Abstract

Abstract. Diet plays an important role in promoting and/or preventing colon cancer; however, the effects of specific nutrients remain uncertain because of the difficulties in correlating epidemiological and basic observations. Transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia (TMCH) induced by Citrobacter rodentium, causes significant hyperproliferation and hyperplasia in the mouse distal colon and increases the risk of subsequent neoplasia. We have recently shown that TMCH is associated with an increased abundance of cellular β‐catenin and its nuclear translocation coupled with up‐regulation of its downstream targets, c‐myc and cyclin D1. In this study, we examined the effects of two putatively protective nutrients, calcium and soluble fibre pectin, on molecular events linked to proliferation in the colonic epithelium during TMCH. Dietary intervention incorporating changes in calcium [high (1.0%) and low (0.1%)] and alterations in fibre content (6% pectin and fibre‐free) were compared with the standard AIN‐93 diet (0.5% calcium, 5% cellulose), followed by histomorphometry and immunochemical assessment of potential oncogenes. Dietary interventions did not alter the time course of Citrobacter infection. Both 1.0% calcium and 6% pectin diet inhibited increases in proliferation and crypt length typically seen in TMCH. Neither the low calcium nor fibre‐free diets had significant effect. Pectin diet blocked increases in cellular β‐catenin, cyclin D1 and c‐myc levels associated with TMCH by 70%, whereas neither high nor low calcium diet had significant effect on these molecules. Diets supplemented with either calcium or pectin therefore, exert anti‐proliferative effects in mouse distal colon involving different molecular pathways. TMCH is thus a diet‐sensitive model for examining the effect of specific nutrients on molecular characteristics of the pre‐neoplastic colonic epithelium.

INTRODUCTION

Strategies that reduce the incidence of cancer, in the long run, are much more effective than the development of new treatments for cancer. Epidemiologic studies suggest that environmental factors may be responsible for a majority of colon cancers. Diet is now recognized as an environmental factor that may act both as a major risk in the development of colon cancer and also as a protective factor that reduces its incidence; therefore understanding how diet modulates colon cancer risk has been one of the major goals of gastrointestinal tract cancer prevention. Molecular profiling may be an integral part of understanding nutrient effects. By delineating the correlation among molecular, functional and histological alterations induced by putative risk factors for cancer progression/prevention, we may achieve a more fundamental understanding of the role of nutrients in cancer biology.

Defining specific components of the diet that alter cancer risk and, more specifically, how they alter risk, has been difficult. The complexities of isolating and controlling for individual nutrients in human diets are challenging. Dietary changes, to be effective, must target the earliest stages of colonic cell transformation, before the development of clinically and/or histologically evident tumours. Diets may be effective in only a subset of the population at risk for cancer; a significant effect in a population at risk may be obscured by a lack of effect in the non‐target population (Ma et al. 2001). Defining the specific nutrient in the appropriate amount in the target population at sufficient risk to demonstrate a statistical effect may be a daunting task in clinical studies.

Two nutrients implicated in reducing colon cancer risk are calcium and fibre. Epidemiologic studies have correlated high dietary calcium with a lower incidence of colon cancer. Clinical studies of calcium supplementation have found a reduction in polyp formation (Baron et al. 1999) and in intermediate or surrogate markers of cancer risk (Holt et al. 1998). Calcium‐induced decreases in proliferation were one of the earliest and most frequently identified functional changes in colonic epithelium (Lipkin 1974, 1985). As increased proliferation both precedes and accompanies cancer, it has been used as a functional surrogate for increased risk for neoplasia. Apoptosis may also be an important marker for cancer risk; in addition to its effect on proliferation, calcium also increases apoptotic rates in colonic epithelia (Penman et al. 2000) and has also been shown to alter other potential intermediate markers of increased cancer risk (Lans et al. 1991; Pence et al. 1995).

Calcium may act by binding potential carcinogens in the lumen of the gut or, alternatively, by directly modulating epithelial function. Calcium has a high affinity for complexing bile salts; this may prevent the salts from interacting with colonic epithelium, thus lessening bile‐induced damage and subsequent neoplastic transformation (Newmark et al. 1984; Pence et al. 1995). Calcium also has direct effects on epithelial biology independent of bile salts by modulating crypt kinetics, cell : cell interactions, calcium receptors and intracellular signalling (Nobre‐Leiato et al. 1985; Buras et al. 1995; Kallay et al. 2000). There is considerable evidence, both pro and con, to support either hypothesis. However, there is little information on how calcium may alter specific molecular markers of colon cancer.

Epidemiological and case‐controlled studies have implicated fibre as a potential chemopreventive agent. Recent studies present conflicting results, but a general consensus holds that fibre is probably protective (Kim 2000; Bingham et al. 2003; Ferguson & Harris 2003; Peters et al. 2003). It may be that a specific type of fibre or a component of fibre may have a protective effect that is obscured by measuring total fibre content (Terry et al. 2001; Evans et al. 2002). Several potential protective mechanisms for fibre have been postulated including: intraluminal binding of possible carcinogens, similar to calcium; dilutional effects secondary to increased foecal volume; altered motility; decreased foecal pH; changes in colonic flora; galactose‐binding lectins, and, finally, increasing colonic short‐chain fatty acids (SCFAs) especially butyrate, which has been shown to be a differentiating agent in vitro (Cook & Sellin 1998). Thus, like calcium, fibre may have either luminal or epithelial effects in the colon.

Because different fibres have differing effects on colonic physiology, the design of a dietary intervention study with fibre is necessarily complex. The standard mouse dietary fibre is cellulose, which is poorly metabolized by colonic bacteria, resulting in increases in foecal bulk, potential binding of luminal contents and limited production of SCFAs (acetate, propionate and butyrate). We compared the effects of pectin substitution and a fibre‐free diet to a cellulose‐containing diet. Pectin is a soluble fibre well metabolized by colonic bacteria and is thought to serve as a short‐chain fatty acid delivery system to the colon (Jacobs & Lupton 1984; Dirks & Freeman 1997; Hong et al. 1997). The fibre‐free diet necessarily reduces both colonic bulk and SCFAs. Thus, these three diets may provide an opportunity to assess which components of the ‘fibre effect’ are most relevant in early stages of neoplastic transformation of the colonic epithelia.

Transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia (TMCH)

To be effective, protective dietary interventions must target the earliest stages of neoplastic transformation, modulating molecular and functional alterations associated with carcinogenesis, but prior to the development of adenomas or cancer. Thus, appropriate animal models should exhibit these early functional and molecular changes of the epithelium at risk for colon cancer. TMCH, induced by Citrobacter rodentium (C. rodentium), exhibits increased proliferation and an expanded proliferative zone in Swiss Webster mouse distal colon without associated injury or significant histological inflammation (Barthold et al. 1976; Schauer & Falkow 1993). Variation in commercial rodent diets may alter the degree of proliferation caused by C. rodentium, although the determinant factors have not been identified (Barthold et al. 1977). We have recently shown that TMCH exhibits both functional and molecular changes typical of the earliest stages of neoplastic transformation. Preceding the hyperplasia, cellular β‐catenin increases in abundance and, subsequently, undergoes nuclear translocation. Down‐stream targets of β‐catenin including cyclin‐D1 and c‐myc, increase in abundance (Sellin et al. 2001). Thus, TMCH demonstrates both the functional and molecular changes associated with early stages of neoplastic transformation. TMCH increases the risk of subsequent polyp/cancer development in the Min mouse or mice exposed to the carcinogen 1,2‐dimethylhydrazine (DMH) (Barthold et al. 1977; Newman et al. 2001). We therefore sought to determine if dietary intervention with either calcium or fibre would alter either the functional changes and/or the molecular changes observed in TMCH. We found that both calcium and pectin diets blocked hyperproliferation/hyperplasia associated with TMCH, albeit through different molecular mechanisms.

METHODS

TMCH

TMCH was induced in Helicobacter‐free Swiss‐Webster mice (15–20 g; Harlan) by oral inoculation with a 16‐h culture of C. rodentium, as previously described (Umar et al. 2000). Age‐ and sex‐matched control mice received sterile culture medium only. At day 3, mice were randomized to receive either a control AIN‐93 diet (Reeves et al. 1993) or one of four modified diets synthesized by Harlan Teklad (Madison, WI, USA) (see below). At day 12 after exposure to C. rodentium, animals were killed, colons were harvested, morphological changes in the colon were determined following staining with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and crypts isolated as described previously (Umar et al. 2000).

Diets

The standard AIN‐93 diets we employed contains in g/kg: casein 200, DL‐methionine 3.0, corn starch 347.311, maltodextrin 130, sucrose 160, soybean oil 70, vitamin mix AIN‐93 10, choline bitartrate 2.5, antioxidant TBHQ 0.014, cellulose 50, calcium 12. The calcium modifications included the Ca‐P deficient mineral mix TD 79055 13.37, potassium phosphate monobasic 11.43 with calcium carbonate in either 2.375 (low calcium) or 24.88 (high calcium).

The diets used in the fibre experiments were again modifications of AIN‐93, as noted above, with the following changes: the fibre‐free diet had 395.86 g corn starch, no cellulose, no pectin; the pectin diet had 335.686 g corn starch, 60 g pectin (6% pectin) no cellulose; whereas the control/cellulose diet had 324.806 g corn starch, 50 g cellulose and no pectin. The source of pectin was pure citrus peels, approved as generally recognized as a safe (GRAS) ingredient by the Food and Drug Administration.

The range of calcium and pectin supplementations were relatively modest compared with prior studies using similar nutritional intervention strategies. Fibre‐supplemented diets have been shown to increase colonic SCFAs compared with fibre‐free diets without significantly altered nutrient intake (Chapkin et al. 1993).

Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) and northern blotting to detect intimin

Intimin is a unique protein found in enteroadherent bacteria including C. rodentium and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC). It is not found in normal mouse colonic bacteria and can thus serve as a marker for the presence of Citrobacter. To determine the timecourse of intimin expression as a function of Citrobacter presence during TMCH, and to determine whether diet altered the time course of Citrobacter luminal colonization and therefore the mucosal infectivity, total RNA was isolated from whole distal colon from normal, Citrobacter‐infected (day 9), and Citrobacter‐infected (day 9) mice receiving 6% pectin and 1% Ca2+ diet, respectively. Total RNA samples were reverse transcribed and a 500‐base pair region was amplified by PCR using the following primers: 5′‐TTTGGGACCCTAAATAAG‐3′ (forward) and 5′‐ACCTGCTTTCTGCCTC‐3′ (reverse). The PCR products were analysed on 1.5–2% agarose gels as previously described (Umar et al. 2000).

For northern blot analysis, total RNA was isolated from normal, Citrobacter‐infected (day 9), and Citrobacter‐infected (day 9) mice receiving 6% pectin and 1% Ca2+ diet, respectively, using TRIzol reagent (Gibco‐BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Total RNA (10 µg) was denatured and fractionated on a 1% agarose gel containing formaldehyde. RNA was then transferred to a GeneScreen Plus nylon membrane (DuPont–NEN, Boston, MA, USA), and the blot was hybridized at 60 °C in 10% dextran sulphate, 1 m NaCl, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 100 µg/ml denatured salmon testes DNA, with the use of α‐[32P]dCTP‐labelled probe for intimin (500 bp, 2 × 106 cpm/ml) and subsequently with a probe against glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; bases 163–608, 1 × 106 cpm/ml). The latter signal was used to normalize the mRNA in each lane. The probe for intimin detection was generated by PCR as described (Umar et al. 2000), and the GAPDH probe was generated by RT‐PCR from mouse colonic RNA (Umar et al. 2000). Both were confirmed by oligonucleotide sequencing before random primed labelling.

BrdU labelling and morphometry

Proliferating cells in S‐phase were labelled with 5′‐bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) injected intraperitoneally (at 160 mg/kg body weight) 1 h before killing. To prepare the specimens, 200 µl of freshly isolated crypt suspension were spun onto 1‐oz poly l‐lysine‐coated glass coverslips using a concentrating centrifuge (Shandon Cytospin; Shandon). Adhered crypts were then postfixed at −20 °C with ultrapure methanol (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA, USA) for 40 min, denatured in 2 N HCl at 37 °C for 30 min, and neutralized with 0.1 m sodium borate (pH 8.5) for 10 min. After rinsing, the pre‐treated slides were incubated with a 1 : 1000 dilution of affinity‐purified goat anti‐BrdU antibody (Sigma), at 4 °C overnight. Bound anti‐BrdU antibody was subsequently visualized by immunofluorescence staining with BODIPY FL‐conjugated donkey anti‐goat IgG antibody (Sigma). Fluorescence was viewed using a Noran confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, Noran Instruments, Middleton, WI, USA) equipped with an argon laser and appropriate optics and filter modules for fluorophore detection. Significant differences in the total number of cells per crypt column were seen between normal (∼25 cells), TMCH (70–80 cells) and TMCH + diet groups (20–35 cells). Cells positive for BrdU in each group (ranging between three and 15 cells/crypt column) were counted by fluorescence microscopy.

For measuring crypt length, preserved crypts (200 µl) were spun onto poly l‐lysine‐coated glass coverslips and fixed with Cellfix (Shandon), and images were collected at × 200 magnification with a 12‐bit grey level charge‐coupled device camera connected to an inverted microscope. Crypt length was measured and compared with a standard microscale etched onto a glass slide using Metamorph image analysis software (Universal Imaging Corp., Brandywine Parkway, PA, USA).

Western blotting

Total crypt cellular extracts (30–100 µg protein/lane) were subjected to SDS–PAGE and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The efficiency of electrotransfer was checked by back staining gels with Coomassie Blue and/or by reversible staining of the electrotransferred protein directly on the nitrocellulose membrane with Ponceau S solution. No variability in transfer was noted. De‐stained membranes were blocked with 5% non‐fat dried milk in TBS [20 mm Tris‐HCl and 137 mm NaCl (pH 7.5)] for 1 h at room temperature (21 °C) and then overnight at 4 °C. Immunoantigenicity was detected by incubating the membranes for 1–2 h with the appropriate primary antibodies [0.5–1.0 µg/ml in Tris‐buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS/Tween); Sigma]. These antibodies were: monoclonal anti‐β‐catenin, anti‐γ‐catenin and anti‐proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA, USA), and polyclonal anti‐cyclin D1 and c‐myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). After washing, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated anti‐mouse or anti‐rabbit secondary antibodies, and developed using the ECL detection system (Amersham Corp., Arlington Heights, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

TMCH

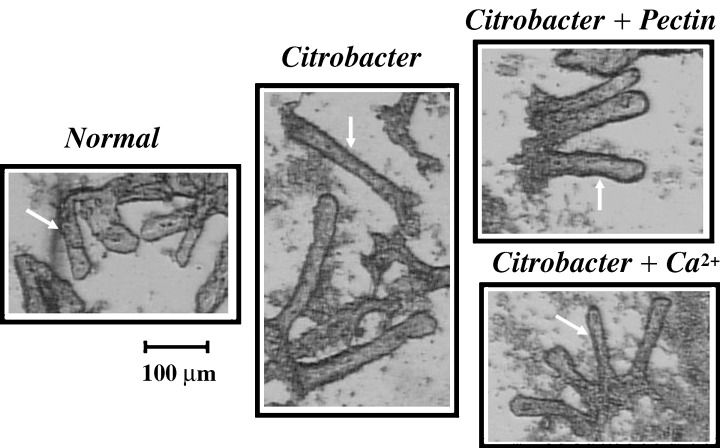

Exposure to C. rodentium led to the characteristic response previously seen in our laboratory (Umar et al. 2000). In wild‐type mice, there was no morbidity nor mortality associated with TMCH. Gross thickening of the distal colon was initially observed 6 days after infection. At 12 days post infection, the distal colon was remarkably thickened, with minimal changes in the proximal colon and no changes noted in the small intestine. Microscopically, there was marked crypt hypertrophy with no evident changes in either the inflammatory component in the subepithelium nor of the muscular layers of the colon. In examining isolated crypts, the differences in crypt lengths were apparent (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of TMCH and diets on isolated crypts. Colonic crypts from distal colon of normal mice, Citrobacter‐infected mice at day 12 TMCH, Citrobacter‐infected mice on either a 6% pectin diet or a high‐calcium diet, were isolated as described in METHODS (crypts are marked with arrows). TMCH crypts essentially doubled in length compared with normal mice; dietary interventions reversed this elongation. Detailed morphometry is presented in Table 2.

Dietary intervention: no change in intimin expression

Three days after exposure to Citrobacter rodentium, mice in the experimental groups were given diets with either high (1.0%) or low (0.1%) calcium or diets with altered fibre (either pectin or no fibre). The dietary changes were made 3 days after exposure because previous studies had shown that, at that point (72 h after infection), the epithelial response to Citrobacter was entrained and could not be altered by antibiotics or other intervention. Hyperproliferation and hyperplasia continue for weeks in the absence of the bacterium (Barthold et al. 1976).

Animals in every group tolerated the diet changes well. Weight gain was similar in each group (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of differing diets on weight gain. Animals from five dietary treatment groups were weighed on day 3 after infection with Citrobacter rodentium, the time of the change in diets and weighed on day 10 and prior to killing on day 12. There were no significant differences among groups.

There was no evident change in behaviour or morbidity or mortality with the dietary interventions. Distal colons from control animals not infected with C. rodentium fed either the high‐calcium diet or the pectin diet for 12 days did not demonstrate changes in PCNA, β‐catenin or cyclin D1 expression (Fig. 3). Thus, diet modification by itself did not alter any of the critical molecular markers involved in TMCH‐induced hyperproliferation.

Figure 3.

Effect of dietary intervention on normal colon. Western blots performed in total crypt extracts prepared from uninfected mice on a standard AIN93, 6% Pectin or 1% Ca2+ diets, did not show any alterations in PCNA, β‐catenin or cyclin D1 expression.

To confirm that the change in diet did not alter the course of the Citrobacter infection, we assayed the colon for the presence of intimin gene product by RT–PCR and northern blotting. Intimin is an integral component of the attaching and effacing mechanism by which Citrobacter adheres to the colonic epithelium. It is also found in EPEC and other human pathogens, but is not present in normal colonic flora of the mouse (Luperchio & Schauer 2001).

We first defined the time course of intimin gene expression in TMCH, demonstrating that it is present through day 9 of C. rodentium infection on control diets (Fig. 4a). We next examined whether a change in diet altered expression at day 9. Figure 4(b) demonstrates that intimin expression in colonic epithelium during TMCH was not altered by either a high calcium diet or the pectin diet, i.e. intimin expression was observed at day 9 in presence of both pectin and high calcium diets. To further strengthen these findings, northern blotting was carried out to detect presence of the intimin transcript in pectin and calcium diet‐fed animals. Neither pectin nor calcium diet interfered with the C. rodentium infectivity process as the intimin transcript was detected in the colonic mucosa of animals fed either of these diets (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

Time course and effect of dietary intervention on intimin gene expression during TMCH. (a) Citrobacter rodentium‐encoded intimin gene expression was measured by RT–PCR, in distal colon from mice on a control diet. Intimin expression was absent in normal colon (lane 1). While day 9 TMCH colon (lane 2) expressed intimin, neither day 12 or day 15 TMCH colon expressed detectable intimin (lanes 3 and 4, respectively), indicating lack of bacterial presence at peak hyperplasia (day 12). To determine whether dietary interventions affected Citrobacter infectivity, intimin expression was measured either by RT–PCR (b), or northern blotting (c) of total RNA extracted from normal (lane 1), Citrobacter (lane 2), Citrobacter + 6% pectin (lane 3) or Citrobacter + 1% Ca2+ (lane 4)‐treated whole distal colon. Lane 5 in (b) is no cDNA control. Intimin expression was not affected by either high pectin or calcium diets (n = 2).

This documents that the time course for bacterial colonization/mucosal adherence to the epithelium was similar under varying diets. Thus, the dietary changes did not alter the course of Citrobacter infection in the colon of mice fed different diets.

Pectin diet inhibits proliferation and hyperplasia

We compared the effects of regular AIN‐93 animal chow containing the insoluble fibre cellulose, with a fibre‐free diet and a diet containing the soluble fibre pectin, on TMCH. These studies demonstrated that Citrobacter‐infected mice consuming the pectin‐containing diet exhibited a lack of both the gross or microscopic changes expected in TMCH. On gross inspection, the colons appeared similar to uninfected mice. Detailed morphometry confirmed these changes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of pectin on crypt morphometry

| Fibre | Citrobacter | Crypt length |

|---|---|---|

| 5% cellulose | – | 177.9 ± 27.2a a |

| 5% cellulose | + | 300.1 ± 24.7b |

| Fibre‐free | + | 300.1 ± 19.1b |

| Pectin | + | 158.9 ± 23.8a a |

a is significantly different from b, P < 0.05; n = 5.

The fibre‐free fed animals followed the typical course of crypt elongation seen in TMCH. This serves as an important control, indicating that it is not absence of the insoluble fibre (i.e. roughage) per se that is inhibitory, but rather that pectin or one of its metabolic products is responsible for the blunted proliferative response.

Not unexpectedly, the proliferative indices paralleled the morphometry. TMCH, as noted above, causes an increase in the proliferative index. It also leads to an expansion of the proliferative zone. In normal crypts, active cell division is restricted to the base of the crypt. In TMCH, as in other pre‐malignant conditions, there is an expansion of the proliferative zone to occupy 40–50% of the length of the crypt (Lipkin 1974; Nobre‐Leiato et al. 1985; Papatis et al. 1998). There was decreased BrdU labelling/crypt in the pectin‐fed animals compared with those either on the control or fibre‐free diets exposed to TMCH (Table 2). PCNA ratio (representing relative cellular optical density of PCNA, normalized to housekeeping protein actin), also decreased in the distal colon of pectin‐fed animals mimicking the normal condition (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of pectin on cell proliferation

| Diet | Citrobacter | BrdU + cells/crypt | % crypt labelled | PCNA (ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | + | 10 ± 2.0 | 40 ± 3.0 | 2.0 |

| Fibre‐free | + | 11.4 ± 3.1 | 50 ± 7.0 | ND |

| Pectin | + | 3.0 ± 1.0 a | 20 ± 3.0 | 1.4 |

P < 0.05; n = 5; ND, not determined.

High calcium diet also inhibits hyperplasia and proliferation

Parallel studies were performed in animals exposed to different calcium diets. Grossly, mouse colon from TMCH animals on a high‐calcium (1.0%) diet did not have the obvious thickening of the distal colon compared with animals on a normal‐(0.5%) calcium diet. In contrast, colons from infected mice on a low‐(0.1%) calcium diet appeared similar to TMCH mice on a normal‐calcium diet. The high‐calcium diet did not totally block TMCH‐induced crypt extension, but appeared microscopically to blunt the change. Morphometry confirmed this, demonstrating that the mean number of cells/crypt were significantly less than TMCH controls (Fig. 1, Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of Ca2+ on crypt morphometry and proliferation

| Diet | Citrobacter | Crypt length | BrdU + cells/crypt | PCNA (ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | – | 243 ± 49.0 | ND | 1.0 |

| Control | + | 484 ± 77.0 | 10 ± 1.6 | 2.0 |

| 0.1% Ca2+ | + | ND | 9.8 ± 2.0 | ND |

| 1% Ca2+ | + | 300 ± 55.0 | 2.6 ± 0.7 a | 1.2 |

P < 0.05; n = 5; ND, not determined.

TMCH results in an increase in BrdU labelling per crypt compared with controls. The high calcium diet led to a significant decrease in the proliferative index as determined by BrdU labelling. This was confirmed by parallel measurements of PCNA, which is an alternative indicator of epithelial cell proliferation. Similar results were observed in three separate sets of mice.

Changes in catenin abundance

We have previously demonstrated that β‐catenin, a proliferative oncogene, increases in abundance early in the course of TMCH (Sellin et al. 2001). We therefore asked how pectin or calcium might affect the increase in β‐catenin cellular protein levels. Figure 5 demonstrates that the two nutrients had dissimilar effects.

Figure 5.

Effects of dietary intervention on cellular β‐catenin protein abundance. Western blots were performed in uninfected animals on a control diet (lane 1); Citrobacter‐infected animals on a control diet (lane 2); Citrobacter‐infected animals on a fibre‐free diet (lane 3); Citrobacter‐infected animals on a 0.1% calcium diet (lane 4); Citrobacter‐infected animals on a 1.0% calcium diet (lane 5); and Citrobacter infected animals on a 6% pectin diet. Results were normalized to actin. γ‐catenin, an adhesion molecule without oncogenic potential, was employed as a control. Results demonstrate a 70% inhibition of β‐catenin abundance comparing the pectin to the control diet. The high‐calcium diet was associated with a modest 15% inhibition of β‐catenin protein abundance. There was small decrease in γ‐catenin abundance (13–26%). This blot is representative of n = 3 groups of nine animals.

The pectin diet blocked the increase in β‐catenin protein levels associated with TMCH by 70%. In contrast, in animals on a high‐calcium diet, the increase in β‐catenin was minimally altered (15% inhibition) compared with those mice on control diets. We employed γ‐catenin as a control. Like β‐catenin, γ‐catenin has an important role as an adhesion molecule, but is not recognized as an oncogene. We have previously shown that TMCH does not alter γ‐catenin levels (Sellin et al. 2001). Dietary intervention with either calcium or pectin did not significantly alter γ‐catenin abundance in TMCH (Fig. 5). Thus, although both calcium and pectin inhibit the proliferative response of TMCH, they appear to follow different molecular mechanisms.

Changes in down‐stream targets

β‐catenin associates with and activates the T‐cell factor (Tcf)/lymphoid enhancing factor (LEF) family of transcription factors, resulting in the increased transcription of several oncogenes (Barker et al. 2000). Cyclin D1 and c‐myc are two such downstream targets of β‐catenin that have been implicated as effectors of the proliferative response of β‐catenin (He et al. 1998; Shtutman et al. 1999). Cyclin D1 and c‐myc are subject to multiple regulatory factors in addition to β‐catenin. We therefore sought to determine whether there was a linkage between the nutrient‐induced changes in β‐catenin and the abundance of either cyclin D1 or c‐myc in TMCH. Figure 6 shows that the pectin diet inhibited the increases in abundance of both cyclin D1 and c‐myc by 70%, whereas the calcium diet did not have significant inhibitory effect.

Figure 6.

Effects of dietary interventions on cyclin D1 and c‐myc abundance. Western blots were performed to measure the effect of changes in fibre and calcium on the previously demonstrated changes in these molecules at day 12 in the TMCH colon. The expected increase in basal cyclin D1 on a control diet (lane 5) to day 12 TMCH (lane 6) was seen. There were no significant changes induced by fibre‐free (lane 1) or changes in calcium content (0.1% Ca2+, lane 2: 1.0% Ca2+, lane 3). In contrast, there was a major decrease in cyclin D1 abundance on the pectin diet (lane 4, 70% inhibition). A similar pattern was seen when c‐myc protein abundance was compared in fibre‐free (lane 1), 0.1% calcium (lane 2), 1.0% calcium (lane 3) and pectin (lane 4). The increase in c‐myc on the pectin diet was inhibited by 70% (n = 3 groups of nine animals).

Thus, in these dietary interventions in TMCH, there appears to be a causal, not casual, association between changes in β‐catenin and cyclin D1/c‐myc. The differing effects of calcium and pectin on both β‐catenin and cyclin‐D1/c‐myc suggest that these two nutrients exert their anti‐proliferative effects through alternative molecular pathways.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that: (i) TMCH is a diet‐sensitive model for examining the effect of specific nutrients on both functional and molecular characteristics of the preneoplastic epithelium, (ii) both calcium and pectin exert anti‐proliferative effects in mouse colon, but (iii) these effects involve different molecular events.

TMCH is an appropriate model to examine the functional and molecular alterations associated with neoplastic transformation. The progression from a normal epithelium to cancer involves a series of predictable molecular changes, but is a stochastic rather than an ineluctable process (Fearon & Vogelstein 1990). In other words, each step in the pathway, be it molecular, functional or histological, increases the likelihood of progression to cancer but does not make it inevitable. Each step provides a necessary background that increases the odds of subsequent changes. Both molecular (Min mouse) or chemical (DMH) risk factors increase progression to neoplasia in the TMCH colon, thus demonstrating its suitability for early intervention studies (Barthold et al. 1977; Newman et al. 2001).

We focused on increased proliferation as a functional intermediate marker. TMCH clearly exhibits both increased epithelial proliferation and an expanded proliferative zone, both of which have often been utilized as a surrogate for increased cancer risk (Lipkin 1974; Nobre‐Leiato et al. 1985). In epithelia with a carefully regulated cell census, changes in proliferation are generally balanced by changes in apoptosis. In TMCH, the apoptotic index does not increase as one might expect (Umar et al. 2000), thus raising the possibility that there may also be an inhibition of apoptosis. However, it is problematic to prove that the lack of a reasonably expected increase in apoptosis is actually inhibition. This imbalance between proliferation and apoptosis results in significant crypt hyperplasia.

We studied β‐catenin as a molecular marker of cancer risk. Alterations in β‐catenin abundance and cellular distribution are one of the earliest and most predictable changes in neoplastic transformation of the colonic epithelium (Peifer 1997). We have shown that there is a fourfold increase in β‐catenin by day 12 of TMCH and that β‐catenin translocates to the nucleus (Sellin et al. 2001). These changes, to our knowledge, have not been observed in non‐neoplastic tissues. If β‐catenin elevation is pivotal to carcinogenesis, then strategies that can either counteract or circumvent the biological effect would be critical to a prevention strategy.

Dietary intervention has a significant effect in the TMCH model. Barthold et al. found that four standard commercial rodent chows modified both control and TMCH‐induced crypt length; however, they were unable to identify a specific nutrient that might explain the variability (Barthold et al. 1977). We found that substituting a soluble fibre (pectin) for an insoluble fibre (cellulose) altered epithelial kinetics significantly. However, the absence of fibre (i.e. fibre‐free diets) did not have the same effects as soluble fibre. The magnitude of these dietary changes are within a physiologic range. Prior studies examining the effect of pectin, for example, increased the percent intake to the 10–15% range or higher (Chapkin et al. 1993; Folino et al. 1995; Tamura & Suzuki 1997; Avivi‐Green et al. 2000). In the present studies, pectin simply replaced another dietary fibre, cellulose. Similarly, the high calcium diet, which had a significant anti‐proliferative effect, represented a doubling of calcium intake from 0.5 to 1.0%. Thus, these are relatively modest alterations that may be clinically applicable.

Both pectin and calcium have significant anti‐proliferative effects in TMCH (see Fig. 1, 1, 2, 3). These effects are likely to be directly on the epithelium although it is impossible to exclude possible subtle changes in the intraluminal environment. Citrobacter is an enteroadherent bacterium that initiates TMCH by attaching to the epithelium of the distal colon. The detection of the intimin gene expression in the colonic mucosa through day 9 of TMCH animals, independent of diet, demonstrates that the bacterial attachment to the mucosa was not altered (see Fig. 4). This indicates that changes in diet exerted their anti‐proliferative effects through alterations in epithelial biology rather than the carriage of the Citrobacter.

Calcium has been hypothesized to act indirectly by complexing bile salts (Newmark et al. 1984), but low fat diets such as those employed in this study tend to minimize the role/effect of bile salts (Sitrin et al. 1991). Although fibre in general, particularly bran or insoluble fibres, may have multiple effects on the colon, the possible colonic action of soluble fibre such as pectin are more limited. Because of its efficient bacterial degradation, pectin is less likely to bind carcinogens, bulk stool or dilute luminal contents. It is probable that the pectin effect is mediated by its metabolic products, primarily short‐chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Pectin increases colonic SCFAs, primarily in the proximal colon, but has biologic effects in both proximal and distal colon (Cook et al. 1998; Avivi‐Green et al. 2000). Previous studies have associated the effects of pectin with SCFAs primarily butyrate (Avivi‐Green et al. 2000; Musch et al. 2001); however, direct correlations between dietary pectin, colonic SCFAs, morphometry and specific biologic effect are complex (Jacobs et al. 1984; Yajima & Sakata 1992; Dirks et al. 1997; Hong et al. 1997; Wang & Friedman 1998). The finding that butyrate enemas duplicate some well‐defined effects of dietary pectin provide strong evidence that the pectin effect is via SCFAs (Avivi‐Green et al. 2000).

Very few studies have examined the effect of diet on specific molecular markers. This study clearly demonstrates that the pectin diet abrogates the increases in β‐catenin abundance and of potential downstream effectors, cyclin D1 and c‐myc (see 5, 6). In contrast, calcium's anti‐proliferative action appears to be independent of β‐catenin. The lack of changes in cyclin D1 and c‐myc in animals on the high‐calcium diet corresponds with an effect independent of β‐catenin. As a corollary, given the multiple potential regulators of cyclin D1 and c‐myc, the linked changes seen with pectin indicate that they are indeed causally linked to β‐catenin related transcription. Thus, seemingly similar phenotypic effects of nutrients on proliferation and colonic histology may have very different underlying molecular alterations. These differences emphasize both the importance and utility of examining the effects of nutrients not only on histological changes, but correlating those with molecular profiles of the epithelium.

This study does not establish the specific link between the change in nutrient intake and the effects on the epithelium; further studies will be required to delineate these mechanisms. One would assume that the site of action of pectin is an early step in the process that modulates β‐catenin homeostasis, either by altering synthesis, cellular distribution (Barshishat et al. 2000) or degradation (Avivi‐Green et al. 2000). Indeed, high pectin diets have been shown to increase caspases in the distal colon which may accelerate β‐catenin degradation (Avivi‐Green et al. 2000). If SCFAs are indeed the mediators of the pectin effect, they are recognized as pleuripotential agonists for the colonic epithelium that could act on multiple potential targets in the pathway(s) of malignant transformation. In contrast, calcium may activate an inhibitory pathway that either blocks the effects of cyclin D1/c‐myc or activates an alternative pathway that inhibits proliferation independent of the β‐catenin induced mechanisms (Yang et al. 2001). One such possible pathway is the calcium‐sensing receptor found on colonic epithelial cells that regulates protein kinase C activity, another potential regulator of proliferation (1997, 2000).

TMCH in context

These dietary intervention studies provide important insight into the molecular mechanisms associated with increased proliferation in TMCH. This is, to our knowledge, the first study demonstrating that a specific nutrient can down‐regulate the abundance of a specific oncogene. Intervention studies are plagued by the difficulty of determining whether associations are casual or causal. The parallel changes induced by specific nutrients in molecular and functional properties of the epithelium (β‐catenin and cyclin D1/c‐myc) suggest that the β‐catenin effect is linked mechanistically to these downstream oncogenes. Future studies will be aimed at characterizing the specific molecular links between nutrients and the early stages in neoplastic transformation of the colonic epithelium.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Mr Michael Burke for his generous contribution. This work was also supported by a grant from Cancer Research Foundation of America, and by University of Texas Dean's Development Fund.

REFERENCES

- Avivi‐Green C, Madar A, Schwarz B (2000) Pectin‐enriched diet affects distribution and expression of apoptosis‐cascade proteins in colonic crypts of dimethylhydrazine‐treated rats. Int. J. Mol. Med. 6, 689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Morin PJ, Clevers H (2000) The yin‐yang of TCF‐β‐catenin signaling. Adv. Cancer Res. 77, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron JA, Beach M, Mandel JS, Van Stolk RU, Haile RW, Sandler RS, Rothstein R, Summers RW, Snover DC, Beck GJ, Bond JH, Greenberg ER (1999) Calcium supplements for the prevention of colorectal adenomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 340, 101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barshishat M, Polak‐Charcon S, Schwartz B (2000) Butyrate regulates E‐cadherin transcription, isoform expression and intracellular position in colon cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 82, 195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthold SW, Jonas AM (1977) Morphogenesis of early 1,2 dimethylhydrazine‐induced lesions and latent period reduction of colon carcinogenesis in mice by a variant Citrobacter freundii . Cancer Res. 37, 4352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthold SW, Coleman GL, Bhatt PN, Osbaldiston GW, Jonas AM (1976) The etiology of transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Laboratory Anim. Sci. 25, 889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthold SW, Osbaldiston GW, Jonas AM (1977) Dietary, bacterial, and host genetic interactions in the pathogenesis of transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Laboratory Anim Sci. 27, 938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham SA, Day NE, Luben R, Ferrari P, Slimani N, Norat T, Clavel‐Chapelon F, Kesse E, Nieters A, Boeing H, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Martinez C, Dorronsoro M, Gonzalez. CA, Key TJ, Trichopoulou A, Naska A, Vineis P, Tumino R, Krogh V, Bueno‐de‐Mesquita HB, Peeters PH, Berglund G, Hallmans G, Lund E, Skeie G, Kaaks R, Riboli E (2003) Dietary fibre in food and protection against colorectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): an observational study. Lancet 361, 1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buras RR, Shabahang M, Davoodi F, Schumaker LM, Cullen KJ, Byers S, Nauta RJ, Evans SRT (1995) The effect of extracellular calcium on colonocytes: evidence for differential responsiveness based upon degree of cell differentiation. Cell Prolif. 28, 245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapkin RS, Gaso J, Lee D, Lupton JR (1993) Dietary fibers and fats alter rat colon protein kinase C activity: correlation to cell proliferation. J. Nutr. 123, 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook S, Sellin JH (1998) Short‐chain fatty acids in health and disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 12, 499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirks P, Freeman HJ (1997) Effects of differing purified cellulose, pectin and hemicellulose fiber diets on mucosal morphology in the rat small and large intestine. Clin. Invest. Med. 10, 32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RC, Fear S, Ashby D, Hackett A, Williams E, Van Der Vliet M, Dunstan FDJ, Rhodes JM (2002) Diet and colorectal cancer: an investigation of the lectin/galactose hypothesis. Gastroenterology 122, 1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon ER, Vogelstein B (1990) A genetic model for tumorigenesis. Cell 61, 759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson LR, Harris PJ (2003) The dietary fiber debate: more food for thought. Lancet 361, 1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folino M, McIntrye A, Young GP (1995) Dietary fibers differ in their effects on large bowel epithelial proliferation and fecal fermentation‐dependent events in rats. J. Nutr. 125, 1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He TC, Sparks AB, Rago C, Hermeking H, Zawel L, Da Costa LT, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW (1998) Identification of c‐MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science 281, 509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt PR, Atillasoy PO, Gilman J, Guss J, Moss SF, Newmark H, Fank Yang K, Lipkin M (1998) Modulation of abnormal colonic epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation by low‐fat dairy foods: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 280, 1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong MY, Chang WC, Chapkin RS, Lupton JR (1997) Relationship among colonocyte proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis as a function of diet and carcinogen. Nutr. Cancer 28, 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs LR, Lupton JR (1984) Effect of dietary fibers on rat large bowel mucosal growth and cell proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. 246, G378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallay E, Kifor O, Chattopadhyay N, Brown EM, Bischof MG, Peterlik M, Cross HS (1997) Calcium‐dependent c‐myc proto‐oncogene expression and proliferation of Caco‐2 cells: a role for a luminal extracellular calcium‐sensing receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 232, 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallay E, Bajna E, Wrba F, Kriwanek S, Peterlik M, Cross HS (2000) Dietary calcium and growth modulation of human colon cancer cells: role of the extracellular calcium‐sensing receptor. Cancer Detection/Prevention 24, 127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YI (2000) AGA technical review: impact of dietary fiber on colon cancer occurrence. Gastroenterology 118, 1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lans J, Jaszewski R, Arlow FL, Tureaud J, Luk GD, Majumdar AP (1991) Supplemental calcium suppresses colonic mucosal ornithine decarboxylase activity in elderly patients with adenomatous polyps. Cancer Res. 51, 3416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkin M (1974) Phase 1 and phase 2 proliferative lesion of colonic epithelial cells in diseases leading to colonic cancer. Cancer 34, 878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkin M (1985) New mark HL – calcium proliferation in familial colon cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 313, 1381 – 1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luperchio SA, Schauer DB (2001) Molecular pathogenesis of Citrobacter rodentium and transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Microbes Infect. 3, 333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Giovannucci E, Pollak M, Chan JM, Gaziano JM, Willett W, Stampfer MJ (2001) Milk intake, circulating levels of insulin‐like growth factor‐I and risk of colorectal cancer in men. J. Natl Cancer Inst 93, 1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musch MW, Bookstein C, Xie Y, Sellin JH, Chang EB (2001) SCFA increase intestinal Na absorption by induction of NHE3 in rat colon and human intestinal C2/bbe cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 280, G687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JV, Kosaka T, Sheppard BJ, Fox JG, Schauer DB (2001) Bacterial infection promotes colonic tumorigenesis in APC (Min/+) mice. J. Infect. Dis. 184, 227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark HL, Wargovich MJ, Bruce MR (1984) Colon cancer and dietary fat, phosphate and calcium: a hypothesis. J. Natl Cancer Inst 72, 1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre Leiato C, Chaves P, Fidalgo P, Cravo M, Gouveia‐Oliveira A, Ferra MA, Mira FC (1985) Calcium regulation of colon crypt cell kinetics: evidence for a direct effect in mice. Gastroenterology 109, 498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papatis GA, Zizi A, Chlouverakis GJ, Giannikaki ES, Vasilakaki T, Elemenoglou E, Karamanolis DG (1998) Proliferative patterns of rectal mucosa as predictors of advanced colonic neoplasms in routinely processed rectal biopsies. Am. J. Gastro. 93, 1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peifer M (1997) β‐catenin as oncogene: the smoking gun. Science 275, 1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BC, Dunn DM, Zhao C, Landers M, Wargovich MJ (1995) Chemopreventive effects of calcium but not aspirin in cholic acid promoted carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 6, 757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penman ID, Liang QL, Bode J, Eastwood MA, Arends MJ (2000) Dietary calcium supplementation increases apoptosis in the distal murine colonic epithelium. J. Clin. Path. 53, 302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters U, Sinha R, Chatterjee N, Subar AF, Ziegler RG, Kulldorff M, Bresalier R, Weissfeld JL, Flood A, Schatzkin A, Hayes RB (2003) Dietary fibre and colorectal adenoma in a colorectal cancer early detection programme. Lancet 361, 1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC (1993) AIN‐93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition Ad Hoc Writing Committee on the Reformulation the AIN‐76A Diet. J. Nutr. 123, 1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer DB, Falkow S (1993) The eae gene of Citrobacter freundii biotype 4280 is necessary for colonization in transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Infect. Immun. 61, 4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin JH, Umar S, Xiao J, Morris AP (2001) Increased β‐catenin expression and nuclear translocation accompany cellular hyperproliferation in vivo . Cancer Res. 61, 2899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtutman M, Zhurinsky J, Simcha I, Albanese C, D’Amico M, Pestell R, Ben‐Ze’ev A (1999) The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the β‐catenin/Lef‐1 pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 96, 5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitrin MD, Halline AG, Abrahams C, Brasitus TA (1991) Dietary calcium and vitamin D modulate 1,2 dimethylhydrazine‐induced colonic carcinogenesis in the rat. Cancer Res. 51, 5608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura M, Suzuki H (1997) Effects of pectin on jejunal and ileal morphology and ultrastructure in adult mice. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 41, 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry P, Govannucci E, Michels KB, Bergkvist L, Hansen H, Holmberg L, Wolk A (2001) Fruit, vegetables, dietary fiber and the risk of colorectal cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst 93, 525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umar S, Scott J, Sellin J, Dubinsky SP, Morris AP (2000) Murine colonic mucosa hyperproliferation: (1) Elevated CFTR expression and enhanced cAMP‐dependent Cl secretion. Am. J. Physiol. 278, G753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Friedman EA (1998) Short‐chain fatty acids induce cell cycle inhibitors in colonocytes. Gastroenterology 114, 940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yajima T, Sakata T (1992) Core and periphery concentrations of short‐chain fatty acids in luminal contents of the rat colon. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 103, 353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WC, Velich MJ, Edelmann W, Kucherlapati R, Lipkin M, Yang K, Augenlicht LH (2001) Targeted inactivation of the p21 (WAF1/cip1) gene enhances Apc‐initiated tumor formation and the tumor‐promoting activity of a Western‐style high‐risk diet by altering cell maturation in the intestinal mucosal. Cancer Res. 61, 565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]