are a source of donor intimal smooth‐ muscle‐like cells in murine aortic transplant arteriopathy. Nat. Med. 7, 738–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani S, Murohara T, Ikeda H, Ueno T, Honma T, Katoh A, Sasaki K, Shimada T, Oike Y, Imaizumi T (2001) Mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 103, 2776–2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simper D, Stalboerger PG, Panetta CJ, Wang S, Caplice NM (2002) Smooth muscle progenitor cells in human blood. Circulation 106, 1199–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]