Abstract

Abstract. Objectives: In this study, we quantify growth variability of tumour cell clones from a human leukaemia cell line. Materials and methods: We have used microplate spectrophotometry to measure growth kinetics of hundreds of individual cell clones from the Molt3 cell line. Growth rate of each clonal population has been estimated by fitting experimental data with the logistic equation. Results: Growth rates were observed to vary between different clones. Up to six clones with growth rates above or below mean growth rate of the parent population were further cloned and growth rates of their offspring were measured. Distribution of growth rates of the subclones did not significantly differ from that of the parent population, thus suggesting that growth variability has an epigenetic origin. To explain observed distributions of clonal growth rates, we have developed a probabilistic model, assuming that fluctuation in the number of mitochondria through successive cell cycles is the leading cause of growth variability. For fitting purposes, we have estimated experimentally by flow cytometry the average maximum number of mitochondria in Molt3 cells. The model fits nicely observed distributions in growth rates; however, cells in which mitochondria were rendered non‐functional (ρ0 cells) showed only 30% reduction in clonal growth variability with respect to normal cells. Conclusions: A tumour cell population is a dynamic ensemble of clones with highly variable growth rates. At least part of this variability is due to fluctuations in the initial number of mitochondria in daughter cells.

INTRODUCTION

The last decades have been characterized by intense research into the molecular genetics of cancer cells. A huge amount of knowledge has been accumulated on various molecular details of tumour initiation, promotion and progression, starting from the central discovery of oncogenes and multistep carcinogenesis (Weinberg 1989). More recently, some researchers have also endeavoured to understand the interplay between tumour cells and their surrounding microenvironment, the latter including normal cells and a plethora of molecular signals that both tumour and non‐tumour cells exchange (Hanahan & Weinberg 2000; Fidler 2002). These signals can modify the individual tumour cell's activity acting, for example, on the expression of genes, and there is also growing evidence that normal cells exert epigenetic control on neoplastic behaviour (Barcellos‐Hoff 2001). It is now clear that tumour initiation, promotion and progression compose a complex mixture of events taking place at both the individual cell and at cell population levels (Hanahan & Weinberg 2000; Barcellos‐Hoff 2001; Fidler 2002), whereby normal cells, tumour cells and their microenvironments represent a non‐reducible ecosystem (see Chignola et al. 2006, and references cited therein).

Heterogeneity of growth kinetics of individual tumours is a known biological fact observed both in vitro and in vivo (Laird 1969; Norton 1985; Chignola et al. 1995; Wilson 2001). Furthermore, studies on individual growth of three‐dimensional tumour cell cultures (spheroids) under controlled conditions have revealed that tumour cells are per se an adaptive, self‐organizing complex biosystem (Deisboeck et al. 2001) and show unexpected emerging growth behaviours such as oscillations of the spheroid volume (Chignola et al. 1999). These observations have important implications if one takes into account well‐known relationships existing between kinetic heterogeneity of tumour growth and outcome of antineoplastic treatments (Laird 1969; Norton 1985; Chignola et al. 1995; Wilson 2001). There is, however, a scarcity of studies on quantitative aspects of tumour growth variability (with some notable exceptions; Fidler 2002; Rubin 2005; references cited therein) and on explanations of its origin at the cellular or subcellular level.

Recently, speed of convergence towards asynchronous state of two human tumour cell populations has been measured by means of an elegant flow cytometry method (Chiorino et al. 2001). The results imply that duration of the cell cycle varies through generations in these tumour cell populations and, indeed, observed variance around the mean cell cycle length was high (coefficient of variation (CV) ≈18% and 25% for Molt4 and Igrov cells, respectively). We reasoned that if the variability of cell cycle duration were a ‘sufficiently’ stable trait – that is if the duration did not change too much at each cell division – then the variability should propagate to daughter cells from individual clones. Thus, cell populations from individual clones (which we refer to as clonal populations) should show different growth rates; measuring these growth rates would require an experimental method that fulfils the following conditions:

-

1

It should allow the measurement of growth of small cell populations.

-

2

It should only minimally perturb cell growth.

-

3

For statistical purposes, it should be applied to measure growth of a high number of clonal populations.

Conventional methods for determination of cell population size, such as direct cell counting, ATP quantification or radioisotope labelling, cannot therefore be used.

Starting from these considerations our team set out to develop a spectrophotometric approach to measure growth of cell populations deriving from individual clones of Molt3 human leukaemia cell lines. Growth rates of hundreds of clonal populations were measured and were analysed within the framework of a probabilistic model. The results show that populations from individual tumour cell clones have different growth rates and that this variability is likely to be of epigenetic origin. Attempts towards identification of the epigenetic factor(s) involved are also described here. Cell variants for growth rate are continuously generated in a tumour population, and this endogenous variability may confer greater fitness to the whole population under the pressure of selective environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and cloning conditions

Cells from the human T‐lymphoblastoid line Molt3 (ATCC number CRL‐1552) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany) supplemented with 2 mm glutamine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO., USA), 20 mg/L gentamycin (Biochrom AG), and 10% heat‐inactivated foetal bovine serum (Biochrom AG). Cells were grown at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere in T75 culture flasks (Greiner Bio‐One, Frickenhausen, Germany) and periodically were diluted with fresh medium to avoid starvation.

For cloning purposes, cells from exponentially growing cultures were seeded into wells of round‐bottomed 96‐well culture plates at the concentration of 0.3 cells/well into 100 µL complete medium. For each cloning experiment, cells were dispensed in 5–10 plates (480–960 wells). It is well known that at these limiting dilutions, the distribution of cells into the wells of culture plates follows Poisson statistics (Lefkovits & Waldmann 1979) and hence it is expected that 74% of the wells will contain no cells, 22% exactly one cell, and the remaining 4% two cells or more. Limiting dilution assays showed that, for Molt3 cells, plating efficiency, that is, the ratio between the number of wells scored as positive for cell growth and the number of expected wells, ranged between 0.5 and 0.7 (not shown). Thus, choice of seeding cells at the concentration of 0.3 cells/well was dictated by the conflicting needs of obtaining a high number of clonal populations from a reasonable number of culture plates.

Growth assays

The culture plates used in cloning assays were periodically monitored for cell population growth using a microplate spectrophotometer (Powerwave, Bio‐Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) and raw data were analysed with dedicated KC4TM software. For each well, absorption spectra in the wavelength range between 380 and 750 nm were collected and were compared to those measured for culture wells containing medium only (method fully described in the following section). The method was validated in parallel assays where cell population growth was also measured by direct cell counting and ATP determination. For both assays, cells were initially seeded in 96‐wells culture plates at a concentration of 10 000 cells/mL in 100 µL complete medium. Cells were counted using light phase‐contrast microscopy (Olympus IX51; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), using a Burker chamber, and the vital dye trypan blue (dilution 1 : 2), to exclude dead cells. ATP was determined by the luciferine/luciferase method using CellTiter‐Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Emitted light was measured using a microplate luminometer (FLX 800, Bio‐Tek Instruments) and data were expressed in luminescence arbitrary units. For both assays, at each time point, growth of six independent cultures was measured and averaged data compared to those evaluated by spectrophotometry for the same number of cultures grown under identical experimental conditions.

Mathematical analysis of growth curves

Growth data measured for each clonal population were fitted with the logistic equation:

|

(1) |

where y(t) is the population size measured at time t and y 0, a, b and t 0 are parameters that assume positive values. It should be noted that equation 1 describes a growth process characterized by an initial exponential phase with growth rate r given by:

| (2) |

with saturation level ym given by:

| (3) |

Equation 1 was automatically fitted to growth data from different clonal populations by means of a χ‐squared minimization algorithm written ad hoc in the Mathematica v.5.0 environment (Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL, USA). We used standard statistical quantities, such as the standard deviation of estimated parameter values, to accept or reject the results.

Isolation of mitochondria

Mitochondria were isolated from samples of 107 cells. Cells collected by centrifugation were washed several times, first with phosphate‐buffered saline and then with NKM buffer (0.13 M NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 7.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm Tris‐HCl pH 7.4) at 4 °C. Cell pellets were finally re‐suspended in 700 µL lysis buffer (10 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 10 mm Tris‐HCl pH 7.4) and were kept on ice for 3 min. Samples were carefully homogenized using a glass Potter and 50 µL of a 2 M sucrose solution were added. Homogenates were centrifuged at 1200 g for 5 min and pellets containing intact cells and nuclei were discarded. This procedure was repeated three times. Supernatants were then centrifuged at 7000 g for 10 min to separate the protein and microsomal fractions from mitochondria. Pellets formed of purified mitochondria were finally re‐suspended in CAB buffer (20 mm Na‐HEPES, 0.12 mannitol, 80 mm KCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.4) containing a mixture of protease inhibitors (Complete tablets, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and were stored on ice.

Flow cytometry assays

Cells and purified mitochondria were stained with 200 nm MitoFluor Red 589 fluorescent dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) which is a specific cell membrane‐permeable marker for mitochondria, commonly used to measure mitochondrial mass in intact cells. Both cells and mitochondria were incubated with the dye for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were then washed with phosphate‐buffered saline, whereas mitochondria were washed with cacodylate.

Cells were also stained for 30 min at 37 °C with 5 µm Vybrant® DyeCycleTM Green Stain (Invitrogen), a fluorescent dye developed to label cellular DNA in intact living cells. Fluorescence was measured using a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton‐Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) equipped with both antireflection and red diode lasers, and data were analysed using CellQuest (Becton‐Dickinson) software.

Quantification of mitochondria

Average number of mitochondria per cell <M> was estimated by flow cytometry. Cell populations and isolated mitochondria were labelled with the mitochondria‐specific fluorescent probe (see above), and mean fluorescence intensities of labelled and unlabelled samples – measured at the same sensitivity of the photomultiplier – were used to calculate <M> as follows:

| (4) |

where MFI is the measured mean fluorescence intensity of samples and subscripts C, UC, M and UM refer to intact cells, unlabelled cells, isolated mitochondria and unlabelled isolated mitochondria samples, respectively.

Standard deviation of the average <M> was calculated from the coefficient of variation (CV) of measured fluorescence intensity distributions:

|

(5) |

where n is the number of measured events. Standard deviation of <M> was then calculated by applying the usual equations from error propagation theory, which, in this case, reduce to the following equation:

|

(6) |

Preparing ρ0 cells from Molt3 cultures

The ρ0 cells were obtained by culturing Molt3 cells in the presence of 50 ng/mL ethidium bromide (Armand et al. 2004). Because treatment with ethidium bromide inhibits replication of mitochondrial DNA, mitochondrial DNA is progressively depleted and ATP production through oxydative phosphorylation blocked (Armand et al. 2004). Cells with non‐functional mitochondria cannot survive in standard complete RPMI‐medium, and culture media were therefore supplemented with 100 µg/mL pyruvate and 50 µg/mL uridine as previously described (Armand et al. 2004). Culture media were refreshed at 3 days intervals. After 24 days, cells were cloned (as described above) in the absence of ethidium bromide, and clonal populations expanded for a further 18 days. Cells from each clone were then split into two populations and were grown in parallel for 11 days in RPMI medium and medium containing pyruvate and uridine. Cells growing in pyruvate and uridine containing medium only, were scored as true ρ0.

The ρ0 cells were also subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis throughout the culturing procedure and results were compared to those obtained with normal Molt3 cells. To this purpose, DNA was extracted using the Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega) and 50 ng of total DNA were subjected to PCR, using mitochondrial specific primers (Holmuhamedov et al. 2002) and primers for a fragment of the nuclear β‐actin gene as control. Primers were as follows: mitochondrial DNA specific primers (giving an amplicon of 312 bp, Holmuhamedov et al. 2002): forward: 5′‐ACAATAGCTAAGACCCAAACTGGG‐3′; reverse 1 : 5′‐CCATTTCTTGCCACCTCATGGGC‐3′. Nuclear DNA specific primers (giving an amplicon of 311 bp within the β‐actin gene): forward: 5′‐CATTGCTCCTCCTGAGCGCAAG‐3′; reverse: 5′‐GCTGTCACCTTCACCGTTCCAG‐3′.

Amplification products obtained after 30 PCR cycles were analysed by electrophoresis on to 1% agarose gels.

Descriptive statistics

Where indicated in the next section, we compared experimental data with two‐tailed Student's t‐test. Probability threshold values P < 0.05 or P < 0.01 were considered to reject the null‐hypothesis and hence to define the differences between the data as statistically significant or highly significant, respectively.

RESULTS

Measuring cell population growth by microplate spectrophotometry

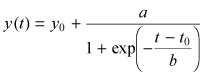

Figure 1a shows the mean spectra measured for 60 wells of a microplate containing an initial cell number of 1000 cells/well in 100 µL of complete growth medium and, for comparison, mean spectra measured for 60 wells containing medium only. Two peaks at 410 nm and 560 nm are visible and these correspond to the absorbance properties of the pH‐sensitive dye phenol red used in RPMI growth medium. Absorbance intensities of the two peaks varied in time as a consequence of cell growth and hence of acidification of the medium due to lactic acid secretion by cells. Only a slight variation in the absorption spectra was measured for wells containing growth medium only. At the 730 nm wavelength, spectra were not influenced by absorption of phenol red. At 730 nm, optical density of cell samples increased with time, and measures were not dependent on temperature, at least within the range 25–40 °C (not shown).

Figure 1.

Measuring the growth of tumour cells by microplate spectrophotometry. (a) Mean absorption spectra measured at indicated times for 60 wells containing an initial number of around 1000 cells (solid lines) and for 60 wells containing growth medium only (dashed lines). For the sake of clarity, SD is not shown; however, the observed maximum CV was < 2%. (b) Growth of six cell populations from an initial cell density of 10 000 cells/mL was measured by microplate spectrophotometry at 730 nm wavelength and data averaged (black circles). For comparison, cell growth was measured in parallel for six independent cell cultures grown under the same experimental conditions, by counting the cells at the microscope using the trypan blue dye exclusion assay (open squares). (c) The same spectrophotometric data shown in B are here compared to ATP measurements by the luciferine/luciferase method carried out on six independent cell cultures grown under the same experimental conditions. (d) Four Molt3 cell clones were isolated in different wells of a microplate and their growth monitored in situ by spectrophotometry. Lines represent the best fits obtained with equation 1. The figure provides an example of observed growth variability of clonal populations.

To test whether this increase correlated with cell growth, average optical density at 730 nm measured for six cell populations was compared to two independent measures of cell population growth, namely direct cell counting (Fig. 1b) and ATP determination (Fig. 1c). These were obtained in parallel experiments carried out under identical growth conditions.

The major difference between the three methods is that microplate spectrophotometry is not sensitive to cell death due to starvation taking place at the end of the growth assay. Dead cells are not immediately removed from cell cultures and hence they interfere with the optical measurements. However, as far as growth rate is concerned, microplate spectrophotometry is well suited to carry out measurements (Fig. 1b), and indeed it has the following significant advantages over the other methods:

-

1

Because cell sampling is not necessary to carry out measurements, growth of individual cell populations can be measured over time.

-

2

As a consequence of the above, one can avoid making replicates of the same cell culture.

-

3

Measurements only minimally perturb cell cultures.

-

4

It takes just a few minutes to measure growth occurring in 96 wells.

Thus, growth of individual populations from cell clones can be measured (Fig. 1d) and data fitted to the growth equation 1.

Growth rate variability of individual cell clones

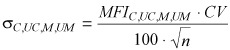

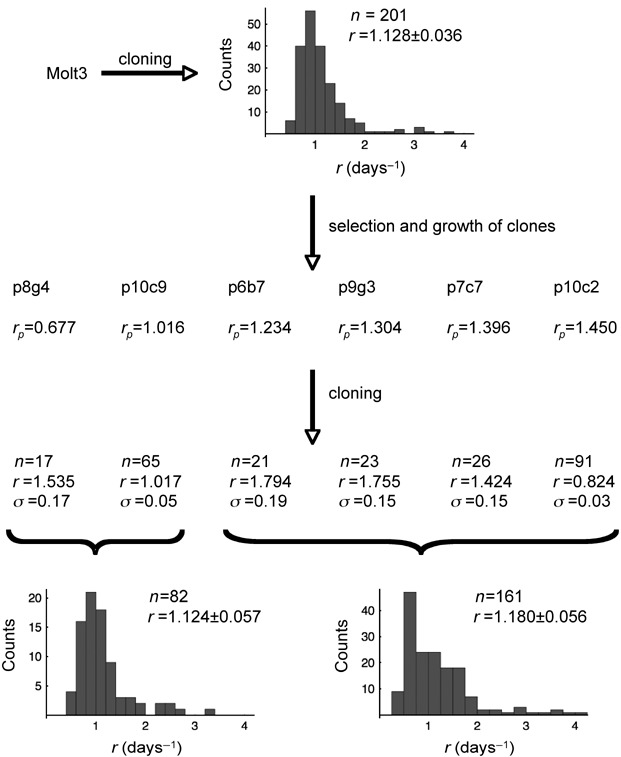

Molt3 cells were cloned, and growth of 201 clonal populations – from three independent experiments – was measured by microplate spectrophotometry. Growth rate of each clonal population was estimated by fitting data with equation 1. Growth rates of Molt3 clones distributed as shown in Fig. 2, and the mean value was found to be 1.128 ± 0.036 days−1.

Figure 2.

Epigenetic conjecture of growth variability of tumour cell clones. Molt3 cells were cloned and growth rates of each clonal population were estimated by fitting experimental data with equation 1 as shown also in Fig. 1d. Distribution of growth rates measured for n = 201 clonal populations is shown along with mean ± SD growth rate r. Six clones growing with indicated rates (rp), where the index p denotes that the rate is the mean rate of the clonal population, were then selected and cells were expanded in T25 culture flasks for 4 days. Two out of six clones showed growth rate below the mean value observed for cloned Molt3 cells and the other four a value above. Then, cells from these populations were further cloned and the mean ± SD value measured for the indicated number of clonal populations obtained is reported. For statistical purposes, growth rates measured for clonal populations obtained from the six initially selected clones were grouped as indicated and the two distributions obtained are shown in the figure. These distributions are similar to that of the parent Molt3 population. The mean growth rates do not significantly differ from that of the parent population (Student's t‐test, P > 0.05). Thus, ‘the growth rate’ is unlikely to be a genetically inheritable trait.

Variability of growth rates among different clonal populations can have either a genetic or an epigenetic origin or both. We reasoned that if the origin were genetic then the trait should have been conserved in offsprings of a given clone. Six clones from the cloning experiments were therefore selected at random; individual growth rates reported in Fig. 2. Two of the six selected clones (named as follows: number of microplate followed by the well coordinate) had growth rates below the mean value of the Molt3 population whereas the other four had value above. The six clones were expanded up to populations sizes of ≈106 cells and were further cloned. Growth rates of offsprings of the two clones, with initial growth rates below the mean value measured for Molt3 cells, and those from the four clones with growth rate values above were grouped and their distributions were analysed. Grouping was considered to minimize the source of errors given by the small number of isolated and measured subclones. Figure 2 shows that these distributions were qualitatively similar to that shown by the parent population. Indeed, mean growth rate calculated for 82 clonal populations from clones with initial growth rate below the mean value of Molt3 cells, and that calculated for 161 clonal populations from clones with initial growth rate above the mean value of Molt3 cells were not significantly different from that of the parent Molt3 population (P > 0.05 in both cases, Student's t‐test).

Thus, growth variability of individual tumour cell clones is unlikely to be a genetically inherited trait; rather, it is likely to be of epigenetic origin (see also the Discussion section for further comments on this point).

A theoretical hypothesis for the observed growth variability of clonal populations: mitochondrial activity as the possible epigenetic cause

We attempted to explain the observed distributions of growth rates (Fig. 2) from a probabilistic perspective. To do this, we supposed that some epigenetic factor existed in cells and had the following properties:

-

1

Growth rate of a clonal population is proportional to the average amount of the epigenetic factor.

-

2

Epigenetic factor is randomly distributed at mitosis, into the newborn cells.

-

3

Epigenetic factor must increase during the cell cycle up to a maximum value that is approximately twice its initial value at mitosis.

Property 2 is required to allow offsprings of a cell clone to randomly change their growth rates. The last condition, instead, has a mechanistic justification: if the epigenetic factor did not grow during the cell cycle, or conversely if it grew too much, then the daughter cells would receive a progressively lower or higher amount of epigenetic factor, respectively.

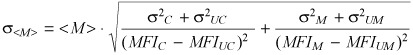

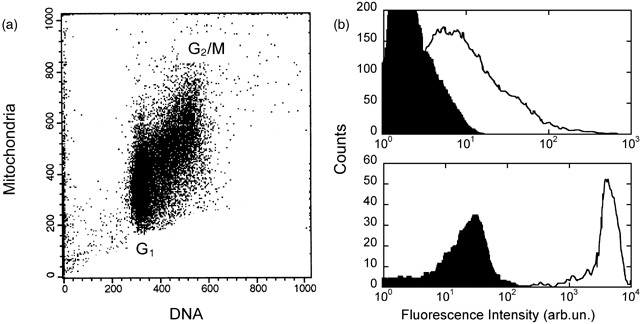

Mitochondria are known to provide the vast majority of energy, in the form of ATP, to tumour cells grown in vitro, and this energy is used by the cells to accomplish the various tasks of molecular synthesis required for progression through the cell cycle. In addition, mitochondria – as well as other cell organelles – are known to be randomly partitioned to the two daughter cells at mitosis (Birky 1983) and are known to double their number during the cell cycle (Posakony et al. 1977; James & Bohman 1981). The latter biological property was further assayed here experimentally, by flow cytometry (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

Flow cytometry experiments for the analysis of mitochondria in Molt3 cells. (a) Biparametric analysis carried out with mitochondria and nuclear DNA specific fluorescent probes. On average, the number of mitochondria in G2/M phase approximately doubles the value observed for cells in G1. (b) Mitochondria isolated from Molt3 cells (upper panel) and mitochondria in intact cells (bottom panel) were loaded with a specific fluorescent probe and were analysed. Intensity of fluorescence was collected for both samples at the same sensitivity of the photomultiplier. The black‐filled distributions of fluorescence intensity values show the data obtained for unlabelled mitochondria and cells.

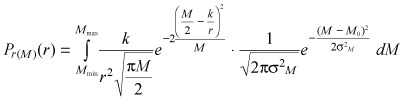

Thus, mitochondria are good candidates as epigenetic factor causing growth variability of tumour cell clones, and the probabilistic model that we have developed on the basis of the above considerations writes as follows (see the Appendix for details):

|

(7) |

where Pr (M)(r) is the probability density of growth rates r distributions, k is (linear, see the Appendix) growth rate of mitochondria, M 0 is the average maximum number of mitochondria in the cells (which is the average maximum number of mitochondria before mitosis, and ranging, among different cells, between M min and M max) and σM is the standard deviation that parametrize the fluctuations of M around M 0. It should be noted that three parameters are considered in equation 7, namely k, M 0 and σM, two of which are correlated (M 0 and σM ). To estimate values of these parameters by fitting, an independent measure of M 0 or of σM is therefore required.

For this reason, we estimated M 0 experimentally by flow cytometry (Fig. 3b). It should be noted that for fitting purposes knowledge of the exact maximum number of mitochondria in the cells is not required and that a rough estimate is sufficient. Cells and isolated mitochondria were labelled with a mitochondria‐specific fluorescent probe and measurements were processed as described in the Material and Methods (Fig. 3b). These calculations allowed us to estimate the mean number of mitochondria in the Molt3 cell population that turned out to be <M> = 225.7 ± 3.9, a number in agreement with values reported also by others (Robin & Wong 1988). This estimate, however, corresponds to the average number of mitochondria in desynchronized cell population. M 0 was therefore computed by assuming that growth in mitochondria numbers is linear in time (see also Posakony et al. 1977; James & Bohman 1981), which cells are evenly distributed in their cycles and which, as confirmed experimentally (Fig. 3a), mitochondria double their initial number before mitosis. Thus,

| (8) |

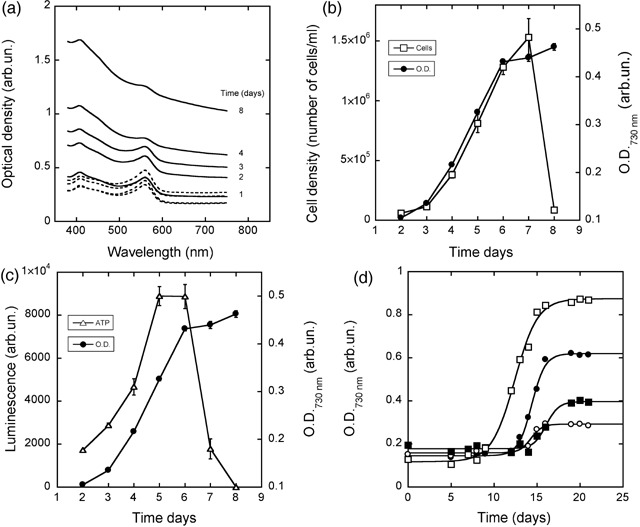

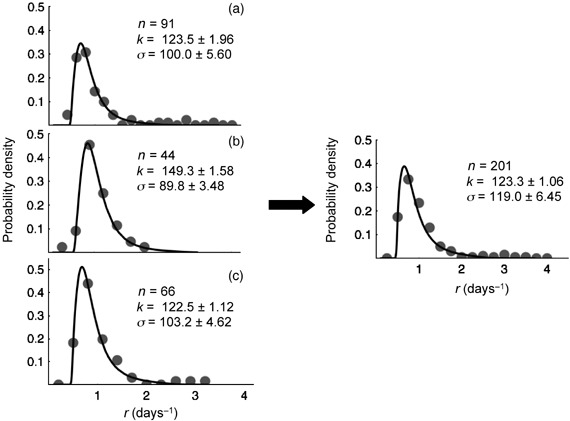

The above value was substituted in equation 7 and this equation, now with only two free and independent parameters, was numerically solved and fitted to growth rate distributions from independent experiments with Molt3 cells (Fig. 4). The fits showed good agreement between theory and experimentation.

Figure 4.

Distributions of growth rates of Molt3 clones and fits with model equation 7 . Distributions of growth rates measured for Molt3 clones from three independent experiments are shown (a, b and c). Values measured in these experiments were also grouped and analysed (right panel). In all figures, the line represents the best fit obtained with equation 7, the symbol n refers to the number of analysed clones, k is the linear growth rate of mitochondria estimated by data fitting and σ is the estimated standard deviation of the fluctuations of the maximum number of mitochondria around the mean number (see text for details).

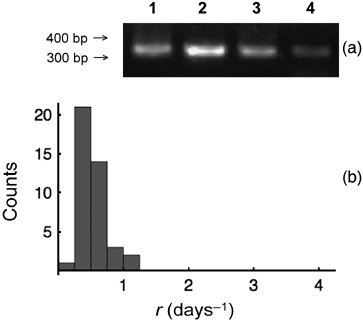

Growth rate variability of ρ0 cells

Results shown in Fig. 4 suggest that the observed growth variability of Molt3 clones is correlated with variability in the number of mitochondria they possess and transfer to their offsprings. If this were the biological basis of growth variability of individual clones, then Molt3 cells in which mitochondria are rendered non functional – the so‐called ρ0 cells – should grow with less variable kinetics with respect to normal Molt3 cells.

We obtained ρ0 cells by culturing Molt3 cells in the presence of ethidium bromide as described in the Materials and Methods section; they were identified and selected on the basis of:

-

•

loss of mitochondrial DNA (Fig. 5a)

-

•

dependence on uridine and pyruvate for survival (see Materials and Methods)

Figure 5.

Distribution of growth rates of Molt3 ρ0 cell clones. (a) PCR analysis of ρ0 cells. In each lane, 25 µL of the PCR products were loaded. Lanes are as follows: 1, nuclear β‐actin gene fragment, normal cells; 2, mitochondrial DNA‐specific fragment, normal cells; 3, nuclear β‐actin gene fragment, ρ0 cells; 4, mitochondrial DNA‐specific fragment, ρ0 cells. Traces of mitochondrial DNA are commonly visible in ρ0 cells (see also Armand et al. 2004). Thus, to demonstrate that these cells are true ρ0 functional assays must also be performed and in this paper, we have monitored their dependence on uridine and pyruvate for survival. (b) Distribution of the growth rates of ρ0 cell clones. Data are plotted on the same x‐axis scale as that used for normal cells for comparison (see Fig. 2).

Molt3 ρ0 cells were then expanded and cloned, and growth kinetics of individual clonal populations were analysed as described for normal Molt3 cells. Distribution of growth rates measured for 41 clonal populations is shown in Fig. 5b. With respect to that of normal Molt3 cells (Fig. 2), this distribution appears shifted to the left; this is due to growth kinetics of ρ0 cells which was approximately 2.1 times slower than that of normal (mean ± SE growth rate of 1.13 ± 0.036 and of 0.53 ± 0.026 days−1 for normal and ρ0 cells, respectively). Relative variability of growth rates was approximately 30% lower for ρ0 cells with respect to normal cells (CV 45.1% and 31.5% for normal and ρ0 cells, respectively). Thus, we conclude that the fluctuations in the number of mitochondria:

-

1

In general, are correlated to growth variability of individual clones.

-

2

In particular, determine approximately 30% of the growth variability.

DISCUSSION

That a tumour population is a heterogeneous ensemble of cell variants for a given trait has long been recognized, starting from the pioneering work on spontaneous transformation of embryo fibroblasts in vitro and on individual metastatic potential shown by tumour cell clones in vivo (Fidler 2002; Rubin 2005; references cited therein). These traits have been observed to vary among successive cell generations, and the pressure of environmental selection on genetically determined cell variants has been shown to play a pivotal role in allowing the onset of dominant – often more aggressive – variants (Fidler 2002; Rubin 2005). Thus, the growth of a tumour can be viewed as an evolutionary process whereby tumour cells, normal cells and environmental niches constitute a dynamical ecosystem (Hanahan & Weinberg 2000; Barcellos‐Hoff 2001; Fidler 2002; Vineis 2003; Rubin 2005). As expected, both genetic and epigenetic forces act to sustain competition between tumour and normal cells (Hanahan & Weinberg 2000; Barcellos‐Hoff 2001; Fidler 2002; Vineis 2003; Rubin 2005).

Duration of the cell cycle is recognized among the phenotypic traits that can vary in a tumour cell population (Chiorino et al. 2001 and references cited therein), and indeed heterogeneity of tumour growth kinetics is known to have serious implications for tumour treatment (Laird 1969; Norton 1985; Chignola et al. 1995; Wilson 2001). For this reason, variability in cell cycle duration has been extensively investigated for tumour cells both experimentally and theoretically (Chiorino et al. 2001 and references cited therein). In particular, statistical approaches have been used to model experimental data taken at the level of whole tumour cell populations, where intercell variability was indirectly estimated by mathematical analysis of data obtained in pulse‐chase experiments with radio‐labelled DNA bases (Wilson 2001) or, more recently, with fluorescent probes (Chiorino et al. 2001). Direct measurements of cell cycle duration at the single‐cell level have obvious technical limitations. Thus, we attempted to approach the problem from an experimental perspective that lies somewhere between the two extremes, represented by whole‐population and single‐cell measurements. We have shown that:

-

1

Heterogeneity in growth kinetics of clonal populations, which is of small populations from a single tumour cell clone, can be measured in vitro.

-

2

Growth variability of clonal populations is likely to be determined at the epigenetic level.

Although we could not determine the stability of this trait through generations, the data show that clonal populations after 20 days of culture – that is approximately 20 generations – possess a high degree of variability in their growth kinetics. The unexpected result therefore is that the variability of cell cycle duration of individual clones appears to propagate to their offspring. Propagation of the trait, on the other hand, is unlikely to have a genetic origin because the growth variability of populations generated by subclones is the same as in the parent population and hence the trait does not appear to be fixed in the progeny. This conclusion, however, deserves further discussion. There is increasing evidence, both theoretical and experimental, that genetic instability may play a crucial role in carcinogenesis (Beckman & Loeb 2005 and references cited therein) and in promoting the onset of tumour cell variants that, upon selection by the environment, may also acquire metastatic potential (Nguyen & Massague′ 2007). Genetic instability can indeed increase the rate of genetic change, including both base change and chromosomal instability (a process that has been defined as the mutator phenotype), and that has been proposed to be the origin of cell transformation and progression (Beckman & Loeb 2005 and references cited therein). To the best of our knowledge, however, genetic instability has been shown to act as a source of cell variability with characteristic times that are comparable with the human lifetime (Beckman & Loeb 2005), but its role in generation of new cell phenotypes in the short term is not available. On the other hand, using the Luria–Delbrück fluctuation test (Luria & Delbrück 1943) it has been shown that the rate at which new variants emerge in a mammalian tumour cell population is in the order of 10−6–10−8 variants/cell/generation (Kendal & Frost 1986; Rudd et al. 1990). Thus, within the time span of our experiments shown in Fig. 2– that comprises about 20 cell generations between the two cloning experiments – approximately 0.2–20 phenotypic variants are expected to arise in the population and contribute to the modification of the observed distributions of growth rates. The presence of these variants would produce new peaks in the distribution of growth rates, or if these peaks are very close, at least a broadening of the observed single peak. However, we observed no such deformation of distributions and therefore we rule out the hypothesis of genetic variability, at least within the resolution of our experiments. On the other hand, we do observe a variation of growth rates on experiments carried out with ρ0 cells, then we conclude that the effects of mitochondria silencing on cell growth variability are much higher than those related to possible genomic causes.

Variability in cell cycle kinetics has been assumed to stem from unequal cell size division or from fluctuations in the concentration of some cellular components (Chiorino et al. 2001 and references cited therein), both processes taking place at mitosis. These considerations have led us to hypothesize a role for mitochondria, but the data obtained with ρ0 cells show that fluctuations in the number of mitochondria can account of 30% only of growth variability of clonal populations. Thus, the most important epigenetic factor(s) behind growth variability of tumour cell clones are still to be identified.

Our data, however, indicate that a tumour population is a dynamic ensemble of noisy cell units. It is worth noting that noise, under the form of fluctuations in the concentrations of key molecules, can drive the differential expression of genes in otherwise identical cells (McAdams & Arkin 1999). This form of noise might also lead to different cycle times for individual clones, thus determining the variability of growth rates and perhaps of growth saturation levels. In fact, an open question that has not been addressed here is that clonal populations also reached different saturation levels (Fig. 1d) and we did not observe correlation with the growth rates (not shown).

Finally, we remark that the intercell variability of the cell cycle kinetics is not a novel observation, but all quantitative data on it are important in view of possible applications in tumour therapy, Although we presently cannot explain what causes the major part of growth variability of cell clones, we have shown that this aspect can be investigated quantitatively and can be modelled mathematically. Moreover, the mathematical model can be extended to include effects of other epigenetic factors. Clonal cell populations can be studied in isolation to understand the source of growth variability, and hopefully this will help in devising novel therapeutic strategies.

Supporting information

Appendix. A probabilistic model of growth rate variability of tumour cell clones

This material is available as part of the online article from: http://www.blackwell‐synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365‐2184.2007.00501.x

(This link will take you to the article abstract).

Please note: Blackwell Publishing is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supplementary materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Prof. Massimo Delledonne and Dr. Alberto Ferrarini, both at the Department of Science and Technology, University of Verona, for their help and assistance during the execution of PCR assays. The authors also thank Giancarlo Andrighetto, emeritus Professor of Immunology but still master of rock climbing, for his enthusiastic support. In particular, R. Chignola wishes to dedicate to him the efforts that he put in the present paper in gratitude for the intense discussions that he has had over the years and that he is still having on the subjects of the work, discussions that frequently take place in rather unusual laboratories such as the Dolomites’ walls or the underground labyrinths of deep caves in the Apuane Alps.

The primers were designed based on the data published in Holmuhamedov et al. (2002). The sequence of our reverse primer, however, corresponds to the complementary sequence given in Holmuhamedov et al. (2002) and indeed sequence alignment analysis showed that the two primers described by those Authors incorrectly bind the same DNA strand. In addition, our sequence was reduced by one base to limit the difference in the melting temperatures between the forward and the reverse mitochondrial DNA specific primers.

REFERENCES

- Armand R, Channon JY, Kintner J, White KA, Miselis KA, Perez RP, Lewis LD (2004) The effects of ethidium bromide induced loss of mitochondrial DNA on mitochondrial phenotype and ultrastructure in a human leukemia T‐cell line (MOLT‐4 cells). Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 196, 68–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcellos‐Hoff MH (2001) It takes a tissue to make a tumor: epigenetics, cancer and the microenvironment. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 6, 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman RA, Loeb LA (2005) Genetic instability in cancer; theory and experiment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 15, 423–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birky CW Jr (1983) The partitioning of cytoplasmic organelles at cell division. Int. Rev. Cytol. Suppl. 15, 49–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chignola R, Foroni R, Franceschi A, Pasti M, Candiani C, Anselmi C, Fracasso G, Tridente G, Colombatti M (1995) Heterogeneous response of individual multicellular tumour spheroids to immunotoxins and ricin toxin. Br. J. Cancer 72, 607–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chignola R, Dai Pra P, Morato LM, Siri P (2006) Proliferation and death in a binary environment: a stochastic model of cellular ecosystems. Bull. Math. Biol. 68, 1661–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chignola R, Schenetti A, Chiesa E, Foroni R, Sartoris S, Brendolan A, Tridente G, Andrighetto G, Liberati D (1999) Oscillating growth pattern of multicellular tumour spheroids. Cell Prolif. 32, 39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiorino G, Metz JAJ, Tomasoni D, Ubezio P (2001) Desynchronization rate in cell populations: mathematical modeling and experimental data. J. Theor. Biol. 208, 185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisboeck TS, Berens ME, Kansal AR, Torquato S, Stemmer‐Rachamimov AO, Chiocca EA (2001) Pattern of self‐organization in tumour systems: complex growth dynamics in a novel brain tumour spheroid model. Cell Prolif. 34, 115–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler IJ (2002) The organ microenvironment and cancer metastasis. Differentiation 70, 498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2000) The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 100, 57–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmuhamedov E, Lewis L, Bienengraeber M, Holmuhamedova M, Jahangir A, Terzic A (2002) Suppression of human tumor cell proliferation through mitochondrial targeting. FASEB J. 16, 1010–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James TW, Bohman R (1981) Proliferation of mitochondria during the cell cycle of the human cell line (HL‐60). J. Cell Biol. 89, 256–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendal WS, Frost P (1986) Metastatic potential and spontaneous mutation rates: studies with two murine cell lines and their recently induced metastatic variants. Cancer Res. 46, 6131–6135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird AK (1969) Dynamics of growth in tumours and normal organisms. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 30, 15–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkovits I, Waldmann H (1979) Limiting Dilution Analysis of Cells in the Immune System. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luria SE, Delbrück M (1943) Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics 28, 491–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams HH, Arkin A (1999) It's a noisy business! Genetic regulation at the nanomolar scale. Trends Genet. 15, 65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DX, Massague′ J (2007) Genetic determinants of cancer metastasis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton L (1985) Implications of kinetic heterogeneity in clinical oncology. Semin. Oncol. 12, 231–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posakony JW, England JM, Attardi G (1977) Mitochondrial growth and division during the cell cycle in HeLa cells. J. Cell Biol. 74, 468–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin ED, Wong R (1988) Mitochondrial DNA molecules and virtual number of mitochondria per cell in mammalian cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 136, 507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin H (2005) Degrees and kinds of selection in spontaneous neoplastic transformation: an operational analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 9276–9281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd CJ, Daston DS, Caspary WJ (1990) Spontaneous mutation rates in mammalian cells: effect of differential growth rates and phenotypic lag. Genetics 126, 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vineis P (2003) Cancer as an evolutionary process at the cell level: an epidemiological perspective. Carcinogenesis 24, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg RA (1989) Oncogenese, antioncogenes, and the molecular basis of multistep carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 49, 3713–3721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GD (2001) A new look at proliferation. Acta Oncol. 40, 989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix. A probabilistic model of growth rate variability of tumour cell clones

This material is available as part of the online article from: http://www.blackwell‐synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365‐2184.2007.00501.x

(This link will take you to the article abstract).

Please note: Blackwell Publishing is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supplementary materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item